Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Taiwan sees warning signs in weakening congressional support for Ukraine

How dating sites automate racism

Forget ‘doomers.’ Warming can be stopped, top climate scientist says

Do phones belong in schools.

iStock by Getty Images

Harvard Staff Writer

Bans may help protect classroom focus, but districts need to stay mindful of students’ sense of connection, experts say

Students around the world are being separated from their phones.

In 2020, the National Center for Education Statistics reported that 77 percent of U.S. schools had moved to prohibit cellphones for nonacademic purposes. In September 2018, French lawmakers outlawed cellphone use for schoolchildren under the age of 15. In China, phones were banned country-wide for schoolchildren last year.

Supporters of these initiatives have cited links between smartphone use and bullying and social isolation and the need to keep students focused on schoolwork.

77% Of U.S. schools moved to ban cellphones for nonacademic purposes as of 2020, according to the National Center for Education Statistics

But some Harvard experts say instructors and administrators should consider learning how to teach with tech instead of against it, in part because so many students are still coping with academic and social disruptions caused by the pandemic. At home, many young people were free to choose how and when to use their phones during learning hours. Now, they face a school environment seeking to take away their main source of connection.

“Returning back to in-person, I think it was hard to break the habit,” said Victor Pereira, a lecturer on education and co-chair of the Teaching and Teaching Leadership Program at the Graduate School of Education.

Through their students, he and others with experience both in the classroom and in clinical settings have seen interactions with technology blossom into important social connections that defy a one-size-fits-all mindset. “Schools have been coming back, trying to figure out, how do we readjust our expectations?” Pereira added.

It’s a hard question, especially in the face of research suggesting that the mere presence of a smartphone can undercut learning .

Michael Rich , an associate professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and an associate professor of social and behavioral sciences at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, says that phones and school don’t mix: Students can’t meaningfully absorb information while also texting, scrolling, or watching YouTube videos.

“The human brain is incapable of thinking more than one thing at a time,” he said. “And so what we think of as multitasking is actually rapid-switch-tasking. And the problem with that is that switch-tasking may cover a lot of ground in terms of different subjects, but it doesn’t go deeply into any of them.”

Pereira’s approach is to step back — and to ask whether a student who can’t resist the phone is a signal that the teacher needs to work harder on making a connection. “Two things I try to share with my new teachers are, one, why is that student on the phone? What’s triggering getting on your cell phone versus jumping into our class discussion, or whatever it may be? And then that leads to the second part, which is essentially classroom management.

“Design better learning activities, design learning activities where you consider how all of your students might want to engage and what their interests are,” he said. He added that allowing phones to be accessible can enrich lessons and provide opportunities to use technology for school-related purposes.

Mesfin Awoke Bekalu, a research scientist in the Lee Kum Sheung Center for Health and Happiness at the Chan School, argues that more flexible classroom policies can create opportunities for teaching tech-literacy and self-regulation.

“There is a huge, growing body of literature showing that social media platforms are particularly helpful for people who need resources or who need support of some kind, beyond their proximate environment,” he said. A study he co-authored by Rachel McCloud and Vish Viswanath for the Lee Kum Sheung Center for Health and Happiness shows that this is especially true for marginalized groups such as students of color and LGBTQ students. But the findings do not support a free-rein policy, Bekalu stressed.

In the end, Rich, who noted the particular challenges faced by his patients with attention-deficit disorders and other neurological conditions, favors a classroom-by-classroom strategy. “It can be managed in a very local way,” he said, adding: “It’s important for parents, teachers, and the kids to remember what they are doing at any point in time and focus on that. It’s really only in mono-tasking that we do very well at things.”

Share this article

You might like.

Ambassador says if Russia is allowed to take over sovereign nation, China may try to do same

Sociologist’s new book finds algorithms that suggest partners often reflect stereotypes, biases

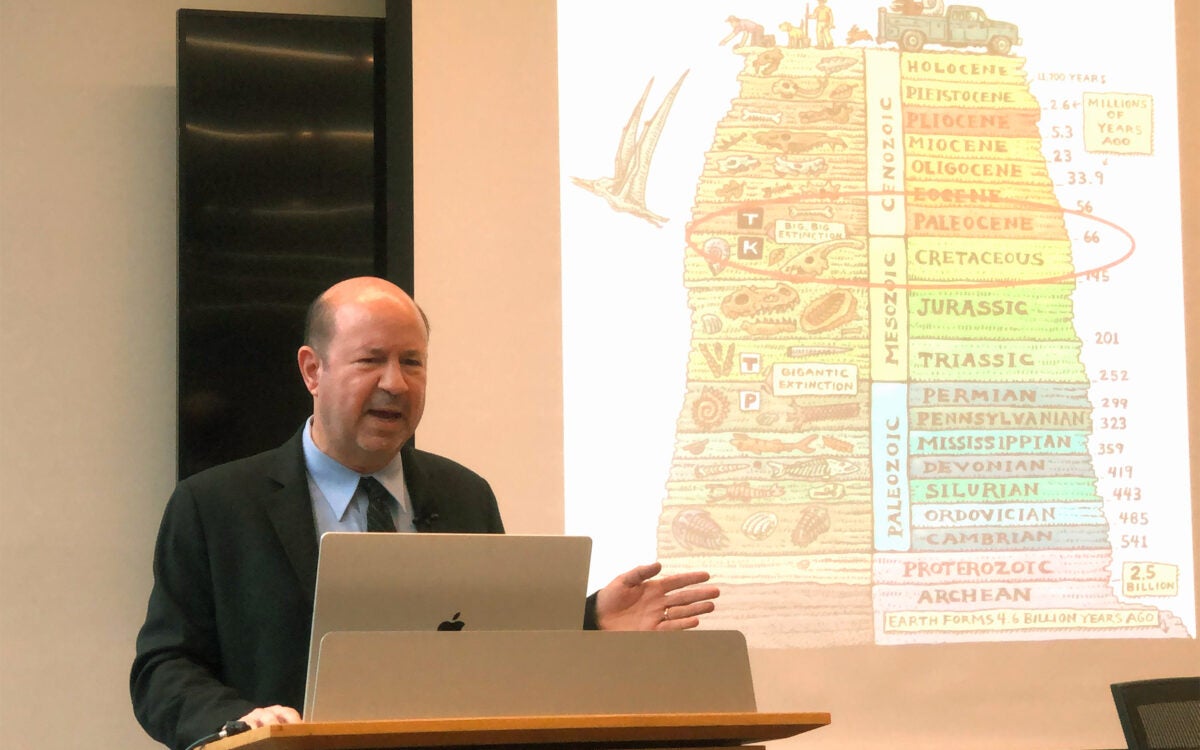

Michael Mann points to prehistoric catastrophes, modern environmental victories

Yes, it’s exciting. Just don’t look at the sun.

Lab, telescope specialist details Harvard eclipse-viewing party, offers safety tips

Navigating Harvard with a non-apparent disability

4 students with conditions ranging from diabetes to narcolepsy describe daily challenges that may not be obvious to their classmates and professors

Why Schools Should Ban Cell Phones in the Classroom—and Why Parents Have to Help

New study shows it takes a young brain 20 minutes to refocus after using a cell phone in a classroom

Photo by skynesher/iStock

Parents, the next time you are about to send a quick trivial text message to your students while they’re at school—maybe sitting in a classroom—stop. And think about this: it might take them only 10 seconds to respond with a thumbs-up emoji, but their brain will need 20 minutes to refocus on the algebra or history or physics lesson in front of them— 20 minutes .

That was just one of the many findings in a recent report from a 14-country study by UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) that prompted this headline in the Washington Post : “Schools should ban smartphones. Parents should help.” The study recommends a ban on smartphones at school for students of all ages, and says the data are unequivocal, showing that countries that enforce restrictions see improved academic performance and less bullying.

It’s a fraught debate, one that prompts frustration among educators, who say students are less focused than ever as schools struggle to enforce cell phone limitation policies, and rage from some parents, worrying about a possible shooting when they can’t get in touch, who insist they need to be able to reach their children at all times. And, perhaps surprisingly, it prompts a collective yawn from students.

In fact, students openly admit their cell phones distract them and that they focus better in school without them, says Joelle Renstrom , a senior lecturer in rhetoric at Boston University’s College of General Studies. It’s an issue she has studied for years. She even performed an experiment with her students that supports what she long suspected: Cell Phones + Classrooms = Bad Learning Environment.

BU Today spoke with Renstrom about the latest study and research.

with Joelle Renstrom

Bu today: let me get right to the point. do we as a society need to be better about restricting cell phones in classrooms it seems so obvious..

Renstrom: Of course. But it is easier said than done. It’s hard to be consistent. We will always have students with some kind of reason, or a note from someone, that gives them access to technology. And then it becomes hard to explain why some people can have it and some people can’t. But student buy-in to the idea is important.

BU Today: But is getting students to agree more important than getting schools and parents to agree? Is it naive to think that students are supposed to follow the rules that we as parents and teachers set for them?

Renstrom: I have made the case before that addiction to phones is kind of like second-hand smoking. If you’re young and people around you are using it, you are going to want it, too. Every baby is like that. They want to reach for it, it’s flashing, their parents are on it all the time. Students openly acknowledge they are addicted. Their digital lives are there. But they also know there is this lack of balance in their lives. I do think buy-in is important. But do it as an experiment. Did it work? What changes did it make? Did it make you anxious or distracted during those 50 minutes in class? I did that for years. I surveyed students for a number of semesters; how do you feel about putting your phone in a pouch? They made some predictions and said what they thought about how annoying it was. But at the end, they talked about how those predictions [played out], and whether they were better able to focus. It was very, very clear they were better able to focus. Also interestingly, not a single student left during class to get a drink or go to the bathroom. They had been 100 percent doing that just so they could use their phone.

BU Today: Should we be talking about this question, cell phones in classrooms, for all ages, middle school all the way through college? Or does age matter?

Renstrom: It’s never going to be universal. Different families, different schools. And there is, on some level, a safety issue. I do not blame parents for thinking, if there’s someone with a gun in school, I need a way to reach my kids. What if all the phones are in pouches when someone with a gun comes in? It’s crazy that we even have to consider that.

BU Today: What’s one example of something that can be changed easily?

Renstrom: Parents need to stop calling their kids during the day. Stop doing that. What you are doing is setting that kid up so that they are responding to a bot 24-7 when they shouldn’t be. If you’re a kid who gets a text from your parent in class, you are conditioned to respond and to know that [the parent] expects a response. It adds so much anxiety to people’s lives. It all just ends up in this anxiety loop. When kids are in school, leave them alone. Think about what that phone is actually meant for. When you gave them a phone, you said it’s in case of an emergency or if you need to be picked up in a different place. Make those the parameters. If it’s just to confirm, “I’m still picking you up at 3,” then no, don’t do that. Remember when we didn’t have to confirm? There is a time and place for this, for all technology.

BU Today: This latest study, how do you think people will react to it?

Renstrom: This isn’t new. How many studies have to come out to say that cured meat is terrible and is carcinogenic. People are like, “Oh, don’t tell me what to eat. Or when to be on my phone.” This gets real contentious, real fast because telling people what’s good for them is hard.

BU Today: I can understand that—but in this case we’re not telling adults to stop being on their phones. We’re saying help get your kids off their phones in classrooms, for their health and education.

Renstrom: Studies show kids’ brains, and their gray matter, are low when they are on screens. School is prime habit-forming time. You should not sit in class within view of the professor, laughing while they are talking about World War II. There is a social appropriateness that needs to be learned. Another habit that needs to be addressed is the misconception of multitasking. We are under this misconception we all can do it. And we can’t. You might think, I can listen to this lecture while my sister texts me. That is not supported by science or studies. It is literally derailing you. Your brain jumps off to another track and has to get back on. If you think you have not left that first track, you are wrong.

BU Today: So what next steps would you like to see?

Renstrom: I would like to see both schools and families be more assertive about this. But also to work together. If the parents are anti-smartphone policy, it doesn’t matter if the school is pro-policy. If there is a war between parents and schools, I am not sure much will happen. Some kind of intervention and restriction is better than just ripping it away from kids. The UNESCO study found it is actually even worse for university students. We are all coming at this problem from all different ways. Pouches or banned phones. Or nothing.

Explore Related Topics:

- Smartphones

- Share this story

- 14 Comments Add

Associate Vice President, Executive Editor, Editorial Department Twitter Profile

Doug Most is a lifelong journalist and author whose career has spanned newspapers and magazines up and down the East Coast, with stops in Washington, D.C., South Carolina, New Jersey, and Boston. He was named Journalist of the Year while at The Record in Bergen County, N.J., for his coverage of a tragic story about two teens charged with killing their newborn. After a stint at Boston Magazine , he worked for more than a decade at the Boston Globe in various roles, including magazine editor and deputy managing editor/special projects. His 2014 nonfiction book, The Race Underground , tells the story of the birth of subways in America and was made into a PBS/American Experience documentary. He has a BA in political communication from George Washington University. Profile

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.

There are 14 comments on Why Schools Should Ban Cell Phones in the Classroom—and Why Parents Have to Help

i found this very helpful with my research

It was a great research, helped me a lot.

I think that this was helpful, but there is an ongoing question at my school, which is, though phones may be negative to health and knowledge and they’re a distraction what happens if there was a shooting or a fire or a dangourus weather event and you don’t have a phone to tell your parents or guardians at home if you are alright? (Reply answer if have one)

Yeah they would get an amber alert

well, the school has the technology that can help communicate that to the parents, and if that were to happen, I guess that’s why there’s always a cell phone in the classrooms those old-time ones, but I feel it would not be okay in case of a shooting since you have to go silence, and on the moment of fire or weather everything happens so fast in the moment.

In schools all teachers have cell phones. So one way or the other the messages would get out to the parents as needed. If a student gets on the cell phone to inform the parent about the activity, that’s taken place it could cause panic. School staffs are informed as to how to handle such situations.. what I have seen take place in classes are students who are texting each other either in the same room or in another classroom during the school time. Many students spend time on YouTube and not concentrating what’s going on in the classroom.

I think that this was helpful, but there is an ongoing question at my school, which is, though phones may be negative to health and knowledge and they’re a distraction what happens if there is a shooting or a fire or a dangerous weather event and you don’t have a phone to tell your parents or guardians at home if you are alright?

I am writing a paper and this is very helpful thank you.

I am writing a paper and this is very helpful but it is true what if our mom or dad have to contact us we need phones!

this helped me with my school project about whether cell phones should be banned in school. I think yes but the class is saying no. I think it’s because I was raised without a phone so I know how to survive and contact my parents without a phone. but anyway, this helped me with my essay! thank you!

I don’t think phones should be allowed in school, and this is perfect backup! Thank you Doug

great infromation for debate

Thanks, this helped a lot I’m working on an essay and this has been really helpful.by the way, some people may think, but what if i need to call my mom/dad/guardian. but the real thing is, there is a high chance that there will be a telephone near you. or if it’s something that only you want them to know,go ahead and ask your teacher if you can go to the office.

Post a comment. Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Latest from BU Today

Bu’s earth day celebrations, tenth annual giving day raises more than $3.8 million, bu freshman macklin celebrini named a hobey baker award finalist, photos of the month: a look back at march at bu, what’s hot in music this month: new releases, local concerts, the weekender: april 4 to 7, could this be the next snl bu student’s wicked smaht comedy troupe performs this weekend, determined to make the world a better place, giving day 2024: bu celebrates 10 years of giving back, your everything guide to landing an internship, building a powerhouse: how ashley waters put bu softball on the map, sex in the dark: a q&a event with sex experts, tips to watch and photograph the april 8 total solar eclipse safely, for cfa’s head of acting, huntington role required discretion, listening, biden’s biggest challenges to reelection—immigration, gaza, and even the economy, boston university drops five-day isolation requirement for covid, the weekender: march 28 to 31, bridge collapse creates conversation in bu structural mechanics class, terriers in charge: favor wariboko (cas’24), the bold world of marcus wachira.

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Cell phone use policies in the college classroom: Do they work?

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Guest Access

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Shannise B. Jones , Mara S. Aruguete , Rachel Gretlein; Cell phone use policies in the college classroom: Do they work?. Transactions of the Missouri Academy of Science 1 January 2020; 48 (2020): 5–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.30956/MAS-31R1

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Our study examined the efficacy of lenient and restrictive cell phone policies. We expected that a lenient policy would be associated with lower quiz scores, greater anxiety, and lower GPA. Additionally, we expected students to self-report using their phones mostly for non-academic purposes. We gave one introductory psychology section a restrictive cell phone use policy while another section was given a lenient policy. We observed how often students used their phones during class in both conditions. At the end of the class period, students took a short quiz over the lecture material. Afterward, they were given a survey that measured demographics, attitudes about cell phone use in class, academic motivation, cell phone use domains, and anxiety. In the restrictive policy condition, students used their cell phones in class at a similar rate as in the lenient policy condition, suggesting that the restrictive cell phone policy was ineffective. Students operated their phones an average of about seven times during the 50-minute class period, mostly for non-academic purposes. Our results contribute to a body of literature showing that electronic devices distract students and decrease the efficacy of the learning environment.

Examining the relationship between cell phone use and the learning environment is critical in understanding contemporary college students. Most students report bringing their cell phones to class every day ( Froese, Carpenter, Inman, Schooley, Barnes, Brecht, & Chacon, 2012 ), and over 80% report using their phones at least one time in each class period ( Berry & Westfall, 2015 ). Smartphones give students endless academic resources at their fingertips. While cell phones allow students to quickly access information, they also introduce potentially negative effects on teaching and learning ( Burns & Lohenry, 2010 ). Classroom cell phone policies might help to mitigate negative effects of cell phones on student achievement ( Burns and Lohenry, 2010 ). Our study examines the efficacy of restrictive and lenient policies.

Many studies show that in-class cell phone use has predominantly harmful effects on student learning ( Bjornsen & Archer, 2015 ; Burns & Lohenry, 2010 ; Duncan, Hoekstra, & Wilcox, 2012 ; Froese et al., 2012 ; Junco & Cotten, 2012 ; Lepp, Barkley, & Karpinski, 2014 ). Using interviews, observations, and surveys, Duncan et al. (2012) found that the use of cell phones in class corresponded to a decline of nearly half of a letter grade in the course. Similarly, Froese et al. (2012) found that texting in class was associated with a 27% drop in student grades. A recent meta-analysis on a range of student outcome variables showed a negative relationship between cell phone use and student achievement ( Kates, Wu, & Coryn, 2018 ). Classroom cell phone use and its associated negative outcomes may be particularly likely in some learning environments (e.g., high enrollment classes with little active student participation; Berry & Westfall, 2015 ).

Some authors have argued that classroom cell phone use can be beneficial if it is integrated into course activities ( Wood, Mirza, & Shaw, 2018 ). For example, phone-based personal response systems (e.g., Kahoot, TopHat) have been shown to have positive effects on learning ( Ma, Steger, Doolittle, & Stewart, 2018 ). However, college students report spending the majority of time using cell phones for non-academic purposes ( Junco & Cotten, 2012 ), and “off-task” uses are common during classroom activities that integrate cell phones ( Wood, et al., 2018 ). Moreover, the more time students spend using technology while attempting to complete schoolwork, the lower their GPAs ( Junco & Cotten, 2012 ). Thus, while cell phones in class may sometimes enhance learning, “off task” use in the classroom may diminish these beneficial effects.

Evidence indicates that students are aware that cell phone use is dangerous to their grades, but yet persist in the activity compulsively. Burns and Lohenry (2010) reported that 53% of students admitted to texting in class. However, 85% of students considered cell phones to be distracting during class. Moreover, students are apparently aware that in-class cell phone use can be detrimental to their grades. Elder (2013) found that students reported expecting a decline in grades as a result of cell phone use. Nonetheless, many students persisted in using their phones in class, suggesting that cell phone use might be a compulsive activity. Students exhibiting less self-regulation are more likely to text in class, and have a hard time sustaining attention in class ( Wei, Wang, & Klausner, 2012 ). The compulsion to use cell phones has the potential to be a detriment to students' personal well being ( Roberts, Yaya, & Manolis, 2014 ).

If in-class cell-phone use constitutes a compulsion, might it be associated with anxiety? Indeed, survey research shows that students who use their cell phones often are more likely to have lower GPAs and report more anxiety ( Lepp et al., 2014 ). Social anxiety and poor self-esteem are also related to excessive cell phone use ( You, Zhang, Zhang, Xu, & Chen, 2019 ). In-class texting is associated with impulsivity and an inability to delay gratification ( Hayashi & Blessington, 2018 ). These results suggest that in-class cell phone use might be motivated by anxiety.

There is some evidence that cell phone use policies can mitigate the negative effects of cell phones in the classroom. Burns and Lohenry (2010) proposed five ways professors could combat the distraction of cell phone use in class. These proposed solutions included creating, implementing, and clearly communicating cell phone policies, as well as role modeling, reinforcing, and clearly communicating cell phone etiquette. Classroom policies on cell phone use vary widely and some policies are likely to be more effective than others. McDonald (2013) tested the efficacy of a restrictive cell phone use policy (cell phones banned in class) compared to no cell phone policy. On average, students in the no-policy courses suffered a decline in grades. However, Lancaster (2018) found no differences in student learning in classes featuring permissive and restrictive cell phone policies. Therefore, it is unclear whether and how cell phone policies affect student learning.

Berry and Westfall (2015) investigated students' perspectives of classroom cell phone policies. Students reported that the most punitive policies were also the most effective and the least punitive policies were the least effective. These results suggest that strict policies are needed to dissuade students from in-class cell phone use. However, cell phone policies might affect student evaluations of the class. Jackson (2013) reported that students feels annoyed when instructors ban the use of cell phones during class. However, Lancaster (2018) showed that students reported more positive evaluations of an instructor when the instructor used a restrictive cell phone policy compared to a permissive policy. Therefore, it is not entirely clear whether restrictive policies result in positive or negative student affect.

Our study examines the effects of a one-day intervention that varied cell phone policies in two introductory psychology course sections. One course section was given a lenient policy, while the other section was given a restrictive policy. We developed four hypotheses: First, we hypothesized that the class with the lenient policy would exhibit more cell phone use. Second, we expected that in-class cell phone use would predict lower quiz scores. Third, we expected participants with more anxiety to report more in-class cell phone use and lower GPAs. Finally, we expected students to self-report using their phones mostly for non-academic purposes.

Participants

We recruited a convenience sample of 73 students ( M age = 20.35, SD = 4.35; 35 female, 37 male) enrolled in two sections of an introductory psychology course at a public Midwestern Historically Black University (40 students were officially enrolled in each section). Our sample consisted of 47 African American students and 18 White students (8 students of other ethnicities). Students were observed and surveyed during class time. The Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the study prior to data collection.

The two sections of the introductory course were randomly assigned to one of two groups: a restrictive cell phone policy or a lenient cell phone policy. In the restricted cell phone group, participants were explicitly told that cell phone use would be prohibited during the 50-minute lecture. Furthermore, instances of cell phone use detected by the professor would result in a deduction of two attendance points. In the restrictive condition, the professor made an attempt to record cell phone use while lecturing. This multitasking likely resulted in unrecorded instances of student cell phone use. In the lenient phone policy group, participants were told that phone use would not result in any deduction of points.

Both groups were presented the same lecture, in the same room (featuring theater-style seating), by the same professor, one hour apart. Prior to the assignment of conditions, there was no stated cell phone policy in either section. The manipulation took place approximately one month into the semester, on the same day for both groups. The manipulation of the lenient policy group preceded the restrictive group on that day. While students in the lenient policy group might have informed those in the restrictive group about the manipulation, that scenario is unlikely since the manipulation took place over two consecutive class hours with only a 10-minute transition between conditions.

Two observers attended the classes to record actual cell phone use during the 50-minute lectures. Students were told that the researchers were student teachers observing the techniques of the professor. Researchers sat in the back of the room and recorded all instances of phone use using a checklist.

At the end of the class period, students took a 10-question multiple-choice quiz over the lecture material and completed a survey. The survey measured demographics (e.g., gender, ethnicity), attitudes about cell phone use in class (e.g., “Students should be allowed to use cell phones in class;” 2 items; α = 0.74), academic motivation (“I outline specific goals for my study time;” 8 items; α = .83), tasks completed with cell phone during in-class phone use (5 tasks, see Table 1 ), and anxiety (e.g., “I worry too much about different things;” Spitzer, Williams, & Kroenke, 1999 ; 5 items; α =0.81). Apart from demographics, each question was followed by a 5-point Likert scale.

Self-Reported Typical Tasks Completed With Cell Phone

We expected the lenient policy group to use their phones significantly more than the restrictive policy group. Our observations indicated that both sections used their cell phones an approximately equal amount regardless of whether the cell phone policy was lenient (45 instances of in-class cell phone use) or restrictive (43 instances), Chi Square = 0.04, p = 0.83.

We predicted that the class with the lenient policy would have lower quiz scores. The quiz scores between the two groups did not differ significantly. The restrictive-policy group ( M = 5.44, SD = 2.11) had only slightly lower scores than the lenient-policy group ( M = 5.83, SD = 1.99), t (71) =0.81, p = 0.42. Both groups also reported similar academic motivation, t (70) = -0.67, p = 0.50, in-class cell phone use, t (64) = 1.65, p = 0.10, and anxiety, t (70) = 1.40, p = 0.17.

We anticipated that participants reporting more anxiety would report more in-class phone use. Contrary to what we expected, anxiety was not a predictor of in-class cell phone use, r (65) = -.15, p = 0.23. Predictably, academic motivation was significantly correlated with higher quiz scores, r (72) = -0.28, p = 0.02. Of note, students self-reported checking their phones an average of 6.92 times during a single 50-minute class period.

Students reported using their phones during class time for a variety of activities. While some students reported using their phones in class for academic purposes, it was more common for students to use their phones for entertainment and social media purposes (see Table 1 ).

Our results suggest that punitive in-class cell phone policies like ours are likely to be ineffective. Cell phone use was high in our samples, and was not affected by the introduction of a lenient or restrictive policy. In the restrictive policy condition, the professor was unable to monitor cell phone use effectively while teaching, which may have rendered the policy ineffective. One of the most influential factors affecting cell phone use is class size ( Tindell & Bohlander, 2012 ). With over 25 students, noticing individual instances of cell phone use might be impossible or overly distracting for a professor who is concentrating on the lesson. Being unaware of the extent of cell phone use, the faculty member might believe that his/her policies are effective. Berry and Westfall (2015) found that faculty self reported that almost all types of cell phone policies were effective, whereas students reported perceiving most cell phone policies as ineffective.

Perhaps stricter phone policies, such as making student phones inaccessible during class time, would be more likely to deter cell phone use ( McDonald, 2013 ). However, there is a risk that stricter phone policies could be detrimental to the learning environment by making students focus on hiding their phone use, causing them to further dissociate from the class experience. Another potential drawback is that students reportedly dislike strict policies ( Jackson, 2013 ). However, with cell phone use habits well established by the time students enter college, strong policies may be necessary to alter student behavior ( McDonald, 2013 ).

Students report having trouble not using their phones during class ( Roberts et al., 2014 ; Sunthilia, Ahmad, & Singh, 2016). Indeed, our data show consistently high cell phone use in both groups. Students using cell phones in class realize that the behavior has a negative impact on their grades, yet the activity seems difficult to control ( Roberts et al., 2014 ; Sunthilia et al., 2016). Compulsive cell phone use suggests an association with anxiety, in which a student might experience anxiety relief from engaging in phone use. However, our data did not show that anxiety was associated with cell phone use. Rather, the positive reinforcements (e.g., social connectivity) inherent in phone use might increase the behavior ( Puente & Balmori, 2007 ). Moreover, students may be unable to focus on the long-term rewards of paying attention in class (e.g., gaining knowledge, better test scores, and an eventual degree) and instead give in to the immediate temptation to use their phones. Perhaps delaying the gratification of phone use can be trained ( Murray, Theakston, & Wells, 2016 ). Interventions might focus on increasing self-regulation of cell phone use. Research suggests that individuals who have better delay of gratification skills also succeed better academically and socially throughout life ( Yang & Wang, 2007 ).

A potential solution to the problem of distracting cell phones could be for professors to use cell phones in the classroom in structured ways that promote learning. Finding educationally relevant ways for students to use their phones in class may alleviate the compulsory need to use phones for non-academic purposes. For example, phone-based personal response systems can be effectively used to quiz students on course material or to increase class participation ( Ma et al., 2018 ). Rogers (2009) suggests that for in-class cell phone use to be beneficial to students, guidelines and norms must be taught in middle and high school. Clear boundaries and enforceable consequences are imperative to the success of such an initiative ( Weinstock, 2010 ). Even so, problems may occur when students access non course-related sites during class time ( Madden, 2012 ). Indeed, our data suggests that students tend toward non-academic cell phone use in the classroom.

If punitive cell phone policies like ours are no better than the absence of a cell phone policy, the question remains whether there are any types of cell-phone policies that are effective. One possibility is to create a policy based on positive reinforcement, rather than punishment. A quasi-experiment by Katz and Lambert (2016) implemented a reward system for students who refrained from phone use during class. Students who handed in their phones at the beginning of class received one extra credit point toward their final grades. Katz and Lambert (2016) found that students handing in their phones showed better test scores, attendance, and semester GPA. Further research should investigate the topic of reinforcement-based cell phone policies.

Our study had several limitations. One major limitation was the short time frame of the policy manipulation. Students may need more than one class period to adapt to a professor's policy before making substantial behavior changes. Research should examine how long policies need to be in place before they show behavioral changes. A related limitation was the fact that the new policy was introduced midway though the semester. There may have been carry-over effects of the prior policy that affected our results. We do not have any means of knowing how seating arrangement or class size might have affected our results. Our observations of cell phone use only recorded number of instances of use, not duration of use. Checking the time on a cell phone for 1 second might be far less distracting than scrolling though Instagram for 10 minutes. Finally, our mostly African American sample may be different from other student samples insofar as cultural background might influence cell phone use patterns. For example, African Americans and Latinos are less likely to access the Internet on smart phones than other groups ( Fairlie, 2017 ). Therefore, it may be hard to generalize our findings to other college student samples.

Our study suggests that punitive methods aimed at banning cell phone use in class may be somewhat ineffective. Students are using their phones predominantly for entertainment and social media purposes, which may distract from class material and could result in lower grades. Pedagogical methods that utilize phones in class for educational purposes pose a number of logistical difficulties, including the persistent need to control phone use for “off-task” activities. Further research should continue to investigate how the beneficial aspects of cell phones might be maximized while minimizing distraction from teaching and learning. Other topics for future research include investigation of how class size, teaching style, and seating arrangement affect cell phone use. Finally, researchers should explore the question of whether policies should be tailored to various cultural, ethnic, or age groups to maximize their effectiveness.

Recipient(s) will receive an email with a link to 'Cell phone use policies in the college classroom: Do they work?' and will not need an account to access the content.

Subject: Cell phone use policies in the college classroom: Do they work?

(Optional message may have a maximum of 1000 characters.)

Citing articles via

Get email alerts.

- For Authors

- ISSN 0544-540X

- Privacy Policy

- Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Banning mobile phones in schools: evidence from regional-level policies in Spain

Applied Economic Analysis

ISSN : 2632-7627

Article publication date: 25 January 2022

Issue publication date: 14 October 2022

The autonomous governments of two regions in Spain established mobile bans in schools as of the year 2015. Exploiting the across-region variation introduced by such a quasi-natural experiment, this study aims to perform a comparative-case analysis to investigate the impact of this non-spending-based policy on regional Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores in maths and sciences and bullying incidence.

Design/methodology/approach

The authors apply the synthetic control method and diff-in-diff estimation to compare the treated regions with the rest of regions in Spain before and after the intervention.

The results show noticeable reductions of bullying incidence among teenagers in the two treated regions. The authors also find positive and significant effects of this policy on the PISA scores of the Galicia region that are equivalent to 0.6–0.8 years of learning in maths and around 0.72 to near one year of learning in sciences.

Originality/value

To the best of the author’s knowledge, this is the first empirical study analysing the impact of mobile phone bans in schools on bullying cases, exploiting variation across regions (or other units), years and age intervals. Besides, the scarce formal evidence that exists on the consequences of the mobile phones use in students’ academic achievement comes from a micro perspective, while the paper serves as one more piece of evidence from a macro perspective.

- School bullying

- Comparative-case studies

- Maths and sciences skills

- Regional-level policies

Beneito, P. and Vicente-Chirivella, Ó. (2022), "Banning mobile phones in schools: evidence from regional-level policies in Spain", Applied Economic Analysis , Vol. 30 No. 90, pp. 153-175. https://doi.org/10.1108/AEA-05-2021-0112

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2022, Pilar Beneito and Óscar Vicente-Chirivella.

Published in Applied Economic Analysis . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence maybe seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

The question of whether or not to ban mobile phones’ usage in schools is on the current agendas of education policy mandates and has generated recent debates in many countries [ 1 ]. Beyond particular policies at the individual school level, governments in some countries or some states/regions banned mobile phones in schools in recent years. For instance, the Israeli Ministry of Education decided to ban mobile phones during the school day in 2016. In France, the policy came into effect during the beginning of the 2018–2019 school year and impacted students over 15. In 2019, four states in Australia banned smartphones for students up to 18 years. Instead, in 2015 the Mayor of New York removed a 10-year ban of phones in schools, claiming that abolition could decrease inequality ( Allen, 2015 ). Governments pursue two main goals with this type of policy intervention: improving academic performance and reducing bullying, which are precisely the impacts that we address in this paper.

An effective control of the use of new mobile technologies made by students at schools can constitute a new policy tool to complement resource-based interventions by governments. This might become specially interesting if, as some authors have pointed out, the room for resource inputs to affect human capital formation can be of limited scope in some settings. In this line, Woessmann (2016) provides evidence that students in a wide set of countries overperform students in the USA while spending considerably less on schools per student ( OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2013 ). This author concludes that a wide range of additional factors, including institutional features of school systems, may entail major implications for the effectiveness of education investments.

In this paper, we provide regional-level evidence of the impact of a non-spending-based policy intervention directly aimed at enhancing academic outcomes and, simultaneously, students’ social behavior. In particular, we investigate the impact of banning mobile phones in schools on students’ academic achievement and school bullying incidence. To this end, we use as comparative case studies two regions in Spain (Galicia and Castilla La Mancha, CLM henceforth) whose regional governments passed laws to ban mobile phones in primary and secondary educational centers towards the end of the year 2014 (CLM) and beginning of the year 2015 (Galicia). In the rest of Spanish regions other than Galicia and CLM, the use of mobile phones by students in schools is not regulated [ 2 ].

The mentioned interventions in Galicia and CLM constitute a quasi-natural experiment that allows us to take the case of Spain and their regions as an excellent lab for the analysis of this highly debated policy. One advantage of using regional-level data within a country is that it permits us to examine differences among units that are comparable in some fundamental institutional and cultural traits. That is, it avoids the huge unobserved country heterogeneity affecting cross-country analysis ( Di Liberto, 2008 ; and Gennaioli et al. , 2013 ). Galicia and, particularly so, CLM are regions with wealth levels below the Spanish average (over the analyzed period, Galicia is the 9th and CLM is the 14th out of the 17 Spanish regions in the ranking of real income per capita). Hence, the analysis of a policy intervention that could impact educational development, while not based on large investments of economic resources, entails great interest in the case of disadvantaged regions.

To conduct the analysis, we construct a region-level panel data for our outcome variables of interest as well as for several regional-year control variables using official data sources for the 17-Spanish regions before and after the mobile phone bans (with the exceptions that we will comment below). We compare the regions where the policy was implemented (the treated regions, henceforth) with the rest of regions in Spain before and after the intervention took place.

For the analysis of academic outcomes, we use the scores in maths and sciences obtained by 15-year-old Spanish students in the five The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) installments conducted from 2006 to 2018 (every three years). The PISA scores [international testing entered by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 2000] have the advantage of their international comparability and are aimed at evaluating competencies and skills rather than locally designed academic goals. In addition, the focus on middle-school students is of special interest in the case of Spain, given the importance of secondary education in the Spanish labor market ( López-Bazo and Moreno, 2012 ).

As participation in the PISA installments is not mandatory, the CLM region did not participate neither in 2006 nor in 2012, which poses us problems for the analysis of the pre-intervention trends in the academic achievement of students in this region. Fortunately, the data for the Galicia region is complete. Taking advantage of this, we apply both the synthetic control method (SCM, henceforth, Abadie and Gardeazábal, 2003 ; Abadie et al. , 2010 ) and differences-in-differences (DID) regression analysis (DID, henceforth) to evaluate the impact of the mobile phones ban on students’ PISA scores in this region. In the case of the CLM region, we will present below some estimates of the effect of interest using DID regressions, though we take with special caution these results due to the mentioned data limitations.

For the analysis of bullying, we apply DID regression to both Galicia and CLM. The outcome variables are, in this case, officially reported cases for every 10,000 school students in three age intervals (covering from 6 to 17 years old), spanning over the period 2012–2017. This information, by region and year, was requested to the Spanish police forces and made public by the Spanish Ministry of Education in 2018, following a specific demand of information in this regard made by a member of the parliament. Thus, the region-year-age level data on bullying used in this paper is quite unique. To our knowledge, this is the first empirical study exploiting variation across regions (or other units), years and age intervals on bullying cases.

There exists scarce formal evidence on the consequences of the mobile phone use in students’ academic achievement. This is especially important on primary and secondary education since it is at this age when children initiate the use of these devices, and also where the existing evidence is particularly scarce [ 3 ]. The use of mobile devices is not necessarily detrimental for education when correctly designed. For example, the use of certain Apps could make children more involved in their learning process and increase the enjoyment from studying. In addition, the immediate access to an infinite source of information can complement instruction received at schools and improve the learning process of students ( Milrad, 2003 ). Furthermore, students can rapidly share information not only with other students but also with teachers, which could lead to a more efficient studying and collaboration ( Chen and Ji, 2015 ; Lepp et al. , 2015 ).

Positive effects on academic achievement can also come from potential complementarities between the use of mobile phones and the development of other technological competencies on the part of students, provided that the latter enhances academic outcomes. In this regard, our paper is also related to the literature on the impact of technology on students’ outcomes. Results from this literature, however, are far from conclusive [ 4 ]. Some results seem to indicate that what actually matters is not the technology on its own but rather the structured or unstructured use of a particular technology. For instance, Barrow et al. (2009) find that students randomly assigned to computer-aided instruction using an algebra program largely improve on algebra test scores compared to the students receiving traditional instruction. Also, Muralidharan et al. (2019) show that well-designed, technology-aided instruction programs sharply improve test scores in middle-school grades [ 5 ]. Finally, Fryer (2013) set an experiment where a treated group of students were provided with free mobile phones where they received daily information about human capital and future outcomes, while the control group did not receive this information. Results show that although students in the treated group did not improve attendance, behavioral incidents or test scores, they reported being more focused and working harder in school. Cho et al. (2018) offer a meta-analysis looking at the effect of mobile devices on student achievement in language learning in primary, secondary and post-secondary education. They find a positive effect of using mobile devices on language acquisition and language-learning achievement and, thus, conclude that the use of mobile devices could facilitate language learning.

However, even if mobile phones are used to structured activities, allowing them in schools opens the door to be used for recreational purposes as well, thus generating distraction. In fact, according to research in computer science and educational studies, the detrimental effects of mobile phones in schools are explained because multi-tasking or task-switching decrease learning ( Jacobsen and Forste, 2011 ; Junco and Cotten , 2011, 2012 ; Rosen et al. , 2013 ; Wood et al. , 2012 ). For example, notifications on the smartphone are a constant distraction limiting students’ attention during class and/or study time ( Junco and Cotten, 2012 ). Besides, the desire to continuously interact with the rest of the world may lead to a level of concentration that is lower than needed to achieve a good study performance ( Chen and Yan, 2016 ) [ 6 ]. Finally, unmotivated students have a great temptation at their fingertips to switch off from the lesson and play games, surfing the internet or use social networks ( Hawi and Samaha, 2016 ). Some experimental papers present additional evidence pointing in this direction ( Wood et al. , 2012 ; Kuznekoff and Titsworth, 2013 ; Levine et al. , 2013 ; Amez and Baert, 2020 , for a survey of papers published in this field).

Recent direct evidence on the causal effects of banning mobile phones policies on academic outcomes are provided by Beland and Murphy (2016) , Kessel et al. (2020) and Abrahamsson (2020) . Beland and Murphy (2016) investigate the impact of banning mobile phone use in schools on student academic results using a sample of 91 schools in four English cities. In particular, they analyze the gains in test scores across and within schools before and after mobile phones bans were introduced, and find positive effects of banning the use of mobile phones on such academic results. Kessel et al. (2020) replicate the same study with data for Sweden but, contrary to Beland and Murphy (2016) , do not find any significant effect of the ban on students’ academic performance. Abrahamsson (2020) studies the effect of banning smartphones in the classroom on students’ educational outcomes in Norwegian middle schools, and shows that the banning policies significantly increased girls’ grade point average and increased their likelihood of attending an academic high school track. Interestingly, the magnitude of her estimates is larger among low-ability students and students from low socioeconomic backgrounds.

Research on the relationship between the use of mobile phones in schools and bullying is even scarcer. A possible explanation for this lack of studies is the difficulty in obtaining reliable data on bullying cases. The link between mobile phones in schools and bullying is very intuitive: given that cyberbullying already represents 20% of bullying cases ( Cook, 2020 ) and that smartphones are one of the main conduits for cyberbullying among children ( Adams, 2019 ), the removal of the instrument should be expected to influence the number of bullying cases. In spite of the scarcity of research on this topic, the analysis of the possible actions that may control bullying is of primary importance, given the severe and long-term consequences for those suffering it as a child or teenager in the form of psychological and emotional health, education and future earnings ( Drydakis, 2014 ). To the best of the authors knowledge, the paper by Abrahamsson (2020) is the unique reference in the literature that carries out a causal analysis of the link between banning mobile phones at schools and bullying. This author finds that banning mobiles phones have the potential to reduce school bullying among middle-school students. Further, and interestingly enough, she finds that the policy is effective only when it is implemented as a clear prohibition to bring the device (mobile phone) into school.

As mentioned before, other studies have already looked at the effect of banning mobile phones in schools on student achievements using micro data. Unfortunately, we do not have data at such a disaggregated level. However, with the data we have and the techniques we use in our analysis, we can still provide suggestive evidence on whether a regional-level policy can have effects on our variables of interest. Therefore, one of the contributions of our paper is offering a new perspective by looking at differences between regions rather than differences across schools and students. By using the PISA assessments, which are homogenous across regions, we avoid all the possible concerns about different exams in different schools and the self-selection of students in certain schools. One more novelty of our study is that we are able to check the bullying effects in different age groups: under-12, 12–14 and from 15–17 years old. Given that among children under 12 years old the use of mobile phones is not extended yet in Spain, we do not expect significant results for the under-12 group. Thus, results for this age group may serve as a placebo check in our analysis below [ 7 ].

Thus, our paper contributes by highlighting the potential effects of a non-spending-based policy on the educational attainment of middle-school students. In addition, our analysis also addresses the potential effects of these policies in enhancing the school social environment, an indirect though potentially relevant factor affecting educational outcomes. The policy analyzed in this paper is a timely issue of primary relevance looking ahead on a future where technology will dominate the workplace, and everything will be connected and data-driven.

To anticipate our results, we find that, after less than three years since the mobile phones ban was in force (from 2015 to 2017), students’ PISA scores in Galicia improved by around 10 points in maths and 12 points in sciences as compared to a synthetic Galicia that had followed exactly the same trend in these scores before the intervention. Following Woessmann (2016) , these estimated effects are equivalent to 0.6–0.8 years of learning in maths and around 0.72 to near one year of learning in sciences. Jointly with this, bullying incidence fell by around 9.5% to 18% over its pre-intervention levels among teenagers in the treated regions.

It is worth mentioning that the prohibition policy analyzed here was not a categorical prohibition since it allowed devices to be used inside the schools as a learning tool for educational purposes. Could it be the case that Galicia and CLM decided to use the devices in this direction to a larger extent since the year 2015? According to the INE [ 8 ], this does not seem to have been the case: the percentage of secondary schools that allowed students to use mobile devices with educational purposes during 2016/2017 (first year with available information) were around 33% and 36% for Galicia and CLM, respectively, while the national average was 34%. Unfortunately, we do not have information on whether these schools ended up using mobile phones with educational purposes or not or to what extent.

Even if the policy was not a categorical prohibition, it certainly provides the legal coverage for centers and instructors to effectively limit students’ misbehaviors in educational centers. From this perspective, it seems sensible to assume that the percentage of educational centers/teachers controlling the use of mobile phones have been clearly higher in the regions with and after the policy. In any case, our estimates have to be framed within the limitation of the available information, and taken not as a response to the prohibition of mobile phones per se but, instead, to the enforcement of using mobile phones for learning purposes only.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a description of the materials and methods used in this paper. Section 3 presents the results, and finally, Section 4 concludes and discusses our main results.

2. Data and methods

2.1 region-year panel data.

Spain is administratively organized in 17 regions (NUTS-2 regions, in the Eurostat’s classification, referred to as “Comunidades Autónomas” in Spain). The regional governments are autonomous, among other aspects, to decide upon the regulation and administration of education in all its extension, levels and grades [ 9 ]. On this base, two Spanish Regional Governments (CLM and Galicia) passed laws to ban in all the educational centers of primary and secondary stages the use of mobile phones by students as of 2015 [ 10 ]. In the rest of the regions, the use of mobile phones is unregulated, in most of the cases allowing each school to decide upon the use of mobile phones [ 11 ]. To conduct the analysis, we create a region-level panel using official sources of data for all the 17-Spanish regions before and after the mobile phones-ban, with the exceptions that we comment below. We set the year 2015 as the first year where the intervention could have had an effect on our outcome variables [ 12 ].

For the analysis of academic outcomes, we use the scores obtained by Spanish school students in the PISA installments from 2006 to 2018 [ 13 ]. We use in total five PISA assessments, corresponding to years 2006, 2009, 2012, 2015 and 2018. We attribute the scoring of every PISA assessment to the academic achievement of students developed up to the previous year. For instance, the results of PISA-2018 are considered to measure the academic competencies acquired by students up to the year 2017 (included). In accordance with this, we lag the PISA scores of a given call one year. After this, we construct a yearly time series of PISA scores interpolating the scores from one PISA wave to the next, under the assumption that the improvement or the decline in academic competencies evaluated by PISA occurs gradually between each pair of consecutive assessments [ 14 ]. We finally use in the analysis the series of constructed scores spanning 2006–2017. Unfortunately, the CLM region did not participate in two out of the five PISA installments (2006 and 2012), so that the series of academic results constructed for this region present limitations when it comes to track their temporal evolution. Thus, we will take with special caution the analysis of academic results in the case of the CLM region [ 15 ].

For the analysis of bullying, we use the information provided by the Spanish Ministry of Education in 2018 about officially reported cases of school bullying from 2012 to 2017. This data was requested in 2018 by the Spanish Ministry of Education to the Spanish national and local police forces to respond a specific query about this social problem made in the parliament [ 16 ]. The regions of Cataluña and País Vasco did not report this information, and, for this reason, these two regions are not included in our analysis of bullying. The cases were reported separately for four age intervals, namely, school students 6–8, 9–11, 12–14 and 15–17 years-old. We define three age groups for our analysis below: on the one hand, primary schools students (under-12 years old), and, on the other hand, secondary school students, distinguishing in this case the two age groups mentioned. For each of these age intervals, we construct the number of cases for every 10,000 school students of that age [ 17 ].

Finally, we construct three additional covariates, with across region and yearly variation, to be used in the SCM and DID estimation. The first variable is the percentage of children over 10 owning a mobile phone [ 18 ]. This variable aims at capturing the extent to which the use of mobile phones, in or out of schools, is generalized among the children of a region and year. Second, we construct series of public real spending (excluding the financial component [ 19 ]) on education in the primary and secondary stages of education per school-student [ 20 ]. This variable tries to capture changes in academic results or bullying that might respond to differences in the regional level of investments in education. Finally, we also construct series of households’ per capita real disposable income for each region-year [ 21 ]. Nominal variables are deflated using CPI indexes at the region-year level.

Figure 1 and Table 1 show the relative standing of the two treated regions, Galicia and CLM, in the Spanish economy in terms of households’ real income per capita, public spending per student on education by region and percentages of children and adolescents who use mobile phones. The period represented in the maps spans 2012–2017. In Figure 1 , the regions have been classified into four quartiles of the distribution of the variable in the heading of each map. Sorting income in decreasing order, the region of CLM lies within the fourth quartile, that is, among the poorest Spanish regions, while Galicia lies within the third quartile in this ranking. Further, as can be seen in Table 1 , income levels have remained quite stable both in the treated and in the untreated regions, and also over the six years period around the implementation of the policy (2012–2017).

In terms of educational public spending, CLM also lies within the last quartile, while Galicia seems to have made a considerable effort during this period in terms of educational spending on primary and secondary education, given that the region is in the first quartile in terms of this type of spending per student. It is unlikely that the income levels of Galicia unless they appreciably start increasing, could sustain in time such levels of educational public spending. Table 1 shows that these levels of Galician public spending on primary and secondary education have increased over the period as much as in the rest of regions in Spain. In any case, to reassure that these differences do not confound our results of interest, we partial out the effect of public educational spending in our estimations below.

Finally, and as regard the use of mobile phones in the regions, the main conclusion we draw is that contrary to what could be expected, income not always correlates positively with mobile phones’ usage. For instance, the region of Extremadura (on the South-West limiting with Portugal) is among the poorest regions in Spain while also among the regions with the most intense usage of mobile phones. The treated regions, Galicia and CLM, lie within the second quartile in this classification. Table 1 further shows that these percentages have been increasing in time and, apparently, at comparable rates in all the Spanish regions.

Next, Figures 2 and 3 display the sample distribution across regions of our two outcomes of interest, namely, PISA scores and bullying incidence, before and after the mobile phones ban. The PISA scale is standardized to have a mean of 500 and a standard deviation, SD, of 100 among all students in OECD countries (this standardization was done in 2003 in maths and in 2006 in sciences). Figure 2 shows that, as compared to previous PISA installments (from 2006 to 2015), the scores obtained by Spanish students in PISA-2018 remained quite stable on average in maths, while in science the average Spanish score diminished by around five points (in our sample, average scores changed from 488.6 to 487.2 in maths and from 494.7 to 489.8 in sciences, before and after the year 2015, respectively). Galicia and CLM are among the regions that improved their position in the Spanish regional ranking with respect to their scores in previous PISA installments.

Figure 3 displays, on the left, the statistics for primary school students under-12 years old and, on the right, those corresponding to children and teenagers who are mobile phones users (12–17 years old). A first observation is that, as expected, reported cases of bullying are much less frequent among the smaller children. In our data, average bullying incidence is 10 times smaller among under-12 children than among 12–17 years old teenagers. Second, we observe in both cases that the officially reported cases of bullying remained quite stable over the period of analysis; if anything, they slightly increased in the under-12 group (averages of 0.38 before 2015 and 0.48 after 2015 for the under-12 group; averages of 3.90 and 3.93 for the older groups; vertical lines in the graphs indicate the sample averages). The right-hand side panel also shows that both Galicia and CLM overpassed by more the average line before 2015 than after that year.

At this descriptive level, however, we cannot discern to what extent the observed changes can be attributed to the mobile phones ban. Differences in (out of school) mobile phone use among children across regions and over time, in income levels or in educational expenditures, for instance, are not controlled in the figures. In the next section, we describe the empirical strategy that we follow to identify the impact of the mobile phones ban.

2.2 Synthetic control method

For the analysis of academic outcomes, we focus specially in the case of Galicia, for which we count on a complete time series of observations (PISA scores in maths and sciences from 2006 to 2017). Our identification strategy relies primarily on the application of the SCM ( Abadie and Gardeazábal, 2003 ; Abadie et al. , 2010 ). The SCM is a statistical technique that has been specially designed to estimate the effects of events or policy interventions that take place at the aggregate level and affect to a small number of large units, such as cities, regions or countries. Thus, it constitutes one of the causal-identifying methods best suited to be applied to our sample data of regions [ 22 ].

The idea behind the SCM strategy is that the effect of an intervention can be measured through a comparison between the evolution of the outcome variable of interest in the unit affected by the policy intervention and a group of units similar to the treated unit that have not been treated. The main requirement to apply this methodology is that the evolution of the outcome variable for treated and untreated units can be properly tracked during the pre-intervention period. Two of the advantages of this methodology are, first, that it only requires data on an aggregate level ( Abadie et al. , 2010 ) and, second, that it solves the arbitrariness in the choice of the control units typically affecting comparative-case studies. Instead, the SCM conducts a formalized data-driven procedure that constructs a weighted combination of a small number of unaffected units, taken from the set of potential controls or donor pool, as the most appropriate unit of comparison [ 23 ].

In the SCM, the counterfactual outcome Y i t N is estimated as the outcome corresponding to that synthetic unit. More formally, considering ( J + 1) regions, with ( J = 1) being the treated one, the synthetic control is constructed from a ( J × 1) vector of weights, W = ( w 2 , […], w J +1 )’ that allows us to define the estimators for Y i t N and for the effect on the treated unit τ it as follows: (1) Y j t N = ∑ j = 2 J + 1 ω j t Y j t (2) τ 1 t ^ = Y j t N ^ − ∑ j = 2 J + 1 ω j t Y j t where the weights are restricted to be non-negative and to sum to one.

To apply the SCM, we need a set of k potential predictors of the pre-intervention outcome trends. As such predictors, we use past values of the own outcome of interest plus the covariates defined above (percentage of children using mobile phones, public spending on education and disposable real income per capita). The method uses a weighting-matrix, V , that contains the relative importance of each of the k predictors in constructing the synthetic control. The main challenge of the method is how to find the optimal weighting matrices W and V . We follow Abadie et al. (2010) , who propose choosing the V that minimizes the root mean squared prediction error (RMSPE) of the pre-intervention outcome between the treated unit and the control unit. Then, W , which is a function of V , is picked to minimize the RMSPE of the predictor variables for a given V .

Below, after the SCM estimation and to evaluate the significance of our estimates, we report standardized p -values constructed from the distribution of placebo or permutation tests following Abadie et al. (2010) . This is done by estimating the same model on each untreated unit with the same intervention years and period and removing the actual treated unit from the potential donor pool of these other units. These are non-parametric exact tests, which have the advantage of not imposing any distribution on the errors. If the effect of the intervention on the treated unit is significant (not observed by chance), we should observe that the probability of finding comparable estimated effects in other units is very low ( Galiani and Quistorff, 2017 , for further details).

Unfortunately, the available data for CLM does not allow us to trace out a fully reliable series of PISA assessments since students of this region did not participate in the PISA installments of the years 2006 and 2012. This prevents us from making a reliable pre-trend analysis for the CLM case. Thus, we do not apply the SCM to this case, although we will provide some evidence based on a DID regression for this region.

2.3 Difference-in-differences analysis

After the SCM, we apply DID analysis to the PISA scores of Galicia for the sake of comparison with the SCM and to the PISA scores of CLM. In the case of the bullying data, where the pre-sample period is not long enough to apply the SCM, we also conduct DID estimation.

The DID equation can be written as follows: (3) Y i t = α + βPos t t × D i + γ x i t + δ i + τ t + u i t where subscripts i and t denote the region and year, respectively. The dependent variable, Y it , is our outcome of interest in each case, either students’ PISA scores or officially reported cases of bullying. Post t is a dummy-step variable taking on value 1 for the year of implementation and subsequent years (2015–2017); D i is a dummy variable for the treated region, capturing time-constant differences between it and the rest of regions if any. Vector X it contains three covariates, namely, the percentage of mobile phone usage by children in the region-year, real public spending on education in primary and secondary education and region-year per capita real disposable income. Finally, δ i stand for region-fixed effects (thus absorbing time-constant differences between the treated region and the rest of regions), τ t is a full set of year dummies and u it stands for the iid error of the model. In equation (3) , once region-level specific differences, common year effects and other region-year differences in covariates have been controlled for, parameter β identifies the treatment effect.

In the estimation below, we also show the results for an extended specification of equation (3) where we add a term pre t −1 × D i : (4) Y i t = α + β 0 pr e t − 1 × D i + β 1 Post t × D i + γx it + δ i + τ t + u it

The added term is the product of a dummy variable taking on the value 1 for some pre-intervention years times the dummy of the treated regions. In particular, we define pre t −1 as a dummy variable taking the value 1 for years 2012–2014 in our analysis of the PISA scores (and 0 otherwise), and a dummy variable taking the value 1 for the year 2014 in our analysis of bullying (and 0 otherwise). This term serves us to rule out the possibility that the differences between the treated and the control regions started to appear prior to the ban. In other words, the estimate of β 0 is expected to be non-significant for the DID estimation to be a valid identification strategy.

The equations above are estimated for Galicia and CLM separately, and in the analysis of bullying, we further estimate the model for the three mentioned age intervals: under-12, 12-14 and 15-17 years old school students.

3.1 Impacts on academic performance

In Table 2 and Figure 4 , we display the results for the SCM applied to Galicia. As already mentioned, the SCM provides a systematic data-driven procedure to create the (weighted) combination of regions that best resembles the actual Galicia before the implementation of the mobile phones ban. The SCM constructs the synthetic Galicia for PISA results on maths as a combination of Navarra (41.2%), Canarias (21.6%), La Rioja (14.4%), Extremadura (12.8%) and Cataluña (10%); for the PISA results in sciences, it is a combination of Castilla–León (79%), Islas Baleares (17%) Cataluña (3%) and Madrid (1%). All the other regions in the donor pool were assigned zero weights. The SCM estimation exhibits then sparcity in the choice of regions to construct the counterfactual ( Abadie, 2021 ), and also, as can be seen at the bottom of Table 2 , a close match between the pre- and post-intervention values of the predictors and low pre-intervention prediction error (root of the mean square prediction error, RMSPE, of around 0.4 for outcome variables that have average values of around 490).

Figure 4 permits us to visualize the almost perfect fit between the treated unit (Galicia) and its synthetic counterpart in the pre-intervention period. However, after the ban, there is a positive gap in favor of the Galicia region in both PISA indicators. In maths, this positive gap seems to respond to a combination of increasing scores in the case of Galicia and somewhat decreasing scores in the synthetic Galicia (though these latter scores do not fall below the pre-trend average values). In the case of sciences, the decline in the PISA results exhibited in the synthetic Galicia is more noticeable. This decline in Spanish students’ PISA scores in the past years, and particularly in the 2018-call, has been explicitly highlighted ( Stegmann, 2019 ). Further, this trend does not seem to be exclusive of the Spanish case. As documented by Rowley et al. (2019) and contrary to expectations –in authors’ words–, few countries significantly increased their PISA scores in recent years, and in many of the cases, the change is indeed negative. If we had to think on a global common phenomenon affecting young teenagers, the outbreak of the use of mobile phones would be a candidate. Further, in the standard DID estimation applied to the PISA data that we offer below, we find that regions with a higher percentage of teenagers’ mobile phones users have experienced, other things equal, a larger and significant decline on PISA results in the past years. Thus, one of the plausible explanations for the observed academic decline could be the intensification in the use of mobile phones among the youngest and the distraction that they introduce in their learning time. It follows that the control of their usage in school time might have allowed the treated region to escape from such declining trend.

The estimated effects are of an order of magnitude of around 10.7 and 12.7 points on maths and sciences, respectively, in the year 2017 (when the outcome takes the value of the PISA assessment of 2018). In addition, the p -values derived from the placebo tests in the SCM analysis indicate that for no other region, the SCM finds comparable results to the ones obtained for the treated region. Given that the average of PISA scores for Spanish students in maths and sciences are around 10–12 points below the international average of 500, the magnitude of the estimated effects would imply catching up with the OECD mean in a relatively short period of time. To evaluate further the magnitude of these effects, we can consider that, as a rule of thumb, the average student learning in a year is between one-quarter and one-third of a SD of the PISA scale, that is, around 25–30 points on the scale ( Woessmann, 2016 ). According to this, our estimated effects are equivalent to 0.6–0.8 years of learning in maths and around 0.72 to near one year of learning in sciences. On top of that, the economic consequences of these improvements are potentially very relevant. According to the OECD Report-2010 on the long-run impact of improving PISA outcomes ( Hanushek and Woessmann, 2010 ), a modest goal of having all OECD countries boost their average PISA scores by 25 points over the next 20 years would imply an aggregate gain of OECD gross domestic product (GDP) of US$115tn over the lifetime of the generation born in 2010 (p. 8).