- Memberships

- Employer opportunities

Explore our Memberships

Become a part of the FW family for as little as $1 per week.

Employer Opportunities

Turn words into action. Work with us to build a more diverse and inclusive workplace.

FW was founded in 2018 with a promise to help women connect, learn and lead.

Leadership Summit

Hear from notable women around the country on topics including leadership, business, finance, wellness and culture.

Two days of inspiring keynote speeches, panel discussions and interactive sessions.

- Publications

- Newsletters

How to ask for what you want

Catherine Brenner, Louise Adler and Sam Mostyn offered their advic...

Reclaiming your power at forty

Em Rusciano outlines four lessons we can all take from her own sei...

Making The Case: How To Successfully Argue For A Pay Rise

In our latest series, Making The Case, Future Women's arguer-in-ch...

There's No Place Like Home

Putting survivors of family violence at the centre of the story.

Gender equality in print

Books written and edited by the FW team.

- FW Masterclass Series

Platinum+ Emerging Leader

Change makers, fw masterclass.

Your next step as an effective leader.

A program for mid-career women and exceptional graduates to fast track their career journey.

A program designed for men who want to become better managers and leaders.

Connect with expert mentors and an advisory board of like-minded women to solve a professional challenge.

8 comebacks to 8 common criticisms of the gender pay gap

The only comebacks you'll ever need when dealing with a textbook Gender Pay Gap Denier.

By Lara Robertson

We’ve all been there: whether you’re having a heated discussion about gender equality in a Facebook comments section, or at the local pub, someone jumps in with a statement that is just so outrageously untrue that you need a killer comeback. (It’s not just men. Women do it too.) However, we’re not always on top of our game when such a moment arises, so we’ve put together a list of responses to eight common criticisms of the gender pay gap argument.

“If women were paid less than men everyone would be hiring women”

Fortunately, most employers don’t actively discriminate against women when when hiring or negotiating pay. However, the prevalence of unconscious bias means that both male and female employers are less likely to hire women , perceiving them to be less competent and reliable than men. Even when a woman is hired, she is usually offered a smaller starting salary than a man with the same credentials, and she is less likely to receive a pay rise or promotion.

“Women shouldn’t choose lower-paid jobs if they want to be paid more”

Although progress is certainly being made, women still face barriers to entering higher-paid, male-dominated industries such as STEM and finance. This ranges from being discouraged from studying certain subjects, to facing discrimination during the hiring process. It’s an interesting phenomenon that female-dominated industries such as childcare, teaching, nursing and social work are among the lowest-paid industries, while male-dominated industries are among the highest-paid. In fact, this is no coincidence. A key study conducted between 1950-2000, when the number of women in the workforce greatly increased, showed the average pay of the now female-dominated industries drastically decreased. This suggests that “women’s work” is greatly undervalued in society.

“Women aren’t being discriminated against. They’re just having children”

There’s no doubt that much of the gender pay gap can be attributed to the fact that women often take time off work or leave the workforce to start a family. However, women face what is known as the ‘motherhood penalty’ , which is a form of discrimination. When women in their twenties and thirties go for a job interview, they often face invasive questions about whether or not they’re planning to have children, which affects their likelihood of getting the job. Even worse, women who try to return to work after having a child find they are much less likely to be hired than childless women, childless men and fathers.

“The gender pay gap isn’t about discrimination”

Actually, a 2019 study by KPMG revealed gender discrimination is the single most significant component contributing to pay inequality in Australia.

The study found it accounts for 39 per cent of the pay gap, a jump from 29 per cent in 2014.

Other factors related to the gap include years not working due to interruptions, part-time employment and unpaid care and work.

The study found the economic impact of closing the gap is equivalent to $182 million each week.

In February 2023, the Australian Bureau of Statistics released data showing the national gender pay gap had dropped to 13.3%. In money terms, in Australia women earn, on average, 87 cents for every $1 earned by a man.

“Women just need to be more assertive”

Although women have been told to ‘lean in’ and become more assertive when it comes to putting their hand up for opportunities at work, negotiating salaries and asking for promotions, the reality is even when they are assertive, research out of the UK found they are 26 per cent less likely to succeed than men. Even worse, showing assertiveness can have a negative effect on a woman’s career trajectory, as their employer may start viewing them as being “too pushy”.

“Men are more logical, while women are more emotional”

Although women’s tendency to be more empathetic than men is often used to justify their prevalence in care giving industries such as nursing and teaching, a study by Harvard Business Review found that they actually also rank higher than men in 17 out of the top 19 leadership qualities including problem-solving and communication skills. So perhaps men are not ‘better’ than women in certain areas, and vice versa – maybe they’re just not given the same chances to succeed. In the 21st century, it’s time we stopped boxing people into outdated gender stereotypes. Just as men can be empathetic, women can also be logical. Men and women should have the same opportunities to pursue whatever career they want.

“People should be hired based on merit, not gender quotas”

If people were hired completely on their merit, you would probably see about a 50/50 split in most industries. Unfortunately, employers tend to hire based on an applicant’s perceived merit (unconscious bias comes into play here), which means many perfectly capable women are often overlooked in favour of a male applicant. Gender quotas have been criticised for privileging women on the basis of their gender, potentially creating negative outcomes for women who are seen by other employees to have been hired for their gender, rather than their merit. However, an experiment undertaken by The Conversation found that if employees were educated about gender discrimination in the field, quotas can help eradicate the biases that shape hiring decisions and encourage more women to put their hand up for a position.

“Women should just work harder”

If someone actually has the audacity to throw this one at you, the best thing you can do is laugh in their face and show them the following study. Gartner’s Global Talent Monitor measured the “discretionary effort” male and female employees are putting in at work. The data showed women were putting in a 7 per cent higher discretionary effort than their male colleagues.

Future Women is a club dedicated to the advancement of women through events, quality journalism and connecting like-minded women. To read more articles like this, sign up to become a member for less than the cost of a coffee per week.

Best Of Future Women

‘The choices that changed my career’ according to five leaders

Why Dr Julia Baird is searching for grace (and you should too)

In law, Grata Flos Matilda Greig went first

In medicine, Dr. Emma Constance Stone went first

In sport, Evonne Goolagong Cawley went first

In architecture, Ellison Harvie went first

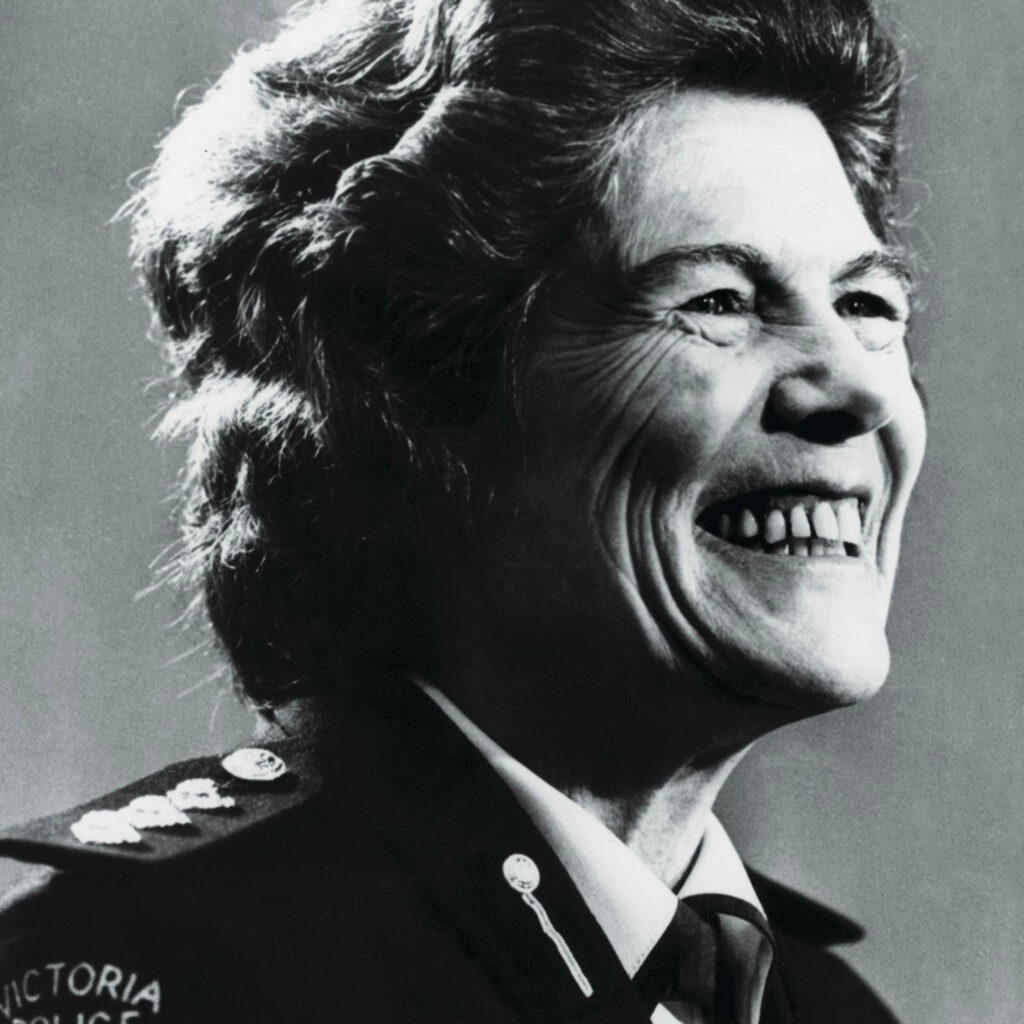

In policing, Grace Brebner went first

In politics, Enid Lyons went first

Your inbox just got smarter.

If you’re not a member, sign up to our newsletter to get the best of Future Women in your inbox.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Why Aren’t We Making More Progress Towards Gender Equity?

- Elisabeth Kelan

Research on how “gender fatigue” is holding us back.

Despite many of the advances we’ve made toward gender equality in the past few decades, progress has been slow. Research shows that one reason may be that many managers acknowledge that the bias exists in general but fail to recognize it in their daily workplace interactions. This “gender fatigue” means that people aren’t motivated to make change in their organizations. Through ethnographic studies and interviews across industries, the author identified several rationalizations managers use to deny gender inequality. First, they assume it happens elsewhere, at a competitor, for example, but not in their own organization. Second, they believe that gender inequality existed in the past but is no longer an issue. Third, they point to the initiatives to support women as evidence that inequality has been addressed. Last, when they do see incidents of discrimination, they reason that the situation had nothing to do with gender. Until we stop denying inequality exists in our own organizations, it will be impossible to make progress.

Organizations have worked towards achieving gender equality for decades. They’ve invested resources into developing women’s careers. They’ve implemented bias awareness training. Those at the top, including many CEOs, have made public commitments to make their workplaces more fair and equitable. And, still, despite all of this, progress towards gender equality has been limited. In fact, many managers struggle to recognize gender inequalities in daily workplace interactions.

- EK Elisabeth Kelan is a Professor of Leadership and Organisation and a Leverhulme Trust Major Research Fellow at Essex Business School at University of Essex in the United Kingdom.

Partner Center

Opposition to gender equality around the world is connected, well funded and spreading. Here’s what you need to know about the anti-gender movement

By Kate Walton, for CNN

Editor’s note: This story is part of As Equals , CNN’s ongoing series on gender inequality. For information about how the series is funded and more, check out our FAQs .

Over the past several decades, in every part of the world, hard-won strides have been made towards equality of access, opportunity and outcome for women and girls. Though less universal, there have also been important legislative and cultural shifts to recognize LGBTQ+ people and protect them from discrimination. But a backlash is growing and spreading.

From the US to Uganda, comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) in schools, sexual and reproductive rights and LGBTQ+ rights have all come under attack.

Researchers of this phenomenon refer it as the “anti-gender movement” and warn it threatens women’s rights, gender and sexuality diversity, and democracy itself.

So, what is the anti-gender movement? Here’s what you need to know.

What is the anti-gender movement?

The anti-gender or anti-rights movement is an umbrella term that refers to social movements mobilizing opposition to what they call “gender ideology,” “gender theory” or “genderism.”

Though no singular definition exists for these terms, in practice, these movements are opposed to the same things, which the United Nations identified as the rights of LGBTQ+ people, “reproductive rights, sexuality and gender-sensitive education in schools, and the very notion of gender.”

International Womens Day 2024: 30 people defending women’s and LGTBQ+ rights around the world

The authors of a 2020 UN Human Rights report entitled “Gender Equality and Gender Backlash,” identify three specific conservative groups who are behind these movements: governments, religious groups, and civil society groups. Together, they have formed “national and transnational alliances with shared strategies and objectives.”

While their exact targets and arguments vary, proponents of anti-gender ideology generally agree that the concept of ‘gender’ is dangerous because it is changing the way our societies are structured. They view “traditional” social units – such as the male-headed nuclear family of a husband, wife, and children – as the only true or moral way to live.

An LGBTQ+ activist walks past anti-gay rights protesters holding placards, after a ruling by Kenya's High Court to uphold a law banning gay sex, in Nairobi, Kenya, on May 24, 2019. Baz Ratner/Reuters

Notably, anti-gender movements are also connected to the political shifts being witnessed around the globe, away from liberal democracy and towards right-wing populism. As Hungarian historian Andrea Pető puts it : “The anti-gender movement is not merely another offshoot of centuries-old anti-feminism but is a fundamentally new phenomenon that was launched for the sake of establishing a nationalist neoconservative response.”

The potential gains that come from playing on fears brought on by societal changes have added anti-gender rhetoric firmly to the political playbook. Donald Trump, who once celebrated the inclusion of transgender women in his beauty pageant, is now campaigning for president by vowing to “ defeat the cult of gender ideology ” and protect children from “left wing radical racists and perverts who are trying to indoctrinate our youth.”

Where in the world has anti-gender ideology gained the most traction?

The anti-gender movement is now present in almost all countries around the world, and the number of people supporting it is growing. This poses a significant challenge to not just advancing human rights protection, but also to retaining the gains already made.

Let’s take a look at some of the countries where the anti-gender movement has been most successful:

In the US, reproductive rights are being rolled back, following the Supreme Court’s reversal of Roe V. Wade in 2022, which had protected the constitutional right to abortion for decades. Risa Kaufman, Director of US Human Rights at the Center for Reproductive Rights, described this decision as a “devastating setback.”

In front of the US Supreme Court on June 24, 2022, abortion rights activists react to the Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization ruling which overturned Roe v. Wade. Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

Meanwhile, hundreds of bills targeting LGBTQ+ people – especially transgender people – have been introduced in state legislatures in recent years. At least 510 anti- LGBTQ+ bills were introduced in 2023, a new record according to data from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and nearly three-times the number were introduced in 2022. By the end of 2023, 84 bills were signed into law in 23 states.

“Anti-gender movements are connected to the political shifts witnessed around the globe, away from liberal democracy and towards right-wing populism”

In Turkey, The People’s Alliance, led by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP), won a majority in the 2023 elections following a campaign which heavily used anti-gender rhetoric. Erdoğan even said at rallies that his coalition is “against the LGBT” and “a strong family means a strong nation”; he was re-elected as president. Just two years before, the country withdrew from the Istanbul Convention , the world’s leading treaty on gender-based violence, because it threatens “family values” and “normalizes homosexuality.”

Women demonstrators in Istanbul clash with Turkish police on July 1, 2021, as they protest against Turkey's decision to withdraw from the Istanbul Convention. Yasin Akgul/AFP/Getty Images

In Ghana, a new anti-homosexuality law was passed by parliament just last month. The Human Sexual Rights and Family Values Act criminalizes LGBTQ+ relationships, as well as anyone supporting LGBTQ+ rights. UNAIDS executive director Winnie Byanyima warned that the law “will negatively impact on free speech, freedom of movement and freedom of association” and “obstruct access to life-saving services, undercut social protection, and jeopardize Ghana’s development success.” A recent CNN investigation uncovered alleged links between a US nonprofit and the drafting of the homophobic law. The group denied those links, claiming they were simply promoting “family values”.

In India, anti-gender proponents are closely linked with Hindu nationalist movements, known as Hindutva. Hindu nationalism has long relied on gender norms , encouraging women to focus on being mothers to ensure the Hindu population of India does not decrease. Traditional patriarchal social structures – where men lead and women follow – are held up as part of India’s “golden past,” to which Hindutva followers want to return.

People wearing black masks gather to raise awareness of violence against women, in Mumbai, India, on August 2, 2023. Himanshu Bhatt/NurPhoto/Getty Images

When and where did the anti-gender movement begin?

The anti-gender movement emerged in the early 1990s in response to international conferences that catalyzed recognition of gender at the United Nations and accelerated progress on gender equality, including the recognition of sexual and reproductive rights.

Historically, the concept of “the family,” which the contemporary anti-gender movement seeks to defend, can be traced back to colonial English and European ideas of the heterosexual nuclear family as the backbone of society.

In the early 2000s, the Catholic Church began sounding the gender alarm, claiming that “violent attacks on the institution of the family” were taking place. The Church perceived new laws on same-sex marriage and abortion as corroding morals. Pope John Paul II declared that “misleading concepts concerning sexuality and the dignity and mission of the woman” were driven by “specific ideologies on ‘gender.’” This led to the emergence of the term “gender ideology,” which conservative and fundamentalist groups began using to refer to the broad swathe of issues they oppose, including LGBTQ+ rights, reproductive rights, and gender equality.

Men pray and display posters of the Virgin Mary during a demonstration during a demonstration conducted mainly by men against abortion, premarital sex and women's modest clothes in Zagreb, Croatia on April 1, 2023. Denis Lovrovic/AFP/Getty Images

A decade later, anti-gender protests emerged in parts of Europe, with supporters initially mobilized by the Catholic Church. Though Pope Francis may differ from his predecessors in his view on gay people in church, on March 1, 2024, he told participants at a Vatican conference that “the ugliest danger is gender ideology” because it erases differences between men and women. “ Cancelling out the differences means cancelling out humanity,” the pontiff said.

And so, in 2024, for anti-gender actors, the term “gender” now encompasses everything from the concept of gender itself, to gender studies, legal protections for transgender people, survivors of domestic violence and rape, and women and girls in general. In fact, according to the Association of Women in Development , the concept is now being used to attack all sorts of progressive “struggles,” including even environmental issues.

How does the anti-gender movement push its agenda?

Anti-gender arguments broadly fall into three groups: nationalist (or cultural), religious, and political. The three frequently overlap. In Poland, for example, politician and former Prime Minister Jarosław Kaczyński said in 2019 that he believed the “LGBT movement and gender threaten our identity, threaten our nation [and] endanger the Polish state.”

In nationalist arguments, women and LGBTQ+ rights are often positioned as being foreign imports. In China, feminist ideas have been called “unpatriotic”, and outspoken women online are frequently attacked by nationalist trolls for their allegedly anti-China views .

Las defensoras: 30 personas que protegen los derechos de las mujeres y la comunidad LGBTQ+

Meanwhile in Kyrgyzstan, in 2021, nationalists attacked women protesting gender-based violence, with one man saying he acted because “Western values are being imposed on our young people. If they want to promote these values, let them do it in some other country.”

Religious arguments are driven by conservative and fundamentalist interpretations of religion that uphold strict ideas around gender and sexuality.

In Indonesia and Malaysia, 2023 concerts by British band Coldplay were met with opposition from Islamic groups. Even the Indonesian Ulama Council, the country’s top Islamic scholars’ body, alleged Coldplay would promote LGBTQ+ rights, and protesters gathered outside the band’s concert in Jakarta, some holding posters saying Coldplay were damaging Indonesia’s “faith and morals” . In Malaysia, organizers reportedly prepared a “kill switch” in case the band did anything to offend “local morals and sensibilities.”

Jakarta, Indonesia, November 15, 2023: Protesters demand the cancellation of a concert by British rock band Coldplay, which they say supports LGBTQ+ rights. Mas Agung Wilis/AFP/Getty Images

For right-wing and far-right politicians, the anti-gender movement offers a way to stir up what is known as a “moral panic.” A moral panic is a widespread but exaggerated fear that a group, person, or concept poses a threat to society.

For example, in Brazil, former President Jair Bolsanaro , during the course of his 2018 presidential campaign, accused his opponent of making “gay kits” for schools while education minister. He also accused teachers of “indoctrinating” children through gender and sexuality education. There was no evidence that this was in fact the case.

While the strategies used by anti-gender movements varies from place to place, one distinctive trait of this trend is just how networked the different actors are. For example, according to the UN Research Insitute for Social Development , the World Congress of Families – a US-based group which has been called “ one of the most influential American organizations involved in the export of hate” – has held events to connect “pro-family” actors in cities as diverse as Mexico City, Tblisi, Accra, Amsterdam, Madrid, and Geneva since 1997.

"US-based organizations are important funders for anti-gender movements globally”

Another US-based organization, Family Watch International , has mobilized campaigns against comprehensive sexuality education across East and Southern Africa . Family Watch International is also named in a CNN investigation as having “ hosted key politicians pushing anti-LGBTQ laws” – though the organization denies involvement in formulating legislation.

Who funds the anti-gender movement?

In addition to having clear links across countries and regions, the anti-gender movement is also funded transnationally.

A 2021 trends report, produced by the Observatory on the Universality of Rights (OURS), lists four funding sources: ultra-conservative grant-makers and private donors; religious institutions; businesses and corporations; and funding from other organizations, such as state-funded institutions.

US-based organizations are important funders for anti-gender movements globally. The Global Philanthropy Project found that at least $1billion was channelled overseas by just 11 US-based organizations to fight LGBTQ+ and women’s rights between 2008 and 2017. The authors of the report state that this amount “is surely an undercount.”

Not all sources of funding to anti-rights groups are intentionally in support of their agenda. Reporting by CNN As Equals shows that aid from donors such as the US and Germany had also flowed to religious organizations in Ghana which support the country’s new anti-LGBTQ+ bill, which was unanimously passed on February 28 .

On February 28 Ghana's parliament passed an anti-LGBTQ+ bill that criminalizes members of the LGBTQ+ community as well as its supporters. Misper Apawu/AP

What impact is the anti-gender movement having on human rights and democracy?

From Peru to Russia , women’s and LGBTQ+ organizations and activists are increasingly being criminalized, arrested, physically or sexually attacked, and even killed for their work.

1 in 4 activists from 67 countries surveyed in 2023 by The Kvinna till Kvinna Foundation – which has been monitoring the security situation for women human rights defenders for more than a decade – said they have received death threats for their work, and 58% said their own governments were behind the threats.

Women hold candles and flowers during a "Dark Valentine" vigil to demonstrate against the rising cases of femicide, in Nairobi, Kenya, on February 14. Brian Inganga/AP

Attacks on defenders create an atmosphere of fear, further restricting activism and especially discouraging ordinary citizens from standing up for their rights, while new laws actively prevent people from speaking up.

Indonesia’s new Criminal Code, ratified in 2022, sets out that only “permitted authorities” can share information on contraception and abortion with anyone under the age of 18, meaning that even social media posts about condoms or birth control pills could be restricted. Similar issues are being encountered in India, where social media content moderation policies are pushing information on sex and sexuality behind sensitivity filters .

Ultimately, anti-gender activities are contributing to “ democratic erosion .” American philosopher and gender studies scholar Judith Butler argues that “anti-gender movements are not just reactionary but fascist trends, the kind that support increasingly authoritarian go vernments.” Butler goes on: “ The opposition to ‘gender’ often merges with anti-migrant furor a nd fear, which is why it is often, in Christian contexts, merged with Islamophobia.”

High school students protest a Republican-backed bill that would prohibit classroom discussion of sexual orientation and gender identity, in Tampa, Florida, on March 3, 2022. Octavio Jones/Reuters

How is the anti-gender movement being resisted?

It’s not all bad news. As the OURs report states: “Feminist movements around the world have also been building strategies and tactics to advance our agendas. In fact, many anti-rights strategies and tactics have been inspired by us!”

And so, people around the world continue to fight back against anti-gender ideology, with organizations, activists, and ordinary citizens mobilizing to continue advancing human rights. But being a human rights defender remains a dangerous business: many face threats, violence, and criminalization on a regular basis.

CNN has profiled 30 “defenders”. Find out who they are here: in English o en Español .

Ten things to know about gender equality

In 2015, the 193 member countries of the United Nations came together to commit to 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 5 focused on gender equality and set the ambitious target of achieving gender equality and empowering women and girls everywhere by 2030. Five years later, large gender gaps remain across the world, and the early evidence suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a regressive effect on gender equality.

How can we ensure that the role of women in the workplace and in society is central to efforts to rebuild economies in the COVID-19 era, and that women do not fall further behind? As world leaders at the UN General Assembly assess progress, look ahead to recovery, and commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Fourth World Conference on Women and the Beijing declaration , we offer our perspectives on the ten things everyone should know about gender equality.

1. Tackling the global gender gap will boost global GDP

Gender inequality is not only a pressing moral and social issue but also a critical economic challenge. A 2015 report from the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), The Power of Parity: How advancing women’s equality can add $12 trillion to global growth , explored the economic potential available if the global gender gap was narrowed. Five years ago, women generated 37 percent of global GDP despite accounting for 50 percent of the global working-age population. The research found that in a best-in-region scenario in which all countries match the performance of the country in their region that has made the most progress toward gender equality, $12 trillion a year could be added to GDP in 2025. That would be equivalent in size to the GDP of Japan, Germany, and the United Kingdom combined, and roughly double the likely growth in global GDP contributed by female workers between 2014 and 2025 in a business-as-usual scenario. Both advanced and developing economies would stand to gain considerably; all regions could achieve at least 8 percent in incremental GDP over business-as-usual levels. In a full-potential scenario in which women match men’s participation in the workforce, their sector mix, and their full-time mix of jobs, the additional GDP opportunity could be $28 trillion, or an additional 26 percent of annual global GDP in 2025. That would be roughly equivalent to the GDP of the United States and China. As we note in item number 6, the COVID-19 pandemic has added new urgency—and new risks—to achieving the economic benefits of gender parity. We have updated our calculations accordingly.

2. Progress toward gender equality has been marginal since 2015; large gaps remain

Even before the COVID-19 crisis, global progress in tackling gender gaps—in both work and society—had been marginal since 2015. MGI mapped 15 indicators of gender equality in work (how men and women engage in paid work, how they share unpaid work, and their representation in high-productivity and formal jobs, and in leading positions in the economy) and society (essential services and enablers of economic opportunity like digital and financial inclusion, legal protection and political voice, and physical security and autonomy). Gender equality in society and gender equality in work are correlated based on MGI’s analysis of 125 countries. While absolute scores on equality in society tend to be higher than those of equality in work for most countries, we found virtually no countries with high equality on social indicators and low equality in employment and labor markets. This suggests that solutions need to tackle both.

We aggregated the 15 indicators into a Gender Parity Score, or GPS, ranging from zero (no gender equality) to one (full gender equality). In the past five years, progress has been marginal. Gender gaps remain across all regions (Exhibit 1). In 2015, the global GPS was 0.60; today, it is 0.61. For gender equality in work, the overall score in 2019 was 0.52, up from 0.51 in 2015. For gender equality in society, the overall score in 2019 was 0.67, up from 0.66 in 2015. These trends are similar across regions. The Middle East and North Africa region experienced the biggest increase in gender equality, rising from a global GPS of 0.47 in 2015 to 0.50 in 2019. However, some regions have experienced declines in either gender equality in work or gender equality in society since 2015.

All is not doom and gloom—there are significant bright spots to celebrate. Maternal mortality is decreasing in most places, and literacy and secondary education enrollment are increasing in many countries. At work, too, most countries are making slow and steady progress in equality. McKinsey has conducted research on gender diversity in North American companies in partnership with LeanIn.Org on since 2015. The research finds that 87 percent of North American companies today report gender diversity is a top priority , compared with 74 percent in 2015, but this reported priority still needs to translate into more decisive action. Representation of women in the C-suite in North America has increased to 21 percent, from 17 percent in 2015.

3. Over the past two decades, while women in advanced economies have made large gains as workers, consumers, and savers, they have faced rising costs and insecurity

Although women in advanced economies of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development have made far-reaching gains as workers, consumers, and savers over the past two decades, much of this progress has been offset by rising costs and new forms of insecurity that disproportionately affect women. Between 2000 and 2018, women accounted for two-thirds of 45 million jobs created in 22 OECD countries, but many of these jobs were part-time or independent work that were less secure and offered lower pay and fewer benefits. In this period, female part-time employment increased by 2.3 percentage points, versus a 0.7-percentage-point increase in full-time employment for women. As consumers, women—and men—benefited from a sharp decline in the prices of many discretionary goods and services such as communications and recreation, but that was offset by rising costs of housing, healthcare, and education that absorbed 54 to 107 percent of the average household’s income gains in Australia, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States. As savers, the outlook for women is also challenging. One study found that while women’s median net wealth is higher overall than it was two decades ago, a large gender gap remains. In Europe, women’s median net wealth is 62 percent that of men.

4. Women continue to work a double shift at home

While women face inequality in the world of work, they also face inequalities in the home. Around the world, women do three times as much unpaid care work as men. As one of many examples around the world, the “double shift” is a fact of life for millions of women in China , who go out to work but then do the lion’s share of work in the home as well. On average, they work nearly nine hours a day, and only about half of that is paid. Putting the two together, on average women in China work almost one entire day a week more than men. In some countries like India, women do almost ten times as much unpaid care work as men. This phenomenon is by no means confined to developing economies; it is a consistent fact that women work a double shift in advanced economies, too. In the United States, for instance, women still do almost twice as much unpaid care work as men; 54 percent of women but only 22 percent of men report doing all or most of the housework . Even among individuals who earn the majority of their household’s income, 43 percent of women who are primary household income earners continue to do all or most of the household work, compared with only 12 percent of men. In addition, working women are more likely than their male colleagues to have a working spouse: 81 percent of women are part of a dual-career couple and have two careers to balance, while only 56 percent of men are part of a dual-career couple.

5. Women face growing challenges from automation

Growing automation adoption adds to the challenges that women face in the workplace. MGI research found that the share of women whose jobs are replaced by machines and will likely need to make job transitions due to automation is roughly the same as for men: up to one in four over the next decade may have to shift to a different occupation. Between 40 million and 160 million women globally may need to transition between occupations by 2030, often into higher-skill roles (Exhibit 2).

The particular challenge for women is that long-standing barriers make it harder for them to adapt to the future of work. Women and men alike need to develop (1) the skills that will be in demand; (2) the flexibility and mobility needed to negotiate labor-market transitions successfully; and (3) the access to and knowledge of technology necessary to work with automated systems, including participating in its creation. Unfortunately, women often face long-established and pervasive structural and societal barriers that could hinder them in all three of these areas. Women may have less time to refresh or learn new skills or to search for employment because they spend much more time than men on unpaid care work. They may also face financial constraints in doing so. And they may not have the professional networks and sponsors that could make it easier for them to navigate job transitions, among other factors. Moreover, women tend to have less access to digital technology and lower participation in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields than men. If women make these transitions, they could find more productive, better-paid work; if they don’t, they could face a growing wage gap or leave the labor market altogether.

6. The challenge for women is now even greater as they experience economic fallout from COVID-19

Although the early evidence suggests that the COVID-19 infection has been more deadly for men than women—the death rate for men in countries like China, Italy, and South Korea has been almost double the rate for women—women’s economic prospects have been hit the hardest. On employment, our research has found that women’s jobs globally are 1.8 times as vulnerable to this crisis as men’s jobs. Women make up 39 percent of global employment but accounted for 54 percent of overall job losses as of May 2020. Globally, part of the reason is that women are disproportionately represented in industries that are expected to decline the most in 2020 due to COVID-19 (Exhibit 3). Another factor is that during the pandemic, even more unpaid care work such as childcare and home schooling fell to women as nurseries and schools closed; in the United States, for example, the amount of time women spend on household responsibilities has increased by 1.5 to two hours, according to one study . The pandemic may have had noneconomic consequences for women, too—some reports suggest that the prevalence of violence against women from an intimate partner may have increased during lockdowns . If no action is taken to counter the gender-regressive impacts of COVID-19, we calculate that global GDP growth could be $1 trillion lower in 2030 than it would be if women’s unemployment simply tracked that of men in each sector. That hit to growth could be even larger if increased childcare responsibilities, a slower recovery, and reduced public and private spending on services such as education and childcare force women to leave the labor market permanently. However, if action is taken to advance gender equality, $12 trillion could be added to global GDP in 2030 compared with the baseline, as noted earlier; this implies a $13 trillion potential compared with the gender-regressive scenario in which global GDP slides back by $1 trillion in 2030. A middle path—taking action only after the crisis has subsided rather than now—would reduce the potential opportunity by more than $5 trillion.

7. We can grow our way out of some gender equality issues but not others

Even if policy makers and companies manage to craft a robust economic recovery from the COVID-19 crisis, there is no guarantee that a resumption of economic growth will help revive progress toward gender equality. For many years, it has been clear that economic growth (rising per capita GDP) does not lift all segments of the population—we cannot grow our way out of some aspects of gender equality.

In MGI’s 2015 power of parity report, we identified ten “impact zones.” These are the largest concentrations of gender inequality, where action to tackle gender gaps would have the most impact. In five global impact zones, gender inequality is high whether women live in an advanced or emerging economy: blocked economic potential (including women’s participation in leadership positions and formal work), time spent in unpaid care work, fewer legal rights, political underrepresentation, and violence against women. Today, for every 100 men in leadership positions globally, there are just 37 women. One in three women globally, including in developed countries like the United States, has experienced violence from an intimate partner at some time in her life. In these impact zones, economic growth alone is insufficient to guarantee progress; sustained and proactive interventions will be needed.

In contrast, in some geographies, economic growth could help advance gender inequality in five regional impact zones where certain aspects of gender inequality are most prominent. They are low labor-force participation in quality jobs (in South Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa), low maternal and reproductive health (in sub-Saharan Africa), unequal education levels (in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa), financial and digital exclusion (in South Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa), and girl-child vulnerability (in China and South Asia). For many of these impact zones, economic growth can increase the provision of services that could help improve outcomes. In Africa, for instance, rising per capita GDP should enable more healthcare provision, reducing maternal mortality. As countries increase their standard of living, girls typically attain increasing levels of education. In developed countries, women are now outperforming men academically on many dimensions. In the United States, for example, women receive 57 percent of college degrees, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, and have higher overall average GPAs (but still lag behind men in STEM graduation rates).

8. Companies that are gender and ethnically diverse outperform their peers

Advancing gender equality is not just an opportunity for countries; companies also stand to gain. McKinsey research on Diversity Matters (2015), on Delivering through Diversity (2018), and most recently in May 2020 on Diversity Wins examined whether companies with higher levels of both gender and ethnic diversity have greater economic performance. The 2020 research examined a data set of more than 1,000 large companies in 15 countries and found that companies in the top quartile for gender diversity were 25 percent more likely to have above-average profitability than companies in the fourth quartile. Companies in the top quartile of ethnic and cultural diversity were 36 percent more likely to outperform on profitability. The highest-performing companies on both profitability and diversity had more women in line roles (that is, owning a line of business) than in staff roles on their executive teams. The research also found a penalty for bottom-quartile performance on gender diversity: companies in the bottom quartile for both gender and ethnic diversity were 27 percent more likely to underperform the industry average than all other firms.

Given all the competing priorities arising from the current pandemic, there is a significant risk that inclusion and diversity may recede as strategic priorities for organizations as companies focus on recovery. Downgrading diversity could well be a mistake, compromising performance and thwarting efforts to strengthen recovery over time.

9. The corporate career pipeline for women is leaky, especially early on

Over the years, our research with LeanIn.Org has found some progress in the advancement of women through the corporate pipeline in North America. In the 2019 Women in the Workplace report, we found that, of entry-level workers, 48 percent were women, compared with 45 percent in 2015. Women made up 21 percent of the C-suite, compared with 17 percent in 2019. However, as these numbers show, women are underrepresented at all levels of organizations, and the pipeline is leaky between the entry level and the C-suite. The biggest obstacle to women on the corporate ladder is a “broken rung” in the first step up to the manager level. For every 100 men hired or promoted to manager, there are only 72 women—and only 58 black women. After this initial degree of drop-off, it is very difficult for women to make up the ground lost. If differences in promotion rate are aggregated across five years, this equates to a difference of one million women in leadership roles.

Women of color are especially underrepresented in the North American workforce and face the steepest drop-offs. In North America, 18 percent of entry-level positions are held by women of color, but their representation in the C-suite is 4 percent, according to our 2019 Women in the Workplace research. These outcomes are mirrored in the day-to-day experiences of women of color in the workforce—56 percent of black women say they and their peers have equal opportunity for growth, compared with 69 percent of white women. Women of color also experience more workplace “microaggressions.” For example, 40 percent of black women and 30 percent of Asian women say they needed to provide more evidence of their competence than others, compared with 28 percent of white women and 14 percent of men.

We find similar trends across the world. Across Asia–Pacific , for instance, there is only one woman in leadership positions for every four men. In some countries in East Asia, there are only 12 to 20 women leaders for every 100 men.

10. All stakeholders need to work together to maintain and accelerate progress on gender equality

There is a huge amount to do, particularly given that the automation age and now COVID-19 mean that women face new challenges on top of old ones. The only way to breathe new life into efforts to meet Sustainable Development Goal 5 is for the main stakeholders to work together on comprehensive solutions to the complex issue of gender inequality. As governments design stimulus programs and companies look for restart strategies in the wake of the pandemic, it will be important not to ignore potential gender consequences; indeed, it’s time to double down by putting gender at the heart of these initiatives to capture opportunities. More data will be needed to ensure greater transparency and understanding of gender consequences.

National governments can enable change on a broader front using the law. For instance, they can remove legal barriers against women working (such as regulations prohibiting women from working night shifts) and can enforce laws protecting women from violence. The policy tool kit is wide-ranging, from financial support for women such as cash transfers, to tax regulations, childcare programs, and ensuring that public infrastructure is built and designed with gender in mind. The importance of reducing the gender gap in who takes responsibility for caregiving cannot be overstated, and governments can play an important role here. Some governments have enacted quotas to ensure a minimum level of women in leadership roles. Others have accelerated gender equality through incentives for women’s education, entrepreneurship, and business lending, for instance. Nongovernmental organizations also have an important role to play, for example in shaping attitudes and social norms. Many governments and NGOs have developed fruitful partnerships with companies to scale new solutions quickly. Finally, stimulus programs can be used to help invest in women and girls.

Companies can act on a number of fronts starting with their own employees, attracting, retaining, and promoting women and understanding where the pinch points in the talent pipeline are greatest. Leaders need to champion gender diversity, ensuring that hiring and promotions are fair and fostering an inclusive and respectful culture. In the COVID-19 era, many companies are exploring family-friendly policies, including flexible and part-time positions, to support workers experiencing an increased childcare burden, as well as rethinking performance reviews and promotions. Companies can use this moment to design and put in place policies and practices that can support women in the long term. Companies can also use their supply chains and procurement practices to support women-owned businesses and hold suppliers accountable to diversity and inclusion targets.

Individuals need to make a contribution, too, from advocating for themselves in their own careers to helping others advance through sponsorship and mentorship. At work, they can be proactive in supporting talented women and speaking up if they see unconscious bias or microaggressions. In their personal lives, they can explore their own biases, both conscious and unconscious. If they have families, they can aim to raise sons and daughters who are not constrained by gender. If they are investing, they can back companies that are driving gender equality in a way that is consistent with their values.

Five years after the introduction of the Sustainable Development Goals, progress on gender equality has been modest at best, and now the effort to narrow gender gaps faces new challenges in the form of automation trends and the regressive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. With only ten years left to meet Goal 5, progress needs to accelerate. Achieving equality for half the world’s population is a global imperative that risks being undermined by competing priorities in a complex world and by the challenges of recovering from the pandemic. Creating more opportunity for women and the next generation is an aspiration and a very real goal that can lift the global economy as well as contributing to a more just society. It is a goal we need to meet collectively.

The authors wish to thank MGI’s co-chair James Manyika, based in San Francisco, and MGI director Jonathan Woetzel, in Shanghai, for their ongoing contributions to gender equality research.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

COVID-19 and gender equality: Countering the regressive effects

The future of women at work: Transitions in the age of automation

Realizing gender equality’s $12 trillion economic opportunity

- New Hampshire

- North Carolina

- Pennsylvania

- West Virginia

- Online hoaxes

- Coronavirus

- Health Care

- Immigration

- Environment

- Foreign Policy

- Kamala Harris

- Donald Trump

- Mitch McConnell

- Hakeem Jeffries

- Ron DeSantis

- Tucker Carlson

- Sean Hannity

- Rachel Maddow

- PolitiFact Videos

- 2024 Elections

- Mostly True

- Mostly False

- Pants on Fire

- Biden Promise Tracker

- Trump-O-Meter

- Latest Promises

- Our Process

- Who pays for PolitiFact?

- Advertise with Us

- Suggest a Fact-check

- Corrections and Updates

- Newsletters

Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy. We need your help.

I would like to contribute

Ketaki Deo, right, and Charlie Whittington, students at George Washington University, arrive for an event supporting The Equality Act, a comprehensive nondiscrimination bill for LGBT rights, on Capitol Hill in Washington on April 1, 2019. (AP)

If Your Time is short

Some lawmakers have pushed back on an anti-LGBTQ discrimination bill by saying that there are only two genders: male and female.

Scientists, public health agencies and biologists say gender identity goes beyond male and female. The CDC says gender refers to “the cultural roles, behaviors, activities, and attributes expected of people based on their sex.”

Sex, which is different from gender, refers to “the different biological and physiological characteristics of females, males and intersex persons,” according to the WHO. There are more outcomes than simply male and female.

On one side of the Capitol Hill hallway is a pink and blue flag, a symbol for transgender pride. Directly across is a sign that says: "There are TWO genders: male & female. ‘Trust the science!’"

"Thought we’d put up our transgender flag so she can look at it every time she opens her door," tweeted Rep. Marie Newman, D-Ill., who has a transgender daughter.

"Thought we’d put up ours so she can look at it every time she opens her door," tweeted Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, R-Ga.

Their dispute is a microcosm of a larger debate over the Equality Act, a Democratic proposal to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. Newman supports the bill; Greene opposes it.

Supporters say the Equality Act provides overdue anti-discrimination protections for LGBTQ Americans who in many states can be denied housing and access to other services based on their identity. Some opponents say that the proposal infringes on the rights of faith-based organizations.

Our neighbor, @RepMarieNewman , wants to pass the so-called "Equality" Act to destroy women’s rights and religious freedoms. Thought we’d put up ours so she can look at it every time she opens her door 😉🇺🇸 https://t.co/7joKpTh6Dc pic.twitter.com/aBGRSiIF6X — Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (@RepMTG) February 24, 2021

Much of the political debate has centered on gender identity — particularly Greene’s notion that there are "two genders." However, public health agencies, doctors and biologists say science is clear: Gender identity goes beyond male and female.

"Sex is a biological term, gender is a social construct," said Ignacio T. Moore, a biological sciences professor at Virginia Tech. "In other words, gender can vary with society and culture."

The belief that there are only two genders is an oversimplification, "and what science really tells us is that it is more complicated," said Dr. Jason Rafferty, a clinical assistant professor at Brown University.

The Equality Act , which passed the House largely along party lines, would amend the 1964 Civil Rights Act by prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sex, sexual orientation and gender identity.

The Equality Act would supersede the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act , a law intended to protect religious practices from government interference. (The U.S. Supreme Court decided in 1997 that the federal law did not apply to states, prompting some states to pass their own version of the law.)

If the Equality Act became law, private businesses that are open to the public — including retail stores such as bakeries and flower shops — would not be permitted to deny service to LGBTQ people by claiming it violates their religious beliefs. The bill applies to employment, education, housing, credit, jury service, public accommodations, and programs that receive federal funding.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., said he would bring the legislation to a vote on the Senate floor, and President Joe Biden promised to sign the Equality Act.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, center, speaks about the Equality Act on Feb. 25, 2021, with Rep. Jerry Nadler, D-N.Y., and other lawmakers on Capitol Hill in Washington. (AP)

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has a list of terminology associated with sex and gender, acknowledging that terms and definitions "may change over time."

Gender refers to "the cultural roles, behaviors, activities, and attributes expected of people based on their sex," according to the CDC . Gender is not assigned at birth — it derives its meaning from the society in which one lives.

"Human nature is diverse in many ways that goes beyond simply biological and anatomical differences between people, and we are coming to understand that gender is such a characteristic that can be both complicated and personal," Rafferty said. "A person’s gender identity may be masculine, feminine, a combination of both or neither, or it may shift over time."

Cisgender is the term used to describe someone whose gender aligns with the sex they were assigned at birth, such as biological males who identify as men. There are numerous other ways for people to describe their gender identity, including nonbinary (individuals who identify as neither a man nor a woman) and transgender (individuals whose gender differs from the sex they were assigned at birth).

A February Gallup poll found that 5.6% of U.S. adults identify as LGBTQ, and 0.6% identify specifically as transgender. Gallup noted that those numbers could underestimate the actual population, as older adults may be less likely to self-identify as LGBTQ.

Sexual orientation is often conflated with gender identity and sex, said Karen Parker, director of the Sexual & Gender Minority Research Office at the National Institutes of Health. But all three categories are distinct, and sexual orientation primarily "relates to identity attraction and behavior," she said.

The World Health Organization says sex refers to "the different biological and physiological characteristics of females, males and intersex persons, such as chromosomes, hormones and reproductive organs."

One might think that sex is a trait with only two biological possibilities. But medical research and firsthand accounts indicate that strictly male and female sex characteristics are not the only outcomes.

The biological sex of humans is partially determined by the configuration of chromosomes, the long strands of DNA that contain the genetic information of an organism. If you’re born with two X chromosomes, your biological sex will most likely be female. Biological males typically have one X and one Y chromosome.

In this June 6, 2019, photo, Victory, an intersex girl, points to her baby photo, as her brother Richard and her mother Amie Schofield look on, at their home in Ogden, Utah. (AP)

Sometimes, there’s a discrepancy between someone’s sex assigned at birth and their biological, physiological or physical characteristics. Intersex is a term that’s used to describe any variation in sex characteristics, which can sometimes be related to chromosomes and hormones.

Moore offered some examples that could result in someone being intersex:

People with Y chromosomes that lack a specific gene can develop and identify as females.

People with testes that do not descend into the scrotum can develop and identify as females.

People with testosterone levels typical of a biological male but who lack the receptor for the hormone can develop and identify as female.

"With these factors in mind," Moore said. "I think it becomes clear that an individual’s sex is not necessarily binary, as factors can conflict."

Estimates for the proportion of babies who are born intersex range from 0.018% to 1.7%, depending on how intersex is defined.

Nature provides variations in sex and humans decide how to categorize them, said Alice Dreger, a bioethicist who has researched differences of sex development. "Nature doesn’t tell us who counts as male, who counts as female and who counts as intersex — we draw those lines," she said.

A misunderstanding of gender identity and sex deserves clarification, experts said, because LGBTQ Americans — particularly youth — face more adverse health outcomes than other Americans.

"The big thing to remember is that it’s not just politics," Rafferty said. "These are people’s lives."

RELATED: Rachel Levine does not support gender confirmation surgery for all children

Our Sources

Alice Dreger, " Hermaphrodites and the Medical Invention of Sex "

American Journal of Human Biology, " How sexually dimorphic are we? Review and synthesis ," Feb. 11, 2000

Anne Fausto-Sterling, " Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality "

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Adolescent and School Health: Terminology

Congress.gov, H.R.1308 - Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993

Congress.gov, H.R.5 - Equality Act

Cureus, " Health Care Disparities Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth: A Literature Review ," April 2017

Email interview with Dr. Jason Rafferty, clinical assistant professor at Brown University, March 2, 2021

Gallup, " LGBT Identification Rises to 5.6% in Latest U.S. Estimate ," Feb. 24, 2021

Healthline, " 64 Terms That Describe Gender Identity and Expression "

Human Rights Campaign, 2020 State Equality Index

Intersex Human Rights Australia, " Intersex population figures ," Sept. 28, 2013

Interview with Alice Dreger, bioethicist and differences of sex development researcher, March 2, 2021

Interview with David Sloan Wilson, an evolutionary biologist and emeritus professor at Binghamton University, March 1, 2021

Interview with Karen Parker, director of the Sexual & Gender Minority Research Office at the National Institutes of Health, March 2, 2021

Email interview, Ignacio T. Moore, a biological sciences professor at Virginia Tech, March 2, 2021

The Journal of Sex Research, " How common is lntersex? A response to Anne Fausto‐Sterling ," Feb. 5, 2002

Letter from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Feb. 23, 2021

Mayo Clinic, Congenital adrenal hyperplasia

Mayo Clinic, Klinefelter syndrome

Mayo Clinic, Turner syndrome

MedlinePlus, Intersex

National Human Genome Research Institute, " The Y chromosome: beyond gender determination "

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, " What are the symptoms of congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH)? "

PolitiFact, Biden Promise Tracker: Enact the Equality Act

Quartz, " An intersex shark discovered near Taiwan shines a light on fluidity in the animal kingdom ," Dec. 27, 2017

Rev, Pelosi, Schumer Press Conference on House Equality Act Transcript February 25

Teen Vogue, " 9 Young People on How They Found Out They Are Intersex ," Oct. 25, 2019

Tweet from Rep. Marie Newman, Feb. 24, 2021

Tweet from Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, Feb. 24, 2021

United Nations Free & Equal, FACT SHEET: Intersex

U.S. House of Representatives Clerk, Roll Call 39 | Bill Number: H. R. 5

World Health Organization, Gender and Genetics

World Health Organization, Gender and health

Read About Our Process

The Principles of the Truth-O-Meter

Browse the Truth-O-Meter

More by daniel funke.

What the Equality Act debate gets wrong about gender, sex

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Dispelling the myths: why the gender pay gap does not reflect the 'choices' women make

The Diversity Council’s report shows women are paid less just because they are women. So why are we still debating the existence of the pay gap?

A ccording to the World Economic Forum , there is no country on earth where women make as much as men for the same work. In their 2016 Global Gender Gap Report, it is estimated that, at current rates, it would take another 170 years to close the global pay gap between men and women .

The pay data for Australia certainly isn’t bucking this trend. It doesn’t matter which way you look at it, there is consensus that the gender pay gap exists . Even though the overall gap in Australia has reduced slightly over the past two years, according to data from the ABS women still make 16.2% less than men .

Yet, somehow, talking about the pay gap can still be controversial .

Too often in my job, I am called on to counter arguments about the gender pay gap being a “myth”, or that “the gender pay gap figure isn’t real; it’s a manipulated, oversimplified figure that doesn’t represent real situations”.

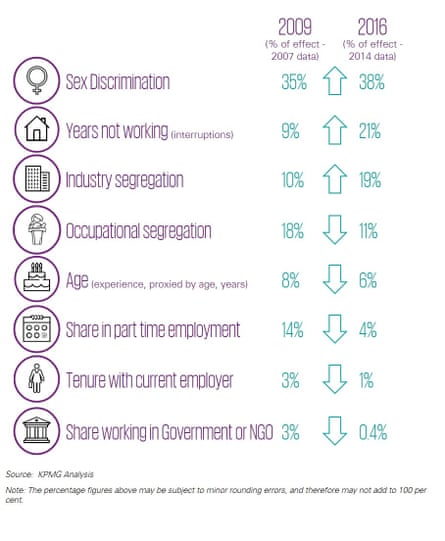

Earlier this month the organisation I lead, Diversity Council Australia, released an important report together with KPMG and the Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA). Called She’s Price(d)less – the economics of the gender pay gap , it presents a picture of the economics underlying the gender pay gap.

We asked KPMG to decompose the factors that make up the pay gap so that we could understand exactly why it persists and what we can do about it .

The resulting report counters the myths and provides the evidence that refutes a whole range of other “reasons” put forward about women earning less because they “choose” to work part-time or take time out of the workforce to care for family members.

And my hope is that, with this evidence in hand, we can have a rational conversation based on data, sound research and with the facts in mind.

So here goes.

Women are paid less because they ‘choose’ to work part-time

Our report showed that there has been a significant decrease in the impact of part-time employment on the gender pay gap. It has actually declined from 14% to 4%, in part because of an increase in higher-paid part-time roles for women. This is good news as it means that much of the hard work that has been done on improving flexible work options is starting to pay off.

The idea of “choice” becomes questionable, however, when one considers that overwhelmingly it is still women who take on the bulk of unpaid caring roles within families. There are a number of reasons for this (historical and social norms playing a significant part) but, given that men are paid more than women, for many families it just does not make financial sense for men to work part-time as it will result in a bigger cut to the family budget.

Women are paid less because they ‘choose’ lower-paying jobs

Our report showed that industrial and occupational segregation continue to be significant contributing factors to the gender pay gap. But while occupational segregation is decreasing (i.e. the different types of roles men and women do), the impact of industrial segregation (i.e. the different industries that men and women work in like mining or healthcare) has increased.

Women are not “choosing” to work in lower paying industries but, when large numbers of women start to work in an industry, they all get paid less. As Rhaina Cohen explained in an article in the Atlantic:

A study [by the sociologists Asaf Levanon, Paula England, and Paul Allison], which examined census data from 1950 to 2000, found that, when women enter an occupation in large numbers, that job begins to pay less, even after controlling for a range of factors like skill, race and geography. Their analysis found evidence of “devaluation” – that a higher proportion of women in an occupation leads to lower pay because of the discounting of work performed by women.

So, in other words: 50 years of data proved that the more women join an industry the less everyone gets paid.

If that’s not convincing enough, Cohen also pointed to a study showing that higher the percentage of women in an industry the lower its perceived “prestige”; and a study from 2007 that found that even where men’s low-wage jobs demand far less in terms of skill, education and certifications than women’s low-wage jobs, the male-dominated ones usually command higher hourly pay.

Women don’t have the same levels of education as men

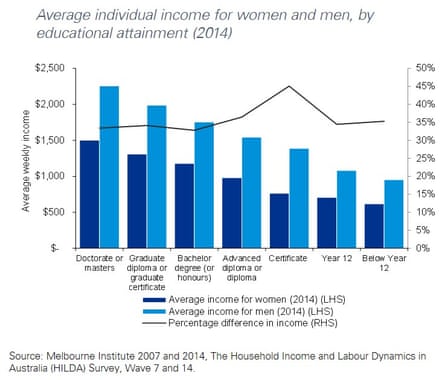

Despite women reaching higher levels of educational attainment, there has not been an associated decrease in the pay gap between women and men. This graph from the KPMG report makes it clear:

The pay gap figure is bogus because it does not reflect ‘like-for-like’ pay gaps for employees in the same or comparable roles

It must be said that while it is illegal to pay women less than men doing the same jobs, it is still happening. WGEA’s annual report shows that, even in their first year in the workforce, male graduates earn more than female graduates entering the same roles. Recent estimates from Australia suggest that for partners in top firms, the like-for-like gap is up to 5%.

Women don’t negotiate for better pay so it’s their fault if they’re paid less

Again, it’s not true to say women don’t ask for raises. They just don’t receive them at the same rate as men. And there is evidence that when women do negotiate, they are actually penalised.

A recent study from Cass Business School, the University of Warwick and the University of Wisconsin shows that women ask for wage rises just as often as men but men are 25% more likely to get a raise when they ask. The study collected data from 4,600 Australian workers across more than 800 employers and found no difference in the likelihood of asking between the two genders. The authors suggested that it might actually be “how” women ask, that a lack of assertiveness in negotiations is often cited as a potential reason why women might make less money than men for similar work.

As WGEA explains, negotiation is usually associated with agentic, and therefore masculine, behaviour. When employers negotiate with women, they tend to offer less and are more likely to resist influence attempts. Studies have shown that women’s reluctance to enter negotiations is partly because they are penalised more than men for doing so. The more women anticipate backlash, the less inclined they are to initiate negotiations.

In other words, women are asking for raises but, if they ask too assertively, they’re turned down for being too pushy, and if they don’t ask assertively enough, they aren’t good negotiators so they don’t get a raise.

The pay gap reflects choices women make, not discrimination

First of all, there’s that questionable word, “choice”, again.

Secondly, what our study showed was that sex discrimination continues to be the single largest factor contributing to the gender pay gap, increasing from 35% in 2007 to 38% in 2014.

Sex discrimination in the report accounts for everything that is left after all the other factors that have an impact on the gender pay gap, such as age, tenure, time out of the workforce, occupation, industry, part-time work and sector, have been taken into account. This means that more than a third of the gender pay gap is the result of gender discrimination and unconscious bias.

In other words, women are paid less than men simply because they are women.

So if the new report She’s Price(d)less reveals anything above and beyond what we already know about pay inequity in the Australian economy, it is that we now know exactly what constitutes the gap.

Not only should this be enough to silence the sceptics but it should shine a light for individuals and their organisations – and indeed the wider community – on where to start fixing the problem.

- Guardian sustainable business

- Social equality

- Work & careers

- Women in the boardroom

- sponsored features

Most viewed

- EU Politics

- Foreign Affairs

- LSE Comment

Johanna Kantola

Emanuela lombardo, march 1st, 2021, how opposition to gender equality is expressed by radical right meps in the european parliament.

0 comments | 43 shares

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Issues affecting gender equality are frequently debated in the European Parliament. Drawing on a recent study, Johanna Kantola and Emanuela Lombardo present new findings on how radical right MEPs express opposition to gender equality during plenary sessions.

The European Parliament is a unique transnational representative and democratic institution. It also has a reputation for being the most pro-gender equality actor among the EU’s decision-making institutions. The proportion of women MEPs in the parliament has steadily increased and is currently at 40 percent. The Parliament hosts parliamentary bodies, such as the Committee for Women’s Rights and Gender Equality (FEMM), which are tasked with ensuring a gender perspective is included in all policymaking. Despite a downturn in EU gender equality policies in the 2010s, the Parliament has generally been supportive of gender equality.

Yet, this picture has become fractured in recent years. Polarisation in the Parliament has increased with the influx of radical right populists. Gender is an important factor in this polarisation. One recent analysis indicates that after the 2019 European Parliament elections, the number of MEPs that oppose gender equality and women’s rights had risen to over 30 percent (around 210 out of 705 MEPs) – essentially doubling in comparison to the previous legislature.

A plenary session on 21 January this year provided an example of the variety of strategies and alliances which some radical right populists employ in the European Parliament to oppose gender equality. The Parliament was debating – as it often does – several topics related to gender equality, including the European Commission’s Gender Equality Strategy; a FEMM Committee report on the gender impact of the Covid-19 pandemic; and gender and the digital economy. Many of the speeches would have caught the ear of a feminist listener.

Several radical right populist MEPs from the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and Identity and Democracy (ID) groups used the occasion to ridicule gender equality. One argued that debates on “gender and common sense” should be held, while another suggested that playing cards might soon be in the firing line “because the King is worth more than the Queen”. Statements like these are designed to delegitimise the progressive politics of the Parliament and trivialise the issue of gender equality, which is a fundamental right and core value of EU democracy. Examples such as these serve to illustrate the need to understand how opposition to gender equality is expressed in the European Parliament.

Direct and indirect strategies

In a new study , we analyse the strategies used by radical right populists in the 2014-19 European Parliament to oppose gender quality. The aim of these strategies varies: from mobilising sympathisers and demobilising opponents; to defining the boundaries of ‘elites’ and ‘the people’ in populist politics; and shaping the borders of what is possible in terms of gender equality politics and policies. Such discourses are important not only in relation to their impact on policies, but because of the effect they have on the parameters of debates.

One of our key findings is that opposition to gender equality in the EU now includes direct opposition, not only indirect forms of opposition, which was the case in the past. Direct opposition comes, first, in the form of outright rejection of gender equality, and, second, with reference to what some radical right populists have termed ‘gender ideology’ – a term that is intended to portray gender knowledge as indoctrination. Homophobic, misogynistic, and xenophobic arguments are all direct forms of opposition to gender equality.

Credit: CC-BY-4.0: © European Union 2020 – Source: EP

In the European Parliament’s plenary sessions, this approach serves to oppose gender equality and create a hostile environment for advancing it. The key populist elements of this opposition to ‘gender ideology’ include constructing an image of corrupt international elites interfering in national politics and imposing political correctness. The EU itself is often portrayed as a harmful proponent of ‘gender ideology’. Radical right populist MEPs have articulated these discourses while arguing that gender equality has been constructed in a harmful way that challenges natural categories of women, men, sexuality and family.

Indirect opposition comes in many forms. It may be based on Euroscepticism , where MEPs hide their opposition to gender equality behind criticism of the EU’s approach to the issue. Another indirect strategy is bending gender equality to other goals. For example, instead of focusing on the problems that refugee women face – the purpose of one debate – some radical right populist MEPs have reframed the issue by arguing that European migration policies put ‘native women and children’ at risk. Islamophobic language is frequently used to construct an ‘other’ that is hostile to gender equality, with the EU accused of failing to protect ‘its’ women from this threat.

Other indirect opposition strategies include the use of s elf-victimisation , whereby radical right populists complain that their free speech has been inhibited by gender-sensitive language. In one debate on sexual harassment in the EU, some MEPs adopted a self-victimisation approach to shift blame onto the European Parliament for allegedly excluding a radical right populist group from the accompanying resolution. Parliamentary opponents were accused of double standards, resulting in an exchange that shifted the focus away from gender equality.

The impact of opposition to gender equality

The effect of these direct and indirect strategies is to make gender equality and feminist politics more contentious, increasing the levels of polarisation that surround debates on gender. They also reopen and question policies that have already been ‘accepted’, such as equal employment opportunities, gender quotas, LGBT rights and policies targeting gender violence.

While radical right populist MEPs can effectively monopolise debates during plenary sessions, they do not have a significant impact on votes about gender equality and they generally do limited work in committees. Their direct opposition to gender equality is nevertheless detrimental to the construction of equality and democracy in the European Parliament. This is because it shapes, in a restrictive manner, the meaning of gender equality and the nature of political agendas and commitments surrounding gender issues.

Yet, if gender equality becomes an increasingly politicised issue, with debates channelled through respectful confrontation, this may not in itself be a negative development. Direct opposition could result in making the arguments for and against gender equality more explicit and tangible. Once made explicit, direct opposition could be debated and countered by active supporters of gender equality.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the International Political Science Review

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: CC-BY-4.0: © European Union 2020 – Source: EP

About the author

Johanna Kantola is Professor of Gender Studies at Tampere University, Finland. She directs the European Research Council (ERC) Consolidator Grant project EUGenDem, which studies the European Parliament’s political groups, gender and democracy. She has published extensively on gender and politics including the books Gender and Political Analysis (with Emanuela Lombardo), Gender and the European Union, and the co-edited volumes Gender and the Economic Crisis in Europe (with Emanuela Lombardo) and The Oxford Handbook on Gender and Politics.