- Otis College of Art and Design

- Otis College LibGuides

- Millard Sheets Library

Introduction to Visual Culture

- I-Search Paper

- List of Pairs

- Books and Additional Resources

- Wikipedia This link opens in a new window

- Quality Sources This link opens in a new window

- Types of Information This link opens in a new window

- Sample Annotations This link opens in a new window

- Art History Tutoring This link opens in a new window

I-Search Paper versus Research Report

An I-Search paper is a mindful introduction to doing research.

Instead of focusing on finding sources that support a thesis, an I-Search paper is all about the process. Through documentation and reflection, students can compare how their understanding of the pair of objects evolves as their knowledge about it deepens. They can examine their search strategies, to become better researchers in the future.

For experienced researchers, the I-Search paper is a way to reflect and improve upon your current research skills.

How to Write the I-Search Paper

What is an i-search paper.

An I-Search Paper helps you learn the nature of searching and discovery on a chosen topic. Your goal is to pay attention, track this exploration, and LEARN HOW YOU LEARN so that you can repeat the process in other courses.

The I-Search Paper should be the story of your search process , including chronological reflections on the phases of research in a narrative form. The I is for YOU. It's the story of YOUR search and what YOU learned.

Image: Franzi

Step 1. Document Your Research Process

Keep track of the actual search terms and specific databases you used and how you modified your strategy as you went along. You will include those details in your paper. Analyze the results. How many hits did you get? Say how and why you modified your search strategy to get more or less. What did you learn about each database that you tried? What kind of information did you find. Why were the names of the journals or magazines articles were in.

In all your research, include actual facts and theories that you discover about your topic as well as idiosyncratic information such as what surprised you. You could say what you already knew about the topic before beginning the research and how what you knew about that topic may have changed during the research process.

If you have trouble finding relevant materials in the Library, ask a librarian . They have Master's Degrees in research, are more discerning than search engines. Plus, they are happy to assist!

Image: InkFactory

2. Look Through Art History Survey Sites

Consult reputable online art history sites, such as the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History and smARThistory .

If you are able to physically visit the Library, there are several general art history textbooks ( N 5300 ) available in the Reference section, including Art History by Marilyn Stokstad. They are concise sources for specific art historical contexts for your chosen objects. Some are as e-books.

Many (but not all) of the Wall items are discussed in all of these general art history resources.

Step 3. Search Wikipedia

What you want to learn is the facts about the object--context, movement, date, etc. To find more about how to appropriately use Wikipedia for college-level research, consult the Research Guide for Wikipedia .

Wikipedia is an encyclopedia which is excellent for background information . Pay special attention to the footnotes and references at the bottom of the page. they may guide you to excellent academic sources.

Step 4. Search the Library Catalog

Next, search OwlCat , the library catalog, for books, ebooks, and articles.

Many of the objects you are researching have articles and sometimes even entire books written about them. If not, you should find some articles. If you cannot find enough items, broaden your search to find a book about the artist, designer, or culture.

Once you find a suitable item, use its call number and browse the shelves for similar items.

Step 5. Search the Databases

Check out the Databases listed on the Library website. OwlCat's search results may be overwhelming, so it may be easier to search each research database individually.

Art Source is arguably the best for art courses and is tightly integrated into OwlCat. ProQuest Research Library also covers many art and desing publications; however, its results may not show up as much in OwlCat.

Explore our research databases!

Step 6. Create a Bibliography

You will then create a bibliography of at least 2 sources--books, museum websites, or journal articles. Wikipedia won't really count as one of your sources since it's really just about finding background information or referrals to other sources.

If you include websites in your bibliography, make sure they are educationally oriented. Find out who wrote them and what their credentials are. For instance, museum websites are often written by curators/art historians whose purpose is the educate. Additionally, Smarthistory , now part of Khan Academy, discusses many iconic works and these are written by PhD. art historians. If you find something on this site, it would be a very good source. Make sure your web sources are Quality Web Sources.

Image: Reasonist Products

Step 7. Write Evaluative Annotations

You must annotate and evaluate the sources in the bibliography or works cited list. Remember, the annotations must include the credentials of the author and the type of information (scholarly, popular, etc.), and the intended audience of the publication. See:

- Sample Annotations

- Annotation Builder

- Criteria for Evaluating Information

- Types of Information

Image: FuzzBones

Relevant Databases

Video: Searching Is Strategic

Locating information requires a combination of inquiry, discovery, and serendipity. There is no one size fits all source to find the needed information. Information discovery is nonlinear and iterative, requiring the use of abroad range of information sources and flexibility to pursuit alternate avenues as new understanding is developed. Depending on the information need and context, the learner may need to consult a variety of resources ranging from databases and books to observations and interviews.

Minimum Requirements

Foundation level competency, c - level information literacy.

Source information is RESTATED to support topic and includes TWO annotations that may be from books, database articles, or academic/museum/ professional websites.

Sources must appear as in‐text citations and on a works cited page

Each annotation must include 3 of the following criteria:

- Author’s credentials related to topic

- Description of type of source/audience

- Discussion of purpose/point of view

- Discussion of currency of the source

- Explain why the source is relevant to the assignment.

Complete Foundation Rubric

- LAS: Foundation level Core Compentency Rubric 3-Outcome Rubric, 2020 version

Do You Need Citation Help?

In addition to this guide, the Library offers a variety of information literacy instruction.

- Meet with a Librarian one-on-one for help with research, citations, and annotations

- The Student Learning Center (SLC) also provides drop-in tutoring. Be sure to check their current hours here.

- Faculty may request an in-class workshop for Annotations and/or Citations by filling out this form .

You may also visit the Library for citation help, or use the Ask a Librarian form on the Library website.

- Evaluating Sources

- Copyright and Fair Use

- Information Literacy

- << Previous: GETTING STARTED

- Next: List of Pairs >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2023 5:23 PM

- URL: https://otis.libguides.com/visual-culture

Otis College of Art and Design | 9045 Lincoln Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90045 | MyOtis

Millard Sheets Library | MyOtis | 310-665-6930 | Ask a Librarian

Promoting Student-Directed Inquiry with the I-Search Paper

About this Strategy Guide

The sense of curiosity behind research writing gets lost in some school-based assignments. This Strategy Guide provides the foundation for cultivating interest and authority through I-Search writing, including publishing online.

Research Basis

Strategy in practice, related resources.

The cognitive demands of research writing are numerous and daunting. Selecting, reading, and taking notes from sources; organizing and writing up findings; paying attention to citation and formatting rules. Students can easily lose sight of the purpose of research as it is conducted in “the real world”—finding the answer to an important question.

The I-Search (Macrorie, 1998) empowers students by making their self-selected questions about themselves, their lives, and their world the focus of the research and writing process. The strong focus on metacognition—paying attention to and writing about the research process methods and extensive reflection on the importance of the topic and findings—makes for meaningful and purposeful writing.

Online publication resources such as blogging software make for easy production of multimodal, digital writing that can be shared with any number of audiences.

Assaf, L., Ash, G., Saunders, J. and Johnson, J. (2011). " Renewing Two Seminal Literacy Practices: I-Charts and I-Search Papers ." English Journal , 18(4), 31-42.

Lyman, H. (2006). “ I-Search in the Age of Information .” English Journal , 95(4), 62-67.

Macrorie, K. (1998). The I-Search Paper: Revised Edition of Searching Writing . Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann-Boynton/Cook.

- Before introducing the I-Search paper, set clear goals and boundaries for the assignment. In some contexts, a completely open assignment can be successful. In others, a more limited focus such as research on potential careers (e.g., Lyman, 2006) may be appropriate.

- Introduce the concept of the I-Search by sharing with students that they will be learning about something that is personally interesting and significant for them—something they have the desire to understand more about. Have students generate a list of potential topics.

- Review student topic lists and offer supportive feedback—either through written comments or in individual conferences—on the topics that have the most potential for success given the scope of the assignment and the research resources to which students will have access.

- After offering feedback, have students choose the topic that seems to have the most potential and allow them to brainstorm as many questions as they can think of. When students have had plenty of time to ponder the topic, ask them to choose a tentative central question—the main focus for their inquiry—and four possible sub-questions—questions that will help them narrow their research in support of their main question. Use the I-Search Chart to help students begin to see the relationships among their inquiry questions.

- Begin the reflective component of the I-Search right away and use the I-Search Chart to help students write about why they chose the topic they did, what they already know about the topic, and what they hope to learn from their research. Students will be please to hear at this point that they have already completed a significant section of their first draft.

- Engage reader’s attention and interest; explain why learning more about this topic was personally important for you.

- Explain what you already knew about the topic before you even started researching.

- Let readers know what you wanted to learn and why. State your main question and the subquestions that support it.

- Retrace your research steps by describing the search terms and sources you used. Discuss things that went well and things that were challenging.

- Share with readers the “big picture” of your most significant findings.

- Describe your results and give support.

- Use findings statements to orient the reader and develop your ideas with direct quotations, paraphrases, and summaries of information from your sources.

- Properly cite all information from sources.

- Discuss what you learned from your research experience. How might your experience and what you learned affect your choices or opportunities in the future.

- At this point, the research process might be similar to that of a typical research project except students should have time during every class period to write about their process, questions they’re facing, challenges they’ve overcome, and changes they’ve made to their research process. Students will not necessarily be able to look ahead to the value of these reflections, so take the time early in the process to model what reflection might look like and offer feedback on their early responses. You may wish to use the I-Search Process Reflection Chart to help students think through their reflections at various stages of the process.

- Support students as they engage in the research and writing process, offering guidance on potential local contacts for interviews and other sources that can heighten their engagement in the authenticity of the research process.

- To encourage effective organization and synthesis of information from multiple sources, you may wish to have students assign a letter to each of their questions (A through E, for example) and a number to each of their sources (1 through 6, for example). As they find content that relates to one of their questions, they can write the corresponding letter in the margin. During drafting, students can use the source numbers as basic citation before incorporating more sophisticated, conventional citation.

How to Start a Blog

Blog About Courage Using Photos

Creating Character Blogs

Online Safety

Teaching with Blogs

- Content is placed on appropriate, well-labeled pages. The pages are linked to one another sensibly (all internal links).

- Images/video add to the reader’s understanding of the content, are appropriately sized and imbedded, and are properly cited.

- Text that implies a link should be hyperlinked. Internal links (to other pages of the blog) stay in the same browser window; External links (to pages off the blog) open in a new browser window.

- Lesson Plans

- Student Interactives

This tool allows students to create an online K-W-L chart. Saving capability makes it easy for them to start the chart before reading and then return to it to reflect on what they learned.

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

ENGL 1A - I-Search

- Background info

- Detailed Information

- Evaluate your sources

- Cite your sources

The I-Search paper is designed to teach the writer and the reader something valuable about a chosen topic and about the nature of searching and discovery. As opposed to the standard research paper where the writer usually assumes a detached and objective stance, the I-Search paper allows you to take an active role in your search, to experience some of the hunt for facts and truths first-hand, and to provide a step-by-step record of the discovery.

I mage by geralt, free for commercial use.

Your assignment

The first rule of the I-Search paper is to select a topic that genuinely interests you and that you need to know more about. In this case, you will be researching some aspect of Identity (Race, Class, Gender) that you are interested in or most concerned about exploring.

The I-Search paper will be written in four integrated sections:

Part I: Introduction (1-2 Pages)

Part II: What I know, Assume, or Imagine (1-2 Pages)

Part III: The Search -Two Parts (2-3 Pages)

Part IV: What I Discovered- Two Parts (4-5 pages)

Part V: References Page (1-2 pages)

I. Introduction:

The introduction of your essay should give your reader some indication of why you have chosen to write about this particular topic. Keep in mind that your essay needs to have some point. What message do you want to communicate to your reader? The message needs to be something more than "I believe…I think…I feel…." The purpose of this essay will be to inform your reader of your (1) original assumptions, (2) the information you found on your search, and (3) your discoveries.

II. What I Want to Know, What I Assume or Imagine:

Before conducting any formal research, write a section in which you explain to the reader what you think you know, what you assume, or what you imagine about your topic. There are no wrong answers here. You are basically establishing your hypothesis. For this research project, it is most effective for your hypothesis or thesis to be presented as a series of three or four questions you plan to explore answers to in the following sections.

III. The Search:

Test your knowledge, assumptions, or conjectures by researching your paper topic thoroughly. Conducting a phone or face to face interview with someone who is a KEY PLAYER: one who may be able to change or improve the problem you are addressing. If your Identity Topic involves researching is a cultural concern, perhaps you can interview a family or community member who is working towards positive change. A second requirement will be to visit Merritt’s Online Library and investigate the abundant books and Internet resources available. Other first-hand activities that may provide valuable information include writing letters, and/ or making telephone calls. Also, consult useful second-hand sources such as books, magazines, newspapers, and documentaries. Be sure to record all the information you gather.

Write up your search in a narrative form, relating the steps of the discovery process (this means that you are going to tell the story of what you did to research this topic and what you learned in the process). Do not feel obligated to tell everything (you don't have to tell us the boring stuff but highlight the happenings and facts you uncovered that were crucial to your hunt and contributed to your understanding of the information.

Your Hunt for Information: This is the story of your hunt for information. For this section, you will rely on your Journal entries. Summarize your journey from Day One of your I-Search to the finish line. Make sure to summarize how you began your research. What process did you use to conduct your research? What types of searches did you try and how did they turn out? Include your opinion on sources and the information you discovered. Show the steps you took in your thinking/brainstorming. What challenges did you experience along the way? How did you handle these challenges?

IV: What I Discovered: This section will be divided into two parts.

1) This section must be written in an objective tone which means that you should avoid using personal statements such as “I think”, “I believe”, or “I feel.” Save your opinions for your reflection. Where were each of the sources found? What did each source reveal? Did the sources effectively answer any of your questions? How? Describe each source as it relates to your original research questions (listed at the end of Part II: What I Want to Know).

2) Your Reflection: What did you learn about yourself as a researcher? Did anything about this research process surprise you? Include your opinion on sources and the information you discovered. For example, did you realize you had a bigger interest in this social issue than you originally anticipated? Reflect upon the entire search experience, not only what you got out of it, not only what you have learned, but how this search has changed your life. What do you now know about searching for information that you didn’t know before? To answer this question, you will describe those findings that meant the most to you. What are the implications of your findings? How might your newly found knowledge affect your future?

After concluding your search, compare what you thought you knew, assumed, or imagined with what you discovered, assess your overall learning experience, and offer some personal commentary about the value of your discoveries and/or draw some conclusions. Some questions that you might consider at this stage:

How accurate were your original assumptions?

What new information did you acquire?

What did you learn that surprised you?

Overall, what value did you derive from the process of searching and discovery?

Don’t just do a question/answer conclusion. Go back to the main point you want to make with this essay. What final message do you want to leave with your readers?

V. REFERENCES (APA Format):

You will be required to attach a formal bibliography, following the APA format, listing the sources you consulted to write your I-Search paper. You will need to use a minimum of six different sources. One of your sources has been chosen for you which is “The Banking Concept of Education” by Paulo Freire. Your research requires you to find five more sources: 1 – interview or survey (for extra credit), 1-book or e-book, 1-magazine, journal, or newspaper article, and 3- Internet sources. (This means that you will have at least 6 sources in your bibliography, and I would expect to see these sources cited in the body of your paper.) There are also Internet resources that can assist you with APA Documentation and other aspects of writing a research paper.

Keeping your audience firmly in mind will be an important key to success with this assignment. You don’t want to write this up as if it is simply a long journal entry. Think of your audience as freshmen in college or university transfer students who might also be interested in the information you have collected. Remember, writing is a form of communication, and you need to be clear in your own mind who you are trying to communicate with and what you want to communicate to those people. Your I-Search will need to be a MINIMUM of 8 FULL pages. Note: The 8 pages do NOT include Title Page, Cover Letter, Abstract, References Page, or Appendices.

- Next: Strategy >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2023 4:33 PM

- URL: https://merritt.libguides.com/isearch

The I-Search: Guiding Students Toward Relevant Research

Adapting a four-step process, a motivating theme, active learning, intriguing questions, a panoply of resources, assessing stage by stage, risks and rewards.

BOOM! You're sitting in the movie theater and all of a sudden a car blows up. Or you're quietly munching your popcorn while your favorite bad guy gets shot and almost simultaneously starts to bleed. Did you ever wonder how these effects are created? I certainly have. Sometimes I get so involved in figuring out how a special effect was accomplished that I lose interest in the movie. That is why I chose special effects for my I-Search topic.

Finally, each student poses an I-Search question to guide his or her inquiry. For example: Submarines helped find the remains of many ships, and also expanded our knowledge of the giant body of water that we call the ocean. I have wondered about the ocean ever since I was young. In this report I will show you what I have learned. My search question is: How do submarines expand our knowledge of the ocean?

- plan their units to engage students;

- coach students to take ownership of the inquiry process;

- incorporate a variety of materials and resources , including technology; and

- assess student work on an ongoing basis.

- What impact does technology have on our lives?

- How do job descriptions change as technology changes?

- How do the rapid changes in technology affect individuals and society?

- Why must people consider ethical issues when developing technology?

Because of their careful planning, teachers will be better able to help students connect seemingly isolated ideas and larger themes. The theme and concepts form a sort of umbrella, under which students will identify their own personally meaningful, researchable I-Search questions. In the technology unit, for example, one student framed her question this way: The reason why I chose animal treatment is because I was curious as to why they give certain things to my animals when they get sick. My question is: How has technology affected veterinary care? Now I know about some of the medicines they give our animals. I feel much better when the vet prescribes medicines that will make Lilly Mary Margaret better.

- to help students discover what they already know about the theme;

- to build background knowledge and deepen students' understanding of the theme and overarching questions;

- to model for students a variety of ways to gather information;

- to have students learn by doing; and

- to encourage students to take responsibility for their own inquiries.

The goal is for students to generate I-Search questions that they feel passionate about. Students recognize how important this is. When we asked them what advice they would give novices embarking on an I-Search process, one boy replied, You better find a question you really care about because you will be working with that question for six weeks.

- read books, magazines, newspapers, or reference texts;

- watch videos, filmstrips, or television shows;

- use CD-ROM reference tools;

- interview people or conduct surveys;

- conduct an experiment or engage in a simulation; or

- go on a field trip.

Modeling the interviewing process has been especially important. As one student reported, For my interview I called five hospitals to find an oncologist and finally I got one at Sloan Kettering.

During Phase 2, students design their search plan by working closely with the library media specialists to learn how to use the school's resources. The students' I-Search papers convey how they actively apply their research skills: I started my I-Search process by writing a business letter to a company....At first I used the computers in the library.... I looked under diabetes and there was too much information so I looked under diabetes and technology and I found a lot of good information. After the computers I went to the SIRS.... Then I finally went to microfiche and that's where I found all my information. So far that's my best source.When I first set out to research I wasn't sure where to start. I decided to use the UMI system on the school library's computer to find citations for magazines that had articles on special effects. I had never used this system before, but I soon found out it was quite simple to use. I got a list of seven or so citations in the time period I had on the computer.Walking back to my seat to look at my list I got distracted by a book I saw on the shelf. It proved to have excellent information on everything I needed and I would later find out it would be my best source of information.

The I-Search: Guiding Students Toward Relevant Research-table

Teachers also encourage students to assess their own work, a process that often reveals insights that exceed a teacher's expectations. For example, one student wrote the following in the section of the report on “What This Means to Me”: This work will be a great influence on how I act and think toward people because with this project I was able to work with other people who had a similar topic to the one I had. I had to be nice and really communicate with that person or else we wouldn't get along. I am now used to being this way with other people and not just with that person.

It is a testimonial to the teachers' coaching that students appreciate being able to pick their own topics and generally exercise independence. Said one student with learning disabilities: In this project (I) learned a lot about myself because I did this project all by myself but sometimes I needed help. I feel that I did very good. Another 7th grader told how she developed as a researcher: I learned to use the computer to gather information, which I had never attempted before because I was scared to. I no longer shy away from large books, because I learned to take things slowly, and one paragraph at a time. I also learned to not get frustrated or become overwhelmed. I also realized that if you try your best, it will be satisfactory, and you don't always have to be the absolute best.... I was surprised that I took the risk of changing my topic, but even so I am extremely glad that I did because this is what I really wanted. Other students' comments: I've learned that in every job, big or small, there are many difficulties and at the same time, moments of triumph.I learned about a subject that I knew almost nothing about and that gave me a great feeling of accomplishment.I enjoyed researching information about my topic. The most fun part was when I did my interview.I appreciate myself as a researcher and a writer because I am able to make my own decisions. I also appreciate myself because I don't have to take that many orders from teachers and other people and I am able to take risks.

Macrorie, K. (1988). The I-Search Paper . Portsmouth, N.H.: Boynton/Cook Publishers.

Zorfass, J. (1991). Make It Happen ! Newton, Mass.: Education Development Center, Inc.

Judith Zorfass has been a contributor to Educational Leadership.

Harriet Copel has been a contributor to Educational Leadership.

ASCD is a community dedicated to educators' professional growth and well-being.

Let us help you put your vision into action., from our issue.

To process a transaction with a Purchase Order please send to [email protected]

- Writing, Research & Publishing Guides

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: $40.90 $40.90 FREE delivery: Tuesday, April 9 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: StarPlatinium

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Buy used: $15.00

Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) is a service we offer sellers that lets them store their products in Amazon's fulfillment centers, and we directly pack, ship, and provide customer service for these products. Something we hope you'll especially enjoy: FBA items qualify for FREE Shipping and Amazon Prime.

If you're a seller, Fulfillment by Amazon can help you grow your business. Learn more about the program.

Other Sellers on Amazon

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

The I-Search Paper: Revised Edition of Searching Writing Revised Edition

Purchase options and add-ons.

This revised and retitled edition of Searching Writing includes two additional I-Search papers, one by a teacher, and a new chapter entitled "The Larger Context," which shows how the I Search concept can work throughout the whole curriculum in school and college. As with the first edition, The I-Search Paper is more than just a textbook; it's a new form of instructional help -- a context book -- that shows students what authority is in matters of learning and invites them to join the author and teacher in the educational movement called "Writing to Learn."

To put this book in the hands of all the students in the course is not only to help them carry out an I-Search but to introduce them in a delightful way to the resources and tools of intellectual inquiry -- but one that never forgets the emotional or physical side of human activity.

This is a rare textbook that treats students as partners in learning. It shows what it is to take charge of one's own learning and suggests that this move is one that productive people keep making throughout their lives.

- ISBN-10 0867092238

- ISBN-13 978-0867092233

- Edition Revised

- Publisher Heinemann

- Publication date July 11, 1988

- Language English

- Dimensions 6 x 1.17 x 9 inches

- Print length 359 pages

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : Heinemann; Revised edition (July 11, 1988)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 359 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0867092238

- ISBN-13 : 978-0867092233

- Reading age : 18 years and up

- Item Weight : 1.25 pounds

- Dimensions : 6 x 1.17 x 9 inches

- #18 in Secondary Education

- #1,408 in Foreign Language Reference

- #1,924 in Instruction Methods

About the author

Ken macrorie.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

The top list of academic search engines

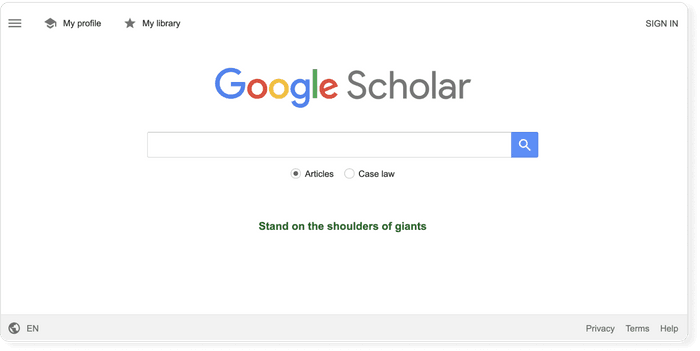

1. Google Scholar

4. science.gov, 5. semantic scholar, 6. baidu scholar, get the most out of academic search engines, frequently asked questions about academic search engines, related articles.

Academic search engines have become the number one resource to turn to in order to find research papers and other scholarly sources. While classic academic databases like Web of Science and Scopus are locked behind paywalls, Google Scholar and others can be accessed free of charge. In order to help you get your research done fast, we have compiled the top list of free academic search engines.

Google Scholar is the clear number one when it comes to academic search engines. It's the power of Google searches applied to research papers and patents. It not only lets you find research papers for all academic disciplines for free but also often provides links to full-text PDF files.

- Coverage: approx. 200 million articles

- Abstracts: only a snippet of the abstract is available

- Related articles: ✔

- References: ✔

- Cited by: ✔

- Links to full text: ✔

- Export formats: APA, MLA, Chicago, Harvard, Vancouver, RIS, BibTeX

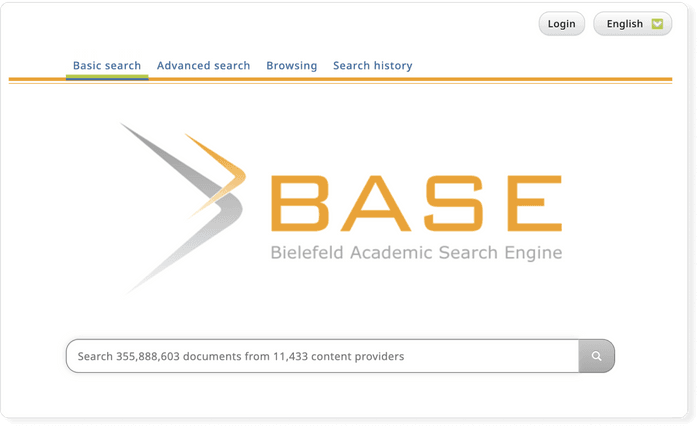

BASE is hosted at Bielefeld University in Germany. That is also where its name stems from (Bielefeld Academic Search Engine).

- Coverage: approx. 136 million articles (contains duplicates)

- Abstracts: ✔

- Related articles: ✘

- References: ✘

- Cited by: ✘

- Export formats: RIS, BibTeX

CORE is an academic search engine dedicated to open-access research papers. For each search result, a link to the full-text PDF or full-text web page is provided.

- Coverage: approx. 136 million articles

- Links to full text: ✔ (all articles in CORE are open access)

- Export formats: BibTeX

Science.gov is a fantastic resource as it bundles and offers free access to search results from more than 15 U.S. federal agencies. There is no need anymore to query all those resources separately!

- Coverage: approx. 200 million articles and reports

- Links to full text: ✔ (available for some databases)

- Export formats: APA, MLA, RIS, BibTeX (available for some databases)

Semantic Scholar is the new kid on the block. Its mission is to provide more relevant and impactful search results using AI-powered algorithms that find hidden connections and links between research topics.

- Coverage: approx. 40 million articles

- Export formats: APA, MLA, Chicago, BibTeX

Although Baidu Scholar's interface is in Chinese, its index contains research papers in English as well as Chinese.

- Coverage: no detailed statistics available, approx. 100 million articles

- Abstracts: only snippets of the abstract are available

- Export formats: APA, MLA, RIS, BibTeX

RefSeek searches more than one billion documents from academic and organizational websites. Its clean interface makes it especially easy to use for students and new researchers.

- Coverage: no detailed statistics available, approx. 1 billion documents

- Abstracts: only snippets of the article are available

- Export formats: not available

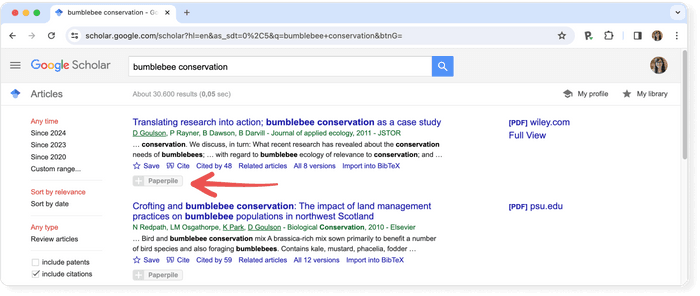

Consider using a reference manager like Paperpile to save, organize, and cite your references. Paperpile integrates with Google Scholar and many popular databases, so you can save references and PDFs directly to your library using the Paperpile buttons:

Google Scholar is an academic search engine, and it is the clear number one when it comes to academic search engines. It's the power of Google searches applied to research papers and patents. It not only let's you find research papers for all academic disciplines for free, but also often provides links to full text PDF file.

Semantic Scholar is a free, AI-powered research tool for scientific literature developed at the Allen Institute for AI. Sematic Scholar was publicly released in 2015 and uses advances in natural language processing to provide summaries for scholarly papers.

BASE , as its name suggest is an academic search engine. It is hosted at Bielefeld University in Germany and that's where it name stems from (Bielefeld Academic Search Engine).

CORE is an academic search engine dedicated to open access research papers. For each search result a link to the full text PDF or full text web page is provided.

Science.gov is a fantastic resource as it bundles and offers free access to search results from more than 15 U.S. federal agencies. There is no need any more to query all those resources separately!

- Corrections

Search Help

Get the most out of Google Scholar with some helpful tips on searches, email alerts, citation export, and more.

Finding recent papers

Your search results are normally sorted by relevance, not by date. To find newer articles, try the following options in the left sidebar:

- click "Since Year" to show only recently published papers, sorted by relevance;

- click "Sort by date" to show just the new additions, sorted by date;

- click the envelope icon to have new results periodically delivered by email.

Locating the full text of an article

Abstracts are freely available for most of the articles. Alas, reading the entire article may require a subscription. Here're a few things to try:

- click a library link, e.g., "FindIt@Harvard", to the right of the search result;

- click a link labeled [PDF] to the right of the search result;

- click "All versions" under the search result and check out the alternative sources;

- click "Related articles" or "Cited by" under the search result to explore similar articles.

If you're affiliated with a university, but don't see links such as "FindIt@Harvard", please check with your local library about the best way to access their online subscriptions. You may need to do search from a computer on campus, or to configure your browser to use a library proxy.

Getting better answers

If you're new to the subject, it may be helpful to pick up the terminology from secondary sources. E.g., a Wikipedia article for "overweight" might suggest a Scholar search for "pediatric hyperalimentation".

If the search results are too specific for your needs, check out what they're citing in their "References" sections. Referenced works are often more general in nature.

Similarly, if the search results are too basic for you, click "Cited by" to see newer papers that referenced them. These newer papers will often be more specific.

Explore! There's rarely a single answer to a research question. Click "Related articles" or "Cited by" to see closely related work, or search for author's name and see what else they have written.

Searching Google Scholar

Use the "author:" operator, e.g., author:"d knuth" or author:"donald e knuth".

Put the paper's title in quotations: "A History of the China Sea".

You'll often get better results if you search only recent articles, but still sort them by relevance, not by date. E.g., click "Since 2018" in the left sidebar of the search results page.

To see the absolutely newest articles first, click "Sort by date" in the sidebar. If you use this feature a lot, you may also find it useful to setup email alerts to have new results automatically sent to you.

Note: On smaller screens that don't show the sidebar, these options are available in the dropdown menu labelled "Year" right below the search button.

Select the "Case law" option on the homepage or in the side drawer on the search results page.

It finds documents similar to the given search result.

It's in the side drawer. The advanced search window lets you search in the author, title, and publication fields, as well as limit your search results by date.

Select the "Case law" option and do a keyword search over all jurisdictions. Then, click the "Select courts" link in the left sidebar on the search results page.

Tip: To quickly search a frequently used selection of courts, bookmark a search results page with the desired selection.

Access to articles

For each Scholar search result, we try to find a version of the article that you can read. These access links are labelled [PDF] or [HTML] and appear to the right of the search result. For example:

A paper that you need to read

Access links cover a wide variety of ways in which articles may be available to you - articles that your library subscribes to, open access articles, free-to-read articles from publishers, preprints, articles in repositories, etc.

When you are on a campus network, access links automatically include your library subscriptions and direct you to subscribed versions of articles. On-campus access links cover subscriptions from primary publishers as well as aggregators.

Off-campus access

Off-campus access links let you take your library subscriptions with you when you are at home or traveling. You can read subscribed articles when you are off-campus just as easily as when you are on-campus. Off-campus access links work by recording your subscriptions when you visit Scholar while on-campus, and looking up the recorded subscriptions later when you are off-campus.

We use the recorded subscriptions to provide you with the same subscribed access links as you see on campus. We also indicate your subscription access to participating publishers so that they can allow you to read the full-text of these articles without logging in or using a proxy. The recorded subscription information expires after 30 days and is automatically deleted.

In addition to Google Scholar search results, off-campus access links can also appear on articles from publishers participating in the off-campus subscription access program. Look for links labeled [PDF] or [HTML] on the right hand side of article pages.

Anne Author , John Doe , Jane Smith , Someone Else

In this fascinating paper, we investigate various topics that would be of interest to you. We also describe new methods relevant to your project, and attempt to address several questions which you would also like to know the answer to. Lastly, we analyze …

You can disable off-campus access links on the Scholar settings page . Disabling off-campus access links will turn off recording of your library subscriptions. It will also turn off indicating subscription access to participating publishers. Once off-campus access links are disabled, you may need to identify and configure an alternate mechanism (e.g., an institutional proxy or VPN) to access your library subscriptions while off-campus.

Email Alerts

Do a search for the topic of interest, e.g., "M Theory"; click the envelope icon in the sidebar of the search results page; enter your email address, and click "Create alert". We'll then periodically email you newly published papers that match your search criteria.

No, you can enter any email address of your choice. If the email address isn't a Google account or doesn't match your Google account, then we'll email you a verification link, which you'll need to click to start receiving alerts.

This works best if you create a public profile , which is free and quick to do. Once you get to the homepage with your photo, click "Follow" next to your name, select "New citations to my articles", and click "Done". We will then email you when we find new articles that cite yours.

Search for the title of your paper, e.g., "Anti de Sitter space and holography"; click on the "Cited by" link at the bottom of the search result; and then click on the envelope icon in the left sidebar of the search results page.

First, do a search for your colleague's name, and see if they have a Scholar profile. If they do, click on it, click the "Follow" button next to their name, select "New articles by this author", and click "Done".

If they don't have a profile, do a search by author, e.g., [author:s-hawking], and click on the mighty envelope in the left sidebar of the search results page. If you find that several different people share the same name, you may need to add co-author names or topical keywords to limit results to the author you wish to follow.

We send the alerts right after we add new papers to Google Scholar. This usually happens several times a week, except that our search robots meticulously observe holidays.

There's a link to cancel the alert at the bottom of every notification email.

If you created alerts using a Google account, you can manage them all here . If you're not using a Google account, you'll need to unsubscribe from the individual alerts and subscribe to the new ones.

Google Scholar library

Google Scholar library is your personal collection of articles. You can save articles right off the search page, organize them by adding labels, and use the power of Scholar search to quickly find just the one you want - at any time and from anywhere. You decide what goes into your library, and we’ll keep the links up to date.

You get all the goodies that come with Scholar search results - links to PDF and to your university's subscriptions, formatted citations, citing articles, and more!

Library help

Find the article you want to add in Google Scholar and click the “Save” button under the search result.

Click “My library” at the top of the page or in the side drawer to view all articles in your library. To search the full text of these articles, enter your query as usual in the search box.

Find the article you want to remove, and then click the “Delete” button under it.

- To add a label to an article, find the article in your library, click the “Label” button under it, select the label you want to apply, and click “Done”.

- To view all the articles with a specific label, click the label name in the left sidebar of your library page.

- To remove a label from an article, click the “Label” button under it, deselect the label you want to remove, and click “Done”.

- To add, edit, or delete labels, click “Manage labels” in the left column of your library page.

Only you can see the articles in your library. If you create a Scholar profile and make it public, then the articles in your public profile (and only those articles) will be visible to everyone.

Your profile contains all the articles you have written yourself. It’s a way to present your work to others, as well as to keep track of citations to it. Your library is a way to organize the articles that you’d like to read or cite, not necessarily the ones you’ve written.

Citation Export

Click the "Cite" button under the search result and then select your bibliography manager at the bottom of the popup. We currently support BibTeX, EndNote, RefMan, and RefWorks.

Err, no, please respect our robots.txt when you access Google Scholar using automated software. As the wearers of crawler's shoes and webmaster's hat, we cannot recommend adherence to web standards highly enough.

Sorry, we're unable to provide bulk access. You'll need to make an arrangement directly with the source of the data you're interested in. Keep in mind that a lot of the records in Google Scholar come from commercial subscription services.

Sorry, we can only show up to 1,000 results for any particular search query. Try a different query to get more results.

Content Coverage

Google Scholar includes journal and conference papers, theses and dissertations, academic books, pre-prints, abstracts, technical reports and other scholarly literature from all broad areas of research. You'll find works from a wide variety of academic publishers, professional societies and university repositories, as well as scholarly articles available anywhere across the web. Google Scholar also includes court opinions and patents.

We index research articles and abstracts from most major academic publishers and repositories worldwide, including both free and subscription sources. To check current coverage of a specific source in Google Scholar, search for a sample of their article titles in quotes.

While we try to be comprehensive, it isn't possible to guarantee uninterrupted coverage of any particular source. We index articles from sources all over the web and link to these websites in our search results. If one of these websites becomes unavailable to our search robots or to a large number of web users, we have to remove it from Google Scholar until it becomes available again.

Our meticulous search robots generally try to index every paper from every website they visit, including most major sources and also many lesser known ones.

That said, Google Scholar is primarily a search of academic papers. Shorter articles, such as book reviews, news sections, editorials, announcements and letters, may or may not be included. Untitled documents and documents without authors are usually not included. Website URLs that aren't available to our search robots or to the majority of web users are, obviously, not included either. Nor do we include websites that require you to sign up for an account, install a browser plugin, watch four colorful ads, and turn around three times and say coo-coo before you can read the listing of titles scanned at 10 DPI... You get the idea, we cover academic papers from sensible websites.

That's usually because we index many of these papers from other websites, such as the websites of their primary publishers. The "site:" operator currently only searches the primary version of each paper.

It could also be that the papers are located on examplejournals.gov, not on example.gov. Please make sure you're searching for the "right" website.

That said, the best way to check coverage of a specific source is to search for a sample of their papers using the title of the paper.

Ahem, we index papers, not journals. You should also ask about our coverage of universities, research groups, proteins, seminal breakthroughs, and other dimensions that are of interest to users. All such questions are best answered by searching for a statistical sample of papers that has the property of interest - journal, author, protein, etc. Many coverage comparisons are available if you search for [allintitle:"google scholar"], but some of them are more statistically valid than others.

Currently, Google Scholar allows you to search and read published opinions of US state appellate and supreme court cases since 1950, US federal district, appellate, tax and bankruptcy courts since 1923 and US Supreme Court cases since 1791. In addition, it includes citations for cases cited by indexed opinions or journal articles which allows you to find influential cases (usually older or international) which are not yet online or publicly available.

Legal opinions in Google Scholar are provided for informational purposes only and should not be relied on as a substitute for legal advice from a licensed lawyer. Google does not warrant that the information is complete or accurate.

We normally add new papers several times a week. However, updates to existing records take 6-9 months to a year or longer, because in order to update our records, we need to first recrawl them from the source website. For many larger websites, the speed at which we can update their records is limited by the crawl rate that they allow.

Inclusion and Corrections

We apologize, and we assure you the error was unintentional. Automated extraction of information from articles in diverse fields can be tricky, so an error sometimes sneaks through.

Please write to the owner of the website where the erroneous search result is coming from, and encourage them to provide correct bibliographic data to us, as described in the technical guidelines . Once the data is corrected on their website, it usually takes 6-9 months to a year or longer for it to be updated in Google Scholar. We appreciate your help and your patience.

If you can't find your papers when you search for them by title and by author, please refer your publisher to our technical guidelines .

You can also deposit your papers into your institutional repository or put their PDF versions on your personal website, but please follow your publisher's requirements when you do so. See our technical guidelines for more details on the inclusion process.

We normally add new papers several times a week; however, it might take us some time to crawl larger websites, and corrections to already included papers can take 6-9 months to a year or longer.

Google Scholar generally reflects the state of the web as it is currently visible to our search robots and to the majority of users. When you're searching for relevant papers to read, you wouldn't want it any other way!

If your citation counts have gone down, chances are that either your paper or papers that cite it have either disappeared from the web entirely, or have become unavailable to our search robots, or, perhaps, have been reformatted in a way that made it difficult for our automated software to identify their bibliographic data and references. If you wish to correct this, you'll need to identify the specific documents with indexing problems and ask your publisher to fix them. Please refer to the technical guidelines .

Please do let us know . Please include the URL for the opinion, the corrected information and a source where we can verify the correction.

We're only able to make corrections to court opinions that are hosted on our own website. For corrections to academic papers, books, dissertations and other third-party material, click on the search result in question and contact the owner of the website where the document came from. For corrections to books from Google Book Search, click on the book's title and locate the link to provide feedback at the bottom of the book's page.

General Questions

These are articles which other scholarly articles have referred to, but which we haven't found online. To exclude them from your search results, uncheck the "include citations" box on the left sidebar.

First, click on links labeled [PDF] or [HTML] to the right of the search result's title. Also, check out the "All versions" link at the bottom of the search result.

Second, if you're affiliated with a university, using a computer on campus will often let you access your library's online subscriptions. Look for links labeled with your library's name to the right of the search result's title. Also, see if there's a link to the full text on the publisher's page with the abstract.

Keep in mind that final published versions are often only available to subscribers, and that some articles are not available online at all. Good luck!

Technically, your web browser remembers your settings in a "cookie" on your computer's disk, and sends this cookie to our website along with every search. Check that your browser isn't configured to discard our cookies. Also, check if disabling various proxies or overly helpful privacy settings does the trick. Either way, your settings are stored on your computer, not on our servers, so a long hard look at your browser's preferences or internet options should help cure the machine's forgetfulness.

Not even close. That phrase is our acknowledgement that much of scholarly research involves building on what others have already discovered. It's taken from Sir Isaac Newton's famous quote, "If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants."

- Privacy & Terms

Why Easter brings me back to church

Even though i don’t practice in earnest anymore, memories and community give me a reason to return every spring, by gabriella ferrigine.

“Please — come join us in the cafeteria after Mass has concluded!”

Father Ariel’s jaunty voice echoed from where he was standing at the slabbed marble pulpit, as he smiled out at the congregation. His family, who had arrived from the Philippines in droves to celebrate his 50th birthday, beamed from the first several rows of glossy, varnished pews.

I’m not an atheist per se, but trying to find an equilibrium with faith has undoubtedly become a game of mental Tetris.

Mid-morning light filtered through stained glass depicting saints and the Stations of the Cross, casting soft pinks and blues and greens across the church: our local parish, St. James. Sun illuminated the top of Father Ariel’s head, and behind him, a domed mural of the stages of Jesus’ life — his birth in a manger, his crucifixion atop Calvary, and his resurrection after emerging from a stone sepulchre — seemed to swell higher with every slow, measured note of music from the raftered choir.

It was a Sunday morning in April, not exactly Easter but right around the time. The smell of incense — a combination of frankincense and myrrh — leached from every corner of the space, creating a somewhat soporific effect. I pictured my family, friends and neighbors gently falling asleep to its bitter, powdery aroma, like Dorothy did in the poppy field. Everything felt buoyant and peaceful.

My family and many other parishioners — mainly gentle, geriatric hordes — joined Father Ariel with his multitude of relatives in my middle-school cafeteria for an authentic Filipino feast. Side dishes of pearly quail eggs, roasted fish and meats, bright salads and an array of desserts adorned every inch of table space, the very same where I ate many peanut butter and jelly sandwiches in my youth. At the center of it all was a huge roast pig, or lechón, with delicate, crisped skin. I looked at the pig’s face, then at the people ambling around the dingy, linoleum floors, and immediately felt love.

This was nearly 10 years ago, back during a time when I went to Church every Sunday and consistently prayed to God. I don’t consider myself a particularly religious person anymore. I’m not an atheist per se, but trying to find an equilibrium with faith has undoubtedly become a game of mental Tetris. Sure, Jesus seemed like a pretty cool guy — to me, his message has always unequivocally been "love,” in a broader sense. I’m on board with that.

But I still remain immensely put off by how Catholicism’s sordid underbelly has blended into sociopolitical life, underpinning the dismantling of women’s reproductive rights and enabling sexual abusers. I find myself still clinging to it largely because it’s woven tightly into many people I love. It’s a perturbing relationship; I feel as though my continued shunning of organized religion has in a sense estranged me from the memory of some very important people.

And yet, Easter and springtime always bring me back to church. I find myself craving, not exactly the scriptures and the teachings embedded in them, but how the space evokes the memories of people I love — chiefly my maternal grandmother and my mom — and an inclusive sense of community.

A deeply spiritual person, my grandma — born in a small Bolivian jungle village called Riberalta — spent her teenage years living in a convent with a U.S.-based congregation of nuns performing foreign missionary work. She was readying to enter the sisterhood when she met my grandfather, a Sicilian and civil engineer volunteering with a Catholic mission group to help build new infrastructure in Riberalta. They returned to America together and settled in Bayonne, New Jersey, joined in a union forged out of a shared devotion to God and each other.

Though my mom didn’t pray a daily rosary or make pilgrimages to Lourdes like my grandma, she was deeply affected by her religious upbringing, a heritage she inculcated her five children with through weekly mass, and offering up nightly intentions along with prayers before dinner: family and friends who were sick or had died, poverty and homelessness, wartime conflict, our cat Sweet Pea’s hypothyroidism.

In my grandmother’s house and my own, the iconography of Jesus and other religious figures was everywhere, peppering walls and mantelpieces alongside family photos and wedding albums. Each time one of my more than 25 cousins or I received a sacrament — Baptism, First Holy Eucharist, Confirmation — a sprawling, family-wide party followed, usually at an Italian restaurant with a generically benevolent, pot-bellied owner who would toddle around and ask, “How yous all likin’ the food?” And of course, there was always a large white sheet cake, piped in bubbled fonts: “God Bless ____!”

Seeing as my mom’s eight siblings were spread out across central New Jersey, I essentially ran the gauntlet of various Catholic parishes in our area for different holidays and events. I had my favorite churches. St. James retained the top position. Then came St. Michael’s, a red-bricked church that was famous for its live-animal manger display during the Christmas season. Holy Cross — located in one of the more affluent towns in my county — had a stunning interior, but its reputation had always been somewhat sullied in my mind from a 2006 embezzlement incident .

While I was able to evade formal liturgical participation, my three younger sisters were all urged to be altar servers, helping St. James’ priests — mostly middle-aged men from the Phillippines and India — prepare and proceed with weekly Sunday mass. One sister recalled a time when she and another altar server accidentally spilled open a bag of already-consecrated Eucharist wafers as they were preparing for mass in the wood-paneled sacristy.

“Oh! Uh, don’t worry girls — I’ll consume these later,” the priest said when he walked in and saw them scooping the body of Christ off the floor and into Ziploc bags.

Another time several years ago, my family was running late for Easter Sunday mass, half of us with our hair still wet. “Overflow,” an usher posted outside the church doors said as we approached, jerking his thumb toward the rear parking lot where the grammar school was located. Given that creasters (Catholics who only attend church on Christmas and Easter) come out of the woodwork every winter and spring, tardy worshippers are forced to attend the secondary service, held in the gymnasium or auditorium.

From my seat in a metal folding chair, nostalgia washed over me as the priest carried a gold crucifix across the same floor where I’d once played dodgeball, toward the makeshift altar where I’d watched classmates act out a rendition of “The Little Mermaid.”

I feel as though my continued shunning of organized religion has in a sense estranged me from the memory of some very important people.

I spent last Easter in Newport, Rhode Island with my family for a short holiday vacation. The weekend was oceanic cliffs and Gilded Age mansions and a kaleidoscopic assortment of saltwater taffy. On Easter Sunday, we walked from our quaint bed and breakfast to St. Mary’s, Our Lady of the Isle, where JFK and Jackie O wed in September of 1953. We took turns waiting outside with our two Great Pyrenees, who had reaped the benefits of Newport’s reputation for being dog-friendly.

Ahead of the homily, the part of the service when the priest explains the Gospel reading in further detail, I elected to relieve my mom of dog duty, knowing she wouldn’t want to miss the crux of the mass.

As I turned toward the door to trade off with her, the sharp New England morning air — and an emotional pang — made me bristle. I didn’t want to leave. Mashed tightly in hard-backed pews alongside other Catholics, loyalists and creasters alike, I felt a distinct sense of calm. The very same that came to me years ago as I gazed at a pig’s snout.

This Easter, we’ll be going back to St. James. Father Ariel is no longer at the parish — I don’t know many of the priests there anymore, my connection to the parish steadily eroded by distance, time and sheer obstinance on my part. It’s an elegiac relationship, compounded by the recent passing of my grandmother, who embodied holiness and unadulterated love in every sense.

And while I may not take the time to philosophize about my salvation on Sunday, I’m certain I’ll think of her and what my being there would mean to her. For me, that’s enough to return every spring.

about this topic

- Do Christians believe Jesus was resurrected from the dead? Well, it's complicated

- The history of the Easter butter lamb, an enduring Polish tradition in the states

- Best Easter pageant ever? Half a century of "Jesus Christ Superstar"

Gabriella Ferrigine is a staff writer at Salon. Originally from the Jersey Shore, she moved to New York City in 2016 to attend Columbia University, where she received her B.A. in English and M.A. in American Studies. Formerly a staff writer at NowThis News, she has an M.A. in Magazine Journalism from NYU and was previously a news fellow at Salon.

Related Topics ------------------------------------------

Related articles.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

When I Became a Birder, Almost Everything Else Fell Into Place

Mr. Yong is a science writer whose most recent book, “An Immense World,” investigates animal perception.

Last September, I drove to a protected wetland near my home in Oakland, Calif., walked to the end of a pier and started looking at birds. Throughout the summer, I had been breaking in my first pair of binoculars, a Sibley field guide and the Merlin song-identification app, but always while hiking or walking the dog. On that pier, for the first time, I had gone somewhere solely to watch birds.

In some birding circles, people say that anyone who looks at birds is a birder — a kind, inclusive sentiment that also overlooks the forces that create and shape subcultures. Anyone can dance, but not everyone would identify as a dancer because the latter suggests if not skill then at least effort and intent. Similarly, I’ve cared about birds and other animals for my entire life, and I’ve written about them throughout my two decades as a science writer, but I mark the moment when I specifically chose to devote time and energy to them as the moment I became a birder.

Since then, my Birder Derangement Syndrome has progressed at an alarming pace. Seven months ago, I was still seeing very common birds for the first time. Since then, I’ve seen 452 species, including 337 in the United States, and 307 this year alone. I can reliably identify a few dozen species by ear. I can tell apart greater and lesser yellowlegs, house and purple finches, Cooper’s and sharp-shinned hawks. (Don’t talk to me about gulls; I’m working on the gulls.) I keep abreast of eBird’s rare bird alerts and have spent many days — some glorious, others frustrating — looking for said rare birds. I know what it means to dip, to twitch, to pish . I’ve gone owling.

I didn’t start from scratch. A career spent writing about nature gave me enough avian biology and taxonomy to roughly know the habitats and silhouettes of the major groups. Journalism taught me how to familiarize myself with unfamiliar territory very quickly. I crowdsourced tips on the social media platform Bluesky . I went out with experienced birders to learn how they move through a landscape and what cues they attend to.

I studied up on birds that are famously difficult to identify so that when I first saw them in the field, I had an inkling of what they were without having to check a field guide. I used the many tools now available to novices: EBird shows where other birders go and reveals how different species navigate space and time; Merlin is best known as an identification app but is secretly an incredible encyclopedia; Birdingquiz.com lets you practice identifying species based on fleeting glances at bad angles.

This all sounds rather extra, and birding is often defined by its excesses. At its worst, it becomes an empty process of collection that turns living things into abstract numbers on meaningless lists. But even that style of birding is harder without knowledge. To find the birds, you have to know them. And in the process of knowing them, much else falls into place.

Birding has tripled the time I spend outdoors. It has pushed me to explore Oakland in ways I never would have: Amazing hot spots lurk within industrial areas, sewage treatment plants and random residential parks. It has proved more meditative than meditation. While birding, I seem impervious to heat, cold, hunger and thirst. My senses focus resolutely on the present, and the usual hubbub in my head becomes quiet. When I spot a species for the first time — a lifer — I course with adrenaline, while being utterly serene.

I also feel a much deeper connection to the natural world, which I have long written about but always remained slightly distant from. I knew that the loggerhead shrike — a small but ferocious songbird — impales the bodies of its prey on spikes. I’ve now seen one doing that with my own eyes. I know where to find the shrikes and what they sound like. Countless fragments of unrooted trivia that rattled around my brain are now grounded in place, time and personal experience.

When I step out my door in the morning, I take an aural census of the neighborhood, tuning in to the chatter of creatures that were always there and that I might previously have overlooked. The passing of the seasons feels more granular, marked by the arrival and disappearance of particular species instead of much slower changes in day length, temperature and greenery. I find myself noticing small shifts in the weather and small differences in habitat. I think about the tides.

So much more of the natural world feels close and accessible now. When I started birding, I remember thinking that I’d never see most of the species in my field guide. Sure, backyard birds like robins and Western bluebirds would be easy, but not black skimmers, or peregrine falcons or loggerhead shrikes. I had internalized the idea of nature as distant and remote — the province of nature documentaries and far-flung vacations. But in the last six months, I’ve seen soaring golden eagles, heard duetting great horned owls, watched dancing sandhill cranes and marveled at diving Pacific loons, all within an hour of my house. “ I’ll never see that ” has turned into “ Where can I find that? ”

Of course, having the time to bird is an immense privilege. As a freelancer, I have total control over my hours and my ability to get out in the field. “Are you a retiree?” a fellow birder recently asked me. “You’re birding like a retiree.” I laughed, but the comment spoke to the idea that things like birding are what you do when you’re not working, not being productive.

I reject that. These recent years have taught me that I’m less when I’m not actively looking after myself, that I have value to my world and my community beyond ceaseless production, and that pursuits like birding that foster joy, wonder and connection to place are not sidebars to a fulfilled life but their essence.

It’s easy to think of birding as an escape from reality. Instead, I see it as immersion in the true reality. I don’t need to know who the main characters are on social media and what everyone is saying about them, when I can instead spend an hour trying to find a rare sparrow. It’s very clear to me which of those two activities is the more ridiculous. It’s not the one with the sparrow.

More of those sparrows are imminent. I’m about to witness my first spring migration as warblers and other delights pass through the Bay Area. Birds I’ve seen only in drab grays are about to don their spectacular breeding plumages. Familiar species are about to burst out in new tunes that I’ll have to learn. I have my first lazuli bunting to see, my first blue grosbeak to find, my first least terns to photograph. I can’t wait.

Ed Yong is a science writer whose most recent book, “An Immense World,” investigates animal perception.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , WhatsApp , X and Threads .

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

Conservatives Are Getting Comfortable Talking Openly About a National Abortion Ban

After this week’s oral argument, few court watchers believe the Supreme Court is now ready to limit the Food and Drug Administration’s authority to approve mifepristone , a drug used in more than half of all abortions , as opponents of abortion sought. At oral argument in FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine , it did not appear that the plaintiff doctors persuaded the court that the law inflicted injuries that would give them standing to sue. The reason for the justices’ skepticism is not hard to find. The doctors built their case on a mountain of remote possibilities. Patients might suffer complications from mifepristone—a drug with an impressively low complication rate—and might seek treatment at emergency rooms, where the plaintiffs may happen to practice, when the plaintiffs might not be able to find another physician willing to intervene. And all of that might mean that the plaintiffs would have to act in violation of their conscience. But then again, it might not. That’s why this case seems dead on arrival: The justices seemed unwilling to engage in the sort of rank speculation the plaintiffs have in mind. If this chain of hypotheticals is enough, anyone can bring a constitutional challenge to any drug approval or any law.

But the case was also a vehicle for advancing ever more expansive conscience-based arguments that have become common currency among Christian conservatives—claims of the kind we have seen in well-known cases like the 2014 Hobby Lobby decision recognizing conscience objections to the contraceptive mandate of the Affordable Care Act or even last year’s ruling in 303 Creative v. Elenis that allowed a conservative Christian graphic designer to refuse to make custom websites for same-sex weddings.

Today, those with conscience-based objections seek more than to pray or dress in conformity with religious belief. They object to laws providing Americans access to health care or freedom from discrimination. Compliance with these laws, they claim, would make the objector complicit in the assertedly sinful conduct of others.

Objectors bringing this new generation of complicity-based conscience claims invite courts to deny other Americans the protections of the law. In the FDA case, the plaintiffs do not even seek an exemption from the law; through an expansive standing claim, the doctors claim the only way the court could protect their conscience is to strike down FDA approvals providing all Americans access to medication abortion. Simply having mifepristone on the market, they argue, risks making them complicit in abortion.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson zeroed in on the problems with this argument. She observed that Erin Hawley, the attorney for the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, had identified a “broad” and “narrow” idea of conscience. The “narrow” reading was straightforward: “participating in a procedure.” This reading had problems of its own: In fact, no doctor was obliged to prescribe mifepristone, and in any event, federal law provides doctors conscience protections.

Yet Hawley didn’t think complicity ended there. Jackson seemed confused. Did Hawley mean that a handful of other doctors who participated in post-abortion procedures, such as the removal of tissue, were also complicit? Or was Hawley asking the court to recognize the complicity claims of someone who worked in an emergency room where abortions took place, or handed an abortion provider a water bottle?