Editing and Proofreading

What this handout is about.

This handout provides some tips and strategies for revising your writing. To give you a chance to practice proofreading, we have left seven errors (three spelling errors, two punctuation errors, and two grammatical errors) in the text of this handout. See if you can spot them!

Is editing the same thing as proofreading?

Not exactly. Although many people use the terms interchangeably, editing and proofreading are two different stages of the revision process. Both demand close and careful reading, but they focus on different aspects of the writing and employ different techniques.

Some tips that apply to both editing and proofreading

- Get some distance from the text! It’s hard to edit or proofread a paper that you’ve just finished writing—it’s still to familiar, and you tend to skip over a lot of errors. Put the paper aside for a few hours, days, or weeks. Go for a run. Take a trip to the beach. Clear your head of what you’ve written so you can take a fresh look at the paper and see what is really on the page. Better yet, give the paper to a friend—you can’t get much more distance than that. Someone who is reading the paper for the first time, comes to it with completely fresh eyes.

- Decide which medium lets you proofread most carefully. Some people like to work right at the computer, while others like to sit back with a printed copy that they can mark up as they read.

- Try changing the look of your document. Altering the size, spacing, color, or style of the text may trick your brain into thinking it’s seeing an unfamiliar document, and that can help you get a different perspective on what you’ve written.

- Find a quiet place to work. Don’t try to do your proofreading in front of the TV or while you’re chugging away on the treadmill. Find a place where you can concentrate and avoid distractions.

- If possible, do your editing and proofreading in several short blocks of time. Your concentration may start to wane if you try to proofread the entire text at one time.

- If you’re short on time, you may wish to prioritize. Make sure that you complete the most important editing and proofreading tasks.

Editing is what you begin doing as soon as you finish your first draft. You reread your draft to see, for example, whether the paper is well-organized, the transitions between paragraphs are smooth, and your evidence really backs up your argument. You can edit on several levels:

Have you done everything the assignment requires? Are the claims you make accurate? If it is required to do so, does your paper make an argument? Is the argument complete? Are all of your claims consistent? Have you supported each point with adequate evidence? Is all of the information in your paper relevant to the assignment and/or your overall writing goal? (For additional tips, see our handouts on understanding assignments and developing an argument .)

Overall structure

Does your paper have an appropriate introduction and conclusion? Is your thesis clearly stated in your introduction? Is it clear how each paragraph in the body of your paper is related to your thesis? Are the paragraphs arranged in a logical sequence? Have you made clear transitions between paragraphs? One way to check the structure of your paper is to make a reverse outline of the paper after you have written the first draft. (See our handouts on introductions , conclusions , thesis statements , and transitions .)

Structure within paragraphs

Does each paragraph have a clear topic sentence? Does each paragraph stick to one main idea? Are there any extraneous or missing sentences in any of your paragraphs? (See our handout on paragraph development .)

Have you defined any important terms that might be unclear to your reader? Is the meaning of each sentence clear? (One way to answer this question is to read your paper one sentence at a time, starting at the end and working backwards so that you will not unconsciously fill in content from previous sentences.) Is it clear what each pronoun (he, she, it, they, which, who, this, etc.) refers to? Have you chosen the proper words to express your ideas? Avoid using words you find in the thesaurus that aren’t part of your normal vocabulary; you may misuse them.

Have you used an appropriate tone (formal, informal, persuasive, etc.)? Is your use of gendered language (masculine and feminine pronouns like “he” or “she,” words like “fireman” that contain “man,” and words that some people incorrectly assume apply to only one gender—for example, some people assume “nurse” must refer to a woman) appropriate? Have you varied the length and structure of your sentences? Do you tends to use the passive voice too often? Does your writing contain a lot of unnecessary phrases like “there is,” “there are,” “due to the fact that,” etc.? Do you repeat a strong word (for example, a vivid main verb) unnecessarily? (For tips, see our handouts on style and gender-inclusive language .)

Have you appropriately cited quotes, paraphrases, and ideas you got from sources? Are your citations in the correct format? (See the UNC Libraries citation tutorial for more information.)

As you edit at all of these levels, you will usually make significant revisions to the content and wording of your paper. Keep an eye out for patterns of error; knowing what kinds of problems you tend to have will be helpful, especially if you are editing a large document like a thesis or dissertation. Once you have identified a pattern, you can develop techniques for spotting and correcting future instances of that pattern. For example, if you notice that you often discuss several distinct topics in each paragraph, you can go through your paper and underline the key words in each paragraph, then break the paragraphs up so that each one focuses on just one main idea.

Proofreading

Proofreading is the final stage of the editing process, focusing on surface errors such as misspellings and mistakes in grammar and punctuation. You should proofread only after you have finished all of your other editing revisions.

Why proofread? It’s the content that really matters, right?

Content is important. But like it or not, the way a paper looks affects the way others judge it. When you’ve worked hard to develop and present your ideas, you don’t want careless errors distracting your reader from what you have to say. It’s worth paying attention to the details that help you to make a good impression.

Most people devote only a few minutes to proofreading, hoping to catch any glaring errors that jump out from the page. But a quick and cursory reading, especially after you’ve been working long and hard on a paper, usually misses a lot. It’s better to work with a definite plan that helps you to search systematically for specific kinds of errors.

Sure, this takes a little extra time, but it pays off in the end. If you know that you have an effective way to catch errors when the paper is almost finished, you can worry less about editing while you are writing your first drafts. This makes the entire writing proccess more efficient.

Try to keep the editing and proofreading processes separate. When you are editing an early draft, you don’t want to be bothered with thinking about punctuation, grammar, and spelling. If your worrying about the spelling of a word or the placement of a comma, you’re not focusing on the more important task of developing and connecting ideas.

The proofreading process

You probably already use some of the strategies discussed below. Experiment with different tactics until you find a system that works well for you. The important thing is to make the process systematic and focused so that you catch as many errors as possible in the least amount of time.

- Don’t rely entirely on spelling checkers. These can be useful tools but they are far from foolproof. Spell checkers have a limited dictionary, so some words that show up as misspelled may really just not be in their memory. In addition, spell checkers will not catch misspellings that form another valid word. For example, if you type “your” instead of “you’re,” “to” instead of “too,” or “there” instead of “their,” the spell checker won’t catch the error.

- Grammar checkers can be even more problematic. These programs work with a limited number of rules, so they can’t identify every error and often make mistakes. They also fail to give thorough explanations to help you understand why a sentence should be revised. You may want to use a grammar checker to help you identify potential run-on sentences or too-frequent use of the passive voice, but you need to be able to evaluate the feedback it provides.

- Proofread for only one kind of error at a time. If you try to identify and revise too many things at once, you risk losing focus, and your proofreading will be less effective. It’s easier to catch grammar errors if you aren’t checking punctuation and spelling at the same time. In addition, some of the techniques that work well for spotting one kind of mistake won’t catch others.

- Read slow, and read every word. Try reading out loud , which forces you to say each word and also lets you hear how the words sound together. When you read silently or too quickly, you may skip over errors or make unconscious corrections.

- Separate the text into individual sentences. This is another technique to help you to read every sentence carefully. Simply press the return key after every period so that every line begins a new sentence. Then read each sentence separately, looking for grammar, punctuation, or spelling errors. If you’re working with a printed copy, try using an opaque object like a ruler or a piece of paper to isolate the line you’re working on.

- Circle every punctuation mark. This forces you to look at each one. As you circle, ask yourself if the punctuation is correct.

- Read the paper backwards. This technique is helpful for checking spelling. Start with the last word on the last page and work your way back to the beginning, reading each word separately. Because content, punctuation, and grammar won’t make any sense, your focus will be entirely on the spelling of each word. You can also read backwards sentence by sentence to check grammar; this will help you avoid becoming distracted by content issues.

- Proofreading is a learning process. You’re not just looking for errors that you recognize; you’re also learning to recognize and correct new errors. This is where handbooks and dictionaries come in. Keep the ones you find helpful close at hand as you proofread.

- Ignorance may be bliss, but it won’t make you a better proofreader. You’ll often find things that don’t seem quite right to you, but you may not be quite sure what’s wrong either. A word looks like it might be misspelled, but the spell checker didn’t catch it. You think you need a comma between two words, but you’re not sure why. Should you use “that” instead of “which”? If you’re not sure about something, look it up.

- The proofreading process becomes more efficient as you develop and practice a systematic strategy. You’ll learn to identify the specific areas of your own writing that need careful attention, and knowing that you have a sound method for finding errors will help you to focus more on developing your ideas while you are drafting the paper.

Think you’ve got it?

Then give it a try, if you haven’t already! This handout contains seven errors our proofreader should have caught: three spelling errors, two punctuation errors, and two grammatical errors. Try to find them, and then check a version of this page with the errors marked in red to see if you’re a proofreading star.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Especially for non-native speakers of English:

Ascher, Allen. 2006. Think About Editing: An ESL Guide for the Harbrace Handbooks . Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Lane, Janet, and Ellen Lange. 2012. Writing Clearly: Grammar for Editing , 3rd ed. Boston: Heinle.

For everyone:

Einsohn, Amy. 2011. The Copyeditor’s Handbook: A Guide for Book Publishing and Corporate Communications , 3rd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lanham, Richard A. 2006. Revising Prose , 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman.

Tarshis, Barry. 1998. How to Be Your Own Best Editor: The Toolkit for Everyone Who Writes . New York: Three Rivers Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

How to Read Backwards

Last Updated: February 17, 2024

This article was co-authored by wikiHow Staff . Our trained team of editors and researchers validate articles for accuracy and comprehensiveness. wikiHow's Content Management Team carefully monitors the work from our editorial staff to ensure that each article is backed by trusted research and meets our high quality standards. This article has been viewed 69,375 times. Learn more...

We all know the importance of exercising our bodies, but what about exercising our minds? Reading words backwards helps to keep your mind active and improve your reading skills. As English readers and writers, we are accustomed to reading left to right. To challenge your brain, try reading from right to left, instead.

Reading from Right to Left

- Because you are accustomed to reading left-to-right, your brain naturally prefers this direction; essentially what you are doing is re-teaching it how to track from right to left (called "directional tracking").

- Practice reading several times over the next few days. Spacing out your practice over time helps you feel more comfortable reading and recognizing words from the opposite direction, from right to left rather than left to right.

- Practice makes perfect! Here's an example. Try to figure out what it says.

- snoitalutargnoC .sdrawkcab gnidaer era uoy siht daer nac uoy fI

Using Visualization

Reading Mirror Image Text

- Mirror image writing is different from right to left backwards writing. In mirror image writing, each individual letter appears backwards, but the letters are still in left to right order.

- You can see the effect if you hold up regular text to a mirror.

- Write your text on a piece of paper in normal writing.

- Have a friend hold it in front of a mirror.

- Use a piece of tracing paper to trace over the mirror image of your text.

- The text on the tracing paper will be your message, in mirror image backwards writing.

Community Q&A

- Also practice reading in a mirror and reading upside-down. Both activities are good practice at reversing the order of letters. Reading a word through a piece of paper by holding it up to the light is the same as holding it up to a mirror [2] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- When you know lots of words backwards, test your friends and family! Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Try writing something backwards and leave it for a target to get confused. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.education.com/reference/article/reading-development-stages-Chall/

- ↑ https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/volume-25/edition-10/mirror-writing

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Dec 7, 2017

Did this article help you?

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

- Twin Cities

- Other Locations

- Hours & locations

- by appointment in Nicholson

- Zoom appointments

- How does it work?

- Frequently asked questions

- Tech troubleshooting

- Important policies

- Especially for multilingual writers

- Especially for graduate writers

- Writing process

- Common writing projects

- Punctuation

- Documenting sources

- Consultant bios

- Resources for instructors

- Why participate?

- How to apply

- Participant history

- E-12 Writing Centers Collective

- Job opportunities

schedule, manage, and access your SWS visits

Email [email protected] for questions about Student Writing Support

Phone 612-625-1893

center for writing | student writing support | writing process | editing & proofreading strategies

Editing & proofreading strategies

Editing and proofreading are essential aspects of effective writing. However, they are the later steps in the ongoing process of brainstorming, planning, drafting, and revising. Writers who rush or ignore any of these earlier steps can end up with a paper that is unclear, underdeveloped, and very difficult to correct in the later stages of the writing process. When you are ready to proofread and edit your draft, you should do so carefully and thoroughly. While it is important to review your work and seek feedback, the following strategies may also prove useful.

Leave yourself plenty of time for all steps of the writing process, including editing.

By making and following a timeline for the paper, you are more likely to have time to finish everything with the proper amount of care and attention. Also, keep in mind that it may be best to lay your paper aside for a day or so before proofreading and editing, as you may be more likely to catch errors or notice structural problems if your writing isn’t so “fresh” in your mind.

Get acquainted with your resources.

You don’t need to memorize every grammar or citation rule that may apply to the genre or discipline in which you’re writing—you can look them up. Take advantage of the resources available to you: dictionaries, thesauruses, handbooks, citation guides, handouts from class, librarians, and writing center consultants.

Know your weaknesses.

Keep a list of errors you tend to make: it will help you know what to look for when you edit. You can also read the paper once for each error type—if you’re only looking for one thing, you’ll be more likely to notice it.

Print a copy of your paper to use when editing and proofreading.

It is much harder to catch errors on a screen than on paper.

Read your paper out loud.

Often, when we read silently, our eyes skip over small errors, awkward or run-on sentences, and typos. By reading out loud, you force yourself to notice everything from spelling and word choice to the structure of sentences. You can also have someone read your paper aloud and tell you where they are confused.

Read your paper backwards.

Another way to force yourself to notice small details is to take things out of context. Try reading your paper backwards, sentence by sentence or paragraph by paragraph, so that you are focusing on the text, not the ideas. This technique is especially helpful for catching sentence fragments.

Check the punctuation .

Look over the paper on a sentence-by-sentence level to see if your punctuation is correct. Are commas in the right places? Are there any run-on sentences? If you aren’t sure about how to use certain kinds of punctuation, look in a manual, explore other quicktips, and/or ask a writing consultant for help.

Check the citations .

Check each in-text citation for correct format, and verify that the source is in the Works Cited or References list. This is also a good time to double-check the spelling of authors’ names, book or article titles, and so on.

Reread quotations.

It is all too easy to mistype when copying words.

Get feedback from other people.

Because we are such a part of what we write, it can be difficult to step outside our work and view it critically. When you seek outside opinions, you can break free of the isolation and absorption of writing and receive perspectives and insights that you may have otherwise missed. You are no longer left wondering whether you followed the guidelines of the assignment, whether your structure and language are clear, etc. By asking for feedback from other people, you are taking essential measures to improve your writing and to develop as a writer.

Don’t rely solely on computer help.

Spell-check and grammar-check tools are useful, but they do not constitute or substitute for proofreading. Develop and follow your own editing strategies, and don’t be fooled into thinking that computer tools alone are adequate for the job.

Rest. Relax. Reread.

Leave your paper alone for a day or two. Having some distance from what you’ve written can make your proofreader’s eye more clinical and perceptive. In addition, you may find changes you would like to make after you read your text later.

Adapted from The University of Minnesota’s Student Writing Guide , 2004, p. 29, and from The College of Education & Human Development Writing Center’s handout, “Editing and Proofreading Strategies.”

- Address: 15 Nicholson Hall , 216 Pillsbury Dr SE , Minneapolis, MN 55455 | Phone: 612.625.1893

- Address: 9 Appleby Hall , 128 Pleasant St SE , Minneapolis, MN 55455

- © 2011 Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved.

- The University of Minnesota is an equal opportunity educator and employer

- Last modified on October 25, 2023

- Twin Cities Campus:

- Parking & Transportation

- Maps & Directions

- Directories

- Contact U of M

- Main Library of Critical Thinking Resources

- Defining Critical Thinking

- A Brief History of the Idea of Critical Thinking

- Critical Thinking: Basic Questions & Answers

- Our Conception of Critical Thinking

- Sumner’s Definition of Critical Thinking

- Research in Critical Thinking

- Critical Societies: Thoughts from the Past

- Content Is Thinking, Thinking is Content

- Critical Thinking in Every Domain of Knowledge and Belief

- Using Intellectual Standards to Assess Student Reasoning

- Open-minded inquiry

- Valuable Intellectual Traits

- Universal Intellectual Standards

- Thinking With Concepts

- The Analysis & Assessment of Thinking

- Glossary of Critical Thinking Terms

- Distinguishing Between Inert Information, Activated Ignorance, Activated Knowledge

- Critical Thinking: Identifying the Targets

- Distinguishing Between Inferences and Assumptions

- Critical Thinking Development: A Stage Theory

- Becoming a Critic Of Your Thinking

- Bertrand Russell on Critical Thinking

- Richard Paul Anthology Classic

- Intellectual Foundations: The Key Missing Piece in School Restructuring

- Pseudo Critical Thinking in the Educational Establishment

- Research Findings and Policy Recommendations

- Why Students and Teachers Don’t Reason Well

- Critical Thinking in the Engineering Enterprise: Novices typically don't even know what questions to ask

- Critical Thinking Movement: 3 Waves

- An Overview of How to Design Instruction Using Critical Thinking Concepts

- Recommendations for Departmental Self-Evaluation

- College-Wide Grading Standards

- Sample Course: American History: 1600 to 1800

- CT Class Syllabus

- Syllabus - Psychology I

- A Sample Assignment Format

- Grade Profiles

- Critical Thinking Class: Student Understandings

- Structures for Student Self-Assessment

- Critical Thinking Class: Grading Policies

- Socratic Teaching

- John Stuart Mill: On Instruction, Intellectual Development, and Disciplined Learning

- Critical Thinking and Nursing

- Tactical and Structural Recommendations

- Teaching Tactics that Encourage Active Learning

- The Art of Redesigning Instruction

- Making Critical Thinking Intuitive

- Remodelled Lessons: K-3

- Remodelled Lessons: 4-6

- Remodelled Lessons: 6-9

- Remodelled Lessons: High School

- Introduction to Remodelling: Components of Remodels and Their Functions

- Strategy List: 35 Dimensions of Critical Thought

- Critical Thinking in Everyday Life: 9 Strategies

- Developing as Rational Persons: Viewing Our Development in Stages

- How to Study and Learn (Part One)

- How to Study and Learn (Part Two)

- How to Study and Learn (Part Three)

- How to Study and Learn (Part Four)

- The Art of Close Reading (Part One)

- The Art of Close Reading (Part Two)

- The Art of Close Reading (Part Three)

- Looking To The Future With a Critical Eye: A Message for High School Graduates

- For Young Students (Elementary/K-6)

- Critical Thinking and the Social Studies Teacher

- Ethical Reasoning Essential to Education

- Ethics Without Indoctrination

- Engineering Reasoning

- Accelerating Change

- Applied Disciplines: A Critical Thinking Model for Engineering

- Global Change: Why C.T. is Essential To the Community College Mission

- Natural Egocentric Dispositions

- Diversity: Making Sense of It Through Critical Thinking

- Critical Thinking, Moral Integrity and Citizenship

- Critical Thinking and Emotional Intelligence

- Newton, Darwin, & Einstein

- The Role of Socratic Questioning in Thinking, Teaching, & Learning

- Complex Interdisciplinary Questions Exemplified: Ecological Sustainability

- The Critical Mind is A Questioning Mind

- Three Categories of Questions: Crucial Distinctions

- A History of Freedom of Thought

- Reading Backwards: Classic Books Online

Translate this page from English...

*Machine translated pages not guaranteed for accuracy. Click Here for our professional translations.

Reading Backwards

Insightful Authors Through the Ages -

When you read backwards, you will come to understand some of the stereotypes and misconceptions of the present. You will develop a better sense of what is universal and what is relative, what is essential and what is arbitrary.

Note: We recognize that this list of authors represents a decidedly Western worldview. We therefore recommend, once you have grounded yourself in deeply insightful authors from the Western world, that you then read works by the great Eastern authors.

Here are some authors we recommend:

- More than 2,000 years ago: Plato, Aristotle, Aeschylus, Aristophanes

- 1200s: Thomas Aquinas, Dante

- 1300s: Boccaccio, Chaucer

- 1400s: Erasmus, Francis Bacon

- 1500s: Machiavelli, Cellini, Cervantès, Montaigne

- 1600s: John Milton, Pascal, John Dryden, John Locke, Joseph Addison

- 1700s: Thomas Paine, Thomas Jefferson, Adam Smith, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Pope, Edmund Burke, Edward Gibbon, Samuel Johnson, Goethe, Rousseau, William Blake

- 1800s: Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, Emile Zola, Balzac, Dostoyevsky, Sigmund Freud, Karl Marx, Charles Darwin, John Henry Newman, John Stuart Mill, Leo Tolstoy, the Brontes, Frank Norris, Thomas Hardy, Emile Durkheim, Edmond Rostand, Oscar Wilde

- 1900s: Ambrose Bierce, Gustavus Myers, H.L. Mencken, William Graham Sumner, W.H. Auden, Bertolt Brecht, Joseph Conrad, Max Weber, Aldous Huxley, Franz Kafka, Sinclair Lewis, Henry James, Jean-Paul Sartre, Virginia Woolf, William Appleman Williams, Arnold Toynbee, C. Wright Mills, Albert Camus, Willa Cather, Bertrand Russell, Karl Mannheim, Thomas Mann, Albert Einstein, Simone De Beauvoir, Winston Churchill, William J. Lederer, Vance Packard, Eric Hoffer, Erving Goffman, Philip Agee, John Steinbeck, Ludwig Wittgenstein, William Faulkner, Talcott Parsons, Jean Piaget, Lester Thurow, Robert Reich, Robert Heilbroner, Noam Chomsky, Jacques Barzun, Ralph Nader, Margaret Mead, Bronislaw Malinowski, Karl Popper, Robert Merton, Peter Berger, Milton Friedman, J. Bronowski

- The Analysis of the Mind

- Policitcal Ideals

- The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism

- The Problem of China

- The Problem of Philosophy

- Proposed Roads to Freedom

- How Bertrand Russel was Prevented from Teaching at the College of the City of New York

- Bertrand Russell: To our Descendants (Video)

- Anarchism and Other Essays

- Marriage and Love

The Center for Critical Thinking Community Online is the world’s leading online community dedicated to teaching and advancing critical thinking. Featuring the world's largest library of critical thinking articles, videos, and books, as well as learning activities, study groups, and a social media component, this interactive learning platform is essential to anyone dedicated to developing as an effective reasoner in the classroom, in the professions, in business and government, and throughout personal life.

Join the community and learn explicit tools of critical thinking.

For full copies of this and many other critical thinking articles, books, videos, and more, join us at the Center for Critical Thinking Community Online - the world's leading online community dedicated to critical thinking! Also featuring interactive learning activities, study groups, and even a social media component, this learning platform will change your conception of intellectual development.

For Students

- Online Writing Lab

- Writing Resources

- Become a Writing Center Intern

For Faculty

- Request a Tour Presentation

About the UWC

- Department of Rhetoric and Writing

- South Central Writing Centers Association

- Writing Centers Research Project

Tips For Effective Proofreading

Proofread backwards. Begin at the end and work back through the paper paragraph by paragraph or even line by line. This will force you to look at the surface elements rather than the meaning of the paper.

Place a ruler under each line as you read it. This will give your eyes a manageable amount of text to read.

Know your own typical mistakes. Before you proofread, look over papers you have written in the past. Make a list of the errors you make repeatedly.

Proofread for one type of error at a time. If commas are your most frequent problem, go through the paper checking just that one problem. Then proofread again for the next most frequent problem.

Try to make a break between writing and proofreading. Set the paper aside for the night — or even for twenty minutes.

Proofread at the time of day when you are most alert to spotting errors.

Proofread once aloud. This will slow you down and you will hear the difference between what you meant to write and what you actually wrote.

Try to give yourself a break between the time you complete your final version of the paper and the time you sit down to edit. Approaching your writing with a clear head and having at least an hour to work on editing will ensure that you can do a thorough, thoughtful job. The results will definitely be worthwhile.

Ask someone else to read over your paper and help you find sentences that aren’t clear, places where you’re being wordy, and any errors.

Try reading backwards, a sentence at a time. This will help you focus on the sentences, rather than getting caught up in the content of your paper.

Know your own patterns. Your instructor can probably help you identify the errors you’ve made most often in your previous papers, and then you can focus your attention on finding and fixing them.

Read through your paper several times , once looking just at spelling, another time looking just at punctuation, and so on. Again, this can help you focus so you’ll do a better job.

Use the spell-checker on your computer, but use it carefully, and also do your own spell-checking. Computer spell-checkers often make errors – they might suggest a word that isn’t what you want at all, and they don’t know the difference between there, their, and they’re, for example.

Get help. If you’re not sure if you need that comma or whether to use “affect” or “effect,” look it up in a writing handbook, or ask your instructor for help.

Remember that editing isn’t just about errors. You want to polish your sentences at this point, making them smooth, interesting, and clear. Watch for very long sentences, since they may be less clear than shorter, more direct sentences. Pay attention to the rhythm of your writing; try to use sentences of varying lengths and patterns. Look for unnecessary phrases, repetition, and awkward spots.

- University Writing Center

- Ottenheimer Library - 1st Floor Learning Commons

- Phone: 501-916-6454

- More contact information

Proofread Using the Top Five Most Useful Techniques

Ouch follow the rules below and you're sure not to end up in the same position..

Proofreading is a drag—after having come up with a thesis, found evidence to support that thesis, and structured the essay to best support your ideas, you have to find and fix all of the mistakes you made along the way. I also find proofreading stressful; I worry that small mistakes will undermine all my hard work. Luckily, over time I’ve developed a series of techniques, which help me proofread; I’ve collected here five of what I believe to be the most useful proofreading techniques, all of which are great used alone, or in combination.

1. Read Aloud

Reading aloud is, without a doubt, the single most issue revision practice. Doing so you will not only notice small mistakes—missing words, misused words, misplaced (or missing!) punctuation—but you will also notice issues of phrasing and pacing.

2. Change the Font

Another thing that can make it difficult to catch mistakes is being overly familiar with your writing and the way it looks—mistakes and all—on the page. I’ve found that changing the font of what I’m working on can be a good way of making the document unfamiliar once again.

3. Print it out

To catch mistakes in your writing, it is absolutely necessary to read slowly and deliberately. This can often be hard to do while working on a computer (I don’t know about you but I tend to distractedly skim much of what I read on my laptop!). A good way to get yourself to slow down is to print out your essay and sit down to reread it in a distraction free (i.e., laptop, phone, music, friend, and fun free) environment. If I know I’m going to have to do a lot of this sort of proofreading—during finals week for instance—I like to buy myself neon colored pens to make the whole process just a bit more engaging.

Another pro-tip: If you think you’re going to need to make substantial changes—adding whole clauses, entire sentences—it can be helpful to make the right hand margin extra wide (2 ½ to 3 inches) before printing it out so that you have space to write these changes in.

4. Read Backwards

It might make you feel like a crazy person, but reading your essay backwards sentence by sentence is an excellent way of catching run-ons and fragments.

5. Use a Text-to-Speech Service

An issue that I have run into while I proofeead is that even if I am reading aloud I will often simply read over mistakes— using a text to speech program is awesome not only because it is mid-90’s retro but also because it will force you to hear exactly what you’ve typed. I like to use the Read&Write plug in for Google Chrome.

There you have it! Use these techniques to proofread and you'll have yourself a mistake free essay. Happy proofreading!

For more tips and tricks on expository writing, check out these other blog posts written by our writing tutors in New York and Boston: The Vital Importance of Writing Badly , Transitioning From One Paragraph to the Next , and How Do I Write a Good Thesis? Looking to work with an expository writing tutor on your essays? Feel free to get in touch ! Cambridge Coaching offers private in-person tutoring in New York City and Boston, and online tutoring around the world.

Related Content

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Editing is the very final step in writing an essay. Think of editing as the icing on the cake. This is where a writer will make the final product look great. Students should not begin editing until they are sure that the draft is exactly how they want it.

Submitting papers to a service like Turnitin or Grammarly can help students find grammar, punctuation, and spelling errors. However, while Turnitin and Grammarly are both wonderful options for helping you edit your papers, understanding the basics of grammar will help you to make better editing decisions.

Whether you are new to the English language or a native speaker, learning the rules of grammar might seem intimidating. However, it’s important to remember that, if you are speaking English, you are using grammar. You might not know the terms to talk about how you speak, but the knowledge is there. If you are a native speaker, you likely know whether or not something sounds correct.

Here is a great checklist to use prior to submitting a final draft:

Editing Checklist

Editing Checklist for Academic Essays

- Appropriate headings and page numbering are used

- Margins are correct: 1/2 inch from top to right header, 1 inch all around

- Spacing is set to double, with no extra line spaces between headings and title, title and body, or between paragraphs

- Within the essay, parenthetical citations are used (Lastname 13).

- A works cited page is included when appropriate, with all necessary information.

Mechanics: Spelling, Punctuation, Grammar, Syntax

- Did I run spell-check?

- Did I check homonyms? (Example: to, too, and two)

- Did I look up difficult words?

- Did I proofread aloud to catch obvious errors?

- Are all sentences complete (subject & verb, complete thought)?

- Did I use one verb tense throughout (unless there was a good reason to switch)?

- Did I use present tense verbs to discuss texts?

- Have I checked for run-on sentences and comma splices?

- Does my paper flow when read aloud? Did I use different sentence lengths and styles?

“ Editing Checklist ” from The Word on College Reading and Writing by Babin, et al licensed by CC NC 4.0 .

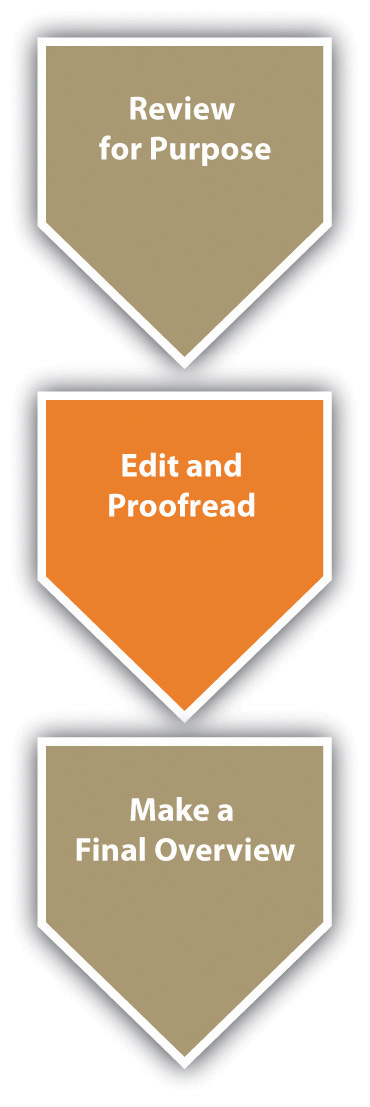

Editing and Proofreading

When you have made some revisions to your draft based on feedback and your recalibration of your purpose for writing, you may now feel your essay is nearly complete. However, you should plan to read through the entire final draft at least one additional time. During this stage of editing and proofreading your entire essay, you should be looking for general consistency and clarity. Also, pay particular attention to parts of the paper you have moved around or changed in other ways to make sure that your new versions still work smoothly.

Although you might think editing and proofreading isn’t necessary since you were fairly careful when you were writing, the truth is that even the very brightest people and best writers make mistakes when they write. One of the main reasons that you are likely to make mistakes is that your mind and fingers are not always moving along at the same speed nor are they necessarily in sync. So what ends up on the page isn’t always exactly what you intended. A second reason is that, as you make changes and adjustments, you might not totally match up the original parts and revised parts. Finally, a third key reason for proofreading is because you likely have errors you typically make and proofreading gives you a chance to correct those errors.

Editing and proofreading can work well with a partner. You can offer to be another pair of eyes for peers in exchange for their doing the same for you. Whether you are editing and proofreading your work or the work of a peer, the process is basically the same. Although the rest of this section assumes you are editing and proofreading your work, you can simply shift the personal issues, such as “Am I…” to a viewpoint that will work with a peer, such as “Is she…”

As you edit and proofread, you should look for common problem areas that stick out, including the quality writing components covered in sentence style, word choice, punctuation, mechanic, grammar, sentence building. There are certain writing rules that you must follow, but other more stylistic writing elements are more subjective and will require judgment calls on your part.

Be proactive in evaluating these subjective, stylistic issues since failure to do so can weaken the potential impact of your essay. Keeping the following questions in mind as you edit and proofread will help you notice and consider some of those subjective issues:

- At the word level: Am I using descriptive words? Am I varying my word choices rather than using the same words over and over? Am I using active verbs? Am I writing concisely? Does every word in each sentence perform a function?

- At the sentence level: Am I using a variety of sentence beginnings? Am I using a variety of sentence formats? Am I using ample and varied transitions? Does every sentence advance the value of the essay?

- At the paragraph and essay level: How does this essay look? Am I using paragraphing and paragraph breaks to my advantage? Are there opportunities to make this essay work better visually? Are the visuals I’m already using necessary? Am I using the required formatting (or, if there’s room for creativity, am I using the optimal formatting)? Is my essay the proper length?

Key Takeaways

- Edit and proofread your work since it is easy to make mistakes between your mind and your typing fingers, as well as when you are moving around parts of your essay.

- Trading a nearly final version of a draft with peers is a valuable exercise since others can often more easily see your mistakes than you can. When you edit and proofread for a peer, you use the same process as when you edit and proofread for yourself.

- As you are editing and proofreading, you will encounter some issues that are either right or wrong and you simply have to correct them when they are wrong. Other more stylistic issues, such as using adequate transitions, ample descriptive words, and enough variety in sentence formats, are subjective. Besides dealing with matters of correctness, you will have to make choices about subjective and stylistic issues while you proofread.

More Editing Tips

- Work with a clean printed copy, double-spaced to allow room to mark corrections.

- Read your essay backwards.

- Use spell-check and Grammarly, but be aware of each change you are making (they are not always accurate).

- Read your essay out loud.

1. Write a one-page piece about how you decided which college to attend. Give a copy of your file (or a hard copy) to three different peers to edit and proofread. Then edit and proofread your page yourself. Finally, compare your editing and proofreading results to those of your three peers. Categorize the suggested revisions and corrections as objective standards of correctness or subjective matters of style.

2. Create a “personal editing and proofreading guide” that includes an overview of both objective and subjective issues covered in this book that are common problems for you in your writing. In your guide, include tips from this book and self-questions that can help you with your problem writing areas.

The following checklist shows examples of the types of things that you might look for as you make a final pass (or final passes) through your paper. It often works best to make a separate pass for each issue because you are less likely to miss an issue and you will probably be able to make multiple, single-issue passes more quickly than you can make one multiple-issue pass.

- All subheadings are placed correctly (such as in the center or at the beginning of a page).

- All the text is the same size and font throughout.

- The page numbers are all formatted and appearing as intended.

- All image and picture captions are appearing correctly.

- All spellings of proper nouns have been corrected.

- The words “there” and “their” and “they’re” are spelled correctly. (Or you can insert your top recurring error here.)

- References are all included in the citation list.

- Within the citation list, references are all in a single, required format (no moving back and forth between Modern Language Association [MLA] and American Psychological Association [APA], for instance).

- All the formatting conventions for the final manuscript follow the style sheet assigned by the instructor (e.g., MLA, APA, Chicago Manual of Style [CMS], or other).

This isn’t intended to be an all-inclusive checklist. Rather, it simply gives you an idea of the types of things for which you might look as you conduct your final check. You should develop your unique list that might or might not include these same items.

- Often a good way to make sure you do not miss any details you want to change is to make a separate pass through your essay for each area of concern. You can conduct passes by flipping through hard copies, clicking through pages on a computer, or using the “find” feature on a computer.

- You should conduct a final overview with isolated checks after you are finished editing and proofreading the final draft.

- As you are writing, make a checklist of recurring isolated issues that you notice in your work. Use this list to conduct isolated checks on the final draft of your paper.

Complete each sentence to create a logical item for a list to use for a final isolated check. Do not use any of the examples given in the text.

1. All the subheadings are…

2. The spacing between paragraphs…

3. Each page includes…

4. I have correctly spelled…

5. The photos are all placed…

6. The words in the flow charts and diagrams…

- Content adapted from “ Chapter 8: Revision ” licensed by CC BY NC SA .

- Content from The Worry Free Writer and licensed under CC-BY NC SA.

- Content created by Dr. Sandi Van Lieu and licensed under CC-BY NC SA.

The RoughWriter's Guide Copyright © 2020 by Dr. Karen Palmer and Dr. Sandi Van Lieu is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing a Paper: Proofreading

Introduction.

Proofreading involves reading your document to correct the smaller typographical, grammatical, and spelling errors. Proofreading is usually the very last step you take before sending off the final draft of your work for evaluation or publication. It comes after you have addressed larger matters such as style, content, citations, and organization during revising. Like revising, proofreading demands a close and careful reading of the text. Although quite tedious, it is a necessary and worthwhile exercise that ensures that your reader is not distracted by careless mistakes.

Tips for Proofreading

- Set aside the document for a few hours or even a few days before proofreading. Taking a bit of time off enables you to see the document anew. A document that might have seemed well written one day may not look the same when you review it a few days later. Taking a step back provides you with a fresh (and possibly more constructive) perspective.

- Make a conscious effort to proofread at a specific time of day (or night!) when you are most alert to spotting errors. If you are a morning person, try proofreading then. If you are a night owl, try proofreading at this time.

- Reviewing the document in a different format and having the ability to manually circle and underline errors can help you take the perspective of the reader, identifying issues that you might ordinarily miss. Additionally, a hard copy gives you a different visual format (away from your computer screen) to see the words anew.

- Although useful, programs like Word's spell-checker and Grammarly can misidentify or not catch errors. Although grammar checkers give relevant tips and recommendations, they are only helpful if you know how to apply the feedback they provide. Similarly, MS Word's spell checker may not catch words that are spelled correctly but used in the wrong context (e.g., differentiating between their, they're , and there ). Beyond that, sometimes a spell checker may mark a correct word as wrong simply because the word is not found in the spell checker's dictionary. To supplement tools such as these, be sure to use dictionaries and other grammar resources to check your work. You can also make appointments with our writing instructors for feedback concerning grammar and word choice, as well as other areas of your writing!

- Reading a text aloud allows you to identify errors that you might gloss over when reading silently. This technique is particularly useful for identifying run-on and other types of awkward sentences. If you can, read for an audience. Ask a friend or family member to listen to your work and provide feedback, checking for comprehension, organization, and flow.

- Hearing someone else read your work allows you to simply listen without having to focus on the written words yourself. You can be a more critical listener when you are engaged in only the audible words.

- By reading the document backwards, sentence by sentence, you are able to focus only on the words and sentences without paying attention to the context or content.

- Placing a ruler or a blank sheet of paper under each line as you read it will give your eyes a manageable amount of text to read.

- If you can identify one type of error that you struggle with (perhaps something that a faculty member has commented on in your previous work), go through the document and look specifically for these types of errors. Learn from your mistakes, too, by mastering the problem concept so that it does not appear in subsequent drafts.

- Related to the previous strategy of checking for familiar errors, you can proofread by focusing on one error at a time. For instance, if commas are your most frequent problem, go through the paper checking just that one problem. Then proofread again for the next most frequent problem.

- After you have finished making corrections, have someone else scan the document for errors. A different set of eyes and a mind that is detached from the writing can identify errors that you may have overlooked.

- Remember that proofreading is not just about errors. You want to polish your sentences, making them smooth, interesting, and clear. Watch for very long sentences, since they may be less clear than shorter, more direct sentences. Pay attention to the rhythm of your writing; try to use sentences of varying lengths and patterns. Look for unnecessary phrases, repetition, and awkward spots.

Download and print a copy of our proofreading bookmark to use as a reference as you write!

- Proofreading Bookmark Printable bookmark with tips on proofreading a document.

Proofreading for Grammar Video

Note that this video was created while APA 6 was the style guide edition in use. There may be some examples of writing that have not been updated to APA 7 guidelines.

- Mastering the Mechanics: Proofreading for Grammar (video transcript)

Related Webinar

- Previous Page: Revising for Writing Goals

- Next Page: Reflecting & Improving

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Microsoft 365 Life Hacks > Writing > Tips for proofreading and editing essays

Tips for proofreading and editing essays

Proofreading and editing your essays before submitting them is essential. You’d be surprised how many typos and grammatical errors can go undetected by spellcheck. Learn more on how you can proofread and edit your essay to earn a higher grade.

While spellcheckers are reliable, they’re not always perfect. If you want to get the grade you deserve for on your paper, you’ll need to proofread and edit it. It’s normal to need two to three drafts (or sometimes more!) before handing in your essay. Follow these proofreading and editing tips to nail your next essay.

Write with Confidence using Editor

Elevate your writing with real-time, intelligent assistance

How to proofread and edit an essay

Re-read the prompt and requirements.

Before you pore over your essay, re-read the prompt and essay requirements from your teacher or professor. It’s easy to get carried away and go off-topic while writing an essay. It’s also easy to forget to use the right font or font size your instructor requested. By re-reading the prompt, you’ll have the requirements fresh in your mind, so you don’t lose points over preventable mistakes.

Read your essay out loud

Reading your paper aloud can help you identify choppy sentences and grammatical errors you might not have discovered if you proofread your paper silently. Make sure to read your essay out loud slowly to catch any mistakes. Once you find an error, fix it right away so you don’t get distracted and forget to fix it. You can also use the Read Aloud feature in Microsoft Word for proofreading, which will read what you’ve written out loud for you.

Read your essay from end to beginning

While reading your essay backwards might sound illogical, it’s a great way to identify spelling issues or confusing sentences. Start by reading the last sentence of your paper for errors, then move on to the second to last sentence, and so on. Reading your paper out of context can help spot any issues in your writing.

Double-check your sources

Make sure you appropriately cite all the sources in your paper. Cite your sources when you use a quote, summarize or paraphrase someone else’s idea, or share research that was conducted by someone else. Learn how to navigate different citation formats and tailor your writing to your essay’s requirements.

By re-reading your paper, you can identify sentences you may have forgotten to cite. Plagiarism can have major consequences, so avoid it at all costs.

Check the structure of your essay

An unorganized essay can feel messy and confusing. Check that you structured your paragraphs in the correct order and made seamless transitions between each paragraph. As you read through each paragraph, make sure they correspond with your thesis.

Analyze your essay’s tone

As you read through your paper, make sure the tone is formal. Scan your essay for the following examples:

- Generalizations (“all” or “many”)

- Exaggerated adjectives (“brilliant” or “genius”)

- Adverbs (“simply” or “obviously”)

- Inflammatory or emotional language (“evil” or “heartless”)

- Qualifiers (“sometimes” or “usually”)

If you find any of the above in your paper, be sure to revise: this language should be avoided in academic writing.

Take breaks while proofreading

Give yourself time to reset with a break for a few minutes (or even a few hours) while reading through your essay. You’ll pick up on any typos or issues in your paper once you return to it with a fresh mind.

Get a second pair of eyes

If you can, get a peer to review your essay. Sometimes, a third party can point out spelling errors or mechanical issues you wouldn’t have noticed on your own. They can also let you know if you accurately answered the essay prompt and made your message clear.

Proofreading and editing your essays are key to avoiding preventable mistakes and earning better grades. To continue taking your writing to the next level, check out tips for mastering the essay , brainstorming effectively , and how to build trust with your audience .

Get started with Microsoft 365

It’s the Office you know, plus the tools to help you work better together, so you can get more done—anytime, anywhere.

Topics in this article

More articles like this one.

What is independent publishing?

Avoid the hassle of shopping your book around to publishing houses. Publish your book independently and understand the benefits it provides for your as an author.

What are literary tropes?

Engage your audience with literary tropes. Learn about different types of literary tropes, like metaphors and oxymorons, to elevate your writing.

What are genre tropes?

Your favorite genres are filled with unifying tropes that can define them or are meant to be subverted.

What is literary fiction?

Define literary fiction and learn what sets it apart from genre fiction.

Everything you need to achieve more in less time

Get powerful productivity and security apps with Microsoft 365

Explore Other Categories

- ALL ARTICLES

- How To Study Effectively

- Motivation & Stress

- Smarter Study Habits

- Memorise Faster

- Ace The Exam

- Write Better Essays

- Easiest AP Classes Ranked

- Outsmart Your Exams

- Outsmart Your Studies

- Recommended Reads

- For Your Students: Revision Workshops

- For Your Teaching Staff: Memory Science CPD

- Our Research: The Revision Census

- All Courses & Resources

- For School Students and Their Parents

- For University Students

- For Professionals Taking Exams

- Study Smarter Network

- Testimonials

How To Proofread: 19 Foolproof Strategies To Power Up Your Writing

by William Wadsworth | Feb 3, 2023

by William Wadsworth

The Cambridge-educated memory psychologist & study coach on a mission to help YOU ace your exams . Helping half a million students in 175+ countries every year to study smarter, not harder. Supercharge your studies today with our time-saving, grade-boosting “genius” study tips sheet .

Proofreading: it’s the final hurdle on your race to the submission deadline, and a crucial step in creating a polished document. But how exactly do you proofread effectively and efficiently?

Whether you’re working on an essay, thesis, dissertation, research paper or article, take a deep breath. This is your one-stop “how to proofread” guide:

We’ve got 19 clever proofreading steps and strategies to take your skills to the next level and fine-tune your document for maximum marks. Because after all that hard work, don’t let careless mistakes drag your essay (and your grade!) down!

Proofreading and editing: what’s it all about?

Before we get down to those 19 strategies, what do we mean by “proofreading”?

The difference between editing and proofreading is actually pretty simple:

- Editing is a process that you begin after your first draft – it’s all about refining the quality, tone, word count, clarity and readability of your writing

- Proofreading is done to your final draft (once your content is ready, structured, signposted and feeling awesome!)

It’s all about checking that the elements of your essay or paper are consistent, presented correctly and free from errors . Think: spelling and grammar, punctuation, formatting, references and citations, figures and tables .

Essentially, you don’t want your examiner to be distracted from your winning argument by a sloppily presented document – and proofreading is the answer.

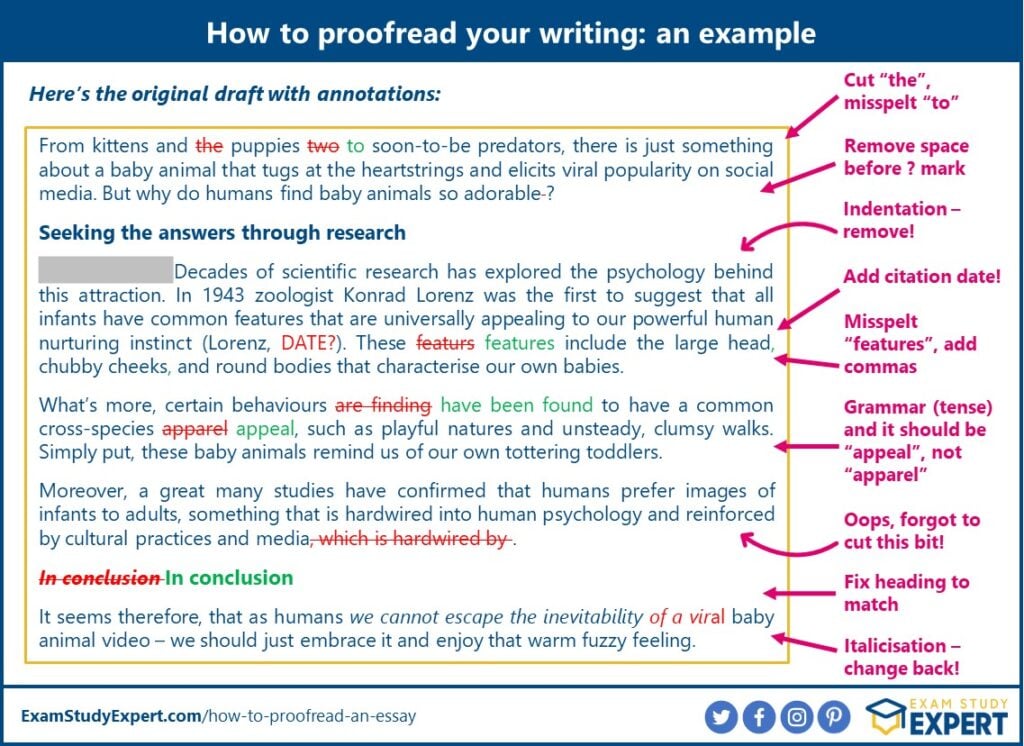

Here’s an example of the difference careful proofreading can make to your essay:

That all might sound daunting, but I promise it’s not! Especially if you work strategically and follow these 19 steps:

How to proofread: 19 killer strategies

Proofreading is a process, sure. But I don’t want you to get overwhelmed!

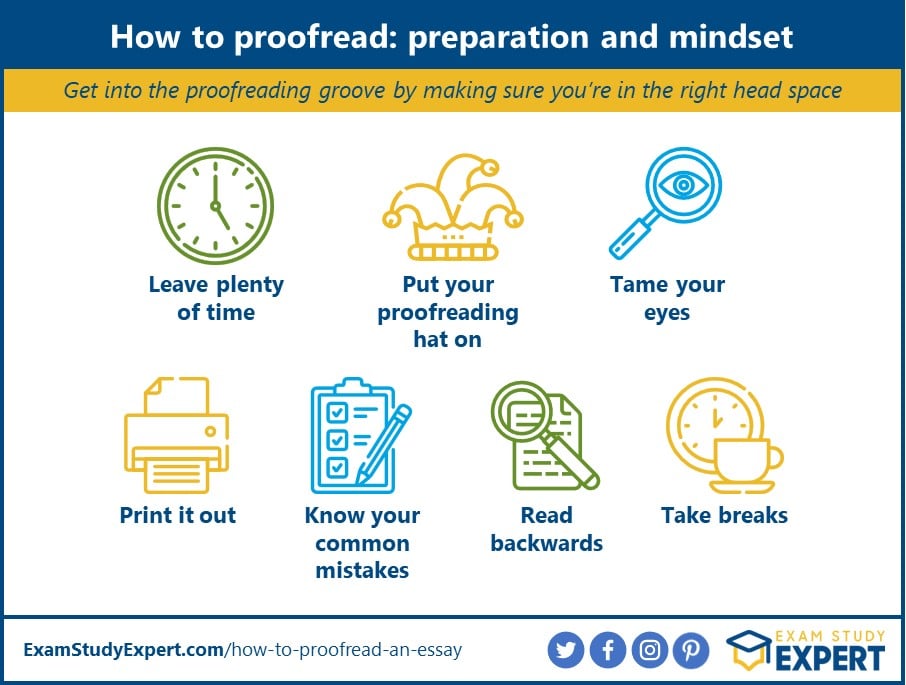

So I’ve grouped these top 19 proofreading strategies into 3 sets: preparation and mindset , checking every element , and making the most of your proofreading tools .

Part 1: Get into the groove with the right preparation and mindset

1. Leave yourself plenty of time

Hopefully you’re not reading this article the night before your deadline ( and if you are – good luck !).

Because our first proofreading strategy is all about time.

Proofreading can be a tedious process of spotting and correcting small errors – definitely time-consuming ! And the longer your essay, thesis or dissertation, the more time this process will need .

Plus, if you’re hoping for external help (whether friend or professional), you’ll need to leave them time to work too.

In my opinion, it’s best to give yourself a solid week for proofreading and corrections – if you can! That way, you’ll have time to …

2. Take a break before you start

Your brain and eyes need to be fresh if you’re going to proofread accurately.

You don’t want to be anticipating what you’ve written, rather than actually concentrating on the words on the page!

So, don’t jump straight from writing to proofreading – take a break !

If you can, take a few days away from your essay or thesis. If not, have a coffee and stroll around the block first. Get your mind clear and ready to focus.

Psst: Don’t forget to take plenty of short breaks whilst proofreading longer assignments too!

Ready? Perfect: you’ll be primed to dive into …

3. The proofreading mindset

It’s time to put your proofreading hat on!

Try and separate yourself from the “you” that wrote the essay . Try to pretend you’re marking an essay written by a friend you want to help get top marks!

Going to a different location can really help create this kind of psychological distance between “you” the author and “you” the proofreader.

If you can, move to a desk or armchair in another room, or take your essay to a library or quiet corner in your favourite coffee shop . Just make sure your environment is distraction-free – you’re going to need to concentrate!

If you really want to go to town on this, you could literally wear a different hat! It sounds silly, but when we look or behave differently, it can send powerful signals to our mind that it should be thinking differently too.

Free: Exam Success Cheat Sheet

My Top 6 Strategies To Study Smarter and Ace Your Exams

Privacy protected because life’s too short for spam. Unsubcribe anytime.

4. Print it out

This is a proofreading strategy I always do:

Many people (me included!) find it much easier to read closely when text is on a printed page rather than when it’s on a screen. So grab that stack of paper, a nice bright pen and settle into your chosen spot …

Psst : I know we all need to do our bit to keep printing to a minimum to help the planet, but when your grade is on the line, I think you can cut yourself some slack. Just make sure you recycle your printing when you’re done…

If that’s not your style, why not try reading your essay aloud to help you spot mistakes?

5. Slow down and tame your eyes

When we read, our eyes move in jumps called “ saccades ”.

Essentially, our eyes don’t focus on every single word in turn. Instead, they focus on a point only every few words, which means some words only ever appear in peripheral vision. If you read quickly, the majority of the words in your essay are only appearing in your peripheral vision.

And that means it’s easy to miss things ! Your peripheral vision fills in details and assumes correctness (especially when you’re familiar with the argument).

So, to proofread effectively, you need to force your eyes to slow down and focus on each word in turn .

Try these methods for reading slowly and systematically:

- Use your finger or a pen to trace under each word as you read it

- Or have a ruler or piece of paper to hand to move down the page, revealing only one new row at a time

You might be surprised how many more errors you pick up!

6. Read backwards

Still struggling with slowing down? Here’s one more strategy for making sure you proofread carefully:

Read your essay backwards!

That might sound tricky, but it’s actually pretty clever and simple.

Often, our brains will trick us into reading a correct spelling based on the context of the rest of the sentence, and whatever word we’re “expecting” should appear next.

Solve the issue by reading each paragraph backwards, sentence by sentence. Start from the final word of the paragraph and move in order to the first. Those misspelt words will have nowhere to hide!

Psst : This is a great proofreading tip for hand-written essays where no spell-check is available (such as in an exam), particularly if you know you’re weak on spelling!

7. Know yourself

Our final proofreading strategy to get you prepared and in the groove is this:

Make sure you’re aware of the most common errors you make all the time when writing. Why not make a list to check off!

Maybe you always misspell “theorem”, get in a muddle about when to add commas or know you aren’t consistent about using en-dashes between dates (1914 – 1919).

If you’re not sure about the correct way to do something, check the guidelines set out by your institution, ask your teacher or lecturer, or look at the style guide for your discipline (such as the Chicago Manual of Style).

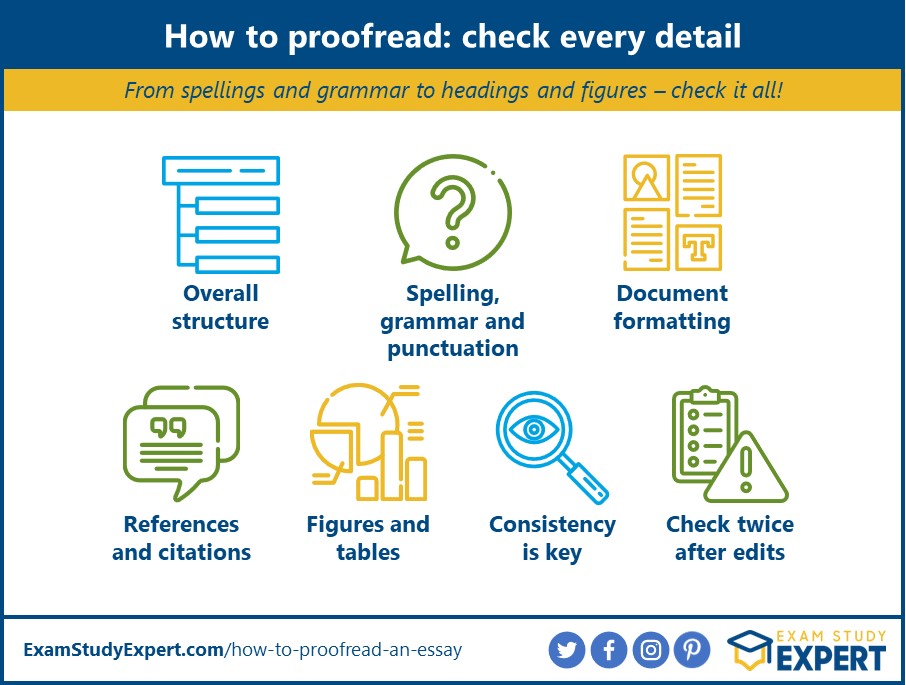

Part 2: How to proofread every element in your essay, dissertation or thesis

Feeling daunted by how many things you need to check for accuracy? Don’t be. You can do this!

Think of it a little like breaking down a big study goal into milestones : all you need is this checklist, a plan of action and a little time .

Top tip: It’s often a good idea to take several passes through your document – especially if it’s a longer essay or you know you struggle with accuracy. That way you can deal with each element individually! Pass one: headings, pass two: references and citations … and so on!

8. The big stuff: overall structure

You’ve probably done lots of editing as you’ve improved your essay or thesis, so make sure to take the time and check everything is still in the right order and place! Introduction, Part 1, Analysis … etc!

It’s so easy for cut-and-pasted paragraphs or sentences to have actually just been copied – and now exist twice! Or for edited paragraphs to end abruptly mid-sentence …

Trust me, we’ve all done it!

Adding signposting to your essay is another crucial editing step that can easily get things out of order. Plus signposting often produces in-text references that are vital and need to be correct for things to make sense to your editor! (That’s when you say “ see Section Two ” or “ as mentioned in the preceding three sections ”).

Once you’ve made sure that everything still makes sense and flows in a logical progression it’s time to move onto the little details:

9. Spelling, grammar and punctuation

The most obvious check you need to make when proofreading your essay is for mistakes in your spelling, grammar and punctuation.

Don’t forget to check that you:

- Are using the correct capitalisation of words

- For example, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) can later be referred to as the BBC

I’m not going to list every possible type of mistake you should be checking for. But here a handful of common examples to get you started with your proofreading:

- Misspellings that are real (but very different) words, e.g. field and filed . Your spellchecker won’t spot these!

- It’s and its

- You’re and your

- There , they’re and their

- Affect and effect

- Principle and principal

- Tense consistency within sentences (not switching between present and future)

- Verbs agreeing with their subjects

- Using commas and semicolons accurately

- Missing punctuation: does every sentence end with a full stop?

10. Formatting: from headers to italics

This next proofreading strategy is all about appearances.

A big part of how to proofread your essay, thesis or dissertation is getting the formatting right and consistent .

Psst: Chances are, if you’re writing a bigger assignment such as a thesis or dissertation, your institution will have provided you with a style guide that includes acceptable formatting for submission. Make it your ally!

The formatting includes lots of elements that contribute to the layout of your document:

- Are you capitalising them?

- What font and style should they have?

- Are they numbered (consistently)?

- Are you giving them indentation and/or justification?

- Are your paragraph breaks the same?

- Create your own style guide page with body, figure, heading and subheading fonts laid out!

- Are they consistent and suitable for printing and binding your thesis?

- Do your page numbers continue correctly after any blank pages?

- Are there any pages with only 1-2 lines of text? Avoid these!

- Are there rules in your discipline for how you use italics?

- Has it spread beyond the phra se you meant to italicise?

- Double spaces

- Spaces before punctuation .

- Mixing up m-dashes, en-dashes and hyphens

Make a list of the things you need to check for – especially if you spot a frequently recurring mistake!

11. References and citations

In my experience, referencing is one of those things that just makes people groan. It’s nit-picky, careful work. But worth doing right – you don’t want to plagiarism police at your door!

Proper referencing is a big part of academic writing, so make sure you’re following the correct method for your discipline. ( Ask your teacher or supervisor for advice if you’re unsure !)

When checking your references, ensure that your citations match the references in your bibliography! Any quotations should also conform to formatting and referencing rules for your field .

And don’t forget to check the little details when proofreading, for example:

- Are your author initials spaced or unspaced? (e.g. C.S. Lewis vs C. S. Lewis )

- Which date format are you using? (e.g. 27th August 1854 vs August 27th 1854 vs 27/08/1854 )

- If you have footnotes or endnotes, are your numbers all in order?

- Do you have any outdated in-text references to footnotes or endnotes?

Depending on your referencing format, it might be easier to do a separate proofreading pass through your essay to check for citation errors!

12. Figures and tables

Whether you’ve got charts, tables, figures, illustrations or graphs: don’t forget to check your captions and placement.

This is another key place where outdated in-text references might be hiding , particularly if you’ve been editing your document structure. Find where you say things like “ see Figure 6 ”: are these numbers still correct?

Don’t let errors slip through and cost you marks!

13. Check for consistency

Our next proofreading strategy is an important one!

Sometimes, you need to make stylistic decisions in your writing, and which option you choose matters less than staying consistent throughout your essay.

Remember: if in doubt, refer to any guidelines your teacher or institution have given you, or the official style guide for your discipline (e.g. Chicago Manual of Style).

Check you’re not chopping and changing between different options on issues. Here are some examples you might catch when proofreading:

- When to use ‘single’ or “double” quotation marks

- Full stops after bullets. Or not

- Are you using the US English or British English spellings of words?

- Whether you prefer – ise or – ize endings

- Is there any Technical Vocabulary that might be capitalised inconsistently?

- e.g. you might spell out “one” to “nine”, and use numerals for 10 and above

- Or your figures might use roman numbers e.g. Figure IV

- If your headings and subheadings are numbered (e.g. 1.1, 1.2), check they’re consistent, and that order is correct against the table of contents!

14. Check twice after every tweak

And finally, our last tip in this section on how to proofread absolutely everything in your essay is …

I think the single biggest thing I’ve learned about how to proofread an essay is to be super, ultra, incredibly careful about errors creeping in after editing .

You know how it goes: you’re on your final proofread before submission, and you spot a clunky sentence that could be tidied up with a little rewrite. You make the change, but don’t check it properly, and leave a fresh mistake in your work.

By all means, make a small tweak here and there in the proofreading phase, but make sure you check the amended paragraph at least twice afterwards!

If you find you’re making a lot of major edits, pause the proofread phase entirely to give your essay a round of editing. Only return to proofreading for accuracy once you’ve done all your edits .

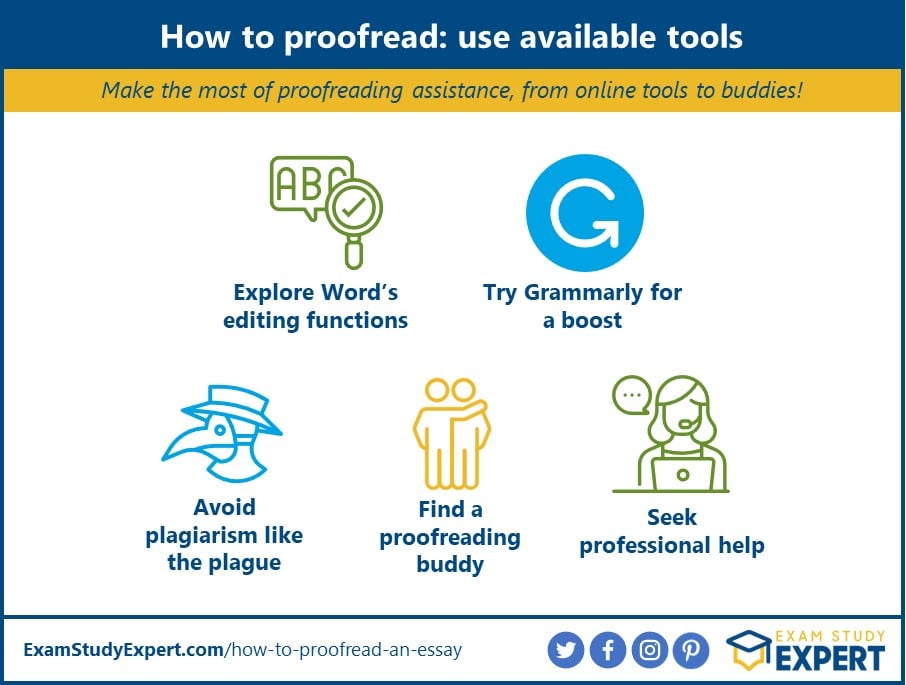

Part 3: Make use of available tools

The third and final set of “how to proofread” strategies is all about making use of the tools available to you. And trust me, when it comes to proofreading, there are plenty of services, websites and plugins and even Word functions you can use to make your life easier!

15. Get the most out of Word’s editing functions

If you’ve typed your essay or thesis in Word then you’ve got plenty of proofreading firepower at your fingertips!

And it’s not all about those handy grammar and spellcheckers either – although they are a great place to start:

- Remember: they’ll catch some (though not all) mistakes. Homophones and misspelt words that are still real words – definitely weak spots and up to you to catch!

- Not every detected “error” actually is a mistake: you’ll sometimes need to use your judgement

So how else can Word help you to proofread thoroughly?

- Setting your language correctly can be a big help to the spellchecker’s effectiveness – US and UK English have plenty of subtle differences!

- The Navigation bar is also a handy place to count through numbered headings and make sure you don’t have Section 1.1 twice!

- Making your own style guide page can be a big help in seeing how it all looks and works together

- If you have a friend helping you to proofread – or if you’ve just got your proofreader hat on – the “Track Changes” and “Comments” features can be a great assistance when it comes to actually making all the tiny corrections!

16. Get proofreading with Grammarly

Another great online tool to assist you with proofreading your essays and dissertations – in fact, any piece of writing! – is Grammarly .

I’ve recently added Grammarly * to my writer’s arsenal and wish I’d done it years ago. It’s a proofreading strategy I definitely recommend.

It acts like a turbo-charged version of the standard Word grammar and spellchecker, helping me catch a much broader range of mistakes.

The ability to set your audience, level or formality and language ( academic, email, casual etc ) is a great feature that helps with any awkwardness of writing in a more formal academic style.

Honestly, it’s not perfect and will often flag perfectly correct words and phrases as errors. But I’d much rather that way round than it missed out on flagging potential errors to me.

Plus – it’s free to create an account! I’m using the pro version now as writing is such an important part of my life, but even Grammarly’s free version * is a big improvement when it comes to proofreading your essays and theses.

17. Avoid plagiarism like the plague

You don’t want to be caught copying others’ work.

Universities and Colleges often run essay submissions through tools like Turnitin which will put a big red flag against essays with too high a percentage of text which matches source material online.