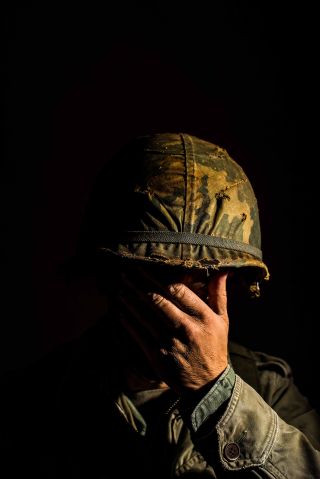

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

The crisis in veterans' mental health and new solutions, veteran suicides increase 10-fold from 2006 to 2020..

Posted November 10, 2023 | Reviewed by Davia Sills

- What Is PTSD?

- Find a therapist to heal from trauma

- Veterans suffer from high rates of mental health conditions, including PTSD, depression, and substance use.

- Suicides among veterans increased 10-fold from 2006 to 2020.

- New treatment strategies are desperately needed.

- Addressing mental and metabolic health simultaneously may lead to better outcomes.

Every year on Veterans Day, we celebrate the brave individuals who have served our country. The mental health challenges that veterans face are both unique and profound. As they transition from service to civilian life, many carry the weight of experiences that significantly impact their well-being. Conventional treatment approaches for conditions such as PTSD , anxiety , depression , and substance abuse are invaluable, yet some veterans continue to struggle with symptoms.

A recent research study published in JAMA Neurology has unearthed a deeply troubling trend: a greater than 10-fold increase in suicide rates among U.S. veterans from 2006 to 2020. Clearly, our current treatment strategies are failing far too many veterans. This is where innovative perspectives, such as the brain energy theory of mental illness, offer fresh hope and understanding.

The brain energy theory, as outlined in this post , posits that mental health conditions are intricately linked with the brain's energy dynamics. A brain with balanced and optimal energy is crucial for mental wellness. For veterans, whose brains are often taxed by the rigors of service and the scars of trauma , ensuring adequate brain energy could be particularly transformative.

Brain energy is, in essence, the currency that powers every thought, emotion , and reaction. This energy stems from the complex interplay of nutrients, hormones , neurotransmitters, and mitochondrial function. For veterans, exposure to stressful environments, trauma, sleep disruption, and physical exertion can lead to a mismatch in energy supply and demand within the brain, potentially exacerbating mental health symptoms.

Research has demonstrated that PTSD, for example, is not just a manifestation of psychological distress but may also be linked to altered metabolism . This can affect the way the brain processes information and responds to stress. By targeting these metabolic processes, we might be able to offer veterans more effective interventions.

How, then, can the brain energy theory guide novel treatment strategies?

- Nutritional Interventions: Tailored nutritional counseling aimed at optimizing brain energy production can be a powerful addition to veterans' treatment plans.

- Exercise and Stress Reduction: Interventions such as targeted exercise regimens may not only enhance overall energy but also improve brain plasticity, resilience , and the regulation of stress hormones. Mind-body practices like yoga and meditation could further aid in rebalancing the brain's energy utilization and emotion regulation mechanisms.

- Specialized Brain Energy Interventions: One promising area is the exploration of supplements, medications, and even light therapy that specifically support mitochondrial function and, consequently, brain energy. While still in the early stages of research, these interventions may offer relief for veterans whose mental health symptoms have been resistant to other treatments. One example is the application of red or near-infrared light to the scalp (transcranial photobiomodulation). In a pilot trial , this intervention was found to improve brain metabolism and reduce symptoms of traumatic brain injury and PTSD.

- Enhanced Psychotherapy : Integrating brain energy optimization into behavioral therapies could amplify their effectiveness. By ensuring the brain is energetically equipped to engage with and benefit from therapy, we can enhance learning, neural growth, and the consolidation of therapeutic gains.

- Comprehensive Care Teams: Coordinated care teams can ensure that veterans receive holistic support, addressing both mental and metabolic health.

The journey toward healing and mental wellness for veterans is both a collective and individual endeavor. By harnessing the principles of brain energy, we can open new avenues for treatment that honor the complexity of the brain and the diversity of experiences among veterans. With continued research and clinical application, this perspective holds the promise of not only alleviating symptoms but also restoring a sense of vitality and hope to those who have served.

As we move forward, it is essential to continue advocating for and investing in research that elucidates the intricate connections between metabolism and mental health. By doing so, we not only pay homage to the sacrifices of our veterans but also elevate our approach to mental health care for all.

Christopher M. Palmer, M.D. , is a Harvard psychiatrist and researcher working at the interface of metabolism and mental health. He is the director of the Department of Postgraduate and Continuing Education at McLean Hospital and an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

'I have PTSD ... So what?' Army veteran's essay resonates

It began with an Army veteran’s exasperated affirmation and a purposely casual question, just 22 keystrokes.

Then, a gush of feelings, dammed up for years by the attached stigma, cascaded from Rob Ulrey’s mind through his fingers to his computer screen; 770 words, a personal purge, a plea for understanding: “I am tormented in my dreams ... I am functional in society ... I am medicated ... I am always on the lookout for danger ... I have no regrets ... I am just as normal as you."

His opening line: “I have PTSD ... So what?”

Last February, that post on Ulrey’s military website — penned partly to set “the media” straight, partly as an online life buoy for men and women like him — resonated with hundreds of current and former service members who posted comments to echo and empathize with the former Army gunner’s frustrations and fears. The reactions haven’t stopped coming: “I am living this with you,” wrote Mike R. on Aug. 27, and “Thanks for these words,” typed Greg H., also on Aug. 27. Talk of the column has spread far and wide among American military ranks.

"The comments it got, and that it's getting, are really kind of inspiring. It seemed like it touched a lot of people. A lot of it was guys and girls who just seemed real lonely out there, real isolated," Ulrey told NBC News. "And they just seemed real relieved there was somebody out there like them."

Ulrey now looks at his essay as — if not the first embers of a true movement — maybe the early moments of a fundamental shift in the public discourse on Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, a series of anxiety-based symptoms afflicting up to an estimated 500,000 U.S. troops who have served in Iraq and Afghanistan. He wrote the article, he said, at roughly the same time he finally sought treatment, 15 years after an IED in Bosnia shattered his wrist, blew out his eardrums and began chronically haunting his slumber.

“It just came out of me, just kind of flowed from the heart,” Ulrey told NBC News. “I guess my higher calling is to make sure other veterans get this message, get the help they need. But If I can make people understand we’re not the big, evil demons that some people make us out to be, so much the better.”

Indeed, the piece was meant to be aimed largely at "mainstream" media outlets, Ulrey said. Amid a litany of news reports in recent years about young veterans committing violence or suicide, he winced at how often journalists swiftly linked the acts to PTSD.

Related: New company offers franchises exclusively to ex-military Related: VA struggling to calculate lost wages for wounded vets, GAO report shows Related: VA won't cover costs of service dogs assigned for PTSD treatment Related: President Obama orders VA to expand suicide prevention services

"I, along with my cohorts, have been classified as a potential powder keg just waiting on that spark to set us off into a murderous explosion of ire. This is not the case," Ulrey wrote in his post.

That sort of breathless PTSD coverage has painted the diagnosis, and perhaps all combat veterans, with a social stain, Ulrey said. PTSD evokes concerned whispers from family members, worried glances from co-workers, and dead-ends at job interviews.

"The stigma is so negative. I’ve heard time and time again from veterans: 'I’m not getting the looks (from companies) that I should be getting. I’m not getting that second interview.' I know some guys who are leaving stuff off their resumes or downplaying what they did during their time in the service so that it doesn’t trigger those kinds of questions (about mental health).

"You’re automatically tainted just because of your service, even if you don’t have PTSD at all," Ulrey said.

But it's not just corporate America that, in Ulrey's view, misunderstands PTSD. Even inside the military, the disorder, and certainlythe act of service members seeking help for it, is often viewed as a personal flaw, or as a lack of mental muscle, he added.

"They’ve been suffering with it and they’ve been afraid to say anything about it, because they were afraid of the ramifications," Ulrey said. "In the military, if you need to go to mental health, then you’re weak. And we don’t have weak in the military. We’re warriors, we’re not supposed to feel this way. But it will take out the baddest dude or the littlest, wimpiest dude. It doesn’t discriminate."

At the top of the U.S. military pyramid, however, leaders say they are toiling to change that old thinking.

"Seeking help is a sign of strength not weakness," said Cynthia O. Smith, a spokeswoman for the Defense Department. "No, military careers aren't at risk for seeking help."

As proof, Smith e-mailed NBC News a memo, signed May 10 by Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta, that read: "Leaders throughout the chain of command must actively promote a constructive command climate that ... encourages individuals to reach out for help when needed."

And on the topic of Ulrey's matter-of-fact pitch for America to stop demonizing PTSD and those diagnosed with it, Smith said: "Mental health disorders, like most medical conditions, are treatable. Many service members with symptoms of PTSD recover with appropriate medication and/or psychotherapy within a few months."

Ulrey's medication includes prescribed blood-pressure drugs that prevent the flashback nightmares he once suffered. Those dreams used to wake him with a jolt four to five times a night and caused him to sweat so profusely that his sheets often were drenched by dawn.

"I have never physically assaulted anyone out of anger or rage," he typed last February. "I have never committed violence in the workplace, just like the vast majority of those who suffer with me. My co-workers know I spent time in the military but they do not know of my daily struggles, and they won’t."

But like any good writer, Ulrey has picked up on the irony in his larger quest to convince the world to simply see soldiers and veterans as regular folks who are dealing with battlefield stress on their own terms. In his current job as a law enforcement officer — he asked to keep his city of residence out of this article to protect his family — Ulrey earlier this month faced a pointed question from his boss.

"He saw the article and asked me: 'Do I need to know anything about this? Do I need to be worried?’ I said, ‘No not at all.'

"It had been bugging him and, I guess, bugging the other supervisors I work with for a couple of months. That was the whole purpose of the article. So that people don’t get that question from co-workers or supervisors," Ulrey said. "Even if we have PTSD, we’re OK. I am not going to freak out on you."

More content from NBCNews.com:

- With 50 days to go, challenges for Romney and Obama

- Chicago mayor sues to end teachers strike

- Richer communities get more funds to clean up toxic brownfields

- Occupy protesters blast 'criminality' of Wall Street

- Video: New evidence could clear Army doc of 1970 slayings

- 19-year-old charged with shaking baby to death

Follow US News from NBCNews.com on Twitter and Facebook

Can Researchers Find Better Treatments for Veterans with PTSD?

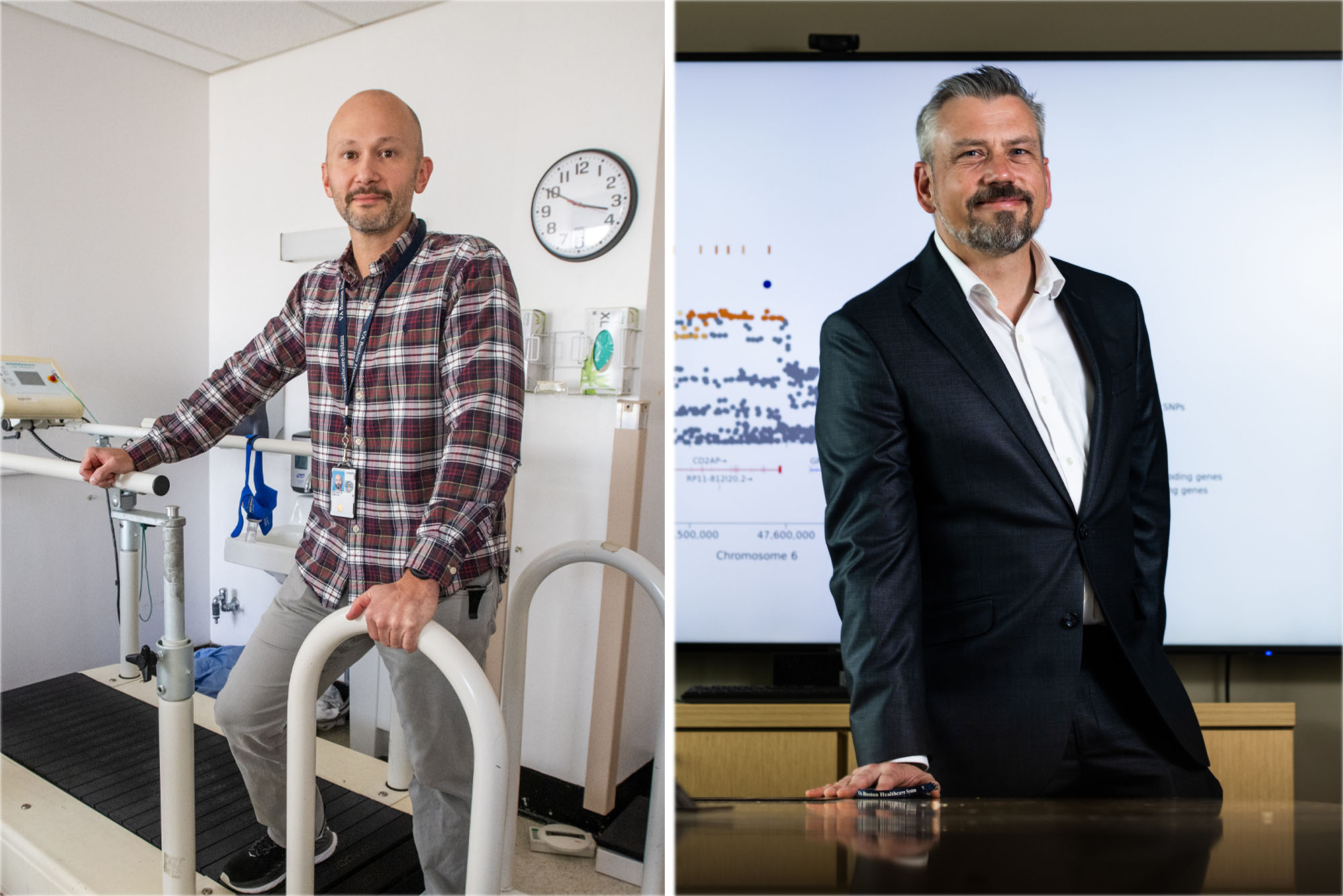

Two veterans turned Boston University researchers are studying PTSD to find better treatments for their former comrades

US Army veteran James Whitworth (left) studies the potential protective qualities of exercise against mental illness, stress, and trauma, particularly PTSD; former Army Reservist Mark Logue (right) searches huge swaths of genetic data for clues to the deep-rooted foundations of PTSD. Photos by Cydney Scott and Jackie Ricciardi

They Served Their Country. Now, They’re Serving Their Fellow Veterans

Molly callahan.

James Whitworth traces the path to his military service in simple terms: “I heard the call, and I answered,” says the Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine assistant professor of psychiatry. It was just after the attacks on September 11, 2001, Whitworth recalls, and he enlisted in the Army “to serve in the global war on terror.”

Whitworth deployed to Iraq, part of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom, along with nearly two million of his compatriots, all told. Just 21 years old and thrust into an unknown landscape with daily threats to his life, Whitworth says he exercised at his base to cope with the stressful situation.

It was certainly a DIY gym setup: rusty weights and heavy tires in a military tent.

“Anything and everything just to stay fit,” Whitworth says. “It was a source of de-stressing; a coping strategy to deal with the rigors of combat. And it just kind of stuck with me, it was like a kernel on the back of my head—I always knew that exercise was a helpful tool for dealing with stress.”

After Whitworth was honorably discharged, this kernel grew into full-fledged research questions for his graduate and then doctoral research. But that research took on new urgency when Whitworth’s close friend, a “battle buddy,” died by suicide, he says.

“It surprised a lot of us. And it really shook things up for me. I wanted to do something, anything,” he says. So, Whitworth refocused his exploration from the human-performance side of exercise, to its potential protective qualities against mental illness, stress, and trauma—particularly post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD.

Mark Logue was a sophomore at the University of Oregon, preparing for his final exams, when he received his call to service—quite literally.

“The phone rang, and they told me to pack my bags,” he recalls. “‘Your unit has been activated and you’re going to Operation Desert Storm,’” an official told him.

As a young person in the late 1980s, Logue registered for the US Army Reserve as a way to cover the cost of college and gain some worthwhile experience at basic training. It seemed like a fairly good deal: the reserves hadn’t been activated in nearly 20 years, since the Vietnam War. That changed in 1990, however, when reservists were ordered to active duty to serve in the Gulf War.

Logue, who worked in the reserves as a medical supply specialist, was sent to Stuttgart, Germany, to help expand a medical facility for combat soldiers wounded in the Gulf. Luckily, he says, the large-scale casualties his unit prepared for never materialized and, soon enough, Logue returned home, where his studies resumed. He remained in the US Army Reserve until 1997, when he was honorably discharged.

Trained as a mathematician and statistician, Logue charted a course for a career in genetics during his doctoral program. He found he could apply his mathematical and programming skills to address real health problems, a deeply gratifying experience.

Logue, currently an associate professor of psychiatry and biomedical genetics at BU’s medical school and of biostatistics at the University’s School of Public Health, was working on genetic studies of anxiety disorders and dementia when he was approached by Mark W. Miller, a researcher in the US Department of Veterans Affairs’ National Center for PTSD. Miller, a professor of psychiatry at BU’s medical school, had asked for Logue’s help in analyzing a set of genetic data from veterans.

He agreed. “I am a veteran and I’m always up for finding out new and interesting things,” Logue says.

Now, Logue and Whitworth both also work at the VA Medical Center in Boston’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood. They’re each seeking answers about PTSD by asking vastly different questions.

What Is PTSD?

Stress responses to traumatic situations are completely normal—a person’s natural flight, fight, or freeze response helps them respond to danger appropriately. For some, however, particularly combat veterans or people who’ve experienced physical or sexual assault, these natural physiological responses linger long after the danger is gone. This is PTSD.

Post-traumatic stress disorder is a condition that “impairs your functioning globally,” Whitworth says. People with PTSD may experience flashbacks or distressing thoughts, avoid people or places that remind them of the traumatic event, experience physical sensations like a higher heart rate or sweating, can have trouble sleeping, and more. It’s an embodied experience.

“This is not just a disorder that makes you sad, depressed, anxious. It impacts your behaviors, your ability to participate in your role in society,” Whitworth says. “And this translates to avoidance and isolation. And so people wind up staying away from a lot of the activities they used to enjoy; maybe they don’t feel safe going to a gym or a park.”

People with PTSD may also avoid exercise because the physiological sensations—elevated heart rate, breathing heavily, sweating—feel similar to a stress response, and they fear it will trigger a panic attack, or worse, Whitworth says.

But his research indicates that this avoidance is often the exact opposite of what will ultimately help.

How Can Exercise Help with PTSD Symptoms?

In a widely cited 2019 trial , Whitworth and his colleagues found evidence that resistance training (such as weight lifting) could have significant beneficial impacts on sleep quality and anxiety for people with PTSD. In subsequent studies, he’s found that improved cardiorespiratory fitness in post-9/11 veterans was associated with lower PTSD severity , and that as little as three weeks of high-intensity resistance exercise is a feasible intervention for symptoms in people with PTSD who aren’t otherwise seeking treatment for it.

“When we get people who have PTSD exercising, they feel better, there’s an impact and it reduces symptoms,” he says. “Is it a cure? A panacea? Absolutely not. But it is a coping strategy. It’s something that might be useful in augmenting other evidence-based practices, such as psychotherapy or medications.”

Whitworth and other physiologists and psychologists are still working to understand why exercise seems to be an effective therapeutic tool, but he says one potential factor could be the same one that makes people avoid exercise: it simulates a stress response—but in a safe and controlled environment. This kind of repeated exposure to those unpleasant sensations may work to normalize them, Whitworth reasons.

Another possible explanation is that exercise, and strength training in particular, builds senses of confidence, self-efficacy, and empowerment, Whitworth says. “Once you complete a challenging workout, or complete a heavy lift, you might think, ‘Well, I mastered this’ or ‘This one wasn’t so bad, maybe I can take on [a lift] that’s a little bigger.’ And that may augment your response to other similar or related stressors.”

Finally, Whitworth is interested in exploring the physiological adaptation that accompanies exercise. Perhaps a more efficient endocrine system—one of many side effects of going from “an untrained state to a trained state,” Whitworth says—helps people metabolize stress better.

Is There a Genetic Component to PTSD?

While Whitworth is interested in gym reps and sets, Logue deals in datasets: huge swaths of genetic data that might hold clues to the deep-rooted foundations of PTSD. He runs computational tests on millions of genetic variants across hundreds or thousands of genomes to find the variants that are statistically associated with a specific disease.

Once Logue identifies those statistically likely variants, other clinical researchers can use that information to identify better, more targeted strategies for the care and treatment of a particular disease.

It’s a technique that’s resulted in a number of important discoveries. Researchers have discovered genetic variations that contribute to the risk of developing type 2 diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, heart disorders, obesity, Crohn’s disease, and prostate cancer.

Logue is part of a consortium of researchers pooling their datasets to search for clusters of genetic variants—small abnormalities in the DNA sequences that make up a gene—that are consistently present among people with PTSD.

Roughly a decade ago, Logue and his colleagues at the National Center for PTSD published the first ever genome-wide association study of PTSD; Logue was the lead author on its results, published in Molecular Psychiatry , an offshoot of Nature . They found a variant in a gene—the retinoid-related orphan receptor alpha, or RORa—that was associated with PTSD. Logue has copublished other papers since then, examining a possible connection between people with PTSD and the sizes of their hippocampus and amygdala , for example.

The genetic differences Logue and other researchers identified may not immediately lead to a cure, but they are an important starting point for clinicians—and could serve as markers on a genetic risk assessment for PTSD, Logue suggests.

Honorably Discharged, but Still Serving

For Logue and Whitworth, this work lives beyond the papers and the publications. It’s more like a calling, and one that could have a real impact for their fellow veterans and service members.

“It’s a personal connection,” Whitworth says. His work, which, like any, can be tedious at times, is made more profound because of that connection. “What gets me up in the morning for this sort of research, it’s not looking at the statistics and seeing significant p-values. It’s getting to talk to other veterans and knowing that the research that I’m doing is for them.”

That connection is true for many people who work at the VA, Whitworth says: “There’s this intrinsic desire to serve those who have served. And that’s powerful.”

It’s certainly true for Logue.

“Working at the VA spurs me on,” Logue says. “To get to my office [at the VA], I walk through the lobby with patients and ride with them in the elevator—these are veterans getting their care there. And then I go upstairs and analyze veteran data, and I’m hoping that the things we do actually help veterans and can lead to treatments; maybe not today, maybe not next week, but eventually.”

Whitworth’s research is primarily funded by the US Department of Veterans Affairs’ Rehabilitation Research & Development Service. Logue’s research is primarily funded by the VA Office of Research & Development, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute on Aging.

Explore Related Topics:

- Data Sciences

- Molecular Biology & Genetics

- Public Health

- Share this story

- 0 Comments Add

Senior Writer

Molly Callahan began her career at a small, family-owned newspaper where the newsroom housed computers that used floppy disks. Since then, her work has been picked up by the Associated Press and recognized by the Connecticut chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists. In 2016, she moved into a communications role at Northeastern University as part of its News@Northeastern reporting team. When she's not writing, Molly can be found rock climbing, biking around the city, or hanging out with her fiancée, Morgan, and their cat, Junie B. Jones. Profile

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.

Post a comment. Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Latest from The Brink

Do immigrants and immigration help the economy, how do people carry such heavy loads on their heads, do alcohol ads promote underage drinking, how worried should we be about us measles outbreaks, stunning new image shows black hole’s immensely powerful magnetic field, it’s not just a pharmacy—walgreens and cvs closures can exacerbate health inequities, how does science misinformation affect americans from underrepresented communities, what causes osteoarthritis bu researchers win $46 million grant to pursue answers and find new treatments, how to be a better mentor, how the design of hospitals impacts patient treatment and recovery, all americans deserve a healthy diet. here’s one way to help make that happen, bu cte center: lewiston, maine, mass shooter had traumatic brain injury, can cleaner classroom air help kids do better at school, carb-x funds 100th project—a milestone for bu-based nonprofit leading antimicrobial-resistance fightback, is covid-19 still a pandemic, what is language and how does it evolve, rethinking our idea of “old age”, can we find a cure for alzheimer’s disease, the secrets of living to 100, how to save for retirement—and why most of us haven’t (or can’t) save enough.

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essay Examples >

- Essays Topics >

- Essay on Therapy

Military Veterans And PTSD Essay

Type of paper: Essay

Topic: Therapy , Treatment , Military , Trauma , Patient , Nursing , Veterans , Psychology

Words: 1400

Published: 02/15/2020

ORDER PAPER LIKE THIS

Military veterans have post-traumatic stress disorder which affects their lives, mentally and even physically. These conditions are treatable and their lives can run smoothly and normally. The rationale of this paper shall be to examine how PTSD conditions affect the military veteran and evaluate brain and physical effects associated and establish ways of treating these conditions. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) refers to some psychological consequences due to exposure to or having being confronted with experiences that were stressful which to the person was highly traumatic. The experience involves threatened or actual death, threat to psychological and or physical integrity. Occasionally it is referred to as post trauma stress reaction so that emphasis on the fact that it is a routine of traumatic experiences. It is therefore not a pre-existing psychological weakness manifestation on the part of the person who have undergone through such traumatic experiences (Tanielian, p. 89) PTSD have physical effect especial on military veteran and on the same note, they have been established to have effect on the brain. There are symptoms associated with the post-traumatic stress disorder which in most of the cases are physical though one may suffer traumatic stress with no signs of post-traumatic stress disorder. The military veteran who has the PTSD condition exhibits some symptoms from time to time. Symptoms of distress are apparent when they recall memories, feelings, thoughts and other event that are associated to the traumatic event they went through. Sounds, sight, smell triggers the memories of veteran with this condition, where they suffer from experiencing of nightmares, hyper vigilance, flashbacks and numbing of responses (Vasterling, Verfaellie and Sullivan, p.675). PTSD symptoms are of three categories that is hyper arousal, re-experiencing and numbing. Hyper arousal can be said to occur when the physiology of the traumatise person is in high gear. In such a case the person is assaulted psychological and have not been able to reset to their normal condition. The symptoms that are associated with hyper arousal are majorly physical for instance difficulty in sleeping, problem with concentrating, irritability, agitation, anger and been easily startled among others (Ciccarelli, p.90). With respect to re-experiencing, the veteran military with this condition are associated with a wide range of symptoms. For instance, they exhibit symptom such as nightmares, reminders of the event that are exaggerated, flashbacks and even body harm on them. Other symptoms that are common with the veteran who have served in the military are numbing. In this case a person feel detached from their feelings and vitality where a sense of deadness replaces it. The symptoms that are associated with numbing are quite dangerous to think of. For instance people with this condition have no interest when it comes to the lives of other people. The patient feel hopeless and in most cases prefer being in isolation. They try as much as possible to be detached from thought and feelings that would bring back the memories of the traumatic events. In addition to that, they feel estranged and detached from other people (Pedersen, p.115)

How PTSD is detected

PTSD can be detected by a doctor who has experience in this field for example in treating and helping persons with mental illness that is psychologists and psychiatrists. The doctor diagnosis the PTSD after the doctor talks to the patient who has shown these conditions. For PTSD to be detected military veteran must have experienced several conditions for not less than one month. Among the condition that they show possible PTSD condition are re-experiencing symptom at least once, and three avoidance symptoms (Ciccarelli, p.110). In addition to that the patient should have experienced two hyper arousal symptoms being the least and other symptom that stop the daily and normal routine that an individual undertakes. The routine activities that are interrupted with are going to work or school, associating with friends, and the general responsibility of taking care of important tasks (Vasterling, Verfaellie and Sullivan, p.677).

Management and treatment

Military veteran have learnt ways to manage these condition to curb anxiety by learning avoidance responses toward experiences that evoke and produce related anxiety. Cognitive processing therapy (CPT), eye movement desensitizing and reprocessing (EMDR) and prolonged exposure (PE) are among the accepted approaches toward effective treatment. There are several other main treatments that veteran military men and women with the PTSD condition are treated. Psychotherapy for instance which involves talk has been one of the most fruitful exercises with regard to treatment. Medication is also used for treatment and in most cases doctors may prefer combing both psychotherapy and medications. Since people are different in various ways, treatment will therefore depend on an individual and therefore varies from one person to the other (Ciccarelli, p.150) Patients with the PTSD condition are advised to be treated by mental health care provider who has the relevant experience. People with PTSD condition are required at times to try a number of treatments so that they can establish which kind of treatment best suits them for their symptoms. If the patient is still going through the problem for instance panic disorder, substance abuse or feeling suicidal among others, it requires that the two problems be treated. This will enable he patient heal fully and successfully. Psychotherapy which is basically a talk therapy involves a talk with a medical professional in relation to health who treats mental illnesses. Psychotherapy can be done individually where the patient attends sessions with the doctor or it can be done as a group (Rand Center for Military Health Policy Research, 3). Talk therapy for patient with PTSD condition in most cases takes 6-12 weeks though it make take longer depending on the health situation of the patient. In psychotherapy, it is required that the patient receives support from the family and friends as it become an important part of healing. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy helps in healing traumatic memories including beliefs, visual images body sensation and emotions (Vasterling, Verfaellie and Sullivan, p.682). There are various types of psychotherapy which the health professional can administer which are usually different from one patient to the other. Therapies teach patient different ways in which they can react to frightening events which arouses PTSD symptoms. After the therapy the patient will have the capacity to use control skill to relax and control anger, use tips for better diet, sleep and exercise habits (Vanderploeg, Belanger and Curtiss, p.1089) There are two medications that have been approved for treating PTSD condition by the United States food and drug administration. They advocated sertraline and paroxetine which are antidepressants used to treat depression. The medication help in controlling symptom associated with PTSD which allows the patients go through psychotherapy. Though there are some side effects associated with the medication, the side effect go away within a few days (Rand Center for Military Health Policy Research, 5). In conclusion, we have established that PTSD are serious conditions that military veteran go through due to traumatic experiences that they go through. There is a solution to these problems through undergoing treatments which entails therapy and medication. PTSD can be detected by medical professionals and be effectively addressed.

Tanielian, Terri L, and Lisa Jaycox. Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Center for Military Health Policy Research, 2008. Internet resource. Walking Your Blues Away: How to Heal the Mind and Create Emotional Well-Being. Inner Traditions, 2006. Internet resource. Pedersen, Darlene D. Psych Notes: Clinical Pocket Guide. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis, 2012. Print. Ciccarelli, Saundra K, and J N. White. Psychology: An Exploration. Upper Saddle River, N.J: Pearson, 2013. Print. Vanderploeg, R.D., Belanger,H.G. and Curtiss.G. "Mild Traumatic Brain Injury and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Their Associations with Health Symptoms." Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 90.7 (2009): 1084-1093. Print. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder: When the Memories Won't Go Away. New York, N.Y: Vasterling Jennifer. J., Verfaellie Mieke., and Sullivan Karen. D. “Mild traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder in returning veterans: Perspectives from cognitive neuroscience.” Clinical Psychology Review, 2009. Vol 29, 674-684

Cite this page

Share with friends using:

Removal Request

Finished papers: 1761

This paper is created by writer with

ID 287477145

If you want your paper to be:

Well-researched, fact-checked, and accurate

Original, fresh, based on current data

Eloquently written and immaculately formatted

275 words = 1 page double-spaced

Get your papers done by pros!

Other Pages

Dreams critical thinkings, homer critical thinkings, iraq critical thinkings, theory critical thinkings, england critical thinkings, culture thesis statements, building germanys holocaust memorial movie review sample, research paper on seated couple, special education article review examples, parents and peers in life span development essay example, example of what price justice essay, free essay on persuasion 2, good case study on planning, sample essay on analyzing your literacy journey, sample critical thinking on picture reflection, good example of corporate branding strategy mercedes benz report, free the yellow wallpaper research paper example, workforce trends term papers examples, social media and information dispensation in society essay examples, jus soli essays, karat essays, washing powder essays, gas station essays, dental procedure essays, dependent clause essays, elated essays, personable essays, speaking english essays, point to point essays, giauque essays, nigerian economy essays, federal republic of nigeria essays, celebreality essays, rocci essays, service staff essays, hatha yoga essays, inner core essays, asanas essays, kundalini essays, matlock essays, writs of assistance essays, lawrenceville essays, mark 13 essays.

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

The Effects of PTSD on Families of Veterans Essay

Introduction.

Posttraumatic stress disorder refers to an extreme anxiety disorder, which erupts from exposure to an event that leads to psychological trauma (Kato et al, 2006, p.23). This event may include death threats, physical threats or threats towards one’s sexual, emotional or psychological integrity, which may affect an individual’s ability to sustain pressure.

Some of the key symptoms of PTSD include increased arousal that results in difficulties in getting sleep, flashbacks, nightmares, severe anxiety, uncontrollable thoughts on an occurrence and stimuli (Kato et al, 2006, p.28). Studies have revealed that symptoms of PTSD that are experienced by veterans may affect their families negatively.

They also show that relationships may serve to either improve or make worse the symptoms that PTSD victims experience (Kato et al, 2006, p.29). PTSD has severe effects on the family of veterans because of its consequences that include depression, avoidance, anger and guilt, sympathy and drug abuse.

PTSD related research has indicated that veterans experience marital problems, violence within the family set up, distressed partners and behavior problems among children (Little, 2011). This is because families will definitely respond to the reality of the person they love who has suffered a trauma.

Symptoms related to trauma make it difficult for someone to get along with people and may result in withdrawal from families or may turn to violence. Lack of emotional connection or lack of sexual interest with spouses may lead to difficulties in relationships (Little, 2011). Some of these individuals develop limited interest to family activities they took pleasure in before.

Families of veterans always sympathize with the suffering that that they undergo through because of PTSD. Family members sympathize with the loved one for what they are experiencing (Little, 2011). The loved one can be sure that there are people who will take care of him/her and feels sorry for what one has to go through.

To some extent though, this kind of sympathy can lead to lowered expectations, which may leave the traumatized loved one feeling as if the family assumes that they are not strong enough to pull through the ordeal by themselves. It is advisable not to treat them as if they are totally disabled as this may push them to seclude themselves. However, with the right kind of care and support, they can eventually feel better.

Depression is another problem that results from effects of PTSD. It mostly appears in family members if the person afflicted by PTSD elicits feelings of either loss or pain, or other emotions that hurt.

Depression in family members can be ascribed to the experience of a traumatic event. Knowledge of a loved one enduring such a difficult time, may lead to intense feelings of hopelessness, helplessness and impending doom (Little, 2011). Depression tends to vary from individual to individual, but there are common signs and symptoms, which could be part of the normal life lows.

Avoidance is a common effect of PTSD that involves evading situations that bring back memories of a traumatic event or occurrence. Family members of the traumatized individual are often fearful of examining and analyzing the traumatic event, just as trauma survivors fear to address whatever happened to them, that was the result of their current situation (Little, 2011).

Whatever the traumatized loved one may avoid, the family members may choose to avoid too, sparing the individual further pain or their reaction to the same. This kind of avoidance may lead to abandonment of regular family activities, thus leading to internal friction and frustrations.

A potential solution to the problem is to get them engage in social activities, unless they are not willing to (Little, 2011). At times, they may e afraid of the safety of other family members. During such instances, family members should not engage in social activities and at that level, it is good to seek professional help immediately.

Anger is an aftermath of PTSD because family members may feel guilty because of their inability to improve the situation of the suffering member by making them happy. The survivor’s family may harbor anger feelings towards the person or party they hold responsible for the experience of their loved one (Little, 2011).

In some cases where the traumatized individual does not stop to dwell on the traumatic event or exhibits funny behavior, the family may also feel anger towards the traumatized individual. In addition, anger may result from the inability of the suffering individual to keep a job or engagement in destructive behaviors such as alcoholism (Little, 2011).

The suffering member’s irritability may also result in anger and guilt in other family members. Family members should learn to overcome the guilt and anger because they are not the cause of the suffering and should focus on helping the suffering family member.

Drug abuse may result from the inadequacies in the coping abilities of family members as they try to come into terms with the suffering of their fellow family member. They result to drug abuse because the suffering of the family member is too much for them to handle. The whole family, especially the trauma survivor, may exhibit this response.

Drugs and substance abuse is common as a response to trauma related stress experienced by the family (National Center for PTSD, 2010). Amongst children, behavioral problems at school are a common thing. Post-traumatic stress disorder can strain mental and emotional wellbeing of the traumatized individual’s family, loved ones or care givers to significant levels (National Center for PTSD, 2010).

To a family, the trauma survivor may look a different person before the trauma due to changes such as increased irritability, depression and withdrawal. Most family members also develop certain behavioral problems such as excessive intake of alcohol, smoking and lack of exercise (National Center for PTSD, 2010). These habits get worse as they try to cope with the great suffering of their loved one

In a family, if a loved one has PTSD, members may feel guilty of their inability to fix the loved one or even speed up the individual’s recovery process. In order for the family to take care of themselves and the traumatized loved one, it is critical for the whole family to prioritize their mental health through exercise, rest and eating right (National Center for PTSD, 2010).Early treatment is better, for the symptoms can at times get worse as well as change family life.

PTSD symptoms often get in the path of family life in setups that have individuals experiencing trauma. The PTSD symptoms can worsen the physical health of a trauma survivor. Treatment administered to traumatized individuals, helps them in overcoming the ordeal. Treatment is also accredited with restitution of control senses and the memory holding power of the nightmare in the individual’s life.

An important aspect in prevention and handling of PTSD is social support. Every family member should be responsible for personal welfare as well as the well being of the member suffering from PTSD. Family members should avoid being too concerned with the suffering member because they may end up neglecting themselves (National Center for PTSD, 2010).

Kato, N., Kawata, M., and Pitman, R. (2006). PTSD: Brain Mechanisms and Clinical Complications . New York: Springer.

Little, S. (2011). How PTSD Affects Families of Veterans . Web.

National Center for PTSD: Effects of PTSD on Family . (2010). Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, January 24). The Effects of PTSD on Families of Veterans. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-effects-of-ptsd-on-families-of-veterans/

"The Effects of PTSD on Families of Veterans." IvyPanda , 24 Jan. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/the-effects-of-ptsd-on-families-of-veterans/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'The Effects of PTSD on Families of Veterans'. 24 January.

IvyPanda . 2024. "The Effects of PTSD on Families of Veterans." January 24, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-effects-of-ptsd-on-families-of-veterans/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Effects of PTSD on Families of Veterans." January 24, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-effects-of-ptsd-on-families-of-veterans/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Effects of PTSD on Families of Veterans." January 24, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-effects-of-ptsd-on-families-of-veterans/.

- American Trauma: Immigrants and War Veterans

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Veterans

- How PTSD Affects Veteran Soldiers' Families

- Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in Veterans and How Family Relationships Are Affected

- Psychiatry: PTSD Following Refugee Trauma

- Trauma and Its Psychological and Behavioral Manifestations

- Secondary Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in Children

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Missouri Veterans

- The Importance of PTSD for Master Leaders Course in the Army

- Traumatic Stress Disorders & Treatment

- Organizational Psychology: Productive and Counterproductive Behaviors

- Self Efficacy, Stress & Coping, and Headspace Program

- Definition and Theories of Environmental Psychology

- Diagnosis of the Patient

- Depression Treatment: Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Advanced Essay #4 [PTSD In Veterans]

M any people in the U.S have served for their country and in doing so, because of certain positions (like a combat veteran), have suffered traumatic experiences because of it. The victims of PTSD can carry a lot of grief along with survivor's guilt for many. When veterans come back from war, they can also struggle with substance abuse, anger issues, isolation, and more. The topic of treatment for vets with PTSD is a somewhat controversial one since treatment options can vary from therapy and psychotropic drugs, to alternatives like marijuana, but since that is still federally illegal, it is hard to bring to light. PTSD, or Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, is a disorder characterized by failure to recover after experiencing or witnessing a terrifying event. It is a big issue since such a large number of people that go into the war have traumatic experiences and can come back with their lives completely changed. PTSD affects about 31 percent of veterans just from the Vietnam War, but not just veterans. About 5.2 million people will experience PTSD in the U.S. during the course of a given year. If you suffer from any type of traumatic experience, you risk the chance of getting PTSD.

Veterans deal with even more issues like losing their houses, jobs, families, and more on top of dealing with mental stress. Psychiatrist and author Jonathan Shay explains how veteran’s personaliti es can be different when they return from combat “In combat, you have to shut down those emotions that do not directly serve survival. So sweetness, the gentler forms of humor, grief -- all shut down. And this is profoundly disconcerting to families when a soldier comes back, and he seems to be made out of ice. It's not that he is irrevocably and permanently incapable of feeling anything, yet that this adaptation of shutting down those emotions that don't directly serve survival in combat is persisting”. While in combat, soldiers are trained to fight and survive, so that leaves them to repress their emotions. Because of the strong belief among soldiers that the only thing that should be on your mind is serving and giving your all, processing what is actually happening is ignored. That is big reason as to why veterans realize that something is wrong when they come home.

Veterans do not realize that they may have a disorder like PTSD until after some time because sometimes they do not know until they recognize the many outbursts, severe anxiety, and insomnia/nightmares. To treat this, vets can get drugs to help with PTSD, but there are many downsides. “Mental health experts say the military's prescription drug problem is exacerbated by a U.S. Central Command policy that dates to October 2001 and provides deploying troops with up to a 180-day supply of prescription drugs under its Central Nervous System formulary.” Many of the drugs prescribed to veterans can be helpful forms of treatment, but the physical strain it puts on their minds and bodies can be even more damaging. Since a lot of the drugs are addictive, if you start to abuse them, it can be near impossible to stop. Drugs like Elavil is an antidepressant that actually caused suicidal thoughts, so the FDA now requires it to carry a black-box warning.

It is clear that militarism is heavily ingrained in our society and PTSD is a consequence of it, in and outside of war. These are ideas that we have to grasp, because people suffer from these disorders whether you recognize it or not. Your mind is so powerful that how you feel can technically be out of your control. PTSD is a real problem people face everyday and it requires awareness, especially for the people that have served for their country.

No comments have been posted yet.

Log in to post a comment.

You can also log in with your email address.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Risk factors associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in US veterans: A cohort study

Jan müller.

1 Institute of Preventive Pediatrics, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany

Sarmila Ganeshamoorthy

2 Division of Cardiology, Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, California, United States of America

3 Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California, United States of America

Jonathan Myers

Associated data.

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

To assess the association between clinical and exercise test factors and the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in US Veterans.

Patients and methods

Exercise capacity, demographics and clinical variables were assessed in 5826 veterans (mean age 59.4 ± 11.5 years) from the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System in Palo Alto, CA. The study participants underwent routine clinical exercise testing between the years 1987 and 2011. The study end point was the development of PTSD.

A total of 723 (12.9%) veterans were diagnosed with PTSD after a mean follow-up of 9.6 ± 5.6 years. Drug abuse (HR: 1.98, CI: 1.33–2.92, p = .001), current smoking (HR: 1.57, CI: 1.35–2.24, p <.001), alcohol abuse (HR: 1.58, CI: 1.12–2.24, p = .009), history of chest pain (HR: 1.48, CI: 1.25–1.75, p <.001) and higher exercise capacity (HR: 1.03, CI: 1.01–1.05, p = .003) were strong independent risk factors for PTSD in a univariate model. Physical activity pattern was not associated with PTSD in either the univariate or multivariate models. In the final multivariate model, current smoking (HR: 1.30, CI: 1.10–1.53, p = .002) history of chest pain (HR: 1.37, CI: 1.15–1.63, p <.001) and younger age (HR: 0.97, CI: 0.97–0.98, p <.001) were significantly associated to PTSD.

Conclusions

Onset of PTSD is significantly associated with current smoking, history of chest pain and younger age. Screening veterans with multiple risk factors for symptoms of PTSD should therefore be taken into account.

Introduction

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a psychiatric condition that develops after experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event such as warfare, sexual assaults, natural disasters, or other life threatening events [ 1 – 3 ]. It is associated with persistent mental and emotional stress, substance abuse, smoking, increased violence, poor work performance and poor quality of life in US war veterans [ 3 – 5 ]. The National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study reported a lifetime incidence of PTSD of 30% and a current prevalence of 15%, whereas the normal estimated lifetime occurrence of PTSD is 6.8% [ 2 , 6 ].

The association between history of smoking, substance abuse and alcohol abuse in posttraumatic stress disorder have been well established [ 7 – 10 ]. Chronic substance use can increase anxiety and agitation. In an event of traumatic exposure, substance use affects the neurological systems thus increasing the vulnerability of developing PTSD [ 11 ]. Therefore, PTSD is considered a causal risk factor for substance use disorders, when substances are used to relieve distressing symptoms of PTSD [ 3 , 9 ].

Individuals with PTSD also have a high prevalence of comorbidities associated with low physical activity, poor fitness or both, including obesity, diabetes and metabolic syndrome [ 12 – 14 ]. It has been demonstrated that physical activity is effective in decreasing depressive symptoms associated with PTSD [ 14 ] and may also be useful for improving other health conditions among individuals with PTSD including exercise capacity, and components of the metabolic syndrome such as waist circumference, blood pressure and blood lipid levels which increase cardiovascular risk [ 13 ].

The Veterans Exercise Testing Study (VETS), is an ongoing, prospective evaluation of Veteran subjects referred for exercise testing for clinical reasons, designed to address exercise test, clinical, and lifestyle factors and their association with health outcomes. Given that Veterans have a particularly high prevalence of PTSD, the VETS cohort provided an opportunity to assess the prevalence and factors, particularly exercise capacity and physical activity patterns, which might influence the development of PTSD.

A cohort of 5826 Veterans (59.4 ± 11.5 years) who were referred for a single maximal treadmill test at the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System between 1987 and 2011 were considered. 335 Patients with PTSD disorder before the exercise test were excluded from the study. Historical information that was recorded at the time of the exercise test included previous myocardial infarction by history or presence of Q-waves, cardiac procedures, heart failure, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia (>220 mg/dL, statin use, or both), claudication, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, renal disease, diabetes, stroke, smoking status (never, former, and current smoker), and use of cardiac medications. Diabetes status was classified as use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents. Participation in regular activity was evaluated by a patient’s binary response to the question: “At least 3 times a week, do you engage in some form of regular activity such as brisk walking, jogging, bicycling, or swimming, long enough to work up a sweat, get your heart thumping, or become short of breath?” Subjects who answered yes to this question were classified as meeting the minimal criteria for physical activity outlined by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) Guidelines [ 15 , 16 ]. The study was approved by the Investigational Review Board (IRB) at Stanford University (Board number: 12061)

Exercise testing

Participants underwent symptom limited treadmill testing using an individualized ramp treadmill protocol as described previously [ 17 ]. Standard criteria for termination were used including moderately-severe angina, >2.0 mm horizontal or down sloping ST segment depression, decrease in systolic blood pressure and serious rhythm disturbances. The Borg 6–20 perceived exertion scale was used to quantify degree of effort. Blood pressure was taken manually, and exercise capacity (in metabolic equivalents [METs]) was estimated from peak treadmill peak speed and grade (ACSM). Medications were not withheld. Subjects whose tests were terminated prematurely because of orthopedic or other limitations were excluded.

The study end point was the development of PTSD (ICD-9-CM 309.81) as diagnosed and recorded electronically by the patient’s primary care physician. The Veterans Affairs computerized medical records system (CPRS) was used to verify date of onset of PTSD.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were preformed using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0). Descriptive data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables are presented in absolute numbers or as percentages where appropriate. Comparisons of patients developing vs. not developing PTSD were performed using unpaired student’s t-tests for continuous variables and chi 2 tests for categorical variables.

Independent associations with onset of PTSD were estimated using Cox proportional hazards analysis. Two separate models were developed. First, the effect of anthropometrics, cardiovascular and other risk factors, exercise and medications were assessed in a univariate model. Second, all variables that exhibited a significant univariate association were tested in a multivariate model. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were used to derive the cut-off-value for highest sensitivity and specify from the multivariate model. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated to illustrate the association between risk factors including smoking, chest pain and age and the onset of PTSD. For all analyses, a probability value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In total, 723 (12.9%) patients were diagnosed with PTSD after a mean follow-up of 9.6 ± 5.6 years. Table 1 summarizes patients’ characteristics including demographics, risk factors and medications among the entire study group, and in patients who developed and did not develop PTSD.

BMI: Body Mass Index, MET: metabolic equivalent, CI: confidence interval, ACE: Angiotensin-converting enzyme, CVD: Cardiovascular disease

*comparing patients with cognitive impairment to those without by a Student’s t-test or chi 2 if appropriate

As shown in Table 2 , drug abuse (HR: 1.98, CI: 1.33–2.92, p = .001), current smoking (HR: 1.57, CI: 1.35–2.24, p <.001), history of alcohol abuse (HR: 1.58, CI: 1.12–2.24, p = .009), history of chest pain (HR: 1.48, CI: 1.25–1.75, p <.001) and higher exercise capacity (HR [per MET]: 1.03, CI: 1.01–1.05, p = .003) were significant independent risk factors for PTSD in a univariate model. Higher age (HR: 0.970, Cl: 0.964–0.977, p<0.001), use of antihypertensive drugs (HR: 0.735, Cl: 0.592–0.911, p = 0.005) and history of cardiovascular disease (HR: 0.751, Cl: 0.624–0.902, p = 0.002) made PTSD more unlikely in the univariate model ( Table 2 ). Physical activity pattern were not associated with PTSD.

In the final multivariate model ( Table 2 ) only current smoking (HR: 1.30, CI: 1.10–1.53, p = .002) history of chest pain (HR: 1.37, CI: 1.15–1.63, p <.001) and younger age (HR: 0.97, CI: 0.97–0.98, p <.001) remained significantly associated with PTSD. ROC analysis revealed that an age <59.4 years had the highest sensitivity and specificity for onset of PTSD. Freedom from PTSD stratified for the three independent risk factors current smoking, history of chest pain and age younger than 59.4 years is illustrated in Fig 1 .

This study shows that younger age, current smoking and history of chest pain were strong independent risk factors for developing PTSD. PTSD was less prevalent in older than younger veterans. Different perception of symptoms including higher somatic complaints and lower arousal, guilt or depression are reported in older veterans. Selective mortality may also contribute to these findings since it has been shown that veterans with more severe symptoms die younger [ 18 ]. An even simpler explanation might be that PTSD is a “younger” disease and is therefore just overlooked in the older population [ 19 ]

Our results suggest a possible link between substance abuse and development of PTSD given that history of drug and alcohol abuse were significantly associated with PTSD in the univariate model. This may be attributable to the tendency for those with PTSD to abuse drugs in order to improve PTSD symptoms. Substance abuse decreases concentration and is associated with irritability, insomnia, aggression and anger. Substance abuse may also increase hyperarousal and re-experience of PTSD symptoms as well as represent a form of self-medication [ 1 , 11 ]. Other studies have shown that CNS depressants such as alcohol and drugs acutely improve PTSD symptoms[ 10 ]. Furthermore, the severity and duration of substance abuse accelerates symptoms of PTSD [ 11 , 20 ]. Vujanovic et al. reported that individuals with cocaine-use disorders, compared to those without, had a two-fold higher incidence of PTSD [ 1 ]. Chronic substance abuse can lead to higher levels of arousal which makes an individual more vulnerable to the development of PTSD [ 11 ]. Studies of PTSD patients with cocaine dependence suggest that cocaine users were more likely to suffer from comorbid major depression than were patients in whom PTSD developed after the onset of cocaine use [ 10 ]. Depression changes mood, decreases concentration and causes insomnia. These symptoms may contribute to hyperarousal thus contributing to development of PTSD.

In the present study, drug and alcohol abuse were univariately related to PTSD but only current smoking remained in the multivariate model. Other reports suggest that patients with PTSD use cigarettes to reduce the negative effects that arise from daily stressors [ 21 ]. Beckham et al. examined smoking in subjects with PTSD and observed that motivation to smoke cigarettes was attributable to an effort to reduce negative affect [ 8 ]. In response to trauma and stress, smokers with PTSD reported greater increases in negative affect and cigarette craving compared to smokers without PTSD. In addition, those with PTSD were more likely to smoke in response to negative affect and were more likely to report a reduction in negative affect after smoking a cigarette than those without PTSD [ 22 ].

A mutual maintenance theory model has been developed in order to explain the complex interaction between PTSD and pain [ 23 ]. In our study chest pain was an important contributor to the development of PTSD; a 31% increase in the development of PTSD was observed among Veterans with a history of chest pain. Chest pain may be related to re-experiencing symptoms of PTSD and may serve as symbolic or actual reminder of their traumatic exposures. The pain may be due to stressors or related to other psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression and somatic symptoms in PTSD patients [ 24 , 25 ]. Reduced levels of activity are also common in both chronic pain and PTSD leading to increased levels of disability [ 23 ]. Anxiety in PTSD patients may directly influence the perception of pain [ 25 – 27 ]. In PTSD, aggravation of pain or maintenance of pain might be due to efforts made to control the pain by behavioral avoidance and physiological arousal [ 27 , 28 ]. Future studies should be conducted to determine underlying causes of chest pain and related distress in chronic PTSD patients. Other studies should be designed to determine whether chest pain is associated with hypochondriasis, hysteria or re-experiencing symptoms among combat Veterans with PTSD and the extent to which chest pain causes disability.

Physical activity that goes hand in hand with physical fitness is often recommended as a treatment for psychiatric disorders [ 14 ]. In the univariate model we observed contrasting results given that for every MET increase the risk of developing PTSD increased by 3%. We can assume that this is due to bias in data collection. Among PTSD patients, exercise levels are often lower due to their depressive mood [ 29 ]. In addition, physical fitness might be associated or confounded by history of cardiovascular disease and antihypertensive treatment that showed only bivariate associations. It should be noted that hypertension increases the risk of intellectual dysfunction by increasing susceptibility to ischemic brain injury and cerebrovascular pathology causing cognitive decline. Therefore antihypertensive agents are used as protective mechanisms. For example, Prazosin is a classic example of antihypertensive medication that is commonly used to treat the trauma-related nightmares in PTSD. A complete understanding of the interactions between these cardiovascular risk factors, medications, drug abuse, alcohol and smoking is elusive and requires further study.

Since exercise is associated with other health benefits such as a reduction of cardiovascular risk factors, it might also help patients to develop a more optimistic view of their overall health. In our study there was neither an association between PTSD incidence and exercise capacity or physical activity in the multivariate model. Possible reasons might be the single question item to assess physical activity and that both physical activity and fitness were only assessed once and might have changed over time. Nevertheless, various types of physical activity interventions, including aerobic exercise or strength and flexibility training, significantly decrease clinical symptoms of mood and anxiety disorders [ 30 , 31 ]. Bandura et al. [ 30 ] proposed social cognitive theory to modulate behavioral changes. Physical activity may interrupt the vicious cycle of pain, fear, and mood disorders. In addition, Manger and Motta's aerobic exercise intervention for PTSD showed promising results for symptom management, including reductions in depression and anxiety symptoms [ 32 ].

PTSD is a highly prevalent lifetime disorder common in the military service. Current smoking, history of chest pain and younger age were significantly related to the onset of PTSD. Although physical activity and fitness were not associated with development of PTSD, exercise has been demonstrated to be an effective intervention in treating patients with PTSD and should be included in the rehabilitation process. Identifying further risk factors for the development of PTSD is important for understanding and developing better treatment strategies for this disorder.

Limitations

Reverse causality, which is the possibility that there may have been patients with subclinical PTSD at the time of the exercise test that influenced the outcome cannot be ruled out. The operationalization of PTSD onset is difficult because many factors influence medical record entries. Occurrence rate of drug and alcohol abuse was low, which may have limited their significance in the multivariate model. Physical activity was assessed by only a single question which might explain its lack of association with PTSD. Our study sample was comprised entirely of male subjects and the results may not be applicable to women. Several risk factors including physical inactivity, smoking, drug or alcohol abuse as well as cardiovascular history were based on recall, and therefore may not have been defined precisely. Finally, all baseline characteristics were only assessed once and may have changed over time.

Supporting information

Funding statement.

Dr. Müller was supported by a Marie Curie International Research Staff Exchange Scheme Fellowship within the 7th European Community Framework Program. This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Technical University of Munich (TUM) in the framework of the Open Access Publishing Program.

Data Availability

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD in Vietnam Veterans was determined to be approximately 30.9% (Kulka et al., 1990) while prevalence for Gulf War Veterans and Veterans of Operation Iraqi Freedom were cited as 10.1% (Kang et al., 2003) and between 13.8% and 20% (Hoge et al., 2004; Tanielian & Jaycox, 2008), respectively. The ...

Key points. Veterans suffer from high rates of mental health conditions, including PTSD, depression, and substance use. Suicides among veterans increased 10-fold from 2006 to 2020. New treatment ...

Prevalence of PTSD in Veterans. Estimates of PTSD prevalence rates among returning service members vary widely across wars and eras. In one major study of 60,000 Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, 13.5% of deployed and nondeployed veterans screened positive for PTSD, 12 while other studies show the rate to be as high as 20% to 30%. 5, 13 As many as 500,000 U.S. troops who served in these wars over ...

547 Words3 Pages. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, also known as PTSD, is a mental disorder that most often develops after a veteran experiences a traumatic event. While having this illness, the veteran believes their lives are in danger. They also may feel afraid or feel they have no control over what is happening.

Army veteran's essay resonates. It began with an Army veteran's exasperated affirmation and a purposely casual question, just 22 keystrokes. Then, a gush of feelings, dammed up for years by the ...

PTSD is still in the process of becoming more appropriately diagnosed and discussed as a serious medical issue among military personnel and veterans. Living with PTSD side affects is debilitating and interfere with everyday life. Symptoms of this disease include nightmares, aggression, memory problems, loss of positive emotions, and withdraw ...

Two veterans turned Boston University researchers are studying PTSD to find better treatments for their former comrades. November 8, 2023. Molly Callahan. James Whitworth traces the path to his military service in simple terms: "I heard the call, and I answered," says the Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine assistant ...

The effects of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can be severe, and long lasting. Though understanding of PTSD began to grow after World War II, and expanded significantly beginning in the 1980s, many veterans describe being diagnosed only recently, having lived for years with symptoms such as nightmares, anxiety, anger and difficulty maintaining personal and professional relationships.

People with PTSD can experience a number of distressing and persistent symptoms, including re-experiencing trauma through flashbacks and nightmares, emotional numbness, sleep problems, dificulties in relationships, sudden anger, and drug and alcohol misuse. Recently, reckless and self-destructive behavior has been added as a PTSD symptom.

PTSD affects on the family. According to Moon (63) once the soldier returns home after the mission, the family members will begin to notice certain changes. These changes are contributed to the trauma of war that the veteran had to endure. Changes include nightmares during sleep which could occur on regular basis.

Military Veterans And PTSD Essay. Military veterans have post-traumatic stress disorder which affects their lives, mentally and even physically. These conditions are treatable and their lives can run smoothly and normally. The rationale of this paper shall be to examine how PTSD conditions affect the military veteran and evaluate brain and ...

Some of the key symptoms of PTSD include increased arousal that results in difficulties in getting sleep, flashbacks, nightmares, severe anxiety, uncontrollable thoughts on an occurrence and stimuli (Kato et al, 2006, p.28). Studies have revealed that symptoms of PTSD that are experienced by veterans may affect their families negatively.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is common in the general population (6.8% lifetime prevalence; Kessler, Berglund, Delmer, Jin, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005) and even more prevalent in veterans, with up to 14% of recently returning veterans being diagnosed (Tanielian & Jaycox, 2008).Low engagement in treatment is a common problem in the veteran population.

PTSD On Veterans Essay. PTSD has had a major impact on veterans and their families who have fought in war. Studies show that over the past 13 years, about 500,000 US soldiers have been diagnosed with the disorder (Thomas). This does not only cause problems for the veteran with PTSD, but the families are affected in many ways also.

PTSD, or Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, is a disorder characterized by failure to recover after experiencing or witnessing a terrifying event. It is a big issue since such a large number of people that go into the war have traumatic experiences and can come back with their lives completely changed. PTSD affects about 31 percent of veterans ...

In the most recent wars, there has been a rise in PTSD diagnosis in combat veterans. According to the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, "About 11-20 out of every 100 Veterans (or between 11-20%) who served in Operation Iraqi Freedom or Operation Enduring Freedom have PTSD in a given year" (How Common Is PTSD in Veterans).

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a psychiatric disorder that results from the experience or witnessing of traumatic or life-threatening events. PTSD has profound psychobiological correlates, which can impair the person's daily life and be life threatening. In light of current events (e.g. extended combat, terrorism, exposure to certain ...

PTSD In Veterans Essay. 551 Words3 Pages. On Tuesday, October 27, Dr. Brittany Hall gave a talk on PTSD in culture affecting military veteran and active duty soldiers. During active duty soldiers are exposed to a lot of unforeseen events. Veterans and active duty soldiers are serving to protect the country from allies, and place their lives on ...

Mental Health For Veterans Essay 1372 Words | 6 Pages. Anne C. Black and other people have been in school of medicine. They have written a report that show the type of treatment veterans get for their PTSD. The VA health care has found better ways to help with the mental health of veterans( Black et al. 1).

The Union of Concerned Scientist found that the Department of Defense stated that, "The U.S. Army allegedly pressured psychologists not to diagnose Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) to free the Army from providing long-term, expensive care for soldiers. The Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) has also been implicated in pressuring staff to ...

Some people develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after experiencing a shocking, scary, or dangerous event. It is natural to feel afraid during and after a traumatic situation. Fear is a part of the body's normal "fight-or-flight" response, which helps us avoid or respond to potential danger. People may experience a range of ...

Introduction. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a psychiatric condition that develops after experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event such as warfare, sexual assaults, natural disasters, or other life threatening events [1-3].It is associated with persistent mental and emotional stress, substance abuse, smoking, increased violence, poor work performance and poor quality of life in ...

In fact, many PTSD patients, especially from military and first responder populations, present with non-fear emotional responses 2. Many areas of the world operate on the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (ICD) to guide psychiatric diagnoses, rather than the DSM-5. The ICD typically adopts a simpler approach ...