An Essay on Criticism Summary & Analysis by Alexander Pope

- Line-by-Line Explanation & Analysis

- Poetic Devices

- Vocabulary & References

- Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme

- Line-by-Line Explanations

Alexander Pope's "An Essay on Criticism" seeks to lay down rules of good taste in poetry criticism, and in poetry itself. Structured as an essay in rhyming verse, it offers advice to the aspiring critic while satirizing amateurish criticism and poetry. The famous passage beginning "A little learning is a dangerous thing" advises would-be critics to learn their field in depth, warning that the arts demand much longer and more arduous study than beginners expect. The passage can also be read as a warning against shallow learning in general. Published in 1711, when Alexander Pope was just 23, the "Essay" brought its author fame and notoriety while he was still a young poet himself.

- Read the full text of “From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing”

The Full Text of “From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing”

1 A little learning is a dangerous thing;

2 Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring:

3 There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

4 And drinking largely sobers us again.

5 Fired at first sight with what the Muse imparts,

6 In fearless youth we tempt the heights of Arts,

7 While from the bounded level of our mind,

8 Short views we take, nor see the lengths behind,

9 But, more advanced, behold with strange surprise

10 New, distant scenes of endless science rise!

11 So pleased at first, the towering Alps we try,

12 Mount o'er the vales, and seem to tread the sky;

13 The eternal snows appear already past,

14 And the first clouds and mountains seem the last;

15 But those attained, we tremble to survey

16 The growing labours of the lengthened way,

17 The increasing prospect tires our wandering eyes,

18 Hills peep o'er hills, and Alps on Alps arise!

“From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing” Summary

“from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” themes.

Shallow Learning vs. Deep Understanding

- See where this theme is active in the poem.

Line-by-Line Explanation & Analysis of “From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing”

A little learning is a dangerous thing; Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring: There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain, And drinking largely sobers us again.

Fired at first sight with what the Muse imparts, In fearless youth we tempt the heights of Arts, While from the bounded level of our mind, Short views we take, nor see the lengths behind,

But, more advanced, behold with strange surprise New, distant scenes of endless science rise!

Lines 11-14

So pleased at first, the towering Alps we try, Mount o'er the vales, and seem to tread the sky; The eternal snows appear already past, And the first clouds and mountains seem the last;

Lines 15-18

But those attained, we tremble to survey The growing labours of the lengthened way, The increasing prospect tires our wandering eyes, Hills peep o'er hills, and Alps on Alps arise!

“From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing” Symbols

The Mountains/Alps

- See where this symbol appears in the poem.

“From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing” Poetic Devices & Figurative Language

Alliteration.

- See where this poetic device appears in the poem.

Extended Metaphor

“from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” vocabulary.

Select any word below to get its definition in the context of the poem. The words are listed in the order in which they appear in the poem.

- A little learning

- Pierian spring

- Bounded level

- Short views

- The lengthened way

- See where this vocabulary word appears in the poem.

Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme of “From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing”

Rhyme scheme, “from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” speaker, “from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” setting, literary and historical context of “from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing”, more “from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” resources, external resources.

The Poem Aloud — Listen to an audiobook of Pope's "Essay on Criticism" (the "A little learning" passage starts at 12:57).

The Poet's Life — Read a biography of Alexander Pope at the Poetry Foundation.

"Alexander Pope: Rediscovering a Genius" — Watch a BBC documentary on Alexander Pope.

More on Pope's Life — A summary of Pope's life and work at Poets.org.

Pope at the British Library — More resources and articles on the poet.

LitCharts on Other Poems by Alexander Pope

Ode on Solitude

Everything you need for every book you read.

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Analysis of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism

Analysis of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on July 8, 2020 • ( 1 )

An Essay on Criticism (1711) was Pope’s first independent work, published anonymously through an obscure bookseller [12–13]. Its implicit claim to authority is not based on a lifetime’s creative work or a prestigious commission but, riskily, on the skill and argument of the poem alone. It offers a sort of master-class not only in doing criticism but in being a critic:addressed to those – it could be anyone – who would rise above scandal,envy, politics and pride to true judgement, it leads the reader through a qualifying course. At the end, one does not become a professional critic –the association with hired writing would have been a contaminating one for Pope – but an educated judge of important critical matters.

But, of the two, less dang’rous is th’ Offence, To tire our Patience, than mislead our Sense: Some few in that, but Numbers err in this, Ten Censure wrong for one who Writes amiss; A Fool might once himself alone expose, Now One in Verse makes many more in Prose.

The simple opposition we began with develops into a more complex suggestion that more unqualified people are likely to set up for critic than for poet, and that such a proliferation is serious. Pope’s typographically-emphasised oppositions between poetry and criticism, verse and prose,patience and sense, develop through the passage into a wider account of the problem than first proposed: the even-handed balance of the couplets extends beyond a simple contrast. Nonetheless, though Pope’s oppositions divide, they also keep within a single framework different categories of writing: Pope often seems to be addressing poets as much as critics. The critical function may well depend on a poetic function: this is after all an essay on criticism delivered in verse, and thus acting also as poetry and offering itself for criticism. Its blurring of categories which might otherwise be seen as fundamentally distinct, and its often slippery transitions from area to area, are part of the poem’s comprehensive,educative character.

Literary Criticism of Alexander Pope

Addison, who considered the poem ‘a Master-piece’, declared that its tone was conversational and its lack of order was not problematic: ‘The Observations follow one another like those in Horace’s Art of Poetry, without that Methodical Regularity which would have been requisite in a Prose Author’ (Barnard 1973: 78). Pope, however, decided during the revision of the work for the 1736 Works to divide the poem into three sections, with numbered sub-sections summarizing each segment of argument. This impluse towards order is itself illustrative of tensions between creative and critical faculties, an apparent casualness of expression being given rigour by a prose skeleton. The three sections are not equally balanced, but offer something like the thesis, antithesis, and synthesis of logical argumentation – something which exceeds the positive-negative opposition suggested by the couplet format. The first section (1–200) establishes the basic possibilities for critical judgement;the second (201–559) elaborates the factors which hinder such judgement;and the third (560–744) celebrates the elements which make up true critical behaviour.

Part One seems to begin by setting poetic genius and critical taste against each other, while at the same time limiting the operation of teaching to those ‘who have written well ’ ( EC, 11–18). The poem immediately stakes an implicit claim for the poet to be included in the category of those who can ‘write well’ by providing a flamboyant example of poetic skill in the increasingly satiric portrayal of the process by which failed writers become critics: ‘Each burns alike, who can, or cannot write,/Or with a Rival’s, or an Eunuch ’s spite’ ( EC, 29–30). At the bottom of the heap are ‘half-learn’d Witlings, num’rous in our Isle’, pictured as insects in an early example of Pope’s favourite image of teeming, writerly promiscuity (36–45). Pope then turns his attention back to the reader,conspicuously differentiated from this satiric extreme: ‘ you who seek to give and merit Fame’ (the combination of giving and meriting reputation again links criticism with creativity). The would-be critic, thus selected, is advised to criticise himself first of all, examining his limits and talents and keeping to the bounds of what he knows (46-67); this leads him to the most major of Pope’s abstract quantities within the poem (and within his thought in general): Nature.

First follow NATURE, and your Judgment frame By her just Standard, which is still the same: Unerring Nature, still divinely bright, One clear, unchang’d, and Universal Light, Life, Force, and Beauty, must to all impart, At once the Source, and End, and Te s t of Art.

( EC, 68–73)

Dennis complained that Pope should have specified ‘what he means by Nature, and what it is to write or to judge according to Nature’ ( TE I: 219),and modern analyses have the burden of Romantic deifications of Nature to discard: Pope’s Nature is certainly not some pantheistic, powerful nurturer, located outside social settings, as it would be for Wordsworth,though like the later poets Pope always characterises Nature as female,something to be quested for by male poets [172]. Nature would include all aspects of the created world, including the non-human, physical world, but the advice on following Nature immediately follows the advice to study one’s own internal ‘Nature’, and thus means something like an instinctively-recognised principle of ordering, derived from the original,timeless, cosmic ordering of God (the language of the lines implicitly aligns Nature with God; those that follow explicitly align it with the soul). Art should be derived from Nature, should seek to replicate Nature, and can be tested against the unaltering standard of Nature, which thus includes Reason and Truth as reflections of the mind of the original poet-creator, God.

In a fallen universe, however, apprehension of Nature requires assistance: internal gifts alone do not suffice.

Some, to whom Heav’n in Wit has been profuse, Want as much more, to turn it to its use; For Wit and Judgment often are at strife, Tho’ meant each other’s Aid, like Man and Wife.

( EC, 80–03)

Wit, the second of Pope’s abstract qualities, is here seamlessly conjoined with the discussion of Nature: for Pope, Wit means not merely quick verbal humour but something almost as important as Nature – a power of invention and perception not very different from what we would mean by intelligence or imagination. Early critics again seized on the first version of these lines (which Pope eventually altered to the reading given here) as evidence of Pope’s inability to make proper distinctions: he seems to suggest that a supply of Wit sometimes needs more Wit to manage it, and then goes on to replace this conundrum with a more familiar opposition between Wit (invention) and Judgment (correction). But Pope stood by the essential point that Wit itself could be a form of Judgment and insisted that though the marriage between these qualities might be strained, no divorce was possible.

Nonetheless, some external prop to Wit was necessary, and Pope finds this in those ‘RULES’ of criticism derived from Nature:

Those RULES of old discover’d, not devis’d, Are Nature still, but Nature Methodiz’d; Nature, like Liberty , is but restrain’d By the same Laws which first herself ordain’d.

( EC, 88–91)

Nature, as Godlike principle of order, is ‘discover’d’ to operate according to certain principles stated in critical treatises such as Aristotle’s Poetics or Horace’s Ars Poetica (or Pope’s Essay on Criticism ). In the golden age of Greece (92–103), Criticism identified these Rules of Nature in early poetry and taught their use to aspiring poets. Pope contrasts this with the activities of critics in the modern world, where often criticism is actively hostile to poetry, or has become an end in itself (114–17). Right judgement must separate itself out from such blind alleys by reading Homer: ‘ You then whose Judgment the right Course would steer’ ( EC, 118) can see yourself in the fable of ‘young Maro ’ (Virgil), who is pictured discovering to his amazement the perfect original equivalence between Homer, Nature, and the Rules (130–40). Virgil the poet becomes a sort of critical commentary on the original source poet of Western literature,Homer. With assurance bordering consciously on hyperbole, Pope can instruct us: ‘Learn hence for Ancient Rules a just Esteem;/To copy Nature is to copy Them ’ ( EC, 139–40).

Despite the potential for neat conclusion here, Pope has a rider to offer,and again it is one which could be addressed to poet or critic: ‘Some Beauties yet, no Precepts can declare,/For there’s a Happiness as well as Care ’ ( EC, 141–2). As well as the prescriptions of Aristotelian poetics,Pope draws on the ancient treatise ascribed to Longinus and known as On the Sublime [12]. Celebrating imaginative ‘flights’ rather than representation of nature, Longinus figures in Pope’s poem as a sort of paradox:

Great Wits sometimes may gloriously offend, And rise to Faults true Criticks dare not mend; From vulgar Bounds with brave Disorder part, And snatch a Grace beyond the Reach of Art, Which, without passing thro’ the Judgment , gains The Heart, and all its End at once attains.

( EC, 152–7)

This occasional imaginative rapture, not predictable by rule, is an important concession, emphasised by careful typographic signalling of its paradoxical nature (‘ gloriously offend ’, and so on); but it is itself countered by the caution that ‘The Critick’ may ‘put his Laws in force’ if such licence is unjustifiably used. Pope here seems to align the ‘you’ in the audience with poet rather than critic, and in the final lines of the first section it is the classical ‘ Bards Triumphant ’ who remain unassailably immortal, leavingPope to pray for ‘some Spark of your Coelestial Fire’ ( EC, 195) to inspire his own efforts (as ‘The last, the meanest of your Sons’, EC, 196) to instruct criticism through poetry.

Following this ringing prayer for the possibility of reestablishing a critical art based on poetry, Part II (200-559) elaborates all the human psychological causes which inhibit such a project: pride, envy,sectarianism, a love of some favourite device at the expense of overall design. The ideal critic will reflect the creative mind, and will seek to understand the whole work rather than concentrate on minute infractions of critical laws:

A perfect Judge will read each Work of Wit With the same Spirit that its Author writ, Survey the Whole, nor seek slight Faults to find, Where Nature moves, and Rapture warms the Mind;

( EC, 233–6)

Most critics (and poets) err by having a fatal predisposition towards some partial aspect of poetry: ornament, conceit, style, or metre, which they use as an inflexible test of far more subtle creations. Pope aims for akind of poetry which is recognisable and accessible in its entirety:

True Wit is Nature to Advantage drest, What oft was Thought, but ne’er so well Exprest, Something, whose Truth convinc’d at Sight we find, That gives us back the Image of our Mind:

( EC, 296–300)

This is not to say that style alone will do, as Pope immediately makesplain (305–6): the music of poetry, the ornament of its ‘numbers’ or rhythm, is only worth having because ‘The Sound must seem an Eccho to the Sense ’ ( EC, 365). Pope performs and illustrates a series of poetic clichés – the use of open vowels, monosyllabic lines, and cheap rhymes:

Tho’ oft the Ear the open Vowels tire … ( EC , 345) And ten low Words oft creep in one dull Line … ( EC , 347) Where-e’er you find the cooling Western Breeze, In the next Line, it whispers thro’ the Trees … ( EC, 350–1)

These gaffes are contrasted with more positive kinds of imitative effect:

Soft is the Strain when Zephyr gently blows, And the smooth Stream in smoother Numbers flows; But when loud Surges lash the sounding Shore, The hoarse, rough Verse shou’d like the Torrent roar.

( EC, 366–9)

Again, this functions both as poetic instance and as critical test, working examples for both classes of writer.

After a long series of satiric vignettes of false critics, who merely parrot the popular opinion, or change their minds all the time, or flatter aristocratic versifiers, or criticise poets rather than poetry (384-473), Pope again switches attention to educated readers, encouraging (or cajoling)them towards staunchly independent and generous judgment within what is described as an increasingly fraught cultural context, threatened with decay and critical warfare (474–525). But, acknowledging that even‘Noble minds’ will have some ‘Dregs … of Spleen and sow’r Disdain’ ( EC ,526–7), Pope advises the critic to ‘Discharge that Rage on more ProvokingCrimes,/Nor fear a Dearth in these Flagitious Times’ (EC, 528–9): obscenity and blasphemy are unpardonable and offer a kind of lightning conductor for critics to purify their own wit against some demonised object of scorn.

If the first parts of An Essay on Criticism outline a positive classical past and troubled modern present, Part III seeks some sort of resolved position whereby the virtues of one age can be maintained during the squabbles of the other. The opening seeks to instill the correct behaviour in the critic –not merely rules for written criticism, but, so to speak, for enacted criticism, a sort of ‘ Good Breeding ’ (EC, 576) which politely enforces without seeming to enforce:

LEARN then what MORALS Criticks ought to show, For ’tis but half a Judge’s Task , to Know. ’Tis not enough, Taste, Judgment, Learning, join; In all you speak, let Truth and Candor shine … Be silent always when you doubt your Sense; And speak, tho’ sure , with seeming Diffidence …Men must be taught as if you taught them not; And Things unknown propos’d as Things forgot:

( EC , 560–3, 566–7, 574–5)

This ideally-poised man of social grace cannot be universally successful: some poets, as some critics, are incorrigible and it is part of Pope’s education of the poet-critic to leave them well alone. Synthesis, if that is being offered in this final part, does not consist of gathering all writers into one tidy fold but in a careful discrimination of true wit from irredeemable ‘dulness’ (584–630).

Thereafter, Pope has two things to say. One is to set a challenge to contemporary culture by asking ‘where’s the Man’ who can unite all necessary humane and intellectual qualifications for the critic ( EC, 631–42), and be a sort of walking oxymoron, ‘Modestly bold, and humanly severe’ in his judgements. The other is to insinuate an answer. Pope offers deft characterisations of critics from Aristotle to Pope who achieve the necessary independence from extreme positions: Aristotle’s primary treatise is likened to an imaginative voyage into the land of Homer which becomes the source of legislative power; Horace is the poetic model for friendly conversational advice; Quintilian is a useful store of ‘the justest Rules, and clearest Method join’d’; Longinus is inspired by the Muses,who ‘bless their Critick with a Poet’s Fire’ ( EC, 676). These pairs include and encapsulate all the precepts recommended in the body of the poem. But the empire of good sense, Pope reminds us, fell apart after the fall of Rome,leaving nothing but monkish superstition, until the scholar Erasmus,always Pope’s model of an ecumenical humanist, reformed continental scholarship (693-696). Renaissance Italy shows a revival of arts, including criticism; France, ‘a Nation born to serve’ ( EC , 713) fossilised critical and poetic practice into unbending rules; Britain, on the other hand, ‘ Foreign Laws despis’d,/And kept unconquer’d, and unciviliz’d’ ( EC, 715–16) – a deftly ironic modulation of what appears to be a patriotic celebration intosomething more muted. Pope does however cite two earlier verse essays (by John Sheffield, Duke of Buckinghamshire, and Wentworth Dillon, Earl of Roscommon) [13] before paying tribute to his own early critical mentor, William Walsh, who had died in 1708 [9]. Sheffield and Dillon were both poets who wrote criticism in verse, but Walsh was not a poet; in becoming the nearest modern embodiment of the ideal critic, his ‘poetic’ aspect becomes Pope himself, depicted as a mixture of moderated qualities which reminds us of the earlier ‘Where’s the man’ passage: he is quite possibly here,

Careless of Censure , nor too fond of Fame, Still pleas’d to praise, yet not afraid to blame, Averse alike to Flatter , or Offend, Not free from Faults, nor yet too vain to mend.

( EC , 741–44)

It is a kind of leading from the front, or tuition by example, as recommended and practised by the poem. From an apparently secondary,even negative, position (writing on criticism, which the poem sees as secondary to poetry), the poem ends up founding criticism on poetry, and deriving poetry from the (ideal) critic.

Early criticism celebrated the way the poem seemed to master and exemplify its own stated ideals, just as Pope had said of Longinus that he ‘Is himself that great Sublime he draws’ ( EC, 680). It is a poem profuse with images, comparisons and similes. Johnson thought the longest example,that simile comparing student’s progress in learning with a traveller’s journey in Alps was ‘perhaps the best that English poetry can shew’: ‘The simile of the Alps has no useless parts, yet affords a striking picture by itself: it makes the foregoing position better understood, and enables it to take faster hold on the attention; it assists the apprehension, and elevates the fancy’ (Johnson 1905: 229–30). Many of the abstract precepts aremade visible in this way: private judgment is like one’s reliance on one’s(slightly unreliable) watch (9– 10); wit and judgment are like man and wife(82–3); critics are like pharmacists trying to be doctors (108–11). Much ofthe imagery is military or political, indicating something of the social role(as legislator in the universal empire of poetry) the critic is expected toadopt; we are also reminded of the decay of empires, and the potentialdecay of cultures (there is something of The Dunciad in the poem). Muchof it is religious, as with the most famous phrases from the poem (‘For Fools rush in where angels fear to tread’; ‘To err is human, to forgive, divine’), indicating the level of seriousness which Pope accords the matterof poetry. Much of it is sexual: creativity is a kind of manliness, wooing Nature, or the Muse, to ‘generate’ poetic issue, and false criticism, likeobscenity, derives from a kind of inner ‘impotence’. Patterns of suchimagery can be harnessed to ‘organic’ readings of the poem’s wholeness. But part of the life of the poem, underlying its surface statements andmetaphors, is its continual shifts of focus, its reminders of that which liesoutside the tidying power of couplets, its continual reinvention of the ‘you’opposed to the ‘they’ of false criticism, its progressive displacement of theopposition you thought you were looking at with another one whichrequires your attention.

BIBLIOGRAPHY Atkins, G. Douglas (1986): Quests of Difference: Reading Pope’s Poems (Lexing-ton: Kentucky State University Press) Barnard, John, ed. (1973): Pope: The Critical Heritage (London and Boston:Routledge and Kegan Paul) Bateson, F.W. and Joukovsky, N.A., eds, (1971): Alexander Pope: A Critical Anthology (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books) Brower, Reuben (1959): Alexander Pope: The Poetry of Allusion (Oxford: Clarendon Press) Brown, Laura (1985): Alexander Pope (Oxford: Basil Blackwell) Davis, Herbert ed. (1966): Pope: Poetical Works (Oxford: Oxford UniversityPress Dixon, Peter, ed. (1972): Alexander Pope (London: G. Bell and Sons) Empson, William (1950): ‘Wit in the Essay on Criticism ’, Hudson Review, 2: 559–77 Erskine-Hill, Howard and Smith, Anne, eds (1979): The Art of Alexander Pope (London: Vision Press) Erskine-Hill, Howard (1982): ‘Alexander Pope: The Political Poet in his Time’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 15: 123–148 Fairer, David (1984): Pope’s Imagination (Manchester: Manchester University Press) Fairer, David, ed. (1990): Pope: New Contexts (Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf) Morris, David B. (1984): Alexander Pope: The Genius of Sense (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press) Nuttall, A.D. (1984): Pope’s ‘ Essay on Man’ (London: George Allen and Unwin) Rideout, Tania (1992): ‘The Reasoning Eye: Alexander Pope’s Typographic Vi-sion in the Essay on Man’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 55:249–62 Rogers, Pat (1993a): Alexander Pope (Oxford: Oxford University Press) Rogers, Pat (1993b): Essay s on Pope (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) Savage, Roger (1988) ‘Antiquity as Nature: Pope’s Fable of “Young Maro”’, in An Essay on Criticism, in Nicholson (1988), 83–116 Schmitz, R. M. (1962): Pope’s Essay on Criticism 1709: A Study of the BodleianMS Text, with Facsimiles, Transcripts and Variants (St Louis: Washington University Press) Warren, Austin (1929): Alexander Pope as Critic and Humanist (Princeton: PrincetonUniversity Press) Woodman, Thomas (1989): Politeness and Poetry in the Age of Pope (Rutherford,New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press)

Share this:

Categories: Uncategorized

Tags: Alexander Pope , Alexander Pope An Essay on Criticism , Alexander Pope as a Neoclassical Poet , Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , An Essay on Criticism , An Essay on Criticism as a Neoclassical Poem , Analysis of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Analysis of An Essay on Criticism , Bibliography of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Bibliography of An Essay on Criticism , Character Study of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Character Study of An Essay on Criticism , Criticism of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Criticism of An Essay on Criticism , English Literature , Essays of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Essays of An Essay on Criticism , Literary Criticism , Literary Theory , Neoclassical Poetry , Neoclassicism in Poetry , Notes of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Notes of An Essay on Criticism , Plot of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Plot of An Essay on Criticism , Poetry , Simple Analysis of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Simple Analysis of An Essay on Criticism , Study Guides of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Study Guides of An Essay on Criticism , Summary of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Summary of An Essay on Criticism , Synopsis of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Synopsis of An Essay on Criticism , Themes of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Themes of An Essay on Criticism

Related Articles

- Analysis of Alexander Pope's An Essay on Man | Literary Theory and Criticism

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Alexander Pope's "Essay on Criticism": An Introduction

David cody , associate professor of english, hartwick college.

Victorian Web Home —> Some Pre-Victorian Authors —> Neoclassicism —> Alexander Pope ]

Pope's "Essay on Criticism" is a didactic poem in heroic couplets, begun, perhaps, as early as 1705, and published, anonymously, in 1711. The poetic essay was a relatively new genre, and the "Essay" itself was Pope's most ambitious work to that time. It was in part an attempt on Pope's part to identify and refine his own positions as poet and critic, and his response to an ongoing critical debate which centered on the question of whether poetry should be "natural" or written according to predetermined "artificial" rules inherited from the classical past.

The poem commences with a discussion of the rules of taste which ought to govern poetry, and which enable a critic to make sound critical judgements. In it Pope comments, too, upon the authority which ought properly to be accorded to the classical authors who dealt with the subject; and concludes (in an apparent attempt to reconcile the opinions of the advocates and opponents of rules) that the rules of the ancients are in fact identical with the rules of Nature: poetry and painting, that is, like religion and morality, actually reflect natural law. The "Essay on Criticism," then, is deliberately ambiguous: Pope seems, on the one hand, to admit that rules are necessary for the production of and criticism of poetry, but he also notes the existence of mysterious, apparently irrational qualities — "Nameless Graces," identified by terms such as "Happiness" and "Lucky Licence" — with which Nature is endowed, and which permit the true poetic genius, possessed of adequate "taste," to appear to transcend those same rules. The critic, of course, if he is to appreciate that genius, must possess similar gifts. True Art, in other words, imitates Nature, and Nature tolerates and indeed encourages felicitous irregularities which are in reality (because Nature and the physical universe are creations of God) aspects of the divine order of things which is eternally beyond human comprehension. Only God, the infinite intellect, the purely rational being, can appreciate the harmony of the universe, but the intelligent and educated critic can appreciate poetic harmonies which echo those in nature. Because his intellect and his reason are limited, however, and because his opinions are inevitably subjective, he finds it helpful or necessary to employ rules which are interpretations of the ancient principles of nature to guide him — though he should never be totally dependent upon them. We should note, in passing, that in "The Essay on Criticism" Pope is frequently concerned with "wit" — the word occurs once, on average, in every sixteen lines of the poem. What does he mean by it?

Pope then proceeds to discuss the laws by which a critic should be guided — insisting, as any good poet would, that critics exist to serve poets, not to attack them. He then provides, by way of example, instances of critics who had erred in one fashion or another. What, in Pope's opinion (here as elsewhere in his work) is the deadliest critical sin — a sin which is itself a reflection of a greater sin? All of his erring critics, each in their own way, betray the same fatal flaw.

The final section of the poem discusses the moral qualities and virtues inherent in the ideal critic, who is also the ideal man — and who, Pope laments, no longer exists in the degenerate world of the early eighteenth century.

Incorporated in the Victorian Web July 2000

- Project Gutenberg

- 73,217 free eBooks

- 15 by Alexander Pope

An Essay on Criticism by Alexander Pope

Read now or download (free!)

Similar books, about this ebook.

- Privacy policy

- About Project Gutenberg

- Terms of Use

- Contact Information

British Literature Wiki

An Essay on Criticism

Alexander Pope wrote An Essay on Criticism shortly after turning 21 years old in 1711. While remaining the speaker within his own poem Pope is able to present his true viewpoints on writing styles both as they are and how he feels they should be. While his poetic essay, written in heroic couplets, may not have obtained the same status as others of his time, it was certainly not because his writing was inferior (Bate). In fact, the broad background and comprehensive coverage within Pope’s work made it it one of the most influential critical essays yet to be written (Bate). It appears that through his writing Pope was reaching out not to the average reader, but instead to those who intend to be writers themselves as he represents himself as a critical perfectionist insisting on particular styles. Overall, his essay appears to best be understood by breaking it into three parts.

The scholar Walter Jackson Bate has explained the structure of the essay in the following way:

I. General qualities needed by the critic (1-200):

1. Awareness of his own limitations (46-67). 2. Knowledge of Nature in its general forms (68-87).

- Nature defined (70-79).

- Need of both wit and judgment to conceive it (80-87).

3. Imitation of the Ancients, and the use of rules (88-200).

- Value of ancient poetry and criticism as models (88-103).

- Censure of slavish imitation and codified rules (104-117).

- Need to study the general aims and qualities of the Ancients (118-140).

- Exceptions to the rules (141-168).

II. Particular laws for the critic (201-559): Digression on the need for humility (201-232):

1. Consider the work as a total unit (233-252). 2. Seek the author’s aim (253-266). 3. Examples of false critics who mistake the part for the whole (267-383).

- The pedant who forgets the end and judges by rules (267-288).

- The critic who judges by imagery and metaphor alone (289-304).

- The rhetorician who judges by the pomp and colour of the diction (305-336).

- Critics who judge by versification only (337-343).

Pope’s digression to exemplify “representative meter” (344-383). 4. Need for tolerance and for aloofness from extremes of fashion and personal mood (384-559).The fashionable critic: the cults, as ends in themselves, of the foreign (398-405), the new (406-423), and the esoteric (424-451).

- Personal subjectivity and its pitfalls (452-559).

III. The ideal character of the critic (560-744):

1. Qualities needed: integrity (562-565), modesty (566-571), tact (572-577), courage (578-583). 2. Their opposites (584-630). 3. Concluding eulogy of ancient critics as models (643-744).

To uncover the deeper meaning of An Essay on Criticism click here

Back to Alexander Pope

- Novel & Dramas

- Non-Fiction Prose

An Overview of An Essay on Criticism

This post provides an overview of An Essay on Criticism by Alexander Pope.

AN OVERVIEW OF AN ESSAY ON CRITICISM

~BY ALEXANDER POPE

Alexander Pope was born in the year 1688, during the year of revolution in London. He in many respects was a unique figure of the English literary history. Firstly, because he was considered to be “the poet” of a great nation. He was an undisputed master in the narrow field of satiric and didactic verse during the early 18 th century. Pope’s influence completely dominated the poetry of his age. Many foreign writers looked to him and many English poets looked to him as their inspiration. Secondly, he was one of the writers who was a remarkable reflection of the spirit of the age he lived in. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Thirdly, he was the one and only important writer of the age who gave his whole life to letters. Unlike Swift, Addison and other writers of his age, Pope was someone who chose only literature as his profession. And fourthly, by the sheer force of his ambition he won his place, and held it, in spite of religious prejudice, and in the phase of physical and temperamental obstacles that would have discouraged a stronger man. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Alexander Pope’s “An Essay on Criticism” is perhaps the clearest statement of neoclassical principles in any language. Pope in this essay, not only gives the scope of good literary criticism, but he also redefines classical virtues in terms of ‘nature’ and ‘wit’ as necessary to both poetry and criticism. “An Essay on Criticism” was first published anonymously through an obscure book seller. Now, coming to Neoclassicism, it is basically a political and philosophical movement that developed during the age of enlightenment. One of the main characteristics of neoclassicism was decorum. But, the central tenant was the imitation of nature. This was to be achieved by artist modelling their work on the ancients.

Thus, the poets and dramatist were less interested in new forms than in inventing the new forms and were more into imitating the old ones of epic, eclogue, epigram, elegy, ode, satire, comedy, tragedy and so on. Indeed an awareness of the characteristics of each genre, and their relation to one another, was an integral feature of the neoclassicism. The neo-classicists were often termed as traditionalists, and they believed that literature was an art to be perfected by discipline, vigorous study and continuous practice. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

“An Essay on Criticism” is written in verse, in the form of Horace’s Ars Poetica. It sums up the art of poetry as first taught by Horace and then Boileau and the 18 th century classicists. Though written in Heroic couplets, we hardly consider this is a poem but rather a storehouse of critical maxims.

Alexander Pope in his “An Essay on Criticism” calls for a “return to nature” is complex. On the cosmic level Nature signifies the convenient order of the world and the universe, a hierarchy in which each entity has a proper assigned place of its own. Nature can refer to what is central, common and universal to all human experience, encompassing the spheres of morality and knowledge. It also signifies the rules of proper moral conduct as well as archetypal or representative patterns of human reason. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

It means having qualities that makes someone one of a kind. Nature for him is thus, is a universal and general regulation that beyond human beings control or grasp but is indispensable in influencing their literary creation. It seems more of a divine source of inspiration or a sort of sacred rules than personal skills or individual talent. Pope says that Nature has the capability to render “life, force and beauty” to an art. Literary creation and appreciation is redefined and regulated by Nature. Nature constitutes and functions as “the Source, and End, and Text of art”. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

To acquire a better judgement and redefined taste of Literature depends on Nature, which is “just”, “unerring”, “divinely bright”, “clear” and “universal”. Any art that fails to reflect nature is not worth to be called an art at all. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

In the essay “An Essay on Criticism”, Pope puts a great emphasis on the word “Wit”. The word wit in Pope’s time could refer in general to intelligence, it also meant in the modern sense of cleverness, as expressed in figures of speech and especially discerning unanticipated similarities between different entities. Wit according to Pope is the general ability of a writer to express the truth and morality. According to Pope, wit is the reflection of imitation. True wit, exists in the relationship among ideal image and expression. Wit is like an everlasting sea. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Pope’s exploration of wit lines up with the central classical virtues, which are themselves equated with Nature: “True Wit is Nature to Advantage drest,/ What oft was Thought, but ne’er so well Exprest” (297-298). (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Pope subsequently says that expression is the “Dress of Thought” and that “true expression” throws light on objects without altering them. The lines above are concentrated expressions of Pope’s classicism. If wit is the “dress” of nature, it will express nature without altering it. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

While Pope says that the good poets makes the best critics, and while he notice that some critics are failed poets, he points out that both the best poetry or the best criticism are divinely inspired: “Both must alike from Heav’n derive their Light” (13-14). Pope sees the endeavour of criticism as a noble one, provided it abides by Horace’s advice for the poet:

"But you who seek to give and merit Fame,

And just bare a Critick’s noble Name,

Be sure your self and your own Reach to know,

How far your Genius, Taste , and Learning go

Launch not beyond your Depth... (46-56)"

Apart from knowing his own capacities, the critic must also be fully familiar with every aspect of the author whom he/she is examining. Pope suggests the critic that he base his interpretation on the author’s intention: “In ev’ry Work regard the Writer’s End, / Since none can compass more than they Intend”. (233-234, 255-256). (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Pope notes down two other guidelines to be followed by the writers and the critics. The first is to recognize the overall unity of a work and thereby to avoid falling into partial assessments based on the writer’s use of poetic, conceits, ornamented language, meters as well as judgements which are biased towards either archaic or modern styles or based on the reputations of given writers. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Pope, finally advices that a critic needs to possess a moral sensibility, as well as a sense of balance and proportion, this he indicates in the lines: “Nor in the Critick let the Man be lost! / Good-Nature and Good-Sense must ever join” (523-525). (An Overview of An Essay of Criticism)

Pope then, ends his advice with a summary of an ideal critic:

"But where’s the Man, who counsel can bestow,...

And Love to Praise, with Reason on his Side? (631-642)"

The qualities of a good critic are primarily attributes of humanity or moral sensibility rather than aesthetic qualities. Indeed, the only specifically aesthetic quality mentioned here is “taste”. The remaining virtues might be said to have theological ground, resting on the ability to overcome pride. Pope effectively transposes the language of theology (“soul” and “pride”). The reason to which Pope appeals is (as in Aquinas and many medieval thinkers) a universal representation in human nature, and is a result of humility. It is thus, a disposition of humility – an aesthetic humility, if you will – which enables the critic to avoid the foregoing faults. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Now, Pope goes on to provide advice to both poet and critic. The utmost important advice here is to “follow Nature,” whose restraining function he explains:

"Nature is all fix’d the Limits fit,

And wisely curb’d proud Man’s pretending Wit;

... One Science only will one Genius fit;

So vast is Art, so Narrow Human Wit ... (52 – 53)"

Pope, designates human wit generally as an instrument of Pride. He, however, clarifies that in the scheme of nature, man’s wit finds an appropriate place. It is in this context Pope says that:

"First follow NATURE, and your Judgement frame

By her just Standard, which is still the same;

Unerring Nature, which is still divinely bright,

Once clear, unchang’d and Universal Light,

Life, Force, and Beauty, must to all impart,

At once the Source, and End, and Test of Art." (68 – 73) (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Pope unlike other medieval rhetoricians, does not entirely believes that poetry is a rational process. He seems to assert the primacy of wit over judgement, of art over criticism, viewing art as inspired and as transcending the norms of conventional thinking in its direct appeal to the heart. The critic’s task here as Pope suggests, is to recognize the superiority of great wit. While these emphasis strides beyond many medieval and Renaissance aesthetics, it must of course be read in its own poetic context. He warns the writers and authors that should not just rely on their own insights but draw on the common store of poetic wisdom, established by the ancients. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Pope’s exploration of wit lines up with the central classical virtues, which are themselves equated with Nature: “True Wit is Nature to Advantage drest,/ What oft was Thought, but ne’er so well Exprest” (297-298). Pope subsequently says that expression is the “Dress of Thought” and that “true expression” throws light on objects without altering them. The lines above are concentrated expressions of Pope’s classicism. If wit is the “dress” of nature, it will express nature without altering it. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

The poet’s task here is twofold: not only to find the expression that will most truly convey nature, but to ensure that the substance he is expressing is indeed a natural insight or thought.

Another classical ideal urged by Pope is that of organic unity and wholeness. The expression or style must be suited to the subject matter and meaning: “The Sound must seem an Echo to the Sense ” (365)

Pope advices both Poet and critic to follow the Aristotelian ethical maxim: “Avoid Extremes”. For those who excess in any direction display “Great Pride, or Little Sense” (384 – 387). (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Indeed the central passage in “An Essay on Criticism”, as in the later “Essay on Man”, Pope views all the major faults as stemming from pride. It is pride which leads critics and poets to overlook universal truths in favour of subjective whims: pride which cause them to value only certain parts but not the whole, which disables them to attain a harmony between wit and judgement, and pride which underlies their excesses and biases. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Pope’s final strategy in “An Essay on Criticism” is to equate the classical literary and critical traditions with nature, and to sketch a redefined outline of literary history from classical times to his own era. Pope insists that the rules of nature were merely discovered, not invented, by the ancients: “Those Rules of old discover’d, not devis’d, / Are Nature still, but Nature Methodiz’d” (88-89). (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Pope’s advice for both critic and poet is clear: “Learn hence for Ancient Rules a just Esteem; / To copy Nature is to copy Them” (139 – 140). Pope traces the genealogy of “nature”, as embodied in classical authors.

When was An Essay on Criticism published?

What does pope say about nature, what did alexander pope say about "wit", what advice did pope give to critics and poets in his essay "an essay on criticism".

https://literarysphere.com/summary-of-upon-westminster-bridge-poem/(opens in a new tab)

You may like these posts

Post a comment, social plugin, search this blog, popular posts.

- June 2022 1

- August 2022 6

- November 2022 1

- April 2023 3

- June 2023 4

- July 2023 1

- November 2023 1

- January 2024 34

- February 2024 30

- March 2024 13

Hello, I am Parishmita Roy

Default Variables

Poetry Prof

Read, Teach, Study Poetry

from An Essay on Criticism

Join Alexander Pope on a metaphysical journey of discovery… that will last a lifetime.

“[It is] difficult to know which part to prefer, when all is equally beautiful and noble.” Weekly Miscellany comments on the poetry of Alexander Pope

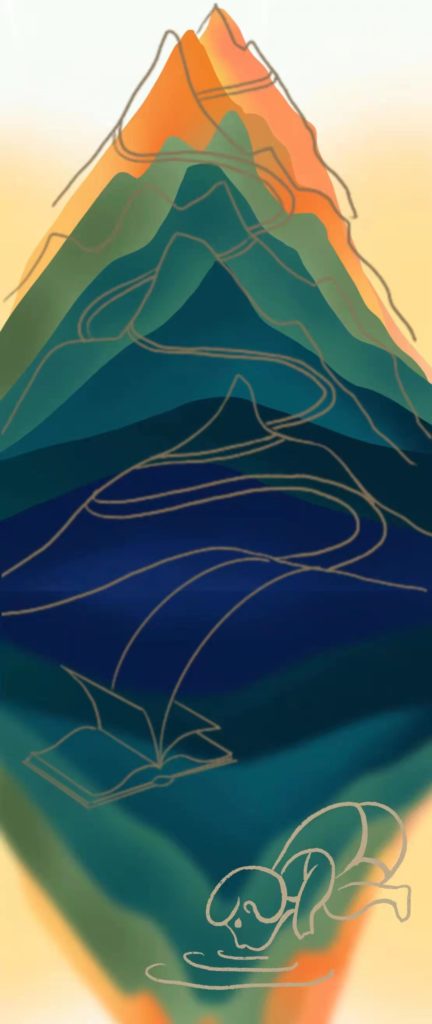

Alexander Pope spent his childhood in Windsor forest and, from an early age, gained a keen appreciation for nature. Later in his life he lived in a property by the River Thames in London where he cultivated his own garden that he opened for visitors. In today’s poem, written in 1709, we can see this love of the natural world through his shaping of elements of the landscape into an extended metaphor for knowledge. This landscape is vast and mountainous: the Alps , Europe’s largest mountain range are a prominent feature, as are hills, vales , an endless sky and eternal snows . Compared to this vast landscape, people are almost insignificant. Their role in the poem is to act as explorers who set off on a journey of discovery, trying to conquer the highest mountains by ascending to the summit; we tempt the heights of Arts… the towering Alps we try… Finally, despite being almost exhausted by his efforts, the explorer realises that his journey has barely begun; the mountain vista stretches ahead, unbroken, into the distance:

A poem’s central idea, often developed into an extended metaphor, is known as a conceit . Unlocking the first couplet should provide you the key to Pope’s conceit in An Essay on Criticism . Pope begins with a warning that:

The Pierian Spring is an important place in Greek Mythology , the source of a river of knowledge that was associated with the nine ancient Muses, themselves a metaphor for artistic inspiration. In this poem, it’s part of the landscape that functions as an extended metaphor for learning. It might seem strange that Pope begins by giving his readers a warning to taste not the waters of this river. However, it’s important to realise that Pope isn’t saying not to drink from the well of knowledge at all. He tells us to drink deep , emphasising his instruction with both alliterative D and using the imperative tense (where the verb is placed at the beginning of the line or phrase). To Pope’s mind, learning is seductive and intoxicating . Once you set out on the journey of learning, or take even a tiny sip from the wellspring of knowledge, you won’t be able to resist the temptation to learn more. Therefore, he suggests that you either prepare to immerse yourself completely in the Pierian Spring , or don’t drink at all.

Once you’ve discovered the connotations of Pierian Spring , the rest of the poem can be read as a warning (or criticism ) of anyone who is rash enough not to follow Pope’s instruction. Should you venture unprepared into the unknown, you must be clear about your limitations. As a spring is the starting point of a river, so too is it the starting point of Pope’s extended metaphor . From here, the reader sets out on a journey into an imposing mountainous landscape that, while initially appearing it can be ‘climbed’ or conquered, actually keeps expanding into an endless vista. No matter how far the explorer climbs, the top of the mountain never gets any nearer. Heights, lengthening way, increasing prospect and, most telling of all, eternal snows conjure the visual image of the landscape metaphysically stretching out in front of our weary eyes. Individual people are tiny and easily lost in this ever-shifting world. Pope creates a contrast between the boundless landscape and the bounded limits of human perception. At the last, the human explorer is tired by his efforts to conquer these mountains of knowledge – but the poem ends by revealing that he’d barely even gotten started on his journey: Hills peep o’er hills; Alps upon Alps arise .

Before we get too much further into the discussion of Pope’s ‘essay’, it might be helpful to place these lines in context. Despite the way they seem to be a complete poem in themselves, they are actually part of a much longer poem which stretches to three parts and a total of 744 lines! The eighteen-line extract you’ve read constitutes the second verse of Part 2 and it may help you to know that, in the first verse, Pope singled out pride as the characteristic that would eventually lead to the downfall of his explorer. Here are four lines from earlier in the Essay:

In this short sample, you can see the names Pope calls people who rush off on foolhardy adventures without taking the time to properly prepare: blind man , weak head and fools ! Younger readers might not enjoy this interpretation, but Pope finds the overconfidence of young people most problematic, associating youth with a kind of recklessness that, in hindsight, is misplaced.

You may argue that qualities such as fearless and passionate (fired) seem like compliments; but I detect a note of criticism in Pope’s words; he suggests that young people confuse emotion with clear thinking and they are too eager to plunge into the unknown. There’s an emphasis on speed and rashness ( pleased at first; at first sight ) that cannot last, like a novice marathon runner who goes sprinting out of the blocks while older, more wily competitors know to save themselves for the challenges ahead. While the young explorer does encounter some early success (implied by words like mount , more advanced , attained and, more significantly by an image : tread the sky ), the race is longer than the runner thought and inevitably the pace must sag. Later in the poem, positive diction disappears and words like trembling , growing labours , and tired take over as the true scale of the challenge becomes apparent. Sharp-eyed readers will already have noticed that the image of ‘treading the sky’ was in fact a simile : seem to tread the sky. Subtly, Pope’s use of a simile implies that any success the explorer thought he’d achieved wasn’t actually real.

The implication that over-enthusiasm can cloud good judgment can be traced through diction to do with looking and seeing: a t first sight, short views, see, behold, appear, survey, eyes and peep pepper the poem and convey the poet’s belief that, to our detriment, we can be short-sighted and tunnel-visioned. The eighth line of the poem is entirely concerned with this idea: short views we take, nor see the lengths behind paints a picture of a young explorer who only looks in one direction – eyes fixed straight ahead – and so misses the bigger picture.

While the poem is certainly didactic (it’s trying to impart a lesson), Pope’s tone of voice is not too condescending or stand-offish because he includes himself in his criticism as well. Throughout the poem the words us, we and our soften his accusations so there’s never a ‘them-and-us’ divide between young and old. In fact, Pope was only 21 years old when he finished his Essay on Criticism , so use your mind’s ear to imagine him speaking ruefully from experience, rather than as a nagging or pestering adult complaining about ‘young people today.’ The line Fired at first sight by what the Muse imparts is revealing in this regard. Alluding to the nine Muses of Greek mythology , this line personifies poetic inspiration, so in one sense the extended metaphor of trying to conquer an unknowable landscape represents his own experiences of writing poetry. ‘Meta-poems’ (poems about the writing of poems) actually have a name: ars poetica . Pope implies that rushing off on a path of artistic endeavour without realising the true extent of the commitment that entails is a mistake that he himself has made in his own attempts at writing.

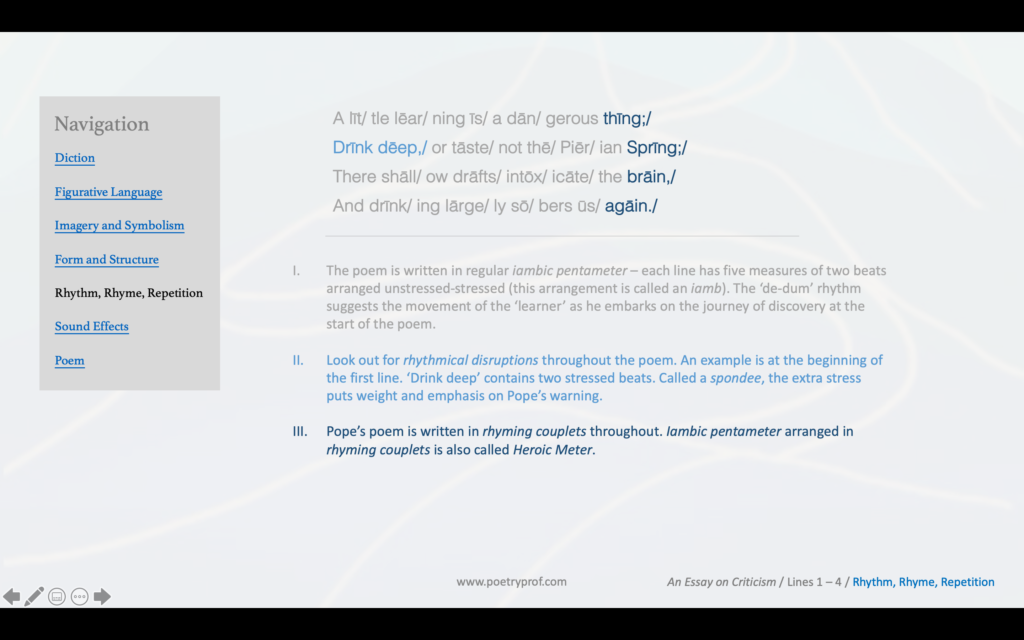

If you’re a student reading this who thinks you might be able to use Pope’s poem as an excuse not to do your homework or give up on your own writing: you shouldn’t be too rash. Pope’s not suggesting we should quit. Instead, he’s warning us that what might seem like a shallow pool is in fact a deep river of knowledge. Once you jump in, the current will sweep you away and there’s no going back. The poem is a criticism of unpreparedness and arrogance rather than an acknowledgement of futility. In fact, an element of form suggests that, for all the faults Pope has pointed out in young people who are too confident in their limited abilities, it is much more praiseworthy to try and fail to conquer the heights than never to try at all. The poem is written in iambic pentameter that is constant and regular as if, no matter how tough the going gets, the young explorer doesn’t give up. Compare these two lines, with iambic accents marked, from the beginning and end of the poem to see how the rhythm is unfailing:

More, the poem is arranged in rhyming couplets (the rhyme scheme is AA, BB, CC and so on). Rhyming couplets written in iambic pentameter are traditionally known by a more dramatic name: heroic couplets . Pope was widely considered to be the master of writing poetry in heroic couplets ; using them here implies that Pope ultimately believes any young person who’s brave – or foolhardy – enough to embark upon the lifelong journey of learning is worthy of praise.

The structure of Pope’s poetical essay matches the message he’s trying to convey – that, once you start learning, you won’t be able to stop. Look carefully at the punctuation marks, in particular his use of full stops . You’ll find the first one at the end of the fourth line, the second after the tenth and the third at the end of the poem (after eighteen lines). In other words, if the poem was arranged in verses, the first verse would be nice and short at only four lines, the second would stretch to six, but the final verse would have doubled in length to eight lines. Expanding sentences represent the conceit – a little learning is a dangerous thing – and match the images of the landscape expanding ( eternal snows , increasing prospect, lengthening way ) as you read further down the poem.

The end of the poem brings Pope’s criticism to its conclusion. We see the young explorer break through the eternal snows , climb above the clouds, and stand triumphantly on the mountain top, proudly surveying his achievements. Only now does he take a moment to look more deliberately at the mountains he’s trying to conquer:

Be alert to two words that might seem insignificant: appear and seem , words that signal the mistake the explorer made; he thought that he had already past the bulk of his journey. Read carefully to punctuation as well, and you’ll see the colon – a longer pause, which creates a caseura – representing the traveler pausing at the moment of his triumph… and it’s here that realisation finally dawns. Despite the difficulty of his climb thus far, the landscape ( increasing prospect ) stretches out endlessly in front of him: Hills peep o’er hills, and Alps on Alps arise . Here, repetition mixes with all that increasing and lengthening diction to create a surreal image of an ever-expanding landscape stretching out ahead. You might also notice P sounds peppering the last two lines of the poem in the words p ee p , Al p s, Al p s, and p ros p ect . Coming from a category of alliteration called plosive , this sound is excellent at conveying a release of negative emotion, as it is formed by pushing air through closed lips. The sound helps us perceive the taste of victory turning to defeat as the weary traveler’s shoulders slump at the prospect of the endless climb still to come.

What does Pope offer as a solution? He already warned us at the start of the poem: drinking largely sobers us again . Suddenly, the importance of the word sober becomes clear. While the idea of heading off on this journey of discovery was intoxicating , firing up those with passion to learn, discover and explore – the reality is very different. That young, over-confident learner/explorer is gone, replaced by a wiser, but more world-weary traveler who can finally see the true scale of the task ahead. By now it’s too late, he’s stuck on the mountain top and there’s only one thing he can do – go onwards!

So drink deep and be prepared to encounter much more than you expected when you set out on your journey.

Suggested poems for comparison:

- from Essay on Man by Alexander Pope

An Essay on Criticism was not the only poetical essay written by Pope. French writer Voltaire so admired Pope’s Essay on Man that he arranged for its translation into French and from there it spread around Europe.

- Marrysong by Dennis Scott

As in Pope’s poem, Scott creates a metaphor of the landscape to represent his marriage. He is an explorer in a strange land – each time the explorer glances up from his map, the landscape has changed and he’s lost again.

- Through the Dark Sod – As Education by Emily Dickinson

Victorians brought many different associations to all kinds of plants and flowers. In this Emily Dickinson poem, the lily represents beauty, purity and rebirth. This link will also take you to a fantastic blog which aims to read and provide comment on all of Emily Dickinson’s poems. So that’s 1 down, and nearly 2000 more to go…

- In the Mountains by Wang Wei

Often spoken of with the same reverence as Li Bai and Du Fu, Wang Wei is a famous imagist poet in China. In these exquisite portrait poems, Wang Wei paints pictures of the impressive landscapes of his mountain home.

Additional Resources

If you are teaching or studying An Essay on Criticism at school or college, or if you simply enjoyed this analysis of the poem and would like to discover more, you might like to purchase our bespoke study bundle for this poem. It costs only £2 and includes:

- Study Questions with guidance on how to answer in full paragraphs;

- A sample analytical paragraph for essay writing;

- An interactive and editable powerpoint, giving line-by-line analysis of all the poetic and technical features of the poem;

- An in-depth worksheet with a focus on analysing diction and explaining lexical fields ;

- A fun crossword quiz, perfect for a starter activity, revision or a recap;

- A four-page activity booklet that can be printed and folded into a handout – ideal for self study or revision;

- 4 practice Essay Questions – and one complete model Essay Plan.

And… discuss!

Did you enjoy this analysis of Alexander Pope’s Essay on Criticism ? Do you agree that the poem somewhat singles out young people? Can you relate to Pope’s messages about the temptations of learning? Why not share your ideas, ask a question, or leave a comment for others to read below. For nuggets of analysis and all-new illustrations, find and follow Poetry Prof on Instagram.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Ballad Criticism, Genre Theory, and the Dismantling of Rhetoric

- First Online: 02 January 2022

Cite this chapter

- Ralph Cohen 5 &

- John L. Rowlett 6

Part of the book series: Palgrave Studies in the Enlightenment, Romanticism and Cultures of Print ((PERCP))

112 Accesses

Cohen indicates the historical transformations that take place when the discipline of rhetoric is dispersed and its explanatory power displaced by other procedures, by the kind of explanations that rhetoric could not make. In a brilliant analysis, he takes “a problem that involves persuasion and examine[s] how persuasion is accomplished. The problem is the elevation of one kind of writing to a kind respected by the learned—popular ballads to a recognized literary genre. The dismantling of rhetoric as a discipline and the elevation of the ballad to literary status can be seen as complementary phenomena: the decline of a discipline which systematized oral communication and the rise of an oral poetic form that became divorced from orality, became a written rather than oral genre.”

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Addison, Joseph, and Richard Steele, The Spectator , ed. Donald F. Bond, 5 vols., 1: No. 85. My citations are by number.

The Poems of Alexander Pope , ed. John Butt (New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press, 1963), 148.

William Wagstaffe, A Comment upon the History of Tom Thumb, in Miscellaneous Works of Dr. William Wagstaffe , 2nd ed. (London: Printed for Jonah Bowyer, 1726), 4.

Thomas Percy, Reliques of Ancient English Poetry , 4th ed., 3 vols. (London: John Nichols, 1794), 1:xvii.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of English, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA

Ralph Cohen

Independent Scholar, Charlottesville, VA, USA

John L. Rowlett

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cohen, R., Rowlett, J.L. (2021). Ballad Criticism, Genre Theory, and the Dismantling of Rhetoric. In: Rowlett, J.L. (eds) Transformations of a Genre. Palgrave Studies in the Enlightenment, Romanticism and Cultures of Print. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-89668-3_12

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-89668-3_12

Published : 02 January 2022

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-89667-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-89668-3

eBook Packages : Literature, Cultural and Media Studies Literature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Genre Criticism

In the latter half of the 20th Century, Rhetorical Studies underwent something of a democratization. The term democratization typically conjures images of a collapsing political regime moving toward democratic ideals and practices, thereby making the system more open and accessible. In much the same way, Rhetorical Studies in this period began to question the dominant practices that dogged the discipline for, quite literally, several millennia – and slowly redefined not only what “rhetoric” meant, but also what it meant to study the art. No longer were scholars confined to the traditions of the past – instead, this democratization urged new ways of thinking.

Of course, this is not to suggest that Rhetorical Studies once operated in the same fashion as an authoritarian regime – just simply that for the better part of its history, to engage rhetoric meant to only engage with Aristotle, with secondary and tertiary focus on other Ancient Greek and Roman figures. Although the other forms of rhetorical criticism that are discussed in our article on Rhetorical Studies certainly came into being as a result of this democratization, Genre Criticism is a manifestation that, by and large, was born early in the process.

In this article, we further explore genre and Genre Criticism, briefly articulate the history of Genre Criticism in Rhetorical Studies, and then feature some scholars whose work employs this method of rhetorical criticism. Afterwards, we consider Genre Criticism’s place in Rhetorical Studies today and look ahead to its future.

Further Exploring Genre

As we mentioned in our article on Rhetorical Studies , genre is a “constellation of recognizable forms bound together by an internal dynamic” (Campbell & Jamieson, 1978). These “constellations” can take shape in communicative forms throughout culture. Indeed, while popular connotations of genre include styles of music and film, genre is perhaps best known in its literary and artistic forms – and we typically draw from terminology in literary studies when discussing genre in most instances. Comedies and tragedies, for example, are prevalent in literature as well as film.

In preparing to conduct some form of Genre Criticism, students ought to begin with something they consider familiar – like a genre of music or film. What about your favorite genre of music, for example, moves you the most? Be as specific as possible – is it the subject or tone of the lyrics, the instruments used, the beat, the vocalics of the various vocalists? Then, consider what is common across the genre. What stays consistent? What changes? What does this do or not do for audiences?

Beginning with something familiar can help students attempting to perform a Genre Criticism at the graduate level get in the right state of mind in recognizing the internal dynamics that comprise rhetorical genres. While theorizing a new genre of discourse is certainly exciting and remarkable – consider what has not been said about an existing genre of discourse. What does this gap mean for the genre – or what does this gap say about the study of rhetoric? Without question, exploring genre further can be challenging – but also rewarding.

Featured Scholars Researching Genre in Rhetorical Studies

Although mostly retired, Dr. Miller’s work in both teaching and researching genre continues to be thoroughly influential. In addition to being the founding director of NC State’s Ph.D. program in Communication, Rhetoric, and Digital Media, Dr. Miller penned or edited several essays and books that further advance our understanding of genre in rhetoric. Most recently, Dr. Miller co-edited two books on Genre Criticism – Landmark Essays on Rhetorical Genre Studies (2018) and Emerging Genres in New Media Environments (2017).

With research interests housed at the intersection of health and medical rhetoric, discourses on illness, and gender and technology, Dr. Arduser utilizes Genre Criticism often. Her approach to genre is thoroughly interdisciplinary – she has a background in English Literature, Anthropology, and Technical Communication – and is currently an Associate Professor in the Department of English at the University of Cincinnati. Dr. Arduser’s chapter in the aforementioned book Emerging Genres in New Media Environments (2017) is entitled “Remediating Diagnosis: A Familiar Narrative Form or Emerging Digital Genre?”

The co-editor of Emerging Genres in New Media Environments (2017) with Dr. Miller, Dr. Mehlenbacher is a scholar specializing in science communication and its manifestations in various networked publics. Dr. Mehlenbacher is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department of English Language and Literature at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, Canada. Like Dr. Arduser, Dr. Mehlenbacher employs Genre Criticism often in her work, also bringing an interdisciplinary background to the method and methodology.

Admittedly, most of Dr. Gunn’s research cannot be labeled singularly under “Genre Criticism.” However, his 2012 essay “Maranatha” in the Quarterly Journal of Speech demonstrated both the versatility of Genre Criticism in its traditional application, and its malleable nature in more modern and non-discursive contexts. In this essay, Dr. Gunn analyzed Mel Gibson’s viscerally violent depiction of Jesus’ final hours in The Passion of the Christ and extended genre criticism to what he (and others) call “bodily affect.”

Dr. Devitt studies “everyday genres,” or the genres that people encounter on a regular basis (“Amy J. Devitt,” 2012). In addition to co-editing Landmark Essays on Rhetorical Genre Studies with Dr. Miller, Dr. Devitt has written more than a dozen peer-reviewed essays and books on genre, including Writing Genres (2004) and “Genre: Performance and Change” (with Dr. Miller, 2018). As a Professor in the Department of English at the University of Kansas, Dr. Devitt blends her research with her teaching – and also writes a blog about genre, helping to bridge the divide between the fabled “Ivory Tower” of academia and the general public.

Currently a Professor of Education at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Dr. Bazerman’s research centers on genre and scientific writing as it developed throughout history. Throughout his career, Dr. Bazerman has penned more than a dozen books and has edited over twenty collections on genre and writing. Perhaps most notably, Dr. Bazerman proposed that genre, as we commonly understand it, constitute meaning in the context of other genres. In other words, the lines of demarcation from one genre help set the parameters of another.

The History of Genre Criticism in Rhetorical Studies

While genre was studied in other humanistic academic traditions – namely English and Literature – for some time, it wasn’t until the late 1960’s and early 1970’s that studying genre gained traction in Speech Communication departments across the United States. Many scholars point to Ware and Linkugel’s (1973) essay in the Quarterly Journal of Speech , “They Spoke in Defense of Themselves: On the Generic Criticism of Apologia,” as the inception of Genre Criticism in Speech and Communication Studies.

Indeed, most graduate seminars in Rhetorical Studies will introduce Genre Criticism to students through Ware and Linkugel’s (1973) now foundational essay. In this essay, the authors claimed that instances of apologia, or, apologetic discourse in which speakers defend themselves from charges against their character or actions, to be a universally prevalent form of public address across human history, with particular emphasis on its import in modernity.

Borrowing from Abelson’s (1959) four modes of resolution, Ware and Linkugel (1973) argued that apologetic discourse is a distinct genre of rhetoric in that speakers, when accused of something, will employ one of, or a series of, the four modes in defending themselves. The four modes of resolution are: denial, bolstering, differentiation, and transcendence. With this terminology, Ware & Linkugel (1973) analyzed several speeches, like then-Senator Ted Kennedy’s “Chappaquiddick” Speech and Eugene V. Debs’ remarks at his trial for supposed violations to the Espionage Act, revealing the nuanced ways the speakers orally defended their character and actions.

After graduate students are introduced to Genre Criticism through apologia, most courses will then feature work from Karlyn Kohrs Campbell and Kathleen Hall Jamieson. While Campbell and Jamieson are featured in our article on Presidential Communication Research , their work in Genre Criticism is similarly foundational to Communication Studies. Indeed, Campbell and Jamieson’s (1978) book – and their introductory essay to the book – “Form and Genre: Shaping Rhetorical Action” further delineated genre and rhetoric.

Combining both genre and Presidential Communication research, Campbell and Jamieson (updated in 2008) compiled yet another landmark set of research in their book Presidents Creating the Presidency: Deeds Done in Words . From Inaugural Addresses to war rhetoric, Campbell and Jamieson (2008) set the parameters of the use of genre in Presidential Communication, and thoroughly articulated its uses throughout American history.

Genre Criticism Today

In any Communication Studies graduate seminar, the question a student will inevitably be asked when crafting an essay will be “so what?” Put differently, why does what is being studied matter and what is this scholarship revealing? Indeed, these are questions that every academic must keep in mind when researching and writing.

Perhaps more so than other forms of rhetorical criticism, a common challenge in examining genre in rhetoric typically assumes the form of the aforementioned questions – with the added caveat: what happens when all the genres of discourse are accounted for? In other words – what is the point of Genre Criticism, or what can Genre Criticism reveal that is new, interesting, or unique? When made in good faith, this challenge is certainly warranted. However, bad faith critiques largely ignore the possibility of new modes of discourse or instances when rhetors subvert existing genres.

For example, while Presidential War Rhetoric is a thoroughly researched and well-documented genre – does President Trump’s use of twitter in notifying the public of his decision to conduct airstrikes in Syria after President Bashar al-Assad employed chemical weapons against his own people constitute as a unique subversion to the genre worthy of further examination? Or, what are the rhetorical implications of President Trump – or even future presidents – tweeting their intent to ask Congress to declare war well before formally sending the request to the constitutionally constructed co-equal branch in American government?

A student examining President Trump’s addition – or his challenge – to the genre of Presidential War Rhetoric could take many paths in constructing their argument. Perhaps the student could ground their argument in historical precedent, claiming that presidents have always sought to expand the rhetorical capabilities of their position in the context of war, and President Trump’s use of twitter is just another iteration of that tradition.

Or, working with their colleagues in the quantitative realm, the burgeoning Genre Critic in Rhetorical Studies could first quantify the number of times President Trump tweeted about military action, then perhaps code for instances where his language matched that of previous declarations of war and where it differed, and then draw conclusions from there. Perhaps even doing a comparison between the use of war rhetoric on twitter between former President Obama and President Trump could reveal Trump’s addition or challenge to the existing genre.

For the creation of new modes of discourse, the internet’s rapid ascent cannot be overstated. Indeed, the internet created a mechanism to instantly disseminate culture, forever changing communication and what can be deemed culturally relevant. While seemingly ridiculous at first thought, the advent of memes presented scholars of genre and rhetoric a new mode of communication to examine. Through the mixture of images and text, memes express and articulate culture, constitute a shared identity, and can even make arguments. Although meme creation and proliferation is truly organic, memes contain a strikingly consistent internal dynamic, thereby creating a new genre of discourse to study.