An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Challenges and Opportunities for Research on Same-Sex Relationships

Research on same-sex relationships has informed policy debates and legal decisions that greatly affect American families, yet the data and methods available to scholars studying same-sex relationships have been limited. In this article the authors review current approaches to studying same-sex relationships and significant challenges for this research. After exploring how researchers have dealt with these challenges in prior studies, the authors discuss promising strategies and methods to advance future research on same-sex relationships, with particular attention given to gendered contexts and dyadic research designs, quasi-experimental designs, and a relationship biography approach. Innovation and advances in the study of same-sex relationships will further theoretical and empirical knowledge in family studies more broadly and increase understanding of different-sex as well as same-sex relationships.

One of the most high-stakes debates in the United States today concerns whether and how same-sex relationships influence the health and well-being of individuals, families, and even society. Social scientists have conducted studies that compare same- and different-sex relationships across a range of outcomes (see reviews in Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007 ; Rothblum, 2009 ), and state and federal judiciaries have drawn on this evidence to make critical legal decisions that affect same-sex partners and their children (e.g., American Sociological Association, 2013 ; DeBoer v. Snyder, 2014 ; Hollingsworth v. Perry, 2013 ). Therefore, it is critical that family scholars develop a scientifically driven agenda to advance a coordinated and informed program of research in this area.

Advances in theory and research on marriage and family are inherently shaped by the changing contours of family life over time. For example, during the past decade, increases in the number of people who cohabit outside of marriage have been accompanied by vast improvement in the methods and data used to study cohabiting couples ( Kroeger & Smock, 2014 ). A number of factors point to similarly significant advances in data and research on same-sex relationships in the near future. First, the number of individuals in same-sex unions is significant; recent data from the U.S. Census indicate that about 650,000 same-sex couples reside in the United States, with 114,100 of those couples in legal marriages and another 108,600 in some other form of legally recognized partnership ( Gates, 2013b ). Second, the increasing number of states that legally recognize same-sex marriage (now at 19 states and the District of Columbia, and likely more by the time this article is published), and the U.S. Supreme Court’s reversal of the Defense of Marriage Act in 2013 suggest there will be many more legally married same-sex couples in the years ahead. Third, growing efforts by the federal government to identify same-sex couples in U.S. Census counts and national surveys (e.g., the National Health Interview Survey) and to fund research on sexual minority populations mean that researchers will have new sources of data with which to study same-sex relationships in the future.

We organize this article into three main sections. First, we provide a brief overview of current research and data on same-sex relationships, distinguishing between studies that examine individuals in same-sex relationships and those that examine same-sex couples (i.e., dyads). These two approaches are often conflated, yet they address different kinds of questions. For example, studies of individuals can assess the health benefits of being in a same-sex relationship by comparing individuals in same-sex relationships with individuals in other relationship statuses, whereas a focus on couples allows researchers to examine how same-sex partners compare with different-sex partners in influencing each other’s health. In the second section we consider common methodological challenges encountered in studies of same-sex relationships as well as strategies for addressing these challenges, with particular attention to identifying individuals in same-sex relationships and sample size concerns, addressing gender and sexual identity, recruiting respondents, and choosing comparison groups for studies of same-sex relationships. In the third section we discuss promising strategies for future research on same-sex relationships, with a focus on gendered relational contexts and dyadic research designs, quasi-experimental designs, and a relationship biography approach.

We hope that this article, by drawing on multiple perspectives and methods in the study of same-sex relationships, will advance future research on same-sex unions. Although we discuss details of specific studies, the present article is not intended to be a comprehensive review of research findings on same-sex relationships; our primary focus is on data concerns and methodological strategies. We refer readers to several outstanding reviews of research on same-sex relationships (see, e.g., Kurdek, 2005 ; Moore & Stambolis-Ruhstorfer, 2013 ; Patterson, 2000 ; Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007 ; Rothblum, 2009 ).

Data and Methods: General Approaches

In the face of challenges to research on same-sex relationships, including the past failure of federally supported data collections to include measures that clearly identify same-sex relationships, scholars have been creative in data collection and methodological strategies for research. In most analyses that use probability samples and quantitative methods, social scientists analyze data from individuals in same-sex relationships (e.g., Joyner, Manning, & Bogle, 2013 ), but a number of nonprobability studies (qualitative and quantitative) include data from partners within couples (e.g., Moore, 2008 ; Totenhagen, Butler, & Ridley, 2012 ). Both approaches are essential to advancing our understanding of same-sex relationships.

Research on Individuals

Studies on individuals in same-sex relationships, especially those in which nationally representative data are used, have been essential in evaluating similarities and differences between individuals in same-sex relationships and different-sex relationships. For major data sets that can be used to study individuals in same-sex relationships, readers may turn to several overviews that address sample size and measures that are available to identify those in same-sex relationships (see Black, Gates, Sanders, & Taylor, 2000 ; Carpenter & Gates, 2008 ; Gates & Badgett, 2006 ; Institute of Medicine, 2011 ). These data sets have produced information on the demographic characteristics ( Carpenter & Gates, 2008 ; Gates, 2013b ) and the health and economic well-being of individuals in same-sex relationships ( Badgett, Durso, & Schneebaum, 2013 ; Denney, Gorman, & Barrera, 2013 ; Gonzales & Blewett, 2014 ; Liu, Reczek, & Brown, 2013 ). For example, Wight and colleagues ( Wight, LeBlanc, & Badgett, 2013 ) analyzed data from the California Health Interview Survey and found that being married was associated with lower levels of psychological distress for individuals in same-sex relationships as well as those in different-sex relationships. Given the decades of research showing the many benefits of marriage for men and women in different-sex relationships ( Waite, 1995 ), research on the possible benefits of marriage for individuals in same-sex relationships is an important endeavor. However, in contrast to research on different-sex partnerships, scholars lack longitudinal data from probability samples that enable analysis of the consequences of same-sex relationships for health outcomes over time.

Most probability samples used to study individuals in same-sex relationships have not been designed to assess relationship dynamics or other psychosocial variables (e.g., social support, stress) that influence relationships; thus, these data sets do not include measures that are most central to the study of close relationships, and they do not include measures specific to same-sex couples (e.g., minority stressors, legal policies) that may help explain any group differences that emerge. As a result, most qualitative and quantitative studies addressing questions about same-sex relationship dynamics have relied on smaller, nonprobability samples. Although these studies are limited in generalizability, a number of findings have been replicated across data sets (including longitudinal and cross-sectional qualitative and quantitative designs). For example, studies consistently indicate that same-sex partners share household labor more equally than do different-sex partners and that individuals in same- and different-sex relationships report similar levels of relationship satisfaction and conflict (see reviews in Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007 ; Peplau, Fingerhut, & Beals, 2004 ). One nationally representative longitudinal data set, How Couples Meet and Stay Together (HCMST), includes a question about relationship quality, and is unique in that it oversamples Americans in same-sex couples ( Rosenfeld, Thomas, & Falcon, 2011 & 2014 ). The HCMST data make it possible to address questions about relationship stability over time, finding, for example, that same-sex and different-sex couples have similar break-up rates once marital status is taken into account ( Rosenfeld 2014 ).

Research on Same-Sex Couples

Data sets that include information from both partners in a relationship (i.e., dyadic data) allow researchers to look within relationships to compare partners’ behaviors, reports, and perceptions across a variety of outcomes. Therefore, dyadic data have been used to advance our understanding of same-sex partner dynamics. Researchers have analyzed dyadic data from same-sex partners using diverse methods, including surveys ( Rothblum, Balsam, & Solomon, 2011a ), in-depth interviews ( Reczek & Umberson, 2012 ), ethnographies ( Moore, 2008 ), and narrative analysis ( Rothblum, Balsam, & Solomon, 2011b ). A few nonprobability samples that include dyadic data have also incorporated a longitudinal design (e.g., Kurdek, 2006 ; Solomon, Rothblum, & Balsam, 2004 ).

In some dyadic studies data have been collected from both partners separately, focusing on points of overlap and differences between partners’ accounts, studying such issues as the symbolic meaning of legal unions for same-sex couples ( Reczek, Elliott, & Umberson, 2009 ; Rothblum et al., 2011b ), parenting experiences ( Goldberg, Kinkler, Richardson, & Downing, 2011 ), intimacy dynamics ( Umberson, Thomeer, & Lodge, in press ), interracial relationship dynamics ( Steinbugler, 2010 ), partners’ interactions around health behavior ( Reczek & Umberson, 2012 ), and relationship satisfaction and closeness ( Totenhagen et al., 2012 ). In contrast, other studies have collected data from partners simultaneously, through joint interviews, experiments, or ethnographic observations, focusing on interactions between partners or partners’ collective responses. For example, researchers have used observational methods to provide unique insights into same-sex couples’ conflict styles ( Gottman, 1993 ), division of household labor ( Moore, 2008 ), and coparenting interactions ( Farr & Patterson, 2013 ).

Challenges and Strategies for Studying Same-Sex Relationships

Although current data are characterized by several limitations, this is no reason to avoid the study of same-sex relationships. Indeed, it is important to triangulate a range of qualitative and quantitative research designs and sources of data in efforts to identify consistent patterns in same-sex relationships across studies and to draw on innovative strategies that add to our knowledge of same-sex relationships. In the sections that follow we point to some specific challenges to, advances in, and strategies for research on same-sex relationships.

Identifying Individuals in Same-Sex Relationships

Researchers must accurately identify people who are in same-sex relationships if they are to produce valid results and/or allow comparison of results across studies, both of which are necessary to inform sound public policy ( Bates & DeMaio, 2013 ; DiBennardo & Gates, 2014 ). In most nonprobability studies researchers have relied on volunteer samples and respondents’ self-identification as gay or lesbian. Such samples are more likely to include individuals who are open about their sexual orientation and socioeconomically privileged ( Gates & Badgett, 2006 ). Studies that rely on probability samples (e.g., the General Social Survey, the U.S. Census) raise different concerns because these samples were not originally designed to identify people in same-sex relationships and do not directly ask about the sexual orientation or sex of partners. As a result, to identify individuals in same-sex relationships researchers have juxtaposed information about sex of household head, relationship of head of household to other household members, and sex of those household members, a strategy that can result in substantial misidentification of individuals in same- and different-sex relationships (see discussions in Bates & DeMaio, 2013 , and DiBennardo & Gates, 2014 ; for strategies to adjust for misidentification, see Gates & Cook, 2011 ).

A particularly problematic approach for identifying individuals in same-sex relationships is the use of proxy reports . This approach assumes that children (or other proxies) have valid knowledge of other persons’ (e.g., parents’) sexual and relationship histories and is highly likely to produce invalid or biased results ( Perrin, Cohen, & Caren, 2013 ). For example, a recent study ( Regnerus, 2012 ), which purportedly showed adverse effects of same-sex parents on children, has been widely criticized for using retrospective proxy reports from adult children to identify a parent as having ever been involved in a same-sex relationship (for a critique, see Perrin et al., 2013 ). Although the findings from this study have been largely discredited ( Perrin et al., 2013 ), the results have been used as evidence in legal proceedings geared toward forestalling same-sex partners’ efforts to adopt children or legally marry (e.g., American Sociological Association, 2013 ; DeBoer v. Snyder, 2014 ; Hollingsworth v. Perry, 2013 ). This use of social science research highlights the importance of adhering to best practices for research on same-sex relationships (which several U.S.-based surveys are implementing), including directly asking respondents if they have a same-sex partner and allowing for multiple response options for union status (e.g., legal marriage, registered domestic partnership, civil union, cohabitation, and living-apart-together relationships; Bates & DeMaio, 2013 ; Festy, 2008 ).

Sample Size

An additional challenge is the small number of people in same-sex relationships, making it difficult to recruit substantial numbers of respondents and to achieve racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity in samples of persons in same-sex relationships ( Black et al., 2000 ; Carpenter & Gates, 2008 ; for additional strategies, see Cheng & Powell, 2005 ). One strategy to deal with small samples of individuals in same-sex relationships has been to pool data across years or data sets to obtain a sufficient number of cases for analysis (e.g., Denney et al., 2013 ; Liu et al., 2013 ; Wienke & Hill, 2009 ). For example, using pooled data from the National Health Interview Survey, Liu and colleagues (2013) found that socioeconomic status suppressed the health disadvantage of same-sex cohabitors compared with different-sex married adults. Other studies have pooled data across different states to achieve larger and more representative samples, focusing especially on states with higher concentrations of same-sex couples. For example, Blosnich and Bossarte (2009) aggregated 3 years of state-level data from 24 states to compare rates and consequences of intimate partner violence) in same- and different-sex relationships and found that victims of intimate partner violence report poorer health outcomes regardless of sex of perpetrator.

Gender and Sexual Identity

Since the publication of Jessie Bernard’s (1982) classic work on “his” and “her” marriage, social scientists have identified gender as a driving predictor of relationship experiences ( Umberson, Chen, House, Hopkins, & Slaten, 1996 ). Studies of same- and different-sex relationships usually rely on self-reports of sex/gender that allow for one of two choices: male or female. But current scholarship highlights the need to go beyond the male–female binary to take into account transgender and transsexual identities by measuring sex assigned at birth and current sex or gender ( Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, 2014 ; Pfeffer, 2010 ) and to measure both gender identity (i.e., psychological sense of self) and gender presentation (i.e., external expressions, e.g., physical appearance, clothing choices, and deepness of voice; Moore & Stambolis-Ruhstorfer, 2013 ). This approach pushes us to think about how gender identity and presentation might shape or modify relationship experiences of partners within same- and different-sex relationships. For example, gender identity may be more important than sex in driving housework (in)equality between partners in both same- and different-sex relationships. Scholars can further consider how these aspects of gender and sexuality may vary across diverse populations.

Similarly, studies need to include questions about multiple aspects of sexuality (e.g., desires, behavior, identity) in order to capture a fuller range of diversity. For example, this would allow for the examination of differences between people in same-sex relationships who identify as bisexual and those who identify as gay or lesbian; individuals in mixed-orientation marriages (e.g., bisexual men married to heterosexual women) may experience unique difficulties and relationship strategies ( Wolkomir, 2009 ). Failing to consider gender identity and presentation as well as sexual identity and orientation may also cause researchers to misidentify some same-sex relationships and overlook important sources of diversity among same- and different-sex relationships ( Moore & Stambolis-Ruhstorfer, 2013 ). Attention to gender identity and presentation in future research will lead to a more nuanced understanding of gendered dynamics within different- as well as same-sex relationships.

Recruitment Challenges

Recruiting people for studies of same-sex relationships poses several unique challenges beyond typical recruitment concerns. In particular, because of past discrimination, people in same-sex relationships may not trust researchers to present research findings in fair and accurate ways, keep findings confidential and anonymous, or present findings in ways that will not stigmatize same-sex couples and bolster legislation that limits the rights of same-sex partners ( McCormack, 2014 ; Meyer & Wilson, 2009 ). Recruiting both partners in same-sex couples is even more challenging; even if one partner agrees to participate in a study, past experiences of discrimination or not being “out” may lead the other partner to avoid taking part in the study.

Past strategies have included working with community partners (e.g., local lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender advocacy groups) to help researchers establish trust and opportunities for recruitment, in particular when recruiting more targeted samples based on race/ethnicity or socioeconomic status (e.g., Meyer & Wilson, 2009 ; Moore, 2008 ). Researchers also can take advantage of information regarding the geographic distribution of same-sex couples in the United States to collect data in areas with higher concentrations of same-sex couples and racial/ethnic and socioeconomic diversity ( Black et al., 2000 ; Gates, 2010 ). Online recruitment may also facilitate study participation; greater anonymity and ease of participation with online surveys compared to face-to-face data collection may increase the probability that individuals in same-sex unions and same-sex couples will participate in studies ( Meyer & Wilson, 2009 ; Riggle, Rostosky, & Reedy, 2005 ).

Comparison Group Challenges

Decisions about the definition and composition of comparison groups in studies that compare same-sex relationships to different-sex relationships are critical because same-sex couples are demographically distinct from different-sex couples; individuals in same-sex couples are younger, more educated, more likely to be employed, less likely to have children, and slightly more likely to be female than individuals in different-sex couples ( Gates, 2013b ). For example, researchers may erroneously conclude that relationship dynamics differ for same- and different-sex couples when it is in fact parental status differences between same- and different-sex couples that shape relationship dynamics. Three specific comparison group considerations that create unique challenges—and opportunities—for research on same-sex relationships include (a) a shifting legal landscape, (b) parental status, and (c) unpartnered individuals.

Shifting legal landscape

As legal options have expanded for same-sex couples, more studies have compared people in same-sex marriages and civil unions (or registered domestic partnerships) with people in different-sex married partnerships (e.g., Solomon et al., 2004 ). Yet because legal options vary across states and over time, the same statuses are not available to all same-sex couples. This shifting legal landscape introduces significant challenges, in particular for scholars who attempt to compare same-sex couples with different-sex couples, because most same-sex couples have not married (or even had the option of marrying), whereas most different-sex couples have had ample opportunity to marry.

One strategy for addressing this complexity is to collect data in states that legally acknowledge same-sex partnerships. For example, Rothblum and colleagues ( Rothblum et al., 2011a ; Solomon et al., 2004 ) contacted all couples who entered civil unions in Vermont in 2000–2001, and same-sex couples who agreed to participate then nominated their siblings in either different-sex marriages or noncivil union same-sex relationships for participation in the study. This design, which could be adapted for qualitative or quantitative studies, allowed the researchers to compare three types of couples and address potentially confounding variables (e.g., cohort, socioeconomic status, social networks) by matching same-sex couples in civil unions with network members who were similar on these background variables. Gates and Badgett (2006) argued that future research comparing different legal statuses and legal contexts across states will help us better understand what is potentially unique about marriage (e.g., whether there are health benefits associated with same-sex marriage compared to same-sex cohabitation).

A related challenge is that same-sex couples in legal unions may have cohabited for many years but been in a legal union for a short time because legal union status became available only recently. This limits investigation into the implications of same-sex marriage given that marriage is conflated with relationship duration. One strategy for dealing with this is to match same- and different-sex couples in the same legal status (e.g., marriage) on total relationship duration rather than the amount of time in their current status (e.g., cohabiting, married, or other legal status; Umberson et al., in press ). An additional complication is that historical changes in legal options for persons in same-sex relationships contribute to different relationship histories across successive birth cohorts, an issue we address later, in our discussion of relationship biography and directions for future research. Future studies might also consider whether access to legal marriage influences the stability and duration of same-sex relationships, perhaps using quasi-experimental methods (also discussed below).

Parental status and kinship systems

Individuals in same-sex relationships are nested within larger kinship systems, in particular those that include children and parents, and family dynamics may diverge from patterns found for individuals in different-sex relationships ( Ocobock, 2013 ; Patterson, 2000 ; Reczek, 2014 ). For example, some studies suggest that, compared with individuals in different-sex relationships, those in same-sex relationships experience more strain and less contact with their families of origin ( Rothblum, 2009 ). Marriage holds great symbolic significance that may alter how others, including family members, view and interact with individuals in same-sex unions ( Badgett, 2009 ). Past research shows that individuals in different-sex marriages are more involved with their family of origin than are those in different-sex cohabiting unions. Future research should further explore how the transition from cohabitation to marriage alters relationships with other family members (including relationships with families of origin) for those in same-sex unions ( Ocobock, 2013 ).

Although a full discussion of data and methodological issues concerning larger kinship systems is beyond the scope of this article (see Ocobock, 2013 ; Patterson, 2000 ), we focus on one aspect of kinship—parental status—to demonstrate some important comparison group considerations. Parental status varies for same- and different-sex couples and can confound differences between these two groups as well as within groups of same-sex couples (e.g., comparing men with men to women with women). Moreover, because having children contributes to relationship stability for different-sex couples, parental status differences between same- and different-sex couples could contribute to differences in relationship stability ( Joyner et al., 2013 ). Same-sex couples are less likely than different-sex couples to be raising children, although this distinction is diminishing, albeit modestly ( Gates, 2013b ). In 2010, about 19% of same-sex couples had children under age 18 in the home, compared with about 43% of different-sex couples ( Gates, 2013b ). Same-sex partners living with children are also more likely to be female than male and tend to be more economically disadvantaged and to be from racial minority groups than same-sex couples without children ( Gates, 2013a ). Pathways to parenthood are diverse among same-sex couples (e.g., surrogacy, adoption, biological child of one partner from previous relationship), and these pathways differ by age and cohort, gender, race, and socioeconomic status, all factors that may influence parenting experiences ( Brewster, Tillman, & Jokinen-Gordon, 2014 ; Gates & Badgett, 2006 ; Patterson & Tornello, 2010 ). For example, most gay fathers over age 50 had their children within the context of heterosexual marriage, whereas most gay fathers under age 50 became fathers through foster care or adoption ( Patterson & Tornello, 2010 ). A history of different-sex marriage and divorce may influence current relationship dynamics for individuals in same-sex unions.

One strategy for addressing parental status is to match same- and different-sex comparison groups on parental status so that parents are compared with parents and nonparents are compared with nonparents (e.g., Kurdek, 2004 ). This strategy has the advantage of reducing uncontrolled-variable bias owing to parental status (for quantitative studies) and yields unique insights into the experiences of same- and different-sex parents and/or nonparents (for qualitative and quantitative studies). A second strategy for quantitative researchers is to consider parental status as potentially confounding or moderating the effects of union status on selected outcomes. For example, Denney and colleagues (2013) found that parental status is an important moderator in understanding health disparities between women in same-sex and different-sex relationships, in that having children was associated with poorer health for women in same-sex relationships than for women in different-sex relationships.

We further recommend that social scientists understand—and embrace—the diverse ways that parental status varies across union types. It is impossible to fully eliminate uncontrolled-variable bias, and we know that same-sex partners who are parents differ in other important ways from different-sex partners, in particular in terms of sociodemographic characteristics. Moreover, many same-sex partners did not have the option of becoming parents because of barriers to adoption as well as a lack of access to or the prohibitive cost of reproductive technologies, and this unique history shapes their relationship experiences ( Brewster et al., 2014 ). In fact, attempting to “control away” the experience of parental status may mask differences in the lived experiences of same- and different-sex partners. Future research should take into account cohort differences in pathways to (and probability of) parenthood for same-sex partners, in particular in connection with intimate relationship experiences (also see Biblarz & Savci, 2010 ; Brewster et al., 2014 ; Goldberg, Smith, & Kashy, 2010 ; Patterson & Riskind, 2010 ). Researchers could also compare parenthood and relationship experiences in geographic regions that differ on attitudes toward same-sex relationships and families.

Unpartnered individuals

Very few studies have compared individuals in same-sex relationships with their unpartnered counterparts, that is, single men and women with similar attractions, behaviors, and identities. Yet the comparison of partnered to unpartnered persons has led to some of the most fundamental findings about different-sex relationships, showing, for example, that married and cohabiting different-sex partners are wealthier, healthier, and live longer than the unmarried ( Waite, 1995 ). Recent quantitative studies that have considered the unpartnered as a comparison group have found that those in same-sex relationships report better health than those who are widowed, divorced, or never married ( Denney et al., 2013 ; Liu et al., 2013 ). Unfortunately, owing to a lack of information on sexual identity/orientation in most available probability data, individuals in same- and different-sex relationships have been compared with unpartnered persons regardless of the unpartnered person’s sexual orientation or relationship history. Furthermore, studies that focus on sexual orientation and health seldom consider whether such associations differ for the unpartnered versus partnered. Given the substantial evidence that close social ties are central to health and quality of life ( Umberson & Montez, 2010 ), and the relative absence of research comparing individuals in same-sex partnerships to their unpartnered counterparts, research designs that compare those in same-sex relationships to the unpartnered will provide many opportunities for future research. Data collections that focus on individuals who transition between an unpartnered status to a same-sex relationship may be particularly fruitful. For example, given different levels of social recognition and stress exposure, researchers may find that relationship formation (and dissolution) affects individuals from same- and different-sex relationships in different ways.

Future Directions for Research on Same-Sex Relationships

We now turn to three strategies that may help catalyze current theoretical and analytical energy and innovation in research on same-sex relationships: (a) gendered relational contexts and dyadic data analysis, (b) quasi-experimental designs, and (c) the relationship biography approach.

Gendered Relational Contexts and Dyadic Data Analysis

Gender almost certainly plays an important role in shaping relationship dynamics for same-sex couples, but gender is often conflated with gendered relational contexts in studies that compare same- and different-sex couples. For example, women with men may experience their relationships very differently from women with women, and these different experiences may reflect the respondent’s own gender (typically viewed in terms of a gender binary) and/or the gendered context of their relationship (i.e., being a woman in relation to a woman or a woman in relation to a man). A gender-as-relational perspective ( C. West & Zimmerman, 2009 ) suggests a shift from the focus on gender to a focus on gendered relational contexts that differentiates (at least) four groups for comparison in qualitative and quantitative research: (a) men in relationships with men, (b) men in relationships with women, (c) women in relationships with women, and (d) women in relationships with men (see also Goldberg, 2013 ; Umberson, Thomeer, & Lodge, in press ). Indeed, some scholars argue that unbiased gender effects in quantitative studies of relationships cannot be estimated unless researchers include men and women in different- and same-sex couples so that effects for the four aforementioned groups can be estimated ( T. V. West, Popp, & Kenny, 2008 ). Similarly, others emphasize same-sex couples as an important counterfactual to different-sex couples in broadening our understanding of gender and relationships ( Carpenter & Gates, 2008 ; Joyner et al., 2013 ; Moore, 2008 ). For example, recent qualitative research has shown that although gender drives differences in the way individuals view emotional intimacy (with women desiring more permeable boundaries between partners in both same- and different-sex contexts), gendered relational contexts drive the types of emotion work that individuals do to promote intimacy in their relationships (with women with men and men with men doing more emotion work to sustain boundaries between partners; Umberson et al., in press ). A gender-as-relational perspective also draws on intersectionality research ( Collins, 1999 ) to emphasize that gendered interactions reflect more than the gender of each partner; instead, gendered experiences vary depending on other aspects of social location (e.g., the experience of gender may depend on gender identity).

Dyadic data analysis

Although quite a few nonprobability samples (qualitative and quantitative) include data from both partners in relationships, many of these studies have analyzed individuals rather than adopting methods that are designed to analyze dyadic data (for quantitative exceptions, see Clausell & Roisman, 2009 ; Parsons, Starks, Gamarel, & Grov, 2012 ; Totenhagen et al., 2012 ; for qualitative exceptions, see Moore, 2008 ; Reczek & Umberson, 2012 ; Umberson et al, in press ). Yet leading family scholars call for more research that analyzes dyadic-/couple-level data ( Carr & Springer, 2010 ). Dyadic data and methods provide a promising strategy for studying same- and different-sex couples across gendered relational contexts and for further considering how gender identity and presentation matter across and within these contexts. We now touch on some unique elements of dyadic data analysis for quantitative studies of same-sex couples, but we refer readers elsewhere for comprehensive guides to analyzing quantitative dyadic data, both in general ( Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006 ) and specifically for same-sex couples ( Smith, Sayer, & Goldberg, 2013 ), and for analyzing qualitative dyadic data ( Eisikovits & Koren, 2010 ).

Many approaches to analyzing dyadic data require that members of a dyad be distinguishable from each other ( Kenny et al., 2006 ). Studies that examine gender effects in different-sex couples can distinguish dyad members on the basis of sex of partner, but sex of partner cannot be used to distinguish between members of same-sex dyads. To estimate gender effects in multilevel models comparing same- and different-sex couples, researchers can use the factorial method developed by T. V. West and colleagues (2008) . This approach calls for the inclusion of three gender effects in a given model: (a) gender of respondent, (b) gender of partner, and (c) the interaction between gender of respondent and gender of partner. Goldberg and colleagues (2010) used this method to illustrate gendered dynamics of perceived parenting skills and relationship quality across same- and different-sex couples before and after adoption and found that both same- and different-sex parents experience a decline in relationship quality during the first years of parenting but that women experience steeper declines in love across relationship types.

Dyadic diary data

Dyadic diary methods may provide particular utility in advancing our understanding of gendered relational contexts. These methods involve the collection of data from both partners in a dyad, typically via short daily questionnaires, over a period of days or weeks ( Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013 ). This approach is ideal for examining relationship dynamics that unfold over short periods of time (e.g., the effect of daily stress levels on relationship conflict) and has been used extensively in the study of different-sex couples, in particular to examine gender differences in relationship experiences and consequences. Totenhagen et al. (2012) also used diary data to study men and women in same-sex couples and found that daily stress was significantly and negatively correlated with relationship closeness, relationship satisfaction, and sexual satisfaction in similar ways for men and women. Diary data collected from both partners in same- and different-sex contexts would make it possible for future studies to conduct longitudinal analyses of daily fluctuations in reciprocal relationship dynamics and outcomes as well as to consider whether and how these processes vary by gendered relationship context and are potentially moderated by gender identity and gender presentation.

Quasi-Experimental Designs

Quasi-experimental designs that test the effects of social policies on individuals and couples in same-sex relationships provide another promising research strategy. These designs provide a way to address questions of causal inference by looking at data across place (i.e., across state and national contexts) and over time—in particular, before and after the implementation of exclusionary (e.g., same-sex marriage bans) or inclusionary (e.g., legalization of same-sex marriage) policies ( Hatzenbuehler et al., 2012 ; Hatzenbuehler, Keyes, & Hasin, 2009 ; Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, Keyes, & Hasin, 2010 ; see Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002 , regarding quasi-experimental methods). This approach turns the methodological challenge of a constantly changing legal landscape into an exciting opportunity to consider how social policies influence relationships and how this influence may vary across age cohorts. For example, researchers might test the effects of policy implementation on relationship quality or marriage formation across age cohorts.

Quasi-experimental designs have not yet been applied to the study of same-sex relationship outcomes, but a number of recent studies point to the potential for innovation. Hatzenbuehler has been at the forefront of research using quasi-experimental designs to consider how same-sex marriage laws influence health care expenditures for sexual minority men ( Hatzenbuehler et al., 2012 ) and psychopathology in sexual minority populations ( Hatzenbuehler et al., 2010 ). For example, he found that the effect of marriage policy change on health care use and costs was similar for gay and bisexual men who were unpartnered and those who were in same-sex relationships ( Hatzenbuehler et al., 2012 ). He and his colleagues have noted that the challenges of a quasi-experimental approach include dealing with the constraints of measures available in existing data sets before and after policy implementation and the difficulty (or impossibility) of knowing when particular policies will be implemented, as well as limitations associated with lack of random assignment and changes other than policy shifts that occur during the same time period and may influence results ( Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009 , 2010 , 2012 ). One strategy for addressing the latter challenge is to test the plausibility of alternative explanations; for example, Hatzenbuehler et al. (2012) examined whether other co-occurring changes could explain their findings (e.g., changes in health care use among all Massachusetts residents). Future studies could also follow up on prior qualitative and quantitative data collections to compare individual and relationship experiences of interest (e.g., relationship satisfaction) before and after policy changes (e.g., repeal of the Defense of Marriage Act).

Quasi-experimental designs are also useful for identifying mechanisms (e.g., stress) that explain different outcomes across and within couples. Sexual minority populations face higher rates of stress, stigma, and discrimination both at the individual and institutional level, as described by Meyer’s (2003) minority stress model. Measures that tap into minority stress and discrimination could be incorporated in future studies as a way to better understand same-sex relationship dynamics and outcomes for individuals and dyads (see LeBlanc, Frost, & White, 2015 ). For example, Frost and Meyer (2009) found that higher levels of internalized homophobia were associated with worse relationship quality for lesbian, gay, and bisexual men and women. These associations could be evaluated before and after key policy changes. Moreover, this approach could use dyadic data to assess the effects of policy change on couples and individuals in same- and different-sex relationships ( LeBlanc et al., 2015 ).

Relationship Biography Approach

In closing, we suggest that a relationship biography approach —that is, focusing on temporal changes in relationship statuses and other components of relationship histories, such as relationship durations—be used as an organizing framework to drive future qualitative and quantitative research and studies of individuals as well as partner dyads. The life course perspective ( Elder, Johnson, & Crosnoe, 2003 ) has been used to guide a relationship biography approach in studies of different-sex couples (e.g., Hughes & Waite, 2009 ) and could offer great utility in addressing key challenges of research on same-sex couples ( Institute of Medicine, 2011 ). In particular, a relationship biography approach could take into account the constantly changing legal landscape and relationship status options for same-sex couples, the varying amounts of time it would be possible to spend in those statuses (both over time and across geographic areas/states/nations), and cohort differences. A biographical approach would address these challenges by considering three things: (a) multiple relationship statuses over the life course; (b) duration of time in each relationship status; and (c) history of transitions into and out of relationships, as well as timing of those transitions in the life course. We further suggest that change in relationship quality over time be considered as a component of relationship biography. The biographical frame can be used with different theoretical approaches, is multidisciplinary in scope, urges multiple and intersecting research methods, and emphasizes diversity in life course experiences.

In considering an individual’s relationship biography over the life course, information on the legal status (e.g., civil union, registered domestic partnership) of each of his or her unions could be collected. Although the available evidence is mixed, some studies suggest that same-sex unions dissolve more quickly than do different-sex unions ( Lau, 2012 ). However, we do not yet have extensive biographical evidence about the duration of same-sex unions in the United States, or how access to marriage might influence relationship duration. By taking into account relationship duration and transitions out of significant relationships, future research could also address the predictors, experiences, and consequences of relationship dissolution through death or breakup, experiences that have not been adequately explored in past research on same-sex couples ( Gates & Badgett, 2006 ; Rothblum, 2009 ). A relationship biography approach could also take into account gender identity and sexual identity transitions. Prior qualitative research suggests that one partner’s gender transition has important implications for relationship dynamics (e.g., the division of labor) as well as relationship formation and dissolution ( Moore & Stambolis-Ruhstorfer, 2013 ; Pfeffer, 2010 ).

Relationship biography is fundamentally shaped by birth cohort, race/ethnicity, gender and transgender identity, social class, and former as well as current sexual orientation. Older cohorts of people in same-sex relationships, who formed their relationships in an era of significantly greater discrimination and no legal recognition for same-sex couples, may differ dramatically from younger cohorts ( LeBlanc et al., 2015 ; Patterson & Tornello, 2010 ). Unique historical backdrops result in different relationship histories (e.g., number of years cohabiting prior to marriage, shifts in sexual orientation, risk for HIV, and effects on relationship dynamics), parenting experiences, and, potentially, relationship quality for younger and older cohorts. Thus, age, period, and cohort variation are important to consider in future studies of same-sex relationships ( Gotta et al., 2011 ).

A biographical approach should incorporate information on relationship quality. Studies of different-sex couples show that relationship quality is linked to relationship duration and transitions, as well as mental and physical health ( Choi & Marks, 2013 ; Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, & Needham, 2006 ). Currently, most national data sets that include information on relationship dynamics (e.g., the National Survey of Families and Households, the Health and Retirement Survey) do not include sufficient numbers of same-sex couples to allow valid statistical analysis. Incorporating relationship quality measures into representative data sets will contribute to a better understanding of the predictors and consequences of relationship quality for same-sex partnerships, the links between relationship quality and relationship duration and transitions, and relationship effects on psychological and physical well-being. A relationship biography can be obtained retrospectively in cross-sectional data collections or assessed longitudinally as relationships evolve over time. A relationship biography approach would benefit from including an unpartnered comparison group, taking into account previous relationship statuses. A biographical approach might also be used in future research to consider the impact of structural changes (in addition to personal or relationship changes), such as change in public policies or moving to/from a geographic area with laws/policies that support same-sex relationships.

The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health, see www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth ) provides a promising opportunity for studying same-sex relationship biographies in the future. This nationally representative study of adolescents (beginning in 1994) has followed respondents into young adulthood; respondents were, on average, age 28 in the most recent survey. Add Health includes measures of same-sex attraction, sexual identity, and histories of same- and different-sex relationships, allowing for detailed analysis of the lives of young adults. A biographical approach directs attention to relationship formation throughout the life course, and Add Health data may be useful for studies of relationship formation. For example, Ueno (2010) used Add Health data to incorporate the idea of life course transitions into a study of shifts in sexual orientation among adolescents over time and found that moving from different-sex relationships to same-sex relationships was correlated with worse mental health than continually dating same-sex partners. A focus on relationship transitions between same- and different-sex relationships over the life course builds on theoretical and empirical work on the fluidity of sexual attraction ( Diamond, 2008 ; Savin-Williams, Joyner, & Rieger, 2012 ). Bisexual patterns of sexual attraction and behavior (which are more common than exclusive same-sex sexuality) and transitions between same- and different-sex unions and the timing of those transitions are important, but understudied, research topics ( Biblarz & Savci, 2010 ) that could be addressed through a relationship biography lens. For example, future studies could consider the ages at which these transitions are most likely to occur, duration of same- and different-sex unions, relationship quality experiences, and effects on individual well-being. Men and women may differ in these relationship experiences; women seem to be more situationally dependent and fluid in their sexuality than are men ( Diamond, 2008 ; Savin-Williams et al., 2012 ).

Researchers have also used Add Health data to study same-sex romantic attraction and substance use ( Russell, Driscoll, & Truong, 2002 ), same-sex dating and mental health ( Ueno, 2010 ), and same-sex intimate partner violence ( Russell, Franz, & Driscoll, 2001 ). As respondents age, the Add Health project will become even more valuable to a relationship biography approach. For example, Meier and colleagues ( Meier, Hull, & Ortyl, 2009 ) compared relationship values of heterosexual youth with those of sexual minority youth; follow-up studies could assess whether these differences in values influence relationships throughout adulthood. Data for studying relationship biographies of older cohorts of same-sex couples are sorely lacking at the national level. Investigators certainly must continue to push for funding to include same-sex relationships in new and ongoing data collections. Scholars who have collected data from individuals in same-sex relationships in the past should also consider returning to their original respondents for longitudinal follow-up, as well as follow-up with respondents’ partners (e.g., Rothblum et al., 2011a ).

Research on same-sex relationships is in a period of intense discovery and enlightenment, and advances in the study of these relationships are sure to further our theoretical and empirical knowledge in family studies more broadly. Because of the diversity of same-sex couples and the increasing political and legal significance of who is in a same-sex relationship or family, it is essential to advance research that reflects professional and ethical standards as well as the diversity of same-sex couples ( Perrin, Cohen, & Caren, 2013 ). Decades of federally funded research have enriched the available data on different-sex couples, yet current longitudinal data on same-sex couples are comparable to those gained through research on different-sex couples 30 or more years ago. Investment in future data collections will be essential to advancing knowledge on same-sex couples. Although there is much that we can learn from data collections and methods used to study different-sex couples, we should not simply superimpose those procedures onto the study of same-sex couples. Indeed, as we have discussed, some research questions, measures, and sample composition issues are unique to the study of same-sex relationships and require novel approaches.

Most people yearn for and value an intimate relationship and, once established, a cohabiting, marital, or romantic union becomes a defining feature of their lives. Relationships inevitably go through ups and downs. At some points, partners impose stress on each other, and at other times they provide invaluable emotional support. Over the life course, relationships are formed, sustained, and inevitably ended through breakup or death, with profound effects on individuals and families. Family scholars must design studies that address same-sex partner dating and relationship formation as well as relationship losses and transitions throughout life, with all the vicissitudes therein. In this article we have identified contemporary challenges to research on same-sex relationships and suggested strategies for beginning to address those challenges in order to capture the fullness of lives as they are lived across diverse communities. We hope these strategies will inspire scholars to move the field forward in new and innovative ways.

Acknowledgments

We thank Justin Denney, Jennifer Glass, Mark Hatzenbuehler, Kara Joyner, Wendy Manning, Corinne Reczek, and Esther Rothblum for their helpful comments on this article. This research was supported, in part, by an Investigator in Health Policy Research Award to Debra Umberson from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; Grant R21 AG044585, awarded to Debra Umberson in the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin by the National Institute on Aging; Grant 5 R24 HD042849, awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; and Grant F32 HD072616, awarded to Rhiannon A. Kroeger in the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

- American Sociological Association. Brief of amicus curiae American Sociological Association in support of respondent Kristin M. Perry and respondent Edith Schlain Windsor. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. Retrieved from www.asanet.org/documents/ASA/pdfs/12144_307_Amicus_%20(C_%20Gottlieb)_ASA_Same-Sex_Marriage.pdf . [ Google Scholar ]

- Badgett MVL. When gay people get married. New York: New York University Press; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Badgett MVL, Durso LE, Schneebaum A. New patterns of poverty in the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bates N, DeMaio TJ. Measuring same-sex relationships. Contexts. 2013; 12 :66–69. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernard J. The future of marriage. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1982. [ Google Scholar ]

- Biblarz TJ, Savci E. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010; 72 :480–497. [ Google Scholar ]

- Black D, Gates G, Sanders S, Taylor L. Demographics of the gay and lesbian population in the United States: Evidence from available systematic data sources. Demography. 2000; 37 :139–154. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Blosnich JR, Bossarte RM. Comparisons of intimate partner violence among partners in same-sex and opposite-sex relationships in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2009; 99 :2182–2184. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bolger N, Laurenceau J. Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brewster KL, Tillman KH, Jokinen-Gordon H. Demographic characteristics of lesbian parents in the United States. Population Research and Policy Review. 2014; 33 :503–526. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carpenter C, Gates GJ. Gay and lesbian partnership: Evidence from California. Demography. 2008; 45 :573–590. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carr D, Springer KW. Advances in families and health research in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010; 72 :743–761. [ Google Scholar ]

- Center of Excellence for Transgender Health. Recommendations for inclusive data collection of trans people in HIV prevention, care, and services. 2014 Retrieved from http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/trans?page=lib-data-collection .

- Cheng S, Powell B. Small samples, big challenges: Studying atypical family forms. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005; 67 :926–935. [ Google Scholar ]

- Choi H, Marks NF. Marital quality, socioeconomic status, and physical health. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2013; 75 :903–919. [ Google Scholar ]

- Clausell E, Roisman GI. Outness, Big Five personality traits, and same-sex relationship quality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2009; 26 :211–226. [ Google Scholar ]

- Collins PH. Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. New York: Routledge; 1999. [ Google Scholar ]

- DeBoer v. Snyder , 973 F. Supp. 2d 757 (ED Mich. 2014).

- Denney JT, Gorman BK, Barrera CB. Families, resources, and adult health: Where do sexual minorities fit? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2013; 54 :46–63. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Diamond LM. Sexual fluidity: Understanding women’s love and desire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- DiBennardo R, Gates GJ. Research note: U.S. Census same-sex couple data: Adjustments to reduce measurement error and empirical implications. Population Research and Policy Review. 2014; 33 :603–614. [ Google Scholar ]

- Elder GH, Jr, Johnson MK, Crosnoe R. The emergence and development of life course theory. In: Mortimer JT, Shanahan MJ, editors. Handbook of the life course. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2003. pp. 3–19. [ Google Scholar ]

- Eisikovits Z, Koren C. Approaches to and outcomes of dyadic interview analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2010; 20 :1642–1655. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Farr RH, Patterson CJ. Coparenting among lesbian, gay, and heterosexual couples: Associations with adopted children’s outcomes. Child Development. 2013; 84 :1226–1240. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Festy P. Enumerating same-sex couples in censuses and population registers. Demographic Research. 2008; 17 :339–368. [ Google Scholar ]

- Frost DM, Meyer IH. Internalized homophobia and relationship quality among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009; 56 :97–109. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gates GJ. Geographic trends among same-sex couples in the US Census and the American Community Survey. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gates GJ. LGBT parenting in the United States. Los Angeles. The Williams Institute; 2013a. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gates GJ. Same-sex and different-sex couples in the American Community Survey: 2005–2011. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute; 2013b. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gates GJ, Badgett MVL. Gay and lesbian families: A research agenda. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute; 2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gates GJ, Cook AM. Census snapshot: 2010 methodology—Adjustment procedures for same-sex couple data. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute; 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Goldberg AE. “Doing” and “undoing” gender: The meaning and division of housework in same-sex couples. Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2013; 5 :85–104. [ Google Scholar ]

- Goldberg AE, Kinkler LA, Richardson HB, Downing JB. Lesbian, gay, and heterosexual couples in open adoption arrangements: A qualitative study. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011; 73 :502–518. [ Google Scholar ]

- Goldberg AE, Smith JZ, Kashy DA. Preadoptive factors predicting lesbian, gay, and heterosexual couples’ relationship quality across the transition to adoptive parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010; 24 :221–232. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gonzales G, Blewett LA. National and state-specific health insurance disparities for adults in same-sex relationships. American Journal of Public Health. 2014; 104 :e95–e104. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gotta G, Green R, Rothblum E, Solomon S, Balsam K, Schwartz P. Heterosexual, lesbian, and gay male relationships: A comparison of couples in 1975 and 2000. Family Process. 2011; 50 :353–376. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gottman JM. The roles of conflict engagement, escalation, and avoidance in marital interaction: A longitudinal view of five types of couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993; 61 :6–15. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. State-level policies and psychiatric morbidity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2009; 99 :2275–2281. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. The impact of institutional discrimination of psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health. 2010; 100 :452–459. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, O’Cleirigh C, Grasso C, Mayer K, Safren S, Bradford J. Effect of same-sex marriage laws on health care use and expenditures in sexual minority men: A quasi-natural experiment. American Journal of Public Health. 2012; 102 :285–291. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hollingsworth v. Perry , 133 S. Ct. 2652 (2013).

- Hughes ME, Waite LJ. Marital biography and health at mid-life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2009; 50 :344–358. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000307. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2011. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Joyner K, Manning W, Bogle R. Working Paper. Center for Family and Demographic Research; Bowling Green, OH: 2013. The stability and qualities of same-sex and different-sex couples in young adulthood. Retrieved from http://papers.ccpr.ucla.edu/papers/PWP-BGSU-2013-002/PWP-BGSU-2013-002.pdf . [ Google Scholar ]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kroeger RA, Smock PJ. Cohabitation: Recent research and implications. In: Treas JK, Scott J, Richards M, editors. The Wiley-Blackwell companion to the sociology of families. 2. New York: Wiley-Blackwell; 2014. pp. 217–235. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kurdek LA. Are gay and lesbian cohabiting couples really different from heterosexual married couples? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004; 66 :880–900. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kurdek LA. What do we know about gay and lesbian couples? Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005; 14 :251–254. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kurdek LA. Differences between partners from heterosexual, gay, and lesbian cohabiting couples. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006; 68 :509–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00268.x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lau CQ. The stability of same-sex cohabitation, different-sex cohabitation, and marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012; 74 :973–988. [ Google Scholar ]

- LeBlanc AJ, Frost DM, White RG. Minority stress and stress proliferation among same-sex and other marginalized couples. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2015; 77 :xxx–xxx. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu H, Reczek C, Brown DC. Same-sex cohabitation and self-rated health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2013; 54 :25–45. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McCormack M. Innovative sampling and participant recruitment in sexuality research. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2014; 31 :475–481. [ Google Scholar ]

- Meier A, Hull KE, Ortyl TA. Young adult relationship values at the intersection of gender and sexuality. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009; 71 :510–25. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003; 129 :674–697. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Meyer IH, Wilson PA. Sampling lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009; 56 :23–31. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moore MR. Gendered power relations among women: A study of household decision making in Black, lesbian stepfamilies. American Sociological Review. 2008; 73 :335–356. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moore MR, Stambolis-Ruhstorfer M. LGBT sexuality and families at the start of the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Sociology. 2013; 39 :491–507. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ocobock A. The power and limits of marriage: Married gay men’s family relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2013; 75 :91–205. [ Google Scholar ]

- Parsons JT, Starks TJ, Gamarel KE, Grov C. Non-monogamy and sexual relationship quality among same-sex male couples. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012; 26 :669–677. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Patterson CJ. Family relationships of lesbians and gay men. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000; 62 :1052–1069. [ Google Scholar ]

- Patterson CJ, Riskind RG. To be a parent: Issues in family formation among gay and lesbian adults. Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 2010; 6 :326–340. [ Google Scholar ]

- Patterson CJ, Tornello SL. Gay fathers’ pathways to parenthood: International perspectives. Journal of Family Research. 2010; 22 :103–116. [ Google Scholar ]

- Peplau LA, Fingerhut AW. The close relationships of lesbians and gay men. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007; 58 :405–524. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Peplau LA, Fingerhut AW, Beals KP. Sexuality in the relationships of lesbians and gay men. In: Harvey JH, Wenzel A, Sprecher S, editors. Sexuality in the relationships of lesbians and gay men. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 349–369. [ Google Scholar ]

- Perrin AJ, Cohen PN, Caren N. Are children of parents who had same-sex relationships disadvantaged? A scientific evaluation of the no-differences hypothesis. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health. 2013; 17 :327–336. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pfeffer CA. “Women’s work”? Women partners of transgender men doing housework and emotion work. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010; 72 :165–183. [ Google Scholar ]

- Reczek C. The intergenerational relationships of gay men and lesbian women. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2014 Advance online publication. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reczek C, Elliott S, Umberson D. Commitment without marriage: Union formation among long-term same-sex couples. Journal of Family Issues. 2009; 30 :738–756. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reczek C, Umberson D. Gender, health behavior, and intimate relationships: Lesbian, gay, and straight contexts. Social Science & Medicine. 2012; 74 :1783–1790. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Regnerus M. How different are the adult children of parents who have same-sex relationships? Findings from the New Family Structures Study. Social Science Research. 2012; 41 :752–770. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Riggle E, Rostosky SS, Reedy CS. Online surveys for BGLT research: Issues and techniques. Journal of Homosexuality. 2005; 49 :1–21. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rosenfeld MJ. Couple Longevity in the Era of Same-Sex Marriage in the United States. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2014; 76 :905–918. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12141. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rosenfeld MJ, Thomas RJ, Falcon M. How Couples Meet and Stay Together, Waves 1, 2, and 3: Public version 3.04, plus wave 4 supplement version 1.02 [Computer files] Stanford, CA: Stanford University Libraries; 2011 & 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rothblum ED. An overview of same-sex couples in relationships: A research area still at sea. In: Hope DA, editor. Contemporary perspectives on lesbian, gay, and bisexual identities. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 113–139. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rothblum ED, Balsam KF, Solomon SE. The longest “legal” U.S. same-sex couples reflect on their relationships. Journal of Social Issues. 2011a; 67 :302–315. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rothblum ED, Balsam KF, Solomon SE. Narratives of same-sex couples who had civil unions in Vermont: The impact of legalizing relationships on couples and on social policy. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2011b; 8 :183–191. [ Google Scholar ]

- Russell ST, Driscoll AK, Truong N. Adolescent same-sex romantic attractions and relationships: Implications for substance use and abuse. American Journal of Public Health. 2002; 92 :198–202. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Russell ST, Franz BT, Driscoll AK. Same-sex romantic attraction and experiences of violence in adolescence. American Journal of Public Health. 2001; 91 :903–906. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Savin-Williams RC, Joyner K, Rieger G. Prevalence and stability of self-reported sexual orientation identity during young adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2012; 41 :103–110. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shadish W, Cook T, Campbell D. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith JZ, Sayer AG, Goldberg AE. Multilevel modeling approaches to the study of LGBT-parent families: Methods for dyadic data analysis. In: Goldberg AE, Allen KR, editors. LGBT-parent families. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 307–323. [ Google Scholar ]

- Solomon SE, Rothblum ED, Balsam KF. Pioneers in partnership: Lesbian and gay male couples in civil unions compared with those not in civil unions and married heterosexual siblings. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004; 18 :275–286. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Steinbugler AC. Beyond loving: Intimate racework in lesbian, gay, and straight interracial relationships. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Totenhagen CJ, Butler EA, Ridley CA. Daily stress, closeness, and satisfaction in gay and lesbian couples. Personal Relationships. 2012; 19 :219–233. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ueno K. Same-sex experience and mental health during the transition between adolescence and young adulthood. Sociological Quarterly. 2010; 51 :484–510. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Umberson D, Chen MD, House JS, Hopkins K, Slaten E. The effect of social relationships on psychological well-being: Are men and women really so different? American Sociological Review. 1996; 61 :837–857. [ Google Scholar ]

- Umberson D, Montez JK. Social relationships and health: A flashpoint for health policy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010; 51 :S54–S66. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Umberson D, Thomeer MB, Lodge AC. Intimacy and emotion work in gay, lesbian, and heterosexual relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family (in press) [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Umberson D, Williams K, Powers DP, Liu H, Needham B. You make me sick: Marital quality and health over the life course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006; 47 :1–16. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Waite LJ. Does marriage matter? Demography. 1995; 32 :483–507. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- West C, Zimmerman DH. Accounting for doing gender. Gender & Society. 2009; 23 :112–122. [ Google Scholar ]

- West TV, Popp D, Kenny DA. A guide for the estimation of gender and sexual orientation effects in dyadic data: An actor–partner interdependence model approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008; 34 :321–336. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wienke C, Hill GJ. Does the “marriage benefit” extend to partners in gay and lesbian relationships? Journal of Family Issues. 2009; 30 :259–289. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wight RG, LeBlanc AJ, Badgett MVL. Same-sex legal marriage and psychological well-being: Findings from the California Health Interview Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2013; 103 :339–346. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wolkomir M. Making heteronormative reconciliations the story of romantic love, sexuality, and gender in mixed-orientation marriages. Gender & Society. 2009; 23 :494–519. [ Google Scholar ]

Advertisement

The Direct Effects of Legal Same-Sex Marriage in the United States: Evidence From Massachusetts

- Published: 08 September 2020

- Volume 57 , pages 1787–1808, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Christopher S. Carpenter 1

672 Accesses

10 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

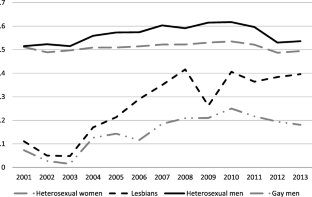

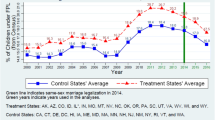

I provide evidence on the direct effects of legal same-sex marriage in the United States by studying Massachusetts, the first state to legalize it in 2004 by court order. Using confidential Massachusetts data from 2001–2013, I show that the ruling significantly increased marriage among lesbians, bisexual women, and gay men compared with the associated change for heterosexuals. I find no significant effects on coupling. Marriage take-up effects are larger for lesbians than for bisexual women or gay men and are larger for households with children than for households without children. Consistent with prior work in the United States and Europe, I find no reductions in heterosexual marriage.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price excludes VAT (USA) Tax calculation will be finalised during checkout.

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Legal recognition of same-sex couples and family formation.

Mircea Trandafir

The Anti-Social Effects of Legalizing Same-Sex Marriage: Fact or Fiction?

Laura Langbein, Brandon Ranallo-Benavidez & Jane E. Palmer

Same-Sex Couples and Their Legalization in Europe: Laws and Numbers

Data availability.

The data sets analyzed for the current study are not publicly available, but researchers can contact the author for information on how to apply for access. Permission must be obtained by the Massachusetts Department of Health.

Throughout, I use the term “sexual minorities” to refer to people with a gay, lesbian, or bisexual orientation or identity. Sexual orientation is a multi-faceted measure that encompasses aspects of sexual attraction, sexual behavior, and sexual identity (i.e., how one sees one’s self). For a discussion of these issues, see Laumann et al. ( 1994 ). A growing number of surveys ask respondents about one or more of these dimensions; the data I use below come from a survey that asks adults about sexual orientation.

See Badgett ( 2011 ) for qualitative evidence on the effects of access to legal same-sex marriage in Massachusetts and the Netherlands on social inclusion. Kolk and Andersson ( 2020 ) examine the effects of legal same-sex registered domestic partnership and legal same-sex marriage on union formation in Sweden using administrative data; they find that the country’s 2009 same-sex marriage policy had little effect on the rate of same-sex union formation.

Most prior demographic research on sexual minorities has relied on data that permit identification of same-sex couples in survey or administrative data (see, e.g., Alden et al. 2015 ; Andersson et al. 2006 ; Black et al. 2000 ; Jepsen and Jepsen 2002 ). The data sets used in these studies can generally not identify single sexual minorities, however, so they are unable to address union formation directly.

Badgett ( 2009 ) also studies the experience of the Netherlands through a series of qualitative interviews and also finds that gay marriage in that country did not have negative effects on different-sex marriage.

Ramos et al. ( 2009 ) also study the Massachusetts reform using data from an online survey sent to people on the mailing list of MassEquality, the state’s largest LGBT equality advocacy group. That study had a low response rate (4.2%) but found that most people in same-sex marriages were women (61%), which also matches the administrative records and my findings below.

To clarify, the national BRFSS core questionnaire does not currently include a question about sexual orientation. Moreover, no other BRFSS-based state surveys included questions about sexual orientation prior to Goodridge , so I cannot compare outcomes over time between Massachusetts and other states. This necessitates my use of a within-state control group (heterosexuals).

If the respondent were female, the word “gay” was replaced with “lesbian.” Other responses that were coded (but not offered as part of the question) were “don’t know/not sure” and “refused.” The main findings on marriage are not sensitive to how I treat individuals choosing these categories (i.e., I can exclude them, dummy them out separately, and/or make extreme assumptions such as assuming they are all gay or lesbian). The placement of the question changed between 2001 and 2002. In 2001 the sexual orientation question was asked at the end of a module on sexual behavior and sex practices. In 2002, the sexual orientation question was moved to the demographics section of the survey (after questions about education and income) where it has remained since.

Results from alternative estimation approaches returned similar results.

The MA-BRFSS provides sampling weights but changed its weighting scheme beginning in 2011 such that the weights are not comparable with the 2001–2010 data (Massachusetts Department of Health 2013 ). Models using the weights for 2001–2010 produced very similar results (Massachusetts Department of Health 2013 ).

This is notable given the long-run decline in marriage nationally (Stevenson and Wolfers 2007 ).

Figure A3 in the online appendix shows a small but noticeable increase in the likelihood that bisexual women report being married after 2004. Samples of bisexual men are extremely small overall and in any individual year; there is no discernable pattern for bisexual men in the figure. Notably, legal uncertainty immediately after marriage licenses were available to same-sex couples may have also led some same-sex couples to get married earlier than they otherwise would have because they feared that the anti-same-sex-marriage activism that was heightened after Goodridge put the availability of legal same-sex marriage in doubt.