How to Teach Argument Writing Step-By-Step

No doubt, teaching argument writing to middle school students can be tricky. Even the word “argumentative” is off-putting, bringing to mind pointless bickering. But once I came up with argument writing lessons that were both fun and effective, I quickly saw the value in it. And so did my students.

You see, we teachers have an ace up our sleeve. It’s a known fact that from ages 11-14, kids love nothing more than to fire up a good ole battle royale with just about anybody within spitting distance.

Yup. So we’re going to use their powers of contradiction to OUR advantage by showing them how to use our argument writing lessons to power up their real-life persuasion skills. Your students will be knocking each other over in the hall to get to the room first!

I usually plan on taking about three weeks on the entire argument writing workshop. However, there are years when I’ve had to cut it down to two, and that works fine too.

Here are the step-by-step lessons I use to teach argument writing. It might be helpful to teachers who are new to teaching the argument, or to teachers who want to get back to the basics. If it seems formulaic, that’s because it is. In my experience, that’s the best way to get middle school students started.

Prior to Starting the Writer’s Workshop

A couple of weeks prior to starting your unit, assign some quick-write journal topics. I pick one current event topic a day, and I ask students to express their opinion about the topic.

Quick-writes get the kids thinking about what is going on in the world and makes choosing a topic easier later on.

Define Argumentative Writing

I’ll never forget the feeling of panic I had in 7th grade when my teacher told us to start writing an expository essay on snowstorms. How could I write an expository essay if I don’t even know what expository MEANS, I whined to my middle school self.

We can’t assume our students know or remember what argumentative writing is, even if we think they should know. So we have to tell them. Also, define claim and issue while you’re at it.

Establish Purpose

I always tell my students that learning to write an effective argument is key to learning critical thinking skills and is an important part of school AND real-life writing.

We start with a fictional scenario every kid in the history of kids can relate to.

ISSUE : a kid wants to stay up late to go to a party vs. AUDIENCE : the strict mom who likes to say no.

The “party” kid writes his mom a letter that starts with a thesis and a claim: I should be permitted to stay out late to attend the part for several reasons.

By going through this totally relatable scenario using a modified argumentative framework, I’m able to demonstrate the difference between persuasion and argument, the importance of data and factual evidence, and the value of a counterclaim and rebuttal.

Students love to debate whether or not strict mom should allow party kid to attend the party. More importantly, it’s a great way to introduce the art of the argument, because kids can see how they can use the skills to their personal advantage.

Persuasive Writing Differs From Argument Writing

At the middle school level, students need to understand persuasive and argument writing in a concrete way. Therefore, I keep it simple by explaining that both types of writing involve a claim. However, in persuasive writing, the supporting details are based on opinions, feelings, and emotions, while in argument writing the supporting details are based on researching factual evidence.

I give kids a few examples to see if they can tell the difference between argumentation and persuasion before we move on.

Argumentative Essay Terminology

In order to write a complete argumentative essay, students need to be familiar with some key terminology . Some teachers name the parts differently, so I try to give them more than one word if necessary:

- thesis statement

- bridge/warrant

- counterclaim/counterargument*

- turn-back/refutation

*If you follow Common Core Standards, the counterargument is not required for 6th-grade argument writing. All of the teachers in my school teach it anyway, and I’m thankful for that when the kids get to 7th grade.

Organizing the Argumentative Essay

I teach students how to write a step-by-step 5 paragraph argumentative essay consisting of the following:

- Introduction : Includes a lead/hook, background information about the topic, and a thesis statement that includes the claim.

- Body Paragraph #1 : Introduces the first reason that the claim is valid. Supports that reason with facts, examples, and/or data.

- Body Paragraph #2 : The second reason the claim is valid. Supporting evidence as above.

- Counterargument (Body Paragraph #3): Introduction of an opposing claim, then includes a turn-back to take the reader back to the original claim.

- Conclusion : Restates the thesis statement, summarizes the main idea, and contains a strong concluding statement that might be a call to action.

Mentor Texts

If we want students to write a certain way, we should provide high-quality mentor texts that are exact models of what we expect them to write.

I know a lot of teachers will use picture books or editorials that present arguments for this, and I can get behind that. But only if specific exemplary essays are also used, and this is why.

If I want to learn Italian cooking, I’m not going to just watch the Romanos enjoy a holiday feast on Everybody Loves Raymond . I need to slow it down and follow every little step my girl Lidia Bastianich makes.

The same goes for teaching argument writing. If we want students to write 5 paragraph essays, that’s what we should show them.

In fact, don’t just display those mentor texts like a museum piece. Dissect the heck out of those essays. Pull them apart like a Thanksgiving turkey. Disassemble the essay sentence by sentence and have the kids label the parts and reassemble them. This is how they will learn how to structure their own writing.

Also, encourage your detectives to evaluate the evidence. Ask students to make note of how the authors use anecdotes, statistics, and facts. Have them evaluate the evidence and whether or not the writer fully analyzes it and connects it to the claim.

This is absolutely the best way for kids to understand the purpose of each part of the essay.

Research Time

Most of my students are not very experienced with performing research when we do this unit, so I ease them into it. (Our “big” research unit comes later in the year with our feature article unit .)

I start them off by showing this short video on how to find reliable sources. We use data collection sheets and our school library’s database for research. There are also some awesome, kid-friendly research sites listed on the Ask a Tech Teacher Blog .

Step-By-Step Drafting

The bedrock of drafting is to start with a solid graphic organizer. I have to differentiate for my writers, and I’ve found they have the most success when I offer three types of graphic organizers.

1- Least Support: This is your standard graphic organizer. It labels each paragraph and has a dedicated section for each part of the paragraph.

2- Moderate Support: This one has labels and sections, but also includes sentence stems for each sentence in the paragraph.

3- Most Support: This one has labels and sections and also includes fill-in-the-blank sentence frames . It’s perfect for my emerging writers, and as I’ve mentioned previously, students do NOT need the frames for long and soon become competent and independent writers.

Writing the Introduction

The introduction has three parts and purposes.

First, it has a hook or lead. While it should be about the topic, it shouldn’t state the writer’s position on the topic. I encourage students to start with a quote by a famous person, an unusual detail, a statistic, or a fact.

Kids will often try to start with a question, but I discourage that unless their question also includes one of the other strategies. Otherwise, I end up with 100 essays that start with, “Do you like sharks?” Lol

Next, it’s time to introduce the issue. This is the background information that readers need in order to understand the controversy.

Last, students should state the claim in the thesis statement. I call it a promise to the reader that the essay will deliver by proving that the claim is valid.

Writing the Supporting Body Paragraphs

Each supporting body paragraph should start with a topic sentence that introduces the idea and states the reason why the claim is valid. The following sentences in the paragraph should support that reason with facts, examples, data, or expert opinions. The bridge is the sentence that connects that piece of evidence to the argument’s claim. The concluding sentence should restate the reason.

Writing the Counterclaim Paragraph

The counterclaim paragraph is a very important aspect of argument writing. It’s where we introduce an opposing argument and then confidently take the reader back to the original argument. I tell students that it’s necessary to “get in the head” of the person who might not agree with their claim, by predicting their objections.

It can be tough for kids to “flip the switch” on their own argument, so I like to practice this a bit. I give them several pairs of transitions that go together to form a counterclaim and rebuttal. I also switch up what I call this part so that they use the terminology interchangeably.

- It might seem that [ counterargument . ]However, [ turn-back .]

- Opponents may argue that [ counterargument .] Nevertheless, [ turn back .]

- A common argument against this position is [ counterargument .] Yet, [ turn-back .]

A great way for kids to practice this is to have them work with partners to write a few counterarguments together. I let them practice by giving them easy role-playing topics.

- Your cousins want to jump into a poison ivy grove for a TikTok challenge. Choose your position on this and write a counterargument and turn-back.

- Your friend wants to get a full-face tattoo of their boyfriend’s name. Choose your position on this and write a counterargument and turn-back.

This kind of practice makes the counterargument much more clear.

The concluding paragraph should remind the reader of what was argued in the essay and why it matters. It might also suggest solutions or further research that could be done on the topic. Or students can write a call to action that asks the reader to perform an action in regard to the information they’ve just learned.

My students write about local issues and then turn the essays into letters to our superintendent, school board, or state senators. It’s an amazing way to empower kids and to show them that their opinion matters. I’ve written about that here and I’ve included the sentence frames for the letters in my argumentative writing unit.

I hope this gives you a good overview of teaching argument writing. Please leave any questions below. Please also share your ideas, because we all need all the help we can give each other!

And one more thing. Don’t be surprised if parents start asking you to tone down the unit because it’s become harder to tell their kids why they can’t stay up late for parties. 🙂

Stay delicious!

Narrative Writing Workshop for Middle School ELA

Fiction & Nonfiction Reading -Teach, Practice, Test BUNDLE – Middle School ELA

RACES Writing Introduction to Paragraph Frames DIGITAL & EDITABLE

- Our Mission

Strategies for Teaching Argument Writing

Three simple ways a ninth-grade teacher scaffolds argument writing for students.

My ninth-grade students love to argue. They enjoy pushing back against authority, sharing their opinions, and having those opinions validated by their classmates. That’s no surprise—it’s invigorating to feel right about a hot-button topic. But through the teaching of argument writing, we can show our students that argumentation isn’t just about convincing someone of your viewpoint—it’s also about researching the issues, gathering evidence, and forming a nuanced claim.

Argument writing is a crucial skill for the real world, no matter what future lies ahead of a student. The Common Core State Standards support the teaching of argument writing , and students in the elementary grades on up who know how to support their claims with evidence will reap long-term benefits.

Argument Writing as Bell Work

One of the ways I teach argument writing is by making it part of our bell work routine, done in addition to our core lessons. This is a useful way to implement argument writing in class because there’s no need to carve out two weeks for a new unit.

Instead, at the bell, I provide students with an article to read that is relevant to our coursework and that expresses a clear opinion on an issue. They fill out the first section of the graphic organizer I’ve included here, which helps them identify the claim, supporting evidence, and hypothetical counterclaims. After three days of reading nonfiction texts from different perspectives, their graphic organizer becomes a useful resource for forming their own claim with supporting evidence in a short piece of writing.

The graphic organizer I use was inspired by the resources on argument writing provided by the National Writing Project through the College, Career, and Community Writers Program . They have resources for elementary and secondary teachers interested in argument writing instruction. I also like to check Kelly Gallagher’s Article of the Week for current nonfiction texts.

Moves of Argument Writing

Another way to practice argument writing is by teaching students to be aware of, and to use effectively, common moves found in argument writing. Joseph Harris’s book Rewriting: How to Do Things With Texts outlines some common moves:

- Illustrating: Using examples, usually from other sources, to explain your point.

- Authorizing: Calling upon the credibility of a source to help support to your argument.

- Borrowing: Using the terminology of other writers to help add legitimacy to a point.

- Extending: Adding commentary to the conversation on the issue at hand.

- Countering: Addressing opposing arguments with valid solutions.

Teaching students to identify these moves in writing is an effective way to improve reading comprehension, especially of nonfiction articles. Furthermore, teaching students to use these moves in their own writing will make for more intentional choices and, subsequently, better writing.

Argument Writing With Templates

Students who purposefully read arguments with the mindset of a writer can be taught to recognize the moves identified above and more. Knowing how to identify when and why authors use certain sentence starters, transitions, and other syntactic strategies can help students learn how to make their own point effectively.

To supplement our students’ knowledge of these syntactic strategies, Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein recommend writing with templates in their book They Say, I Say: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing . Graff and Birkenstein provide copious templates for students to use in specific argument writing scenarios. For example, consider these phrases that appear commonly in argument writing:

- On the one hand...

- On the other hand...

- I agree that...

- This is not to say that...

If you’re wary of having your students write using a template, I once felt the same way. But when I had my students purposefully integrate these words into their writing, I saw a significant improvement in their argument writing. Providing students with phrases like these helps them organize their thoughts in a way that better suits the format of their argument writing.

When we teach students the language of arguing, we are helping them gain traction in the real world. Throughout their lives, they’ll need to convince others to support their goals. In this way, argument writing is one of the most important tools we can teach our students to use.

Bell Ringers

Teaching argumentative writing in middle school ela: part one.

If you teach middle school, you know that teenagers have a lot of opinions! Luckily, you can use that to your advantage when teaching students how to write an argumentative essay. The key is to help students learn to craft well-written arguments with evidence (not just arguing for the sake of it, which middle schoolers can be prone to).

While learning to craft argumentative essays will help students in school, being able to craft and defend an argument is also an important skill for the real world. Writing an argumentative essay or having a debate requires critical thinking skills and the ability to take a stance and back it up.

What is Argumentative Writing?

In order for students to understand how to write an argumentative essay, they need to understand what argumentative writing is.

Argumentative essays usually require that students do some investigation or research on a topic and then choose a clear stance. When writing, students will spend the body of the essay explaining points and providing evidence that supports their stance. A counterargument is also typically given as a way to counteract how “nay-sayers” would disagree with the writer. At the end of the essay, students will restate their argument and summarize their evidence.

How to Introduce Argumentative Writing: The Debate

Now that we know what to expect from argumentative writing, we can get into how to write an argumentative essay. You’ll want to start by introducing argumentative writing, which I liked to do through debates. Just like in an essay, to successfully debate a topic, students must do some investigation, choose a stance, and then argue their point in a meaningful way. Holding a class debate is a great place to start when introducing argumentative writing. Debating a topic verbally can actually be used as a brainstorming session before students ever even put pen to paper. For students new to argumentative writing, this takes some of the pressure off of jumping right into the writing process and helps them generate ideas.

There are a few ways you can use debates. For instance, you can choose a topic you’d like students to debate or let them choose a topic they’re already passionate about.

I liked to give students a few minutes to think through the topic and prep on their own, and then I partner them up. They can either debate the topic with their partner, or they can work together with their partner to debate another pair.

Depending on your class size, you could also split the class in half and make it a whole group debate. As long as students are researching or investigating in some way, choosing a stance, and finding reasons to back up their position, there is no wrong way to hold a debate in your class – and you can try out a few different formats to see what works best.

After the debates, it’s a great idea to debrief. This is a good time to bring in some key vocabulary and reinforce how to write an argumentative essay. For example, you can look over some of the evidence presented and ask students to rate the “strength” of the argument. You can also brainstorm a counterargument together.

How to Introduce Argumentative Writing: The Flash Draft

After students debate, they move on to the flash draft. A flash draft is essentially a giant brain dump. Students do not have to worry about spelling, grammar, organization, or even structure. They will simply be taking their thoughts from the debate and getting them down on paper.

One benefit to the flash draft is it removes the barrier of intimidation for a lot of students. For many kids, the actual work of starting to write can be daunting. A flash draft removes that intimidation of perfection and just requires something to be on the page. Again, the flash draft portion can be completely tailored to best suit your students and classroom. You can set a timer for a specific amount of time, you can provide students with an outline or guiding questions, or you can give them sentence stems to start.

If you have access to technology in your classroom, you can even let students verbalize their flash draft and use transcription technology to get it on paper.

Expanding Knowledge of Argumentative Writing

By now, you might be wondering when you’ll actually dive deeper into how to write an argumentative essay. That will start with a mini-lesson. These mini-lessons should cover the key parts of argumentative essays, like how to take a stance, ways to support your position, how to transition between thoughts, and even how to craft a counterargument.

You could have a mini-lesson before each flash draft to focus on a particular skill, or you can hold the mini-lesson after the flash draft and let students focus on that skill during revisions. During mini-lessons, I highly suggest using mentor texts, guided examples, or other reference materials. When it comes to writing, many students need to see the process in action, so modeling and having a place for them to reference will be super key to their success.

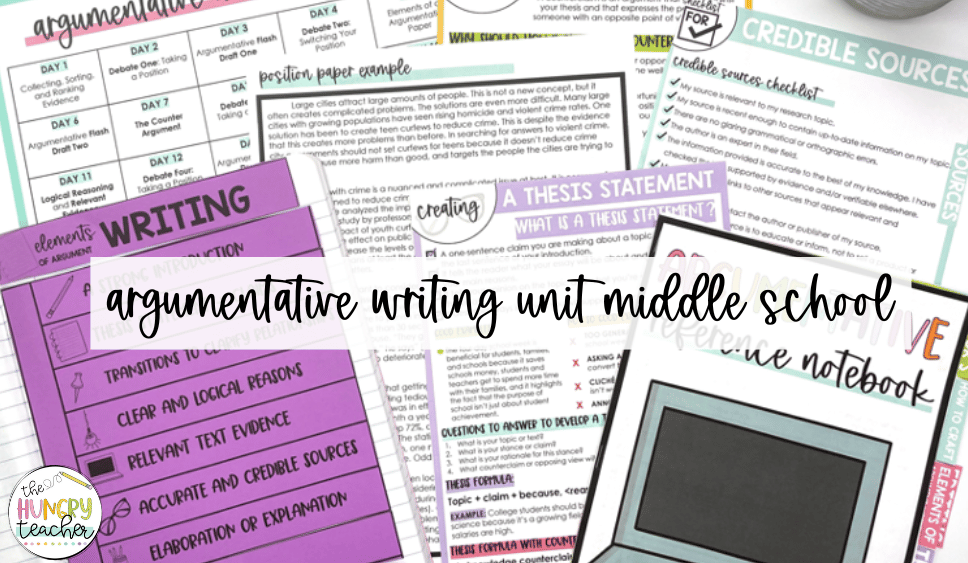

Argumentative Writing Unit for Middle School

Want support putting together your argumentative essay unit? My done-for-you Argumentative Writing Unit scaffolds how to write an argumentative essay for you and your students.

The unit includes 23 full lesson plans, slide presentations, notebook pages for students, teacher keys and examples, student references pages, and more for a well-rounded unit.

Plus, this unit goes through the exact process I talked about in the blog, using debate, flash drafts, and mini-lessons to scaffold students through the writing process.

- Read more about: Middle School Writing

You might also like...

Short Story Mentor Texts to Teach Narrative Writing Elements

Using Mentor Texts for Narrative Writing in Middle School ELA

Mentor Texts: When and How To Use Them in Your ELA Lessons

Get your free middle school ela pacing guides with completed scopes and sequences for the school year..

My ELA scope and sequence guides break down every single middle school ELA standard and concept for reading, writing, and language in 6th, 7th, and 8th grade. Use the guides and resources exactly as is or as inspiration for you own!

Meet Martina

I’m a Middle School ELA teacher committed to helping you improve your teaching & implement systems that help you get everything done during the school day!

Let's Connect

Member login.

PRIVACY POLICY

TERMS OF USE

WEBSITE DISCLAIMERS

MEMBERSHIP AGREEEMENT

© The Hungry Teacher • Website by KristenDoyle.co • Contact Martina

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to this park navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to this park information section

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Alerts in effect, the power of an argument - lesson plan.

Last updated: December 13, 2017

Park footer

Contact info, mailing address:.

143 S. 3rd Street Philadelphia, PA 19106

215-965-2305

Stay Connected

Can You Convince Me? Developing Persuasive Writing

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

Persuasive writing is an important skill that can seem intimidating to elementary students. This lesson encourages students to use skills and knowledge they may not realize they already have. A classroom game introduces students to the basic concepts of lobbying for something that is important to them (or that they want) and making persuasive arguments. Students then choose their own persuasive piece to analyze and learn some of the definitions associated with persuasive writing. Once students become aware of the techniques used in oral arguments, they then apply them to independent persuasive writing activities and analyze the work of others to see if it contains effective persuasive techniques.

Featured Resources

From theory to practice.

- Students can discover for themselves how much they already know about constructing persuasive arguments by participating in an exercise that is not intimidating.

- Progressing from spoken to written arguments will help students become better readers of persuasive texts.

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 4. Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes.

- 5. Students employ a wide range of strategies as they write and use different writing process elements appropriately to communicate with different audiences for a variety of purposes.

Materials and Technology

- Computers with Internet access

- PowerPoint

- LCD projector (optional)

- Chart paper or chalkboard

- Sticky notes

- Persuasive Strategy Presentation

- Persuasion Is All Around You

- Persuasive Strategy Definitions

- Check the Strategies

- Check the Strategy

- Observations and Notes

- Persuasive Writing Assessment

Preparation

Student objectives.

Students will

- Work in cooperative groups to brainstorm ideas and organize them into a cohesive argument to be presented to the class

- Gain knowledge of the different strategies that are used in effective persuasive writing

- Use a graphic organizer to help them begin organizing their ideas into written form

- Apply what they have learned to write a persuasive piece that expresses their stance and reasoning in a clear, logical sequence

- Develop oral presentation skills by presenting their persuasive writing pieces to the class

- Analyze the work of others to see if it contains effective persuasive techniques

Session 1: The Game of Persuasion

Home/School Connection: Distribute Persuasion Is All Around You . Students are to find an example of a persuasive piece from the newspaper, television, radio, magazine, or billboards around town and be ready to report back to class during Session 2. Provide a selection of magazines or newspapers with advertisements for students who may not have materials at home. For English-language learners (ELLs), it may be helpful to show examples of advertisements and articles in newspapers and magazines.

Session 2: Analysis of an Argument

Home/School Connection: Ask students to revisit their persuasive piece from Persuasion Is All Around You . This time they will use Check the Strategies to look for the persuasive strategies that the creator of the piece incorporated. Check for understanding with your ELLs and any special needs students. It may be helpful for them to talk through their persuasive piece with you or a peer before taking it home for homework. Arrange a time for any student who may not have the opportunity to complete assignments outside of school to work with you, a volunteer, or another adult at school on the assignment.

Session 3: Persuasive Writing

Session 4: presenting the persuasive writing.

- Endangered Species: Persuasive Writing offers a way to integrate science with persuasive writing. Have students pretend that they are reporters and have to convince people to think the way they do. Have them pick issues related to endangered species, use the Persuasion Map as a prewriting exercise, and write essays trying to convince others of their points of view. In addition, the lesson “Persuasive Essay: Environmental Issues” can be adapted for your students as part of this exercise.

- Have students write persuasive arguments for a special class event, such as an educational field trip or an in-class educational movie. Reward the class by arranging for the class event suggested in one of the essays.

Student Assessment / Reflections

- Compare your Observations and Notes from Session 4 and Session 1 to see if students understand the persuasive strategies, use any new persuasive strategies, seem to be overusing a strategy, or need more practice refining the use of a strategy. Offer them guidance and practice as needed.

- Collect both homework assignments and the Check the Strategy sheets and assess how well students understand the different elements of persuasive writing and how they are applied.

- Collect students’ Persuasion Maps and use them and your discussions during conferences to see how well students understand how to use the persuasive strategies and are able to plan their essays. You want to look also at how well they are able to make changes from the map to their finished essays.

- Use the Persuasive Writing Assessment to evaluate the essays students wrote during Session 3.

- Calendar Activities

- Strategy Guides

- Lesson Plans

- Student Interactives

The Persuasion Map is an interactive graphic organizer that enables students to map out their arguments for a persuasive essay or debate.

This interactive tool allows students to create Venn diagrams that contain two or three overlapping circles, enabling them to organize their information logically.

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

Teacher Off Duty

Resources to help you teach better and live happier

My Favorite Lesson Plan for Teaching Claim, Evidence, and Reasoning

August 29, 2018 by Jeanne Wolz 2 Comments

Let’s face it. Teaching argumentative writing is hard .

If you’re looking for a full argumentative writing unit plan , I’ve got you covered–>

It’s not that teenagers aren’t good at arguing. Teenagers are very good at arguing. In fact, they may be the people that practice arguing the most.

The challenge lies in learning the different parts of a basic argument–the claim, the evidence, and the reasoning–when each of them are such abstract concepts. By understanding what each of them are, we’re able to critique arguments and make our own better. But without a concrete way to talk about them, it’s like gesturing wildly at a class and hoping they’ll catch your drift (maybe that’s half the reason argumentative units are so exhausting…).

What I knew I needed was some sort of analogy, some visual for students that we could keep revisiting each time we reinforced these ideas. I went through several years of thinking about it before I finally came up with something that seemed to work.

I thought some sort of hook analogy might work–maybe a visual with strings and clips to show how reasoning attaches your evidence to your claim. I followed a fantastic Lucy Calkins lesson once where I wrote evidence on pieces of paper and lined them up on the floor, encouraging students to explain how each piece of evidence got me from claim a to claim b (which magically gave me powers to hop along the evidence). This was an effective one-off lesson, but it was difficult to revisit.

And then, one year it came to me. An analogy to revisit over and over again. That analogy was:

Making an argument is like taking your reader on a roller coaster.

Ok, ok, it may not seem like much, but I found there was a lot of value to be squeezed out of this visual.

I wanted to share with you how I use it so that maybe you can get some ideas on how to make these abstract-logic-intensive units a little more concrete, too.

Here’s what I do to introduce it:

Table of Contents

Claims, Evidence, and Reasoning Introduction Lesson Plan

Mini-lesson: explain the analogy.

I explain: “In order for your reader to stay with you, you need to strap him into that roller coaster argument properly for the entire time. How do you do that?

Stating your claim is like sitting your reader down on your roller coaster. It’s your first step.

Then, you give evidence. Your evidence is like putting on one strap of the seatbelt.

Your reasoning is like putting on the other strap.

Mentioning your claim at the end of this process is like snapping it all together.

And each part is crucial to keep your reader from falling off your thinking.

What do you think happens if you forget one of these steps?

Yup. You gotta have it all in order for your reader to stay with you.”

Sometimes, as I’m explaining this, I even act it out with a back pack and a chair to make it even more visual. I act out sitting in the chair (for stating your claim), putting on one strap (for introducing evidence), and putting on the other strap (for using reasoning to connect it back to the claim). After introducing the comment, I also like to give an example argument for students as I’m acting it out so they can start identifying each part of the argument.

Work-time: Act it Out as Students Make Arguments

After explaining it, we practice. I like to follow it up with verbal arguments with an activity like philosophical chairs so students can have repeated opportunities to both hear examples of arguments and try them themselves.

As students make their arguments, I continue to act it out. Students talk, and I follow along with the motions.

If they miss a step (which they almost always do in the beginning), I milk it. I yell and fall off the chair and make as dramatic a scene out of it as I can). Afterwards, we talk about what they forgot to do that made me fall off their coaster/argument and die.

And then we try again and repeat!

Extension: Have Students Act it Out for Each Other

After you’ve acted it out a couple times, have the rest of the class act out what they hear.

So as students hear the person speaking state a claim, they all sit down. As the person gives some evidence, they put on a strap, etc. And if they forget a step and finish….well, you may want to warn your neighboring classrooms. This can help students tune into the structure of others’ arguments in addition to helping keep each other accountable.

Twist: Invert the Lesson

I’ve actually begun to move the mini-lesson to the middle of this lesson. I’ve found it helps for students to create their own arguments before we talk about argument structure, because it gives context for talking about Claim, Evidence, and Reasoning. Plus, it honors the knowledge that students already have about making arguments–because they have a lot . So we start Philosophical Chairs, stop 1/3 through, chat about roller coasters, and then continue on. It’s a lot for a 45 minute period, but doable.

Click here if you want my full lesson plan, powerpoint, and handout that I use for introducing this analogy with philosophical chairs–complete with dramatic pictures of cartoon people flying off of roller coasters.. (This lesson actually comes from my argumentative unit, which will be released on TPT in September. If you’d be interested in hearing more about that unit and when it’s available, click here!)

Reinforce it Throughout the Unit

For the rest of the unit, I keep coming back to this analogy. We use it to talk about weak evidence (puny straps made of yarn) and strong evidence (steel bars), as well as the need for reasoning to match the strength of the evidence (uneven straps are awkward). When I give feedback to students, I always put it back in the context of the roller coaster. By the end, the idea is that the lack of a claim, evidence, or reasoning would make anyone in class scream (and for once, not just me!)—or at the very least, that everyone is much more aware of it.

________________

And that’s that! It’s become one of my favorite lessons in the argumentative unit, because no matter how crazy my students look at me the first time we talk about it, we’ve been able to come back to it over and over again during the unit. It’s given us a way to make something visual that always seems incredibly, frustratingly abstract.

Pin this to remember!

In the meantime, let me know in the comments below if you’ve got tips for teaching Claims, Evidence, and Reasoning, or if you were able to try this with your students. It seriously makes my day to hear from you, and I love hearing stories and new ideas!!

Some other resources you may be interested in:

This lesson is actually part of a full unit plan you can find here . One of my all-time favorite units I’ve ever taught, this argumentative unit starts with students identifying an issue they care most about, and then identifying who they can write to to change it. The rest of the 25, CCSS-aligned lessons take them through writing letters that they’ll mail at the end of the unit. Teach students how to argue well while learning to use their voice to make real change. Check it out here!

A few of my Pinterest Boards in particular (or all of them ):

Teaching Writing Pinterest Board

ELA Resources Pinterest Board

Lesson Ideas Pinterest Board

Social Studies Resources Pinterest Board

Share this:

Thank you!!! This is amazing – I really appreciate it!! 🙂

Yay–thanks for your feedback, Tara! I hope your students enjoy!!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Looking for something.

- Resource Shop

- Partnerships

Information

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

New Teacher Corner

New teachers are my favorite teachers..

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

10 Ways to Teach Argument-Writing With The New York Times

By Katherine Schulten

- Oct. 5, 2017

Updated, Feb. 2020

How can writing change people’s understanding of the world? How can it influence public opinion? How can it lead to meaningful action?

Below, we round up the best pieces we’ve published over the years about how to use the riches of The Times’s Opinion section p to teach and learn.

We’ve sorted the ideas — many of them from teachers — into two sections. The first helps students do close-readings of editorials and Op-Eds, as well as Times Op-Docs, Op-Art and editorial cartoons. The second suggests ways for students to discover their own voices on the issues they care about. We believe they, too, can “write to change the world.”

Ideas for Reading Opinion Pieces

1. Explore the role of a newspaper opinion section.

How would your students describe the differences between the news sections of a newspaper and the opinion section? What do they have in common? How do they differ? Where else in newspapers are opinions — for instance, in the form of reviews or personal essays — often published?

Bring in a few print copies of a newspaper, whether The Times or a local or school paper, and have your students work in small groups to contrast a news page with an opinion page and see what they discover.

Though this piece, “ And Now a Word From Op-Ed ,” is from 2004, it still provides a useful and quick overview of The Times’s Opinion section, even if the section then was mostly a print product. It begins this way:

Here at the Op-Ed page, there are certain questions that are as constant as the seasons. How does one get published? Who chooses the articles? Does The Times have an agenda? And, of course, why was my submission rejected? Now that I’ve been Op-Ed editor for a year, let me try to offer a few answers.

This 2013 article, “ Op-Ed and You ,” also helps both readers of the section, and potential writers for it, understand how Times Opinion works:

Anything can be an Op-Ed. We’re not only interested in policy, politics or government. We’re interested in everything, if it’s opinionated and we believe our readers will find it worth reading. We are especially interested in finding points of view that are different from those expressed in Times editorials. If you read the editorials, you know that they present a pretty consistent liberal point of view. There are lots of other ways of looking at the world, to the left and right of that position, and we are particularly interested in presenting those points of view.

After students have read one or both of these overviews, invite them to explore the Times’s Opinion section , noting what they find and raising questions as they go. You might ask:

• What pieces look most interesting to you? Why?

• What subsections are featured in the links across the top of the section (“Columnists”; “Series”; “Editorials”; “Op-Ed”; “Letters”; etc.) and what do you find in each? How do they seem to work together?

• How do you think the editors of this section decide what to publish?

• What role does this section seem to play in The Times as a whole?

• Would you ever want to write an Op-Ed or a letter to the editor? What might you write about?

If your students are confused about where and how news and opinion can sometimes bleed together, our lesson plan, News and ‘News Analysis’: Navigating Fact and Opinion in The Times , can help.

And to go even deeper, this lesson plan from 2010 focuses on a special section produced that year, “ Op-Ed at 40: Four Decades of Argument and Illustration .” It helps students understand the role the Op-Ed page has played at The Times since 1970, and links to many classic pieces.

2. Know the difference between fact and opinion.

In our lesson plan Distinguishing Between Fact and Opinion , you’ll find activities students can use with any day’s Times to practice.

For instance, you might invite them to read an Op-Ed and underline the facts and circle the opinion statements they find, then compare their work in small groups.

Or, read a news report and an opinion piece on the same topic and look for the differences. For example, which of the first paragraphs below about the shooting in Las Vegas is from a news article and which is from an opinion piece? How can they tell?

Paragraph A: After the horrific mass shooting in Las Vegas, the impulse of politicians will be to lower flags, offer moments of silence, and lead a national mourning. Yet what we need most of all isn’t mourning, but action to lower the toll of guns in America. (From “ Preventing Mass Shootings Like the Vegas Strip Attack ”) Paragraph B: A gunman on a high floor of a Las Vegas hotel rained a rapid-fire barrage on an outdoor concert festival on Sunday night, leaving at least 59 people dead, injuring 527 others, and sending thousands of terrified survivors fleeing for cover, in one of the deadliest mass shootings in American history. (From “ Multiple Weapons Found in Las Vegas Gunman’s Hotel Room ”)

3. Analyze the use of rhetorical strategies like ethos , pathos and logos.

Do your students know what ethos , pathos and logos mean? The video above, “ What Aristotle and Joshua Bell Can Teach Us About Persuasion ,” can help. We use it in this lesson plan , in which students explore the use of these rhetorical devices via the Op-Ed “ Rap Lyrics on Trial ” and more. The lesson also helps students try out their own use of rhetoric to make a persuasive argument.

In the post, we quote a New Yorker article, “The Six Things That Make Stories Go Viral Will Amaze, and Maybe Infuriate, You,” that explains the strategies in a way that students may readily understand:

In 350 B.C., Aristotle was already wondering what could make content — in his case, a speech — persuasive and memorable, so that its ideas would pass from person to person. The answer, he argued, was three principles: ethos, pathos, and logos. Content should have an ethical appeal, an emotional appeal, or a logical appeal. A rhetorician strong on all three was likely to leave behind a persuaded audience. Replace rhetorician with online content creator, and Aristotle’s insights seem entirely modern. Ethics, emotion, logic — it’s credible and worthy, it appeals to me, it makes sense. If you look at the last few links you shared on your Facebook page or Twitter stream, or the last article you e-mailed or recommended to a friend, chances are good that they’ll fit into those categories.

Take the New Yorker’s advice and invite them to choose viral content from their social networks and identify ethos , pathos and logos at work.

Or, use the handouts and ideas in our post An Argument-Writing Unit: Crafting Student Editorials , in which Kayleen Everitt, an eighth-grade English teacher, has her students take on advertising the same way.

Finally, if you’d like a recommendation for a specific Op-Ed that will richly reward student analysis of these elements, Kabby Hong, a teacher at Verona Area High School in Wisconsin, who will be our guest on our “Write to Change the World” webinar, recommends Nicholas Kristof’s column “ If Americans Love Moms, Why Do We Let Them Die? “

4. Identify claims and evidence.

The Common Core Standards put argument front and center in American education, and even young readers are now expected to be able to identify claims in opinion pieces and find the evidence to support them.

We have a number of lesson plans that can help.

First, Constructing Arguments: “Room for Debate” and the Common Core Standards , uses an Opinion feature that, though now defunct, can still be a great resource for teachers. Use the archives of Room for Debate , which featured succinct arguments on interesting topics from a number of points of view, to introduce students to perspectives on everything from complex geopolitical or theological topics to whether people are giving Too Much Information in today’s Facebook world .

We also have two comprehensive lesson plans — For the Sake of Argument: Writing Persuasively to Craft Short, Evidence-Based Editorials and I Don’t Think So: Writing Effective Counterarguments — that were written to support students in crafting their own editorials for our annual contest . In both, we first introduce readers to “mentor texts,” from The Times and elsewhere, that help them see how effective claims, evidence and counterclaims function in making a strong argument.

Finally, if you’re looking for a fun way to practice, we often hear from teachers that our What’s Going On in This Picture? feature works well. To participate, students must make a claim about what they believe is “going on” in a work of Times photojournalism stripped of its caption, then come up with evidence to support what they say.

5. Adopt a columnist.

This Is What a Refugee Looks Like

If elena, 14, is sent back to her country, she may be murdered..

VISUAL AUDIO Nick debarks plane B-roll streets of Mexico, B-roll rural Mexico, on truck, train passing Nick [VO]: We’re in Southern Mexico on the Guatemala-Mexico border, an area where you have hundreds of thousands of Central Americans, in many cases aiming to get to the US. B-roll people getting on bus Nick [VO]: These are not economic migrants. These are people who are fleeing gangs and sexual violence. Nick talking to women outside refugee agency INTV Nick B-roll Tapachula sky Nick [VO]:The homicide rates in Central America are some of the highest in the world. If you or I were there, we would be fleeing this as well. INSERT TITLE CARD Nick greeting Brenda Nick walks up steps to apartment Nick: Hola Brenda, Buenos dias. Brenda: Buenos dia, que tal? Nick [VO]: One of the people we met, Brenda, has applied for refugee status for her and for her daughters and she’s waiting. Nick meets Brenda’s children Translator: Hello. What’s your name? Kimberly: Kimberly. Nick: Kimberly, okay. Translator: She’s Kimberly. Brenda: Nestor Nick: Nestor! How are you? Inside Brenda’s apartment Nick talking to Elena Brenda: She’s Zoila Elena Nick: Elena, you are 14? Is that right? Translator: You’re 14 years old, right? Elena: Si. Nick: Kimberly… once? Elena: Doce. Nick: Doce! Translator: It’s twelve now. Nick: Okay. ElenaB-roll washing up in apartment, preparing chicken feet Her mother joins her INTV Elena on stairs Elena: My family calls me Elena. The house where I lived was in Honduras. Before, in our neighborhood, you could go out at whatever time you wanted, you could go out to play. But now these gangs arrived, the men from the 18th Street Gang, they started to establish rules. Everything was different, and that’s when our mother brought us here. Nick interviewing Elena inside house CU Brenda crying Nick: There’s special dangers for girls growing up from the maras . Did you have any girlfriends who were attacked by boys, did you worry about that happening to you? Elena: Yes I know someone. She was dating someone from the 18th Street Gang. They forced her by saying that if she didn’t join them… they would kill her whole family. So that nothing would happen to her family she had to do it. So they arranged to meet at the river. And she went to the river. She ended up getting raped. And when she left the river. she came out with a bullet in here and had to walk naked to her house. Well from then on we didn’t hear from her again. Nick: So you saw her coming from the river, naked, bleeding from a gunshot wound in the stomach? Elena: I was just like this, and I was shocked. But I couldn’t do anything because the gangsters were there and… if they would see us helping her, something could have happened to us. Nick: Did the gang members ever pay attention to you in ways that made you feel dangerous, that they might do the same thing to you? Elena: And there was one that told me that if I didn’t go out with him, he was going to kill my mom and dad. So I sent him a text message saying yes, agreeing to it. Nick: And how old were you when he wanted you to be his girlfriend? Elena: Eleven and a half years old. Translator: Eleven years. Nick: And you were able to say no to him then? Elena: No... because if I didn’t agree... he would have killed my family. Because he forced me.... even though I did not want to. So, I had to say yes... in order to protect my family. B-roll border checkpoint INTV Nick Nick [VO]: The United States and Mexico together have sent back 800,000 adults over the last 5 years, and 40,000 children to just those 3 countries of Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. Brenda and her kids inside apartment Brenda: I think I’m moving forward, whether or not I have to go through, what I already went through. I don’t have anywhere else to go. Nick [VO]: If they’re sent back, her daughters will be perhaps killed and preyed upon by the gangs. Nick in taxi Brenda’s family in apartment Nick [VO]: What would you do if you were Elena? Stay in Honduras and be forced into a relationship with a gang member? I doubt it. Elena in apartment with family INTV Elena Elena: And now we are moving from one place to another, and people think we are less important because we are immigrants. But they don’t know what we are running from.

We have heard from many teachers over the years that a favorite assignment is to have students each “adopt” a different newspaper columnist, and follow him or her over weeks or months, noting the issues they focus on and the rhetorical strategies they use to make their cases. Throughout, students can compare what they find — and, of course, apply what they learn to their own writing.

One teacher, Charles Costello, wrote up the details of his yearlong “Follow a Columnist” project for us. If you would like to try it with The Times, here are the current Op-Ed columnists:

Charles M. Blow

Jamelle Bouie

David Brooks

Frank Bruni

Roger Cohen

Gail Collins

Ross Douthat

Maureen Dowd

Thomas L. Friedman

Michelle Goldberg

Nicholas Kristof

Paul Krugman

David Leonhardt

Farhad Manjoo

Jennifer Senior

Bret Stephens

6. Explore visual argument-making via Times Op-Art, editorial cartoons and Op-Docs.

The New York Times regularly commissions artists and cartoonists to create work to accompany Opinion pieces. How do illustrations like the one above add meaning to a text, while grabbing readers’ attention at the same time? What can students infer about the argument being made in an Op-Ed article by looking at the illustration alone?

In this lesson plan , students investigate how art works together with text to emphasize a point of view. They then create their own original illustrations to go with a Times editorial, Op-Ed article or letter to the editor. We also suggest that they can illustrate an Opinion piece or letter to the editor that does not have an illustration associated with it.

Recently, Clara Lieu, a teacher at the Rhode Island School of Design, told us how she uses that very idea to help her student-artists to create their own pieces. To see some of their work, check out “ Finding Artistic Inspiration in The New York Times’s Opinion Section .”

If your students would like to go further and create their own editorial cartoons, we offer an annual student contest . Invite your students to check out the work of this year’s winners for inspiration. We also have a lesson plan, Drawing for Change: Analyzing and Making Political Cartoons , to go with it.

Another way to use visual journalism to teach argument-making? Use Op-Docs , The Times’s short documentary series (most under 15 minutes), that touches on issues like race and gender identity, technology and society, civil rights, criminal justice, ethics, and artistic and scientific exploration — issues that both matter to teenagers and complement classroom content.

Every Friday during the school year, we host a Film Club in which we select short Op-Docs we think will inspire powerful conversations — and then invite teenagers and teachers from around the world to have those conversations here, on our site.

And for a great classroom example of how this might work in practice, check out Using an Op-Doc Video to Teach Argumentative Writing , a Reader Idea from Allison Marchetti, an English teacher at Trinity Episcopal School in Richmond, Va. She details how her students analyzed the seven-minute film “China’s Web Junkies” to see how the filmmakers used evidence to support an argument, including expert testimony, facts, interview, imagery, statistics and anecdotes.

Ideas for Writing Opinion Pieces

7. Use our student writing prompts to practice making arguments for a real audience.

Does Technology Make Us More Alone?

Is It Ethical to Eat Meat?

Is It O.K. for Men and Boys to Comment on Women and Girls on the Street?

Are Some Youth Sports Too Intense?

Does Reality TV Promote Dangerous Stereotypes?

When Do You Become an Adult?

Is America Headed in the Right Direction?

Every day during the school year we invite teenagers to share their opinions about questions like these, and hundreds do, posting arguments, reflections and anecdotes to our Student Opinion feature. We have also curated a list drawn from this feature of 401 Prompts for Argumentative Writing on an array of topics like technology, politics, sports, education, health, parenting, science and pop culture.

Teachers tell us they use our writing prompts because they offer an opportunity for students to write for an “authentic audience.” But we also consider our daily questions to be a chance for the kind of “low-stakes” writing that can help students practice thinking through thorny questions informally.

We also call out our favorite comments weekly via our Current Events Conversation feature. Will your students’ posts be next?

8. Participate in our annual Student Editorial Contest.

What issues matter most to your students?

Every year, we invite teenagers to channel their passions into formal pieces : short, evidence-based persuasive essays like the editorials The New York Times publishes every day.

The challenge is pretty straightforward. Choose a topic you care about, gather evidence from sources both within and outside of The New York Times, and write a concise editorial (450 words or less) to convince readers of your point of view.

Our judges use this rubric (PDF) for selecting winners to publish on The Learning Network.

And at a time when breaking out of one’s “filter bubble” is more important than ever, we hope this contest also encourages students to broaden their news diets by using multiple sources, ideally ones that offer a range of perspectives on their chosen issue.

This school year, as you can see from our 2019-20 Student Contest Calendar , the challenge will run from Feb. 13 to March 31, 2020. You can find the submission form and all the details here .

To help guide this contest, we have published two additional ideas from teachers:

• In “ A New Research and Argument-Writing Approach Helps Students Break Out of the Echo Chamber, ” Jacqueline Hesse and Christine McCartney describe methods for helping students examine multiple viewpoints and make thoughtful, nuanced claims about a range of hot-button issues.

• In “ Helping Students Discover and Write About the Issues that Matter to Them ,” Beth Pandolpho describes how she takes her students through the process of finding a topic for our annual Student Editorial Contest, then writing, revising and submitting their final drafts.

9. Take advice from writers and editors at the Times’s Opinion section.

How can you write a powerful Op-Ed or editorial?

Well, over the years, many Times editors and writers have given the aspiring opiners advice. In the video above, for instance, Andrew Rosenthal, in his previous role as Editorial Page editor, detailed seven pointers for the students who participate in our annual Editorial Contest.

In 2017 Times Op-Ed columnist Bret Stephens wrote his own Tips for Aspiring Op-Ed Writers .

And on our 2017 webinar , Op-Ed columnist Nicholas Kristof suggested his own ten ideas. (Scroll down to see what they are, as well as to find related Op-Ed columns.)

Finally, if you’d like to get a letter to the editor published, here is what Tom Feyer, the longtime head of that section, recommends. Until Feb. 16, 2020, that section is offering a special letter-writing challenge for high school students . Submit a letter to the editor in response to a recent news article, editorial, column or Op-Ed essay, and they will pick a selection of the best entries and publish them.

10. Use the published work of young people as mentor texts.

In 2017, five students of Kabby Hong, the teacher who joined us for our Oct. 10 webinar, were either winners, runners-up or honorable mentions in our Student Editorial Contest.

How did he do it? First, he helps his students brainstorm by asking them the questions on this sheet . (The first page shows his own sample answers since he models them for his students.)

Then, he uses the work of previous student winners alongside famous pieces like “ Letter from Birmingham Jail ” to show his class what effective persuasive writing looks like. Here is a PDF of the handout Mr. Hong gave out last year, which he calls “Layering in Brushstrokes,” and which analyzes aspects of each of these winning essays:

•“ In Three and a Half Hours, an Alarm Will Go Off ”

•“ Redefining Ladylike ”

•“ Why I, a Heterosexual Teenage Boy, Want to See More Men in Speedos ”

Another great source of published opinion writing by young people? The Times series “ On Campus .” Though it is now discontinued, you can stil read essays by college students on everything from “ The Looming Uncertainty for Dreamers Like Me ” to “ Dropping Out of College Into Life .”

Update: Links from Our 2017 Webinar

On our 2017 webinar (still available on-demand), Nicholas Kristof talked teachers through ten ways anyone can make their persuasive writing stronger. Here is a list of his tips, along with the columns that relate to each — though you’ll need to watch the full webinar to hear the stories and examples that illustrate them.

Nicholas Kristof’s Ten Tips for Writing Op-Eds

1. Start out with a very clear idea in your own mind about the point you want to make.

Related: Preventing Mass Shootings Like the Vegas Strip Attack

2. Don’t choose a topic, choose an argument.

Related: On Death Row, but Is He Innocent?

3. Start with a bang.

Related: If Americans Love Moms, Why Do We Let Them Die?

4. Personal stories are often very powerful to make a point.

Related: This is What a Refugee Looks Like

5. If the platform allows it, use photos or video or music or whatever.

Related: The Photos the U.S. and Saudi Arabia Don’t Want You to See

6. Don’t feel the need to be formal and stodgy.

Related: Meet the World’s Leaders, in Hypocrisy

7. Acknowledge shortcomings in your arguments if the readers are likely to be aware of them, and address them openly.

Related: A Solution When a Nation’s Schools Fail

8. It’s often useful to cite an example of what you’re criticizing, or quote from an antagonist, because it clarifies what you’re against.

Related: Anne Frank Today Is a Syrian Girl

9. If you’re really trying to persuade people who are on the fence, remember that their way of thinking may not be yours.

Related: We Don’t Deny Harvey, So Why Deny Climate Change?

10. When your work is published, spread the word through social media or emails or any other avenue you can think of.

Related: You can find Nicholas Kristof on Twitter , Facebook , Instagram , his Times blog , and via his free newsletter .

- Apr 16, 2020

Argumentative Writing: Debates in Middle School

Updated: Apr 29, 2020

Almost all standards across the country call for students to do some sort of argumentative writing and analysis . I see lots of teachers ask how to get their students to write argumentative essays. Well, my students don't. Throughout the school year my students write a research essay and a literary analysis essay...to put them through another essay is torture for me and them. So, instead, we do debates! Read about how I approach debating with my 6th graders.

Introduction

My school district has a high school debate team that takes it very seriously. My school is lucky enough to host some of the debates right in my own classroom! (It's a very small district). I always ask the teachers who run the debate club if my students can watch. It's a great experience for them to see students who take debate very seriously, even though the topic may be way over their heads!

They simply observe these debates and we don't get into them a whole lot until we start the unit (which is usually much later than when they see the debates). We discuss what they noticed. One of the things they notice is how prepared the high schoolers are when they are in front of the class debating. This is a great segway into to the unit as they will be doing research and trying to be as formal as possible!

I also like to do some fun interactive activities like speed debating . I give them very basic topics to practice debating for a few minutes then switch off to debate with the next person. (Unfortunately, I couldn't do these for this current school year due to COV-ID closures).

Eventually, we dive into our digital notebook . We kick it off with observations of two debates I found on YouTube. I don't expect them to watch the entire debates. We discuss key terms as an introduction and then delve into those later.

Debate Basics

I will not call myself an expert at debates in the slightest, so I am happy I teach 6th grade to just give them the bare bones. I did some research of my own and spoke with the 8th grade teacher in my building to see what's typically expected in the upper grades and I scaled my information down to meet my 6th graders' needs.

We begin with pro/con article s from Newsela . These are a lifesaver! They are short and sweet and I have the students analyze the difference between the two "sides". Ultimately, they choose a side and briefly support it with text detail from the article.

They continue to use these types of articles to practice crafting claims. Normally, in an argumentative essay, this would be their thesis. I help them use debate terminology of affirmative and negative. I have them focus on three major points to craft their claims.

Next up is ethos, logos, and pathos . They do struggle with this because they've had NO exposure to this before they get to me. I like to use commercials to help with these concepts. I break down each one as a different lesson each day. I have them return to a pro/con article already read and look for evidence that could fit into each category. Following up to that, I have them create their own ethos, logos, and pathos.

Counterclaims and refutations are next and a cornerstone of debate. Students differentiate between strong and weak counterclaims and learn how to use specific language to refute.

Time to prep for the debate. I give the students a Google Form early in the unit to choose the topic they want. I limit their choices to four topics I already chose because I provide them with the research articles. You may want to go a different direction and let them choose their own topics and do their own research...my kiddos are not quite ready for that. Once they choose their topics, I try very hard to put them in the groups they want. They also choose what side they'd prefer. Unfortunately, they don't always get the side they want, but the research I provide gives them plenty to support each side.

There are about 4 students per group. Each group is a different side of a topic. So, one group of 4 is the affirmative to the question and the other group of 4 is the negative to the question.

The groups then spend time researching in the provided articles. Within their gathering of evidence, I have them get information for BOTH sides and try to match up evidence against each other. The goal being that when they do debate, they have researched the evidence from the other side, too, so they can refute it. My kids do struggle with this a bit, so I don't expect miracles...it's a tough concept to wrap their heads around.

They also spend time separating out the evidence, this way, students aren't overwhelmed and have specific evidence to focus on when they present. I also have them go back to see if they can add any logos, ethos, and pathos. They write opening and closing statements and prepare a notecard to have with them when they research.

I set up the debate with eight desks in front of the classroom facing the rest of the class. Each group goes to a side to debate. It is a little less formal than other debates, as I don't really time it; I just use my discretion.

They begin with the opening act. Then, the other side provides their first argument. The following group can rebut by using the steps of refutation learning earlier by raising their hand. I encourage them to use their evidence to rebut and to focus on what the other group said (we practice a bunch before, too).

The rest of the class fills out an assessment based on the debates they watched and "grade" the presentations. Then, I grade them!

This year, I am attempting this all through Zoom. Stay tuned! I will update here once I get to it...my students just started this unit last week. I may end up making smaller groups since I have less time with them and the plan is to hold the debates on Zoom.

Bottom Line

While many choose to do essays for the argumentative standards, I find debates to be more productive. This unit really works into Speaking and Listening standards, too and students, especially at this age, love to socialize so this is a great way to get them to do so! And since this is being done through distance learning this year, it's more important than ever!

Want this unit? Click below!

You can get a free lesson from this notebook here!

************

Want a custom bundle from me click below.

Teachers Pay Teachers Store

- Digital Classroom

Recent Posts

Spring Things! Fun with Poetry and Figurative Language

Text Structure Explanatory Writing: Creating a Dodecahedron

Why I Don't Do a Daily Reading Log: What I Do Instead

- Free Lessons All Year

- Pop Culture Lessons

- Literature Based Lessons

- Video Analyses

- AI For Teachers

- Summer Reading

- Read The Book

- Take The Course

- Schedule Live PD

Middle School & YA Lesson Plans

Our Middle School & YA lesson plans condense hundreds of hours of work into a simple, premium-quality lesson bundles. These plans boast the same qualities as our other products in that they are:

- Specifically focused on teaching rhetorical analysis and argumentative writing

- Fully aligned to the Common Core State Standards

- Designed to target skills pertinent to next-generation tests such as PARCC and SmarterBalanced via comparable learning tasks

- Structured around pedagogical strategies associated with the upper echelon of learner-centered teacher evaluation models such as Danielson and Marzano

- Grounded in the most popular works of literature taught in schools, rather than sporadic non-fiction

Our Middle School & YA Lesson Plan bundle includes thirty first-rate lesson plans focused on teaching argument, grounded in the following texts:

- Animal Farm by George Orwell

- Romeo & Juliet by William Shakespeare

- The Giver by Lois Lowry

- The Fault In Our Stars by John Green

- The Outsiders by S.E. Hinton

- The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

- The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

All lessons are provided in both PDF and 100% editable Word Doc format, and include any pertinent handouts. Lesson plans are delivered digitally and immediately via email. Save yourself countless hours and worlds of energy while bringing the best in argument instruction to your students!

Purchase this bundle for $39.99 today and save $19.98 ! Take advantage of these savings and buy now!

If paying with a purchase order, click here to request a quote!

A number of these units are also available for purchase individually. All individual units include five lessons for teaching rhetorical analysis with the selected core text. As always, materials are sent immediately via email in both PDF and Word Doc format. Purchase any of the individual units below for only $9.99 each!

Join the TeachArgument Community to gain instant access to all of our pop culture lesson plans and teaching resources now!

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

Save 10% today on your lessons using the code GIVEME10

Middle School Persuasive Writing Lessons

Finding engaging and rigorous persuasive writing lessons should not be a challenge to find. Unfortunately, not all writing curriculums and activities draw the attention of our students and encourage their engagement. Consequently, the lessons they learn in these classes are not as solid or memorable as they could be.

From the time we are old enough to talk, persuasion is a skill that we use on a regular basis. As we get older, the stakes become much higher than a simple “Let me have an extra cookie after dinner tonight, please.” From the everyday discussions with a partner about where to go on vacation to the much more significant ones like convincing a boss to give you a raise, persuasion is a part of all of our lives and a skill that has a tangible and significant impact.

Making sure our students have a solid foundation in persuasion and these persuasive writing lessons will help set them up for success in the future.

Let’s look at three persuasive writing lessons that offer solid instruction while also being particularly engaging to your students.

Persuasive Writing Lessons

Persuasive Pitch Assignment

If your students like the TV show Shark Tank or Dragon’s Den , they will love this assignment. In it, students develop an idea of how to improve their school (e.g., installing recycling bins, creating a snack program, etc.), and then they pitch their idea to the judges (their classmates).

After watching all the presentations, students will vote on which idea they like best. This assignment is scaffolded into five different lessons. The familiar format, as well as the element of competition, encourages students to do their best and helps drive home the curricular lessons on persuasion.

Find the Persuasive Pitch Assignment on Shopify CAD or Teachers Pay Teachers USD .

Teacher Feedback

“My students loved the idea of Dragon’s Den style product pitches to learn persuasive techniques! They had a blast while watching the two show episodes and analyzing the products, as well as creating their own products and pitching them. They created excellent advertisements and came up with great ideas!”

Persuasive Writing – Michael vs. LeBron

Oftentimes the problem with persuasive writing lessons is that students don’t really care (or care much) about the topic about which they are writing. This is not the case with this lesson. In it, students practise gathering evidence from a podcast (an oral text) and use that evidence to support their writing.

After listening to the evidence presented by the podcast, students must decide who is the greatest basketball player of all time – LeBron James or Michael Jordan. By grabbing your students’ attention with a topic they are interested in and one that may be rather unexpected in the language arts classroom, you help students be excited and want to learn more about effective persuasive writing.

Find the Michael vs. LeBron Persuasive Writing lesson on Shopify CAD or Teachers Pay Teachers USD .

“Loved this persuasive writing unit so much! I have quite a few basketball fans in the class and so it was quite the hit. Thanks!”

Rant Writing Unit

Rant writing is an engaging way to bring public speaking and persuasive writing into the classroom. Students rant and complain to each other daily – why not channel that creative energy into some high-quality writing? By utilizing things that students are already engaged with and encouraging students to share their thoughts and opinions, this unit is an effective way to teach persuasive writing.

Whether you choose to use these lessons or something else, the importance of a solid foundation in persuasion cannot be overstated. Helping students remember the lessons they learn in your class going forward and throughout their lives sets them up for future success.

You can grab this Rant Writing Unit for free here .

“My communications class absolutely loved this activity and even asked at the end to do it again!! It was very engaging.”

Additional Resources

- Middle School Writing Lessons

- Creative Writing Lesson Plans

Related Posts

This FREE persuasive writing unit is

- Perfect for engaging students in public speaking and persuasive writing

- Time and energy saving

- Ideal for in-person or online learning

By using highly-engaging rants, your students won’t even realize you’ve channeled their daily rants and complaints into high-quality, writing!

Argumentative Writing Unit - Middle School

What educators are saying

Also included in.

Description

25 CCSS-aligned lessons walking students through writing passionate argumentative letters about an issue they care most about, one letter of which they will mail at the end of the unit.

The unit begins by exploring how teen activists have changed the world by speaking out about what they believe in, and then guides students through identifying what they’d like to change in the world.

The remaining 5 weeks of lessons teach students Common Core argumentative skills, addressing the most common issues students struggle with argumentative writing: analyzing evidence, integrating quotes, evaluating reliable sources, including a counterargument, and many more.

The unit is meant not just to hone students’ argumentative skills, but also teach them how to exercise their voice. It was inspired by a unit I did with my own students right after the November 2016 elections—after which we received a signed letter response from President Barack Obama!

I would love for your students to experience the same excitement and reward for using their voice to speak out.

**Note - Save 20% by purchasing this unit within my 3-Unit Writing Unit Bundle! Check it out here and save.**

This 5-week, 200+ page unit includes:

-50 pages of detailed lesson plans (25 lessons in total)

-145-Slide Powerpoint

-35 pages of printables for scaffolding instruction and assessment

-Links to mentor texts

Each lesson plan includes:

-CCSS Standards

-Content Objectives

-Language Objectives--especially useful for your Emergent Multilinguals (ELLs), but benefit all students

-Mini-lesson--plan and slides

-Work-time--plan and slides

-Share-time--plan and slides

-Ideas, logs, and handouts for formative assessment

Each day's slides includes:

-Objectives--both content and language

-Visuals for mini-lesson

Skills covered by lesson plans include:

-Claim, evidence, and reasoning

-Connecting evidence to claim (reasoning)

-Including a variety of evidence

-Structuring logical body paragraphs

-Introductions

-Conclusions

-Coming up with research questions

-Evaluating reliable sources

-When to quote vs. paraphrase

-How to cite

-Writing counterarguments

This unit plan also includes the following products and bundles at a significantly discounted, bulk price:

- Research Lesson Bundle

- Revision and Peer Feedback Bundle (for Arg. Writing)

- Brainstorming and Outlining Bundle (for Arg. Writing)

- Organization and Structure Bundle (for Arg. Writing)

Individual lesson plans:

- Integrating Quotes Lesson

- Claims, Evidence, and Reasoning Lesson

- Argumentative Outline Lesson

- Brainstorming a Choice Topic for Argumentative Writing

- Counterargument Lesson Plan