ARTS & CULTURE

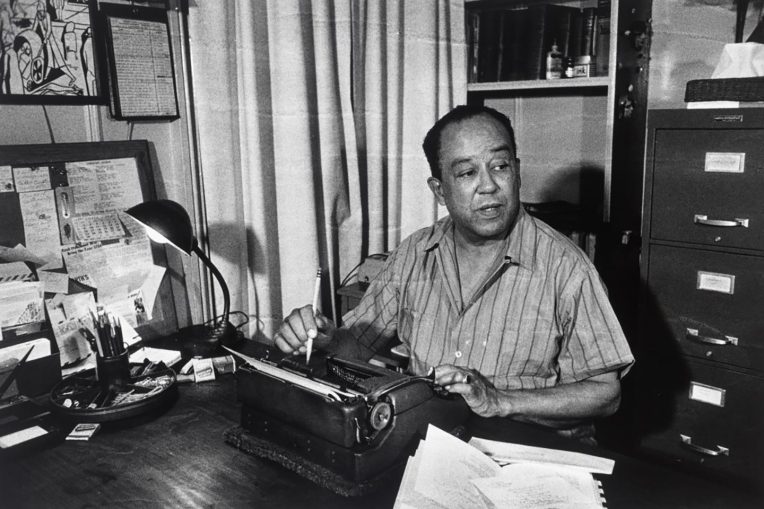

A lost work by langston hughes examines the harsh life on the chain gang.

In 1933, the Harlem Renaissance star wrote a powerful essay about race. It has never been published in English—until now

Steven Hoelscher

:focal(323x236:324x237)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/71/a8/71a8b7f6-40a7-48fc-ad74-025fc06eebf6/hughes-opener-letterboxed.jpg)

It’s not every day that you come across an extraordinary unknown work by one of the nation’s greatest writers. But buried in an unrelated archive I recently discovered a searing essay condemning racism in America by Langston Hughes—the moving account, published in its original form here for the first time, of an escaped prisoner he met while traveling with Zora Neale Hurston.

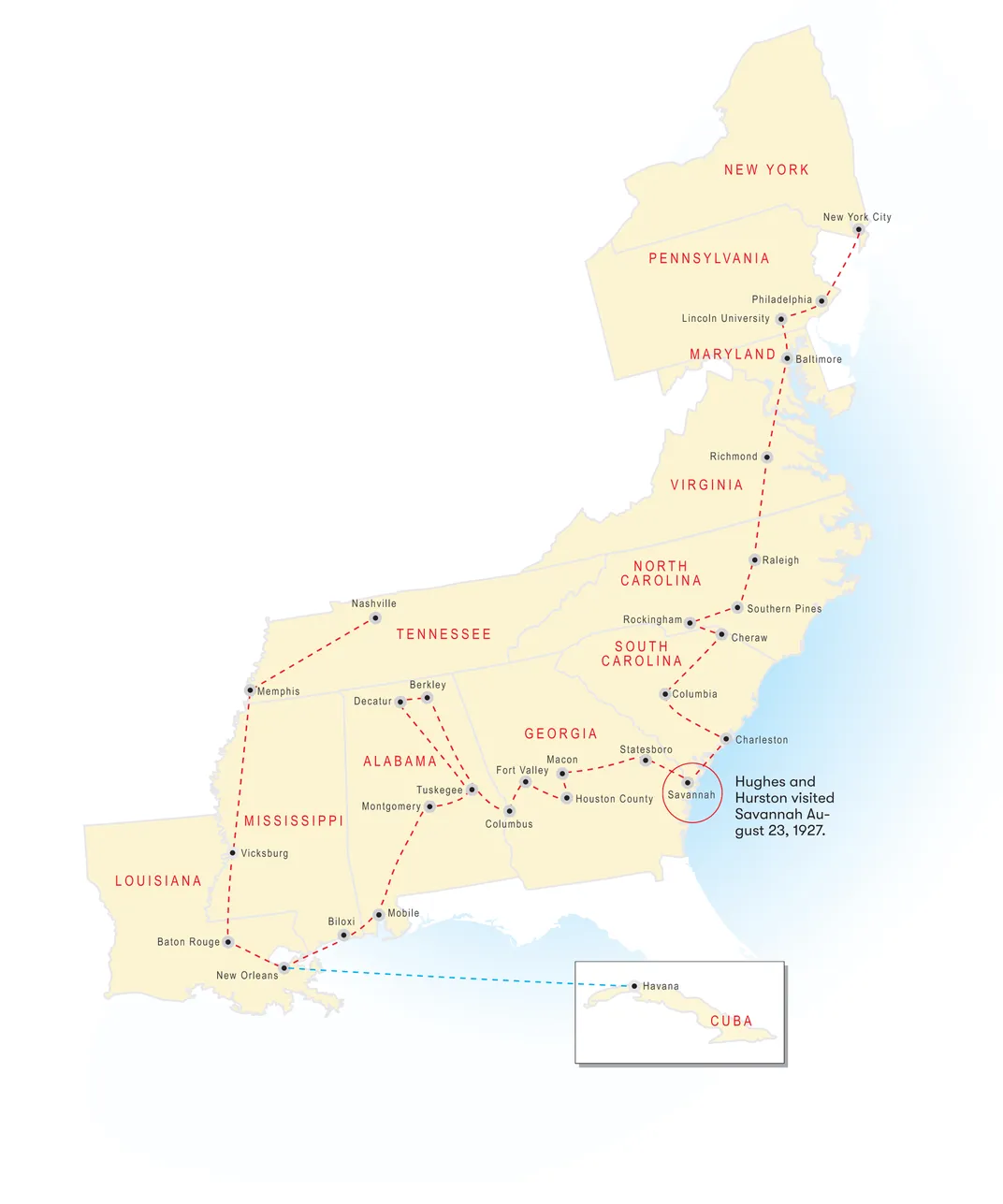

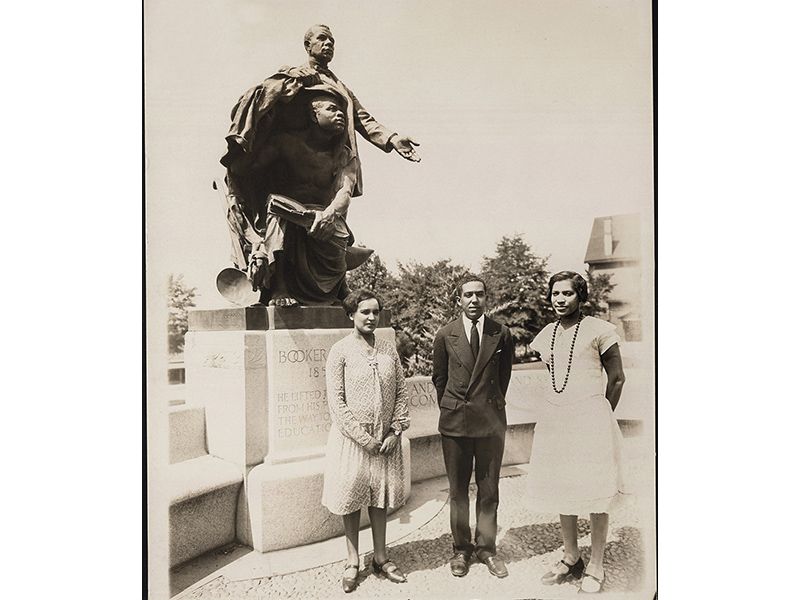

In the summer of 1927, Hughes lit out for the American South to learn more about the region that loomed large in his literary imagination. After giving a poetry reading at Fisk University in Nashville, Hughes journeyed by train through Louisiana and Mississippi before disembarking in Mobile, Alabama. There, to his surprise, he ran into Hurston, his friend and fellow author. Described by Yuval Taylor in his new book Zora and Langston as “one of the more fortuitous meetings in American literary history,” the encounter brought together two leading lights of the Harlem Renaissance. On the spot, the pair decided to drive back to New York City together in Hurston’s small Nash coupe.

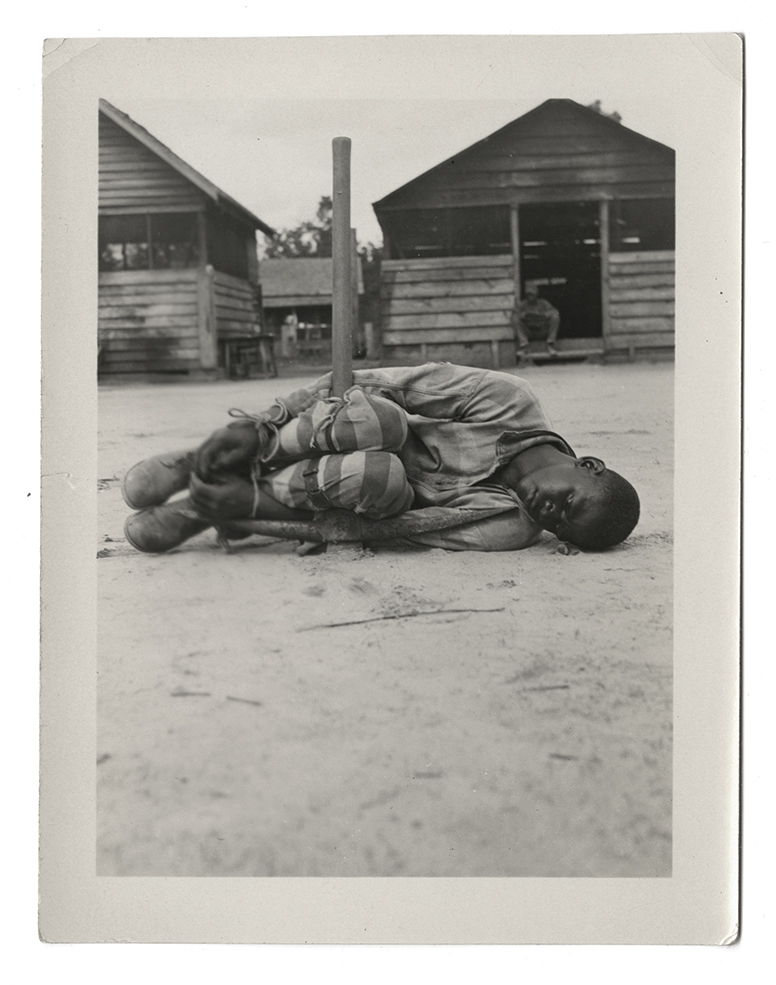

The terrain along the back roads of the rural South was new to Hughes, who grew up in the Midwest; by contrast, Hurston’s Southern roots and training as a folklorist made her a knowledgeable guide. In his journal Hughes described the black people they met in their travels: educators, sharecropping families, blues singers and conjurers. Hughes also mentioned the chain gang prisoners forced to build the roads they traveled on.

A Literary Road Trip

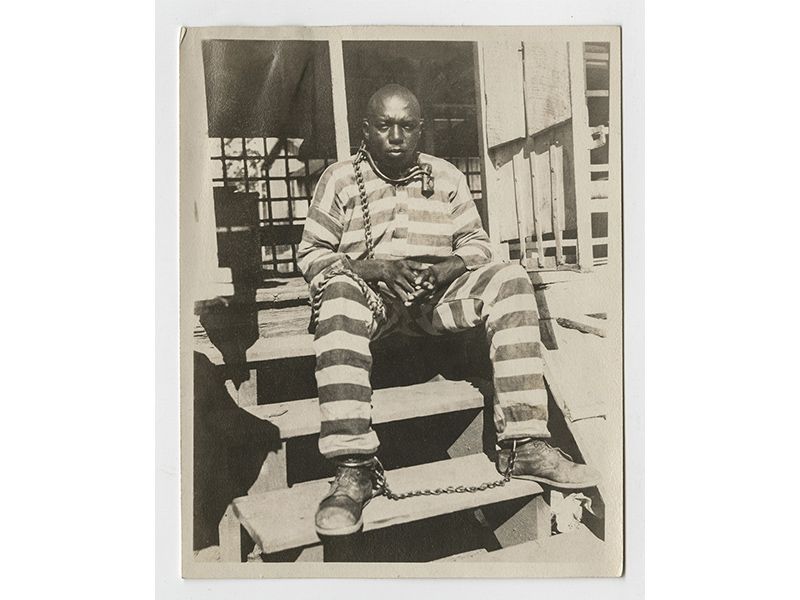

Three years later, Hughes gave the poor, young and mostly black men of the chain gangs a voice in his satirical poem “Road Workers”—but we now know that the images of these men in gray-and-black-striped uniforms continued to linger in the mind of the writer. In this newly discovered manuscript, Hughes revisited the route he traveled with Hurston, telling the story of their encounter with one young man picked up for fighting and sentenced to hard labor on the chain gang.

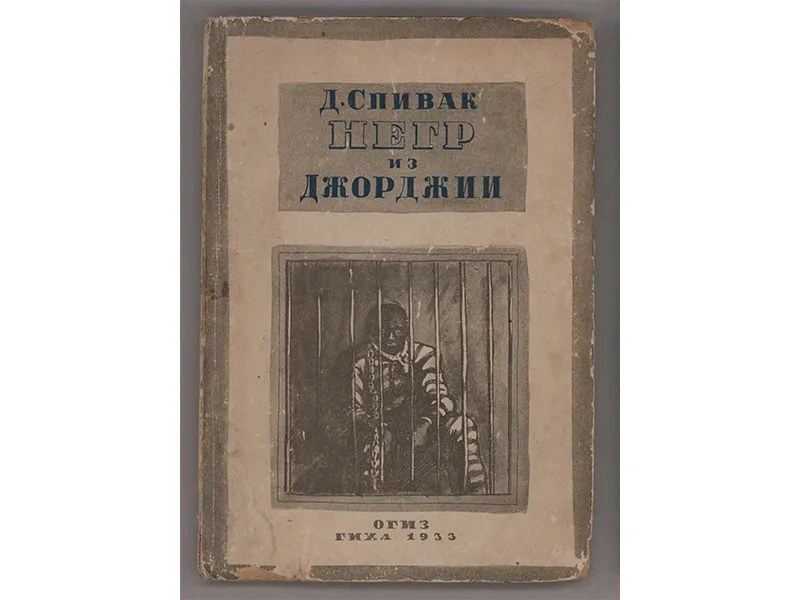

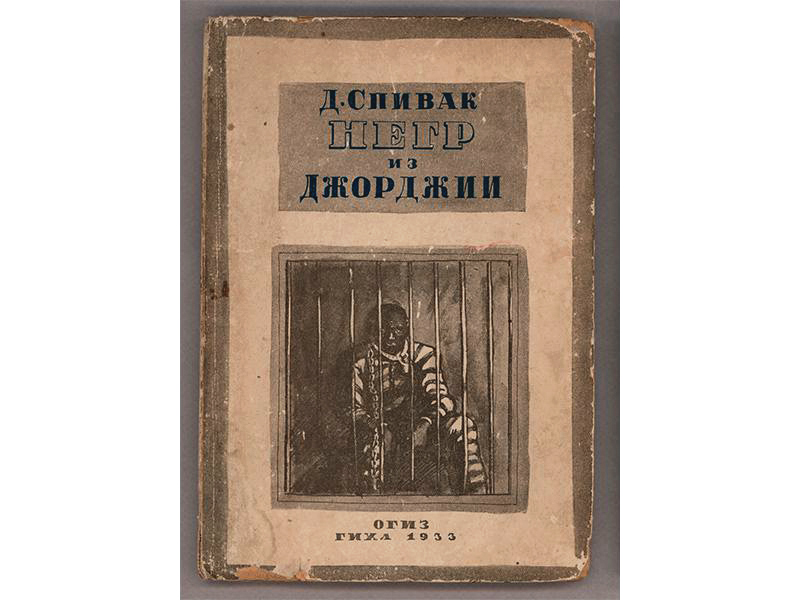

I first stumbled upon this Hughes essay in the papers of John L. Spivak, a white investigative journalist in the 1920s and 1930s, at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Not even Hughes’ authoritative biographer Arnold Rampersad could identify the manuscript. Eventually, I learned that Hughes had written it as an introduction to a novel Spivak published in 1932, Georgia Nigger . The book was a blistering exposé of the atrocious conditions that African-Americans suffered on chain gangs, and Spivak gave it a deliberately provocative title to reflect the brutality he saw. Scholars today consider the forced labor system a form of slavery by another name. On the final page of the manuscript (not reproduced here), Hughes wrote that by “blazing the way to truth,” Spivak had written a volume “of great importance to the Negro peoples.”

Hughes titled these three typewritten pages “Foreword From Life.” And in them he also laid bare his fears of driving through Jim Crow America. “We knew that it was dangerous for Northern Negroes to appear too interested in the affairs of the rural South,” he wrote. (Hurston packed a chrome-plated pistol for protection during their road trip.)

But a question remained: Why wasn’t Hughes’ essay included in any copy of Spivak’s book I had ever seen? Buried in Spivak’s papers, I found the answer. Hughes’ essay was written a year after the book was published, commissioned to serve as the foreword of the 1933 Soviet edition and published only in Russian.

In early 1933, Hughes was living in Moscow, where he was heralded as a “revolutionary writer.” He had originally traveled there a year earlier along with 21 other influential African-Americans to participate in a film about American racism. The film had been a bust (no one could agree on the script), but escaping white supremacy in the United States—at least temporarily—was immensely appealing. The Soviet Union, at that time, promoted an ideal of racial equality that Hughes longed for. He also found that he could earn a living entirely from his writing.

For this Russian audience, Hughes reflected on a topic as relevant today as it was in 1933: the injustice of black incarceration. And he captured the story of a man that—like the stories of so many other young black men—would otherwise be lost. We may even know his name: Hughes’ journal mentions one Ed Pinkney, a young escapee whom Hughes and Hurston met near Savannah. We don’t know what happened to him after their interaction. But by telling his story, Hughes forces us to wonder.

Foreword From Life

By Langston Hughes

I had once a short but memorable experience with a fugitive from a chain gang in this very same Georgia of which [John L.] Spivak writes. I had been lecturing on my poetry at some of the Negro universities of the South and, with a friend, I was driving North again in a small automobile. All day since sunrise we had been bumping over the hard red clay roads characteristic of the backward sections of the South. We had passed two chain gangs that day This sight was common. By 1930 in Georgia alone, more than 8,000 prisoners, mostly black men, toiled on chain gangs in 116 counties. The punishment was used in Georgia from the 1860s through the 1940s. , one in the morning grading a country road, and the other about noon, a group of Negroes in gray and black stripped [sic] suits, bending and rising under the hot sun, digging a drainage ditch at the side of the highway. Adopting the voice of a chain gang laborer in the poem “Road Workers,” published in the New York Herald Tribune in 1930, Hughes wrote, “Sure, / A road helps all of us! / White folks ride — /And I get to see ’em ride.” We wanted to stop and talk to the men, but we were afraid. The white guards on horseback glared at us as we slowed down our machine, so we went on. On our automobile there was a New York license, and we knew it was dangerous for Northern Negroes to appear too interested in the affairs of the rural South. Even peaceable Negro salesmen had been beaten and mobbed by whites who objected to seeing a neatly dressed colored person speaking decent English and driving his own automobile. The NAACP collected reports of violence against blacks in this era, including a similar incident in Mississippi in 1925. Dr. Charles Smith and Myrtle Wilson were dragged from a car, beaten and shot. The only cause recorded: “jealousy among local whites of the doctor’s new car and new home.” So we did not stop to talk to the chain gangs as we went by.

But that night a strange thing happened. After sundown, in the evening dusk, as we were nearing the city of Savannah, we noticed a dark figure waving at us frantically from the swamps at the side of the road. We saw that it was a black boy.

“Can I go with you to town?” the boy stuttered. His words were hurried, as though he were frightened, and his eyes glanced nervously up and down the road.

“Get in,” I said. He sat between us on the single seat.

“Do you live in Savannah?” we asked.

“No, sir,” the boy said. “I live in Atlanta.” We noticed that he put his head down nervously when other automobiles passed ours, and seemed afraid.

“And where have you been?” we asked apprehensively.

“On the chain gang,” he said simply.

We were startled. “They let you go today?” In his journal, Hughes wrote about meeting an escaped convict named Ed Pinkney near Savannah. Hughes noted that Pinkney was 15 years old when he was sentenced to the chain gang for striking his wife.

“No, sir. I ran away. In his journal, Hughes wrote about meeting an escaped convict named Ed Pinkney near Savannah. Hughes noted that Pinkney was 15 years old when he was sentenced to the chain gang for striking his wife. That’s why I was afraid to walk in the town. I saw you-all was colored and I waved to you. I thought maybe you would help me.”

Gradually, before the lights of Savannah came in sight, in answer to our many questions, he told us his story. Picked up for fighting, prison, the chain gang. But not a bad chain gang, he said. They didn’t beat you much in this one. Guard-on-convict violence was pervasive on Jim Crow-era chain gangs. Inmates begged for transfers to less violent camps but requests were rarely granted. “I remembered the many, many such letters of abuse and torture from ‘those who owed Georgia a debt,’” Spivak wrote. Only once the guard had knocked two teeth out. That was all. But he couldn’t stand it any longer. He wanted to see his wife in Atlanta. He had been married only two weeks when they sent him away, and she needed him. He needed her. So he had made it to the swamp. A colored preacher gave him clothes. Now, for two days, he hadn’t eaten, only running. He had to get to Atlanta.

“But aren’t you afraid,” [w]e asked, “they might arrest you in Atlanta, and send you back to the same gang for running away? Atlanta is still in the state of Georgia. Come up North with us,” we pleaded, “to New York where there are no chain gangs, and Negroes are not treated so badly. Then you’ll be safe.”

He thought a while. When we assured him that he could travel with us, that we would hide him in the back of the car where the baggage was, and that he could work in the North and send for his wife, he agreed slowly to come.

“But ain’t it cold up there?” he said.

“Yes,” we answered.

In Savannah, we found a place for him to sleep and gave him half a dollar for food. “We will come for you at dawn,” we said. But when, in the morning we passed the house where he had stayed, we were told that he had already gone before daybreak. We did not see him again. Perhaps the desire to go home had been greater than the wish to go North to freedom. Or perhaps he had been afraid to travel with us by daylight. Or suspicious of our offer. Or maybe [...] In the English manuscript, the end of Hughes’ story about the convict trails off with an incomplete thought—“Or maybe”—but the Russian translation continues: “Or maybe he got scared of the cold? But most importantly, his wife was nearby!”

Reprinted by permission of Harold Ober Associates. Copyright 1933 by the Langston Hughes Estate

Get the latest Travel & Culture stories in your inbox.

Steven Hoelscher | READ MORE

Steven Hoelscher is a professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Langston Hughes

By: History.com Editors

Updated: December 15, 2023 | Original: January 24, 2023

Langston Hughes was a defining figure of the 1920s Harlem Renaissance as an influential poet, playwright, novelist, short story writer, essayist, political commentator and social activist. Known as a poet of the people, his work focused on the everyday lives of the Black working class, earning him renown as one of America’s most notable poets.

Hughes was born February 1, 1902 (although some evidence shows it may have been 1901 ), in Joplin, Missouri, to James and Caroline Hughes. When he was a young boy, his parents divorced, and, after his father moved to Mexico, and his mother, whose maiden name was Langston, sought work elsewhere, he was raised by his grandmother, Mary Langston, in Lawrence, Kansas. Mary Langston died when Hughes was around 12 years old, and he relocated to Illinois to live with his mother and stepfather. The family eventually landed in Cleveland.

According to the first volume of his 1940 autobiography, The Big Sea , which chronicled his life until the age of 28, Hughes said he often used reading to combat loneliness while growing up. “I began to believe in nothing but books and the wonderful world in books—where if people suffered, they suffered in beautiful language, not in monosyllables, as we did in Kansas,” he wrote.

In his Ohio high school, he started writing poetry, focusing on what he called “low-down folks” and the Black American experience. He would later write that he was influenced at a young age by Carl Sandburg, Walt Whitman and Paul Laurence Dunbar. Upon graduating in 1920, he traveled to Mexico to live with his father for a year. It was during this period that, still a teenager, he wrote “ The Negro Speaks of Rivers ,” a free-verse poem that ran in the NAACP ’s The Crisis magazine and garnered him acclaim. It read, in part:

“I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.”

Traveling the World

Hughes returned from Mexico and spent one year studying at Columbia University in New York City . He didn’t love the experience, citing racism, but he became immersed in the burgeoning Harlem cultural and intellectual scene, a period now known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Hughes worked several jobs over the next several years, including cook, elevator operator and laundry hand. He was employed as a steward on a ship, traveling to Africa and Europe, and lived in Paris, mingling with the expat artist community there, before returning to America and settling down in Washington, D.C. It was in the nation’s capital that, while working as a busboy, he slipped his poetry to the noted poet Vachel Lindsay, cited as the father of modern singing poetry, who helped connect Hughes to the literary world.

Hughes’ first book of poetry, The Weary Blues was published in 1926, and he received a scholarship to and, in 1929, graduated from, Pennsylvania’s Lincoln University. He soon published Not Without Laughter , his first novel, which was awarded the Harmon Gold Medal for literature.

Jazz Poetry

Called the “Poet Laureate of Harlem,” he is credited as the father of jazz poetry, a literary genre influenced by or sounding like jazz, with rhythms and phrases inspired by the music.

“But jazz to me is one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America; the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul—the tom-tom of revolt against weariness in a white world, a world of subway trains, and work, work, work; the tom-tom of joy and laughter, and pain swallowed in a smile,” he wrote in the 1926 essay, “ The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain .”

Writing for a general audience, his subject matter continued to focus on ordinary Black Americans. Hughes wrote that his 1927 work, “Fine Clothes to the Jew,” was about “workers, roustabouts, and singers, and job hunters on Lenox Avenue in New York, or Seventh Street in Washington or South State in Chicago—people up today and down tomorrow, working this week and fired the next, beaten and baffled, but determined not to be wholly beaten, buying furniture on the installment plan, filling the house with roomers to help pay the rent, hoping to get a new suit for Easter—and pawning that suit before the Fourth of July."

He also did not shy from writing about his experiences and observations.

“We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame,” he wrote in the The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain . “If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too.”

Ever the traveler, Hughes spent time in the South, chronicling racial injustices, and also the Soviet Union in the 1930s, showing an interest in communism . (He was called to testify before Congress during the McCarthy hearings in 1953.)

In 1930, Hughes wrote “Mule Bone” with Zora Neale Hurston , his first play, which would be the first of many. “Mulatto: A Tragedy of the Deep South,” about race issues, was Broadway’s longest-running play written by a Black author until Lorraine Hansberry’s 1958 play, “A Raisin in the Sun.” Hansberry based the name of her play on Hughes’ 1951 poem, “ Harlem ” in which he writes,

"What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?...”

Hughes wrote the lyrics for “Street Scene,” a 1947 Broadway musical, and set up residence in a Harlem brownstone on East 127th Street. He co-founded the New York Suitcase Theater, as well as theater troupes in Los Angeles and Chicago. He attempted screenwriting in Hollywood, but found racism blocked his efforts.

He worked as a newspaper war correspondent in 1937 for the Baltimore Afro American , writing about Black American soldiers fighting for the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War . He also wrote a column from 1942-1962 for the Chicago Defender , a Black newspaper, focusing on Jim Crow laws and segregation , World War II and the treatment of Black people in America. The column often featured the fictitious Jesse B. Semple, known as Simple.

In the 1950s and ’60s, Hughes wrote a “First Book” series of children's books, patriotic stories about Black culture and achievements, including The First Book of Negroes (1952), The First Book of Jazz (1955), and The Book of Negro Folklore (1958). Among the stories in the 1958 volume is "Thank You, Ma'am," in which a young teenage boy learns a lesson about trust and respect when an older woman he tries to rob ends up taking him home and giving him a meal.

Hughes died in New York from complications during surgery to treat prostate cancer on May 22, 1967, at the age of 65. His ashes are interred in Harlem’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. His Harlem home was named a New York landmark in 1981, and a National Register of Places a year later.

"I, too, am America," a quote from his 1926 poem, " I, too, " is engraved on the wall of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

“ Langston Hughes ,” The Library of Congress

“ Langston Hughes: The People's Poet ,” Smithsonian Magazine

“ The Blues and Langston Hughes ,” Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

“ Langston Hughes ,” Poets.org

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Langston Hughes

Introduction, general overviews.

- Bibliographies and Other Reference Works

- Biographies

- Correspondence

- Special Journal Issues

- Collections

- Autobiographies

- Short Fiction

- Translations by Hughes

- Hughes in Translation

- Texts of Hughes’s McCarthy Testimonies

- Hughes, Diaspora, and Black Internationalism

- Hughes and Modernism

- Hughes as Political Writer

- Hughes, Gender, and Sexuality

- Film, Television, and Internet Resources

- Musical Adaptations

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- African American Vernacular Tradition

- American Literary Biography

- Claude McKay

- Countee Cullen

- James Weldon Johnson

- Proletarian Literature

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Lorraine Hansberry

- Mary Boykin Chesnut

- Phillis Wheatley Peters

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Langston Hughes by Vera Kutzinski LAST REVIEWED: 10 January 2022 LAST MODIFIED: 23 June 2023 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199827251-0026

Born James Langston Hughes in Joplin, Missouri, Langston Hughes (b. 1902–d. 1967) was likely the most influential writer who emerged from the Harlem Renaissance. He was the first one of this group to establish an enduring national and international reputation. Hughes established his national standing as the “Poet Laureate of the Negro Race” with The Weary Blues and the controversial essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain” in 1926. By the time he graduated from Lincoln University, Pennsylvania, in 1929, he had published a second volume of poems, Fine Clothes to the Jew (1927). Having lived in Mexico for more than a year as a teenager, by 1929 Hughes had also visited West Africa, France (where he spent several months), and Italy. Extended trips to Haiti, Cuba, the Soviet Union, and Spain followed, as did translations of his poems into Spanish, German, French, Russian, and many other languages. Though best known as a poet, Hughes was a prolific and versatile writer working in numerous literary genres as well as in journalism and popular history. Widely celebrated for his blues poetry and, more recently, for his experimental poems from the 1950s and early 1960s, Hispanic American audiences in particular praised Hughes for his verse influenced by international communism. However, this radical verse landed him in serious trouble at home. In the 1940s and 1950s, Hughes became the target of smear campaigns and FBI surveillance. Although Hughes disavowed his political past in his 1953 publicly broadcast testimony before Joseph McCarthy’s infamous Senate subcommittee, a measure of unease about his communist leanings has lingered in Hughes scholarship in the United States, where his radical poetry from the 1930s has traditionally had relatively few admirers—until now. Ironically, the very simplicity that made his writing accessible to and popular with so many different audiences across the world also fueled the belief among many scholars that Hughes’s writing lacked literary complexity. As a result, neither his novels nor his autobiographies have met with abundant critical analysis, much less acclaim. Quite in contrast to Hughes’s short fiction, especially the Simple stories from the 1940s and 1950s, these texts have attracted the critical attention they deserve only since the third quarter of the twentieth century, and especially in the early twenty-first century. Similarly, scholars have neglected Hughes’s plays, his translations of writers such as Federico García Lorca and Jacques Roumain, and his extensive journalism. Since the mid-1990s, however, the landscape of Hughes studies has changed significantly as scholars have increasingly challenged the view of Hughes as a straightforward and even shallow writer. It is changing even more in the twenty-first century.

Fewer scholarly monographs on Hughes are available than one might expect, given the length of his career and the sheer volume of writing he produced. Comprehensive studies of Hughes’s writings are even rarer because of the difficulty of doing justice to Hughes’s multi-genre oeuvre. With the exception of Emanuel 1967 (cited under Biographies ) and Barksdale 1977 (cited under Criticism: Poetry ), critical overviews of Hughes’s work have thus taken the shape of essay collections. Most valuable among the essay collections are O’Daniel 1971 , Tracy 2004 , Tidwell and Ragar 2007 , Miller 2013 , and Kutzinski and Reed 2023 , all of which offer original scholarship rather than reprints. Collections of reprints, such as Bloom 1989 and especially Bloom 2008 , are starting to outlive their usefulness at a time when most journal publications are available in full-text digital formats online. Although technically a reference work, De Santis 2005 (cited under Bibliographies and Other Reference Works ) provides by far the most effective historical overview of Hughes’s life and work, through a collage of documents rather than a more linear and univocal scholarly narrative.

Bloom, Harold, ed. Langston Hughes . Modern Critical Views. New York: Chelsea House, 1989.

Reprints twelve rather brief critical essays by well-established Hughes scholars, arranged chronologically from 1968 to 1985. This historical overview of Hughes criticism is still useful for graduates and undergraduates.

Bloom, Harold, ed. Langston Hughes . New ed. Bloom’s Modern Critical Views. New York: Bloom’s Literary Criticism, 2008.

Reprints of eleven chronologically organized essays (1986–2006) that supplement Bloom 1989 . Includes Ford 1992 (cited under Criticism: Short Fiction ), Thomas 1998 (cited under Criticism: Novels ), Patterson 2000 (cited under Hughes and Modernism ), and Tracy 2002 (cited under Criticism: Juvenilia ). Available as e-book.

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr., and Kwame Anthony Appiah, eds. Langston Hughes: Critical Perspectives Past and Present . Amistad Literary Series. New York: Amistad, 1993.

Offers nine essays by known Hughes scholars such as Arnold Rampersad, Steven Tracy, Richard Barksdale, and R. Baxter Miller, alongside reprinted reviews of Hughes’s work by Countee Cullen, Jessie Fauset, Richard Wright, James Baldwin, and others, a more complete gathering of which is available in Dace 1997 (cited under Bibliographies and Other Reference Works ).

Kutzinski, Vera M., and Anthony Reed, eds. Langston Hughes in Context . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2023.

The twenty-nine chapters in this collection variously explore Hughes’s conflicting-at-times attitudes toward populist and modernist literatures, his investments in race and in freedom within and beyond the United States, and the many genres in which he wrote. Together, these previous unpublished essays by new and established Hughes scholars showcase contemporary approaches to Hughes’s writings, offering comprehensive and nuanced views of the places and experiences that shaped Hughes; the social, political, and cultural contexts in which he wrote, thought, and travelled; and the international networks through which he forged and secured his life and reputation. The global scope of this collection is unparalleled. A very useful introduction to Hughes at home and abroad.

Miller, R. Baxter, ed. Critical Insights: Langston Hughes . Ipswich, MA: Salem, 2013.

A collection of sixteen previously unpublished essays remarkable for the combined breadth of coverage of the critical reception of Hughes’s work in the United States and Latin America, his portrayal of women and families, his politics, and his depictions of racial violence. A pricey volume, but it includes online access.

Mullen, Edward J., ed. Critical Essays on Langston Hughes . Critical Essays on American Literature. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1986.

Mainly a collection of reprints that, like Gates and Appiah 1993 , includes reviews of Hughes’s books, along with twelve articles (three of them new) to show the evolution of Hughes criticism since the 1920s. The introduction covers the reception of Hughes’s poetry, prose, and drama and outlines key debates.

O’Daniel, Therman B., ed. Langston Hughes, Black Genius: A Critical Evaluation . New York: William Morrow, 1971.

A historic collection of fourteen early essays that include contributions by the editor, Arthur P. Davis, Darwin Turner (on Hughes as playwright), Blyden Jackson (on the Simple stories), James Emanuel (on Hughes’s experimental poetry and his short fiction), Matheus 1968 (cited under Criticism: Translations by Hughes ), and George Kent (on Hughes and the African American folk tradition).

Tidwell, John Edgar, and Cheryl R. Ragar, eds. Montage of a Dream: The Art and Life of Langston Hughes . Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2007.

The eighteen contributions to this volume include new essays on Hughes’s plays, his works for children, his political poetry, Carrie Hughes Clark’s letters ( Williams and Williams 2007 , cited under Biographies ), gender and sexuality ( Baldwin 2007 , cited under Criticism: Short Fiction ; Banks 2007 , cited under Criticism: Novels ; and Schultz 2002 , also cited under Criticism: Novels ), and Hughes as Hollywood screenwriter ( Cripps 2007 , cited under Film, Television, and Internet Resources ).

Tracy, Steven C., ed. A Historical Guide to Langston Hughes . Historical Guides to American Authors. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

A well-conceived introduction to Hughes and his work that is suitable for undergraduate courses. Includes an informative introduction, a brief biography, a bibliographical essay, and four additional essays on literary uses of place, African American vernacular music, gender-racial issues, and Hughes as a social poet.

Trotman, C. James, ed. Langston Hughes: The Man, His Art, and His Continuing Influence . Papers presented 26–28 March 1992 at Lincoln University, Pennsylvania. Critical Studies on Black Life and Culture 29. New York: Routledge, 2014.

Conference proceedings originally published in 1995. Included are fifteen essays and a photo section. Featured topics include blues and blues poetry and the representation of women in Hughes’s writings. Includes a rare essay on the poems Hughes contributed to Carl Van Vechten’s novel Nigger Heaven (1926).

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About American Literature »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Adams, Alice

- Adams, Henry

- Agee, James

- Alcott, Louisa May

- Alexie, Sherman

- Alger, Horatio

- American Exceptionalism

- American Grammars and Usage Guides

- American Literature and Religion

- American Magazines, Early 20th-Century Popular

- "American Renaissance"

- American Revolution, Music of the

- Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones)

- Anaya, Rudolfo

- Anderson, Sherwood

- Angel Island Poetry

- Antin, Mary

- Anzaldúa, Gloria

- Austin, Mary

- Baldwin, James

- Barlow, Joel

- Barth, John

- Bellamy, Edward

- Bellow, Saul

- Bible and American Literature, The

- Bishop, Elizabeth

- Bourne, Randolph

- Bradford, William

- Bradstreet, Anne

- Brockden Brown, Charles

- Brooks, Van Wyck

- Brown, Sterling

- Brown, William Wells

- Butler, Octavia

- Byrd, William

- Cahan, Abraham

- Callahan, Sophia Alice

- Captivity Narratives

- Cather, Willa

- Cervantes, Lorna Dee

- Chesnutt, Charles Waddell

- Child, Lydia Maria

- Chopin, Kate

- Cisneros, Sandra

- Civil War Literature, 1861–1914

- Clark, Walter Van Tilburg

- Connell, Evan S.

- Cooper, Anna Julia

- Cooper, James Fenimore

- Copyright Laws

- Crane, Stephen

- Creeley, Robert

- Cruz, Sor Juana Inés de la

- Cullen, Countee

- Culture, Mass and Popular

- Davis, Rebecca Harding

- Dawes Severalty Act

- de Burgos, Julia

- de Crèvecœur, J. Hector St. John

- Delany, Samuel R.

- Dick, Philip K.

- Dickinson, Emily

- Doctorow, E. L.

- Douglass, Frederick

- Dreiser, Theodore

- Dubus, Andre

- Dunbar, Paul Laurence

- Dunbar-Nelson, Alice

- Dune and the Dune Series, Frank Herbert’s

- Eastman, Charles

- Eaton, Edith Maude (Sui Sin Far)

- Eaton, Winnifred

- Edwards, Jonathan

- Eliot, T. S.

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo

- Environmental Writing

- Equiano, Olaudah

- Erdrich (Ojibwe), Louise

- Faulkner, William

- Fauset, Jessie

- Federalist Papers, The

- Ferlinghetti, Lawrence

- Fiedler, Leslie

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott

- Frank, Waldo

- Franklin, Benjamin

- Freeman, Mary Wilkins

- Frontier Humor

- Fuller, Margaret

- Gaines, Ernest

- Garland, Hamlin

- Garrison, William Lloyd

- Gibson, William

- Gilman, Charlotte Perkins

- Ginsberg, Allen

- Glasgow, Ellen

- Glaspell, Susan

- González, Jovita

- Graphic Narratives in the U.S.

- Great Awakening(s)

- Griggs, Sutton

- Harper, Frances Ellen Watkins

- Harte, Bret

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel

- Hawthorne, Sophia Peabody

- H.D. (Hilda Doolittle)

- Hellman, Lillian

- Hemingway, Ernest

- Higginson, Ella Rhoads

- Higginson, Thomas Wentworth

- Hughes, Langston

- Indian Removal

- Irving, Washington

- James, Henry

- Jefferson, Thomas

- Jesuit Relations

- Jewett, Sarah Orne

- Johnson, Charles

- Johnson, James Weldon

- Kerouac, Jack

- King, Martin Luther

- Kirkland, Caroline

- Knight, Sarah Kemble

- Larsen, Nella

- Lazarus, Emma

- Le Guin, Ursula K.

- Lewis, Sinclair

- Literary Biography, American

- Literature, Italian-American

- London, Jack

- Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth

- Lost Generation

- Lowell, Amy

- Magazines, Nineteenth-Century American

- Mailer, Norman

- Malamud, Bernard

- Manifest Destiny

- Mather, Cotton

- Maxwell, William

- McCarthy, Cormac

- McCullers, Carson

- McKay, Claude

- McNickle, D'Arcy

- Melville, Herman

- Merrill, James

- Millay, Edna St. Vincent

- Miller, Arthur

- Moore, Marianne

- Morrison, Toni

- Morton, Sarah Wentworth

- Mourning Dove (Syilx Okanagan)

- Mukherjee, Bharati

- Murray, Judith Sargent

- Native American Oral Literatures

- New England “Pilgrim” and “Puritan” Cultures

- New Netherland Literature

- Newspapers, Nineteenth-Century American

- Norris, Zoe Anderson

- Northup, Solomon

- O'Brien, Tim

- Occom, Samson and the Brotherton Indians

- Olsen, Tillie

- Olson, Charles

- Ortiz, Simon

- Paine, Thomas

- Piatt, Sarah

- Pinsky, Robert

- Plath, Sylvia

- Poe, Edgar Allan

- Porter, Katherine Anne

- Realism and Naturalism

- Reed, Ishmael

- Regionalism

- Rich, Adrienne

- Rivera, Tomás

- Robinson, Kim Stanley

- Roth, Henry

- Roth, Philip

- Rowson, Susanna Haswell

- Ruiz de Burton, María Amparo

- Russ, Joanna

- Sanchez, Sonia

- Schoolcraft, Jane Johnston

- Sentimentalism and Domestic Fiction

- Sexton, Anne

- Silko, Leslie Marmon

- Sinclair, Upton

- Smith, John

- Smith, Lillian

- Spofford, Harriet Prescott

- Stein, Gertrude

- Steinbeck, John

- Stevens, Wallace

- Stoddard, Elizabeth

- Stowe, Harriet Beecher

- Tate, Allen

- Terry Prince, Lucy

- Thoreau, Henry David

- Time Travel

- Tourgée, Albion W.

- Transcendentalism

- Truth, Sojourner

- Twain, Mark

- Tyler, Royall

- Updike, John

- Vallejo, Mariano Guadalupe

- Viramontes, Helena María

- Vizenor, Gerald

- Walker, David

- Walker, Margaret

- War Literature, Vietnam

- Warren, Mercy Otis

- Warren, Robert Penn

- Wells, Ida B.

- Welty, Eudora

- Wendy Rose (Miwok/Hopi)

- Wharton, Edith

- Whitman, Sarah Helen

- Whitman, Walt

- Whitman’s Bohemian New York City

- Whittier, John Greenleaf

- Wideman, John Edgar

- Wigglesworth, Michael

- Williams, Roger

- Williams, Tennessee

- Williams, William Carlos

- Wilson, August

- Winthrop, John

- Wister, Owen

- Woolman, John

- Woolson, Constance Fenimore

- Wright, Richard

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|195.158.225.244]

- 195.158.225.244

Langston Hughes

For several decades Langston Hughes was simultaneously the foremost African American poet and the premier poet of the American Left. Without understanding that double identity and dual cultural role, there is little chance of winning a full or fair appreciation of his life and work. Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri, but grew up mainly in Lawrence, Kansas. Before enrolling at the historically black Lincoln University, he had worked at numerous menial jobs but also seen Africa, Mexico, and Paris. He would later make trips to the Soviet Union and to Spain during the Spanish Civil War. "Letter from Spain" was written in the midst of that war and handed to American poet Edwin Rolfe in Madrid for publication in the International Brigades magazine Volunteer for Liberty in November, 1937. Hughes would also write several stage plays and musicals, along with numerous newspaper columns, an autobiography, and several collections of short stories featuring his character Simple. Jazz and the blues remained a strong influence from his first books to the masterful collage poem Ask Your Mama (1962). Throughout his career, the typical Hughes poem communicated a rich social and political vision through deceptively simple language; his apparently straightforward rhetorical surfaces are intricately nuanced. He wrote some of America's most telling indictments of racism but also reached out to the poor of all ethnic backgrounds. And he was one of the few male poets of his generation who could write persuasively both about women and within a female persona.

Bibliography

- Langston Hughes Bibliography

Biographical Criticism

- Arnold Rampersad: On "Hughes's Life and Career"

General Criticism

- James Smethurst: On "Langston Hughes in the 1930s"

Other Writing by the Poet

- Langston Hughes: "The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain" (1926)

- Langston Hughes: "To Negro Writers" (1935)

Poet Details

Poet timeline, langston hughes is born. 1 february, 1902.

Langston Hughes is born to Caroline Mercer Langston and James Nathaniel Hughes.

Hughes graduates from Central High School, Cleveland, Ohio 1 June, 1920

Hughes visits his father in mexico 1 june, 1920, hughes returns to the united states and enrolls at columbia university. 1 september, 1921.

Hughes returns home from visiting his father in Mexico. Upon his return he enrolls at Columbia University.

Hughes visits his Mother. 1 January, 1925

Hughes visits his mother in Washinton D.C.. Hughes works a series of odd jobs. These include: working as a busboy, in a laundry room, and in the office of Carter G. Woodson. Hughes remains in Washington for around a year and in that time Hughes encounters numerous notable people including Vachel Lindsay, Arna Bontemps, Wallace Thurman, and Zora Neale Hurston.

Hughes attends Lincoln University. 1 January, 1926

Hughes enrolls in courses at Lincoln University mid-semester in January of 1926. Later that year Hughes writes his acclaimed essay "The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain".

Hughes graduates from Lincoln University. 1 June, 1929

Hughes graduates from Lincoln University.

Hughes goes to Russia. 1 April, 1932

Hughes heads to Russia to support production of the film Black and White, designed to help Russia appear as though it had conquered racial oppression. The film project fell apart 2 months later.

Hughes visits China. 1 July, 1933

Hughes visits China. Hughes stays for approximately three weeks, in that time he requests to visit Madame Sun Yet-sen. Instead of an interview he is invited to have dinner with her. A few weeks later Hughes returns to Japan from which he is expelled by Japanese authorities.

Hughes returns to Japan. 30 July, 1933

Hughes returns to Japan. Upon arrival he is questioned by Japanese authorities for several hours. After which he is instructed to leave Japan and not return.

Hughes founds the Harlem Suitcase Theatre. 20 February, 1937

Langston hughes dies. 22 may, 1967.

Langston Hughes dies at age 65 as a result of prostate cancer.

Hughes’s home is considered a landmark by The New York City Preservation Commission 1 January, 1982

Hughes's ashes are buried. 1 february, 1991.

Hughes's ashes are buried at The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. His ashes are buried here as a celebration of his 89th birthday and Black History month. As part of an ancestral burial rite poets Maya Angelou and Amiri Baraka danced upon the site where Hughes's ashes were buried.

Langston Hughes is born. 3 November, 2015

Hughes is born to Caroline Mercer Langston and James Nathaniel Hughes.

Pastel drawing of Langston Hughes by Winold Reiss.

Book jacket for Langston Hughes's first book of poetry "The Weary Blues". Made by Miguel Covarrubias in 1926.

Book jacket for Hughs's 1961 poetry collection "Ask Your Mama: 12 Moods for Jazz."

A Right-Wing Anti-Hughes Flier

- Connect with us:

- X (Twitter)

- Identity | Redbird Scholar | Report

Essays of Langston Hughes celebrated in new book

- Author By Rachel Hatch

- August 31, 2022

A new collection of interviews, speeches, and essays by famed author Langston Hughes is available in the book Let America Be America Again: Conversations with Langston Hughes.

Hughes is considered one of the most important writers of the Harlem Renaissance, the African American artistic movement in the 1920s that celebrated Black life and culture.

Texts in the new book range from conversational essays and early interviews in the 1920s to major speeches, such as Hughes’ keynote address at the 1966 First World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal. “His words in this volume further amplify the international reputation Hughes established over the course of five decades through more widely published and well-known poems, stories, novels, and plays,” said the editor of Let America Be America Again , Dr. Christopher De Santis , a professor of African American and American literature at Illinois State University.

Published through Oxford University Press, Let America Be America Again is titled after Hughes’ 1936 poem that critiqued the proliferation of racism, fascism, and economic oppression in the democratic nation. “A global traveler throughout his career, Hughes’ words, ‘Let America be America Again’ were always followed by a caveat: ‘America never was America to me,’” said De Santis, who added he hopes the new book “will both broaden awareness of Hughes’ powerfully incisive, anti-racist, and anti-fascist thinking as well as provide readers important historical contexts.”

Crossroads Project: Bringing diverse voices center stage

Q&A with Angela Yon: Digital exhibit spotlights humanity of circus performers

Discoveries in the data: High Performance Computing cluster powers cutting edge research

Prolific College of Business researcher keeps close eye on India-based international businesses

Redbird Media Spring 2023: Latest books from #RedbirdScholar faculty

Game changer: Upgrades to nursing simulation space to aid faculty research

Grants support cattle, farm, cotton, and concrete research

Stream sounds: Grad student listens in on aquatic life to solve underwater mystery

Dr. Martin Engelke awarded $1.6 million NIH grant for cell physiology studies

Three named 2022 “Researchers to Know”

Illinois State receives $780,000 grant as part of nationwide network to enhance inclusion, equity in STEM disciplines

Dr. Kathryn Sampeck awarded British Academy Global Professorship

A bright opportunity: ISU student studies solar physics at Harvard

Manna and Biswas receive NSF grant for cutting-edge experimental physics research

Molecular and cellular biology student conducts genomic research in Utah

Illinois State student spends summer researching at Yale

Summer grants offer Illinois State students immersive research experiences

Much of De Santis’ scholarly career has focused on the works of Hughes. He is also an editor of The Collected Works of Langston Hughes , including the volumes Fight for Freedom and Other Writings on Civil Rights and Essays on Art, Race, Politics, and World Affairs . De Santis has been celebrated for innovative teaching and research at Illinois State and served as chair of the Department of English from 2013 to 2022.

Let America Be America Again is currently in print in the United Kingdom. It is available in the United States as an e-book on Barnes & Noble , Amazon , and Google . It will be released in print in the U.S. in November 2022.

Related Articles

- Privacy Statement

- Appropriate Use Policy

- Accessibility Resources

The Model Short Story

On "salvation" by langston hughes.

Matthew Sharpe

“Salvation” is the third chapter of Langston Hughes’s memoir The Big Sea , but this two-page tour de force of prose is also a compact and complete story. Here are five things I like about it:

- The control of time. As the story opens, time breezes along in the weeks leading up to the revival meeting at twelve-year-old Langston’s church. Time then slows down paragraph by paragraph until, as Langston’s decisive moment approaches, it creeps.

- The control of space. Sometimes we see close-ups from twelve-year-old Langston’s point of view of “old women with jet-black faces and braided hair, old men with work-gnarled hands”; other times we see long shots, as if from up in the church’s rafters: “Suddenly the whole room broke into a sea of shouting. Waves of rejoicing swept the place.” And, as the church does, the author imbues with enormous significance the ten feet of space between the front row of pews and the altar, which the boy must cross to be saved.

- The doubleness of the narrator. His diction and sensibility move fluidly back and forth between the man’s and the boy’s.

- Polyphony. Not only the two Langstons’, but his Auntie Reed’s, the preacher’s, and his friend Westley’s voices are heard, as is the voice of the church via the liturgy.

- Irony. The verbal irony of the title, “Salvation,” is a kind of shorthand for the dramatic irony of the plot, wherein the more lost young Langston feels, the more his fellow congregants are convinced they are saving him.

“Salvation” by Langston Hughes

I was saved from sin when I was going on thirteen. But not really saved. It happened like this. There was a big revival at my Auntie Reed’s church. Every night for weeks there had been much preaching, singing, praying, and shouting, and some very hardened sinners had been brought to Christ, and the membership of the church had grown by leaps and bounds. Then just before the revival ended, they held a special meeting for children, “to bring the young lambs to the fold.” My aunt spoke of it for days ahead. That night I was escorted to the front row and placed on the mourners’ bench with all the other young sinners, who had not yet been brought to Jesus.

My aunt told me that when you were saved you saw a light, and something happened to you inside! And Jesus came into your life! And God was with you from then on! She said you could see and hear and feel Jesus in your soul. I believed her. I had heard a great many old people say the same thing and it seemed to me they ought to know. So I sat there calmly in the hot, crowded church, waiting for Jesus to come to me.

The preacher preached a wonderful rhythmical sermon, all moans and shouts and lonely cries and dire pictures of hell, and then he sang a song about the ninety and nine safe in the fold, but one little lamb was left out in the cold. Then he said: “Won’t you come? Won’t you come to Jesus? Young lambs, won’t you come?” And he held out his arms to all us young sinners there on the mourners’ bench. And the little girls cried. And some of them jumped up and went to Jesus right away. But most of us just sat there.

A great many old people came and knelt around us and prayed, old women with jet-black faces and braided hair, old men with work-gnarled hands. And the church sang a song about the lower lights are burning, some poor sinners to be saved. And the whole building rocked with prayer and song.

Still I kept waiting to see Jesus.

Finally all the young people had gone to the altar and were saved, but one boy and me. He was a rounder’s son named Westley. Westley and I were surrounded by sisters and deacons praying. It was very hot in the church, and getting late now. Finally Westley said to me in a whisper: “God damn! I’m tired o’ sitting here. Let’s get up and be saved.” So he got up and was saved.

Then I was left all alone on the mourners’ bench. My aunt came and knelt at my knees and cried, while prayers and song swirled all around me in the little church. The whole congregation prayed for me alone, in a mighty wail of moans and voices. And I kept waiting serenely for Jesus, waiting, waiting – but he didn’t come. I wanted to see him, but nothing happened to me. Nothing! I wanted something to happen to me, but nothing happened.

I heard the songs and the minister saying: “Why don’t you come? My dear child, why don’t you come to Jesus? Jesus is waiting for you. He wants you. Why don’t you come? Sister Reed, what is this child’s name?”

“Langston,” my aunt sobbed.

“Langston, why don’t you come? Why don’t you come and be saved? Oh, Lamb of God! Why don’t you come?”

Now it was really getting late. I began to be ashamed of myself, holding everything up so long. I began to wonder what God thought about Westley, who certainly hadn’t seen Jesus either, but who was now sitting proudly on the platform, swinging his knickerbockered legs and grinning down at me, surrounded by deacons and old women on their knees praying. God had not struck Westley dead for taking his name in vain or for lying in the temple. So I decided that maybe to save further trouble, I’d better lie, too, and say that Jesus had come, and get up and be saved.

So I got up.

Suddenly the whole room broke into a sea of shouting, as they saw me rise. Waves of rejoicing swept the place. Women leaped in the air. My aunt threw her arms around me. The minister took me by the hand and led me to the platform.

When things quieted down, in a hushed silence, punctuated by a few ecstatic “Amens,” all the new young lambs were blessed in the name of God. Then joyous singing filled the room.

That night, for the first time in my life but one for I was a big boy twelve years old – I cried. I cried, in bed alone, and couldn’t stop. I buried my head under the quilts, but my aunt heard me. She woke up and told my uncle I was crying because the Holy Ghost had come into my life, and because I had seen Jesus. But I was really crying because I couldn’t bear to tell her that I had lied, that I had deceived everybody in the church, that I hadn’t seen Jesus, and that now I didn’t believe there was a Jesus anymore, since he didn’t come to help me.

“Salvation” from The Big Sea by Langston Hughes. Copyright © 1940 by Langston Hughes. Copyright renewed 1968 by Arna Bontemps and George Houston Bass. Reprinted by permission of Hill and Wang, a division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. www.fsgbooks.com

Langston Hughes (1902-1967) was a poet, novelist, playwright, columnist, memoirist, and short story writer. The author of more than 30 books and a dozen plays, he was extremely influential during the Harlem Renaissance and in the decades beyond; he also had a profound influence on a younger generation of writers, including Paule Marshall and Alice Walker. “Salvation” is taken from his memoir, The Big Sea .

About this series

In The Model Short Story, acclaimed authors choose a short story and discuss its importance to them and how it has assisted them in their own writing practice.

Discover Our Fiction, Essays & More

Biking Home

Remnants of My Homeland

A Raised Eyebrow

Falling into the Culture of In-Between

The Story of the Skipping Stone

San and Bert

All the Buttons

Public Park Therapy

An Excerpt from Brad Kessler's North

An Excerpt from Myriam J. A. Chancy's What Storm, What Thunder

As They Imagine Us on Summer Nights

A Letter to Mama

Recalcitrance

Clairvoyance

The Thing in the Wall

The Pumpkin

Floor Meditations

Skeleton Love

“Salvation” Essay by Langston Hughes Essay

Introduction, works cited.

The Harlem Renaissance, a period spanning roughly the decades of the 1920s and 1930s, is frequently referred to as a literary movement, but the movement also encompassed a great explosion of African-American expression in many venues that celebrated the unique heritage, art forms, sights and sounds that were the African-American experience. One of the literary artists that gained the most recognition during this period was Langston Hughes. Hughes came into his professional years just as the Harlem Renaissance was becoming recognized on a more national scale and had the courage to both take inspiration from and yet disagree with his mentors such as W.E.B. DuBois by writing about the positive and negative aspects of black life. One of these experiences is included in his essay “Salvation,” in which he talks about an experience he had as a 13 year old boy in the kind of church revivals that were at the center of African American social life.

There are several clues within the essay that it was written from the reminiscent perspective of an older man rather than the more immediate perspective of the boy he was including his choice of words, his more developed understanding of human nature shown through his sarcasm and his greater understanding of his own reactions.

Hughes includes several clues throughout his essay that he is writing a memory by the words that he uses. He starts his essay by stating that “I was saved from sin when I was going on thirteen … It happened like this.” This is clearly a sign that what is about to be discussed is a memory and not something that has just happened. He talks about how he was ‘escorted’ to the front row and how the preacher preached a “wonderful rhythmic sermon,” words and phrases that do not seem completely comfortable within the mouth of a young teenager unsure of what is going on or hurriedly attempting to capture his confused feelings on paper. As the church celebrates his ‘salvation’, Hughes describes the “hushed silence, punctuated by a few ecstatic ‘amens’.” Here again is the voice of an older man with a greater vocabulary and the leisure to carefully chose the words he wants to use instead of the confused 13-year-old still stinging from his experience.

Hughes also demonstrates that he has a much higher understanding of human nature in his descriptions of the people of the church and his slight addition of sarcasm within the essay. Describing his own anticipation of the event, Hughes describes how his belief in the concept that Jesus would come to him was fostered by the descriptions his aunt and others had given to him, indicating his natural childlike inclination to believe what his elders said. His description of the minister’s sermon, though, “all moans and shouts and lonely cries and dire pictures of hell,” carries a hint of sarcasm as he points out the now obvious way in which the minister and the rest of the church manipulated the children into pretending they ‘saw’ Jesus at the revival. As he describes the way in which his aunt reacted at the church, seeing that her nephew was the only child left who was not called to Jesus, he seems to understand more why that kind of pressure worked on him and how it reflected back on her, both that he was slow to ‘see’ Jesus and that he was willing to do whatever he was supposed to do in order to save her from embarrassment. His description of the hysteric behavior of the church members, praying, singing and making a fuss over him as they did, hints at a touch of anger that they would put so much pressure on a little boy.

Finally, the essay demonstrates that Hughes has a much stronger understanding of himself and his own reactions throughout this experience. He describes how he felt ashamed at holding everything up and keeping all the people there so late. Although he seemed to have realized, even at 13, that God would not strike him down because he lied in church, this is a realization that he seems to have long ago accepted rather than just now accepted. The depth of his feeling at that time, that caused him to cry the only other time he had cried in his (semi-) adult life, would not come out on paper in such a thoughtful, coherent format as expressed in this essay. Hughes also understands the reason why he was crying so deeply, “I was really crying because I couldn’t bear to tell her that I had lied, that I had deceived everybody in the church, that I hadn’t seen Jesus, and that now I didn’t believe there was a Jesus anymore, since he didn’t come to help me.” In the way that he has written the essay, Hughes no longer seems contrite and sorrowful about lying, but perhaps a little angry that the church members made him feel this way.

Although there is nothing in the essay that suggests it couldn’t possibly have been written by a 13-year-old Langston Hughes; it is much more likely that he wrote the essay at a much older and more mature age. There are numerous hints throughout the essay, such as in his sophisticated word choice, his subtle understanding of human nature and his own understanding of his earlier reaction. If this essay had been written at the time that Hughes had this experience, the essay would have been much more emotional and less organized.

Hughes, Langston. “Salvation.”

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, December 14). "Salvation" Essay by Langston Hughes. https://ivypanda.com/essays/salvation-essay-by-langston-hughes/

""Salvation" Essay by Langston Hughes." IvyPanda , 14 Dec. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/salvation-essay-by-langston-hughes/.

IvyPanda . (2021) '"Salvation" Essay by Langston Hughes'. 14 December.

IvyPanda . 2021. ""Salvation" Essay by Langston Hughes." December 14, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/salvation-essay-by-langston-hughes/.

1. IvyPanda . ""Salvation" Essay by Langston Hughes." December 14, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/salvation-essay-by-langston-hughes/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . ""Salvation" Essay by Langston Hughes." December 14, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/salvation-essay-by-langston-hughes/.

- Langston Hughes and the Harlem Renaissance

- "Salvation" by Langston Hughes Literature Analysis

- The Expression of Sarcasm in The Odyssey

- Irony and Sarcasm: Differences and Similarities

- Langston Hughes, His Life and Poems

- Langston Hughes: "Harlem" and "Mother to Son"

- The Life of Langston Hughes

- Impression of Langston Hughes' Work

- Langston Hughes and Black Elite

- The Inner Meaning of the Poem “Harlem” by Langston Hughes

- “Celia, a Slave” by Melton McLaurin

- A Short History of Reconstruction' by E. Foner and 'A Nation Under Our Feet' by S. Hahn

- "Rebecca’s Revival" by F. Sensbach

- Ironic Elements in Metamorphoses by Ovid

- Gilgamesh King of Uruk Review: Unique Characters of Courage and Bravery

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Ransom Center Magazine

A lost work by Langston Hughes

February 1, 2021 - Steven Hoelscher

In 1933, the Harlem Renaissance star wrote a powerful essay about race, unpublished in English until 2019.

It’s not every day that you come across an extraordinary unknown work by one of the nation’s greatest writers. But buried in an unrelated archive, I discovered a searing essay condemning racism in America by Langston Hughes—the moving account, published in its original form below , of an escaped prisoner he met while traveling with Zora Neale Hurston.

In the summer of 1927, Hughes lit out for the American South to learn more about the region that loomed large in his literary imagination. After giving a poetry reading at Fisk University in Nashville, Hughes journeyed by train through Louisiana and Mississippi before disembarking in Mobile, Alabama. There, to his surprise, he ran into Hurston, his friend and fellow author. Described by Yuval Taylor in his new book Zora and Langston as “one of the more fortuitous meetings in American literary history,” the encounter brought together two leading lights of the Harlem Renaissance. On the spot, the pair decided to drive back to New York City together in Hurston’s small Nash coupe.

The terrain along the back roads of the rural South was new to Hughes, who grew up in the Midwest; by contrast, Hurston’s Southern roots and training as a folklorist made her a knowledgeable guide. In his journal Hughes described the black people they met in their travels: educators, sharecropping families, blues singers and conjurers. Hughes also mentioned the chain gang prisoners forced to build the roads they traveled on.

Three years later, Hughes gave the poor, young and mostly black men of the chain gangs a voice in his satirical poem “Road Workers”—but we now know that the images of these men in gray-and-black-striped uniforms continued to linger in the mind of the writer. In this newly discovered manuscript, Hughes revisited the route he traveled with Hurston, telling the story of their encounter with one young man picked up for fighting and sentenced to hard labor on the chain gang.

I first stumbled upon this Hughes essay in the papers of John L. Spivak, a white investigative journalist in the 1920s and 1930s, at the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin. Not even Hughes’s authoritative biographer Arnold Rampersad could identify the manuscript. Eventually, I learned that Hughes had written it as an introduction to a novel Spivak published in 1932, Georgia Nigger . The book was a blistering exposé of the atrocious conditions that African Americans suffered on chain gangs, and Spivak gave it a deliberately provocative title to reflect the brutality he saw. Scholars today consider the forced labor system a form of slavery by another name. On the final page of the manuscript (not reproduced here), Hughes wrote that by “blazing the way to truth,” Spivak had written a volume “of great importance to the Negro peoples.”

Hughes titled these three typewritten pages “Foreword From Life.” And in them he also laid bare his fears of driving through Jim Crow America. “We knew that it was dangerous for Northern Negroes to appear too interested in the affairs of the rural South,” he wrote. (Hurston packed a chrome-plated pistol for protection during their road trip.)

But a question remained: Why wasn’t Hughes’s essay included in any copy of Spivak’s book I had ever seen? Buried in Spivak’s papers, I found the answer. Hughes’s essay was written a year after the book was published, commissioned to serve as the foreword of the 1933 Soviet edition and published only in Russian.

In early 1933, Hughes was living in Moscow, where he was heralded as a “revolutionary writer.” He had originally traveled there a year earlier along with 21 other influential African Americans to participate in a film about American racism. The film had been a bust (no one could agree on the script), but escaping white supremacy in the United States—at least temporarily—was immensely appealing. The Soviet Union, at that time, promoted an ideal of racial equality that Hughes longed for. He also found that he could earn a living entirely from his writing.

For this Russian audience, Hughes reflected on a topic as relevant today as it was in 1933: the injustice of black incarceration. And he captured the story of a man that—like the stories of so many other young black men—would otherwise be lost. We may even know his name: Hughes’s journal mentions one Ed Pinkney, a young escapee whom Hughes and Hurston met near Savannah. We don’t know what happened to him after their interaction. But by telling his story, Hughes forces us to wonder.

Read the essay by Langston Hughes:

Foreword From Life

By Langston Hughes Reprinted with permission of Harold Ober Associates. Copyright 1933 by The Langston Hughes Estate.

I had once a short but memorable experience with a fugitive from a chain gang in this very same Georgia of which [John L.] Spivak writes. I had been lecturing on my poetry at some of the Negro universities of the South and, with a friend, I was driving North again in a small automobile. All day since sunrise we had been bumping over the hard red clay roads characteristic of the backward sections of the South. We had passed two chain gangs that day, ¹ one in the morning grading a country road, and the other about noon, a group of Negroes in gray and black stripped [sic] suits, bending and rising under the hot sun, digging a drainage ditch at the side of the highway. ² We wanted to stop and talk to the men, but we were afraid. The white guards on horseback glared at us as we slowed down our machine, so we went on. On our automobile there was a New York license, and we knew it was dangerous for Northern Negroes to appear too interested in the affairs of the rural South. Even peaceable Negro salesmen had been beaten and mobbed by whites who objected to seeing a neatly dressed colored person speaking decent English and driving his own automobile. ³ So we did not stop to talk to the chain gangs as we went by.

But that night a strange thing happened. After sundown, in the evening dusk, as we were nearing the city of Savannah, we noticed a dark figure waving at us frantically from the swamps at the side of the road. We saw that it was a black boy.

“Can I go with you to town?” the boy stuttered. His words were hurried, as though he were frightened, and his eyes glanced nervously up and down the road.

“Get in,” I said. He sat between us on the single seat.

“Do you live in Savannah?” we asked.

“No, sir,” the boy said. “I live in Atlanta.” We noticed that he put his head down nervously when other automobiles passed ours, and seemed afraid.

“And where have you been?” we asked apprehensively.

“On the chain gang,” he said simply.

We were startled. “They let you go today?”

“No, sir. I ran away. 4 That’s why I was afraid to walk in the town. I saw you-all was colored and I waved to you. I thought maybe you would help me.”

Gradually, before the lights of Savannah came in sight, in answer to our many questions, he told us his story. Picked up for fighting, prison, the chain gang. But not a bad chain gang, he said. They didn’t beat you much in this one. 5 Only once the guard had knocked two teeth out. That was all. But he couldn’t stand it any longer. He wanted to see his wife in Atlanta. He had been married only two weeks when they sent him away, and she needed him. He needed her. So he had made it to the swamp. A colored preacher gave him clothes. Now, for two days, he hadn’t eaten, only running. He had to get to Atlanta.

“But aren’t you afraid,” [w]e asked, “they might arrest you in Atlanta, and send you back to the same gang for running away? Atlanta is still in the state of Georgia. Come up North with us,” we pleaded, “to New York where there are no chain gangs, and Negroes are not treated so badly. Then you’ll be safe.”

He thought a while. When we assured him that he could travel with us, that we would hide him in the back of the car where the baggage was, and that he could work in the North and send for his wife, he agreed slowly to come.

“But ain’t it cold up there?” he said.

“Yes,” we answered.

In Savannah, we found a place for him to sleep and gave him half a dollar for food. “We will come for you at dawn,” we said. But when, in the morning we passed the house where he had stayed, we were told that he had already gone before daybreak. We did not see him again. Perhaps the desire to go home had been greater than the wish to go North to freedom. Or perhaps he had been afraid to travel with us by daylight. Or suspicious of our offer. Or maybe […] 6

© 2019 Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with permission from Smithsonian Enterprises. All rights reserved. Reproduction in any medium © 2019 Smithsonian Institution strictly prohibited without permission from Smithsonian Institution.

[1] This sight was common. By 1930 in Georgia alone, more than 8,000 prisoners, mostly black men, toiled on chain gangs in 116 counties. The punishment was used in Georgia from the 1860s through the 1940s.

[2] Adopting the voice of a chain gang laborer in the poem “Road Workers,” published in the New York Herald Tribune in 1930, Hughes wrote, “Sure, / A road helps all of us! / White folks ride — /And I get to see ’em ride.”

[3] The NAACP collected reports of violence against blacks in this era, including a similar incident in Mississippi in 1925. Dr. Charles Smith and Myrtle Wilson were dragged from a car, beaten and shot. The only cause recorded: “jealousy among local whites of the doctor’s new car and new home.”

[4] In his journal, Hughes wrote about meeting an escaped convict named Ed Pinkney near Savannah. Hughes noted that Pinkney was 15 years old when he was sentenced to the chain gang for striking his wife.

[5] Guard-on-convict violence was pervasive on Jim Crow-era chain gangs. Inmates begged for transfers to less violent camps but requests were rarely granted. “I remembered the many, many such letters of abuse and torture from ‘those who owed Georgia a debt,’” Spivak wrote.

[6] In the English manuscript, the end of Hughes’s story about the convict trails off with an incomplete thought—“Or maybe”—but the Russian translation continues: “Or maybe he got scared of the cold? But most importantly, his wife was nearby!”

Before Footer

Ransom Center Magazine is an online and print publication sharing stories and news about the Harry Ransom Center , its collections, and the creative community surrounding it.

Sign up for eNews

Our monthly newsletter highlights news, exhibitions, and programs.

Connect With Us

Copyright © 2024 Harry Ransom Center

Web Accessibility · Web Privacy

- Houston Community College

- Eagle Online

- Emily Klotz

- ENDED - Dual Credit English Composition I (online) - Fall 2020 (ENGL 1301)

- Course Readings

"Salvation" - Langston Hughes

To print or download this file, click the link below:

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Race/Related

Harlem Was No Longer the Same After This Dinner Party

Harlem was synonymous with the arts. But what I didn’t know was how that had come to be.

By Veronica Chambers

This article is also a weekly newsletter. Sign up for Race/Related here .

As a kid growing up in Brooklyn, Harlem always seemed like a magical place. I learned about the Studio Museum in Harlem and artists like Alma Thomas and Romare Bearden. Langston Hughes’s poems were featured on posters in my local library, and everybody knew Duke Ellington because of his signature tune, “Take the A Train,” written by Billy Strayhorn. There were the Apollo Theater, where Ella Fitzgerald first sang, and dance troupes like the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and Dance Theater of Harlem. Harlem was synonymous with the arts. But what I didn’t know was how that had come to be.

My senior thesis in college was on the dinner party that launched the Harlem Renaissance. It was amazing to me that a group of creative giants had prioritized art to serve as a case study in marrying talent to opportunity. The people I knew often said that art could make a difference, but the Harlem Renaissance showed me it was truly possible. In the early 1920s, Black Americans were excluded from many of the fields in which other Americans were building bases of power and generational wealth: from the unions to Wall Street and Congress. But as the historian David Levering Lewis noted, “no exclusionary rules had been laid down regarding a place in the arts. Here was a small crack in the wall of racism, a fissure that was worth trying to widen.”

So on March 21, 1924, two Black academics, Alain Locke and Charles S. Johnson, invited more than 100 guests to the Civic Club in Manhattan with a grand plan to give young Black artists a shot at the kinds of opportunities they’d rarely had before: book deals with major publishing houses, their artwork on display in museums, their songs on radio and Broadway rotation. The party was, as we wrote about it recently in the Times , a major success. In the decade afterward, more than 40 major works by Black Americans were published. Levering Lewis wrote in When Harlem was in Vogue that no more than five Black American writers published significant books between 1908 and 1923.

What we know now, and what we’ll keep exploring in this series about the 100th anniversary of the Harlem Renaissance , is how that kind of creativity and hope can take on an astonishing velocity. From the inimitable voice of the writer Zora Neale Hurston and the painted murals of Aaron Douglas to the song stylings of Louis Armstrong, Harlem was forever changed after the Civic Club dinner. Wallace Thurman, a poet who lived in Harlem during the Renaissance, noted that the neighborhood had become “almost a Negro Greenwich Village. Every other person you meet is writing a novel, a poem or a drama.”

It’s not too hard to draw a line between the work that was begun then to the work that exists now: the poetry of Mahogany L. Browne and Kwame Alexander, the Black superheroes imagined by Eve L. Ewing and Malcolm Spellman, or the novels by Colson Whitehead, Edwidge Danticat and James McBride. The Harlem Renaissance reshaped the landscape of American culture, and for Black artists around the globe the aperture of what was possible widened.

Invite your friends. Invite someone to subscribe to the Race/Related newsletter. Or email your thoughts and suggestions to [email protected] .

Veronica Chambers is the editor of Narrative Projects, a team dedicated to starting up multi-layered series and packages at The Times. More about Veronica Chambers

A New Light on the Harlem Renaissance

A century after it burst on the scene in new york city, the first african american modernist movement continues to have an impact in the american cultural imagination..

The Dinner Party: When Charles Johnson and Alain Locke thought that a celebration for Jessie Fauset’s book “There Is Confusion” could serve a larger purpose, the Harlem Renaissance was born .

A Period of Survival: During the Harlem Renaissance, some Black people hosted rent parties , celebrations with an undercurrent of desperation in the face of racism and discrimination.

An Ambitious Show: A new MoMA exhibition, “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism,” aims to shift our view of the time when Harlem flourished as a creative capital. It gets it right, our critic writes .

An Enduring Legacy: We asked six artists to share their thoughts on the contributions that the Harlem Renaissance artists made to history

Crafting a New Life: At the dawn of the Harlem Renaissance, Augusta Savage fought racism to earn acclaim as a sculptor. The path she forged is also her legacy .

- Langston Hughes Essay

Langston Hughes was an African American writer and poet who is most well-known for his work during the Harlem Renaissance. He wrote about topics that were important to the black community, such as the blues and jazz. He also wrote poems that spoke to the experience of being black in America. His work helped to redefine what it meant to be black in America and paved the way for future generations of black writers.

You can sense Langston Hughes’ energy when you’re reading one of his poems. The way he uses his words to express what he’s writing about is incredible. Many people consider Langston Hughes to be one of the finest poets in history, and I am among them.

His work during the Harlem Renaissance was some of the most important and significant pieces during that time. A lot of people don’t know about Langston Hughes and what he did for the world, but his work is still appreciated by many people today.

Langston Hughes was an African-American writer who was born in 1902. He is known for his blues poetry and his work during the Harlem Renaissance. He wrote about the struggles that black people faced in America during the early 1900s. Many of his poems were based on his own personal experiences as a black man living in America.

One of my favorite Langston Hughes poems is “The Weary Blues”. This poem is about a musician who is playing the blues. The poem is written in first person, so you can feel the musician’s pain and weariness as he’s playing his music.

Langston Hughes was an extremely talented writer and poet. His work has inspired many people, including me. If you haven’t read any of his work, I highly recommend that you do. You won’t be disappointed.