Studying With Music: Arguments for & Against

Does music really help you study?

- By Sander Tamm

- Aug 4, 2021

E-student.org is supported by our community of learners. When you visit links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

At some point, almost every student has experimented with using background music as a means to study or work more efficiently.

It is no wonder, then, that the iconic YouTube channel Lofi Girl is currently approaching the 1B views mark.

But, does music actually make a legitimate difference in the effectiveness of an individual study session?

According to relevant science, listening to music while studying does have its advantages as well as significant disadvantages – one thing is for sure, there is no concrete “yes or no” answer to whether music affects studying positively.

If we leave the science out of it and look at the individual opinions of students, things stay just as complicated – many students swear by background music, while many learners are completely against ANY background noise.

The debate on whether music can help you study or not tends to boil down to two concrete arguments.

One side has the opinion that listening to music helps improve focus and concentration . The other camp says that they don’t want any additional noise because their own thoughts provide enough distraction as it is. Thus, for these students, music seems to make concentration even more difficult.

In this article, we will be looking at both the science and the individual experience of the students. In addition, we will explore both the advantages and disadvantages of listening to music while studying.

Hopefully, the article will let you decide on which option would suit you better – studying in complete silence or doing the brain crunching with some light background music on.

Without further ado, let’s get started by looking at some advantages of listening to music while studying.

Here’s what you’ll find in this article:

Studying with Music

Arguments for listening to music while studying.

Here are four major advantages of listening to music while studying:

Relaxing music can combat study-related stress

Learning about a new subject or going through a demanding online course can be overwhelming and stressful, even for the brightest of minds. Therefore, it is essential (at least if you want the study session to be fruitful) to study with a positive mindset.

Why? Well, research suggests that positive affect (term used in psychology for positive emotions and expression) improves a variety of cognitive processes.

Simply put, you will learn better when you are in a good mood.

This is where listening to music comes in – according to scientists from Stanford University , music can change brain functioning to the same extent as meditation.

It is a quick, easy, and cheap way of flooding your brain with endorphins and reaping the benefits of improved cognitive function immediately.

Music can help with completing repetitive tasks

According to a study by Fox & Embrey (1972), music can be a great productivity aid when you need to perform repetitive and more simple tasks.

For example, try listening to music when rewriting or editing a paper. Music can inspire you to tackle these somewhat tedious activities with greater efficiency.

Music can inspire you to tackle these somewhat tedious activities with greater efficiency. For example, try listening to music when rewriting or editing a paper. You’ll quickly see that you work more quickly and efficiently when listening to music.

Music can also make a boring activity seem less boring. Listening to music while doing something mundane, like creating charting tables or creating columns for Cornell notes .

Music can help with memorization

In one way or another, all learning is about memorization. And, according to science, background music can have a positive impact on human memory .

So, next time you are trying to memorize phrases from an online language course , have some background music on. It just might give your learning that extra boost.

Listening to music with headphones can cancel noise pollution

In a perfect world, you could always choose exactly where and when you study. Unfortunately, that is not always the case.

There will be times when your study environment will work against you – distractions can come in the form of other family members, roommates, or traffic noise.

In such cases, putting on a pair of headphones would be a great way of fighting noise pollution . After all, a soothing collection of tunes will be a much better background to your studies than hearing your roommate play video games for hours on end.

Arguments against listening to music while studying

These are the two main drawbacks to listening to music while studying:

Lack of concentration

Whether you consciously notice it or not, your brain will put some extra resources into “decoding” the music playing in the background. This is especially true for songs with lyrics – instead of focusing on your studies, you will unconsciously try to listen to what the singer is saying. This can ultimately decrease your productivity by 10%. Thus, for tasks that require cognitively demanding and creative mental work, complete silence would be the best possible solution.

Complete silence promotes increased blood flow to the brain. This, in return, directly affects your capability to tackle more demanding mental tasks.

So, if you are planning on mastering a hard skill like PHP or Python , always try to find a place as silent as possible.

Music can trigger bad memories

Music can put you in a positive mood (thus enhancing your cognitive capabilities), but the reverse is also possible.

Some music can come with bad associations and lead you to a more negative state of mind. Which, in return, will dampen your learning capabilities.

You can combat this by avoiding music that is too dark or downbeat. Thinking about your high school heartbreaks is the last thing you want when studying for that Advanced Calculus exam.

4 Tips for using background music to enhance your mental capacity

If you are planning on experimenting with listening to music while studying, there are some things to consider. These tips will help you avoid some mistakes students commonly make when studying with background music.

Avoid music with lyrics!

It is not a coincidence that most of the music associated with studying is entirely instrumental.

According to a study by Perham/Currie (2014), music with lyrics has a negative effect on reading comprehension performance. The same study also finds that the same applies even when the student enjoys the music or already knows the lyrical content.

To conclude, do not choose albums, playlists, or songs with any lyrical content.

If you are not knowledgeable about instrumental music, the Lofi Girl YouTube channel mentioned in the introduction is the best place to start. For further inspiration, we will also list some music styles that we recommend experimenting with.

But, before we get into specific styles, allow me to explain why not all instrumental music works as a backdrop for a learning session.

Use background music that follows clear patterns

We already established that the debate is still on whether listening to music while studying is beneficial or not. But, one thing is clear – the type of music you choose for your study sessions matters!

Not any instrumental music is suitable background music by default. Music that is too progressive in nature is likely to throw your brain off the loop and distract you.

For example, listening to jazz while studying might “make sense” to some students, but jazz is quite chaotic in nature. Thus, I wouldn’t choose jazz as background music for studying, even if the pieces are entirely instrumental.

The lo-fi hip-hop beats have become such popular choices for study music because they generally follow a clear, defined rhythm. These beats provide a pleasant background ambiance that does not demand your brain for attention.

Here are some other examples of music styles suitable for learning:

- Ambient – Brian Eno, possibly the most famous ambient composer of all time, has described ambient music as music that “induces calm and a space to think”. This is exactly what you want when selecting suitable music for getting some studying done.

- Downtempo – Similar to ambient, but with a bigger focus on beats. The atmospheric sounds and the mellow beats make downtempo a great backdrop for long study sessions.

- Classical – The Mozart Effect has been effectively debunked . Listening to classical music does NOT make you smarter. Still, classical music can enhance your mood and put you in the right mind frame for studying. Reading while listening to classical is something that works particularly well for many students.

- Deep house – An unconventional choice, but something that has worked for me and several other students we interviewed. Deep house has very little variation, the beats are hypnotic, and the rhythms are soothing.

Of course, this is not an exhaustive list. What works for one student, might not work for someone else. So, feel free to experiment with different albums, playlists, and artists to see what works best for your study routine.

Make your choices before the learning sessions

You have probably heard that some of the most high-performing individuals in the world consciously limit their daily choices. This is a great strategy for avoiding decision fatigue as much as possible.

Decision fatigue is the last thing you want when engaging in mentally demanding work such as studying. Thus, if you are planning on studying with background music playing, choose your music well in advance. Preferably the day before your learning session.

Take regular breaks

You can use the stopping of music as a cue for a study break. For example, prepare separate playlists for your learning sessions. When one playlist is finished, take a break.

Since your brain has learned to associate music with studying, you will find it that much easier to relax and switch off when the music stops.

When you resume learning, your mind will be fully refreshed and ready to absorb new information.

The usefulness of background music for studying depends on many variables. It all comes down to the specific music listened to, what you are studying, and the environment where you study.

Of course, the personality and the study habits of a given student are also important.

Everyone has different preferences, so you will need to experiment with what works for you. Some people may find that listening to music while studying helps them focus more and retain information better. Others will do better in silence without any noise at all.

The scientific evidence is also inconclusive. Some studies show that music can help improve attention and memory, while other studies find no benefits for listening to music while studying.

If you do decide to experiment with having background music on while studying, there are some key takeaways to consider.

For one, anything with lyrics should be avoided. The same goes for music that is too loud and intense or too progressive. Instead, opt for music that is repetitive and classically pleasant.

Also, be sure to prepare your playlists or streams BEFORE starting studying. Choosing songs while engaging with your studies is a surefire formula for throwing your brain off the loop and hurting your concentration levels.

Sander Tamm

Fluentu spanish: does the youtube video method work.

FluentU Spanish is a good option for exploring entertainment subjects in Spanish. Although it can be a fun learning experience, it lacks structure and the coverage of different linguistic skills.

Handwritten vs. Typed Notes: Which Is Really Better?

Taking notes by handwriting vs. typing: which is really better?

10 Best Skillshare Classes for Designers & Creatives

Skillshare has a massive catalog of high-quality online courses. Here, you’ll find the best of the bunch.

Does Listening to Music Really Help You Study?

Experts from the department of psychology explain whether or not music is a helpful study habit to use for midterms, finals, and other exams.

By Mia Mercer ‘23

Students have adopted several studying techniques to prepare for exams. Listening to music is one of them. However, listening to music may be more distracting than helpful for effective studying.

There’s no season quite like an exam season on a university campus. Students turn to varying vices to help improve their chance of getting a good grade. While some chug caffeine, others turn up the music as they hit the books.

Although listening to music can make studying more enjoyable, psychologists from the Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences have found that this popular study habit is more distracting than beneficial.

“ Multitasking is a fallacy; human beings are not capable of truly multitasking because attention is a limited resource, and you can only focus on so much without a cost,” cognitive psychologist Brian Anderson said. “So when you’re doing two things at the same time, like studying and listening to music, and one of the things requires cognitive effort, there will be a cost to how much information you can retain doing both activities.”

In basic terms of memory, Anderson explained that we do a better job of recalling information in the same conditions in which we learn the material. So when studying for an exam, it’s best to mimic the exam conditions.

“If you have music going on in the background when you study, it’s going to be easier to recall that information if you also have music on in the background when you take the exam,” Anderson said. “However wearing headphones will almost certainly be a violation during most exams, so listening to music when you’re studying will make it harder to replicate that context when you’re taking an exam.”

Even though experts suggest listening to music can hinder your ability to retain information while studying, some students choose to continue the practice. Steven Smith, cognitive neuroscientist for the Department of Psychological & Brain Sciences , provided some suggestions for students who wish to continue this study habit.

“In general, words are distracting,” Smith shared. “So if you want to listen to music while you study, try to listen to something that does not have words, or if it does have words, hopefully, it’ll be in a language that you don’t understand at all, otherwise that’s going to distract from the stuff you’re trying to study.”

Smith also suggested listening to familiar background music, because it’s less distracting than something new or exciting. Additionally, Smith provided some principles that generally result in better exam results.

“Make sure your studying is meaningful because comprehension gets you so much further than raw repetition,” Smith shared. “Also, you must test yourself, because it’s the only way you can learn the material; this is called the testing-effect. And finally, try to apply the spacing-effect, where you spread out your study sessions rather than cramming your studying all together, allowing for better memory of the material.”

Regardless of how students decide to study for exams, it’s important to remember that we all learn differently.

“There are individual differences between everyone,” Smith said. “Some people need a study place that is boring, predictable, and exactly the same so that they can concentrate, and others find it more beneficial to go to different places to study. It’s true that there are different personalities, so try and find what study habit works best for you.”

- The College at Work

- Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences

- Preparing for Exams

The Effects of Listening to Music While Studying Research Paper

Introduction.

Music is a human construct, because humans have to acknowledge and define the existence of an objective reality of sound into music. Every human culture uses music to promote its ideas and ideals and music is intrinsically interwoven in the fabric of each society. Music is considered as a powerful tool for shaping individual abilities and character, and “musicality is a universal trait of humankind.” (Hallam, Susan, 2006). “If sounds are created or combined by a human being, recognized as music by some group of people and serve some functions which music has come to serve for mankind, then those sounds are music.”(Radocy and Boyle, 1988, p.19).

With the advent of modern electronic gadgets students are exposed to more and more avenues of entertainment and study time is not devoid from the interference of these gadgets. How music, particularly background music, affect student learning is an area attracting much research, and it is finding difficult to produce conclusive evidence to support this habit.

The Oxford Dictionary defines music as “the art of combining sounds of voice(s) or instrument(s) to achieve beauty of forms and expression of emotion.” The effect of music on individual to individual will be at variance as it depends on subjective judgments of what constitutes beauty of form and expression of emotion of an individual. Miller (2000) argues that:

“music exemplifies many of the classic criteria for a complex human evolutionary adaptation. He points out that no culture has ever been without music (universality); musical development in children is orderly; musicality is widespread (all adults can appreciate music and remember tunes); there is specialist memory for music; specialized cortical mechanisms are involved; there are parallels in the signals of other species—for example, birds, gibbons and whales—so evolution may be convergent; and music can evoke strong emotions, which implies receptive as well as productive adaptations” (Hallam, 2006, p.2).

Many historical evidences show that music existed many thousands of years ago and several musical instruments were developed in different parts of the world. According to theorization of Huron (2003), music developed among different cultures as a part of courtship behavior, social cohesion, group effort, perceptual development, motor skill development, conflict reduction, safe time passing, and a mnemonic device of trans-generational communication.

Music has multiple functions which influence development of individuals, social groups and the society as a whole. Music as a medium of expressing human feelings transcend into enforcing social norms and continuity and stability of culture, at the same time contributes to the integration of society. In the perspective of an individual music is a medium for emotional expression particularly when words and verbal exchanges are difficult to establish. It has the power to influence individual mood as well as induce relaxation or stimulate mental or physical performance.

Scientific evidence show that the human brain has systems for music perception which operate from birth, enabling ‘significant nonverbal communication in the form of music’ (Gaston 1968, p.15 as quoted by Hallam p, 4). It is also suggested that participating in music generates social bonding and cultural coherence as well as formation and maintenance of group identity, collective thinking, coalition forming, and promotion of co-operative behavior.

Though there are arguments that music exists simply because of the pleasure that it affords, its basis is purely hedonic, there is no doubt that engagement with it is rewarding for human beings. Even though music has varied roles to play in individual and social development the extent to which music education is provided through state education systems internationally varies.

The approach to formal music education focuses on listening, understanding and appreciation of music, performance, and creativity or it is integrated with general arts education. However, a comprehensive music education approach has not been evolved so far. At present academicians and education professionals express deep concern about the nature, role, importance, and future of arts education in the schools in order to provide quality education to younger generations and make them successful in their future education and career development.

Much of the research results indicate that education in arts provides significant cognitive benefits and boosts academic achievement, beginning at an early age and continuing through school. Music helps to develop cognitive and higher order thinking skills necessary for academic success, as music improves individual talent in the rhythm sense, physical coordination, motor skills, critical thinking, memory recall, listening, and logic development. Research studies have shown that students who listen to music have higher spatial scores, the ability to form mental images of physical objects, on intelligence tests. (Rauseher, et al., 1994)

Among students of arts with music it is found that they learn how to work cooperatively, pose and solve problems, and forge the vital link between individual or group effort and quality of results, which are important for success in a competitive workplace. Well organized arts education contributes to building technological competencies as well as higher level thinking skills of analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating both personal experience and objective data. In addition, arts education enhances student’s respect for the cultures, belief systems, and values of their fellow learners.

Along with the advancement in scientific techniques, for studying functioning of brain, there is proportionate increase in research exploring the representation of music-related functions of the brain. Altenmuller (2003) states that “the neural systems underlying music appear to be distributed through the left and right cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres, with different aspects of music processed by distinct neural circuits.”(Hallam p.11).

Further researchers opine that the majority of relevant sound information is neurally encoded, even if we are not consciously aware of it, and the attention process of the listener has important implications for the variations of their reaction to music. It is also found that music activates large parts of auditory cortex in both hemispheres of our brain. There is a wide range of music-related behaviors, such as amusia (loss of musical function), aphasia (loss of language functions), etc., which are influenced by brain functions that can be spared or impaired depending on the extent of damage to brain.

Learning occurs by the self-organization of cerebral cortex in response to external stimuli, and learning and memory are based on changes in “synaptic efficacy in the brain.” (Hallam, p.17) The brain network undergoes changes for adapting cortical remodeling, with effective connections between neurons. The brain is able to adapt quickly to environmental demands in the short and long term, and over time develops appropriate neurological structures to meet individual needs. It is evidenced that “the brain responds to behavioral needs but, once developed, enhanced brain functions operate in processing under passive listening conditions, suggesting that they are deeply engrained processing strategies shaped by years of musical experience” (ibid p.19).

LeDoux (1996) suggests that music is capable to activate phylo-genetically old parts of the nervous system that are strongly implicated in the induction of learning of fear responses which operate subconsciously (ibid p.21). When we hear music or other sounds, our emotional responses to them are controlled by amygdale, which provide a more complete cognitive assessment of the situation. In the same pattern when the students are taught about rhythm through verbal, logical explanations accompanied by musical examples, then their approach will be controlled by nature of learning. With adequate time spent in learning, the brain will develop appropriate neurological networks to retain the knowledge and skills learnt.

Research suggests that listening to music while studying may “distract attention from the studied material, thereby impeding learning.” (Tan, L. 1999). Music is every where in the life of an individual, starting from the fetus stage till the end of the life. People listen to different types of music depending on their mood, and the effects of listening to music are personal to each person, which produces different emotion to different people. Any music played while the attention of the listener is focused primarily on a task or activity other than listening to music, is defined as “background music,” and an individual engaged in studying or academic preparation may not be aware of the music in their immediate environment (Radocy & Boyle, 1988).

It may be possible that music enhances some individual’s learning, but it may be distracting to others. Researchers like Radocy & Boyle (1988) have explored the possible transfer of cognitive abilities to other curricular areas by hypothesizing that exposure to music, through participation and formal instruction can facilitate nonmusical learning. With popularization of “Mozart effect” in 1993 by Rauscher et al, claim that listening to Mozart improves intelligence, there is much argument about the potential role of music in developing intelligence, particularly in students.(Listening to music)

Research has found that positive, happy music helps the learner to remember positive facts, whereas negative, sad music helps the learner to remember negative facts, and may even hinder the recall of positive facts. As the brain has to associate the music with an emotion, and when what is being studied is comparable to the music being heard, then the music will help recall the learning. It is common among students to engage in multi-tasking, meaning watching TV, listening to music, surfing the web and chatting online while doing home work.

With multi-tasking students get a superficial understanding of the studied material. As many activities interfere with the studies leading to poor performance, it can have negative impact on learning of students. It is difficult to identify whether passive distraction affect student learning as student’s study preferences vary from individual to individual. For some students’ music functions like a shield from distractions, and for others music can produce emotional soothing.

And for those with attention-deficit disorder, who are constantly seeking stimulation, some distraction may be helpful to concentrate on their studies. If the students are able to identify their potential and they find listening to music makes them more enjoyable to do homework and studying it will be probably a good approach as long as it does not affect their learning.

The constantly changing media and influx of more and more entertainment industry activities are more likely to divide the mind and interrupt studying than what was happening with background music. However, educators need to acknowledge the power that music has to influence moods, emotions, and arousal levels as music stimulates rewards systems in the brain and engagement with it is naturally enjoyable. Through informal engagements with music in a range of social occasions, where children will have extensive exposure to a wide range of musical genres, it will be easy to amalgamate music in the life of students without interfering with their studies.

Works Cited

Rauscher, F., Shaw, G., Levine, L., Ky, K., and Wright, E. Music and Spatial task performance: a casual relationship. Paper presented at the American Psychological Association 102 nd Annual Convention, Los Angeles, CA.

Radocy, R.E., and Boyle, J.D. Psychological Foundations of Musical Behavior (2 nd ed). Springfield: Charles C. Thomas. 1988.

Hallam, Susan. Music Psychology in Education. London: Institute of Education, University of London. 2006. Web.

Tan, L. Effects of distracting noise on study efficacy. Journal of Psychology. 23, (233-226). 1999.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, April 29). The Effects of Listening to Music While Studying. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-effects-of-listening-to-music-while-studying/

"The Effects of Listening to Music While Studying." IvyPanda , 29 Apr. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/the-effects-of-listening-to-music-while-studying/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'The Effects of Listening to Music While Studying'. 29 April.

IvyPanda . 2022. "The Effects of Listening to Music While Studying." April 29, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-effects-of-listening-to-music-while-studying/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Effects of Listening to Music While Studying." April 29, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-effects-of-listening-to-music-while-studying/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Effects of Listening to Music While Studying." April 29, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-effects-of-listening-to-music-while-studying/.

- Classical Music: Influence on Brain and Mood

- Mindful listening

- Music Effects on the Brain

- Concreteness of Words and Free Recall Memory

- Helpful Listening Skills Review

- Action Plan for Better Listening

- Brain and Memory

- How to Enhance Listening Skills

- Listening to Children: Why Is It Important?

- How Music Affects the Brain?

- Society and Social Policy Analysis

- Social Construction Model Analysis

- Cognitive Psychology: Culture and Cognition

- Cognitive Psychology: Intelligence and Wisdom

- Deductive Reasoning: Social Contract Algorithm

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site and to show you personalised advertising. To find out more, read our privacy policy and cookie policy

- Media Centre

Is it OK to listen to music while studying?

October 17, 2019

UOW researcher answers this tricky question as NSW students start written exams for the HSC.

It’s a good question! In a nutshell, music puts us in a better mood, which makes us better at studying – but it also distracts us, which makes us worse at studying.

So if you want to study effectively with music, you want to reduce how distracting music can be, and increase the level to which the music keeps you in a good mood.

Read more: Curious Kids: Why do adults think video games are bad?

Music can put us in a better mood

You may have heard of the Mozart effect – the idea that listening to Mozart makes you “smarter”. This is based on research that found listening to complex classical music like Mozart improved test scores, which the researcher argued was based on the music’s ability to stimulate parts of our minds that play a role in mathematical ability.

However, further research conclusively debunked the Mozart effect theory: it wasn’t really anything to do with maths, it was really just that music puts us in a better mood.

Research conducted in the 1990s found a “Blur Effect” – where kids who listened to the BritPop band Blur seemed to do better on tests. In fact, researchers found that the Blur effect was bigger than the Mozart effect, simply because kids enjoyed pop music like Blur more than classical music.

Being in a better mood likely means that we try that little bit harder and are willing to stick with challenging tasks.

Music can distract us

On the other hand, music can be a distraction – under certain circumstances.

When you study, you’re using your “working memory” – that means you are holding and manipulating several bits of information in your head at once.

The research is fairly clear that when there’s music in the background, and especially music with vocals, our working memory gets worse .

Likely as a result, reading comprehension decreases when people listen to music with lyrics . Music also appears to be more distracting for people who are introverts than for people who are extroverts, perhaps because introverts are more easily overstimulated.

Some clever work by an Australia-based researcher called Bill Thompson and his colleagues aimed to figure out the relative effect of these two competing factors - mood and distraction.

They had participants do a fairly demanding comprehension task, and listen to classical music that was either slow or fast, and which was either soft or loud.

They found the only time there was any real decrease in performance was when people were listening to music that was both fast and loud (that is, at about the speed of Shake It Off by Taylor Swift, at about the volume of a vacuum cleaner).

But while that caused a decrease in performance, it wasn’t actually that big a decrease. And other similar research also failed to find large differences.

So… can I listen to music while studying or not?

To sum up: research suggests it’s probably fine to listen to music while you’re studying - with some caveats.

It’s better if:

- it puts you in a good mood

- it’s not too fast or too loud

- it’s less wordy (and hip-hop, where the words are rapped rather than sung, is likely to be even more distracting)

- you’re not too introverted.

Happy listening and good luck in your exams!

Read more: Curious Kids: Why do old people hate new music?

Timothy Byron , Lecturer in Psychology, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

UOW academics exercise academic freedom by providing expert commentary, opinion and analysis on a range of ongoing social issues and current affairs. This expert commentary reflects the views of those individual academics and does not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of the University of Wollongong.

You may also be interested in

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The effect of preferred background music on task-focus in sustained attention

Department of Psychology, Goldsmiths University of London, London, UK

Karina J. Linnell

Associated data.

Datasets obtained during, and/or analysed during, the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Although many people listen to music while performing tasks that require sustained attention, the literature is inconclusive about its effects. The present study examined performance on a sustained-attention task and explored the effect of background music on the prevalence of different attentional states, founded on the non-linear relationship between arousal and performance. Forty students completed a variation of the Psychomotor Vigilance Task —that has long been used to measure sustained attention—in silence and with their self-selected or preferred music in the background. We collected subjective reports of attentional state (specifically mind-wandering, task-focus and external distraction states) as well as reaction time (RT) measures of performance. Results indicated that background music increased the proportion of task-focus states by decreasing mind-wandering states but did not affect external distraction states. Task-focus states were linked to shorter RTs than mind-wandering or external distraction states; however, background music did not reduce RT or variability of RT significantly compared to silence. These findings show for the first time that preferred background music can enhance task-focused attentional states on a low-demanding sustained-attention task and are compatible with arousal mediating the relationship between background music and task-performance.

Introduction

Although many people listen to background music during tasks that require sustained attention, there is still no consensus about its effect on performance (for reviews, see Kämpfe, Sedlmeier, & Renkewitz, 2011 ; Küssner 2017 ). Research has focused on background music and sustained attention for decades (e.g., Davies, Lang, & Shackleton, 1973 ) but findings are contradictory, with some studies suggesting a positive influence of the music (e.g., Davies et al., 1973 ; Corhan & Gounard, 1976 ; Fontaine & Schwalm, 1979 ; Turner, Fernandez, & Nelson, 1996 ; Ünal, Waard de, Epstude, & Steg, 2013 ) but others suggesting the opposite (e.g., Brodsky & Slor, 2013 ; Febriandirza, Wu, Ming, Hu, & Zhang, 2017 ; North & Hargreaves, 1999 ; Shih, Huang, & Chiang, 2012 ).

Even though sustained attention is crucial for successful performance (Robertson & O’Connell, 2010 ), sustaining focus on task-relevant information over an extended time period is demanding, leading to time-on-task effects and attentional lapses (Robertson, Manly, Andrade, Baddeley, & Yiend, 1997 ; Unsworth & Robison, 2016 ). Attentional lapses have been found to be underpinned by the locus coeruleus–norepinephrine system (LC–NE; Cohen, Aston-Jones, & Gilzenrat, 2004 ), a neuromodulatory nucleus in the brain stem that projects norepinephrine to the neocortex and mediates effects of arousal (Berridge & Waterhouse, 2003 ). When baseline LC activity, or arousal, is either too low or too high, people perform poorer (Aston-Jones & Cohen, 2005 ) and experience attentional lapses that have been characterised, respectively, as episodes of mind-wandering (hypo-arousal) or external distraction (hyper-arousal) (i.e., off-task attentional states; Unsworth & Robison, 2016 ). Only an intermediate baseline LC activity is linked to optimal performance and a task-focused attentional state (i.e., on-task state; see Fig. 1 ; Aston-Jones & Cohen, 2005 ; Unsworth & Robison, 2016 ).

Inverted-U relationship between arousal, attentional states (mind-wandering, task-focus, external distraction) and performance, as hypothesised by Unsworth and Robison ( 2016 ) and in similar form Yerkes and Dodson ( 1908 )

Understanding the effect of background music on these different arousal-driven on-task and off-task attentional states (see Fig. 1 above) is important for theoretical as well as practical reasons: it is important for improving our understanding both (i) of the real-life situations in which background music listening might be beneficial for attention and performance and also (ii) of core attentional function, and the complex relationship between arousal and attention. To our knowledge, our study is the first that has explored the relationship between background music and the prevalence of different attentional states—both on-task and off-task—on a sustained-attention task. In addition, the fact that it focused on self-selected background music distinguishes it further and gives it ecological validity and contemporary relevance.

As previous research has suggested, arousal may mediate the relationship between background music and performance (Beh & Hirst, 1999 ; Cassidy & MacDonald, 2007 ; North & Hargreaves, 1999 ; Ünal et al., 2013 ; Wang, Jimison, Richard, & Chuan, 2015 ). Specifically, in line with the inverted-U curve linking arousal to performance, previous research has found that background music increases arousal (Burkhard, Elmer, Kara, Brauchli, & Jäncke, 2018 ; Ünal et al., 2013 ) and that, when people are presented with an easy low-arousing task, the music can increase arousal resulting in better performance (Fontaine & Schwalm, 1979 ; Ünal et al., 2013 ). Contrarily, when people are presented with a difficult more arousing task, the music results in poorer performance, compatible with music increasing arousal to too high a level (Beh & Hirst, 1999 ; North & Hargreaves, 1999 ; Wang et al., 2015 ). In the current study, we used an easy low-arousing sustained-attention task—a version of the standard sustained-attention task called the Psychomotor Vigilance Task previously used by Unsworth and Robison ( 2016 )—to imitate the boringness of real-life monotonous tasks and to maximise the potential for music to produce, via arousal, a beneficial effect.

Using self-selected or preferred music in this study, we could manipulate the ‘arousingness’ of the environment in an ecologically valid manner and control for personal preferences (Cassidy & MacDonald, 2009 ; Darrow, Johnson, Agnew, Fuller, & Uchisaka, 2006 ; Ünal, Steg, & Epstude, 2012 , Ünal et al., 2013 ) as well as individual differences in baseline arousal. Because baseline arousal level varies across people and depends on factors, such as personality (e.g., Cassidy & MacDonald, 2007 ; Furnham & Allass, 1999 ; Salame & Baddeley, 1982 ), the ‘arousingness’ and the qualities of the music required to achieve optimal arousal and performance also varies across people. Nevertheless, we conducted exploratory analyses of the impact on sustained attention of qualities of the preferred music stimuli, namely tempo, lyrics and genre, as these have all been shown to impact attention and performance (see, e.g., Amezcua, Guevara, & Ramos-Loyo, 2005 ; Angel, Polzella, & Elvers, 2010 ; Chew, 2010 ; Corhan & Gounard, 1976 ; Darrow et al., 2006 ; Davies et al., 1973 ; Drai-Zerbib & Baccino, 2017 ; Shih et al., 2012 ).

In this study, we aimed to see how preferred background music impacts the distribution of attentional states, as well as the effects of time-on-task on sustained attention. By adopting subjective reports of attentional states, the present study aimed to provide a richer and more informative measure of attention than is available from performance-based measures (Unsworth & Robison, 2016 ). Participants were asked to report their conscious experience at random periods throughout the task. Eliciting these subjective reports allowed us to distinguish poorer performance that resulted from the two types of attentional lapses, mind-wandering (hypo-arousal) and external distraction (hyper-arousal), and to explore the differential effect of background music on these lapses. Furthermore, measuring the percentage of task-focus reports gave an indication of how close to optimal performance was, in a way that focusing only on performance-based measures could not.

In addition to collecting subjective reports of attentional state, the present study examined the impact of background music on time-on-task effects. Background music might exert a positive influence on time-on-task effects via arousal: given that arousal falls off with time-on-task (e.g., Whyte, Polansky, Fleming, Coslett, & Cavallucci, 1995 ), it might need to be boosted by the music over time to reach an optimal level. Alternatively, it could also be the case that any beneficial effects of the music over time would be counteracted by the increasing tendency of participants to habituate to the music (Burkhard et al., 2018 ).

In our first hypothesis, we predicted an interaction effect between attentional-state category (i.e., mind-wandering, task-focus, external distraction) and background music. Specifically, we expected that preferred background music would increase the proportion of task-focus states compared to states of mind-wandering and external distraction. This interaction effect was measured on proportions of subjectively reported attentional states as a function of music-present/absent. We also looked at how the proportion of task-focus reports changes during performance as a measure of time-on-task.

In the second hypothesis, we expected on-task states (task-focus) to be linked to faster reaction times (RTs) than off-task states (mind-wandering, external distraction) to verify that subjective reports are a valid representation of attentional state and express themselves in behaviour (Unsworth & Robison, 2016 ).

Our third hypothesis was based on the first two hypotheses and predicted that if background music is linked to more task-focus states and task-focus is linked to faster and less variable RTs, then we would expect an effect of background music on RTs. Therefore, we hypothesised that mean RTs would be shorter, and increases in RTs with time-on-task would be smaller, with background music than in silence.

The design was a within-subject design; all participants completed the task in silence and with background music. The independent variables were music-present/absent, time-on-task (block 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5) and attentional-state category (mind-wandering, task-focus, external distraction). The order of the music conditions was counterbalanced, meaning that every second, participant completed the task in the same order. This resulted in 20 participants completing the task in music-present followed by music-absent order and 20 participants in music-absent followed by music-present order. One dependent variable was the frequency with which each of the three attentional-state categories was reported, henceforth termed thought-probe response proportions. The other two dependent variables were RT (in milliseconds; ms), and standard deviation of RT, while performing a sustained-attention task. Prior to the main experiment, a pilot study was conducted.

Participants

Participants were students living in and around London, who took part in the study on a voluntary basis in exchange for £5. Only students who normally listen to background music when performing attention-demanding tasks were included in the experiment. This inclusion criterion was supported by findings that people perform better in their preferred listening condition (Crawford & Strapp, 1994 ; Nantais & Schellenberg, 1999 ). There were 40 participants in total. The sample size was based on a power calculation showing that a minimum sample of 34 people would be sufficient for a medium (0.25) effect size with a 0.80 power level and 0.05 alpha level.

Participants included 23 females and 17 males between the ages of 19 and 32 ( M = 24, SD = 3.33). Analysis of gender did not show any significant effects on thought-probe response proportions or on overall RT measures of performance, nor a significant interaction with music-present/absent on these measures on the sustained-attention task. Thus, gender is not included in further analyses of these measures. This null result agrees with past research suggesting that there is no effect of gender on sustained attention (e.g., Chan, 2009 ).

27 of the participants had received previous formal musical training (voice or instrument) in a music school or private setting ( M = 6 years; Min. = 2 years; Max. = 21 years). Musical training was measured by asking participants whether they had had any previous musical training and if so, for how many years. Analysis of musical training did not show any significant effects on thought-probe response proportions or on overall RT measures of performance, nor a significant interaction with music-present/absent on these measures. Therefore, musical training is not analysed further here. Indeed, although there are previous studies that have shown an effect of musical training on sustained attention, they have not shown an interaction between training and the effect of background music (e.g., Darrow et al., 2006 ; Rodrigues, Loureiro, & Caramelli, 2013 ).

Pilot study

A pilot study was conducted to refine the thought-probe stimuli (see “ Materials” ). A different set of ten participants completed the pilot study, seven females and three males, who were all students at London-based universities.

Preferred background music

Participants were asked to send a 30-min long playlist containing their preferred background music tracks to the experimenter prior to participation in the study. There were no restrictions on the music, but participants were asked to send a playlist they would normally listen to when performing an attention-demanding task. The individual tracks could be of any length (mean track duration was 215.57 s) but together the playlist had to cover the full 30 min of the music-present session of the experiment. A few playlists were shorter than 30 min, because some participants decided to listen to their chosen tracks in repeat, as they would normally do in real-life settings. Musicological data for each track were collected from the database of the digital music streaming service called Spotify, using the Spotify Web API endpoints (Spotify 2018 ). This included data on tempo (overall tempo of a track in beats/minute; M = 112.56 BPM, SD = 32.37 BPM, range for individual tracks = 52.16–215.04 BPM), lyrics (i.e., a measure between 0.00 and 1.00 indicating the likelihood of a track containing any vocals at any given point during the track; tracks with a lower lyrics level were less likely to contain any vocal content; M = 0.59, SD = 0.57, range for individual tracks = 0.01–1.00), and genre. Genre categorisation for each track was based on Spotify’s main genre categories (Spotify 2018 ); because there was no specific genre categorisation available for individual tracks, genres describing the artist and the album in which the track appeared were used. Specifically, the most frequently occurring main genre was chosen for each track. Tracks that only had subgenre labels and not a clear main genre assigned to them were placed in the ‘other’ category.

Although some previous studies have shown that music preferences are influenced by gender, suggesting that males prefer “heavier” (Colley, 2008 ), more “vigorous” (Soares-Quadros Júnior, Lorenzo, Herrera, & Araújo Santos, 2019 ), and “intense-rebellious” music (Dobrota, Reić Ercegovac, & Habe, 2019 ) compared to females, in this study, there was no effect of gender on preferences for either tempo, lyrics, or genre.

Sustained attention task

The sustained-attention task was a variation of the Psychomotor Vigilance Task developed by Dinges and Powell ( 1985 ), which has long been used to measure sustained attention (Unsworth & Robison, 2016 ). As shown in Fig. 2 , participants were first presented with a fixation cross in the middle of the screen on a grey background for 2 s (s). Then, they saw a clock without any numbers, specifically a black circle containing a clock-hand at the 12-o’clock position and, after a variable wait time (equally distributed from 2 to 10 s in 500 ms increments), the clock-hand started moving clockwise in a smooth analogue fashion. The analogue clock was developed instead of the digital one used in previous experiments to make the task both applicable with populations with different/no number systems and also lower in cognitive demand. The task of the participants was to press the left mouse button as quickly as possible once the hand of the clock started moving. After the participant had pressed the mouse button, the clock remained on the screen for 1 s to provide feedback. Then, a 500-ms blank screen was presented, followed by either the next trial or a thought-probe. Participants completed 5 blocks, with 34 trials in each block, for both the music and no-music conditions. One block lasted approximately 6 min. Before starting the experiment, participants completed five practice trials to become familiar with the task.

Schematic representation of a single experimental trial with a thought-probe after the trial

During each block, participants were periodically presented with thought-probes. They were primed to respond to these probes by providing subjective reports to classify their immediately preceding thoughts. In all, they were presented with six thought-probes per block, after six randomly selected trials.

Thought-probes were refined in the pilot study based on participants’ feedback. Data obtained in the pilot study phase were not analysed or reported. Thought-probe statements, as specified below, were based on those used by Unsworth and Robison ( 2016 ). The original statements that were used by Unsworth and Robison ( 2016 ) are presented below:

“Please characterise your current conscious experience.

- I am totally focused on the current task.

- I am thinking about my performance on the task or how long it is taking.

- I am distracted by sights/sounds/temperature or by physical sensations (hungry/thirsty).

- I am daydreaming/my mind is wandering about things unrelated to the task.

- I am not very alert/my mind is blank or I’m drowsy.”

Some alterations were made compared to previous research based on feedback from the participants in the pilot study, to avoid ambiguous expressions that could refer to different concepts depending on one’s cultural background and understanding. More specifically, compared to the original five statements, only three statements were included in this study, namely those referring to mind-wandering, on-task thoughts/task-focus and external distraction, respectively (see the statements below). The term mind-wandering was left out of the phrasing of statement 1, and statements 2 and 3—referring to task-focus and external distraction—were simplified.

- I am tired, my mind is blank, or my thoughts are elsewhere.

- I am focused on the task or how I am doing it.

- I am thinking about the things around me (people, sights, sounds, the temperature) or about sensations in my body (hunger, thirst, pain).”

Apparatus and procedure

The present study was approved by the Psychology Department Ethics Committee at Goldsmiths, University of London on the 6th of June 2018. Participants were tested individually in the lab, in a dark and quiet room, and stimuli were presented on a 24-in. monitor with a 1920 × 1080 screen resolution.

Participants were asked not to do any heavy exercise or drink any caffeinated drinks 2–3 h prior to participation and to have a good night’s sleep involving at least 7–8 h sleep the night before. Prior to the day of the study, participants sent a 30-min long playlist with their preferred background tracks to the researcher. Background music was played continuously throughout the task in the music condition from a mobile device in “do not disturb” mode to avoid any distractions. Participants could either use their own headphones or a pair provided by the researcher to listen to the music. For the music-absent condition, the headphones were removed to increase ecological validity (given that participants would not normally wear headphones when completing a task in silence).

Upon first arrival in the lab at the start of the experiment, participants first read the information sheet and signed the consent form. Then, they received the task instructions and were presented with five practice trials before the first block in both the music-present and music-absent conditions. They had the opportunity to ask any questions throughout the practice trials.

The instructions they received for the practice trials also applied to the main task. First participants were instructed to look at the fixation cross in the centre of the screen before each trial. Then, it was explained to them that their tasks were (i) to stop the clock-hand in the clock-face in the middle of the screen as soon as the clock-hand started moving, by pressing the left mouse button; (ii) when presented with thought-probe statements after some of the trials, to choose the statement that best described their current conscious experience by pressing buttons 1, 2, or 3 on the keyboard.

The study took approximately 1 h and 30 min, during which time participants performed the sustained-attention task twice: once in silence (30 min) and once with their preferred music playing in the background (30 min). There were five blocks of trials in each condition. Each block was started individually by the experimenter, ensuring that there was a break for a few minutes between the blocks so that participants could rest and drink some water if they wished to. To control for carry-over effects of the music conditions, music conditions were counterbalanced and there was a 10-min break between the conditions in both orders. During the break, participants used a tablet to play a word spelling game called ‘Hi Words’ that was unrelated to the study. The game kept them engaged and helped them recover from the fatigue caused by the first condition (e.g., Jahncke, Hygge, Halin, Green, & Dimberg, 2011 ).

Once participants had finished the task, the researcher recorded their age, gender and whether they had had any previous formal music training and, if yes, for how many years. Then, the participants received the debriefing sheet and £5 for their participation.

Analyses were conducted on the effect of preferred background music both on the subjective measures of attention and behavioural measures of performance. The independent variables were music-present/absent, time-on-task (blocks 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5) and attentional-state category (mind-wandering, task-focus, external distraction). For the dependent variables, following Unsworth and Robison ( 2016 ), we examined: thought-probe response proportions of attentional-state category, mean RT (in ms) and standard deviation of RT (in ms). For the two RT analyses, some data points were removed, including any number below 100 ms (18 data points) based on Basner and Dinges’ ( 2011 ) suggestion that RTs below 100 ms count as false starts (errors of commission); moreover, any number above 5000 ms that exceeded the time required for the clock-hand to complete a full revolution was also removed (two data points).

Order of the music conditions (music-absent followed by music-present, or music-present followed by music-absent) did not show any significant effects on thought-probe response proportions, RT, or standard deviation of RT ( p ≥ 0.23), and there was no interaction between order and music-present/absent on these variables ( p ≥ 0.10); therefore, analyses were collapsed across order.

In all, four different analyses were conducted on thought-probe response proportions, RT, and standard deviation of RT. In the first analysis, a three-way repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the effect of attentional-state category, music-present/absent and time-on-task on thought-probe response proportions. In the second analysis, RT was analysed; however, based on Unsworth and Robison ( 2016 ), we anticipated having insufficient data to perform the corresponding three-way ANOVA. In other words, we anticipated having too many empty cells for RT response for trials associated with thought-probe statements as a consequence of participants not all reporting all attentional-state categories. Therefore, a separate linear-mixed-model analysis was used, which accounted for unequal sample sizes, to explore the effect of attentional-state category on RT as a check that the subjective reports are meaningful and express themselves in behaviour. The third analysis also focused on RT: it was a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA and was performed to analyse the effect of music presence/absence and time-on-task on RT. Finally, the fourth analysis focused on the standard deviation of RT: like the third, it was a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA conducted on the effect of music-present/absent and time-on-task, but this time on the standard deviation of RT.

At the end of the Results section, we report additional analyses on tempo, lyrics, and genre. These additional analyses should be treated as exploratory given that participants were free to select tracks that varied in tempo, lyrics, and genre. As a result, determining the values of these musicological parameters for each participant involved factoring in the proportion of time that the participant spent listening to tracks of varying tempo, lyrics, and genre.

The effect of music-present/absent, attentional-sate category, and time-on-task on thought-probe response proportions

To analyse the effect of background music on thought-probe response proportions, a 2 × 3 × 5 repeated-measures factorial ANOVA was conducted on music-present/absent, attentional-state category and time-on-task. Greenhouse–Geisser correction was used, because the sphericity assumption was violated, p < 0.02. There was a significant main effect of attentional-state category, F (1.66, 64.98) = 35.06, MSE = 21.64, p < 0.001, partial η 2 = 0.47, and a significant quadratic trend, F (1, 39) = 50.97, MSE = 35.98, p < 0.001, partial η 2 = 0.57. This shows that participants reported significantly more task-focus states ( M = 0.58, SD = 0.33) than mind-wandering ( M = 0.22, SD = 0.28) or external distraction states ( M = 0.20, SD = 0.24).

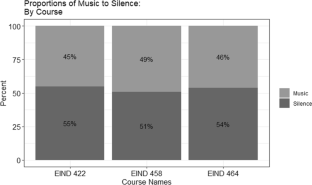

Importantly, there was also a significant interaction between music-present/absent and attentional-state category, F (1.45, 56.37) = 4.03, MSE = 0.98, p = 0.04, partial η 2 = 0.09, and a significant linear trend, F (1, 39) = 6.44, MSE = 0.46, p = 0.02, partial η 2 = 0.14. The simple effect analysis (paired-sample t tests) showed a significant difference between music-present and music-absent conditions in the proportion of both mind-wandering, t (199) = 4.24, p < 0.001, d = 0.30, and task-focus reports, t (199) = − 2.82, p = 0.005, d = 0.20, and a non-significant difference in external distraction reports, ( p = 0.72, d = 0.03). Specifically, there were significantly more mind-wandering reports in the music-absent condition ( M = 0.27, SD = 0.28) than in the music-present condition ( M = 0.18, SD = 0.28) and significantly more task-focus reports in the music-present condition ( M = 0.62, SD = 0.34) than in the music-absent condition ( M = 0.54, SD = 0.33), as seen in Fig. 3 .

Thought-probe response proportions as a function of attentional-state category and music-present/absent (music/no music). Error bars represent ± 1 standard error of the mean (S.E.M.)

Furthermore, the ANOVA also revealed a significant interaction between attentional-state category and time-on-task, F (5.00, 195.13) = 8.23, MSE = 0.90, p < 0.001, partial η 2 = 0.17, and a significant linear, F (1, 39) = 5.81, MSE = 0.55, p = 0.02, partial η 2 = 0.13, and quadratic trend, F (1, 39) = 25.05, MSE = 3.87, p < 0.001, partial η 2 = 0.39 (see Fig. 4 ).

Thought-probe response proportions as a function of time-on-task (block number). Error bars represent ± 1 S.E.M

The simple effect analysis (using paired-sample t tests with Bonferroni correction) on mind-wandering reports and time-on-task showed a significant difference in the proportion of mind-wandering reports between blocks 1–3 ( p = 0.003, d = 0.49), 1–4 ( p < 0.001, d = 0.72), 1–5 ( p < 0.001, d = 0.62), 2–4 ( p = 0.001, d = 0.57), and 2–5 ( p = 0.006, d = 0.46). A simple regression analysis demonstrated that, as block number increased, the proportion of mind-wandering reports also increased, F (1, 3) = 192.00, p = 0.001, R 2 = 0.99.

Moreover, the simple effect analysis (using paired-sample t tests with Bonferroni correction) on task-focus reports and time-on-task also showed a significant difference in the proportion of task-focus reports between blocks 1–3 ( p = 0.007, d = 0.45), 1–4 ( p < 0.001, d = 0.71), 1–5 ( p < 0.001, d = 0.70), 2–4 ( p < 0.001, d = 0.60), 2–5 ( p < 0.001, d = 0.64), 3–4 ( p = 0.004, d = 0.48) and 3–5 ( p = 0.005, d = 0.47). A simple regression analysis demonstrated that, as block number increased, the proportion of task-focus reports decreased, F (1, 3) = 294.00, p < 0.001, R 2 = 0.99.

The simple effect analysis (paired-sample t tests) on external distraction reports and time-on-task did not show any significant difference in the proportion of external distraction reports between blocks ( p ≥ 0.23, d ≤ 0.19).

Finally, the ANOVA revealed that there was not a significant 3-way interaction between music-present/absent, attentional-state category and time-on-task (p = 0.13).

The effect of attentional-sate category on reaction time

Because not all participants reported all of the attentional states, there were too many missing cases to perform a corresponding (three-way ANOVA) analysis on RT. Therefore, a separate linear-mixed-model analysis was performed on attentional-state category and RT, followed by a two-way ANOVA on the effect on RT of time-on-task and music-present/absent. Finally, a similar two-way ANOVA was performed on the effect of time-on-task and music-present/absent on the standard deviation of RT.

First, the relationship between attentional-state category and RT was examined to explore the correlation between subjective and behavioural measures. We expected that on-task (task-focus) states would be linked to faster reaction time than off-task states (mind-wandering and external distraction). Because four participants did not report mind-wandering and sample sizes were unequal (40 participants in the task-focus group, 40 in the external-distraction group, and 36 participants in the mind-wandering group), we performed linear-mixed-model analysis following Unsworth and Robison ( 2016 ). In the model, attentional-state category was entered as a fixed factor and subjects were entered as random factors. The linear-mixed-model analysis suggested that on-task reports were associated with significantly shorter RTs than mind-wandering reports, t (35.48) = 3.89, p < 0.001 ( b = 29.61, SE = 13.41), and also with significantly shorter RTs than external distraction reports, t (39) = − 4.39, p < 0.001 ( b = 21.71, SE = 20.68) (see Fig. 5 ).

Mean RT as a function of attentional-state category. Error bars represent ± 1 S.E.M

The Effect of music-present/absent and time-on-task on reaction time

Next, a 5 × 2 repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted on the effect of music-present/absent and time-on-task on RT. Greenhouse–Geisser correction was used for the effect of time-on-task, because the sphericity assumption was violated, p < 0.001. There was a significant main effect of time-on-task, F (1.44, 56.06) = 7.64, MSE = 17,793.34, p = 0.003, partial η 2 = 0.1 6, and a significant linear trend of time-on-task, F (1, 39) = 9.90, MSE = 19,464.16, p = 0.003, partial η 2 = 0.2 0. This means that RT became significantly slower as block number increased (see Fig. 6 ).

Mean RT as a function of time-on-task (block number) and music-present/absent (music/no music). Error bars represent ± 1 S.E.M

The ANOVA did not show a significant main effect of music-present/absent ( p = 0.12), nor a significant interaction between music-present/absent and time-on-task ( p = 0.46).

The Effect of music-present/absent and time-on-task on standard deviation of RT

In addition to analysing RTs, the standard deviations of RTs were also analysed in a separate 5 × 2 repeated-measures ANOVA on music-present/absent and time-on-task. Greenhouse–Geisser correction was used for the effect of time-on-task, because the sphericity assumption was violated p < 0.001. There was a significant main effect of time-on-task, F (2.01, 78.45) = 4.47, MSE = 19,177.63, p = 0.01, partial η 2 = 0.1 0, and a significant linear trend of time-on-task, F (1, 39) = 7.20, MSE = 164,885.83, p = 0.01, partial η 2 = 0.1 6. This suggests that not only did participants get slower across blocks, but they also became more variable in their responding as block number increased (see Fig. 7 ).

Standard deviation of RT as a function of time-on-task (block number) and music-present/absent (music/no music). Error bars represent ± 1 S.E.M

The ANOVA did again not show a significant main effect of music-present/absent ( p = 0.07), nor a significant interaction between music-present/absent and time-on-task ( p = 0.17).

The Effect of music tempo, lyrics, and genre on thought-probe response proportions, RT, and standard deviation of RT

The effects of tempo, lyrics, and genre were analysed on thought-probe response proportions, on mean RT, and on standard deviation of RT. Tempo was determined for each participant using the average value across tracks, weighted by the duration of each track ( M = 115.90 BPM, SD = 14.70 BPM, range = 91.32–160.02 BPM). Similarly, lyrics were determined for each participant using the average value across tracks, weighted by the duration of each track ( M = 0.64, SD = 0.36, range 0.07–1.00). For genre, each participant was assigned to the genre that made up the greatest proportion of time in their playlist (Fig. 8 ).

Each participant was assigned to the genre that made up the greatest proportion of time in their playlist. The graph represents the number of participants for each genre who listened to that genre for the greatest proportion of time. The ‘other’ category included tracks that could not be otherwise categorised, such as Japanese anime music, music for meditation, and some indie and folk tracks that did not clearly fit into a different main category. The ‘instrumental’ category included tracks that were primarily produced using musical instruments, such as remixes of original tracks, piano ‘lounge’ music, and ‘ambient’ music

The sample size for lyrics was 36 because the chosen playlists from four participants were not available on Spotify and, therefore, could not be analysed. The sample size for analyses of tempo was 35, because there was one outlier (with an average tempo of 160.02 BPM) which was excluded from the analyses. The sample size for the analyses of genre was 22, because we compared only the two most popular genres, operationalised as those that were listened to for the greatest proportion of time by the most participants (pop and instrumental).

Five separate simple regression analyses were conducted to see whether tempo can predict (i) proportions of mind-wandering reports, (ii) proportions of task-focus reports, (iii) proportions of external distraction reports, (iv) mean RT scores, and (v) standard deviation of RT. The regression models did not show any association between tempo and mind-wandering states ( p = 0.66), task-focus states ( p = 0.32), or external distraction states ( p = 0.36). Moreover, the regression models also did not show any association between tempo and mean RT ( p = 0.21), or tempo and standard deviation of RT ( p = 0.30).

Five separate simple regression analyses were conducted to see whether lyrics can predict (i) proportions of mind-wandering reports, (ii) proportions of task-focus reports, (iii) proportions of external distraction reports, (iv) mean RT scores, and (v) standard deviation of RT. The regression models did not show any association between lyrics and mind-wandering states ( p = 0.15), task-focus states ( p = 0.38), or external distraction states ( p = 0.69). Moreover, the regression models also did not show any association between lyrics and mean RT ( p = 0.98), or lyrics and standard deviation of RT ( p = 0.08).

Five separate Mann–Whitney U non-parametric tests were conducted to see whether genre (pop, instrumental) affects (i) proportions of mind-wandering reports, (ii) proportions of task-focus reports, (iii) proportions of external distraction reports, (iv) mean RT scores, and (v) standard deviation of RT. These non-parametric tests were chosen instead of independent t tests because of the unequal sample sizes: there were 17 participants in the pop, and 5 in the instrumental genre category. The Mann–Whitney U tests did not show any effect of genre on mind-wandering reports ( p = 0.16), task-focus reports ( p = 0.06), or external distraction reports ( p = 0.25). Moreover, there was no effect of genre on RT ( p = 0.88) or standard deviation of RT ( p = 0.14).

The goal of the present study was to explore how background music affects task-performance and attentional state on a simple sustained-attention task. This study was the first that has used subjective reports of attentional state (representative of the different regions of the inverted-U curve linking arousal to performance; Unsworth & Robison, 2016 ) to explore the effect of background music. The results provided evidence for our first and second hypotheses in which we predicted that background music would increase the proportions of task-focus states compared to silence, and on-task states (i.e., task-focus) would be linked to shorter RTs than off-task states (i.e., mind-wandering, external distraction). However, the third hypothesis was not supported by the results and background music did not affect RT.

As predicted in the first hypothesis, background music was shown to increase task-focus states compared to silence. Specifically, it was found that, while mind-wandering reports decreased, task-focus reports increased when music was playing in the background. Interestingly, all the increase in task-focus could be accounted for by the decrease in mind-wandering, and music did not affect external distraction. In addition, task-focus reports significantly decreased, and mind-wandering reports significantly increased, with time-on-task, suggesting that people were less able to sustain their attention on the task over time and their arousal dropped. These results are likely to be a consequence of the boringness of the sustained-attention task used in the current study, with the result that it made participants hypo-aroused, placing them at the lower end of the arousal axis on the inverted-U curve. As a consequence, the arousal-increase caused by the music led to an intermediate level of arousal, shifting the balance between task-focus and mind-wandering states, and not impacting external distraction states.

This is in line with explanations that the less complex the task, the more positive the influence of music can be expected to be (Anderson 1994 ; Gellatly & Meyer, 1992 ; North & Hargreaves, 1999 ). For example, the present finding is supported by previous research showing that performance is better with background music compared to silence on simple tasks (Ünal et al., 2013 ). Specifically, Ünal et al. ( 2013 ) used a monotonous lane-keeping task and showed that preferred background music increased heart rate and some aspects of driving performance (response latencies to changes in speed on the road, lateral control) compared to silence. Similarly, Fontaine and Schwalm ( 1979 ) found that, compared to unfamiliar background music and silence, familiar music increased participants’ heart rate and correct detections on a simple vigilance task.

Familiar background music has also been linked to less frequent mind-wandering episodes and faster RTs than unfamiliar music by Feng and Bidelman ( 2015 ). They explored how familiar classical and unfamiliar classical music in the background affects mind-wandering on a lexical congruity task and found that familiar music was associated with faster response times and less frequent mind-wandering episodes than unfamiliar music. Feng and Bidelman ( 2015 ) suggested that the more positive effect of familiar music could have been a result of its familiarity increasing emotional arousal and pleasure, and in turn decreasing stress. However, they did not compare the effect of music to silence, nor did they focus on a sustained-attention task (Feng & Bidelman, 2015 ). Because preferred music is almost always familiar to the listener, these previous results showing a positive effect of familiar background music support the potential of preferred background music to enhance task-focused attention, as found in this study.

These past findings and the present results are compatible with the idea that the effect of background music is mediated by arousal. This idea has been raised by North and Hargreaves ( 1999 ), who discussed two possible frameworks—the arousal framework and the cognitive-load framework—that could potentially explain the effect of background music on performance. In terms of the arousal framework already outlined above, when presented with a very simple task, background music should increase arousal to an optimal/intermediate level and, thus, increase performance. Contrarily, in terms of the cognitive-load framework, if the music takes up cognitive space, then it should impair performance even on very simple tasks because it decreases the cognitive space available for the task. The current study provided evidence for the arousal framework because it showed that background music improved performance, specifically by increasing the ratio of task-focus states compared to mind-wandering states which is compatible with an increase in arousal to levels that are optimal for performance.

The results presented here also provided evidence for our second hypothesis, which predicted that states of task-focus will be linked to shorter RTs than off-task states of mind-wandering and external distraction. Therefore, our study was successful in replicating the result by Unsworth and Robison ( 2016 ) showing that on-task states are associated with shorter RTs than off-task states. This result shows that there is a link between subjective and behavioural measures of attentional state and that subjective reports provide valid, meaningful measures of attentional state that express themselves in behaviour.

Our third hypothesis was the only one not supported by the results of the main analyses: background music did not exert effects on either RT or variability of RT. In other words, even though music enhanced task-focus and task-focus was linked to shorter RT, music did not produce an overall significant reduction in RT compared to silence. The predicted effects of music on RT time-on-task effects were also not present. This was despite RT and variability in responding increasing with time-on-task—along with task-focus reports decreasing and mind-wandering reports increasing—indicating that people did become fatigued (Unsworth & Robison, 2016 ). The absence of any effect in the present study of background music on time-on-task effects—either on subjective report or RT data—suggests that background music does not make a difference to how fatigued people become. These findings are consistent with a study by Burkhard et al. ( 2018 ) that found that background music increased arousal but did not affect performance on a sustained-attention task.