The Problem With Feudalism

Later historians say the concept doesn't match reality

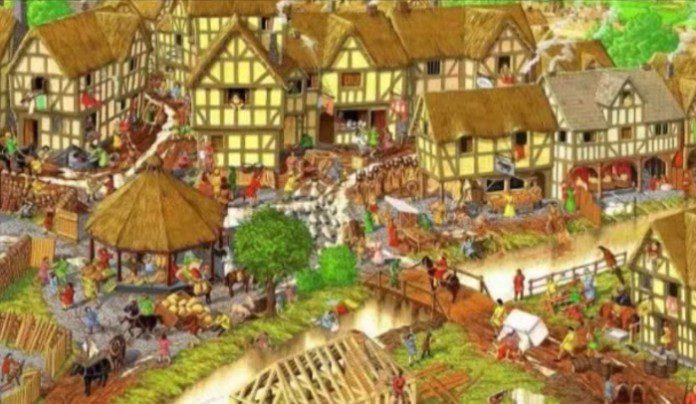

De Agostini / G. Dagli Orti / Getty Images

- People & Events

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- B.A., History, University of Texas at Austin

Medieval historians generally aren't bothered by words. The intrepid medievalist is always ready to leap into the rough-and-tumble milieu of Old English word origins, medieval French literature, and Latin Church documents. Icelandic sagas hold no terror for the medieval scholar. Next to these challenges, the esoteric terminology of medieval studies is mundane, no threat to the historian of the Middle Ages.

But one word has become the bane of medievalists everywhere. Use it in discussing medieval life and society, and the average medieval historian's face will screw up in revulsion.

What word has this power to annoy, disgust, and even upset the ordinarily cool, collected medievalist?

What Is Feudalism?

Every student of the Middle Ages is at least somewhat familiar with the term, usually defined as follows:

Feudalism was the dominant form of political organization in medieval Europe. It was a hierarchical system of social relationships wherein a noble lord granted land known as a fief to a free man, who in turn swore fealty to the lord as his vassal and agreed to provide military and other services. A vassal could also be a lord, granting portions of the land he held to other free vassals; this was known as "subinfeudation" and often led all the way up to the king. The land granted to each vassal was inhabited by serfs who worked the land for him, providing him with income to support his military endeavors; in turn, the vassal would protect the serfs from attack and invasion.

This is a simplified definition, and many exceptions and caveats go along with this model of medieval society. It is fair to say that this is the explanation for feudalism you'll find in most history textbooks of the 20th century, and it is very close to every dictionary definition available.

The problem? Virtually none of it is accurate.

Description Inaccurate

Feudalism was not the "dominant" form of political organization in medieval Europe. There was no "hierarchical system" of lords and vassals engaged in a structured agreement to provide military defense. There was no "subinfeudation" leading up to the king. The arrangement whereby serfs worked the land for a lord in return for protection, known as manorialism or seignorialism, was not part of a "feudal system." Monarchies of the early Middle Ages had their challenges and their weaknesses, but kings didn't use feudalism to exert control over their subjects, and the feudal relationship wasn't the "glue that held medieval society together," as had been said.

In short, feudalism as described above never existed in Medieval Europe.

For decades, even centuries, feudalism has characterized our view of medieval society. If it never existed, then why did so many historians say it did? Weren't entire books written on the subject? Who has the authority to say that all those historians were wrong? If the current consensus among "experts" in medieval history is to reject feudalism, why is it still presented as reality in nearly every medieval history textbook?

Concept Questioned

The word feudalism was never used during the Middle Ages. The term was invented by 16th- and 17th-century scholars to describe a political system of several hundred years earlier. This makes feudalism a post-medieval construct.

Constructs help us understand alien ideas in terms more familiar to our modern thought processes. Middle Ages and medieval are constructs. (Medieval people didn't think of themselves as living in a "middle" age—they thought they were living in the now, just like we do.) Medievalists might not like the way the term medieval is used as an insult or how absurd myths of past customs and behavior are commonly attributed to the Middle Ages, but most are confident that using Middle Ages and medieval to describe the era as between the ancient and early modern eras is satisfactory, however fluid the definition of all three timeframes might be.

But medieval has a fairly clear meaning based on a specific, easily defined viewpoint. Feudalism cannot be said to have the same.

In 16th-century France, Humanist scholars grappled with the history of Roman law and its authority in their own land. They examined a substantial collection of Roman law books. Among these books was the Libri Feudorum —the Book of Fiefs.

'Libri Feudorum'

The Libri Feudorum was a compilation of legal texts concerning the proper disposition of fiefs, which were defined in these documents as lands held by people referred to as vassals. The work had been put together in Lombardy, northern Italy, in the 1100s, and over the intervening centuries, lawyers and scholars had commented on it and added definitions and interpretations, or glosses. The Libri Feudorum is an extraordinarily significant work that has been barely studied since 16th-century French lawyers gave it a good look.

In their evaluation of the Book of Fiefs, the scholars made some reasonable assumptions:

- The fiefs under discussion in the texts were pretty much the same as the fiefs of 16th-century France—that is, lands belonging to nobles.

- Te Libri Feudorum was addressing actual legal practices of the 11th century, not simply expounding on an academic concept.

- The explanation of fiefs' origins in the Libri Feudorum —that grants were initially made for as long as the lord chose but were later extended to the grantee's lifetime and afterward made hereditary—was a reliable history and not mere conjecture.

The assumptions might have been reasonable, but were they correct? French scholars had every reason to believe they were and no real reason to dig any deeper. They weren't so much interested in the historical facts of the time period as they were in the legal questions addressed in the Libri Feudorum. Their foremost consideration was whether the laws had any authority in France. Ultimately, French lawyers rejected the authority of the Lombard Book of Fiefs.

Examining Assumptions

However, during their investigations, based in part on the assumptions outlined above, scholars who studied the Libri Feudorum formulated a view of the Middle Ages. This general picture included the idea that feudal relationships, wherein noblemen granted fiefs to free vassals in return for services, were important in medieval society because they provided social and military security at a time when the central government was weak or nonexistent. The idea was discussed in editions of the Libri Feudorum made by legal scholars Jacques Cujas and François Hotman, who both used the term feudum to indicate an arrangement involving a fief .

Other scholars soon saw value in the works of Cujas and Hotman and applied the ideas to their own studies. Before the 16th century ended, two Scottish lawyers—Thomas Craig and Thomas Smith—were using feudum in their classifications of Scottish lands and their tenure. Craig apparently first expressed the idea of feudal arrangements as a hierarchical system imposed on nobles and their subordinates by their monarch as a matter of policy. In the 17th century, Henry Spelman, a noted English antiquarian, adopted this viewpoint for English legal history.

Although Spelman never used the word feudalism , his work went a long way toward creating an "-ism" from the ideas over which Cujas and Hotman had theorized. Not only did Spelman maintain, as Craig had done, that feudal arrangements were part of a system, but he related the English feudal heritage with that of Europe, indicating that feudal arrangements were characteristic of medieval society as a whole. Spelman's hypothesis was accepted as fact by scholars who saw it as a sensible explanation of medieval social and property relations.

Fundamentals Unchallenged

Over the next several decades, scholars explored and debated feudal ideas. They expanded the meaning of the term from legal matters to other aspects of medieval society . They argued over the origins of feudal arrangements and expounded on the various levels of subinfeudation. They incorporated manorialism and applied it to the agricultural economy. They envisioned a complete system of feudal agreements running throughout Britain and Europe.

But they didn't challenge Craig's or Spelman's interpretation of the works of Cujas and Hotman, nor did they question the conclusions that Cujas and Hotman drew from the Libri Feudorum.

From the vantage point of the 21st century, it's easy to ask why the facts were overlooked in favor of the theory. Present-day historians engage in a rigorous examination of the evidence and clearly identify a theory as such. Why didn't 16th- and 17th-century scholars do the same? The simple answer is that history as a scholarly field has evolved over time; in the 17th century, the academic discipline of historical evaluation was in its infancy. Historians didn't have the tools, both physical and figurative, taken for granted today, nor did they have the example of scientific methods from other fields to incorporate into their learning processes.

Besides, having a straightforward model by which to view the Middle Ages gave scholars the sense that they understood the time period. Medieval society becomes so much easier to evaluate and comprehend if it can be labeled and fit into a simple organizational structure.

By the end of the 18th century, the term feudal system was used among historians, and by the middle of the 19th century, feudalism had become a fairly well-fleshed-out model, or construct, of medieval government and society. As the idea spread beyond academia, feudalism became a buzzword for any oppressive, backward, hidebound system of government. In the French Revolution , the "feudal regime" was abolished by the National Assembly , and in Karl Marx's "Communist Manifesto ," feudalism was the oppressive, agrarian-based economic system that preceded the industrialized, capitalist economy.

With such far-ranging appearances in academic and mainstream usage, breaking free of what was, essentially, a wrong impression would be an extraordinary challenge.

Questions Arise

In the late 19th century, the field of medieval studies began to evolve into a serious discipline. No longer did the average historian accept as fact everything that had been written by his or her predecessors and repeat it as a matter of course. Scholars of the medieval era began to question interpretations of the evidence and the evidence itself.

This wasn't a swift process. The medieval era was still the bastard child of historical study; a "dark age" of ignorance, superstition, and brutality, "a thousand years without a bath." Medieval historians had much prejudice, fanciful invention, and misinformation to overcome, and there was no concerted effort to shake things up and re-examine every theory ever floated about the Middle Ages. Feudalism had become so entrenched that it wasn't an obvious choice to overturn.

Even once historians began to recognize the "system" as a post-medieval construct, its validity wasn't questioned. As early as 1887, F.W. Maitland observed in a lecture on English constitutional history that "we do not hear of a feudal system until feudalism ceased to exist." He examined in detail what feudalism supposedly was and discussed how it could be applied to English medieval law, but he didn't question its existence.

Maitland was a well-respected scholar; much of his work is still enlightening and useful today. If such an esteemed historian treated feudalism as a legitimate system of law and government, why should anyone question him?

For a long time, nobody did. Most medievalists continued in Maitland's vein, acknowledging that the word was a construct—an imperfect one, at that—yet going forward with articles, lectures, treatises, and books on what feudalism had been or, at the very least, incorporating it into related topics as an accepted fact of the medieval era. Each historian presented his or her own interpretation of the model; even those claiming to adhere to a previous interpretation deviated from it in some significant way. The result was an unfortunate number of varying, sometimes conflicting, definitions of feudalism.

As the 20th century progressed, the discipline of history grew more rigorous. Scholars uncovered new evidence, examined it closely, and used it to modify or explain their view of feudalism. Their methods were sound, but their premise was problematic: They were trying to adapt a deeply flawed theory to a wide variety of facts.

Construct Denounced

Although several historians expressed concerns over the indefinite nature of the model and the term's imprecise meanings, it wasn't until 1974 that anyone thought to point out the most fundamental problems with feudalism. In a groundbreaking article titled "The Tyranny of a Construct: Feudalism and Historians of Medieval Europe," Elizabeth A.R. Brown leveled a finger at the academic community, denouncing the term feudalism and its continued use.

Brown maintained that the feudalism construct, developed after the Middle Ages, bore little resemblance to actual medieval society. Its many differing, even contradictory, definitions had so muddied the waters that it had lost any useful meaning and was interfering with the proper examination of evidence concerning medieval law and society. Scholars viewed land agreements and social relationships through the warped lens of the feudalism construct and either disregarded or dismissed anything that didn't fit into their version of the model. Brown asserted that, even considering how difficult it is to unlearn something, continuing to include feudalism in introductory texts would do readers a grave injustice.

Brown's article was well received in academic circles. Virtually no American or British medievalists objected to any part of it, and almost everyone agreed: Feudalism wasn't a useful term and really should go.

Yet, it stuck around.

Hasn't Disappeared

Some new publications in medieval studies avoided the term altogether; others used it sparingly, focusing on actual laws, land tenures, and legal agreements instead of on the model. Some books on medieval society refrained from characterizing that society as "feudal." Others, while acknowledging that the term was in dispute, continued to use it as a "useful shorthand" for lack of a better term, but only as far as it was necessary.

But some authors still included descriptions of feudalism as a valid model of medieval society, with little or no caveat. Not every medievalist had read Brown's article or had a chance to consider its implications or discuss it with colleagues. Additionally, revising work conducted on the premise that feudalism was a valid construct would require the kind of reassessment that few historians were prepared to engage in.

Perhaps most significantly, no one had presented a reasonable model or explanation to use in place of feudalism. Some historians and authors felt they had to provide their readers with a handle by which to grasp the general ideas of medieval government and society. If not feudalism, then what?

Yes, the emperor had no clothes, but for now, he would just have to run around naked.

- Feudalism in Japan and Europe

- The Early, High and Late Middle Ages

- Defining the Middle Ages

- The Top 8 Medieval History Books

- What Does "Medieval" Mean?

- A Beginner's Guide to the Renaissance

- Role and Importance of Children in the Middle Ages

- The Kingdom of Mali and the Splendor of Medieval Africa

- Medieval Times Printables

- Enslavement and Chains in Medieval Times

- The Learning Years of Medieval Childhood

- Humanity Bloomed During the Renaissance

- A Brief History of Japan's Daimyo Lords

- Wool in the Middle Ages

- A Guide to Renaissance Humanism

- Types of Meat

The Benefits and Drawbacks of Feudalism in Medieval Europe

European feudalism was an economic, political, and social system practiced in the Middle Ages. Land was granted in return for labor and military support. There are various benefits and disadvantages involved. Feudalism was suitable for the times, encouraged local control, and stability, and maintained a set of values. Meanwhile, it promoted inequality, a weak central government, was insecure in various ways, and hindered advancement.

What Is Feudalism?

The word “feudalism” arises from a “fief,” the name given to the basic self-sufficient unit of land during the Middle Ages . Feudalism had social, political, and economic aspects.

The Middle Ages lasted from around 500-1500 CE. Before this time, the Roman Empire controlled Western Europe. The empire broke apart and feudalism developed.

Feudalism was a system where land was granted in return for labor and military support. It was largely an agricultural society. Small villages grew up around the farms to serve their needs.

Peasants farmed the land. Local nobility (knights) controlled the land in return for military service to the king. There was a weak center of power and Western Europe was split up into many small kingdoms. The Catholic Church was very powerful and had a large role in social life.

What Were The Benefits Of Feudalism?

[1] suitable for the needs of the time.

The Fall of the Roman Empire resulted in a power vacuum in Western Europe.

There was no longer a strong central government to provide basic needs, including defending people from bandits and foreign invaders. A new local-based system had to be developed.

Feudalism was suitable for the needs of the times. There was no longer a strong central government so small communities had to be self-sufficient .

It was a sensible type of society for agricultural-based times when the economy was based on land, not the cash-based system of modern capitalism.

Meanwhile, the layers of control (peasants, nobles, king) still enabled smaller communities to join together into larger ones. Loose confederations developed, extending power bases.

[2] Stability

Each group in society had a place. Peasants farmed their land generation after generation. Peasants, nobles, and kings had responsibilities based on how things had always gone.

The Church helped by setting forth basic social rules for everyone to follow. A son followed in the footsteps of their father. Life might be hard at times with disease, famine, or the occasional war, but it followed a certain expected ebb and flow.

Feudalism provided peace and security .

[3] Local Control

A person interested in federalism , the division of local and national government, might find feudalism a useful model. Local control thrived based on their specific needs.

Peasants had a large degree of self-control as long as they provided a certain amount of goods and services to their local lord. Local estates (called “manors”) were self-sufficient, providing all the basic needs for the community. Smaller units were easier to govern.

Meanwhile, each local noble was not merely a self-sufficient unit. They were part of a larger kingdom. They joined together to serve the king and protect a wider area of territory.

[4] Values

Feudalism was not just an economic and political system. It was also a system of values.

A basic system of obligation is in place. Everybody has a responsibility to someone else. Peasants provided goods and services in return for land and security. Nobles had obligations to peasants and the king. Everyone served the Church, which in return protected everyone’s souls.

Knights developed a code of honor called “ chivalry .” Feudalism was a theocracy , with church rules being followed, including in matters of family life.

What Were the Disadvantages?

[1] inequality.

Feudalism was a class-based society. Those with power were able to abuse those without it. The lack of a strong government and justice system made things worse.

Peasants were not allowed to leave the land without permission. Different degrees of nobility arose, not based on merit alone, but on who your parents might be.

It also was a male-dominated world, with power passing from father to son. Women sometimes had power. Women had important roles on farms and in village businesses. But, there was no equality of the sexes. Men controlled married life too in a system known as “coverture.”

[2] Weak National Control

A king had limited power. The central government was weak.

This limited the ability to have a large, powerful country. It made kingdoms more open to invasion and less able to address the needs of the people as a whole.

A system of self-sufficient small territories limited trade. A powerful government also is important for the development of industry , including regulations and infrastructure.

[3] Insecurity

Feudal life was insecure in a variety of ways.

A system of small communities resulted in nobility fighting over land. Warfare was a common occurrence during the Middle Ages. A bad crop or outbreak of disease could be disastrous.

[4] Lack of Development

Each community also was isolated from the others. People often spent their whole lives without traveling a few miles away from their homes. It was a limited existence.

There was limited room for advancement. A person had little chance to do better than their parents or try something new. Their roles in life were fixed.

There was a limited need for industry, including a small market for goods. Land is a fixed thing, unlike the flexibility of money and trade goods. This blocked development and expansion.

Feudalism After the Middle Ages

A range of developments led to the decline of feudalism, the growth of the industrial revolution, and the current post-industrial world that we live in today.

Meanwhile, European powers spread their control to the Americas, Africa, and Asia. The colonial system spread feudalism into new locations. The results linger on in some form today.

Feudalism now seems like something only found in medieval tales of yore. But, in its own time, there was a place for the system though its disadvantages in time helped us move past it.

Teach and Thrive

A Bronx, NY veteran high school social studies teacher who has learned most of what she has learned through trial and error and error and error.... and wants to save others that pain.

RELATED ARTICLES:

What Were Medieval Bathrooms Like?

The Roman Empire ended (it had fallen and couldn’t get up) in 476. The people at the time did not know it then, but it was the Middle Ages. Medieval times. You can read about it...

Medieval Times Summary (Download Included)

[convertkit form=1816758] If you’re looking for a brief (650 words) summary on a topic in history you’re in the right place! You can find reading passages for U.S. History and World History...

Home — Essay Samples — History — Feudalism — Feudalism Analysis

Feudalism Analysis

- Categories: Feudalism

About this sample

Words: 657 |

Published: Mar 13, 2024

Words: 657 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Origins of feudalism, characteristics of feudalism, impact of feudalism, significance of feudalism.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 792 words

2 pages / 927 words

4 pages / 1692 words

2 pages / 1063 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Feudalism

Feudalism was established in Europe by the 800s CE but appeared later in the 1100s in japan. European feudalism ended by the growth of a stronger political states in the 16th century, but Japanese feudalism held on until the [...]

Feudalism, a system of social organization that dominated Medieval Europe, has been a topic of much debate among historians. In this essay, we will explore the definition of feudalism, its history, and the ongoing debates [...]

Feudalism in France stands as a cornerstone of medieval European history, representing a complex social, economic, and political system that dominated the region for centuries. This essay delves into the intricacies of feudalism [...]

Feudalism, a socio-economic system that dominated European societies from the 9th to the 15th century, has often been a topic of debate among historians and scholars. While some view it as a crucial and functional structure, [...]

Feudalism was the way of life for people in the Middle Ages. Some people, like the royalty and nobles, supported and liked feudalism. Others, like serfs and slaves, did not enjoy feudalism. Everybody in society was involved with [...]

After the collapse of the Roman Empire, feudalism was by far the most prevalent of social systems during the ninth and fifteenth centuries throughout Western Europe. This system found its supposed highest authority in the king [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Ch. 8 The Middle Ages in Europe

Learning objective.

- Recall the structure of the feudal state and the responsibilities and obligations of each level of society

- Feudalism flourished in Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries.

- Feudalism in England determined the structure of society around relationships derived from the holding and leasing of land, or fiefs .

- In England, the feudal pyramid was made up of the king at the top with the nobles, knights, and vassals below him.

- Before a lord could grant land to a tenant he would have to make him a vassal at a formal ceremony. This ceremony bound the lord and vassal in a contract.

- While modern writers such as Marx point out the negative qualities of feudalism, such as the exploitation and lack of social mobility for the peasants, the French historian Marc Bloch contends that peasants were part of the feudal relationship; while the vassals performed military service in exchange for the fief, the peasants performed physical labour in return for protection, thereby gaining some benefit despite their limited freedom.

- The 11th century in France saw what has been called by historians a “feudal revolution” or “mutation” and a “fragmentation of powers” that increased localized power and autonomy.

In the Middle Ages this was the ceremony in which a feudal tenant or vassal pledged reverence and submission to his feudal lord, receiving in exchange the symbolic title to his new position.

An oath, from the Latin fidelitas (faithfulness); a pledge of allegiance of one person to another.

Persons who entered into a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe.

Heritable property or rights granted by an overlord to a vassal.

mesne tenant

A lord in the feudal system who had vassals who held land from him, but who was himself the vassal of a higher lord.

Feudalism was a set of legal and military customs in medieval Europe that flourished between the 9th and 15th centuries. It can be broadly defined as a system for structuring society around relationships derived from the holding of land, known as a fiefdom or fief, in exchange for service or labour.

The classic version of feudalism describes a set of reciprocal legal and military obligations among the warrior nobility, revolving around the three key concepts of lords, vassals, and fiefs. A lord was in broad terms a noble who held land, a vassal was a person who was granted possession of the land by the lord, and a fief was what the land was known as. In exchange for the use of the fief and the protection of the lord, the vassal would provide some sort of service to the lord. There were many varieties of feudal land tenure, consisting of military and non-military service. The obligations and corresponding rights between lord and vassal concerning the fief formed the basis of the feudal relationship.

Feudalism, in its various forms, usually emerged as a result of the decentralization of an empire, especially in the Carolingian empires, which lacked the bureaucratic infrastructure necessary to support cavalry without the ability to allocate land to these mounted troops. Mounted soldiers began to secure a system of hereditary rule over their allocated land, and their power over the territory came to encompass the social, political, judicial, and economic spheres.

Many societies in the Middle Ages were characterized by feudal organizations, including England, which was the most structured feudal society, France, Italy, Germany, the Holy Roman Empire, and Portugal. Each of these territories developed feudalism in unique ways, and the way we understand feudalism as a unified concept today is in large part due to critiques after its dissolution. Karl Marx theorized feudalism as a pre-capitalist society, characterized by the power of the ruling class (the aristocracy) in their control of arable land, leading to a class society based upon the exploitation of the peasants who farm these lands, typically under serfdom and principally by means of labour, produce, and money rents.

While modern writers such as Marx point out the negative qualities of feudalism, the French historian Marc Bloch contends that peasants were an integral part of the feudal relationship: while the vassals performed military service in exchange for the fief, the peasants performed physical labour in return for protection, thereby gaining some benefit despite their limited freedom. Feudalism was thus a complex social and economic system defined by inherited ranks, each of which possessed inherent social and economic privileges and obligations. Feudalism allowed societies in the Middle Ages to retain a relatively stable political structure even as the centralized power of empires and kingdoms began to dissolve.

Structure of the Feudal State in England

Feudalism in 12th-century England was among the better structured and established systems in Europe at the time. The king was the absolute “owner” of land in the feudal system, and all nobles, knights, and other tenants, termed vassals, merely “held” land from the king, who was thus at the top of the feudal pyramid.

Below the king in the feudal pyramid was a tenant-in-chief (generally in the form of a baron or knight), who was a vassal of the king. Holding from the tenant-in-chief was a mesne tenant—generally a knight or baron who was sometimes a tenant-in-chief in their capacity as holder of other fiefs. Below the mesne tenant, further mesne tenants could hold from each other in series.

Before a lord could grant land (a fief) to someone, he had to make that person a vassal. This was done at a formal and symbolic ceremony called a commendation ceremony, which was composed of the two-part act of homage and oath of fealty. During homage, the lord and vassal entered into a contract in which the vassal promised to fight for the lord at his command, while the lord agreed to protect the vassal from external forces.

Roland pledges his fealty to Charlemagne. Roland (right) receives the sword, Durandal, from the hands of Charlemagne (left). From a manuscript of a chanson de geste, c. 14th Century.

Once the commendation ceremony was complete, the lord and vassal were in a feudal relationship with agreed obligations to one another. The vassal’s principal obligation to the lord was “aid,” or military service. Using whatever equipment the vassal could obtain by virtue of the revenues from the fief, he was responsible for answering calls to military service on behalf of the lord. This security of military help was the primary reason the lord entered into the feudal relationship. In addition, the vassal could have other obligations to his lord, such as attendance at his court, whether manorial or baronial, or at the king’s court.

The vassal’s obligations could also involve providing “counsel,” so that if the lord faced a major decision he would summon all his vassals and hold a council. At the level of the manor this might be a fairly mundane matter of agricultural policy, but could also include sentencing by the lord for criminal offenses, including capital punishment in some cases. In the king’s feudal court, such deliberation could include the question of declaring war. These are only examples; depending on the period of time and location in Europe, feudal customs and practices varied.

Feudalism in France

In its origin, the feudal grant of land had been seen in terms of a personal bond between lord and vassal, but with time and the transformation of fiefs into hereditary holdings, the nature of the system came to be seen as a form of “politics of land.” The 11th century in France saw what has been called by historians a “feudal revolution” or “mutation” and a “fragmentation of powers” that was unlike the development of feudalism in England, Italy, or Germany in the same period or later. In France, counties and duchies began to break down into smaller holdings as castellans and lesser seigneurs took control of local lands, and (as comital families had done before them) lesser lords usurped/privatized a wide range of prerogatives and rights of the state—most importantly the highly profitable rights of justice, but also travel dues, market dues, fees for using woodlands, obligations to use the lord’s mill, etc. Power in this period became more personal and decentralized.

- Boundless World History. Authored by : Boundless. Located at : https://www.boundless.com/world-history/textbooks/boundless-world-history-textbook/ . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Feudalism and knights in medieval europe.

Viking Sword

Aquamanile in the Form of a Mounted Knight

A Knight of the d'Aluye Family

Michael Norris Department of Education, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2001

From the ninth to the early eleventh centuries, invasions of the Magyars from the east, Muslims from the south, and Vikings from the north struck western Europe. This unrest ultimately spurred greater unity in England and Germany, but in northern France centralized authority broke down and the region split into smaller and smaller political units. By the ninth century, many knights and nobles held estates (fiefs) granted by greater lords in return for military and other service. This feudal system (from the medieval Latin feodum or feudum , fee or fief) enabled a cash-poor but land-rich lord to support a military force. But this was not the only way that land was held, knights maintained, and loyalty to a lord retained. Lands could be held unconditionally, landless knights could be sheltered in noble households, and loyalties could be maintained through kinship, friendship, or wages.

Mounted armored warriors , or knights (from the Old English cniht , boy or servant), were the dominant forces of medieval armies. The twelfth-century Byzantine princess Anna Komnena wrote that the impact of a group of charging French knights “might rupture the walls of Babylon .” At first, most knights were of humble origins, some of them not even possessing land, but by the later twelfth century knights were considered members of the nobility and followed a system of courteous knightly behavior called chivalry (from cheval , the French word for horse). During and after the fourteenth century , weapons that were particularly effective against horsemen appeared on the battlefield, such as the longbow, pike, halberd, and cannon. Yet despite the knights’ gradual loss of military importance, the system by which noble families were identified, called heraldry, continued to flourish and became more complex. The magnificence of their war games—called tournaments—also increased, as did the number of new knightly orders, such as the Order of the Garter.

Norris, Michael. “Feudalism and Knights in Medieval Europe.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/feud/hd_feud.htm (October 2001)

Further Reading

Bennett, Judith M., and C. Warren Hollister. Medieval Europe: A Short History . 10th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2005.

Gies, Joseph and Frances Gies. Life in a Medieval Castle . New York: Harper & Row, 1979.

Additional Essays by Michael Norris

- Norris, Michael. “ The Papacy during the Renaissance .” (August 2007)

- Norris, Michael. “ Arms and Armor in Medieval Europe .” (October 2001)

- Norris, Michael. “ Life of Jesus of Nazareth .” (originally published June 2008, last revised September 2008)

Related Essays

- Arms and Armor in Medieval Europe

- The Crusades (1095–1291)

- The Decoration of Arms and Armor

- Fashion in European Armor, 1000–1300

- The Function of Armor in Medieval and Renaissance Europe

- The Age of Saint Louis (1226–1270)

- Arms and Armor in Renaissance Europe

- Arms and Armor—Common Misconceptions and Frequently Asked Questions

- Art and Death in the Middle Ages

- Byzantium (ca. 330–1453)

- Courtship and Betrothal in the Italian Renaissance

- The Decoration of European Armor

- Domestic Art in Renaissance Italy

- Famous Makers of Arms and Armors and European Centers of Production

- Fashion in European Armor

- Fashion in European Armor, 1300–1400

- Fashion in European Armor, 1400–1500

- Medieval Aquamanilia

- Nuptial Furnishings in the Italian Renaissance

- Romanesque Art

- Techniques of Decoration on Arms and Armor

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of Europe

- France, 1000–1400 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1000–1400 A.D.

- Low Countries, 1000–1400 A.D.

- 10th Century A.D.

- 11th Century A.D.

- 12th Century A.D.

- 13th Century A.D.

- 14th Century A.D.

- 9th Century A.D.

- Frankish Art

- Great Britain and Ireland

- Horse Trappings

- Islamic Art

- Medieval Art

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

15.4: The Feudal System

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 17082

- Christopher Brooks

- Portland Community College

While most Europeans (excluding the Jewish communities, the few remaining pagans, and members of heretical groups) may have come to share a religious identity by the eleventh century, Europe was fragmented politically. The numerous Germanic tribes that had dismantled the Western Empire formed the nucleus of the early political units of western Christendom. The Germanic peoples themselves had started as minorities, ruling over formerly Roman subjects. They tended to inherit Roman bureaucracy and rely on its officials and laws when ruling their subjects, but they also had their own traditions of Germanic law based on clan membership.

The so-called “ feudal ” system of law was one based on codes of honor and reciprocity. In the original Germanic system, each person was tied to his or her clan above all else, and an attack on an individual immediately became an issue for the entire clan. Any dishonor had to be answered by an equivalent dishonor, most often meeting insult with violence. Likewise, rulership was tied closely to clan membership, with each king being the head of the most powerful clan rather than an elected official or even necessarily a hereditary monarchy that transcended clan lines. This unregulated, traditional, and violence-based system of “law” stood in contrast to the written codes of Roman law that still survived in the aftermath of the fall of Rome itself.

Over time, the Germanic rulers mixed with their subjects to the point that distinctions between them were nonexistent. Likewise, Roman law faded away to be replaced with traditions of feudal law and a very complex web of rights and privileges that were granted to groups within society by rulers (to help ensure the loyalty of their subjects). Thus, clan loyalty became less important over the centuries than did the rights, privileges, and pledges of loyalty offered and held by different social categories. Historians refer to that social and political system as "feudalism" or "the feudal system," a hierarchical, class-based structure in which kings, lords, and priests ruled over the vast majority of the population: peasants.

The feudal system was based on a kind of protection system (or even protection racket). A lord accepted pledges of loyalty, called a pledge of fealty, from other free men called his vassals; in return for their support in war he offered them protection and land-grants called fiefs. Each vassal had the right to extract wealth from his land, meaning the peasants who lived there, so that he could afford horses, armor, and weapons. In general, vassals did not have to pay their lords taxes; all tax revenue came from the peasants. Likewise, the Church itself was an enormously wealthy and powerful landowner, and Church holdings were almost always tax-exempt; bishops were often lords of their own lands, and every king worked closely with the Church's leadership in his kingdom.

This system arose because of the absence of other, more effective forms of government and the constant threat of violence posed by raiders. The system was never as neat and tidy as it sounds on paper; many vassals were lords of their own vassals, with the king simply being the highest lord. In turn, the problem for royal authority was that many kings had “vassals” who had more land, wealth, and power than they did; it was very possible, even easy, for powerful nobles to make war against their king if they chose to do so. It would take centuries before the monarchs of Europe consolidated enough wealth and power to dominate their nobles, and it certainly did not happen during the Middle Ages.

One (amusing, in historical hindsight) method that kings would use to punish unruly vassals was simply visiting them and eating them out of house and home - the traditions of hospitality required vassals to welcome, feed, and entertain their king for as long as he felt like staying. Nevertheless, there are many instances in medieval European history in which a powerful lord simply usurped the throne, defeated the former king's forces, and became the new king. Even though the rulership of a given king was always understood to be the will of God, new kings had little trouble arguing that God obviously favored them over the former monarch.

Ultimately, the feudal system represented a “warlord” system of political organization, in many cases barely a step above anarchy. Pledges of loyalty between lords and vassals served as the only assurance of stability, and those pledges were violated countless times throughout the period. The Church tried to encourage lords to live in accordance with Christian virtue, but the fact of the matter was that it was the nobility’s vocation, their very social role, to fight, and thus all too often “politics” was synonymous with “armed struggle” during the Middle Ages.

Medieval Europe: What is Feudalism Essay Example

Feudalism was the major social and political order in medieval Europe. It was later developed as power passed from things to local lords. “Feudalism brought together two powerful groups: lords and vassals.” (“You decide… Feudalism: Good or Bad?”). Feudalism provided people with protection and safety by establishing a stable social order. It is a highly decentralized form of government that is based on rights and obligations.

There were different levels of the feudal system. Starting off with the monarchs, they had the highest authority. The monarchs had all the authority and kept most of the land for themselves. They gave fiefs to the most important nobles who became his vassals. Next, there were Nobles and Church Officials. When Monarch’s were to give them land, in return, they swore an oath of loyalty to supply the king with knights for war. Next, were the knights. The knights were to fight in the king’s wars. Lords would supply the king with them for wars. Lastly, there were Peasants and Serfs. They were in the lowest class of the social structure. Lords would sometimes rent land to the peasants who worked for them. But, most peasants were serfs. Serfs would usually work, but weren’t considered slaves. They couldn’t leave the lord’s land without permission, and had to farm their fields in exchange for a small plot of their own land.

Feudalism can be interpreted as either good, or bad. Personally, I believe it was good and bad. But it was more so good than bad. First, “Feudalism protected the communities from the violence and warfare that broke out after the fall of Rome and the collapse of strong central government in Western Europe. Feudalism secured Western Europe’s society and kept out powerful invaders.” (Packet, “You decide… Feudalism: Good or Bad”?) Feudalism had a strong impact on this time because of all the corruption and warfare going around near them. It ensured the community was safer, and the invaders were kept out. Next, feudalism did not allow one person to gain all the power. Instead, it was shared amongst themselves with many different people and groups. The feudal system also allowed rights to most people, however the monarchs had a little more power than everybody else. Knights were used for war, but peasants weren’t looked at as slaves, they worked for small amounts of land. But, like I said, this system had its downside. This system didn’t allow people to move up in the society. If a person was born a peasant or serf, they had stayed there, and were never allowed to move up.

As we can conclude, Feudalism can be looked on either way. We see how it provided protection to people, but also didn’t allow people to ever move from where they were born into. The system helped protect people from invaders and protected them from violent acts such as Warfare, but also favored monarchs and lords power above most. We looked at what feudalism was, how it worked, and how it is Good, but also a reason why people can see it as a “not so great” idea.

Related Samples

- The Biggest Tragedy: Holocaust Essay Example

- History Essay Sample on The World War II: The United States And The Soviet Union

- Life of Medieval Knights Essay Example

- Essay Sample about Ida B. Wells: Journalist and Suffragist in the Time of Jim Crow

- Essay Sample about Causes of World War II

- Reconstruction Essay Example

- The Atlantic World: Essay on Slavery, Migration, and Imagination

- John F Kennedy Essay Example

- Wollstonecraft Intellectually Impacts Society (Essay Example)

- Is Brutus Tragic Hero Essay Example 2

Didn't find the perfect sample?

You can order a custom paper by our expert writers

- STS NEWSFEED

- VLM NEWSFEED

- Alternative News

- Investigative Journalists

- Free-Speech

- Health Freedom

- Consciousness

- Free Speech Media

- Red-Pill Documentaries

- Red-Pill Series

- Medicine (UN) Censored

- Vaccine Series

- Sign in / Join

The Great Awakening – A Documentary About The State & Fate…

Zeitgeist: Exposing The Invisible Chains Globalist Use To Enslave The World!

Bitcoin & The Banking Crisis: Caitlin Long

SGT Report: THE MOST DEADLY PRODUCT IN MEDICINAL HISTORY — Dr….

The Destruction of Memory & False History- Jay Weidner & Howdie…

World issues, pros and cons of feudalism.

Feudalism is a system of government that some look back upon quite fondly. Instead of having one large nation-state, a country would be divided into different ruling regions. Each region had a noble ruler and these nobles would then pledge their allegiance to a king, queen or other ruling entity. This creates a national allegiance and a regional allegiance that was very powerful for each individual.

What are the pros and cons of feudalism? Is this a system that could still potentially work today, or has its time come and gone? Here are a few of the key points to consider.

What Are the Pros of Feudalism?

1. It is a very self-sufficient system of governing. Each area had its own rulers assigned to it. Each ruler had their own classes of people in the region, from workers to soldiers, that helped to provide for each other. Trades only happened periodically, which kept the economy stable locally. In feudalism, there was always a job available for someone who wanted to work.

2. It provided a system of co-existence. The working classes required protection from other regions who might want to take what they had. The noble classes could provide this in exchange for a portion of the goods and services that the working class created. The exchange gave the nobles riches and the working classes a chance to live their lives in the way they wished without much interference beyond their duties to the region.

3. It allowed for a simplistic chain of command. There was no red tape in feudalism. Decrees were issued from the top and implemented on the way down. Because every region was different, people could pledge their loyalty to certain nobles that fit in with what they wanted to accomplish in life. This made it easier to avoid conflict because different nobles in the same region wouldn’t be issuing conflicting orders.

4. Land management was incredibly easy. Because every region had to sustain itself locally, land management had to be maximized. This meant that regions were more productive overall because instead of worrying about ownership, the lands could just be managed by the working class and maintained by the noble class. Because everything depended on quality land production, an emphasis on resources was always placed on land use.

What Are the Cons of Feudalism?

1. It was easy to abuse the power given. Because the chain of command started at the very top, the power of that position made it easy to abuse everyone else within that region. People could uproot to a new noble, but would often be threatened with death or tracked down if this happened. This could make life very difficult for the working classes.

2. One bad season could end everything. If there was one bad growing system in a region, then the entire ruling system in that area could come tumbling down. That’s the problem when everything is locally emphasized without much trade. This issue still exists today when nations decide to isolate instead of create trading relationships.

3. It was a very isolated existence. Most people in a feudalism system would rarely travel outside of their region. This was even true of the noble class unless there was a need to expand or defend the territory. It created a system of isolated regions, even within the same overall kingdom, that could develop some very distinct differences that had the potential to create a civil conflict. Even when travel did happen, people from neighboring regions were often treated with hostility instead of welcoming arms. Suspicion was everywhere.

4. Freedoms that were obtained were very rarely free. In order for the working class to gain access to land to work or own, they had to pledge their support to their noble, their king, or both. In return for this privilege, they had to respond to requests for troops when needed, provide a portion of their crops or work as taxes, and bear additional expenses for war or defense when called upon. If there wasn’t enough money available to pay the needed taxation, then they could lose their land, be thrown into prison, or even executed.

The pros and cons of feudalism make it difficult to say whether it is a beneficial or detrimental system of ruling. Much depended on how it was implemented and what the ethics of the nobility happened to be. Eventually people want something more valuable than land for their services and that is what causes feudalism to break down.

Crystal Lombardo is a contributing editor for Vision Launch. Crystal is a seasoned writer and researcher with over 10 years of experience. She has been an editor of three popular blogs that each have had over 500,000 monthly readers.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

The Story Of Your Enslavement

Enough is Enough, Says Russia

New World Order Desperate as Plan Falls Apart – Martin Armstrong

The Great Awakening – A Documentary About The State & Fate...

Is Free Energy Possible In 2023? The Liberty Engine: Perpetual Free...

They Are Trying To Normalize SADS Like They Did With SIDS....

How is It Possible That So Many People Still Believe That...

POPULAR CATEGORIES

- World Issues 715

- Crowdfunding 320

- Articles 309

- Inventors 288

- Business 140

- Home Sidebar 106

Pin It on Pinterest

82 Feudalism Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best feudalism topic ideas & essay examples, 👍 good essay topics on feudalism, ✅ simple & easy feudalism essay titles, ❓ questions about feudalism.

- Feudalism System of Western Europe in the Middle Ages Although there was the presence of the king, the position was irrelevant in the country. The vassals, as mentioned in the introduction, were the persons who paid homage and pledged allegiance to the lords in […]

- The Development of Feudalism and Manorialism in the Middle Ages Manorialism on the other hand refers to an important component of feudal community which entailed the principles used in organizing economy in the rural that was born in the medieval villa system. We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts 808 writers online Learn More

- Susan Reynolds’s Attack on the Concepts of Feudalism Supported by F.L. Ganshof and Marc Bloch However, in her book Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted, Susan Reynolds states that it is inappropriate to follow the narrow discussion of feudalism with references to the concepts of vassalage and fiefs, and […]

- The Fall of Roman Empire and the Rise of Feudalism Therefore, to German, the fall of the Roman Empire is significant for some of the aspects of feudalism are still present in German societies.

- Digital Feudalism: Capitalists Exploit Laborers The examination of the life cycle of a single Amazon Echo speaker reveals deep interconnections between the literal hollowing out of the earth’s materials and the data capture and monetization of human communication practices in […]

- From the Fall of the Holy Roman Empire to Feudalism This remnant from the past reflects the time when the Franks took over the Burgundians and influenced both the language and culture of the Burgundians.

- Major Historiographic Views on Feudalism The history of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance continues to attract the attention of many contemporary historians. This is one of the points that should be considered.

- The Role of Women on Feudalism: Nobility, Peasantry, and the Church

- The Cultural Significance of Feudalism: Literature, Music, and Dance

- Capitalism and Feudalism: The Lowell System

- Key Differences Between Feudalism and Capitalism

- Feudalism and Powerful Warrior Landlords

- Comparing and Contrasting Haritan and Japanese Feudalism

- The Impact of Feudalism on Medieval Art and Architecture

- Feudalism and Court Services Vassals

- The Feudalism and Manorialism Unraveled

- Political and Economic Characteristics of Feudalism

- The Role of the Black Death in the Decline of Feudalism

- Feudalism and Feudal States From Europe After the Breakup

- Similarities Between European Feudalism in the Middle Ages and the Caste System of India

- The Feudal System in Central Asia: Comparative Analysis With European Feudalism

- Lives Sold Dear: Chivalry and Feudalism in the “Song of Roland”

- The Dark Ages and the Feudalism

- The Role of Feudalism in the Crusades and the Reconquista

- The Impact of Feudalism on the Development of Capitalism

- The Role of Feudalism in Medieval Medicine and Health Care

- The Impact of Feudalism on the Development of Modern International Relations

- Literature and the Transition From Middle Ages Feudalism to the Industrial Era

- Main Reasons for the Fall of Feudalism

- The Role of Feudalism in the Formation of Medieval Cities

- Feudalism and New Social Order

- The Impact of Feudalism on the Development of Nationalism in Europe

- The Military System of Feudalism: Knights and Chivalry

- The Historical Context of Feudalism: Origins and Evolution

- The Rise and Fall of Feudalism

- Feudalism: The Rights and Responsibilities of Lords and Vassals

- The Rise of Feudalism in Eastern Europe

- The Differences Between Feudalism Before and After the Norman Conquest

- Feudalism and Its Effects on Society

- Comparing and Contrasting Japanese Feudalism to Western European Feudalism During the Middle Ages

- The Transition From Feudalism to the Renaissance

- The Military Government: The Oldest Form of Governance Since the Feudalism

- The Influence of Feudalism on the Development of Democracy in Europe

- How Revolutionaries Change System Government-Based Monarchy Feudalism?

- Feudalism: Social Class and National Government

- The Impact of Feudalism on Trade and Commerce in Medieval Europe

- The Economic System of Feudalism: Manorialism and Serfdom

- The Impact of Feudalism on the Development of International Law

- Feudal System: Medieval Life and Feudalism

- The Impact of Feudalism on the Development of Modern Science

- The Feudal System in America: Comparative Analysis With European Feudalism

- The Social and Economic Changes in Feudalism in the 14th Century

- The Role of Feudalism in the Formation of Modern Nation-States

- The Impact of Feudalism on the Development of Human Rights

- The History and Impact of Feudalism in Europe Between the 8th and 9th Century

- The Social Hierarchy of Feudalism: Nobility, Clergy, and Peasantry

- Pensions and Lifetime Jobs: The New Industrial Feudalism Revisited

- Are There More Similarities Between Feudalism and Capitalism Than We’d Like to Admit?

- Was Feudalism an Effective Form of Government?

- What Events Led to the Decline of Feudalism?

- Did Feudalism Create Capitalism?

- How Did Centralized Feudalism Under the Tokugawa Shoguns Unite Japan?

- What Made Feudalism So Unfair?

- How Long Did Feudalism Last?

- What Economic System Started to Replace Feudalism During the Time of the Renaissance?

- Why Did Russian Feudalism Last So Much Longer Than Its Western European Counterparts?

- How Is Feudalism and Manorialism Connected?

- Did Karl Marx Believe in Feudalism?

- What Was the Main Problem With Feudalism?

- How Did Feudalism Begin and End?

- Why Did Europe Shift From Feudalism to Capitalism?

- How Did Feudalism and the Manor Economy Emerge and Shape Medieval Life?

- What Are the Theories of Feudalism?

- How Did the Tokugawas Set Up Centralized Feudalism?

- What Was the Basic Structure of Feudalism in Western Europe in the 8th and 9th Centuries?

- Is Capitalism Better Than Feudalism?

- Which Country Abolished Feudalism First?

- How Did Society Change From Feudalism to Renaissance Times?

- What Was the Social and Economic Impact of Feudalism?

- How Did Feudalism Change History?

- What Is the Structure of Feudalism?

- How Did Feudalism Impact Life in the Middle Ages?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, March 20). 82 Feudalism Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/feudalism-essay-topics/

"82 Feudalism Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 20 Mar. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/feudalism-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '82 Feudalism Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 20 March.

IvyPanda . 2023. "82 Feudalism Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 20, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/feudalism-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "82 Feudalism Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 20, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/feudalism-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "82 Feudalism Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 20, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/feudalism-essay-topics/.

- Anarchy Titles

- Social Class Research Ideas

- World History Topics

- Crusades Research Topics

- Ancient History Topics

- Imperialism Questions

- Roman Empire Ideas

- Byzantine Empire Essay Ideas

- European History Essay Titles

- British Empire Ideas

- Joan Of Arc Topics

- Renaissance Essay Titles

- Colonialism Essay Ideas

- Black Death Ideas

- Monarchy Research Topics

Using Concepts in Medieval History pp 15–48 Cite as

Feudalism: Reflections on a Tyrannical Construct’s Fate

- Elizabeth A. R. Brown 4

- First Online: 24 January 2022

561 Accesses

In this article I reflect on feudalism and the attack I launched in 1974 against it and such similar constructs as feudal system, feudal society, and feudal monarchy. I first review the reasons for my campaign and its timing. Re-evaluating the extent and gravity of the disapproval the term had long elicited, I reconsider the relationship between my uncompromising assault and earlier opposition to feudalism. Before examining the reactions to the article, positive and negative, I treat the feudal constructs’ appeal and powers of endurance, and the cognitive roots of their advocates’ attachment to them. In appraising the article’s reception, I discuss Susan Reynolds’s book, Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted , published in 1994, and the similarities and differences between our approaches to the feudal constructs and to medieval society and politics. In a final section I assess the diminished fidelity that feudalism has commanded since 2000, and the progressive waning of the feudal constructs’ influence on studies of medieval Europe, which focus increasingly on the complexities of its evolution. The conclusion reiterates the call I issued in 1974 to renounce the constructs and cautiously forecasts their imminent demise, except as evidence of the styles of conceptualization that led their sixteenth- and seventeenth-century fabricators to invent them.

- Feudal system

- Thomas N. Bisson

- Georges Duby

- Richard W. Southern

- Fredric L. Cheyette

- Ermengard of Narbonne

- Susan Reynolds

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

American Historical Review , 79:4 (1974), 1063–88. I am grateful for encouragement, suggestions, and corrections to Allan Appel, Suzanne Boorsch, Rowan Dorin, Theodore Evergates, Geoffrey Koziol, Susanne Roberts, M. Alison Stones, Thomas N. Tentler, and, particularly, Richard C. Famiglietti and Emily Zack Tabuteau. I am indebted as well for exchanges I have had over the years with Theodore Evergates, the late Susan Reynolds, and Stephen D. White, as well as Walter Goffart, the late Howard Kaminsky, and, particularly, the late Fredric L. Cheyette. Lucy L. Brown and Herbert H. Schaumberg have discussed and debated with me my ideas about the development of the physical and social sciences, and the relevance of experimental studies of human cognition to attitudes toward the feudal constructs. Jackson Armstrong, Peter Crooks, and Andrea Ruddick have been models of editorial patience and efficiency.

Susan Reynolds, Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994).

At Swarthmore College, Professor Mary Albertson introduced me to Eileen Powers’ masterpiece, Medieval People (London: Methuen & Co., 1924), a seventh edition of which was published in 1939, and a tenth in 1963. In 1957, four years after its publication, when I was in my third year of graduate school, I acquired a now ragged copy of Isaiah Berlin, The Hedgehog and the Fox , which was based on an essay that appeared in 1951. See below, n. 37 and the accompanying text.

M. Bloch, Apologie pour l’histoire ou métier d’historien , ed. Étienne Bloch (Paris: Armand Colin, 1993). I treasure the copy I bought in 1957 of The Historian’s Craft , trans. Peter Putnam with an introduction by Joseph R. Strayer (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1954).

M. Bloch, La société féodale. La formation des liens de dépendance (L’Évolution de l’humanité, synthèse collective, 34:1; Paris: Albin Michel, 1939), and La société féodale. Les classes et le gouvernement des hommes (Paris: Albin Michel, 1940) (the second part of the volume in Henri Berr’s series). In the English translation that appeared twenty years later the two divisions were rendered as ‘The growth of ties of dependence’, and ‘Social classes and political organization’: Feudal Society , trans. L.A. Manyon (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961). I discussed Bloch’s mixed attitude toward the constructs in ‘Tyranny’, 1069–1070, and also in ‘Reflections on Feudalism: Thomas Madox and the Origins of the Feudal System in England’, in Belle S. Tuten and Tracey L. Billado (eds), Feud, Violence and Practice: Essays in Medieval Studies in Honor of Stephen D. White (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010), 135–55, at 136, 138–41.

Richard W. Southern, The Making of the Middle Ages (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1953; cf. Brown, ‘Tyranny’, 1080–1; Georges Duby, La société aux XI e et XII e siècles dans la région mâconnaise (Bibliothèque générale de l’École pratique des Hautes Études, 6 e section; Paris: Armand Colin, 1953; reprinted, with different pagination, as Bibliothèque générale de l’École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales; Paris: S.E.V.P.E.N., 1971); see Brown, ‘Tyranny’, 1073–4, 1081–4. Fredric L. Cheyette commented on Southern and Duby, in ‘George Duby’s Mâconnais after Fifty Years: Reading It Then and Now’, Journal of Medieval History , 28 (2002), 291–317, at 293.

Notable among them are Jacques Flach (1846–1919), Les origines de l’ancienne France , 4 vols (Paris: L. Larose et al., 1886–1917), on whom see Alain Guerreau, Le féodalisme: un horizon théorique (Paris: Le Sycomore, 1980), 51–5; and Alain Guerreau ‘Fief, féodalité, féodalisme. Enjeux sociaux et réflexion historienne’, Annales : Économies – Sociétés – Civilisations , 45:1 (1990), 137–66; Émile Lesne, ‘Les diverses acceptations du terme “beneficium” du VIII e au IX e siècle (Contribution à l’étude des origines du bénéfice ecclésiastique)’, Revue historique du droit français et étranger , 4th ser., 3 (1924), 5–56; Charles Edwin Odegaard, Vassi and Fideles in the Carolingian Empire (Harvard Historical Monographs, 19; Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1945); Léo Verriest, Institutions médiévales. Introduction au Corpus des records de coutumes et des lois de chefs-lieux de l’ancien comté de Hainaut, 2 vols (Société des bibliophiles belges séant à Mons, Publications, 41–42; Mons-Frameries: Union des imprimeries, 1946); Léo Verriest, Questions d’histoire des institutions médiévales. Noblesse. Chevalerie. Lignages. Condition des biens et des personnes. Seigneurie. Ministérialité. Bourgeoisie. Échevinages (Brussels: Chez l’Auteur, 1959/1960); Jan Dhondt, Études sur la naissance des principautés territoriales en France (IX e – X e siècle) (Werken Uitgegeven door de Faculteit van de Wijsbegeerte en Letteren, Rijksuniversiteit te Gent, 102; Bruges: ‘De Tempel’, 1948); Yvonne Bongert, Recherches sur les cours laiques du X e au XII e siècle (Paris: A. & J. Picard, 1949); Jean-François Le-marignier, ‘Les fidèles du roi de France’, in Recueil de travaux offert à M. Clovis Brunel …, 2 vols (Mémoires et documents publiés par la Société de l’École des chartes, 12; Paris: Société de l’École des chartes, 1955), II, 138–62. In his study A Rural Society in Medieval France: The Gâtine of Poitou in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries (Johns Hopkins University Press Studies in Historical and Political Science, ser. 82, 1; Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1964), 72, 94, 96, George Beech invoked ‘feudalism’ in studying the nobility and drew on Marc Bloch’s La société féodale to flesh out ‘the few scraps of information’ that he had found, while cautioning that ‘the lacunae of the documents … cast a shadow of uncertainty on any assertion’, and making clear ‘that birth was a more important criterion for nobility than the ability to fight’.

William Huse Dunham, Jr., review of Bryce D. Lyon, From Fief to Indenture: The Transition from Feudal to Non-Feudal Contract in Western Europe (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1956), in Speculum 33:2 (1958), 300–4, at 304. Citing the Oxford English Dictionary , Dunham dated to 1776 the appearance of the term ‘feudal System’ and to 1839 the first use of ‘feudalism’, although in fact Thomas Madox (1666–1727) used the first expression, and in 1771 John Whitaker (1735–1808) employed the word ‘feudalism’ and introduced the notion of the feudal pyramid; see my article, ‘Reflections on Feudalism’, esp. 145n. 35, and 147–49, for the dates.

F.W. Maitland, The Constitutional History of England: A Course of Lectures , ed. H A. L. Fisher (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1st edn., 1908), 142–3; see also my essay, ‘Reflections on Feudalism’, 138–41.

Frederick Pollock and Frederic William Maitland, The History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I , 2nd edn., 2 vols (first pub. 1898; ed. S. F. C. Milson; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968), I, 66, and see the following pages for Maitland’s continued use of the term and his suggestion that the term ‘feodo-vassalism’ might be preferable to ‘feudalism’. See also Maitland’s Domesday Book and Beyond: Three Essays in the Early History of England (first pub. 1897; London: Collins, 1960), esp. part 8 of Essay I (‘Domesday Book’), 189–212 (‘The Feudal Superstructure’), at 211 (writing of ‘feudalism’ and ‘vassalism’).

F. M. Stenton, The First Century of English Feudalism 1066–1166. Being the Ford Lectures Delivered in the University of Oxford in Hilary Term 1929 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1932; 2nd edn. 1961), 214–15 (216–17 in the 2nd edn.). For the terms I mention, see ibid., (2nd edn., 1961), vii, ix, 8–9, 12–14, 16–17, 27, 33, 35–6, 145, and 223.

V.H. Galbraith, 1066 and All That: Norman Conquest Commemoration Lecture Delivered to the Society on 14th October, 1966 (Leicester: The Leicestershire Archæological and Historical Society, 1967), 3, who remarked that in 1870 Freeman questioned ‘Did the Feudal System ever exist anywhere?’ (without, however, pursuing the implications of the question, I should note) and pointed out that Richard Southern avoided ‘Feudalism, yet without affecting [his book’s] popularity’. Like the others, Galbraith himself did not repudiate the feudal terms, declaring (ibid., 5) that in Domesday Book we find ‘the introduction of the’Feudal System’ into England’. See Edward Augustus Freeman, The History of the Norman Conquest of England, its Causes and its Results , 6 vols, 2nd edn. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1870), I, 90–92; the preface is dated 4 January 1867 (ibid., xii).

Henry Alfred Cronne, The Reign of Stephen 1135–54. Anarchy in England (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1970), 4–8, where Cronne provided useful historiographical background and commentary. Cronne advised (ibid., 8), ‘Let us rather study the characteristics of society as we find it revealed in the available sources of information, without bothering too much about the exact shade of meaning to be attached to the term “feudal” in relation to it’.

Fredric L. Cheyette, ‘Some Notations on Mr. Hollister’s “Irony”’, Journal of British Studies , 5 (1965), 1–14 (at 2 and 4); and ibid., 2 (1963), 1–26, for Hollister’s article. Cheyette commented on Hollister’s other publications and the debates they stimulated in ‘Some Notations’, 1–2, esp. notes 1–4.

Cheyette, ‘Some Notations’, 5. For Susan Reynolds’s attention to the relationship among word, concept, and phenomenon, see below, n. 77.

Cheyette, ‘Some Notations’, 2.

Cheyette, ‘Some Notations’, 12.

Cheyette, ‘Some Notations’, 13 (‘in a sense, there was not one feudalism; there were a great many’, suggesting in n. 33 that in 1962 Strayer perhaps ‘[did] not go far enough’ in positing ‘two feudalisms’); see below following n. 40, for the similar proposition that Thomas N. Bisson later made.

Cheyette, ‘Some Notations’, 14.

F. L. Cheyette, Lordship and Community in Medieval Europe: Selected Readings (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1968). In Susan Reynold’s ‘Fiefs and Vassals after Twelve Years’, in Sverre Bagge, Michael H. Gelting and Thomas Lindkvist (eds), Feudalism, New Landscapes of Debate (The Medieval Countryside, 5; Turnhout: Brepols, 2011), 15–26, at 15, she wrongly wrote that Cheyette’s book was published a year after my article (and thus in 1975), rather than six years before my essay, which both Cheyette and his anthology greatly influenced. Reynolds’s essay and others in the volume were based on papers delivered at a conference on feudalism in Bergen in 2006, on which see below, at n. 108 and following.

Cheyette, Lordship and Community , vii, 1–5.

Exceptions are the essays by Édouard Perroy and William Huse Dunham, Jr., and one of the two essays contributed by Duby and one of Joshua Prawer’s, whose authors use such terms as ‘feudal régime’, ‘feudalism’, and ‘feudality’: Cheyette, Lordship and Community, 137–79, 217–39.

Cheyette, Lordship and Community , 10.

Cheyette, ‘“Feudalism”: A Memoir and an Assessment’, in Tuten and Billado (eds), Feud, Violence and Practice , 119–33, at 120, where Cheyette singled out Stephen White as his ‘welcome and learned companion’, even though in my view White’s commitment to the crusade against the constructs has been sporadic: Brown, ‘Reflections on Feudalism’, 135–8, and n. 121 below.

Published in the 1 February 1969 issue of The New Yorker (on 26), the cartoon appeared on the cover of the issue of The American Historical Review in which my article was published. Cf. the cartoon that Jacob Adam Katzenstein contributed to The New Yorker , the issue dated 5 and 12 August 2019 (19), which shows a crowned princess and a jongleur companion walking hand-in-hand toward an imposing castle as she beseeches him, ‘Try not to bring up feudalism with my dad tonight’.

Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962); 2nd edn. (International Encyclopedia of Unified Science, Foundations of the Unity of Science, 2, part 2; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970); Michel Foucault, Les mots et les choses (Paris: Gallimard, 1966), translated with a special foreword as The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (New York: Pantheon, 1971).

Brown, ‘Tyranny’, 1063–4.

Cf. the comments of Richard Abels, in ‘The Historiography of a Construct: “Feudalism” and the Medieval Historian’, History Compass , 73 (2009), 1008–31, at 1022–23.

Brown, ‘Tyranny’, 1066–80.

See n. 6 above.