SOCIALSTUDIESHELP.COM

The Revolution

The foundations of the constitution: the american revolution begins, introduction.

Defining the American Revolution within its historical context is crucial to understanding its significance in the course of American history.

The American Revolution was a pivotal event that transformed the thirteen American colonies from subjects of the British Empire into an independent nation. This treatise aims to explore the multifaceted aspects of this revolution, from its causes and progression to its profound impact on American society and its enduring ideological legacy.

The thesis of this treatise is that the American Revolution was not merely a war for independence, but a complex and transformative movement driven by a combination of factors, including British colonial policies, Enlightenment ideas, socioeconomic tensions, and pivotal events that culminated in the Declaration of Independence . Its consequences reshaped the course of history, both domestically and internationally, leaving a lasting legacy of freedom and democracy.

Causes of the American Revolution

British colonial policy.

The American Revolution was shaped significantly by British colonial policies that engendered growing discontent among the colonists. Among these policies, taxation was a focal point of contention. The Stamp Act of 1765, which imposed taxes on various printed materials, and the Townshend Acts of 1767, which levied duties on imported goods, were met with vehement opposition.

In addition to taxation, the Navigation Acts imposed restrictions on colonial trade, compelling colonists to trade primarily with Britain and its territories. These policies not only stifled economic growth but also bred resentment among those who sought more economic autonomy.

Enlightenment Ideas and Philosophical Influences

The Enlightenment, a period marked by intellectual flourishing and the spread of rationalist ideas, played a pivotal role in fomenting revolutionary sentiments. Influential thinkers like John Locke, whose ideas on natural rights and government’s obligation to protect them, and Montesquieu, whose theories on the separation of powers, deeply influenced American colonists.

These Enlightenment ideals not only provided intellectual underpinnings for the American Revolution but also ignited the belief that self-governance and liberty were inalienable rights that the British government was infringing upon.

Socioeconomic Factors

The American colonies were characterized by economic disparities and class tensions. The elites of colonial society were discontented with British economic policies, which they saw as detrimental to their prosperity. At the same time, the colonial economy was intricately tied to trade and commerce, further fueling resentment when British regulations interfered with these economic activities.

The tensions between the colonial elite and the common people, many of whom were struggling economically, contributed to the revolutionary fervor. The quest for greater economic independence and opportunities played a significant role in the growing unrest.

Events Leading to Conflict

While tensions simmered over time, several events served as catalysts for the outbreak of open conflict. The Boston Massacre of 1770, in which British soldiers killed five colonists during a confrontation, intensified anti-British sentiment.

Further escalation occurred with the Boston Tea Party in 1773 when colonists, disguised as Mohawk Indians, boarded British ships and dumped chests of tea into Boston Harbor in protest of the Tea Act. These events marked a turning point, as they demonstrated the readiness of some colonists to use force to resist British authority.

American Revolution: From Rebellion to Independence

Initial responses to british policies.

The initial responses to British policies were marked by protests and resistance. Colonists organized themselves, forming Committees of Correspondence to exchange information and coordinate actions against British authorities. The First Continental Congress convened in 1774, bringing together representatives from twelve of the thirteen colonies to discuss grievances and strategies for collective action.

Outbreak of Armed Conflict

The armed conflict that would become the American Revolution began in earnest with the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775. These skirmishes between colonial militia and British forces marked the first military engagements of the revolution. Paul Revere’s midnight ride and the contributions of figures like Sam Adams played crucial roles in alerting and rallying the colonial forces.

Declaration of Independence

The pivotal moment in the American Revolution arrived with the drafting and adoption of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Crafted primarily by Thomas Jefferson, the Declaration proclaimed the colonies’ intent to sever ties with Britain and outlined the philosophical foundations for their decision. It asserted the self-evident truths of equality and unalienable rights, including life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Military Campaigns and Key Figures

The subsequent years of the revolution were marked by a series of battles and campaigns, with George Washington emerging as a central figure. Key conflicts, such as the Battle of Saratoga and the Siege of Yorktown, significantly influenced the course of the war. The support of international allies, particularly the French, played a crucial role in securing American victory.

Impact of the American Revolution

Domestic changes.

The American Revolution ushered in significant changes within the newly independent nation. The colonies transitioned into states, each drafting its own constitution and establishing governments. The Articles of Confederation served as the first attempt at a national government but proved ineffective, eventually leading to the drafting of the United States Constitution in 1787.

International Consequences

The American Revolution had far-reaching consequences on the international stage. It served as an inspiration for other independence movements, most notably the French Revolution. The successful American bid for independence also reshaped global politics, altering alliances and diplomatic relationships.

Ideological Legacy

The revolution’s ideological legacy left an indelible mark on American society. The principles enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, including the belief in individual rights and limited government, influenced the framing of the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights. The American Revolution set a precedent for democratic governance and the protection of citizens’ rights that continues to shape American political and social life.

Challenges and Controversies

Loyalists and divided loyalties.

While the American Revolution garnered support from many colonists, it also created significant divisions and challenges. Loyalists, those who remained loyal to the British Crown, faced hostility and persecution from patriots. The experiences of Loyalists during and after the revolution shed light on the complex nature of divided loyalties within colonial society.

Native Americans and African Americans

The American Revolution had varying impacts on different groups, including Native Americans and African Americans. Native American tribes faced choices regarding alliances and territorial disputes. Some tribes sided with the British, while others aligned with the American colonists.

The question of slavery also loomed large during the revolution. Despite the rhetoric of liberty and equality, slavery persisted in many parts of the newly formed United States, revealing a stark contrast between the revolutionary ideals and the realities of racial inequality.

Women’s Contributions

Women played significant but often overlooked roles during the American Revolution. Figures like Abigail Adams, who corresponded with her husband John Adams about women’s rights and the need for legal protections, made important contributions to the revolutionary discourse. Women also supported the war effort as nurses, spies, and in various other roles, demonstrating their commitment to the cause of independence.

In conclusion, the American Revolution was a transformative and multifaceted movement that reshaped the course of history. It emerged as a response to a combination of factors, including oppressive British colonial policies, the influence of Enlightenment ideas, socioeconomic tensions, and pivotal events that culminated in the Declaration of Independence.

The consequences of the revolution were profound. Domestically, it led to the formation of a new nation with a unique system of government. The United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights reflected the revolutionary principles of individual rights and limited government, setting a precedent for democratic governance.

Internationally, the American Revolution inspired other independence movements and shifted the geopolitical landscape. It contributed to the emergence of the United States as a global player.

However, the revolution also brought forth challenges and controversies, such as the treatment of Loyalists, the complex relationships with Native Americans, the persistence of slavery, and the struggle for women’s rights.

Ultimately, the American Revolution’s legacy endures. It serves as a testament to the enduring power of ideas and the capacity of a determined people to shape their own destiny. The principles of liberty, equality, and self-determination continue to be central to the American identity and its role on the global stage.

Frequently Asked Questions about the American Revolution?

The American Revolution was driven by a complex interplay of factors. One of the primary causes was British colonial policies that imposed heavy taxation, such as the Stamp Act and the Townshend Acts, and restricted colonial trade through the Navigation Acts. These policies angered the colonists, who believed they were being unfairly taxed without representation in the British Parliament.

Enlightenment ideas also played a significant role. The works of thinkers like John Locke and Montesquieu, which emphasized individual rights and the separation of powers, influenced American colonists and fueled their desire for self-determination.

Socioeconomic factors cannot be overlooked. Economic disparities and tensions between the colonial elite and common people contributed to revolutionary sentiments. Many colonists sought greater economic autonomy and opportunities for growth.

The outbreak of armed conflict, triggered by events like the Boston Massacre and the Boston Tea Party, further escalated tensions, pushing the colonists towards rebellion.

The American Revolution saw the emergence of several key figures who played pivotal roles in shaping its course.

George Washington: George Washington is often regarded as the father of the nation. He served as the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army and played a crucial role in leading the colonists to victory.

Thomas Jefferson: Thomas Jefferson is best known for drafting the Declaration of Independence, which articulated the colonists’ desire for independence and their belief in fundamental human rights.

Benjamin Franklin: Franklin was a polymath who made significant diplomatic contributions to the revolutionary cause. He helped secure French support, which proved vital to the American victory.

John Adams: John Adams was a key advocate for independence and played a critical role in the Continental Congress. He later became the second President of the United States.

Abigail Adams: While not a political leader, Abigail Adams deserves mention for her letters to her husband John Adams. Her correspondence highlighted the importance of women’s rights and their contributions to the revolution.

These figures, among others, shaped the American Revolution and the subsequent founding of the United States.

The American Revolution had profound and lasting impacts on American society. One of the most significant changes was the transition from colonies to states. Each state drafted its own constitution and established its government. However, the initial attempt at a national government under the Articles of Confederation proved ineffective, leading to the adoption of the United States Constitution in 1787.

The revolution also brought about a heightened sense of national identity among Americans, as they now saw themselves as citizens of a single nation rather than subjects of a distant monarchy.

Ideologically, the principles enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, such as individual rights and limited government, influenced the framing of the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights. This set the stage for the development of American democracy and the protection of citizens’ rights.

Economically, the revolution disrupted trade relationships with Britain but opened new possibilities for commerce and expansion within the United States.

While women’s roles in the American Revolution are often overlooked, they made significant contributions to the revolutionary cause. Women were actively involved in various capacities:

Spies: Some women acted as spies, gathering intelligence and passing on crucial information to the Continental Army. One notable spy was Lydia Darragh, who provided valuable information to George Washington.

Nurses and Medics: Women worked as nurses and medics, tending to wounded soldiers on the battlefield and in military hospitals.

Suppliers and Supporters: Women contributed by sewing uniforms, knitting socks, and preparing supplies for the troops. They also ran households and farms in the absence of male family members who were away fighting.

Ideological Contributions: Women like Abigail Adams wrote letters and engaged in intellectual discourse, advocating for women’s rights and highlighting the revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality.

Despite the limitations placed on their roles in society at the time, women played an integral part in supporting the American Revolution, and their contributions paved the way for discussions about gender equality in the years that followed.

Loyalists, those who remained loyal to the British Crown during the American Revolution, faced significant challenges and hardships. They were often subjected to persecution, harassment, and even violence by Patriots who viewed them as traitors. Loyalists had their properties confiscated, and some were forced to flee to British-controlled territories. After the war, many Loyalists faced difficulties reintegrating into American society, and some chose to emigrate to other British colonies, such as Canada.

The American Revolution had varied effects on Native American tribes. Some tribes supported the British, hoping that a British victory would prevent American expansion into their lands. Others, like the Oneida and Tuscarora, allied with the American colonists. The revolution ultimately led to territorial disputes, loss of land, and disruptions to Native American communities. The Treaty of Paris in 1783, which ended the war, did not protect Native American interests, and many tribes faced significant challenges in the post-revolutionary period.

Yes, slavery played a complex role in the American Revolution. While the revolution was motivated by ideals of liberty and equality, slavery continued to exist in many parts of the newly formed United States. Some enslaved individuals sought freedom by joining the British or Continental Army, where they were promised emancipation in exchange for their service. However, the institution of slavery persisted in many states, and the issue of slavery remained a contentious and divisive one in the years following the revolution. The contradiction between the revolutionary ideals of freedom and the reality of slavery would eventually lead to the abolitionist movement and the Civil War.

The American Revolution served as a source of inspiration for other independence movements globally. The successful rebellion against a colonial power demonstrated that it was possible to achieve independence and self-determination. Perhaps the most notable example is the French Revolution, which was heavily influenced by American revolutionary ideals and the Enlightenment. The French Revolution, in turn, inspired independence movements in Latin America, Haiti, and other regions. The American Revolution’s impact on the world stage extended beyond its own borders, contributing to a wave of movements seeking freedom and self-governance in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

International allies played a significant role in the American Revolution. The most notable ally was France, which provided critical military and financial support to the American colonists. The French Navy and troops, under General Rochambeau, played pivotal roles in the Siege of Yorktown, a decisive battle in the American Revolution. Additionally, Spain and the Netherlands offered support at various stages of the conflict. These international alliances helped tip the balance in favor of the American colonists and contributed significantly to their victory.

The American Revolution fundamentally altered the relationship between the United States and Britain. Prior to the revolution, the American colonies were British subjects. However, after gaining independence, the United States became a sovereign nation. The Treaty of Paris in 1783 formally recognized the independence of the United States and established the boundaries of the new nation. While the two countries eventually developed diplomatic relations, the legacy of the revolution left a lasting impact on their relationship, shaping their interactions on political, economic, and cultural fronts for years to come.

The American Revolution had profound and long-term consequences for American democracy. The revolutionary ideals of liberty, equality, and self-determination were enshrined in the Declaration of Independence and later reflected in the United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights. These documents laid the foundation for American democracy, emphasizing individual rights, the rule of law, and limited government. The revolution set a precedent for democratic governance and became a touchstone for discussions on citizenship, civil liberties, and political participation. It continues to influence American political and social life, shaping debates and policies to this day.

The enduring legacy of the American Revolution in contemporary America is vast and multifaceted. It includes the establishment of a democratic republic with a system of checks and balances, a commitment to individual rights and freedoms, and the protection of civil liberties through the Bill of Rights. The revolution’s ideals continue to inspire political discourse, activism, and advocacy for social justice. Additionally, the American Revolution’s impact on international politics is seen in its influence on global movements for independence and self-determination. The revolution remains a source of national pride and identity, celebrated through holidays like Independence Day. Its legacy serves as a reminder of the enduring power of revolutionary ideas and the capacity of a determined people to shape their own destiny.

Chapter 3 Introductory Essay: 1763-1789

Written by: Jonathan Den Hartog, Samford University

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain the context in which America gained independence and developed a sense of national identity

Introduction

The American Revolution remains an important milestone in American history. More than just a political and military event, the movement for independence and the founding of the United States also established the young nation’s political ideals and defined new governing structures to sustain them. These structures continue to shape a country based on political, religious, and economic liberty, and the principle of self-government under law. The “shot heard round the world” (as poet Ralph Waldo Emerson described the battles of Lexington and Concord) created a nation that came to inspire the democratic pursuit of liberty in other lands, bringing a “new order of the ages”.

This engraving of the 1775 battle of Lexington—detailed by American printmaker Amos Doolittle who volunteered to fight against the British—is the only contemporary American visual record of this event.

From Resistance to Revolution

As British subjects, the colonists felt flush with patriotism after the Anglo-American victory in the French and Indian War (1754–1763). They were proud of their king, George III, and of the “rights of Englishmen” that made them part of a free and prosperous world empire. Although Britain’s policies after the French and Indian War caused disputes and tensions between the crown and its North American colonies, independence for the colonies was not a foregone conclusion. Instead, the desire for independence emerged as a result of individual decisions and large-scale events that intensified the conflict with Great Britain and helped unite the diverse colonies.

As early as 1763, British responses to the end of the French and Indian War were arousing anger in the colonies. An immediate question concerned Britain’s relationship with American Indians in the interior. Many French-allied American Indians formed a confederation and continued to fight the British, especially under the leadership of the Odawa chief Pontiac and the Delaware prophet Neolin. Together, they hoped to reclaim lands exclusively for their tribes and to entice the French to return and once again challenge the English. Pontiac’s War led to American Indian seizure of western settlements such as Detroit and Fort Niagara. Rather than ending the dispute quickly, unsuccessful British attempts at diplomacy with France’s Indian allies dragged the war into 1766. (See the Pontiac’s Rebellion Narrative.)

Meanwhile, the British issued the Proclamation of 1763, which attempted to separate American Indian and white settlements by forbidding American colonists to cross the Appalachian Mountains. The hope was to prevent another costly war and crushing war debt. The British stationed troops and built forts on the American frontier to enforce the proclamation, but they were ignoring reality. Many colonists had already settled west of the Appalachians in search of new opportunities, and those who had fought the war specifically to acquire land believed their property rights were being violated by the British standing army.

The line drawn by the Royal Proclamation of 1763 from Lake Ontario to the Gulf of Mexico left much of the frontier “reserved for the Indians” and led to resentment from many colonists.

In 1764, the British began to raise revenue for the large army stationed on the colonial frontier and tightened their enforcement of trade regulations. This was a change from the relatively hands-off approach to governing they had previously embraced. The new ministry of George Grenville introduced the Sugar Act, which reduced the six-pence tax from the widely ignored Molasses Act (1733) by three pence per gallon. But British customs officials were ordered to enforce the Sugar Act by collecting the newly lowered tax and prosecuting smugglers in vice-admiralty courts without juries. Colonial merchants bristled against the changes in imperial policy, but worse changes were yet to come.

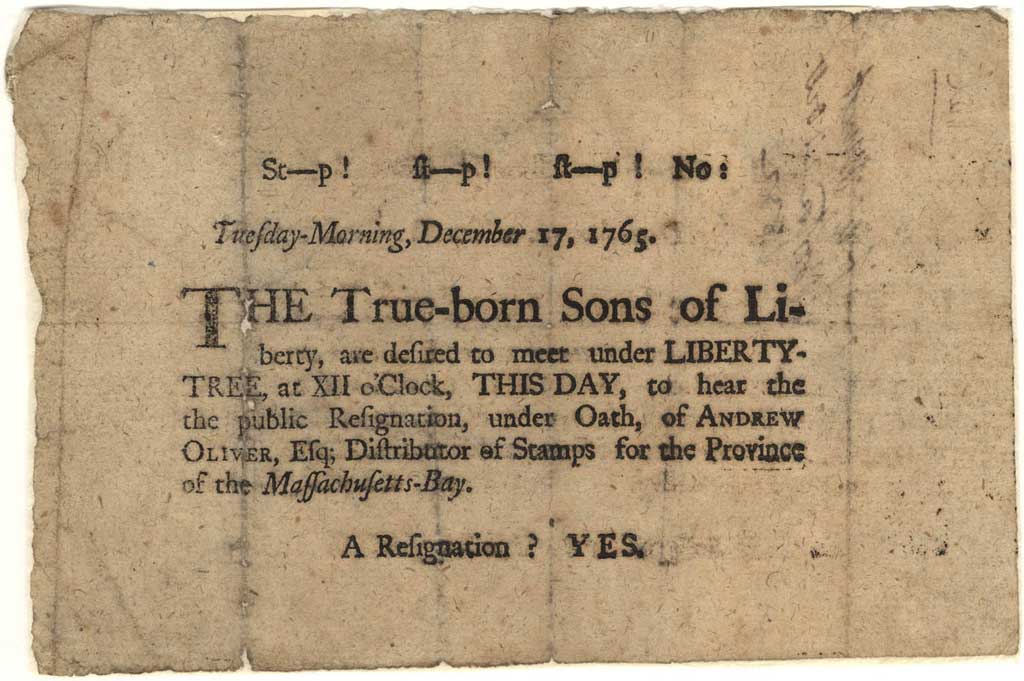

The introduction of the Stamp Act in 1765 caused the first significant constitutional dispute over Britain’s taxing the colonists without their consent. The Stamp Act was designed to raise revenue from the colonies (to help pay for the cost of troops on the frontier) by taxing legal forms and printed materials including newspapers; a stamp was placed on the document to indicate that the duty had been paid. Because the colonists had long raised money for the crown through their own elected legislatures, to which they gave their consent, and because they did not have direct representation in Parliament, they cried, “No taxation without representation,” claiming their rights as Englishmen. Although the colonists accepted the British Parliament’s right to use tariffs as a means to regulate their commerce within the imperial system, they asserted that the new taxes were aimed solely to raise revenue. In other words, the Stamp Act imposed a direct tax on the colonists, taking their property without their consent, and, as such, amounted to a new power being claimed by the British Parliament. (See the Stamp Act Resistance Narrative.)

Early voices of protest and resistance came from attorney and farmer Patrick Henry in the Virginia House of Burgesses and lawyer John Adams outside Boston. A group of clubs organized in Boston. Members ransacked the houses of Andrew Oliver, the appointed collector of the Stamp Tax, and Thomas Hutchinson, the colony’s lieutenant governor. Calls for active resistance came from the Sons of Liberty, a group of artisans, laborers, and sailors led by Samuel Adams (cousin of John and a business owner quickly emerging as a leader of the opposition). Petitions, protests, boycotts of articles bearing the stamp, and even violence spread to other cities, including New York, and demonstrated that the colonists’ resolve could keep the Stamp Tax from being collected.

This 1765 engraving entitled “Stamp Master in Effigy” depicts an angry mob in Portsmouth New Hampshire hanging a Crown-appointed stamp master in effigy. (credit: “New Hampshire—Stamp Master in Effigy ” courtesy of the New Hampshire Historical Society)

Meanwhile, delegates from nine colonies met in New York as the Stamp Act Congress to register a formal complaint in October 1765. The Congress was a show of increasing unity; it declared colonial rights and petitioned the British Parliament for relief.

The colonial boycott of British goods in response to the Stamp Act had its desired effect: British merchants affected by it petitioned the crown to revoke the taxes. In the face of this colonial resistance, a new government took leadership in Parliament and in 1766 repealed the Stamp Act. The colonists celebrated and thought the crisis was resolved. However, the British Parliament simultaneously passed the Declaratory Act, asserting its authority with the power to legislate for the colonies “in all cases whatsoever,” including taxing without consent. The stage was set to continue the conflict.

Like their British counterparts, many Americans adopted the custom of drinking tea. How does this teapot c. 1770 show the politicization of the cultural habit of tea drinking? (credit: “No Stamp Act Teapot ” Division of Cultural and Community Life National Museum of American History Smithsonian Institution)

Just one year later, Parliament began to pass the so-called Townshend Acts. The first of these was the Revenue Act, which taxed many goods imported by the colonies, including paint, glass, lead, paper, and tea. Despite the stationing of British troops in Boston to quell resistance, artisans and laborers protested the taxes, while in nonimportation agreements (boycotts), merchants and planters pledged not to import taxed goods. Women resisted the tax by rejecting the consumer goods of Great Britain, producing homespun clothing and brewing homemade concoctions rather than buying imported British cloth and tea. They organized into groups called the Daughters of Liberty to play their part in resisting what they viewed as British tyranny, and they formed the backbone of the nonconsumption movement not to use British goods. John Dickinson, a wealthy lawyer, penned the most significant protest, Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania. The tax “appears to me to be unconstitutional,” he wrote, and “destructive to the liberty of these colonies.” The key question was whether “the parliament can legally take money out of our pockets, without our consent.” The colonists’ boycott significantly hurt British trade and few taxes were collected, so Parliament revoked the Townshend Acts in 1770, leaving only the tax on tea. (See the John Dickinson Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania 1767-1768 Primary Source.)

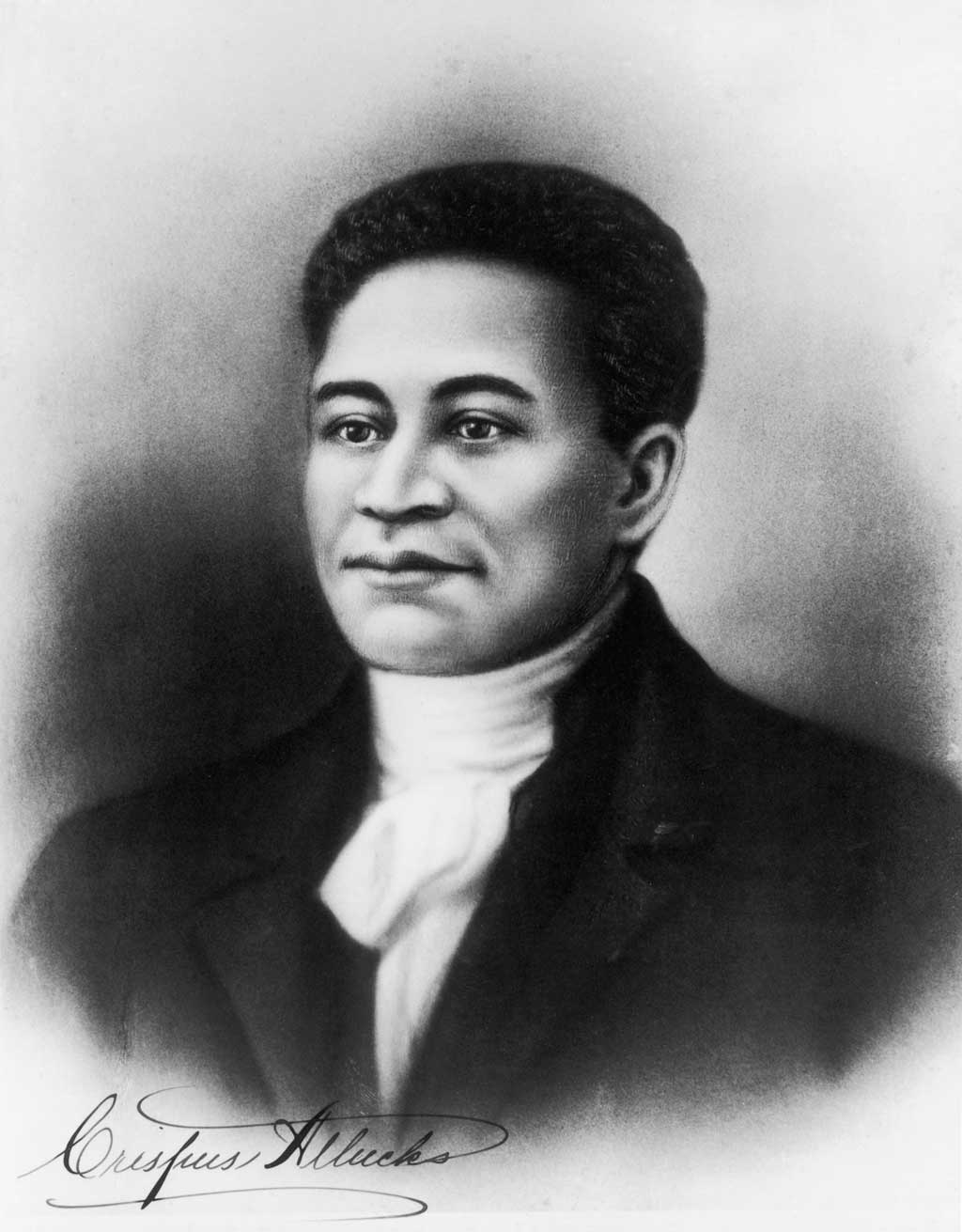

British officials had stationed troops in urban areas, especially New York and Boston, to quell the growing opposition movements. Their presence led to numerous smaller incidents and eventually to the eruption of violence in Boston. In March 1770, soldiers guarding the Boston Customs House were pelted with rocks and ice chunks thrown by angry colonists. Feeling threatened, they fired into the crowd, killing six Bostonians. The soldiers claimed they had fired in self-defense, but colonists called it a cold-blooded slaughter. This was the interpretation put forward by the silversmith Paul Revere in his widely reproduced engraving of the event, now called the “Boston Massacre.” The soldiers soon faced trial, and John Adams—although no friend of British taxation—served as their defense attorney to prove that colonists respected the rule of law. Remarkably, he convinced the Boston jury of the soldiers’ innocence, but tensions continued to simmer. (See The Boston Massacre Narrative.)

Boston was ripe for resistance to British demands when Parliament issued the 1773 Tea Act. The intention was to save the British East India Company from bankruptcy by lowering the price of tea (to increase demand) while assessing a small tax along with it. Colonists saw this as a trap, using low prices to induce them to break their boycott by purchasing taxed tea from the East Indian monopoly. Before the three ships carrying the tea could be unloaded at Boston harbor, the Sons of Liberty organized a mass protest in which thousands participated. Men disguised themselves as American Indians (to symbolize their love of natural freedom), marched to the ships, and threw the tea into Boston Harbor—an event later called “the Boston Tea Party”. (See The Boston Tea Party Narrative.)

This portrayal of the Boston Tea Party dates from 1789 and reads “Americans throwing Cargoes of the Tea Ships into the River at Boston.” On the basis of the image and the artist’s caption do you think the artist was sympathetic to the Patriot or the British cause?

Parliament could not overlook this defiance of its laws and destruction of a significant amount of private property. In early 1774, it passed what it called the Coercive Acts to compel obedience to British rule. The Boston Port Act closed Boston Harbor, the main source of livelihood for many in the city. Other acts gained tighter control of the judiciary in the colony, dissolved the colonial legislature, shut down town meetings, and allowed Parliament to tear up the Massachusetts charter without due process or redress. The colonists called these laws the “Intolerable Acts.” Meeting in Philadelphia in September and October 1774, representatives of the colonies discussed how to respond. This First Continental Congress was an expression of intercolonial unity. The representatives agreed to send help to Boston, boycott British goods, and affirm their natural and constitutional rights. Few contemplated independence; most hoped to bring about a reconciliation and restoration of colonial rights. The representatives also agreed to meet again, in the spring of 1775. By that time, events had taken a very different course. (See the Acts of Parliament Lesson.)

From Lexington and Concord to Independence

Some Patriots in the colonies sought more radical solutions than reconciliation. Early in 1775, Patrick Henry tried to rouse the Virginia House of Burgesses to action:

The war is inevitable—and let it come! . . . Is life so dear or peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me give me liberty or give me death!

Around the same time, Major General Thomas Gage, Britain’s military governor of Massachusetts, planned to seize colonial munitions held at Concord and capture several Patriot leaders, including Samuel Adams and John Hancock, along the way. On April 18, 1775, when it became clear the British were preparing to move, riders were dispatched to alert the countryside, most famously Paul Revere (in a trip immortalized by the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow). As a result, the following morning, the Lexington militia gathered on Lexington Green to stand in protest. As the British column advanced, its commander ordered the colonists to disperse. A shot rang out—no one knows from where. The British opened fire, and after the skirmish, seven Lexington men lay dead.

The British advanced to Concord, where by now the supplies had been safely hidden away. After witnessing British destruction in the town, the Concord militia counterattacked at the North Bridge. This was Emerson’s “shot heard round the world.” Militia units converged from all over eastern Massachusetts, pursued the British back to Boston, and besieged the city. One militiaman who survived was young Levi Preston. Years afterward, he reported that “what we meant in going for those Redcoats was this: we had always governed ourselves and we always meant to. They didn’t mean we should.”

On June 17, 1775, the Battle of Bunker Hill erupted when the colonial troops seized and fortified Breed’s Hill and repulsed three British attacks. Running low on ammunition, the colonists held their fire until the last moment under the command, “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes.” The British captured their position—and suffered unexpectedly high casualties—but the battle galvanized the colonists. Although they were still divided, many came to believe that King George, instead of merely having bad advisors or making bad policies, was openly going to war with them. Arguments for independence began to gain traction. The build-up to the call for independence had been long, but now there seemed no other recourse. (See The Path to Independence Lesson.)

One key voice urging independence was that of Thomas Paine, a recent immigrant from England. In early 1776, Paine published Common Sense, a bestseller in which he attacked monarchy generally before suggesting the folly of an island (Britain) ruling a continent (America). Paine called on the colonists “to begin the world over again” and was one of the clearest voices pushing them toward independence. (See the Thomas Paine Common Sense 1776 Primary Source.)

(a) Thomas Paine’s Common Sense helped convince many colonists of the need for independence from Great Britain. (b) Paine shown here in a portrait by Laurent Dabos was a political activist and revolutionary best known for his writings on both the American and French Revolutions.

The Second Continental Congress debated the question of independence in 1776. The commander of the Continental Army, George Washington of Virginia, agreed with Henry Knox’s audacious plan to bring massive cannons three hundred miles through the winter snows from Fort Ticonderoga to Boston. When Knox succeeded, Washington used the guns to end the siege of Boston. At the congress, cousins Samuel and John Adams argued for independence and convinced a Virginia ally, Richard Henry Lee to offer this motion on June 7:

That these United Colonies are and of right ought to be free and independent States that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is and ought to be totally dissolved.

Confronting its choices Congress also appointed a committee to prepare a Declaration of Independence. The committee consisted of John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, Robert R. Livingston, and Thomas Jefferson a 33-year-old Virginian who accepted the task of drafting the important document. (See Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence Narrative.)

No contemporary images of the Constitutional Congress survive. Robert Edge Pine worked on his painting Congress Voting Independence from 1784 to 1788. How has this artist conveyed the seriousness of the task the delegates faced?

When the votes were tallied for Lee’s resolution about a month later on July 2, twelve states had voted for independence; New York abstained until it received instructions from its legislature. John Adams later wrote that it was as if “thirteen clocks were made to strike together.” The next two days were spent revising the language of the official Declaration, which Congress approved on July 4, 1776.

The Declaration of Independence laid down several principles for the independent nation. The document made a universal assertion that all humans were created equal. According to the ideas of John Locke and the Enlightenment, people were equal in their natural rights, which included life, liberty, and the ability to pursue happiness. The document also stated that legitimate governments derived their power from the consent of the governed and existed to protect those inalienable rights. According to this “social compact,” the people had the right to overthrow a tyrannical government that violated their rights and to establish a new government. The Declaration of Independence, which also included a list of specific instances in which the crown had violated Americans’ rights, laid down the principles of republican government dedicated to the protection of individual political, religious, and economic liberties. (See the Signing the Declaration of Independence Decision Point.)

Congress had made and approved the Declaration, but whether the country could sustain the claim of independence was another matter. The struggle would have to be won on the battlefield.

War and Peace

For independence to be secured, the war had to be fought and won. British generals aimed to secure the port cities, expand British influence, and gradually win the population back to a position of loyalty. They commanded a professional army but had to subdue the entire eastern seaboard. General Washington, on the other hand, learned how to keep the Continental Army in the field and take calculated risks in the face of a British force superior in number, training, and supplies. The support of the individual states, and the congressional effort to secure allies, were essential to the war effort, but they were not guaranteed. The British sent an army of nearly thirty-two thousand redcoats and German mercenaries. They also enjoyed naval supremacy and expected that their more-experienced generals would win an easy victory over the provincials. The campaigns of 1776, thus, were about survival.

After securing Boston, Washington moved his army to New York City, the likely target of the next British attack. In the summer of 1776, the British fleet arrived under the command of Admiral Richard Howe. It carried an army led by his brother, General William Howe, and consisted not only of British troops but also of German mercenaries from Hesse (the Hessians). The first blow came on Long Island, where British attacks easily threw Washington’s army into disarray. Washington led his army in retreat to Manhattan, and then from New Jersey all the way into Pennsylvania. By the end of the year, his situation looked bleak. Many of Washington’s soldiers, about to come to the end of their enlistments, would be free to depart. If Washington could not keep his army in the field or show some success, the claim of independence might seem like an empty promise.

It was critical, therefore, to rally the troops to a decisive victory. Washington and his officers decided on the bold stroke of attacking Trenton. On Christmas evening, they crossed the Delaware River and marched through the night to arrive in Trenton at dawn on December 26. There, they surprised the Hessian outpost and captured the city. Washington then launched a quick strike on nearby Princeton. The success of this campaign gave the Americans enough hope to keep fighting. (See the Washington Crossing the Delaware Narrative and the Art Analysis: Washington Crossing the Delaware Primary Source.)

The campaigns of 1777 brought highs and lows for supporters of independence. On the positive side, the Continental Army successfully countered a British invasion from Canada. Searching for a new strategy after the New Jersey campaign, the British attacked southward from Canada with an army under the leadership of General John Burgoyne. Burgoyne’s goal was to cut through upstate New York and link up with British forces coming north along the Hudson River from New York City. A revolutionary force under Horatio Gates and Benedict Arnold swung north to meet the slow-moving Burgoyne, clashing at Saratoga, near Albany, in September and October. There, the Americans forced Burgoyne to surrender his entire army. (See The Battle of Saratoga and the French Alliance Narrative.)

The victory at Saratoga proved especially significant because it helped persuade the French to form an alliance with the United States. The treaty of alliance, brokered by Franklin and signed in early 1778, brought much-needed financial help from France to the war effort, along with the promise of military aid. But despite the important victory won by General Gates to the north, Washington continued to struggle against the main British army.

John Trumbull painted this wartime image of Washington on a promontory above the Hudson River. Washington’s enslaved valet William “Billy” Lee stands behind him and British warships fire on a U.S. fort in the background. Lee rode alongside Washington for the duration of the Revolutionary War.

For Washington, 1777 was dispiriting in that he failed to win any grand successes. The major battles came in the fall, when the British army sailed from New York and worked its way up the Chesapeake Bay, aiming to capture Philadelphia, the seat of American power where the Continental Congress met. Washington tried to stop the British, fighting at Brandywine Bridge and Germantown in September and October. He lost both battles, and the defeat at Germantown was especially severe. The British easily seized Philadelphia—a victory, even though Congress had long since left the capital and reconvened in nearby Lancaster and York. The demoralized Continentals straggled to a winter camp at Valley Forge, where few supplies reached them, and Washington grew frustrated that the states were not meeting congressional requisitions of provisions for the troops. Sickness incapacitated the undernourished soldiers. Many walked through the snow barefoot, leaving bloody footprints behind. (See the Joseph Plumb Martin The Adventures of a Revolutionary Soldier 1777 Primary Source.)

Here again, Washington provided significant leadership, keeping the army together through strength of character and his example in the face of numerous hardships. Warmer weather energized the army. So did Baron Friedrich von Steuben, newly arrived from Prussia, whom Washington had placed in charge of drilling the soldiers and preparing them for more combat. In June 1778, a more professional, better disciplined Continental Army battled the British to a draw at the Battle of Monmouth, as the imperial army withdrew from Philadelphia and returned to New York.

As the war raged, it affected different groups of Americans differently. Many Loyalists (also known as Tories) were shunned by their communities or forced to resettle under British protection. Women who sympathized with the revolution supported the war effort by creating homespun clothing, often working in groups at events in their homes called “spinning bees.” When men went to war, the women kept family farms, businesses, and artisan shops operating, producing supplies the army could use. While her husband, John, held important offices, Abigail Adams took much of the responsibility for the family’s farm in Braintree, Massachusetts. She even collected saltpeter for the making of gunpowder. Some colonial women followed their brothers and husbands to war, to support the Continental Army by cooking for the camp and nursing injured soldiers. Their engagement with the revolutionary cause brought new respect and contributed to the growth of an idea of “Republican Mothers” who raised patriotic and virtuous children for the new nation. Although women did not enjoy widespread equal civil rights, adult women of New Jersey exercised the right to vote in the early nineteenth century if, like their male counterparts, they served as heads of households meeting minimum property requirements. (See the Abigail Adams: “Remember the Ladies” Mini DBQ Lesson and the Judith Sargent Murray “On the Equality of the Sexes ” 1790 Primary Source)

To African American slaves in the South, the British appeared to offer better opportunities. In 1775, Lord Dunmore the royal governor of Virginia, offered men enslaved by Patriots their freedom if they would take up arms against the colonists. Many did, although few had gained their freedom by the conclusion of the war. Meanwhile, Dunmore’s proclamation made southern planters even more determined to oppose British rule. No such offer of freedom was forthcoming from the Patriots.

Dunmore’s 1775 proclamation of freedom for slaves who took the loyalists’ side was made for practical reasons more than moral ones: Dunmore hoped to bolster his own forces and scare slave-owning Patriots into abandoning their calls for revolution.

The Continental Congress removed harsh criticism of the slave trade and slavery from Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence, because it wrongly blamed the king for the slave trade and ignored American complicity. Later, John Laurens and Alexander Hamilton failed in their efforts to free and arm slaves in South Carolina. Despite some southern opposition, Washington eventually allowed free blacks to enlist in the Continental Army. Free black sailors such as Lemuel Haynes, who became a prominent minister after the war, served in the navy. Largely from the North, these men helped Washington’s army escape from Long Island and cross the Delaware River. In most cases, they served alongside white soldiers in integrated units. Rhode Island and Massachusetts also raised companies entirely of free black soldiers. The natural-rights principles of the Revolution inspired the push to eliminate slavery in the North, either immediately or gradually, during and after the war.

American Indians would have preferred to stay neutral in the Anglo-American conflict, but choices were often forced on them. Some tribes sided with the British, fearing the unchecked expansion of American settlers. Most members of the Iroquois League allied themselves with the British and, led by Joseph Brant, launched raids against Patriot communities in New York and Pennsylvania. Many other tribes along the frontier, including the Shawnee, Delaware, Mohawk, and Cherokee, also fought with the British. The need to deal with Indian raids was one reason for George Rogers Clark’s mission to seize western lands from the British. His victories at Kaskaskia and Vincennes, in present-day Illinois and Indiana, respectively, significantly reduced British strength in the Northwest Territory by 1779.

In contrast, many fewer tribes fought on the side of the Americans. By deciding to do so, the Oneida split the Iroquois League. Other American Indian groups living in long-settled areas also sided with the United States, including the Stockbridge Indians of Massachusetts and the Catawbas in the Carolinas. Many American frontiersmen treated Indian settlements with great violence, including a destructive march through Iroquois lands in New York in 1779 and the massacre of neutral American Indians at the Moravian village of Gnadenhutten in eastern Ohio a few years later. These conflicts deepened hostilities between American Indians and white settlers and helped whites justify the westward expansion of the frontier after the war.

After 1778, the British turned their attention to the South, where they hoped to rally Loyalist support. The major port of Charleston, South Carolina, easily fell to the British general Henry Clinton in May 1780. Pacifying the rest of the South fell to General Charles Cornwallis. He dueled across the Carolinas with the U.S. general Nathanael Greene. Encounters at King’s Mountain and Cowpens were indecisive or narrow American victories, but they effectively neutralized larger British forces in the South. After fighting at Guilford Courthouse, Cornwallis decided to head north into Virginia. He settled at Yorktown and built defenses with the expectation that the British navy would arrive to bring his army back to New York. However, in the Battle of the Capes (September 1781), the French navy defeated the British force sent to relieve Cornwallis. As a result, Cornwallis remained stuck at Yorktown.

Recognizing an opportunity, the French Marquis de Lafayette alerted Washington, who brought the main body of his army south with French forces under Rochambeau to confront Cornwallis. As the Americans strengthened their siege with the help of French engineers, command of several actions fell to Washington’s former aide, Alexander Hamilton. After separate forces of American and French troops captured two fortifications in the British outworks with a bayonet charge, Cornwallis realized he had no choice but to surrender.

John Trumbull’s 1819-1820 painting Surrender of Lord Cornwallis hangs in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol in Washington DC. American General Benjamin Lincoln appears mounted on a white horse and accepts the sword of the British officer to his right; Cornwallis was not present at the surrender. Note the American troops to General Lincoln’s left and the French troops to his right under the white flag of the French Bourbon monarchy.

The war continued for two more years, but there were no more significant battles. By capturing Cornwallis’s army, the revolutionaries had neutralized the most significant British force in America and cleared the way for American diplomats to broker peace. In Paris, Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay won British recognition of American independence. In the end, which came in 1783, not only was independence recognized, but the new nation gained a western border at the Mississippi River, unleashing a wave of immigration to settle the land west of the Appalachians.

Confederation and Constitution

The 1780s witnessed tensions between those who wished to maintain a decentralized federation and others who believed the United States needed a new constitutional republic with a strengthened national government. The first framework of government, the Articles of Confederation, sufficed for winning the war and resolving states’ disputes over land west of the Appalachians. Yet many believed the government created by the Articles had almost lost the war because it did not adequately support the army, and after the war it had failed to govern the nation adequately. With the nation’s independence recognized, Americans had to build a stable government in the place of the British government they had thrown off. Important debates emerged about the size and shape of the nation, continuities and breaks with the colonial past, and the character of a new governing system for a free people. Debates took place not only in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787 but also in public discussions afterward in the states. Throughout the process, Americans considered various constitutional forms, but they agreed on the significance of constitutional government.

As they thought about these questions, they faced many immediate challenges in recovering from the war. Tens of thousands of Loyalists refused to continue living in the new republic and migrated to Great Britain, the Caribbean, and, most often, Canada. Many states allowed their citizens to confiscate Loyalist property and not pay their debts to British merchants, in violation of the 1783 Treaty of Paris. Economic depression resulted from a shortage of currency and lost British trade connections; businesses worked for several years to recover.

The United States did not even have complete control over its territory. Britain kept troops on the frontier, claiming it needed to ensure compliance with the peace treaty. Spain crippled the western U.S. economy by shutting down American navigation of the Mississippi River and access to the Gulf of Mexico. Individual states failed to fulfill their agreements to creditors and to other states. They passed tariffs on each other and nearly went to war over trade disputes.

In the face of these challenges, the first framework of government to be adopted was the Articles of Confederation. Although Congress began the process of drafting it shortly after independence and adopted the document in 1777, it approved a final version only in 1781. First, the title is significant: The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union. The Articles set up a Confederation, or a league of friendship, not a nation. The states maintained their separate sovereignties and agreed to work together on foreign affairs but little else. As a result, the central government was intentionally weak and made up of a unicameral Congress that had few powers. It did not have the power to tax, so funds for the Confederation were supposed to come from requests made to the states. There was no independent executive or judiciary. Important decisions required a supermajority of nine of the thirteen states. Significantly, the adoption of amendments or changes to the document had to be unanimous. Several attempts at reforming the Articles, such as granting Congress the power to tax imports, failed by votes of twelve to one. As a result, government was adrift, and many statesmen such as Madison, Hamilton, and Washington began thinking about stronger, more national solutions. (See The Articles of Confederation 1781 Primary Source and the Constitutional Convention Lesson.)

Watch this BRI Homework Help video on the Articles of Confederation to review their weaknesses and why statesmen desired a stronger central government.

Nationalists such as Madison were also concerned about tyrannical majorities’ violations of minority rights in the states. For example, in Virginia, Madison helped promote freedom of conscience or religious liberty. He successfully won passage of Jefferson’s Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which formally disestablished the official church and protected religious liberty as a natural right. The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom later provided a precedent for the First Amendment. Protecting political and religious liberties became key components in the creation of a stronger constitutional government. (See the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom Narrative.)

Even with all its problems, the Confederation Congress did achieve great success with the settlement of the West. It created the Ordinance of 1784, which provided for the entrance of new states on an equal footing with existing ones, and for their republican government. Jefferson’s proposal to forever ban slavery in the West failed by one vote. The Northwest Ordinance, enacted a few years later in 1787, was a thoughtful response to the question of how to treat a territory held by the national government. Each territory, as it gained population, would elect a territorial legislature, draft a republican constitution, and gain the status of a state. Through this process, the Old Northwest eventually became the states of Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin. At the same time, the Northwest Ordinance’s final articles established the protection of the rights of residents, including the rights of habeas corpus and the right to a trial by jury. It provided for public education to advance knowledge and virtue. Also, very significantly, the ordinance permanently outlawed slavery north of the Ohio River. Not only did this decision keep those future states free, it also demonstrated the principle that the national government could make decisions about slavery in new territories. (See The Northwest Ordinance 1787 Primary Source.)

The first steps leading to a new Constitutional Convention were small. Concerns about trade and the navigation of the Chesapeake led to a 1785 meeting, hosted by Washington at Mount Vernon, between delegates from Virginia and Maryland. That meeting prompted more ambitious designs. Madison, a young Virginia lawyer and landowner, urged Congress to call for a new convention to be held in Annapolis, Maryland, in 1786. Nationally minded leaders from several states attended, including Madison, Hamilton from New York, and Dickinson from Delaware. Because of the late invitation, however, five other states sent delegates who arrived only after the meeting had disbanded, so a quorum was never reached. The one accomplishment of the Annapolis Convention was to ask Congress to call for another convention to be held in 1787 in Philadelphia. This was the Constitutional Convention. (See The Constitutional Convention Narrative and The Annapolis Convention Decision Point.)

As states prepared for the new convention in Philadelphia, word came of a popular uprising in Massachusetts. To pay off its Revolutionary War debts, the Massachusetts legislature had increased taxes. This move was met with active resistance in the western part of the state, where many farmers feared losing their land because they could not make the payments due to a credit crunch, recession, and high taxes. The insurgents wanted to cut taxes, print money, abolish the state senate, and revise the state constitution. Under the leadership of Daniel Shays, a farmer and former revolutionary soldier, they closed the courts in Springfield to prevent property foreclosures and defied the state government. By January 1787, Shays’ Rebellion had dissipated—the state legislature had raised an army to put down the uprising, and its leaders had fled. Still, officials feared disorder would spread if the government were not strengthened. Henry Knox strongly advocated for reform, and the idea was accepted by many revolutionary leaders, including Knox’s friend and fellow nationalist, George Washington. (See the Shays’ Rebellion Narrative.)

As a result, when the delegates assembled in Philadelphia, in the same hall where Congress had declared independence, they did so with a sense of urgency. They opted for secrecy to ensure free deliberation, allow delegates to change their minds, and prevent outside pressures from swaying the debates. They even ordered the windows nailed shut—quite a discomfort through the summer months. One important first step was to name someone to preside over the convention, and this honor fell to Washington. His presence lent moral seriousness and credibility to the whole endeavor. Members of the assembled convention soon concluded that the Articles of Confederation were beyond saving, and a new frame of government would be required, even though this goal surpassed their mandate to revise the Articles. At this point, Edmund Randolph of Virginia stepped forward with the proposal for a new plan of government conceived by fellow Virginian Madison (who was also keeping extensive notes of the convention, despite a rule against doing so).

Madison’s Virginia Plan favored large states by opting for a bicameral Congress with representation in both houses to be determined by population size alone. This irked the smaller states, which responded with the New Jersey Plan, adhering to the existing practice of allowing all states equal representation in an assembly. With two opposing visions, there seemed no clear path forward, and some delegates feared the convention would falter. From this conflict, however, a third plan emerged, shaped by Sherman and other delegates from Connecticut. This Connecticut Compromise or “Great Compromise” delineated the bicameral Congress we have today, with separate houses each offering a different means of representation: proportional to population in the House of Representatives and equal in the Senate, where each state would elect two senators. The crisis had been averted. (See Argumentation: The Process of Compromise Lesson.)

The convention then moved on to other matters. For instance, delegates considered the nature of the executive—a potentially delicate topic given that the presumed first executive was Washington. Hamilton argued for a very strong executive, possibly even one elected for life. However, although the convention created the presidency, it also hemmed it in, to be checked by the other branches. The Electoral College, in which each state’s votes were equal to the sum of its two senators plus its number of representatives in the House, was instituted as another part of the federal system. Significantly, the delegates spent minimal time on the federal judiciary, leaving the responsibility of defining its role to the new government.

The framers also faced the dilemma of how to address the institution of slavery. Delegates from the Deep South threatened to walk out of the convention if a new constitution endangered it. As a result, the convention’s treatment of slavery was ambiguous. The Constitution never mentions “slaves” or “slavery.” Even so, practical considerations made it impossible to ignore. Whereas delegates from the North did not think slaves should count toward the population totals establishing representation in Congress but should count for taxation, southern delegates disagreed, arguing the opposite. The “Three-Fifths Compromise” resolved that, although free people would be counted in full, only three-fifths of the number of “all other Persons” would be applied to state population totals for purposes of congressional apportionment and taxation. A precedent set by the Articles of Confederation also guided the compromise. In addition, after the convention voted down a southern proposal to prevent congressional interference with the international slave trade, the national government gained the power, after 1808, to choose to prohibit the “Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit.” (See the Is the Constitution a Proslavery Document? Point-Counterpoint.)

After most of the debates were finished, the convention’s ideas were put into words by a Committee of Style, including Gouverneur Morris of New York. By September 1787, the proposed constitution was ready to be sent to the Confederation Congress and then to the state legislatures to be submitted to popular ratifying conventions consisting of the people’s representatives. One of the most important provisions at this point stated that only nine of thirteen states had to ratify the document for it to go into effect in the states where it had been approved.

Watch this BRI Homework Help video on the Constitution for a comprehensive review of the philosophies behind the Constitution.

With the Constitution now public, citizens across the country could make it a topic of scrutiny and debate. This was one of the convention’s goals: The Preamble was rooted in popular sovereignty when it claimed to express the will of “We, the People of the United States.” The Constitution was to be considered at special state conventions and not by state legislatures, for instance, because the framers anticipated state politicians would resist the Constitution’s diminishing of the power of the states. In these conventions, nationalists who supported the Constitution seized the name “Federalists,” alluding to federalism or the sharing of powers between the nation’s and states’ governments. Already well organized, Federalists coordinated their efforts in the various states. They could call on many polished writers for support. John Dickinson, for instance, wrote a series of essays called The Letters of Fabius. Even more famously, Hamilton, Jay, and Madison united to write the Federalist Papers, signing their collected efforts with the Latin pseudonym “Publius.”

The Federalist Papers made practical and theoretical arguments in favor of strengthening the nation’s government through the proposed constitution. Although many other voices also supported the Constitution at that time, people still look to The Federalist Papers for important insights into the thoughts of the framers of the Constitution. The people labeled “Anti-Federalists,” however, were suspicious of the Constitution and its grant of power to a national government. Considering themselves defenders of the Articles of Confederation and its own federal system, they worried that, like the British government in the 1760s and 1770s, the distant new authority proposed by the Constitution would usurp the powers of their states and violate citizens’ individual rights. Many of them also wrote pseudonymously, taking names like Brutus—the Roman assassin of power-grasping Caesar—or Federal Farmer. Many also had Revolutionary credentials, such as Patrick Henry and Samuel Adams. They worried Americans would relinquish the liberty they had just fought so hard to attain. As their name suggests, the Anti-Federalists came to be identified as an opposition voice, warning about the growth of a strong national government with great powers over taxation and the ability to raise standing armies that would endanger citizens’ rights.

(See the Federalist/Anti-Federalist Debate on Congress’s Powers of Taxation DBQ Lesson.)

As debates raged in newspapers and public houses, state conventions took up the Constitution. On December 7, 1787, Delaware became the first state to ratify it. The next four states—Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, and Connecticut—followed quickly. Pennsylvania’s Federalists so accelerated approval that Anti-Federalists had little chance to mount a real opposition. The others were small states that believed the Constitution would help them. Massachusetts came next, and there, because of Shays’ Rebellion, opinion was more divided. Still, Federalists rallied important Revolutionary leaders like Revere, Hancock, and Samuel Adams to achieve ratification. Maryland and South Carolina followed. (See The Ratification Debate on the Constitution Narrative.)

When New Hampshire voted “yes” in June 1788, Federalists rejoiced that nine states had ratified. However, two of the most populous states, Virginia and New York, still had to consider the Constitution. Federalists feared that failing to gain the support of either would threaten the legitimacy of the Constitution and the viability of the nine-state union already established. Madison and other Federalists battled Patrick Henry in an epic debate in Virginia, narrowly winning ratification. Hamilton and Jay similarly faced a powerful contingent of Anti-Federalists in New York, but this state also ratified the Constitution in the end. In both states, as had been the case in Massachusetts, Anti-Federalists gained Madison’s promise that the new government would quickly draft a Bill of Rights for the Constitution. The new government under the Constitution could move forward (temporarily without North Carolina and Rhode Island, which remained outside the new union for more than a year.)

The final result was that American citizens and their representatives, through a public debate, had agreed on a new form of government. They had passed the test Hamilton had set for them in Federalist Paper No. 1, determining that self-government was possible and that citizens could establish a government through “reflection and choice” rather than having it imposed by “accident and force.” Madison kept his word, and in the new Congress, he authored the ten amendments of the Bill of Rights and shepherded them to approval. The Anti-Federalists stayed engaged in politics and kept a wary eye on the new national government. The process, although often improvisational and hinging on the contingency, had been orderly and deliberative. In the American Revolution, statesmen and citizens had avoided military dictatorship and mass civilian bloodshed, creating a lasting system of government in which power was organized for the protection and promotion of liberty.

In the relatively short span of time between 1763 and 1789 the thirteen colonies went from loyal subjects of the British crown to open rebellion to an independent republic guided by the U.S. Constitution.

Additional Chapter Resources

- Mercy Otis Warren Narrative

- George Washington at Newburgh Decision Point

- Loyalist vs. Patriot Decision Point

- Were the Anti-Federalists Unduly Suspicious or Insightful Political Thinkers? Point-Counterpoint

- Quaker Anti-Slavery Petition 1783 Primary Source

- Belinda Sutton Petition to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts 1783 Primary Source

- Junípero Serra’s Baja California Diary Primary Source

- State Constitution Comparison Lesson

- Argumentation: Self-Interest or Republicanism? Lesson

Review Questions

1. Which of the following best describes the fiscal consequences of the French and Indian War?

- The French and Indian War caused the Northwest Territories to be absorbed into the British colonial government leading to an increase in British resources.

- The French and Indian War exploded the British national debt and tax burden leading to Parliament’s decision to tax the colonies to pay the war’s cost.

- The French and Indian War caused the colonies to realize their economic self-sufficiency and allowed colonial governments to impose taxes upon their citizens.

- The French and Indian War resulted in a British loss which left the British economically indebted to France and forced them to use the colonies to pay this debt.

2. Which act marked the first serious constitutional dispute over Parliament’s taxing the colonists without their consent?

- Declaratory Act

- Boston Port Act

3. At the conclusion of the French and Indian War what was the political status of the territory west of the Appalachian Mountains?

- Colonial settlers were forbidden to cross the Appalachian Mountains.

- The British government acquired this territory and governed it under the Northwest Ordinance.

- Colonial rebels were banished to these territories which were held by the British but very loosely governed.

- The French governed this territory as a colony until it was purchased by Jefferson in 1803.

4. What was the main purpose of the Stamp Act Congress?

- To declare independence from the British government

- To develop a new Constitution to govern the colonies

- To establish the Stamp Act and other tax legislation

- To formalize the colonial complaints against Parliament

5. What legislation was imposed on Massachusetts as a punishment for rebellious behavior during the “Tea Party” in December 1773?

- Coercive Acts

- Townshend Acts

6. How did the British use the institution of slavery as a tool against the colonists in the Revolutionary War?

- Southern slaveholders forced slaves to fight on their behalf.

- By promising freedom, in exchange for slaves’ support, the British encouraged Patriots’ slaves to rebel against their owners.

- Slaves were captured and forced to haul goods and supplies for the British army.

- The British saw slavery as evil and motivated slaves to fight to abolish the institution in the colonies.

7. Which of the following best describes the role of American Indian tribes in the Revolutionary War?

- American Indians mostly moved into the Northwest Territories to escape the conflict.

- American Indians often sided with the British although some fought alongside the colonists.

- American Indians unanimously supported the British cause in return for protection.

- American Indians generally supported the colonists believing that the colonists’ commitment to freedom and independence would make it more likely that Indians’ property rights would be protected.

8. Which of the following best describes the motives of the French military during the Revolutionary War?

- The French military supported the British because the French feared for the security of their own colonial holdings.

- The French military supported the American patriots against France’s rival the British to raise France’s own global political and economic standing.

- The French military was hired by Congress to fight on behalf of the rebels because the colonial population was much too small to successfully overthrow the British.

- The French military provided financial support to the Americans but remained physically uninvolved in the conflict.

9. What purpose did the Articles of Confederation serve?

- The Articles of Confederation served as the structure for the first government of the new United States.

- The Articles of Confederation listed Americans’ grievances against King George III.

- The Articles of Confederation were the first ten amendments to the Constitution which limited the federal government’s power.

- The Articles of Confederation created a new united nation with an effective national government.

10. Which of the following best describes the evolution of American colonists desiring independence?

- Immediately after the French and Indian War American colonists realized they would be better served economically and politically by full independence and advocated for it.

- After the British government passed the first direct tax American colonists created a delegation to discuss and legislate independence.

- After the Declaration of Independence was agreed upon by committee members all American colonists thoroughly supported the War for Independence.

- Incremental shifts toward independence were not complete even during the Revolution because tens of thousands of American colonists remained loyal to Britain.

11. Which of the following did not contribute to the call for a Second Continental Congress in 1776?

- The British attacks on Lexington and Concord and the violence at Bunker Hill

- The popularity of a pro-independence pamphlet written by Thomas Paine

- The need for a central entity to wage the resistance effort

- The successful alliance between American colonists and France to wage war against the British

12. Which of the following best describes George Washington’s leadership of the Continental Army?

- Fierce fighter who had an iron grip on the infantry units and who would use his war experience to influence the colonial legislature

- Long-term strategist willing to use new tactics to gain victories and boost morale

- Lackluster commander unable to successfully achieve the task of independence

- Extremely competitive personality who betrayed the revolutionary cause by siding with the British

13. Which battle is significant because it resulted in the creation of a successful alliance with the French?

- Battle of Lexington and Concord

- Battle of Trenton

- Battle of Saratoga

- Battle of Yorktown

14. A change in perception about American white women was the idea of Republican Motherhood which

- articulated that a woman’s ideal role was a mother with as many children as possible

- emphasized the importance of raising patriotic children to participate in the newly formed republic

- implemented a public education program that taught children how to be Republican

- identified women as equal to their male counterparts and entitled to access to the finances of the household

15. The Articles of Confederation were designed to

- maintain state sovereignty preventing the usurpation of power by a central government while allowing the states to function as a unit in military and diplomatic matters

- create a strong federal government that could unify the states as a nation

- mimic the powers of the British Crown without the ability to tax

- give a voice to each citizen of the United States regardless of race and gender

16. Which of the following constitutional issues most definitively highlighted the divide between Northern and Southern delegates at the Constitutional Convention?

- The Great Compromise

- The Electoral College

- The Three-Fifths Compromise

- An independent judiciary

17. Shays’ Rebellion is most similar to which earlier event in American history?

- Bacon’s Rebellion

- Pueblo Revolt of 1680

- Passage of the Proclamation of 1763

- Stono Rebellion

18. Which political faction was suspicious of the new Constitution and wary of the stronger authority of the federal government?

- Anti-Federalist

19. After ratification of the Constitution the Bill of Rights was designed to

- calm Anti-Federalist fears and protect individual freedoms from a stronger federal government

- promote the Federalist idea that the Constitution was an effective defense for inalienable rights

- establish the process for western territories to enter the union as states

- list the grievances perceived by Americans and share them with the world as a justification for rebellion

Free Response Questions

- Explain how a debate over liberty and self-government influenced the Continental Congress’s decision to declare independence in 1776.

- Describe the role of women during the American Revolution.

- Explain how the debates over individual rights and liberties continued to shape political debates after the American Revolution.

- Describe the changes and continuities in North American attitudes toward executive power between 1763 and 1789.

AP Practice Questions

“Their jurisprudence was marked with wisdom and dignity and their simplicity and piety were displayed equally in the regulation of their police the nature of their contracts and the punctuality of observance. The old Plymouth colony remained for some time a distinct government. They chose their own magistrates independent of all foreign control; but a few years involved them with the Massachusetts [colony] of which Boston more recently settled than Plymouth was the capital. From the local situation of a country separated by an ocean of a thousand leagues from the parent state and surrounded by a world of savages an immediate compact with the King of Great Britain was thought necessary. Thus a charter was early granted stipulating on the part of the crown that the Massachusetts [colony] should have a legislative body within itself composed of three branches and subject to no control except his majesty’s negative within a limited term to any laws formed by their assembly that might be thought to militate with the general interest of the realm of England. The governor was appointed by the crown the representative body annually chosen by the people and the council elected by the representatives from the people at large.”