At the Smithsonian | March 24, 2021

The Soaring Legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen

The 80th anniversary of the first Black flying unit is a time to recall the era when military service meant confronting foes both at home and abroad

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f5/ae/f5ae3953-c39a-4fbd-a74b-434af49336da/longform_mobile.jpg)

Allison Keyes

Museum Correspondent

“Somebody had to do it,” says Lt. Col. Alexander Jefferson , a 99-year-old member of the renowned Tuskegee Airmen . As the first Black pilots in U.S. military service, the Airmen's bravery both in the air and in enduring racism made them legends and the personification of honor and service.

“We had to rise to the occasion,” recalls Jefferson, a proud member of the 332nd Fighter Group and one of the class of pilots known as “ Red Tails ” after the distinctive markings on the P-51 Mustangs that they flew. On missions deep into enemy territory, including Germany, they escorted heavy bombers to their targets. “Would we do it again? Hell yes! Would we try doubly? You’d better believe it. Did we have a lot of fun? At gut level, it was great!”

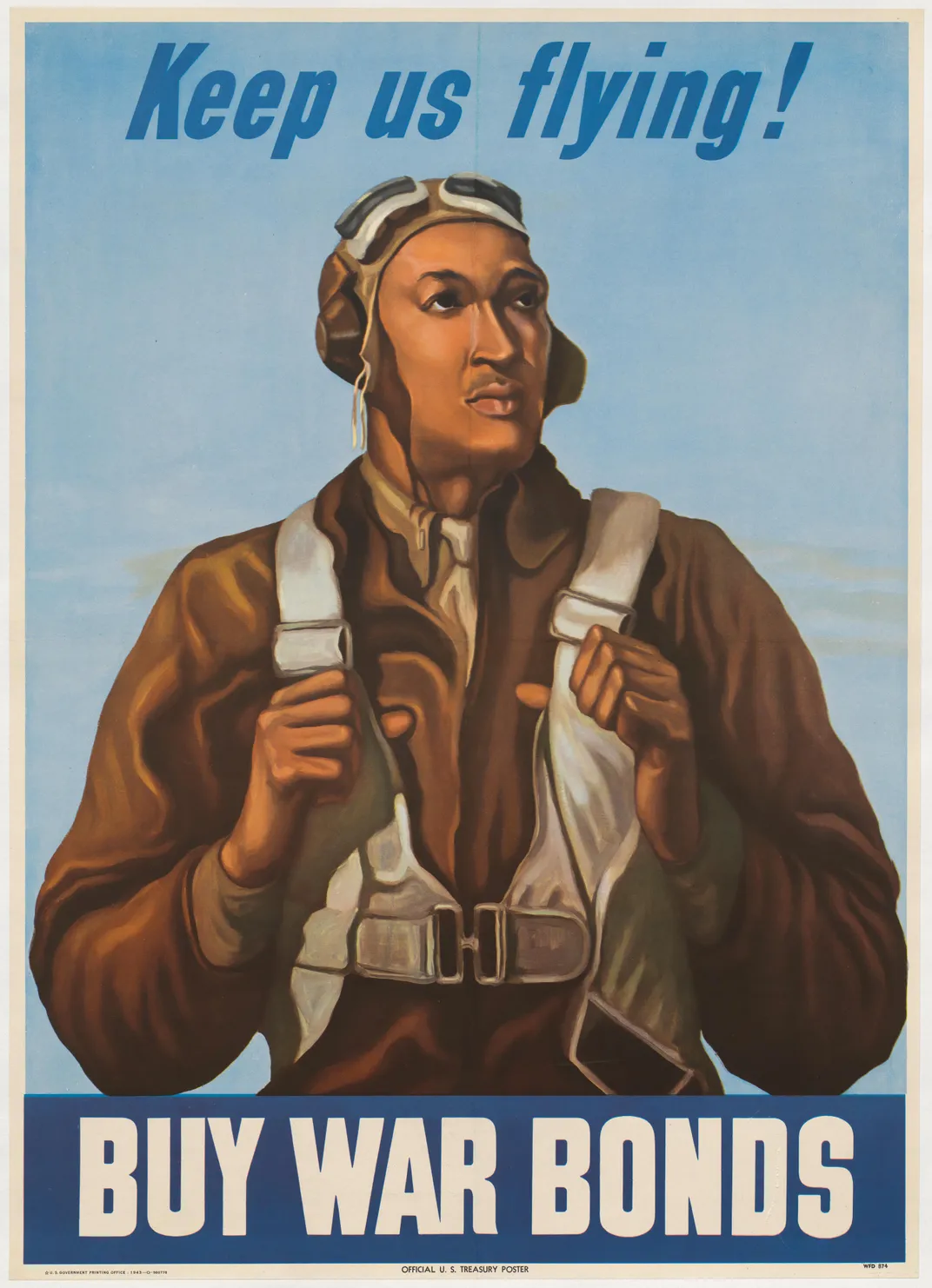

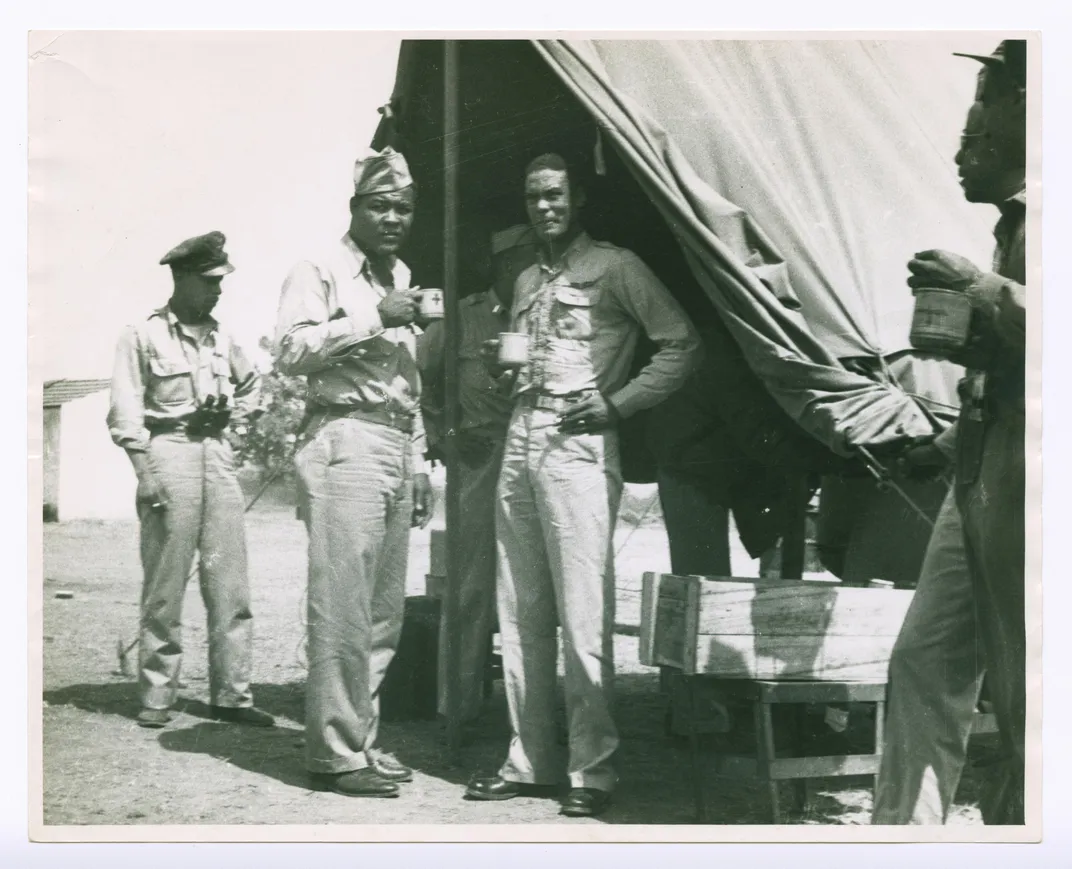

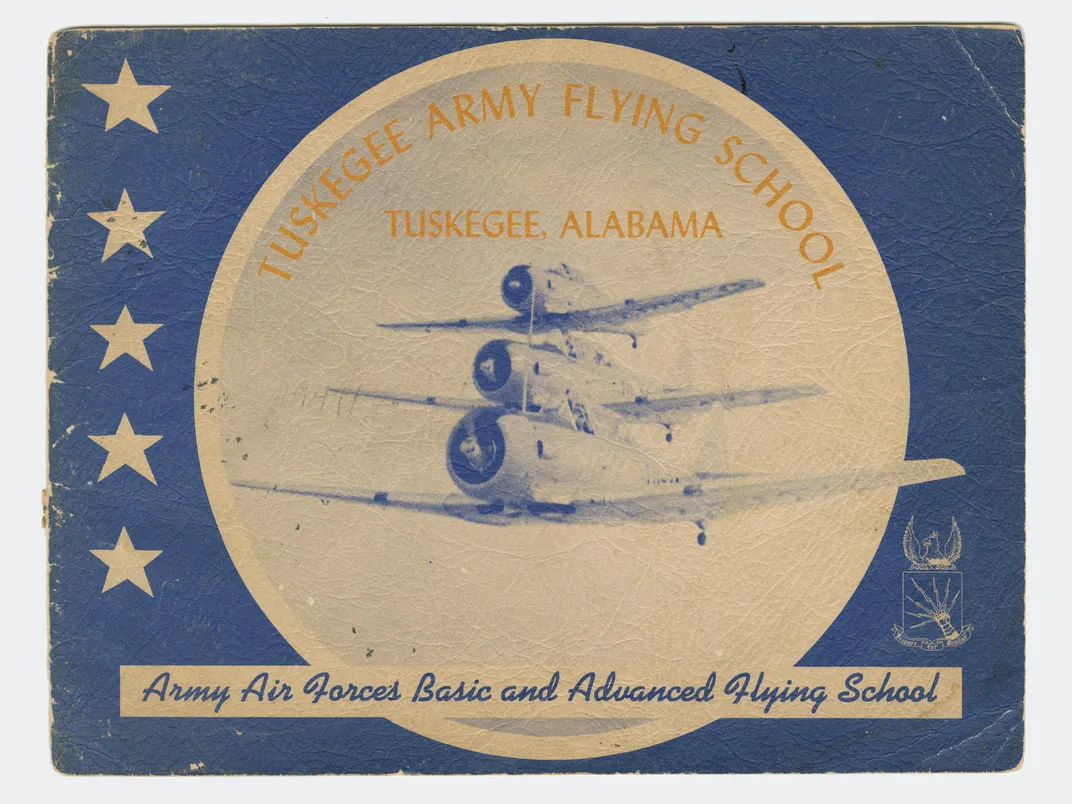

This week, March 22, marks the 80th anniversary of the activation at Chanute Field, Illinois, of the first Black flying unit, the 99th Pursuit Squadron . Later known as the 99th Fighter Squadron, it moved to Alabama's Tuskegee Army Airfield in November 1941. The first Black pilots graduated from advanced training there in March 1942. Eventually, nearly 1,000 Black pilots and more than 13,500 others including women, armorers, bombardiers, navigators and engineers in various Army Air Force organizations who served with them, were included in what is known by Tuskegee Airmen, Inc . as the “Tuskegee Experience” from 1941 to 1949.

The Tuskegee Airmen flew more than 15,000 individual sorties in Europe and North Africa during World War II and earned 96 Distinguished Flying Crosses. Their prowess, in a military establishment that believed that black Americans were inferior to white Americans and could not possibly become pilots, became what many see as the catalyst to the eventual desegregation of all military services by President Harry S. Truman in 1948. Facilities around the country, including the Tuskegee Airmen National Museum in Detroit, have a plethora of artifacts dedicated to telling their story. In Washington, D.C., the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) has an aircraft known as the “ Spirit of Tuskegee ” hanging from the ceiling. The blue and yellow Stearman PT 13-D was used to train Black pilots from 1944 to 1946.

Lt. Col. Jefferson didn’t train on that aircraft, but he got to take a ride in it in 2011 , before it arrived at Andrews Air Force Base. The plane was bought and restored by Air Force Captain Matt Quy, who flew it across the country to donate it to the museum. The training aircraft made several stops at air shows and airfields across the nation, including its original home at Moton Field during World War II, in Tuskegee, Alabama. Quy flew the “Spirit of Tuskegee” that year over a hotel at Maryland's National Harbor, during a Tuskegee Airmen convention. Forty of the original airmen and hundreds of other members of the legendary group were on hand, celebrating the 70th anniversary of their first training missions.

“It was fantastic,” Jefferson recalls, adding that it reminded him of a similar aircraft on which he learned to fly. “It brought back memories of my first ride in a PT-17 .”

Smithsonian curator Paul Gardullo , who says collecting the Stearman PT-13 was possibly one of the most momentous things he helped accomplish for NMAAHC, also got to take a ride in the open cockpit biplane. He notes it is one of a host of aircraft used by the Tuskegee Airmen that do not have red tails like the famous P-51s.

“When you take off, you don’t necessarily feel that strong thrust like you do in a typical 747. It’s slow, it’s easy, and because it’s open, you feel like you are part of nature. You feel everything around you,” Gardullo says. “What it provides is this incredible sense of your connection to that machine because it is so small, your connection to the world around you and your ability to control your destiny. That’s what I think is such an empowering thing when I think about these men who are learning to fly for the first time, and that’s what they talk about.”

Gardullo says the P-51 is a deeply important and symbolic plane, especially the red tail. But he says when he spoke with some of the Tuskegee Airmen who saw the training plane as it made its journey across the nation, particularly at its stop in July 2011 in Tuskegee, he got an evocative, incredible history lesson.

“We learned about the trials that they went through, not just the technical trials of learning how to fly a plane, but learning how to fly a plane in the Jim Crow South, and what it meant to hold a position of esteem and authority, and demonstrate your patriotism in a country that isn’t respecting you as a full citizen,” Gardullo explains. “That brought us face to face with what I call a complex kind of patriotism. And there’s no better example of that than the Tuskegee Airmen, the way in which they held themselves to a standard higher than the nation held them in esteem. It’s a powerful lesson, and its one we can’t ever forget when we’re thinking about what America is, and what America means.”

The Smithsonian’s Spencer Crew , who most recently held the position of NMAAHC’s interim director, notes that the history of the Tuskegee Airmen is remarkable, and that their battle goes all of the way back to World War I, when Black Americans lobbied the federal government to participate in the war as airmen, and to fight aerial battles. At that time, because of segregation, and the belief that Black people could not learn to fly sophisticated aircraft, they weren’t allowed to participate. In 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced that the U.S. Army Air Corps (AAC), a precursor of the U.S. Air Force, would expand its civilian pilot training program. Then the NAACP and Black newspapers such as the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier began lobbying for African American inclusion.

“What happened is that Congress finally puts pressure on the War Department to allow African Americans to train to be pilots, and the War Department figures they don’t have the skills, the abilities or bravery to be airmen. They think, ‘What we’ll do is send them to Alabama and attempt to train them, but we expect that they will fail,’” Crew explains. “But instead, what happened is that these really, brilliant men go to Tuskegee, dedicate themselves to learn how to fly and become a very important part of the Air Force. They were highly trained when they got to Tuskegee in the first place. Some had been trained in the military, many had been engineers, and they just brought a very high skill level with them to this work.”

A look at a few of their resumes, before and after being Tuskegee Airmen, is stunning. General Benjamin O. Davis Jr ., part of the first class of aviation cadets, was a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, who commanded both the 99th Fighter Squadron and the 332ndd Fighter Group, and became the first Black general in the Air Force. He is the son of General Benjamin O. Davis Sr., the first Black American to hold the rank in the U.S. Army. General Daniel “Chappie” James , who served in the 477thBombardment Group, flew fighter aircraft in the Korean and Vietnam wars, and became the first African American four-star general in the Air Force. Brigadier General Charles McGee , who served with the 332nd Fighter Group in World War II, also served in Korea and Vietnam, and flew 409 combat missions. Lt. Col. Jefferson, also with the 332nd Fighter Group, is the grandson of Rev. William Jefferson White, one of the founders of what is now Morehouse College in Atlanta. Jefferson worked as an analytical chemist before becoming a Tuskegee Airmen. He was shot down and captured on August 12, 1944, after flying 18 missions for the 332nd, and spent eight months in the POW camp at Stalag Luft III before being freed. He received the Purple Heart in 2001.

Jefferson, who will turn 100 years old in November, says the 80th anniversary of the beginning of the Tuskegee Airmen training program is very close to his heart, partly because there are so few of them left. He remembers what it felt like to begin the flying courses at the small airfield there, learning the craft from Black instructors. He says one had to volunteer for flight training, because even though African Americans were subject to the draft in the segregated military, that would not get you into the flying program.

“If you were drafted as a Black man, you went into a work situation where you were a private in a segregated unit doing nasty, dirty work with a white commander,” he remembers, adding that it was exciting to be breaking the rules society at the time had set up for African Americans. As an airman, one was an officer under better conditions, with better pay and a sense of pride and accomplishment.

“It was a situation where you knew you were breaking rules, but you were making progress, breaking ground,” Jefferson says. “We knew that we would be relegated to a segregated group, the 332nd Fighter Group, under the racial attitude of the government and we were fighting that too.”

He says he and the other Tuskegee Airmen think sometimes about how their achievements, in the face of deep racism, helped pave the way for other Black pilots.

“Here we were, in a racist society, joining up to fight the Germans, another white racist society, and we’re right in the middle,” Jefferson says, adding “we tried to do our job for the United States.”

Historian and educator John W. McCaskill gives lectures and does reenactments of military history including World War II and the Tuskegee Airmen, and has been helping to tell their story for decades. He wears their period attire, and his “History Alive” presentations sometimes involve one of the Red Tail planes. McCaskill helped get recognition for Sgt. Amelia Jones , one of the many women who worked in support capacity for the Tuskegee Airmen, under then Col. Davis Jr. with the then 99th Pursuit Squadron.

“It wasn’t just the pilots. It was anybody who was part of the Tuskegee Experience,” explains McCaskill, who met Jones in 2014 at the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C., as part of the “Living History Meets Honor Flight” program. Once she told him she had been with the 99th, and sent her discharge papers, McCaskill and others were able to get her into Tuskegee Airmen Inc., and got her sponsored for a Congressional Gold Medal . It was awarded collectively to the Tuskegee Airmen in 2007.

“As a sergeant, she had about 120 women that she was in charge of, and they were dealing with mail, sending mail overseas,” McCaskill explains.

He says as the nation honors the service of the Tuskegee Airmen, it is important for people to understand just how much service Black people have provided for the military, and for the stories of the African American experience in military history to continue to be told. It is critical, he says, on their 80th anniversary.

“African Americans played a critical role in World War II, and just about 2,000 Black Americans were on the shores of Normandy on D-Day . But if you look at the documentaries and newsreels you don’t see them,” McCaskill says. “What this 80th anniversary says to me is that there are still people 80 years later who don’t know about this story and it needs to get out. Every time we lose one of them, we’ve got to ask the question: ‘Have we learned everything from that individual that we were supposed to learn?’ We cannot allow this story to die because every Black pilot, male or female, that sits in a military cockpit or commercial cockpit, owes a debt of gratitude to these individuals who proved once and for all that Blacks were smart enough to fly, and that they were patriotic enough to serve the country.”

Back at the Smithsonian, Crew says the PT-13 training plane that hangs from the ceiling is a wonderful representation of the important kinds of contributions that African Americans have made.

“What it does is remind our younger visitors of the possibilities of what you can do if you just decide to put your mind to it, and if you don’t let others define what you can accomplish and who you are in society,” Crew says, adding that this is of great importance due to the current level of division in the nation.

Lt. Col. Jefferson also has a message for young people.

“Stay in school, and learn how to play the game,” Jefferson says. “Fight racism every time you can.”

Editor's Note 5/3/2021: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that the Tuskegee Experience ended in 1946; it ended in 1949. The story also said that the Tuskegee Airmen earned more than 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses; they earned 96. The story has been edited to correct these facts.

Get the latest on what's happening At the Smithsonian in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

Allison Keyes | | READ MORE

Allison Keyes is an award-winning correspondent, host and author. She can currently be heard on CBS Radio News, among other outlets. Keyes, a former national desk reporter for NPR, has written extensively on race, culture, politics and the arts.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

How Tuskegee Airmen Fought Military Segregation With Nonviolent Action

By: Farrell Evans

Updated: January 22, 2024 | Original: January 20, 2021

The Tuskegee Airmen are best known for proving during World War II that Black men could be elite fighter pilots. Less widely known is the instrumental role these pilots, navigators and bombardiers played during the war in fighting segregation through nonviolent direct action. Their tactics would become a cornerstone of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s.

The Tuskegee Airmen’s most influential moment of collective civil disobedience came in the spring of 1945, in what became known as the Freeman Field Mutiny. After enduring years of inadequate training facilities, discriminatory policies and hostile commanders in the Army Air Force, 101 officers of the all-Black 477 th Bombardment Group—who had initially trained at the Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama—were arrested at Indiana’s Freeman Field base when they refused to sign a base regulation requiring separate officers’ clubs for Black and white soldiers. The order came after 61 Black officers were arrested trying to enter the white officers’ club.

They weren’t alone. After the War Department ordered military bases to integrate all recreational facilities in 1944, Black officers across the country were eager to test the new policy. Most cases—including an earlier incident with the 447 th —involved Black servicemen “entering post exchanges and asking to be served, or entering the theater and seating themselves in the white section,” said Alan M. Osur, a former history professor at the Air Force Academy and the author of Blacks in the Army Air Forces During World War II: The Problems of Race Relations. Nothing had yet occurred on the scale of the Freeman Field Mutiny.

Separate, but Not Equal, Facilities

Their actions sprang out of a long-simmering debate over the unequal treatment of Black and white officers and the integration of officers’ clubs. “The country is not ready to accept white officers and colored officers at the same social level,” said Major General Frank Hunter, the commanding general of the 477 th Bombardment Group. “I base that opinion on the history of this country for the past 125 years.”

At Freeman Field, Hunter’s subordinate, Colonel Robert Selway, established two allegedly equal officers’ clubs—one for the white officers, who were designated as instructors and the other for Black officers, who were classified as trainees. But the two clubs were anything but equal. The white officers’ club had a large fireplace and game room with pool tables, table tennis and card tables, while its Black counterpart was heated by coal stoves and contained none of the aforementioned amenities.

The Black officers nicknamed their officers’ club “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and refused to patronize it, according to Todd Moye, the author of Freedom Flyers: The Tuskegee Airmen of World War II and the director of the National Park Service’s Tuskegee Airmen Oral History Project. “Selway attributed his decision to the belief that fraternization between instructors and trainees would have an ill effect on the group’s training,” Moye said. “In truth, the effort was a transparent attempt to circumvent both the letter and the law...which prohibited segregation of base facilities by race.”

‘You can’t come in here.’

On April 5, 1945, the Black officers of the 477th began an orchestrated attempt over two days to integrate the white officers’ club at Freeman Field. The officers were led by Lt. Coleman A. Young, a bombardier and navigator and former United Auto Workers organizer in Detroit, who had successfully helped integrate the officers’ club at the Midland, Texas Army Air Field the year before.

At a strategy session a few days before the start of the Freeman Field sit-ins, Young and a group of Black officers decided to use nonviolent action and to enter the white officers’ club in small groups so it wouldn’t appear coordinated. “They were prepared for our arrival, expectin’ trouble. MPs were there to keep us out of the club the night we arrived,” said Young, who later became the first Black mayor of Detroit. “We were gonna scatter, play pool, get a drink, buy cigarettes. The white captain says: ‘You can’t come in here.’ We just brushed past him and scattered. The commandin’ officer was livid and placed us under arrest, at quarters.”

Young, who recounted the episode in an interview with the oral historian Studs Terkel, went on to say it was his responsibility to convince others to continue with the plan. “After the first nine it was tough gettin’ the next nine. But we broke the ice, and two more groups went in and were place[d] under arrest... They wanted to put us in a position of disobeying a post command.”

Base Regulation 85-2

With the exception of three officers charged with “jostling” a white commanding officer at the officers’ club, Young and 57 other officers who were arrested were released to their quarters on April 9, four days after the start of the sit-ins. But Hunter and Selway doubled down on their racist policies by issuing Base Regulation 85-2 to strengthen and clarify their position on the issue, according to Lawrence P. Scott and William M. Womack, authors of Double V: The Civil Rights Struggle of the Tuskegee Airmen.

Base Regulation 85-2, which mandated segregation of officers by unit (which, in effect, meant race), was posted around the base. Selway ordered all officers, Black and white, to appear individually before a board and attest that they fully understood 85-2. All 292 white officers signed the regulation, while 101 of 422 Black officers refused. “A few of the trainee officers signed it as written, some signed it striking out the words ‘and fully understand,’ and others signed it, but wrote endorsements claiming it was racial discrimination,” Selway wrote in his report.

The 101 Black officers who refused to sign were placed under arrest and flown secretly to Godman Army Air Field in Kentucky, where they were put on temporary duty for 90 days. The three Black officers accused of “jostling” with military police were held back at Freeman to be court-martialed. According to Moye, Black officers still at Freeman continued to try entering the white officers’ club. “When the men approached the club, Colonel Patterson would ask who the spokesperson for the group was, and all of the members would respond, ‘no one,’” Moye wrote.

A Consideration of Capital Punishment

On April 25, 1945, 12 days after their arrest, the 101 Black officers were released with a reprimand on their records—after pressure from the NAACP , the National Urban League and the Black press. According to Scott and Womack in their book Double V, General Hunter had wanted the men court-martialed, but the Judge Advocate General’s office deemed the administrative reprimand adequate punishment because “trying the officers on violation of the 64 th Article of War could result in capital punishment, something the army could not politically afford.”

Following the airmen’s release, George S. Schuyler, a columnist for the African American weekly Pittsburgh Courier, praised the decision: “It is impossible for any man to be a first-class officer if constantly forced into a second-class position,” he wrote. “It is a pleasure to note that the War Department has had the good sense to release these young men to duty.”

The three Black officers charged with “jostling” in the white officers’ club stood trial. Two, Marsden Thomson and Shirley Clinton, were acquitted and fined. Roger “Bill” Terry, the third officer, was represented by the future Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall . A University of California, Los Angeles graduate, Terry was court-martialed and acquitted on the charge of disobeying an officer, but found guilty of “jostling.” Given a $150 fine, he received a dishonorable discharge in November 1945 with a reduction in rank.

The Civil Rights Legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen

In 1995, President Bill Clinton pardoned Terry, restored his rank to Second Lieutenant and refunded his $150. At the same time, Clinton removed General Hunter’s reprimand letters from the permanent files of 15 of the 104 officers charged in the protest. The Air Force also promised to remove the reprimands of the other 89 officers once they were filed.

Terry, who went on to earn a law degree and work as an investigator in the Los Angeles District Attorney’s office, never got to fly overseas during World War II. But he did witness how the 477th Bombardment Group’s nonviolent direct action tactics at Freeman Field influenced the civil rights movement where sit-ins at lunch counters and bus stations transformed the American South.

“We think that it broke the camel’s back because they had to recognize the fact that 104 officers were arrested, and that they all defied this order, and the order was said to be illegal,” Terry said in an interview for the National Park’s Tuskegee Airmen Oral History Project. “We feel—and I think I speak for most of the guys—that it was our advantage that we gave to the Negro people, that there would be no discrimination in the Army Air Force from that time on—at least officially. In 1948, President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981, ordering all U.S. military forces to desegregate.

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Search form

Alumni news essay: remembering tuskegee airman gen. charles mcgee.

When I was a high school senior almost 40 years ago, the English teacher assigned us to choose a hero, read a book, and write an essay explaining why. I chose Jackie Robinson for reasons I don’t remember exactly and didn’t understand deeply. I recognized that was an atypical choice for a Jewish girl growing up in predominantly white suburban New Jersey, but preferred reading sports books since my elementary school days. Perhaps it was related to my experience as an 8-year-old breaking the gender-barrier to play in the local baseball and basketball leagues, along with my older sister, when the new Title IX law made that possible. Perhaps it was related to my friendship through pick-up basketball with a Black family in my hometown from nearby Newark — where my parents were married, my father went to college, my paternal relatives are buried, and my paternal cousins grew up and participated actively in the Civil Rights Movement. Perhaps it was my budding Jewish identity and social justice values, knowing family friends who were Holocaust survivors.

Three years ago I went to an education festival at the National Air and Space Museum near my house in multicultural suburban Virginia, even though I have no particular interest in aviation. I noticed an elderly gentleman sitting alone at a bookselling/signing table with his biography, along with a pencil and paper to keep track of sales. Then I saw a sign identifying him and paused in amazement, as if I had seen the burning bush: Tuskegee Airman, born Dec. 7, 1919. I walked over and said casually, “I see you’re gonna have a big birthday next year.” He smiled gently and replied humbly, “God willing and if the creek don’t rise.” Charles McGee had a very big 100th birthday indeed — which included a belated promotion to general, a moment of national honor at the State of the Union, another such moment at the Super Bowl coin toss, and piloting a plane — as he had done when he turned 99, and as he had done 409 times as a fighter pilot in Europe during World War II, Korea, and Vietnam.

That’s how I made acquaintance with my new hero, to add to a handful of Holocaust survivors I knew, who rebuilt rich lives in America and contributed their stories, values, and energies to serve the Jewish community and others. He opened my eyes to see American history through a longer and finer lens of social progress at a personal level. During the years of serving in an experimental segregated unit in WWII, shortly before Jackie Robinson broke the color line in baseball, the Tuskegee Airmen disproved the myth of racial inferiority and defended both American and Jewish lives. In so doing they built the strongest case for the subsequent integration of the military and amplified the moral imperative to deliver on the promise of equality across society.

Regretfully, I hesitated and didn’t buy his book that day. However, I Googled him soon afterward and started to learn his story, and grew to understand and admire the incredible feats of the Tuskegee Airmen as pioneers. Thankfully, I didn’t hesitate when his inspiration gave me the idea to invite him as the special guest of honor for a Black History Month speaker event that I led at work last year. Amazingly, he accepted my invitation and joined via Zoom together with his daughters, and honored us all with his presence. Belatedly, I did read and relish his biography, written by Charlene McGee Smith — his eldest daughter and namesake — who spoke beautifully on his behalf.

Why did he choose to come for my modest occasion? After a highly decorated 30-year career in the U.S. Air Force, he never retired and continued to serve our country as a founder, leader, and ambassador of the Tuskegee Airmen’s national association. He believed deeply in the bedrock values of education and equal opportunity, and enjoyed making his priceless contributions to encourage the next generations.

I know he also came to listen to the guest speaker: Joylette Goble Hylick, eldest daughter of Katherine Johnson — the Hidden Figures hero and NASA research mathematician, who died one year prior at the age of 101 after a brilliantly well-lived life. I never met Mrs. Johnson but feel as if I did from reading her memoir, watching interviews, visiting museum exhibits near her homes in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, and Hampton, Virginia, and interacting with Joylette to share her mother’s uplifting legacy with others.

Charlene spoke honestly and compellingly about the current racial reckoning, saying: “You have to know Mrs. Johnson’s story, and you have to know Gen. McGee’s story. You have to understand there is greatness in the history of African Americans in this country.” In response, I could only say: Amen.

The memorial tributes to Gen. McGee have been tremendous, including heartfelt Twitter messages by the secretary of defense Lloyd Austin and the chief of the U.S. Air Force Gen. Charles Q. Brown, both African American. Vice President Kamala Harris did likewise and attached the video of her call for his 102nd birthday, saying: “I can’t thank you enough, and on behalf of the president and myself and our nation, I just want to thank you for all that you have done, and you know, telling your story is about telling the story of our nation.”

I am but an ordinary citizen with a wee small voice, who plays a barely-speaking bit part, as one of the many among We the People, who have been trying for centuries to form a more perfect union. Soon after the event, Charlene sent the nicest thank-you note I will ever receive, affirming her belief that such humanizing encounters matter. Gen. McGee and his younger daughter Yvonne called me kindly as well. (I remember telling him that I woke up early that morning feeling my nerves, and calmed down a bit when I thought of him, since no one was shooting at me.) I continue to play my bit part in my corner of the country, and try to follow in Gen. McGee’s and Mrs. Johnson’s giant footsteps in very small but meaningful ways. They taught and encouraged me to “pay it forward” for racial justice, by using their epic stories and my own educational privilege to reach out and teach others.

I knew to invite Gen. McGee because I perceived intuitively that he was like Ann, who never retired from telling her story to young generations. On display near her kitchen table was an oversized photo of the Jewish high school class that invited her to speak. Together with her son and primary caregiver Jay, she looked beautiful and vibrant in her late 80s, even as she lived with pancreatic cancer.

We are all part of each other’s stories in The American Story. May we choose our heroes wisely, and be so incredibly fortunate and blessed to know them.

Epilogue: B’Zchut (On the Merit)

Joylette texted me a few minutes after the Black History Month event saying, “Great program.” (Wow, coming from Mrs. Johnson’s daughter, that means something.) I texted back that her words were soulful. The most heart-warming moment, in my eyes, was her response when I asked during the Q&A what the Tuskegee Airmen mean to her, as a member of her fine family:

“Those men were on a mission, they did their job, and we got the best of the best… The fact (is) that during World War II they had to beg to be involved… I just adore them. Every time I see something about them, I’m so happy. I was with Mom when she was honored with one of them a few years ago in Virginia. So, my hat’s off to Gen. McGee, and I’m so happy to share the day with him.”

That expressed my sentiments exactly. Listening to the event recording a year later, a few days after attending the public viewing in Washington, D.C., and watching the memorial service at his church via livestream, I sat back and tried to imagine how it felt for him to hear that genuine gift of words, as he sat at home with his daughters listening silently. Connecting their families with Joylette’s voice was the best expression of gratitude I could give him. Yvonne sent me a sweet email that I still treasure: “Thank you for saluting Dad. He was able to listen and really enjoyed, just sorry he wasn’t up to being on camera (still in PJs) or answering questions.” Together we fulfilled the fourth commandment of lich’vod horim — honoring parents. I like the image that he was able to come comfortably, without his formal uniform and impressive medals, and enjoy a heimish style of celebration.

It was a sacred moment, beyond words, when I saw him for the last time. After giving my condolences and hugs to Charlene and Ron, his son, I paused beside his casket and turned to him panim-el-panim — face-to-face. I looked at his endearing gentlemanly face and distinctive features, with eyes closed and lips sealed. I looked at his hands holding a folded American flag, and his chest wearing the distinguished traditional red jacket of the Tuskegee Airmen as proud Red Tails. I felt the silence of his presence — after all the historic sights he saw, kind words he spoke, and acts of bravery and human decency he did in his tremendously full lifetime of giving. The echo of his voice and his dugma ishit — personal example — are inside me now to give back. The seemingly mystical seeds of inspiration that he sprinkled toward me at that first encounter three years ago have since grown into blooms with roots.

I told Charlene and Ron that their Dad reminded me of another general, Yitzchak Rabin, whose public viewing I attended after his tragic assassination in 1995, when I was living and working in Jerusalem on Israeli-Palestinian cooperation projects. What I have begun to do to contribute to the racial reckoning b’govah eynayim — at eye-level (literally, the height of eyes, implying a sense of equality) — I do because of Gen. McGee. I do it b’zchuto — literally, on his merit, better translated as thanks to the privilege of knowing what I know because of him.

Debby Greenberg ’87 has worked in software consulting for federal/state/local governments, and learned how to lead her first Black History Month event by working in Jerusalem on Israeli-Palestinian cooperation projects. She lives in a diverse and inclusive community in Herndon, Virginia.

- Henry B. Tippie NAEC

- General Staff

- Hall of Fame

- Headquarters Staff

- Non-Profit Information

- Photo Gallery

- 2024 Victory Ball

- New Unit Initiative

- 2024 Normandy Tour

- 2024 CAF Conference

- Membership Options

- Renew Membership

- Member Benefits

- Join Victory Circle

- How To Get Involved

- Find A Location

- Contact Member Services

- Ways To Give

- Victory Plaza Brick Campaign

- Gift Acceptance Policy

- Media Inquiries

- Update My Info

- Aircraft Rides

- CAF Documents

Tuskegee Airman Essay Contest

Calling all students 4th through 12th grade! Submit your essay for the CAF Red Tail Squadron’s annual contest saluting the Tuskegee Airmen! Deadline is March 15, 2021.

Using the Six Guiding Principles (Aim High, Believe in Yourself, Use Your Brain, Be Ready to Go, Never Quit, Expect to Win) describe how the Tuskegee Airmen achieved success, or choose a goal for yourself and show how you could use the Six Guiding Principles to achieve that goal.

Entries will be judged on overall content, including spelling, grammar, and punctuation.

Each entry must be an original composition written by the student.

The Essay Contest is open to students in the 4th – 12th grade in an accredited school or home school program during the academic year.

Entries must adhere to the following word count guidelines:

4th – 5th grades 250 words 6th – 8th grades 350 words 9th – 12th grades 500 words Footnotes, citations, endnotes, and essay titles will not be counted as part of the word count allotment.

Entries must be typed. Each page of the essay must include the author’s name, name of school or home school program, address and telephone number in the upper right hand corner of each page. This information will not be counted as part of the word count allotment.

Entries become property of the CAF Red Tail Squadron and will not be returned.

Winners will be requested to send their photograph to be featured along with their essay on the CAF Red Tail Squadron website and newsletter.

Entries must be emailed prior to 5:00pm on or before March 15, 2021. Email your entry to: [email protected]

Essay contest winners will be announced on March 30, 2021.

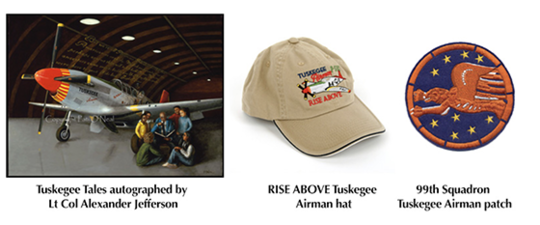

Prizes will be awarded to the 1st, 2nd and 3rd place winners in each grade category as follows:

1st place: An autographed print of “Tuskegee Tales” 2nd place: A RISE ABOVE hat 3rd place: A 99th Squadron Tuskegee Airmen patch

CAF RISE ABOVE ®

- Rise Above: Red Tail

- Rise Above: WASP

- Six Guiding Principles

- RISE ABOVE Traveling Exhibit

- The Aircraft

- Newsletters

- Tuskegee Airmen Profiles

- Tuskegee Airmen Pilot Roster

- The Airfields

- Support Crews

- Mrs. Roosevelt

- War Service

- Tuskegee Airmen KIS / MIA

- Returning Home

- Red Tail Virtual Museum

- Six Guiding Principles for the Tuskegee Airmen

- Additional Resources

- Avenger Field

- WASP Killed in Service

- General ‘Hap’ Arnold

- After the War

- WASP Profiles

- WASP Virtual Museum

- Six Guiding Principles for the WASP

- Educational Resources

- Top Flight Club: Red Tail

- Top Flight Club: WASP

- Honorary Flight Log

- Non-Profit Information

- Rise Above essay contest

Calling all students 4th through 12th grade! Submit your essay for the CAF Rise Above Squadron’s essay contest saluting the Tuskegee Airmen or the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP)!

Using the Six Guiding Principles (Aim High, Believe in Yourself, Use Your Brain, Be Ready to Go, Never Quit, Expect to Win) describe how the Tuskegee Airmen or the WASP achieved success, or choose a goal for yourself and show how you could use the Six Guiding Principles to achieve that goal.

Entries will be judged on overall content, including spelling, grammar, and punctuation.

Each entry must be an original composition written by the student.

The essay contest is open to students in the 4th – 12th grade in an accredited school or home school program during the academic year.

Entries must adhere to the following word count guidelines:

- 4th – 5th grades 250 words

- 6th – 8th grades 350 words

- 9th – 12th grades 500 words

Footnotes, citations, endnotes, and essay titles will not be counted as part of the word count allotment.

Entries must be typed. Each page of the essay must include the author’s name, grade level, name of school or home school program, address and telephone number in the upper right-hand corner of each page. This information will not be counted as part of the word count allotment.

Entries become property of the CAF Rise Above Squadron and will not be returned.

Winners will be requested to send their photograph to be featured along with their essay on the CAF Rise Above Squadron website, Facebook page and newsletter.

Entries must be emailed prior to 5:00pm on or before February 15, 2024. Email your entry to: [email protected]

Essay contest winners will be announced on March 15, 2024.

Prizes will be awarded to the 1st, 2nd and 3rd place winners in each grade category as follows:

1st place: MA-Flight backpack black or sage

2nd place: Mustang model kit of the P-51C “Tuskegee Airmen”

3rd place: Choice of aviator wings: TUSKEGEE AIRMEN or WASP

All entries will receive a Rise Above dog tag and Triumph Over Adversity booklet.

Home — Essay Samples — Government & Politics — Tuskegee Airmen — Review Of The Film Tuskegee Airmen

Review of The Film Tuskegee Airmen

- Categories: African American History Tuskegee Airmen

About this sample

Words: 590 |

Published: May 14, 2021

Words: 590 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: History Government & Politics

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 760 words

2 pages / 771 words

1 pages / 623 words

2 pages / 1154 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Tuskegee Airmen

In 1941, on the United States Air Corps base in Tuskegee, Alabama, a group of young African American men created history as the first colored fighter pilots in American history. During a global war against racism, these young [...]

The Salvation Army is a Protestant Christian movement and an international charitable organization structured in a quasi-military fashion. The organization reports a worldwide membership of over 1.5 million, consisting of [...]

In this essay we will discuss punctuality and work ethic as a military prep student and future employee. Some of the questions I will talk about will include why punctuality is essential to course and work, what affects dose [...]

Sometimes our expectations are different from reality. Last summer, I participated to the JROTC summer camp. I expected I would have a fun time playing volleyball, swimming and making new friends. But in addition, the summer [...]

The article tackles the challenges Afghanistan and Iraq veterans faced while transitioning from military to civilian life. Apparently, one of these challenges was the lack of transitional assistance from the government. A lot of [...]

Booker T. Washington once said, “Those who are happiest are those who do the most for others.” The Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, also known as JROTC, provides young adults a federal program that inspires leadership, [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Tuskegee Airman Edward Gleed posing in front of a P-51D Mustang, Ramitelli, Italy, March 1945. Tuskegee Airmen, black servicemen of the U.S. Army Air Forces who trained at Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama during World War II. They constituted the first African American flying unit in the U.S. military.

On March 7, 1942, the first class of cadets graduated from Tuskegee Army Air Field to become the nation's first African American military pilots, now known as the Tuskegee Airmen. Following this ...

Tuskegee Airmen Essay. The Tuskegee Airmen were the first black pilots in WWII who were extremely talented and disciplined.1 These brave and courageous men were known to fight two wars: the war against the Power Axis in Germany and the war against extreme racism at home.2 The Tuskegee Airmen were youth who helped their county in more ways than ...

The Tuskegee Airmen were the first black military aviators in the U.S. Army Air Corps (AAC), a precursor of the U.S. Air Force. Trained at the Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama, they flew more ...

A Film Review of The Tuskegee Airmen. 2 pages / 928 words. The Tuskegee Airmen Film Review In 1941, on the United States Air Corps base in Tuskegee, Alabama, a group of young African American men created history as the first colored fighter pilots in American history. During a global war against racism, these young men experienced...

The "Spirit of Tuskegee" hangs from the ceiling at the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. The blue and yellow Stearman PT 13-D was used to train Black ...

The Tuskegee Airmen / t ʌ s ˈ k iː ɡ iː / are a group of African American military pilots (fighter and bomber) and airmen who fought in World War II.They formed the 332nd Fighter Group and the 477th Bombardment Group (Medium) of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF). The name also applies to the navigators, bombardiers, mechanics, instructors, crew chiefs, nurses, cooks, and other ...

Former Tuskegee Airman Roger Terry, pictured at age 87, c. 2009. In 1995, President Bill Clinton pardoned Terry, restored his rank to Second Lieutenant and refunded his $150. At the same time ...

The Tuskegee Airmen combatted racial discrimination and overcame limited opportunities by becoming one of the most highly regarded combat units of World War II. The Red Ball Express proved that they were fit for combat and were worthy of serving for the Allied troops by playing a leading role in the defeat of the Nazis. ... Related Essays on ...

Courtesy of Debby Greenberg '87. Gen. McGee's recent passing at the age of 102, fittingly on the Sunday before MLK Day, prompted me to reflect on what Black History Month means to me. When Carter Woodson founded Negro History Week nearly a century ago as its precursor, his intent was to promote learning and celebrate the achievements of ...

Yenwith Whitney(Tuskegee Airmen MIT Black History) Yenwith Whitney was a professor, a father, and a husband. This may seem ordinary, but only if you ignore one huge aspect of his life. He was a pilot, and a member of a group of heroes, called the Tuskegee Airmen.The Tuskegee Airmen were the first African American flying unit in the military.

Email your entry to: [email protected]. Essay contest winners will be announced on March 30, 2021. Prizes will be awarded to the 1st, 2nd and 3rd place winners in each grade category as follows: 1st place: An autographed print of "Tuskegee Tales" 2nd place: A RISE ABOVE hat 3rd place: A 99th Squadron Tuskegee Airmen patch.

Back during World War II, between the years of 1940 and 1945 there was approximately 909,000 African Americans that went and enlisted into the United... read full [Essay Sample] for free

Good Essays. 1869 Words. 8 Pages. Open Document. On July 19, 1941 the U.S. Air Force created a program in Alabama to train African Americans as fighter pilots (Tuskegee Airmen1). Basic flight training was done by the Tuskegee institute, a school founded by Booker T. Washington in 1881 (Tuskegee Airmen 1). Cadets would finish basic training at ...

September 12, 2019. Calling all students 4th through 12th grade! Submit your essay for the CAF Rise Above Squadron's essay contest saluting the Tuskegee Airmen Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP)! Deadline is February 6, 2023. Using the Six Guiding Principles (Aim High, Believe in Yourself, Use Your Brain, Be Ready to Go, Never Quit, Expect ...

Essay contest winners will be announced on March 15, 2024. Prizes will be awarded to the 1st, 2nd and 3rd place winners in each grade category as follows: 1st place: MA-Flight backpack black or sage. 2nd place: Mustang model kit of the P-51C "Tuskegee Airmen" 3rd place: Choice of aviator wings: TUSKEGEE AIRMEN or WASP

Essay, Pages 3 (559 words) Views. 17. The story of the Tuskegee Airmen is one of valor, determination, and triumph against all odds. As the first African American military aviators in the United States Armed Forces during World War II, these men not only faced the enemy in the skies but also the deeply entrenched racial prejudice back home. The ...

The Tuskegee Airmen by Brice Bowlds. Tuskegee Airmen Medium Bombardment Crew. The United States Air Corps had an age-old policy of not allowing Negroes into the Air Force. Before the 1930's, civil rights for colored people was not of national interest. The Air Force couldn't be compelled to open their ranks on even a segregated basis.

Tuskegee Airmen Essay. 948 Words4 Pages. The Tuskegee Airmen. The United States Air Corps had an age-old policy of not allowing Negroes into the Air Force. Before the 1930s, civil rights for colored people was not of national interest. The Air Force couldn't be compelled to be open their ranks on even a segregated basis.

A Film Review of the Tuskegee Airmen Essay In 1941, on the United States Air Corps base in Tuskegee, Alabama, a group of young African American men created history as the first colored fighter pilots in American history.

Tuskegee Airmen Essay. 856 Words4 Pages. In this essay, we will go over the timeline of WWII and the things that occurred while and when WWII was happening. The first thing I will be talking about is the Tuskegee Airmen. The Tuskegee Airmen were the first African American group that fought in WWII, they were bombers and pilots in the war.

In closing this essay will show what the Tuskegee airmen did in World War II and how they help end segregation in the armed services. The birth of the Tuskegee airmen was started by the war department due to pressure to create the first all-African American fighter squadron. The 99th pursuit squadron would be the answers to the war department ...

Tuskegee Airman Essay. The Tuskegee airman were a group of African American pilots who fought in the Second World War. They are well known in history due to the fact of their high success in missions and that they were the first squadron to be all Black.

Essay On Tuskegee Airmen. September 1, 1939, the start of World War II, regarded by many as the worst point in history. More than 85,000,000 people died in the years of 1939 to 1945. Adolf Hitler said something that sums up what the Germans were trying to accomplish during WWII, "Today Germany tomorrow the world.".