The music industry wasn’t ready for Chief Keef

More than five years since the chicago rapper’s debut album, it’s impossible to deny his immense influence on modern-hip-hop..

I first met Chief Keef one unseasonably warm day in late January roughly six years ago, while he was on house arrest. He wore flannel pajama bottoms, a black t-shirt, and rosary beads, and we sat in the sunlight of his grandmother’s Chicago living room next to a portrait of Barack Obama while I asked him questions about his music. “See, motherfuckers think I can’t do metaphors. They—” he gestured at a fanbase, somewhere outside his grandmother’s apartment, “—don’t want to see me do that. I don’t sit down and ‘think,’ I write about what’s going on right now, what we just did, what just happened. That’s what I write about.”

When we left, I asked my brother, who’d tagged along to take photographs, what he thought of the rapper who was — though we didn’t know it — on his way to becoming Chicago’s biggest star since Kanye West. In the years since, interviewers invariably describe Keef as petulant, incoherent, difficult, or drugged-out. Online, it was suggested he suffered from a learning disability, and message board rumors proliferated that he was autistic, as an explanation for his awkward on-camera behavior. But my brother’s immediate response at that early date felt closer to my own: “He’s so self-possessed.”

It’s no longer original to suggest that Chief Keef ended up being more influential than most expected when he burst from obscurity in 2012. “Influence,” after all, is an easy concept for a writer to apply, as it requires minimal investment — “influential” doesn’t mean “good,” or even “important” — and the scantest evidence. Music flows forward in an ever-broadening conversation, and ideas are constantly pilfered and improved upon, from even the least captivating artists. Any star who has been influential has been influenced, and every rapper who achieved any sort of fame over the past decade is described as “influential” at one point or another: Drake, Lil B, Odd Future, ASAP Rocky, Young Thug, Future, Migos.

But I’d contend that over the past six years, since Chief Keef first emerged, his impact has more directly defined the sound, shape, and tone of hip-hop writ large, than any other artist. (Kanye West — whose remix of “Don’t Like” both propelled and obscured Keef’s original — remains a powerful artistic barometer, but his biggest aesthetic impacts predate Keef.) Keef’s emergence was a paradigm shift that marked the arrival of a new generation, a sea change in the music’s sound, in how it was covered, where it came from, and how the industry marketed their artists. It’s especially impressive because he’s done so from an obscured position, invisible in the broader musical discourse. And the bulk of this influence came not from his work in the mainstream spotlight of 2012, but in his work after — when the popular consensus was that his career was over, a misfire, the product of opportunistic media hype.

When Keef’s 2012 debut label record, Finally Rich , sold just 50,000 first week physical copies, it was taken as consensus that his actual impact within hip-hop had been modest — that once again, the industry had overvalued online conversation and controversy over the tastes of listeners in the “real world.” But the truth was that for a new generation in the “real world,” social media and streaming meant his most devoted fans simply weren’t listening to CDs.

It seems obvious today, when streaming numbers drive the industry. Streams are a reliable predictor of ticket sales, and predict artist signings at both major and indie labels. Sales numbers, in 2018, are conjured through a complex formula incorporating streams and CDs, and for the vast bulk of hip-hop artists, those streaming “sales” dwarf CD sales. But in 2012, the Apple Music streaming service did not exist; Spotify had only been available in the United States since July 2011, and had only 5 million users worldwide by December of the following year. (Today it claims 70 million.) YouTube, where the majority of Keef’s fanbase consumed his work, had no impact on Billboard chart positions until February 2013 , just as mainstream attention in Keef was beginning to wane. (When he did receive notoriety afterwards, it tended to focus on his list of ultimately minor legal infractions.)

In fact, his impact was meteoric. It can be witnessed in a comparative chart of Google search volume , which at its peak dwarfed the peaks of his contemporaries, who are now seen as more “mainstream” stars. Larry Jackson, the A&R who signed Keef to Interscope before leaving with Jimmy Iovine to work on Apple Music, put his new kind of stardom in perspective, telling me: “Week over week at Interscope, he was the most active social media artist we had. Bigger than Lady Gaga, in terms of mentions and online activity. Bigger than Maroon 5. He was a social juggernaut. There was nobody who had the kind of gravitational pull he had online. He was the first.”

During this period he took a radical new approach to the sound and composition of rap records, a prolific series of blueprints emulated by the many artists who followed in his wake. Unlike Soulja Boy — whose populist teen groundswell was one of Keef’s own inspirations — Keef developed a complex, cohesive, evolving aesthetic language, a style of both music and marketing, which was readily emulated over the next five years at home and across the country. Keef took a magpie approach to songwriting, building songs from the loose pieces of his influences: a one-off money-machine adlib from an obscure Yo Gotti mixtape cut would become a Keef signature ; an obscure piece of D.C. slang would become the inspiration for a new song . This is how rap works broadly: pieces of linguistic and cultural detritus become the building blocks for even its greatest artists. Keef’s approach showed a sophistication and cultural knowledge that dwarfed most of his peers, pulling loose pieces from artists across the country and not only crafting an original rap style, but creating a seemingly endless variety of new forms from the rubble.

Keef had reoriented hip-hop’s center of gravity, pulling the genre into his orbit.

All of this interest occurred during the 2013-2016 period in which mainstream press attention to Keef was at low ebb. And yet interest among his core fans — including many of the artists who would become the next generation of stars themselves — remained high. It’s not hard to hear Keef’s influence on each of them, the Bush or Silverchair to his Kurt Cobain. One needs to look only at the 2016 XXL Freshman Class , the cover story focusing on the new generation of hip-hop stars. Each seems borne from a single strand of Keef’s creative DNA, a reflection of a different side of his sound, residents of a world he created.

Lil Uzi Vert was a Philadelphia fast-rapper two years Keef’s senior who completely reinvented his sound in the wake of Keef’s turn toward melody, as can be heard on “Love Sosa”-aping “Senor Guapo,” or the Bang 2 echoing “7AM” — a heavy influence Uzi has freely admitted . In 2013, before Uzi Vert’s name had earned any attention nationally, Danny Brown articulated what would be his entire sales pitch , in an interview with Pitchfork when describing Chief Keef: “To me, Chief Keef is totally punk rock. Like, the melodies he uses on his album– it’s like he’s not even rapping no more, he’s just singing. You could swap those synths and keyboards with guitars and fucking crazy drums and he’ll be a rock star.” But he wasn’t just singing; Atlanta’s Playboi Carti built a style that picked up on the drier sound of Keef’s wall-of-sound adlibs, fixated upon them. Atlanta’s 21 Savage, whose initial hit “Red Opps” banks off Chicago lingo and whose hit “No Heart” builds on a flow from Keef’s “Gettin Wild,” drew on the dead-eyed, detached aspect of the early drill sound.

In 2017, the emulation continued, as a wave of “SoundCloud rap” stars built on the swag and style of Keef and other Chicago drill artists, but aimed towards a suburban market; the slang of Keef and co. proliferates throughout this sphere, as does a reliance on mumbled and melodic styles and an obsession with the drugs popularized by traumatized artists with a Chiraq background. The “Aye” flow — a style of rapping Keef popularized throughout 2014 — had by 2017 taken over the genre as thoroughly as the “Migos flow” several years previous, with everyone from Travis Scott to Chance the Rapper to XXXTentacion emulating the style . Outside the media spotlight, which has fixated on SoundCloud rap, Keef’s influence extended into street rap grassroots. His own against-the-beat rhythmic pocket and stubbed flows with short, unpredictable phrasing proliferated in cities like Detroit, where Keef worked with similar street artists like Yae Yae Jordan and Rocaine, and has developed further among post-Keef street rappers with an ear for narrative style, like Chicago’s Valee and L.A.’s Drakeo. These artists don’t emulate Keef directly; rather they carry on an artistic lineage he’d returned to the forefront, a purposeful rhythmic deviation, a new sense of swing which sits between craft and intuition.

Yet it was not just those artists driven to emulation who benefitted from his immense center of gravity. He’d become a common denominator for whom new artists could market themselves in the contrast, who would find success in a marketplace which would rewarded them for being an anti-Keef. Chance the Rapper offered an optimistic vision for those eager for a young Chicago artist whose worldview didn’t seem quite so bleak. Rae Sremmurd’s youthful cheeriness offered a parent-approved pose Keef refused to perform. The Migos’ typewriter-like precision flows, which emerged one year later, were seen as a “lyrical” contrast by fans resistant to the newly dominant style of slurred mumbling. Young Thug’s elaborate melodic architecture and unconventional personal style was an eccentric, stylized parallel thread more beloved by critics, torn over Keef’s traditionally macho approach.

Before Rihanna released Anti , Keef described himself as “an ’anti-’ ass n---a, I don’t speak for shit.” His was a work of negation, a depressed paradigm against which every artist seemed to define themselves. His ideas detached from his art, his lingo becoming “powerful” affirmations of worth , or helping sell skincare products . Even Future, more than a decade Keef’s senior and one of his own influences, seemed temporarily unsure of his footing, his Monster rebrand a tonal shift back towards pessimism after the romantic ballads of the Pluto era were in danger of being eclipsed; Finally Rich outsold Pluto in first week sales, and Honest , its follow-up, only sold a few thousand more in its first week, with a much more robust roll-out. Rappers like Rick Ross, who’d relied on big-budget industry bangers, found their flat-footed flows were a relic overnight, as the drill music’s brash sound shifted toward melodic amorphousness and rhythmic uncertainty. Keef had reoriented hip-hop’s center of gravity, pulling the genre into his orbit.

Much as it was for Gucci Mane before him, citing Chief Keef’s “influence” has become a shortcut to argue his significance to hip-hop’s core fans, an importance largely invisible to the wider world, which wrote him off as temporary spectacle. Plenty of artists are influential without producing great music, of course, and considering the scope of Keef’s early success it would be easy to argue that it was a gatekeeper-propelled success alone which earned that following, anyway. To show that the new class of young rappers heavily emulated him isn’t itself an argument for his music’s inherent value. Indeed, even as the critical establishment belatedly opens itself to the idea his music is “influential,” the work itself is viewed from a distance, marked as “difficult” “fringe experiments,” even though the artists who benefit from his ideas reach the absolute apex of commercial success. His fanbase is often described as if they were a “cult following,” even though that “cult" seems to have included the broadest possible cross-section of rappers to find success since.

That his music requires a unique or even fetishistic sensibility to keep up with has been reflected in any number of publications, which keep the music at arm’s length even as they deign to cover it. Most recently, Keef’s Bankroll Fresh/Young Jeezy-styled Dedication — perhaps the most straightforward rap album he’s yet released — was cautiously qualified by Pigeons and Planes as “definitely not for everyone,” as if that couldn’t equally describe most artists covered by any music publication. In a year in which Keef dropped four full-lengths, Fader ’s list of the best songs of 2017 highlighted “Come Down,” his benign contribution to Mike Will Made It’s Ransom 2 , a song less reflective of Keef’s own innovative musical sensibilities than blandly traditional pop songwriting. To a world uninvested in hip-hop’s creative evolution, his value in these write-ups is primarily as a cult celebrity, a personality, or a meme, a flattened symbol of his background or media narrative. Just as his art itself seems to speak directly to one segment of his audience, it creates a mass-mental block in many other listeners, as if its value were fundamentally inscrutable.

Keef’s breakthrough single, “Don’t Like,” was often described as “nihilistic.” Nihilism came to stand in for everything: his music, his attitude, his person, his politics. It suggested he lacked an ideology, a belief system, or agency. He was a product of forces outside himself; his importance was a weightless, symbolic kind, a canary in the coalmine of the system’s moral rot. This isn’t entirely an accident; Keef’s attitude on “Don’t Like” purposefully creates a chasmic distance between listener and artist. Even as he utilized populist tools (catchiness, bluntly direct lyrics), this attitude keeps listeners at a remove, in parallel with how his art received arm’s-length treatment in certain spaces. Yet crediting “nihilism” for this distancing feels imprecise. Say what you will about them, but interest in authentic merchandise, affirmation of a familiar criminal code, and the ever-present armor of violence — a trope of street rap since N.W.A. — are not nihilistic values.

Rather than nihilism, Keef’s main attitude in the song is a much more obvious and familiar one: irritation . A list of things Chief Keef doesn’t like is a list of things he’s irritated by, a low-energy displeasure which reduces a range of concerns (bootleg sneakers; a friend’s betrayal at the jaws of the criminal justice system; the clinginess of romantic partners) to roughly equal standing. Our jarring experience of this music isn’t to its “nihilism,” but to his seemingly disproportionate, understated response to a life we think should prompt stronger reactions. Anger, say, at the injustice of his upbringing. Or perhaps he should respond in sadness, at the way death had shaped his life. (Essays critical of Keef’s “nihilism” often urged he “emerge as a voice that expresses the pain of his life...enough to move people to change,” though he’d already released expressive songs like this, such as 2009’s “Dead and Gone,” when he was just 14.) But “Don’t Like” isn’t angry or sad. If anything, the song’s video even suggests catharsis — joy, perhaps, at the empowering potential of feeling irritated.

But how can irritation be empowering? “Irritation” is what literary theorist Sianne Ngai calls one of the “Ugly Feelings,” in her 2005 book of the same name. These ugly feelings — dysphoric affects such as envy, anxiety, paranoia, and irritation, among others — are low-wattage, equivocal, and tend to sustain as moods, in contrast with more powerful emotions like anger, which hit sharply and suddenly subside and are seen to inspire action. Anger is widely accepted as a medium for political art; there’s no band called Irritate Against the Machine. Yet Ugly Feelings is an exploration of how these more ambiguous emotions, which tend to derive from situations of restricted agency, speak more directly to the way we live now — and to the way art itself is tolerated by a society that sees it as essentially toothless, unthreatening.

“There was nobody who had the kind of gravitational pull he had online. He was the first.” — Larry Jackson, former Interscope A&R

As mainstream attention waned and certain listeners became increasingly perplexed, his musical choices began to deepen their depiction of “Don’t Like”’s conceptual “ugly feelings.” “Bussin,” a popular 2014 loosie based around shootings in the neighborhood, treats outside gunfire as an unsettling, ambient constant. Rather than inspiring a sharp emotional response like fear, anger, or sadness, as one might expect, the music’s mood and lyrics create a sense of gunfire rolling in like stormy weather. Keef’s delivery shifts from controlled to fiery and back again. Like an engine trying to start that can’t quite turn over, his voice fights to make contact with the relentless, implacable rise-and-fall production. The effect is like a bad dream, as if for all his motion, he remains suspended in mid-air, trapped in a state of existential paranoia.

In this way, he pursued hip-hop’s possibilities not just at mere levels of lyrics or flow, but through the full breadth of song forms, and how these many forms create a range of effects. On the deliberate “Go to Jail,” he slowed the tempo to a crawl, a choice which seemed to test the audience, to make them yearn for the melodic structure which gradually coheres beneath the weight of his crumbling vocal timbre. These melodic records toyed with notions of his own agency—what was him, and what was the drugs?—yet their increasing sophistication over time, their further harmonic and textural invention, suggested an artist in control of his creations. Other songs developed his voice as a rapper, relying on dizzying, disorienting production, Keef’s unpredictable phrasing forging its own rhythmic pocket. Even to characterize his work as solely the domain of “ugly feelings" risks pigeonholing; some of his most popular underground hits were cheery trap anthems , another anomaly for the genre.

For many artists, being not-Keef was a benefit; for others, emulating his blueprint would benefit them, too. The only rule was that they should not be him. In actuality, his rise coincided with his fall, and the fall of his city. Before the 2012 drill boom, Chicago was painted by Obama-phobic right wing commentators not as a locus of violence, but of corruption and left-wing politics, of Tony Rezko and Bill Ayers. When Keef burst from obscurity, the script was rewritten, and Chicago became the source of a national pathology of violence. As Ta-Nehisi Coates would put it, Chicago became “code for ’black people’” —a deceptive racist shorthand, a method of creating an undifferentiated mass of uber-violent criminals against whom America could define itself. It wasn’t just the political right who bought into this idea; they might see Keef as a “monster,” but he was as dehumanized by a consensus view that saw him as a product of forces beyond his control.

Yet it wasn’t the spectacle of “black on black violence” which propelled Keef among his core fans. In December 2011, three months before Trayvon Martin was killed in Florida, Keith Cozart—a teenager six months his junior — was arrested for pulling a gun on a policeman. But rumors spilled out through the high schools that Keef had been killed in a shootout with police. In fact, he’d survived after a policeman shot at him. These events inspired the name of Chief Keef’s breakout mixtape, Back From the Dead . Yet still the grim spectre of Chicago’s “uniquely” violent backdrop shadowed them: “I didn’t and wouldn’t interview Chief Keef early on,” said Hot97/Beats 1 radio host and consensus-shaping gatekeeper Ebro Darden, who would go on to propel the career of New York’s Bobby Shmurda — a rapper whose sudden viral success in 2014 50 Cent called a “New York version” of Chief Keef. To this day, Keef’s unable to book a performance in his own hometown — even in holographic form — by police dictum.

In 2015, Keef and crew finally left the Chicago area for Los Angeles, where he lives today. A catalyst was the popped tire on a motorbike. “Five minutes later there’s 20 police cars surrounding the house with AK-47s,” Keef’s then-manager Rovan “Dro” Manuel told me. “In Highland Park. Tell me how safe, how much you’d want to stay around something like that. A tire popped and you walk outside the house, fifteen to twenty police officers with AK-47s with their fingers on the trigger. At any given time they could have made a mistake, or said, you know, ‘I see a gun!’ and AK-47s — ain't no turning back from that.”

The way “Don’t Like” feels so exuberantly irritated, the way it pushes away some listeners while attracting others, shows how aesthetics and politics can be deeply intertwined. In forcing listeners to react to his disproportionately modest response to extreme experiences, he retains power, and makes himself the target of the listener’s disdain. He shifts our attention from the injustice of his experience to his seemingly insufficient response. At this point, the listener makes a choice: does his refusal to perform sadness or anger or any other “expected” emotion make us disproportionately angry at him? Or do we identify with his attempt to wrest control and power from narratives and mechanisms which seek to annihilate his?

Who we are shapes how we will respond. Keef is, of course, influential, possibly the most influential hip-hop artist of his time. There’s a good case to be made he’s his generation’s foremost rap songwriter, spinning off more styles than any of his peers, which would put him at the forefront of his generation in popular music writ large — even if that creative success isn’t reflected by plaques on the walls. But the more interesting question is how he came to be so, and the answer is in his music. His creative choices made him a leader, especially for those who aspired to lead who he did, as he did.

The Outline

Chief Keef changed the music industry – and it’s time he gets the credit he deserves

Assistant Professor of Race and Media, University of South Carolina

Disclosure statement

Jabari M. Evans does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of South Carolina provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Before he was arrested in December 2011, Chief Keef was a 16-year-old budding rap star. He’d released a song, “ Bang ,” which had more than 400,000 views on YouTube, along with a mixtape that he’d recorded in a friend’s bedroom. He also had a dedicated Twitter following among Chicago high school students.

The track displayed a rawness unlike anything else that was released at the time, and you couldn’t stroll down the streets of Chicago’s South Side without hearing Bang’s lyrics pulsing from the stereos of cars rolling by:

Yet he was almost completely unknown outside of Chicago. His Facebook profile had less than 2,000 followers, he claimed his occupation was “smokin’ dope” and he still lived with his grandmother.

Nevertheless, the verses written and hastily disseminated on social media by Chief Keef and his peers were fast becoming a unique sort of news ticker for low-income communities of color in Chicago, detailing the turf wars, rivalries and hassles of everyday life as a Black kid growing up in the city.

The songs became known as drill music , a genre characterized by its dark synths, booming 808 drums, seemingly off-beat, mumbled verses and war-cry choral chants. Its vanguards – artists like Chief Keef, King Louie, G Herbo and Lil Durk – emerged as local heroes by staying tethered to the blocks and neighborhoods they rapped about on SoundCloud and YouTube. Eventually, the national press caught on. The coverage was often less than flattering.

At the time, I was entrenched in my own hip-hop music career, rapping under the moniker Naledge in the duo Kidz in the Hall . As I was touring the country, I noticed that everyone from back home in Chicago was asking me if I’d heard of this kid Keef who was from Washington Park.

I knew that if a 16-year-old kid had the city buzzing, it would only be a matter of time before he was famous. What I didn’t know is that five years later, the drill subculture would be the subject of my field work as a doctoral student at Northwestern and that it would inspire me to write about the ways in which the city’s Black youth dealt with cultural, racial, economic and political oppression through inventive media production .

I started to argue, to anyone that would listen, that drill music was more than shock value or a new spin on gangsta rap. The scene planted the seeds for hip-hop’s ascendancy in music’s digital economy.

Drill goes viral

When Chief Keef’s house arrest ended, on Jan. 2, 2012, WorldStarHipHop posted a video of a young child in a hysterical fit of excitement, bounding around a room and rapping along to “Bang.”

The video of the boy went viral in the hip-hop community, and curious viewers furiously searched YouTube for more Chief Keef content.

Later that year, Chief Keef cemented his national reputation with the commercial success of his song “ I Don’t Like .” As the lead single for Chief Keef’s debut album, “Finally Rich,” “I Don’t Like” charted on the Billboard Hot 100 , accumulated tens of millions of listens online and helped drill break into the nation’s musical mainstream.

Within months of the song’s release, drill was seemingly everywhere. Hip-hop icons like Kanye West and Drake began co-signing drill rappers, while record labels instigated bidding wars over the South Side of Chicago’s budding rap talent.

At the time, drill music was still one of the only music scenes to exist almost exclusively on YouTube and free streaming sites like SoundCloud and DatPiff.com – a form of DIY distribution that circumvented the traditional gatekeepers of the rap music industry. Songs were churned out via singles, curated playlists, snippets and low-budget music videos that could be edited and released instantly by artists direct to their audiences via social media.

The most popular YouTube videos for drill songs were often shot in low-income apartments or on street corners , with the local crews standing behind the artist performing , pointing weapons at the camera and rapping about the recent events of ongoing street wars.

Initially, many journalists and researchers focused almost exclusively on how youth in the drill scene used their songs to perform “ internet banging ,” or threatening rival gang members and planning crimes over social media.

Media outlets like the Chicago Tribune, the Chicago Sun Times, Noisey , Pitchfork , Spin , The New York Times and WorldStar Hip Hop extensively covered the rise of Chief Keef and the drill scene, pointing to the violence inspired by the lyrics and the gang affiliations of the artists as the source of their viral appeal.

Police not only started monitoring the social media accounts of drill rappers, but also effectively banned Chief Keef from performing in his hometown by encouraging venues not to book drill rappers and telling promoters that they’d shut down drill shows.

The drill scene did incite violence. For example, in August 2020, drill rapper FBG Duck was murdered in the upscale Gold Coast neighborhood a year-and-a-half after threatening the O-Block street gang in a music video . In October 2021, the U.S. Attorney’s office for Northern Illinois indicted five members of the O-Block street gang for the murder, pointing out that the gang has “publicly claimed responsibility for acts of violence in Chicago” and “ used social media and music to increase their criminal enterprise.”

[ Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter .]

Rethinking the legacy of the drill scene

Though deaths like FBG Duck’s make headlines, my interviews with those affiliated with artists like Chief Keef have shown me that the gang violence associated with drill is hardly the reason these artists found success.

Instead, they wrote a blueprint for artists in hip-hop’s streaming era.

In the decade since Chief Keef became an “internet famous” rapper with the song “Bang,” a lot has changed in the music industry. There’s now no real demarcation between being a famous musician online and one who’s been elevated by the industry’s power brokers. Tekashi 69, Lil Yachty, 21 Savage, Juice WRLD and Lil Uzi Vert are just a few of the artists that built on the swagger, style, aesthetic and internet distribution model pioneered by Chief Keef.

Chief Keef was among the first to broadcast everyday life in Chicago’s gang territories to the world. His “ stream of consciousness ” style – saturating his YouTube channel videos of himself hanging out with his friends, meeting up with female fans, smoking marijuana and recording songs in his home studio – was a window into everyday life that’s been emulated by pretty much every pop star since.

Moreover, his willingness to give away music for free also paved the way for the “ SoundCloud era ,” in which artists like Chance the Rapper, Lil Pump and Doja Cat gained huge followings not through record deals, but through releasing tracks on SoundCloud.

Chief Keef’s unique slang and mumbled, melodic rapping style have also sparked drill youth movements in places as far away as Australia , London and Ghana .

Yes, Chief Keef’s story is out-of-the-ordinary: Getting in a shootout with police at the age of 15 and filming videos while on house arrest aren’t exactly common adolescent experiences. But his ability to present that story to the world and brand his style within a larger movement speaks to his genius.

In my forthcoming book project, I nod to the drill subculture that he spearheaded as reflecting the potential of Chicago’s Black youth. Denied full access to resources that might have helped them overcome their trauma and avoid gang lifestyles, Chief Keef and his peers used social media to persevere and make careers for themselves in music.

A lot that could be gained by not overlooking the creativity and ingenuity of teens and young adults like Chief Keef. He’s a perfect example of the ways in which young Black kids are unintentionally innovating within social media while simply navigating violence and poverty.

What if the violence that accompanied his work were seen as a bug, not a feature? How might his creative output been harnessed to bolster – rather than vilify – the impoverished communities he rapped about?

- Social media

- Digital divide

- Going viral

- X (formerly Twitter)

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Initiative Tech Lead, Digital Products COE

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Chief Keef changed the music industry – and it’s time he gets the credit he deserves

A lot could be gained by not overlooking the creativity and ingenuity of teens and young adults like drill music vanguard Chief Keef. Journalism and mass communications professor Jabari Evans writes for The Conversation that drill subculture arose out the ways Chicago's Black youth navigate violence and poverty by innovating within social media.

Before he was arrested in December 2011, Chief Keef was a 16-year-old budding rap star. He’d released a song, “ Bang ,” which had more than 400,000 views on YouTube, along with a mixtape that he’d recorded in a friend’s bedroom. He also had a dedicated Twitter following among Chicago high school students.

The track displayed a rawness unlike anything else that was released at the time, and you couldn’t stroll down the streets of Chicago’s South Side without hearing Bang’s lyrics pulsing from the stereos of cars rolling by:

Choppers gettin' let off Now, they don't want no war 30 clips and them .45's, gotta go back to the sto' And that Kush gettin' smoked, gotta go back to the sto' Cock back 'cause there's trouble, my mans gon' blow

Yet he was almost completely unknown outside of Chicago. His Facebook profile had less than 2,000 followers, he claimed his occupation was “smokin’ dope” and he still lived with his grandmother.

Nevertheless, the verses written and hastily disseminated on social media by Chief Keef and his peers were fast becoming a unique sort of news ticker for low-income communities of color in Chicago, detailing the turf wars, rivalries and hassles of everyday life as a Black kid growing up in the city.

The songs became known as drill music , a genre characterized by its dark synths, booming 808 drums, seemingly off-beat, mumbled verses and war-cry choral chants. Its vanguards – artists like Chief Keef, King Louie, G Herbo and Lil Durk – emerged as local heroes by staying tethered to the blocks and neighborhoods they rapped about on SoundCloud and YouTube. Eventually, the national press caught on. The coverage was often less than flattering.

At the time, I was entrenched in my own hip-hop music career, rapping under the moniker Naledge in the duo Kidz in the Hall . As I was touring the country, I noticed that everyone from back home in Chicago was asking me if I’d heard of this kid Keef who was from Washington Park.

I knew that if a 16-year-old kid had the city buzzing, it would only be a matter of time before he was famous. What I didn’t know is that five years later, the drill subculture would be the subject of my field work as a doctoral student at Northwestern and that it would inspire me to write about the ways in which the city’s Black youth dealt with cultural, racial, economic and political oppression through inventive media production .

I started to argue, to anyone that would listen, that drill music was more than shock value or a new spin on gangsta rap. The scene planted the seeds for hip-hop’s ascendancy in music’s digital economy.

Drill goes viral

When Chief Keef’s house arrest ended, on Jan. 2, 2012, WorldStarHipHop posted a video of a young child in a hysterical fit of excitement, bounding around a room and rapping along to “Bang.”

The video of the boy went viral in the hip-hop community, and curious viewers furiously searched YouTube for more Chief Keef content.

Later that year, Chief Keef cemented his national reputation with the commercial success of his song “ I Don’t Like .” As the lead single for Chief Keef’s debut album, “Finally Rich,” “I Don’t Like” charted on the Billboard Hot 100 , accumulated tens of millions of listens online and helped drill break into the nation’s musical mainstream.

Within months of the song’s release, drill was seemingly everywhere. Hip-hop icons like Kanye West and Drake began co-signing drill rappers, while record labels instigated bidding wars over the South Side of Chicago’s budding rap talent.

At the time, drill music was still one of the only music scenes to exist almost exclusively on YouTube and free streaming sites like SoundCloud and DatPiff.com – a form of DIY distribution that circumvented the traditional gatekeepers of the rap music industry. Songs were churned out via singles, curated playlists, snippets and low-budget music videos that could be edited and released instantly by artists direct to their audiences via social media.

The most popular YouTube videos for drill songs were often shot in low-income apartments or on street corners , with the local crews standing behind the artist performing , pointing weapons at the camera and rapping about the recent events of ongoing street wars.

Initially, many journalists and researchers focused almost exclusively on how youth in the drill scene used their songs to perform “ internet banging ,” or threatening rival gang members and planning crimes over social media.

Media outlets like the Chicago Tribune, the Chicago Sun Times, Noisey , Pitchfork , Spin , The New York Times and WorldStar Hip Hop extensively covered the rise of Chief Keef and the drill scene, pointing to the violence inspired by the lyrics and the gang affiliations of the artists as the source of their viral appeal.

Police not only started monitoring the social media accounts of drill rappers, but also effectively banned Chief Keef from performing in his hometown by encouraging venues not to book drill rappers and telling promoters that they’d shut down drill shows.

The drill scene did incite violence. For example, in August 2020, drill rapper FBG Duck was murdered in the upscale Gold Coast neighborhood a year-and-a-half after threatening the O-Block street gang in a music video . In October 2021, the U.S. Attorney’s office for Northern Illinois indicted five members of the O-Block street gang for the murder, pointing out that the gang has “publicly claimed responsibility for acts of violence in Chicago” and “ used social media and music to increase their criminal enterprise.”

Rethinking the legacy of the drill scene

Though deaths like FBG Duck’s make headlines, my interviews with those affiliated with artists like Chief Keef have shown me that the gang violence associated with drill is hardly the reason these artists found success.

Instead, they wrote a blueprint for artists in hip-hop’s streaming era.

In the decade since Chief Keef became an “internet famous” rapper with the song “Bang,” a lot has changed in the music industry. There’s now no real demarcation between being a famous musician online and one who’s been elevated by the industry’s power brokers. Tekashi 69, Lil Yachty, 21 Savage, Juice WRLD and Lil Uzi Vert are just a few of the artists that built on the swagger, style, aesthetic and internet distribution model pioneered by Chief Keef.

Chief Keef was among the first to broadcast everyday life in Chicago’s gang territories to the world. His “ stream of consciousness ” style – saturating his YouTube channel videos of himself hanging out with his friends, meeting up with female fans, smoking marijuana and recording songs in his home studio – was a window into everyday life that’s been emulated by pretty much every pop star since.

Moreover, his willingness to give away music for free also paved the way for the “ SoundCloud era ,” in which artists like Chance the Rapper, Lil Pump and Doja Cat gained huge followings not through record deals, but through releasing tracks on SoundCloud.

Chief Keef’s unique slang and mumbled, melodic rapping style have also sparked drill youth movements in places as far away as Australia , London and Ghana .

Yes, Chief Keef’s story is out-of-the-ordinary: Getting in a shootout with police at the age of 15 and filming videos while on house arrest aren’t exactly common adolescent experiences. But his ability to present that story to the world and brand his style within a larger movement speaks to his genius.

In my forthcoming book project, I nod to the drill subculture that he spearheaded as reflecting the potential of Chicago’s Black youth. Denied full access to resources that might have helped them overcome their trauma and avoid gang lifestyles, Chief Keef and his peers used social media to persevere and make careers for themselves in music.

A lot that could be gained by not overlooking the creativity and ingenuity of teens and young adults like Chief Keef. He’s a perfect example of the ways in which young Black kids are unintentionally innovating within social media while simply navigating violence and poverty.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

Banner image photo credit: I t’s been 10 years since Chief Keef became an internet famous rapper with the song ‘Bang.’ Johnny Nunez/WireImage via Getty Images

Topics: Faculty , Research , Diversity , College of Information and Communications , The Conversation

Chief Keef: The Influential Drill Rap Pioneer

- by history tools

- November 19, 2023

Chief Keef‘s Profile

The Origins of a Chicago Icon

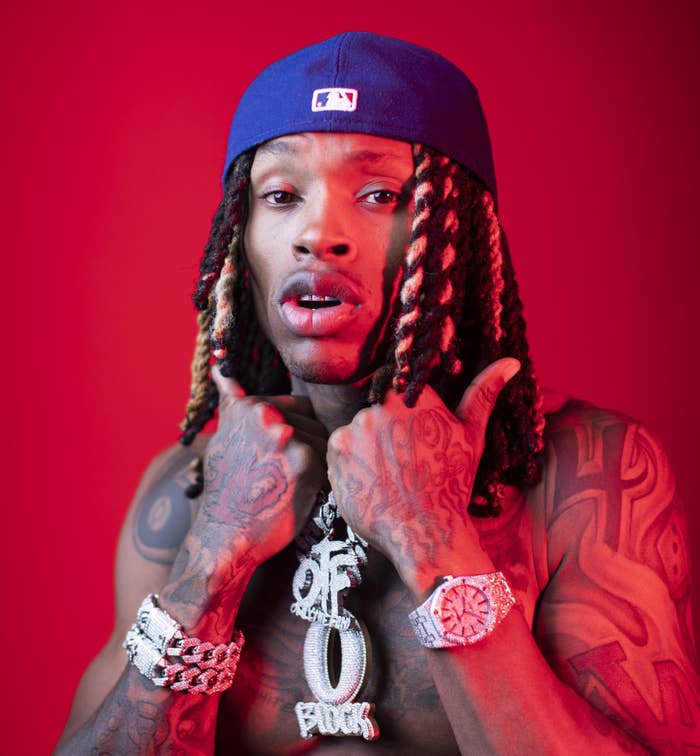

Keith Cozart was born in 1995 and raised in the crime-ridden Englewood neighborhood on Chicago‘s South Side. He began rapping at an early age, producing tracks while under house arrest as a juvenile for weapons charges. Keef started gaining local buzz with songs like "3Hunna" and "Bang" before exploding nationally with his snarling 2012 single "I Don‘t Like."

That track exemplified the Chicago drill sound with its booming 808s, frantic hi-hat patterns, and Keef‘s aggressive bars and masked vocals that oozed menace. It racked up millions of views on YouTube and led to a major label bidding war. At just 16, Keef signed a $6 million major label deal with Interscope Records and was propelled into stardom.

Finally Rich: The Debut Album That Defined a Genre

On December 18, 2012, a 17-year-old Chief Keef released his massively hyped debut studio album Finally Rich. Propelled by huge singles like "Love Sosa" and "Hate Bein‘ Sober," Finally Rich shot to #29 on the Billboard 200, selling over 50,000 copies in its first week.

From start to finish, Finally Rich was a groundbreaking album that laid the blueprint for drill music. Its production style created a grim, claustrophobic atmosphere with booming 808s, frantic hi-hat patterns, mournful piano melodies and layered synth textures. Meanwhile, Keef‘s lyrics eschewed typical gangsta rap braggadocio for a deadpan, aloof delivery depicting the bleak realities of Chicago street life.

Tracks like "Don‘t Like" and "Love Sosa" influenced a generation of artists like Lil Durk, King Von and Lil Reese while proving drill music had major commercial viability. Finally Rich‘s impact continues today through artists like Polo G, Lil Tjay and the late Pop Smoke who carry on its legacy.

"Chief Keef finally got it right on Finally Rich, finding a balance between his pitch-black street rap and pop crossover appeal" – Complex

Maintaining His Influence and Dedicated Following

In the years since Finally Rich, Keef has maintained his status as a cult icon with a devoted fanbase. He‘s continued releasing mixtapes and albums on his own Glory Boyz Entertainment label, often with little label promotion.

Despite keeping a relatively low profile in recent years, Keef has collaborated with artists like Kanye West, Gucci Mane, and Lil Wayne while retaining his reputation as drill music‘s forefather. His distinctive style and vocal delivery have become ubiquitous among younger rappers.

For Keef‘s loyal followers, myself included, his newest tracks and guest verses are events we eagerly anticipate. His independent, DIY approach has only added to his image as a wholly original artist. Despite label disputes and controversy, the "Chief Keef sound" he pioneered remains his lasting impact.

The Keys to Keef‘s Legacy

So why has Chief Keef remained such a vital, influential figure in hip hop? There are a few key reasons:

- He invented drill‘s distinctive sound and visual aesthetic. The production style, aggressive lyrics and dimly-lit music videos came to define the entire drill scene.

- He inspired a generation of artists with his unique style. Keef‘s influence is unavoidable in today‘s melodic rap — he‘s a forefather of the genre.

- He gave Chicago a distinctive hip hop identity. Keef became Chicago‘s first national rap star in decades and shined a light on its local scene.

- He succeeded independently via mixtapes and YouTube. Without label promotion, Keef grew an enormous fanbase online that remains loyal.

- He authentically portrayed life in his community. Keef rapped truthfully about the poverty, crime and hopelessness of Englewood and the South Side.

The Legacy Lives On

Over a decade since first emerging, Chief Keef remains one of the most influential rappers of the 2010s. He pioneered a hip hop subgenre and molded the "Chicago drill sound" we know today. Despite fading from the mainstream spotlight, his legacy as an innovator and cult icon lives on.

For devoted longtime fans like myself, Chief Keef and his extensive musical catalog will always remain in rotation. I‘m excited to see how his legacy continues to unfold and the next wave of artists he inspires with his vision and gift for raw, authentic hip hop. Keef‘s influence will no doubt be felt as long as young MCs seek to capture the spirit of his brazen, brilliant teenage years when drill was born.

Related posts:

- Drake: The Chart-Topping Canadian Rap Superstar

- Bad Bunny: The Boundary-Breaking Latin Trap Icon

- Lil Peep: The Rapper Who Pioneered Emo-Influenced Hip Hop

- The Incredible Journey of The Kid Laroi: Rap‘s Rising Star

- Lil Yachty: The Boundary-Breaking Prince of Hip Hop

- the Multitalented Han Jisung

- Trippie Redd: The Unique SoundCloud Pioneer

- Saweetie – The Icy Girl Taking Over Hip Hop

Join the conversation Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

WELCOME TO THE FAMILY! Please check your email for confirmation from us.

Entertainment

Drugs, guns and gangs: How rapper Chief Keef represents bloody Chicago culture

OPINION - In the span of two weeks Chicago-based rapper Chief Keef has been demonized by a variety of media publications...

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share via Email

- Copy Link Link Copied

In the span of two weeks, Chicago-based rapper Chief Keef has been demonized by a variety of media publications. They have attacked the content in his music, his negative image and even his young mother (she’s 32) for being what some have called an irresponsible parent for condoning her son’s erratic behavior.

What’s missing from the discussion that scrutinizes his every tweet is what circumstances birthed him and how he was able to massively capitalize on a murder culture while being on house arrest in America’s murder capital.

Last week Chicago police arrested 300 people and recovered 100 weapons in a 3-day gang and drug raid and March, May and August all recorded more than 50 homicides; 2012 saw homicide victims in the city outnumber troops killed in Afghanistan . It is no secret that the violence in Chicago has been linked to gang activity. Last year the most frequent murder offenders were 17 and 18 years old.

The Chicago Tribune reports :

Annual Chicago police statistics show a majority of both homicide victims and offenders are young black men with criminal records… A deeper review of the numbers shows males ages 15 to 35 made up nearly three-quarters of African-American homicide victims… In communities where the cycle of violent crime — disputes, violence and retaliation — has become the norm, young people who have seen too much death develop hardened attitudes about violence startlingly early.

Over the past few years, Chief Keef’s Englewood neighborhood has experienced almost 150 deaths. Being a 16-year-old kid on house arrest in this deadly community, creating songs like “Bang” while pantomiming firing a gun and reciting lyrics such as “choppas get let off, they don’t want no war, throwing clips from the 4-5 gotta go back to the store,” he makes it easy to imagine that the people who are sparking the violence in the city look similar to him and have a similar background. Lupe Fiasco touched on this last week when he was interviewed about Chicago artist by a Baltimore radio station. Fiasco stated :

Chief Keef scares me. Not him, specifically but just the culture that he represents, specifically in Chicago…When you drive through Chicago, the hoodlums, I don’t want to call Chief Keef a hoodlum, but the hoodlums, the gangstas and the ones you see killing each other, the murder rate in Chicago is sky-rocketing, when you see who’s doing it and perpetrating it, they all look like Chief Keef. He looks just like Chicago…he could be any kid on the street…To hear the things that he rap about specifically comparing it to you open up the news papers and there is 22 shootings this weekend, it scares me.

After hearing Lupe’s comments, Keef took to Twitter and wrote:

Lupe Fiasco a h*e a$$ ni**a and when I see him I’m a smack him like da lil b*tch he is #300.

Violence is what he knows and violence is what he is advocating, and he makes no apologies for it. Lupe responded to Keef via Twitter with a touching declaration to make peace and ended his portion of the conversation by unveiling that his album Food & Liquor II: The Great American Rap Album Pt. 1 , to be released September 25 via Atlantic, will probably be his last. Lupe wrote:

But my heart is broken and i see no comfort further along this path only more pain. I cannot participate any longer in this … My first true love was literature so i will return to that … lupe fiasco ends here.

- Share on Facebook Facebook

- Share on Twitter Twitter

- Share via Email Email

- Copy Link Copy Link Link Copied

STREAM FREE MOVIES, LIFESTYLE AND NEWS CONTENT ON OUR NEW APP

Find anything you save across the site in your account

11 Songs That Define Chicago Drill, the Decade’s Most Important Rap Subgenre

By Alphonse Pierre

In the summer of 2012, as Chief Keef ’s momentum was picking up steam, a Chicago teenager tearfully and angrily addressed the critiques of his favorite rapper in a viral video filmed from the passenger seat of a parked car. “Fuckers in school always telling me, always in the barbershop, ‘Chief Keef ain’t ’bout this, Chief Keef ain’t ’bout that,’” he screamed. “Shut the fuck up!” Months before, another inescapable Keef-related video had been uploaded to WorldStarHipHop . This clip featured a younger boy, profanely delirious like he’d just won the lottery. “Chief Keef is outta prison!” he squeals. At the time, Chief Keef was 16 years old, with a bubbling street single . He was stuck in his grandmother’s Southside Chicago apartment on house arrest for gun charges. He was nothing more than a local sensation, unknown to just about anyone that didn’t attend a Chicago high school. These two videos were an introduction to the fandom behind Chief Keef. A teenage rapper, leading a burgeoning scene categorized as drill music—taken from the slang usage of “drill,” meaning to shoot someone—who was telling firsthand stories of the violent, gang-dominated Chicago culture that reflected a city with an ongoing history of segregation and neglect of the black community.

That spring, Chief Keef released “I Don’t Like” and drill had its breakthrough moment. Major labels invaded the city: Keef signed a $6 million deal with Interscope; Lil Reese and Lil Durk , members of Keef’s GBE crew, inked deals with Def Jam; and fellow Chicago rapper King Louie signed with Epic. But, later in the year, when Keef released his debut album, Finally Rich , it sold only a disappointing 50,000 copies in its first week . The music industry overreacted, declaring drill a fad. But, like Chicago rap critic David Drake points out in his essay for The Outline , drill’s popularity wasn’t fleeting. Rather, the issue was Billboard ’s methods of quantifying listening at the time. Drill was one of the first music scenes to exist almost exclusively via videos and streaming; physical CDs and iTunes downloads were irrelevant. Billboard didn’t begin to adapt its metrics until early 2013 .

While the mainstream music industry was questioning the legitimacy of the genre, drill was busy setting the precedent for hip-hop for the rest of the decade. The scene was based around singles, snippets, leaks, and low-budget music videos that could be edited and released instantly—often shot in apartments or on street corners, with the local crew pointing weapons at the camera. The rapping was no frills and tough. The production, established by names like Young Chop and DJ L, incorporated rapid drums, sirens, and church bells, with melodies straight out of a Freddy Krueger nightmare. Drill birthed a flourishing community of producers who replicated its sound and sold their beats on YouTube.

As the music spread across the internet, so did the backlash and controversies. Keef was heavily criticized for mocking the murdered rapper Lil Jojo after his death. He was jailed on a probation violation for holding a rifle during a Pitchfork video filmed at a gun range. (Pitchfork later retracted the video .) L’A Capone was killed in 2013, Young Pappy in 2015. RondoNumbaNine was sentenced to 39 years for murder in 2016 and Famous Dex, a year into his rise, was filmed physically abusing his girlfriend . The stories were often sad, teenage rappers forced to grow up early thrust into the spotlight. Some were against the genre’s candid depiction of violence, but this was the real world these rappers lived, and thus rapped about, a world borne of conditions that racism helped to create. In 2016, Chicago’s violence epidemic reached a bleak milestone of 700 murders in a calendar year, the most in nearly two decades. (Recently, that number has encouragingly decreased .) Drill had to learn to adapt, to take control of its image, while it was in the midst of changing music.

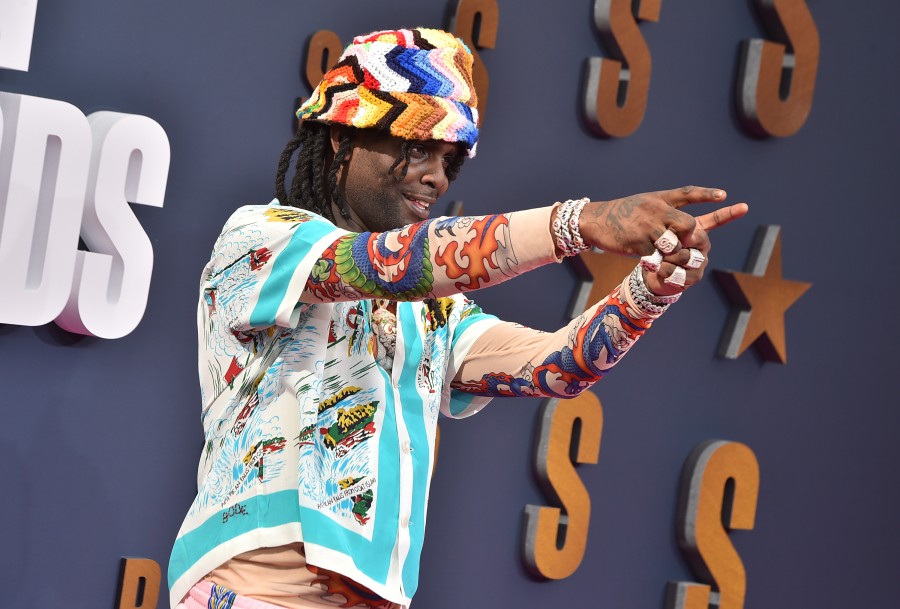

By the end of the decade, drill had gone global. The UK, Brooklyn, Ireland, Boston, and other locales all developed drill scenes of their own. Looking at the past decade in hip-hop, it’s arguable no scene has been as impactful. “The drill scene, I was so influenced by that, that was all I was listening to,” said Cardi B, about her rise in a Rap Radar Podcast interview .

Here, we take a look back—from King Louie’s “Gumbo Mobsters” to the recent emergence of Polo G —and tell the story of the decade’s most influential rap subgenre through its signature moments.

King Louie and Bo$$ Woo: “Gumbo Mobsters” (2011)

“Gumbo Mobsters” arrived nearly a year before Chief Keef broke through, giving an early introduction to the lifestyle through the duo’s lyrics about “drilling”: “Talkin’ shit we come see you/Real G shit, my lil Gs evil,” says Louie, expressionless. Only eight years later, several lifetimes in hip-hop, the song feels thoroughly dated. In the video, the two Chicago rappers post up in white tall tees—they both look like side characters in the 2006 T.I. movie ATL — and rap over horns that sound like hip-hop radio 15 years ago.

Shady: “Go In” (2011)

A wave of women helped put drill on the map before Keef arrived. Among them was Shady, whose single “Go In” became an instant street classic. In the music video, director D Gainz perfected his manic, handheld shooting style, capturing all the girls on the block, out in the local chaos, in their gleefully mad comfort zone (one girl keeps up even while on crutches). On the track, Shady gets two points across: the threats that come out of her mouth are very real, and she will look good while acting on those threats. The video also features the immortal scene of teenage rapper Katie Got Bandz, who would later drop drill classics like “ I Need a Hitta ” and “ Pop Out ,” joyfully swaying back and forth while gripping a miniature handgun. “Yeah, it’s real, but that was the old me,” Katie would later say in an interview . “That’s not me anymore.” Regardless, her cameo has turned into a popular GIF.

Chief Keef: “I Don’t Like” [ft. Lil Reese] (2012)

“I Don’t Like” set the blueprint. Chief Keef’s flow is unrushed, moving at the pace of someone who has had about one or five too many. His lyrics are bitter, he hates every single thing: snitches, fake True Religion, and people that don’t like him solely because he doesn’t like them. He’s shirtless in the iconic video, swinging his short dreads, trying to keep his jeans above his knees. The Young Chop beat is cinematic, and now endlessly mimicked. After “I Don’t Like,” the floodgates opened.

Lil Herb and Lil Bibby: “Kill Shit (2012)

On “Kill Shit,” Lil Herb and Lil Bibby are high-energy but emotionless, like the bleak stories they narrate are so normal they could be told with a yawn. The two teen rappers have deep, raspy voices that make them sound like a pair of 50 year olds trying to shake a Newport 100s habit, yet somehow they still maintain a shade of innocence. In three minutes, we learn about their difficult coming of age, a narrative relayed without sacrificing any of their swag. Hooks are unnecessary to the duo, as their one-liners are strong enough to neccesitate repetition on their own: “Know a couple niggas that’s down to ride for a homicide when it’s drama time,” says Herb.

Lil Durk: “Dis Ain’t What U Want” (2013)

On his 2013 mixtape Signed to the Streets, Lil Durk introduced more traditional melody to drill. Durk’s voice was always light and begging for him to take control of his natural rhythm. On “Dis Ain’t What U Want,” Durk does exactly that, without abandoning the street shit: “Daddy doin’ life, snitches doin’ months,” he sings, with Auto-Tune. That this song, with its poppier style, became so anthemic shows drill was more than a particular sound, but a feeling.

L’A Capone and RondoNumbaNine: “Play for Keeps” (2013)

In a 2012 FADER story , King Louie explained the difference between himself and Chief Keef and crew: “Them lil’ niggas wild.” The following year, L’A Capone and RondoNumbaNine emerged as kids even younger and wilder. “Play for Keeps” set the tone for an era that featured rappers barely into their teens writing violent, crime-riddled lyrics that most kids their age couldn’t even comprehend. Their aggression is startling, and sometimes off-putting, but it captured the feeling of an environment that rips away your childhood before you’re ready: “Deadbeat pops got raised by the block,” raps RondoNumbaNine. Like so many Chicago drill artists, their story reached a tragic end: L’A Capone was murdered in 2013 and RondoNumbaNine was sentenced to 39 years in jail for murder in 2016 .

Chief Keef: “Faneto” (2014)

On Halloween of 2014 , Keef released his most influential (and arguably best) mixtape, Back From the Dead 2 . The mixtape was Keef diving further into his narcotized delivery, straying more off beat, and taking a looser approach to song construction. “Faneto” is the mixtape’s centerpiece. The self-produced track is packed with signature Keef moments, including his never-ending beef with the entire state of New Jersey, and the most reckless 30 seconds of ad-libs that he’s ever recorded. For the next year, the rap internet was flooded with infinite remixes of the track, raising the profile of nearly every rapper that graced the beat (see: Young Pappy and Famous Dex ). Drill was not a trend. Chief Keef was not a fad. “Faneto” made that indisputable.

Young Pappy: “Killa” (2014)

The late Young Pappy was drill’s underdog. Maybe it was that he hailed, atypically for a drill rapper, from Chicago’s Northside, or maybe it was that his demon-voiced delivery felt like an evolution for the genre. In 2014, Young Pappy went on a run that established the untamed aggression and angst that would later influence the likes of Tay-K (“I’m a shooter like Young Pappy,” says Tay-K on “The Race”). “Killa” is Pappy’s essential track, a three-and-a-half minute journey of the rapper saying the dirtiest shit he can pull from his brain over a manipulated vocal sample and the quintessential drill drum kit.

Famous Dex: “2 Times” (2015)

Before Famous Dex became the disgrace of Chicago drill, he released a string of essential tracks. On “2 Times,” Dex raps with a more character-based approach, a change from drill’s typical deadpan. Dex’s persona later made him the perfect fit for emerging director Cole Bennett, as Dex’s later videos helped to launch the Lyrical Lemonade universe that has since made breakout videos for Lil Tecca, Lil Pump, and Blueface. Early tracks like “2 Times” made the bridge between Chicago drill and the SoundCloud generation possible.

FBG Duck: “Slide” (2018)

FBG Duck’s “Slide” arrived at a time when the drill scenes in both the UK and Brooklyn were picking up steam, but his 2018 single is a reminder that the home of drill will always be Chicago. On the song, Duck perfects a sing-song whisper delivery while shooting a traditional drill video featuring hooded dudes pointing weapons at the camera that could have been recorded in any year throughout the 2010s.

Polo G: “Battle Cry” (2019)

Polo G is the most accessible drill rapper since Chief Keef. He’s managed that through a songwriting approach that’s both structured and self-critical—and a love for softer pianos. His music is heavily aware of the Deep South’s current wave of street tales by the likes of Youngboy Never Broke Again and Kevin Gates, but his influences are distinctly Chicago: the underdog mentality of Young Pappy, G Herbo’s storytelling, and a sense for melody that surpasses even Lil Durk. “Battle Cry” is a song that sounds both of his city and the internet. It’s proof that drill didn’t peak the moment Keef signed that dotted line in 2012 like so many had thought. Instead, the genre has become ingrained into rap’s culture, and continues to impact rising generations as we head into the next decade.

.png)

By Pitchfork

By Rawiya Kameir

By Eric Harvey

.jpg)

By Jason King

By Madison Bloom

By Jazz Monroe

- Manage Account

Chief Keef Talks Working With Sexyy Red & Mike Will Made-It, ‘Almighty So 2’ & More | Billboard News

- Share this article on Facebook

- Share this article on Twitter

- Share this article on Flipboard

- Share this article on Pinit

- + additional share options added

- Share this article on Tumblr

- Share this article on Reddit

- Share this article on Linkedin

- Share this article on Whatsapp

- Share this article on Email

- Print this article

- Share this article on Comment

Chief Keef opens up about working with Sexyy Red and Mike Will Made-It, his upcoming album Almighty So 2 and more backstage at Rolling Loud 2024. Chief Keef: Saying she wants to come through and I said, “hell f–king yeah.”

Oh s–t. I’ve been working on that s–t man. It’s actually dope, man.

Man, you know, but when I do go on tour, I mean, I’d be ready to go home.

Tetris Kelly: Chief Keef is the epitome of a mood, and from following him to his juiced set at Rolling Loud and heading backstage with him and Mike Will Made-It. It was down with the man Sosa and Billboard News. Arriving just before his set, everybody — and I mean everybody — was excited for Chief Keef at Rolling Loud, and he ran to the stage to give the people what they want.

And right afterwards, he was in high demand, as he doesn’t do press often, but Billboard was able to hop in the van with the legend for some hilarious shenanigans.

Unknown Speaker: He hit that bih like Tom Cruise.

Tetris Kelly: To cruise backstage and chat all about the show and his new project. Hanging out backstage with Chief Keef at Rolling Loud. Man, the festival has been such a vibe. The fans was loving your set. How was it up there, man?

Chief Keef: Always dope. It’s always loud. Rolling Loud.

Tetris Kelly: I mean, you had Sexyy Red up there, man. How did you guys start working together? It was so good.

Chief Keef: S–t.I just know she f–k with me real heavy. I f–k with her too. Saying she wants to come through and I said “hell f–king yeah.”

Tetris Kelly: And I mean what do you think it is about her that has like made people go so crazy for Sexyy Red?

Chief Keef: She just … you could tell she really just come from where we come from.

Tetris Kelly: I feel you on that, man. Then also you know you just dropped “Dirty Nachos” with Mike Will Made-It, so what made y’all decide to collaborate on a project together?

Chief Keef: That’s my dog. He right up there. Where he at? That’s my boy.

Tetris Kelly: And the fan reaction has been great. How’s it feel to finally have the project out there?

Chief Keef: Man, it ain’t even just … that ain’t even what we suppose to been drop. That just what he decided, you know what I’m saying? Let’s just drop something before we do what we suppose to drop. Yeah, man, like I said, that my mans and we always got together and we always working too.

Tetris Kelly: And then you got Almighty So like the sequel, to part two coming out, man. So tell me what the fans gonna expect from that.

Chief Keef: Oh s–t. I’ve been working on that s–t, man. It’s actually dope, man. Got some different stuff on it.

Tetris Kelly: Got some features you can tease us with a little bit?

Chief Keef: Yeah, I got some features on there, but I just want to, you know, keep it a surprise if they don’t know already. Watch the full interview above!

A daily briefing on what matters in the music industry

Billboard is a part of Penske Media Corporation. © 2024 Billboard Media, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

optional screen reader

Charts expand charts menu.

- Billboard Hot 100™

- Billboard 200™

- Hits Of The World™

- TikTok Billboard Top 50

- Song Breaker

- Year-End Charts

- Decade-End Charts

Music Expand music menu

- R&B/Hip-Hop

Culture Expand culture menu

Media expand media menu, business expand business menu.

- Business News

- Record Labels

- View All Pro

Pro Tools Expand pro-tools menu

- Songwriters & Producers

- Artist Index

- Royalty Calculator

- Market Watch

- Industry Events Calendar

Billboard Español Expand billboard-espanol menu

- Cultura y Entretenimiento

Honda Music Expand honda-music menu

The Lasting Legacy Of Chief Keef’s “I Don’t Like” Video

The house that acts as a backdrop to Chief Keef ’s “I Don’t Like” doesn’t look lived in. The interior design is sparse to the point of vacantness; the space is so clean it feels sterile. Take a glance through the window of Youtube and one thing comes through clearly: there was never any love in that house.

This suburban dwelling is the antithesis of what had been expected from an archetypal rap video prior to 2012, when “ I Don’t Like ” smashed the template forever. Now, the (presumably) Chicago building ought to be up for historical landmark status so it’s eternally protected.

“I Don’t Like” captures Chief Keef (né Keith Cozart) and his crew at their wildest. They smoke weed, flash their ink, count money stacks, mosh topless to Young Chop’s punishing beat. Co-star Lil Reese is seen in a blood-red hoodie — a vibrant contrast to Keef’s blue denim. The one gun the squad appear to have between them is aimed at the camera’s lens intermittently. Grainy production techniques are often deployed to give rap videos a raw feel. Here, the clear picture and close-up focus on its subjects only heightens the video’s in-your-face intimacy. There is no narrative or veiled messages. Just teenagers made of blood, bone and wrought iron. Young men in adult bodies but not yet with grown-up minds.

“I Don’t Like” wasn’t the first inexpensive rap video deployed on the internet. The likes of Odd Future and Lil B spent the early shots of the 2010s making rusty clips that felt low budget, low stakes, and fit a kind of Tumblr post aesthetic. Just 16 years old, Keef set a new bar on how immediate and impactful cheap clips could be. Coming a year after director and rap video legend Hype Williams dropped one of his most ambitious projects ever in Kanye West’s “Runaway,” director DGainz’s simplified production marked the spiritual end of the big-budget, bling-bling rap video era, and established a model that young stars have been drawing from ever since.

Evolving tech and economics played a part in the production of “I Don’t Like” and its subsequent influence. The internet, combined with cheaper recording equipment, allowed burgeoning artists to bypass the gatekeepers at MTV. Labels cut back, too. After the bottom fell out of music sales, companies couldn’t put up the kind of budgets that could turn Busta Rhymes into a sperm-like creature anymore. Conceptual videos with cinematic ideas but without the production values can often feel cheap and cringy. You can, though, stunt to camera for virtually no money at all.

“I Don’t Like” is the archetype. As with any good music clip, the song sets the tone — Young Chop’s sledgehammer drums and skyscraping, hard-angle keys matched with Keef’s short, catchy bars were stark, uncompromising, and totally undeniable. From there, DGainz captures the personality, the energy, the sense of don’t-give-a-f*ck teen rebellion.

The lack of women in a music video genre that has traditionally commodified female bodies is striking. Not entirely unspoken at the time of the release of “I Don’t Like” was the homoerotic streak that runs through it. Within the all-male space is a palpable sense of intimacy, both physical and spiritual. It’s a raw depiction to young masculinity that seemed to capture the humanity behind the headlines coming out about young Black males in Chicago at the time.

Viral impact helped make “I Don’t Like” into the single most influential Chicago drill song and, by extension, synonymous with Chicago violence. Reports from the city made grim reading. 2012 was the height of the hysteria, when South Side Chicago became a maxim for urban mismanagement. Images from clips like “I Don’t Like” promised to put faces to the statistics. Just a few months before recording the video that would launch his rap star, Keef was reportedly shot at by cops after flashing a blue-steel handgun at the officers. In an alternate timeline, his story ends there and rap history takes a different course.

The influence of drill on contemporary rap was immense. It pulled trap into an even starker ethos than before. Drill’s core tenets can be strongly felt these days in the fashionable sounds of Soundcloud rap. And the effect of the “I Don’t Like” video has continued to percolate. Five years after its release, 6ix9ine’s video for his viral hit “Gummo” recycled the same elements: the lack of overarching narrative, the stunting towards camera, the general menace. Lil Peep’s “Benz Truck” proved you didn’t need a storyline to wear a synthetic pink and green fur coat and pull shapes in front of The Kremlin.

Life hasn’t been as straightforward for the young stars of drill. Built on the artistry of often troubled kids, the scene largely burned itself out. By the end of 2012, a disturbing and brutal video allegedly showing Lil Reese assaulting a woman was posted to the internet. As for Keef, his career has struggled to gestate among a lengthy rap sheet. He may have flamed off of Interscope, but he’s remained prolific and, at still only 24-years-old, his recent work has shown renewed promise.

Regardless, Keef’s place in hip-hop lore is forever established. He’s the kid who took the harsh realities of his native soil, alchemized it into something that could punch through a monitor or smartphone screen, and created one of rap’s great visual requiems.

Rhymefest Slams Chief Keef in Online Essay

Chief Keef crossed a major milestone earlier this month when he announced that he'd signed a deal with Interscope Records , but not all of the rapper's peers are breaking out the champagne. In a pointed essay published today on the blog Analog Girl In A Digital World , fellow Chicago emcee Rhymefest denounces Keef's music for promoting senseless violence and criticizes Interscope and radio stations for promoting him. "Chief Keef is a 'Bomb'," the essay begins. "He represents the senseless savagery that white people see when the news speaks of Chicago violence. A Bomb has no responsibility or blame, it does what it was created to do; DESTROY! Notice, no one is talking about the real culprits, the Bomb maker or the pilot who is deploying this deadly force (Labels, Radio Stations). It’s easier to blame the bomb. Bombs are not chosen for their individual talents, they are tools used for collateral damage." Fest goes on to condemn the 17-year-old rapper as a "spokesman for the prison industrial complex," a tag he similarly applies to Rick Ross and Waka Flocka Flame. The veteran rapper and one-time mayoral candidate preemptively dismisses the counter-argument that Keef is setting himself up to have a better life and successful career. "This could only be described as an opportunity for this young man if he was recieving artist development, responsible mentorship and counseling for his obvious trauma," he declares. Instead of promoting Keef and his ilk, Rhymefest argues that more attention should be paid to artists who do good, such as Killer Mike , Lupe Fiasco , Brother Ali and himself.

BET.com is your #1 source for Black celebrity news, photos, exclusive videos and all the latest in the world of hip hop and R&B music.

Click here to subscribe to our newsletter.

Download the BET Awards App to relive the entire history of the BET Awards in video & pics and to POWER vote for Viewers’ Choice and Who Rocked The Mic!

(Photos from Left to Right: Brian Ach/WireImage, courtesy Glory Boy Entertainment)

Latest News

Pharrell Williams and Chad Hugo in Legal Battle Over The Neptunes Name

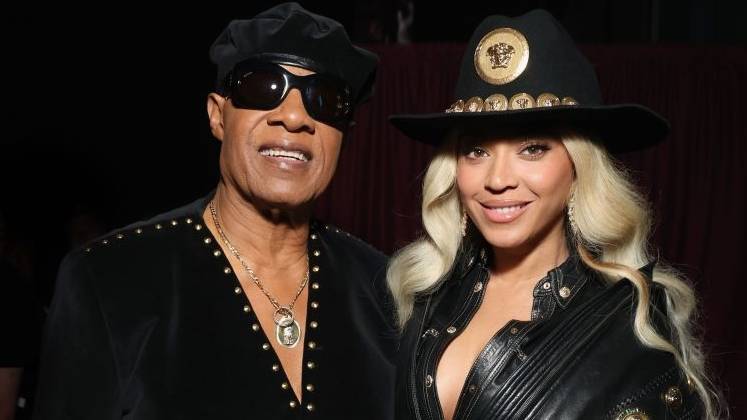

Stevie Wonder Presents Beyoncé With The Innovator Award At The iHeart Radio Music Awards

Ledisi Talks Her New Album ‘The Good Life’, and Why She Will Never Be Boxed In

Noochie's Front Porch Revolution: Elevating Live Performance Culture

World Autism Day 2024: How These Celebrities Use Their Star Power to Raise Autism Awareness

'Snowfall' Alum Angela Lewis is on a Mission to Fix the Black Maternal Health Crisis

Subscribe for bet updates, provide your email address to receive our newsletter..

By clicking Subscribe, you confirm that you have read and agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Policy . You also agree to receive marketing communications, updates, special offers (including partner offers) and other information from BET and the Paramount family of companies. You understand that you can unsubscribe at any time.

Drill rap is on trial. But is the message behind the music getting lost in the hysteria?

- Culture & The Arts

In an essay, a digital innovation professor and South Side youth educator argue that the moralizing about drill rap’s glorification of violence obscures the stories of loss and frustration from the artists behind the music.

Christopher Thomas has a vivid memory of the first time he heard drill music. In 2011, he was working at Nancy B. Jefferson Alternative School within Cook County Juvenile Detention Center, aiming to inspire incarcerated youngsters with footwork and other forms of hip-hop culture.

One afternoon, he offered to play a DVD by his group, the FootworKINGz, to connect with the teenagers who were there. Before he played the video, one of the young people made an offer to Thomas, a 39-year-old street dancer and youth educator who grew up in Altgeld Gardens on the South Side and is called “Mad Dog” by his peers. “This one cat said ‘We’ll do whatever you want us to do, if you let us listen to one song.’ I was like, I can meet those terms. And the song was ‘I Don’t Like.’ ’’

The teenager who made that bargain was none other than Keith “Chief Keef” Cozart, a then-15- year-old in the youth detention center. It was Keef’s own song, but it would be another year before the rapper released the video for it, filmed while he was on house arrest at his grandmother’s home. That video would go viral, catapulting the teenager — and Chicago drill — to national attention in just a few months.

- RELATED STORY

- Criminal Justice

Entertainment or evidence of a criminal enterprise? Drill rap takes center stage in FBG Duck murder trial.

Drill music is known for its epic, swelling horror-soundtracks, and rough-hewn testimonials on street life, and often gets criticized for lyrics and videos with gang disses and references to alleged crimes. Outside of the United States, drill has gone viral in the last five years, with artists claiming the genre from as far-flung places as Ghana, Germany and Japan. Along with the enthusiasm for its propulsive music and at times dark themes, a law enforcement response and moral panic has ensued that is at times not unwarranted. Lyrics and videos are now centerstage in two prominent U.S. trials: one in Chicago, related to the killing of FBG Duck, and in an Atlanta case surrounding Young Thug.

As scholars and youth educators, we recognize the fervor over links between violence and the music. But that fervor obscures the message of loss and frustration from the young artists and the audiences responding to it. Drill’s critics are often not hearing the pain seething beneath the sound.

Today, Mad Dog works as a program manager with Kuumba Lynx, a nonprofit that trains Chicago youth for arts careers. He remembers that moment back at the detention center with some joy. “I ain’t gonna lie, I said ‘This is tight!’ In seconds, the guys were just turning up in the space. They were singing the song, and I started jumping around with them. The next thing you know, the security is jumping around, dancing, and we all start turning it up.”

Even so, he despises “the celebration of Black death” by the record industry, as well as drill culture’s over-the-top gun bravado, calculated for maximum clicks online. But he also argues that drill music is a release for young people dealing with generations of gun violence and systemic racism.

“Is it wrong for him to say the things he don’t like?” Thomas said, referencing the refrain in Keef’s breakout hit. “He’s basing it off his living conditions, where he stays at, where he can and cannot go. Because he has folks that look just like him, in the same living condition as him, wanting to kill him.”

Drill’s global virality

In its original form, drill music emerged out of conditions where people felt hopeless and life felt tenuous. This darker sound achieved national recognition with artists such as Keef and Young Chop in the mid 2010s as well as King Louie, who coined the term “Chiraq.”

The rap style has become global in the last five years with adoption of the genre in Britain. South London’s zany and techno-ish versions made U.K. drill positively exotic for the international crowd, aided in no small part by England’s famously sensational music press and public arts programs. Lighter, more club-oriented drill tracks have emerged along with viral dances such as the Gun Lean and the Sturdy, which have become a favorite celebration for some professional athletes.