Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Literature › Romanticism in America

Romanticism in America

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on November 29, 2017 • ( 5 )

The French Revolution of 1789 marked a watershed for the future of Europe, a fact keenly discerned by writers on both sides of the Atlantic, such as Irving Babbitt and Matthew Arnold . Not only did that Revolution initiate the political ascendancy of the bourgeoisie, a struggle continued through the violent European revolutions of 1830 and 1848; but also its dimensions were so momentous, overturning the centuries-old economic edifice of feudalism and absolutism, as well as their sanction in classical Christian thought, that its imprint was indelibly impressed on all areas of life, economic, religious, philosophical, scientific, and literary.

The major characteristics of capitalist development in America during the nineteenth century were consonant with those in Europe. Henry Adams observed an “instinctive kinship” between the later nineteenth-century bourgeoisie of Paris and London and that of New England; for the latter, “England’s middle-class government was the ideal of human progress.” In both Europe and America, industrial capitalism, where business interests had been predominantly organized as individual enterprises or partnerships, began to be superseded in mid-century by the much more impersonal organization of finance capitalism, so called because of the monopolization of industry by huge investment banking empires. The new ruling class now comprised industrialists and investment bankers. Adams effectively captured the ruthless spirit of this transition: “The Trusts and Corporations stood for the larger part of the new power that had been created since 1840, and were obnoxious because of their vigorous and unscrupulous energy. They were revolutionary, troubling all the old conventions and values . . .They tore society to pieces and trampled it under foot.” In the 1880s John D.Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie became symbols of such monopoly through their respective enterprises in petroleum and steel. By the 1860s it was the railroads which represented the most powerful economic interest in America; the rapid expansion and incorporation of the railroad network in the following years paved the way for large corporations and centralized management in other industries such as steel. It is no accident that in Adams ’ autobiography the railroad becomes a subtle metaphor for the restructuring of society by industrial interests.

These developments were accompanied by a massive increase in population from about five million in 1800 to around a hundred million in 1914, as well as by a huge influx of immigration and, as in Europe, a large-scale movement of people from the countryside to the towns. By the late nineteenth century there had arisen a vast urban industrial landscape linked by railroad and telegraph, a metallic and concrete world in which the rhythms of rural life, the seasonal work cycles, the links between successive generations, the sense of identity between individual and community, and the strength of family ties were all severely shaken. The greater part of individual identity, as Ferdinand Tonnies suggests, was endowed by a person’s social role. Equally consequent upon this increasing division of labor was the disintegration of the individual’s psychic unity into a one-dimensional orientation toward utilitarian and rational practice at the expense of what many writers called sensibility. All of these features – finance capitalism, the railroad, centralization of management and authority, a mechanical concept of time (as money), and the displacement of Gemeinschaft by Gesellschaft – formed the conditions to which American Romantics responded.

Like Europe, America had its fair share of economic liberals such as Nassau Senior, as well as its propagators of the myth of the “self-made man,” a myth through whose core ran the Puritan Protestant ethic of hard work and thrift. As stated above, the notion of self-creation through work or labor lies at the center of a nexus of bourgeois ideals which, as Engels , Max Weber , and others have argued, are underpinned by a devotion to the rational organization of society and in particular the rational accumulation of capital. In America, economic liberalism (which, however, was constrained by America’s protectionist policy since 1816 and the emergence of corporations and monopolies) was somewhat tempered by the “gospel of wealth,” which was but one of numerous attempts to argue the commensurability of capitalism and Christianity. This doctrine, elaborated for example in Carnegie ’s The Gospel of Wealth (1901), decreed that possession of wealth brought along with it a Christian responsibility to donate to the good of the community. Many churches in fact formulated their doctrines so as to harmonize with contemporary economic practice and material conditions. One of these was the Unitarian Church, whose liberalism facilitated the influx into America of European Romantic ideas.

Romanticism in America flowered somewhat later than in Europe, embroiled as the new nation was in the struggle for self-definition in political, economic, and religious terms. It was American independence from British rule, achieved in 1776, that opened the path to examining national identity, the development of a distinctly American literary tradition in the light of Romantically reconceived visions of the self and nature. The major American Romantics included Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman , Nathaniel Hawthorne , Margaret Fuller , Henry David Thoreau , and Herman Melville . While some of these writers were influenced by European Romantics and philosophers, nearly all of them were inspired by a nationalistic concern to develop an indigenous cultural tradition and a distinctly American literature. Indeed, they helped to define – at a far deeper and more intelligent level than the crude definitions offered by politicians since then until the present day – the very concept of American national identity. Like the European Romantics, these American writers reacted against what they perceived to be the mechanistic and utilitarian tenor of Enlightenment thinking and the industrial, urbanized world governed by the ethics and ideals of bourgeois commercialism. They sought to redeem the ideas of spirit, nature, and the richness of the human self within a specifically American context.

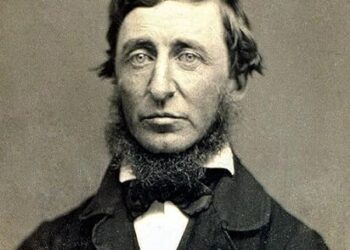

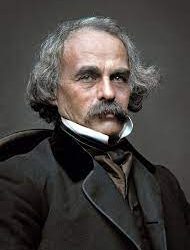

It was Emerson who laid the foundations of American Romanticism . Utilizing the ideas of Wordsworth , Coleridge , and Thomas Carlyle , he developed organicist ideas of nature, language, and imagination, and called for American writers to depart from the strict genres and formal hierarchies of European literary tradition and to forge their own modes of expression. Both Emerson and Walt Whitman referred to America as a “poem” which needed to be written. In the preface to his Leaves of Grass (1855), Whitman saw himself as writing “the great psalm of the republic,” and in a subsequent preface identified the expression of individual identity with national identity. Like Emerson, he reacted against the strictures of genre and form and wrote in a freer form using colloquial speech, or what Whitman called “the dialect of common sense,” intended to convey the vastness of the American spirit. He saw the “genius” of the United States as residing in the common people, and thought that the redemption of America from its rotten commercialism lay in the realization of its authentic self. Whitman ’s Song of Myself begins with the line “I celebrate myself.” But the narrative “I” that controls the movement of this poem is symbolic (“In all people I see myself,” l. 401). Emphasizing a common humanity, Whitman locates this human nature in both soul and body, spurning didactic aims and boldly celebrating the divine in all dimensions of his humanity, and assuming indifference to conventional morality, as in his questioning “What blurt is it about virtue and about vice?” (l. 468). Whitman moves toward a total acceptance of humanity, free from the artifice of conventional perception, and the false imposition of coherence: “Do I contradict myself? / Very well then . . . I contradict myself; / I am large . . . I contain multitudes” (ll. 1314–1316). Whitman saw the human personality as integrating and accommodating all kinds of development, scientific, artistic, religious, and economic. Another major figure influenced by Emerson, as well as by Thomas Carlyle , was Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862). In his most famous work, Walden (1854), based on his sojourn at Emerson’s property at Walden pond, he advocated a life free of social artifice, routine, and consumerism, simplified in its needs, devoted to nature and art, imaginatively exploring the depths of the self, and developing an authentic language. Thoreau’s highly Romantic and eccentric vision was also expressed in his views of the rights of the individual and of the need to resist oppression; he was a fervent abolitionist, and his essay Resistance to Civil Government (1849; later entitled Civil Disobedience ) influenced Mohandas K. Gandhi ’s struggle for Indian independence from British rule as well as the American civil rights movement led by Martin Luther King, Jr . Margaret Fuller (1810–1850) also voiced fervent opposition to what she saw as a society soiled by material greed, crime, and the perpetuation of slavery. Influenced at various times by Goethe , Carlyle , Mary Wollstonecraft , and George Sand , and a friend of Emerson’s, she edited the transcendentalists’ journal the Dial from 1840 to 1842, and published a notable feminist work, Woman in the Nineteenth Century (1844), in which she argued that the development of men and women cannot occur in mutual independence, there being no wholly masculine man, or purely feminine woman. She was distinctive in making gender an issue, and this text can be read as an effort to make Emersonian self-reliance an option for women. Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1864) drew upon Emerson’s theories, Enlightenment philosophy, and Coleridge ’s views on imagination to define the genre of romance fiction as a locus where the real and the imaginary intersect and influence each other, in a unified vision. For Hawthorne, recognition of textual history and the history of American institutions is just an integral element of such a vision as is nature. Both Hawthorne and his friend and admirer Herman Melville reacted, like the other American Romantics, against the mechanism and commercialism at the core of American life. Striving to attain the passion and originality to develop a national literature, they yet recognized that the modern fragmented world defied the attempts of romance and imagination to achieve a harmonious and comprehensive vision of life.

Source: A History of Literary Criticism : From Plato to the Present Editor(s): M. A. R. Habib

Share this:

Categories: Literature

Tags: Andrew Carnegie , Civil Disobedience , Ferdinand Tonnies , Gemeinschaft , George Sand , Gesellschaft , Goethe , Henry Adams , Henry David Thoreau , Herman Melville , Irving Babbitt , John D.Rockefeller , Leaves of Grass , Literary Criticism , Literary Theory , Margaret Fuller , Nathaniel Hawthorne , Poetry , Ralph Waldo Emerson , Romanticism , Romanticism in America , Samuel Taylor Coleridge , Song of Myself , The Dial , The Gospel of Wealth , Thomas Carlyle , Walden or Life in the Woods , Walt Whitman , Woman in the Nineteenth Century , Wordsworth

Related Articles

- Literary Criticism of Ralph Waldo Emerson – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Literary Criticism of Edgar Allan Poe – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Literary Criticism and Theory in the Twentieth Century – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Literary Criticism and Theory in the Twentieth Century | Literary Theory and Criticism

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

ENGL405: The American Renaissance

Romanticism in america.

To begin, read this article about the influence of European Romanticism on American authors.

The mid-nineteenth century often has been considered an "American Renaissance" due to the number and quality of literary works produced.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Identify the major works of literature produced during the mid-nineteenth century "American Renaissance"

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The decades before the Civil War saw a number of American literary masterpieces.

- This period, now referred to as the "American Renaissance" of literature, often has been identified with American romanticism and transcendentalism.

- Literary nationalists at this time were calling for a movement that would develop a unique American literary style to distinguish American literature from British literature.

- Authors such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Henry David Thoreau, and Walt Whitman wrote their best and most famous works during this period.

- In recent years, female authors such as Emily Dickinson and Harriet Beecher Stowe have been added to the list of great authors from the period.

- nationalism : The idea of supporting one's country and culture.

- transcendentalism : A movement of writers and philosophers in New England in the nineteenth century whose members were loosely bound together by adherence to an idealistic system of thought based on the belief in the essential supremacy of insight over logic and experience for the revelation of the deepest truths.

- American Romanticism : An artistic, literary, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe toward the end of the eighteenth century; in most areas it was at its peak in the approximate period from 1800 to 1840.

The American Renaissance

During the mid-nineteenth century, many American literary masterpieces were produced. Sometimes called the "American Renaissance" (a term coined by the scholar F.O. Matthiessen), this period encompasses (approximately) the 1820s to the dawn of the Civil War, and it has been closely identified with American romanticism and transcendentalism.

Often considered a movement centered in New England, the American Renaissance was inspired in part by a new focus on humanism as a way to move from Calvinism. Literary nationalists at this time were calling for a movement that would develop a unique American literary style to distinguish American literature from British literature. The American Renaissance is characterized by renewed national self-confidence and a feeling that the United States was the heir to Greek democracy, Roman law, and Renaissance humanism. The American preoccupation with national identity (or nationalism) in this period was expressed by modernism, technology, and academic classicism, a major facet of which was literature.

Protestantism shaped the views of the vast majority of Americans in the antebellum years. Alongside the religious fervor during this time, transcendentalists advocated a more direct knowledge of the self and an emphasis on individualism. The writers and thinkers devoted to transcendentalism, as well as the reactions against it, created a trove of writings, an outpouring that became what has now been termed the "American Renaissance".

Major Literary Works

Transcendentalist writers.

Many writers were drawn to transcendentalism, and they started to express its ideas through new stories, poems, essays, and articles. The ideas of transcendentalism were able to permeate American thought and culture through a prolific print culture, which allowed the wide dissemination of magazines and journals. Ralph Waldo Emerson emerged as the leading figure of this movement. In 1836, he published "Nature", an essay arguing that humans can find their true spirituality in nature, not in the everyday bustling working world of Jacksonian democracy and industrial transformation. In 1841, Emerson published his essay "Self-Reliance", which urges readers to think for themselves and reject the mass conformity and mediocrity taking root in American life.

Emerson's ideas struck a chord with a class of literate adults who also were dissatisfied with mainstream American life and searching for greater spiritual meaning. Among those attracted to Emerson's ideas was his friend Henry David Thoreau, whom Emerson encouraged to write about his own ideas. In 1849, Emerson published his lecture "Civil Disobedience" and urged readers to refuse to support a government that was immoral. In 1854, he published Walden; or, Life in the Woods, a book about the two years he spent in a small cabin on Walden Pond near Concord, Massachusetts.

Walt Whitman also added to the transcendentalist movement, most notably with his 1855 publication of twelve poems, entitled Leaves of Grass, which celebrated the subjective experience of the individual. One of the poems, "Song of Myself", emphasized individualism, which for Whitman, was a goal achieved by uniting the individual with all other people through a transcendent bond.

Walt Whitman, American poet and essayist : Walt Whitman was a highly influential American writer. His American epic, Leaves of Grass, celebrates the common person.

Other Writers

Some critics took issue with transcendentalism's emphasis on rampant individualism by pointing out the destructive consequences of compulsive human behavior. Herman Melville's novel Moby-Dick; or, The Whale emphasized the perils of individual obsession by telling the tale of Captain Ahab's single-minded quest to kill a white whale, Moby Dick, which had destroyed Ahab's original ship and caused him to lose one of his legs. Edgar Allan Poe, a popular author, critic, and poet, decried, "the so-called poetry of the so-called transcendentalists". These American writers who questioned transcendentalism illustrate the underlying tension between individualism and conformity in American life. Other notable works from this time period include Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter (1850) and The House of the Seven Gables (1851).

Nathaniel Hawthorne, American novelist : Hawthorne was among the foremost American writers of the era, achieving critical and popular success with novels such as The Scarlet Letter and The House of the Seven Gables.

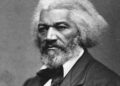

As often happens, historians emphasize the works produced by white men during the American Renaissance, but many African Americans and women produced great literary works, too. Emily Dickinson began writing poetry in the 1830s, and Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852) rose to a prominent reputation in the late 1970s. African-American literature during this time, including slave narratives by such writers as Frederick Douglass and early novels by William Wells Brown, has gained increasing recognition as well.

American Romanticism emphasized emotion, individualism, and personality over rationalism and the constraints of religion.

Summarize the central commitments of American Romanticism

- Romanticism, which reached American from Europe in the early 19th century, appealed to Americans as it emphasized an emotional, individual relationship with God as opposed to the strict Calvinism of previous generations.

- Romanticism emphasized emotion over reason and individual decision-making over the constraints of tradition.

- The Romantic movement was closely related to New England transcendentalism, which portrayed a less restrictive relationship between God and the universe.

- Romanticism gave rise to a new genre of literature in which intense, private sentiment was portrayed by characters who showed sensitivity and excitement, as well as a greater exercise of free choice in their lives.

- The Romantic movement also saw a rise in women authors and readers. Prominent Romantic writers include Washington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper, Edgar Allan Poe, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, and Herman Melville.

- transcendentalism : A movement of writers and philosophers in New England in the 19th century who were loosely bound together by adherence to an idealistic system of thought based on the belief in the essential supremacy of insight over logic and experience for the revelation of the deepest truths.

- rationalism : The theory that the basis of knowledge is reason rather than experience or divine revelation.

- Calvinism : The Christian denomination which places emphasis on the sovereignty of God and distinctively includes the doctrine of predestination (that a special few are predetermined for salvation, while others cannot attain it).

American Romanticism

The European Romantic movement reached America during the early 19 th century. Like the Europeans, the American Romantics demonstrated a high level of moral enthusiasm, commitment to individualism and the unfolding of the self, an emphasis on intuitive perception, and the assumption that the natural world was inherently good while human society was filled with corruption.

Romanticism became popular in American politics, philosophy, and art. The movement appealed to the revolutionary spirit of America as well as to those longing to break free of the strict religious traditions of the early settlement period. The Romantics rejected rationalism and religious intellect. It appealed especially to opponents of Calvinism, a Protestant sect that believes the destiny of each individual is preordained by God.

Relation to Trascendentalism

The Romantic movement gave rise to New England transcendentalism, which portrayed a less restrictive relationship between God and the universe. The new philosophy presented the individual with a more personal relationship with God. Transcendentalism and Romanticism appealed to Americans in a similar fashion; both privileged feeling over reason and individual freedom of expression over the restraints of tradition and custom. Romanticism often involved a rapturous response to nature and promised a new blossoming of American culture.

Romantic Themes

The Romantic movement in America was widely popular and influenced American writers such as James Fenimore Cooper and Washington Irving. Novels, short stories, and poems replaced the sermons and manifestos of earlier days. Romantic literature was personal and intense; it portrayed more emotion than ever seen in neoclassical literature.

America's preoccupation with freedom became a great source of motivation for Romantic writers, as many were delighted in free expression and emotion without fear of ridicule and controversy. They also put more effort into the psychological development of their characters, and the main characters typically displayed extremes of sensitivity and excitement. The works of the Romantic Era also differed from preceding works in that they spoke to a wider audience, partly reflecting the greater distribution of books as costs came down and literacy rose during the period. The Romantic period also saw an increase in female authors and readers.

Prominent Romantic Writers

Romantic poetry in the United States can be seen as early as 1818 with William Cullen Bryant's "To a Waterfowl". American Romantic Gothic literature made an early appearance with Washington Irving's The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1820) and Rip Van Winkle (1819), followed from 1823 onwards by the Leatherstocking Tales of James Fenimore Cooper. In his popular novel Last of the Mohicans, Cooper expressed romantic ideals about the relationship between men and nature. These works had an emphasis on heroic simplicity and fervent landscape descriptions of an already-exotic mythicized frontier peopled by "noble savages". Edgar Allan Poe's tales of the macabre and his balladic poetry were more influential in France than at home, but the romantic American novel developed fully with the atmosphere and melodrama of Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter (1850).

Later transcendentalist writers such as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson still show elements of its influence and imagination, as does the romantic realism of Walt Whitman. Emerson, a leading transcendentalist writer, was highly influenced by romanticism, especially after meeting leading figures in the European romantic movement in the 1830s. He is best known for his romantic-influenced essays such as "Nature" (1836) and "Self-Reliance" (1841). The poetry of Emily Dickinson – nearly unread in her own time – and Herman Melville's novel Moby-Dick can be taken as epitomes of American Romantic literature. By the 1880s, however, psychological and social realism were competing with Romanticism in the novel.

Washington Irving, American Writer and Historian : Washington Irving's writings, such as the Legends of Rip Van Winkle and Sleepy Hollow, contained romantic elements such as the celebration of nature and romantic virtues such as simplicity.

James Fenimore Cooper, American novelist and political writer : In his popular novels, such as Last of the Mohicans, James Fenimore Cooper expressed romantic ideals about the relationship between men and nature.

During the middle of the nineteenth century, newspapers went from serving as mouthpieces of political parties to addressing broader public interests.

Identify the distinctive trends in newspaper journalism that emerged over the course of the eighteenth century

- In the early nineteenth century, most newspapers were controlled by political parties and served to support those parties' ideas and candidates. Journalism soon changed to address broader public interests, covering new topics that were important and relevant to everyone instead of a select few.

- Many of the changes that came with this shift brought about new features of journalism that remain important today, such as the editorial page, personal interviews, business news, and foreign-news correspondents.

- Advances in technology, such as the telegraph and railroad, made it possible to receive and report on news faster than ever before.

- Penny press newspapers began to publish sensational human-interest stories and relied on advertising, instead of subscriptions, to sell issues.

- Some reform movements published their own newspapers, and abolitionist papers in particular were met with a great deal of controversy as they reported on the evils of slavery.

- penny press : Cheap, tabloid-style newspapers produced in the United States in the mid-nineteenth century.

- editorial page : A newspaper section on which the leading article (United Kingdom), or leader (United States), is an opinion piece written by the senior editorial staff or publisher of a newspaper or magazine.

- William Lloyd Garrison : Prominent American abolitionist, journalist, and social reformer (December 10, 1805–May 24, 1879).

Introduction

During the middle of the nineteenth century, newspapers changed from being mouthpieces of political parties to serving a broader public appeal. Many of the changes that came with this shift brought about new features of journalism that remain important today, such as the editorial page, personal interviews, business news, and foreign-news correspondents.

Many newspapers in the early part of the nineteenth century were published by political parties and served as political mouthpieces for the beliefs and candidates of those parties. Over the next few decades, however, the influence of these "administrative organs" began to fade away. Newspapers and their editors began to show greater personal and editorial influence as they realized the broader appeal of human-interest stories.

November 16, 1864 edition of the New York Tribune : Some penny papers were closely associated with political parties; the New York Tribune backed the Whigs and later the Republicans.

Birth of Editorial Comment

The editorial voice of each newspaper grew more distinct and important, and the editorial page began to assume something of its modern form. The editorial signed with a pseudonym gradually died, but unsigned editorial comment and leading articles did not become established features until after 1814, when Nathan Hale made them characteristic of the newly established Boston Daily Advertiser. From then on, these features grew in importance until they became the most vital part of the greater papers.

News Becomes Widespread

Nearly every county and large town sponsored at least one weekly newspaper. Politics were of major interest, with the editor-owner typically deeply involved in local party organizations. However, the papers also contained local news, and presented literary columns and book excerpts that catered to an emerging middle class and literate audience. A typical rural newspaper provided its readers with a substantial source of national and international news and political commentary, typically reprinted from metropolitan newspapers. In addition, the major metropolitan dailies often prepared weekly editions for circulation to the countryside.

Systems of more rapid news-gathering and distribution quickly appeared. The telegraph, put to successful use during the Mexican-American War, led to numerous far-reaching results in journalism. Its greatest effect was to decentralize the press by rendering the inland papers (in such cities as Chicago, Louisville, Cincinnati, and New Orleans) independent of those in Washington and New York. The news field was immeasurably broadened; news style was improved, and the introduction of interviews, with their dialogue and direct quotations, imparted papers with an ease and freshness. There was a notable improvement in the reporting of business, markets, and finance. A foreign-news service was developed that reached the highest standard yet attained in American journalism in terms of intelligence and general excellence.

This idea of the newspaper for its own sake, the unprecedented aggressiveness in news-gathering, and the blatant methods by which the cheap papers were popularized, aroused the antagonism of the older papers, but created a competition that could not be ignored. The growth of these newer papers meant the development of great staffs of workers that exceeded in numbers anything dreamed of in the preceding period. Indeed, the years between 1840 and 1860 saw the beginnings of the scope, complexity, and excellence of our modern journalism.

The Penny Press

In the early 1800s, newspapers had catered largely to the elite and took two forms: mercantile sheets that were intended for the business community and contained ship schedules, wholesale product prices, advertisements and some stale foreign news; and political newspapers that were controlled by political parties or their editors as a means of sharing their views with elite stakeholders. Journalists reported the party line and editorialized in favor of party positions.

Appealing to the Commoner

Some editors believed in a public who would not buy a serious paper at any price; they believed the common person had a vast and indiscriminate curiosity better satisfied with gossip than discussion and with sensation rather than fact, and who could be reached through their appetites and passions. To this end, the "penny press" papers, which sold for one cent per copy, were introduced in the 1830s. Penny press newspapers became an important form of popular entertainment in the mid-nineteenth century, taking the form of cheap, tabloid-style papers. As the East Coast's middle and working classes grew, so did the new public's desire for news, and penny papers emerged as a cheap source that covered crime, tragedy, adventure, and gossip. They depended much more on advertising than on high priced subscriptions, and they often aimed their articles at broad public interests instead of at perceived upper-class tastes.

Mass production of inexpensive newspapers became possible when technology shifted from handcrafted to steam-powered printing. The penny paper was famous for costing one cent, unlike its competitors, which could cost as much as six cents. This cheap newspaper was revolutionary because it made the news available to lower-class citizens for a reasonable price. To be profitable at such a low price, these papers needed large circulations and feature advertisements; they needed to target a public who had not been accustomed to buying papers and who would be attracted by news of the street, shop, and factory.

The Sun and the Herald

Benjamin Day, an important and innovative publisher of penny newspapers, introduced a new type of sensationalism: a reliance on human-interest stories. He emphasized common people as they were reflected in the political, educational, and social life of the day. Day also introduced a new way of selling papers, known as the London Plan, in which newsboys hawked their newspapers on the streets. Penny papers hired reporters and correspondents to seek out and write the news, and the news began to sound more journalistic than editorial. Reporters were assigned to beats and were involved in the conduct of local interaction.

The newspaper, The New York Sun : Benjamin Day's newspaper, The New York Sun.

James Gordon Bennett's newspaper The New York Herald added another dimension to penny press papers that is now common in journalistic practice. Whereas newspapers had generally relied on documents as sources, Bennett introduced the practices of observation and interviewing to provide stories with more vivid details. Bennett is known for redefining the concept of news, reorganizing the news business, and introducing newspaper competition. The New York Herald was financially independent of politicians because it had large numbers of advertisers.

Abolition: A Thorny Issue

In a period of widespread unrest and social change, many specialized forms of journalism sprang up, focusing on religious, educational, agricultural, and commercial themes. During this time, workingmen were questioning the justice of existing economic systems and raising a new labor issues; Unitarianism and transcendentalism were creating and expressing new spiritual values; temperance, prohibition, and the political status of women were being discussed; and abolitionists were growing more vocal, becoming the subject of controversy most critically related to journalism. Some reform movements published their own newspapers, and abolitionist papers in particular were met with a great deal of controversy as they rallied against slavery.

The abolitionist press, which began with The Emancipator of 1820 and had its chief representative in William Lloyd Garrison 's Liberator , forced the slavery question upon the newspapers, and a struggle for the freedom of the press ensued. Many abolitionist papers were excluded from the mails, and their circulation was forcibly prevented in the South. In Boston, New York, Baltimore, Cincinnati, and elsewhere, editors were assaulted, and offices were attacked and destroyed.

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

American Romanticism, Essay Example

Pages: 3

Words: 868

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

American Romanticism (or “American Renaissance”) relates to several decades before the Civil War (about 1830-1840 to 1865). American Romantic tradition shared many characteristics with European art, due to its close connection with British Romanticism, namely British poetry (Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Keats, Shelley).

The grounding principles of European Romanticism opposed to the doctrine of reason dominating the preceding Age of Enlightenment and rigors of Classicism. Romantic art focuses on personality and its opposition to society. McFarland Pennell (2006) concludes that “Romantics emphasized self-cultivation, a continual process of inner development, which allowed and individual to reach…potential and … recognize the divinity within” (p.2).

Disappointment in civilization, social and scientific progress, spiritual devastation leads to reappraisal of values. Predicted by the enlighteners new society did not prove the expected results. Therefore, future turned to be independent of the reason. It explicates the pessimism, desperation, hopelessness inherent in many romantic works. On the other hand, the hero challenges this world on his way to the ideal, to the absolute. The spirit of the romantic hero is a complex person full of contradictions. The specific American components of the romanticism of American writers included particular awareness of wild nature, which manifested the urge of exploration of new territories in westward expansion.

The distinctive trait of American Romanticism is the flourishing of literature. The constellation of prominent writers (Bryant, Irving, Cooper, Poe, Hawthorne, Melville, Whittier, Whitman, Longfellow, Lowell and Dickinson) emerges in this period. Their works represent various themes (moral qualities, slave abolition, pursuits of romantic absolute) and forms (novels, short stories, free verse poetry). The writers consider theoretical background of their creations.

The Romantic period in American literature marks a turning point for the development of national self-consciousness. Besides the overall excitement over human possibilities, the literary outburst enabled the consideration of American literature separately of “paternal” British tradition. They created artworks which possessed distinctive American character. The artist expressed their response to keen interest of European Romanticists to folklore, to national background enclosed in myths and legends.

Romantic writers supposed poetry the embodiment of bountiful imagination. Meditation of the natural world comes into poetry as one of major themes. Unlike American Romantic prose, aimed at diversion from European writing, poetry experienced gradual transformations. The Fireside poets Longfellow, Whittier, Holmes, and Lowell applied traditional techniques of English metre and themes, involving national settings and subjects. The publication of Leaves of Grass by W. Whitman revealed the romantic aspiration for escape from the formalistic requirements chaining poetry. His free verse based on cadence spoke the nation through thought-provoking precise language.

The novelists of the period praised supernatural phenomena, imagination world. The themes of the past, of exotic gave vent to the genre of Gothic novel. The disappointment in progress consequences and helplessness of reason gave way to the conflicts of good and evil, of psychological subjects, like guilt, madness. The stories of E. A. Poe often deal with these mysterious themes. His sensitive, lonely, and often mentally sick protagonist seeks Ideal.

James Fenimore Coopers was one of the first writers to describe American settings in his novels. Besides, nature’s beauty was perceived as a way of spiritual development, unlike artificial civilization depriving the individual of untouched nature. Therefore, the artists do not rely on the progress any more.

American Romanticism is also associated with the philosophical, literary movement of “transcendentalism”. The founders and followers of “transcendentalism” expressed their views in philosophical essays. R. W. Emerson, H. D. Thoreau, and M. Fuller sought spiritual values within individual. They considered the natural world a sign for inner spirit. They revolted against the government and its institutions which attempted to assume control over the individual. Though Ralf Waldo Emerson considered himself a poet, he is known first as prolific thinker on various philosophical, social themes. In 1836, Emerson’s essays in nature studies were published in Nature. The book explicated the foundations of Transcendentalist philosophy, which justified the connection of nonhuman nature world (Not-Me) and spiritual human world (Me).

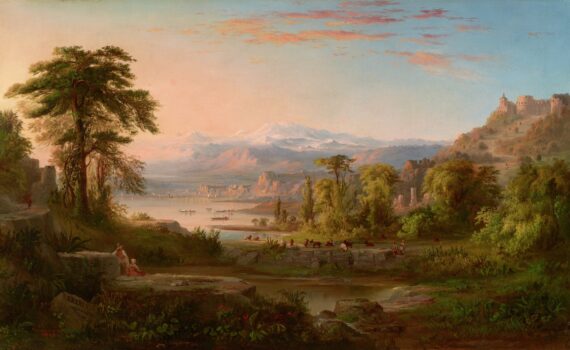

Unlike totally investigated American Romantic literature, Romantic Paintings have not been exhaustively studied. The first American school of landscape painting was Hudson River School (1835 -1870). They portrayed sights of Hudson River Valley. The first leader of the group was Thomas Cole. According to Miller and Soby (1969), Cole “brought to landscape decided imaginative power”, “passionate moral force which made him the acknowledged leader and prophet of nature Romanticism” (p.16). Other famous representatives of the school are George Caleb Bingham, Frederic Edwin Church, Asher B. Durand, John Frederic Kensett, Thomas Moran, Albert Bierstadt, George Inness, and Martin Johnson Heade. They valued the neoclassical principles of proportion, decorum and order. The canvases are grotesque, picturesque with some tendency to strangeness. Romantic figure painters, as John Quidor inspired by literary works, was unknown to his contemporaries.

The Civil War marked the end of the pioneer era in American painting; “artists continued to draw inspiration from local scene, in both landscape and figure painting, but they no longer received so strong a metaphysical impetus from the newness, wildness and size of their county as had the earlier Romantics” (Miller & Soby, 1969, p.25).

McFarland Pennel, M. (2006). Masterpieces of American Romantic Literature . Wesport ,CT: Greenwood Press. Print.

Miller D. C., & Soby T. J. (1969). Romantic Paintings in America . New York: Arno Press. Print.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Key Points in Pandemic Planning, Essay Example

Issues That Affect Health Care Delivery, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

109 Introduction to The Romantic Era

The European Romantic movement reached America during the early 19th century. Like the Europeans, the American Romantics demonstrated a high level of moral enthusiasm, commitment to individualism and the unfolding of the self, an emphasis on intuitive perception, and the assumption that the natural world was inherently good while human society was filled with corruption.

Romanticism became popular in American politics, philosophy, and art. The movement appealed to the revolutionary spirit of America as well as to those longing to break free of the strict religious traditions of the early settlement period. The Romantics rejected rationalism and religious intellect. It appealed especially to opponents of Calvinism, a Protestant sect that believes the destiny of each individual is preordained by God.

Relation to Transcendentalism

The Romantic movement gave rise to New England transcendentalism, which portrayed a less restrictive relationship between God and the universe. The new philosophy presented the individual with a more personal relationship with God. Transcendentalism and Romanticism appealed to Americans in a similar fashion; both privileged feeling over reason and individual freedom of expression over the restraints of tradition and custom. Romanticism often involved a rapturous response to nature and promised a new blossoming of American culture.

Romantic Themes

The Romantic movement in America was widely popular and influenced American writers such as James Fenimore Cooper and Washington Irving. Novels, short stories, and poems replaced the sermons and manifestos of earlier days. Romantic literature was personal and intense; it portrayed more emotion than ever seen in neoclassical literature.

America’s preoccupation with freedom became a great source of motivation for Romantic writers, as many were delighted in free expression and emotion without fear of ridicule and controversy. They also put more effort into the psychological development of their characters, and the main characters typically displayed extremes of sensitivity and excitement. The works of the Romantic Era also differed from preceding works in that they spoke to a wider audience, partly reflecting the greater distribution of books as costs came down and literacy rose during the period. The Romantic period also saw an increase in female authors and readers.

Prominent Romantic Writers

Romantic poetry in the United States can be seen as early as 1818 with William Cullen Bryant’s “To a Waterfowl”. American Romantic Gothic literature made an early appearance with Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1820) and Rip Van Winkle (1819), followed from 1823 onwards by the Leatherstocking Tales of James Fenimore Cooper. In his popular novel Last of the Mohicans, Cooper expressed romantic ideals about the relationship between men and nature. These works had an emphasis on heroic simplicity and fervent landscape descriptions of an already-exotic mythicized frontier peopled by “noble savages”. Edgar Allan Poe’s tales of the macabre and his balladic poetry were more influential in France than at home, but the romantic American novel developed fully with the atmosphere and melodrama of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter (1850).

Later transcendentalist writers such as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson still show elements of its influence and imagination, as does the romantic realism of Walt Whitman. Emerson, a leading transcendentalist writer, was highly influenced by romanticism, especially after meeting leading figures in the European romantic movement in the 1830s. He is best known for his romantic-influenced essays such as “Nature” (1836) and “Self-Reliance” (1841). The poetry of Emily Dickinson—nearly unread in her own time—and Herman Melville’s novel Moby-Dick can be taken as epitomes of American Romantic literature. By the 1880s, however, psychological and social realism were competing with Romanticism in the novel.

Boundless US History , Lumen Learning, CC-BY

Introduction to The Romantic Era Copyright © 2019 by Jenifer Kurtz is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Romanticism in the United States

Romanticism in the United States took up themes of nature and spirituality in uniquely American ways.

c. 1800–1865 C.E.

videos + essays

We're adding new content all the time!

A dream of Italy: Black artists and travel in the nineteenth century

Created as the Civil War was coming to an end but at a time when all Americans were not yet equal citizens, this painting invokes an idealized landscape, with references to both past and present.

Science, religion, and politics, Church’s Cotopaxi

The natural world and political metaphor, Church's Cotopaxi

Frederic Edwin Church, The Iceberg

Revisiting a frozen sea, memory and science in the 19th century

Thomas Moran, Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone

The painting that inspired a National Park

Peter Frederick Rothermel, De Soto Raising the Cross on the Banks of the Mississippi

Picturing Spanish conquest in an era of U.S. expansion

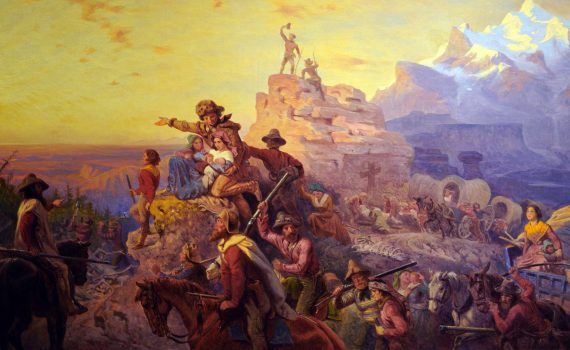

Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze, Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way

Daniel Boone, Moses, and the western frontier: creating an American mythology

Thomas Cole, The Architect’s Dream

Cole, the great American landscape painter looks across the vast history of Western architecture

Albert Bierstadt, Hetch Hetchy Valley, California

Captured here in paint, this grand Californian landscape would soon disappear under water.

Thomas Cole, The Hunter’s Return

Cole feared for the American landscape as his country expanded westward.

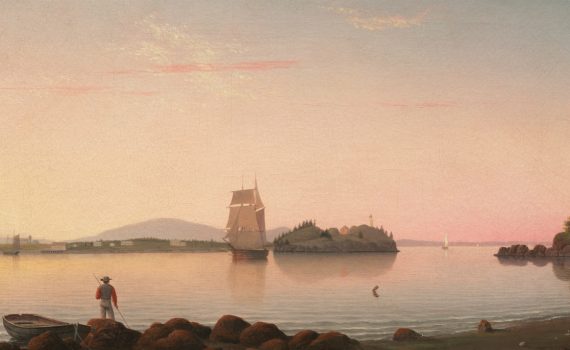

Fitz Henry Lane, Owl’s Head, Penobscot Bay, Maine

“Luminism” sounds like a subject at Hogwarts, but it actually describes landscape paintings like this one.

Thomas Cole, Expulsion from the Garden of Eden

Adam and Eve have just been evicted from Paradise, and the grass was definitely greener on the other side.

Washington Allston, Elijah in the Desert

Can we call a landscape painting “emo”? This brooding, melancholy canvas definitely tempts us to.

Selected Contributors

Maggie Adler

Barbara Bassett

Peter John Brownlee

Dr. Beth Harris

Farisa Khalid

Dr. Anna O. Marley

Erin Monroe

Dr. Lawrence W. Nichols

Carol Wilson

Dr. Bryan Zygmont

Dr. Steven Zucker

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

- Romanticism

Théodore Gericault

Evening: Landscape with an Aqueduct

Alfred Dedreux (1810–1860) as a Child

The Start of the Race of the Riderless Horses

Horace Vernet

Jean-Louis-André-Théodore Gericault (1791–1824)

Inundated Ruins of a Monastery

Karl Blechen

Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop's Grounds

John Constable

Eugène Delacroix

Royal Tiger

Stormy Coast Scene after a Shipwreck

French Painter

Mother and Child by the Sea

Johan Christian Dahl

The Natchez

Wanderer in the Storm

Julius von Leypold

The Abduction of Rebecca

Jewish Woman of Algiers Seated on the Ground

Théodore Chassériau

The Virgin Adoring the Host

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres

Ovid among the Scythians

Kathryn Calley Galitz Department of European Paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2004

Romanticism, first defined as an aesthetic in literary criticism around 1800, gained momentum as an artistic movement in France and Britain in the early decades of the nineteenth century and flourished until mid-century. With its emphasis on the imagination and emotion, Romanticism emerged as a response to the disillusionment with the Enlightenment values of reason and order in the aftermath of the French Revolution of 1789. Though often posited in opposition to Neoclassicism , early Romanticism was shaped largely by artists trained in Jacques Louis David’s studio, including Baron Antoine Jean Gros, Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, and Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. This blurring of stylistic boundaries is best expressed in Ingres’ Apotheosis of Homer and Eugène Delacroix’s Death of Sardanapalus (both Museé du Louvre, Paris), which polarized the public at the Salon of 1827 in Paris. While Ingres’ work seemingly embodied the ordered classicism of David in contrast to the disorder and tumult of Delacroix, in fact both works draw from the Davidian tradition but each ultimately subverts that model, asserting the originality of the artist—a central notion of Romanticism.

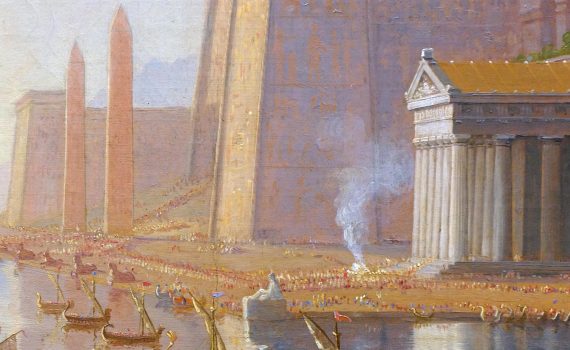

In Romantic art, nature—with its uncontrollable power, unpredictability, and potential for cataclysmic extremes—offered an alternative to the ordered world of Enlightenment thought. The violent and terrifying images of nature conjured by Romantic artists recall the eighteenth-century aesthetic of the Sublime. As articulated by the British statesman Edmund Burke in a 1757 treatise and echoed by the French philosopher Denis Diderot a decade later, “all that stuns the soul, all that imprints a feeling of terror, leads to the sublime.” In French and British painting of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the recurrence of images of shipwrecks ( 2003.42.56 ) and other representations of man’s struggle against the awesome power of nature manifest this sensibility. Scenes of shipwrecks culminated in 1819 with Théodore Gericault’s strikingly original Raft of the Medusa (Louvre), based on a contemporary event. In its horrifying explicitness, emotional intensity, and conspicuous lack of a hero, The Raft of the Medusa became an icon of the emerging Romantic style. Similarly, J. M. W. Turner’s 1812 depiction of Hannibal and his army crossing the Alps (Tate, London), in which the general and his troops are dwarfed by the overwhelming scale of the landscape and engulfed in the swirling vortex of snow, embodies the Romantic sensibility in landscape painting. Gericault also explored the Romantic landscape in a series of views representing different times of day; in Evening: Landscape with an Aqueduct ( 1989.183 ), the dramatic sky, blasted tree, and classical ruins evoke a sense of melancholic reverie.

Another facet of the Romantic attitude toward nature emerges in the landscapes of John Constable , whose art expresses his response to his native English countryside. For his major paintings, Constable executed full-scale sketches, as in a view of Salisbury Cathedral ( 50.145.8 ); he wrote that a sketch represents “nothing but one state of mind—that which you were in at the time.” When his landscapes were exhibited in Paris at the Salon of 1824, critics and artists embraced his art as “nature itself.” Constable’s subjective, highly personal view of nature accords with the individuality that is a central tenet of Romanticism.

This interest in the individual and subjective—at odds with eighteenth-century rationalism—is mirrored in the Romantic approach to portraiture. Traditionally, records of individual likeness, portraits became vehicles for expressing a range of psychological and emotional states in the hands of Romantic painters. Gericault probed the extremes of mental illness in his portraits of psychiatric patients, as well as the darker side of childhood in his unconventional portrayals of children. In his portrait of Alfred Dedreux ( 41.17 ), a young boy of about five or six, the child appears intensely serious, more adult than childlike, while the dark clouds in the background convey an unsettling, ominous quality.

Such explorations of emotional states extended into the animal kingdom, marking the Romantic fascination with animals as both forces of nature and metaphors for human behavior. This curiosity is manifest in the sketches of wild animals done in the menageries of Paris and London in the 1820s by artists such as Delacroix, Antoine-Louis Barye, and Edwin Landseer. Gericault depicted horses of all breeds—from workhorses to racehorses—in his work. Lord Byron’s 1819 tale of Mazeppa tied to a wild horse captivated Romantic artists from Delacroix to Théodore Chassériau, who exploited the violence and passion inherent in the story. Similarly, Horace Vernet, who exhibited two scenes from Mazeppa in the Salon of 1827 (both Musée Calvet, Avignon), also painted the riderless horse race that marked the end of the Roman Carnival, which he witnessed during his 1820 visit to Rome. His oil sketch ( 87.15.47 ) captures the frenetic energy of the spectacle, just before the start of the race. Images of wild, unbridled animals evoked primal states that stirred the Romantic imagination.

Along with plumbing emotional and behavioral extremes, Romantic artists expanded the repertoire of subject matter, rejecting the didacticism of Neoclassical history painting in favor of imaginary and exotic subjects. Orientalism and the worlds of literature stimulated new dialogues with the past as well as the present. Ingres’ sinuous odalisques ( 38.65 ) reflect the contemporary fascination with the exoticism of the harem, albeit a purely imagined Orient, as he never traveled beyond Italy. In 1832, Delacroix journeyed to Morocco, and his trip to North Africa prompted other artists to follow. In 1846, Chassériau documented his visit to Algeria in notebooks filled with watercolors and drawings, which later served as models for paintings done in his Paris studio ( 64.188 ). Literature offered an alternative form of escapism. The novels of Sir Walter Scott, the poetry of Lord Byron, and the drama of Shakespeare transported art to other worlds and eras. Medieval England is the setting of Delacroix’s tumultuous Abduction of Rebecca ( 03.30 ), which illustrates an episode from Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe .

In its stylistic diversity and range of subjects, Romanticism defies simple categorization. As the poet and critic Charles Baudelaire wrote in 1846, “Romanticism is precisely situated neither in choice of subject nor in exact truth, but in a way of feeling.”

Galitz, Kathryn Calley. “Romanticism.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/roma/hd_roma.htm (October 2004)

Further Reading

Brookner, Anita. Romanticism and Its Discontents . New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux; : , 2000.

Honour, Hugh. Romanticism . New York: Harper & Row, 1979.

Additional Essays by Kathryn Calley Galitz

- Galitz, Kathryn Calley. “ The Legacy of Jacques Louis David (1748–1825) .” (October 2004)

- Galitz, Kathryn Calley. “ Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) .” (May 2009)

- Galitz, Kathryn Calley. “ The French Academy in Rome .” (October 2003)

Related Essays

- John Constable (1776–1837)

- Poets, Lovers, and Heroes in Italian Mythological Prints

- The Salon and the Royal Academy in the Nineteenth Century

- The Transformation of Landscape Painting in France

- Watercolor Painting in Britain, 1750–1850

- The Aesthetic of the Sketch in Nineteenth-Century France

- Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

- The Countess da Castiglione

- Gustave Courbet (1819–1877)

- James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) as Etcher

- The Legacy of Jacques Louis David (1748–1825)

- Lithography in the Nineteenth Century

- The Nabis and Decorative Painting

- Nadar (1820–1910)

- Nineteenth-Century Classical Music

- Nineteenth-Century French Realism

- Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art

- Paolo Veronese (1528–1588)

- The Pre-Raphaelites

- Shakespeare and Art, 1709–1922

- Shakespeare Portrayed

- Sixteenth-Century Painting in Venice and the Veneto

- Thomas Eakins (1844–1916): Painting

- Women Artists in Nineteenth-Century France

- France, 1800–1900 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1800–1900 A.D.

- 19th Century A.D.

- Architecture

- British Literature / Poetry

- Classical Ruins

- French Literature / Poetry

- Great Britain and Ireland

- History Painting

- Literature / Poetry

- Oil on Canvas

- Orientalism

- Preparatory Study

Artist or Maker

- Adamson, Robert

- Blake, William

- Blechen, Karl

- Chassériau, Théodore

- Constable, John

- Dahl, Johan Christian

- David, Jacques Louis

- Delacroix, Eugène

- Eakins, Thomas

- Friedrich, Caspar David

- Fuseli, Henry

- Gericault, Théodore

- Girodet-Trioson, Anne-Louis

- Gros, Antoine Jean

- Ingres, Jean Auguste Dominique

- Købke, Christen

- Turner, Joseph Mallord William

- Vernet, Horace

- Von Carolsfeld, Julius Schnorr

- Von Leypold, Julius

Online Features

- 82nd & Fifth: “Motion Picture” by Asher Miller

- Connections: “Fatherhood” by Tim Healing

1. Experiencing Literature: The Basics

The romantic period, 1820–1860: essayists and poets — american literature i, fresh new vision electrified artistic and intellectual circles.

The Romantic movement, which originated in Germany but quickly spread to England, France, and beyond, reached America around the year 1820, some twenty years after William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge had revolutionized English poetry by publishing Lyrical Ballads . In America as in Europe, fresh new vision electrified artistic and intellectual circles. Yet there was an important difference: Romanticism in America coincided with the period of national expansion and the discovery of a distinctive American voice. The solidification of a national identity and the surging idealism and passion of Romanticism nurtured the masterpieces of “the American Renaissance.”

Romantic ideas centered around art as inspiration, the spiritual and aesthetic dimension of nature, and metaphors of organic growth. Art, rather than science, Romantics argued, could best express universal truth. The Romantics underscored the importance of expressive art for the individual and society. In his essay “The Poet” (1844), Ralph Waldo Emerson, perhaps the most influential writer of the Romantic era, asserts:

For all men live by truth, and stand in need of expression. In love, in art, in avarice, in politics, in labor, in games, we study to utter our painful secret. The man is only half himself, the other half is his expression.

The development of the self became a major theme; self-awareness a primary method. If, according to Romantic theory, self and nature were one, self-awareness was not a selfish dead end but a mode of knowledge opening up the universe. If one’s self were one with all humanity, then the individual had a moral duty to reform social inequalities and relieve human suffering. The idea of “self”—which suggested selfishness to earlier generations—was redefined. New compound words with positive meanings emerged: “self-realization,” “self-expression,” “self-reliance.”

As the unique, subjective self became important, so did the realm of psychology. Exceptional artistic effects and techniques were developed to evoke heightened psychological states. The “sublime”—an effect of beauty in grandeur (for example, a view from a mountaintop)—produced feelings of awe, reverence, vastness, and a power beyond human comprehension.

Romanticism was affirmative and appropriate for most American poets and creative essayists. America’s vast mountains, deserts, and tropics embodied the sublime. The Romantic spirit seemed particularly suited to American democracy: It stressed individualism, affirmed the value of the common person, and looked to the inspired imagination for its aesthetic and ethical values. Certainly the New England Transcendentalists—Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and their associates—were inspired to a new optimistic affirmation by the Romantic movement. In New England, Romanticism fell upon fertile soil.

Transcendentalism

The Transcendentalist movement was a reaction against 18th century rationalism and a manifestation of the general humanitarian trend of nineteenth century thought. The movement was based on a fundamental belief in the unity of the world and God. The soul of each individual was thought to be identical with the world—a microcosm of the world itself. The doctrine of self-reliance and individualism developed through the belief in the identification of the individual soul with God.

Transcendentalism was intimately connected with Concord, a small New England village thirty-two kilometers west of Boston. Concord was the first inland settlement of the original Massachusetts Bay Colony. Surrounded by forest, it was and remains a peaceful town close enough to Boston’s lectures, bookstores, and colleges to be intensely cultivated, but far enough away to be serene. Concord was the site of the first battle of the American Revolution, and Ralph Waldo Emerson’s poem commemorating the battle, “Concord Hymn,” has one of the most famous opening stanzas in American literature:

By the rude bridge that arched the flood Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled, Here once the embattled farmers stood And fired the shot heard round the world.

Concord was the first rural artist’s colony, and the first place to offer a spiritual and cultural alternative to American materialism. It was a place of high-minded conversation and simple living (Emerson and Henry David Thoreau both had vegetable gardens). Emerson, who moved to Concord in 1834, and Thoreau are most closely associated with the town, but the locale also attracted the novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne, the feminist writer Margaret Fuller, the educator (and father of novelist Louisa May Alcott) Bronson Alcott, and the poet William Ellery Channing. The Transcendental Club was loosely organized in 1836 and included, at various times, Emerson, Thoreau, Fuller, Channing, Bronson Alcott, Orestes Brownson (a leading minister), Theodore Parker (abolitionist and minister), and others.

The Transcendentalists published a quarterly magazine, The Dial , which lasted four years and was first edited by Margaret Fuller and later by Emerson. Reform efforts engaged them as well as literature. A number of Transcendentalists were abolitionists, and some were involved in experimental utopian communities such as nearby Brook Farm (described in Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance ) and Fruitlands.

Unlike many European groups, the Transcendentalists never issued a manifesto. They insisted on individual differences – on the unique viewpoint of the individual. American Transcendental Romantics pushed radical individualism to the extreme. American writers often saw themselves as lonely explorers outside society and convention. The American hero—like Herman Melville’s Captain Ahab, or Mark Twain’s Huck Finn, or Edgar Allan Poe’s Arthur Gordon Pym—typically faced risk, or even certain destruction, in the pursuit of metaphysical self-discovery. For the Romantic American writer, nothing was a given. Literary and social conventions, far from being helpful, were dangerous. There was tremendous pressure to discover an authentic literary form, content, and voice – all at the same time. It is clear from the many masterpieces produced in the three decades before the U.S. Civil War (1861–65) that American writers rose to the challenge.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882)

Ralph Waldo Emerson, the towering figure of his era, had a religious sense of mission. Although many accused him of subverting Christianity, he explained that, for him “to be a good minister, it was necessary to leave the church.” The address he delivered in 1838 at his alma mater, the Harvard Divinity School, made him unwelcome at Harvard for thirty years. In it, Emerson accused the church of acting “as if God were dead” and of emphasizing dogma while stifling the spirit.

Emerson’s philosophy has been called contradictory, and it is true that he consciously avoided building a logical intellectual system because such a rational system would have negated his Romantic belief in intuition and flexibility. In his essay “Self-Reliance,” Emerson remarks: “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” Yet he is remarkably consistent in his call for the birth of American individualism inspired by nature. Most of his major ideas—the need for a new national vision, the use of personal experience, the notion of the cosmic Over-Soul, and the doctrine of compensation—are suggested in his first publication, Nature (1836). This essay opens:

Our age is retrospective. It builds the sepulchres of the fathers. It writes biographies, histories, criticism. The foregoing generations beheld God and nature face to face; we, through their eyes. Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Why should not we have a poetry of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs. Embosomed for a season in nature, whose floods of life stream around and through us, and invite us by the powers they supply, to action proportioned to nature, why should we grope among the dry bones of the past…? The sun shines today also. There is more wool and flax in the fields. There are new lands, new men, new thoughts. Let us demand our own works and laws and worship.

Emerson loved the aphoristic genius of the sixteenth-century French essayist Montaigne, and he once told Bronson Alcott that he wanted to write a book like Montaigne’s, “full of fun, poetry, business, divinity, philosophy, anecdotes, smut.” He complained that Alcott’s abstract style omitted “the light that shines on a man’s hat, in a child’s spoon.”

Spiritual vision and practical, aphoristic expression make Emerson exhilarating; one of the Concord Transcendentalists aptly compared listening to him with “going to heaven in a swing.” Much of his spiritual insight comes from his readings in Eastern religion, especially Hinduism, Confucianism, and Islamic Sufism. For example, his poem “Brahma” relies on Hindu sources to assert a cosmic order beyond the limited perception of mortals:

If the red slayer think he slay Or the slain think he is slain, They know not well the subtle ways I keep, and pass, and turn again. Far or forgot to me is near Shadow and sunlight are the same; The vanished gods to me appear; And one to me are shame and fame. They reckon ill who leave me out; When me they fly, I am the wings; I am the doubter and the doubt, And I the hymn the Brahmin sings The strong gods pine for my abode, And pine in vain the sacred Seven, But thou, meek lover of the good! Find me, and turn thy back on heaven.

This poem, published in the first number of the Atlantic Monthly magazine (1857), confused readers unfamiliar with Brahma, the highest Hindu god, the eternal and infinite soul of the universe. Emerson had this advice for his readers: “Tell them to say Jehovah instead of Brahma.”

The British critic Matthew Arnold said the most important writings in English in the nineteenth century had been Wordsworth’s poems and Emerson’s essays. A great prose-poet, Emerson influenced a long line of American poets, including Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Edwin Arlington Robinson, Wallace Stevens, Hart Crane, and Robert Frost. He is also credited with influencing the philosophies of John Dewey, George Santayana, Friedrich Nietzsche, and William James.

Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862)

Henry David Thoreau, of French and Scottish descent, was born in Concord and made it his permanent home. From a poor family, like Emerson, he worked his way through Harvard. Throughout his life, he reduced his needs to the simplest level and managed to live on very little money, thus maintaining his independence. In essence, he made living his career. A nonconformist, he attempted to live his life at all times according to his rigorous principles. This attempt was the subject of many of his writings.

Thoreau’s masterpiece, Walden , or Life in the Woods (1854), is the result of two years, two months, and two days (from 1845 to 1847) he spent living in a cabin he built at Walden Pond on property owned by Emerson. In Walden , Thoreau consciously shapes this time into one year, and the book is carefully constructed so the seasons are subtly evoked in order. The book also is organized so that the simplest earthly concerns come first (in the section called “Economy,” he describes the expenses of building a cabin); by the ending, the book has progressed to meditations on the stars.

In Walden , Thoreau, a lover of travel books and the author of several, gives us an anti-travel book that paradoxically opens the inner frontier of self-discovery as no American book had up to this time. As deceptively modest as Thoreau’s ascetic life, it is no less than a guide to living the classical ideal of the good life. Both poetry and philosophy, this long poetic essay challenges the reader to examine his or her life and live it authentically. The building of the cabin, described in great detail, is a concrete metaphor for the careful building of a soul. In his journal for January 30, 1852, Thoreau explains his preference for living rooted in one place: “I am afraid to travel much or to famous places, lest it might completely dissipate the mind.”

Thoreau’s method of retreat and concentration resembles Asian meditation techniques. The resemblance is not accidental: like Emerson and Whitman, he was influenced by Hindu and Buddhist philosophy. His most treasured possession was his library of Asian classics, which he shared with Emerson. His eclectic style draws on Greek and Latin classics and is crystalline, punning, and as richly metaphorical as the English metaphysical writers of the late Renaissance.

In Walden , Thoreau not only tests the theories of Transcendentalism, he reenacts the collective American experience of the nineteenth century: living on the frontier. Thoreau felt that his contribution would be to renew a sense of the wilderness in language. His journal has an undated entry from 1851:

English literature from the days of the minstrels to the Lake Poets, Chaucer and Spenser and Shakespeare and Milton included, breathes no quite fresh and in this sense, wild strain. It is an essentially tame and civilized literature, reflecting Greece and Rome. Her wilderness is a greenwood, her wildman a Robin Hood. There is plenty of genial love of nature in her poets, but not so much of nature herself. Her chronicles inform us when her wild animals, but not the wildman in her, became extinct. There was need of America.

Walden inspired William Butler Yeats, a passionate Irish nationalist, to write “The Lake Isle of Innisfree,” while Thoreau’s essay “Civil Disobedience,” with its theory of passive resistance based on the moral necessity for the just individual to disobey unjust laws, was an inspiration for Mahatma Gandhi’s Indian independence movement and Martin Luther King’s struggle for black Americans’ civil rights in the twentieth century.

Thoreau is the most attractive of the Transcendentalists today because of his ecological consciousness, do-it-yourself independence, ethical commitment to abolitionism, and political theory of civil disobedience and peaceful resistance. His ideas are still fresh, and his incisive poetic style and habit of close observation are still modern.

Walt Whitman (1819–1892)

Born on Long Island, New York, Walt Whitman was a part-time carpenter and man of the people, whose brilliant, innovative work expressed the country’s democratic spirit. Whitman was largely self-taught; he left school at the age of 11 to go to work, missing the sort of traditional education that made most American authors respectful imitators of the English. His Leaves of Grass (1855), which he rewrote and revised throughout his life, contains “Song of Myself,” the most stunningly original poem ever written by an American. The enthusiastic praise that Emerson and a few others heaped on this daring volume confirmed Whitman in his poetic vocation, although the book was not a popular success.

A visionary book celebrating all creation, Leaves of Grass was inspired largely by Emerson’s writings, especially his essay “The Poet,” which predicted a robust, open-hearted, universal kind of poet uncannily like Whitman himself. The poem’s innovative, unrhymed, free-verse form, open celebration of sexuality, vibrant democratic sensibility, and extreme Romantic assertion that the poet’s self was one with the poem, the universe, and the reader permanently altered the course of American poetry.

Leaves of Grass is as vast, energetic, and natural as the American continent; it was the epic generations of American critics had been calling for, although they did not recognize it. Movement ripples through “Song of Myself” like restless music:

My ties and ballasts leave me . . . I skirt sierras, my palms cover continents I am afoot with my vision.

The poem bulges with myriad concrete sights and sounds. Whitman’s birds are not the conventional “winged spirits” of poetry. His “yellow-crown’d heron comes to the edge of the marsh at night and feeds upon small crabs.” Whitman seems to project himself into everything that he sees or imagines. He is mass man, “Voyaging to every port to dicker and adventure, / Hurrying with the modern crowd as eager and fickle as any.” But he is equally the suffering individual, “The mother of old, condemn’d for a witch, burnt with dry wood, her children gazing on….I am the hounded slave, I wince at the bite of the dogs….I am the mash’d fireman with breast-bone broken….”