A Guide to Lyric Essay Writing: 4 Evocative Essays and Prompts to Learn From

Poets can learn a lot from blurring genres. Whether getting inspiration from fiction proves effective in building characters or song-writing provides a musical tone, poetry intersects with a broader literary landscape. This shines through especially in lyric essays, a form that has inspired articles from the Poetry Foundation and Purdue Writing Lab , as well as become the concept for a 2015 anthology titled We Might as Well Call it the Lyric Essay.

Put simply, the lyric essay is a hybrid, creative nonfiction form that combines the rich figurative language of poetry with the longer-form analysis and narrative of essay or memoir. Oftentimes, it emerges as a way to explore a big-picture idea with both imagery and rigor. These four examples provide an introduction to the writing style, as well as spotlight tips for creating your own.

1. Draft a “braided essay,” like Michelle Zauner in this excerpt from Crying in H Mart .

Before Crying in H Mart became a bestselling memoir, Michelle Zauner—a writer and frontwoman of the band Japanese Breakfast—published an essay of the same name in The New Yorker . It opens with the fascinating and emotional sentence, “Ever since my mom died, I cry in H Mart.” This first line not only immediately propels the reader into Zauner’s grief, but it also reveals an example of the popular “braided essay” technique, which weaves together two distinct but somehow related experiences.

Throughout the work, Zauner establishes a parallel between her and her mother’s relationship and traditional Korean food. “You’ll likely find me crying by the banchan refrigerators, remembering the taste of my mom’s soy-sauce eggs and cold radish soup,” Zauner writes, illuminating the deeply personal and mystifying experience of grieving through direct, sensory imagery.

2. Experiment with nonfiction forms , like Hadara Bar-Nadav in “ Selections from Babyland . ”

Lyric essays blend poetic qualities and nonfiction qualities. Hadara Bar-Nadav illustrates this experimental nature in Selections from Babyland , a multi-part lyric essay that delves into experiences with infertility. Though Bar-Nadav’s writing throughout this piece showcases rhythmic anaphora—a definite poetic skill—it also plays with nonfiction forms not typically seen in poetry, including bullet points and a multiple-choice list.

For example, when recounting unsolicited advice from others, Bar-Nadav presents their dialogue in the following way:

I heard about this great _____________.

a. acupuncturist

b. chiropractor

d. shamanic healer

e. orthodontist ( can straighter teeth really make me pregnant ?)

This unexpected visual approach feels reminiscent of an article or quiz—both popular nonfiction forms—and adds dimension and white space to the lyric essay.

3. Travel through time , like Nina Boutsikaris in “ Some Sort of Union .”

Nina Boutsikaris is the author of I’m Trying to Tell You I’m Sorry: An Intimacy Triptych , and her work has also appeared in an anthology of the best flash nonfiction. Her essay “Some Sort of Union,” published in Hippocampus Magazine , was a finalist in the magazine’s Best Creative Nonfiction contest.

Since lyric essays are typically longer and more free verse than poems, they can be a way to address a larger idea or broader time period. Boutsikaris does this in “Some Sort of Union,” where the speaker drifts from an interaction with a romantic interest to her childhood.

“They were neighbors, the girl and the air force paramedic. She could have seen his front door from her high-rise window if her window faced west rather than east,” Boutsikaris describes. “When she first met him two weeks ago, she’d been wearing all white, buying a wedge of cheap brie at the corner market.”

In the very next paragraph, Boutskiras shifts this perspective and timeline, writing, “The girl’s mother had been angry with her when she was a child. She had needed something from the girl that the girl did not know how to give. Not the way her mother hoped she would.”

As this example reveals, examining different perspectives and timelines within a lyric essay can flesh out a broader understanding of who a character is.

4. Bring in research, history, and data, like Roxane Gay in “ What Fullness Is .”

Like any other form of writing, lyric essays benefit from in-depth research. And while journalistic or scientific details can sometimes throw off the concise ecosystem and syntax of a poem, the lyric essay has room for this sprawling information.

In “What Fullness Is,” award-winning writer Roxane Gay contextualizes her own ideas and experiences with weight loss surgery through the history and culture surrounding the procedure.

“The first weight-loss surgery was performed during the 10th century, on D. Sancho, the king of León, Spain,” Gay details. “He was so fat that he lost his throne, so he was taken to Córdoba, where a doctor sewed his lips shut. Only able to drink through a straw, the former king lost enough weight after a time to return home and reclaim his kingdom.”

“The notion that thinness—and the attempt to force the fat body toward a state of culturally mandated discipline—begets great rewards is centuries old.”

Researching and knowing this history empowers Gay to make a strong central point in her essay.

Bonus prompt: Choose one of the techniques above to emulate in your own take on the lyric essay. Happy writing!

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Good For a Laugh- How to Tap into Your Comedic Side in Your Writing

How to Start Your Own Poetry IG

6 Magnificent March 2024 Poetry Releases

An Introduction to the Lyric Essay

Rebecca Hussey

Rebecca holds a PhD in English and is a professor at Norwalk Community College in Connecticut. She teaches courses in composition, literature, and the arts. When she’s not reading or grading papers, she’s hanging out with her husband and son and/or riding her bike and/or buying books. She can't get enough of reading and writing about books, so she writes the bookish newsletter "Reading Indie," focusing on small press books and translations. Newsletter: Reading Indie Twitter: @ofbooksandbikes

View All posts by Rebecca Hussey

Essays come in a bewildering variety of shapes and forms: they can be the five paragraph essays you wrote in school — maybe for or against gun control or on symbolism in The Great Gatsby . Essays can be personal narratives or argumentative pieces that appear on blogs or as newspaper editorials. They can be funny takes on modern life or works of literary criticism. They can even be book-length instead of short. Essays can be so many things!

Perhaps you’ve heard the term “lyric essay” and are wondering what that means. I’m here to help.

What is the Lyric Essay?

A quick definition of the term “lyric essay” is that it’s a hybrid genre that combines essay and poetry. Lyric essays are prose, but written in a manner that might remind you of reading a poem.

Before we go any further, let me step back with some more definitions. If you want to know the difference between poetry and prose, it’s simply that in poetry the line breaks matter, and in prose they don’t. That’s it! So the lyric essay is prose, meaning where the line breaks fall doesn’t matter, but it has other similarities to what you find in poems.

Thank you for signing up! Keep an eye on your inbox. By signing up you agree to our terms of use

Lyric essays have what we call “poetic” prose. This kind of prose draws attention to its own use of language. Lyric essays set out to create certain effects with words, often, although not necessarily, aiming to create beauty. They are often condensed in the way poetry is, communicating depth and complexity in few words. Chances are, you will take your time reading them, to fully absorb what they are trying to say. They may be more suggestive than argumentative and communicate multiple meanings, maybe even contradictory ones.

Lyric essays often have lots of white space on their pages, as poems do. Sometimes they use the space of the page in creative ways, arranging chunks of text differently than regular paragraphs, or using only part of the page, for example. They sometimes include photos, drawings, documents, or other images to add to (or have some other relationship to) the meaning of the words.

Lyric essays can be about any subject. Often, they are memoiristic, but they don’t have to be. They can be philosophical or about nature or history or culture, or any combination of these things. What distinguishes them from other essays, which can also be about any subject, is their heightened attention to language. Also, they tend to deemphasize argument and carefully-researched explanations of the kind you find in expository essays . Lyric essays can argue and use research, but they are more likely to explore and suggest than explain and defend.

Now, you may be familiar with the term “ prose poem .” Even if you’re not, the term “prose poem” might sound exactly like what I’m describing here: a mix of poetry and prose. Prose poems are poetic pieces of writing without line breaks. So what is the difference between the lyric essay and the prose poem?

Honestly, I’m not sure. You could call some pieces of writing either term and both would be accurate. My sense, though, is that if you put prose and poetry on a continuum, with prose on one end and poetry on the other, and with prose poetry and the lyric essay somewhere in the middle, the prose poem would be closer to the poetry side and the lyric essay closer to the prose side.

Some pieces of writing just defy categorization, however. In the end, I think it’s best to call a work what the author wants it to be called, if it’s possible to determine what that is. If not, take your best guess.

Four Examples of the Lyric Essay

Below are some examples of my favorite lyric essays. The best way to learn about a genre is to read in it, after all, so consider giving one of these books a try!

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric by Claudia Rankine

Claudia Rankine’s book Citizen counts as a lyric essay, but I want to highlight her lesser-known 2004 work. In Don’t Let Me Be Lonely , Rankine explores isolation, depression, death, and violence from the perspective of post-9/11 America. It combines words and images, particularly television images, to ponder our relationship to media and culture. Rankine writes in short sections, surrounded by lots of white space, that are personal, meditative, beautiful, and achingly sad.

Calamities by Renee Gladman

Calamities is a collection of lyric essays exploring language, imagination, and the writing life. All of the pieces, up until the last 14, open with “I began the day…” and then describe what she is thinking and experiencing as a writer, teacher, thinker, and person in the world. Many of the essays are straightforward, while some become dreamlike and poetic. The last 14 essays are the “calamities” of the title. Together, the essays capture the artistic mind at work, processing experience and slowly turning it into writing.

The Self Unstable by Elisa Gabbert

The Self Unstable is a collection of short essays — or are they prose poems? — each about the length of a paragraph, one per page. Gabbert’s sentences read like aphorisms. They are short and declarative, and part of the fun of the book is thinking about how the ideas fit together. The essays are divided into sections with titles such as “The Self is Unstable: Humans & Other Animals” and “Enjoyment of Adversity: Love & Sex.” The book is sharp, surprising, and delightful.

Bluets by Maggie Nelson

Bluets is made up of short essayistic, poetic paragraphs, organized in a numbered list. Maggie Nelson’s subjects are many and include the color blue, in which she finds so much interest and meaning it will take your breath away. It’s also about suffering: she writes about a friend who became a quadriplegic after an accident, and she tells about her heartbreak after a difficult break-up. Bluets is meditative and philosophical, vulnerable and personal. It’s gorgeous, a book lovers of The Argonauts shouldn’t miss.

It’s probably no surprise that all of these books are published by small presses. Lyric essays are weird and genre-defying enough that the big publishers generally avoid them. This is just one more reason, among many, to read small presses!

If you’re looking for more essay recommendations, check out our list of 100 must-read essay collections and these 25 great essays you can read online for free .

You Might Also Like

TriQuarterly

Search form, sing, circle, leap: tracing the movements of the american lyric essay.

My journey into the expanse of the lyric essay began when I opened Maggie Nelson’s Bluets . At that time, I had been writing poetry for over ten years, exploring motherhood, mental health, and my Asian American heritage. I saw my work as lyric poetry that drew from the bloodlines of my first love, Sharon Olds, and her transformative poem, “Monarchs.”

Until Bluets , I had viewed the essay through the lens of my high school and undergraduate education: as a rigid box that enclosed a thesis supported by three or more paragraphs of argument sealed in by the packing tape of a conclusion. To me, there was no similarity between poetry’s lush landscape and the corrugated angles of prose.

But fifteen years after graduation from college, I sat on a worn chenille sofa in my living room with Bluets in my hands. I read Nelson’s first lines: “Suppose I were to begin by saying that I had fallen in love with a color. Suppose I were to speak this as though it were a confession . . .” The slim book fell from my fingers as a chord reverberated within me. My body knew that Nelson’s work was more than strict, formal prose. Within my marrow, Bluets sang and shifted; its music, undeniable. Why, when I read her prose, did my breath quicken, and my chest throb as if I was reading a poem? Where was Nelson’s thesis? Where were her essay’s harsh lines?

That was my introduction to the American lyric essay. A transmutable beast, the lyric essay roams a borderless landscape. I ride on its slick back, scanning the rolling hillsides. Prairie grass brushes against my thighs, sunlight ebbing in and out of towering clouds. The fragrance of honeysuckle weaves into the upturned earth’s musk. The lyric essay ambles and leaps, circling fields blue with cornflower.

In “Out of and Back into the Box: Redefining Essays and Options,” Melissa A. Goldthwaite explores the landscape of the essay. “The page,” she writes, “is an open field, not a box to fill with other box-like structures . . . There are few, if any, right angles in nature. I can think of no natural squares—just hills and uneven slopes, rounded flower petals, curved riverbank, beautifully twisted trees.” To Goldthwaite, the essay resides in many forms: “a tree, a glove, a fish, a fist, a container, an alternative, a poem, a story, and question.”

If an essay flows from form to form, how can it be contained? How can the lyric essay be defined? In my correspondence with Goldthwaite, she answered: there is always the desire to hem in prose, to categorize or label. Even the lyric essay can be “taught [or defined] in rigid ways.”

Perhaps my desire for a concrete answer stems from my training as a chemist and molecular biologist. In the laboratory, I titrated analytes to determine their concentration down to two decimal places. I swelled with satisfaction as I studied the immutable code for DNA strictly defined by the pairings of nucleic acids: adenine with thymine and guanine with cytosine. Though I left the scientific world nearly twenty years ago to become an artist and writer, the desire for precise measurements and definitions still lingers.

In my conversation with the poet Jos Charles, we ruminated on the question again: what is the lyric essay? Perhaps as Charles proposes, the definition of the lyric essay is a Western invention, one that readers try to impose on prose works. Am I trying to cram a mountain into the form of a dogwood blossom? When does the search for definitive truth end in the marring of beauty and wonder?

Werner Heisenberg, a leader in the field of quantum mechanics, proposed that it was impossible to pinpoint the precise location of an electron in space and also determine its momentum. From the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, the shapes of electron orbitals were born. These orbitals take the form of spheres or intricate petals extending from an atom’s nucleus, showing the possible position of an electron at any given time. Perhaps Heisenberg’s principle can be applied to the lyric essay, so that its essence resides in an approximate form, a form that shifts according to time and space.

The term “lyric essay” was introduced by Deborah Tall and John D’Agata in the Seneca Review in 1997. This “dense” and “shapely form,” write Tall and D’Agata, “straddles the essay and the lyric poem . . . forsak[ing] narrative line, discursive logic, and the art of persuasion in favor of idiosyncratic meditation.” In this way, the lyric essay “spirals in on itself, circling a single image or idea . . . [it] stalks its subject like quarry but is never content to merely explain or confess.”

In her 2007 essay, “Mending Wall,” Judith Kitchen writes that “the job of the lyric essayist is to find the prosody of fact, finger the emotional instrument, play the intuitive and the intrinsic, but all in service to the music of the real. Even if it’s an imagined actuality. The aim is to make of , not up .” The musical lyric essay is a “lyre, not a liar.”

I believe that the intent of the lyric essay has shifted since “Mending Wall.” Though the lyric essay still searches out truth, it has become more and more uncertain of what the truth is. Its emphasis has changed from navigating a singular truth to reflecting multiple truths.

Why has the lyric essay become more uncertain? It may be, as the essayist Aviya Kushner proposes, that the world itself has become exponentially complex, making it difficult to pinpoint universal truths. Perhaps, the lyric essay reflects humanity’s fragmentation, the exchange of ultimate truths for the truths of individual experiences.

Even the definition of the lyric essay is evasive, the essay’s meaning shifting over time and space. This is where the scientist in me struggles. I dislike this level of uncertainty. The lyric essay shifts under my gaze, glinting like a emerald’s countless facets. I fear that by searching to define the lyric essay, I will become lost within its prism. I feel my way through the dazzling light, the reverberating haze.

I must come to some form of conclusion. How can I speak about something that seems impossible to define? Perhaps, as Jos Charles ponders, the lyric essay evades definition because the lyric essay doesn’t exist as a form. Instead of a lyric essay, perhaps there is, as the scholars Virginia Jackson and Yopie Prins propose, a form of “lyric reading,” an agreement between the writer and reader. Perhaps the essay signals to the reader: Approach this piece lyrically. Once the reader enters this agreement, they succumb to the essay’s musicality, rhythm, leaps in logic, and fragmentation.

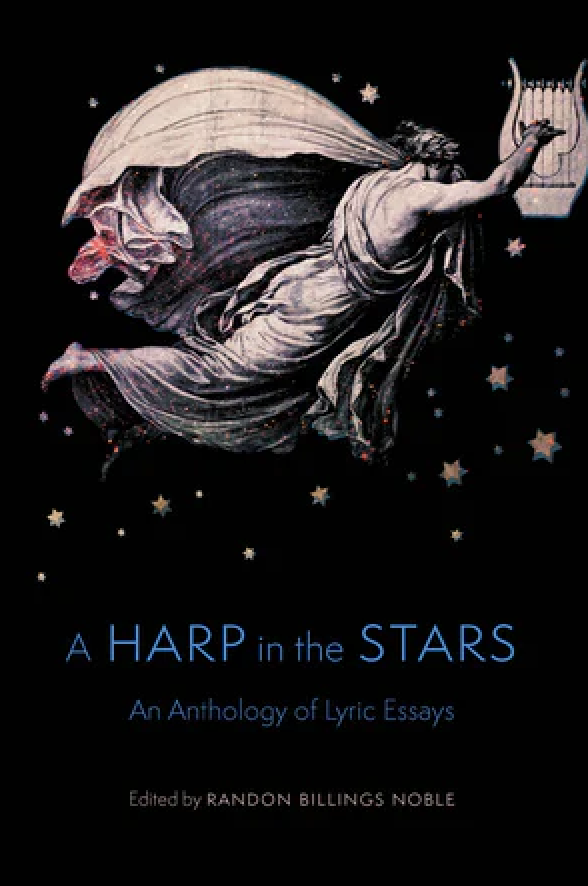

Though the lyric essay is a wild, changeable beast, attempts have been made to contain it. In the introduction to A Harp in the Stars: An Anthology of Lyric Essays , Randon Billings Noble attempts to outline the lyric essay. The lyric essay, she states, is “a piece of writing with a visible/stand-out/unusual structure that explores/forecasts/gestures to an idea in an unexpected way.” Noble then motions toward some of the current forms of the lyric essay, including the segmented essay, separated into sections through number, title, or white space and the braided essay, with its woven, repeated themes.

In my mind, a pattern emerges, an outline within the mist. Though difficult to define, the lyric essay contains elements that separate it from the rigid forms of my high school and undergraduate years. Unlike the traditional essay that is bound to a thesis, the lyric essay is a cloud of thought hovering around a question. However, as Noble writes, though the lyric essay is “slippery,” it must take on the responsibilities of an essay, “to try to figure something out, to play with ideas, to show a shift in thinking.” An essay, at its heart, is an exploration of truth, a straddling of black and white.

To me, the American lyric essay diverges from the traditional argument of the essay and its narrative counterpart, the personal essay, in three ways. Like a poem, the lyric essay might have honed rhythm and sound. It also diverges from narrative structures and instead revolves around themes. The lyric essay might also transition intuitively from concept to concept.

In this way, the lyric essay sings, circles, and leaps. These elements of the lyric essay can be explored through Lidia Yuknavitch’s Chronology of Water , Maggie Nelson’s Bluets , and Chet’la Sebree’s Field Study .

In her extended craft essay, The Art of Syntax , Ellen Bryant Voigt argues that syntax propels the musicality and rhythm of lyric poetry. The language spoken by “ordinary human beings” is elevated to poetry by the “echoes of more regular patterns of song.” By linking verse to “ordinary” spoken language, Voigt bridges the gap between poetry and prose. In this way, I believe, syntax plays the same role in lyric essay as it does in lyric poetry: it drives the musicality of language, thus propelling the essay from beginning to end.

Syntax can be described as the chunking of language in phrases, sentences, and paragraphs. Syntax, Voigt adds, is a “flexible calculus” that creates meaning. Within the lyric essay, syntax unfurls a sonic landscape of expansive rhythm and song.

As the psychologists and researchers Laura Batterink and Helen J. Neville state, the human brain navigates syntax “outside the window of conscious awareness.” Since the areas of the brain that process syntax are adjacent to those that process music, the reader instantaneously experiences the music of lyrical language.

Robert Frost writes that “the surest way to reach the heart [of the reader] is through the ear . . . By arrangement and choice of words on the part of the poet, the effects of humor, pathos, hysteria, and anger, and in fact all effects, can be indicated or obtained.” When the reader encounters the cloud of the lyric essay, they instantaneously experience its music, its murmuring, electrical hum. This is especially true in Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Chronology of Water , where syntax carries not only the rhythm and sound of her prose, but also its emotional intensity.

In her lyric essay collection, Yuknavitch navigates her chaotic childhood, her passion for swimming, and the power she summons through her transformation into a writer. In her first piece, “The Chronology of Water,” Yuknavitch harnesses the power of syntax. She writes: “The day my daughter was stillborn, after I held the future pink and rose-lipped in my shivering arms, lifeless tender, covering her face in tears and kisses, after they handed my dead girl to my sister who kissed her, then to my first husband who kissed her, then to my mother who could not bear to hold her, then out of the hospital room door, tiny lifeless swaddled thing, the nurse gave me tranquilizers and a soap and sponge.”

Here, Yuknavitch carries the reader through the birth of the speaker’s stillborn daughter through what Voigt refers to as “right-branching” syntax. In this form, phrases extend outward carried by similar language. In this passage, the grammatical chunks are separated by the preposition “after” and the conjunction “then.”

Using right-branching syntax, Yuknavitch describes the scene in which the speaker’s daughter is passed from her to her sister, husband, and mother, and then out of the hospital room. At the end of this extended sentence, the right-branching syntax halts. Yuknavitch crafts the sentence in waves: “after . . . after . . . then . . . then . . . then . . .” until the rhythm breaks on the rocks of the independent clause: “the nurse gave me tranquilizers and a soap and sponge.” The abrupt change in syntax silences the essay’s musicality. There isn’t a miraculous revival; with the passing of her daughter, the speaker is left with grief.

When Yuknavitch’s language carries me away, I must depart from the marching tradition of prose and drift into the lyrical. With her, all I hear is the water and the sounds of mourning. This is the mystic power of the lyric essay: it sweeps the reader up into its wave. The lyric essay becomes the reader, the reader becomes the song.

Frost writes that “a sentence is not interesting merely in conveying a meaning of words. It must do something more: it must convey a meaning by sound.” If the sentence can be seen as the poetic line, then syntax can work in two ways within prose: to complement the sentence’s flow or to be, as Voigt states, in “muscular opposition” to it.

Yuknavitch’s Chronology of Water shows both of these abilities of syntax. In her essay “How to Ride a Bike,” Yuknavitch navigates the harrowing experience of her father forcing her to ride a bike down a steep hill:

Wind on my face my palms sting my knees hurt pressing backwards speed and speedspeedspeedspeed holding my breath and my skin tingling like it does in trees terrible spiders crawling my skin like up high as the grand canyon my head too hot turnturnturnturnturn I am turning I am braking I can’t feel my feet I can’t feel my legs I can’t feel my arms I can’t feel my hands my heart my father’s voice yelling good girl my father running down the hill my father who did this who pushed me my eyes closing my limbs going limp my letting go me letting go so sleepy so light floating floating objects speed eyes closed violent hitting object crashing nothing.

Here, Yuknavitch has chosen to break each sentence like a poetic line. In doing so, she has created a section of text that reads like a prose poem. The section is void of punctation until Yuknavitch lands on the collision with the “nothing.” In the absence of punctation, syntax governs the rhythm of the lines. The right-branching syntax of the repeated phrases: “. . . my palms sting my knees hurt . . .” in the beginning of the section churns like the pedals of a bike.

The compressed segments, “speedspeedspeedspeed” and “turnturnturnturnturn” act as turns within the prose poem, where syntactical tension matches the increased tension of the narrative. What follows are two right-branching segments: “I am turning I am braking I can’t feel / my feet I can’t feel my legs I can’t feel my arms I can’t feel my / hands my heart . . .” Again, syntax complements the narrative movement. As a reader, I am carried by the syntax, experiencing the speaker’s panic as the world spins out of control.

Sometimes, syntax can be used to restrain the flow of the sentence. In this case, syntax is in “muscular opposition” to the narrative. In “Illness as Metaphor,” Yuknavitch describes the four-week period in which her eleven-year-old self was ill with mononucleosis. During this time, she was under the supervision of her abusive father. Yuknavitch writes:

In my sickbed my father removed my sweat soaked clothing. My father redressed me in underwear and pretty night- gowns. My father stroked my hair. Kissed my skin. My father carried me to the bathtub and laid me down and washed me. Everywhere. My father dried me off in his arms and redressed me and carried me back to the bed. His skin the smell of ciga- rettes and Old Spice cologne. His yellowed fingers. The mountainous callous on his middle finger from all the years of holding a pen or pencil. His steel blue eyes. Twinning mine. The word “Baby.”

The syntax of the sentences is uneven, alternating between right-branched strands, such as “My father redressed me in underwear and pretty nightgowns. My father stroked my hair,” and chunks of sentence fragments: “Kissed my skin.”

As a reader, I desire to race through this piercing and troubling description, but Yuknavitch holds me to the page. The syntax of this section restrains the flow of the narrative, challenging me to take in the details one after the other, to experience, as Yuknavitch did, every excruciating moment. As Yuknavitch writes: “It’s language that’s letting me say that the days elongated, as if the very sun and moon had forsaken me. It’s narrative that makes things open up so I can tell this. It’s the yielding expanse of a white page.” With a steady, skilled hand, Yuknavitch holds back the current of the narrative using syntax that suspends the reader within the pain and power of the moment.

In “Mending Wall,” Kitchen makes a distinction between a lyrical essay and its lyric counterpart. “Any essay can be lyrical,” she writes, “as long as it pays attention to the sound of its language or the sweep of its cadences . . . A lyric essay, however, functions as a lyric .” Like the lyric poem, the lyric essay “swallows you . . . until you reside inside it.” In other words, an essay isn’t a lyric just because of its musical language. Rather than creating a linear narrative, the lyric essay encompasses the reader by circling an image or theme.

In some personal essays, the engine is the story. In “Picturing the Personal Essay: A Visual Guide,” Tim Bascom provides pictorial representations of different forms of personal essay. Bascom describes the form, “narrative with a lift,” as a chronology with tension that “forces the reader into a climb.” Jo Anne Beard’s essay “The Fourth State of Matter” is an example of this form. Bascom describes Beard’s essay as “a sequence of scenes [that] matches roughly the unfolding real events, but [has] suspense [that] pulls us along, represented by questions we want answered.”

Bascom also contemplates essays that are a “whorl of reflection.” These essays are “more topical or reflective,” eschewing the linear movement of time for a circling of a topic. This circling occurs organically, “allow[ing] for a wider variety of perspectives—illuminating the subject from multiple angles.”

I believe that some lyric essays are formed as these whorls. Maggie Nelson’s Bluets is an example of elegant circling of image and theme. On the surface, Nelson’s long essay is the study of the color blue. The essay has 240 sections. Each section is interconnected with a focus on blue. “Each blue object,” Nelson muses, “could be a kind of burning bush, a secret code meant for a single agent, an X on a map too diffuse ever to be unfolded in entirety but that contains the knowable universe.”

Nelson finds blue in “shreds of blue garbage bags stuck in brambles,” a lapis lazuli tooth, the eyes of a martyred saint. Nelson also describes the absence of blue: “There is a color inside of the fucking, but it is not blue.” When others ask about Nelson’s fixation on the color, she responds: “We don’t get to choose what or whom we love . . . We just don’t get to choose.”

The image of blue swims within the pages of Bluets , flashing in and out of each condensed section. Nelson’s images are strong and visceral, but by themselves, they would be unable to hold my attention for the entire essay. Under the layered blue images is the theme of grief over the loss of an intimate relationship. Nelson introduces this theme early in the essay, in section 8: “‘We love to contemplate blue, not because it advances to us, but because it draws us after it,’ wrote Goethe, and perhaps he is right. But I am not interested in longing to live in a world in which I already live. I don’t want to yearn for blue things, and God forbid for any ‘blueness.’ Above all, I want to stop missing you.” Just as Nelson leans on blue, she had placed her faith in her intimate partner.

As the essay progresses, loss widens and deepens like a sea. Nelson writes: “We mainly suppose the experiential quality to be an intrinsic quality of the physical object—this is the so-called systemic illusion of color. Perhaps it is also that of love. But I am not willing to go there—not just yet. I believed in you.”

Nelson provides scant details of her romantic partner. In sections 67–70, Nelson explores the mating habits of the satin bowerbird. The males, Nelson writes, “can attract thirty-three females to fuck per season if they put on a good enough show,” while the female “mates only once [and] incubates the eggs alone.” These sections hint at a loneliness caused by abandonment. Though the cause of the end of the relationship isn’t revealed, Nelson exposes its aftermath: “It is easier, of course, to find dignity in one’s solitude. Loneliness is solitude with a problem. Can blue solve the problem, or can it at least keep me company within it?—No, not exactly. It cannot love me that way; it has no arms.”

Bascom writes that “whorl of reflection” essays are driven not by plot, but by the intoxicating pleasure of new perspectives and insights. This is especially true for Bluets. A whorl of contemplation, it’s a lazy river that loops for countless miles. Within it, I sometimes drift along with the images of blue and themes of grief and loneliness. Sometimes, I stand up and push against them. This tension between push and pull keeps me engaged in Bluets , within its circling of blue.

In “A Taxonomy of Nonfiction; or the Pleasures of Precision,” Karen Babine meditates on the “lyric mode” of the essay, which is driven by language, not narrative. Heidi Czerwiec states that “there are essays that are circuitous, nonlinear, that spiral around a central concept, incident or image, accruing meaning as they move. No forks, no false moves, no misdirection, only perhaps a pleasant disorientation as the writing twists and turns.” Though lyric essays are nonlinear, they still have centers that “hold.” Though Bluets isn’t driven by narrative, it circles around image and theme. In addition, there is an undergirding question that holds the essay in a state of tension: how will the speaker survive her grief? The answer is delivered in the one of the last sections of the essay:

For to wish to forget how much you loved someone—and then, to actually forget—can feel, at times like the slaughter of a beautiful bird who chose, by nothing short of grace, to make a habitat of our heart. I have heard that this pain can be converted, as it were, by accepting “the fundamental impermanence of all things.” This acceptance bewilders me: sometimes it seems an act of will; at others, of surrender. Often I feel myself to be rocking between them (seasickness).

As Nelson releases herself from the relationship, I also experience freedom and resurface from Bluets transformed.

Like a moth drawn to candlelight, I’m drawn back to exploring the form of the lyric essay. Through the haze of light refracted through dust and smoke, I seek its outline, first through the essay’s musical language and then through its circling of themes. In my conversation with the poet and essayist Chet’la Sebree, we discussed the “machinery” of the lyric essay. Lyric essays hinge on “having a poetic quality.” They are constructed like a poem, creating “sense and meaning” through associative leaps.

My discussion with Sebree makes me return to the work of Sharon Olds. It was within the pages of Satan Says that I encountered “Monarchs,” the poem that entranced me with images of creatures “floating / south to their transformation, crossing over / borders in the night, the diffuse blood-red / cloud of them . . .” Olds’s elegant line breaks allow her images to fluidly flow from one line to the next. Through these breaks, Olds also guides me through associative leaps, helping me connect the speaker to her first lover and the butterflies:

The hinged print of my blood on your thighs— a winged creature pinned there— and then you left, as you were to leave over and over, the butterflies moving in masses past my window . . .

Here, the intimacy is visceral. The speaker, lover, and monarchs are placed closely on the page so that my eye and mind make the connection between them.

Through reflecting on Sebree and Olds’s work, I came to believe that there is a link between poetry and the lyric essay when it comes to leaps of logic. Within both practices, syntax and white space help to guide readers over the gaps between images, thoughts, and themes.

During our time together, Sebree and I discussed her work with the lyric essay. As she wrote Field Study , Sebree asked herself: “How can [I] make an individual thought beautiful?” To Sebree, each thought is an “isolated cube of language.” I believe that each “cube” is connected through the bridge of syntax. Syntax is “sonically driven” and allows the lyric essay to make “musical sense.”

In Field Study , Sebree shaped each of the lyric essay’s sections around sound and musicality. In one section, Sebree reflects on the Women’s March and its significance to white women and how she regards the march as a woman of color. Sebree’s discussion of the march extends over five paragraphs of varying length:

The Women’s March meant a lot to a lot of women in my life. By a lot of women in my life, I mean the 50% of my friends that are white. With them, I don’t have to differentiate between “women” and “white women” because When I say “women,” at least 53% of the time people—and by “people,” I mean “white people”—will assume I mean “white women.” These percentages are fake as fake news but this fact is not: white people see whiteness as universal. There is no appropriate antonym for those of us who are not.

The first two paragraphs consist of one sentence each. In the second paragraph, Sebree uses assonance to create a couplet of “life” and “white.” This paragraph is carefully arranged so that “life” and “white” are placed in close visual proximity. The syntax of the sentence facilitates this visual coupling by placing the shorter dependent clause before the longer independent clause.

Within Field Study , associative leaps follow couplets. In the case of the Women’s March section, I am primed by the couplets to expect a shift in focus from Sebree’s description of her friends to the exclusion of Black women from the definition of “women.” The couplet, “life” and “white,” provides the reader and speaker an opportunity to “come up for air” before a plunge into the difficult topic of erasure. Sebree writes: “white people see whiteness / as universal.”

In Field Study , Sebree also uses white space to facilitate associative leaps. After the section about the Women’s March, Sebree adds a quote from Claudia Rankine and Beth Loffreda:

To say this . . . is great because it transcends its particularity to say something “human” . . . is to reveal . . . the stance that people of color are not human, only achieve the human in certain circumstances.

Here, Sebree provides Rankine and Loffreda’s quote extra white space, their voices expanding within the essay’s visual and mental landscape. The white space helps the reader “meditate on the quote . . . [then] move back into [Sebree’s] language.”

In comparison, the Women’s March section that precedes Rankine and Loffreda’s quote is a larger block of text, leaving less space for the reader and meditation. As a reader, I can’t catch my breath and am immersed in Sebree’s thoughts about womanhood and racial exclusion. In this way, white space (or the lack of it) is a type of syntax. It acts as another way to group language and ideas.

Continuing the Journey

In the interview “John D’Agata Redefines the Essay,” D’Agata comments: “I like to think of the essay as an art form that tracks the evolution of consciousness as it rolls over the folds of a new idea, memory, or emotion. What I’ve always appreciated about the essay is the feeling that it gives me that it’s capturing the activity of human thought in real time.”

In this way, the lyric essay reflects the changing landscape of truth. Through this realization, the scientist in me has come to a place of acceptance—an acceptance of a truth not bound by rigid facts, but cradled in a cloud of shifting time and space. By capturing a moment of contemplation, the lyric essay captures the movement of the human spirit. This is the lyric essay’s gift to the world.

Like Heisenberg’s electron, the lyric essay roams a landscape of beauty and uncertainty. In the future, the lyric essay may transform into a beast that is unrecognizable to me in voice and motion. I will continue to revel in its wildness, a splendor that I cannot tame.

Issue 164 Summer/Fall 2023

Previous: , next: , share triquarterly, about the author, sayuri matsuura ayers.

Sayuri Ayers is an essayist and poet from Columbus, Ohio. Her work has appeared on The Poetry Foundation website and in Gulf Stream Magazine , Hippocampus Magazine , CALYX , and Parentheses Journal . She is the author of two collections of poetry, Radish Legs, Duck Feet (Green Bottle Press) and Mother/Wound (Full/Crescent Press) and two forthcoming collections, The Maiden in the Moon and The Woman , The River , from Porkbelly Press. A Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net nominee, Sayuri has been supported by Kundiman, the Virginian Center for Creative Arts, The Greater Columbus Arts Council, and the Ohio Arts Council. To learn more, visit sayuriayers.com .

The Latest Word

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Lyric Essays

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

These resources discuss some terms and techniques that are useful to the beginning and intermediate creative nonfiction writer, and to instructors who are teaching creative nonfiction at these levels. The distinction between beginning and intermediate writing is provided for both students and instructors, and numerous sources are listed for more information about creative nonfiction tools and how to use them. A sample assignment sheet is also provided for instructors.

Because the lyric essay is a new, hybrid form that combines poetry with essay, this form should be taught only at the intermediate to advanced levels. Even professional essayists aren’t certain about what constitutes a lyric essay, and lyric essays disagree about what makes up the form. For example, some of the “lyric essays” in magazines like The Seneca Review have been selected for the Best American Poetry series, even though the “poems” were initially published as lyric essays.

A good way to teach the lyric essay is in conjunction with poetry (see the Purdue OWL's resource on teaching Poetry in Writing Courses ). After students learn the basics of poetry, they may be prepared to learn the lyric essay. Lyric essays are generally shorter than other essay forms, and focus more on language itself, rather than storyline. Contemporary author Sherman Alexie has written lyric essays, and to provide an example of this form, we provide an excerpt from his Captivity :

"He (my captor) gave me a biscuit, which I put in my

pocket, and not daring to eat it, buried it under a log, fear-

ing he had put something in it to make me love him.

FROM THE NARRATIVE OF MRS. MARY ROWLANDSON,

WHO WAS TAKEN CAPTIVE WHEN THE WAMPANOAG

DESTROYED LANCASTER, MASSACHUSETS, IN 1676"

"I remember your name, Mary Rowlandson. I think of you now, how necessary you have become. Can you hear me, telling this story within uneasy boundaries, changing you into a woman leaning against a wall beneath a HANDICAPPED PARKING ONLY sign, arrow pointing down directly at you? Nothing changes, neither of us knows exactly where to stand and measure the beginning of our lives. Was it 1676 or 1976 or 1776 or yesterday when the Indian held you tight in his dark arms and promised you nothing but the sound of his voice?"

Alexie provides no straightforward narrative here, as in a personal essay; in fact, each numbered section is only loosely related to the others. Alexie doesn’t look into his past, as memoirists do. Rather, his lyric essay is a response to a quote he found, and which he uses as an epigraph to his essay.

Though the narrator’s voice seems to be speaking from the present, and addressing a woman who lived centuries ago, we can’t be certain that the narrator’s voice is Alexie’s voice. Is Alexie creating a narrator or persona to ask these questions? The concept and the way it’s delivered is similar to poetry. Poets often use epigraphs to write poems. The difference is that Alexie uses prose language to explore what this epigraph means to him.

Course Syllabus

Writing the Lyric Essay: When Poetry & Nonfiction Play

Experiment with form and explore the possibilities of this flexible genre..

Some of the most artful work being done in essay today exists in a liminal space that touches on the poetic. In this course, you will read and write lyric essays (pieces of creative nonfiction that move in ways often associated with poetry) using techniques such as juxtaposition; collage; white space; attention to sound; and loose, associative thinking. You will read lyric essays that experiment with form and genre in a variety of ways (such as the hermit crab essay, the braided essay, multimedia work), as well as hybrid pieces by authors working very much at the intersection of essay and poetry. We will proceed in this course with an attitude of play, openness, and communal exploration into the possibilities of the lyric essay, reaching for our own definitions and methods, even as we study the work of others for models and inspiration. Whether you are an aspiring essayist interested in infusing your work with fresh new possibilities, or a poet who wants to try essay, this course will have room for you to experiment and play.

How it works:

Each week provides:

- discussions of assigned readings and other general writing topics with peers and the instructor

- written lectures and a selection of readings

Some weeks also include:

- the opportunity to submit two essays of 1000 and 2500 words each for instructor and/or peer review

- additional optional writing exercises

- an optional video conference that is open to all students(and which will be available afterward as a recording for those who cannot participate)

Aside from the live conference, there is no need to be online at any particular time of day. To create a better classroom experience for all, you are expected to participate weekly in class discussions to receive instructor feedback.

Week 1: Lyric Models: Space and Collage

In this first week, we’ll consider definitions and models for the lyric essay. You will read contemporary pieces that straddle the line between personal essay and poem, including work by Toi Derricotte, Anne Carson, and Maggie Nelson. In exercises, you will explore collage and the use of white space.

Week 2: Experiments with Form: Braided Essay and Hermit Crab Essay

We will build on our discussion of collage and white space, looking at examples of the braided essay. We’ll also examine the hermit crab essay, in which writers “sneak” personal essays into other forms, such as a job letter, shopping list, or how-to manual. You’ll experiment with your own braided pieces and hermit crab pieces and turn in the first assignment.

Week 3: Lyric Vignette and the Prose Poem

Prose poems will often capture emotional truths using juxtaposition, hyperbole, and absurd or surreal leaps of logic. This week, we’ll investigate how lyrical vignettes can stay true to actual events while employing some of the lyrical, dreamlike, and/or absurd qualities of the prose poem to communicate the wonder and mystery of life.

Week 4: Witnessing the Self: Essays by Poets

Poet Larry Levis has written of the poet as witness, as temporarily emptied of personality but simultaneously connected to a self, a “gazer.” Personal essays by poets retain something of this quality. Examining essays by poets such as Ross Gay, Lucia Perillo, Amy Gerstler, and Elizabeth Bishop, we’ll look at moments of connection and disconnection. Guided exercises will help you find and craft your own such moments.

Week 5: Hybrid Forms and the Documentary Impulse

As we wrap up the course, we will continue investigating the possibilities inherent in straddling and combining genres as we explore multimedia work, as well as work in the “documentary poetics” vein. We will look to writers like Claudia Rankine and Bernadette Mayer, Roz Chast and Maira Kalman for models of what is possible creatively when we observe ourselves as social beings moving through time, collecting text, images, and observations. Students will also turn in a final essay.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

What’s Missing Here? A Fragmentary, Lyric Essay About Fragmentary, Lyric Essays

Julie marie wade on the mode that never quite feels finished.

“Perhaps the lyric essay is an occasion to take what we typically set aside between parentheses and liberate that content—a chance to reevaluate what a text is actually about. Peripherals as centerpieces. Tangents as main roads.”

Did I say this aloud, perched at the head of the seminar table? We like to pretend there is no head in postmodern academia—decentralized authority and all—but of course there is. Plenty of (symbolic) decapitations, too. The head is the end of the table closest to the board—where the markers live now, where the chalk used to live: closest seat to the site of public inscription, closest seat to the door.

But I might have said this standing alone, in front of the bathroom mirror—pretending my students were there, perched on the dingy white shelves behind the glass: some with bristles like a new toothbrush, some with tablets like the contents of an old prescription bottle. Everything is multivalent now.

(Regardless: I talk to my students in my head, even when I am not sitting at the head of the table.)

“Or perhaps the entire lyric essay should be placed between parentheses,” I say. “Parentheses as the new seams—emphasis on letting them show.”

Once a student asked me if I had ever considered the lyric essay as a kind of transcendental experience. “Like how, you know, transcendentalism is all about going beyond the given or the status quo. And the lyric essay does that, right? It goes beyond poetry in one way, and it goes beyond prose in another. It’s kind of mystical, right?”

There is no way to calculate—no equation to illustrate—how often my students instruct and delight me. HashtagHoratianPlatitude. HashtagDelectandoPariterqueMonendo.

“Like this?” I asked, with a quick sketch in my composition book:

“I don’t know, man. I don’t think of math as very mystical,” the student said, leaning—not slumping—as only a young sage can.

“But you are saying the lyric essay can raise other genres to a higher power, right?”

Horace would have dug this moment: our elective humanities class spilling from the designated science building. Late afternoon light through a lattice of wisp-white clouds. In the periphery: Lone iguana lumbering across the lawn. Lone kayak slicing through the brackish water. Some native trees cozying up to some non-native trees, their roots inevitably commingling. Hybrids everywhere, as far as the eye could see, and then beyond that, ad infinitum .

You’ll never guess what happened next: My student high-fived me—like this was 1985, not 2015; like we were players on the same team (and weren’t we, after all?)—set & spike, pass & dunk, instruct & delight.

“Right!” A memory can only fade or flourish. That palm-slap echoes in perpetuity.

“The hardest thing you may ever do in your literary life is to write a lyric essay—that feels finished to you; that you’re comfortable sharing with others; that you’re confident should be called a lyric essay at all.”

“Is this supposed to be a pep talk?” Bless the skeptics, for they shall inherit the class.

I raise my hand in the universal symbol for wait. In this moment, I remember how the same word signifies both wait and hope in Spanish. ( Esperar .) I want my students to do both, simultaneously.

“Hear me out. If you make this attempt, humbly and honestly and with your whole heart, the next hardest thing you may ever do in your literary life is to stop writing lyric essays.”

My hand is still poised in the wait position, which is identical, I realize, to the stop position. Yet wait and stop are not true synonyms, are they? And hope and stop are verging on antonyms, aren’t they? (Body language may be the most inscrutable language of all.)

“So you think lyric essays are addictive or something?” Bless the skeptics—bless them again—for they shall inherit the page.

“Hmm … generative, let’s say. The desire to write lyric essays seems to multiply over time. We continue to surprise ourselves when we write them, and then paradoxically, we come to expect to be surprised.”

( Esperar also means “to expect”—doesn’t it?)

When I tell my students they will remember lines and images from their college workshops for many years—some, perhaps, for the rest of their lives—I’m not sure if they believe me. Here’s what I offer as proof:

In the city where I went to school, there were twenty-six parallel streets, each named with a single letter of the alphabet. I had walked down five of them at most. When I rode the bus, I never knew precisely where I was going or coming from. I didn’t have a car or a map or a phone, and GPS hadn’t been invented yet. In so many ways, I was porous as a sieve.

Our freshman year a girl named Rachel wrote a self-referential piece—we didn’t call them lyric essays yet, though it might have been—set at the intersection of “Division” and “I.”

How poetic! I thought. What a mind-puzzle—trying to imagine everything the self could be divisible by:

I / Parents I/ Religion I/ Scholarships I/ Work Study I/ Vocation I/ Desire

Months passed, maybe a year. One night I glanced out the window of my roommate’s car. We were idling at a stoplight on a street I didn’t recognize. When I looked up, I saw the slim green arrow of a sign: Division Avenue.

“It’s real,” I murmured.

“What do you mean?” Becky asked, fiddling with the radio.

I craned my neck for a glimpse of the cross street. It couldn’t be—and yet—it was!

“This is the corner of Division and I!”

“Just think about it—we’re at the intersection of Division and I!”

The light changed, and Becky flung the car into gear. There followed a pause long enough to qualify as a caesura. At last, she said, “Okay. I guess that is kinda cool.”

Here’s another: I remember how my friend Kara once described the dormer windows in an old house on Capitol Hill. She wrote that they were “wavy-gazy and made the world look sort of fucked.”

I didn’t know yet that you could hyphenate two adjectives to make a deluxe adjective—doubling the impact of the modifier, especially if the two hinged words were sonically resonant. (And “wavy-gazy,” well—that was straight-up assonant.)

Plus: I didn’t know that profanity was permissible in our writing, even sometimes apropos. At this time, I knew the meaning of the word apropos but didn’t even know how to spell it.

One day I would see apropos written down but not recognize it as the word I knew in context. I would pronounce it “a-PROP-ose,” then wonder if I had stumbled upon a typo.

Like many things, I don’t remember when I learned to connect the spelling of apropos with its meaning, or when I learned per se was not “per say,” or when I realized I sometimes I thought of Kara and Becky and Rachel when I should have been thinking about my boyfriend—even sometimes when I was with my boyfriend. (He was majoring in English, too, but I found his diction far less memorable overall.)

“The lyric essay is not thesis-driven. It’s not about making an argument or defending a claim. You’re writing to discover what you want to say or why you feel a certain way about something. If you’re bothered or beguiled or in a state of mixed emotion, and the reason for your feelings doesn’t seem entirely clear, the lyric essay is an opportunity to probe that uncertain place and see what it yields.”

Sometimes they are undergrads, twenty bodies at separate desks, all facing forward while I stand backlit by the shiny white board. Sometimes they are grad students, only twelve, clustered around the seminar table while I sit at the undisputed, if understated, head. It doesn’t matter the composition of the room or the experience of the writers therein. This part I say to everyone, every term, and often more than once. My students will all need a lot of reminding, just as I do.

(A Post-it note on my desk shows an empty set. Outside it lurks the question—“What’s missing here?”—posed in my smallest script.)

“Most writing asks you to be vigilant in your noticing. Pay attention is the creative writer’s credo. We jot down observations, importing concrete nouns from the external world. We eavesdrop to perfect our understanding of dialogue, the natural rhythms of speech. Smells, tastes, textures—we understand it’s our calling to attend to them all. But the lyric essay asks you to do something even harder than noticing what’s there. The lyric essay asks you to notice what isn’t.”

I went to dances and dried my corsages. I kept letters from boys who liked me and took the time to write. Later, I wore a locket with a picture of a man inside. (I believe they call this confirmation bias .) The locket was shaped like a heart. It tarnished easily, which only tightened my resolve to keep it clean and bright. I may still have it somewhere. My heart was full, not empty, you see. I was responsive to touch. (We always held hands.) I was thoughtful and playful, attentive and kind. I listened when he confided. I laughed at his jokes. We kissed in public and more than kissed in private. (I wasn’t a tease.) When I cried at the sad parts in movies, he always wrapped his arm around. For years, I saved everything down to the stubs, but even the stubs couldn’t save me from what I couldn’t say.

“Subtract what you know from a text, and there you have the subtext.” Or—as my mother used to say, her palms splayed wide— Voilà!

I am stunned as I recall that I spoke French as a child. My mother was fluent. She taught me the French words alongside the English words, and I pictured them like two parallel ladders of language I could climb.

Sometimes in the grocery store, we would speak only French to each other, to the astonishment of everyone around. It was our little game. We enjoyed being surprising, but the subtext was being impressive or even perhaps being exclusionary. That’s what we really enjoyed.

When Dee, the woman in the blue apron with the whitest hair I had ever seen—a shock of white, for not a trace of color remained—smiled at us in the Albertson’s checkout line, I curtsied the way my ballet teacher taught me, clasped the bag in my small hand, and murmured Merci . My good manners were not lost in translation.

“Lyric essays are often investigations of the Underneath—what only seems invisible because it must be excavated, brought to light. We cannot, however, take this light-bringing lightly.”

When I was ten years old, my parents told me they were going to dig up our backyard and replace the long green lawn with a swimming pool. This had always been my mother’s dream, even in Seattle. She assumed it was everyone else’s dream, too, even in Seattle. Bulldozers came. The lilac bushes at the side of the house were uprooted and later replanted. Portions of the fence were taken down and later rebuilt. It took a long time to dig such a deep hole. Neighbors complained about the noise. Someone came one night and slashed the bulldozer’s tires. (Another slow-down. Another set-back.) All year we lived in ruins.

Eventually, the hole was finished, the dirt covered over with a smooth white surface. I remember when the workmen said I could walk into the pool if I wanted—there was no water yet, just empty space, more walled emptiness than I had ever encountered before. In my sneakers with the cat at my heels, I traipsed down the steps into the shallow end, then descended the gradual hill toward the deep end. There I stood at the would-be bottom, where the water would someday soon cover my head by a four full feet. When I looked up, the sky seemed so much further away. The cat laid down on the drain, which must have been warmed by the sun.

I didn’t know about lyric essays then, but I often think about the view from the empty deep end of the dry swimming pool when I talk about lyric essays now. The space felt strange and somehow dangerous, yet there was also an undeniable allure. I tell my students it’s hard work plumbing what’s under the surface. We don’t always know what we’ll find.

That day in the pool, I looked up and saw a ladder dangling from the right-side wall. It was so high I couldn’t reach it, even if I stretched my arms. I would need water to buoy me even to the bottom rung. For symmetry, I thought, there should have been a second ladder on the left-side wall. And that’s when I remembered, suddenly, with a shock as white as Dee’s hair: I couldn’t recall a word of French anymore! I had lost my second ladder. When did this happen? I licked my dry lips. I tried to wet my parched mouth. How did this happen? There I was, standing inside a literal absence, noticing that a whole language had vanished from my sight, my ear, my grasp.

I live in Florida now. I have for seven years. In fact, I moved to Florida to teach the lyric essay, audacious as that sounds, but hear me out. I think “lyric essay” is the name we give to something that resists being named. It’s the placeholder for an ultimately unsayable thing.

After ten years of teaching many literatures—some of which approached the threshold of the lyric essay but none of which passed through—I came to Florida to pursue this layered, voluminous, irreducible thing. I came to Florida to soak in it.

“That’s a sub-genre of creative nonfiction, right?” Is it ?

“You’re moving to the sub-tropics, aren’t you?” I am!

On the interview, my soon-to-be boss drove me around Miami for four full hours. The city itself is a layered, voluminous, irreducible thing. I love it irrationally and without hope of mastery, which in the end might be the only way to love anything.

My soon-to-be boss said, “We have found ourselves without a memoirist on the faculty.” I liked him instantly. I liked the word choice of “found ourselves without,” the sweet and the sad commingling.

He told me, “Students want to learn how to write about their lives, their experiences—not just casually but as an art form, with attention to craft.” (I nodded.) “But there’s another thing, too. They’re asking about—” and here he may have lowered his voice, with that blend of reverent hesitancy most suited to this subject—“ the lyrical essay. ” (I nodded again.) “So, you’re familiar with it, then?”

“Yes,” I smiled, “I am.”

Familiar was a good word, perhaps the best word, to describe my relationship with this kind of writing. The lyric essay and I are kin. I know the lyric essay in a way that feels as deep and intuitive, as troubling and unreasonable, as my own family ties have become.

“Can you give me some context for the lyrical essay?” he asked. At just this moment, we may have been standing on the sculpted grounds of the Biltmore Hotel. Or: We may have been traffic-jammed in the throbbing heart of Brickell. Or: We may have been crossing the spectacular causeway that rises then plunges onto Key Biscayne.

“Do you ever look at a word like, say, parenthesis , and suddenly you can’t stop seeing the parts of it?”

“How do you mean?” he asked.

“Like how there’s a parent there, in parenthesis , and how parentheses can sometimes seem like a timeout in the middle of a sentence—something a parent might sentence a child to?”

“Okay,” he said. He seemed to be mulling, which I took as a good sign.

“You see, a lyric essayist might notice something like that and then might use the nature of parentheses themselves to guide an exploration of a parent-child relationship.”

I wanted to say something brilliant, to win him over right then and there, so he would go back to the other creative writers and say, “It’s her ! We must hire her !”

But brilliance is hard to produce on command. I could only say what I thought I knew. “This is an approach to writing that seeks out the smallest door—sometimes a door found within words themselves—and uses that door to access the largest”—I may have said hardest —“rooms.”

I heard it then, the low rumble at the back of his throat: “Hmm.” And then again: “Hmm.”

Years before Overstock.com, people shopped at surplus stores—or at least my mother did, and my mother was the first people I knew. (She was only one, true, but she seemed like a multitude.)

The Sears Surplus Store in Burien, Washington, was a frequent destination of ours. Other Sears stores shipped their excess merchandise there, where it was piled high, rarely sorted, and left to the customers who were willing to rummage. So many bins to plunge into! So many shelves laden with re-taped boxes and dented cans! ( Excess seemed to include items missing pieces or found to be defective.) Orphaned socks. Shoes without laces. A shower nozzle Bubble-Wrapped with a hand-written tag— AS IS.

I liked the alliterative nature of the store’s name, but I did not like the store itself, which was grungy and stale, a trial for the senses. There were unswept floors, patches of defiled carpet, sickly yellow lights that flickered and whined, and in the distance, always the sound of something breaking.

“We don’t even know what we’re looking for!” I’d grouse to my mother rather than rolling up my sleeves and pitching in. “There’s too much here already, and they just keep adding more and more.”

I see now my mother was my first role model for what it takes to make a lyric essay. The context was all wrong, but the meaning was right, precisely. She handed me her purse to hold, then wiped the sweat that pooled above her lip. “If you don’t learn how to be a good scavenger,” my mother grinned— oh, she was in her element then! —“how do you ever expect to find a worthy treasure?”

Facebook Post, February 19, 2016, 11:58 am:

Reading lyric essays at St. Thomas University this morning. In meaningless and/or profound statistics—also known as lyric math—the current priest-to-iguana ratio on campus is 6 to 2 in favor of the priests. Somehow, though, the iguanas are winning.

An aspiring writer comments: ♥ Lyric math ♥ I love your brain!

I reply: May your love of lyric essays likewise grow, exponentially! ♥

Growing up, like many kids who loved a class called language arts, I internalized a false binary (to visualize: an arbitrary wall) between what we call art and what we call science. “Yet here we are today,” I tell my students, palms splayed wide, “members of the College of Arts & Sciences. Notice it’s an ampersand that joins them, aligns them. Art and science playing together on the same team.”

When they share, my students report similar divisions in their own educational histories. They say they learned early on to separate activities for the “right brain” (creative) from activities for the “left brain” (analytical). When they prepared for different sections of their standardized tests, they almost always found the verbal questions “fun,” the quantitative questions “hard.”

“Must these two experiences be mutually exclusive?” I ask. “Because I’m here to tell you the lyric essay is the hardest fun you can have.” They laugh because they are beginning to believe me.

My students also learned early on to assign genders to their disciplines of study—“girl stuff” versus “boy stuff.” They recount how the girl stuff of spelling and sentence-making and story-telling, while undeniably pleasurable, was treated by some parents and teachers alike as comparably frivolous to the boy stuff, with its ledgers and numbers and chemicals that burbled in a cup. In the end, everyone, regardless of their future majors, came to believe that boy stuff was serious— meaningful math, salient science—better than girl stuff, and ultimately more valuable.

“It’s not just an arbitrary wall either,” they say, borrowing my metaphor. “You see it on campus, too—where the money goes, where the investments are made.” I’m not arguing. My students, deft noticers that they are, cite a leaky roof and shingles falling from the English building, while the university boasts “comprehensive upgrades” and “state-of-the-art facilities” in buildings where biology and chemistry are housed. They suggest we are living with divisions that cannot be ignored. They are right, of course, right down to their corpus callosums.

“So,” I say, “one mission for the lyric essayist is to identify and render on the page these kinds of incongruities, inequalities , and by doing so, we can challenge them. We can shine a probing light into places certain powers that be may not want us to look. Don’t ever let anyone tell you lyric essays can’t be political.”

The students are agitated, in a good way. They’re thinking about lyric essays as epistles, lyric essays as petitions and caveats and campaigns.

“To do our best work,” I say, “we need to mobilize all our resources—not only of structure and form but even the nuances of language itself. We need to mine every lexicon available to us, not just words we think of as ‘poet-words.’ In a lyric essay, we can bring multiple languages and kinds of discourse together.”

Someone raises a hand. “Is this your roundabout way of telling us the lyric essay isn’t actually more art than science?”

I shake my head. “To tell you the truth, I’m not sure if the lyric essay is more art than science. I’m not even sure the lyric essay belongs under the genre-banner of creative nonfiction at all . ”

“Well, how would you classify it then?” someone asks without raising a hand.

“ Mystery ,” I say, and now I surprise myself with this sudden stroke of certainty, like emerging from heavy fog into sun. Some of my students giggle, but all the ears in the room have perked up. “I think lyric essays should be catalogued with the mysteries.” I am even more certain the second time I say it.

“So, just to clarify—do you mean the whodunnits or like, the paranormal stuff?”

“Yes,” I smile. “ Exactly .”

_____________________________________

From A Harp in the Stars: An Anthology of Lyric Essays , edited by Randon Billings Noble, courtesy University of Nebraska Press.

Julie Marie Wade

Previous article, next article.

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

- Course search

Institute of Continuing Education (ICE)

Please go to students and applicants to login

- Course search overview

Creative writing: an introduction to the Lyric essay

- Courses by subject overview

- Archaeology, Landscape History and Classics

- Biological Sciences

- Business and Entrepreneurship

- Creative Writing and English Literature

- Education Studies and Teaching

- Engineering and Technology

- History overview

- Holocaust Studies

- International Relations and Global Studies

- Leadership and Coaching overview

- Coaching FAQs

- Medicine and Health Sciences

- Philosophy, Ethics and Religion

- History of Art and Visual Culture

- Undergraduate Certificates & Diplomas overview

- Postgraduate Certificates & Diplomas overview

- Applying for a Postgraduate Award

- Part-time Master's Degrees overview

- What is a Master's Degree (MSt)?

- How to apply for a Master's Degree (MSt)

- Apprenticeships

- Online Courses

- Career Accelerators overview

- Career Accelerators

- Weekend Courses overview

- Student stories

- Booking terms and conditions

- International Summer Programme overview

- Accommodation overview

- Newnham College

- Queens' College

- Selwyn College

- St Catharine's College

- Tuition and accommodation fees

- Evaluation and academic credit

- Language requirements

- Visa guidance

- Make a Donation

- Register your interest

- Gift vouchers for courses overview

- Terms and conditions

- Financial Support overview

- Concessions

- External Funding

- Ways to Pay

- Information for Students overview

- Student login and resources

- Events overview

- Open Days/Weeks overview

- Master's Open Week 2023

- Postgraduate Open Day 2024

- STEM Open Week 2024

- MSt in English Language Assessment Open Session

- Undergraduate Open Day 2024

- Lectures and Talks

- Cultural events

- International Events

- About Us overview

- Our Mission

- Our anniversary

- Academic staff

- Administrative staff

- Student stories overview

- Advanced Diploma

- Archaeology and Landscape History

- Architecture

- Classical Studies

- Creative Writing

- English Literature

- Leadership and Coaching

- Online courses

- Politics and International Studies

- Visual Culture

- Tell us your student story!

- News overview

- Madingley Hall overview

- Make a donation

- Centre for Creative Writing overview

- Creative Writing Mentoring

- BBC Short Story Awards

- Latest News

- How to find us

- The Director's Welcome

The deadline for booking a place on this course has passed. Please use the 'Ask a Question' button to register your interest in future or similar courses.

Aims of the course

- To introduce participants to the genre of creative non-fiction known as the lyric essay.

- To provide students with the opportunity to practise techniques and try out different forms.

- To offer a first overview of the way the genre is used as a political tool and to express aspects of identity.

Course content overview

- The lyric essay was coined by the editors of the Seneca Review in 1997, as a way of defining the kind of short-form creative non-fiction they had begun to publish in the journal.

- Over the last two decades, the lyric essay has grown in popularity among writers and readers in the US and interest is growing in the rest of the English-speaking world.

- It can be distinguished from other types of creative non-fiction by its emphasis on form, formal innovation and attention to the physical properties of language. In this way, its composition and its effect on the reader come closer to poetry than to other kinds of prose.

- The ‘lyric’ in lyric essay refers to the centrality of the author’s particular voice, perspective and subjective or experiential truth. This is another characteristic that distinguishes it from other forms of non-fiction such as journalism or academic writing.

- After a first week, in which participants are introduced to the genre and these distinguishing characteristics are explained, they will spend the course learning about some of the many possibilities it offers in terms of form and subject matter e.g. the ‘braided essay’, the ‘hermit crab essay’, essay as commentary or ‘erasure’ memoir, place, political activism and so on.

- Participants will have set reading each week, which will be discussed in the tutor presentations, and which they will be able to discuss further on a forum on the VLE.

- Participants will also have the opportunity to do an activity each week, and can post the results on a separate forum, where they will receive feedback from the tutor and be able to post feedback on each other’s work.

Schedule (this course is completed entirely online)

Orientation Week: 20-26 February 2023

Teaching Weeks: 27 February-2 April 2023

Feedback Week: 3-9 April 2023

Teaching Week 1 - What is the lyric essay?

Participants will be introduced to the concept of the lyric essay, its history, its scope and what distinguishes it from other prose forms.

Using published essays as examples, participants will work on an exercise which will enable them to generate subject material for essays through association, and organise this material as a series of fragments.

Learning outcomes

By studying this week the participants should have:

- Acquired an understanding of what distinguishes the lyric essay from other prose forms.