164 Native American Research Topics

Looking for interesting Native American research topics? Here, we will explore the vibrant cultures and contributions of Indigenous peoples in North America. Choose a Native American essay topic to delve into the profound impact of colonization on Native American societies, their resilience, artistic expressions, and challenges.

💥 TOP 7 Native American Research Topics

🏆 best native american essay topics, 📍 native argumentative essay topics, 👍 more native american topics to write about, 🎓 interesting native american research questions, ✍️ native american essay topics for college, ❓ more native american essay topics.

- Values in Native American Oral Literature

- Horse Riding Stereotype Among the Native Americans

- Alaska Natives Diet: Traditional Food Habits and Adaptation of American Foodstuffs

- Comparison of Native American and African Religions

- Racial and Cultural Discrimination of Native Americans

- Native American Boarding Schools

- The Navajo Indians: Native American Studies

- Native American’s Oregon Recipe Native American recipes are techniques used by early American tribes to prepare foods rich in nutrition. In this case, the main discussion will focus on the Oregon native recipe.

- Native American Poems’ Comparative Analysis This paper presents a comparative analysis of three poems. They are “Absence” and “To the Pine Tree” by Schoolcraft, and “The Indian Corn Planter” by Johnson.

- European Trade Goods for Native Americans The use of European trade goods changed Native Americans’ lives while providing them with more opportunities to succeed in supporting and protecting their families.

- Institutional Racism Against Native Americans: The Killers of the Flower Moon David Grann published The Killers of the Flower Moon about the murders in Oklahoma in the 1920s and contributed to the creation of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

- Native American Families in the United States This paper gives an in-depth analysis of the Native American society alongside other minority groups in terms of the human capital, time of arrival and demographic characteristics.

- Native American and African Religions According to Toropov and Buckles, within the Native American spirituality, all processes whether human or non human (spiritual), are linked.

- Native American Myths and American Literature The most attractive works for attention in the canon of American literature were those that seemed to illuminate the entire diversity of American culture.

- Cultural Competence Concerning Native Americans Native American communities have religious beliefs, community and family factors, and secondary determinants that affect cultural competence.

- Native American Renaissance in Poems In the 1950s, the culture of Native Americans experienced a phenomenon known as the Native American Renaissance.

- Social Work With Native American Population The Native American or Indigenous population has historically been challenged by severe oppression ever since the European population’s first arrival in the Americas.

- Native American Music of the Cherokee Indian Tribe Several scholars have studied and documented the rich music history and the place that music occupies in the life of the Cherokees.

- Europeans vs Native Americans: Why the Conflict Was Inevitable? As soon as Indians began refusing to do what colonizers asked of them, the latter started taking brutal measures.

- Native American Culture Before and After Colonization This paper discusses the culture of Native Americans and how this population managed to preserve and develop its cultural identity despite it being on the brink of extinction.

- Psychoeducation Group for Native Americans with Trauma The purpose of the psychoeducational group is to assist Native American individuals with trauma in the provision of high-quality therapy.

- Who Discovered America: Native Americans, Vikings and Columbus At the end of the 15th century, the Spanish navigator Christopher Columbus, with his expedition, reached North America’s shores, mistakenly believing that he had arrived in India.

- Native American Music: Cherokee Indian Tribe Different tribes had different kinds of music for different purposes, but they were all brought together by two characteristics; togetherness and drums.

- Native Americans: Annotated Bibliography The annotated bibliography of the articles related to the studies about modern Native Americans and their relations with non-Indians.

- Native Americans: Impact of European Colonization Depriving Native Americans of their land, culture, and freedom, European colonialism virtually annihilated their community, agency, and, ultimately, their lives.

- Relationships Between the European Settlers and the Native Americans This essay aims to examine the places of worship as a sphere of encounter for Europeans and the Indigenous people of America.

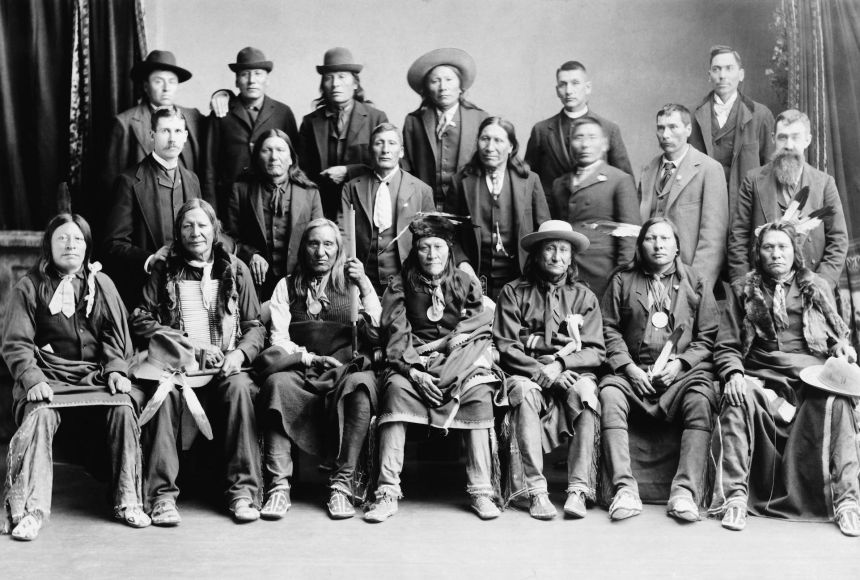

- Photography Impacts on Cultural Identity of Native Americans in America The photos of Native Americans often turn out to be disadvantageous to the appearance of the indigenous Americans, especially in this era of photography.

- Native American Women and Parenting The purpose of this research study is to review the plight of Native American mothers as well as other marginalized women populations.

- European vs. Native American Societies When the Europeans started to arrive in the New World, they discovered a society of Native Americans, or Indians, which was fundamentally different from their own.

- The Impact of European Colonization on Native American Communities.

- The Role of Native American Sovereignty in Contemporary Society.

- Cultural Appropriation and Its Effects on Native American Traditions.

- The Repatriation of Native American Artifacts: Ethical Considerations.

- Native American Mascots: Promoting Stereotypes or Cultural Appreciation?

- The Ongoing Struggle for Land Rights and Resource Management.

- The Importance of Preserving Native American Languages and Oral Traditions.

- Tribal Gaming and Economic Development: Balancing Progress and Tradition.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Challenges in Native American Communities.

- Environmental Activism: Native American Perspectives on Conservation.

- The Impact of Boarding Schools on Native American Identity and Culture.

- Indigenous Rights and the Fight Against Pipeline Construction.

- The Role of Native American Women in Traditional and Modern Societies.

- Treaty Rights and Their Significance in Upholding Sovereignty.

- Reproductive Health and Healthcare Disparities in Native American Communities.

- Addressing Food Insecurity and Nutrition Challenges in Indigenous Populations.

- The Effects of Historical Trauma on Native American Mental Health.

- Tribal Justice Systems: Strengthening Cultural Practices and Community Accountability.

- Native American Education: Bridging the Achievement Gap.

- Sacred Sites and Religious Freedom: Balancing Cultural Preservation and Development.

- The Role of Native American Veterans in U.S. Military History.

- Native American Activism: Strategies for Advocating Indigenous Rights.

- The Role of Native American Literature in Resisting Assimilation.

- The Impact of Climate Change on Native American Communities.

- The Erasure of Native American Women from Missing and Murdered Indigenous People (MMIP) Discussions.

- Access to Healthcare and Health Disparities in Tribal Lands.

- Native American Identity and Racial Identity in the United States.

- The Impact of Federal Policies on Native American Reservations.

- The Role of Native American Languages in Educational Curriculum.

- Addressing Substance Abuse in Native American Youth: Prevention and Treatment Strategies.

- The Natchez: Native American People’s History The Natchez is a Native American ethnic group that initially lived in the Natchez Bluffs area in the Lower Mississippi Valley, which is the present-day town of Natchez.

- Native American and Cherokee Heritage Populations The aim of this research paper is to present the main characteristics of such cultural groups as Native Americans and Cherokee Heritage populations.

- The Rite of Sun Dance: Ancient Native American Practice The rite of the Sundance is an ancient Native American practice by the Lakota Sioux. It is a ceremonial dance done during summer at a Sun Dance gathering.

- Native American, European, and Black Women in North America The position of Native American, European, and Black women has changed a lot, giving them more opportunities, but also retaining certain limitations.

- Influence of Spaniards on Native Americans After considering the Spanish actions, one can understand how they changed the lives of the Indians. Spanish ships were anchored at the port of Monterey’s Bay to control the shore.

- The Relationship Between Native Americans and White Settlers The relationship between Native Americans and white settlers, as well as the perception of it, were more complex than often portrayed and should be explored.

- The Representation of Native Americans in Films The development of the representation of Native Americans in films has been uneven, with early movies featuring the population quite amply, while making obvious mistakes.

- New Perspective on the Enslavement of Native Americans The work shows a new perspective on the complex topic of Indian enslavement in the United States, which was overlooked before.

- Historical Trauma in Native Americans and African Americans Comparing and contrasting the historical trauma of Native Americans and African Americans provides an opportunity to see similarities in their life experiences.

- European-Native American Encounter After Columbus After Columbus, due to the forced ways of life, the Natives had to change their thinking methods to make possible fruitful interactions with the Europeans.

- Native American Tribes Before and After European Influence The paper examines why there were so many tribes, the development of the Native American cultures, the role of the environment, and the impact of Europeans.

- Native Americans: The Value of Environmental and Cultural History The history of Native Americans involves the environment in which they lived before being colonized. Native Americans have been silenced and deprived of their environment.

- Indian Boarding Schools and Native Americans Genocide The primary aim of the schools was to provide ample educational opportunities for Indians. In fact, children were prone to bullying and cultural stigmatization.

- British Colonists Attitude Toward Native Americans The ways British colonists regarded Native Americans, and black apparently was not identical, which determined the unequal positions of those in the newly created society.

- Native Americans in Schools: Effects of Racism Despite the improvement in educational policies, racism against Native Americans is still a problem in the education sector.

- Vine Deloria on Native American Activism When describing Indian Activism, Deloria emphasizes the concept of restoring sacred lands as one of the central ideas of the activist movement.

- The Native American Pipe Ceremony Then and Now The Native American Pipe Ceremony is the heart of the spiritual and cultural life of the native people of North America, particularly the Sioux or Lakota.

- Native American’s Trail Trees Markers A trail marker tree is a landmark used by Native Americans to tell directions they should follow when traveling.

- Native North American Art and the Indigenous Cultures This paper intends to compare the art pieces and cultural practices of the two regions of North America to identify existing similarities and differences.

- The Colonization of America as a Native American Genocide This paper argues that the colonization of America can be classified as the genocide of Native Americans as it features the goal of destroying the group.

- Aspects of Native American Culture With his writing, Franklin explores some aspects of the Native American culture, such as the transition of knowledge between Indians, and their attitude towards the White people.

- What Prevents Blacks, Latinos, and Native Americans From Banding Together With the inability of Asians, Blacks, Latinos, and Native Americans to access upward mobility, banding together to fight white supremacy has become an unrealized goal.

- Native American Tribes’ Customs and Politics The west region, north region, and northwest coast region are all part of the Native American culture. These are among the regions that the indigenous people of the United States.

- “Yellow Woman and a Beauty of the Spirit”: Old Tales in the Lives of Native Americans The current essay intends to examine how “Yellow Woman and a Beauty of the Spirit” reveals the role of old tales in the lives of Native American tribes in Yellow Woman.

- Religion and Europeans’ Attitude to Native Americans The paper examines how religion affected the attitude of the Europeans towards Native Americans in their initial contact and what factors contributed to this approach.

- Chief Joseph as a Famous Native American Chief Joseph was a leader in the 19th century, of a tribe called Nez Percé, he converted to Christianity after he failed in negotiations with the current Americans.

- Native Americans Issues in the US Even though Indian Americans are the indigenous population of this territory, they have experienced much discrimination since the Europeans came to North America.

- Healthcare Provider and Faith Diversity: Native American Spirituality, Buddhism, and Sikhism This paper outlines an explicit view on the following diverse faiths in regard to healthcare provision: Native American spirituality, Buddhism, and Sikhism.

- Healthcare System for Native and African Americans This paper discusses historical events contributing to mistrust of the health care system and steps to reduce health disparities among Native Americans and African Americans.

- Indian Land Rights Native American

- Native American Casinos and Their Influence on the Community

- Kennewick Man and the Native American Graves Protection

- Native American Boarding Schools of the Nineteenth Century

- Historical Challenges That Native American Women Have Faced

- Native American Healing and Medicinal Practices

- Integrating Holistic Modalities Into Native American Alcohol Treatment

- Ethically Handling and Reburying Human Remains of Indigenous Native American People

- Gender Roles and Sexuality in the Cultural Beliefs of the Native American Tribes

- Holocaust vs. Native American Genocide

- American Colonialism Still Influences Native American Identity

- Native American Community: Problems With Substance Abuse

- Jainism, Taoism, and the Native American Lakhota Beliefs

- European Misperceptions and Stereotypes: Racism in Native American Society

- Important Native American Historical Dates

- Cleansing and Forced Relocation of Native American Nations

- Manifest Destiny and the Genocide of the Native American Indian

- Ecological World View and Native American Uniformity

- Buddhist Native American Religions

- Native American Culture and Health Care

- The Lived Experiences of Native American Women Parenting on and off Reservations The study will examine the experiences of Native American women living on and off reservations from a qualitative viewpoint.

- The Problem of Native Americans’ Existence Susan Power raises the problem of Native Americans’ existence in a modern world and their communication with the dominant society

- The Role of the Natives in the American Revolution This essay will provide a short account of the natives in the American Revolution and explain their reasons for siding with either party.

- The Land Conflict Between White Settlers and Native Americans This paper aims to examine the background of land conflict between white settlers and native Americans, as well as offer alternative ways of its resolution.

- The Discovery of America: Effects on Native Americans The discovery of the New World stopped the independent development of native Americans and laid the foundation for their colonial dependence.

- The U.S. Treatment of Native Americans The topic of the U.S. attitude toward Native Americans is essential to discuss. Three examples of harmful attitudes will be provided in this paper.

- Education for Native Americans: Difficulties This study focuses on the difficulties that Native American students experience in mastering educational programs related to information technology and computer science.

- Native Americans in the United States: Literature Review The paper reviews literature works about the native Americans: “What you Pawn I Will Redeem” by S. Alexie, “The Third and Final Continent” by J. Lahiri, “The Shawl” by L. Erdrich.

- The Art of Native North America The article analyzes Native American art in terms of its diversity and any general trends that can be found in it.

- Oban on Native American Indian Culture and Values The bear has always been part of Native American Indian culture and mythology, throughout the story, the traditional beliefs of Indians about bears are clearly articulated.

- Native American Studies: “Fool’s Crow” by Welch “Fool’s Crow” by James Welch is a remarkable book in the sphere of Native American literature. It is a masterful evocation of the Native American lifestyle and skillful reporting.

- Native-American Studies: Quapaw Indians This essay will discuss the culture of Quapaw Indians, tracing the history of the Quapaw Indians, their location, economic activities, and lifestyle.

- The Native American Indians The Native American Indians experienced the process of colonization performed by the English, French, and Spain colonizers.

- Freedom From Beliefs Native Americans This essay is valuable to the oppressed since through this, the writer gives them courage to face the struggle.

- Popular Culture: Native American Communities BBC and Reuters, the Times, and the Look portray that low-class location prevents many Native Americans to obtain social respect and opportunities available for the white majority.

- Native Americans and Using of Peyote Issue Peyote or mescaline is a hallucinogen derived from a cactus. A group of Native Americans use this regularly as part of their religious ceremonies.

- Native Americans History: The Other Trail of Tears The given work tells us about the native Americans, the history of their lives, problems, and restrictions they were facing.

- Native Americans and Navajo Heritage and Health Beliefs This paper demonstrates a compare and contrast analysis of common characteristics and distinguishing traits between Native American and Navajo heritage.

- Women and Natives in Colonial America During the Colonial era of world history, Europeans explored other continents looking for new land, valuable resources, and trade opportunities.

- Indian Boarding Schools’ Impact on Native Americans Indian boarding schools represented the institutions that forcibly put Native American children and teenagers in educational settings.

- European Exploration and Effects on Native Americans After the end of the fourteenth century, many European world powers began to explore and discover new regions.

- Native Americans’ History Before and After 1492 Native Americans inhabited the Americas for thousands of years before the arrival of Columbus and other European explorers and settlers.

- Native Americans and Apache Heritage This paper contains presentation about Native Americans as cultural group and Apache Heritage as socio-cultural group using scientific literature, Internet resources, and other sources.

- Native Americans and Navajo Heritage This paper contains presentation about Native Americans as cultural group and Navajo Heritage as socio-cultural group using scientific literature, Internet resources, and other sources.

- Heroes in Native American Legend and German Tale Folk literature is a concentration of wisdom and moral values. Fairy tales open the world where good confronts evil, and good always wins.

- Native American Indians: Concepts, Theories and Research Complexities in the interaction of Native Americans and settlers from Europe in the 15th century and early 16th century led to the establishment of boundaries between the natives and settlers.

- Native Americans and Nursing Care Strategies The purpose of this discussion is to describe demographic and cultural characteristics of Native Americans and present nursing strategies of providing culturally competent care.

- Native Americans: White Mountain Apache People To reveal a cultural landscape of White Mountain Apache people as well as their attitudes towards their lives, it is essential to pinpoint some core definitions used in the reading.

- Culturally Competent Healthcare Native Americans Culturally competent healthcare is the right mind-set to have in order to deliver cost-efficient service to members of the Native American population.

- Native Americans’ Mental Health The aim of this paper is to understand what healthcare needs with regard to mental health Native Americans might have, to reduce the rate of incidents related to mental health issues.

- European-Native American Relations The exploration in Americas allowed the development of cultural contacts and cultural exchanges among representatives of different societies.

- How Did the Environment Affect the Native American Indians?

- Should Native American Tribes Be Allowed to Use Peyote?

- How Did the Native American Removal Compare to the Holocaust?

- Do Native Americans Get Social Security?

- What Made Native American Peoples Vulnerable to Conquest by European Adventurers?

- How Did Manifest Destiny Affect Native American Culture?

- What Do Native American Arts Look Like?

- How Does Native American Mascot Controversy Affect U.S. Reputation?

- What Was Columbus’ Factor in Native American Depopulation?

- How Is Native American Philosophy Unique From Eurocentric?

- What Was Native American Society Like Before European Contact?

- How Were the Native American Indians Driven Out From Their Land?

- When Did the Native American Indians First Meet the European Settlers?

- What Does Sovereignty Do for Native Americans?

- How Sovereign Are Native American Nations Today?

- What Benefits Does the US Government Give to Native Americans?

- When Did Native Americans Lose Their Sovereignty?

- Can Native American Tribes Protect Their Land if They Are Not Recognized by the Federal Government?

- Which President Removed Native Americans From Their Lands?

- Do Native Americans Get Anything From the Government?

- Why Are Some Native American Tribes Not Federally Recognized?

- Do Native Americans Have Sovereign Immunity?

- How Did Native American Society Change After European Contact?

- Are Native Americans Protected by Law?

- Do Native Americans Pay More Taxes?

Cite this post

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, July 14). 164 Native American Research Topics. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/native-american-essay-topics/

"164 Native American Research Topics." StudyCorgi , 14 July 2022, studycorgi.com/ideas/native-american-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) '164 Native American Research Topics'. 14 July.

1. StudyCorgi . "164 Native American Research Topics." July 14, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/native-american-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "164 Native American Research Topics." July 14, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/native-american-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "164 Native American Research Topics." July 14, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/native-american-essay-topics/.

These essay examples and topics on Native American were carefully selected by the StudyCorgi editorial team. They meet our highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, and fact accuracy. Please ensure you properly reference the materials if you’re using them to write your assignment.

This essay topic collection was updated on January 21, 2024 .

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Native American Cultures

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 16, 2023 | Original: December 4, 2009

Many thousands of years before Christopher Columbus ’ ships landed in the Bahamas , a different group of people discovered America: the nomadic ancestors of modern Native Americans who hiked over a “land bridge” from Asia to what is now Alaska more than 12,000 years ago.

In fact, by the time European adventurers arrived in the 15th century, scholars estimate that more than 50 million people were already living in the Americas. Of these, some 10 million lived in the area that would become the United States. As time passed, these migrants and their descendants pushed south and east, adapting as they went.

In order to keep track of these diverse groups, anthropologists and geographers have divided them into “culture areas,” or rough groupings of contiguous peoples who shared similar habitats and characteristics. Most scholars break North America—excluding present-day Mexico—into 10 separate culture areas: the Arctic, the Subarctic, the Northeast, the Southeast, the Plains, the Southwest, the Great Basin, California, the Northwest Coast and the Plateau.

The Arctic culture area, a cold, flat, treeless region (actually a frozen desert) near the Arctic Circle in present-day Alaska , Canada and Greenland, was home to the Inuit and the Aleut. Both groups spoke, and continue to speak, dialects descended from what scholars call the Eskimo-Aleut language family.

Because it is such an inhospitable landscape, the Arctic’s population was comparatively small and scattered. Some of its peoples, especially the Inuit in the northern part of the region, were nomads, following seals, polar bears and other game as they migrated across the tundra. In the southern part of the region, the Aleut were a bit more settled, living in small fishing villages along the shore.

Did you know? According to the U.S. Census Bureau, there are about 4.5 million Native Americans and Alaska Natives in the United States today. That’s about 1.5 percent of the population.

The Inuit and Aleut had a great deal in common. Many lived in dome-shaped houses made of sod or timber (or, in the North, ice blocks). They used seal and otter skins to make warm, weatherproof clothing, aerodynamic dogsleds and long, open fishing boats (kayaks in Inuit; baidarkas in Aleut).

By the time the United States purchased Alaska in 1867, decades of oppression and exposure to European diseases had taken their toll: The native population had dropped to just 2,500; the descendants of these survivors still make their homes in the area today.

The Subarctic

The Subarctic culture area, mostly composed of swampy, piney forests (taiga) and waterlogged tundra, stretched across much of inland Alaska and Canada. Scholars have divided the region’s people into two language groups: the Athabaskan speakers at its western end, among them the Tsattine (Beaver), Gwich’in (or Kuchin) and the Deg Xinag (formerly—and pejoratively—known as the Ingalik), and the Algonquian speakers at its eastern end, including the Cree, the Ojibwa and the Naskapi.

In the Subarctic, travel was difficult—toboggans, snowshoes and lightweight canoes were the primary means of transportation—and population was sparse. In general, the peoples of the Subarctic did not form large permanent settlements; instead, small family groups stuck together as they traipsed after herds of caribou. They lived in small, easy-to-move tents and lean-tos, and when it grew too cold to hunt they hunkered into underground dugouts.

The growth of the fur trade in the 17th and 18th centuries disrupted the Subarctic way of life—now, instead of hunting and gathering for subsistence, the Indians focused on supplying pelts to the European traders—and eventually led to the displacement and extermination of many of the region’s native communities.

The Northeast

The Northeast culture area, one of the first to have sustained contact with Europeans, stretched from present-day Canada’s Atlantic coast to North Carolina and inland to the Mississippi River valley. Its inhabitants were members of two main groups: Iroquoian speakers (these included the Cayuga, Oneida, Erie, Onondaga, Seneca and Tuscarora), most of whom lived along inland rivers and lakes in fortified, politically stable villages, and the more numerous Algonquian speakers (these included the Pequot, Fox, Shawnee, Wampanoag, Delaware and Menominee) who lived in small farming and fishing villages along the ocean. There, they grew crops like corn, beans and vegetables.

Life in the Northeast culture area was already fraught with conflict—the Iroquoian groups tended to be rather aggressive and warlike, and bands and villages outside of their allied confederacies were never safe from their raids—and it grew more complicated when European colonizers arrived. Colonial wars repeatedly forced the region’s Indigenous people to take sides, pitting the Iroquois groups against their Algonquian neighbors. Meanwhile, as white settlement pressed westward, it eventually displaced both sets of Indigenous people from their lands.

The Southeast

The Southeast culture area, north of the Gulf of Mexico and south of the Northeast, was a humid, fertile agricultural region. Many of its natives were expert farmers—they grew staple crops like maize, beans, squash, tobacco and sunflower—who organized their lives around small ceremonial and market villages known as hamlets. Perhaps the most familiar of the Southeastern Indigenous peoples are the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole, sometimes called the Five Civilized Tribes, some of whom spoke a variant of the Muskogean language.

By the time the U.S. had won its independence from Britain, the Southeast culture area had already lost many of its native people to disease and displacement. In 1830, the federal Indian Removal Act compelled the relocation of what remained of the Five Civilized Tribes so that white settlers could have their land. Between 1830 and 1838, federal officials forced nearly 100,000 Indigenous people out of the southern states and into “Indian Territory” (later Oklahoma) west of the Mississippi. The Cherokee called this frequently deadly trek the Trail of Tears .

The Plains culture area comprises the vast prairie region between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains, from present-day Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. Before the arrival of European traders and explorers, its inhabitants—speakers of Siouan, Algonquian, Caddoan, Uto-Aztecan and Athabaskan languages—were relatively settled hunters and farmers. After European contact, and especially after Spanish colonists brought horses to the region in the 18th century, the peoples of the Great Plains became much more nomadic.

Groups like the Crow, Blackfeet, Cheyenne, Comanche and Arapaho used horses to pursue great herds of buffalo across the prairie. The most common dwelling for these hunters was the cone-shaped teepee, a bison-skin tent that could be folded up and carried anywhere. Plains Indians are also known for their elaborately feathered war bonnets.

As white traders and settlers moved west across the Plains region, they brought many damaging things with them: commercial goods, like knives and kettles, which Indigenous people came to depend on; guns; and disease. By the end of the 19th century, white sport hunters had nearly exterminated the area’s buffalo herds. With settlers encroaching on their lands and no way to make money, the Plains natives were forced onto government reservations.

The Southwest

The peoples of the Southwest culture area, a huge desert region in present-day Arizona and New Mexico (along with parts of Colorado, Utah, Texas and Mexico) developed two distinct ways of life.

Sedentary farmers such as the Hopi, the Zuni, the Yaqui and the Yuma grew crops like corn, beans and squash. Many lived in permanent settlements, known as pueblos, built of stone and adobe. These pueblos featured great multistory dwellings that resembled apartment houses. At their centers, many of these villages also had large ceremonial pit houses, or kivas.

Other Southwestern peoples, such as the Navajo and the Apache, were more nomadic. They survived by hunting, gathering and raiding their more established neighbors for their crops. Because these groups were always on the move, their homes were much less permanent than the pueblos. For instance, the Navajo fashioned their iconic eastward-facing round houses, known as hogans, out of materials like mud and bark.

By the time the southwestern territories became a part of the United States after the Mexican War, many of the region’s native people had already been killed. (Spanish colonists and missionaries had enslaved many of the Pueblo Indians, for example, working them to death on vast Spanish ranches known as encomiendas.) During the second half of the 19th century, the federal government resettled most of the region’s remaining natives onto reservations.

The Great Basin

The Great Basin culture area, an expansive bowl formed by the Rocky Mountains to the east, the Sierra Nevadas to the west, the Columbia Plateau to the north, and the Colorado Plateau to the south, was a barren wasteland of deserts, salt flats and brackish lakes. Its people, most of whom spoke Shoshonean or Uto-Aztecan dialects (the Bannock, Paiute and Ute, for example), foraged for roots, seeds and nuts and hunted snakes, lizards and small mammals. Because they were always on the move, they lived in compact, easy-to-build wikiups made of willow poles or saplings, leaves and brush. Their settlements and social groups were impermanent, and communal leadership (what little there was) was informal.

After European contact, some Great Basin groups got horses and formed equestrian hunting and raiding bands that were similar to the ones we associate with the Great Plains natives. After white prospectors discovered gold and silver in the region in the mid-19th century, most of the Great Basin’s people lost their land and, frequently, their lives.

Before European contact, the temperate California area had more people than any other North American landscape at the time, with approximately 300,000 people in the mid-16th century. It's estimated that 100 different tribes and groups spoke more than 200 dialects. These languages were derived from the Penutian (the Maidu, Miwok and Yokuts), the Hokan (the Chumash, Pomo, Salinas and Shasta), the Uto-Aztecan (the Tubabulabal, Serrano and Kinatemuk) and the Athapaskan (the Hupa, among others). Many of the “Mission Indians” who were driven out of the Southwest by Spanish colonization also spoke Uto-Aztecan dialects.

Despite this great diversity, many native Californians lived very similar lives. They did not practice much agriculture. Instead, they organized themselves into small, family-based bands of hunter-gatherers known as tribelets. Inter-tribelet relationships, based on well-established systems of trade and common rights, were generally peaceful.

Spanish explorers infiltrated the California region in the middle of the 16th century. In 1769, the cleric Junipero Serra established a mission at San Diego, inaugurating a particularly brutal period in which forced labor, disease and assimilation nearly exterminated the culture area’s native population.

The Northwest Coast

The Northwest Coast culture area, along the Pacific coast from British Columbia to the top of Northern California, has a mild climate and an abundance of natural resources. In particular, the ocean and the region’s rivers provided almost everything its people needed—salmon, especially, but also whales, sea otters, seals and fish and shellfish of all kinds. As a result, unlike many other hunter-gatherers who struggled to eke out a living and were forced to follow animal herds from place to place, the Indians of the Pacific Northwest were secure enough to build permanent villages that housed hundreds of people apiece.

Those villages operated according to a rigidly stratified social structure, more sophisticated than any outside of Mexico and Central America. A person’s status was determined by his closeness to the village’s chief and reinforced by the number of possessions—blankets, shells and skins, canoes and even slaves—he had at his disposal. (Goods like these played an important role in the potlatch, an elaborate gift-giving ceremony designed to affirm these class divisions.)

Prominent groups in the region included the Athapaskan Haida and Tlingit; the Penutian Chinook, Tsimshian and Coos; the Wakashan Kwakiutl and Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka); and the Salishan Coast Salish.

The Plateau

The Plateau culture area sat in the Columbia and Fraser River basins at the intersection of the Subarctic, the Plains, the Great Basin, California and the Northwest Coast (present-day Idaho, Montana and eastern Oregon and Washington). Most of its people lived in small, peaceful villages along streams and riverbanks and survived by fishing for salmon and trout, hunting and gathering wild berries, roots and nuts.

In the southern Plateau region, the great majority spoke languages derived from the Penutian (the Klamath, Klikitat, Modoc, Nez Perce, Walla Walla and Yakima or Yakama). North of the Columbia River, most (the Skitswish (Coeur d’Alene), Salish (Flathead), Spokane and Columbia) spoke Salishan dialects.

In the 18th century, other native groups brought horses to the Plateau. The region’s inhabitants quickly integrated the animals into their economy, expanding the radius of their hunts and acting as traders and emissaries between the Northwest and the Plains.

In 1805, the explorers Lewis and Clark passed through the area, followed by increasing numbers of white settlers. By the end of the 19th century, most of the remaining members of Plateau tribes had been cleared from their lands and resettled in government reservations.

Photo Galleries

HISTORY Vault: Native American History

From Comanche warriors to Navajo code talkers, learn more about Indigenous history.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Utility Menu

Pluralism Project Archive

Native american religious and cultural freedom: an introductory essay (2005).

I. No Word for Religion: The Distinctive Contours of Native American Religions

A. Fundamental Diversity We often refer to Native American religion or spirituality in the singular, but there is a fundamental diversity concerning Native American religious traditions. In the United States, there are more than five hundred recognized different tribes , speaking more than two hundred different indigenous languages, party to nearly four hundred different treaties , and courted by missionaries of each branch of Christianity. With traditional ways of life lived on a variety of landscapes, riverscapes, and seascapes, stereotypical images of buffalo-chasing nomads of the Plains cannot suffice to represent the people of Acoma, still raising corn and still occupying their mesa-top pueblo in what only relatively recently has come to be called New Mexico, for more than a thousand years; or the Tlingit people of what is now Southeast Alaska whose world was transformed by Raven, and whose lives revolve around the sea and the salmon. Perhaps it is ironic that it is their shared history of dispossession, colonization, and Christian missions that is most obviously common among different Native peoples. If “Indian” was a misnomer owing to European explorers’ geographical wishful thinking, so too in a sense is “Native American,”a term that elides the differences among peoples of “North America” into an identity apparently shared by none at the time the continents they shared were named for a European explorer. But the labels deployed by explorers and colonizers became an organizing tool for the resistance of the colonized. As distinctive Native people came to see their stock rise and fall together under “Indian Policy,” they resourcefully added that Native or Indian identity, including many of its symbolic and religious emblems, to their own tribal identities. A number of prophets arose with compelling visions through which the sacred called peoples practicing different religions and speaking different languages into new identities at once religious and civil. Prophetic new religious movements, adoption and adaptation of Christian affiliation, and revitalized commitments to tribal specific ceremonial complexes and belief systems alike marked religious responses to colonialism and Christian missions. And religion was at the heart of negotiating these changes. “More than colonialism pushed,” Joel Martin has memorably written, “the sacred pulled Native people into new religious worlds.”(Martin) Despite centuries of hostile and assimilative policies often designed to dismantle the structures of indigenous communities, language, and belief systems, the late twentieth century marked a period of remarkable revitalization and renewal of Native traditions. Built on centuries of resistance as well as strategic accommodations, Native communities from the 1960s on have vigorously pressed their claims to religious self-determination.

B. "Way of Life, not Religion" In all their diversity, people from different Native nations hasten to point out that their respective languages include no word for “religion”, and maintain an emphatic distinction between ways of life in which economy, politics, medicine, art, agriculture, etc., are ideally integrated into a spiritually-informed whole. As Native communities try to continue their traditions in the context of a modern American society that conceives of these as discrete segments of human thought and activity, it has not been easy for Native communities to accomplish this kind of integration. Nor has it been easy to to persuade others of, for example, the spiritual importance of what could be construed as an economic activity, such as fishing or whaling.

C. Oral Tradition and Indigenous Languages Traversing the diversity of Native North American peoples, too, is the primacy of oral tradition. Although a range of writing systems obtained existed prior to contact with Europeans, and although a variety of writing systems emerged from the crucible of that contact, notably the Cherokee syllabary created by Sequoyah and, later, the phonetic transcription of indigenous languages by linguists, Native communities have maintained living traditions with remarkable care through orality. At first glance, from the point of view of a profoundly literate tradition, this might seem little to brag about, but the structure of orality enables a kind of fluidity of continuity and change that has clearly enabled Native traditions to sustain, and even enlarge, themselves in spite of European American efforts to eradicate their languages, cultures, and traditions. In this colonizing context, because oral traditions can function to ensure that knowledge is shared with those deemed worthy of it, orality has proved to be a particular resource to Native elders and their communities, especially with regard to maintaining proper protocols around sacred knowledge. So a commitment to orality can be said to have underwritten artful survival amid the pressures of colonization. It has also rendered Native traditions particularly vulnerable to exploitation. Although Native communities continue to privilege the kinds of knowledge kept in lineages of oral tradition, courts have only haltingly recognized the evidentiary value of oral traditions. Because the communal knowledge of oral traditions is not well served by the protections of intellectual property in western law, corporations and their shareholders have profited from indigenous knowledge, especially ethnobotanical and pharmacological knowledge with few encumbrances or legal contracts. Orality has also rendered Native traditions vulnerable to erosion. Today, in a trend that linguists point out is global, Native American languages in particular are to an alarming degree endangered languages. In danger of being lost are entire ways of perceiving the world, from which we can learn to live more sustainable, balanced, lives in an ecocidal age.

D. "Religious" Regard for the Land In this latter respect of being not only economically land-based but culturally land-oriented, Native religious traditions also demonstrate a consistency across their fundamental diversity. In God is Red ,Vine Deloria, Jr. famously argued that Native religious traditions are oriented fundamentally in space, and thus difficult to understand in religious terms belonging properly tothe time-oriented traditions of Christianity and Judaism. Such a worldview is ensconced in the idioms, if not structures, of many spoken Native languages, but living well on particular landscapes has not come naturally to Native peoples, as romanticized images of noble savages born to move silently through the woods would suggest. For Native peoples, living in balance with particular landscapes has been the fruit of hard work as well as a product of worldview, a matter of ethical living in worlds where non human life has moral standing and disciplined attention to ritual protocol. Still, even though certain places on landscapes have been sacred in the customary sense of being wholly distinct from the profane and its activity, many places sacred to Native peoples have been sources of material as well as spiritual sustenance. As with sacred places, so too with many sacred practices of living on landscapes. In the reckoning of Native peoples, pursuits like harvesting wild rice, spearing fish or hunting certain animals can be at once religious and economic in ways that have been difficult for Western courts to acknowledge. Places and practices have often had both sacred and instrumental value. Thus, certain cultural freedoms are to be seen in the same manner as religious freedoms. And thus, it has not been easy for Native peoples who have no word for “religion” to find comparable protections for religious freedom, and it is to that troubled history we now turn.

II. History of Native American Religious and Cultural Freedom

A. Overview That sacred Native lifeways have only partly corresponded to the modern Western language of “religion,” the free exercise of which is ostensibly protected by the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution , has not stopped Native communities from seeking protection of their freedom to exercise and benefit from those lifeways. In the days of treaty making, formally closed by Congress in 1871, and in subsequent years of negotiated agreements, Native communities often stipulated protections of certain places and practices, as did Lakota leaders in the Fort Laramie Treaty when they specifically exempted the Paha Sapa, subsequently called the Black Hills from land cessions, or by Ojibwe leaders in the 1837 treaty, when they expressly retained “usufruct” rights to hunt, fish, and gather on lands otherwise ceded to the U.S. in the treaty. But these and other treaty agreements have been honored neither by American citizens nor the United States government. Native communities have struggled to secure their rights and interests within the legal and political system of the United States despite working in an English language and in a legal language that does not easily give voice to Native regard for sacred places, practices, and lifeways. Although certain Native people have appealed to international courts and communities for recourse, much of the material considered in this website concerns Native communities’ efforts in the twentieth and twenty-first century to protect such interests and freedoms within the legal and political universe of the United States.

B. Timeline 1871 End of Treaty Making Congress legislates that no more treaties are to be made with tribes and claims “plenary power” over Indians as wards of U.S. government. 1887-1934 Formal U.S. Indian policy of assimilation dissolves communal property, promotes English only boarding school education, and includes informal and formalized regulation and prohibition of Native American ceremonies. At the same time, concern with “vanishing Indians” and their cultures drives a large scale effort to collect Native material culture for museum preservation and display. 1906 American Antiquities Act Ostensibly protects “national” treasures on public lands from pilfering, but construes Native American artifacts and human remains on federal land as “archeological resources,” federal property useful for science. 1921 Bureau of Indian Affairs Continuing an administrative trajectory begun in the 1880's, the Indian Bureau authorized its field agents to use force and imprisonment to halt religious practices deemed inimical to assimilation. 1923 Bureau of Indian Affairs The federal government tries to promote assimilation by instructing superintendents and Indian agents to supress Native dances, prohibiting some and limiting others to specified times. 1924 Pueblos make appeal for religious freedom protection The Council of All the New Mexico Pueblos appeals to the public for First Amendment protection from Indian policies suppressing ceremonial dances. 1924 Indian Citizenship Act Although uneven policies had recognized certain Indian individuals as citizens, all Native Americans are declared citizens by Congressional legislation. 1928 Meriam Report Declares federal assimilation policy a failure 1934 Indian Reorganization Act Officially reaffirms legality and importance of Native communities’ religious, cultural, and linguistic traditions. 1946 Indian Claims Commission Federal Commission created to put to rest the host of Native treaty land claims against the United States with monetary settlements. 1970 Return of Blue Lake to Taos Pueblo After a long struggle to win support by President Nixon and Congress, New Mexico’s Taos Pueblo secures the return of a sacred lake, and sets a precedent that threatened many federal lands with similar claims, though regulations are tightened. Taos Pueblo still struggles to safeguard airspace over the lake. 1972 Portions of Mount Adams returned to Yakama Nation Portions of Washington State’s Mount Adams, sacred to the Yakama people, was returned to that tribe by congressional legislation and executive decision. 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act Specifies Native American Church, and other native American religious practices as fitting within religious freedom. Government agencies to take into account adverse impacts on native religious freedom resulting from decisions made, but with no enforcement mechanism, tribes were left with little recourse. 1988 Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association Three Calif. Tribes try to block logging road in federal lands near sacred Mt. Shasta Supreme Court sides w/Lyng, against tribes. Court also finds that AIRFA contains no legal teeth for enforcement. 1990 Employment Division, Department of Human Resources v. Smith Oregon fires two native chemical dependency counselors for Peyote use. They are denied unemployment compensation. They sue. Supreme Court 6-3 sides w/Oregon in a major shift in approach to religious freedom. Scalia, for majority: Laws made that are neutral to religion, even if they result in a burden on religious exercise, are not unconstitutional. Dissent identifies this more precisely as a violation of specific congressional intent to clarify and protect Native American religious freedoms 1990 Native American Graves and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) Mandates return of human remains, associated burial items, ceremonial objects, and "cultural patrimony” from museum collections receiving federal money to identifiable source tribes. Requires archeologists to secure approval from tribes before digging. 1990 “Traditional Cultural Properties” Designation created under Historic Preservation Act enables Native communities to seek protection of significant places and landscapes under the National Historic Preservation Act. 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act Concerning Free Exercise Claims, the burden should be upon the government to prove “compelling state interest” in laws 1994 Amendments to A.I.R.F.A Identifies Peyote use as sacramental and protected by U.S., despite state issues (all regs must be made in consultation with reps of traditional Indian religions. 1996 President Clinton's Executive Order (13006/7) on Native American Sacred Sites Clarifies Native American Sacred Sites to be taken seriously by government officials. 1997 City of Bourne v. Flores Supreme Court declares Religious Freedom Restoration Act unconstitutional 2000 Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) Protects religious institutions' rights to make full use of their lands and properties "to fulfill their missions." Also designed to protect the rights of inmates to practice religious traditions. RLUIPA has notably been used in a number of hair-length and free-practice cases for Native inmates, a number of which are ongoing (see: Greybuffalo v. Frank).

III. Contemporary Attempts to Seek Protection Against the backdrop, Native concerns of religious and cultural freedoms can be distinguished in at least the following ways.

- Issues of access to, control over, and integrity of sacred lands

- Free exercise of religion in public correctional and educational institutions

- Free Exercise of “religious” and cultural practices prohibited by other realms of law: Controlled Substance Law, Endangered Species Law, Fish and Wildlife Law

- Repatriation of Human Remains held in museums and scientific institutions

- Repatriation of Sacred Objects/Cultural Patrimony in museums and scientific institutions

- Protection of Sacred and Other Cultural Knowledge from exploitation and unilateral appropriation (see Lakota Elder’s declaration).

In their attempts to press claims for religious and cultural self-determination and for the integrity of sacred lands and species, Native communities have identified a number of arenas for seeking protection in the courts, in legislatures, in administrative and regulatory decision-making, and through private market transactions and negotiated agreements. And, although appeals to international law and human rights protocols have had few results, Native communities bring their cases to the court of world opinion as well. It should be noted that Native communities frequently pursue their religious and cultural interests on a number of fronts simultaneously. Because Native traditions do not fit neatly into the category of “religion” as it has come to be demarcated in legal and political languages, their attempts have been various to promote those interests in those languages of power, and sometimes involve difficult strategic decisions that often involve as many costs as benefits. For example, seeking protection of a sacred site through historic preservation regulations does not mean to establish Native American rights over access to and control of sacred places, but it can be appealing in light of the courts’ recently narrowing interpretation of constitutional claims to the free exercise of religion. Even in the relative heyday of constitutional protection of the religious freedom of minority traditions, many Native elders and others were understandably hesitant to relinquish sacred knowledge to the public record in an effort to protect religious and cultural freedoms, much less reduce Native lifeways to the modern Western terms of religion. Vine Deloria, Jr. has argued that given the courts’ decisions in the 1980s and 1990s, especially in the Lyng and Smith cases, efforts by Native people to protect religious and cultural interests under the First Amendment did as much harm as good to those interests by fixing them in written documents and subjecting them to public, often hostile, scrutiny.

A. First Amendment Since the 1790s, the First Amendment to the Constitution has held that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” The former of the amendment’s two clauses, referred to as the “establishment clause” guards against government sponsorship of particular religious positions. The latter, known as the “free exercise” clause, protects the rights of religious minorites from government interference. But just what these clauses have been understood to mean, and how much they are to be weighed against other rights and protections, such as that of private property, has been the subject of considerable debate in constitutional law over the years. Ironically, apart from matters of church property disposition, it was not until the 1940s that the Supreme Court began to offer its clarification of these constitutional protections. As concerns free exercise jurisprudence, under Chief Justices Warren and Burger in the 1960s and 1970s, the Supreme Court had expanded free exercise protection and its accommodations considerably, though in retrospect too few Native communities were sufficiently organized or capitalized, or perhaps even motivated, given their chastened experience of the narrow possibilities of protection under U.S. law, to press their claims before the courts. Those communities who did pursue such interests experienced first hand the difficulty of trying to squeeze communal Native traditions, construals of sacred land, and practices at once economic and sacred into the conceptual box of religion and an individual’s right to its free exercise. By the time more Native communities pursued their claims under the free exercise clause in the 1980s and 1990s, however, the political and judicial climate around such matters had changed considerably. One can argue it has been no coincidence that the two, arguably three, landmark Supreme Court cases restricting the scope of free exercise protection under the Rehnquist Court were cases involving Native American traditions. This may be because the Court agrees to hear only a fraction of the cases referred to it. In Bowen v. Roy 476 U.S. 693 (1986) , the High Court held against a Native person refusing on religious grounds to a social security number necessary for food stamp eligibility. With even greater consequence for subsequent protections of sacred lands under the constitution, in Lyng v. Northwest Cemetery Protective Association 485 U.S. 439 (1988) , the High Court reversed lower court rulings which had blocked the construction of a timber road through high country sacred to California’s Yurok, Karok and Tolowa communities. In a scathing dissent, Harry Blackmun argued that the majority had fundamentally misunderstood the idioms of Native religions and the centrality of sacred lands. Writing for the majority, though, Sandra Day O’Connor’s opinion recognized the sincerity of Native religious claims to sacred lands while devaluing those claims vis a vis other competing goods, especially in this case, the state’s rights to administer “what is, after all, its land.” The decision also codified an interpretation of Congress’s legislative protections in the 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act as only advisory in nature. As of course happens in the U.S. judical system, such decisions of the High Court set new precedents that not only shape the decisions of lower courts, but that have a chilling effect on the number of costly suits brought into the system by Native communities. What the Lyng decision began to do with respect to sacred land protection, was finished off with respect to restricting free exercise more broadly in the Rehnquist Court’s 1990 decision in Employment Division, State of Oregon v. Smith 484 U.S. 872 (1990) . Despite nearly a century of specific protections of Peyotism, in an unemployment compensation case involving two Oregon substance abuse counselors who had been fired because they had been found to be Peyote ingesting members of the Native American Church , a religious organization founded to secure first amendment protection in the first place, the court found that the state’s right to enforce its controlled substance laws outweighed the free exercise rights of Peyotists. Writing for the majority, Justice Scalia’s opinion reframed the entire structure of free exercise jurisprudence, holding as constitutional laws that do not intentionally and expressly deny free exercise rights even if they have the effect of the same. A host of minority religious communities, civil liberties organizations, and liberal Christian groups were alarmed at the precedent set in Smith. A subsequent legislative attempt to override the Supreme Court, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act , passed by Congress and signed into law in 1993 by President Clinton was found unconstitutional in City of Bourne v. Flores (1997) , as the High Court claimed its constitutional primacy as interpreter of the constitution.

i. Sacred Lands In light of the ruling in Lyng v. Northwest Cemetery Protective Association (1988) discussed immediately above, there have been few subsequent attempts to seek comparable protection of sacred lands, whether that be access to, control of, or integrity of sacred places. That said, three cases leading up to the 1988 Supreme Court decision were heard at the level of federal circuit courts of appeal, and are worthy of note for the judicial history of appeals to First Amendment protection for sacred lands. In Sequoyah v. Tennessee Valley Authority , 19800 620 F.2d 1159 (6th Cir. 1980) , the court remained unconvinced by claims that a proposed dam's flooding of non-reservation lands sacred to the Cherokee violate the free excersice clause. That same year, in Badoni v. Higginson , 638 F. 2d 172 (10th Cir. 1980) , a different Circuit Court held against Navajo claims about unconstitutional federal management of water levels at a am desecrating Rainbow Arch in Utah. Three years later, in Fools Crow v. Gullet , 760 F. 2d 856 (8th Cir. 1983), cert. Denied, 464 U.S.977 (1983) , the Eighth Circuit found unconvincing Lakota claims to constitutional protections to a vision quest site against measures involving a South Dakota state park on the site.

ii. Free Exercise Because few policies and laws that have the effect of infringing on Native American religious and cultural freedoms are expressly intended to undermine those freedoms, the High Court’s Smith decision discouraged the number of suits brought forward by Native communities under constitutional free exercise protection since 1990, but a number of noteworthy cases predated the 1990 Smith decision, and a number of subsequent free exercise claims have plied the terrain of free exercise in correctional institutions. Employment Division, State of Oregon v. Smith (1990)

- Prison:Sweatlodge Case Study

- Eagle Feathers: U.S. v. Dion

- Hunting for Ceremonial Purposes: Frank v. Alaska

iii. No Establishment As the history of First Amendment jurisprudence generaly shows (Flowers), free exercise protections bump up against establishment clause jurisprudence that protects the public from government endorsement of particular traditions. Still, it is perhaps ironic that modest protections of religious freedoms of tiny minorities of Native communities have undergone constitutional challenges as violating the establishment clause. At issue is the arguable line between what has been understood in jurisprudence as governmental accommodations enabling the free exercise of minority religions and government endorsement of those traditions. The issue has emerged in a number of challenges to federal administrative policies by the National Park Service and National Forest Service such as the voluntary ban on climbing during the ceremonially significant month of June on what the Lakota and others consider Bear Lodge at Devil’s Tower National Monument . It should be noted that the Mountain States Legal Foundation is funded in part by mining, timbering, and recreational industries with significant money interests in the disposition of federal lands in the west. In light of courts' findings on these Native claims to constitutional protection under the First Amendment, Native communities have taken steps in a number of other strategic directions to secure their religious and cultural freedoms.

B. Treaty Rights In addition to constitutional protections of religious free exercise, 370 distinct treaty agreements signed prior to 1871, and a number of subsequent “agreements” are in play as possible umbrellas of protection of Native American religious and cultural freedoms. In light of the narrowing of free exercise protections in Lyng and Smith , and in light of the Court’s general broadening of treaty right protections in the mid to late twentieth century, treaty rights have been identified as preferable, if not wholly reliable, protections of religious and cultural freedoms. Makah Whaling Mille Lacs Case

C. Intellectual Property Law Native communities have occasionally sought protection of and control over indigenous medicinal, botanical, ceremonial and other kinds of cultural knowledge under legal structures designed to protect intellectual property and trademark. Although some scholars as committed to guarding the public commons of ideas against privatizing corporate interests as they are to working against the exploitation of indigenous knowledge have warned about the consequences of litigation under Western intellectual property standards (Brown), the challenges of such exploitation are many and varied, from concerns about corporate patenting claims to medicinal and agricultural knowledge obtained from Native elders and teachers to protecting sacred species like wild rice from anticipated devastation by genetically modified related plants (see White Earth Land Recovery Project for an example of this protection of wild rice to logos ( Washington Redskins controversy ) and images involving the sacred Zia pueblo sun symbol and Southwest Airlines to challenges to corporate profit-making from derogatory representations of Indians ( Crazy Horse Liquor case ).

D. Other Statutory Law A variety of legislative efforts have had either the express purpose or general effect of providing protections of Native American religious and cultural freedoms. Some, like the Taos Pueblo Blue Lake legislation, initiated protection of sacred lands and practices of particular communities through very specific legislative recourse. Others, like the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act , enacted broad protections of Native American religious and cultural freedom [link to Troost case]. Culminating many years of activism, if not without controversy even in Native communities, Congress passed the American Indian Religious Freedom Act , signed into law in 1978 and amended in 1993, in order to recognize the often difficult fit between Native traditions and constitutional protections of the freedom of “religion” and ostensibly to safeguard such interests from state interference. Though much heralded for its symbolic value, the act was determined by the courts (most notably in the Lyng decision upon review of the congressional record to be only advisory in nature, lacking a specific “cause for action” that would give it legal teeth. To answer the Supreme Court's narrowing of the scope of free exercise protections in Lyng and in the 1990 Smith decision, Congress passed in 2000 the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) restoring to governments the substantial burden of showing a "compelling interest" in land use decisions or administrative policies that exacted a burden on the free exercise of religion and requiring them to show that they had exhausted other possibilities that would be less burdensome on the free exercise of religion. Two other notable legislative initiatives that have created statutory protections for a range of Native community religious and cultural interests are the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act and the Native American Language Act legislation beginning to recognize the significance and urgency of the protection and promotion of indigenous languages, if not supporting such initiatives with significant appropriations. AIRFA 1978 NAGPRA 1990 [see item h. below] Native American Language Act Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) 2000 National Historic Preservation Act [see item g below]

E. Administrative and Regulatory Policy and Law As implied in a number of instances above, many governmental decisions affecting Native American religious and cultural freedom occur at the level of regulation and the administrative policy of local, state, and federal governments, and as a consequence are less visible to those not locally or immediately affected.

F. Federal Recognition The United States officially recognizes over 500 distinct Native communities, but there remain numerous Native communities who know clearly who they are but who remain formally unrecognized by the United States, even when they receive recognition by states or localities. In the 1930s, when Congress created the structure of tribal governments under the Indian Reorganization Act, many Native communities, including treaty signatories, chose not to enroll themselves in the recognition process, often because their experience with the United States was characterized more by unwanted intervention than by clear benefits. But the capacity and charge of officially recognized tribal governments grew with the Great Society programs in the 1960s and in particular with an official U.S. policy of Indian self-determination enacted through such laws as the 1975 Indian Self Determination and Education Act , which enabled tribal governments to act as contractors for government educational and social service programs. Decades later, the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act formally recognized the authority of recognized tribal governments to engage in casino gaming in cooperation with the states. Currently, Native communities that remain unrecognized are not authorized to benefit from such programs and policies, and as a consequence numerous Native communities have stepped forward to apply for federal recognition in a lengthy, laborious, and highly-charged political process overseen by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Office of Federal Acknowledgment . Some communities, like Michigan’s Little Traverse Band of Odawa have pursued recognition directly through congressional legislation. As it relates to concerns of Native American religious and cultural freedom, more is at stake than the possibility to negotiate with states for the opening of casinos. Federal recognition gives Native communities a kind of legal standing to pursue other interests with more legal and political resources at their disposal. Communities lacking this standing, for example, are not formally included in the considerations of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (item H. below).

G. Historic Preservation Because protections under the National Historic Preservation Act have begun to serve as a remedy for protection of lands of religious and cultural significance to Native communities, in light of first amendment jurisprudence since Lyng , it bears further mention here. Native communities seeking protections through Historic Preservation determinations are not expressly protecting Native religious freedom, nor recognizing exclusive access to, or control of sacred places, since the legislation rests on the importance to the American public at large of sites of historic and cultural value, but in light of free exercise jurisprudence since Lyng , historic preservation has offered relatively generous, if not exclusive, protection. The National Historic Preservation Act as such offered protection on the National Register of Historic Places, for the scholarly, especially archeological, value of certain Native sites, but in 1990, a new designation of “traditional cultural properties” enabled Native communities and others to seek historic preservation protections for properties associated “wit cultural practices or beliefs of a living community that (a) are rooted in that community’s history, and (b) are important in maintaining the continuing cultural identity of the community.” The designation could include most communities, but were implicitly geared to enable communities outside the American mainstream, perhaps especially Native American communities, to seek protection of culturally important and sacred sites without expressly making overt appeals to religious freedom. (King 6) This enabled those seeking recognition on the National Register to skirt a previous regulatory “religious exclusion” that discouraged inclusion of “properties owned by religious institutions or used for religious purposes” by expressly recognizing that Native communities don’t distinguish rigidly between “religion and the rest of culture” (King 260). As a consequence, this venue of cultural resource management has served Native interests in sacred lands better than others, but it remains subject to review and change. Further it does not guarantee protection; it only creates a designation within the arduous process of making application to the National Register of Historic Places. Pilot Knob Nine Mile Canyon

H. Repatriation/Protection of Human Remains, Burial Items, and Sacred Objects Culminating centuries of struggle to protect the integrity of the dead and material items of religious and cultural significance, Native communities witnessed the creation of an important process for protection under the 1990 Native American Graves and Repatriation Act . The act required museums and other institutions in the United States receiving federal monies to share with relevant Native tribes inventories of their collections of Native human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of “cultural patrimony” (that is objects that were acquired from individuals, but which had belonged not to individuals, but entire communities), and to return them on request to lineal descendants or federally recognized tribes (or Native Hawaiian organizations) in those cases where museums can determine cultural affiliation, or as often happens, in the absence of sufficiently detailed museum data, to a tribe that can prove its cultural affiliation. The law also specifies that affiliated tribes own these items if they are discovered in the future on federal or tribal lands. Finally, the law also prohibits almost every sort of trafficking in Native American human remains, burial objects, sacred objects, and items of cultural patrimony. Thus established, the process has given rise to a number of ambiguities. For example, the law’s definition of terms gives rise to some difficulties. For example, “sacred objects” pertain to objects “needed for traditional Native American religions by their present day adherents.” Even if they are needed for the renewal of old ceremonies, there must be present day adherents. (Trope and Echo Hawk, 143). What constitutes “Cultural affiliation” has also given rise to ambiguity and conflict, especially given conflicting worldviews. As has been seen in the case of Kennewick Man the “relationship of shared group identity” determined scientifically by an archeologist may or may not correspond to a Native community’s understanding of its relation to the dead on its land. Even what constitutes a “real” can be at issue, as was seen in the case of Zuni Pueblo’s concern for the return of “replicas” of sacred Ahayu:da figures made by boy scouts. To the Zuni, these contained sacred information that was itself proprietary (Ferguson, Anyon, and Lad, 253). Disputes have arisen, even between different Native communities claiming cultural affiliation, and they are adjudicated through a NAGPRA Review Committee , convened of three representatives from Native communities, three from museum and scientific organizations, and one person appointed from a list jointly submitted by the other six.