The Impact of Social Isolation Essay (Critical Writing)

Social isolation has become a normal state of living for the world’s population in recent years. For many people, confinement has become a highly stressful situation, triggering their mental health issues, while for others became an opportunity to learn and grow. The recent article reviewed explores the impact of social isolation on a person, providing reliable data on the exact effect of such a notion on people and coping mechanisms to reduce its influence. This essay will summarize the story, adding relevant scientific evidence to ensure the credibility of the article.

Peterson, the author of the article, focused on the challenges the world faced with the pandemic’s restriction on social isolation, inviting Emilie Kossick, the manager of the Canadian Institute of Public Safety Research and Treatment, to talk about the notion from a doctoral perspective. The expert proceeded to state that social desolation has been a significant problem long before the lockdowns, providing examples such as the conditions of astronauts and older adults’ loneliness in care facilities, explaining that it did not receive much attention from researchers until COVID-19 (Peterson, 2021). For that reason, there are currently many available pieces of research that can help facilitate people endure the effects of communication limitations.

Among the physiological consequences of long-term isolation, Kossick indicates sleep pattern impairments and personality changes, in particular, the development of anxiety and depression. Indeed, multiple studies confirm the risks of mental health decrease, especially among children and adolescents who are constantly in need of socialization (Loades et al., 2020). The expert explains such impact to be caused by a decrease in brain activity in areas responsible for social skills and emotions. Therefore, social isolation negatively affects brain functions, causing multiple mental shifts.

Not only social functions are impacted by long-term confinement, but there is also a high possibility of developing chronic diseases as a result of low physical activity and the lack of socialization. Kossick offers the theory that the emergence of a higher likelihood of stroke, dementia, and heart diseases from isolation is attributed to human evolution as social creatures (Peterson, 2021). People continually interact with others, whether they want it or not, and instant depravity from such socialization radically affects mental and physical health.

Since the brain is not accustomed to functioning without interaction, people experience unpleasant consequences. Studies with certain participants confirmed that isolation evokes frustration, distresses the routine, and causes boredom (Brooks et al., 2020). Therefore, the author’s advice is to create a coping strategy to reduce the negative impact of isolation. She proposes to constantly plan one’s day, including hobbies and physical activities in daily life, as well as to keep in touch with friends and family (Peterson, 2021). Even though self-isolation is challenging for each person during the pandemic, as Kossick stated in the article, it is necessary to learn from such experience.

The article by Peterson is of utmost importance for all people who have experienced a decrease in their mental or physical health during the pandemic. It explains the most essential factors that influence a person’s state and why such a thing happens. Moreover, the author offers strategies that can facilitate coping with isolation and reduce its negative impact. Although the articles on the pandemic’s evolution can be frequently encountered, they rarely focus on the condition of healthy individuals. Mental and physical health must become a general priority during the lockdown, and to this end, Peterson’s article helps explain the symptoms people might experience and suggests the mechanisms to remain sane.

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet , 395 (10227), 912–920. Web.

Loades, M. E., Chatburn, E., Higson-Sweeney, N., Reynolds, S., Shafran, R., Brigden, A., Linney, C., McManus, M. N., Borwick, C., & Crawley, E. (2020). Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry , 59 (11). Web.

Peterson, J. (2021). Researchers with Sask. roots explore the impacts of long-term isolation . MSN. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, June 29). The Impact of Social Isolation. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-impact-of-social-isolation/

"The Impact of Social Isolation." IvyPanda , 29 June 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/the-impact-of-social-isolation/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'The Impact of Social Isolation'. 29 June.

IvyPanda . 2022. "The Impact of Social Isolation." June 29, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-impact-of-social-isolation/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Impact of Social Isolation." June 29, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-impact-of-social-isolation/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Impact of Social Isolation." June 29, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-impact-of-social-isolation/.

- Infamous Crimes: Laci Peterson's Murder

- “Why Don’t We Listen?” by J. Peterson

- Urban Politics. Paul Peterson's Policy Typology

- Criminal Law: U.S. v. Peterson

- Peterson Healthcare Facility Business Plan

- Solitary Confinement's Impact Discussion

- Chicago Peterson Ave Stores: Company Information

- International Trade of Peterson Advocates in Australia

- Discrimination: Peterson v. Wilmur Communications

- Solitary Confinement of Prisoners

- Cultural Heritage and Its Impact on Health Care Delivery

- Community Health Assessment: The City of Los Angeles

- An Evidence-Based Program for Female Offenders

- Evaluation of the Welsh National Exercise Referral Scheme

- Fundamentals of Evidence-Based Practice in Health Care

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 27 January 2021

The effects of social isolation on well-being and life satisfaction during pandemic

- Ruta Clair ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9828-9911 1 ,

- Maya Gordon 1 ,

- Matthew Kroon 1 &

- Carolyn Reilly 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 28 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

96k Accesses

144 Citations

161 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health humanities

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic placed many locations under ‘stay at home” orders and adults simultaneously underwent a form of social isolation that is unprecedented in the modern world. Perceived social isolation can have a significant effect on health and well-being. Further, one can live with others and still experience perceived social isolation. However, there is limited research on psychological well-being during a pandemic. In addition, much of the research is limited to older adult samples. This study examined the effects of perceived social isolation in adults across the age span. Specifically, this study documented the prevalence of social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the various factors that contribute to individuals of all ages feeling more or less isolated while they are required to maintain physical distancing for an extended period of time. Survey data was collected from 309 adults who ranged in age from 18 to 84. The measure consisted of a 42 item survey from the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale, Measures of Social Isolation (Zavaleta et al., 2017 ), and items specifically about the pandemic and demographics. Items included both Likert scale items and open-ended questions. A “snowball” data collection process was used to build the sample. While the entire sample reported at least some perceived social isolation, young adults reported the highest levels of isolation, χ 2 (2) = 27.36, p < 0.001. Perceived social isolation was associated with poor life satisfaction across all domains, as well as work-related stress, and lower trust of institutions. Higher levels of substance use as a coping strategy was also related to higher perceived social isolation. Respondents reporting higher levels of subjective personal risk for COVID-19 also reported higher perceived social isolation. The experience of perceived social isolation has significant negative consequences related to psychological well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

The effect of a prosocial environment on health and well-being during the first COVID-19 lockdown and a year later

Estherina Trachtenberg, Keren Ruzal, … Inbal Ben-Ami Bartal

Loneliness, social isolation, and pain following the COVID-19 outbreak: data from a nationwide internet survey in Japan

Keiko Yamada, Kenta Wakaizumi, … Takahiro Tabuchi

Social activity promotes resilience against loneliness in depressed individuals: a study over 14-days of physical isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia

Julie L. Ji, Julian Basanovic & Colin MacLeod

Introduction

In March 2020, the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic, prompting most governors in the United States to issue stay-at-home orders in an effort to minimize the spread of COVID-19. This was after several months of similar quarantine orders in countries throughout Asia and Europe. As a result, a unique situation arose, in which most of the world’s population was confined to their homes, with only medical staff and other essential workers being allowed to leave their homes on a regular basis. Several studies of previous quarantine episodes have shown that psychological stress reactions may emerge from the experience of physical and social isolation (Brooks et al., 2020 ). In addition to the stress that might arise with social isolation or being restricted to your home, there is also the stress of worrying about contracting COVID-19 and losing loved ones to the disease (Brooks et al., 2020 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ). For many families, this stress is compounded by the challenge of working from home while also caring for children whose schools had been closed in an effort to slow the spread of the disease. While the effects of social isolation has been reported in the literature, little is known about the effects of social isolation during a global pandemic (Galea et al., 2020 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ; Usher et al., 2020 ).

Social isolation is a multi-dimensional construct that can be defined as the inadequate quantity and/or quality of interactions with other people, including those interactions that occur at the individual, group, and/or community level (Nicholson, 2012 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ; Umberson and Karas Montez, 2010 ; Zavaleta et al., 2017 ). Some measures of social isolation focus on external isolation which refers to the frequency of contact or interactions with other people. Other measures focus on internal or perceived social isolation which refers to the person’s perceptions of loneliness, trust, and satisfaction with their relationships. This distinction is important because a person can have the subjective experience of being isolated even when they have frequent contact with other people and conversely they may not feel isolated even when their contact with others is limited (Hughes et al., 2004 ).

When considering the effects of social isolation, it is important to note that the majority of the existing research has focused on the elderly population (Nyqvist et al., 2016 ). This is likely because older adulthood is a time when external isolation is more likely due to various circumstances such as retirement, and limited physical mobility (Umberson and Karas Montez, 2010 ). During the COVID-19 pandemic the need for physical distancing due to virus mitigation efforts has exacerbated the isolation of many older adults (Berg-Weger and Morley, 2020 ; Smith et al., 2020 ) and has exposed younger adults to a similar experience (Brooks et al., 2020 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ). Notably, a few studies have found that young adults report higher levels of loneliness (perceived social isolation) even though their social networks are larger (Child and Lawton, 2019 ; Nyqvist et al., 2016 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ); thus indicating that age may be an important factor to consider in determining how long-term distancing due to COVID-19 will influence people’s perceptions of being socially isolated.

The general pattern in this research is that increased social isolation is associated with decreased life satisfaction, higher levels of depression, and lower levels of psychological well-being (Cacioppo and Cacioppo, 2014 ; Coutin and Knapp, 2017 ; Dahlberg and McKee, 2018 ; Harasemiw et al., 2018 ; Lee and Cagle, 2018 ; Usher et al., 2020 ). Individuals who experience high levels of social isolation may engage in self-protective thinking that can lead to a negative outlook impacting the way individuals interact with others (Cacioppo and Cacioppo, 2014 ). Further, restricting social networks and experiencing elevated levels of social isolation act as mediators that result in elevated negative mood and lower satisfaction with life factors (Harasemiw et al., 2018 ; Zheng et al., 2020 ). The relationship between well-being and feelings of control and satisfaction with one’s environment are related to psychological health (Zheng et al., 2020 ). Dissatisfaction with one’s home, resource scarcity such as food and self-care products, and job instability contribute to social isolation and poor well-being (Zavaleta et al., 2017 ).

Although there are fewer studies with young and middle aged adults, there is some evidence of a similar pattern of greater isolation being associated with negative psychological outcomes for this population (Bergin and Pakenham, 2015 ; Elphinstone, 2018 ; Liu et al., 2019 ; Nicholson, 2012 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ; Usher et al., 2020 ). There is also considerable evidence that social isolation can have a detrimental impact on physical health (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010 ; Steptoe et al., 2013 ). In a meta-analysis of 148 studies examining connections between social relationships and risk of mortality, Holt-Lunstad et al. ( 2010 ) concluded that the influence of social relationships on the risk for death is comparable to the risk caused by other factors like smoking and alcohol use, and greater than the risk associated with obesity and lack of exercise. Likewise, other researchers have highlighted the detrimental impact of social isolation and loneliness on various illnesses, including cardiovascular, inflammatory, neuroendocrine, and cognitive disorders (Bhatti and Haq, 2017 ; Xia and Li, 2018 ). Understanding behavioral factors related to positive and negative copings is essential in providing health guidance to adult populations.

Feelings of belonging and social connection are related to life satisfaction in older adults (Hawton et al., 2011 ; Mellor et al., 2008 ; Nicholson, 2012 ; Victor et al., 2000 ; Xia and Li, 2018 ). While physical distancing initiatives were implemented to save lives by reducing the spread of COVID-19, these results suggest that social isolation can have a negative impact on both mental and physical health that may linger beyond the mitigation orders (Berg-Weger and Morley, 2020 ; Brooks et al., 2020 ; Cava et al., 2005 ; Smith et al., 2020 ; Usher et al., 2020 ). It is therefore important that we document the prevalence of social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the various factors that contribute to individuals of all ages feeling more or less isolated, while they are required to maintain physical distancing for an extended period of time. It was hypothesized that perceived social isolation would not be limited to an older adult population. Further, it was hypothesized that perceived social isolation would be related to individual’s coping with the pandemic. Finally, it was hypothesized that the experience of social isolation would act as a mediator to life satisfaction and basic trust in institutions for individuals across the adult lifespan. The current study was designed to examine the following research questions:

Are there age differences in participants’ perceived social isolation?

Do factors like time spent under required distancing and worry about personal risk for illness have an association with perceived social isolation?

Is perceived social isolation due to quarantine and pandemic mitigation efforts related to life satisfaction?

Is there an association between perceived social isolation and trust of institutions?

Is there a difference in basic stressors and coping during the pandemic for individuals experiencing varying levels of perceived social isolation?

Participants

Participants were adults age 18 years and above. Individuals younger than 18 years were not eligible to participate in the study. There were no limitations on occupation, education, or time under mandatory “stay at home” orders. The researchers sought a sample of adults that was diverse by age, occupation, and ethnicity. The researchers sought a broad sample that would allow researchers to conduct a descriptive quantitative survey study examining factors related to perceived social isolation during the first months of the COVID-19 mitigation efforts.

Participants were asked to complete a 42-item electronic survey that consisted of both Likert-type items and open-ended questions. There were 20 Likert scale items, 3 items on a 3-point scale (1 = Hardly ever to 3 = Often) and 17 items on a 5-point scale (1 = Not at all satisfied to 4 = very satisfied, 0 = I don’t know), 11 multiple choice items, one of which had an available short response answer, and 11 short answer items.

Items were selected from Measures of Social Isolation (Zavaleta et al., 2017 ) that included 27 items to measure feelings of social isolation through the proxy variables of stress, trust, and life satisfaction. Trust was measured for government, business, and media. Life satisfaction examined overall feelings of satisfaction as well as satisfaction with resources such as food, housing, work, and relationships. Three items related to social isolation were chosen from the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale. Hughes et al. ( 2004 ) reported that these three items showed good psychometric validity and reliability for the construct of Loneliness.

There were a further 12 items from the authors specifically about circumstances regarding COVID-19 at the time of the survey. Participants answered questions about the length of time spent distancing from others, level of compliance with local regulations, primary news sources, whether physical distancing was voluntary or mandatory, how many people are in their household, work availability, methods of communication, feelings of personal risk of contracting COVID-19, possible changes in behavior, coping methods, stressors, and whether there are children over the age of 18 staying in the home.

This study was submitted to the Cabrini University Institutional Review Board and approval was obtained in March 2020. Researchers recruited a sample of people that varied by age, gender, and ethnicity by identifying potential participants across academic and non-academic settings using professional contact lists. A “snowball” approach to data gathering was used. The researchers sent the survey to a broad group of adults and requested that the participants send the survey to others they felt would be interested in taking part in research. Recipients received an email that contained a description of the purpose of the study and how the data would be used. Included at the end of the email was a link to the online survey that first presented the study’s consent form. Participants acknowledged informed consent and agreed to participate by opening and completing the survey.

At the end of the survey, participants were given the opportunity to supply an email to participate in a longitudinal study which consists of completing surveys at later dates. In addition, the sample was asked to forward the survey to their contacts who might be interested. Overall, the study took ~10 min to complete.

Demographics

Participants were 309 adults who ranged in age from 18 to 84 ( M = 38.54, s = 18.27). Data was collected beginning in 2020 from late March until early April. At the time of data collection distancing mandates were in place for 64.7% and voluntary for 34.6% of the sample, while 0.6% lived in places which had not yet outlined any pandemic mitigation policies. The average length of time distancing was slightly more than 2 weeks ( M = 14.91 days, s = 4.5) with 30 days as the longest reported time.

The sample identified mostly as female (80.3%), with males (17.8%) and those who preferred not to answer (1.9%) representing smaller numbers. The majority of the sample identified as Caucasian (71.5%). Other ethnic identities reported by participants included Hispanic/Latinx, African-American/Black, Asian/East Asian, Jewish/Jewish White-Passing, Multiracial/Multiethnic, and Country of Origin (Table 1 ). Individuals resided in the United States and Europe.

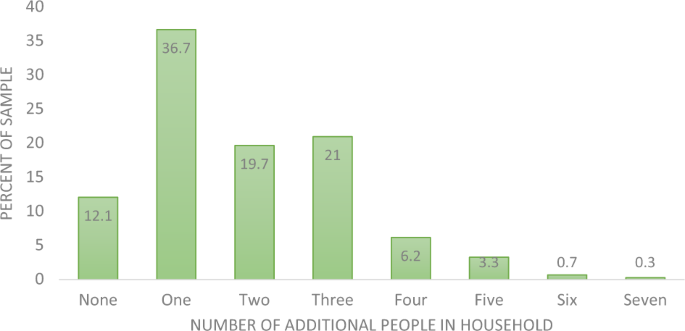

The majority of the sample lived in households with others (Fig. 1 ). More than one-third (36.7%) lived with one other person, 19.7% lived with two others, and 21% lived with three other people. People living alone comprised 12.1% of the sample. When asked about the presence of children under 18 years of age in the home, 20.5% answered yes.

Figure shows how many additional individuals live in the participant’s household in March 2020.

The highest level of education attained ranged from completion of lower secondary school (0.3%) to doctoral level (6.8%). Two thirds of the sample consisted of individuals with a Bachelor’s degree or above (Table 2 ).

Participants were asked to provide their occupation. The largest group identified themselves as professionals (26.5%), while 38.6% reported their field of work (Table 3 ). Students comprised 23.1% of the sample, while 11.1% reported that they were retired. Some of the occupations reported by the sample included nurses and physicians, lawyers, psychologists, teachers, mental health professionals, retail sales, government work, homemakers, artists across types of media, financial analysts, hairdresser, and veterinary support personnel. One person indicated that they were unemployed prior to the pandemic.

Social isolation and demographics

Spearman’s rank-order correlations were used to examine relationships between the three Likert scale items from the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale that measure social isolation. Feeling isolated from others was significantly correlated with lacking companionship ( r s = 0.45, p < 0.001) and feeling left out ( r s = 0.43, p < 0.001). The items related to lacking companionship and feeling left out were also significantly correlated ( r s = 0.39, p < 0.001).

Kruskal–Wallis tests were conducted to determine if the variables of time in required distancing and age were each related to the three levels of social isolation (hardly, sometimes, often). There were no significant findings between perceived social isolation and length of time in required distancing, χ 2 (2) = 0.024, p = 0.98.

A significant relationship was found between perceived social isolation and age, χ 2 (2) = 27.36, p < 0.001). Subsequently, pairwise comparisons were performed using Dunn’s procedure with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Adjusted p values are presented. Post hoc analysis revealed statistically significant differences in age between those with high levels of social isolation (Mdn = 25) and some social isolation (Mdn = 31) ( p = <0.001) and low isolation (Mdn = 46) ( p = 0.002). Higher levels of social isolation were associated with younger age.

Age was then grouped (18–29, 30–49, 50–69, 70+) and a significant relationship was found between social isolation and age, χ 2 (3) = 13.78, p = 0.003). Post hoc analysis revealed statistically significant differences in perceived social isolation across age groups. The youngest adults (age 18–29) reported significantly higher social isolation (Mdn = 2.4) than the two oldest groups (50–69 year olds: Mdn = 1.6, p = 004); age 70 and above: Mdn = 1.57), p = 0.01). The difference between the youngest adults and the next youngest (30–49) was not significant ( p = 0.09).

When asked if participants feel personally at risk for contracting SARS-CoV-2 61.2% reported that they feel at risk. A Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare social isolation experienced by those who reported feeling at risk and those who did not feel at risk. Individuals who feel at risk for infection reported more social isolation (Mdn = 2.0) than those that do not feel at risk (Mdn = 1.75), U = 9377, z = −2.43, p = 0.015.

Social isolation and life satisfaction

The relationship between level of social isolation and overall life satisfaction were examined using Kruskal–Wallis tests as the measure consisted of Likert-type items (Table 4 ).

Overall life satisfaction was significantly lower for those who reported greater social isolation ( χ 2 (2) = 50.56, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed statistically significant differences in life satisfaction scores between those with high levels of social isolation (Mdn = 2.82) and some social isolation (Mdn = 3.04) ( p ≤ 0.001) and between high and low isolation (Mdn = 3.47) ( p ≤ 0.001), but not between high levels of social isolation and some social isolation ( p = 0.09).

The pandemic added concern about access to resources such as food and 68% of the sample reported stress related to availability of resources. A significant relationship was found between social isolation and satisfaction with access to food, χ 2 (2) = 21.92, p < 0.001). Individuals reporting high levels of social isolation were the least satisfied with their food situation. Statistical difference were evident between high social isolation (Mdn = 3.28) and some social isolation (Mdn = 3.46) ( p = 0.003) and between high and low isolation (Mdn = 3.69) ( p < 0.001). Reporting higher levels of social isolation is associated with lower satisfaction with food.

As a result of stay at home orders, many participants were spending more time in their residences than prior to the pandemic. A significant relationship was found between social isolation and housing satisfaction, χ 2 (2) = 10.33, p = 0.006). Post hoc analysis revealed statistically a significant difference in housing satisfaction between those with high levels of social isolation (Mdn = 3.49) and low social isolation (Mdn = 3.75) ( p = 0.006). Higher levels of social isolation is associated with lower levels of satisfaction with housing.

Work life changed for many participants and 22% of participants reported job loss as a result of the pandemic. A significant relationship was found between social isolation and work satisfaction, χ 2 (2) = 21.40, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed individuals reporting high social isolation reported much lower satisfaction with work (Mdn = 2.53) than did those reporting low social isolation (Mdn = 3.27) ( p < 0.001) and moderate social isolation (Mdn = 3.03) ( p = 0.003).

Social isolation and trust of institutions

The relationship between social isolation and connection to community was measured using a Kruskal–Wallis test. A significant relationship was found between feelings of social isolation and connection to community ( χ 2 (2) = 13.97, p = 0.001. Post hoc analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in connection to community such that the group reporting higher social isolation (Mdn = 2.27, p = 0.001) reports less connection to their community than the group reporting low social isolation (Mdn = 2.93).

A significant relationship was found between social isolation and trust of central government institutions, χ 2 (2) = 10.46, p = 0.005). Post hoc analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in trust of central government between individuals reporting low social isolation (Mdn = 2.91) and those reporting high social isolation (Mdn = 2.32) ( p = 0.008) and moderate social isolation (Mdn = 2.48) ( p = 0.03). There was less trust of central government for the group reporting high social isolation. However, distrust of central government did not extend to local government institutions. There was no significant difference in trust of local government for low, moderate, and high social isolation groups, χ 2 (2) = 5.92, p = 0.052.

Trust levels of business was significantly different between groups that differed in feelings of social isolation, χ 2 (2) = 9.58, p = 0.008). Post hoc analysis revealed more trust of business institutions for the low social isolation group (Mdn = 3.10) compared to the group reporting high social isolation (Mdn = 2.62) ( p = 0.007).

Sixty-seven participants reported loss of a job as a result of COVID-19. A Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare social isolation experienced by those who had lost their job to those who had not. Individuals who experienced job loss reported more social isolation (Mdn = 2.26) than those that did not lose their job (Mdn = 1.80), U = 5819.5, z = −3.66 , p < 0.001.

Stress related to caring for an elderly family member was identified by 12% of the sample. A Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare social isolation experienced by those who reported that caring for an elderly family member is a stressor to those who had not. There was no significant finding, U = 4483, z = −1.28, p = 0.20. Similarly, there was no significant effect for caring for a child, U = 3568.5, z = −0.48, p = 0.63.

Coping strategies

Participants were asked to check off whether they were using virtual communication, exercise, going outdoors, and/or substances in order to cope with the challenges of distancing during pandemic. A Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare social isolation experienced by those who used substances as a coping strategy and those that did not. Individuals who reported substance use reported more social isolation (Mdn = 2.12) than those that did not (Mdn = 1.80), U = 6724, z = −2.01, p = 0.04.

There was no significant difference on Mann–Whitney U test for social isolation between those individuals who went outdoors to cope with pandemic versus those that did not, U = 5416, z = −0.72, p = 0.47. Similarly, there was no difference in social isolation between those individuals who used exercise as a coping tool and those that did not. Finally, there was no difference in social isolation between those that used virtual communication tools and those that did not, U = 7839.5, z = −0.56, p = 0.58. The only coping strategy which was significantly associated with social isolation was substance use.

While research has explored the subjective experience of social isolation, the novel experience of mass physical distancing as a result of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic suggests that social isolation is a significant factor in the public health crisis. The experience of social isolation has been examined in older populations but less often in middle-age and younger adults (Brooks et al., 2020 ; Smith and Lim, 2020 ). Perceived social isolation is related to numerous negative outcomes related to both physical and mental health (Bhatti and Haq, 2017 ; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010 , Victor et al., 2000 ; Xia and Li, 2018 ). Our findings indicate that younger adults in their 20s reported more social isolation than did those individuals aged 50 and older during physical distancing. This supports the findings of Nyqvist et al. ( 2016 ) that found teenagers and young adults in Finland reported greater loneliness than did older adults.

The experience of social isolation is related to a reduction in life satisfaction. Previous research has shown that feelings of social connection are related to general life satisfaction in older adults (Hawton et al., 2011 , Hughes et al., 2004 , Mellor et al., 2008 ; Victor et al., 2000 , Xia and Li, 2018 ). These findings indicate that perceived social isolation can be a significant mediator in life satisfaction and well-being across the adult lifespan during a global health crisis. Individuals reporting higher levels of social isolation experience less satisfaction with the conditions in their home.

During mandated “stay-at-home” conditions, the experience of work changed for many people. For many adults work is an essential aspect of identity and life satisfaction. The experience of individuals reporting elevated social isolation was also related to lower satisfaction with work. This study included a wide span of occupations involving both individuals required to work from home and essential workers continuing to work outside the home. Further, ~22% of the sample ( n = 67) reported job loss as a stressor related to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and reported elevated social isolation. As institutions and businesses consider whether remote work is an economically viable alternative to face-to-face offices once physical distancing mandates are ended, the needs of workers for social interaction should be considered.

Further, individuals reporting higher social isolation also indicated less connection to their community and lower satisfaction with environmental factors such as housing and food. Findings indicate that higher perceived social isolation is associated with broad dissatisfaction across social and life domains and perceptions of personal risk from COVID-19. This supports research that identified a relationship between social isolation and health-related quality of life outcomes (Hawton et al., 2011 , Victor et al., 2000 ). Perceptions of elevated social isolation are related to lower life satisfaction in functional and social domains.

Perceived social isolation is likewise related to trust of some institutions. While there was no effect for local government, individuals with higher perceived social isolation reported less trust of central government and of business. There is an association between higher levels of perceived social isolation and less connection to the community, lower life satisfaction, and less trust of large-scale institutions such as central government and businesses. As a result, the individuals who need the most support may be the most suspicious of the effectiveness of those institutions.

Coping strategies related to exercise, time spent outdoors, and virtual communication were not related to social isolation. However, individuals who reported using substances as a coping strategy reported significantly higher social isolation than did the group who did not indicate substance use as a coping strategy. Perceived social isolation was associated with negative coping rather than positive coping. This study shows that clinicians and health care providers should ask about coping strategies in order to provide effective supports for individuals.

There are several limitations that may limit the generalizability of the findings. The study is heavily female and this may have an effect on findings. In addition, the majority of the sample has a post-secondary degree and, as such, this study may not accurately reflect the broad experience of individuals during pandemic. Further, it cannot be ruled out that individuals reporting high levels of perceived social isolation may have experienced some social isolation prior to the pandemic.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study suggests that perceived social isolation is a significant element of health-related quality of life during pandemic. Perceived social isolation is not just an issue for older adults. Indeed, young adults appear to be suffering greatly from the distancing required to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2. The experience of social isolation is associated with poor life satisfaction across domains, work-related stress, lower trust of institutions such as central government and business, perceived personal risk for COVID-19, and higher levels of use of substances as a coping strategy. Measuring the degree of perceived social isolation is an important addition to wellness assessments. Stress and social isolation can impact health and immune function and so reducing perceived social isolation is essential during a time when individuals require strong immune function to fight off a novel virus. Further, it is anticipated that these widespread effects may linger as the uncertainty of the virus continues. As a result, we plan to follow participants for at least a year to examine the impact of SARS-CoV-2 on the well-being of adults.

Data availability

The dataset generated during and analyzed during the current study is not publicly available due to ethical restrictions and privacy agreements between the authors and participants.

Berg-Weger M, Morley J (2020) Loneliness and social isolation in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for gerontological social work. J Nutr Health Aging 24(5):456–458

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bergin A, Pakenham K (2015) Law student stress: relationships between academic demands, social isolation, career pressure, study/life imbalance, and adjustment outcomes in law students. Psychiatry Psychol Law 22:388–406

Article Google Scholar

Bhatti A, Haq A (2017) The pathophysiology of perceived social isolation: effects on health and mortality. Cureus 9(1):e994. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.994

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Brooks S, Webster R, Smith L, Woodland L, Wesseley S, Greenberg N, Rubin G (2020) The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395:912–920

Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S (2014) Social relationships and health: the toxic effects of perceived social isolation. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 8(2):58–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12087

Cava M, Fay K, Beanlands H, McCay E, Wignall R (2005) The experience of quarantine for individuals affected by SARS in Toronto. Public Health Nurs 22(5):398–406

Child ST, Lawton L (2019) Loneliness and social isolation among young and late middle age adults: associations with personal networks and social participation. Aging Mental Health 23:196–204

Coutin E, Knapp M (2017) Social isolation, loneliness, and health in old age. Health Soc Care Community 25:799–812

Dahlberg L, McKee KJ (2018) Social exclusion and well-being among older adults in rural and urban areas. Arch Gerontol Geriatrics 79:176–184

Elphinstone B (2018) Identification of a suitable short-form of the UCLA-Loneliness Scale. Austral Psychol 53:107–115

Galea S, Merchant R, Lurie N (2020) The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern Med 180(6):817–818

Harasemiw O, Newall N, Mackenzie CS, Shooshtari S, Menec V (2018) Is the association between social network types, depressive symptoms and life satisfaction mediated by the perceived availability of social support? A cross-sectional analysis using the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Aging Mental Health 23:1413–1422

Hawton A, Green C, Dickens A, Richards C, Taylor R, Edwards R, Greaves C, Campbell J (2011) The impact of social isolation on the health status and health-related quality of life of older people. Qual Life Res 20:57–67

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB (2010) Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 7:1–20

Hughes M, Waite L, Hawkley L, Cacioppo J (2004) A short scale of measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population-based studies. Res Aging 26(6):655–672

Lee J, Cagle JG (2018) Social exclusion factors influencing life satisfaction among older adults. J Poverty Soc Justice 26:35–50

Liu H, Zhang M, Yang Q, Yu B (2019) Gender differences in the influence of social isolation and loneliness on depressive symptoms in college students: a longitudinal study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 55:251–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01726-6

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Mellor D, Stokes M, Firth L, Hayashi Y, Cummins R (2008) Need for belonging, relationship satisfaction, loneliness, and life satisfaction. Personal Individ Differ 45(2008):213–218

Nicholson N (2012) A review of social isolation: an important but underassessed condition in older adults. J Prim Prev 33(2–3):137–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-012-0271-2

Nyqvist F, Victor C, Forsman A, Cattan M (2016) The association between social capital and loneliness in different age groups: a population-based study in Western Finland. BMC Public Health 16:542. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3248-x

Smith B, Lim M (2020) How the COVID-19 pandemic is focusing attention on loneliness and social isolation. Public Health Res Pract 30(2):e3022008. https://doi.org/10.17061/phrp3022008

Smith M, Steinman L, Casey EA (2020). Combatting social isolation among older adults in the time of physical distancing: the COVID-19 social connectivity paradox. Front Public Health https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00403

Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J (2013) Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110(15):5797–5801. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1219686110

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Umberson D, Karas Montez J (2010) Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav 51:S54–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510383501

Usher K, Bhullar N, Jackson D (2020). Life in the pandemic: social isolation and mental health. J Clin Nurs https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15290

Victor C, Scambler S, Bond J, Bowling A (2000) Being alone in later life: loneliness, social isolation and living alone. Rev Clin Gerontol 10(4):407–417. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959259800104101

Xia N, Li H (2018) Loneliness, social isolation, and cardiovascular health. Antioxid Redox Signal 28(9):837–851

Zavaleta D, Samuel K, Mills CT (2017) Measures of social isolation. Soc Indic Res 131(1):367–391

Zheng L, Miao M, Gan Y (2020). Perceived control buffers the effects of the covid-19 pandemic on general health and life satisfaction: the mediating role of psychological distance. Appl Psychol https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12232

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Cabrini University, Radnor, USA

Ruta Clair, Maya Gordon, Matthew Kroon & Carolyn Reilly

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors jointly supervised and contributed to this work.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ruta Clair .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Clair, R., Gordon, M., Kroon, M. et al. The effects of social isolation on well-being and life satisfaction during pandemic. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8 , 28 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00710-3

Download citation

Received : 29 August 2020

Accepted : 07 January 2021

Published : 27 January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00710-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Assessing the impact of covid-19 on self-reported levels of depression during the pandemic relative to pre-pandemic among canadian adults.

- Rasha Elamoshy

- Marwa Farag

Archives of Public Health (2024)

Associations between social networks, cognitive function, and quality of life among older adults in long-term care

- Laura Dodds

- Carol Brayne

- Joyce Siette

BMC Geriatrics (2024)

Locked Down: The Gendered Impact of Social Support on Children’s Well-Being Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Jasper Dhoore

- Bram Spruyt

- Jessy Siongers

Child Indicators Research (2024)

Life Satisfaction during the Second Lockdown of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany: The Effects of Local Restrictions and Respondents’ Perceptions about the Pandemic

- Lisa Schmid

- Pablo Christmann

- Carolin Thönnissen

Applied Research in Quality of Life (2024)

Loneliness and trust issues reshape mental stress of expatriates during early COVID-19: a structural equation modelling approach

- Md Arif Billah

- Sharmin Akhtar

- Md. Nuruzzaman Khan

BMC Psychology (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

- Trust vs. Mistrust

- Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt

- Initiative vs. Guilt

- Industry vs. Inferiority

- Identity vs. Confusion

- Intimacy vs. Isolation

- Generativity vs. Stagnation

- Integrity vs. Despair

Intimacy vs. Isolation: Psychosocial Stage 6

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

What Is Intimacy?

Benefits of intimacy, consequences of isolation, how to build intimacy, how to overcome isolation.

- Next in Psychosocial Development Guide Generativity vs. Stagnation in Psychosocial Development

Intimacy vs. isolation is the sixth stage of Erik Erikson's theory of psychosocial development , which happens after the fifth stage of identity vs. role confusion. The intimacy vs. isolation stage takes place during young adulthood between the ages of approximately 19 and 40.

The major conflict at this stage of life centers on forming intimate, loving relationships with other people. Success at this stage leads to fulfilling relationships. Struggling at this stage, on the other hand, can result in feelings of loneliness and isolation.

- Psychosocial Conflict : Intimacy versus isolation

- Major Question : "Will I be loved or will I be alone?"

- Basic Virtue : Love

- Important Event(s) : Romantic relationships

Erikson believed that it was vital to develop close, committed relationships with other people. As people enter adulthood, these emotionally intimate relationships play a critical role in a person's emotional well-being.

What does Erikson mean by intimacy? While the word intimacy is closely associated with sex for many, it encompasses much more than that. Erikson described intimate relationships as those characterized by closeness, honesty, and love.

Romantic and sexual relationships can be an important part of this stage of life, but intimacy is more about having close, loving relationships. It includes romantic partners, but it can also encompass close, enduring friendships with people outside of your family.

An example of intimacy vs. isolation would be one person forming health relationships with romantic partners in adulthood as well as a circle of friends, acquaintances, family members, and others. Isolation, on the other hand, would be marked by a lack of social connections, poor or unhealthy relationships, and a general lack of social social support.

People who are successful in resolving the conflict of the intimacy versus isolation stage have:

- Close romantic relationships

- Deep, meaningful connections

- Enduring connections with other people

- Positive relationships with family and friends

- Strong relationships

People who navigate this period of life successfully are able to forge fulfilling relationships with other people. This plays an important role in creating supportive social networks that are important for both physical and mental health throughout life.

What Causes Intimacy vs. Isolation?

How do you develop intimacy vs. isolation? Intimacy requires being able to share parts of yourself with others, as well as the ability to listen to and support other people. These relationships are reciprocal —you are sharing parts of yourself, and others are sharing with you.

When this happens successfully, you gain the support, intimacy, and companionship of another person. But sometimes things don't go so smoothly. You might experience rejection or other responses that cause you to withdraw. It might harm your confidence and self-esteem, making you warier of putting yourself out there again in the future.

Isolation can happen for a number of reasons. Factors that may increase your risk of becoming lonely or isolated include:

- Childhood experiences including neglect or abuse

- Divorce or death of a partner

- Fear of commitment

- Fear of intimacy

- Inability to open up

- Past relationships

- Troubles with self-disclosure

No matter what the cause, it can have a detrimental impact on your life. It may lead to feelings of loneliness and even depression .

Strong and deep romantic relationships

Close relationships with friends and family

Strong social support network

Poor romantic relationships and no deep intimacy

Few or no relationships with friends and family

Weak social support network

Struggling in this stage of life can result in loneliness and isolation. Adults who struggle with this stage experience:

- Few or no friendships

- Lack of intimacy

- Lack of relationships

- Poor romantic relationships

- Weak social support

They might never share deep intimacy with their partners or might even struggle to develop any relationships at all. This can be particularly difficult as these individuals watch friends and acquaintances fall in love, get married, and start families.

Loneliness can affect overall health in other ways. For example, socially isolated people tend to have unhealthier diets, exercise less, experience greater daytime fatigue, and have poorer sleep.

Loneliness and isolation can lead to a wide range of negative health consequences including:

- Cardiovascular disease

- Substance misuse

If you are having suicidal thoughts, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 for support and assistance from a trained counselor. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger, call 911.

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

Learning to be open and sharing with others is an important part of the intimacy versus isolation stage. Some of the other important tasks that can play a role in succeeding or struggling at this point of development include:

- Being intimate : This is more than just engaging in sex; it means forging emotional intimacy and closeness. Intimacy does not necessarily have to be with a sexual partner. People can also gain intimacy from friends and loved ones.

- Caring for others : It is essential to be able to care about the needs of others. Relationships are reciprocal. Getting love is important at this stage, but so is giving it.

- Making commitments : Part of being able to form strong relationships involves being able to commit to others for the long term.

- Self-disclosure : This involves sharing part of the self with others, while still maintaining a strong sense of self-identity.

Importance of Sense of Self

Things learned during earlier stages of development also play a role in being able to have healthy adult relationships. For example, Erikson believed that having a fully formed sense of self (established during the previous identity versus role confusion stage ) was essential to being able to form intimate relationships.

People with a poor sense of self tend to have less committed relationships and are more likely to experience emotional isolation, loneliness, and depression.

Such findings suggest that having a strong sense of who you are is important for developing lasting future relationships. This self-awareness can play a role in the type of relationships you forge as well as the strength and durability of those social connections.

If you are struggling with feelings of isolation, there are things that you can do to form closer relationships with other people:

Avoid Negative Self-Talk

The things we tell ourselves can have an impact on our ability to be confident in relationships, particularly if those thoughts are negative. When you catch yourself having this type of inner dialogue, focus on replacing negative thoughts with more realistic ones.

Build Skills

Sometimes practicing social skills can be helpful when you are working toward creating new relationships. Consider taking a course in social skill development or try practicing your skills in different situations each day.

Determine What You Like

Research suggests that factors such as mutual interests and personality similarity play important roles in friendships. Knowing your interests and then engaging in activities around those interests is one way to build lasting friendships. If you enjoy sports, for example, you might consider joining a local community sports team.

Evaluate Your Situation

What are your needs? What type of relationship are you seeking? Figuring out what you are looking for in a partner or friend can help you determine how you should go about looking for new relationships.

Practice Self-Disclosure

Being able to share aspects of yourself can be difficult, but you can get better at it through practice. Consider things you would be willing to share about yourself with others, then practice. Remember that listening to others is an essential part of this interaction as well.

A Word From Verywell

Healthy relationships are important for both your physical and emotional well-being. The sixth stage of Erikson's psychosocial theory of development focuses on how these critical relationships are forged. Those who are successful at this stage are able to forge deep relationships and social connections with other people.

If you are struggling with forming healthy, intimate relationships, talking to a therapist can be helpful. A mental health professional can help you determine why you have problems forming or maintaining relationships and develop new habits that will help your forge these important connections.

Schrempft S, Jackowska M, Hamer M, Steptoe A. Associations between social isolation, loneliness, and objective physical activity in older men and women . BMC Public Health . 2019;19(1):74. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-6424-y

Hämmig O. Health risks associated with social isolation in general and in young, middle and old age [published correction appears in PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0222124]. PLoS One . 2019;14(7):e0219663. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0219663

Mushtaq R, Shoib S, Shah T, Mushtaq S. Relationship between loneliness, psychiatric disorders and physical health? A review on the psychological aspects of loneliness . J Clin Diagn Res . 2014;8(9):WE01–WE4. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2014/10077.4828

Campbell K, Holderness N, Riggs M. Friendship chemistry: An examination of underlying factors . Soc Sci J . 2015;52(2):239-247. doi:10.1016/j.soscij.2015.01.005

Erikson EH. Childhood and Society . W. W. Norton & Company; 1950.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Home / Essay Samples / Social Issues / Racism / Social Isolation

Social Isolation Essay Examples

Racial equality & unemployment rate in america.

American, at its prime, seeks the idea that what we look like and where we come from should not decide the aid, concerns, or duties that we have in our society. Because we think that all people are created equal in rights, dignity, and the...

A Theme of Social Isolation in Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte and Sleep by Haruki Murakami

The role of isolation in one’s life may derive from their own personal thoughts or the people they associate with. Most importantly, it can be caused by the people that claim to genuinely love and care for them. The concept of isolation is generally an...

The Contribution of Technology to Social Isolation

Think about a world today that would have no internet, imaging how chaotic and disconnecting the life in the world would be. The internet has changed the world in unimaginable ways that were only works of dreams and imagination in the past. Technology has grown...

Social Isolation in Facebook Group Chats

“In the digital age, information is power. The Internet is the great equalizer for those who are seeking to broaden their communities and improve their lives” (Rappler, 2016). Electronic social networks, like Messenger, WhatsApp, and other networking sites have contributed a large portion for an...

Social Isolation in Winesburg, Ohio by Sherwood Anderson

People of all ages feel an immense desire to fit into the world around them. Outcasts are apart of every society. Outcasts in society do not choose their position, but instead, society itself chooses it for them. An outcast is usually the type of person...

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison: the Impact of Our View of Ourselves on Our Life

A woman who faces cruelty and suffering racial abuse tries to overcome herself. Morrison shows us a girl’s point of view, and the struggles she faces throughout the book such as the two hurtful rapes. Her name is Pecola she is a young eleven-year-old African...

Theory of Slavery as a Kind of Social Death

The Orlando theory of slavery as a social death is among the first and major type of full scale comparative study that is attached to different slavery aspects. In his work which is capable of drawing on one of the most fundamental tribal, ancient together...

The Ideas of Racism Eradication

Racism is a phenomenon that has been and continues to be a critical issue of concern for societies around the world. The concept emerged in the Western thought around the 1800 and it is mainly aided by ideological and cultural factors. The earliest usage of...

Trying to find an excellent essay sample but no results?

Don’t waste your time and get a professional writer to help!

You may also like

- World Hunger

- Homelessness

- Affirmative Action

- Illegal Immigration

- Martin Luther King Essays

- Letter From Birmingham Jail Essays

- White Privilege Essays

- Racial Discrimination Essays

- Black Lives Matter Essays

- Gay Marriage Essays

- Capital Punishment Essays

- Cruelty to Animals Essays

- Pro Life Essays

- Discrimination Essays

samplius.com uses cookies to offer you the best service possible.By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .--> -->