Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Americans’ complicated feelings about social media in an era of privacy concerns.

Amid public concerns over Cambridge Analytica’s use of Facebook data and a subsequent movement to encourage users to abandon Facebook , there is a renewed focus on how social media companies collect personal information and make it available to marketers.

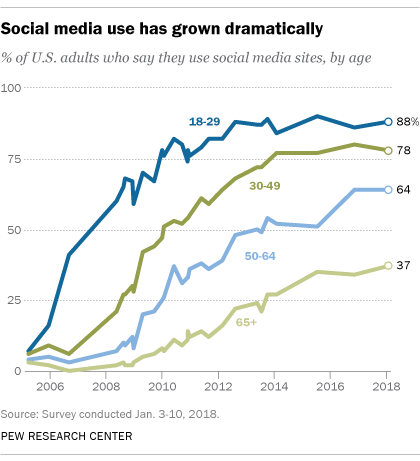

Pew Research Center has studied the spread and impact of social media since 2005, when just 5% of American adults used the platforms. The trends tracked by our data tell a complex story that is full of conflicting pressures. On one hand, the rapid growth of the platforms is testimony to their appeal to online Americans. On the other, this widespread use has been accompanied by rising user concerns about privacy and social media firms’ capacity to protect their data.

All this adds up to a mixed picture about how Americans feel about social media. Here are some of the dynamics.

People like and use social media for several reasons

The Center’s polls have found over the years that people use social media for important social interactions like staying in touch with friends and family and reconnecting with old acquaintances. Teenagers are especially likely to report that social media are important to their friendships and, at times, their romantic relationships .

Beyond that, we have documented how social media play a role in the way people participate in civic and political activities, launch and sustain protests , get and share health information , gather scientific information , engage in family matters , perform job-related activities and get news . Indeed, social media is now just as common a pathway to news for people as going directly to a news organization website or app.

Our research has not established a causal relationship between people’s use of social media and their well-being. But in a 2011 report, we noted modest associations between people’s social media use and higher levels of trust, larger numbers of close friends, greater amounts of social support and higher levels of civic participation.

People worry about privacy and the use of their personal information

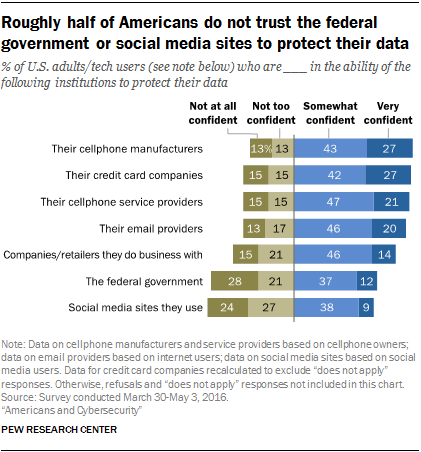

While there is evidence that social media works in some important ways for people, Pew Research Center studies have shown that people are anxious about all the personal information that is collected and shared and the security of their data.

Overall, a 2014 survey found that 91% of Americans “agree” or “strongly agree” that people have lost control over how personal information is collected and used by all kinds of entities. Some 80% of social media users said they were concerned about advertisers and businesses accessing the data they share on social media platforms, and 64% said the government should do more to regulate advertisers.

Moreover, people struggle to understand the nature and scope of the data collected about them. Just 9% believe they have “a lot of control” over the information that is collected about them, even as the vast majority (74%) say it is very important to them to be in control of who can get information about them.

Six-in-ten Americans (61%) have said they would like to do more to protect their privacy. Additionally, two-thirds have said current laws are not good enough in protecting people’s privacy, and 64% support more regulation of advertisers.

Some privacy advocates hope that the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation , which goes into effect on May 25, will give users – even Americans – greater protections about what data tech firms can collect, how the data can be used, and how consumers can be given more opportunities to see what is happening with their information.

People’s issues with the social media experience go beyond privacy

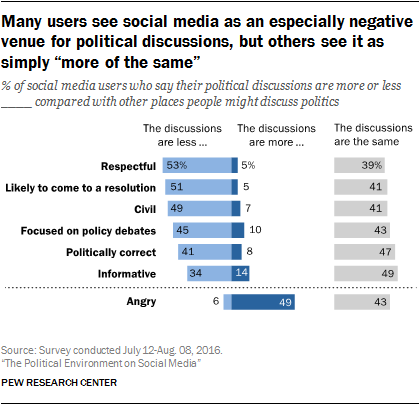

In addition to the concerns about privacy and social media platforms uncovered in our surveys, related research shows that just 5% of social media users trust the information that comes to them via the platforms “a lot.”

A considerable number of social media users said they simply ignored political arguments when they broke out in their feeds. Others went steps further by blocking or unfriending those who offended or bugged them.

Why do people leave or stay on social media platforms?

The paradox is that people use social media platforms even as they express great concern about the privacy implications of doing so – and the social woes they encounter. The Center’s most recent survey about social media found that 59% of users said it would not be difficult to give up these sites, yet the share saying these sites would be hard to give up grew 12 percentage points from early 2014.

Some of the answers about why people stay on social media could tie to our findings about how people adjust their behavior on the sites and online, depending on personal and political circumstances. For instance, in a 2012 report we found that 61% of Facebook users said they had taken a break from using the platform. Among the reasons people cited were that they were too busy to use the platform, they lost interest, they thought it was a waste of time and that it was filled with too much drama, gossip or conflict.

In other words, participation on the sites for many people is not an all-or-nothing proposition.

People pursue strategies to try to avoid problems on social media and the internet overall. Fully 86% of internet users said in 2012 they had taken steps to try to be anonymous online. “Hiding from advertisers” was relatively high on the list of those they wanted to avoid.

Many social media users fine-tune their behavior to try to make things less challenging or unsettling on the sites, including changing their privacy settings and restricting access to their profiles. Still, 48% of social media users reported in a 2012 survey they have difficulty managing their privacy controls.

After National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden disclosed details about government surveillance programs starting in 2013, 30% of adults said they took steps to hide or shield their information and 22% reported they had changed their online behavior in order to minimize detection.

One other argument that some experts make in Pew Research Center canvassings about the future is that people often find it hard to disconnect because so much of modern life takes place on social media. These experts believe that unplugging is hard because social media and other technology affordances make life convenient and because the platforms offer a very efficient, compelling way for users to stay connected to the people and organizations that matter to them.

Note: See topline results for overall social media user data here (PDF).

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

Social Media Fact Sheet

7 facts about americans and instagram, social media use in 2021, 64% of americans say social media have a mostly negative effect on the way things are going in the u.s. today, share of u.s. adults using social media, including facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Social Media and Lack of Privacy

Social media has presented different platforms where families and friends can connect despite other geographical locations. Social media users relate to various platforms using their devices and share moments or ideas in economics, politics, or even business. Although social media has made the world a smaller place, it has fallbacks. This paper will look at how social media has hugely caused a lack of privacy.

Social media users tend to post issues concerning their private lives or public matters. For years now, social media privacy has been an issue. There are numerous reports about data breaches, causing social media users to be more cautious about their privacy. The data breaches have led to a lack of trust and raised suspicions among the users whether they have lost control over their information.

The number of social media users is rising, making them vulnerable to different forms of security breaches. When private information gets unauthorized, the impacts can be grave. According to Pew Research center (2017), about 13% of online users in the U.S. have reported their accounts hacked by unauthorized users. These hacks can cause redirects and malware of various types, which would cause vulnerability to evil deeds.

Sharing private information may cause judgments by the public. Social media users can ruin or build their reputations, depending on their activities on these platforms. They can do this through their relationships and influence from other people using similar platforms. Therefore, some people can be subject to unfair judgments or misunderstandings resulting from a small portion of one’s story (Rahman et al., 2019).

The different types of social media threats include phishing, data mining, and malware. Phishing is among the most common ways criminals gather private information from social media users. Phishing attacks come in calls, emails, or text messages from a legitimate institution. The statements or calls may trick users into sharing sensitive and private information like passwords or bank information.

Data mining is extracting helpful information from a large data set. Online users open new social media accounts almost every day, meaning that every social media user leaves a stream of data. Social media platforms require personal information such as name, date of birth, personal interests, or location (Rahman et al., 2019). Similarly, different firms use the information to obtain data based on how, where, and when users are active on their platforms. The data obtained will enable companies to understand their target markets and improve their advertising methods. It can be worse as firms may share the data with third parties without the users’ knowledge. Finally, malware is suspicious software designed to attack computers and gain information that they contain. If malware is successfully installed in a user’s computer, then all the information and data can be stolen (Rahman et al., 2019). Social media platforms are potential delivery systems for various malware. Compromising one account can spread the malware to friends and contacts by taking charge of the account.

To conclude, social media privacy continues to be in question as different forms of hacking and data breaches are introduced. The youths and young people are the most vulnerable to such insecurities as they never take the matter seriously. Also, these youngsters are more influenced by their peers than adults or parents, hence exposing them to insecurities. Social media users are urged to avoid sharing sensitive information or conceal information that they do not feel comfortable sharing.

Americans and Cyber Security . (2017, January 16). Pew Research Center.

Rahman, H. U., Rehman, A. U., Nazir, S., Rehman, I. U., & Uddin, N. (2019, March). Privacy and security—limits of personal information to minimize loss of privacy. In Future of Information and Communication Conference (pp. 964-974). Springer, Cham.

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Related Essays

Cultural appropriation or can anybody own a culture, critical analysis essay on death of a salesman, hypothetical production of macbeth, battle of palo alto, the uniqueness of the holocaust, the great gatsby novel, popular essay topics.

- American Dream

- Artificial Intelligence

- Black Lives Matter

- Bullying Essay

- Career Goals Essay

- Causes of the Civil War

- Child Abusing

- Civil Rights Movement

- Community Service

- Cultural Identity

- Cyber Bullying

- Death Penalty

- Depression Essay

- Domestic Violence

- Freedom of Speech

- Global Warming

- Gun Control

- Human Trafficking

- I Believe Essay

- Immigration

- Importance of Education

- Israel and Palestine Conflict

- Leadership Essay

- Legalizing Marijuanas

- Mental Health

- National Honor Society

- Police Brutality

- Pollution Essay

- Racism Essay

- Romeo and Juliet

- Same Sex Marriages

- Social Media

- The Great Gatsby

- The Yellow Wallpaper

- Time Management

- To Kill a Mockingbird

- Violent Video Games

- What Makes You Unique

- Why I Want to Be a Nurse

- Send us an e-mail

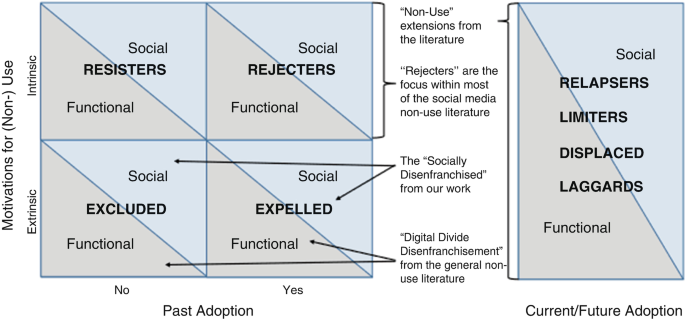

Modern Socio-Technical Perspectives on Privacy pp 113–147 Cite as

Social Media and Privacy

- Xinru Page 7 ,

- Sara Berrios 7 ,

- Daricia Wilkinson 8 &

- Pamela J. Wisniewski 9

- Open Access

- First Online: 09 February 2022

16k Accesses

4 Citations

4 Altmetric

With the popularity of social media, researchers and designers must consider a wide variety of privacy concerns while optimizing for meaningful social interactions and connection. While much of the privacy literature has focused on information disclosures, the interpersonal dynamics associated with being on social media make it important for us to look beyond informational privacy concerns to view privacy as a form of interpersonal boundary regulation. In other words, attaining the right level of privacy on social media is a process of negotiating how much, how little, or when we desire to interact with others, as well as the types of information we choose to share with them or allow them to share about us. We propose a framework for how researchers and practitioners can think about privacy as a form of interpersonal boundary regulation on social media by introducing five boundary types (i.e., relational, network, territorial, disclosure, and interactional) social media users manage. We conclude by providing tools for assessing privacy concerns in social media, as well as noting several challenges that must be overcome to help people to engage more fully and stay on social media.

Download chapter PDF

1 Introduction

The way people communicate with one another in the twenty-first century has evolved rapidly. In the 1990s, if someone wanted to share a “how-to” video tutorial within their social networks, the dissemination options would be limited (e.g., email, floppy disk, or possibly a writeable compact disc). Now, social media platforms, such as TikTok, provide professional grade video editing and sharing capabilities that give users the potential to both create and disseminate such content to thousands of viewers within a matter of minutes. As such, social media has steadily become an integral component for how people capture aspects of their physical lives and share them with others. Social media platforms have gradually altered the way many people live [ 1 ], learn [ 2 , 3 ], and maintain relationships with others [ 4 ].

Carr and Hayes define social media as “Internet-based channels that allow users to opportunistically interact and selectively self-present, either in real time or asynchronously, with both broad and narrow audiences who derive value from user-generated content and the perception of interaction with others” [ 5 ]. Social media platforms offer new avenues for expressing oneself, experiences, and emotions with broader online communities via posts, tweets, shares, likes, and reviews. People use these platforms to talk about major milestones that bring happiness (e.g., graduation, marriage, pregnancy announcements), but they also use social media as an outlet to express grief and challenges, and to cope with crises [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Many scholars have highlighted the host of positive outcomes from interpersonal interactions on social media including social capital, self-esteem, and personal well-being [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Likewise, researchers have also shed light on the increased concerns over unethical data collection and privacy abuses [ 13 , 14 ].

This chapter highlights the privacy issues that must be addressed in the context of social media and provides guidance on how to study and design for social media privacy. We first provide an overview of the history of social media and its usage. Next, we highlight common social media privacy concerns that have arisen over the years. We also point out how scholars have identified and sought to predict privacy behavior, but many efforts have failed to adequately account for individual differences. By reconceptualizing privacy in social media as a boundary regulation, we can explain these gaps from previous one-size-fits-all approaches and provide tools for measuring and studying privacy violations. Finally, we conclude with a word of caution about the consequences of ignoring privacy concerns on social media.

2 A Brief History of Social Media

Section highlights.

Social media use has quickly increased over the past decade and plays a key role in social, professional, and even civic realms. The rise of social media has led to “networked individualism.”

This enables people to access a wider variety of specialized relationships , making it more likely they can meet a variety of needs. It also allows people to project their voice to a wider audience.

However, people have more frequent turnover in their social networks , and it takes much more effort to maintain social relations and discern (mis)information and intention behind communication.

The initial popularity of social media harkened back to the historical rise of social network sites (SNSs). The canonical definition of SNSs is attributed to Boyd and Ellison [ 15 ] who differentiate SNSs from other forms of computer-mediated communication. According to Boyd and Ellison, SNS consists of (1) profiles representing users and (2) explicit connections between these profiles that can be traversed and interacted with. A social networking profile is a self-constructed digital representation of oneself and one’s social relationships. The content of these profiles varies by platform from profile pictures to personal information such as interests, demographics, and contact information. Visibility also varies by platform and often users have some control over who can see their profile (e.g., everyone or “friends”). Most SNSs also provide a way to leave messages on another’s profile, such as posting to someone’s timeline on Facebook or sending a mention or direct message to someone on Twitter.

Public interest and research initially focused on a small subset of SNSs (e.g., Friendster [ 16 ] and MySpace [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]), but the past decade has seen the proliferation of a much broader range of social networking technologies, as well as an evolution of SNSs into what Kane et al. term social media networks [ 20 ]. This extended definition emphasizes the reach of social media content beyond a single platform. It acknowledges how the boundedness of SNSs has become blurred as platform functionality that was once contained in a single platform, such as “likes,” are now integrated across other websites, third parties, and mobile apps.

Over the past decade, SNSs and social media networks have quickly become embedded in many facets of personal, professional, and social life. In that time, these platforms became more commonly known as “social media.” In the USA, only 5% of adults used social media in 2005. By 2011, half of the US adult population was using social media, and 72% were social users by 2019 [ 21 ]. MySpace and Facebook dominated SNS research about a decade ago, but now other social media platforms, such as YouTube, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, Kik, TikTok, and others, are popular choices among social media users. The intensity of use also has drastically increased. For example, half of Facebook users log on several times a day, and three-quarters of Facebook users are active on the platform at least daily [ 21 ]. Worldwide, Facebook alone has 1.59 billion users who use it on a daily basis and 2.41 billion using it at least monthly [ 22 ]. About half of the users of other popular platforms such as Snapchat, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube also report visiting those sites daily. Around the world, there are 4.2 billion users who spend a cumulative 10 billion hours a day on social networking sites [ 23 ]. However, different social networking sites are dominant in different cultures. For example, the most popular social media in China, WeChat (inc. Wēixìn 微信), has 1.213 billion monthly users [ 23 ].

While SNS profiles started as a user-crafted representation of an individual user, these profiles now also often consist of information that is passively collected, aggregated, and filtered in ways that are ambiguous to the user. This passively collected information can include data accessed through other avenues (e.g., search engines, third-party apps) beyond the platform itself [ 24 ]. Many people fail to realize that their information is being stored and used elsewhere. Compared to tracking on the web, social media platforms have access to a plethora of rich data and fine-grained personally identifiable information (PII) which could be used to make inferences about users’ behavior, socioeconomic status, and even their political leanings [ 25 ]. While online tracking might be valuable for social media companies to better understand how to target their consumers and personalize social media features to users’ preferences, the lack of transparency regarding what and how data is collected has in more recent years led to heightened privacy concerns and skepticism around how social media platforms are using personal data [ 26 , 27 , 28 ]. This has, in turn, contributed to a loss of trust and changes in how people interact (or not) on social media, leading some users to abandon certain platforms altogether [ 26 , 29 ] or to seek alternative social media platforms that are more privacy focused.

For example, WhatsApp, a popular messaging app, updated its privacy policy to allow its parent company, Facebook, and its subsidiaries to collect WhatsApp data [ 30 ]. Users were given the option to accept the terms or lose access to the app. Shortly after, WhatsApp rival Signal reported 7.5 million installs globally over 4 days. Recent and multiple social media data breaches have heightened people’s awareness around potential inferences that could be made about them and the danger in sensitive privacy breaches. Considering the invasive nature of such practices, both consumers and companies are increasingly acknowledging the importance of privacy, control, and transparency in social media [ 31 ]. Similarly, as researchers and practitioners, we must acknowledge the importance of privacy on social media and design for the complex challenges associated with networked privacy. These types of intrusions and data privacy issues are akin to the informational privacy issues that have been investigated in the context of e-commerce, websites, and online tracking (see Chap. 9 ).

While early research into social media and privacy largely focused on these types of concerns, researchers have uncovered how the social dynamics surrounding social media have led to a broader array of social privacy issues that shape people’s adoption of platforms and their usage behaviors. Rainie and Wellman explain how the rise of social technologies, combined with ubiquitous Internet and mobile access, has led to the rise of “networked individualism” [ 32 ]. People have access to a wider variety of relationships than they previously did offline in a geographically and time-bound world. These new opportunities make it more likely that people can foster relationships that meet their individual needs for havens (support and belonging), bandages (coping), safety nets (protect from crisis), and social capital (ability to survive and thrive through situation changes). Additionally, social media users can project their voice to an extended audience, including many weak ties (e.g., acquaintances and strangers). This enables individuals to meet their social, emotional, and economic needs by drawing on a myriad of specialized relationships (different individuals each particularly knowledgeable in a specific domain such as economics, politics, sports, caretaking). In this way, individuals are increasingly networked or embedded within multiple communities that serve their interests and needs.

Inversely, networked individualism has also made people less likely to have a single “home” community, dealing with more frequent turnover and change in their social networks. Rainie and Wellman describe how people’s social routines are different from previous generations that were more geographically bound – today, only 10% of people’s significant ties are their neighbors [ 32 ]. As such, researchers have questioned and studied the extent to which people can meaningfully maintain interpersonal relationships on social media. The upper limit for doing so has been estimated at 150 connections or “friends” [ 33 ], but social media connections often well exceed this number. With such large networks, it also takes users much more effort to distinguish (mis)information, when communication is intended for the user, and the intent behind that communication. The technical affordances of social media can also help or hinder their (in)ability to capture the nuances of the various relationships in their social network. On many social media platforms, relationships are flattened into friends and followers, making them homogenous and lacking differentiation between, for instance, casual acquaintance and trusted confidant [ 16 , 34 ]. These characteristics of social media lead to a host of social privacy issues which are crucial to address. In the next section, we summarize some of the key privacy challenges that arise due to the unique characteristics of social media.

3 Privacy Challenges in Social Media

Information disclosure privacy issues have been a dominant focus in online technologies and the primary focus for social media. It focuses on access to data and defining public vs. private disclosures . It emphasizes user control over who sees what.

With so many people from different social circles able to access a user’s social media content, the issues of context collapse occur. Users may post to an imagined audience rather than realizing that people from multiple social contexts are privy to the same information.

The issues of self-presentation jump to the foreground in social media. Being able to manage impressions is a part of privacy management.

The social nature of social media also introduces the issues of controlling access to oneself , both in terms of availability and physical access.

Despite all of these privacy concerns, there is a noted privacy paradox between what people say they are concerned about and their resulting behaviors online.

Early focus of social media privacy research was focused on helping individuals meet their privacy needs in light of four key challenges: (1) information disclosure, (2) context collapse, (3) reputation management, and (4) access to oneself. This section gives an overview of these privacy challenges and how research sought to overcome them. The remainder of this chapter shows how the research has moved beyond focusing on the individual when it comes to social media and privacy; rather, social media privacy has been reconceptualized as a dynamic process of interpersonal boundary regulation between individuals and groups.

3.1 Information Disclosure/Control over Who Sees What

A commonality among early social media privacy research is that the focus has been on information privacy and self-disclosure [ 35 ]. Self-disclosure is the information a person chooses to share with other people or websites, such as posting a status update on social media. Information privacy breaches occur when a website and/or person leaks private information about a user, sometimes unintentionally. Many studies have focused on informational privacy and on sharing information with, or withholding it from, the appropriate people [ 36 , 37 , 38 ] on social media. Privacy settings related to self-disclosure have also been studied in detail [ 39 , 40 , 41 ]. Generally, social media platforms help users control self-disclosure in two ways. First is the level of granularity or type of information that one can share with others. Facebook is the most complex, allowing users to disclose and control more granular information for profile categories such as bio, website, email addresses, and at least eight other categories at the time of writing this chapter. Others have fewer information groupings, which make user profiles chunkier, and thus self-disclosure boundaries less granular. The second dimension is one’s access level permissions, or with whom one can share personal information. The most popular social media platforms err on the side of sharing more information to more people by allowing users to give access to categories such as “Everyone,” “All Users,” or “Public.” Similarly, many social media platforms give the option for access for “friends” or “followers” only.

Many researchers have highlighted how disclosures can be shared more widely than intended. Tufekci examined disclosure mechanisms used by college students on MySpace and Facebook to manage the boundary between private and public. Findings suggest that students are more likely to adjust profile visibility rather than limiting their disclosures [ 42 ]. Other research points out how users may not want their posts to remain online indefinitely, but most social media platforms default to keeping past posts visible unless the user specifies otherwise [ 43 ]. Even when the platform offers ways to limit post sharing, there are often intentional and unintentional ways this content is shared that negates the users’ wishes. For example, Twitter is a popular social media platform where users can choose to have their tweets available only to their followers. However, millions of private tweets have been retweeted, exposing private information to the public [ 44 ]. Even platforms like Snapchat, which make posts ephemeral by default, are susceptible to people taking screenshots of a snap and distributing through other channels. Thus, as social media companies continue to develop social media platforms, they should consider how to protect users from information disclosure and teach people to practice privacy protective habits.

Although some users adjust their privacy settings to limit information disclosures, they may be unaware of third-party sites that can still access their information. Scholars have emphasized the importance of educating users on the secondary use of their data, such as when third-party software takes information from their profiles [ 45 ]. Data surveillance continues to expand, and the business model of social media corporations tends to favor getting more information about users, which makes it difficult for users that want to control their disclosure [ 46 ]. Third-party apps can also access information about social media users’ connections without consent of the person whose information is being stored [ 47 ].

3.2 Unique Considerations for Managing Disclosures Within Social Media

As mentioned earlier, social media can expand a person’s network, but as that network expands and diversifies, users have less control over how their personal information is shared with others. Two unique privacy considerations for social media that arise from this tension are context collapse and imagined audiences, which we describe in more detail in the subsections below. For example, as Facebook has become a social gathering place for adults, one’s “friends” may include family members, coworkers, colleagues, and acquaintances all in one virtual social sphere. Social media users may want to share information with these groups but are concerned about which audiences are appropriate for sharing what types of information. This is because these various social spheres that intersect on Facebook may not intersect as readily in the physical world (e.g., college buddies versus coworkers) [ 48 ]. These distinct social circles are brought together into one space due to social media. This concept is referred to as “context collapse” since a user’s audience is no longer limited to one context (e.g., home, work, school) [ 15 , 49 , 50 ]. We highlight research on the phenomenon of the privacy paradox and explain how context collapse and imagined audiences may help explain the apparent disconnect between users’ stated privacy concerns and their actual privacy behavior.

Context Collapse

Nuanced differences between one’s relationships are not fully represented on social media. While real-life relationships are notorious for being complex, one of the biggest criticisms of social media platforms is that they often simplify relationships to a “binary” [ 51 ] or “monolithic” [ 52 ] dimension of either friend or not friend. Many platforms just have one type of relationship such as a “friend,” and all relationships are treated the same. Once a “friend” has been added to one’s network, maintaining appropriate levels of social interactions in light of one’s relationship context with this individual (and the many others within one’s network) becomes even more problematic [ 53 ]. Since each friend may have different and, at times, mutually exclusive expectations, acting accordingly within a single space has become a challenge. As Boyd points out, for instance, teenagers cannot be simultaneously cool to their friends and to their parents [ 53 ]. Due to this collapsed context of relationships within social media, acquaintances, family, friends, coworkers, and significant others all have the same level of access to a social media user once added to one’s network – unless appropriately managed.

Research reveals that the way people manage context collapses varies. Working professionals might deal with context collapse by limiting posts containing personal information, creating different accounts, and avoiding friending those they worked with [ 54 ]. As another example, many adolescents manage context collapse by keeping their family members separate from their personal accounts [ 55 ]. Other mechanisms for managing context collapse include access-level permission to request friendship, denying friend requests, and unfriending. While there is limited support for manually assigning different privileges to each friend, the default is to start out the same and many users never change those defaults.

Privacy incidents resulting from mixing work and social media show the importance of why context collapse must be addressed. Context collapse has been shown to negatively affect those seeking employment [ 56 ], as well as endangering those who are employed. For example, a teacher in Massachusetts lost her job because she did not realize her Facebook posts were public to those who were not her friends; her complaints about parents of students getting her sick led to her getting fired from her job [ 57 ]. Many others have shared anecdotes about being fired after controversial Facebook and Twitter posts [ 58 , 59 ]. Even celebrities who live in the public eye can suffer from context collapse [ 60 , 61 ]. Kim Kardashian, for example, received intense criticism from Internet fans when she posted a photo on social media of her daughter using a cellphone and wearing makeup while Kim was getting ready for hair and wardrobe [ 62 ]. Many online users criticized her parenting style for not limiting screen time and Kim subsequently shared a photo of a stack of books that the kids have access to while she works.

Nevertheless, context collapse can also increase bridging social capital, which is the potential social benefit that can come through having ties to a wider audience. Context collapse enables this to occur by allowing people to increase their connections to weak ties and creating serendipitous situations by sharing with people beyond whom one would normally share [ 60 ]. For example, job hunters may increase their chances of finding a job by using social media to network and connect with those they would not normally be associated with on a daily basis. Getting out a message or spreading the word can also be accomplished more easily. For instance, finding people to contribute to natural disaster funds can be effective on social media because multiple contexts can be easily reached from one account [ 63 ]. In addition to managing context collapse, social media users also have to anticipate whether they are sharing disclosures with their intended audiences.

Imagined Audiences

The disconnect between the real audience and the imagined audience on social media poses privacy risks. Understanding who can see what content, how, when, and where is key to deciding what content to share and under what circumstances. Yet, research has consistently demonstrated how users do not accurately anticipate who can potentially see their posts. This manifests as wrongly anticipating that a certain person can see content (when they cannot), as well as not realizing when another person can access posted content. Users have an “imagined audience” [ 64 , 65 ] to whom they are posting their content, but it often does not match the actual audience viewing the user’s content. Social media users typically imagine that the audience for their social media posts are like-minded people, such as family or close friends [ 65 ]. Sometimes, online users think of specific people or groups when creating content such as a daughter, coworkers, people who need cleaning tips, or even one’s deceased father [ 65 ]. Despite these imagined audiences, privacy settings may be set so that many more people can see these posts (acquaintances, strangers, etc.). While users do tend to limit who sees their profile to a defined audience [ 44 , 66 , 67 ], they still tend to believe their posts are more private than they actually are [ 49 , 68 ].

Some users adopt privacy management strategies to counter potential mismatch in audience. Vitak identified several privacy management tactics users employ to disclose information to a limited audience [ 69 ]:

Network-based . Social media users decide who to friend or follow, therefore filtering their network of people. Some Facebook users avoid friending people they do not know. Others set friends’ profiles to “hidden,” so that they do not have to see their posts, but avoid the negative connotations associated with “unfriending.”

Platform-based . Some users choose to use the social media sites’ privacy settings to control who sees their posts. A common approach on Facebook is to change the setting to be “friends only,” so that only a user’s friends may see their posts.

Content-based . These users control their privacy by being careful about the information they post. If they knew that an employer could see their posts, then they would avoid posting when they were at work.

Profile-based . A less commonly used approach is to create multiple accounts (on a single platform or across platforms). For example, a professional, personal, and fun account.

As another example, teenagers often navigate public platforms by posting messages that parents or others would not understand their true meaning. For instance, by posting a song lyric or quote that is only recognized by specific individuals as a reference to a specific movie scene or ironic message, they therefore creatively limit their audience [ 49 , 70 ]. Others manage their audience by using more self-limiting privacy tactics like self-censorship [ 70 ], choosing just to not post something they were considering in the first place. These various tactics allow users to control who can see what on social media in different ways.

3.3 Reputation Management Through Self-Presentation

Technology-mediated interactions have led to new ways of managing how we present ourselves to different groups of friends (e.g., using different profiles on the same platform based on the audience) [ 71 ]. Being able to control the way we come across to others can be a challenging privacy problem that social media users must learn to navigate. Features to limit audience can also help with managing self-presentation. Nonetheless, reputation or impression management is not just about avoiding posts or limiting access to content. Posting more content, such as selfies, is another approach used to control the way others perceive a user [ 72 ]. In this case, it is important to present the content that helps convey a certain image of oneself. Research has revealed that those who engage more in impression management tend to have more online friends and disclose more personal information [ 73 ]. Those who feel online disclosures could leave them vulnerable to negativity, such as individuals who identify as LGBTQ+, have also been found to put an emphasis on impression management in order to navigate their online presence [ 74 ]. However, studies still show that users have anxieties around not having control over how they are presented [ 75 ]. Social media users worry not only about what they post, but are concerned about how others’ postings will reflect on them [ 42 ].

Another dimension that affects impression management attitudes is how social media platforms vary in their policies on whether user profiles must be consistent with their offline identities. Facebook’s real name policy, for instance, requires that people use their real name and represent themselves as one person, corresponding to their offline identities. Research confirms that online profiles actually do reflect users’ authentic personalities [ 76 ]. However, some platforms more easily facilitate identity exploration and have evolved norms encouraging it. For example, Finsta accounts popped up on Instagram a few years after the company started. These accounts are “Fake Instagram” accounts often sharing content that the user does not want to associate with their more public identity, allowing for more identity exploration. This may have arisen from the social norm that has evolved where Instagram users often feel like they need to present an ideal self. Scholars have observed such pressure on Instagram more than on other platforms like Snapchat [ 77 ]. While the ability to craft an online image separate from one’s offline identity may be more prevalent on platforms like Instagram, certain types of social media such as location-sharing social networks are deeply tied to one’s offline self, sharing actual physical location of its users. Users of Foursquare, a popular location-sharing app, have leveraged this tight coupling for impression management. Scholars have observed that users try to impress their friends or family members about the places they spend their time while skipping “check-in” at places like McDonald’s or work for fear of appearing boring or unimpressive [ 78 ].

Regardless of how tightly one’s online presence corresponds with their offline identity, concerns about self-presentation can arise. For example, users may lie about their location on location-sharing platforms as an impression management tactic and have concerns about harming their relationships with others [ 79 ]. On the other hand, Finstas are meant to help with self-presentation by hiding one’s true identity. Ironically, the content posted may be even more representative of the user’s attitudes and activities than the idealized images on one’s public-facing account. These contrasting examples illustrate how self-presentation concerns are complicated.

What further complicates reputation management is that social media content is shared and consumed by a group of people and not just individuals or dyads. Thus, self-presentation is not only controlled by the individual, but by others who might post pictures and/or tag that individual. Even when friends/followers do not directly post about the user, their actions can reflect on the user just by virtue of being connected with them. The issues of co-owned data and how to negotiate disclosure rules are a key area of privacy research on the rise. We refer you to Chap. 6 , which goes in-depth on this topic.

3.4 Access to Oneself

A final privacy challenge many social media users encounter is controlling accessibility others have to them. Some social media platforms automatically display when someone is online, which may invite interaction whether users want to be accessible or not. Controlling access to oneself is not as straightforward as limiting or blocking certain people’s access. For instance, studies have also shown that social pressures influence individuals to accept friend requests from “weak ties” as well as true friends [ 53 , 80 ]. As a result, the social dynamics on social media are becoming more complex, creating social anxiety and drama for many social media users [ 52 , 53 , 80 ]. Although a user may want to control who can interact with him or her, they may be worried about how using privacy features such as “blocking” other accounts may send the wrong signal to others and hurt their relationships [ 81 ]. In fact, an online social norm called “hyperfriending” [ 82 ] has developed where only 25% of a user’s online connections represent true friendship [ 83 ]. This may undermine the privacy individuals wished they had over who interacts with them on their various accounts. Due to social norms or etiquette, users may feel compelled to interact with others online [ 84 ]. Even if users do not feel like they need to interact, they can sometimes get annoyed or overwhelmed by seeing too much information from others [ 85 ]. Their mental state is being bombarded by an overload of information, and they may feel their attention is being captured.

Many social media sites now include location-sharing features to be able to tell people where they are by checking in to various locations, tag photos or posts, or even share location in real time. Therefore, privacy issues may also arise when sharing one’s location on social media and receiving undesirable attention. Studies point out user concerns about how others may use knowledge of that location to reach out and ask to meet up, or even to physically go find the person [ 86 ]. In fact, research has found that people may not be as concerned about the private nature of disclosing location as they are concerned for disturbing others or being disturbed oneself as a result of location sharing [ 87 ]. This makes sense given that analysis of mobile phone conversations reveals that describing one’s location plays a big role in signaling availability and creating social awareness [ 87 , 88 ].

Some scholars focus on the potential harm that may come because of sharing their location. Tsai et al. surveyed people about perceived risks and found that fear of potential stalkers is one of the biggest barriers to adopting location-sharing services [ 89 ]. Nevertheless, studies have also found that many individuals believe that the benefits of using location sharing outweigh the hypothetical costs. Foursquare users have expressed fears that strangers could use the application to stalk them [ 78 ]. These concerns may explain why users share their location more often with close relationships [ 37 ].

Geotagging is another area of privacy concern for online users. Geotagging is when media (photo, website, QR codes) contain metadata with geographical information. More often the information is longitudinal and latitudinal coordinates, but sometimes even time stamps are attached to photos people post. This poses a threat to individuals that post online without realizing that their photos can reveal sensitive information. For example, one study assessed Craigslist postings and demonstrated how they could extract location and hours a person would likely be home based on a photo the individual listed [ 90 ]. The study even pinpointed the exact home address of a celebrity TV host based on their posted Twitter photos. Researchers point out how many users are unaware that their physical safety is at risk when they post photos of themselves or indicate they are on vacation [ 22 , 90 , 91 ]. Doing so may make them easy targets for robbers or stalkers to know when and where to find them.

3.5 Privacy Paradox

While researchers have investigated these various privacy attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors, the privacy paradox (where behavior does not match with stated privacy concerns) has been especially salient on social media [ 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 ]. As a result, much research focuses on understanding the decision-making process behind self-disclosure [ 98 ]. Scholars that view disclosure as a result of weighing the costs and the benefits of disclosing information use the term “privacy calculus” to characterize this process [ 99 ]. Other research draws on the theory of bounded rationality to explain how people’s actions are not fully rational [ 100 ]. They are often guided by heuristic cues which do not necessarily lead them to make the best privacy decisions [ 101 ]. Indeed, a large body of literature has tried to dispel or explain the privacy paradox [ 94 , 102 , 103 ].

4 Reconceptualizing Social Media Privacy as Boundary Regulation

By reconceptualizing privacy in social media as a boundary regulation , we can see that the seeming paradox in privacy is actually a balance between being too open or disclosing too much and being too inaccessible or disclosing too little. The latter can result in social isolation which is privacy regulation gone wrong.

In the context of social media, there are five different types of privacy boundaries that should be considered.

People use various methods of coping with privacy violations , many not tied to disclosing less information.

Drawing from Altman’s theories of privacy in the offline world (see Chap. 2 ), Palen and Dourish describe how, just like in the real world, social media privacy is a boundary regulation process along various dimensions besides just disclosure [ 104 ]. Privacy can also involve regulating interactional boundaries with friends or followers online and the level of accessibility one desires to those people. For example, if a Facebook user wants to limit the people that can post on their wall, they can exclude certain people. Research has identified other threats to interpersonal boundary regulation that arise out of the unique nature of social media [ 42 ]. First, as mentioned previously, the threat to spatial boundaries occurs because our audiences are obscured so that we no longer have a good sense of whom we may be interacting with. Second, temporal boundaries are blurred because any interaction may now occur asynchronously at some time in the future due to the virtual persistence of data. Third, multiple interpersonal spaces are merging and overlapping in a way that has caused a “steady erosion of clearly situated action” [ 5 ]. Since each space may have different and, at times, mutually exclusive behavioral requirements, acting accordingly within those spaces has become more of a challenge to manage context collapses [ 42 ]. Along with these problems, a major interpersonal boundary regulation challenge is that social media environments often take control of boundary regulation away from the end users. For instance, Facebook’s popular “Timeline” automatically (based on an obscure algorithm) broadcasts an individual’s content and interactions to all of his or her friends [ 41 ]. Thus, Facebook users struggle to keep up to date on how to manage interactions within these spaces as Facebook, not the end user, controls what is shared with whom.

4.1 Boundary Regulation on Social Media

One conceptualization of privacy that has become popular in the recent literature is viewing privacy on social media as a form of interpersonal boundary regulation. These scholars have characterized privacy as finding the optimal or appropriate level of privacy rather than the act of withholding self-disclosures. That is, it is just as important to avoid over disclosing as it is to avoid under disclosing. Therefore, disclosure is considered a boundary that must be regulated so that it is not too much or too little. Petronio’s communication privacy management (CPM) theory emphasizes how disclosing information (see Chap. 2 ) is vital for building relationships, creating closeness, and creating intimacy [ 105 ]. Thus, social isolation and loneliness resulting from under disclosure can be outcomes of privacy regulation gone wrong just as much as social crowding can be an issue. Similarly, the framework of contextual integrity explains that context-relative informational norms define privacy expectations and appropriate information flows and so a disclosure in one context (such as your doctor asking you for your personal medical details) may be perfectly appropriate in that context but not in another (such as your employer asking you for your personal medical details) [ 106 ]. Here it is not just about an information disclosure boundary but about a relationship boundary where the appropriate disclosure depends on the relationship between the discloser and the recipient.

Drawing on Altman’s theory of boundary regulation, Wisniewski et al. created a useful taxonomy detailing the various types of privacy boundaries that are relevant for managing one’s privacy on social media [ 107 ]. They identified five distinct privacy boundaries relevant to social media:

Relationship . This involves regulating who is in one’s social network as well as appropriate interactions for each relationship type.

Network . This consists of regulating access to one’s social connections as well as interactions between those connections.

Territorial . This has to do with regulating what content comes in for personal consumption and what is available in interactional spaces.

Disclosure . The literature commonly focuses on this aspect which consists of regulating what personal and co-owned information is disclosed to one’s social network.

Interactional . This applies to regulating potential interaction with those within and outside of one’s social network.

Of these boundary types, Wisniewski et al. emphasize the most important is maintaining relationship boundaries between people. Similarly, Child and Petronio note that “one of the most obvious issues emerging from the impact of social network site use is the challenge of drawing boundary lines that denote where relationships begin and end” [ 108 ]. Making sure that social media facilitates behavior appropriate to each of the user’s relationships is a major challenge.

Each of these interpersonal boundaries can be further classified into regulation of more fine-grained dimensions. In Table 7.1 , we summarize the different ways that each of these five interpersonal boundaries can be regulated on social media.

Next, we describe each of these interpersonal boundaries in more detail.

Self- and Confidant Disclosures

The information disclosure concerns described in the previous “Privacy Challenges” section are the focus of privacy around disclosure boundaries. Posting norms on social media platforms often encourage the disclosure of one’s personal information (e.g., age, sexual orientation, location, personal images) [ 109 , 110 ]. Disclosing such information can leave one open to financial, personal, and professional risks such as identity theft [ 46 , 111 ]. However, there are motivations for disclosing personal information. For example, research suggests that posting behaviors on social media platforms have a significant relationship with a desire for positive self-presentation [ 112 , 113 ]. Privacy management is necessary for balancing the benefits of disclosure and its associated risks. This involves regulating both self-disclosure for information about one’s self and confidant-disclosure boundaries for information that is “co-owned” with others [ 105 ] (e.g., a photograph that includes other people, or information about oneself that is shared with another in confidence).

There are a variety of disclosure boundary regulation mechanisms on social media interfaces. Many platforms offer users the freedom to selectively share various types of information, create personal biographies, share links to their websites, or post their birthday. Self-disclosure can also be maintained through privacy settings such as granular control over who has access to specific posts. The level of information one wishes to disclose could be managed by various privacy settings. Many social media platforms encourage multiparty participation with features such as tagging, subtweeting, or replying to others’ posts. This level of engagement promotes the celebration of shared moments or co-owned information/content. At the same time, it increases possibilities for breaching confidentiality and can create unwanted situations such as posting congratulations to a pregnancy that has not yet been announced to most family members or friends. Some ways that people manage violations of disclosure boundaries are to reactively confront the violator in private or to stop using the platform after the unexpected disclosure [ 114 ].

Relationship Connection and Context

Relationship boundaries have to do with who the user accepts into his or her “friend group” and consequently shapes the nature of online interactions within a person’s social network. Social media platforms have embedded the idea of “friend-based privacy” where information and interactional access is primarily dependent on one’s connections. The structure of one’s network can affect the level of engagement and the types of disclosures made on a platform. Individuals with more open relationship boundaries may have higher instances of weak ties compared to others who may employ stricter rules for including people into their inner circles. For example, studies have found people who engage in “hyper-adding,” namely, adding a significant number of persons to their network which could result in a higher distribution of “weak ties” [ 53 , 82 ].

After users accept friends and make connections, they must manage overlapping contexts such as work, family, or acquaintances. This leads to the types of privacy issues discussed under “Context Collapse” in the previous “Privacy Challenges” section. Research shows that boundary violations are hardly remedied by blocking or unfriending unless in extreme cases [ 115 ]. Furthermore, users rarely organize their friends into groups (and some social media platforms do not offer that functionality) [ 114 ]. People are either unaware of the feature, think it takes too much time, or are concerned that the wrong person would still see their information. As a result, users often feel they have to sacrifice being authentic online to control their privacy.

Network Discovery and Interaction

An individual’s social media network is often public knowledge, and there are advantages and disadvantages of having friends being aware of one’s social connections (aka friends list or followers). Network boundary mechanisms enable people to identify groups of people and manage interactions between the various groups. We highlight two types of network boundaries, namely, network discovery and network intersection boundaries. First, network discovery boundaries are primarily centered around the act of regulating the type of access others have to one’s network connections. Implementing an open approach to network discovery boundaries may create problems that may arise including competition as competitors within the same industry could steal clients by carefully selecting from a publicly facing friend list. Another issue arises when a person’s friend does not have a good reputation and that connection is negatively received by others within that social group. Sometimes the result is positive, for example, when friends or family find they have mutual connections, thus building social capital. Some social media platforms offer the ability to hide friend groups from everyone.

Network intersection boundaries involve the regulation of the interactions among different friend groups within one’s social network. Social media users have expressed the benefits of engaging in discourse online with people who they may not personally know offline [ 116 ]. In contrast, clashes within one’s friend list due to opposing political views or personal stances could create tensions that would make moderating a post difficult. These boundaries could be harder to control and sometimes lead to conflict if one is forced to choose which friends can participate in discussions.

Inward- and Outward-Facing Territories

Territorial boundaries include “places and objects in the environment” to indicate “ownership, possession, and occasional active defense” [ 117 ]. Within social media, there are features that are either inward-facing territories or outward-facing territories. Inward-facing territories are commonly characterized as spaces where users could find updates on their friends and see the content their connections were posting (such as the “news feed” on Facebook or “updates” on LinkedIn). To control their inward-facing territories, individuals could hide posts from specific people, adjust their privacy settings, and use filters to find specific information.

These territories are constantly being updated with photos, videos, and news articles that are personalized and not public facing which contributes to an overall low priority for territorial management [ 114 ]. Most choose to ignore content that is irrelevant to them rather than employing privacy features. In addition, once privacy features are used to hide content from particular friends, users rarely revisit that decision to reconsider including content within that territory from that person.

It is important to note that the key characteristic of outward-facing territory management is the regulation of potentially unsatisfactory interactions rather than a fear of information exposure. One example of an outward-facing territory is Facebook’s wall/timeline, where a person’s friend may contribute to your social media presence. Outward-facing territories fall between a public and private place, which creates more risk of unintended boundary violations. Altman argues that “because of their semipublic quality [outward-facing territories] often have unclear rules regarding their use and are susceptible to encroachment by a variety of users, sometimes inappropriately and sometimes predisposing to social conflict” [ 117 ]. Similar to confidant disclosure described above, connections may post (unwanted) content on a user’s wall that could lead to turbulence if that content is later deleted.

Interactional Disabling and Blocking

Interactional boundaries limit the need for other boundary regulations discussed because a person reduces access to oneself by disabling features [ 114 ]. For example, a user may deactivate Facebook Messenger to avoid receiving messages but reactivate the app when they deem that interaction to be welcomed. In a similar regard, disabling semipublic features of the interface (such as the wall on Facebook) could assist users in having a greater sense of control. This manifestation of interaction withdrawal is typically not directed at reducing interaction with a specific person; rather, it may be motivated by a high desire to control one’s online spaces. As such, disabling features are associated with perceptions of mistrust within one’s network and a desire to limit interruptions [ 115 ]. On the more extreme end, blocking could also be employed to regulate interactional boundaries. Unlike other withdrawal mechanisms such as disabling your wall, picture tagging, or chat, blocking is inherently targeted. The act represents the rejection and revocation of access to oneself from a particular party. Some social media platforms allow users to block other people or pages, meaning that the blocked person may not contact or interact with the user in any form. Generally, blocking a person results from a negative experience such as stalking or being bombarded with unwanted content [ 118 ].

4.2 Coping with Social Media Privacy Violations

Overtime, many social media platforms have implemented new privacy features that attempt to address evolving privacy risks and users’ need for more granular control online. While this effort is commendable, Ellison et al. argue that “privacy behaviors on social networking sites are not limited to privacy settings” [ 41 ]. Thus, social media users still venture outside the realm of privacy settings to achieve appropriate levels of social interactions. Coping mechanisms can be viewed as behaviors utilized to maintain or regain interpersonal boundaries [ 107 ]. Although these coping approaches may often be suboptimal, Wisniewski et al.’s framework of coping strategies for maintaining one’s privacy provides insight into the struggles many social media users face in maintaining these boundaries.

This approach is often defined as the “reduction of intensity of inputs” [ 117 ]. Filtering includes selecting whom one will accept into their online social circle and is often used in the management of relational boundaries. Filtering techniques may include relying on social cues (e.g., viewing the profile picture or examining mutual friends) before confirming the addition of a new connection. Other methods leverage non-privacy-related features that are repurposed to manage interactions based on relation context, for example, creating multiple accounts on the same platform to separate professional connections from personal friends.

The vast amount of information on social media could easily become overwhelming and difficult to consume. Therefore, social media users may opt to ignore posts or skim through information to decide which ones should receive priority for engagement. Ignoring is most common for inward-facing territories such as your “Feed” page. The overreliance on this approach might increase the chances of missing critical moments that connections shared.

Blocking is a more extreme approach to interactional boundary management compared to filtering and ignoring, which contributes to lower levels of reported usage [ 119 ]. As an alternative, users have developed other technology-supported mechanisms that would allow them to avoid unwanted interactions. As an example, Wisniewski et al. describe using pseudonyms on Facebook to make it more difficult to find a user on the platform [ 107 ]. Another method for blocking unwanted interactions is to use the account of a close friend or loved one to enjoy the benefits of the content on the platform without the hassle of expected interactions. Page et al. highlight this type of secondary use for those who avoid social media because of social anxieties, harassment, and other social barriers [ 120 ].

When some users feel they are losing control, they withdraw from social media by doing one of the following: deleting their account, censoring their posts, or avoiding confrontation. As a result, a common technique is limiting or adjusting the information shared (even avoiding posts that may be received negatively) [ 121 ]. Das and Kramer found that “people with more boundaries to regulate censor more; people who exercise more control over their audience censor more content; and, users with more politically and age diverse friends censor less, in general” [ 122 ]. Withdrawal suggests that some users think the risks outweigh the benefits of social media.

Unlike offensive coping mechanisms such as filtering, blocking, or withdrawal, social media users resort to more defensive mechanisms when the intention is to create interactions that may be confrontational. Aggressive behavior is displayed when the goal is to seek revenge or garner attention from specific people or groups. Some users may choose to exploit subliminal references in their posts to indirectly address or offend specific persons (e.g., an ex-partner, coworker, family member).

Compliance is giving in to pressures (external or internal) and adjusting one’s interpersonal boundary preferences for others. Altman describes this as “repeated failures to achieve a balance between achieved and desired levels of privacy” [ 117 ]. Relinquishing one’s interactional privacy needs to accommodate pressures of disclosure, nondisclosure, or friending preferences could result in a perceived loss of control over social interactions.

A healthy strategy for managing social media boundary violations is communicating with the other person involved and finding a resolution. Prior work indicates that most users that compromise do so offline [ 107 ]. These compromises are mostly with closer friends who the user can contact through email, phone call, or messaging. These more private scenarios avoid other people becoming involved online. Also, many compromises are about tagging someone in photos or sharing personal information about another user (i.e., confidant disclosure).

In addition to this coping framework for social media privacy, Stutzman examined the creation of multiple profiles on social media websites, primarily Facebook, as an information regulation mechanism. Through grounded theory, he identified three types of information boundary regulation within this context (pseudonymity, practical obscurity, and transparent separations) and four overarching motives for these mechanisms (privacy, identity, utility, and propriety) [ 71 ]. Lampinen et al. created a framework of strategies for managing private versus public disclosures. It defined three dimensions by which strategies differed: behavioral vs. mental, individual vs. collaborative, and preventative vs. corrective [ 71 , 123 ]. The various coping frameworks conceptualize privacy as a process of interpersonal boundary regulation. However, they do not solve the problem of managing privacy on these platforms. They do attempt to model the complexity of privacy management in a way that better reflects the complex nature of interpersonal relationships rather than as a matter of withholding versus disclosing private information.

5 Addressing Privacy Challenges

Rather than just measuring privacy concerns, researchers and designers should focus on understanding attitudes towards boundary regulation. Validated tools for measuring boundary preservation concern and boundary enhancement expectations are provided in this chapter.

Privacy features need to be designed to account for individual differences in how they are perceived and used. While some feel features like untag, unfriend, and delete are useful, others are worried about how using such features will impact their relationships.

Unaddressed privacy concerns can serve as a barrier to using social media. It is crucial to design for not only functional privacy concerns (e.g., being overloaded by information, guarding from inappropriate data access) but social privacy concerns as well (e.g., unwelcome interactions, pressures surrounding appropriate self-presentation).

This section describes how to better identify privacy concerns by measuring them from a boundary regulation perspective. We also emphasize the importance of individual differences when designing privacy features. Finally, we elaborate on a crucial set of social privacy issues that we feel are a priority to address. While many social media users may feel these types of social pressures to some degree, these problems have pushed some of society’s most vulnerable to complete abandonment of social media despite their desire for social connection. We call on social media designers and researchers to focus on these problems which are a side effect of the technologies we have created.

5.1 Understanding People and Their Privacy Concerns

Understanding social media privacy as a boundary regulation allows us to better conceptualize people’s attitudes and behaviors. It helps us anticipate their concerns and balance between too little or too much privacy. However, many existing tools for measuring privacy come from the information privacy perspective [ 124 , 125 , 126 ] and focus on data collection by organizations, errors, secondary use, or technical control of data. In detailing the various types of privacy boundaries that are relevant for managing one’s privacy on social media, Wisniewski et al. [ 114 ] emphasized that the most important is maintaining relationship boundaries between people.

Page et al. [ 86 , 127 ] similarly found that concerns about damaging relationship boundaries are actually at the root of low-level privacy concerns such as worrying about who sees what, being too accessible, or being bothered or bothering others by sharing too much information. For instance, a typically cited privacy concern such as being worried about a stranger knowing one’s current location turns out to be a privacy concern only if an individual expects that a stranger might violate typical relationship expectations. Their research revealed that many people were unconcerned about strangers knowing their location and explained that no one would care enough to use that information to come find them. They did not expect anyone to violate relationship boundaries and so were privacy unconcerned. On the other hand, those who felt there was a likelihood of someone using their location for nefarious purposes were privacy concerned. Social media enabling a negative change in relationship boundaries and the types of interactions that are now possible (such as strangers now being able to locate me) drives privacy concerns.

In fact, while scholars have used many lower-level privacy concerns such as being worried about sharing information to predict social media usage and adoption, they have met with mixed success leading to the commonly observed privacy paradox. However, research shows that preserving one’s relationship boundaries is at the root of these low-level online privacy concerns (e.g., informational, psychological, interactional, and physical privacy concerns) and is a significant predictor of social media usage [ 86 , 127 ]. In other words, concerns about social media damaging one’s relationships (aka relationship boundary regulation) are what drives privacy concerns.

5.2 Measuring Privacy Concerns

Boundary regulation plays a key role in maintaining the right level of privacy on social media, but how do we evaluate whether a platform is adequately supporting it? A popular scale for testing users’ awareness of secondary access is the Internet Users’ Information Privacy Concerns (IUIPC) scale, which measures their perceptions of collection, control, and awareness of user data [ 125 ]. An important finding is that users “want to know and have control over their information stored in marketers’ databases.” This indicates that social media should be designed such that people know where their data goes. However, throughout this chapter, it is evident that research on social media privacy has found concerns about social privacy more salient. In fact, the focus on relationship boundaries is a key privacy boundary to consider and measure in evaluating privacy concerns. Thus, having a scale to measure relationship boundary regulation would allow researchers and designers to better evaluate social media privacy.

Here we present validated relationship boundary regulation survey items developed by Page et al. which predict adoption and usage for various social media including Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Instagram, and location-sharing social media [ 127 , 128 ]. These survey items can be used to evaluate privacy concerns for use of existing social media platforms, as well as capturing attitudes about new features or platforms. The survey items capture attitudes about one’s ability to regulate relationship boundaries when using a social media platform and are administered with a 7-point Likert scale (−3 = Disagree Completely, −2 = Disagree Mostly, −1 Disagree Slightly, 0 = Neither agree nor disagree, 1 = Agree Slightly, 2 = Agree Mostly, 3 = Agree Completely). These items measure both concerns and positive expectations.

When evaluating a new or existing social media platform, the relationship boundary preservation concern (BPC) items can be used to gauge user’s concerns about harming their relationships. A higher score would indicate that more support for privacy management is needed on a given platform. The relationship boundary enhancement expectation (BEE) items can also be used to evaluate whether users expect that using the platform will improve the user’s relationships. A high score is important to driving adoption and usage – having low concerns alone is not enough to drive usage. Along similar lines, even if users have high concerns, they may be counteracted by a perceived high level of benefits and so users remain frequent users of a platform. For instance, Facebook, one of the most widely used platforms, was shown to both invoke high levels of concern as well as high levels of enhancement expectation [ 127 ]. However, note that high frequency of use does not necessarily mean high levels of engagement (e.g., posting, commenting) or that users do not employ suboptimal workarounds (e.g., being vague in their posts) [ 81 ]. On the other hand, Twitter has a higher level of concerns compared to perceived enhancement and, accordingly, lower levels of usage [ 127 ].

In the validation studies, the set of survey items representing BPC were treated as a scale and factor analysis used to compute a single score. Similarly, the ones representing BEE were used to generate a single factor score to represent that construct. These could be used to evaluate new features or platforms in the lab or after deployment. For instance, after performing tasks on a new feature or platform, the user can answer these questions and the designer can compare the responses between different designs in A/B testing, or to predict usage frequency and adoption intentions (e.g., see [ 127 , 129 ] for detailed examples). Moreover, by correlating BPC or BEE with demographics or other customer segmentations (e.g., age, whether they are new customers, purpose for using the platform), product designers may be able to identify attitudes that are connected with certain segments of their customer base and address it directly.

5.3 Designing Privacy Features