- EXPLORE Random Article

How to Write a CCOT Essay

Last Updated: March 31, 2023 References

This article was co-authored by Jake Adams . Jake Adams is an academic tutor and the owner of Simplifi EDU, a Santa Monica, California based online tutoring business offering learning resources and online tutors for academic subjects K-College, SAT & ACT prep, and college admissions applications. With over 14 years of professional tutoring experience, Jake is dedicated to providing his clients the very best online tutoring experience and access to a network of excellent undergraduate and graduate-level tutors from top colleges all over the nation. Jake holds a BS in International Business and Marketing from Pepperdine University. This article has been viewed 160,366 times.

The Continuity and Change-Over-Time (CCOT) essay is a type that is commonly used on the AP World History exam, but you may be asked to write one for other settings or courses. Basically, it asks you to think about how a particular subject has developed or altered over time, as well as to consider what about it has stayed the same. Writing one is a piece of cake if you practice, organize your thoughts before you start writing, and keep the basic requirements of this essay type in mind as you work.

Gathering the Information you Need

- For example, a prompt might ask you to “Evaluate the extent of continuity and change in the lives of European immigrants in the United States between 1876 and 1918."

- A thesis might look something like “While the United States maintained its position as a manufacturing superpower in the first five decades after WWII, over time its focus shifted from the production of traditional goods to the creation of innovative electronics.”

- Your thesis must specifically mention the time period. [2] X Research source

- Be as direct as possible about the continuity and change over time.

- Jot down the basic facts you know about the topic, as well as any key details that stick out in your mind. Build your essay around these concrete details.

- For example, if your topic asks you to consider the development of manufacturing in the United States after WWII, start by writing down what you know about industries during that time period. If you know particular details about developments in the auto industry, you might work with those above all.

- For instance, if you are writing about changes and continuities in manufacturing after WWII, you might argue that the Vietnam War and the fuel crisis of the 1970s decisively changed the shape of American industries.

- Create a timeline of events to sort out your historical information in order and help identify the turning point.

- Continuing with the manufacturing example, your might keep in mind that the fuel crisis of the 1970s led to a rise in imported, fuel-efficient cars, which impacted the auto industry in the United States.

Organizing and Writing Your Essay

- Create an outline to serve as the framework for your essay.

- For example, you might have a first paragraph that establishes your thesis and the conditions at the start of the time period. This could be followed by two paragraphs on changes that occurred over time. Finally, the essay could close with a paragraph on what stayed the same.

- Be selective and organize your thoughts. Don’t just dump out everything you know about a subject.

- Stay in the place and time relevant to the prompt. If a prompt asks you to think about the development of manufacturing in the United States, your evidence shouldn’t be based on examples from manufacturing in China.

- On the other hand, don’t forget to explain the global significance of your topic. For instance, at some point in your essay, you might note that changes in manufacturing in the United States led to an increasing rise in imported home goods manufactured in China.

- If you get stuck, go back to the notes/ideas you had about the turning point, since this can show you exactly what changed, when, and why.

Preparing for the Exam

- 1 point for having an acceptable thesis

- Up to 2 points for addressing all parts of the question

- Up to 2 points for effectively using appropriate historical evidence

- 1 point for explaining the changes in terms of world history and global contexts

- 1 point for analyzing the process of continuity and change over time

- For example, including several relevant examples of changes and continuities will help you earn points in the Expanded Core.

- You cannot earn points in the Expanded Core unless your essay already covers all aspects of the Basic Core.

- Don’t use evidence from the wrong time period. Using the example of Captain Cook won’t help you if the essay asks you to examine continuities and changes in work exploration between 1400 and 1700.

- Avoid vagueness of dates. Don’t write an essay that discusses “exploration before the eighteenth century.” Instead, tell your readers that your essay will discuss changes and continuities from 1492 (Columbus’ first voyage) to Hudson’s voyage of 1609-1611.

- Don’t just dump as many facts as possible into your essay. Organize and analyze all information you include, making sure it is relevant.

Community Q&A

- If you are writing a CCOT essay for a class, always ask your teacher for advice. He or she may have specific expectations for the essay that may differ from these general guidelines. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- If you can't spell a word, choose another one. Although spelling mistakes and grammar errors would not deduct points, poor spelling can cast a shadow on the rest of your essay. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Avoid cursive, especially if your handwriting is messy, as it may be harder for the AP essay readers. Don't have too many scribbles on the paper, for they may make it harder for the grader to read. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Keep an eye on your time. You do not want to spend too much time on this one essay, running out of time on the rest. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

Other wikiHows

- ↑ http://www.utdallas.edu/apsi/documents/cone-2016.pdf

- ↑ http://highered.mheducation.com/sites/dl/free/0024122010/899891/AP_World_History_Essay_Writers_HB.pdf

- ↑ https://gibaulthistory.files.wordpress.com/2011/04/possible-ccot-essay-structures.pdf

- ↑ http://apcentral.collegeboard.com/apc/members/courses/teachers_corner/40896.html

- ↑ https://secure-media.collegeboard.org/digitalServices/pdf/ap/apcentral/ap15_world_history_q3.pdf

- ↑ http://worldhistoryconnected.press.illinois.edu/6.2/cohen.html

About this article

Reader Success Stories

Apr 13, 2018

Did this article help you?

Jo'Nique Robinson

Jan 18, 2017

Sep 24, 2018

Chris Kiyota

Oct 25, 2017

You Might Also Like

- About wikiHow

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Find what you need to study

Continuity and Change Over Time in the AP Histories

24 min read • may 15, 2022

William Dramby

The one thing you need to know about this historical reasoning skill:

College Board Description

Reasoning processes describe the cognitive operations that students will be required to apply when engaging with the historical thinking skills on the AP Exam. The reasoning processes ultimately represent the way practitioners think in the discipline. Specific aspects of the cognitive process are defined under each reasoning process.

Identify patterns of continuity and/or change over time.

Describe patterns of continuity and/or change over time.

Explain the relative historical significance of specific historical developments in relation to a larger pattern of continuity and/or change.

Organizing Question

How have individuals and societies changed over time and how have they stayed the same? Why?

Continuities and Change Over Time

How have you changed since you were younger? This is a pretty easy question. You have physically grown, you matured both academically and socially, and you found new hobbies, interests and activities that are age-appropriate. Historians look for change over time. We look for how societies became wealthier, how empires fell, and the roles of different social groups changed.

However, how have you stayed the same since you were younger? Asking about continuities in your personality and your life is harder. Continuities are not as obvious. Some still have a love for Star Wars movies while others will always want to play a pick-up game of basketball. Historians look for continuities over time. We look for how religion continued to play a role in peoples’ lives, how societies continued to be patriarchal, and how ideas like liberty and freedom persist.

When students study world history, they study the changes and continuities over time (CCOT). AP World History has had a rich history of asking students to write CCOT essays and use the skills in attacking stimulus-based multiple-choice questions.

Period 1 (1200 to 1450)

1200-1450 changes.

⚡ Increase of trade along the Silk Road because of Mongol conquests and because of new stable powers

The Mongols were a nomadic tribe originating from modern day Mongolia who quickly spanned across nearly all of Eurasia, stretching from the Middle East to the eastern coast of China. In fact, the only places that were successful in fighting off the Mongols were Japan (who were aided by frequent typhoons) and India. Though short lived, an important effect of the Mongol Empire was the reunification of the Silk Roads. Prior to 1200, the Silk Roads were generally dangerous and not as prosperous as growing sea trade like in the Indian Ocean. However, the Mongols unified the Silk Roads and made it safer and easier for them to navigate.

The Mongols created Pax Mongolica or Peace of the Mongols. Trade was protected from the Mediterranean to the South China Sea. Cities like Samarkand emerged built upon trade and routes like the Trans-Saharan and Indian Ocean Trade Networks were all linked.

⚡New technologies spread like astrolabe and magnetic compass increasing exploration and trade

As empires like the Abbasid Caliphate grew across the Middle East and China grew in East Asia, new technologies were created explicitly for the functions of trade and navigation. The astrolabe , created in the Islamic World, aided travelers in using the stars to navigate (Fun fact, you can still buy astrolabes today! Though they are a bit pricey).

The Baghdad House of Wisdom is a famous example of academics and intellectualism in Dar-al-Islam, such as new innovations in algebra and trigonometry. Similarly, Song China saw a boom in innovation and new products. New forms of paper grew, leading to flying money , which we’ll discuss later, and most importantly the magnetic compass became a commonly used navigational tool.

Maritime trade growth during the period 1200 - 1450 fueled most of the technological innovation. New boats became widespread along sea trade routes. Arab dhows were ships with triangular lateen sails that were widespread in the Islamic world. Similarly, Chinese junks were small ships that traveled west from China.

⚡Buddhism spread and morphed from Northern India to Tibet, China, Southeast Asia, and Japan

Though it started in Northern India around 600 BCE, Buddhism eventually spread over the Himalayan Mountains traveling along trade routes and by various missionaries to other Asian lands. However, each region will impact the eventual form of Buddhism thus Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana Buddhism emerge.

Many comparisons can be drawn between Buddhism and Christianity, which are both religions that spread throughout this period. For example, Christianity is a proselytizing religion, which means it seeks out converts, whereas Buddhism is not. Buddhism and Christianity also both saw significant cultural diffusion and cultural blending during this time period.

⚡The Aztecs and Inca emerged as large empires in Mesoamerica and South America, respectfully

Before their eventual conquest by the Spanish Conquistadors, the Aztecs and Inca were large, thriving empires that united the peoples of Mesoamerica and South America politically, economically, and socially. While the Aztecs and Inca empires were large, complex political structures that we cannot do justice in just a few short paragraphs, there are some must-know things about the Aztecs and Incas.

The Aztecs are known especially for their architecture, such as pyramids and sacrificial/monumental architecture. They also had chinampas , large island-like farmlands that floated on water. Politically, the empire used the tribute system , where smaller conquered areas paid tribute for protection.

The Incas used the mita system , a system established by the Inca Empire in order to construct buildings or create roads throughout the empire. It was later transformed into a coercive labor system when the Spanish conquered the Inca Empire. They’re also well known for their terrace agriculture such as the stunning Machu Picchu .

⚡ Economic powers emerged like Mali Kingdom and Delhi Sultanate

Regions that lay outside Christiandom and Dar al-Islam are uniting politically, economically, and socially. The Mali Kingdom and Delhi Sultanate were both wealthy and powerful empires that saw Islam as a uniting factor.

In fact, Mali was one of the most wealthy nations in all of history, with Mansa Musa , a Mali king, being the most wealthy person in all of human history. Mali and it’s capital city Timbuktu unified the Sahara and created the Trans-Saharan Trade Route.

⚡ Trade saw new economic and financial developments

As a result of the growth of interregional trade, new financial tools were created to aid in the transfer of goods across borders. Paper money , nicknamed “flying money” was a new innovation that came from China. Further, credit became a new tool of borrowing money that aided in financial asset growth.

1200-1450 Continuities

🔗China continued to be largely a Confucian society

Confucianism has had a large influence on the culture of China since before the Qin Dynasty. Between its influence on social structure such as filial piety and political structure such as the Five Relationships, no other philosophy has so impacted China. Confucianism emphasized education and a strong bureaucracy for the Chinese government, leading to a unique political structure.

The Civil Service Exam system from the Qin Dynasty was strengthened in Tang / Song China enabling a bureaucracy built on merit and not necessary hereditary lines to develop. However, while meritocratic in theory , wealth allowed people to get tutors and special classes to learn the tests, leading to social stratification still.

🔗Patriarchy remained a strong social force across the globe

Throughout history, one of the most consistent social forces has been patriarchy . In this time period, despite there being some advances in women’s rights, specifically in the Islamic world, patriarchy continued to place men above women in the social pyramid.

Patriarchy is one of the most important continuities throughout history, and will follow social structures not just in the post-classical era, but in essentially every part of history that you learn.

🔗Trade continued to be the primary form of economic interaction

Trade saw many changes during this time period, as we’ve outlined above, but nevertheless, comparing the post-classical era to the classical era, trade continued to form the basis.

Period 2 (1450-1750)

1450-1750 changes.

⚡ Western Europe faced the Protestant Reformation seeing the rise of regional Christian churches and the power of the Roman Catholic Church decrease

Martin Luther challenged the role of the Roman Catholic Church in Christianity. He promoted a more personal relationship with God and the word . From his 95 Theses , will come a radical shift in European Christianity. Luther found the Catholic policy of indulgences to be the primary signal of corruption within the church, along with a host of other issues.

New Protestant Churches emerger like the Lutheran and the Church of England while religious wars also inflame France and Germany. Other churches and sects of Christianity, like the Calvinists, will see expansions into the Americas in the 1600s. Religious wars like the Thirty Years’ War sprung up across Europe as well.

⚡ Weakening of the Roman Catholic Church occurs throughout this era with the Reformation, Scientific Revolution, and Enlightenment increasing the popularity of humanism and empiricism

The Protestant Reformation was aided by the Scientific Revolution , a movement that helped spawn higher intellectualism in Europe (though it must be noted that many of the discoveries of the Sci. Rev. either had been discovered or were aided by discoveries that had been made in the Islamic World in previous years). Important developments were advancements in physics, biology, and the development of the formal scientific method . Scientists like Copernicus and Galileo were important astronomers who helped prove astronomical facts regarding orbits.

The Enlightenment came a bit after the Scientific Revolution, with the Enlightenment being more of a philosophical movement rather than strictly a scientific one (though science was still part!). The Enlightenment brought with it many philosophies that we still reference today such as capitalism , formally coined by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations , and new political theories like the separation of powers (Montesquieu), the social contract (Rousseau), and natural rights of life, liberty, and property (John Locke). The Enlightenment marked a shift in philosophy from religiosity to more of a secular form of thinking such as rationalism and empiricism .

⚡ Islamic world of Dar al-Islam expanded into large land-based empires that stretched from Europe through South Asia converting people, increasing trade connections, and forming new syncretic beliefs

The Ottoman Empire, Safavid Dynasty, and Mughal Empire all developed strong land-based empires that brought people of different languages and faiths together while also strengthening their unity under Islam. The spread of these empires was very much so due to guns , which were a new invention created after the creation of gunpowder in Song China. For example, the Ottoman Empire was able to blast through the walls of Constantinople to easily take over in 1453.

These empires developed complex political and social structures such as the Devshirme system that created janissaries . This system took Christian boys, converted them, and turned them into a large fighting force for the Ottoman Empire. An important comparison to make is religious. The Ottoman Empire was mostly Sunni Islam, the Safavids were Shia Islam, and the Mughals were Sikhism, a syncretic religion that blended Hinduism and Islam. These empires commonly fought and competed for power, such as in the Battle of Chaldiran . Chaldiran cemented Ottoman rule over eastern Turkey and Mesopotamia and limited Safavid expansion mostly to Persia.

⚡ Major powers in the Americas, like the Iroquois, Aztec and Inca, are conquered by Europeans and led to new labor and economic systems

Beginning with Columbus in 1492 and eventually with Cortez and Pizarro, the American indigenous people were conquered by the French, English and the Spanish. Jared Diamond points out in Guns, Germs, and Steel that the Natives lacked the technology and ability to defend from disease to effectively fight back. New labor systems began to be used, some coerced, such as the encomienda and mit’a systems and eventually the use of chattel slavery , with the first slaves landing on the mainland Americas in 1619. African slaves and Native Americans were used primarily for the cultivation of cash crops , which were able to be made the most profitable crops on Earth. These crops, such as sugar led to new emphasis on coerced labor.

⚡ The Atlantic System will see trade increase between the Americas, Europe and Africa and will cause increase in slave trade, especially African corvee slavery

With the introduction of sugar cane to Brazil and the Caribbean, a new trade system emerges. Africans were ruthlessly brought from Africa to be slaves in the Americas where they were used to harvest sugar cane. The sugar, molasses, and rum made from the sugar cane in North America is then sold to Europe for manufacturing. These finished goods, like guns, were traded for slaves with the coastal slave kingdoms in Africa. This system is known as the triangular trade and forms the primary economic systems in this time period.

⚡ The Columbian Exchange will see the movement of food, animals, people, and disease.

The Columbian Exchange was arguably one of the most important events of not just this time period, but in all of world history, and is a term you MUST be familiar with. The Columbian Exchange describes the diffusion of people, food, animals, and notably disease across the Atlantic Ocean both from Europe to the Americas and from the Americas to Europe. Some important things that transferred were smallpox , which killed off some 90% of the Native population, horses , which became a staple in the Americas, cash crops like sugar and tobacco , and then from the Americas, potatoes, which increased the nutrition and lifespan of the average European.

The Columbian Exchange connected the Eastern and Western Hemispheres and created a formally globalized world. The Columbian exchange single handedly caused many of the changes we’ve discussed.

⚡ Maritime empires emerged as the Portuguese and Dutch created port city empires and the French and British developed large colonies around the world Mercantilism and capitalism emerged as states, businesses, and individuals sought wealth by conquest and new forms of business ventures like joint-stock companies

Unlike the mostly land based empires of the post-classical era, the early modern era was marked by maritime empires, that is, empires that were spread overseas. These typically had imperial metropoles in Europe, such as the British Empire, which had colonies in the Americas and India, the Dutch Empire, that had territory in India and the Philippines, and Portugal and Spain, which had had territories in what is today Latin America.

These empires consolidated power and developed strong economic and financial tools such as joint-stock companies to grow. Companies like the British East India Company and Dutch East India Company became some of the largest companies on earth. Mercantilism became the name of the game economically speaking

⚡ New social structures emerged in Latin America as Spanish, Native Americans, and Africans of pure and mix-blood formed new social castes

The casta system saw Peninsulares (European-born Europeans), Creoles (American-born European descent), Mestizos (Mix European-Native), Mulatoes (Mix European-African), Natives , and Africans hold a strict socio-economic order based on the level of mix-blood. This was the first time in history that a social order was created strictly based off of race. This created a paradigm that continued through nearly all of world history from this point on.

1450-1750 Continuities

🔗Western Europe continued to be largely Christian with powerful monarchies

Though the Roman Catholic Church’s power diminished, Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant Christians continued to be active members of society. In general, Europe will see Christianity rule as the reigning religion, and Catholicism will see power ebb and flow throughout this time. Of course, there were some challenges to religion, especially in the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment, but overall religion will still play a HUGE role in the lives of Europeans.

🔗Land-based empires dominated much of this era from Qing China, Mughal India, Safavid Persia, Ottoman Middle East, and Russia

The new technologies like gunpowder and the unifying force of religion allowed these societies to create empires over vast-areas and for hundreds of years. Though there was conflict, this era can also be measured by the stability of the states. Land empires, despite the growth of maritime empires, continued to have power. The Russian Tsarist Empire grew into the largest land empire in this time period, even going through westernization through Peter the Great . These empires will play a large role in expansion and imperialism in the next time period.

🔗Most societies continue the tradition of patriarchy politically, economically, socially, and culturally.

The Ottoman Janissaries were men, the Qing scholar-gentry were men, and the House of Lords in the English Parliament were men. Though some opportunities existed for women to earn economic and political power, it lacked any sort of consistency.

Period 3 (1750-1900)

1750-1900 changes.

⚡ The Industrial Revolution begins in Western Europe and spreads around the world by 1900

England, with its navigable rivers and wealth of coal deposits, was first to experience the Industrial Revolution. Naturally, Western Europe and the United States also began to thrive because of their connection to the Atlantic trade network. However, empires like Russia, Japan, Ottoman, and Qing were forced to industrialize in order to continue to be politically and economically relevant.

Between the 1700s and mid to late 1800s, the first Industrial Revolution focused on steam power (see Watt’s steam engine from the 1770s) and the transition in economics based around the cottage industry to a new use in factories and mills based off of rivers. Industrialization led to new economic theories such as laissez-faire capitalism and Marxism . Through the first Industrial Revolution, new social classes such as the middle class and industrial working class developed. Governments took specific roles in industrialization as well, such as the Meiji Era changes in Japan and Westernization efforts to avoid imperialism such as the Tanzimat Reforms and Self-Strengthening Movement .

The second Industrial Revolution focused on steel, chemicals, electricity, and precision machinery. Processes like the Bessemer process led to the growth of technology like railroads, mass manufacturing, automobiles, and the assembly line. Social stratification became a significant issue during this time as well.

⚡ The Industrial Revolution causes increased urbanization and diverse economic classes stratification

Cities like Birmingham, England were very attractive to those looking for non-skilled work. As wealth increased its impact on stratification , religion decreased its role. Working class and middle class families living in a city had opportunities for economic advancement, though slow, compared to the rural peasant / farmers. Socioeconomic movements such as Marxism grew, noting social inequities as a result of capitalism and industrialization.

Cities, while growing, were often dangerous and dirty for the lower classes. For example, London was a smog filled, dirty city that was riddled with political corruption and social stratification between the rich and the poor.

Unionization also became a key staple of urban areas as skilled workers formed unions to protect themselves from unfair policies. For example, the Industrial Workers of the World and American Federation of Labor became large groups that promoted better conditions for workers. They helped to lead to higher wages, better working conditions, and better hours for workers.

⚡ Corvee slavery and serfdom will decrease their role in the Americas and Russia, respectfully

Paid labor was cheaper than maintaining room and board for slaves and serfs and the urban impact of industrialization meant that a constant flow of cheap labor can easily be tapped. As the world transitioned from an economy surrounded by cash crops and mercantilism to a capitalistic industrial world, paid skilled workers became a more effective form of labor as opposed to slaves and serfs who mostly worked in agriculture.

Furthermore, as the Enlightenment spread, slavery and serfdom became seen as immoral in general, with slavery being abolished across most of the world by 1900 and serfdom being abolished from Russia

⚡ Enlightenment thought and fragile social orders will lead to independence movements throughout the Americas and nationalist movements in Europe

Through European colonial powers and merchants, the Enlightenment found their way to the Americas as most of these people became independent by the early 1820s. Revolutions inspired by the Enlightenment became a key sequence of events during the period 1750 - 1900. Specifically, the American Revolution marked the first major revolution that occurred through Enlightenment principles. This quickly led to revolutions in France starting in 1789 and Haiti between 1800 - 1803. Revolutions in Latin America led by Simón Bolívar led to many new independent states in Latin America. Documents such as the Declaration of Independence , Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen , and the Jamaica Letter

⚡ Nations began expanding more than ever through the process of imperialism

While nations had been expanding from Europe since the Columbian Exchange, industrialization led to a stronger form of territorial imperialism , especially in Africa and Asia. The Berlin Conference of 1884 had Europeans split up Africa into pieces to use for raw materials and access to more markets (M&Ms). Africans were mostly abused for labor, such as in the Belgian Congo , where Africans who did not collect enough rubber had their hands amputated.

To justify imperialism, nations used philosophies such as social Darwinism and the idea of the White Man’s Burden (see Rudyard Kipling’s “White Man’s Burden”). These racist ideas put down imperial subjects and justified mistreatment as helping them. Political comics from this era, such as the soap advertisement below, portrayed this.

Reactions to imperialism were many, such as the Tanzimat Reforms and Self-Strengthening Movement in the Ottoman Empire and Qing China. Revolts such as the Sepoy Revolt and the Ghost Dance occurred as well, though many times they were violent and unsuccessful. Wars such as the Anglo-Zulu War and the Boer War also occurred.

1750-1900 Continuities

🔗Monarchies continue to play a role around the world

Though the British and French monarchies saw their power decrease and the Americas tended to stay away from hereditary claims, Russia and Japan continued to solidify their power with strong monarchies. Power structures in the modern era typically were marked by either monarchies or emperors, with constitutional monarchs coming in through revolutions. Monarchies in Europe such as that under Queen Victoria in England and King Leopold II in Belgium played roles in expansion under imperialism. Imperial powers such as the Ottoman Empire and Qing China still had emperors as well. Democracy, however, saw spreads throughout this time period.

🔗Even with challenges to the norm, most societies continued the tradition of patriarchy politically, economically, socially, and culturally

Women were gaining economic opportunities in many western nations however traditional lacked the ability to vote or hold a high office in the church. Voting rights are still limited to land-owning males in nations that have not seen an increase in the middle-class while women’s suffrage comes in the 20th Century. Feminist movements led by people like Mary Wollstonecraft in the early part of this period and Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Olympe de Gouge by the end leading into the 20th century did occur, though they did not see much significant success until the 20th century.

🔗Raw materials such as spices, cotton, and coal continue to play a large role in domestic, regional, and global trade

As imperialism and industrialization took hold during this time period, raw materials continued to be a significant area of trade and production.

Period 4 (1900-Today)

1900-today changes.

⚡ Rapid advances in science lead to new medicines spreading (polio vaccine), new communications (Internet), new sources of power (nuclear), and new transportation (planes)

Science, now with government and religion, was a driving force of change in human society. The birth control pill allowed family planning, the Internet changed the purchasing process, and the world is more globalized than it has ever been. Medical advancements such as vaccines and by the 1970s the eradication of smallpox led to overall higher global life expectancies. Technology also brought with it new forms of communications like the aforementioned internet, along with telephones , radios , and televisions . Disease played a large role in this time period. Diseases associated with poverty such as malaria and TB persisted, but diseases associated with lifestyles such as Alzheimer’s, diabetes, and heart disease grew.

⚡ Green Revolution and commercial agriculture will allow a population explosion and largely eradicate extreme hunger

The Green Revolution was a process by which new technology was implemented to boost food production. It is marked by a use of biological and organic methods to boost food production such as genetically modified organisms ( GMOs ). GMOs plants, animals or microorganisms whose genetic material has been altered in a way that does not occur naturally. They were used to boost production and help food production rise during this time period. The Green Revolution brought up concerns about global climate change and the relationship between humans and the environment.

⚡ Environmental concerns increase as the developing world industrializes, agri-business use more land, and the global population increases

As scientific technology, especially technology related to farming and agri-business, humans began breaking down the environment around them, leading to things like global climate change and desertification . Deforestation also became a significant concern as humans continued to cut down forests, especially in the Amazon Rainforest, to attain more land for development. Rainforests being removed for grazing, pesticides poisoning crops and bee populations shows the challenges humanity has with the science it created.

⚡ Globalization seen in various forms like trade (multinational corporations like Coca Cola), epidemics (1918 flu, ebola, AIDS), and immigration of people and ideas

Globalization refers to the technological, political, economic, financial, and cultural exchanges between peoples and nations that have made and continue to make the world a more interconnected and interdependent place. Globalization is an important development that changed essentially everything about the world during this time period. Prior to the 20th century and the global conflict that came with it in the first half, the world, while certainly connected, was still mostly split into individual nations that did not work together on a large scale. As communication increased in the 20th century, globalization became the name of the game.

Economically, multinational corporations became commonplace, such as Coca Cola, or Nike. Economic and political organizations such as the United Nations , World Bank , IMF , and many others popped up as global entities that helped run the entire world. Free trade deals and international trade agreements such as NAFTA , ASEAN , and the European Union . However, there have been negative effects of globalization, such as a separation of the First World , such as the USA and Western Europe, and the developing Third World , sometimes also described as the Global South , in which there is a larger economic disparity between rich and poor countries. Globalization has also brought with it dissemination of epidemic and pandemic diseases such as the 1918 Influenza Pandemic , the Ebola Epidemic , AIDS Crisis , and most recently, the COVID-19 Pandemic .

Culturally, new global pop culture grew, such as reggae , bollywood , the olympics , and the World Cup . People conceptualized society and culture in new ways; rights-based discourses challenged old assumptions about race, class, gender, and religion such as global feminist movements and negritude .

Transnational movements also grew, such as the Quebecois movement in Canada, and Pan-Arabism and Pan-Africanism in Africa and the Middle East.

⚡ Older land-based empires like the Ottomans and Qing Dynasty collapsed.

The Ottomans, the once powerful trading center and Islamic hub, fell as it failed to progress successfully. Following World War I, it quickly fell and under Mustafa Kamal Ataturk, it became Turkey . For years prior, the Ottoman Empire had been named the “sick man of Europe” and despite the Tanzimat Reforms helping somewhat, by taking the side of Germany in the first World War, they quickly dissolved into Turkey.

After thousands of years of imperial rule and dynastic succession, the last Chinese dynasty, the Qing fell in 1911 in the Xinhai Revolution to a nationalist uprising led by Sun Yat-Sen and Chiang Kai-shek. Quickly thereafter, the Kuomintang, or Chinese Nationalist Party rose to power and ran the country until 1949, when Mao Zedong helped form the Chinese Communist Party and take over China.

⚡ Decolonization will see freedom and conflict emerge in nations.

One of the most important aspects of the 20th century was the process of decolonization , in which countries across the globe broke free of their imperial owners and became independent nations. Most notably, decolonization in the 20th century took place in Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia.

In Africa, decolonization was widespread. In North Africa, such as in Algeria , decolonization was met with violence and the death of 140,000 Algerian soldiers. Elsewhere, decolonization was negotiated, such as protests against apartheid until South Africa’s independence in 1994 under Nelson Mandela . Similarly, after World War II, French West Africa split into many nations such as Guinea, Senegal, Côte D’Ivoire, and Niger.

India is an important example of decolonization that you must know. Led by Mohandas Gandhi and Muhammad Ali Jinnah , India gained its independence through civil disobedience such as the Salt March. However, after succeeding in their goal, Jinnah and the Muslim League , split off into the state of Pakistan , in which heavy border disputes ensued.

In Southeast Asia, the most significant decolonized states were Vietnam and Cambodia . In Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh led a violent revolution to overthrow the French, with the French finally losing at Dien Bien Phu. Vietnam quickly became communist and split into South Vietnam and North Vietnam, and the Vietnam War soon followed as part of the Cold War. Cambodia similarly formed a Marxist state and under Pol Pot , the Cambodian Genocide took out any signs of intellectualism.

⚡ Global conflicts over land and political ideologies increase in the first half of the 20th Century

The first major global conflict to occur in this time period was the First World War . After the killing of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the Triple Alliance and Triple Entente quickly caused the war to escalate from a regional crisis to a world wide war. WWI had MANIA causes: (List Mania Causes). The First World War ended in November of 1918 after the Third Battle of Picardy and the signing of the Treaty of Versailles , which blamed Germany and charged them massive war reparations. World War I also saw new forms of war such as trench warfare and the use of chlorine gas by the Germans.

Following World War I, the interwar years saw massive debt and inflation on the German side caused complete economic collapse. This, compounded by the Great Depression in 1929, contributed to the rise of Adolf Hitler in 1933 and the German invasion of Poland in 1939 and the start of World War II. World War II was another major global conflict that involved the Allied Powers and Axis Powers and ended with another German defeat in 1941 after the Battle of the Bulge.

World War II similarly saw the beginning of genocides , the systematic murder of a race of people. Global genocides were relatively common during the 20th century, beginning with the Armenian Genocide during World War I

1900-Today Continuities

🔗The process of Westernization continues outside Europe and the United States to Japan, South Korea, Russia, India and beyond

Bollywood emerges as a center for movie making while pop-stars from South Korea thrive in the global market, and cities like Tokyo, Japan look just like New York City with their lights and sounds.

🔗Economic globalization that started with the Silk Road continues on land, sea, and air

Cotton from Georgia is shipped to Bangladesh to be made into a shirt which is then shipped to Hondars to be printed on and then back to the US for retail sail. Hands from three continents played a role in a simple shirt finding it cheaper to move the materials around than find one location to produce the whole item.

Patriarchy and racist beliefs, despite seeing vast improvements, still exist

Full Course Review for AP World History

Watch the AP World History 5-Hour Cram Finale for a comprehensive last minute cram session covering the entire WHAP curriculum including every unit, every time period, and every type of question you will come against during the exam.

Here is a breakdown of the review schedule and timeline:

- 30 min - Overview (Sorting by theme, region, and time periods)

- 1 hour - 1200-1450 CE

- 1 hour - 1450-1750 CE

- 1 hour - 1750-1900 CE

- 1 hour - 1900-Present

- 30 min - Final thoughts (Time management, strategies, and pep talk)

Stay Connected

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.

AP® and SAT® are trademarks registered by the College Board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse this website.

What Does It Mean to Think Historically?

Thomas Andrews and Flannery Burke | Jan 1, 2007

Introduction

When we started working on Teachers for a New Era, a Carnegie-sponsored initiative designed to strengthen teacher training, we thought we knew a thing or two about our discipline. As we began reading such works as Sam Wineburg's Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts , however, we encountered an unexpected challenge. 1 If our understandings of the past constituted a sort of craft knowledge, how could we distill and communicate habits of mind we and our colleagues had developed through years of apprenticeship, guild membership, and daily practice to university students so that they, in turn, could impart these habits in K–12 classrooms?

In response, we developed an approach we call the "five C's of historical thinking." The concepts of change over time, causality, context, complexity, and contingency, we believe, together describe the shared foundations of our discipline. They stand at the heart of the questions historians seek to answer, the arguments we make, and the debates in which we engage. These ideas are hardly new to professional historians. But that is precisely their value: They make our implicit ways of thought explicit to the students and teachers whom we train. The five C's do not encompass the universe of historical thinking, yet they do provide a remarkably useful tool for helping students at practically any level learn how to formulate and support arguments based on primary sources, as well as to understand and challenge historical interpretations related in secondary sources. In this article, we define the five C's, explain how each concept helps us to understand the past, and provide some brief examples of how we have employed the five C's when teaching teachers. Our approach is necessarily broad and basic, characteristics well suited for a foundation upon which we invite our colleagues from kindergartens to research universities to build.

Change over Time

The idea of change over time is perhaps the easiest of the C's to grasp. Students readily acknowledge that we employ and struggle with technologies unavailable to our forebears, that we live by different laws, and that we enjoy different cultural pursuits. Moreover, students also note that some aspects of life remain the same across time. Many Europeans celebrate many of the same holidays that they did three or four hundred years ago, for instance, often using the same rituals and words to mark a day's significance. Continuity thus comprises an integral part of the idea of change over time.

Students often find the concept of change over time elementary. Even individuals who claim to despise history can remember a few dates and explain that some preceded or followed others. At any educational level, timelines can teach change over time as well as the selective process that leads people to pay attention to some events while ignoring others. In our U.S. survey class, we often ask students to interview family and friends and write a paper explaining how their family's history has intersected with major events and trends that we are studying. By discovering their own family's past, students often see how individuals can make a difference and how personal history changes over time along with major events.

As historians of the American West and environmental historians, we often turn to maps to teach change over time. The same space represented in different ways as political power, economic structures, and cultural influences shift can often put in shocking relief the differences that time makes. The work of repeat photographers such as Mark Klett offers another compelling tool for teaching change over time. Such photographers begin with a historic landscape photograph, then take pains to re-take the shot from the same site, at the same angle, using similar equipment, and even under analogous conditions. 2 While suburbs and industry have overrun many western locales, students are often surprised to see that some places have become more desolate and others have hardly changed at all. The exercise engages students with a non-written primary source, photographs, and demands that they reassess their expectations regarding how time changes.

Some things change, others stay the same—not a very interesting story but reason for concern since history, as the best teachers will tell you, is about telling stories. Good story telling, we contend, builds upon an understanding of context. Given young people's fascination with narratives and their enthusiasm for imaginative play, pupils (particularly elementary school students) often find context the most engaging element of historical thinking. As students mature, of course, they recognize that the past is not just a playful alternate universe. Working with primary sources, they discover that the past makes more sense when they set it within two frameworks. In our teaching, we liken the first to the floating words that roll across the screen at the beginning of every Star Wars film. This kind of context sets the stage; the second helps us to interpret evidence concerning the action that ensues. Texts, events, individual lives, collective struggles—all develop within a tightly interwoven world.

Historians who excel at the art of storytelling often rely heavily upon context. Jonathan Spence's Death of Woman Wang , for example, skillfully recreates 17th-century China by following the trail of a sparsely documented murder. To solve the mystery, students must understand the time and place in which it occurred. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich brings colonial New England to life by concentrating on the details of textile production and basket making in Age of Homespun . College courses regularly use the work of both authors because they not only spark student interest, but also hone students' ability to describe the past and identify distinctive elements of different eras. 3

Imaginative play is what makes context, arguably the easiest, yet also, paradoxically, the most difficult of the five C's to teach. Elementary school assignments that require students to research and wear medieval European clothes or build a California mission from sugar cubes both strive to teach context. The problem with such assignments is that they often blur the lines between reality and make-believe. The picturesque often trumps more banal or more disturbing truths. Young children may never be able to get all the facts straight. As one elementary school teacher once reminded us, "We teach kids who still believe in Santa Claus." Nonetheless, elementary school teachers can be cautious in their re-creations, and, most of all, they can be comfortable telling students when they don't know a given fact or when more research is necessary. That an idea might require more thought or more research is a valuable lesson at any age. The desire to recreate a world sometimes drives students to dig more deeply into their books, a reaction few teachers lament.

In our own classes, we have taught context using an assignment that we call "Fact, Fiction, or Creative Memory." In this exercise, students wrestle with a given source and determine whether it is primarily a work of history, fiction, or memory. We have asked students to bring in a present-day representation of 1950s life and explain what it teaches people today about life in 1950s America. Then, we have asked the class to discuss if the representation is a historically fair depiction of the era. We have also assigned textbook passages and Don DeLillo's Pafko at the Wall , then asked students to compare them to decide which offers stronger insights into the character of Cold War America. 4 Each of these assignments addresses context, because each asks students to think about the distinctions between representations of the past and the critical thinking about the past that is history. Moreoever, each asks students to weave together a variety of sources and assess the reliability of each before incorporating them into a whole.

Historians use context, change over time, and causality to form arguments explaining past change. While scientists can devise experiments to test theories and yield data, historians cannot alter past conditions to produce new information. Rather, they must base their arguments upon the interpretation of partial primary sources that frequently offer multiple explanations for a single event. Historians have long argued over the causes of the Protestant Reformation or World War I, for example, without achieving consensus. Such uncertainty troubles some students, but history classrooms are at their most dynamic when teachers encourage pupils to evaluate the contributions of multiple factors in shaping past events, as well as to formulate arguments asserting the primacy of some causes over others.

To teach causality, we have turned to the stand-by activities of the history classroom: debates and role-playing. After arming students with primary sources, we ask them to argue whether monetary or fiscal policy played a greater role in causing the Great Depression. After giving students descriptions drawn from primary sources of immigrant families in Los Angeles, we have asked students to take on the role of various family members and explain their reasons for immigrating and their reasons for settling in particular neighborhoods. Neither exercise is especially novel, but both fulfill a central goal of studying history: to develop persuasive explanations of historical events and processes based on logical interpretations of evidence.

Contingency

Contingency may, in fact, be the most difficult of the C's. To argue that history is contingent is to claim that every historical outcome depends upon a number of prior conditions; that each of these prior conditions depends, in turn, upon still other conditions; and so on. The core insight of contingency is that the world is a magnificently interconnected place. Change a single prior condition, and any historical outcome could have turned out differently. Lee could have won at Gettysburg, Gore might have won in Florida, China might have inaugurated the world's first industrial revolution. Contingency can be an unsettling idea—so much so that people in the past have often tried to mask it with myths of national and racial destiny. The Pilgrim William Bradford, for instance, interpreted the decimation of New England's native peoples not as a consequence of smallpox, but as a literal godsend. 5 Two centuries later, American ideologues chose to rationalize their unlikely fortunes—from the purchase of Louisiana to the discovery of gold in California—as their nation's "Manifest Destiny." Historians, unlike Bradford and the apologists of westward expansion, look at the same outcomes differently. They see not divine fate, but a series of contingent results possessing other possibilities.

Contingency demands that students think deeply about past, present, and future. It offers a powerful corrective to teleology, the fallacy that events pursue a straight-arrow course to a pre-determined outcome, since people in the past had no way of anticipating our present world. Contingency also reminds us that individuals shape the course of human events. What if Karl Marx had decided to elude Prussian censors by emigrating to the United States instead of France, where he met Frederick Engels? To assert that the past is contingent is to impress upon students the notion that the future is up for grabs, and that they bear some responsibility for shaping the course of future history.

Contingency can be a difficult concept to present abstractly, but it suffuses the stories historians tend to tell about individual lives. Futurology, however, might offer an even stronger tool for imparting contingency than biography. Mechanistic views of history as the inevitable march toward the present tend to collapse once students see how different their world is from any predicted in the past.

Moral, epistemological, and causal complexity distinguish historical thinking from the conception of "history" held by many non-historians. 6 Re-enacting battles and remembering names and dates require effort but not necessarily analytical rigor. Making sense of a messy world that we cannot know directly, in contrast, is more confounding but also more rewarding.

Chronicles distill intricate historical processes into a mere catalogue, while nostalgia conjures an uncomplicated golden age that saves us the trouble of having to think about the past. Our own need for order can obscure our understanding of how past worlds functioned and blind us to the ways in which myths of rosy pasts do political and cultural work in the present. Reveling in complexity rather than shying away from it, historians seek to dispel the power of chronicle, nostalgia, and other traps that obscure our ability to understand the past on its own terms.

One of the most successful exercises we have developed for conveying complexity in all of these dimensions is a mock debate on Cherokee Removal. Two features of the exercise account for the richness and depth of understanding that it imparts on students. First, the debate involves multiple parties; the Treaty and Anti-Treaty Parties, Cherokee women, John Marshall, Andrew Jackson, northern missionaries, the State of Georgia, and white settlers each offer a different perspective on the issue. Second, students develop their understanding of their respective positions using the primary sources collected in Cherokee Removal: A Brief History with Documents by Theda Perdue and Michael Green. 7 While it can be difficult to assess what students learn from such exercises, we have noted anecdotally that, following the exercise, students seem much less comfortable referring to "American" or "Indian" positions as monolithic identities.

Our experiments with the five C's have confronted us with several challenges. These concepts offer a fluid tool for engaging historical thought at multiple levels, but they can easily degenerate into a checklist. Students who favor memorization over analysis seem inclined to recite the C's without necessarily understanding them. Moreover, as habits of mind, the five C's develop only with practice. Though primary and secondary schools increasingly emphasize some aspects of these themes, particularly the use of primary sources as evidence, more attention to the five C's with appropriate variations over the course of K–12 education would help future citizens not only to care about history, but also to contemplate it. It is our hope that this might help students to see the past not simply as prelude to our present, nor a list of facts to memorize, a cast of heroes and villains to cheer and boo, nor as an itinerary of places to tour, but rather as an ideal field for thinking long and hard about important questions.

—Flannery Burke and Thomas Andrews are both assistant professors of history and Teachers for a New Era faculty members at California State University at Northridge. Burke is working on a book for the University Press of Kansas tentatively entitled Longing and Belonging: Mabel Dodge Luhan and Greenwich Village's Avant-Garde in Taos . Andrews is completing a manuscript for Harvard University Press, tentatively entitled Ludlow: The Nature of Industrial Struggle in the Colorado Coalfields .

1. Sam Wineburg, Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001).

2. Mark Klett, Kyle Bajakian, William L. Fox, Michael Marshall, Toshi Ueshina, and Byron G. Wolfe, Third Views, Second Sights: A Rephotographic Survey of the American West (Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 2004).

3. Jonathan D. Spence, Death of Woman Wang (New York: Viking, 1978); Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth (New York: Knopf, 2001).

4. Don DeLillo, Pafko at the Wall: A Novella (New York: Scribner's, 2001).

5. William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation , ed. Samuel Eliot Morison (New York: Random House, 1952).

6. Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen, The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998).

7. Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green, The Cherokee Removal: A Brief History with Documents 2nd ed. (Boston and New York: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2005).

Tags: K12 Certification & Curricula Teaching Resources and Strategies

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities , and in letters to the editor . Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

Change Over Time Essay

Enter the password to open this PDF file:

How to Write a Change-Over-Time Essay

Janie sullivan.

Change-over-time essays deal with global issues and how they either change or effect change on the environment. Timelines are important in change-over-time essays. The writer will typically synthesize a large portion of a timeline, using significant events to anchor the content in the essay. A change-over-time essay is not a research paper; it is a paper that supports a thesis with sound analysis rather than a rehash of an article in an encyclopedia.

Explore this article

- Steps in Essay Writing

- Find a topic to address

- Create a thesis statement

1 Steps in Essay Writing

2 find a topic to address.

Find a topic to address. Change-over-time essays follow the same basic rules as writing comparative essays. They deal with change that has occurred in an area such as technology, trade, culture, migrations or religious influence. Choose a period of time that best illustrates the change that has occurred.

3 Create a thesis statement

Create a thesis statement. This should include the date range or time period that will be covered, the region or country affected by the change, and what the actual change was.

Support the thesis statement by the content of the essay. Do the research and use more than just obvious similarities and differences exhibited during the period of time chosen.

Use the acronym "SPRITE" when reviewing the essay to be sure all aspects of the thesis have been covered. "SPRITE" stands for "Social, Political, Religious, Intellectual, Technological, Economic."

Write the conclusion of the essay in much the same way as a conclusion for a comparison essay is written. Include the premise stated in the thesis and summarize what the content revealed about the statement.

- Be sure to cite any sources appropriately.

- 1 Change Over Time: The Silk Road

About the Author

Janie Sullivan, a freelance writer living in Apache Junction, Arizona, has had articles published in Small Business Start-Ups and The Adjunct Advocate magazines. She earned a Bachelor of Arts in journalism from the University of Montana and both a Master of Business Administration and a Master of Arts in Education from the University of Phoenix.

Related Articles

How to Write a CCOT Essay

How to Make a Good Introduction Paragraph

Define MLA Writing Format

Characteristics of Narrative Essays

How to Write a Current Event Essay

What Makes Up a Well-Written Essay in High School?

How to Write an AP US History DBQ Essay

How to Write a Conclusion in My Nursing Paper

How to Write a Topic Summary for an Essay

Basic Writing Skills for Middle School

What Is Informal & Formal Essay Writing?

What Are the Writing Elements for a Personal Narrative?

Step-by-Step Explanation of How to Write a Research...

How to Write an Essay Abstract

How to Write an Introduction for a Character Analysis

How to Write an Introduction for an Argument Essay

Definition of Micro & Macro Economics

How to Conclude a Thesis Paper

Narrative Essay Requirements

What Is International Relations?

Regardless of how old we are, we never stop learning. Classroom is the educational resource for people of all ages. Whether you’re studying times tables or applying to college, Classroom has the answers.

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright Policy

- Manage Preferences

© 2020 Leaf Group Ltd. / Leaf Group Media, All Rights Reserved. Based on the Word Net lexical database for the English Language. See disclaimer .

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essay Examples >

- Essays Topics >

- Essay on War

Change And Continuity Over Time Essay Examples

Type of paper: Essay

Topic: War , Africa , Economics , Time , Europe , Colonization , World , Colony

Published: 02/06/2020

ORDER PAPER LIKE THIS

World War I resulted in considerably varying consequences in different African territories, depending on the extent to which they had been involved in the war. No doubt, new doors were opened up after the war for many Africans, especially the educated elite groups. The war also boosted nationalist activity in many parts of Africa and a more critical approach was being taken towards colonial matters. With the end of the war, Africans also stopped trying to regain the sovereignty of polities that had been lost after the colonization of Africa. However, at the same time the demands of Africans to take part in the process of government of the new politics the Europeans had imposed on them. These demands served as an inspiration for the Fourteen Points of President Woodrow Wilson. The demands for self determination began rising throughout Africa, especially in Egypt and Tunisia. Although the Fourteen Points of Wilson did not serve as an inspiration for the demands for immediate independence in Africa, however, West African nationalists were encouraged to be hopeful in influencing the Versailles Peace Conference and demanding a greater involvement in their own affairs. The Fourteen Points of Wilson resulted in a decisive change in Sudanese nationalism, giving rise to a new generation of young African men with informed attitudes, who had studied in government schools and possessed some modern western skills. Thus, the First World War also marked a decisive but perhaps not a dramatic change in African history, whereas the elimination of a Germany as a colonial power as a result of the Treaty of Versailles, and the its replacement by Britain and France can be viewed as a continuation of European influence. The end of the First World War not only ended the partition of Africa but also temporarily halted African efforts to regain independence. The 1920s marked the formulation of and application of colonial policies regarding labor, land and economic development. By the 1920s, Africans began influencing the terms of their involvement in the African economy resulting in a new phase in economic relations. During this period, Africans continued to participate and play their role in the colonial economy by working on the plantations in Central and East Africa and Congo, and in the mines in South Africa. Economic opposition during t his time period was not well organized in most cases. By 1920, it was obvious that the colonial government was condoning racial segregation everywhere throughout the African continent. Mass protests against colonial policies of the 1920s were scarce, apart from the Aba Women’s War in 1929 by southeastern Nigerian women. The end of the 1920s also marked the arrival of the economic depression that resulted in equal suffering of Africans and the owners of the markets. During the Second World War, Africa was forced to compensate for the shortage of raw materials in the Far East and this would prove to be very beneficial for the independence of African nations. As a result, the transportation of raw materials to Europe and so local industries had to be created in Africa. New towns were created as a result of the local industrialization and size of existing towns doubled. The growth of industry and urban community also marked the growth of trade unions and literacy also increased, all of which contributed to the ultimate independence of the African continent. European economies had been utterly devastated for a second time by the end of the Second World War in 1945 and with the European nationals financially ruined; they could no longer afford to keep the African colonies. Moreover, they realized that they could also no longer justify keeping African societies under colonial rule.

Works Cited

Birmingham, David. The Decolonization Of Africa. Routledge, 1997. Print. Kevin, Shillington. A History Of South Africa. 2nd ed. New York: Palgrave MacMiller, 2005. Print.

Cite this page

Share with friends using:

Removal Request

Finished papers: 885

This paper is created by writer with

ID 269795741

If you want your paper to be:

Well-researched, fact-checked, and accurate

Original, fresh, based on current data

Eloquently written and immaculately formatted

275 words = 1 page double-spaced

Get your papers done by pros!

Other Pages

Sister biographies, mission statement case studies, further course work, the nation course work, good engineering critical thinking example, essay on the plasma supply, virginia in the new governmental essays example, good essay on changes experienced that are related to global change, good essay about marketing and health care, good essay on briefly summarize the quot intended organization quot i e the organization, free essay on poems and themes, good example of sea level rise and coastal development research paper, good research paper on diabetes effects on african americans, professional and patients relationship essay samples, free report on work breakdown structure, good dissertation on parents experiences when their at risk child returns home, good drugs essay example, free childhood development creative writing example, example of the effects of the strong dollar on the us exports research paper, example of the institutional affiliation essay, free forecasting future digital crime and terrorism critical thinking sample, spectrum mobility and handoff in cognitive radio research paper, armani essays, back seat essays, ansel essays, arisen essays, baris essays, arjun essays, baier essays, muslim world essays, western nations essays, bic cristal essays, health care disparities essays, investigations essays, arrests essays, rest of the world essays, riots essays, life experience essays, shiga essays, antibodies essays, myositis essays.

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

Scientific Consensus

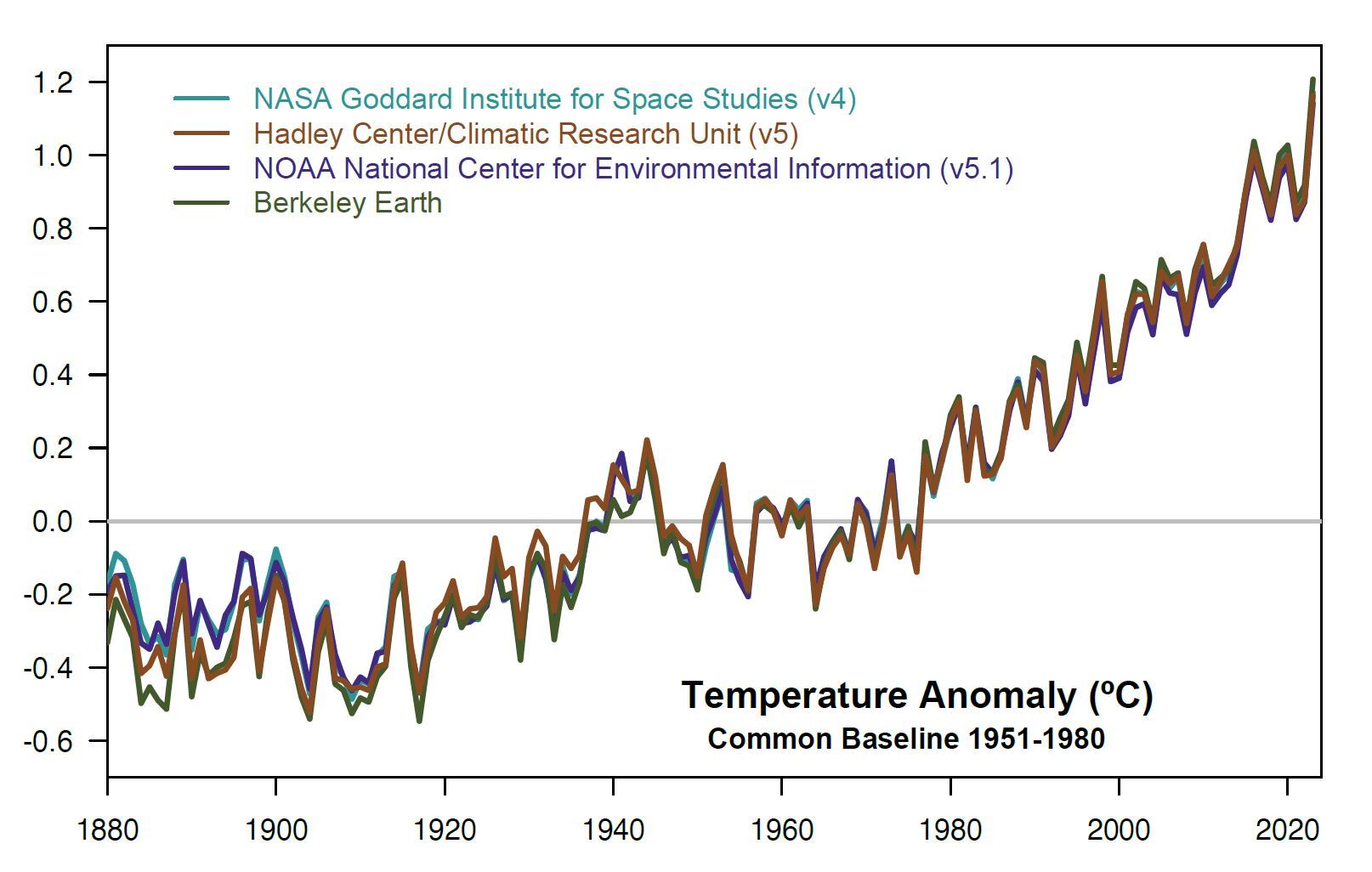

It’s important to remember that scientists always focus on the evidence, not on opinions. Scientific evidence continues to show that human activities ( primarily the human burning of fossil fuels ) have warmed Earth’s surface and its ocean basins, which in turn have continued to impact Earth’s climate . This is based on over a century of scientific evidence forming the structural backbone of today's civilization.

NASA Global Climate Change presents the state of scientific knowledge about climate change while highlighting the role NASA plays in better understanding our home planet. This effort includes citing multiple peer-reviewed studies from research groups across the world, 1 illustrating the accuracy and consensus of research results (in this case, the scientific consensus on climate change) consistent with NASA’s scientific research portfolio.

With that said, multiple studies published in peer-reviewed scientific journals 1 show that climate-warming trends over the past century are extremely likely due to human activities. In addition, most of the leading scientific organizations worldwide have issued public statements endorsing this position. The following is a partial list of these organizations, along with links to their published statements and a selection of related resources.

American Scientific Societies

Statement on climate change from 18 scientific associations.

"Observations throughout the world make it clear that climate change is occurring, and rigorous scientific research demonstrates that the greenhouse gases emitted by human activities are the primary driver." (2009) 2

American Association for the Advancement of Science

"Based on well-established evidence, about 97% of climate scientists have concluded that human-caused climate change is happening." (2014) 3

American Chemical Society

"The Earth’s climate is changing in response to increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases (GHGs) and particulate matter in the atmosphere, largely as the result of human activities." (2016-2019) 4

American Geophysical Union

"Based on extensive scientific evidence, it is extremely likely that human activities, especially emissions of greenhouse gases, are the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century. There is no alterative explanation supported by convincing evidence." (2019) 5

American Medical Association

"Our AMA ... supports the findings of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s fourth assessment report and concurs with the scientific consensus that the Earth is undergoing adverse global climate change and that anthropogenic contributions are significant." (2019) 6

American Meteorological Society

"Research has found a human influence on the climate of the past several decades ... The IPCC (2013), USGCRP (2017), and USGCRP (2018) indicate that it is extremely likely that human influence has been the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-twentieth century." (2019) 7

American Physical Society

"Earth's changing climate is a critical issue and poses the risk of significant environmental, social and economic disruptions around the globe. While natural sources of climate variability are significant, multiple lines of evidence indicate that human influences have had an increasingly dominant effect on global climate warming observed since the mid-twentieth century." (2015) 8

The Geological Society of America

"The Geological Society of America (GSA) concurs with assessments by the National Academies of Science (2005), the National Research Council (2011), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2013) and the U.S. Global Change Research Program (Melillo et al., 2014) that global climate has warmed in response to increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases ... Human activities (mainly greenhouse-gas emissions) are the dominant cause of the rapid warming since the middle 1900s (IPCC, 2013)." (2015) 9

Science Academies

International academies: joint statement.

"Climate change is real. There will always be uncertainty in understanding a system as complex as the world’s climate. However there is now strong evidence that significant global warming is occurring. The evidence comes from direct measurements of rising surface air temperatures and subsurface ocean temperatures and from phenomena such as increases in average global sea levels, retreating glaciers, and changes to many physical and biological systems. It is likely that most of the warming in recent decades can be attributed to human activities (IPCC 2001)." (2005, 11 international science academies) 1 0

U.S. National Academy of Sciences

"Scientists have known for some time, from multiple lines of evidence, that humans are changing Earth’s climate, primarily through greenhouse gas emissions." 1 1

U.S. Government Agencies

U.s. global change research program.

"Earth’s climate is now changing faster than at any point in the history of modern civilization, primarily as a result of human activities." (2018, 13 U.S. government departments and agencies) 12

Intergovernmental Bodies

Intergovernmental panel on climate change.

“It is unequivocal that the increase of CO 2 , methane, and nitrous oxide in the atmosphere over the industrial era is the result of human activities and that human influence is the principal driver of many changes observed across the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere, and biosphere. “Since systematic scientific assessments began in the 1970s, the influence of human activity on the warming of the climate system has evolved from theory to established fact.” 1 3-17

Other Resources

List of worldwide scientific organizations.

The following page lists the nearly 200 worldwide scientific organizations that hold the position that climate change has been caused by human action. http://www.opr.ca.gov/facts/list-of-scientific-organizations.html

U.S. Agencies

The following page contains information on what federal agencies are doing to adapt to climate change. https://www.c2es.org/site/assets/uploads/2012/02/climate-change-adaptation-what-federal-agencies-are-doing.pdf

Technically, a “consensus” is a general agreement of opinion, but the scientific method steers us away from this to an objective framework. In science, facts or observations are explained by a hypothesis (a statement of a possible explanation for some natural phenomenon), which can then be tested and retested until it is refuted (or disproved).

As scientists gather more observations, they will build off one explanation and add details to complete the picture. Eventually, a group of hypotheses might be integrated and generalized into a scientific theory, a scientifically acceptable general principle or body of principles offered to explain phenomena.

1. K. Myers, et al, "Consensus revisited: quantifying scientific agreement on climate change and climate expertise among Earth scientists 10 years later", Environmental Research Letters Vol.16 No. 10, 104030 (20 October 2021); DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2774 M. Lynas, et al, "Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature", Environmental Research Letters Vol.16 No. 11, 114005 (19 October 2021); DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2966 J. Cook et al., "Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming", Environmental Research Letters Vol. 11 No. 4, (13 April 2016); DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002 J. Cook et al., "Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature", Environmental Research Letters Vol. 8 No. 2, (15 May 2013); DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/024024 W. R. L. Anderegg, “Expert Credibility in Climate Change”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Vol. 107 No. 27, 12107-12109 (21 June 2010); DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1003187107 P. T. Doran & M. K. Zimmerman, "Examining the Scientific Consensus on Climate Change", Eos Transactions American Geophysical Union Vol. 90 Issue 3 (2009), 22; DOI: 10.1029/2009EO030002 N. Oreskes, “Beyond the Ivory Tower: The Scientific Consensus on Climate Change”, Science Vol. 306 no. 5702, p. 1686 (3 December 2004); DOI: 10.1126/science.1103618

2. Statement on climate change from 18 scientific associations (2009)

3. AAAS Board Statement on Climate Change (2014)

4. ACS Public Policy Statement: Climate Change (2016-2019)

5. Society Must Address the Growing Climate Crisis Now (2019)

6. Global Climate Change and Human Health (2019)

7. Climate Change: An Information Statement of the American Meteorological Society (2019)

8. American Physical Society (2021)

9. GSA Position Statement on Climate Change (2015)

10. Joint science academies' statement: Global response to climate change (2005)

11. Climate at the National Academies

12. Fourth National Climate Assessment: Volume II (2018)

13. IPCC Fifth Assessment Report, Summary for Policymakers, SPM 1.1 (2014)

14. IPCC Fifth Assessment Report, Summary for Policymakers, SPM 1 (2014)

15. IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, Working Group 1 (2021)