Once upon a time: a brief history of children’s literature

Director, Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies, The University of Western Australia

Researcher, The University of Western Australia

Lecturer in medieval and early modern history, The University of Western Australia

Disclosure statement

Susan Broomhall receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Joanne McEwan receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Stephanie Tarbin receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

University of Western Australia provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

April 2 is International Children’s Book Day and the anniversary of the birth of one of the most famous contributors to this genre, Hans Christian Andersen . But when Andersen wrote his works, the genre of children’s literature was not an established field as we recognise today.

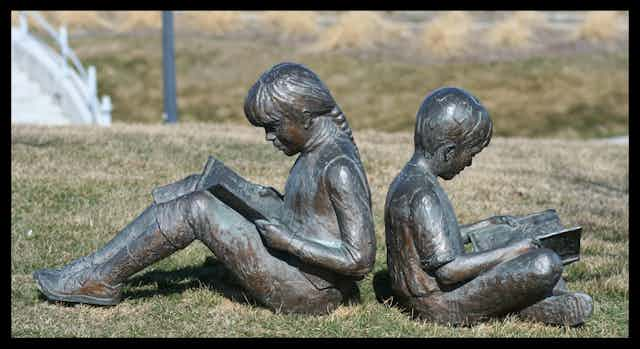

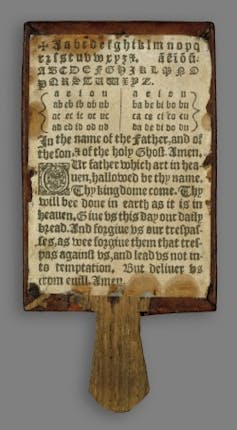

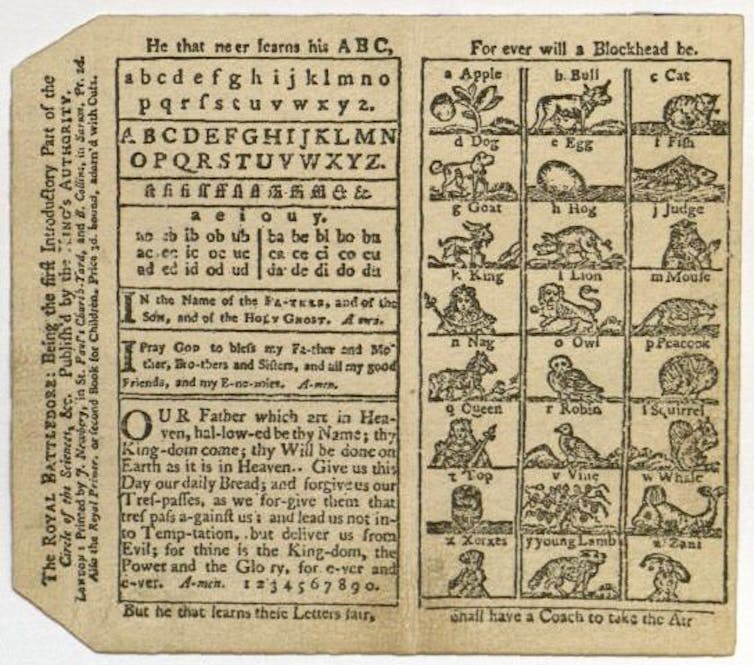

Adults have been writing for children (a broad definition of what we might call children’s literature) in many forms for centuries. Little of it looks much fun to us now. Works aimed at children were primarily concerned with their moral and spiritual progress. Medieval children were taught to read on parchment-covered wooden tablets containing the alphabet and a basic prayer, usually the Pater Noster. Later versions are known as “hornbooks”, because they were covered by a protective sheet of transparent horn.

Spiritually-improving books aimed specifically at children were published in the 17th century. The Puritan minister John Cotton wrote a catechism for children, titled Milk for Babes in 1646 (republished in New England as Spiritual Milk for Boston Babes in 1656). It contained 64 questions and answers relating to religious doctrine, beliefs, morals and manners. James Janeway (also a Puritan minister) collected stories of the virtuous lives and deaths of pious children in A Token for Children (1671), and told parents, nurses and teachers to let their charges read the work “ over a hundred times .”

These stories of children on their deathbeds may not hold much appeal for modern readers, but they were important tales about how to achieve salvation and put children in the leading role. Medieval legends about young Christian martyrs, like St Catherine and St Pelagius, did the same.

Other works were about manners and laid out how children should behave. Desiderius Erasmus famously produced a book of etiquette in Latin, On Civility in Children (1530), which gave much useful advice, including “don’t wipe your nose on your sleeve” and “To fidget around in your seat, and to settle first on one buttock and then the next, gives the impression that you are repeatedly farting, or trying to fart. So make sure your body remains upright and evenly balanced.” This advice shows how physical comportment was seen to reflect moral virtue.

Erasmus’s work was translated into English (by Robert Whittington in 1532) as A lytyll booke of good manners for children, where it joined a body of conduct literature aimed at wealthy adolescents.

In a society where reading aloud was common practice, children were also likely to have been among the audiences who listened to romances and secular poetry. Some medieval manuscripts, such as Bodleian Library Ashmole 61 , included courtesy poems explicitly directed at “children yong”, alongside popular Middle English romances, saints’ lives and legends, and short moral and comic tales.

Do children have a history?

A lot of scholarly ink has been spilled in the debate over whether children in the past were understood to have distinct needs. Medievalist Philippe Ariès suggested in Centuries of Childhood that children were regarded as miniature adults because they were dressed to look like little adults and because their routines and learning were geared towards training them for their future roles.

But there is plenty of evidence that children’s social and emotional (as well as spiritual) development were the subject of adult attention in times past. The regulations of late medieval and early modern schools, for example, certainly indicate that children were understood to need time for play and imagination.

Archaeologists working on the sites of schools in The Netherlands have uncovered evidence of children’s games that they played without input from adults and without trying to emulate adult behaviour. Some writers on education suggested that learning needed to appeal to children. This “progressive” view of children’s development is often attributed to John Locke but it has a longer history if we look at theories about education from the 16th century and earlier.

Some of the most imaginative genres that we now associate with children did not start off that way. In Paris in the 1690s, the salon of Marie-Catherine Le Jumel de Barneville, Baroness d’Aulnoy, brought together intellectuals and members of the nobility.

There, d’Aulnoy told “ fairy tales ”, which were satires about the royal court of France with a fair bit of commentary on the way society worked (or didn’t) for women at the time. These short stories blended folklore, current events, popular plays, contemporary novels and time-honoured tales of romance.

These were a way to present subversive ideas, but the claim that they were fiction protected their authors. A series of 19th-century novels that we now associate with children were also pointed commentaries about contemporary political and intellectual issues. One of the better known examples is Reverend Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby (1863), a satire against child labour and a critique of contemporary science.

The moral of the story

By the 18th century, children’s literature had become a commercially-viable aspect of London printing. The market was fuelled especially by London publisher John Newbery, the “father” of children’s literature. As literacy rates improved, there was continued demand for instructional works. It also became easier to print pictures that would attract young readers.

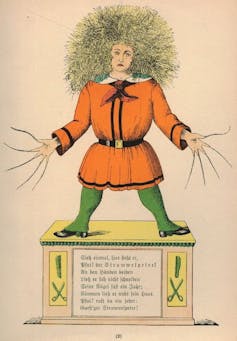

More and more texts for children were printed in the 19th century, and moralistic elements remained a strong focus. Katy’s development in patience and neatness in the “School of Pain” is key, for example, in Susan Coolidge’s enormously popular What Katy Did (1872), and feisty, outspoken Judy (spoiler alert!) is killed off in Ethel Turner’s Seven Little Australians (1894). Some authors managed to bridge the comic with important life lessons. Heinrich Hoffman’s memorable 1845 classic Struwwelpeter reads now like a kids’ version of dumb ways to die .

By the turn of the 20th century, we see the emergence of a “kids’ first” literature, where children take on serious matters with (or often without) the help of adults and often within a fantasy context. The works of Lewis Carroll, Robert Louis Stevenson, Mark Twain, Francis Hodgson Burnett, Edith Nesbit, JM Barrie, Frank L Baum, Astrid Lindgren, Enid Blyton, CS Lewis, Roald Dahl and JK Rowling operate in this vein.

Children’s books still contain moral lessons – they continue to acculturate the next generation to society’s beliefs and values. That’s not to say that we want our children to be wizards, but we do want them to be brave, to stand up for each other and to develop a particular set of values.

We tend to see children’s literature as providing imaginative spaces for children, but are often short-sighted about the long and didactic history of the genre. And as historians, we continue to seek out more about the autonomy and agency of pre-modern children in order to understand how they might also have found spaces in which to exercise their imagination beyond books that taught them how to pray.

- Fairy tales

- Children's books

- Hans Christian Andersen

Want to write?

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 181,200 academics and researchers from 4,924 institutions.

Register now

Children's Literature

Lisa Rowe Fraustino , Hollins University

Journal Details

Editorial correspondence should be addressed to:

The Editors Children's Literature Hollins University P.O. Box 9677 Roanoke, VA 24020 E-mail: [email protected]

Manuscripts submitted should conform to the style in this issue. Submission as an e-mail attachment (MS Word) is preferred. To facilitate anonymous review, the author’s name should not appear on the essay. Please provide full contact information in a separate document. Double-spacing should be used throughout text and notes.

The Hopkins Press Journals Ethics and Malpractice Statement can be found at the ethics-and-malpractice page.

Peer Review Policy

Children's Literature is the annual publication of the Children's Literature Association and the MLA Division on Children's Literature.

Essays submitted to Children's Literature should be original work that is not under review elsewhere. We will consider translations of previously published work, if the material is seen as useful for our readers. Submissions are initially reviewed by the editor. Strong submission are then sent to two reviewers. Both author and reviewers remain anonymous to each other throughout the process.

We publish theoretically-based articles that demonstrate an awareness of key issues and criticism in children’s literature. We typically require at least one round of revision in response to reviewers' comments; often published essays go through two or more rounds of revision. Accepted essay are edited by the editor, the JHUP copy-editor, and a proof reader. Authors can expect a twelve to twenty-four month time frame from first submission to publication.

Editor-in-Chief

Lisa Rowe Fraustino Hollins University

Book Review Editor

Melissa Jenkins, Wake Forest University

Editorial Assistant

Lisa J. Radcliff, Hollins University

Children’s Literature Advisory Board

Janice M. Alberghene, Fitchburg State University Ruth B. Bottigheimer, SUNY at Stony Brook Elisabeth Rose Gruner, University of Richmond Margaret Higonnet, University of Connecticut U. C. Knoepflmacher, Princeton University Roderick McGillis, University of Calgary

Children’s Literature Association Officers 2016–2017

Kenneth Kidd, University of Florida, President Teya Rosenberg, Texas State University, Vice President/President-Elect Annette Wannamaker, Eastern Michigan University, Past President Gwen Athene Tarbox, Western Michigan University, Secretary Roberta Seelinger Trites, Illinois State University, Treasurer

Children’s Literature Association Board of Directors

Philip Nel, Kansas State University , 2014-2017 Sara Schwebel, University of South Carolina , 2014-2017 Marah Gubar, Massachusetts Institute of Technology , 2015-2018 Joe Sutliff Sanders, Kansas State University , 2015-2018 Eric L. Tribunella, University of Southern Mississippi , 2015-2018 Thomas Crisp, Georgia State University , 2016-2019 Elisabeth Gruner, University of Richmond , 2016-2019 Jackie Horne, Independent Scholar , 2016-2019 Nathalie op de Beeck, Pacific Lutheran University , 2016-2019

Send books for review to: Melissa Jenkins English Department Wake Forest University P.O. Box 7387 Winston Salem, NC 27109-7387 Email queries to: [email protected]

Review copies received by the Johns Hopkins University Press office will be discarded.

Abstracting & Indexing Databases

- Web of Science

- Biography Index: Past and Present (H.W. Wilson), vol.22, 1994-vol.38, 2010

- Book Review Digest Plus (H.W. Wilson), 1988-

- Education Research Complete, 1/1/1993-

- Education Research Index, Jan.1993-

- Education Source, 1/1/1993-

- Humanities Abstracts (H.W. Wilson), 1/1/1988-

- Humanities Index (Online), 1988/00-

- Humanities International Complete, 1/1/1993-

- Humanities International Index, 1/1/1993-

- Humanities Source, 1/1/1988-

- Humanities Source Ultimate, 1/1/1988-

- Library & Information Science Source, 1/1/1972-1/1/1982

- MasterFILE Complete, 1/1/1993-

- MasterFILE Elite, 1/1/1993-

- MasterFILE Premier, 1/1/1993-

- MLA International Bibliography (Modern Language Association)

- OmniFile Full Text Mega (H.W. Wilson), 1/1/1988-

- Poetry & Short Story Reference Center, 1/1/1993-

- Professional Development Collection, 1/1/1993-

- RILM Abstracts of Music Literature (Repertoire International de Litterature Musicale)

- TOC Premier (Table of Contents), 1/1/1995-

- Book Review Index Plus

- Gale Academic OneFile

- Gale Academic OneFile Select, 01/1989-

- Gale General OneFile, 01/1989-

- Gale OneFile: Educator's Reference Complete, 01/1981-

- Gale OneFile: Leadership and Management, 01/1981 -

- InfoTrac Custom, 1/1981-

- ArticleFirst, vol.24, 1996-vol.39, no.1, 2011

- Electronic Collections Online, vol.31, no.1, 2003-vol.39, no.1, 2011

- Periodical Abstracts, v.19, 1991-2011

- Education Collection, 1/1/1991-

- Education Database, 1/1/1991-

- Literary Journals Index Full Text

- Periodicals Index Online

- Professional ProQuest Central, 01/01/1991-

- ProQuest 5000, 01/01/1991-

- ProQuest 5000 International, 01/01/1991-

- ProQuest Central, 01/01/1991-

- ProQuest Professional Education, 01/01/1991-

- Research Library, 01/01/1991-

- Social Science Premium Collection, 01/01/1991-

- The Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (ABELL)

Abstracting & Indexing Sources

- Children's Book Review Index (Active) (Print)

- Children's Literature Abstracts (Ceased) (Print)

- MLA Abstracts of Articles in Scholarly Journals (Ceased) (Print)

Source: Ulrichsweb Global Serials Directory.

0.4 (2022) 0.4 (Five-Year Impact Factor) 0.00007 (Eigenfactor™ Score) Rank in Category (by Journal Impact Factor): Note: While journals indexed in AHCI and ESCI are receiving a JIF for the first time in June 2023, they will not receive ranks, quartiles, or percentiles until the release of 2023 data in June 2024.

© Clarivate Analytics 2023

Published annually in May

Readers include: Librarians, teachers, writers, scholars, and those interested in children's literature

Children's Literature does not publish print advertisements.

Online Advertising Rates (per month)

Promotion (400x200 pixels) - $338.00

Online Advertising Deadline

Online advertising reservations are placed on a month-to-month basis.

All online ads are due on the 20th of the month prior to the reservation.

General Advertising Info

For more information on advertising or to place an ad, please visit the Advertising page.

eTOC (Electronic Table of Contents) alerts can be delivered to your inbox when this or any Hopkins Press journal is published via your ProjectMUSE MyMUSE account. Visit the eTOC instructions page for detailed instructions on setting up your MyMUSE account and alerts.

Also of Interest

Joseph Michael Sommers, Central Michigan University

Kate Quealy-Gainer, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Linda Mahood, University of Guelph

Dora Malech, Johns Hopkins University

David L. Russell, Ferris State University; Karin E. Westman, Kansas State University; and Naomi J. Wood, Kansas State University

Ted Atkinson, Mississippi State University

Adam Ross, The University of the South

Meghan O’Rourke

Nathan L. Grant, Saint Louis University

Charles Henry Rowell

Maria Farland, Fordham University and Duncan Faherty, Queens College and The CUNY Graduate Center

Chrysogonus Siddha Malilang, Malmö University, Sweden

Hopkins Press Journals

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Children's Literature

Introduction.

- General Reference Books

- Other Reference Resources

- Bibliographies

- Short Introductions

- General Introductions and Guides

- Anthologies

- Essay Collections

- Essay Collections from Journals and Conferences

- “Traditional” Criticism

- Literary Theory

- Interdisciplinary Criticism

- Language and Narrative

- Ecocriticism

- International

- New Zealand

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Disability and Death

- Gender Studies

- Multiculturalism and Translation

- Crossover Fiction

- Empire, Colonialism, and Postcolonialism

- Fairy Tales and Folktales

- Fantasy and Fantastic Realism

- Historical Fiction

- Horror and the Gothic

- Picture Books, Comics, and Illustration

- School Stories

- Science Fiction

- Popular Culture and Children’s Literature

- Children’s Literature in Education

- Children and Texts

- Collections of Essays

- 19th-Century Authors

- 20th-Century Authors

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Animations, Comic Books, and Manga

- Children and Animals

- Children's Media Culture

- Children’s Reading Development and Instruction

- Education: Learning and Schooling Worldwide

- Films for Children

- Images of Childhood, Adulthood, and Old Age in Children’s Literature

- Innocence and Childhood

- Literary Representations of Childhood

- Material Cultures of Western Childhoods

- Queer Theory and Childhood

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Agency and Childhood

- Childhood and the Colonial Countryside

- Colonialism and Human Rights

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Children's Literature by Peter Hunt LAST REVIEWED: 11 January 2022 LAST MODIFIED: 27 November 2013 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199791231-0014

The study of children’s literature as an academic discipline has developed since the 1980s from its roots in education and librarianship to its place in departments of literature and childhood studies. Although its practitioners position themselves at different points on the spectrum between “book-oriented” and “child-oriented,” the study is held together by the “presence” of some concept of child and childhood in the texts. The distinctions that apply in other literary systems between “literature” and “popular literature” or “literature” and “nonliterature” are not necessarily useful in this field. Nevertheless, criticism tends to fracture between a liberal-humanist and educationalist view that children’s literature should adhere to and inculcate “traditional” literary and cultural values and a more postmodern and theoretical view that texts for children are part of a complex cultural matrix and should be treated nonjudgmentally. In addition, the discipline is multi- and interdisciplinary as well as multimedia: its theory derives from disciplines such as literature, cultural and ideological studies, history, and psychology, and its applications range from literacy to bibliography. Consequently, children’s literature can be defined and limited in many (sometimes conflicting) ways: one major problem for scholars is that the term children’s is sometimes taken to transcend national and language barriers, thus potentially producing a discipline of unmanageable proportions. As a result, this article is eclectic, but it excludes specialist studies to which children’s books are peripheral or merely instrumental, such as folklore or teaching techniques. Children’s literature is also studied comparatively and internationally, with German and Japanese writing being particularly important. This article largely confines itself to English-language texts and translations into English.

Reference Resources

Children’s literature has been well catered for in terms of reference books, partly because the subject is of interest to the general public as well as to academics. General Reference Books thus range from large illustrated encyclopedic guides to collections of academic essays, as well as short introductions aimed primarily at students.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Childhood Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abduction of Children

- Aboriginal Childhoods

- Addams, Jane

- ADHD, Sociological Perspectives on

- Adolescence and Youth

- Adolescent Consent to Medical Treatment

- Adoption and Fostering

- Adoption and Fostering, History of Cross-Country

- Adoption and Fostering in Canada, History of

- Advertising and Marketing, Psychological Approaches to

- Advertising and Marketing, Sociocultural Approaches to

- Africa, Children and Young People in

- African American Children and Childhood

- After-school Hours and Activities

- Aggression across the Lifespan

- Ancient Near and Middle East, Child Sacrifice in the

- Animals, Children and

- Anthropology of Childhood

- Archaeology of Childhood

- Ariès, Philippe

- Attachment in Children and Adolescents

- Australia, History of Adoption and Fostering in

- Australian Indigenous Contexts and Childhood Experiences

- Autism, Females and

- Autism, Medical Model Perspectives on

- Autobiography and Childhood

- Benjamin, Walter

- Bereavement

- Best Interest of the Child

- Bioarchaeology of Childhood

- Body, Children and the

- Bourdieu, Pierre

- Boy Scouts/Girl Guides

- Boys and Fatherhood

- Breastfeeding

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie

- Bruner, Jerome

- Buddhist Views of Childhood

- Byzantine Childhoods

- Child and Adolescent Anger

- Child Beauty Pageants

- Child Homelessness

- Child Mortality, Historical Perspectives on Infant and

- Child Protection

- Child Protection, Children, Neoliberalism, and

- Child Public Health

- Child Trafficking and Slavery

- Childcare Manuals

- Childhood and Borders

- Childhood and Empire

- Childhood as Discourse

- Childhood, Confucian Views of Children and

- Childhood, Memory and

- Childhood Studies and Leisure Studies

- Childhood Studies in France

- Childhood Studies, Interdisciplinarity in

- Childhood Studies, Posthumanism and

- Childhoods in the United States, Sports and

- Children and Dance

- Children and Film-Making

- Children and Money

- Children and Social Media

- Children and Sport

- Children and Sustainable Cities

- Children as Language Brokers

- Children as Perpetrators of Crime

- Children, Code-switching and

- Children in the Industrial Revolution

- Children with Autism in a Brazilian Context

- Children, Young People, and Architecture

- Children's Humor

- Children’s Museums

- Children’s Parliaments

- Children's Views of Childhood

- China, Japan, and Korea

- China’s One Child Policy

- Citizenship

- Civil Rights Movement and Desegregation

- Classical World, Children in the

- Clothes and Costume, Children’s

- Colonial America, Child Witches in

- Colonization and Nationalism

- Color Symbolism and Child Development

- Common World Childhoods

- Competitiveness, Children and

- Conceptual Development in Early Childhood

- Congenital Disabilities

- Constructivist Approaches to Childhood

- Consumer Culture, Children and

- Consumption, Child and Teen

- Conversation Analysis and Research with Children

- Critical Approaches to Children’s Work and the Concept of ...

- Cultural psychology and human development

- Debt and Financialization of Childhood

- Discipline and Punishment

- Discrimination

- Disney, Walt

- Divorce And Custody

- Domestic Violence

- Drawings, Children’s

- Early Childhood

- Early Childhood Care and Education, Selected History of

- Eating disorders and obesity

- Environment, Children and the

- Environmental Education and Children

- Ethics in Research with Children

- Europe (including Greece and Rome), Child Sacrifice in

- Evolutionary Studies of Childhood

- Family Meals

- Fandom (Fan Studies)

- Female Genital Cutting

- Feminist New Materialist Approaches to Childhood Studies

- Feral and "Wild" Children

- Fetuses and Embryos

- Films about Children

- Folk Tales, Fairy Tales and

- Foundlings and Abandoned Children

- Freud, Anna

- Freud, Sigmund

- Friends and Peers: Psychological Perspectives

- Froebel, Friedrich

- Gay and Lesbian Parents

- Gender and Childhood

- Generations, The Concept of

- Geographies, Children's

- Gifted and Talented Children

- Globalization

- Growing Up in the Digital Era

- Hall, G. Stanley

- Happiness in Children

- Hindu Views of Childhood and Child Rearing

- Hispanic Childhoods (U.S.)

- Historical Approaches to Child Witches

- History of Childhood in America

- History of Childhood in Canada

- HIV/AIDS, Growing Up with

- Homeschooling

- Humor and Laughter

- Images of Childhood, Adulthood, and Old Age in Children’s ...

- Infancy and Ethnography

- Infant Mortality in a Global Context

- Institutional Care

- Intercultural Learning and Teaching with Children

- Islamic Views of Childhood

- Japan, Childhood in

- Juvenile Detention in the US

- Klein, Melanie

- Labor, Child

- Latin America

- Learning, Language

- Learning to Write

- Legends, Contemporary

- Literature, Children's

- Love and Care in the Early Years

- Magazines for Teenagers

- Maltreatment, Child

- Maria Montessori

- Marxism and Childhood

- Masculinities/Boyhood

- Mead, Margaret

- Media, Children in the

- Media Culture, Children's

- Medieval and Anglo-Saxon Childhoods

- Menstruation

- Middle Childhood

- Middle East

- Miscarriage

- Missionaries/Evangelism

- Moral Development

- Moral Panics

- Multi-culturalism and Education

- Music and Babies

- Nation and Childhood

- Native American and Aboriginal Canadian Childhood

- New Reproductive Technologies and Assisted Conception

- Nursery Rhymes

- Organizations, Nongovernmental

- Parental Gender Preferences, The Social Construction of

- Pediatrics, History of

- Peer Culture

- Perspectives on Boys' Circumcision

- Philosophy and Childhood

- Piaget, Jean

- Politics, Children and

- Postcolonial Childhoods

- Post-Modernism

- Poverty, Rights, and Well-being, Child

- Pre-Colombian Mesoamerica Childhoods

- Premodern China, Conceptions of Childhood in

- Prostitution and Pornography, Child

- Psychoanalysis

- Race and Ethnicity

- Racism, Children and

- Radio, Children, and Young People

- Readers, Children as

- Refugee and Displaced Children

- Reimagining Early Childhood Education, Reconceptualizing a...

- Relational Ontologies

- Relational Pedagogies

- Rights, Children’s

- Risk and Resilience

- School Shootings

- Sex Education in the United States

- Social and Cultural Capital of Childhood

- Social Habitus in Childhood

- Social Movements, Children's

- Social Policy, Children and

- Socialization and Child Rearing

- Socio-cultural Perspectives on Children's Spirituality

- Sociology of Childhood

- South African Birth to Twenty Project

- South Asia, History of Childhood in

- Special Education

- Spiritual Development in Childhood and Adolescence

- Spock, Benjamin

- Sports and Organized Games

- Street Children

- Street Children And Brazil

- Subcultures

- Teenage Fathers

- Teenage Pregnancy

- The Bible and Children

- The Harms and Prevention of Drugs and Alcohol on Children

- The Spaces of Childhood

- Theater for Children and Young People

- Theories, Pedagogic

- Transgender Children

- Twins and Multiple Births

- Unaccompanied Migrant Children

- United Kingdom, History of Adoption and Fostering in the

- United States, Schooling in the

- Value of Children

- Views of Childhood, Jewish and Christian

- Violence, Children and

- Visual Representations of Childhood

- Voice, Participation, and Agency

- Vygotsky, Lev and His Cultural-historical Approach to Deve...

- Welfare Law in the United States, Child

- Well-Being, Child

- Western Europe and Scandinavia

- Witchcraft in the Contemporary World, Children and

- Work and Apprenticeship, Children's

- Young Carers

- Young Children and Inclusion

- Young Children’s Imagination

- Young Lives

- Young People, Alcohol, and Urban Life

- Young People and Climate Activism

- Young People and Disadvantaged Environments in Affluent Co...

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|162.248.224.4]

- 162.248.224.4

(Stanford users can avoid this Captcha by logging in.)

- Send to text email RefWorks EndNote printer

Understanding children's literature : key essays from the second edition of The International companion encyclopedia of children's literature

Available online.

- EBSCO Academic Comprehensive Collection

More options

- Find it at other libraries via WorldCat

- Contributors

Description

Creators/contributors, contents/summary.

- 1. Introduction: The Expanding World of Children's Literature Studies Peter Hunt, Cardiff University

- 2. Theorising and Theories: How Does Children's Literature Exist? David Rudd, Bolton Institute

- 3. Critical Tradition and Ideological Positioning Charles Sarland, Liverpool John Moores University

- 4. The Setting of Children's Literature: History and Culture Tony Watkins, University of Reading

- 5. Analysing Texts: Linguistics and Stylistics John Stephens, Macquarie University

- 6. Readers, Texts, Contexts: Reader-Response Criticism Michael Benton, Professor Emeritus, University of Southampton

- 7. Reading the Unconscious: Psychoanalytical Criticism Hamida Bosmajian, Seattle University

- 8. Feminism Revisited Lissa Paul, University of New Brunswick

- 9. Decoding the Images: how Picture Books Work Perry Nodelman, University of Winnipeg

- 10. Bibliography: the Resources of Children's Literature Matthew Grenby, University of Newcastle upon Tyne

- 11. Understanding Reading and Literacy Sally Yates, Literacy Consultant UK

- 12. Intertextuality and the Child Reader Christine Wilkie-Stibbs, University of Warwick

- 13. Healing Texts: Bibliotherapy and Psychology Hugh Crago, Co-Editor Australia and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy

- 13. Theory into Practice: the Views of the Authors Peter Hunt, Cardiff University General Bibliography Glossary Index.

- (source: Nielsen Book Data)

Bibliographic information

Browse related items.

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous

- Next chapter >

Introduction

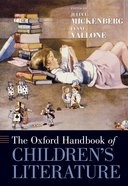

Julia Mickenberg is Associate Professor of American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. She is the author of the award-winning Learning from the Left: Children's Literature, the Cold War, and Radical Politics in the United States and coeditor of Tales for Little Rebels: A Collection of Radical Children's Literature.

Lynne Vallone is Professor and Chair of Childhood Studies at Rutgers University, the first Ph.D.-granting department of Childhood Studies in the United States. She is the author of Becoming Victoria and Disciplines of Virtue: Girls' Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries as well as co-associate general editor of the Norton Anthology of Children's Literature.

- Published: 18 September 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article presents the handbook's purposes and organization, and then briefly outlines some of the field's history, highlighting a number of key principles and important scholarly works. Finally, it turns to important issues related to four general rubrics. These rubrics, which serve as the structuring apparatus for the handbook, emerged organically from the essays and point to key areas of inquiry in children's literature study: Adults and Children's Literature; Pictures and Poetics; Reading History/Learning Race and Class; and Innocence and Agency. The discussion of these categories is designed to introduce the essays that are grouped under each of these rubrics (chronologically within each thematic section) and to situate the issues they raise within scholarship and literary history. The essays collected serve less to demarcate the field of children's literature than to push at the generic and gatekeeping boundaries that cordon off “children's literature” as a field of study.

The growing attention given to childhood as a category of analysis has infused the academic study of children’s literature with new energy. It has also highlighted the exciting and innovative aspects of children’s literature scholarship, which today benefits from the insights of historians, sociologists, psychologists, media studies scholars, political scientists, and legal scholars, as well as literary critics, education specialists, and library professionals. Focusing their analyses on children’s texts and children’s culture, contemporary scholars are producing theoretically sophisticated, politically engaged, and historicized yet wide-ranging work that marks this field as exceptionally dynamic. To mention only a few examples, recent work interrogating the roles of children and childhood in social, cultural and literary history includes studies of “boyology” and queer theory; child-rearing manuals and the Walt Disney company; radical children’s literature or the radical possibilities of children’s literature; African American children in slavery; the history of babysitting; postcolonial theory and American, Canadian, and Australian children’s books; and the “hidden adult” in children’s literature. 1 But even as the study of children’s literature attracts new scholars in a range of fields and gains in academic prestige, scholars in the field nonetheless can find themselves on slippery ground, experts in something that, arguably, kids might know more about than they do.

Back in 1984, Jacqueline Rose’s assertion in The Case of Peter Pan, Or, the Impossibility of Children’s Fiction that children’s literature was itself “impossible” startled children’s literature scholars: written by adults for children, children’s literature, she argued, is never “children’s;” instead, it represents an adult projection of what childhood is or ought to be. 2 Rose’s claim was not simply provocative; it also invited literary critics to presume grounds previously ceded to children were rightfully theirs. But many—laypeople and scholars alike—continue to believe that children’s literature is for children. If that is the case, arguably, it must be simple, transparent, and hardly worthy of analysis, which is to say, might children’s literature criticism itself be “impossible”? 3

Although clearly the growing body of sophisticated children’s literature criticism belies these assumptions, a scholar new to the field might understandably suspect that there is very little to know in order to read children’s books critically or that this expertise ought to be easy to come by. Conversely, of course, he or she might find a children’s book’s apparent simplicity—or perhaps its unexpected complexity—baffling: how, and where, to begin approaching the children’s text? We believe that if he or she is willing to leave preconceptions and prejudices about the complexity and literary value of children’s literature behind, in reading children’s literature critically a scholar new to the field is likely to discover unexpected richness in both children’s literature itself and in the range of scholarship that addresses, analyzes, or incorporates it. Certainly, we hope that the Oxford Handbook of Children’s Literature will help address the needs of this beginning scholar—as well as the interests of those well established in the field.

Thinking about the unexpected pleasures—and risks—taken when adults read and analyze children’s literature, that is, when adults presume a higher order of expertise over a body of literature that has been codified (by design or by adoption) as “children’s,” one of this book’s editors is reminded of a time she was seated in an airplane next to a child traveling alone. She tried to make small talk with him—to make him more comfortable (so she imagined). After looking up several times from his book to answer her questions, he finally said, with exasperation, “This is the brand new Harry Potter book, which I waited a long time to get, and I really just want to focus on reading it now. I hope you don’t mind.” Chastened, the adult so-called expert in children’s literature was reminded not only of how easy it is to make assumptions about what children need but also of that almost holy bond that can be formed between child and book. In reading children’s books critically, as many of the essays included in this handbook remind us, it is important to acknowledge the phantom child—implied, addressed, represented, assumed—always lurking, though perhaps never quite possible (as Rose would say). Although our interest in creating the Oxford Handbook of Children’s Literature is scholarly rather than sentimental, anyone interested in exploring children’s literature confronts the haunting presence of childhood and the child reader within every text written for or adopted by children.

We begin the discussion that follows by outlining this book’s purposes and organization, and then we briefly review some of the field’s history and highlight a number of key principles and important scholarly works. Finally, we turn to important issues related to four general rubrics under which we have grouped the essays that follow. These rubrics, which serve as the structuring apparatus for the book, emerged organically from the essays and point to key areas of inquiry in children’s literature study: Adults and Children’s Literature; Pictures and Poetics; Reading History/Learning Race and Class; and Innocence and Agency. Our discussion of these categories is designed not simply to introduce the essays that are grouped under each of these rubrics (chronologically within each thematic section) but also to situate the issues they raise within scholarship and literary history.

Organizing Principles: Canons, Contexts, and Classrooms

This handbook attempts to reveal the possibilities of children’s literature criticism. In creating it we avoided replicating existing reference works that survey the various genres in children’s literature, offer national literary histories, or define important terminology. 4 Our goal was to create an interdisciplinary book that uses literary texts to introduce theoretical, methodological, and critical approaches, as well historical, political, and sociological themes. This makes the book valuable both to those wishing to gain a basic introduction to the field and to scholars seeking clear models of interdisciplinary approaches that have been enriching the field. The essays address a representative sampling of texts, in various genres, from the colonial era to the present, and from Britain, the United States, and Canada, that regularly appear (or arguably ought to appear) on syllabi of children’s literature or childhood studies courses. The contributors provided headnotes that introduce the individual authors discussed, as well as lists of further reading that point readers toward the broader implications of each essay. Taken together, all of these features make the handbook a practical companion for graduate and undergraduate courses in which literary texts themselves (not abstract theoretical paradigms, generic formulas, or historical rubrics) are the focus of study.

The essays collected here serve less to demarcate the field of children’s literature than to push at the generic and gatekeeping boundaries that cordon off (and can marginalize) “children’s literature” as a field of study. By introducing works that may not immediately spring to mind as “literature”—including film, children’s writing, comics, and musical recordings—but that belong to children’s culture more generally, we hope to expose all of the messy possibilities of children’s literature scholarship and encourage readers to go beyond this handbook and make connections between children’s literature and other cultural arenas.

As scholars who came to children’s literature from different disciplines—Lynne Vallone from literary studies and childhood studies and Julia Mickenberg from American studies with training in cultural history—in approaching our task as editors, we have tried to make our disciplinary differences a virtue. These disciplinary differences affected how we initially sought to shape the volume, our choices about scholars whose work we hoped to include, and the topics we wanted to cover; they also had an effect upon what we brought to the editing process itself, in the sense that each of us encouraged contributors to think expansively and in interdisciplinary ways.

We approached some of the top scholars of children’s literature to become contributors, also stretching the boundaries of the children’s literature field to bring it into dialogue with exciting work being done in the broader area of childhood studies, a burgeoning interdisciplinary arena that incorporates work related to children and childhood from history, media studies, anthropology, sociology, psychology, legal studies, politics, literature, and other disciplines. Instead of giving contributors a predictable assignment typical of many reference works, for example, to characterize a genre (the school story; fantasy; primers) or a critical approach (feminist, Marxist, postcolonial), we let our contributors propose “wish lists” of accessible, in-print texts from the Anglo-American tradition that they felt were particularly “teachable” and flexible and that, if not readily classifiable as canonical, rightly deserved a place within the canon. We felt that if scholars were encouraged to write about a work about which they felt passionate, then exciting and perhaps unpredictable—in the best sense—scholarship would ensue, scholarship that organically addresses many of the forms, approaches, and issues that in a traditional handbook format might be explicated in a more mechanical fashion. What emerged confirms the value of our unconventional approach: a book of original, innovative essays that use individual texts of various genres, historical eras, and national traditions to model critical approaches to reading and analyzing children’s literature or to explore historical and/or sociological themes.

This book was constructed with the notion of “canonical” children’s literature as a guiding principle but also as something contributors should actively call into question. In asking contributors to choose a “canonical” text as the centerpiece of their essays, from which they could address larger issues and showcase various theoretical frameworks or methodological approaches, we operated on the assumption that canonical works—especially those that are taught at the college level and also assigned in primary schools—are thought to embody qualities worth preserving and/or attitudes worth refuting. As such, these texts may be particularly revealing of the culture from which they emerged, especially in terms of how childhood is constructed. But we also asked our contributors to think about neglected texts that were popular in their time, retain a following, or can be said to be worthy of inclusion in a canon.

Although many of the children’s works considered in the following essays are widely accepted as canonical— Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland , Tom Sawyer , and Peter Pan , for example—not all of the texts discussed continue to be “works for children” anymore: some are too far removed from the lives of contemporary children (the Evangelical best-seller Froggy’s Little Brother ) or have long ago fallen out of classroom use (the New England Primer ). However, each of the works discussed in the handbook—whether novel, film, comic strip, picture book, poem, memoir, primer, or play—may lay claim to the status of the “classic” or deserve to be placed there. Certainly, one person’s “classic” might be another’s “trash,”yet we felt that a classic children’s book should be in print or readily available and embody qualities that had at one time communicated something essential to an understanding of childhood of a certain era.

Deborah Stevenson clarifies the qualities of a children’s literature classic in this way: “a text need not be popular with a multitude of contemporary children in order to be a classic. It must, however, speak of childhood, not just of literature, to adults” (119). Some of the works analyzed in this handbook may be considered to have recently achieved “classic” status in the canon of children’s literature—Charles Schulz’s Peanuts cartoons, Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry by Mildred Taylor, or the Frog and Toad books—and others may be classified as “classics-in-the-making” (the Harry Potter books or Gene Luen Yang’s award-winning graphic novel, American Born Chinese ). While the Oxford Handbook of Children’s Literature does not attempt to create a canon of children’s literature, it engages with many of the same questions of value, significance, and boundaries.

History and Approaches to Children’s Literature

Children’s literature has come rather late to the canon-formation game; it was not thought important enough to be included in the “high stakes” canon wars of the 1980s. Children’s literature first began to be recognized as a specialty in some university English departments in the 1980s and 1990s; previously it tended to be taught only in schools with strong elementary education programs or in library schools. Anthologies of national literatures (e.g., The Norton Anthology of American Literature ) still mostly ignore children’s literature. If they do include works such as Little Women or The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn , these stories, as Beverly Lyon Clark has discussed in Kiddie Lit: The Cultural Construction of Children’s Literature in America (2003), are no longer labeled “children’s literature,” for the term is still often viewed as something of an oxymoron in the context of Great Books. Even when children’s literature is recognized within literary history it is often classed as a genre in and of itself: the forthcoming Cambridge History of the American Novel , for instance, has a single chapter on “the children’s novel,” even as it recognizes the generic diversity of novels for adults.

Although only recently has this study begun to earn serious recognition within the academy, the critical study of children’s literature has a well-established history. Scholarly works on children’s literature began to appear in the early to mid-twentieth century, in works such as F.J. Harvey Darton’s Children’s Books in England: Five Centuries of Social Life (1932) and Paul Hazard’s Books, Children, and Men (published originally in French in 1944), which sought to place children’s literature within a larger cultural context. Within literary studies, the study of children’s literature gained a significant foothold in the 1970s: the British journal Signal was established in 1970; the U.S. journal Children’s Literature was established in 1972; and the Children’s Literature Association was formed in 1973, holding an annual conference beginning the following year and promoting scholarship in the field. And numerous colleges and universities developed programs in children’s literature study, based in English departments, library schools, and schools of education. Foundational works published since the late 1970s have shaped the field in important ways, helping define its contours and unique qualities, 5 bringing theoretical perspectives to bear, 6 creating essential historical overviews, 7 highlighting the intersection between ideologies and politics, 8 opening the canon of nineteenth-century literature (and other time periods) to include works for children, 9 and attending to the child reader/writer. 10

Beyond its academic history, children’s literature has developed in conjunction with a long tradition of critical evaluation that followed the development of children’s book publishing itself. Experts in the field have offered advice on what books to give to children since the late eighteenth century (see, for example, Sarah Trimmer’s The Guardian of Education and Charlotte Yonge’s influential three-part essay in Macmillan’s Magazine , “Children’s Literature of the Last Century”). “Treasuries” of children’s stories and popular anthologies have appeared in Britain and the United States since the late eighteenth century as well. 11 With the advent of library services to children in the late nineteenth century—special reading rooms for the young, staffed by librarians (most of them among a new cadre of college-educated women) trained to select books for children—new standards of quality in the field developed. Librarians, booksellers, and critics began to publish regular lists of recommended children’s books ( Booklist , for example, began publication in 1905, and The Horn Book , devoted to the critical evaluation of children’s books and scholarship in the field, first appeared in the United States in 1924). Macmillan established the first juvenile division in a U.S. publishing house in 1919, and most other publishers followed suit within the following two decades, continuing the field’s professionalization. In Britain, which had a long legacy of children’s book publishing going back to the printer John Newbery, the Puffin imprint of Penguin published its first children’s books in 1940, thus inaugurating an Anglo-American tradition of high-quality but affordable children’s books that would be continued in the United States with Little Golden Books.

Author and illustrator awards for children’s books have grown in number and prestige in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada and have contributed to the process of canon formation in the field. Awards include the Newbery Medal (est. 1922) and the Caldecott Medal (est. 1937) in the United States and the British Carnegie Medal (est. 1937) and Kate Greenaway Medal (est. 1955). In Canada, the Governor General’s Literary Award for Children’s Literature and Illustrators was established in 1937. Peter Hunt’s Children’s Literature: An Anthology 1801-1902 (2000) and the comprehensive Norton Anthology of Children’s Literature (2005) point to the fact that children’s literature, while perhaps not integrated within a larger literary canon, has certainly developed a canon of its own, a point that returns us to the essays in this volume, which are organized under the general rubrics discussed below. 12

Adults and Children’s Literature