Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Immigration to America — How Immigration Changed America

How Immigration Changed America

- Categories: Immigration to America

About this sample

Words: 605 |

Published: Sep 12, 2023

Words: 605 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

The early waves of immigration, the melting pot and cultural fusion, economic growth and innovation, demographic changes and diversity, social and political changes.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 636 words

2 pages / 1093 words

1 pages / 669 words

2 pages / 1006 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Immigration to America

The question of what makes someone an American is a complex and multifaceted issue that has been debated and discussed for centuries. The United States of America is a diverse and dynamic country, comprised of individuals from [...]

Immigration has long been a contentious issue, with passionate debates on both sides. From economic impacts to cultural integration, the topic of immigration is multifaceted and complex. In this argumentative essay, we will [...]

Moving to America can be a life-changing experience filled with excitement, challenges, and opportunities. The decision to uproot oneself and start afresh in a new country is not one to be taken lightly, as it involves adjusting [...]

Have you ever wondered about the stories that lie within your own family history? The tales of triumph, tragedy, love, and loss that have shaped the lives of your ancestors and ultimately led to your own existence? Family [...]

Immigrants have moved to America for hundreds of years to find a better lifestyle and more opportunities for economic growth. America was known as the “Land of the Free, with open land, and freedom for all. Immigrants have [...]

The migration of immigrants and immigration is a topic that has sparked heated debates and discussions across the world. With the growing number of people leaving their home countries in search of better opportunities, as well [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Sorry, we did not find any matching results.

We frequently add data and we're interested in what would be useful to people. If you have a specific recommendation, you can reach us at [email protected] .

We are in the process of adding data at the state and local level. Sign up on our mailing list here to be the first to know when it is available.

Search tips:

• Check your spelling

• Try other search terms

• Use fewer words

Why do immigrants come to the US?

Of all people legally immigrating to the US in 2021, about 42% came for work, 32% for school, and 23% for family.

Updated on Fri, November 17, 2023 by the USAFacts Team

People immigrate to the US to work, reunite with family, study, or seek personal safety. In 2021, 42% of the 1.5 million people who immigrated to the US came for work.

What reasons for immigration does the government track?

The US government generally allows legal immigration for five broad reasons : work , school , family, safety, and encouraging diversity.

People immigrating for work or school are often granted temporary entry rather than permanent residency. Immigration for family generally means the immigrant has a relative who is already in the US as a citizen, green card holder, or temporary visa holder with whom they want to be reunited with. Those who immigrate for safety are refugees or asylum-seekers. And finally, up to 50,000 immigrants obtain green cards annually through the Diversity Immigrant Visa Program lottery that grants entry to individuals from countries with low rates of immigration to the US.

How many immigrants came for each reason in 2021?

Of the 1.5 million people who immigrated to the US in 2021, about 42% came for work, 32% for school, and 23% for family. Nearly 2% were seeking safety, and about 0.9% were admitted on Diversity Immigrant Visas.

How have reasons for immigration evolved over the past 15 years?

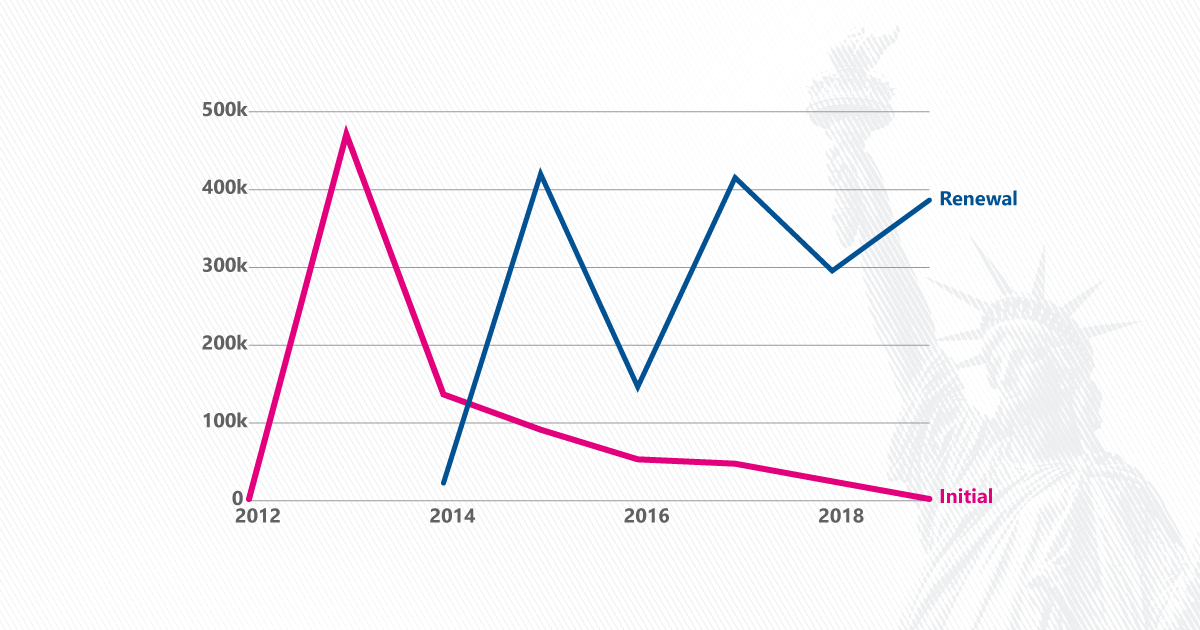

Since 2006, work has consistently been the top reason people immigrate to the US, with the exception of 2013–2015 when immigration for work was equal to or slightly lower than for school.

School is usually the second most common reason for immigration except for 2018, when a higher percentage of people began immigrating for family reunification than education. In 2021 school again became the second most common reason.

Safety and diversity have consistently been the fourth and fifth most common reasons for immigration, respectively.

How do the reasons for immigration change depending on where people are immigrating from?

Of the 638,551 immigrants who came to the US for work in 2021, 61% came from North America. Immigrants from Asia represent the largest geographic cohort among the other four primary reasons for immigration: school (58%), family (45%), safety (34%), and encouraging diversity (33%).

In 2021, 74% of all immigrants came from Asia and North/Central America. Roughly 53% of Asian immigrants came from China and India, while nearly 80% of immigrants from North/Central America were from Mexico.

Get facts first

Unbiased, data-driven insights in your inbox each week

You are signed up for the facts!

Why do Chinese people immigrate to America?

School was the top reason Chinese people immigrated between 2006–2021; 19% of people who came to the US for school were from China, the highest percentage of any other country. The number of Chinese immigrants coming to the US for school peaked in 2015, growing 680% from 40,477 people in 2006 to 315,628 people in 2015.

Despite a sharp decrease after 2016, most Chinese immigrants continue to come to the US for school. Fewer than 57,000 Chinese immigrants have come to the US per year for work or family reasons since 2006, and those numbers hit record lows of 5,323 and 13,412 in 2021.

Why do Indian people immigrate to America?

The largest share of immigrants who came to be with family were from India, at 18% . But in 2021, more Indians immigrated for school than for family reunification. Work was the third most common reason.

Prior to 2021, most Indian immigrants came to the US for family and work, but those numbers have been decreasing. Fewer people came to the US from India for work (54,032 people) and family in 2021 (62,407) than in 2006 (117,189 and 81,045 people, respectively).

Meanwhile, the number of Indians immigrating for school increased by over 300% between 2020 and 2021, from 20,629 to 85,385.

Why do Mexican people immigrate to America?

In 2021, people from Mexico comprised the largest share of immigrants coming for work — 55% of all immigrants, or 351,586 people. Work has consistently been the top reason Mexican people immigrate to the US. Family and school have consistently been the second and third reasons.

More than double the number of people immigrated to the US for work from Mexico in 2021 (351,586 people) than in 2006 (168,619 people).

Where did this data come from?

There are multiple data sources because immigrants enter the US through multiple pathways. Data on visa admissions comes from the US State Department; we exclude people who come with visas for short-term tourism, cultural exchange, or visiting. Data on refugees and asylum-seekers comes from the Department of Homeland Security's (DHS) Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Data on green cards comes from the DHS’s expanded lawful permanent resident tables.

Read more about where immigrants are moving in the US , and get the data directly in your inbox by signing up for our email newsletter .

Explore more of USAFacts

Related articles.

Population and society

Asylum in the United States: How the case backlog grew to hundreds of thousands

How many DACA recipients are there in the United States?

Immigration demographics: A look at the native and foreign-born populations

The Census has been asking about citizenship on and off for nearly 200 years

Related Data

Immigrant population

46.18 million

Visas granted

6.82 million

Unauthorized immigrant population

11.39 million

Data delivered to your inbox

Keep up with the latest data and most popular content.

SIGN UP FOR THE NEWSLETTER

The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

Understanding the U.S. Immigrant Experience: The 2023 KFF/LA Times Survey of Immigrants

Shannon Schumacher , Liz Hamel , Samantha Artiga , Drishti Pillai , Ashley Kirzinger , Audrey Kearney , Marley Presiado , Ana Gonzalez-Barrera , and Mollyann Brodie Published: Sep 17, 2023

- Methodology

Executive Summary

The Survey of Immigrants, conducted by KFF in partnership with the Los Angeles Times during Spring 2023, examines the diversity of the U.S. immigrant experience. It is the largest and most representative survey of immigrants living in the U.S. to date. With its sample size of 3,358 immigrant adults, the survey provides a deep understanding of immigrant experiences, reflecting their varied countries of origin and histories, citizenship and immigration statuses, racial and ethnic identities, and social and economic circumstances. KFF also conducted focus groups with immigrants from an array of backgrounds, which expand upon information from the survey (see Methodology for more details).

This report provides an overview of immigrants’ reasons for coming to the U.S.; their successes and challenges; their experiences at work, in their communities, in health care settings, and at home; as well as their outlook on the future. Recognizing the diversity within the immigrant population, the report examines variations in the experiences of different groups of immigrants, including by immigration status, income, race and ethnicity, English proficiency, and other factors. Given that this report includes a focus on experiences with discrimination and unfair treatment, data by race and ethnicity are often shown rather than by country of birth. A companion report provides information on immigrants’ health coverage, access to, and use of care, and further reports will provide additional details for other subgroups within the immigrant population, including more data by country of origin.

Key takeaways from this report include:

- Most immigrants – regardless of where they came from or how long they’ve been in the U.S. – say they came to the U.S. for more opportunities for themselves and their children. The predominant reasons immigrants say they came to the U.S. are for better work and educational opportunities, a better future for their children, and more rights and freedoms. Smaller but still sizeable shares cite other factors such as joining family members or escaping unsafe or violent conditions.

- Overall, a majority of immigrants say their financial situation (78%), educational opportunities (79%), employment situation (75%), and safety (65%) are better as a result of moving to the U.S. A large majority (77%) say their own standard of living is better than that of their parents, higher than the share of U.S.-born adults who say the same (51%) 1 ,and most (60%) believe their children’s standard of living will be better than theirs is now. Three in four immigrants say they would choose to come to the U.S. again if given the chance, and six in ten say they plan to stay in the U.S. However, about one in five (19%) say they want to move back to the country they were born in or to another country, while an additional one in five (21%) say they are not sure.

- Despite an improved situation relative to their countries of birth, many immigrants report facing serious challenges, including high levels of workplace and other discrimination, difficulties making ends meet, and confusion and fears related to U.S. immigration laws and policies. These challenges are more pronounced among some groups of immigrants, including those who live in lower-income households, Black and Hispanic immigrants, those who are likely undocumented, and those with limited English proficiency. Given the intersectional nature of these factors, some immigrants face compounding challenges across them.

- Most immigrants are employed, and about half of all working immigrants say they have experienced discrimination in the workplace, such as being given less pay or fewer opportunities for advancement than people born in the U.S., not being paid for all their hours worked, or being threatened or harassed . In addition, about a quarter of all immigrants, rising to three in ten of those with college degrees, say they are overqualified for their jobs, a potential indication that they had to take a step back in their careers when coming to the U.S. or lacked career advancement opportunities in the U.S.

- About a third (34%) of immigrants say they have been criticized or insulted for speaking a language other than English since moving to the U.S., and a similar share (33%) say they have been told they should “go back to where you came from.” About four in ten (38%) immigrants say they have ever received worse treatment than people born in the U.S. in a store or restaurant, in interactions with the police, or when buying or renting a home. Some immigrants also report being treated unfairly in health care settings. Among immigrants who have received health care in the U.S., one in four say they have been treated differently or unfairly by a doctor or other health care provider because of their racial or ethnic background, their accent or how well they speak English, or their insurance status or ability to pay for care.

- Immigrants who are Black or Hispanic report disproportionate levels of discrimination at work, in their communities, and in health care settings. Over half of employed Black (56%) and Hispanic (55%) immigrants say they have faced discrimination at work, and roughly half of college-educated Black (53%) and Hispanic (46%) immigrant workers say they are overqualified for their jobs. Nearly four in ten (38%) Black immigrants say they have been treated unfairly by the police and more than four in ten (45%) say they have been told to “go back to where you came from.” In addition, nearly four in ten (38%) Black immigrants say they have been treated differently or unfairly by a health care provider. Among Hispanic immigrants, four in ten (42%) say they have been criticized or insulted for speaking a language other than English.

- Even with high levels of employment, one third of immigrants report problems affording basic needs like food, housing, and health care. This share rises to four in ten among parents and about half of immigrants living in lower income households (those with annual incomes under $40,000). In addition, one in four lower income immigrants say they have difficulty paying their bills each month, while an additional 47% say they are “just able to pay their bills each month.”

- Among likely undocumented immigrants, seven in ten say they worry they or a family member may be detained or deported, and four in ten say they have avoided things such as talking to the police, applying for a job, or traveling because they didn’t want to draw attention to their or a family member’s immigration status . However, these concerns are not limited to those who are likely undocumented. Among all immigrants regardless of their own immigration status, nearly half (45%) say they don’t have enough information to understand how U.S. immigration laws affect them and their families, and one in four (26%) say they worry they or a family member could be detained or deported. Confusion and lack of information extend to public charge rules. About three quarters of all immigrants, rising to nine in ten among likely undocumented immigrants, say they are not sure whether use of public assistance for food, housing, or health care can affect an immigrant’s ability to get a green card or incorrectly believe that use of this assistance will negatively affect the ability to get a green card.

- About half of all immigrants have limited English proficiency, and about half among this group say they have faced language barriers in a variety of settings and interactions. About half (53%) of immigrants with limited English proficiency say that difficulty speaking or understanding English has ever made it hard for them to do at least one of the following: get health care services (31%); receive services in stores or restaurants (30%); get or keep a job (29%); apply for government financial help with food, housing, or health coverage (25%); report a crime or get help from the police (22%). In addition, one-quarter of parents with limited English proficiency say they have had difficulty communicating with their children’s school (24%). Working immigrants with limited English proficiency also are more likely to report workplace discrimination compared to those who speak English very well (55% vs. 41%).

Who Are U.S. Immigrants?

The KFF/LA Times Survey of Immigrants is a probability-based survey that is representative of the adult immigrant population in the U.S. based on known demographic data from federal surveys (see Methodology for more information on sampling and weighting). For the purposes of this project, immigrant adults are defined as individuals ages 18 and over who live in the U.S. but were born outside the U.S. or its territories.

According to 2021 federal data, immigrants make up 16% of the U.S. adult population (ages 18+). About four in ten immigrant adults identify as Hispanic (44%), over a quarter are Asian (27%), and smaller shares are White (17%), Black (8%), or report multiple races (3%). The top six countries of origin among adult immigrants in the U.S. are Mexico (24%), India (6%), China (5%), the Philippines (5%), El Salvador (3%), and Vietnam (3%) although immigrants hail from countries across the world.

The immigrant adult population largely mirrors the U.S.-born adult population in terms of gender. While similar shares of U.S.-born and immigrant adults have a college degree, immigrant adults are substantially more likely than U.S.-born adults to have less than a high school education. About four in ten (40%) immigrants are parents of a child under 18 living in their household, and a quarter (25%) of children in the U.S. have an immigrant parent.

Slightly less than half (47%) of immigrant adults report having limited English proficiency, meaning they speak English less than very well. Regardless of ability to speak English, a large majority (83%) of immigrants say they speak a language other than English at home, including about four in ten (43%) who speak Spanish at home.

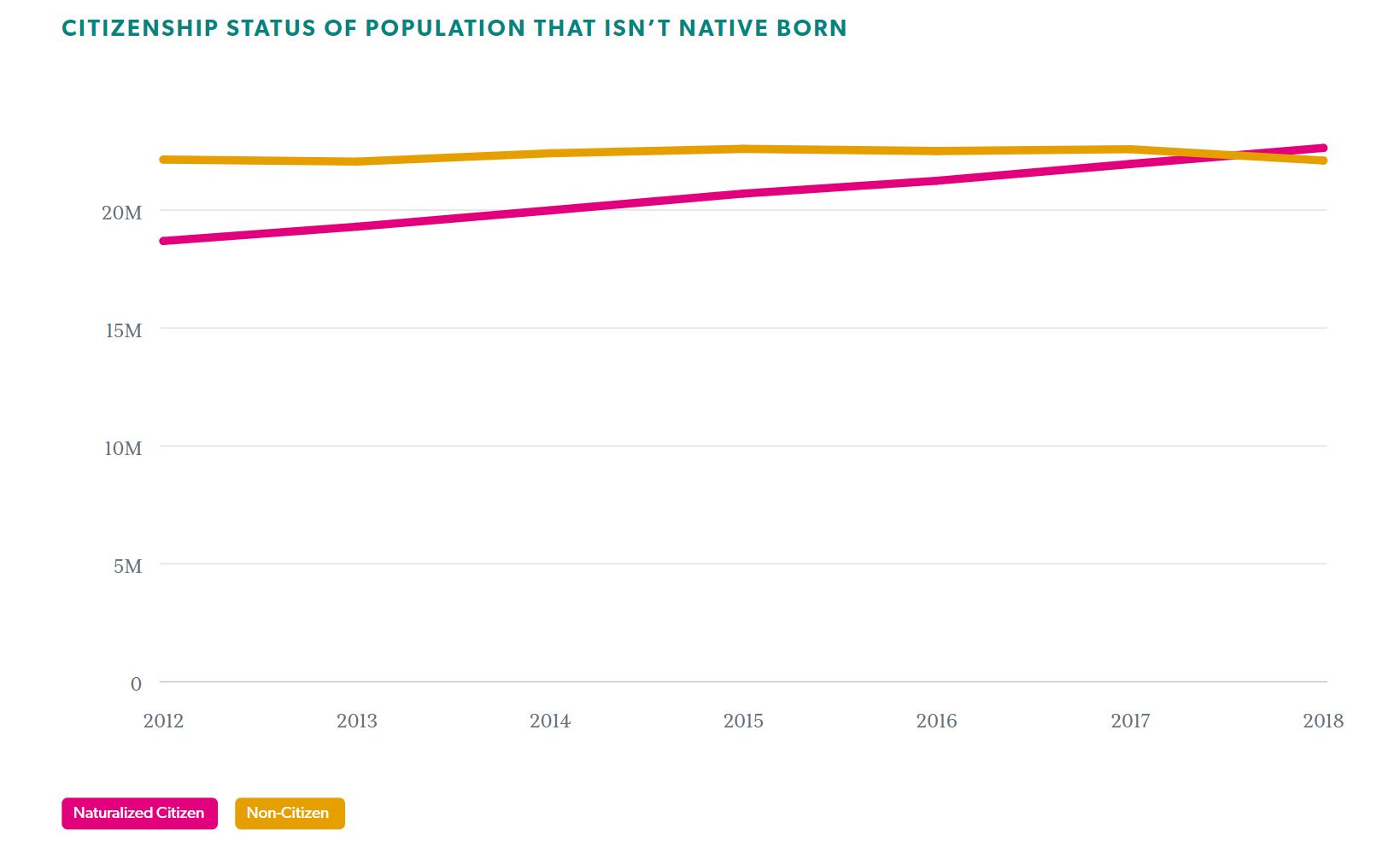

A majority (55%) of U.S. adult immigrants are naturalized citizens. The remaining share are noncitizens, including lawfully present and undocumented immigrants. KFF analysis based on federal data estimates that 60% of noncitizens are lawfully present and 40% are undocumented. 2

See Appendix Table 1 for a table of key demographics about the U.S. adult immigrant population compared to the U.S.-born adult population.

Key Terms Used In This Report

Limited English Proficiency : Immigrants are classified as having Limited English Proficiency if they self-identify as speaking English less than “very well.”

Immigration Status: Immigrants are classified by their self-reported immigration status as follows:

- Naturalized Citizen : Immigrants who said they are a U.S. citizen.

- Green Card or Valid Visa : Immigrants who said they are not a U.S. citizen, but currently have a green card (lawful permanent status) or a valid work or student visa.

- Likely Undocumented Immigrant : Immigrants who said they are not a U.S. citizen and do not currently have a green card (lawful permanent status) or a valid work or student visa. These immigrants are classified as “likely undocumented” since they have not affirmatively identified themselves as undocumented.

Race and Ethnicity: Data are reported for four racial and ethnic categories: Hispanic, Black, Asian, and White based on respondents’ self-reported racial and ethnic identity. Persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race but are categorized as Hispanic for this analysis; other groups are non-Hispanic. Results for individuals in other groups are included in the total but not shown separately due to sample size restrictions. Given that this report includes a focus on experiences with discrimination and unfair treatment, we often show data by race and ethnicity rather than country of birth. Given variation of experiences within these broad racial and ethnic categories, further reports will provide additional details for subgroups within racial and ethnic groups, including more data by country of origin.

Educational Attainment: These data are based on the highest level of education completed in the U.S. and/or in other countries as self-reported by the respondent. The response categories offered were: did not graduate high school, high school graduate with a diploma, some college (including an associate degree), university degree (bachelor’s degree), and post-graduate degree (such as Master’s, PhD, MD, JD).

Country of Birth : “Country of birth” is classified based on respondents’ answer to the question “In what country were you born?” In some cases, countries are grouped into larger regions. See Appendix Table 2 for a list of regional groupings.

Why Do Immigrants Come to The U.S. And How Do They Feel About Their Life in the U.S.?

Immigrants cite both push and pull factors as reasons for coming to the U.S. For most immigrants, their major reasons for coming to the U.S. are aspirational, such as seeking better economic and job opportunities (75% say this is a major reason they came to the U.S.), a better future for their children (68%), and for better educational opportunities (62%). Half of immigrants say a major reason they or their family came to the U.S. was to have more rights and freedoms, including about three-quarters of immigrants from Central America (73%). Smaller but sizeable shares say other factors such as joining family members (42%) or escaping unsafe or violent conditions (31%) were major reasons they came. The share who cites escaping unsafe conditions as a major reason for coming to the U.S. rises to about half of likely undocumented immigrants (51%) and about six in ten (59%) immigrants from Central America.

In Their Own Words: Reasons for Coming to the U.S. from Focus Group Participants

Stories focus group participants told of why they came to the U.S. reflect the survey responses. While many pointed to economic and educational opportunities, some described leaving harsh economic and unsafe conditions in their home countries.

“I came to the U.S. hoping that my children will have better educational opportunity.” – 58-year-old Vietnamese immigrant woman in California

“[My husband] came here, and I followed him. So, he came, and I came with the kids afterwards…so we could have a better life. It’s not easy…we wanted to have…better opportunities for our children, for ourselves.” – 46-year-old Ghanian immigrant woman in New Jersey

“The thing is that there are more opportunities, and the standard of living is much better. We can make ends meet even through manual labor. That is not possible in Vietnam.” – 33-year-old Vietnamese immigrant man in Texas

“Then, my mom had to make a decision because the gangs took control of her place. They started asking for rent, extorting her life. If she didn’t pay the extortion, the rent, they were going to take me, or my siblings, or her. …since I was the oldest, she brought me, making the sacrifice of leaving behind my two siblings.” – 25-year-old Salvadorian immigrant man in California

“Actually, it wasn’t my decision to come. I left when I was 13 years old, fleeing from my country because I had a death threat, along with my eight-year-old sister. I didn’t want to come.” – 20-year-old Honduran immigrant woman in California

“Because of the earthquake, you know, I lost my house, and I wanted to go to a country with more opportunities and I came here.” – 30-year-old Haitian immigrant man in Florida

Most immigrants say moving to the U.S. has provided them more opportunities and improved their quality of life. When the survey asked immigrants to describe in their own words the best thing that has come from moving to the U.S., many similar themes arise: better opportunities, a better life in general, or a better future for their children are top mentions, as are education and work opportunities.

In Their Own Words: The Best Thing That Has Come From Moving To The U.S.

In a few words, what is the best thing that has come from you moving to the U.S.?

“Educational opportunities, economic opportunities, political and human rights, housing, food and basic needs, neighborhood safety, lower crime rates”- 28 year old Mexican immigrant woman in Nebraska

“Best education for my kids. Professional job. Healthy environment. Good system. The opportunities everywhere!” – 67-year-old Nepalese immigrant man in Maryland

“Better job, education, and economic opportunities” – 48-year-old Indian immigrant woman in North Carolina

“Education and improved quality of life in terms of obtaining basic needs” – 39-year-old Dominican immigrant woman in New Jersey

“Stability, freedom, better finance[s], having the opportunity to have a family” – 32-year-old Venezuelan immigrant man in New York

“Educational and employment opportunities for myself and my children” – 60-year-old Filipino immigrant woman in California

Most immigrants feel that moving to the U.S. has made them better off in terms of educational opportunities (79%), their financial situation (78%), their employment situation (75%), and their safety (65%). Safety stands out as an area where somewhat fewer –though still a majority–immigrants say they’re better off, particularly among White and Asian immigrants. A bare majority (54%) of Asian immigrants and fewer than half (42%) of White immigrants say their safety is better as a result of moving to the U.S., while about one in five in both groups (17% of Asian immigrants and 21% of White immigrants) say they are less safe as a result of coming to the U.S.

In Their Own Words: Safety Concerns In The U.S. From Focus Group Participants

In focus groups, some participants pointed to concerns about guns, drugs, and safety in the U.S., particularly in their children’s schools.

“Sometimes when you see on the television and they’re talking about shooting and these types of things. In Ghana we don’t have that—it’s safe, you walk around, you’re free.” – 38-year-old Ghanian immigrant woman in New Jersey

“I take my kids to school because, really, you have to go to school. But if I could have them at home and homeschool them, I’d do it. I wouldn’t let them go because I don’t feel safe anymore.” – 51-year-old Salvadorian immigrant man in California

“I’m from Mexico, and over there, you have to struggle to get a gun. Here, you can buy a gun like you’re buying candy at Walmart or somewhere.” – 37-year-old Mexican immigrant man in Texas

“Because in my children’s school, there are a lot of drugs found in its restrooms. …There is so much temptation for drugs here. It is not that safe.” – 49-year-old Vietnamese immigrant woman in Texas

Most immigrants say they are better off compared with their parents at their age, and most are optimistic about their children’s future. When asked about their standard of living, three quarters (77%) of immigrants say their standard of living is better than their parents’ was at their age. This is substantially higher than the share of U.S.-born adults who say the same (51%). Many expect an even better future for their children. Six in ten immigrants believe their children’s standard of living will be better than theirs is now, with much smaller shares saying they think it will be worse (13%) or about the same (17%). Most immigrant parents also have positive feelings about the education their children are receiving . About three in four (73%) immigrant parents rate their child’s school as either “excellent” (35%) or “good” (38%), with a further one-sixth (17%) saying the school is “fair,” and 3% give it a “poor” rating.

In Their Own Words: Hopes For Their Children’s Future From Focus Group Participants

In focus groups, many participants described hopes and dreams for their children’s futures, which often center on improved educational and job opportunities. Some pointed to sacrifices they were making in their own lives for the future benefit of the children.

“I am old, so I came here for my children. That is the thing– We must pay dearly for it when we first came here, but since then, we have seen that life here is wonderful.” – 59-year-old Vietnamese immigrant man in California

“I want my daughter to achieve what I couldn’t…I want her to be better, so she doesn’t have to go through what I went through” – 32-year-old Mexican immigrant woman in California

“…I will not change anything for my kids or for myself. I think it didn’t work out like I expected to do, but I don’t regret it because my kids have the better chance to have a better education system.” – 42-year-old Ghanian immigrant woman in California

“These children, they were born there; they have the opportunity; they get the opportunity, they go to school for free; they get food when they get food; they don’t have these problems. I can say yes, their lives are better than before the life I had.” – 48-year-old Haitian immigrant woman in Florida

How Are Immigrants Faring Economically?

Like many U.S. adults overall, immigrants’ biggest concerns relate to making ends meet: the economy, paying bills, and other financial concerns. When asked in the survey to name the biggest concern facing them and their families in their own words, about one-third of immigrants gave answers related to financial stability or other economic concerns. No other concern rose to the level of financial concerns, though other common concerns mentioned include health and medical issues, safety, work and employment issues, and immigration status.

In Their Own Words: Biggest Concerns Facing Immigrant Families Are Economic

In a few words, what is the biggest concern facing you and your family right now?

“Low income, hard to survive as day to day cost of living is going up” – 65 year old Colombian immigrant man in Texas

“There are a lot of expenses. Groceries and gas prices are at a high price. It gets overwhelming with all the bills and trying to save money in this economy right now.” – 50-year-old Pakistani immigrant man in California

“High prices for rents and new homes” – 55-year-old Congolese immigrant man in Florida

“Retirement– will I need to keep working until I die?” – 64-year-old Dutch immigrant man in Colorado

“Biggest concern is with the inflation. It’s hard to keep up with buying groceries, gas paying the bills paying the mortgage and trying to live paycheck to paycheck worrying about if you’re gonna be able to afford paying the next bill.” – 35-year-old Mexican immigrant man in Nevada

“The house payment. The interest. Everything is really expensive. The food and the university for my son.” – 51-year-old Mexican immigrant woman in California

One in three immigrants report difficulty paying for basic needs. About one in three immigrants (34%) say their household has fallen behind in paying for at least one of the following necessities in the past 12 months: utilities or other bills (22%), health care (20%), food (17%), or housing (17%). The share who reports problems paying for these necessities rises to about half among immigrants who have annual household incomes of less than $40,000 (47%). The shares who report facing these financial challenges are also larger among immigrants who are likely undocumented (51%), Black (50%), or Hispanic (43%), largely because they are more likely to be low income. Additionally, four in ten immigrant parents report problems paying for basic needs.

Beyond having trouble affording basic needs, a sizeable share of immigrants report they are just able to or have difficulties paying monthly bills. Nearly half (47%) of immigrants overall say they can pay their monthly bills and have money left over each month, while four in ten (37%) say they are just able to pay their bills and about one in six (15%) say they have difficulty paying their bills each month. Affordability of monthly bills varies widely by income as well as race and ethnicity. For example, only about a quarter (27%) of lower income immigrants say they have money left over after paying monthly bills compared with eight in ten (80%) of those with at least $90,000 in annual income. About six in ten immigrants who are White or Asian say they have money left over after paying their bills each month compared with four in ten Hispanic immigrants and one-third (32%) of Black immigrants, reflecting lower incomes among these groups.

Despite these financial struggles, close to half of immigrants say they send money to relatives or friends in their country of birth at least occasionally . Overall, about one in three (35%) immigrants say they send money occasionally or when they are able. Much smaller shares report sending either small (8%) or large (2%) shares of money on a regular basis, and overall, most immigrants (55%) do not send money to relatives or family outside the U.S.

Similar shares of immigrants report sending money to their birth country regardless of their own financial struggles. About half (49%) of those who have difficulty paying their bills each month say they send money at least occasionally, as do 44% of those who say they just pay their bills and the same share of those who have money left over after paying monthly bills. Two-thirds (65%) of Black immigrants say they send money to their birth country at least occasionally, while about half (52%) of Hispanic immigrants and four in ten Asian immigrants (42%) report sending money. A much smaller share (24%) of White immigrants say they send money to the country where they were born.

What Are Immigrants’ Experiences In The Workplace?

Two-thirds of immigrants say they are currently employed, including nearly seven in ten of those under age 30, about three quarters of those between the ages of 30-64, and a quarter of those ages 65 and over. The remaining third include a mix of students, retirees, homemakers, and few (6%) unemployed immigrants. A quarter of working immigrants say they are self-employed or the owner of a business, rising to one-third (34%) of White working immigrants and nearly three in ten (27%) Hispanic working immigrants. Jobs in construction, sales, health care, and production are the most commonly reported jobs among working immigrants. KFF analysis of federal data shows that immigrants are more likely to be employed in construction, agricultural, and service jobs than are U.S.-born citizen workers.

About a quarter of working immigrants feel they are overqualified for their job, rising to half of college-educated Black and Hispanic immigrants. A majority of working immigrants overall (68%) say they have the appropriate level of education and skills for their job, while about a quarter (27%) say they are overqualified, having more education and skills than the job requires. Just 4% say they are underqualified, having less education and skills than their job requires. In an indication that some immigrants are unable to obtain the same types of roles they were educated and trained for in the countries they came from, the share who feel overqualified for their current job rises to 31% among immigrants with college degrees. It is even higher among college-educated Black (53%) and Hispanic (46%) immigrants.

In Their Own Words: Work Experiences From Focus Group Participants

In focus groups, many immigrants expressed a desire to work and willingness to work in industries like construction, agriculture, and the service sector, which are often physically demanding. Some also described taking jobs that required less skills and education compared to those they held in their country of birth.

“We are the ones that work on the farms. We are the ones that cannot call out. We are the ones that even if our kids are sick, we can’t call our boss and say I can’t make it to work.” – 38-year-old Nigerian immigrant woman in New Jersey

“Yes, we have to put our effort in. It is more demanding. My hands and feet are sore. In exchange, I have a satisfactory level of income.” – 49-year-old Vietnamese immigrant woman in Texas

“…in Mexico, I was a preschool teacher. Being undocumented, obviously, you can’t work in the area you studied in, so now, I do cleaning.” – 36-year-old Mexican immigrant woman in Texas

“I used to work a white-collar job, now I do manual labor. My major used to hurt my mind, now it’s my arms and legs.” – 41-year-old Vietnamese immigrant woman in Texas

“My job entails picking up trash and cleaning toilets. I don’t like doing that. Who likes cleaning toilets? Who likes picking up other people’s trash, right? I don’t like it, but I’m in this job out of necessity.” – 20-year-old Honduran immigrant woman in California

“I only had [one] job back in Vietnam. Here I need to do four: a nanny, a maid, a house cleaner and a main job.” – 41-year-old Vietnamese immigrant woman in Texas

“The work in the field is hard. When it’s hot out, it gets up to 100 or 104. People work with grapes, so they pick the grapes. They work in the sun. There’s no air…. Snakes come out. Whatever comes out, you just keep picking with the machine. Snakes, mice, whatever. So, it’s hard. It’s hard.” – 32-year-old Mexican immigrant woman in California

Overall, about half of employed immigrants report working jobs that pay them by the hour (52%), one third say they are paid by salary (32%), and 15% report being paid by the job. However, these shares vary by income, immigration status, educational attainment, and race and ethnicity. Compared to immigrants with higher incomes, immigrants with lower incomes are more likely to be paid by the hour (63% of immigrants with annual household incomes of less than $40,000) or by the job (24%) than receive a salary (13%). Immigrants who are likely undocumented (30%) are about twice as likely as those with a green card or visa (14%) or naturalized citizens (12%) to report being paid by the job, and about half as likely to report being paid by salary (17%, 32%, and 36%, respectively). Immigrants with a college degree are more than three times as likely as those without a college degree to hold salaried jobs, (57% vs. 16%). Black and Hispanic immigrants are more likely to report working hourly jobs (69% and 60% respectively) than their White (42%) and Asian (40%) counterparts. Conversely, among those who are employed, almost half of Asian immigrants and more than four in ten White immigrants report being paid by salary compared with a quarter or fewer Black and Hispanic immigrants.

About half of working immigrants report experiencing discrimination at work. About half (47%) of all working immigrants say they have ever been treated differently or unfairly at work in at least one of five ways asked about on the survey, most commonly being given fewer opportunities for advancement (32%) and being paid less (29%) compared to people born in the U.S. About one in five working immigrants say they have not been paid for all their hours or overtime (22%) or have been given undesirable shifts or less control over their work hours than someone born in the U.S. doing the same job (17%). About one in ten (12%) say they have been harassed or threatened by someone in their workplace because they are an immigrant.

Highlighting the intersectional impacts of race, ethnicity, and immigration status, reports of workplace discrimination are higher among immigrant workers of color and likely undocumented immigrants. Majorities of Black (56%) and Hispanic (55%) immigrant workers report experiencing at least one form of workplace discrimination asked about. More than four in ten (44%) Asian immigrant workers also report experiencing workplace discrimination compared to three in ten (31%) White immigrant workers. About two-thirds (68%) of likely undocumented working immigrants report experiencing at least one form of unfair treatment in the workplace, with about half of this group saying they have been paid less or had fewer opportunities for advancement than people born in the U.S. for doing the same job. Undocumented immigrant workers often face even greater employment challenges due to lack of work authorization, which increases risk of potential workplace abuses, violations of wage and hour laws, and poor working as well as living conditions.

Limited English proficiency is also associated with higher levels of reported workplace discrimination. A majority (55%) of working immigrants who speak English less than very well (rising to 61% of Hispanic immigrants with limited English proficiency) report experiencing at least one form of workplace discrimination. In particular, immigrants with limited English proficiency are more likely than those who are English proficient to say they were given fewer opportunities for promotions or raises (38% vs. 27%) or were paid less than people born in the U.S. for doing the same job (34% vs. 24%).

Do Immigrants Feel Welcome In The U.S.?

Most immigrants feel welcome in their neighborhoods. Overall, two-thirds of immigrants say most people in their neighborhoods are welcoming to immigrants. Just 7% say people in their neighborhood are not welcoming, while one in four say they are “not sure” whether immigrants are welcome in their neighborhood. When it comes to the treatment of immigrants in the state in which they live, about six in ten immigrants say they feel people in their state are welcoming to immigrants, but 15% say their state is not welcoming and another one in four say they are “not sure.” When asked about whether they think most people are welcoming to immigrants outside of the state in which they live, about half (48%) of immigrants say they are “not sure” about this, which could reflect lack of experiences in other places.

Immigrants in Texas are much less likely than those in California to feel their state is welcoming to immigrants. Immigrants living in California and Texas, the two most populous states for immigrants, are about equally likely to say immigrants are welcome in their neighborhood. However, immigrants living in California are about 30 percentage points more likely than are immigrants living in Texas to say they feel people in their state are welcoming to immigrants (70% vs. 39%). Further, immigrants in Texas are more than three times as likely as those in California to say they feel their state is not welcoming to immigrants (31% vs. 8%).

What Are Immigrants’ Experiences With Discrimination And Unfair Treatment In The Community?

Despite feeling welcome in their neighborhoods, many immigrants report experiencing discrimination and unfair treatment in social and police interactions . About four in ten (38%) immigrants say they have ever received worse treatment than people born in the U.S. in at least one of the following places: in a store or restaurant (27%), in interactions with the police (21%), or when buying or renting a home (17%). In addition, about a third (34%) of immigrants say that since moving to the U.S., they have been criticized or insulted for speaking a language other than English, and a similar share (33%) say they have been told they should “go back to where you came from.”

Reports of discrimination and unfair treatment are more prevalent among people of color compared to White immigrants, illustrating the combined impacts of racism and anti-immigrant discrimination. For example, about one-third of immigrants who are Black (35%) or Hispanic (31%) and about a quarter (27%) of Asian immigrants say they have ever received worse treatment than people born in the U.S. in a store or restaurant, all higher than the share among White immigrants (16%). Notably, four in ten (38%) Black immigrants say they have ever received worse treatment than people born in the U.S. in interactions with the police, and almost half (45%) say they have been told they should “go back to where you came from.” Among Hispanic immigrants, about four in ten (42%) say they have been criticized or insulted for speaking a language other than English.

In Their Own Words: Experiences With Discrimination In The Community From Focus Group Participants

In focus groups, many immigrants shared their experiences with discrimination in the community.

“Sometimes, when you talk, the way some people will laugh. They’ll laugh at you, you say one word, they’ll be laughing, laughing, laughing. …I’m so very ashamed. I’m so ashamed, so you don’t want to talk.” – 46-year-old Ghanian immigrant woman in New Jersey

“I speak English, but obviously, I don’t speak it fluently. I have my accent, and you can tell that I’m Mexican. I’ve seen people make faces at me or whatnot.” – 37-year-old Mexican immigrant man in Texas

“We have our business around the corner. I left the house one day to go pick up my daughter, and my husband called me. There was a White guy yelling at my husband ‘Get out of my country.’ I said, ‘Tell him that it’s your country, too.’” – 36-year-old Mexican immigrant woman in California

“The guy was like…you guys should go back to your country. He used different words for us. Then he called the cops, and when the cops came, they didn’t listen to us. I was like, this is unfair. You could have listened to both sides.” – 38-year-old Nigerian immigrant woman in New Jersey

“But my son when he first came here, he did not know English. When he went to school, his classmates said, ‘You do not study well, you should go back to your country.’” – 54-year-old Vietnamese immigrant woman in California

One in four immigrants report being treated unfairly by a health care provider. In addition to discrimination at work and in community settings, a sizeable share of immigrants say they have been treated unfairly by a doctor or health care provider since coming to the U.S. Overall, among immigrants who have received health care in the U.S., one in four (rising to nearly four in ten Black immigrants) say they have been treated differently or unfairly by a doctor or other health care provider because of their racial or ethnic background, their accent or how well they speak English, or their insurance status or ability to pay for care. For more details about immigrants’ health and health care experiences, read the companion report here.

What Language Barriers Do Immigrants With Limited English Proficiency Face?

Over half of immigrants with limited English proficiency report language barriers in a variety of settings and interactions. Overall, about half of all immigrants have limited English proficiency, meaning they speak English less than very well. Among this group, about half (53%) say that difficulty speaking or understanding English has ever made it hard for them to do at least one of the following: receive services in stores or restaurants (30%); get health care services (31%); get or keep a job (29%); apply for government assistance with food, housing, or health coverage (25%); or get help from the police (22%).

Language barriers are amplified among those with lower levels of educational attainment as well as those with lower incomes. Among immigrants with limited English proficiency, those who do not have a college degree are more likely to report experiencing at least one of these difficulties than those who have a college degree (57% vs. 39%). Similarly, lower income immigrants (household incomes less than $40,000) with limited English proficiency are more likely to report facing language barriers compared to their counterparts with incomes of $90,000 or more (61% vs. 38%).

Immigrant parents with limited English proficiency also face challenges communicating with their children’s school or teacher. Among immigrant parents with limited English proficiency (52% of all immigrant parents), about one in four (24%) say difficulty speaking or understanding English has made it hard for them to communicate with their child’s school or teacher.

How Do Confusion And Worries About Immigration Laws And Status Affect Immigrants’ Daily Lives?

About seven in ten (69%) immigrants who are likely undocumented worry they or a family member may be detained or deported. However, worries about detention or deportation are not limited to those who are likely undocumented. About one in three immigrants who have a green card or other valid visa say they worry about this, as do about one in ten (12%) immigrants who are naturalized U.S. citizens.

Some immigrants report avoiding certain activities due to concerns about immigration status. Fourteen percent of immigrants overall, rising to 42% of those who are likely undocumented, say they have avoided things such as talking to the police, applying for a job, or traveling because they didn’t want to draw attention to their or a family member’s immigration status. In addition, 8% of all immigrants say they have avoided applying for a government program that helps pay for food, housing, or health care because of concerns about immigration status, including 27% of those who are likely undocumented.

More than four in ten (45%) immigrants overall say they don’t have enough information about U.S. immigration policy to understand how it affects them and their family. Lack of immigration-related knowledge is strongly related to one’s immigration status. Nearly seven in ten (69%) immigrants who are likely undocumented say they don’t have enough information, while immigrants with a valid green card or visa are split, with one half saying they have enough information and the other half saying they do not. Being a naturalized U.S. citizen doesn’t completely diminish immigrants’ confusion about U.S. immigration policy, as nearly four in ten (39%) immigrants who are naturalized citizens also say they don’t have enough information. Beyond immigration status, the groups who are more likely to say they do not have enough information to understand how immigration policy affects them and their families include immigrants with limited English proficiency, those who have been in the U.S. for fewer than five years, have lower household incomes, and/or have lower levels of education.

Across immigrants, there is a general lack of knowledge about public charge rules. Under longstanding U.S. policy, federal officials can deny an individual entry to the U.S. or adjustment to lawful permanent status (a green card) if they determine the individual is a “ public charge ” based on their likelihood of becoming primarily dependent on the government for subsistence. In 2019, the Trump Administration made changes to public charge policy that newly considered the use of previously excluded noncash assistance programs for health care, food, and housing in public charge determinations. This policy was rescinded by the Biden Administration in 2021, meaning that the use of noncash benefits, including assistance for health care, food, and housing, is not considered for public charge tests, except for long-term institutionalization at government expense. The survey suggests that many immigrants remain confused about public charge rules. Six in ten immigrants say they are “not sure” whether use of public programs that help pay for health care, housing or food can decrease one’s chances for green card approval and another 16% incorrectly believe this to be the case. Among immigrants who are likely undocumented, nine in ten are either unsure (68%) or incorrectly believe use of these types of public programs will decrease their chances for green card approval (22%).

What Are Immigrants Plans And Hopes For The Future?

Six in ten immigrants say they plan to stay in the U.S. However, about one in five immigrants say they want to move back to the country they were born in (12%) or to another country (7%), and about one in five (21%) say they are not sure. The desire to stay in the U.S. varies by immigration status as well as by race and ethnicity. Nearly two in three immigrants who are naturalized citizens say they plan to stay in the country, compared to about half of immigrants who have a green card or valid visa (54%) or immigrants who are likely undocumented (52%). Black immigrants are somewhat more likely than immigrants from other racial or ethnic backgrounds to say they plan to leave the U.S. (28%). This includes 17% who say they want to move back to their country of birth and 11% who say they want to move to a different country.

Three in four immigrants say they would choose to come to the U.S. again. Asked what they would do if given the chance to go back in time knowing what they know now, three in four immigrants (75%) say they would choose to come to the U.S. again, including large shares across ages, educational attainment, income, immigration status, and race and ethnicity. While most immigrants share this sentiment, overall, about one in ten (8%) immigrants say they would not choose to move to the U.S. and about one in five (17%) say they are not sure whether they would choose to move to the U.S.

In Their Own Words: Focus Group Participants Say They Would Choose To Come To The U.S. Again

In focus groups, many participants said that despite the challenges they face in the U.S., life is better here than in their country of birth. When asked whether they would choose to come again, many said yes and pointed to how they have more opportunities for themselves and their children to have a better standard of living.

“So I will not change anything for my kids or for myself. I think it didn’t work out like I expected to do but I don’t regret it because my kids have the better chance to have a better education system”-42-year-old Ghanian immigrant woman in California

“I can say from my experience, it was really hard. God made everything right now because I have my papers. But I agreed to stay here for my children, so that they have a better life tomorrow. Because home is worse.” – 48-year-old Haitian immigrant woman in Florida

“Of course, I would still come to America. When I compare my current state with that of my old neighbors, who are my age as well, this place is a far cry from it.” – 40-year-old Vietnamese immigrant man in Texas

“We’re happy because we have a better life, even though we always miss our homeland. But it’s better.” – 35-year-old Mexican immigrant man in California

“I can say that America gives me many options, many opportunities, so far I like it. The only thing I don’t like is how the bills are here, they come fast when you make a small amount of money many times it goes through the bill.” – 30-year-old Haitian immigrant man in Florida

Immigrants represent a significant and growing share of the U.S. population, contributing to their communities and to the nation’s culture and economy. Immigrants come to the U.S. largely seeking better opportunities and lives for themselves and their children, often leaving impoverished and sometimes dangerous conditions in their country of birth. For many, this dream has been realized despite ongoing challenges they face in the U.S.

Many immigrants recognize work as a key element to achieving their goals and are willing to fill physically demanding, lower paid jobs, for which some feel they are overqualified. Immigrants are disproportionately employed in agricultural, construction, and service jobs that are often essential for our nation’s infrastructure and operations.

Despite high rates of employment and, for many, an improved situation relative to their county of birth, many immigrants face serious challenges in the U.S. Finances are a top challenge and concern, with many having difficulty making ends meet and paying for basic needs. Moreover, although most immigrants feel welcome in their neighborhood, many face discrimination and unfair treatment on the job, in their communities, and while seeking health care. Fears of detention and deportation are a concern for immigrants across immigration statuses, sometimes affecting daily lives and interactions, particularly among those who are likely undocumented.

Some immigrants face more challenges than others, reflecting the diversity of the immigrant experience and the compounding impacts of intersectional factors such as immigration status, race and ethnicity, and income. Black and Hispanic immigrants, likely undocumented immigrants, immigrants with limited English proficiency, and lower income immigrants face disproportionate challenges given the impacts of racism, fears and uncertainties related to immigration status, language barriers, and financial challenges. Many immigrants lack sufficient information to understand how U.S. immigration laws and policies impact them and their families. This confusion and lack of certainty contributes to some immigrants avoiding accessing assistance programs that could ease financial challenges and facilitate access to health care for themselves and their children, who are often U.S.-born.

As the immigrant population in the U.S. continues to grow, recognizing their contributions and challenges of immigrants and addressing their diverse needs will be important for improving the nation’s overall health and economic prosperity.

- Racial Equity and Health Policy

- Race/Ethnicity

- Quality of Life

- TOPLINE & METHODOLOGY

- U.S.-BORN ADULT COMPARISON

Also of Interest

- Understanding the Diversity in the Asian Immigrant Experience in the U.S.: The 2023 KFF/LA Times Survey of Immigrants

- Health and Health Care Experiences of Immigrants: The 2023 KFF/LA Times Survey of Immigrants

- Political Preferences and Views on U.S. Immigration Policy Among Immigrants in the U.S.: A Snapshot from the 2023 KFF/LA Times Survey of Immigrants

Read our research on: Gun Policy | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Key findings about u.s. immigrants.

View interactive charts and detailed tables on U.S. immigrants.

Note: For our most recent estimates of unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. click here .

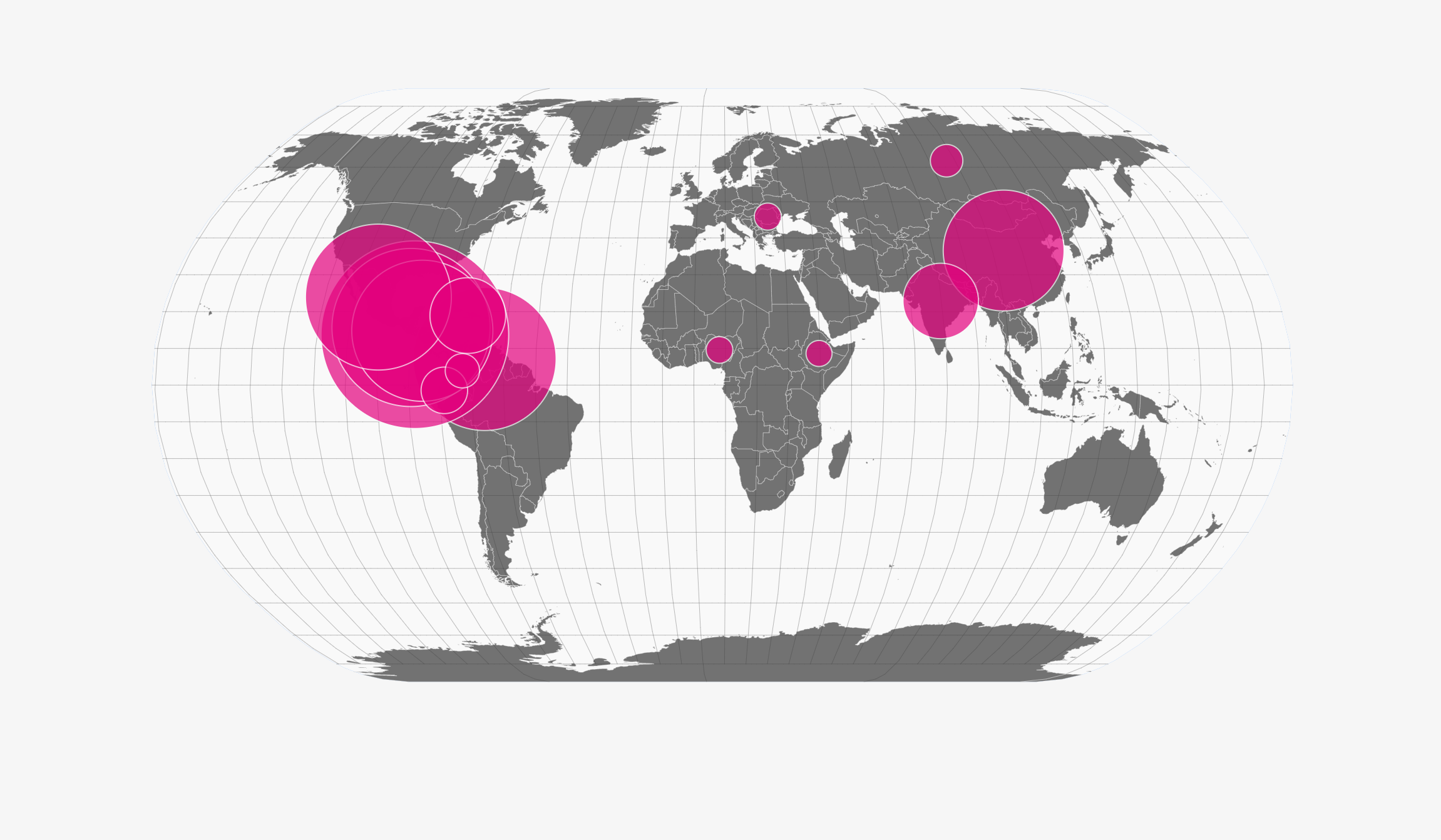

The United States has more immigrants than any other country in the world . Today, more than 40 million people living in the U.S. were born in another country, accounting for about one-fifth of the world’s migrants. The population of immigrants is also very diverse, with just about every country in the world represented among U.S. immigrants.

Pew Research Center regularly publishes statistical portraits of the nation’s foreign-born population, which include historical trends since 1960 . Based on these portraits, here are answers to some key questions about the U.S. immigrant population.

How many people in the U.S. are immigrants?

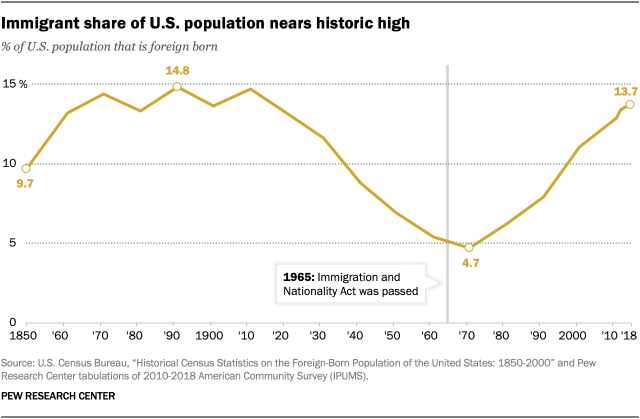

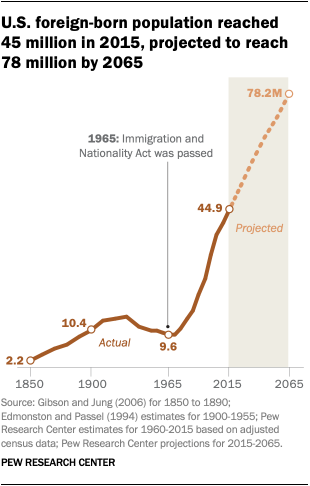

The U.S. foreign-born population reached a record 44.8 million in 2018. Since 1965, when U.S. immigration laws replaced a national quota system , the number of immigrants living in the U.S. has more than quadrupled. Immigrants today account for 13.7% of the U.S. population, nearly triple the share (4.8%) in 1970. However, today’s immigrant share remains below the record 14.8% share in 1890, when 9.2 million immigrants lived in the U.S.

What is the legal status of immigrants in the U.S.?

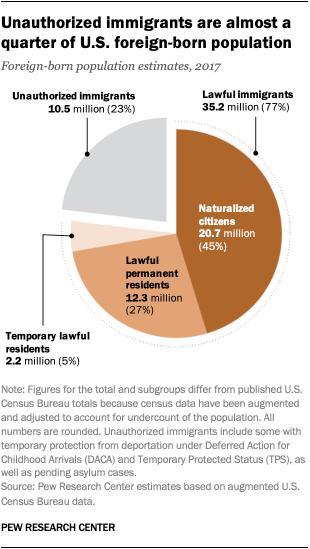

Most immigrants (77%) are in the country legally, while almost a quarter are unauthorized, according to new Pew Research Center estimates based on census data adjusted for undercount . In 2017, 45% were naturalized U.S. citizens.

Some 27% of immigrants were permanent residents and 5% were temporary residents in 2017. Another 23% of all immigrants were unauthorized immigrants. From 1990 to 2007, the unauthorized immigrant population more than tripled in size – from 3.5 million to a record high of 12.2 million in 2007. By 2017, that number had declined by 1.7 million, or 14%. There were 10.5 million unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. in 2017, accounting for 3.2% of the nation’s population.

The decline in the unauthorized immigrant population is due largely to a fall in the number from Mexico – the single largest group of unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. Between 2007 and 2017, this group decreased by 2 million. Meanwhile, there was a rise in the number from Central America and Asia.

Do all lawful immigrants choose to become U.S. citizens?

Not all lawful permanent residents choose to pursue U.S. citizenship. Those who wish to do so may apply after meeting certain requirements , including having lived in the U.S. for five years. In fiscal year 2019, about 800,000 immigrants applied for naturalization. The number of naturalization applications has climbed in recent years, though the annual totals remain below the 1.4 million applications filed in 2007.

Generally, most immigrants eligible for naturalization apply to become citizens. However, Mexican lawful immigrants have the lowest naturalization rate overall. Language and personal barriers, lack of interest and financial barriers are among the top reasons for choosing not to naturalize cited by Mexican-born green card holders, according to a 2015 Pew Research Center survey .

Where do immigrants come from?

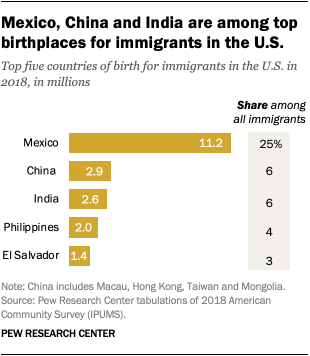

Mexico is the top origin country of the U.S. immigrant population. In 2018, roughly 11.2 million immigrants living in the U.S. were from there, accounting for 25% of all U.S. immigrants. The next largest origin groups were those from China (6%), India (6%), the Philippines (4%) and El Salvador (3%).

By region of birth, immigrants from Asia combined accounted for 28% of all immigrants, close to the share of immigrants from Mexico (25%). Other regions make up smaller shares: Europe, Canada and other North America (13%), the Caribbean (10%), Central America (8%), South America (7%), the Middle East and North Africa (4%) and sub-Saharan Africa (5%).

Who is arriving today?

More than 1 million immigrants arrive in the U.S. each year. In 2018, the top country of origin for new immigrants coming into the U.S. was China, with 149,000 people, followed by India (129,000), Mexico (120,000) and the Philippines (46,000).

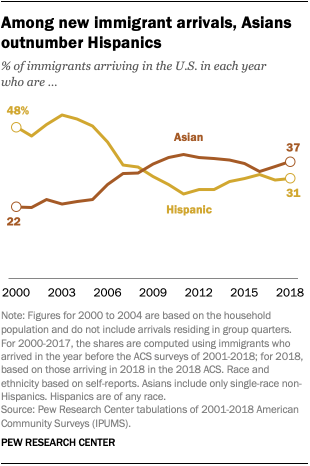

By race and ethnicity, more Asian immigrants than Hispanic immigrants have arrived in the U.S. in most years since 2009. Immigration from Latin America slowed following the Great Recession, particularly for Mexico, which has seen both decreasing flows into the United States and large flows back to Mexico in recent years.

Asians are projected to become the largest immigrant group in the U.S. by 2055, surpassing Hispanics. Pew Research Center estimates indicate that in 2065, those who identify as Asian will make up some 38% of all immigrants; as Hispanic, 31%; White, 20%; and Black, 9%.

Is the immigrant population growing?

New immigrant arrivals have fallen, mainly due to a decrease in the number of unauthorized immigrants coming to the U.S. The drop in the unauthorized immigrant population can primarily be attributed to more Mexican immigrants leaving the U.S. than coming in .

Looking forward, immigrants and their descendants are projected to account for 88% of U.S. population growth through 2065 , assuming current immigration trends continue. In addition to new arrivals, U.S. births to immigrant parents will be important to future growth in the country’s population. In 2018, the percentage of women giving birth in the past year was higher among immigrants (7.5%) than among the U.S. born (5.7%). While U.S.-born women gave birth to more than 3 million children that year, immigrant women gave birth to about 760,000.

How many immigrants have come to the U.S. as refugees?

Since the creation of the federal Refugee Resettlement Program in 1980, about 3 million refugees have been resettled in the U.S. – more than any other country.

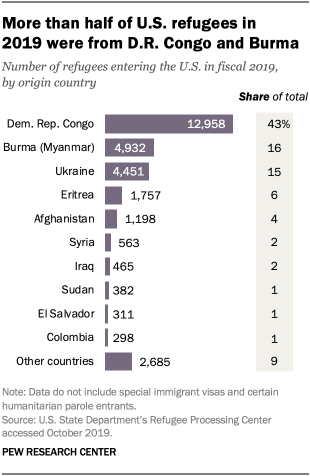

In fiscal 2019, a total of 30,000 refugees were resettled in the U.S. The largest origin group of refugees was the Democratic Republic of the Congo, followed by Burma (Myanmar), Ukraine, Eritrea and Afghanistan. Among all refugees admitted in fiscal year 2019, 4,900 are Muslims (16%) and 23,800 are Christians (79%). Texas, Washington, New York and California resettled more than a quarter of all refugees admitted in fiscal 2018.

Where do most U.S. immigrants live?

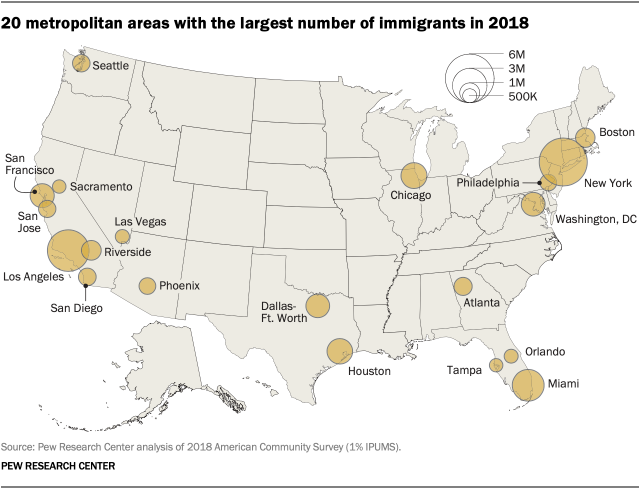

Nearly half (45%) of the nation’s immigrants live in just three states: California (24%), Texas (11%) and Florida (10%) . California had the largest immigrant population of any state in 2018, at 10.6 million. Texas, Florida and New York had more than 4 million immigrants each.

In terms of regions, about two-thirds of immigrants lived in the West (34%) and South (34%). Roughly one-fifth lived in the Northeast (21%) and 11% were in the Midwest.

In 2018, most immigrants lived in just 20 major metropolitan areas, with the largest populations in the New York, Los Angeles and Miami metro areas. These top 20 metro areas were home to 28.7 million immigrants, or 64% of the nation’s total foreign-born population. Most of the nation’s unauthorized immigrant population lived in these top metro areas as well.

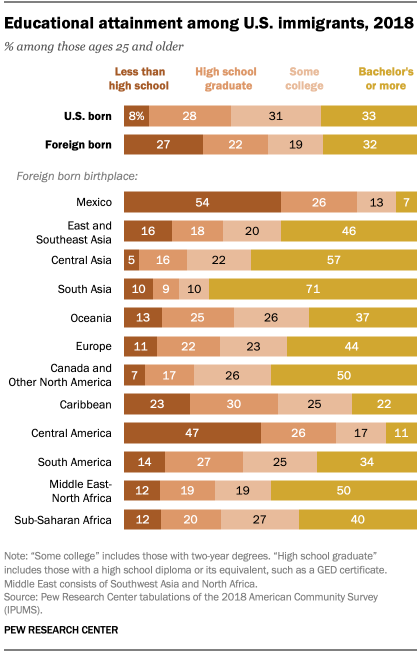

How do immigrants compare with the U.S. population overall in education?

Immigrants in the U.S. as a whole have lower levels of education than the U.S.-born population. In 2018, immigrants were over three times as likely as the U.S. born to have not completed high school (27% vs. 8%). However, immigrants were just as likely as the U.S. born to have a bachelor’s degree or more (32% and 33%, respectively).

Educational attainment varies among the nation’s immigrant groups, particularly across immigrants from different regions of the world. Immigrants from Mexico and Central America are less likely to be high school graduates than the U.S. born (54% and 47%, respectively, do not have a high school diploma, vs. 8% of U.S. born). On the other hand, immigrants from every region except Mexico, the Caribbean and Central America were as likely as or more likely than U.S.-born residents to have a bachelor’s or advanced degree.

Among all immigrants, those from South Asia (71%) were the most likely to have a bachelor’s degree or more. Immigrants from Mexico (7%) and Central America (11%) were the least likely to have a bachelor’s or higher.

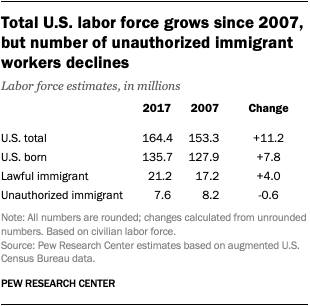

How many immigrants are working in the U.S.?

In 2017, about 29 million immigrants were working or looking for work in the U.S., making up some 17% of the total civilian labor force. Lawful immigrants made up the majority of the immigrant workforce, at 21.2 million. An additional 7.6 million immigrant workers are unauthorized immigrants , less than the total of the previous year and notably less than in 2007, when they were 8.2 million. They alone account for 4.6% of the civilian labor force, a dip from their peak of 5.4% in 2007. During the same period, the overall U.S. workforce grew, as did the number of U.S.-born workers and lawful immigrant workers.

Immigrants are projected to drive future growth in the U.S. working-age population through at least 2035. As the Baby Boom generation heads into retirement, immigrants and their children are expected to offset a decline in the working-age population by adding about 18 million people of working age between 2015 and 2035.

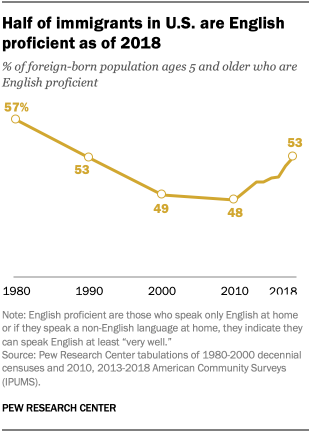

How well do immigrants speak English?

Among immigrants ages 5 and older in 2018, half (53%) are proficient English speakers – either speaking English very well (37%) or only speaking English at home (17%).

Immigrants from Mexico have the lowest rates of English proficiency (34%), followed by those from Central America (35%), East and Southeast Asia (50%) and South America (56%). Immigrants from Canada (96%), Oceania (82%), Europe (75%) and sub-Saharan Africa (74%) have the highest rates of English proficiency.

The longer immigrants have lived in the U.S. , the greater the likelihood they are English proficient. Some 47% of immigrants living in the U.S. five years or less are proficient. By contrast, more than half (57%) of immigrants who have lived in the U.S. for 20 years or more are proficient English speakers.

Among immigrants ages 5 and older, Spanish is the most commonly spoken language . Some 42% of immigrants in the U.S. speak Spanish at home. The top five languages spoken at home among immigrants outside of Spanish are English only (17%), followed by Chinese (6%), Hindi (5%), Filipino/Tagalog (4%) and French (3%).

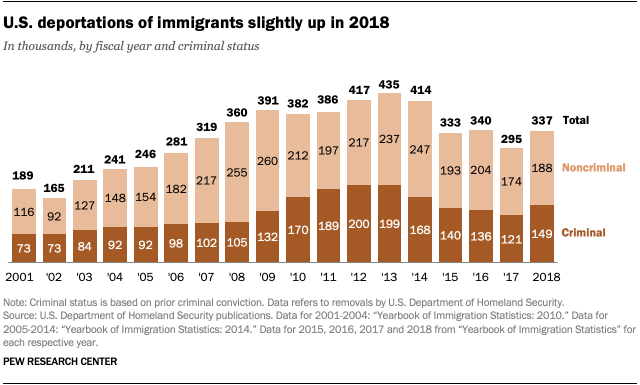

How many immigrants have been deported recently?

Around 337,000 immigrants were deported from the U.S. in fiscal 2018 , up since 2017. Overall, the Obama administration deported about 3 million immigrants between 2009 and 2016, a significantly higher number than the 2 million immigrants deported by the Bush administration between 2001 and 2008. In 2017, the Trump administration deported 295,000 immigrants, the lowest total since 2006.

Immigrants convicted of a crime made up the less than half of deportations in 2018, the most recent year for which statistics by criminal status are available. Of the 337,000 immigrants deported in 2018, some 44% had criminal convictions and 56% were not convicted of a crime. From 2001 to 2018, a majority (60%) of immigrants deported have not been convicted of a crime.

How many immigrant apprehensions take place at the U.S.-Mexico border?

The number of apprehensions at the U.S.-Mexico border has doubled from fiscal 2018 to fiscal 2019, from 396,579 in fiscal 2018 to 851,508 in fiscal 2019. Today, there are more apprehensions of non-Mexicans than Mexicans at the border. In fiscal 2019, apprehensions of Central Americans at the border exceeded those of Mexicans for the fourth consecutive year. The first time Mexicans did not make up the bulk of Border Patrol apprehensions was in 2014.

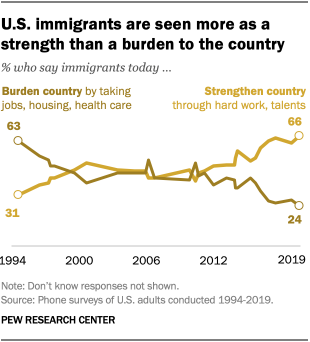

How do Americans view immigrants and immigration?

While immigration has been at the forefront of a national political debate, the U.S. public holds a range of views about immigrants living in the country. Overall, a majority of Americans have positive views about immigrants. About two-thirds of Americans (66%) say immigrants strengthen the country “because of their hard work and talents,” while about a quarter (24%) say immigrants burden the country by taking jobs, housing and health care.

Yet these views vary starkly by political affiliation. Among Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, 88% think immigrants strengthen the country with their hard work and talents, and just 8% say they are a burden. Among Republicans and Republican-leaning independents, 41% say immigrants strengthen the country, while 44% say they burden it.

Americans were divided on future levels of immigration. A quarter said legal immigration to the U.S. should be decreased (24%), while one-third (38%) said immigration should be kept at its present level and almost another third (32%) said immigration should be increased.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published May 3, 2017, and written by Gustavo López, a former research analyst focusing on Hispanics, immigration and demographics; and Kristen Bialik, a former research assistant.

CORRECTION (Sept. 21, 2020): An update to the methodology used to tabulate figures in the chart “Among new immigrant arrivals, Asians outnumber Hispanics” has changed all figures from 2001 and 2012. This new methodology has also allowed the inclusion of the figure from 2000. Furthermore, the earlier version of the chart incorrectly showed the partial year shares of Hispanic and Asian recent arrivals in 2015; the corrected complete year shares are 31% and 36%, respectively.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

Key facts about U.S. immigration policies and Biden’s proposed changes

Most latinos say u.s. immigration system needs big changes, facts on u.s. immigrants, 2018, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

The Integration of Immigrants into American Society (2015)

Chapter: summary.

The United States prides itself on being a nation of immigrants, and the nation has a long history of successfully absorbing people from across the globe. The successful integration of immigrants and their children contributes to economic vitality and to a vibrant and ever-changing culture. Americans have offered opportunities to immigrants and their children to better themselves and to be fully incorporated into U.S. society, and in exchange immigrants have become Americans —embracing an American identity and citizenship, protecting the United States through service in its military, fostering technological innovation, harvesting its crops, and enriching everything from the nation’s cuisine to its universities, music, and art.

2015 marked the 50th anniversary of the passage of the Immigration Act of 1965, which began the most recent period of mass immigration to the United States. This act abolished the restrictive quota system of the 1920s and opened up legal immigration to all the countries in the world, helping to set the stage for a dramatic increase in immigration from Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. At the same time, it limited the numbers of legal immigrants coming from countries in the Western Hemisphere, thus establishing restrictions on immigrants across the U.S. southern border and setting the stage for the rise in undocumented border crossers. Although the Immigration Act of 1965 exemplified the progressive ideals of the 1960s, the system it engendered may also hinder some immigrants’ and their descendants’ prospects for integration.

Today, the 41 million immigrants in the United States represent 13.1 percent of the U.S. population. The U.S.-born children of immigrants, the

second generation, represent another 37.1 million people, or 12 percent of the population. Thus, together the first and second generations account for one out of four members of the U.S. population. Whether they are successfully integrating is therefore a pressing and important question.

To address this question, the Panel on the Integration of Immigrants into American Society was charged with (1) summarizing what is known about how immigrants and their descendants are integrating into American society; (2) discussing the implications of this knowledge for informing various policy options; and (3) identifying any important gaps in existing knowledge and data availability. Another panel appointed under the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine will be publishing its final report later this year; that report will examine the economic and fiscal impacts of immigration and present projections of immigration and of related economic and fiscal trends in the future. That report will complement but does not overlap with this panel’s work on immigrant integration.