Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Social Norms — Social Norms In Society

Social Norms in Society

- Categories: Social Norms

About this sample

Words: 654 |

Published: Mar 19, 2024

Words: 654 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

The functions of social norms, the influence of social norms on behavior, limitations and potential for change.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 985 words

2 pages / 1005 words

3 pages / 1591 words

3 pages / 1484 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Social Norms

Implicit bias, an intrinsic component of human cognition, holds a significant role in shaping our attitudes, beliefs, and actions without conscious awareness. This essay delves deeply into the definition of implicit bias, [...]

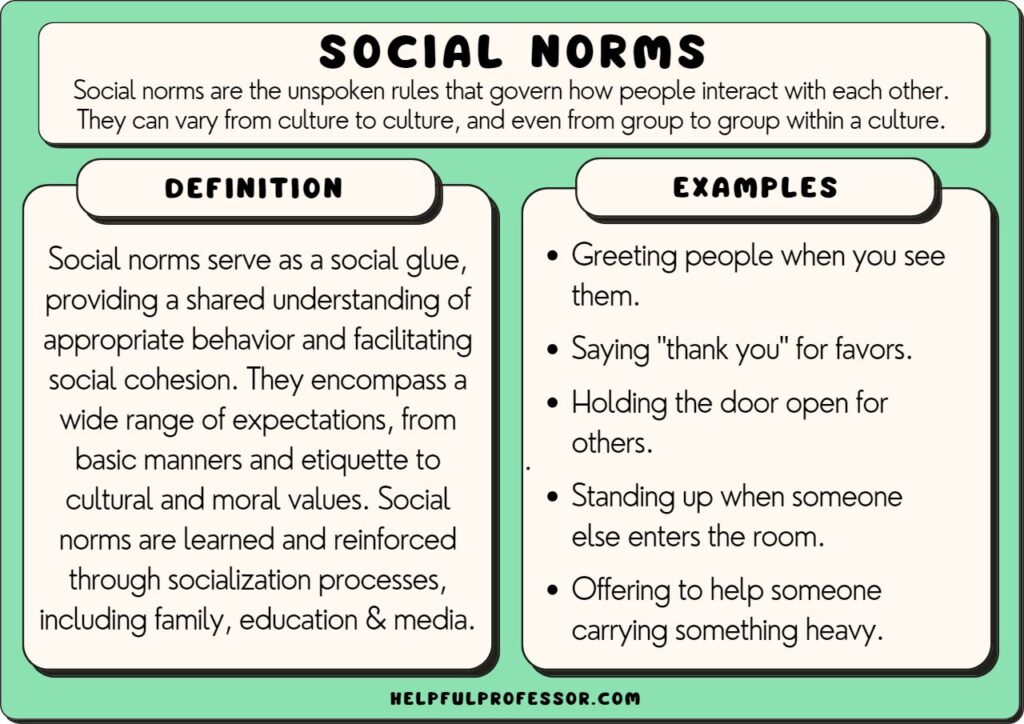

Social norms are the unwritten rules that govern behavior in a society. They dictate how individuals should act, dress, and speak in various situations. These norms are essential for maintaining order and cohesion within a [...]

Social norms are the unwritten rules that govern acceptable behavior in a society. Violating these norms can lead to social disapproval or even punishment. However, there are times when breaking social norms can be a powerful [...]

Norms and social norms are powerful forces that shape our behavior and guide our social interactions. They provide a sense of order, cohesion, and predictability in society. Norms act as social guidelines, ensuring that [...]

While many of us may like to believe that our society today as we know it has advanced in many ways beyond the thoughts and beliefs of the colonial era and the time of slavery, this is unfortunately not the case. In many ways, [...]

Informal norms are unwritten rules and expectations that guide social behavior within a community or society. While formal norms are explicitly stated laws and regulations, informal norms are more subtle and often based on [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Social Norms

Social norms, the informal rules that govern behavior in groups and societies, have been extensively studied in the social sciences. Anthropologists have described how social norms function in different cultures (Geertz 1973), sociologists have focused on their social functions and how they motivate people to act (Durkheim 1895 [1982], 1950 [1957]; Parsons 1937; Parsons & Shils 1951; James Coleman 1990; Hechter & Opp 2001), and economists have explored how adherence to norms influences market behavior (Akerlof 1976; Young 1998a). More recently, also legal scholars have touted social norms as efficient alternatives to legal rules, as they may internalize negative externalities and provide signaling mechanisms at little or no cost (Ellickson 1991; Posner 2000).

With a few exceptions, the social science literature conceives of norms as exogenous variables. Since norms are mainly seen as constraining behavior, some of the key differences between moral, social, and legal norms—as well as differences between norms and conventions—have been blurred. Much attention has instead been paid to the conditions under which norms will be obeyed. Because of that, the issue of sanctions has been paramount in the social science literature. Moreover, since social norms are seen as central to the production of social order or social coordination, research on norms has been focused on the functions they perform. Yet even if a norm may fulfill important social functions (such as welfare maximization or the elimination of externalities), it cannot be explained solely on the basis of the functions it performs. The simplistic functionalist perspective has been rejected on several accounts; in fact, even though a given norm can be conceived as a means to achieve some goal, this is usually not the reason why it emerged in the first place (Elster 1989a, 1989b). Moreover, although a particular norm may persist (as opposed to emerge) because of some positive social function it fulfills, there are many others that are inefficient and even widely unpopular.

Philosophers have taken a different approach to norms. In the literature on norms and conventions, both social constructs are seen as the endogenous product of individuals’ interactions (Lewis 1969; Ullmann-Margalit 1977; Vandershraaf 1995; Bicchieri 2006). Norms are represented as equilibria of games of strategy, and as such they are supported by a cluster of self-fulfilling expectations. Beliefs, expectations, group knowledge and common knowledge have thus become central concepts in the development of a philosophical view of social norms. Paying attention to the role played by expectations in supporting social norms has helped differentiate between social norms, conventions, and descriptive norms: an important distinction often overlooked in the social science accounts, but crucial when we need to diagnose the nature of a pattern of behavior in order to intervene on it.

1. General Issues

2. early theories: socialization, 3. early theories: social identity, 4. early theories: cost-benefit models, 5. game-theoretic accounts, 6. experimental evidence, 7. evolutionary models, 8. conclusion, other internet resources, related entries.

Social norms, like many other social phenomena, are the unplanned result of individuals’ interaction. It has been argued that social norms ought to be understood as a kind of grammar of social interactions. Like a grammar, a system of norms specifies what is acceptable and what is not in a society or group. And, analogously to a grammar, it is not the product of human design. This view suggests that a study of the conditions under which norms come into being—as opposed to one stressing the functions fulfilled by social norms—is important to understand the differences between social norms and other types of injunction (such as hypothetical imperatives, moral codes, or legal rules).

Another important issue often blurred in the literature on norms is the relationship between normative beliefs and behavior. Some authors identify norms with observable, recurrent patterns of behavior. Others only focus on normative beliefs and expectations. Such accounts find it difficult to explain the complexity and heterogeneity of norm-driven behaviors, as they offer an explanation of conformity that is at best partial.

Some popular accounts of why social norms exist are the following. Norms are efficient means to achieve social welfare (Arrow 1971; Akerlof 1976), prevent market failures (Jules Coleman 1989), or cut social costs (Thibaut & Kelley 1959; Homans 1961); norms are either Nash equilibria of coordination games or cooperative equilibria of prisoner’s dilemma-type games (Lewis 1969; Ullmann-Margalit 1977), and as such they solve collective action problems.

Akerlof’s (1976) analysis of the norms that regulate land systems is a good example of the tenet that “norms are efficient means to achieve social welfare”. Since the worker is much poorer and less liquid than the landlord, it would be more natural for the landlord rather than the tenant to bear the risk of crop failure. This would be the case if the landlord kept all the crops, and paid the worker a wage (i.e., the case of a “wage system”). Since the wage would not directly depend on the worker’s effort, this system leaves no incentive to the worker for any effort beyond the minimum necessary. In sharecropping, on the contrary, the worker is paid both for the effort and the time he puts in: a more efficient arrangement in that it increases production.

Thibaut and Kelley’s (1959) view of norms as substitutes for informal influence has a similar functionalist flavor. As an example, they consider a repeated battle of the sexes game. In this game, some bargaining is necessary for each party to obtain, at least occasionally, the preferred outcome. The parties can engage in a costly sequence of threats and promises, but it seems better to agree beforehand on a rule of behavior, such as alternating between the respectively preferred outcomes. Rules emerge because they reduce the costs involved in face-to-face personal influence.

Likewise, Ullman-Margalit (1977) uses game theory to show that norms solve collective action problems, such as prisoner’s dilemma-type situations; in her own words, “… a norm solving the problem inherent in a situation of this type is generated by it” (1977: 22). In a collective action problem, self-centered rational choices produce a Pareto-inefficient outcome. Pareto-efficiency is restored by means of norms backed by sanctions. James Coleman (1990), too, believes that norms emerge in situations in which there are externalities, that is, in all those cases in which an activity produces negative (positive) effects on other parties, without this being reflected in direct compensation; thus the producer of the externality pays no cost for (reaps no benefit from) the unintended effect of their activity. A norm solves the problem by regulating the externality-producing activity, introducing a system of sanctions (rewards).

Also Brennan, Eriksson, Goodin, and Southwood (2013) argue that norms have a function. Norms function to hold us accountable to each other for adherence to the principles that they cover. This may or may not create effective coordination over any given principle, but they place us in positions where we may praise and blame people for their behaviors and attitudes. This function of accountability, they argue, can help create another role for norms, which is imbuing practices with social meaning. This social meaning arises from the expectations that we can place on each other for compliance, and the fact that those behaviors can come to represent shared values, and even a sense of shared identity. This functional role of norms separates it from bare social practices or even common sets of desires, as those non-normative behaviors don’t carry with them the social accountability that is inherent in norms. The distinctive feature of the Brennan et al. account of norms is the centrality of accountability: this feature is what distinguishes norms from other social practices.

All of the above are examples of a functionalist explanation of norms. Functionalist accounts are sometimes criticized for offering a post hoc justification for the existence of norms (i.e., the mere presence of a norm does not justify inferring that that norm exists to accomplish some social function). Indeed, a purely functionalist view may not account for the fact that many social norms are harmful or inefficient (e.g., discriminatory norms against women and minorities), or are so rigid as to prevent the fine-tuning that would be necessary to accommodate new cases. There, one would expect increasing social pressure to abandon such norms.

According to some authors, we can explain the emergence of norms without any reference to the functions they eventually come to perform. Since the norms that are most interesting to study are those that emerge naturally from individuals’ interactions (Schelling 1978), an important theoretical task is to analyze the conditions under which such norms come into being. Because norms often provide a solution to the problem of maintaining social order—and social order requires cooperation—many studies on the emergence and dynamics of norms have focused on cooperation. Norms of honesty, loyalty, reciprocity and promise-keeping are indeed important to the smooth functioning of social groups. One hypothesis is that such cooperative norms emerge in close-knit groups where people have ongoing interactions with each other (Hardin 1982). Evolutionary game theory provides a useful framework for investigating this hypothesis, since repeated games serve as a simple approximation of life in a close-knit group (Axelrod 1984, 1986; Skyrms 1996; Gintis 2000). In repeated encounters people have an opportunity to learn from each other’s behavior, and to secure a pattern of reciprocity that minimizes the likelihood of misperception. In this regard, it has been argued that the cooperative norms likely to develop in close-knit groups are simple ones (Alexander 2000, 2005, 2007); in fact, delayed and disproportionate punishment, as well as belated rewards, are often difficult to understand and hence ineffective. Although norms originate in small, close-knit groups, they often spread well beyond the narrow boundaries of the original group. The challenge thus becomes one of explaining the dynamics of the norm propagation from small groups to large populations.

If norms can thrive and spread, they can also die out. A poorly understood phenomenon is the sudden and unexpected change of well-established patterns of behavior. For example, smoking in public without asking for permission has become unacceptable, and only a few years ago nobody would have worried about using gender-laden language. One would expect inefficient norms (such as discriminatory norms against women and minorities) to disappear more rapidly and with greater frequency than more efficient norms. However, Bicchieri (2016) points out that inefficiency is not a sufficient condition for a norm’s demise. This can be seen by the study of crime and corruption: corruption results in huge social costs, but such costs—even when they take a society to the brink of collapse—are not enough to generate an overhaul of the system. Muldoon (2018a, 2018b, 2020) has argued that social norms are a challenging form of social regulation precisely because there is no simple way to intentionally modify a social norm, as one can with a law or institutional rule. Social norms can even shape one's understanding of how much agency one has (Muldoon 2017).

An influential view of norms considers them as clusters of self-fulfilling expectations (Schelling 1960), in that some expectations often result in behavior that reinforces them. A related view emphasizes the importance of conditional preferences in supporting social norms (Sugden 2000). In particular, according to Bicchieri’s (2006) account, preferences for conformity to social norms are conditional on “empirical expectations” (i.e., first-order beliefs that a certain behavior will be followed) as well as “normative expectations” (i.e., second-order beliefs that a certain behavior ought to be followed). Thus, norm compliance results from the joint presence of a conditional preference for conformity and the belief that other people will conform as well as approve of conformity.

Note that characterizing norms simply as clusters of expectations might be misleading; similarly, a norm cannot simply be identified with a recurrent behavioral pattern either. If we were to adopt a purely behavioral account of norms there would be no way to distinguish shared rules of fairness from, say, the collective morning habit of tooth brushing. After all, such a practice does not depend on whether one expects others to do the same; however, one would not even try to ask for a salary proportionate to one’s education, if one expected compensation to merely follow a seniority rule. In fact, there are behavioral patterns that can only be explained by the existence of norms, even if the behavior prescribed by the norm in question is currently unobserved. For example, in a study of the Ik people, Turnbull (1972) reported that starved hunters-gatherers tried hard to avoid situations where their compliance with norms of reciprocity was expected. Thus they would go out of their way not to be in the position of gift-taker, and hunted alone so that they would not be forced to share their prey with anyone else. Much of the Ik’s behavior could be explained as a way of eluding existing reciprocity norms.

There are many other instances of discrepancies between expectations and behavior . For example, it is remarkable to observe how often people expect others to act selfishly, even when they are prepared to act altruistically themselves (Miller & Ratner 1996). Studies have shown that people’s willingness to give blood is not altered by monetary incentives, but typically those very people who are willing to donate blood for free expect others to donate blood only in the presence of monetary rewards. Similarly, all the interviewed landlords answered positively to a question about whether they would rent an apartment to an unmarried couple; however, they estimated that only 50% of other landlords would accept unmarried couples as tenants (Dawes 1972). Such cases of pluralistic ignorance are rather common; what is puzzling is that people may expect a given norm to be upheld in the face of personal evidence to the contrary (Bicchieri & Fukui 1999). Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting that people who donate blood, tip on a foreign trip, give money to beggars or return a lost wallet often attempt to downplay their altruistic behavior (by supplying selfish motives that seemingly align their actions with a norm of self-interest; Wuthnow 1991, 77).

In a nutshell, norms refer to actions over which people have control, and are supported by shared expectations about what should or should not be done in different types of social situations. However, norms cannot be identified just with observable behavior, nor can they merely be equated with normative beliefs.

The varying degrees of correlation between normative beliefs and actions are an important factor researchers can use to differentiate among various types of norms. Such a correlation is also a key element to consider when critically assessing competing theories of norms: we begin by surveying the socialized actor theory, the social identity theory, and some early rational choice (cost-benefit) models of conformity.

In the theory of the socialized actor (Parsons 1951), individual action is intended as a choice among alternatives. Human action is understood within a utilitarian framework as instrumentally oriented and utility maximizing. Although a utilitarian setting does not necessarily imply a view of human motives as essentially egoistic, this is the preferred interpretation of utilitarianism adopted by Talcott Parsons and much contemporary sociology. In this context, it becomes crucial to explain through which mechanisms social order and stability are attained in a society that would otherwise be in a permanent Hobbesian state of nature. In short, order and stability are essentially socially derived phenomena, brought about by a common value system —the “cement” of society. The common values of a society are embodied in norms that, when conformed to, guarantee the orderly functioning and reproduction of the social system. In the Parsonian framework norms are exogenous: how such a common value system is created and how it may change are issues left unexplored. The most important question is rather how norms get to be followed, and what prompts rational egoists to abide by them. The answer given by the theory of the socialized actor is that people voluntarily adhere to the shared value system, because it is introjected to form a constitutive element of the personality itself (Parsons 1951).

In Parsons’ own words, a norm is

a verbal description of a concrete course of action, … , regarded as desirable, combined with an injunction to make certain future actions conform to this course. (1937: 75)

Norms play a crucial role in individual choice since—by shaping individual needs and preferences—they serve as criteria for selecting among alternatives. Such criteria are shared by a given community and embody a common value system. People may choose what they prefer, but what they prefer in turn conforms to social expectations: norms influence behavior because, through a process of socialization that starts in infancy, they become part of one’s motives for action. Conformity to standing norms is a stable, acquired disposition that is independent of the consequences of conforming. Such lasting dispositions are formed by long-term interactions with significant others (e.g., one’s parents): through repeated socialization, individuals come to learn and internalize the common values embodied in the norms. Internalization is conceived as the process by which people develop a psychological need or motive to conform to a set of shared norms. When norms are internalized norm-abiding behavior will be perceived as good or appropriate, and people will typically feel guilt or shame at the prospect of behaving in a deviant way. If internalization is successful external sanctions will play no role in eliciting conformity and, since individuals are motivated to conform, it follows that normative beliefs and actions will be consistent.

Although Parsons’ analysis of social systems starts with a theory of individual action, he views social actors as behaving according to roles that define their identities and actions (through socialization and internalization). The goal of individual action is to maximize satisfaction. The potential conflict between individual desires and collective goals is resolved by characterizing the common value system as one that precedes and constrains the social actor. The price of this solution is the disappearance of the individual actor as the basic unit of analysis. Insofar as individuals are role-bearers, in Parsons’ theory it is social entities that act: entities that are completely detached from the individual actions that created them. This consideration forms the basis for most of the criticisms raised against the theory of the socialized actor (Wrong 1961); such criticisms are typically somewhat abstract as they are cast in the framework of the holism/individualism controversy.

On the other hand, one may easily verify whether empirical predictions drawn from the socialized actor theory are supported by experimental evidence. For instance, the following predictions can be derived from the theory and easily put to test. (a) Norms will change very slowly and only through intensive social interaction. (b) Normative beliefs are positively correlated to actions; whenever such beliefs change, behavior will follow. (c) If a norm is successfully internalized, expectations of others’ conformity will have no effect on an individual’s choice to conform.

Some of the above statements are not supported by empirical evidence from social psychology. For example, it has been shown that there may not be a relation between people’s normative beliefs (or attitudes) and what people in fact do. In this respect, it should be noted that experimental psychologists have generally focused on “attitudes”, that is, “evaluative feelings of pro or con, favorable or unfavorable, with regard to particular objects” (where the objects may be “concrete representations of things or actions, or abstract concepts”; Insko & Schopler 1967: 361–362). As such, the concept of attitude is quite broad: it includes normative beliefs, as well as personal opinions and preferences. That said, a series of field experiments has provided evidence contrary to the assumption that attitudes and behaviors are closely related. LaPiere (1934) famously reported a sharp divergence between the widespread anti-Chinese attitudes in the United States and the tolerant behavior he witnessed. Other studies have pointed to inconsistencies between an individual’s stated normative beliefs and her actions (Wicker 1969): several reasons may account for such a discrepancy. For example, studies of racial prejudice indicate that normative beliefs are more likely to determine behavior in long-lasting relationships, and least likely to determine behavior in the transient situations typical of experimental studies (Harding et al. 1954 [1969]; Gaertner & Dovidio 1986). Warner and DeFleur (1969) reported that the main variable affecting discriminatory behavior is one’s belief about what society (e.g., most other people) says one should do, as opposed to what one personally thinks one should do.

In brief, the social psychology literature provides mixed evidence in support of the claim that an individual’s normative beliefs and attitudes influence her actions. Such studies, however, do not carefully discriminate among various types of normative beliefs. In particular, one should distinguish between “personal normative beliefs” (i.e., beliefs that a certain behavior ought to be followed) and “normative expectations” (i.e., what one believes others believe ought to be done, that is, a second-order belief): it then becomes apparent that oftentimes only such second-order beliefs affect behavior.

The above constitutes an important criticism of the socialized actor theory. According to Parsons, once a norm is internalized, members of society are motivated to conform by an internal sanctioning system; therefore, one should observe a high correlation among all orders of normative beliefs and behavior. However, experimental evidence does not support such a view (see also: Fishbein 1967; Cialdini et al. 1991). Another indication that the socialized actor theory lacks generality is the observation that norms can change rather quickly, and that new norms often emerge in a short period of time among complete strangers (Mackie 1996). Long-term or close interactions do not seem to be necessary for someone to acquire a given normative disposition, as is testified by the relative ease with which individuals learn new norms when they change status or group (e.g., from single to married, from student to faculty, etc.). Moreover, studies of emergent social and political groups have shown that new norms may form rather rapidly, and that the demise of old patterns of behavior is often abrupt (Robinson 1932; Klassen et al. 1989; Prentice & Miller 1993; Matza 1964). Given the aforementioned limitations, Parsons’ theory might perhaps be taken as an explanation of a particular conception of moral norms (in the sense of internalized, unconditional imperatives), but it cannot be viewed as a general theory of social norms.

It has been argued that behavior is often closely embedded in a network of personal relations, and that a theory of norms should not leave the specific social context out of consideration (Granovetter 1985). Critics of the socialized actor theory have called for an alternative conception of norms that may account for the often weak relation between beliefs and behavior (Deutscher 1973). This alternative approach takes social relations to be crucial in explaining social action, and considers social identity as a key motivating factor. (A strong support for this view among anthropologists is to be found in the work of Cancian 1975.)

Since the notion of social identity is inextricably linked to that of group behavior, it is important to clarify the relation between these concepts. By “social identity” we refer, in Tajfel’s own words, to

that part of an individual’s self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership of a social group (or groups) together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership. (Tajfel 1981: 255)

Note that a crucial feature of social identity is that one’s identification with the group is in some sense a conscious choice: one may accidentally belong to a group, but we can meaningfully talk of social identification only when being a group-member becomes (at least in part) constitutive of who one is. According to Tajfel’s theory, when we categorize ourselves as belonging to a particular group, the perception and definition of the self—as well as our motives—change. That is, we start perceiving ourselves and our fellow group-members along impersonal, “typical” dimensions that characterize the group to which we belong. Such dimensions include specific roles and the beliefs (or actions) that accompany them.

Turner et al.’s (1987) “self-categorization theory” provides a more specific characterization of self-perception, or self-definition, as a system of cognitive self-schemata that filter and process information. Such schemata result in a representation of the social situation that guides the choice of appropriate action. This system has at least two major components, i.e., social and personal identity. Social identity refers to self-descriptions related to group memberships. Personal identity refers to self-descriptions such as individual character traits, abilities, and tastes. Although personal and social identities are mutually exclusive levels of self-definition, this distinction must be taken as an approximation (in that there are many interconnections between social and personal identities). It is, however, important to recognize that we often perceive ourselves primarily in terms of our relevant group memberships rather than as differentiated, unique individuals. So—depending on the situation—personal or group identity will become salient (Brewer 1991).

For example, when one makes interpersonal comparisons between oneself and other group-members, personal identity will become salient; instead, group identity will become salient in situations in which one’s group is compared to another group. Within a group, all those factors that lead members to categorize themselves as different (or endowed with special characteristics and traits) will enhance personal identity. If a group has to solve a common task, but each member is to be rewarded according to her contribution, personal abilities are highlighted and individuals will perceive themselves as unique and different from the rest of the group. Conversely, if all group-members are to equally share the reward for a jointly performed task, group identification will be enhanced. When the difference between self and fellow group-members is accentuated, we are likely to observe selfish motives and self-favoritism against other group-members. When instead group identification is enhanced, in-group favoritism against out-group members will be activated, as well as behavior contrary to self-interest.

According to Turner, social identity is basically a cognitive mechanism whose adaptive function is to make “group behavior” possible. Whenever social identification becomes salient, a cognitive mechanism of categorization is activated in such a way to produce perceptual and behavioral changes. Such categorization is called a stereotype, the prototypical description of what members of a given category are (or are believed to be). It is a cluster of physical, mental and psychological characteristics attributed to a “typical” member of a given group. Stereotyping, like any other categorization process, activates scripts or schemata, and what we call group behavior is nothing but scripted behavior. For example, the category “Asian student” is associated with a cluster of behaviors, personality traits, and values: we often think of Asian students as respectful, diligent, disciplined, and especially good with technical subjects. When thinking of an Asian student solely in terms of group membership, we attribute her the stereotypical characteristics associated with her group, so she becomes interchangeable with other group-members. When we perceive people in terms of stereotypes, we depersonalize them and see them as “typical” members of their group. The same process is at work when we perceive ourselves as group-members: self-stereotyping is a cognitive shift from “perceiving oneself as unique” to “perceiving oneself in terms of the attributes that characterize the group”. It is this cognitive shift that mediates group behavior.

Group behavior (as opposed to individual behavior) is characterized by features such as a perceived similarity between group-members, cohesiveness, a tendency to cooperate to achieve common goals, shared attitudes or beliefs, and conformity to group norms. Once an individual self-categorizes as member of a group, she will perceive herself as “depersonalized” and similar to other group-members in the relevant stereotypical dimensions. Insofar as group-members perceive their interests and goals as identical—because such interests and goals are stereotypical attributes of the group—self-stereotyping will induce a group-member to embrace such interests and goals as her own. It is thus predicted that pro-social behavior will be enhanced by group membership, and diluted when people act in an individualistic mode (Brewer 1979).

The groups with which we happen to identify ourselves may be very large (as in the case in which one self-defines as Muslim or French), or as small as a friends’ group. Some general group identities may not involve specific norms, but there are many cases in which group identification and social norms are inextricably connected. In that case group-members believe that certain patterns of behavior are unique to them, and use their distinctive norms to define group membership. Many close-knit groups (such as the Amish or the Hasidic Jews) enforce norms of separation proscribing marriage with outsiders, as well as specific dress codes and a host of other prescriptive and proscriptive norms. There, once an individual perceives herself as a group-member, she will adhere to the group prototype and behave in accordance with it. Hogg and Turner (1987) have called the process through which individuals come to conform to group norms “referent informational influence”.

Group-specific norms have (among other things) the twofold function of minimizing perceived differences among group-members and maximizing differences between the group and outsiders. Once formed, such norms become stable cognitive representations of appropriate behavior as a group-member. Social identity is built around group characteristics and behavioral standards, and hence any perceived lack of conformity to group norms is seen as a threat to the legitimacy of the group. Self-categorization accentuates the similarities between one’s behavior and that prescribed by the group norm, thus causing conformity as well as the disposition to control and punish transgressors. In the social identity framework, group norms are obeyed because one identifies with the group, and conformity is mediated by self-categorization as an in-group member. A telling historical example of the relationship between norms and group membership was the division of England into the two parties of the Roundheads and Cavaliers. Charles Mackay reports that

in those days every species of vice and iniquity was thought by the Puritans to lurk in the long curly tresses of the monarchists, while the latter imagined that their opponents were as destitute of wit, of wisdom, and of virtue, as they were of hair. A man’s locks were a symbol of his creed, both in politics and religion. The more abundant the hair, the more scant the faith; and the balder the head, the more sincere the piety. (Mackay 1841: 351)

It should be noted that in this framework social norms are defined by collective—as opposed to personal—beliefs about appropriate behaviors (Homans 1950, 1961). To a certain extent, this characterization of social norms is closer to recent accounts than it is to Parsons’ socialized actor theory. On the other hand, a distinct feature of the social identity framework is that people’s motivation to conform comes from their desire to validate their identity as group-members. In short, there are several empirical predictions one can draw from such a framework. Given the theory’s emphasis on identity as a motivating factor, conformity to a norm is not assumed to depend on an individual’s internalization of that norm; in fact, a change in social status or group membership will bring about a change in the norms relevant to the new status/group. Thus a new norm can be quickly adopted without much interaction, and beliefs about identity validation may change very rapidly under the pressure of external circumstances. In this case, not just norm compliance, but norms themselves are potentially unstable.

The experimental literature on social dilemmas has utilized the “priming of group identity” as a mechanism for promoting cooperative behavior (Dawes 1980; Brewer & Schneider 1990). The typical hypothesis is that a pre-play, face-to-face communication stage may induce identification with the group, and thus promote cooperative behavior among group-members. In effect, rates of cooperation have been shown to be generally higher in social dilemma experiments preceded by a pre-play communication stage (Dawes 1991). However, it has been argued that face-to-face communication may actually help group-members gather relevant information about one another: such information may therefore induce subjects to trust each other’s promises and act cooperatively, regardless of any group identification. In this respect, it has been shown that communication per se does not foster cooperation, unless subjects are allowed to talk about relevant topics (Bicchieri & Lev-On 2007). This provides support for the view that communication does not enhance cohesion but rather focuses subjects on relevant rules of behavior, which do not necessarily depend on group identification.

Cooperative outcomes can thus be explained without resorting to the concept of social identity. A social identity explanation appears to be more appropriate in the context of a relatively stable environment, where individuals have had time to make emotional investments (or at least can expect repeated future interactions within the same group). In artificial lab settings, where there are no expectations of future interactions, the concept of social identity seems less persuasive as an explanation of the observed rates of cooperation. On the other hand, we note that social identity does appear to play a role in experimental settings in which participants are divided into separate groups. (In that case, it has been shown that participants categorize the situation as “we versus them”, activating in-group loyalty and trust, and an equal degree of mistrust toward the out-group; Kramer & Brewer 1984; Bornstein & Ben-Yossef 1994.)

Even with stable environments and repeated interactions, however, a theory of norm compliance in terms of social identity cannot avoid the difficulty of making predictions when one is simultaneously committed to different identities. We may concurrently be workers, parents, spouses, friends, club members, and party affiliates, to name but a few of the possible identities we embrace. For each of them there are rules that define what is appropriate, acceptable, or good behavior. In the social identity framework, however, it is not clear what happens when one is committed to different identities that may involve conflicting behaviors.

Finally, there is ample evidence that people’s perceptions may change very rapidly. Since in this framework norms are defined as shared perceptions about group beliefs, one would expect that—whenever all members of a group happen to believe that others have changed their beliefs about core membership rules—the very norms that define membership will change. The study of fashion, fads and speculative bubbles clearly shows that there are some domains in which rapid (and possibly disruptive) changes of collective expectations may occur; it is, however, much less clear what sort of norms are more likely to be subject to rapid changes (think of dress codes rather than codes of honor). The social identity view does not offer a theoretical framework for differentiating these cases: although some norms are indeed related to group membership, and thus compliance may be explained through identity-validation mechanisms, there appear to be limits to the social identity explanation.

Early rational choice models of conformity maintained that, since norms are upheld by sanctions, compliance is merely a payoff-maximizing strategy (Rommetveit 1955; Thibaut & Kelley 1959): when others’ approval and disapproval act as external sanctions, we have a “cost-benefit model” of compliance (Axelrod 1986; James Coleman 1990). Rule-complying strategies are rationally chosen in order to avoid negative sanctions or to attract positive sanctions. This class of rational choice models defines norms behaviorally, equating them with patterns of behavior (while disregarding expectations or values). Such approach relies heavily on sanctions as a motivating factor. According to Axelrod (1986), for example, if we observe individuals to follow a regular pattern of behavior and to be punished if they act otherwise, then we have a norm. Similarly, Coleman (1990) argues that a norm coincides with a set of sanctions that act to direct a given behavior.

However, it has been shown that not all social norms involve sanctions (Diamond 1935; Hoebel 1954). Moreover, sanctioning works generally well in small groups and in the context of repeated interactions, where the identity of participants is known and monitoring is relatively easy. Still, even in such cases there may be a so-called second-order public goods problem. That is, imposing negative sanctions on transgressors is in everybody’s interest, but the individual who observes a transgression faces a dilemma: she is to decide whether or not to punish the transgressor, where punishing typically involves costs; besides, there is no guarantee that other individuals will also impose a penalty on transgressors when faced with the same dilemma. An answer to this problem has been to assume that there exist “meta-norms” that tell people to punish transgressors of lower-level norms (Axelrod 1986). This solution, however, only shifts the problem one level up: upholding the meta-norm itself requires the existence of a higher-level sanctioning system.

Another problem with sanctions is the following: a sanction, to be effective, must be recognized as such. Coleman and Axelrod typically take the repeated prisoner’s dilemma game as an example of the working of sanctions. However, in a repeated prisoner’s dilemma the same action (“C” or “D”) must serve as both the sanctioning action and the target action. By simply looking at behavior, it is unclear whether the action is a function of a sanction or a sanction itself. It thus becomes difficult to determine the presence of a norm, or to assess its effect on choice as distinct from the individual strategies of players.

A further consideration weakens the credibility of the view that norms are upheld only because of external sanctions. Often we keep conforming to a norm even in situations of complete anonymity, where the probability of being caught transgressing is almost zero. In this case fear of sanctions cannot be a motivating force. As a consequence, it is often argued that cases of “spontaneous” compliance are the result of internalization (Scott 1971): people who have developed an internal sanctioning system feel guilt and shame at behaving in a deviant way. Yet, we have seen that the Parsonian view of internalization and socialization is inadequate, as it leads to predictions about compliance that often run counter to empirical evidence.

In particular, James Coleman (1990) has argued in favor of reducing internalization to rational choice, insofar as it is in the interest of a group to get another group to internalize certain norms. In this case internalization would still be the result of some form of socialization. This theory faces some of the same objections raised against Parsons’ theory: norms that are passed on from parents to children, for example, should be extremely resistant to change; hence, one should expect a high degree of correlation between such norms and behavior, especially in those cases where norms prescribe specific kinds of actions. However, studies of normative beliefs about honesty—which one typically acquires during childhood—show that such beliefs are often uncorrelated with behavior (Freeman & Ataöv 1960).

Bicchieri (1990, 1997) has presented a third, alternative view about internalization. This view of internalization is cognitive, and is grounded on the assumption that social norms develop in small, close-knit groups where ongoing interactions are the rule. Once an individual has learned to behave in a way consistent with the group’s interests, she will tend to persist in the learned behavior unless it becomes clear that—on average—the cost of upholding the norm significantly outweighs the benefits. Small groups can typically monitor their members’ behavior and successfully employ retaliation whenever free-riding is observed. In such groups an individual will learn, maybe at some personal cost, to cooperate; she will then uphold the cooperative norm as a “default rule” in any new encounter, unless it becomes evident that the cost of conformity has become excessive. The idea that norms may be “sluggish” is in line with well-known results from cognitive psychology showing that, once a norm has emerged in a group, it will tend to guide the behavior of its members even when they face a new situation (or are isolated from the original group; Sherif 1936).

Empirical evidence shows that norm-abiding behavior is not, as the early rational choice models would have it, a matter of cost/benefit calculation. Upholding a norm that has led one to fare reasonably well in the past is a way of economizing on the effort one would have to exert to devise a strategy when facing a new situation . This kind of “bounded rationality” approach explains why people tend to obey norms that sometimes put them at a disadvantage, as is the case with norms of honesty. This does not mean, however, that external sanctions never play a role in compliance: for example, in the initial development of a norm sanctions may indeed play an important role. Yet, once a norm is established, there are several mechanisms that may account for conformity.

Finally, the view that one conforms only because of the threat of negative sanctions does not distinguish norm-abiding behavior from an obsession or an entrenched habit; nor does that view distinguish social norms from hypothetical imperatives enforced by sanctions (such as the rule that prohibits naked sunbathing on public beaches). In these cases avoidance of the sanctions associated with transgressions constitutes a decisive reason to conform, independently of what others do. In fact, in the traditional rational choice perspective, the only expectations that matter are those about the sanctions that follow compliance or non-compliance. In those frameworks, beliefs about how other people will act—as opposed to what they expect us to do—are not a relevant explanatory variable: however, this leads to predictions about norm compliance that often run counter to empirical evidence.

The traditional rational choice model of compliance depicts the individual as facing a decision problem in isolation: if there are sanctions for non-compliance, the individual will calculate the benefit of transgression against the cost of norm compliance, and eventually choose so as to maximize her expected utility. Individuals, however, seldom choose in isolation: they know the outcome of their choice will depend on the actions and beliefs of other individuals. Game theory provides a formal framework for modeling strategic interactions.

Thomas Schelling (1960), David Lewis (1969), Edna Ullmann-Margalit (1977), Robert Sugden (1986) and, more recently, Peyton Young (1993), Cristina Bicchieri (1993), and Peter Vanderschraaf (1995) have proposed a game-theoretic account according to which a norm is broadly defined as an equilibrium of a strategic interaction. In particular, a Nash equilibrium is a combination of strategies (one for each individual), such that each individual’s strategy is a best reply to the others’ strategies. Since it is an equilibrium, a norm is supported by self-fulfilling expectations in the sense that players’ beliefs are consistent, and thus the actions that follow from players’ beliefs will validate those very beliefs. Characterizing social norms as equilibria has the advantage of emphasizing the role that expectations play in upholding norms. On the other hand, this interpretation of social norms does not prima facie explain why people prefer to conform if they expect others to conform.

Take for example conventions such as putting the fork to the left of the plate, adopting a dress code, or using a particular sign language. In all these cases, my choice to follow a certain rule is conditional upon expecting most other people to follow it. Once my expectation is met, I have every reason to adopt the rule in question. In fact, if I do not use the sign language everybody else uses, I will not be able to communicate. It is in my immediate interest to follow the convention, since my main goal is to coordinate with other people. In the case of conventions, there is a continuity between the individual’s self-interest and the interests of the community that supports the convention. This is the reason why David Lewis models conventions as equilibria of coordination games . Such games have multiple equilibria, but once one of them has been established, players will have every incentive to keep playing it (as any deviation will be costly).

Take instead a norm of cooperation. In this case, the expectation that almost everyone abides by it may not be sufficient to induce compliance. If everyone is expected to cooperate one may be tempted, if unmonitored, to behave in the opposite way. The point is that conforming to social norms , as opposed to conventions, is almost never in the immediate interest of the individual. Often there is a discontinuity between the individual’s self-interest and the interests of the community that supports the social norm.

The typical game in which following a norm would provide a better solution (than the one attained by self-centered agents) is a mixed-motive game such as the prisoner’s dilemma or the trust game. In such games the unique Nash equilibrium represents a suboptimal outcome. It should be stressed that—whereas a convention is one among several equilibria of a coordination game—a social norm can never be an equilibrium of a mixed-motive game. However, Bicchieri (2006) has argued that when a norm exists it transforms the original mixed-motive game into a coordination one. As an example, consider the following prisoner’s dilemma game ( Figure 1 ), where the payoffs are B=Best, S=Second, T=Third, and W=Worst. Clearly the only Nash equilibrium is to defect (D), in which case both players get (T,T), a suboptimal outcome. Suppose, however, that society has developed a norm of cooperation; that is, whenever a social dilemma occurs, it is commonly understood that the parties should privilege a cooperative attitude. Should, however, does not imply “will”, therefore the new game generated by the existence of the cooperative norm has two equilibria: either both players defect or both cooperate.

Note that, in the new coordination game (which was created by the existence of the cooperative norm), the payoffs are quite different from those of the original prisoner’s dilemma. Thus there are two equilibria: if both players follow the cooperative norm they will play an optimal equilibrium and get (B,B), whereas if they both choose to defect they will get the suboptimal outcome (S,S). Players’ payoffs in the new coordination game differ from the original payoffs because their preferences and beliefs will reflect the existence of the norm. More specifically, if a player knows that a cooperative norm exists and has the right kind of expectations, then she will have a preference to conform to the norm in a situation in which she can choose to cooperate or to defect. In the new game generated by the norm’s existence, choosing to defect when others cooperate is not a good choice anymore (T,W). To understand why, let us look more closely to the preferences and expectations that underlie the conditional choice to conform to a social norm.

Bicchieri (2006) defines the expectations that underlie norm compliance, as follows:

Note that universal compliance is not usually needed for a norm to exist. However, how much deviance is socially tolerable will depend on the norm in question. Group norms and well-entrenched social norms will typically be followed by almost all members of a group or population, whereas greater deviance is usually accepted when norms are new or they are not deemed to be socially important. Furthermore, as it is usually unclear how many people follow a norm, different individuals may have different beliefs about the size of the group of followers, and may also have different thresholds for what “sufficiently large” means. What matters to conformity is that an individual believes that her threshold has been reached or surpassed. For a critical assessment of the above definition of norm-driven preferences, see Hausman (2008).

Brennan et al. (2013) also argue that norms of all kinds share in an essential structure. Norms are clusters of normative attitudes in a group, combined with the knowledge that such a cluster of attitudes exists. On their account, “A normative principle P is a norm within a group G if and only if:

- A significant proportion of the members of G have P -corresponding normative attitudes; and

- A significant proportion of the members of G know that a significant proportion of the members of G have P -corresponding attitudes” (Brennan et al. 2013: 29)

On this account, a “ P -corresponding normative attitude” is understood to be a judgment, emotional state, expectation, or other properly first personal normative belief that supports the principle P (e.g., Alice thinking most people should P would count as a normative attitude). Condition (i) is meant to reflect genuine first personal normative commitments, attitudes or beliefs. Condition (ii) is meant to capture those cases where individuals know that a large part of their group also shares in those attitudes. Putting conditions (i) and (ii) together offers a picture that the authors argue allows for explanatory work to be done on a social-level normative concept while remaining grounded in individual-level attitudes.

Consider again the new coordination game of Figure 1 : for players to obey the norm, and thus choose C, it must be the case that each expects the other to follow it. In the original prisoner’s dilemma, empirical beliefs would not be sufficient to induce cooperative behavior. When a norm exists, however, players also believe that others believe they should obey the norm, and may even punish them if they do not. The combined force of empirical and normative expectations makes norm conformity a compelling choice, be it because punishment may follow or just because one recognizes the legitimacy of others’ expectations (Sugden 2000).

It is important to understand that conformity to a social norm is always conditional on the expectations of what the relevant other/s will do. We prefer to comply with the norm as we have certain expectations. To make this point clear, think of the player who is facing a typical one-shot prisoner’s dilemma with an unknown opponent. Suppose the player knows a norm of cooperation exists and is generally followed, but she is uncertain as to whether the opponent is a norm-follower. In this case the player is facing the following situation ( Figure 2 ).

With probability p , the opponent is a norm-following type, and with probability \(1 - p\) she is not. According to Bicchieri, conditional preferences imply that having a reason to be fair, reciprocate or cooperate in a given situation does not entail having any general motive or disposition to be fair, reciprocate or cooperate as such. Having conditional preferences means that one may follow a norm in the presence of the relevant expectations, but disregard it in its absence. Whether a norm is followed at a given time depends on the actual proportion of followers, on the expectations of conditional followers about such proportion, and on the combination of individual thresholds.

As an example, consider a community that abides by strict norms of honesty. A person who, upon entering the community, systematically violates these norms will certainly be met with hostility, if not utterly excluded from the group. But suppose that a large group of thieves makes its way into this community. In due time, people would cease to expect honesty on the part of others, and would find no reason to be honest themselves in a world overtaken by crime. In this case, probably norms of honesty would cease to exist, as the strength of a norm lies in its being followed by many of the members of the relevant group (which in turn reinforces people’s expectations of conformity).

What we have discussed is a “rational reconstruction” of what a social norm is. Such a reconstruction is meant to capture some essential features of norm-driven behavior; also, this analysis helps us distinguish social norms from other constructs such as conventions or personal norms. A limit of this account, however, is that it does not indicate how such equilibria are attained or, in other terms, how expectations become self-fulfilling.

While neoclassical economics and game theory traditionally conceived of institutions as exogenous constraints, research in political economy has generated new insights into the study of endogenous institutions . Specifically, endogenous norms have been shown to restrict the individual’s action set and drive preferences over action profiles (Bowles 1998; Ostrom 2000). As a result, the “standard” economic framework positing exogenous (and in particular self-centered) preferences has come under scrutiny. Widely documented deviations from the predictions of models with self-centered agents have informed alternative accounts of individual choice (for one of the first models of “interdependent preferences”, see Stigler & Becker 1977).

Some alternative accounts have helped reconcile insights about norm-driven behavior with instrumental rationality (Elster 1989b). Moreover, they have contributed to informing the design of laboratory experiments on non-standard preferences (for a survey of early experiments, see Ledyard 1995; more recent experiments are reviewed by Fehr & Schmidt 2006 and Kagel & Roth 2016). In turn, experimental findings have inspired the formulation of a wide range of models aiming to rationalize the behavior observed in the lab (Camerer 2003; Dhami 2016).

It has been argued that the upholding of social norms could simply be modeled as the optimization of a utility function that includes the others’ welfare as an argument. For instance, consider some of the early “social preference” theories, such as Bolton and Ockenfels’ (2000) or Fehr and Schmidt’s (1999) models of inequity aversion. These frameworks can explain a good wealth of evidence on preferences for equitable income distributions; they cannot however account for conditional preferences like those reflecting principles of reciprocity (e.g., I will keep the common bathroom clean, if I believe my roommates do the same). As noted above, the approach to social norms taken by philosophically-inclined scholars has emphasized the importance of conditional preferences in supporting social norms. In this connection, we note that some of the social preference theories do account for motivations conditional on empirical beliefs, whereby a player upholds a principle of “fair” behavior if she believes her co-players will uphold it too (Rabin 1993; Dufwenberg & Kirchsteiger 2004; Falk & Fischbacher 2006; Charness & Rabin 2002). These theories presuppose that players are hardwired with a notion of fair or kind behavior, as exogenously defined by the theorist. Since they implicitly assume that all players have internalized a unique—exogenous—normative standpoint (as reflected in some notion of fairness or kindness), these theories do not explicitly model normative expectations. Hence, players’ preferences are assumed to be conditional solely on their empirical beliefs; that is, preferences are conditional on whether others will behave fairly (according to an exogenous principle) or not.

That said, we stress that social preferences should not be conflated with social norms. Social preferences capture stable dispositions toward an exogenously defined principle of conduct (Binmore 2010). By contrast, social norms are better studied as group-specific solutions to strategic problems (Sugden 1986; Bicchieri 1993; Young 1998b). Such solutions are brought about by a particular class of preferences (“norm-driven preferences”), conditional on the relevant set of empirical beliefs and normative expectations. In fact, we stress that “what constitutes fair or appropriate behavior” often varies with cultural or situational factors (Henrich et al. 2001; Cappelen et al. 2007; Ellingsen et al. 2012). Accounting for endogenous expectations is therefore key to a full understanding of social norms.

Relatedly, Guala (2016) offers a game-theoretic account of institutions, arguing that institutions are sets of rules in equilibrium. Guala’s view incorporates insights from two competing accounts of institutions: institutions-as-rules (perhaps best rendered by North 1990), and institutions-as-equilibria. From the first account, he captures the idea that institutions create rules that help to guide our behaviors and reduce uncertainty. With rules in place, we more or less know what to do, even in new situations. From the second, he captures the idea that institutions are solutions to coordination problems that arise from our normal interactions. The institutions give us reasons to follow them. The function of the rules, then, is to point to actions that promote coordination and cooperation. Because of the equilibrium nature of the rules, each individual has an incentive to choose those actions, provided others do too. Guala relies on a correlated equilibrium concept to unite the rules and equilibria accounts. On this picture, an institution is simply a correlated equilibrium in a game, where other correlated equilibria would have been possible.

Thrasher (2018) offers a comparative-functional analysis of norms that broadly aligns with the Bicchieri (2006) framework to help understand the durability of “bad norms.” Abbink et al. (2017) use public goods-like experiments to show how peer punishment can hold inefficient norms in place. This general framework can be helpful to understand why duels and honor killings can become stable (e.g. Thrasher and Handfield 2018, Handfield and Thrasher 2019). This work explores the signaling function of socially costly norms.

An alternative class of models explains norm compliance in terms of social image or self-image concerns (e.g., Andreoni and Bernheim 2009; Bénabou and Tirole 2006, 2011). These models assume that one tries to signal (to others or to one’s future self) that one has good “personal traits”, with such type-specific traits being imperfectly observed. More precisely, Bénabou and Tirole (2006) model the individual’s utility from contributing to a public good as a function of (i) material payoffs, (ii) intrinsic rewards from behaving altruistically, and (iii) reputational returns; in particular, the authors assume that reputational returns depend on the observers’ posterior expectations of the individual’s type. Bénabou and Tirole then consider (a refinement of) signaling equilibria, thereby allowing for multiple solutions to occur as a result of the interplay of individual motivations and of the level of observability of the actions. While models with reputational concerns do not explicitly define normative expectations, they generally posit that players care about their reputation under the assumption that acting altruistically is good or appropriate. Looking ahead, there is still work to do to fully formalize the interplay of (endogenous) normative expectations and empirical beliefs within a general model that is applicable to any game setting. Such a model should probably build on the “psychological game theory” framework (for discussion, see Battigalli and Dufwenberg 2022, p. 857; see also Bicchieri and Sontuoso 2015).

In what follows we focus on lab experiments that identify social norms by explicitly measuring both empirical and normative expectations.

Xiao and Bicchieri (2010) designed an experiment to investigate the impact on trust games of two potentially applicable—but conflicting—principles of conduct, namely, equality and reciprocity . Note that the former can be broadly defined as a rule that recommends minimizing payoff differences, whereas the latter recommends taking a similar action as others (regardless of payoff considerations). The experimental design involved two trust game variants: in the first one, players started with equal endowments; in the second one, the investor was endowed with twice the money that the trustee was given. In both cases, the investor could choose to transfer a preset amount of money to the trustee or keep it all. Upon receiving the money, the trustee could in turn keep it or else transfer back some of it to the investor: in the equal endowment condition (“baseline treatment”), both equality and reciprocity dictate that the trustee transfer some money back to the investor; by contrast, in the unequal endowment condition (“asymmetry treatment”), equality and reciprocity dictate different actions as the trustee could guarantee payoff equality only by making a zero back-transfer. Xiao and Bicchieri elicited subjects’ first- and second-order empirical beliefs (“how much do you think other participants in your role will transfer to their counterpart?”; “what does your counterpart think you will do?”) and normative expectations (“how much do you think your counterpart believes you should transfer to her?”). The experimental results show that a majority of trustees returned a positive amount whenever reciprocity would reduce payoff inequality (in the baseline treatment); by contrast, a majority of trustees did not reciprocate the investors’ transfer when doing so would increase payoff inequality (in the asymmetry treatment). Moreover, investors correctly believed that less money would be returned in the asymmetry treatment than in the baseline treatment, and most trustees correctly estimated investors’ beliefs in both treatments. However, in the asymmetry treatment empirical beliefs and normative expectations conflicted: this highlights that, when there is ambiguity as to which principle of conduct is in place, each subject will support the rule of behavior that favors her most.

Reuben and Riedl (2013) examine the enforcement of norms of contribution to public goods in homogeneous and heterogeneous groups, such as groups whose members vary in their endowment, contribution capacity, or marginal benefits. In particular, Reuben and Riedl are interested in the normative appeal of two potentially applicable rules: the efficiency rule (prescribing maximal contributions by all) and the class of relative contribution rules (prescribing a contribution that is “fair” relative to the contributions of others; e.g., equality and equity rules). Reuben and Riedl’s results show that, in the absence of punishment, no positive contribution norm emerged and all groups converged toward free-riding. By contrast, with punishment, contributions were consistent with the prescriptions of the efficiency rule in a significant subset of groups (irrespective of the type of group heterogeneity); in other groups, contributions were consistent with relative contribution rules. These results suggest that even in heterogeneous groups individuals can successfully enforce a contribution norm. Most notably, survey data involving third parties confirmed well-defined yet conflicting normative views about the aforementioned contribution rules; in other words, both efficiency and relative contribution rules are normatively appealing, and are indeed potential candidates for emerging contribution norms in different groups.

Bicchieri and Chavez (2010) designed an experiment to investigate norm compliance in ultimatum games. Specifically, their experiment involved a variant of the ultimatum game whereby the proposer could choose one of the following three options: ($5, $5) , ($8, $2) , or Coin (in which case one of the other two allocations would be selected at random). This design allows for two plausible notions of fairness: as an equal outcome ($5, $5) or as a fair procedure (Coin). The experimenters elicited subjects’ normative expectations about the actions they thought would be considered fair by most participants: proposers and responders showed a remarkable degree of agreement in their notions of fairness, as most subjects believed that a majority of participants deemed both ($5, $5) and Coin to be appropriate. Further, the experimenters had subjects play three instances of the above ultimatum game under different information conditions. In the “full information” condition, all participants knew that the Coin option was available, and that responders would know if their respective proposer had chosen Coin. In the “private information” condition, responders did not know that Coin was available to proposers, and proposers were aware of responders’ ignorance. In the “limited information” condition, participants knew that the Coin option was available, but responders would not be able to distinguish whether their respective proposer had implemented one of the two allocations directly or had chosen Coin instead. The experimental results show that when normative expectations supporting the Coin option were either absent (in the private condition) or could be defied without consequence (in the limited condition), the frequency of choice of ($5, $5) and ($8, $2), respectively, were considerably higher than those of Coin. Moreover, the frequency of Coin choices was highest in the public information condition, where such option was common knowledge and its outcome transparent: this shows that there proposers followed the rule of behavior that favored them most, and that such a rule was effectively a social norm. On the other hand, substantial norm evasion characterized proposers’ behavior in the limited information condition, where ($8, $2) was the most frequent choice.

In a subsequent study, Chavez and Bicchieri (2013) measured empirical and normative expectations (as well as behavior) of third parties who were given the opportunity to add to or deduct from the payoffs of subjects who had participated in an ultimatum game. Third parties tended to reward subjects involved in equal allocations and to compensate victims of unfair allocations (rather than punish unfair behavior); on the other hand, third parties were willing to punish when compensation was not an available option. The experimental results further show that third parties shared a notion of fairness (as indicated by their normative expectations), and that such notion was sensitive to contextual differences.

Krupka and Weber (2013) introduced an interesting procedure for identifying social norms by means of pre-play coordination games. In brief, using alternative (between-subjects) variants of the dictator game, Krupka and Weber had participants assess the extent to which different actions were collectively perceived as socially appropriate: subjects providing these ratings effectively faced a coordination game, as they were incentivized to match the modal response given by others in the same situation (such a pre-play coordination game was intended to verify the presence of shared normative expectations). Krupka and Weber went on to use these elicited assessments to predict other subjects’ compliance with the relevant social norm in each dictator game variant (for another application of the same elicitation procedure, see Gächter et al. 2013).

Similarly, Schram and Charness’ (2015) proposed a procedure for inducing a shared understanding of the relevant rule of behavior, in the lab. In short, Schram and Charness had participants in dictator games receive advice from a group of third parties. The information received simply revealed what a group of uninvolved subjects thought dictators ought to do : as such, the information received generated an exogenous variation in the dictators’ normative expectations. Schram and Charness’ results show that choices are indeed affected by this information.

Bicchieri and Xiao (2009) designed an experiment to investigate what happens when empirical and normative expectations conflict. To that end, participants in a dictator game were exposed to different pieces of information. Specifically, two groups of dictators were given some “descriptive information”; that is, they were told what other subjects had done in another session (i.e., one group was told that previous participants had made for the most part a generous offer, while the other group was told that most participants had made a selfish offer). Further, another two groups of dictators were given some “normative information”; that is, they were told what previous subjects said ought to be done (i.e., one group was told that most previous participants thought that one should make a generous offer, while the other group was told that most participants thought that one should make a selfish offer). Other groups were given both descriptive and normative information. The experimental results show that—whenever such information did not conflict—both descriptive and normative messages had a significant influence on dictators’ own expectations and subsequent choices. When messages conflicted in that one indicated generosity and the other indicated selfishness, only the descriptive information affected dictators’ behavior. This suggests that if people recognize that others are breaching the norm, then they will no longer feel compelled to follow the relevant rule of behavior themselves.

To conclude, the studies surveyed here provide evidence of the role played by expectations in affecting behavior in a variety of social dilemmas. In this regard, we note that in contrast to the vast literature on empirical beliefs, the number of lab studies that directly measure normative expectations is relatively limited: more research is clearly needed to investigate the interplay of empirical and normative information about applicable rules of behavior.

Thus far we have examined accounts of social norms that take for granted that a particular norm exists in a population. However, for a full account of social norms, we must answer two questions related to the dynamics of norms. First, we must ask how a norm can emerge. Norms require a set of corresponding beliefs and expectations to support them, and so there must be an account of how these arise. Second, we must investigate the conditions under which a norm is stable under some competitive pressure from other norms. Sometimes, multiple candidate norms vie for dominance in a population. Even if one norm has come to dominate the population, new norms can try to “invade” the existing norm’s population of adherents.

Let us now turn to the question of norm emergence. Here we can see three classes of models: first, a purely biological approach, second, a more cognitive approach, and third, a structured interactions approach. The most famous of the biological approaches to norms seek to explain cooperative behavior. The simplest models are kin selection models (Hamilton 1964). These models seek to explain altruistic tendencies in animals by claiming that, as selection acts on genes, those genes have an incentive to promote the reproductive success of other identical sets of genes found in other animals. This mode of explanation can provide an account of why we see cooperative behaviors within families, but being gene-centered, cannot explain cooperative behavior toward strangers (as strangers should not be sufficiently genetically related to merit altruistic behavior).

Models of “reciprocal altruism” (Trivers 1971, 1985), on the other hand, tell us that cooperative behavior has no chance of evolving in random pairings, but will evolve in a social framework in which individuals can benefit from building reputations for being nice guys. Reciprocal altruism, however, does not require an evolutionary argument; a simple model of learning in ongoing close-knit groups will do, and has the further advantage of explaining why certain types of cooperative behavior are more likely to emerge than others. All that matters in these models is that agents can properly identify other agents, such that they can maintain a record of their past behavior. This allows for the possibility of reputations: people who have the reputation of being cooperative will be treated cooperatively, and those who have a reputation of being unfair will be treated unfairly.