11.3 Prejudice, Discrimination, and Racism

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Explain the difference between stereotypes, prejudice, discrimination, and racism

- Identify different types of discrimination

- View racial tension through a sociological lens

It is important to learn about stereotypes before discussing the terms prejudice, discrimination, and racism that are often used interchangeably in everyday conversation. Stereotypes are oversimplified generalizations about groups of people. Stereotypes can be based on race, ethnicity, age, gender, sexual orientation—almost any characteristic. They may be positive (usually about one’s own group) but are often negative (usually toward other groups, such as when members of a dominant racial group suggest that a subordinate racial group is stupid or lazy). In either case, the stereotype is a generalization that doesn’t take individual differences into account.

Where do stereotypes come from? In fact, new stereotypes are rarely created; rather, they are recycled from subordinate groups that have assimilated into society and are reused to describe newly subordinate groups. For example, many stereotypes that are currently used to characterize new immigrants were used earlier in American history to characterize Irish and Eastern European immigrants.

Prejudice refers to the beliefs, thoughts, feelings, and attitudes someone holds about a group. A prejudice is not based on personal experience; instead, it is a prejudgment, originating outside actual experience. Recall from the chapter on Crime and Deviance that the criminalization of marijuana was based on anti-immigrant sentiment; proponents used fictional, fear-instilling stories of "reefer madness" and rampant immoral and illegal activities among Spanish-speaking people to justify new laws and harsh treatment of marijuana users. Many people who supported criminalizing marijuana had never met any of the new immigrants who were rumored to use it; the ideas were based in prejudice.

While prejudice is based in beliefs outside of experience, experience can lead people to feel that their prejudice is confirmed or justified. This is a type of confirmation bias. For example, if someone is taught to believe that a certain ethnic group has negative attributes, every negative act committed someone in that group can be seen as confirming the prejudice. Even a minor social offense committed by a member of the ethnic group, like crossing the street outside the crosswalk or talking too loudly on a bus, could confirm the prejudice.

While prejudice often originates outside experience, it isn't instinctive. Prejudice—as well as the stereotypes that lead to it and the discrimination that stems from it—is most often taught and learned. The teaching arrives in many forms, from direct instruction or indoctrination, to observation and socialization. Movies, books, charismatic speakers, and even a desire to impress others can all support the development of prejudices.

Discrimination

While prejudice refers to biased thinking, discrimination consists of actions against a group of people. Discrimination can be based on race, ethnicity, age, religion, health, and other categories. For example, discrimination based on race or ethnicity can take many forms, from unfair housing practices such as redlining to biased hiring systems. Overt discrimination has long been part of U.S. history. In the late nineteenth century, it was not uncommon for business owners to hang signs that read, "Help Wanted: No Irish Need Apply." And southern Jim Crow laws, with their "Whites Only" signs, exemplified overt discrimination that is not tolerated today.

Discrimination also manifests in different ways. The scenarios above are examples of individual discrimination, but other types exist. Institutional discrimination occurs when a societal system has developed with embedded disenfranchisement of a group, such as the U.S. military's historical nonacceptance of minority sexualities (the "don't ask, don't tell" policy reflected this norm).

While the form and severity of discrimination vary significantly, they are considered forms of oppression. Institutional discrimination can also include the promotion of a group's status, such in the case of privilege, which is the benefits people receive simply by being part of the dominant group.

Most people have some level of privilege, whether it has to do with health, ability, race, or gender. When discussing race, the focus is often on White privilege , which is the societal privilege that benefits White people, or those perceived to be White, over non-White people in some societies, including the United States. Most White people are willing to admit that non-White people live with a set of disadvantages due to the color of their skin. But until they gain a good degree of self-awareness, few people are willing to acknowledge the benefits they themselves receive by being a part of the dominant group. Why not? Some may feel it lessens their accomplishments, others may feel a degree of guilt, and still others may feel that admitting to privilege makes them seem like a bad or mean person. But White (or other dominant) privilege is an institutional condition, not a personal one. It exists whether the person asks for it or not. In fact, a pioneering thinker on the topic, Peggy McIntosh, noted that she didn't recognize privilege because, in fact, it was not based in meanness. Instead, it was an "invisible weightless knapsack full of special provisions" that she didn't ask for, yet from which she still benefitted (McIntosh 1989). As the reference indicates, McIntosh's first major publication about White privilege was released in 1989; many people have only become familiar with the term in recent years.

Prejudice and discrimination can overlap and intersect in many ways. To illustrate, here are four examples of how prejudice and discrimination can occur. Unprejudiced nondiscriminators are open-minded, tolerant, and accepting individuals. Unprejudiced discriminators might be those who unthinkingly practice sexism in their workplace by not considering women or gender nonconforming people for certain positions that have traditionally been held by men. Prejudiced nondiscriminators are those who hold racist beliefs but don't act on them, such as a racist store owner who serves minority customers. Prejudiced discriminators include those who actively make disparaging remarks about others or who perpetuate hate crimes.

Racism is a stronger type of prejudice and discrimination used to justify inequalities against individuals by maintaining that one racial category is somehow superior or inferior to others; it is a set of practices used by a racial dominant group to maximize advantages for itself by disadvantaging racial minority groups. Such practices have affected wealth gap, employment, housing discrimination, government surveillance, incarceration, drug arrests, immigration arrests, infant mortality and much more (Race Forward 2021).

Broadly, individuals belonging to minority groups experience both individual racism and systemic racism during their lifetime. While reading the following some of the common forms of racism, ask yourself, “Am I a part of this racism?” “How can I contribute to stop racism?”

- Individual or Interpersonal Racism refers to prejudice and discrimination executed by individuals consciously and unconsciously that occurs between individuals. Examples include telling a racist joke and believing in the superiority of White people.

- Systemic Racism , also called structural racism or institutional racism, is systems and structures that have procedures or processes that disadvantages racial minority groups. Systemic racism occurs in organizations as discriminatory treatments and unfair policies based on race that result in inequitable outcomes for White people over people of color. For example, a school system where students of color are distributed into underfunded schools and out of the higher-resourced schools.

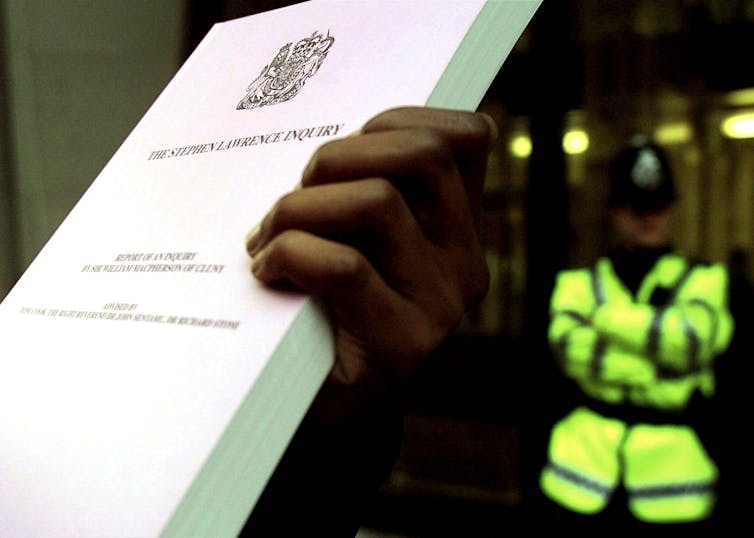

- Racial Profiling is a type of systemic racism that involves the singling out of racial minorities for differential treatment, usually harsher treatment. The disparate treatment of racial minorities by law enforcement officials is a common example of racial profiling in the United States. For example, a study on the Driver's License Privilege to All Minnesota Residents from 2008 to 2010 found that the percentage of Latinos arrested was disproportionally high (Feist 2013). Similarly, the disproportionate number of Black men arrested, charged, and convicted of crimes reflect racial profiling.

- Historical Racism is economic inequality or social disparity caused by past racism. For example, African-Americans have had their opportunities in wealth, education and employment adversely affected due to the mistreatment of their ancestors during the slavery and post-slavery period (Wilson 2012).

- Cultural Racism occurs when the assumption of inferiority of one or more races is built into the culture of a society. For example, the European culture is considered supposedly more mature, evolved and rational than other cultures (Blaut 1992). A study showed that White and Asian American students with high GPAs experience greater social acceptance while Black and Native American students with high GPAs are rejected by their peers (Fuller-Rowell and Doan 2010).

- Colorism is a form of racism, in which someone believes one type of skin tone is superior or inferior to another within a racial group. For example, if an employer believes a Black employee with a darker skin tone is less capable than a Black employee with lighter skin tone, that is colorism. Studies suggest that darker skinned African Americans experience more discrimination than lighter skinned African Americans (Herring, Keith, and Horton 2004; Klonoff and Landrine 2000).

- Color-Avoidance Racism (sometimes referred to as "colorblind racism") is an avoidance of racial language by European-Americans that ignores the fact that racism continues to be an issue. The U.S. cultural narrative that typically focuses on individual racism fails to recognize systemic racism. It has arisen since the post-Civil Rights era and supports racism while avoiding any reference to race (Bonilla-Silva 2015).

How to Be an Antiracist

Almost all mainstream voices in the United States oppose racism. Despite this, racism is prevalent in several forms. For example, when a newspaper uses people's race to identify individuals accused of a crime, it may enhance stereotypes of a certain minority. Another example of racist practices is racial steering , in which real estate agents direct prospective homeowners toward or away from certain neighborhoods based on their race.

Racist attitudes and beliefs are often more insidious and harder to pin down than specific racist practices. They become more complex due to implicit bias (also referred to as unconscious bias) which is the process of associating stereotypes or attitudes towards categories of people without conscious awareness – which can result in unfair actions and decisions that are at odds with one’s conscious beliefs about fairness and equality (Osta and Vasquez 2021). For example, in schools we often see “honors” and “gifted” classes quickly filled with White students while the majority of Black and Latino students are placed in the lower track classes. As a result, our mind consciously and unconsciously starts to associate Black and Latino students with being less intelligent, less capable. Osta and Vasquez (2021) argue that placing the student of color into a lower and less rigorous track, we reproduce the inequity and the vicious cycle of structural racism and implicit bias continues.

If everyone becomes antiracist, breaking the vicious cycle of structural racism and implicit bias may not be far away. To be antiracist is a radical choice in the face of history, requiring a radical reorientation of our consciousness (Kendi 2019). Proponents of anti-racism indicate that we must work collaboratively within ourselves, our institutions, and our networks to challenge racism at local, national and global levels. The practice of anti-racism is everyone’s ongoing work that everyone should pursue at least the following (Carter and Snyder 2020):

- Understand and own the racist ideas in which we have been socialized and the racist biases that these ideas have created within each of us.

- Identify racist policies, practices, and procedures and replace them with antiracist policies, practices, and procedures.

Anti-racism need not be confrontational in the sense of engaging in direct arguments with people, feeling terrible about your privilege, or denying your own needs or success. In fact, many people who are a part of a minority acknowledge the need for allies from the dominant group (Melaku 2020). Understanding and owning the racist ideas, and recognizing your own privilege, is a good and brave thing.

We cannot erase racism simply by enacting laws to abolish it, because it is embedded in our complex reality that relates to educational, economic, criminal, political, and other social systems. Importantly, everyone can become antiracist by making conscious choices daily. Being racist or antiracist is not about who you are; it is about what you do (Carter and Snyder 2020).

What does it mean to you to be an “anti-racist”? How do see the recent events or protests in your community, country or somewhere else? Are they making any desired changes?

Big Picture

Racial tensions in the united states.

The death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri on August 9, 2014 illustrates racial tensions in the United States as well as the overlap between prejudice, discrimination, and institutional racism. On that day, Brown, a young unarmed Black man, was killed by a White police officer named Darren Wilson. During the incident, Wilson directed Brown and his friend to walk on the sidewalk instead of in the street. While eyewitness accounts vary, they agree that an altercation occurred between Wilson and Brown. Wilson’s version has him shooting Brown in self-defense after Brown assaulted him, while Dorian Johnson, a friend of Brown also present at the time, claimed that Brown first ran away, then turned with his hands in the air to surrender, after which Wilson shot him repeatedly (Nobles and Bosman 2014). Three autopsies independently confirmed that Brown was shot six times (Lowery and Fears 2014).

The shooting focused attention on a number of race-related tensions in the United States. First, members of the predominantly Black community viewed Brown’s death as the result of a White police officer racially profiling a Black man (Nobles and Bosman 2014). In the days after, it was revealed that only three members of the town’s fifty-three-member police force were Black (Nobles and Bosman 2014). The national dialogue shifted during the next few weeks, with some commentators pointing to a nationwide sedimentation of racial inequality and identifying redlining in Ferguson as a cause of the unbalanced racial composition in the community, in local political establishments, and in the police force (Bouie 2014). Redlining is the practice of routinely refusing mortgages for households and businesses located in predominately minority communities, while sedimentation of racial inequality describes the intergenerational impact of both practical and legalized racism that limits the abilities of Black people to accumulate wealth.

Ferguson’s racial imbalance may explain in part why, even though in 2010 only about 63 percent of its population was Black, in 2013 Black people were detained in 86 percent of stops, 92 percent of searches, and 93 percent of arrests (Missouri Attorney General’s Office 2014). In addition, de facto segregation in Ferguson’s schools, a race-based wealth gap, urban sprawl, and a Black unemployment rate three times that of the White unemployment rate worsened existing racial tensions in Ferguson while also reflecting nationwide racial inequalities (Bouie 2014).

This situation has not much changed in the United States. After Michael Brown, dozens of unarmed Black people have been shot and killed by police. Studies find no change to the racial disparity in the use of deadly force by police (Belli 2020). Do you think that racial tension can be reduced by stopping police action against racial minorities? What types of policies and practices are important to reduce racial tension? Who are responsible? Why?

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Sociology 3e

- Publication date: Jun 3, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/11-3-prejudice-discrimination-and-racism

© Jan 18, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Discrimination

Discrimination is prohibited by six of the core international human rights documents. The vast majority of the world’s states have constitutional or statutory provisions outlawing discrimination (Osin and Porat 2005). And most philosophical, political, and legal discussions of discrimination proceed on the premise that discrimination is morally wrong and, in a wide range of cases, ought to be legally prohibited. However, co-existing with this impressive global consensus are many contested questions, suggesting that there is less agreement about discrimination than initially meets the eye. What is discrimination? Is it a conceptual truth that discrimination is wrong, or is it a substantive moral judgment? What is the relation of discrimination to oppression and exploitation? What are the categories on which acts of discrimination can be based, aside from such paradigmatic classifications as race, religion, and sex? These are some of the contested issues.

1.1 A First Approximation

1.2 the moralized concept, 2.1 direct discrimination, 2.2 indirect discrimination, 2.3 organizational, institutional, and structural discrimination, 3.1 is indirect discrimination really discrimination, 3.2 is the dispute merely terminological, 4.1 the wrongs of direct discrimination, 4.2 the wrongs of indirect discrimination, 5. which groups count, 6. what good is the concept of discrimination, 7. intersectionality, 8. religious liberty and antidiscrimination laws, 9. conclusion, legal cases and documents, other internet resources, related entries, 1. the concept of discrimination.

What is discrimination? More specifically, what does it mean to discriminate against some person or group of persons? It is best to approach this question in stages, beginning with an answer that is a first approximation and then introducing additions, qualifications, and refinements as further questions come into view.

In his review of the international treaties that outlaw discrimination, Wouter Vandenhole finds that “[t]here is no universally accepted definition of discrimination” (2005: 33). In fact, the core human rights documents fail to define discrimination at all, simply providing non-exhaustive lists of the grounds on which discrimination is to be prohibited. Thus, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights declares that “the law shall prohibit any discrimination and guarantee to all persons equal and effective protection against discrimination on any ground such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status” (Article 26). And the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights declares, “The enjoyment of the rights and freedoms set forth in this Convention shall be secured without discrimination on any ground such as sex, race, color, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, association with a national minority, property, birth or other status” (Article 14). Left unaddressed is the question of what discrimination itself is.

Standard accounts hold that discrimination consists of actions, practices, or policies that are—in some appropriate sense—based on the (perceived) social group to which those discriminated against belong and that the relevant groups must be socially salient in that they structure interaction in important social contexts (cf. Lippert-Rasmussen 2006: 169, and Holroyd 2018: 384). Thus, groups based on race, religion and gender qualify as potential grounds of discrimination in any modern society, but groups based on the length of a person’s toenails would typically not qualify. However, Eidelson has challenged the social salience requirement (2015: 28–30), and a sound understanding of what makes discrimination wrongful might depend on how the challenge is resolved. Eidelson’s view is examined in section 4.1 below. In the meantime, the analysis of discrimination presented here will proceed on the basis of the social salience requirement.

Discrimination against persons, then, is necessarily oriented toward them based on their membership in a certain type of social group. But it is also necessary that the discriminatory conduct impose some kind of disadvantage, harm, or wrong on the persons at whom it is directed. In this connection, consider the landmark opinion of the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education, holding that de jure racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional. The Court writes, “Segregation with the sanction of law … has a tendency to [retard] the educational and mental development of negro children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would receive in a racial[ly] integrated school system” (1954: 495). Thus, the court rules that segregation amounts to illegal discrimination against black children because it imposes on them educational and psychological disadvantages.

Additionally, as Brown makes clear, the disadvantage imposed by discrimination is to be determined relative to some appropriate comparison social group. This essential reference to a comparison group explains why duties of non-discrimination are “duties to treat people in certain ways defined by reference to the way that others are treated” (Gardner 1998: 355). Typically, the relevant comparison group is part of the same society as the disadvantaged group, or at least it is governed by the same overarching political structure. In Brown , the relevant comparison group consisted of white citizens. Accordingly, it would be mistaken to think that the black citizens of Kansas who brought the lawsuit were not discriminated against because they were treated no worse than blacks in South Africa were being treated under apartheid. Blacks in South Africa were not the proper comparison class.

The appropriate comparison class is determined by normative principles. American states are obligated to provide their black citizens an education that is no worse than what they provide to their white citizens; any comparison with the citizens or subjects of other countries is beside the point. It should also be noted that, whether or not American states have an obligation to provide an education to any of their citizens, if such states provide an education to their white citizens, then it is discriminatory for the states to fail to provide an equally good education to their black citizens. And if states do have an obligation to provide an education to all their citizens, then giving an education to whites but not blacks would constitute a double-wrong against blacks: the wrong of discrimination, which depends on how blacks are treated in comparison to whites, and the wrong of denying blacks an education, which does not depend on how whites are treated.

Discrimination is necessarily comparative, and the Brown case seems to suggest that what counts in the comparison is not how well or poorly a person (or group) is treated on some absolute scale, but rather how well she is treated relative to some other person. But an important element of the court’s reasoning in Brown suggests that the disadvantage or wrong imposed by a discriminatory act can encompass more than the harmful downstream causal consequences of the act. Thus, the Court famously writes, “Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal” (1954: 495). The Court can be construed as saying that, apart from the harmful educational and psychological consequences for black children, the Jim Crow segregation of public schools stamps those children with a badge of inferiority and thereby treats them unfavorably in comparison to white children.

It is important to recognize that discrimination, in the morally and socially relevant sense, is not simply differential treatment. Differential treatment is symmetrical: if blacks are treated differently from whites, then whites must be treated differently from blacks. But it is implausible to hold that Jim Crow and South Africa’s apartheid system discriminated against whites. The system arguably held back economic progress for everyone in the South, but that point is quite different from the implausible claim that everyone was a victim of discrimination. Accordingly, it is better to think of discrimination in terms of disadvantageous treatment rather than simply differential treatment. Discrimination imposes a disadvantage on certain persons relative to others, and those who are treated more favorably are not to be seen as victims of discrimination.

An act can both be discriminatory and, simultaneously, confer an absolute benefit on those discriminated against, because the conferral of the benefit might be combined with conferring a greater benefit on the members of the appropriate comparison group. In such a case, the advantage of receiving an absolute benefit is, at the same time, a relative disadvantage or deprivation. For example, consider the admissions policy of Harvard University in the early twentieth century, when the university had a quota on the number of Jewish students. Harvard was guilty of discriminating against all Jewish applicants on account of their religion. Yet, the university still offered the applicants something of substantial value, viz., the opportunity to compete successfully for admission. What made the university’s offer of this opportunity discriminatory was that the quota placed (potential and actual) Jewish applicants at a disadvantage, due to their religion, relative to Christian ones.

One might think that it downplays the harm done by discrimination to say that the disadvantage it imposes only need be a relative disadvantage. However, the Brown case shows how the imposition of even a “merely” relative disadvantage can have extremely bad and unjust consequences for persons, especially when the relevant comparison class consists of one’s fellow citizens. Disadvantages relative to fellow citizens, when those disadvantages are severe and concern important goods such as education and social status, can make persons vulnerable to domination and oppression at the hands of their fellow citizens (Anderson 1999). The domination and oppression of American blacks by their fellow citizens under Jim Crow was made easier by the relative disadvantage imposed on blacks when it came to education. Norwegians might have had an even better education than southern whites, but Norwegians posed little threat of domination to southern whites or blacks, because they lived under an entirely separate political structure, having minimal relations to American citizens. Matters are different in today’s globalized world, where an individual’s disadvantage in access to education relative to persons who live in other countries could pose a threat of oppression. Accordingly, one must seriously consider the possibility that children from poor countries are being discriminated against when they are unable to obtain the education routinely available to children in affluent societies.

The relative nature of the disadvantage that discrimination imposes explains the close connection between discrimination and inequality. A relative disadvantage necessarily involves an inequality with respect to persons in the comparison class. Accordingly, antidiscrimination norms prohibit certain sorts of inequalities between persons in the relevant comparison classes (Shin 2009). For example, the U.S. Civil Rights Act of 1866 requires that all citizens “shall have the same right, in every State and Territory in the United States, to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence, to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property, and to full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property, as is enjoyed by white citizens” (Civil Rights Act 1866). And the international convention targeting discrimination against women condemns “any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women … on a basis of equality of men and women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms” (CEDAW, Article 1).

To review: as a reasonable first approximation, we can say that discrimination consists of acts, practices, or policies that impose a relative disadvantage on persons based on their membership in a salient social group. But notice that this account does not make discrimination morally wrong as a conceptual matter. The imposition of a relative disadvantage might, or might not, be wrongful. In the next section, we will see how the idea of moral wrongfulness can be introduced to form a moralized concept of discrimination.

In recent years, some thinkers have rejected the view that discrimination is an essentially comparative concept that looks to how certain persons are treated relative to others. For example, Réaume argues against the view by invoking the “leveling-down objection.” She points out that, if there is an inequality in the distribution of some benefit between two persons or groups, then we need to ask “whether leveling up or leveling down are, other things held constant, regarded as equally attractive solutions” (2013: 8). The comparative view seems to entail that the two solutions are equally attractive, but, Réaume points out, plaintiffs in discrimination cases who are demanding equal treatment “rarely put their claim this way” (8) and would not be satisfied with the leveling-down solution: “they ask to vote as well, not that voting be abolished, or that a pension scheme include them, not that it be repealed.” Réaume continues, “To level down would deprive everyone of something all are properly entitled to, and thus exacerbate rather than solve the problem” (11).

Nonetheless, the leveling-down objection is problematic. That plaintiffs in discrimination cases do not ask that voting be abolished only shows that they know that they would be better off with everyone having the right to vote than with no one having it. Moreover, although leveling down would, in typical cases, deprive everyone of something to which all are entitled, it does not follow that leveling down would constitute discrimination. The universal denial of the franchise would be a wrong, but not the wrong of discrimination. Denial of the franchise amounts to discrimination only when it is selectively directed at some salient group within the adult population. Accordingly, Lippert-Rasmussen seems to be right when he explains, “Unlike other prima facie morally wrong acts, such as lying, hurting, or manipulating, one cannot discriminate against some unless there are others who receive (or who would receive) better treatment at one’s hands …. I can rebut an accusation of having discriminated against someone by saying that I would have treated anyone else at least as badly in that situation” (2014: 16).

The concept of discrimination is inherently normative to the extent that the idea of disadvantage is a normative one. But it does not follow from this point that discrimination is, by definition, morally wrong. At the same time, many—or even most—uses of the term ‘discrimination’ in contemporary political and legal discussions do employ the term in a moralized sense. Wasserman is using this moralized sense, when he writes that “[t]o claim that someone discriminates is … to challenge her for justification; to call discrimination ‘wrongful’ is merely to add emphasis to a morally-laden term” (1998: 805). We can, in fact, distinguish a moralized from a non-moralized concept of discrimination. The moralized concept picks out acts, practices or policies insofar as they wrongfully impose a relative disadvantage on persons based on their membership in a salient social group of a suitable sort. The non-moralized concept simply dispenses with the adverb ‘wrongfully’.

Accordingly, the sentence ‘Discrimination is wrong’ can be either a tautology (if ‘discrimination’ is used in its moralized sense) or a substantive moral judgment (if ‘discrimination’ is used in its non- moralized sense). And if one wanted to condemn as wrong a certain act or practice, then one could call it ‘discrimination’ (in the moralized sense) and leave it at that, or one could call it ‘discrimination’ (in the non-moralized sense) and then add that it was wrongful. In contexts where the justifiability of an act or practice is under discussion and disagreement, the moralized concept of discrimination is typically the key one used, and the disagreement is over whether the concept applies to the act. Because of its role in such discussion and disagreement, the remainder of this article will be concerned with the moralized concept of discrimination, unless it is explicitly indicated otherwise.

There is an additional point that needs to be made in connection with the wrongfulness of discrimination in its moralized sense. It is not simply that such discrimination is wrongful as a conceptual matter. The wrongfulness of the discrimination is tied to the fact that the discriminatory act is based on the victim’s membership in a salient social group. An act that imposes a relative disadvantage or deprivation might be wrong for a variety of reasons; for example, the act might violate a promise that the agent has made. The act counts as discrimination, though, only insofar as its wrongfulness derives from a connection of the act to the membership in a certain group(s) of the person detrimentally affected by the act. Accordingly, we can refine the first-approximation account of discrimination and say that the moralized concept of discrimination is properly applied to acts, practices or policies that meet two conditions: a) they wrongfully impose a relative disadvantage or deprivation on persons based on their membership in some salient social group, and b) the wrongfulness rests (in part) on the fact that the imposition of the disadvantage is on account of the group membership of the victims.

2. Types of Discrimination (in its Moralized Sense)

Legal thinkers and legal systems have distinguished among a bewildering array of types of discrimination: direct and indirect, disparate treatment and disparate impact, intentional and institutional, individual and structural. It is not easy to make sense of the morass of categories and distinctions. The best place to start is with direct discrimination.

Consider the following, clear instance of direct discrimination. In 2002, several men of Roma descent entered a bar in a Romanian town and were refused service. The bar employee explained his conduct by pointing out to them a sign saying, “We do not serve Roma.” The Romanian tribunal deciding the case ruled that the Roma men had been the victims of unlawful direct discrimination (Schiek, Waddington, & Bell 2007: 185). The bar’s policy, as formulated in its sign, explicitly and intentionally picked out the Roma qua Roma for disadvantageous treatment. It was those two features—explicitness and intention—that made the Roma case a paradigmatic example of direct discrimination. Such examples of discrimination are cases in which the agent acts with the aim of imposing a disadvantage on persons for being members of some salient social group. In the Roma case, the bartender and bar owner aimed to exclude Roma for being Roma, and so both the owner’s policy and the bartender’s maxim of action explicitly referred to the exclusion of Roma. It is clear that the policy of the bar was wrong, but the question of what makes the policy and other instances direct discrimination wrongful will be put on hold until section 4.1 below.

In some cases, a discriminator will adopt a policy that, on its face, makes no explicit reference to the group that he or she aims to disadvantage. Instead, the policy employs some facially-neutral surrogate that, when applied, accomplishes the discriminator’s hidden aim. For example, during the Jim Crow era, southern states used literacy tests for the purpose of excluding African-Americans from the franchise. Because African-Americans were denied adequate educational opportunities and because the tests were applied in a racially-biased manner, virtually all of the persons disqualified by the tests were African-Americans, and, in any given jurisdiction, the vast majority of African-American adults seeking to vote were disqualified. The point of the literacy tests was precisely such racial exclusion, even though the testing policy made no explicit reference to race.

Notwithstanding the absence of an explicit reference to race in the literacy tests themselves, their use was a case of direct discrimination. The reason is that the persons who formulated, voted for, and implemented the tests acted on maxims that did make explicit reference to race. Their maxim was something along the lines of: ‘In order to exclude African-Americans from the franchise and do so in a way that appears consistent with the U.S. Constitution, I will favor a legal policy that is racially-neutral on its face but in practice excludes most African-Americans and leaves whites unaffected.’ As with the Roma case, there were agents whose aim was to disadvantage persons for belonging to a certain social group.

However, it is too simple to say that direct discrimination simply is intentional discrimination. Lippert-Rasmussen rightly points out that there can be cases of direct discrimination not involving the intention to disadvantage anyone on account of her group membership (2014: 59–60). A disadvantage might, instead, be imposed as a result of a general indifference toward the interests and rights of the members of a certain group. Thus, an employer might use hiring criteria that unfairly disadvantages women, not because the employer intends to disadvantage women, but because the criteria are easy to use and he simply does not care that women are unfairly disadvantaged as a result. Such instances of discrimination might not have the paradigmatic status that an example like the Roma case has, but they should be counted as forms of direct discrimination, because the disadvantageous treatment derives from an objectionable mental state of the agent. The same goes for disadvantageous treatment that is the product of bias against a certain group, even when the bias does not involve an intention to treat the group disadvantageously. A paternalistic employer might intend to help women by hiring them only for certain jobs in his company, but, if the employer is motivated by unwarranted views about the capabilities of women, he is guilty of direct discrimination.

Acts of direct discrimination can be unconscious in that the agent is unaware of the discriminatory motive behind them. It is plausible to think that in many societies, unconscious prejudice is a factor in a significant range of discriminatory behavior, and a viable understanding of the concept of discrimination must be able to accommodate the possibility. In fact, there is growing evidence that unconscious discrimination exists (Jost et al. 2009; Payne and Cameron 2010; and Brownstein and Saul 2016). And as Wax has noted, even the intention to disadvantage persons on account of their group affiliation can be unconscious (2008: 983).

Under many legal systems, an act that imposes a disproportionate disadvantage on the members of a certain group can count as discriminatory, even though the agent has no intention to disadvantage the members of the group and no other objectionable mental state, such as indifference or bias, motivating the act. This form of discriminatory conduct is called “indirect discrimination” or, in the language of American doctrine, “disparate impact” discrimination. Thus, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) has held that “[w]hen a general policy or measure has disproportionately prejudicial effects on a particular group, it is not excluded that this may be considered as discriminatory notwithstanding that it is not specifically aimed or directed at that group” (Shanaghan v. U.K. 2001: para. 129).

It should be noted that the ECHR says that policies with disproportionate effects may be discriminatory even if that is not the aim of the policies. So what criterion determines when a policy with disproportionately worse effects on a certain group actually counts as indirect discrimination? There is no agreed upon answer.

The ECHR has laid down the following criterion: a policy with disproportionate effects counts as indirect discrimination “if it does not pursue a legitimate aim or if there is not a reasonable relation of proportionality between means and aim” (Abdulaziz et al. v. U.K., 1985: para. 721). The Human Rights Committee of the United Nations has judged that a policy with disproportionate effects is discriminatory “if it is not based on objective and reasonable criteria” (Moucheboeuf 2006: 100). Under the British Race Relations Act, such a policy is discriminatory if the policymaker “cannot show [the policy] to be justifiable irrespective of the … race … of the person to whom it is applied” (Osin and Porat 2005: 900). And in its interpretation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that, in judging whether the employment policies of private businesses are (indirectly) discriminatory, “[i]f an employment practice which operates to exclude Negroes cannot be shown to be related to job performance, the practice is prohibited” ( Griggs v. Duke Power 1971: 431). Despite the differences, these criteria have a common thought behind them: a disproportionately disadvantageous impact on the members of certain salient social groups must not be written off as morally or legally irrelevant or dismissed as mere accident, but rather stands in need of justification. In other words, the impact must not be treated as wholly inconsequential, as if it were equivalent, for example, to a disproportionate impact on persons with long toe nails. Toe-nail group impact would require no justification, because it would simply be an accidental and morally inconsequential feature of the act, at least in all actual societies. In contrast, the thought behind the idea of indirect discrimination is that, if an act has a disproportionately disadvantageous impact on persons belonging to certain types of salient social groups, then the act is morally wrong and prohibited by anti-discrimination law unless it can meet some suitable standard of justification.

To illustrate the idea of indirect discrimination, we can turn to the U.S. Supreme Court case, Griggs v. Duke Power (1971). A company in North Carolina used a written test to determine promotions. The use of the test had the result that almost all black employees failed to qualify for the promotions. The company was not accused of direct discrimination, i.e., there was no claim that a racially discriminatory attitude was behind the decision of the company to use the written test. But the court found that the test did not measure skills essential for the jobs in question and that the state of North Carolina had a long history of deliberately discriminating against blacks by, among other things, providing grossly inferior education to them. The state had only very recently begun to rectify that situation. In ruling for the black plaintiffs, the court reasoned that the policy of using the test was racially discriminatory, because of the test’s disproportionate racial impact combined with the fact that it was not necessary to use the test to determine who was best qualified for promotion.

In many cases, acts of discrimination are attributed to collective agents, rather than to natural persons acting in their individual capacities. Accordingly, corporations, universities, government agencies, religious bodies, and other collective agents can act in discriminatory ways. This kind of discrimination can be called “organizational,” and it cuts across the direct-indirect distinction. Confusion sometimes arises when it is mistakenly believed that organizations cannot have intentions and that only indirect discrimination is possible for them. As collective agents, organizations do have intentions, and those intentions are a function of who the officially authorized agents of the institution are and what they are trying to do when they act as their official powers enable them. Suppose that the Board of Trustees of a university votes to adopt an admissions policy that (implicitly or explicitly) excludes Jews, and the trustees vote that way precisely because they believe that Jews are inherently more dishonest and greedy than other people. In such a cases, the university is deliberately excluding Jews and is guilty of direct discrimination. Individual trustees acting in their private capacity might engage in other forms of discriminatory conduct; for example, they might refuse to join clubs that have Jewish members. Such a refusal would not count as organizational discrimination. But any discriminatory acts attributable to individual board members in virtue of some official power that they hold would count as organizational discrimination.

Structural discrimination—sometimes called “institutional” (Ture and Hamilton 1992 [1967]: 4)—should be distinguished from organizational: the structural form concerns the rules that constitute and regulate the major sectors of life such as family relations, property ownership and exchange, political powers and responsibilities, and so on (Pogge 2008: 37). It is true that when such rules are discriminatory, they are often—though not always—the deliberate product of some collective or individual agent, such as a legislative body or executive official. In such cases, the agents are guilty of direct discrimination. But the idea of structural discrimination is an effort to capture a wrong distinct from direct discrimination. Thus, Fred Pincus writes that “[t]he key element in structural discrimination is not the intent but the effect of keeping minority groups in a subordinate position” (1994: 84). What Pincus and others have in mind can be explained in the following way.

When the rules of a society’s major institutions reliably produce disproportionately disadvantageous outcomes for the members of certain salient social groups and the production of such outcomes is unjust, then there is structural discrimination against the members of the groups in question, apart from any direct discrimination in which the collective or individual agents of the society might engage. This account does not mean that, empirically speaking, structural discrimination stands free of direct discrimination. It is highly unlikely that the reliable production of unjust and disproportionately disadvantageous effects would be a chance occurrence. Rather, it is (almost) always the case that, at some point(s) in the history of a society in which there is structural discrimination, important collective agents, such as governmental ones, intentionally created rules with the aim of disadvantaging the members of the groups in question. It is also likely that some collective and individual agents continue to engage in direct discrimination in such a society. But by invoking the idea of structural discrimination and attributing the discrimination to the rules of a society’s major institutions, we are pointing to a form of discrimination that is conceptually distinct from the direct discrimination engaged in by collective or individual agents. Thus understood, structural discrimination is, as a conceptual matter, necessarily indirect, although, as an empirical matter, direct discrimination is (almost) always part of the story of how structural discrimination came to be and continues to exist.

Also note that the idea of structural discrimination does not presuppose that, whenever the rules of society’s major institutions consistently produce disproportionately disadvantageous results for a salient group such as women or racial minorities, structural discrimination thereby exists. Because our concern is with the moralized concept of discrimination, one might think that disproportionate outcomes, by themselves, entail that an injustice has been done to the members of the salient group in question and that structural discrimination thereby exists against the group. However, on a moralized concept of structural discrimination, the injustice condition is distinct from the disproportionate outcome condition. Whether a disproportionate outcome is sufficient for concluding that there is an injustice against the members of the group is a substantive moral question. Some thinkers might claim that the answer is affirmative, and such a claim is consistent with the moralized concept of structural discrimination. However, the claim is not presupposed by the moralized concept, which incorporates only the conceptual thesis that a pattern of disproportionate disadvantage falling on the members of certain salient groups does not count as structural discrimination unless the pattern violates sound principles of distributive justice.

3. Challenging the Concept of Indirect Discrimination

The distinction between direct and indirect discrimination plays a central role in contemporary thinking about discrimination. However, some philosophers hold that talking about indirect discrimination is confused and misguided. For these philosophers, direct discrimination is the only genuine form of discrimination. Examining their challenge to the very concept of indirect discrimination is crucial in developing a philosophical account of what discrimination is.

Young argues that the concept of discrimination should be limited to “intentional and explicitly formulated policies of exclusion or preference.” She holds that conceiving of discrimination in terms of the consequences or impact of an act, rather than in terms of its intent, “confuses issues” by conflating discrimination with oppression. Discrimination is a matter of the intentional conduct of particular agents. Oppression is a matter of the outcomes routinely generated by “the structural and institutional framework” of society (1990: 196).

Cavanagh holds a position similar to Young’s, writing that persons “who are concerned primarily with how things like race and sex show up in the overall distributions [of jobs] have no business saying that their position has anything to do with discrimination. It is not discrimination they object to, but its effects; and these effects can equally be brought about by other causes” (2002: 199). On Cavanagh’s view, then, if one finds it inherently objectionable for political officeholders to be predominantly male, then one can sensibly charge that such a disproportion is unjust but cannot coherently claim that it is, in itself, discriminatory.

Along the same lines, Eidelson contends that “‘indirect’ discrimination is not usefully thought of as a distinct form of discrimination at all, except as a piece of legal jargon” (2015: 19). He writes, “Precisely because the connotation of ‘discrimination’ as an act … in which an agent is sensitive to some feature of the discriminatee, and engages in some manner of differential treatment, is inescapable, describing indirect discrimination as discrimination is a serious obstacle to clear communication” (56).

The arguments of Cavanagh, Eidelson and Young raise a question that is not easy to answer, viz., why can indirect and direct discrimination be legitimately considered as two subcategories of one and the same concept? In other words, what do the two supposed forms of discrimination really have in common that make them forms of the same type of moral wrong? Direct discrimination is essentially a matter of the reasons or motives that guide the act or policy of a particular agent, while indirect discrimination is not about such reasons or motives. Even conceding that acts or policies of each type can be wrong, it is unclear that the two types are each species of one and the same kind of moral wrong, i.e., the wrong of discrimination. And if cases of direct discrimination are paradigmatic examples of discrimination, then a serious question arises as to whether the concept of discrimination properly applies to the policies, rules, and acts that are characterized as “indirect” discrimination.

Moreover, there is a crucial ambiguity in how discrimination is understood that lends itself to conflating direct discrimination with the phenomena picked out by ‘indirect discrimination’. Direct discrimination involves the imposition of disadvantages “based on” or “on account of” or “because of” membership in some salient social group. Yet, these phrases can refer either to a) the reasons that guide the acts of agents or to b) factors that do not guide agents but do help explain why the disadvantageous outcomes of certain acts and policies fall disproportionately on certain salient groups (Cf. Shin 2010). In the Roma case, the disadvantage was “because of” ethnicity in the former sense: the ethnicity of the Roma was a consideration that guided the acts of the bar owner and bartender. In the Griggs case, the disadvantage was “because of race” in the latter sense: race did not guide the acts of the company but neither was it an accident that the disadvantages of the written test fell disproportionately on blacks. Rather, race, in conjunction with the historical facts about North Carolina’s educational policies, explained why the disadvantage fell disproportionately on black employees.

The thought that the policy of the company in Griggs is a kind of discrimination, viz., indirect discrimination, seems to trade on the ambiguity in the meanings of the locutions ‘based on’, ‘because of’, ‘on account of’, and so on. The state of North Carolina’s policy of racial segregation in education imposed disadvantages based on/because of/on account of race, in one sense of those terms. The company’s policy of using a written test imposed disadvantages based on/because of/on account of race, in a different sense. Even conceding that both the state and the company wronged blacks on the basis of their race, it appears that the two cases present two different kinds of wrong.

Nonetheless, the idea of indirect discrimination can help to highlight how the wrongful harms of direct discrimination are capable of ramifying via acts and policies that are not directly discriminatory and would be entirely innocent but for the link between them and acts of direct discrimination. In the Griggs case, direct discrimination had harmed blacks by putting them at an educational disadvantage. Even if the direct discrimination had ceased at some prior point, the policy of the company enabled the educational disadvantage to branch into an employment disadvantage, thereby amplifying and perpetuating the wrongful harms of the original direct discrimination. The language of indirect discrimination can spotlight the link between the two forms of disadvantage and capture the idea that the wrongful harms of direct discrimination should not be allowed to extend willy-nilly across time and domains of life via otherwise innocent acts.

However, it is also true that the idea of indirect discrimination is typically understood in a broader way that does not require any connection to direct discrimination. Accordingly, in his discussion of how persons adhering to certain religious beliefs or practices might be put at an unjust disadvantage by an employer’s dress code, Jones writes, “Indirect discrimination law aims … to eliminate inequalities of opportunity arising from religion or belief” (170). For example, if a code excludes a form of dress that persons adhering to a particular religion regard as theologically-favored, such as head coverings or veils, then the British law of indirect discrimination requires that the company grant an exemption to those persons, unless it can show that the code is a proportionate means for achieving a legitimate aim. On Jones’s view, the law thereby counters, albeit in a limited way, an unjust burden placed on certain religious adherents and promotes equal employment opportunity.

The critics of the idea of indirect discrimination think that Jones is conflating distinct wrongs: the right of equal opportunity can be violated by discrimination, but it can also be violated by other sorts of wrongs. Even if certain dress codes violate the right and do so in a way that tracks a particular religious identity, it does not follow that the codes are cases of wrongful discrimination. But Jones can respond that, as long as the wrongful treatment tracks salient social categories, differentially disadvantaging persons belonging to such a category, then characterizing the treatment as discrimination is in order.

Still, critics will contend that the concept of indirect discrimination is problematic, because its use mistakenly presupposes that the wrongfulness of discrimination can lie ultimately in its effects on social groups. Certainly, bad effects can be brought about by discriminatory processes, but critics argue that the wrongfulness lies in what brings about the effects, i.e., in the unfairness or injustice of those acts or policies that generate the effects, and does not reside in the effects themselves. Addressing this argument requires a closer examination of why discrimination is wrong, the topic of section 4. Before turning to that section, it would be helpful to address a suspicion that might arise in the course of pondering whether indirect discrimination really is a form of discrimination.

One might suspect that any disagreement over whether indirect discrimination is really a form of discrimination is only a terminological one, devoid of any philosophical substance and capable of being adequately settled simply by the speaker stipulating how she is using the term ‘discrimination’ (Cavanagh 2002: 199). One side in the disagreement could, then, stipulate that, as it is using the term, ‘discrimination’ applies only to direct discrimination, and the other side could stipulate that ‘discrimination’, as it is using the term, applies to direct and indirect discrimination alike. However, the choice of terminology is not always philosophically innocent or unproblematic. A poor choice of terminology can lead to conceptual confusions and fallacious inferences. Cavanagh argues that precisely these sorts of infelicities are fostered when ‘discrimination’ is used to refer to a wrong that essentially depends on certain effects being visited upon the members of a social group (2002: 199). Moreover, the critics and the defenders of the term ‘indirect discrimination’ presumably agree with one another that the concept of discrimination possesses a determinate meaning that either admits, or does not admit, of an indirect form of discrimination. So it seems that the disagreement over indirect discrimination has philosophical significance.

The possibility should be acknowledged that the concept of discrimination is insufficiently determinate to dictate an answer to the question of whether there can be an indirect form of discrimination. In that case, any disagreement over the possibility of such discrimination would be devoid of philosophical substance and should be settled by speaker stipulation. However, it would be hasty to arrive at the conclusion that there is no answer before a thorough examination of the concept of discrimination is completed and some judgment is made about what the best account is of the concept. And a thorough examination must take up the question of why discrimination is wrong.

4. Why Is Discrimination Wrong?

In examining the question of why discrimination is wrongful, let us begin with direct discrimination and then turn to the indirect form. This approach will help shed some light on whether the wrongs involved in the two forms are sufficiently analogous to consider them as two types of one and the same kind of wrong.

Specifying why direct discrimination is wrongful has proved to be a surprisingly controversial and difficult task. There is general agreement that the wrong concerns the kind of reason or motive that guides the action of the agent of discrimination: the agent is acting on a reason or motive that is in some way illegitimate or morally tainted. But there are more than a half-dozen distinct views about what the best principle is for drawing the distinction between acts of direct discrimination (in the moralized sense) and those acts that are not wrongful even though the agent takes account of another’s social group membership.

One popular view is that direct discrimination is wrong because the discriminator treats persons on the basis of traits that are immutable and not under the control of the individual possessing them. Thus, Kahlenberg asserts that racial discrimination is unjust because race is such an immutable trait (1996: 54–55). And discrimination based on many forms of disability would seem to fit this view. But Boxill rejects the view, arguing that there are instances in which it is justifiable to treat persons based on features that are beyond their control (1992: 12–17). Denying blind people a driver’s license is not an injustice to them. Moreover, Boxill notes that, if scientists developed a drug that could change a person’s skin color, it would still be unjust to discriminate against people because of their color (1992: 16). Additionally, a paradigmatic ground of discrimination, a person’s religion, is not an immutable trait, nor are some forms of disability. Thus, there are serious problems with the popular view that direct discrimination is wrong due to the immutable nature of the traits on the basis of which the discriminator treats the persons whom he wrongs.

A second view holds that direct discrimination is wrong because it treats persons on the basis of inaccurate stereotypes. When the state of Virginia defended the male-only admissions policy of the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), it introduced expert testimony that there was a strong correlation between sex and the capacity to benefit from the highly disciplined and competitive educational atmosphere of the school: those who benefited from such an atmosphere were, for the most part, men, while women had a strong tendency to thrive in a quite different, cooperative educational environment. This defense involved the premise that the school’s admissions policy was not discriminatory because the policy relied on accurate generalizations about men and women. And in its ruling against VMI, the Supreme Court held that a public policy “must not rely on overbroad generalizations about the different talents, capacities, or preferences of males and females” ( U.S. v. Virginia 1996: 533). But the Court went on to argue that “generalizations about ‘the way women are’, estimates of what is appropriate for most women , no longer justify denying opportunity to women whose talent and capacity place them outside the average description” (550; ital. in original).

The Court’s reasoning implies that, even if gender were a very good predictor of the qualities needed to benefit from and be successful at the school, VMI’s admissions policy would still be discriminatory (Schauer 2003: 137–141). Accordingly, on the Court’s view, direct discrimination based on largely accurate gender generalizations can still be wrongful. For example, consider a fire department whose policy is to reject all women applicants for the job of fire fighter, on the grounds that the vast majority of persons having the requisite physical strength for the job are men and that the policy saves the department the time and expense of testing persons unlikely to meet the requirement. Even if the gender generalization underlying the policy is accurate, it is clear that the policy amounts to wrongful discrimination against women, depriving them of their right to equal employment opportunity. Thus, the wrongfulness cannot be explained simply by saying that the generalization is inaccurate.

A third view is that direct discrimination is wrong because it is an arbitrary or irrational way to treat persons. In other words, direct discrimination imposes a disadvantage on a person for a reason that is not a good one, viz., that the person is a member of a certain salient social group. Accordingly, Cotter argues that such discrimination treats people unequally “without rational justification” (2006: 10). Kekes expresses a similar view in condemning race-based affirmative action as “arbitrary” (1995: 200), and, in the same vein, Flew argues that racism is unjust because it treats persons on the basis of traits that “are strictly superficial and properly irrelevant to all, or almost all, questions of social status and employability” (1990: 63–64).

However, many thinkers reject this third view of the wrongness of direct discrimination. Gardner argues that there is no “across-the-board-duty to be rational, so our irrationality as such wrongs no one.” Additionally, Gardner contends that “there patently can be reasons, under some conditions, to discriminate on grounds of race or sex,” even though the conduct in question is wrongful (1998: 168). For example, a restaurant owner might rationally refuse to serve blacks if most of his customers are white racists who would stop patronizing the establishment if blacks were served (1998: 168 and 182). The owner’s actions would be wrong and would amount to a rational form of discrimination. Additionally, Wasserstrom argues that the principle that persons ought not to be treated on the basis of morally arbitrary features cannot grasp the fundamental wrong of direct racial discrimination, because the principle is “too contextually isolated” from the actual features of a society in which many people have racist attitudes (1995: 161). For Wasserstrom, the wrong of racial discrimination cannot be separated from the fact that such discrimination manifests an attitude that the members of certain races are intellectually and morally inferior to the rest of the population.

A fourth view is that direct discrimination is wrong because it fails to treat individuals based on their merits. Thus, Hook argues that hiring decisions based on race, sex, religion and other social categories are wrong because such decisions should be based on who “is best qualified for the post” (1995: 146). In a similar vein, Goldman argues that discriminatory practices are wrong because “the most competent individuals have prima facie rights to positions” (1979: 34).

Opponents of this merit-based view note that it is often highly contestable who the “best qualified” really is, because the criteria determining qualifications are typically vague and do not come with weights attached to them (Wasserman 1998: 807). Additionally, Cavanagh suggests that “hiring on merit has more to do with efficiency than fairness” (2002: 20). Cavanagh also notes that a merit principle cannot explain what is distinctively wrong about an employer who discriminates against blacks because the employer thinks that they are morally or intellectually inferior. The merit approach “makes [the employer’s] behavior look the same as any other way of treating people … non-meritocratically” (2002: 24–25).

A fifth view, defended by Arneson and Lippert-Rasmussen, explains the wrongfulness of discrimination in terms of a certain consequentialist moral theory. The theory rests on the principle that every action ought to maximize overall moral value and incorporates the idea that benefits accruing to persons who are at a lower level of well-being count more toward overall moral value than benefits to those at a higher level. Additionally, the view holds that benefits to persons who are more deserving of them count more than benefits to those who are less deserving (Arneson 1999: 239–40 and Lippert-Rasmussen 2014: 165–83). This approach holds that discrimination is wrong because it violates a rule that would be part of the social morality that maximizes overall moral value. Thus, Arneson writes that his view “can possibly defend nondiscrimination and equal opportunity norms as part of the best consequentialist public morality” (2013: 99). However, for many thinkers, the view will fail to adequately capture a key aspect of discrimination, viz., that discrimination is not simply wrong but that it is a wrong to the persons who are discriminated against . One might argue in defense of Arneson that those who are victimized by discrimination can claim that they deserve the opportunity that is denied them, but philosophers like Cavanagh, who object to the merit approach, will have the same objections to such a defense (Cavanagh 2002: 20 and 24–25).

A sixth view, developed by Moreau, regards direct discrimination as wrong because it violates the equal entitlement each person has to freedom. In particular, she contends that “the interest that is injured by discrimination is our interest in … deliberative freedoms: that is, freedoms to have our decisions about how to live insulated from the effects of normatively extraneous features of us, such as our skin color or gender” (2010: 147). Normatively extraneous features are “traits that we believe persons should not have to factor into their deliberations … as costs .” For example, “people should not be constrained by the social costs of being one race rather than another when they deliberate about such questions as what job to take or where to live” (2010: 149).

Yet, it is unclear that Moreau’s account gets to the bottom of what is wrong with discrimination. One might object, following the criticisms leveled by Wasserstrom and Cavanagh at the arbitrariness and merit accounts, respectively, that the idea of a normatively extraneous feature is too abstract to capture what makes racial discrimination a paradigmatic form of direct discrimination. There are reasons that justify our belief “that persons should not have to factor [race] into their deliberations … as costs ,” and those reasons seem to be connected to the idea that racial discrimination treats persons of a certain race as having a diminished or degraded moral status as compared to individuals belonging to other races. The wrong of racial and other forms of discrimination seems better illuminated by understanding it in terms of such degraded status than in terms of the idea of normatively extraneous features.

A seventh view, developed by Hellman, holds that “discrimination is wrong because it is demeaning” (2018: 99). On her account, an act that is demeaning in the relevant way is one that “expresses that a person or group is of lower [moral] status” and is performed by an agent who has “sufficient social power for the expression to have force” (2018: 102). For example, it is demeaning, she argues, for an employer to require female employees to wear cosmetics because such a requirement “conveys the idea that a woman’s body is for adornment and enjoyment by others” (2008: 42). Shin proposes a similar account in his discussion of equal protection, arguing that “to characterize an action as unequal treatment is to register a certain objection as to what, in view of its rationale, the action expresses” (2009: 170). Offending actions are ones that treat a person “as though that individual belonged to some class of individuals that was less entitled to right treatment than anyone else” (2009:169). And this seventh view of what makes discrimination wrongful is reflected in the legal case Obergefell v. Hodges , decided by the U.S. Supreme Court and declaring unconstitutional laws prohibiting same-sex marriage. In his opinion for the Court, Justice Kennedy wrote that “the necessary consequence [of such laws] is to put the imprimatur of the State itself on an exclusion that soon demeans or stigmatizes those whose own liberty is then denied. Under the Constitution, same-sex couples seek in marriage the same legal treatment as opposite-sex couples, and it would disparage their choices and diminish their personhood to deny them this right” (2015: Slip Opinion at 19).

Closely related to Hellman’s account is an eighth view, holding that direct discrimination is wrong on account of its connection to prejudice, where prejudice is understood as an attitude that regards the members of a salient group, qua members, as not entitled to as much respect or concern as the members of other salient groups. Prejudice can involve feelings of hostility, antipathy, or indifference, as well as a belief in the inferior morals, intellect, or skills of the targeted group. Returning to the case of the Roma who were excluded by the policy of a bar, we could say that the policy was discriminatory because it was the expression of prejudice against the Roma, whereas a bar’s policy of excluding men from the women’s restroom would fail to be discriminatory because it would not be an expression of prejudice.

Ely defends a version of this eighth view, holding that discriminatory acts are those that are motivated by prejudice (1980: 153–159). Dworkin has formulated an alternative version, arguing that discriminatory acts are those that could be justified only if some prejudiced belief were correct. The absence of a “prejudice-free justification” thus makes a law or policy discriminatory (1985: 66).

The eighth view, along with the accounts of Hellman and Shin, rest on the intuitively attractive idea that the wrongfulness of direct discrimination is tied to its denial of the equal moral status of persons. The idea is at the center of Eidelson’s account, which holds that “acts of discrimination are intrinsically wrong when and because they manifest a failure to show the discriminatees the respect that is due them as persons” (2015: 7). Eidelson then disaggregates two dimensions of personhood: all persons are 1) “of [intrinsic] value and equally so” and 2) “autonomous agents” (2015: 79), shaping their own lives through their choices. Discrimination can violate either or both of these dimensions, leading Eidelson to describe his account as a “pluralistic view” (2015: 19; cf. Beeghly on “hybrid” theories, 2018: 95). Thus, a physician who refuses to treat would-be patients due to their race fails to recognize and appropriately respond to their equal intrinsic value, and a fire department that automatically rejects women who apply to be fire fighters violates the women’s autonomy by failing to make reasonable efforts to determine whether they have endeavored to develop the requisite physical strength.

Eidelson’s account explicitly dispenses with the social salience requirement, instead requiring only that the discriminator be responding to some perceived difference of whatever kind between the victim and other people. However, it is not clear that this approach can draw a viable line between wrongful acts of discrimination, on the one hand, and wrongful acts not helpfully characterized as “discrimination,” on the other. Murderers fail to respect the personhood of their victims, and most murders involve some perception of difference between the victim and others. But murders are typically regarded as acts of discrimination only when they are “hate crimes” connected to the victim’s membership in some salient social group. So Eidelson’s account seems overinclusive. Yet, Eidelson can reply that any account that incorporates the social salience requirement will be underinclusive, because it will fail to count as discrimination the actions of an employer who hires workers on the basis of hair color in a society where hair color is not socially salient (2018: 28–30).

At this point, we should step back and ask: Why do we need the (moralized) idea of discrimination in the first place? What is the value of having it? For Eidelson, its value seems to reside in picking out certain wrongs, quite apart from any connection those wrongs might, or might not, have to socially systemic injustices. But we have concepts for murder and other wrongs against personhood, and, if we abstract from socially systemic considerations, the fact that the wrongs involve distinguishing among persons does not appear to carry much moral significance in typical cases. If I steal from you rather than your neighbor because you have taken fewer precautions against theft, then I have wrongfully shown disrespect for your autonomy, but my having discriminated between you and your neighbor seems beside the point, morally speaking.