- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Segregation in the United States

By: History.com Editors

Updated: January 12, 2023 | Original: November 28, 2018

Segregation is the practice of requiring separate housing, education and other services for people of color. Segregation was made law several times in 19th- and 20th-century America as some believed that Black and white people were incapable of coexisting.

In the lead-up to the liberation of enslaved people under the Thirteenth Amendment , abolitionists argued about what the fate of slaves should be once they were freed. One group argued for colonization, either by returning the formerly enslaved people to Africa or creating their own homeland. In 1862 President Abraham Lincoln recognized the ex-slave countries of Haiti and Liberia, hoping to open up channels for colonization, with Congress allocating $600,000 to help. While the colonization plan did not pan out, the country, instead, set forth on a path of legally mandated segregation.

Black Codes and Jim Crow

The first steps toward official segregation came in the form of “ Black Codes .” These were laws passed throughout the South starting around 1865, that dictated most aspects of Black peoples’ lives, including where they could work and live. The codes also ensured Black people’s availability for cheap labor after slavery was abolished.

Segregation soon became official policy enforced by a series of Southern laws. Through so-called Jim Crow laws (named after a derogatory term for Blacks), legislators segregated everything from schools to residential areas to public parks to theaters to pools to cemeteries, asylums, jails and residential homes. There were separate waiting rooms for whites people and Black people in professional offices and, in 1915, Oklahoma became the first state to even segregate public phone booths.

Colleges were segregated and separate Black institutions like Howard University in Washington, D.C. and Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee were created to compensate. Virginia’s Hampton Institute was established in 1869 as a school for Black youth, but with white instructors teaching skills to relegate Black people in service positions to whites.

The Supreme Court and Segregation

In 1875 the outgoing Republican-controlled House and Senate passed a civil rights bill outlawing discrimination in schools, churches and public transportation. But the bill was barely enforced and was overturned by the Supreme Court in 1883.

In 1896, the Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that segregation was constitutional. The ruling established the idea of “separate but equal.” The case involved a mixed-race man who was forced to sit in the Black-designated train car under Louisiana’s Separate Car Act.

Housing Segregation

As part of the segregation movement, some cities instituted zoning laws that prohibited Black families from moving into white-dominant blocks. In 1917, as part of Buchanan v. Warley, the Supreme Court found such zoning to be unconstitutional because it interfered with property rights of owners.

Using loopholes in that ruling in the 1920s, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover created a federal zoning committee to persuade local boards to pass rules preventing lower-income families from moving into middle-income neighborhoods, an effort that targeted Black families. Richmond, Virginia, decreed that people were barred from residency on any block where they could not legally marry the majority of residents. This invoked Virginia’s anti-mixed race marriage law and was not technically in violation with the Supreme Court decision.

Segregation During the Great Migration

During the Great Migration , a period between 1916 and 1970, six million African Americans left the South. Huge numbers moved northeast and reported discrimination and segregation similar to what they had experienced in the South.

As late as the 1940s, it was still possible to find “Whites Only” signs on businesses in the North. Segregated schools and neighborhoods existed, and even after World War II , Black activists reported hostile reactions when Black people attempted to move into white neighborhoods.

Segregation and the Public Works Administration

The Public Works Administration’s efforts to build housing for people displaced during the Great Depression focused on homes for white families in white communities. Only a small portion of houses was built for Black families, and those were limited to segregated Black communities.

In some cities, previously integrated communities were torn down by the PWA and replaced by segregated projects. The reason given for the policy was that Black families would bring down property values.

Starting in the 1930s, the Federal Home Loan Bank Board and the Home Owners' Loan Corporation conspired to create maps with marked areas considered bad risks for mortgages in a practice known as “red-lining.” The areas marked in red as “hazardous” typically outlined Black neighborhoods. This kind of mapping concentrated poverty as (mostly Black) residents in red-lined neighborhoods had no access or only very expensive access to loans.

The practice did not begin to end until the 1970s. Then, in 2008, a system of “reverse red-lining,” which extended credit on unfair terms with subprime loans, created a higher rate of foreclosure in Black neighborhoods during the housing crisis.

In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled that a Black family had the right to move into their newly-purchased home in a quiet neighborhood in St. Louis, despite a covenant dating back to 1911 that precluded the use of the property in the area by “any person not of the Caucasian race.” In Shelley v. Kramer, attorneys from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) , led by Thurgood Marshall , argued that allowing such white-only real estate covenants were not only morally wrong, but strategically misguided in a time when the country was trying to promote a unified, anti-Soviet agenda under President Harry Truman . Civil rights activists saw the landmark case as an example of how to start to undo trappings of segregation at the federal level.

But while the Supreme Court ruled that white-only covenants were not enforceable, the real estate playing field was hardly leveled. The Housing Act of 1949 was proposed by Truman to solve a housing shortage caused by soldiers returned from World War II . The act subsidized housing for whites only, even stipulating that Black families could not purchase the houses even on resale. The program effectively resulted in the government funding white flight from cities.

One of the most notorious of the white-only communities created by the Housing Act was Levittown, New York, built in 1949 and followed by other Levittowns in different locations.

Segregation in Schools

Segregation of children in public schools was struck down by the Supreme Court as unconstitutional in 1954 with Brown v. Board of Education . The case was originally filed in Topeka, Kansas after seven-year-old Linda Brown was rejected from the all-white schools there.

A follow-up opinion handed decision-making to local courts, which allowed some districts to defy school desegregation. This led to a showdown in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957, when President Dwight D. Eisenhower deployed federal troops to ensure nine Black students entered high school after Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus had called in the National Guard to block them.

When Rosa Parks was arrested in 1955 after refusing to give up her bus seat to a white man in Montgomery, Alabama, the civil rights movement began in earnest. Through the efforts of organizers like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the resulting protests, the Civil Rights Act was signed in 1964, outlawing discrimination, though desegregation was a slow process, especially in schools.

Boston Busing Crisis

One of the worst incidents of anti-integration happened in 1974. Violence broke out in Boston when, in order to solve the city’s school segregation problems, courts mandated a busing system that carried Black students from predominantly Roxbury to South Boston schools, and vice versa.

The state had passed the Elimination of Racial Balance law in 1965, but it had been held up in court by Irish Catholic opposition. Police protected the Black students as several days of violence broke out between police and Southie residents. White crowds greeted the buses with insults, and further violence erupted between Southie residents and retaliating Roxbury crowds. State troopers were called in until the violence subsided after a few weeks.

Segregation in the 21st Century

Segregation persists in the 21st Century. Studies show that while the public overwhelmingly supports integrated schools, only a third of Americans want federal government intervention to enforce it.

The term “apartheid schools” describes still-existing, largely segregated schools, where white students make up 0 to 10 percent of the student body. The phenomenon reflects residential segregation in cities and communities across the country, which is not created by overtly racial laws, but by local ordinances that target minorities disproportionately.

Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America by Ibram X. Kendi , published by Bodley Head. The Case for Reparations by Ta-Nehisi Coates , The Atlantic . Dismantling Desegregation by Gary Orfield and Susan E. Eaton by the New Press.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Share full article

Advertisement

Subscriber-only Newsletter

Jamelle Bouie

How a still segregated country holds us all back.

By Jamelle Bouie

Opinion Columnist

Without question, the best thing I read this week was an essay for Dissent magazine by the legal scholar Aziz Rana on the challenge that racial segregation poses to the creation of a broad-based and emancipatory politics of class.

Although it is no longer enforced by law, racial segregation remains a fundamental part of the social order and political economy of the United States. “Throughout the country,” Rana writes, “in cities and rural areas, blue states and red ones, racial separation remains a common feature of collective life.” And while Americans have made meaningful progress toward integration in the decades since the civil rights movement, it is also true, as Rana notes, that “recent decades have brought profound backsliding, and many communities and institutions are more segregated now than they were 30 years ago.”

This isn’t a minor problem. Racial segregation does two things, essentially. The first is that it facilitates the exploitation of workers on both sides of the racial divide. One group is often subjected to the worst of capitalist exploitation and state repression, from wealth extraction and expropriation to being relegated to the most precarious forms of low-wage labor, if jobs are even available.

The other group is shielded, to an extent, from the brunt of the system’s ills. But because American-style segregation typically rests on the destruction of public goods, this shield is brittle and unreliable, as many white workers and their children discovered with the collapse of the New Deal economy and the rise of the neoliberal order in the last decades of the 20th century.

The other thing racial segregation does is inculcate racist ideologies as a kind of social learning. This, in fact, was the whole point, as W.E.B. Du Bois described in “Black Reconstruction in America.” “It must be remembered that the white group of laborers, while they received a low wage, were compensated in part by a sort of public and psychological wage,” Du Bois wrote. “They were given public deference and titles of courtesy because they were white. They were admitted freely with all classes of white people to public functions, public parks and the best schools.”

The effect of this was to cultivate a kind of chauvinism, as well as the sense of a cross-class solidarity among whites, which worked to undermine any feelings of solidarity or understanding between workers of different racial backgrounds.

Rana’s argument, in short, is that this process is still in effect. The legacy of our “long history of discriminatory practices by both the government and private sector, along with cycles of white self-isolation” means that even poor white families tend to live in segregated neighborhoods that are more prosperous than those inhabited by middle-class Black and Latino families.

“For white residents in these areas,” writes Rana, “daily activities — in local schools, churches, playgrounds and businesses — reinforce a deep sense of shared cultural connection.” It creates the sense as well that the social integrity and even prosperity of those areas depends on their racial exclusivity. Whiteness is then entangled in the idea of security, economic or otherwise.

It was exactly this entanglement that Donald Trump exploited to such powerful effect in his 2016 presidential election campaign, and which continues to fuel the rhetoric of conservative “populists” like Tucker Carlson of Fox News.

Left-wing projects, argues Rana, “require more than simply making arguments about economic interest. They require a cultural infrastructure, in which left values are present in the everyday institutions that organize people’s experiences. Without that infrastructure, it is incredibly hard to shift people’s political views.”

The civil rights movement envisioned a fully integrated world of neighborhoods, homes, churches and schools where people could, in Rana’s words, “encounter one another, recognize common grievances and develop ties of solidarity.”

We don’t quite have the opposite of this, but we are also far from meaningful integration. Most neighborhoods, schools and churches are segregated, and with the decline of unions there are few places where ordinary people of different races actually face one another as equals and learn to work with and understand one another.

For Rana, the long-term goal of the left has to be “nothing less than finally overcoming the segregated nature of American life.” There are no simple answers, he says, “but a key part of the solution is for more and more Americans to come to believe that the problems they face can be overcome only by embracing equal and effective freedom for all, including those on the margins.” And for this to occur, “individuals must, on a day-to-day basis, inhabit institutions that promote cross-group solidarity and exchange.”

I agree. As many, many Americans have recognized over the course of our history, you can have race hierarchy and exclusion or you can have meaningful equality for all, but you simply cannot have both.

What I Wrote

My Tuesday column focused on the Supreme Court and its claims to legitimacy, with an interpretive assist from the Notorious B.I.G.

One of the cardinal rules of power, as Christopher Wallace once said in the fourth of his “Ten Crack Commandments,” is to never get high on your own supply. Put differently, it is important for people in positions of influence to stay aware of the limits of their perception and ability. To buy your own hype or indulge your own propaganda — to treat your image as reality and close yourself to criticism and critique — is to court disaster.

My Friday column asked whether the problem with our democracy is the Constitution itself, with an assist from Jedediah Purdy’s new book on politics and American democracy.

We tend to equate American democracy with the Constitution, as if the two were synonymous with each other. To defend one is to protect the other and vice versa. But our history makes clear that the two are in tension with each other — and always have been.

And in the latest episode of my podcast with John Ganz, we discussed “Passenger 57,” one of the many “Die Hard”-style action movies of the 1990s.

Now Reading

Jay Swanson on the left and the Constitution for The Nation.

Sarah Laskow on American food for The Atlantic.

Dayna Tortorici on the movement to criminalize abortion for N+1 magazine.

Andrea Sempértegui on the strike of Indigenous workers in Ecuador for The New York Review of Books.

Lisa Heinzerling on the Supreme Court’s attack on the administrative state for Boston Review.

Feedback If you’re enjoying what you’re reading, please consider recommending it to your friends. They can sign up here . If you want to share your thoughts on an item in this week’s newsletter or on the newsletter in general, please email me at [email protected] . You can follow me on Twitter ( @jbouie ), Instagram and TikTok .

Photo of the Week

We haven’t had a chance to go to any pumpkin patches yet, so instead of a recent photo I thought I would share this one from last October, when we went to a pumpkin patch and corn maze out in Nelson County, Va.

Now Eating: Beans With Roasted Chiles and Cilantro

This is a very simple and easy recipe from Rick Bayless’s “ Authentic Mexican ,” written with Deann Groen Bayless. The dish is best served with plenty of garnishes, like diced avocado, sliced radishes and even some sliced jalapeños for heat. I also add a squeeze of lime to brighten things a little. Also, tortillas on the side. I am giving you the recipe as written, but it is incredibly easy to make it without the bacon. Just use olive oil instead.

Ingredients

1 pound pinto or other light-colored beans

2 cloves garlic, crushed

1 half of an onion

8 thick slices bacon, cut into ½-inch cubes

1 medium onion, diced

2 large, fresh poblano chiles, roasted and peeled, seeded and chopped

2 medium ripe tomatoes, cored, peeled and chopped, or 1 15-ounce can tomatoes, drained and chopped

about 1 teaspoon salt

at least ½ cup chopped fresh cilantro

Pick over the beans for any rocks, then rinse and place in a 4-quart pot. Add plenty of water and then soak for 4-8 hours.

When you’re ready to cook, drain beans and add to a pot with 2 quarts fresh water, 2 crushed cloves of garlic, ½ onion and 1 bay leaf. Bring to a boil, partially cover and simmer for 1-2 hours, until the beans are tender. Remove the onion and bay leaf.

Fry bacon in a medium-size skillet over medium-low heat until crisp, about 10 minutes. Remove bacon, pour off all but 2 tablespoons of fat and raise the heat to medium. Add the onion and chiles and fry until the onion is a deep golden brown, about 8 minutes. Stir in the tomato and cook until all the liquid has evaporated.

Add the tomato mixture, bacon and salt to the cooked beans. Simmer, stirring occasionally, for 20-30 minutes, to blend the flavors. If the beans are very soupy, uncover, raise the heat and simmer away the excess liquid. For a thicker broth, purée 2 cups of the beans (with their liquid) and return to the pot. Just before serving, taste for salt and stir in cilantro. Serve with garnishes and tortillas.

Jamelle Bouie became a New York Times Opinion columnist in 2019. Before that he was the chief political correspondent for Slate magazine. He is based in Charlottesville, Va., and Washington. @ jbouie

- In the News

- News & Events

- Data Updates

- Research & Policy

- Press Releases

Research Areas

- Homelessness

- Housing Choice Vouchers (Section 8)

- Inclusionary Zoning

- Mitchell Lama

- Preservation and Opt outs

- Property Taxes

- Public Housing/NYCHA

- Rent Regulation/Stabilization

- Multifamily Housing Resilience

- Planning for Climate Change

- Superstorm Sandy

- Foreclosure

- Homeownership

- Housing Prices

- Land Prices

- Rental Housing Finance

- Housing Court

- Historic Preservation & Landmarks

- Transferable Development Rights

- Hotel Conversions

- Office Conversions

- Public Safety

- Economic Development

- Gentrification

- Racial/Ethnic Segregation

- Schools & Education

- View All Publications

- About Our Research

Publication Type

- Books/Chapters

- Policy Briefs

- Data Briefs

- White Papers

- Working Papers

- NYS Housing 2023

- In Our Backyard

- The Dream Revisited

- Policy Minute

- Policy Breakfasts

- Housing Solutions Lab

- Directory of NYC Housing Programs

- Neighborhood Data Profiles

- State of NYC Housing & Neighborhoods

- Introduction

- Discussions

Why Haven’t We Made More Progress in Reducing Segregation?

by Margery Austin Turner | April 2014

Recent surveys strongly suggest that Americans would prefer to live in more racially and ethnically diverse neighborhoods than they do. So why does residential segregation remain so stubbornly high?

The historical record clearly demonstrates that our nation’s stark patterns of racial segregation were established through public policy, including the enforcement of restrictive covenants, local land use regulations, underwriting requirements for federally insured mortgage loans, and siting and occupancy regulations for public housing. But the dynamics that sustain segregation today are far more complex and subtle.

Here’s my take on the tangle of factors that perpetuate segregation and undermine the stability of mixed neighborhoods. (It’s important to note that most of the available evidence focuses on black-white segregation, despite our nation’s growing ethnic diversity and significant challenges facing Latinos, Asians, and Native Americans.)

Discrimination constrains minorities’ housing search. The most recent national paired-testing study of housing market discrimination finds that minority homeseekers (blacks, Latinios, and Asians) are still told about and shown fewer homes and apartments than equally qualified whites. These subtle forms of discrimination limit minorities’ information about available housing options and raise their costs of search. But discrimination today rarely takes the form of outright denial of access to housing in predominantly white neighborhoods. So although discrimination remains a serious problem, it cannot account for the high levels of segregation in most metropolitan housing markets.

Advertising and information sources may limit housing choices. A small number of studies (all conducted over a decade ago) suggest that homes in majority-black neighborhoods are advertised quite differently than similarly priced homes in predominantly white neighborhoods and that blacks and whites rely on different sources of information and employ different search strategies. But all these studies were completed before the widespread use of the internet in real estate marketing and information gathering. So we don’t know whether disparities in information sources and search strategies between minorities and whites play any significant role in the perpetuation of segregation today. This is an area where we really need to learn more (and Maria Krysan is currently leading a HUD-funded study that will do just that).

Affordability barriers contribute to racial and ethnic segregation. Whites on average have higher incomes and wealth (due in part to past patterns of discrimination and segregation) and can therefore afford to live in neighborhoods that are out of reach for many minorities. But these economic differences can only account for a modest share of the segregation that remains today, particularly between blacks and whites. If households were distributed across neighborhoods entirely on the basis of income (regardless of race or ethnicity), levels of black-white segregation would be dramatically lower. So affordability plays a role but it’s definitely not the whole story.

Most minority homeseekers prefer mixed neighborhoods. Some people argue that neighborhood segregation today is largely a matter of choice – that minorities prefer to live in neighborhoods where their own race or ethnicity predominates and choose not to move to white neighborhoods. And indeed, the evidence confirms that the average black person’s ideal neighborhood has more blacks living in it than the average white person’s ideal neighborhood, that few blacks want to be the first to move into a white neighborhood, and that most blacks prefer neighborhoods where their own race accounts for about half the population.

But few blacks actually express a preference for living in predominantly black neighborhoods and it’s difficult to disentangle a positive preference for living among other black families from fear of hostility from white neighbors. Surveys suggest that many blacks are hesitant to move to predominantly white neighborhoods primarily because of concerns about hostility – concerns that have been painfully reinforced by the shooting of Trayvon Martin.

Many whites avoid neighborhoods with large or growing minority populations.Considerable evidence suggests that the choices of white people play a major role in perpetuating neighborhood segregation. First, very few whites express any interest in moving into neighborhoods that are predominantly minority, probably in large part because predominantly minority neighborhoods have been deprived of the public and private investments that comparable white neighborhoods enjoy. In other words, the legacy of past discrimination and disinvestment puts most minority neighborhoods at a significant disadvantage from the perspective of white homeseekers for whom alternative choices abound.

But many whites are also unwilling to move to (or remain in) neighborhoods with smaller, but significant or rising, minority shares. To some extent, this reflects old-fashioned prejudice – an aversion to minority neighbors. And for some whites, living in an area with neighbors of color may be seen as an indicator of lower social status. But survey evidence suggests that these attitudes have declined over recent decades and today very few neighborhoods (at least in metro areas) remain exclusively white, suggesting that most white households have accepted having at least some minority neighbors.

Nonetheless, many white people fear that a substantial minority presence will inevitably lead to the neighborhood becoming predominantly minority, with a subsequent downward spiral of declining property values, disinvestment, and crime. These fears cause them to avoid moving into mixed neighborhoods and, in some cases, to flee as minorities move into neighborhoods where they live. This avoidance by whites of neighborhoods that probably look especially welcoming to minority homeseekers leads to resegregation and reinforces everybody’s expectations about racial tipping.

Given the complexity – and subtlety – of the processes sustaining residential segregation in urban America today, how should public policy respond? In my view, there can be no question that public intervention is essential. But the solutions have to be both nuanced and multi-faceted, addressing the interacting barriers of discrimination, information gaps, affordability constraints, prejudice, and fear.

Cashin, Sheryll. 2004. The Failures of Integration: How Race and Class Undermine America’s Dream. New York: PublicAffairs.

Charles, Camille Zubrinksy. 2005. “Can We Live Together? Racial Preferences and Neighborhood Outcomes,” in Xavier de Souza Briggs, ed., The Geography of Opportunity: Race and Housing Choice in Metropolitan America. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Ellen, Ingrid Gould. 2008. “Continuing Isolation: Segregation in America Today.” In Segregation: The Rising Costs for America, edited by James H. Carr and Nandinee K. Kutty (261-277). New York: Routledge.

Krysan, Maria. 2002. “Community Undesirability in Black and White: Examining Racial Residential Preferences through Community Perceptions.” Social Problems. 49(4):521-543.

Krysan, Maria. 2002. “Whites Who Say They’d Flee: Who Are They, and Why Would They Leave?” Demography. 39(4):675-696.

Krysan, Maria and Reynolds Farley. 2002. “The Residential Preferences of Blacks: Do They Explain Persistent Segregation?” Social Forces 80(3):937-980.

Margery Austin Turner is Senior Vice President for Program Planning and Management at the Urban Institute. Her areas of expertise include urban policy and neighborhood issues.

More in Discussion 3: Ending Segregation: Our Progress Today

Why haven’t we made more progress in reducing segregation.

by Margery Austin Turner

Economic Segregation of Schools is Key to Discouraging Integration

by Micere Keels

Exclusionary Zoning & Fear: A Developer’s Perspective

by Jon Vogel

How Do We Reconcile Increasing Interest in Residential Diversity with Persistent Racial Segregation?

by Camille Zubrinsky Charles

All content © 2005 – 2024 Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy | Top of page | Contact Us

How did African Americans respond to Jim Crow and did they view separation and segregation in the same way? Having students Students should understand the difference between voluntary separation and segregation. compare the two should reveal that for the most part African Americans did not oppose separation so long as it was voluntary. Following the Civil War, blacks formed their own schools, churches, and civic organizations over which they exercised control that provided independence from white authorities, including their former masters. African Americans took great pride in the institutions they built in their communities. Black businessmen accumulated wealth by catering to a Negro clientele in need of banks, insurance companies, health services, barber shops and beauty parlors, entertainment, and funeral homes. African Americans as diverse politically as Booker T. Washington in the 1890s , Marcus Garvey in the 1920s , W.E.B. DuBois in the 1930s advocated that blacks concentrate on promoting self-help within their communities and develop their own economic, Integration weakened some black community institutions. social, and cultural institutions. Ironically, one of the unintended side effects of racial integration in the second half of the twentieth century was the erosion of longstanding black business and educational institutions that served African-Americans during Jim Crow.

Students can then see that in contrast to voluntary separation and self-determination, segregation was coercive and grew out of attempts to maintain black subordination and second-class citizenship. Sanctioned by the government, Jim Crow demeaned African Americans, denied them equal opportunity, and assigned them to the margins of public life. If African Americans overstepped Jim Crow’s boundary lines they were forced back by law and, if necessary, through retributive violence.

How did African Americans challenge segregation and white supremacy ? In other words, when did the Civil Rights Movement begin and Begin your teaching of the Civil Rights Movement with World War II. what did it seek to accomplish? These are questions that historians still debate. My advice is to start before the usual launching point of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 and begin with World War II, when African Americans began a “ Double V” Campaign —victory against totalitarianism abroad and racism at home. The continued migration of blacks to the North and West gave African Americans increased voting power to help pressure presidents from Harry Truman on to pass civil rights legislation that would aid their family, friends, and neighbors remaining in the South. At the same time, southern black communities organized and mobilized. A new generation of leaders, many of them military veterans or black college graduates , challenged Jim Crow and disfranchisement. Black women have often been ignored as a significant force behind the Civil Rights Movement, with the focus on the men who led the major organizations. However, teachers should emphasize the role of mothers who permitted their children to face the dangers of integrating schools , daughters who readily joined protest demonstrations, domestic servants who walked miles to work to boycott segregated buses , and churchwomen who rallied their congregations behind civil rights.

Finally, what did African Americans strive for in eliminating segregation? Usually integration is wrongly interpreted as an end in itself or an attempt by blacks to Stress that integration was a tactic, not a goal. assimilate into white society. It is most important for students to understand that for blacks integration was a tactic, not a goal. For example, African Americans sought to desegregate education not because they wanted to socialize with white students, but because it provided the best means for obtaining a quality education. Blacks confronted Jim Crow to defeat white supremacy and obtain political power —the kind that could result in jobs, affordable housing, satisfactory health care, and evenhanded treatment by the police and the judicial system. Rather than erasing their pride in being black or expressing a desire to be like whites , African Americans gained an even greater respect for their race through participation in the Civil Rights Movement and their efforts to shatter Jim Crow.

Historians Debate

In 1955, C. Vann Woodward published The Strange Career of Jim Crow . Woodward reflected the optimism following the previous year’s Brown decision by arguing that segregation was not as inherent to southern society as previously believed. He demonstrated that not until the 1890s did southern whites institute the rigid system of Jim Crow that segregated the races in all areas of public life. Woodward pointed out numerous instances during and after Reconstruction when blacks had access to public accommodations. Woodward’s research suggested that segregation might be eradicated through simple changes in public policies, reversing those that had created it in the not-so-distant past.

Woodward’s book spawned a number of other studies both challenging and modifying his thesis. Many of these appeared as the South waged massive resistance to combat the efforts of the Civil Rights Movement in the late 1950s and early 1960s, suggesting the depth of white racism and the difficulty of overcoming it. In North of Slavery (1961), Leon Litwack found that even before the Civil War free northern Negroes encountered segregation in schools and public accommodations, the kind of discrimination they would face in the South after slavery. Accordingly, segregation had a longer pedigree than Woodward had argued, and it transcended the South and operated nationwide. Joel Williamson’s After Slavery: The Negro in South Carolina during Reconstruction, 1861-1877 (1965) examined race relations in the Palmetto State and found Woodward’s interpretation wanting. Williamson concluded that freed blacks encountered segregation soon after emancipation. He asserted that specific laws were not necessary to keep the races apart because segregation was maintained de facto . He discovered that most white South Carolinians did not accept racial equality and intended to adopt segregation as soon as blacks gained their freedom from slavery.

Howard N. Rabinowitz did not focus so much on the timing of segregation as on its form. In Race Relations in the Urban South, 1865-1890 (1978), Rabinowitz argued that racial segregation appeared as a substitute for racial exclusion. Thus, in the post-emancipation South freed blacks gained access for the first time to public facilities such as public transportation and health and welfare services. Accordingly, segregation should not be perceived as a punitive measure but as a means of extending services, albeit separate and unequal, to African Americans.

To summarize, historians generally agree that de facto segregation both preceded and accompanied de jure segregation, but that racial interaction in public spheres was less rigid than it became after the 1890s. Whatever its form, however, Jim Crow was always separate and never equal; it constituted a means for reinforcing black subordination and white supremacy. Whatever the exact beginning of segregation, southern whites shared a broad consensus for preserving it. It required a mass, black-led, Civil Rights Movement, combined with the power and renewed willingness of the national government, to overthrow Jim Crow.

Steven F. Lawson was a Fellow at the National Humanities Center in 1987-88. He holds a Ph.D. in American History from Columbia University and is currently Professor of History at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. Dr. Lawson is author of Black Ballots: Voting Rights in the South, 1944-1969 (1976), which won the Phi Alpha Theta prize for best first book; In Pursuit of Power: Southern Blacks and Electoral Politics, 1965-1982 (1985); Civil Rights Crossroads: Nation, Community, and the Black Freedom Struggle (2003) ; and Running for Freedom: Civil Rights and Black Politics in America since 1941 (3 rd ed., 2009).

Illustration credits

To cite this essay: Lawson, Steven F. “Segregation.” Freedom’s Story, TeacherServe©. National Humanities Center. DATE YOU ACCESSED ESSAY. <https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/freedom/1865-1917/essays/segregation.htm>

NHC Home | TeacherServe | Divining America | Nature Transformed | Freedom’s Story About Us | Site Guide | Contact | Search

TeacherServe® Home Page National Humanities Center 7 Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256 Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709 Phone: (919) 549-0661 Fax: (919) 990-8535 Copyright © National Humanities Center. All rights reserved. Revised: May 2010 nationalhumanitiescenter.org

- Events Calendar

- Featured Story

UCLA Civil Rights Project Assesses School Segregation 70 Years After Brown

“We are witnessing a multi-decade retreat from school integration"

A new report published by the UCLA Civil Rights Project, The Unfinished Battle for Integration in a Multiracial America – from Brown to Now , discusses the present realities of school segregation and the patterns of change over 70 years since the Brown v. Board ruling.

“We desegregated our schools when a serious effort was made and there were major benefits for all students. However, there has been no significant effort to support integration for nearly 50 years, and we are betting our educational and social future on inaction, which has never produced equal opportunity,” said report co-author Gary Orfield, the co-director of the Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles at UCLA.

“We are witnessing a multi-decade retreat from school integration, which undermines the potential of our public education system to reduce prejudice, tackle social inequality, and thus shore up the foundations of democracy,” adds Ryan Pfleger, Senior Policy Research Analyst at the Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles and a co-author of the report.

Brown v. Board of Education was a turning point in American law and race relations. In a country where segregated education was the law in seventeen states with completely separate and unequal schools, Brown found that segregation was “inherently unequal” and violated the Constitution.

The high point of integration for Black students occurred in the 1980s, but there has been steady resegregation since the Rehnquist Supreme Court changed desegregation policy with the Dowell decision in 1991. The turning point toward greater segregation came after the Court decided desegregation requirements could only be temporary, and control should be turned back to the institutions that discriminated before Brown .

The Supreme Court also recognized the desegregation rights of Latino students in 1973 but there was little enforcement. Latino students, who had often been in diverse schools, became as segregated as Blacks by the 1980s.

Seventy years later the school integration that came with the civil rights movement continues to be dismantled. The new report shows that when Brown was decided, and the 1964 Civil Rights Act took hold, four in five U.S. students were white, but that percentage is now just 45%. Schools presently are about a sixth Black, and immigration has spurred the growth of Latinos from 5% to 28% of all U.S. students, while Asians are now the fastest growing racial group.

The report shows that major gains for Blacks occurred in all Southern states after the Civil Rights Act was enforced. At its high point in the 1980s, 43% of Black Southern students attended majority white schools, up from 0% when Brown was decided in 1954. Now the percentage is down to 16%. Segregation today is highest in our nation’s big cities where Black and Latino students attend schools with an average of more than 80% nonwhite classmates. Major sectors of suburbia are changing fast and have serious segregation. Rural areas are less segregated.

Over the last 30 years, the proportion of schools that were intensely segregated (with zero to 10% whites) has nearly tripled, rising from 7.4% to 20%. These schools are now doubly segregated by race and poverty with an average of 78% poor students.

A large body of research shows that such schools typically lack key resources and have much weaker outcomes for students. White and Asian students attend middle-class schools at much higher proportions. Moreover, the data show that the declining share of white students in the nation’s schools are less isolated from nonwhite students than in the past. As their numbers grow, nonwhite students are, however, substantially more isolated from whites and the white share of students drops as immigration has changed the racial profile of the society.

School choice policies have contributed to the resegregation of the nation’s schools. Both magnet and charter schools could be used to desegregate but are now substantially segregated, charter schools more intensely so.

The Civil Rights Project will be publishing a report in late April comparing magnet and charter school segregation.

The Unfinished Battle for Integration in a Multiracial America – from Brown to Now is available on the Civil Rights Project website .

- Brown V. Board

- Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles

- Gary Orfield

- Knowledge that Matters

- Ryan Pfleger

Personal tools

Skip to content. | Skip to navigation

- Legal Developments

The Civil Rights Project / Proyecto Derechos Civiles 8370 Math Sciences, Box 951521 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1521 [email protected]

- Copyright Policy

- Accessibility

Copyright © 2010 UC Regents

Read our research on: Gun Policy | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Black americans have a clear vision for reducing racism but little hope it will happen, many say key u.s. institutions should be rebuilt to ensure fair treatment.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to understand the nuances among Black people on issues of racial inequality and social change in the United States. This in-depth survey explores differences among Black Americans in their views on the social status of the Black population in the U.S.; their assessments of racial inequality; their visions for institutional and social change; and their outlook on the chances that these improvements will be made. The analysis is the latest in the Center’s series of in-depth surveys of public opinion among Black Americans (read the first, “ Faith Among Black Americans ” and “ Race Is Central to Identity for Black Americans and Affects How They Connect With Each Other ”).

The online survey of 3,912 Black U.S. adults was conducted Oct. 4-17, 2021. Black U.S. adults include those who are single-race, non-Hispanic Black Americans; multiracial non-Hispanic Black Americans; and adults who indicate they are Black and Hispanic. The survey includes 1,025 Black adults on Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP) and 2,887 Black adults on Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel. Respondents on both panels are recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses.

Recruiting panelists by phone or mail ensures that nearly all U.S. Black adults have a chance of selection. This gives us confidence that any sample can represent the whole population (see our Methods 101 explainer on random sampling). Here are the questions used for the survey of Black adults, along with its responses and methodology .

The terms “Black Americans,” “Black people” and “Black adults” are used interchangeably throughout this report to refer to U.S. adults who self-identify as Black, either alone or in combination with other races or Hispanic identity.

Throughout this report, “Black, non-Hispanic” respondents are those who identify as single-race Black and say they have no Hispanic background. “Black Hispanic” respondents are those who identify as Black and say they have Hispanic background. We use the terms “Black Hispanic” and “Hispanic Black” interchangeably. “Multiracial” respondents are those who indicate two or more racial backgrounds (one of which is Black) and say they are not Hispanic.

Respondents were asked a question about how important being Black was to how they think about themselves. In this report, we use the term “being Black” when referencing responses to this question.

In this report, “immigrant” refers to people who were not U.S. citizens at birth – in other words, those born outside the U.S., Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories to parents who were not U.S. citizens. We use the terms “immigrant,” “born abroad” and “foreign-born” interchangeably.

Throughout this report, “Democrats and Democratic leaners” and just “Democrats” both refer to respondents who identify politically with the Democratic Party or who are independent or some other party but lean toward the Democratic Party. “Republicans and Republican leaners” and just “Republicans” both refer to respondents who identify politically with the Republican Party or are independent or some other party but lean toward the Republican Party.

Respondents were asked a question about their voter registration status. In this report, respondents are considered registered to vote if they self-report being absolutely certain they are registered at their current address. Respondents are considered not registered to vote if they report not being registered or express uncertainty about their registration.

To create the upper-, middle- and lower-income tiers, respondents’ 2020 family incomes were adjusted for differences in purchasing power by geographic region and household size. Respondents were then placed into income tiers: “Middle income” is defined as two-thirds to double the median annual income for the entire survey sample. “Lower income” falls below that range, and “upper income” lies above it. For more information about how the income tiers were created, read the methodology .

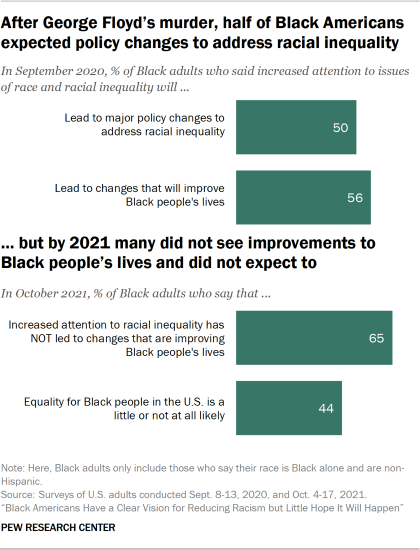

More than a year after the murder of George Floyd and the national protests, debate and political promises that ensued, 65% of Black Americans say the increased national attention on racial inequality has not led to changes that improved their lives. 1 And 44% say equality for Black people in the United States is not likely to be achieved, according to newly released findings from an October 2021 survey of Black Americans by Pew Research Center.

This is somewhat of a reversal in views from September 2020, when half of Black adults said the increased national focus on issues of race would lead to major policy changes to address racial inequality in the country and 56% expected changes that would make their lives better.

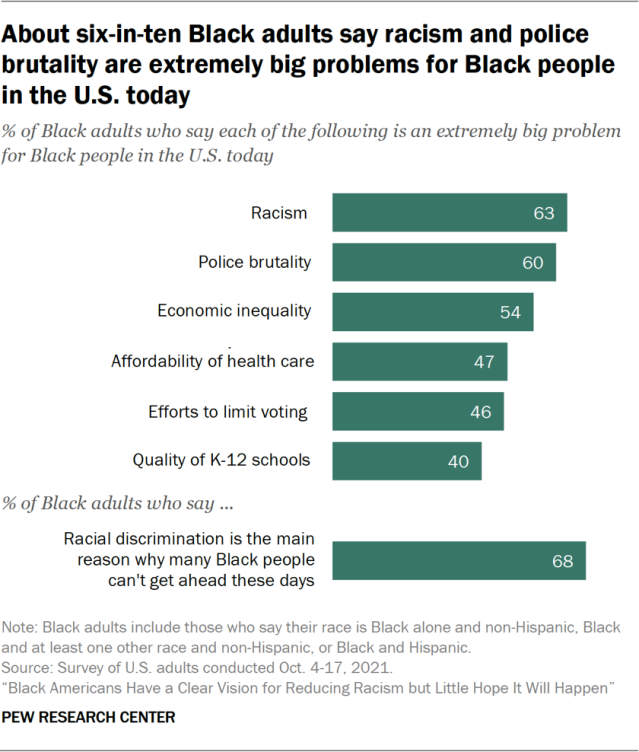

At the same time, many Black Americans are concerned about racial discrimination and its impact. Roughly eight-in-ten say they have personally experienced discrimination because of their race or ethnicity (79%), and most also say discrimination is the main reason many Black people cannot get ahead (68%).

Even so, Black Americans have a clear vision for how to achieve change when it comes to racial inequality. This includes support for significant reforms to or complete overhauls of several U.S. institutions to ensure fair treatment, particularly the criminal justice system; political engagement, primarily in the form of voting; support for Black businesses to advance Black communities; and reparations in the forms of educational, business and homeownership assistance. Yet alongside their assessments of inequality and ideas about progress exists pessimism about whether U.S. society and its institutions will change in ways that would reduce racism.

These findings emerge from an extensive Pew Research Center survey of 3,912 Black Americans conducted online Oct. 4-17, 2021. The survey explores how Black Americans assess their position in U.S. society and their ideas about social change. Overall, Black Americans are clear on what they think the problems are facing the country and how to remedy them. However, they are skeptical that meaningful changes will take place in their lifetime.

Black Americans see racism in our laws as a big problem and discrimination as a roadblock to progress

Black adults were asked in the survey to assess the current nature of racism in the United States and whether structural or individual sources of this racism are a bigger problem for Black people. About half of Black adults (52%) say racism in our laws is a bigger problem than racism by individual people, while four-in-ten (43%) say acts of racism committed by individual people is the bigger problem. Only 3% of Black adults say that Black people do not experience discrimination in the U.S. today.

In assessing the magnitude of problems that they face, the majority of Black Americans say racism (63%), police brutality (60%) and economic inequality (54%) are extremely or very big problems for Black people living in the U.S. Slightly smaller shares say the same about the affordability of health care (47%), limitations on voting (46%), and the quality of K-12 schools (40%).

Aside from their critiques of U.S. institutions, Black adults also feel the impact of racial inequality personally. Most Black adults say they occasionally or frequently experience unfair treatment because of their race or ethnicity (79%), and two-thirds (68%) cite racial discrimination as the main reason many Black people cannot get ahead today.

Black Americans’ views on reducing racial inequality

Black Americans are clear on the challenges they face because of racism. They are also clear on the solutions. These range from overhauls of policing practices and the criminal justice system to civic engagement and reparations to descendants of people enslaved in the United States.

Changing U.S. institutions such as policing, courts and prison systems

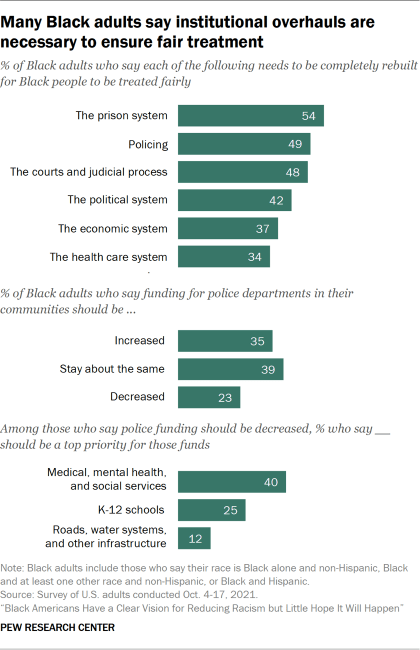

About nine-in-ten Black adults say multiple aspects of the criminal justice system need some kind of change (minor, major or a complete overhaul) to ensure fair treatment, with nearly all saying so about policing (95%), the courts and judicial process (95%), and the prison system (94%).

Roughly half of Black adults say policing (49%), the courts and judicial process (48%), and the prison system (54%) need to be completely rebuilt for Black people to be treated fairly. Smaller shares say the same about the political system (42%), the economic system (37%) and the health care system (34%), according to the October survey.

While Black Americans are in favor of significant changes to policing, most want spending on police departments in their communities to stay the same (39%) or increase (35%). A little more than one-in-five (23%) think spending on police departments in their area should be decreased.

Black adults who favor decreases in police spending are most likely to name medical, mental health and social services (40%) as the top priority for those reappropriated funds. Smaller shares say K-12 schools (25%), roads, water systems and other infrastructure (12%), and reducing taxes (13%) should be the top priority.

Voting and ‘buying Black’ viewed as important strategies for Black community advancement

Black Americans also have clear views on the types of political and civic engagement they believe will move Black communities forward. About six-in-ten Black adults say voting (63%) and supporting Black businesses or “buying Black” (58%) are extremely or very effective strategies for moving Black people toward equality in the U.S. Smaller though still significant shares say the same about volunteering with organizations dedicated to Black equality (48%), protesting (42%) and contacting elected officials (40%).

Black adults were also asked about the effectiveness of Black economic and political independence in moving them toward equality. About four-in-ten (39%) say Black ownership of all businesses in Black neighborhoods would be an extremely or very effective strategy for moving toward racial equality, while roughly three-in-ten (31%) say the same about establishing a national Black political party. And about a quarter of Black adults (27%) say having Black neighborhoods governed entirely by Black elected officials would be extremely or very effective in moving Black people toward equality.

Most Black Americans support repayment for slavery

Discussions about atonement for slavery predate the founding of the United States. As early as 1672 , Quaker abolitionists advocated for enslaved people to be paid for their labor once they were free. And in recent years, some U.S. cities and institutions have implemented reparations policies to do just that.

Most Black Americans say the legacy of slavery affects the position of Black people in the U.S. either a great deal (55%) or a fair amount (30%), according to the survey. And roughly three-quarters (77%) say descendants of people enslaved in the U.S. should be repaid in some way.

Black adults who say descendants of the enslaved should be repaid support doing so in different ways. About eight-in-ten say repayment in the forms of educational scholarships (80%), financial assistance for starting or improving a business (77%), and financial assistance for buying or remodeling a home (76%) would be extremely or very helpful. A slightly smaller share (69%) say cash payments would be extremely or very helpful forms of repayment for the descendants of enslaved people.

Where the responsibility for repayment lies is also clear for Black Americans. Among those who say the descendants of enslaved people should be repaid, 81% say the U.S. federal government should have all or most of the responsibility for repayment. About three-quarters (76%) say businesses and banks that profited from slavery should bear all or most of the responsibility for repayment. And roughly six-in-ten say the same about colleges and universities that benefited from slavery (63%) and descendants of families who engaged in the slave trade (60%).

Black Americans are skeptical change will happen

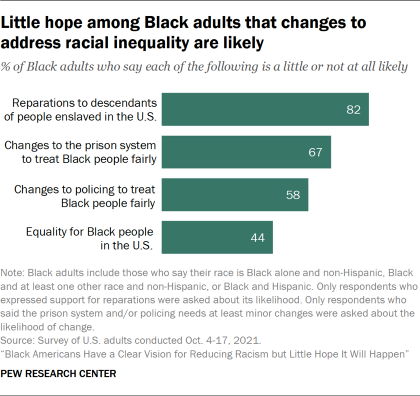

Even though Black Americans’ visions for social change are clear, very few expect them to be implemented. Overall, 44% of Black adults say equality for Black people in the U.S. is a little or not at all likely. A little over a third (38%) say it is somewhat likely and only 13% say it is extremely or very likely.

They also do not think specific institutions will change. Two-thirds of Black adults say changes to the prison system (67%) and the courts and judicial process (65%) that would ensure fair treatment for Black people are a little or not at all likely in their lifetime. About six-in-ten (58%) say the same about policing. Only about one-in-ten say changes to policing (13%), the courts and judicial process (12%), and the prison system (11%) are extremely or very likely.

This pessimism is not only about the criminal justice system. The majority of Black adults say the political (63%), economic (62%) and health care (51%) systems are also unlikely to change in their lifetime.

Black Americans’ vision for social change includes reparations. However, much like their pessimism about institutional change, very few think they will see reparations in their lifetime. Among Black adults who say the descendants of people enslaved in the U.S. should be repaid, 82% say reparations for slavery are unlikely to occur in their lifetime. About one-in-ten (11%) say repayment is somewhat likely, while only 7% say repayment is extremely or very likely to happen in their lifetime.

Black Democrats, Republicans differ on assessments of inequality and visions for social change

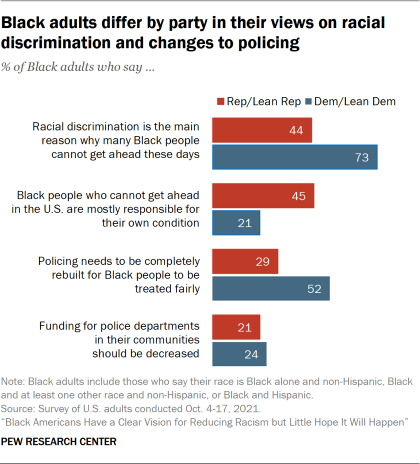

Party affiliation is one key point of difference among Black Americans in their assessments of racial inequality and their visions for social change. Black Republicans and Republican leaners are more likely than Black Democrats and Democratic leaners to focus on the acts of individuals. For example, when summarizing the nature of racism against Black people in the U.S., the majority of Black Republicans (59%) say racist acts committed by individual people is a bigger problem for Black people than racism in our laws. Black Democrats (41%) are less likely to hold this view.

Black Republicans (45%) are also more likely than Black Democrats (21%) to say that Black people who cannot get ahead in the U.S. are mostly responsible for their own condition. And while similar shares of Black Republicans (79%) and Democrats (80%) say they experience racial discrimination on a regular basis, Republicans (64%) are more likely than Democrats (36%) to say that most Black people who want to get ahead can make it if they are willing to work hard.

On the other hand, Black Democrats are more likely than Black Republicans to focus on the impact that racial inequality has on Black Americans. Seven-in-ten Black Democrats (73%) say racial discrimination is the main reason many Black people cannot get ahead in the U.S, while about four-in-ten Black Republicans (44%) say the same. And Black Democrats are more likely than Black Republicans to say racism (67% vs. 46%) and police brutality (65% vs. 44%) are extremely big problems for Black people today.

Black Democrats are also more critical of U.S. institutions than Black Republicans are. For example, Black Democrats are more likely than Black Republicans to say the prison system (57% vs. 35%), policing (52% vs. 29%) and the courts and judicial process (50% vs. 35%) should be completely rebuilt for Black people to be treated fairly.

While the share of Black Democrats who want to see large-scale changes to the criminal justice system exceeds that of Black Republicans, they share similar views on police funding. Four-in-ten each of Black Democrats and Black Republicans say funding for police departments in their communities should remain the same, while around a third of each partisan coalition (36% and 37%, respectively) says funding should increase. Only about one-in-four Black Democrats (24%) and one-in-five Black Republicans (21%) say funding for police departments in their communities should decrease.

Among the survey’s other findings:

Black adults differ by age in their views on political strategies. Black adults ages 65 and older (77%) are most likely to say voting is an extremely or very effective strategy for moving Black people toward equality. They are significantly more likely than Black adults ages 18 to 29 (48%) and 30 to 49 (60%) to say this. Black adults 65 and older (48%) are also more likely than those ages 30 to 49 (38%) and 50 to 64 (42%) to say protesting is an extremely or very effective strategy. Roughly four-in-ten Black adults ages 18 to 29 say this (44%).

Gender plays a role in how Black adults view policing. Though majorities of Black women (65%) and men (56%) say police brutality is an extremely big problem for Black people living in the U.S. today, Black women are more likely than Black men to hold this view. When it comes to criminal justice, Black women (56%) and men (51%) are about equally likely to share the view that the prison system should be completely rebuilt to ensure fair treatment of Black people. However, Black women (52%) are slightly more likely than Black men (45%) to say this about policing. On the matter of police funding, Black women (39%) are slightly more likely than Black men (31%) to say police funding in their communities should be increased. On the other hand, Black men are more likely than Black women to prefer that funding stay the same (44% vs. 36%). Smaller shares of both Black men (23%) and women (22%) would like to see police funding decreased.

Income impacts Black adults’ views on reparations. Roughly eight-in-ten Black adults with lower (78%), middle (77%) and upper incomes (79%) say the descendants of people enslaved in the U.S. should receive reparations. Among those who support reparations, Black adults with upper and middle incomes (both 84%) are more likely than those with lower incomes (75%) to say educational scholarships would be an extremely or very helpful form of repayment. However, of those who support reparations, Black adults with lower (72%) and middle incomes (68%) are more likely than those with higher incomes (57%) to say cash payments would be an extremely or very helpful form of repayment for slavery.

- Black adults in the September 2020 survey only include those who say their race is Black alone and are non-Hispanic. The same is true only for the questions of improvements to Black people’s lives and equality in the United States in the October 2021 survey. Throughout the rest of this report, Black adults include those who say their race is Black alone and non-Hispanic; those who say their race is Black and at least one other race and non-Hispanic; or Black and Hispanic, unless otherwise noted. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

Report Materials

Table of contents, race is central to identity for black americans and affects how they connect with each other, black americans’ views of and engagement with science, black catholics in america, facts about the u.s. black population, the growing diversity of black america, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Handout A: Background Essay: African Americans in the Gilded Age

Background Essay: African Americans in the Gilded Age

Directions: Read the essay and answer the review questions at the end.

In the late nineteenth century, the promise of emancipation and Reconstruction went largely unfulfilled and was even reversed in the lives of African Americans. Southern blacks suffered from horrific violence, political disfranchisement, economic discrimination, and legal segregation. Ironically, the new wave of racial discrimination that was introduced was part of an attempt to bring harmony between the races and order to American society.

Constitutional amendments were ratified during and after the war to protect the natural and civil rights of African Americans. The Thirteenth Amendment forever banned slavery from the United States, the Fourteenth Amendment protected black citizenship, and the Fifteenth Amendment granted the right to vote to African-American males. In addition, a Freedmen’s Bureau was established to help the economic condition of former slaves, and Congress passed the Civil Rights Act in 1875.

Roadblocks to Equality

Despite these legal protections, the economic condition of African Americans significantly worsened in the last few decades of the nineteenth century. Poor southern black farmers were generally forced into sharecropping whereby they borrowed money to plant a year’s crop, using the future crop as collateral on the loan. Often, they owed so much of the resulting crop that they fell into debt for the following year and eventually into a state of debt peonage. Since 90 percent of African Americans lived in the rural South, most were sharecroppers. The story was not much different as African Americans moved to southern and northern cities. Black women found work as domestic servants and men in urban factories, but they were usually in menial, low-paying jobs because white employers discriminated against African Americans in hiring. Black workers also faced a great deal of racism at the hands of labor unions which severely limited their ability to secure high-paying, skilled jobs. While the Knights of Labor and United Mine Workers were open to blacks, the largest skilled-worker union, the American Federation of Labor, curtailed black membership, thereby limiting them to menial labor.

African Americans throughout the country suffered from violence and intimidation. The most infamous examples of violence were brutal lynchings, or executions without due process, by angry white mobs. These travesties resulted in hangings, burnings, shootings, and mutilations for between 100 and 200 blacks—especially black men falsely accused of raping white women—annually. Race riots broke out in southern and northern cities from New Orleans and Atlanta to New York and Evansville, Indiana, causing dozens of deaths and property damage.

Although African Americans were elected to Congress and state legislatures during Reconstruction, and enjoyed the constitutional right to vote, black civil rights were systematically stripped away in a campaign of disfranchisement. One method was to charge a poll tax to vote, which precious few black sharecroppers could afford to pay. Another strategy was the literacy test which few former slaves could pass. Furthermore, the white clerks at courthouses had already decided that any black applicant would fail, regardless of his true reading ability. Since both of those devices at times excluded poor whites as well, grandfather clauses were introduced to exempt from the literacy test anyone whose father or grandfather had the right to vote before the Civil War. Moreover, the Supreme Court declared the 1875 Civil Rights Act guaranteeing equal access to public facilities and transportation to be unconstitutional in the Civil Rights Cases (1883) because the law regulated the private discriminatory conduct of individuals rather than government discrimination.

Segregation

One of the most pervasive and visible signs of racism was the rise of informal and legal segregation, or separation of the races. In a wholesale violation of liberty and equality, southern state legislatures passed “Jim Crow” segregation laws that denied African Americans equal access to public facilities such as hotels, restaurants, parks, and swimming pools. Southern schools and public transportation had vastly inferior “separate but equal” facilities that left the black minority subject to unjust majority rule. Housing covenants and other devices kept blacks in separate neighborhoods from whites. African Americans in the North also suffered informal residential segregation and economic discrimination in jobs.

In one of its more infamous decisions, the Supreme Court ruled that segregation statutes were legal in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). In Plessy, the Court decided that “separate, but equal” public facilities did not violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment or imply the inferiority of African Americans. Justice John Marshall Harlan was one of the two dissenters who wrote, “Our constitution is colorblind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law.”

Progressive and Race Relations

One of the great ironies of the series of reforms instituted in the early twentieth century known as the Progressive Era was that segregation and racism were deeply enshrined in the movement. Progressives were a group of reformers who believed that the industrialized, urbanized United States of the nineteenth century had outgrown its eighteenth-century Constitution. That Constitution did not give government, especially the federal government, enough power to deal with unprecedented problems. Many Progressives embraced Social Darwinism and eugenics which was part of the most advanced science and social science taught in universities and scientific circles. Social Darwinism ranked various groups, which its proponents considered “races,” according to certain characteristics and labelled Anglo-Saxon and Teutonic peoples as superior and Southeastern Europeans, Jews, Asians, Hispanics, and Africans as inferior races. Therefore, there was a supposed scientific basis for segregation as the “higher” races ruled the “lower.” Moreover, Progressives generally endorsed segregation as a means of achieving their central goal of social order and harmony between the races. There were notable exceptions, such as Jane Addams, black Progressives such as W.E.B. DuBois, and the Progressives of both races who founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), but Progressive ideology contributed to the growth of segregation.

Progressive Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson generally supported the segregationist order. While Roosevelt courageously invited African-American leader Booker T. Washington to dinner in the White House and condemned lynching, he discharged 170 black soldiers because of a race riot in Brownsville, Texas in 1906. Wilson had perhaps a worse record on civil rights as his administration fired many black federal employees and segregated federal departments.

Black Leadership

Several black leaders advanced the cause of black civil rights and helped organize African Americans to defend their interests through self help. The highly-educated journalist, Ida B. Wells, launched a crusade against lynching by exposing the savage practice. She also challenged segregation by refusing to change her seat on a train because it was in an area reserved for white women. Other African Americans unsuccessfully boycotted segregated streetcars in urban areas but utilized a method that would prove successful in the mid-twentieth century.

A debate took shape between two African-American leaders, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois. Washington was a former slave who founded the Tuskegee Institute for blacks in the 1880s and wrote Up from Slavery. He advocated that African Americans achieve racial equality slowly by patience and accommodation. Washington thought that blacks should be trained in industrial education and demonstrate the character virtues of hard work, thrift, and self-respect. They would therefore prove that they deserved equal rights and equal opportunity for social mobility. At the 1895 Atlanta Exposition, Washington delivered an address that posited, “In the long run it is the race or individual that exercises the most patience, forbearance, and self-control in the midst of trying conditions that wins…the respect of the world.”

DuBois, on the other hand, was a Harvard and Berlin-educated intellectual who believed that African Americans should win equality through a liberal arts education and fighting for political and civil equality. He wrote the Souls of Black Folk and laid out a vision whereby the “talented tenth” among African Americans would receive an excellent education and become the teachers and other professionals who would uplift fellow members of their race. He and other black leaders organized the Niagara Movement that fought segregation, lynching, and disfranchisement. In 1909 the movement’s leaders founded the NAACP, which fought for black equality and initiated a decades-long legal struggle to end segregation. DuBois edited its journal named The Crisis and wrote about issues affecting African Americans. He had the simple wish to “make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of opportunity closed roughly in his face.”

Wartime Changes

American participation in the Spanish-American War and World War I initiated a dramatic change in the lives of African Americans and in the demography of American society. In both wars, black soldiers were relegated to segregated units and generally assigned to menial jobs rather than front-line combat. However, black soldiers had opportunities to fight in the charges against the Spanish in Cuba and against the Germans in the trenches of France. They demonstrated that they were just as courageous as white men even as they fought for a country that excluded them from its democracy. Moreover, travel to the North and overseas showed thousands of African Americans the possibility of freedom and equality that would be reinforced in World War II while fighting tyranny abroad.

Wartime America witnessed rapid change in the lives of African Americans especially in the rural South. Hundreds of thousands left southern farms to migrate to cities in the South such as Birmingham or Atlanta, or to northern cities in a mass movement called the Great Migration. This internal migration greatly increased the number of African Americans living in American cities. As a result, tensions grew with whites over jobs and housing that led to deadly race riots during and immediately after the war. However, a thriving black culture in the North also resulted in the Harlem Renaissance and the celebration of black artists.

The Great Migration eventually led to over six million African Americans following these migration patterns and laying the foundation for the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-twentieth century. Blacks resisted segregation when it was instituted and continued to organize to challenge its threat to liberty and equality in America.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- What constitutional protections did the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments give African Americans?

- What economic conditions did African Americans face in the south and north in the late nineteenth century?

- What kinds of violence did African Americans suffer during the late nineteenth century?

- Despite the amendments to the Constitution protecting the rights of African Americans, what discriminatory devices systematically took away these rights?

- What was the ruling in the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) case? Did the case result in the advance or reversal of the rights of African Americans? Explain your answer.

- Did African Americans make gains or suffer setbacks to their rights during the Progressive Era? Explain your answer.

- Compare and contrast the means and goals of achieving black equality for Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois.

- How did World War I and the Great Migration change the lives of African Americans?

Racial Discrimination and Justice in Education Essay

The impact of racism in schools and on the mental health of students.

Funding is one of the main factors that ensure racial segregation and exacerbation of the plight of the black population. Being initially in a more disastrous economic situation, racial minority populations fall into a vicious circle. Low-funded schools in poor areas have low academic ratings, which further contributes to the reduction of the material base. Due to their poor academic performance and the need to earn a living, many minorities are deprived of the opportunity to receive prestigious higher education. They are left with low-skilled jobs, which makes it impossible for their children to go to private school or move to a prestigious area with well-funded public schools. In institutions with little funding, unfortunately, manifestations of racism still prevail.

A significant factor in systemic racism in modern schools is the theory of colorblindness as the prevailing ideology in schools and pedagogical universities. The total avoidance of racial topics in schools has led to a complete absence of material related to the culture of racial minorities in the curricula. An example is the complaint of the parents of one of the black students that, during the passage of civilizations, the Greeks, Romans, and Incas were discussed in the lessons, but nothing was said about Africa. However, there were a few African American students in the class (Yi et al., 2022). The white director justified herself by saying that this was the curriculum and that it was not customary at school to divide people by skin color. In response, the student’s mother stated that children have eyes, and they see everything. And she would like them to see that we had a strong and fruitful culture. This state of affairs is justified by the proponents of assimilationism and American patriotism, built mainly around the honoring of the merits of white settlers and the founding fathers.

Meanwhile, the works of many researchers provide evidence that a high level of colorblindness among students correlates with greater racial intolerance. One study on race relations was conducted among young “millennials”. As a result, thousands of reports were recorded of openly racist statements and actions of white people from the field of view of these students (Plaut, et al., 2018). Another study on colorblindness found that white students who avoid mentioning racial issues were less friendly on assignments with black partners. This could be because they have less eye contact.