Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a narrative essay | Example & tips

How to Write a Narrative Essay | Example & Tips

Published on July 24, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

A narrative essay tells a story. In most cases, this is a story about a personal experience you had. This type of essay , along with the descriptive essay , allows you to get personal and creative, unlike most academic writing .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is a narrative essay for, choosing a topic, interactive example of a narrative essay, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about narrative essays.

When assigned a narrative essay, you might find yourself wondering: Why does my teacher want to hear this story? Topics for narrative essays can range from the important to the trivial. Usually the point is not so much the story itself, but the way you tell it.

A narrative essay is a way of testing your ability to tell a story in a clear and interesting way. You’re expected to think about where your story begins and ends, and how to convey it with eye-catching language and a satisfying pace.

These skills are quite different from those needed for formal academic writing. For instance, in a narrative essay the use of the first person (“I”) is encouraged, as is the use of figurative language, dialogue, and suspense.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Narrative essay assignments vary widely in the amount of direction you’re given about your topic. You may be assigned quite a specific topic or choice of topics to work with.

- Write a story about your first day of school.

- Write a story about your favorite holiday destination.

You may also be given prompts that leave you a much wider choice of topic.

- Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself.

- Write about an achievement you are proud of. What did you accomplish, and how?

In these cases, you might have to think harder to decide what story you want to tell. The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to talk about a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

For example, a trip where everything went according to plan makes for a less interesting story than one where something unexpected happened that you then had to respond to. Choose an experience that might surprise the reader or teach them something.

Narrative essays in college applications

When applying for college , you might be asked to write a narrative essay that expresses something about your personal qualities.

For example, this application prompt from Common App requires you to respond with a narrative essay.

In this context, choose a story that is not only interesting but also expresses the qualities the prompt is looking for—here, resilience and the ability to learn from failure—and frame the story in a way that emphasizes these qualities.

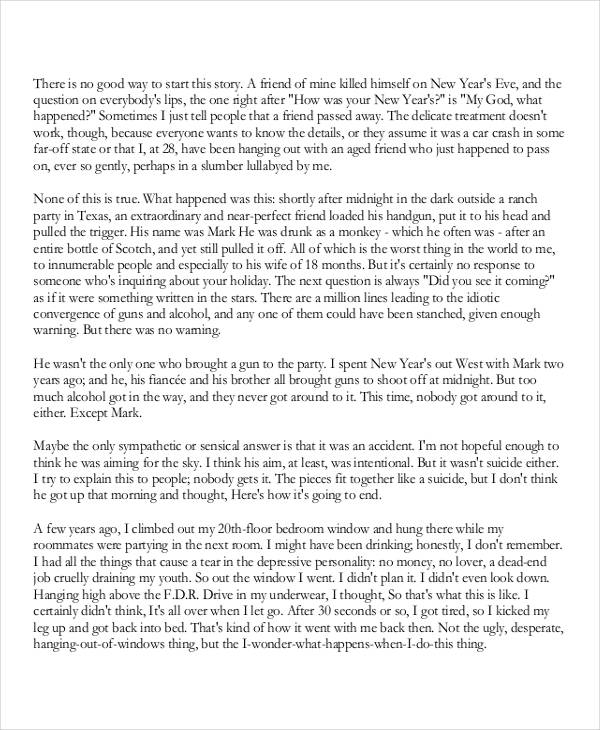

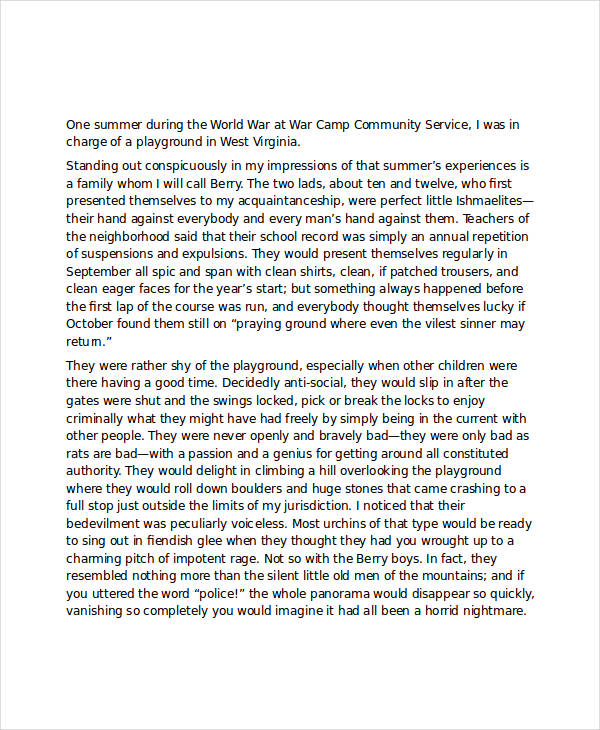

An example of a short narrative essay, responding to the prompt “Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself,” is shown below.

Hover over different parts of the text to see how the structure works.

Since elementary school, I have always favored subjects like science and math over the humanities. My instinct was always to think of these subjects as more solid and serious than classes like English. If there was no right answer, I thought, why bother? But recently I had an experience that taught me my academic interests are more flexible than I had thought: I took my first philosophy class.

Before I entered the classroom, I was skeptical. I waited outside with the other students and wondered what exactly philosophy would involve—I really had no idea. I imagined something pretty abstract: long, stilted conversations pondering the meaning of life. But what I got was something quite different.

A young man in jeans, Mr. Jones—“but you can call me Rob”—was far from the white-haired, buttoned-up old man I had half-expected. And rather than pulling us into pedantic arguments about obscure philosophical points, Rob engaged us on our level. To talk free will, we looked at our own choices. To talk ethics, we looked at dilemmas we had faced ourselves. By the end of class, I’d discovered that questions with no right answer can turn out to be the most interesting ones.

The experience has taught me to look at things a little more “philosophically”—and not just because it was a philosophy class! I learned that if I let go of my preconceptions, I can actually get a lot out of subjects I was previously dismissive of. The class taught me—in more ways than one—to look at things with an open mind.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

If you’re not given much guidance on what your narrative essay should be about, consider the context and scope of the assignment. What kind of story is relevant, interesting, and possible to tell within the word count?

The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to reflect on a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

Don’t worry too much if your topic seems unoriginal. The point of a narrative essay is how you tell the story and the point you make with it, not the subject of the story itself.

Narrative essays are usually assigned as writing exercises at high school or in university composition classes. They may also form part of a university application.

When you are prompted to tell a story about your own life or experiences, a narrative essay is usually the right response.

The key difference is that a narrative essay is designed to tell a complete story, while a descriptive essay is meant to convey an intense description of a particular place, object, or concept.

Narrative and descriptive essays both allow you to write more personally and creatively than other kinds of essays , and similar writing skills can apply to both.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write a Narrative Essay | Example & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/narrative-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write an expository essay, how to write a descriptive essay | example & tips, how to write your personal statement | strategies & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Narrative Writing: A Complete Guide for Teachers and Students

MASTERING THE CRAFT OF NARRATIVE WRITING

Narratives build on and encourage the development of the fundamentals of writing. They also require developing an additional skill set: the ability to tell a good yarn, and storytelling is as old as humanity.

We see and hear stories everywhere and daily, from having good gossip on the doorstep with a neighbor in the morning to the dramas that fill our screens in the evening.

Good narrative writing skills are hard-won by students even though it is an area of writing that most enjoy due to the creativity and freedom it offers.

Here we will explore some of the main elements of a good story: plot, setting, characters, conflict, climax, and resolution . And we will look too at how best we can help our students understand these elements, both in isolation and how they mesh together as a whole.

WHAT IS A NARRATIVE?

A narrative is a story that shares a sequence of events , characters, and themes. It expresses experiences, ideas, and perspectives that should aspire to engage and inspire an audience.

A narrative can spark emotion, encourage reflection, and convey meaning when done well.

Narratives are a popular genre for students and teachers as they allow the writer to share their imagination, creativity, skill, and understanding of nearly all elements of writing. We occasionally refer to a narrative as ‘creative writing’ or story writing.

The purpose of a narrative is simple, to tell the audience a story. It can be written to motivate, educate, or entertain and can be fact or fiction.

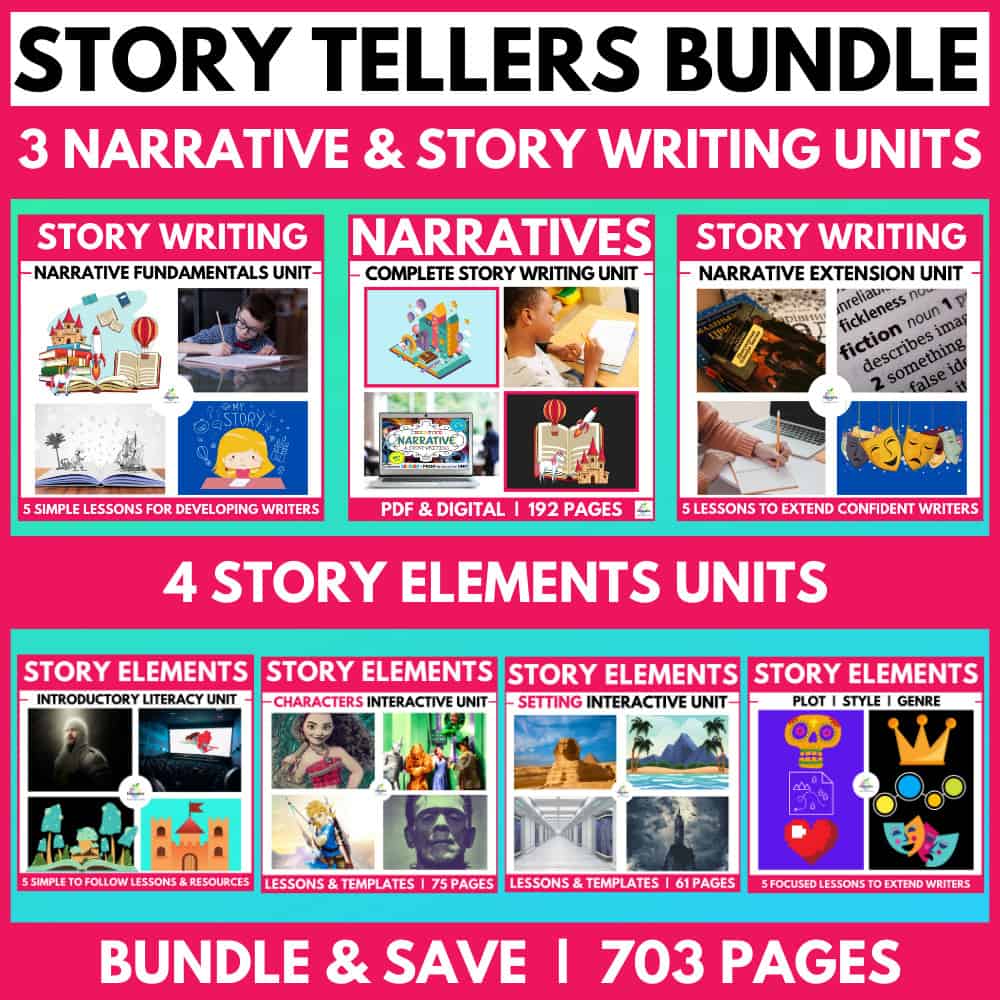

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING NARRATIVE WRITING

Teach your students to become skilled story writers with this HUGE NARRATIVE & CREATIVE STORY WRITING UNIT . Offering a COMPLETE SOLUTION to teaching students how to craft CREATIVE CHARACTERS, SUPERB SETTINGS, and PERFECT PLOTS .

Over 192 PAGES of materials, including:

TYPES OF NARRATIVE WRITING

There are many narrative writing genres and sub-genres such as these.

We have a complete guide to writing a personal narrative that differs from the traditional story-based narrative covered in this guide. It includes personal narrative writing prompts, resources, and examples and can be found here.

As we can see, narratives are an open-ended form of writing that allows you to showcase creativity in many directions. However, all narratives share a common set of features and structure known as “Story Elements”, which are briefly covered in this guide.

Don’t overlook the importance of understanding story elements and the value this adds to you as a writer who can dissect and create grand narratives. We also have an in-depth guide to understanding story elements here .

CHARACTERISTICS OF NARRATIVE WRITING

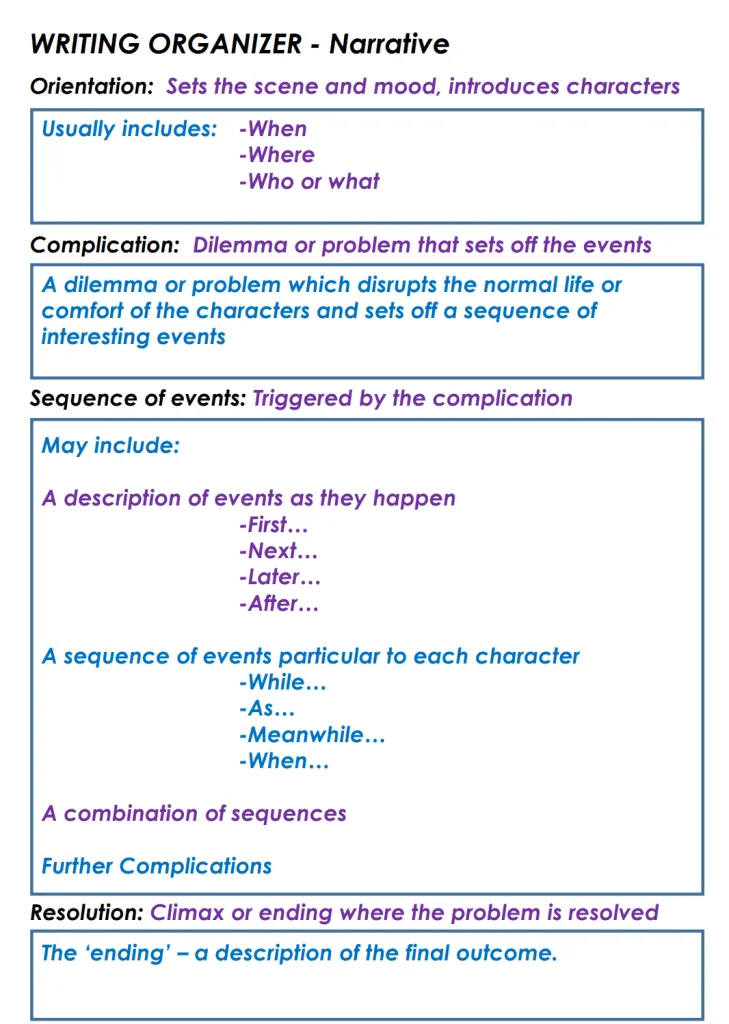

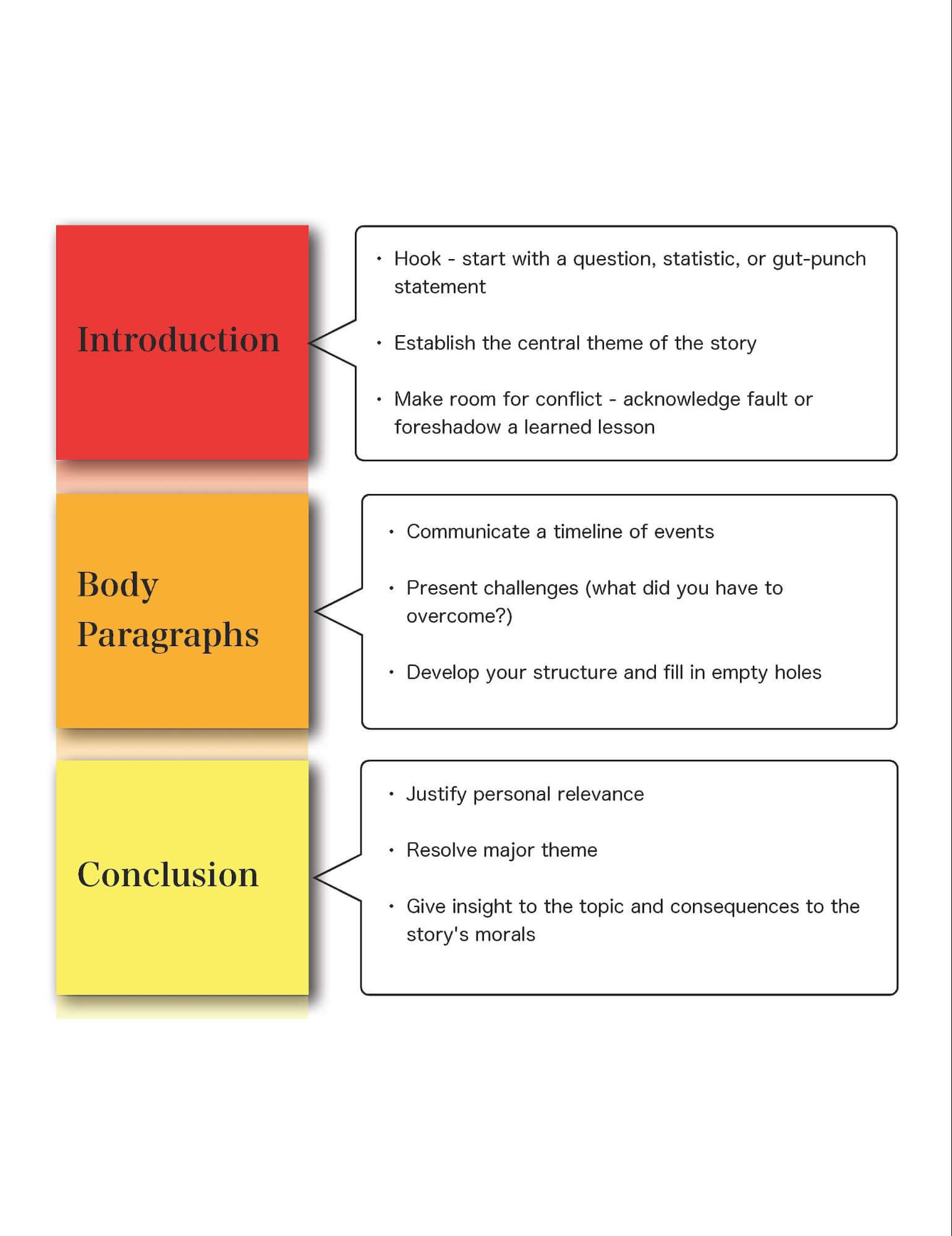

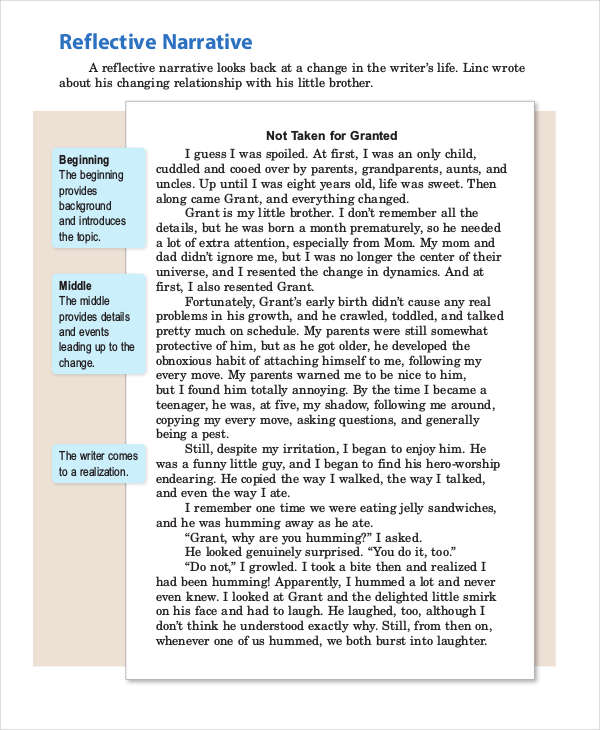

Narrative structure.

ORIENTATION (BEGINNING) Set the scene by introducing your characters, setting and time of the story. Establish your who, when and where in this part of your narrative

COMPLICATION AND EVENTS (MIDDLE) In this section activities and events involving your main characters are expanded upon. These events are written in a cohesive and fluent sequence.

RESOLUTION (ENDING) Your complication is resolved in this section. It does not have to be a happy outcome, however.

EXTRAS: Whilst orientation, complication and resolution are the agreed norms for a narrative, there are numerous examples of popular texts that did not explicitly follow this path exactly.

NARRATIVE FEATURES

LANGUAGE: Use descriptive and figurative language to paint images inside your audience’s minds as they read.

PERSPECTIVE Narratives can be written from any perspective but are most commonly written in first or third person.

DIALOGUE Narratives frequently switch from narrator to first-person dialogue. Always use speech marks when writing dialogue.

TENSE If you change tense, make it perfectly clear to your audience what is happening. Flashbacks might work well in your mind but make sure they translate to your audience.

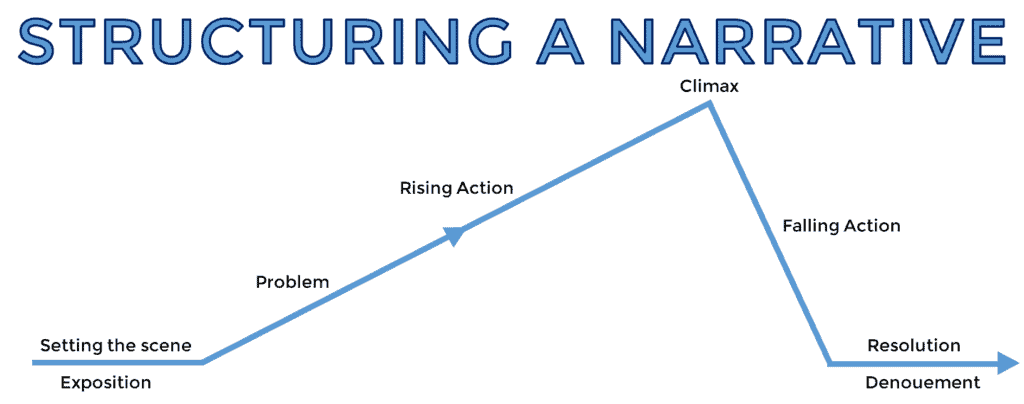

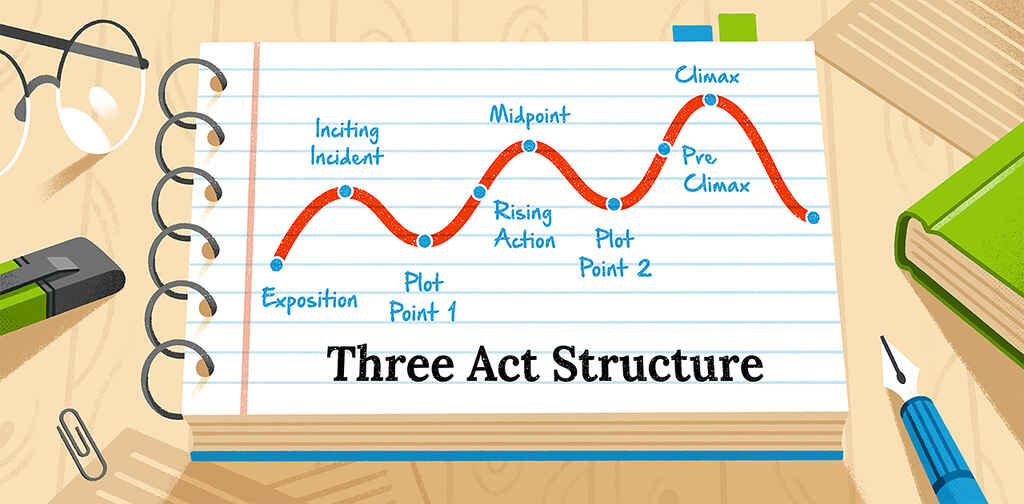

THE PLOT MAP

This graphic is known as a plot map, and nearly all narratives fit this structure in one way or another, whether romance novels, science fiction or otherwise.

It is a simple tool that helps you understand and organise a story’s events. Think of it as a roadmap that outlines the journey of your characters and the events that unfold. It outlines the different stops along the way, such as the introduction, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution, that help you to see how the story builds and develops.

Using a plot map, you can see how each event fits into the larger picture and how the different parts of the story work together to create meaning. It’s a great way to visualize and analyze a story.

Be sure to refer to a plot map when planning a story, as it has all the essential elements of a great story.

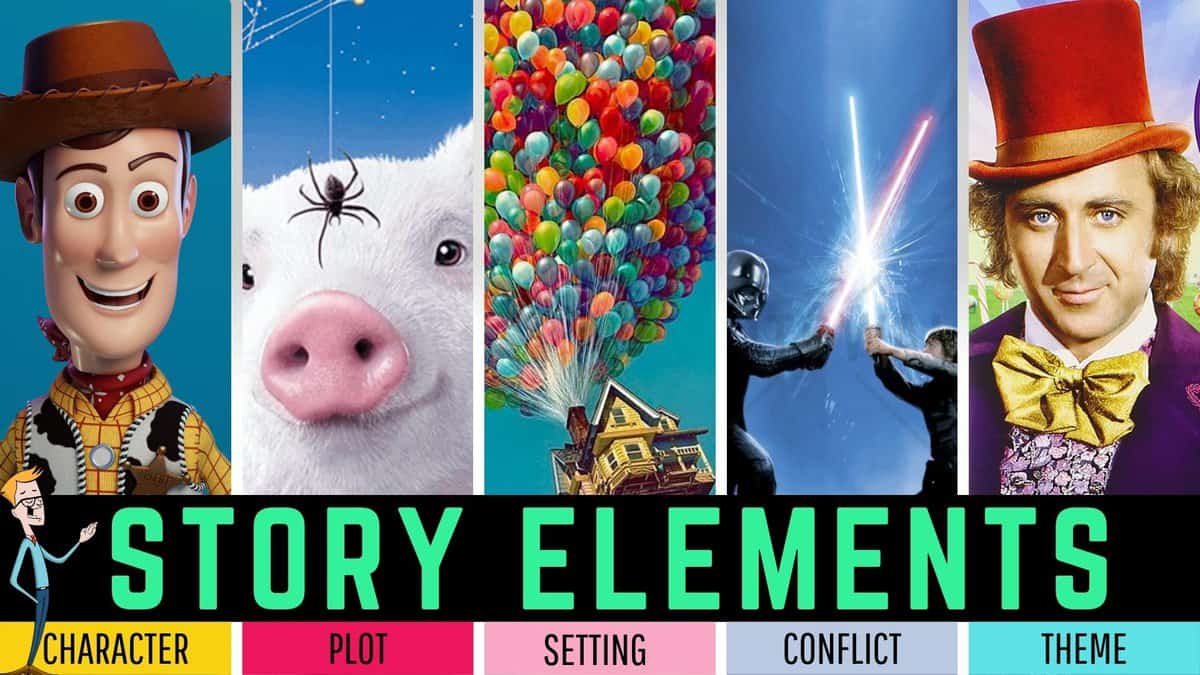

THE 5 KEY STORY ELEMENTS OF A GREAT NARRATIVE (6-MINUTE TUTORIAL VIDEO)

This video we created provides an excellent overview of these elements and demonstrates them in action in stories we all know and love.

HOW TO WRITE A NARRATIVE

Now that we understand the story elements and how they come together to form stories, it’s time to start planning and writing your narrative.

In many cases, the template and guide below will provide enough details on how to craft a great story. However, if you still need assistance with the fundamentals of writing, such as sentence structure, paragraphs and using correct grammar, we have some excellent guides on those here.

USE YOUR WRITING TIME EFFECTIVELY: Maximize your narrative writing sessions by spending approximately 20 per cent of your time planning and preparing. This ensures greater productivity during your writing time and keeps you focused and on task.

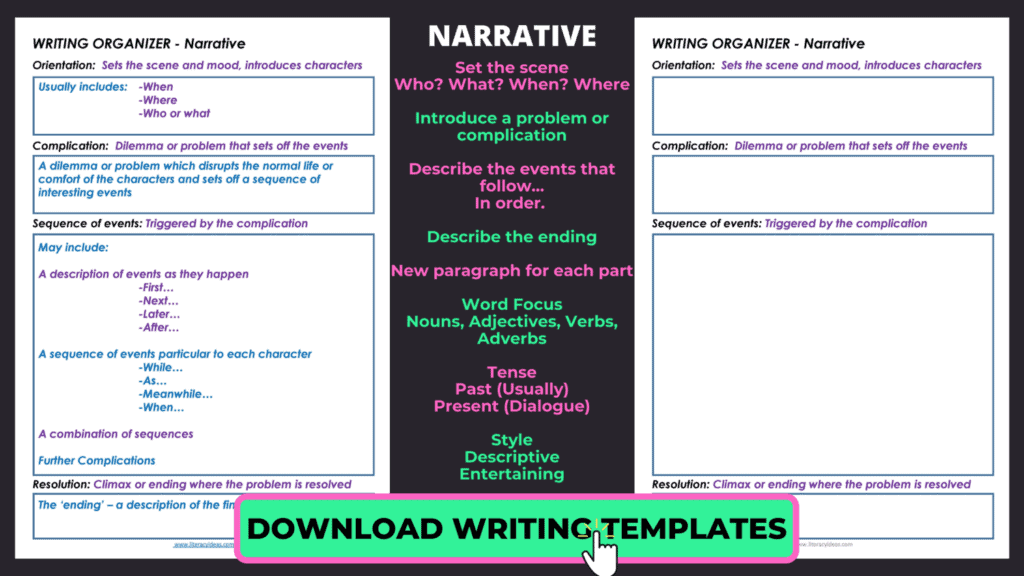

Use tools such as graphic organizers to logically sequence your narrative if you are not a confident story writer. If you are working with reluctant writers, try using narrative writing prompts to get their creative juices flowing.

Spend most of your writing hour on the task at hand, don’t get too side-tracked editing during this time and leave some time for editing. When editing a narrative, examine it for these three elements.

- Spelling and grammar ( Is it readable?)

- Story structure and continuity ( Does it make sense, and does it flow? )

- Character and plot analysis. (Are your characters engaging? Does your problem/resolution work? )

1. SETTING THE SCENE: THE WHERE AND THE WHEN

The story’s setting often answers two of the central questions in the story, namely, the where and the when. The answers to these two crucial questions will often be informed by the type of story the student is writing.

The story’s setting can be chosen to quickly orient the reader to the type of story they are reading. For example, a fictional narrative writing piece such as a horror story will often begin with a description of a haunted house on a hill or an abandoned asylum in the middle of the woods. If we start our story on a rocket ship hurtling through the cosmos on its space voyage to the Alpha Centauri star system, we can be reasonably sure that the story we are embarking on is a work of science fiction.

Such conventions are well-worn clichés true, but they can be helpful starting points for our novice novelists to make a start.

Having students choose an appropriate setting for the type of story they wish to write is an excellent exercise for our younger students. It leads naturally onto the next stage of story writing, which is creating suitable characters to populate this fictional world they have created. However, older or more advanced students may wish to play with the expectations of appropriate settings for their story. They may wish to do this for comic effect or in the interest of creating a more original story. For example, opening a story with a children’s birthday party does not usually set up the expectation of a horror story. Indeed, it may even lure the reader into a happy reverie as they remember their own happy birthday parties. This leaves them more vulnerable to the surprise element of the shocking action that lies ahead.

Once the students have chosen a setting for their story, they need to start writing. Little can be more terrifying to English students than the blank page and its bare whiteness stretching before them on the table like a merciless desert they must cross. Give them the kick-start they need by offering support through word banks or writing prompts. If the class is all writing a story based on the same theme, you may wish to compile a common word bank on the whiteboard as a prewriting activity. Write the central theme or genre in the middle of the board. Have students suggest words or phrases related to the theme and list them on the board.

You may wish to provide students with a copy of various writing prompts to get them started. While this may mean that many students’ stories will have the same beginning, they will most likely arrive at dramatically different endings via dramatically different routes.

A bargain is at the centre of the relationship between the writer and the reader. That bargain is that the reader promises to suspend their disbelief as long as the writer creates a consistent and convincing fictional reality. Creating a believable world for the fictional characters to inhabit requires the student to draw on convincing details. The best way of doing this is through writing that appeals to the senses. Have your student reflect deeply on the world that they are creating. What does it look like? Sound like? What does the food taste like there? How does it feel like to walk those imaginary streets, and what aromas beguile the nose as the main character winds their way through that conjured market?

Also, Consider the when; or the time period. Is it a future world where things are cleaner and more antiseptic? Or is it an overcrowded 16th-century London with human waste stinking up the streets? If students can create a multi-sensory installation in the reader’s mind, then they have done this part of their job well.

Popular Settings from Children’s Literature and Storytelling

- Fairytale Kingdom

- Magical Forest

- Village/town

- Underwater world

- Space/Alien planet

2. CASTING THE CHARACTERS: THE WHO

Now that your student has created a believable world, it is time to populate it with believable characters.

In short stories, these worlds mustn’t be overpopulated beyond what the student’s skill level can manage. Short stories usually only require one main character and a few secondary ones. Think of the short story more as a small-scale dramatic production in an intimate local theater than a Hollywood blockbuster on a grand scale. Too many characters will only confuse and become unwieldy with a canvas this size. Keep it simple!

Creating believable characters is often one of the most challenging aspects of narrative writing for students. Fortunately, we can do a few things to help students here. Sometimes it is helpful for students to model their characters on actual people they know. This can make things a little less daunting and taxing on the imagination. However, whether or not this is the case, writing brief background bios or descriptions of characters’ physical personality characteristics can be a beneficial prewriting activity. Students should give some in-depth consideration to the details of who their character is: How do they walk? What do they look like? Do they have any distinguishing features? A crooked nose? A limp? Bad breath? Small details such as these bring life and, therefore, believability to characters. Students can even cut pictures from magazines to put a face to their character and allow their imaginations to fill in the rest of the details.

Younger students will often dictate to the reader the nature of their characters. To improve their writing craft, students must know when to switch from story-telling mode to story-showing mode. This is particularly true when it comes to character. Encourage students to reveal their character’s personality through what they do rather than merely by lecturing the reader on the faults and virtues of the character’s personality. It might be a small relayed detail in the way they walk that reveals a core characteristic. For example, a character who walks with their head hanging low and shoulders hunched while avoiding eye contact has been revealed to be timid without the word once being mentioned. This is a much more artistic and well-crafted way of doing things and is less irritating for the reader. A character who sits down at the family dinner table immediately snatches up his fork and starts stuffing roast potatoes into his mouth before anyone else has even managed to sit down has revealed a tendency towards greed or gluttony.

Understanding Character Traits

Again, there is room here for some fun and profitable prewriting activities. Give students a list of character traits and have them describe a character doing something that reveals that trait without ever employing the word itself.

It is also essential to avoid adjective stuffing here. When looking at students’ early drafts, adjective stuffing is often apparent. To train the student out of this habit, choose an adjective and have the student rewrite the sentence to express this adjective through action rather than telling.

When writing a story, it is vital to consider the character’s traits and how they will impact the story’s events. For example, a character with a strong trait of determination may be more likely to overcome obstacles and persevere. In contrast, a character with a tendency towards laziness may struggle to achieve their goals. In short, character traits add realism, depth, and meaning to a story, making it more engaging and memorable for the reader.

Popular Character Traits in Children’s Stories

- Determination

- Imagination

- Perseverance

- Responsibility

We have an in-depth guide to creating great characters here , but most students should be fine to move on to planning their conflict and resolution.

3. NO PROBLEM? NO STORY! HOW CONFLICT DRIVES A NARRATIVE

This is often the area apprentice writers have the most difficulty with. Students must understand that without a problem or conflict, there is no story. The problem is the driving force of the action. Usually, in a short story, the problem will center around what the primary character wants to happen or, indeed, wants not to happen. It is the hurdle that must be overcome. It is in the struggle to overcome this hurdle that events happen.

Often when a student understands the need for a problem in a story, their completed work will still not be successful. This is because, often in life, problems remain unsolved. Hurdles are not always successfully overcome. Students pick up on this.

We often discuss problems with friends that will never be satisfactorily resolved one way or the other, and we accept this as a part of life. This is not usually the case with writing a story. Whether a character successfully overcomes his or her problem or is decidedly crushed in the process of trying is not as important as the fact that it will finally be resolved one way or the other.

A good practical exercise for students to get to grips with this is to provide copies of stories and have them identify the central problem or conflict in each through discussion. Familiar fables or fairy tales such as Three Little Pigs, The Boy Who Cried Wolf, Cinderella, etc., are great for this.

While it is true that stories often have more than one problem or that the hero or heroine is unsuccessful in their first attempt to solve a central problem, for beginning students and intermediate students, it is best to focus on a single problem, especially given the scope of story writing at this level. Over time students will develop their abilities to handle more complex plots and write accordingly.

Popular Conflicts found in Children’s Storytelling.

- Good vs evil

- Individual vs society

- Nature vs nurture

- Self vs others

- Man vs self

- Man vs nature

- Man vs technology

- Individual vs fate

- Self vs destiny

Conflict is the heart and soul of any good story. It’s what makes a story compelling and drives the plot forward. Without conflict, there is no story. Every great story has a struggle or a problem that needs to be solved, and that’s where conflict comes in. Conflict is what makes a story exciting and keeps the reader engaged. It creates tension and suspense and makes the reader care about the outcome.

Like in real life, conflict in a story is an opportunity for a character’s growth and transformation. It’s a chance for them to learn and evolve, making a story great. So next time stories are written in the classroom, remember that conflict is an essential ingredient, and without it, your story will lack the energy, excitement, and meaning that makes it truly memorable.

4. THE NARRATIVE CLIMAX: HOW THINGS COME TO A HEAD!

The climax of the story is the dramatic high point of the action. It is also when the struggles kicked off by the problem come to a head. The climax will ultimately decide whether the story will have a happy or tragic ending. In the climax, two opposing forces duke things out until the bitter (or sweet!) end. One force ultimately emerges triumphant. As the action builds throughout the story, suspense increases as the reader wonders which of these forces will win out. The climax is the release of this suspense.

Much of the success of the climax depends on how well the other elements of the story have been achieved. If the student has created a well-drawn and believable character that the reader can identify with and feel for, then the climax will be more powerful.

The nature of the problem is also essential as it determines what’s at stake in the climax. The problem must matter dearly to the main character if it matters at all to the reader.

Have students engage in discussions about their favorite movies and books. Have them think about the storyline and decide the most exciting parts. What was at stake at these moments? What happened in your body as you read or watched? Did you breathe faster? Or grip the cushion hard? Did your heart rate increase, or did you start to sweat? This is what a good climax does and what our students should strive to do in their stories.

The climax puts it all on the line and rolls the dice. Let the chips fall where the writer may…

Popular Climax themes in Children’s Stories

- A battle between good and evil

- The character’s bravery saves the day

- Character faces their fears and overcomes them

- The character solves a mystery or puzzle.

- The character stands up for what is right.

- Character reaches their goal or dream.

- The character learns a valuable lesson.

- The character makes a selfless sacrifice.

- The character makes a difficult decision.

- The character reunites with loved ones or finds true friendship.

5. RESOLUTION: TYING UP LOOSE ENDS

After the climactic action, a few questions will often remain unresolved for the reader, even if all the conflict has been resolved. The resolution is where those lingering questions will be answered. The resolution in a short story may only be a brief paragraph or two. But, in most cases, it will still be necessary to include an ending immediately after the climax can feel too abrupt and leave the reader feeling unfulfilled.

An easy way to explain resolution to students struggling to grasp the concept is to point to the traditional resolution of fairy tales, the “And they all lived happily ever after” ending. This weather forecast for the future allows the reader to take their leave. Have the student consider the emotions they want to leave the reader with when crafting their resolution.

While the action is usually complete by the end of the climax, it is in the resolution that if there is a twist to be found, it will appear – think of movies such as The Usual Suspects. Pulling this off convincingly usually requires considerable skill from a student writer. Still, it may well form a challenging extension exercise for those more gifted storytellers among your students.

Popular Resolutions in Children’s Stories

- Our hero achieves their goal

- The character learns a valuable lesson

- A character finds happiness or inner peace.

- The character reunites with loved ones.

- Character restores balance to the world.

- The character discovers their true identity.

- Character changes for the better.

- The character gains wisdom or understanding.

- Character makes amends with others.

- The character learns to appreciate what they have.

Once students have completed their story, they can edit for grammar, vocabulary choice, spelling, etc., but not before!

As mentioned, there is a craft to storytelling, as well as an art. When accurate grammar, perfect spelling, and immaculate sentence structures are pushed at the outset, they can cause storytelling paralysis. For this reason, it is essential that when we encourage the students to write a story, we give them license to make mechanical mistakes in their use of language that they can work on and fix later.

Good narrative writing is a very complex skill to develop and will take the student years to become competent. It challenges not only the student’s technical abilities with language but also her creative faculties. Writing frames, word banks, mind maps, and visual prompts can all give valuable support as students develop the wide-ranging and challenging skills required to produce a successful narrative writing piece. But, at the end of it all, as with any craft, practice and more practice is at the heart of the matter.

TIPS FOR WRITING A GREAT NARRATIVE

- Start your story with a clear purpose: If you can determine the theme or message you want to convey in your narrative before starting it will make the writing process so much simpler.

- Choose a compelling storyline and sell it through great characters, setting and plot: Consider a unique or interesting story that captures the reader’s attention, then build the world and characters around it.

- Develop vivid characters that are not all the same: Make your characters relatable and memorable by giving them distinct personalities and traits you can draw upon in the plot.

- Use descriptive language to hook your audience into your story: Use sensory language to paint vivid images and sequences in the reader’s mind.

- Show, don’t tell your audience: Use actions, thoughts, and dialogue to reveal character motivations and emotions through storytelling.

- Create a vivid setting that is clear to your audience before getting too far into the plot: Describe the time and place of your story to immerse the reader fully.

- Build tension: Refer to the story map earlier in this article and use conflict, obstacles, and suspense to keep the audience engaged and invested in your narrative.

- Use figurative language such as metaphors, similes, and other literary devices to add depth and meaning to your narrative.

- Edit, revise, and refine: Take the time to refine and polish your writing for clarity and impact.

- Stay true to your voice: Maintain your unique perspective and style in your writing to make it your own.

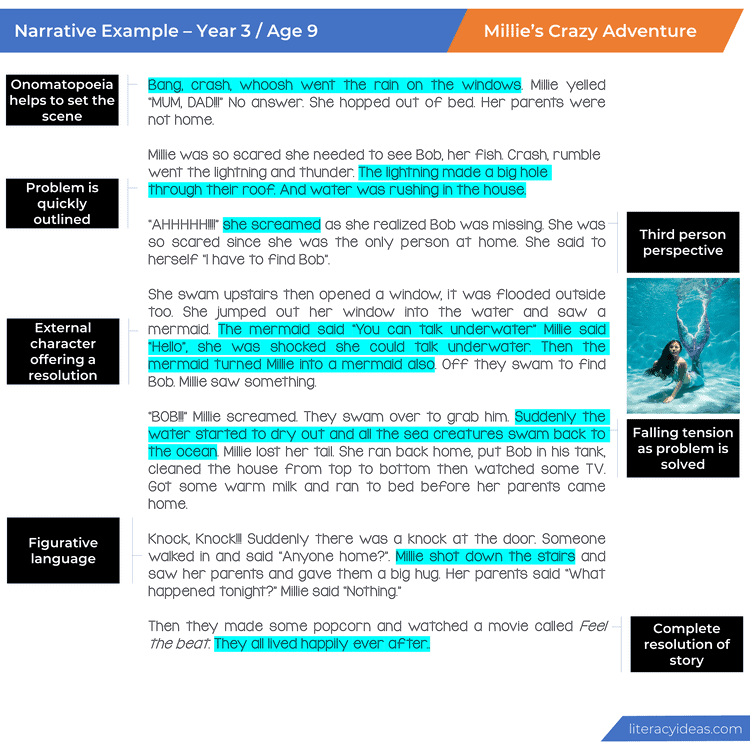

NARRATIVE WRITING EXAMPLES (Student Writing Samples)

Below are a collection of student writing samples of narratives. Click on the image to enlarge and explore them in greater detail. Please take a moment to read these creative stories in detail and the teacher and student guides which highlight some of the critical elements of narratives to consider before writing.

Please understand these student writing samples are not intended to be perfect examples for each age or grade level but a piece of writing for students and teachers to explore together to critically analyze to improve student writing skills and deepen their understanding of story writing.

We recommend reading the example either a year above or below, as well as the grade you are currently working with, to gain a broader appreciation of this text type.

NARRATIVE WRITING PROMPTS (Journal Prompts)

When students have a great journal prompt, it can help them focus on the task at hand, so be sure to view our vast collection of visual writing prompts for various text types here or use some of these.

- On a recent European trip, you find your travel group booked into the stunning and mysterious Castle Frankenfurter for a single night… As night falls, the massive castle of over one hundred rooms seems to creak and groan as a series of unexplained events begin to make you wonder who or what else is spending the evening with you. Write a narrative that tells the story of your evening.

- You are a famous adventurer who has discovered new lands; keep a travel log over a period of time in which you encounter new and exciting adventures and challenges to overcome. Ensure your travel journal tells a story and has a definite introduction, conflict and resolution.

- You create an incredible piece of technology that has the capacity to change the world. As you sit back and marvel at your innovation and the endless possibilities ahead of you, it becomes apparent there are a few problems you didn’t really consider. You might not even be able to control them. Write a narrative in which you ride the highs and lows of your world-changing creation with a clear introduction, conflict and resolution.

- As the final door shuts on the Megamall, you realise you have done it… You and your best friend have managed to sneak into the largest shopping centre in town and have the entire place to yourselves until 7 am tomorrow. There is literally everything and anything a child would dream of entertaining themselves for the next 12 hours. What amazing adventures await you? What might go wrong? And how will you get out of there scot-free?

- A stranger walks into town… Whilst appearing similar to almost all those around you, you get a sense that this person is from another time, space or dimension… Are they friends or foes? What makes you sense something very strange is going on? Suddenly they stand up and walk toward you with purpose extending their hand… It’s almost as if they were reading your mind.

NARRATIVE WRITING VIDEO TUTORIAL

Teaching Resources

Use our resources and tools to improve your student’s writing skills through proven teaching strategies.

When teaching narrative writing, it is essential that you have a range of tools, strategies and resources at your disposal to ensure you get the most out of your writing time. You can find some examples below, which are free and paid premium resources you can use instantly without any preparation.

FREE Narrative Graphic Organizer

THE STORY TELLERS BUNDLE OF TEACHING RESOURCES

A MASSIVE COLLECTION of resources for narratives and story writing in the classroom covering all elements of crafting amazing stories. MONTHS WORTH OF WRITING LESSONS AND RESOURCES, including:

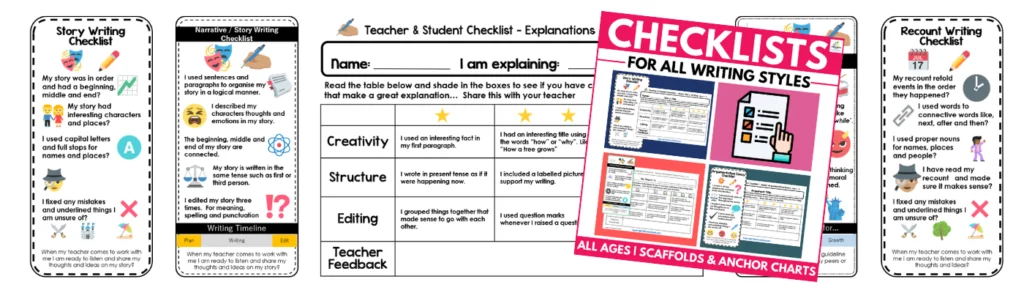

NARRATIVE WRITING CHECKLIST BUNDLE

OTHER GREAT ARTICLES ABOUT NARRATIVE WRITING

Narrative Writing for Kids: Essential Skills and Strategies

7 Great Narrative Lesson Plans Students and Teachers Love

Top 7 Narrative Writing Exercises for Students

How to Write a Scary Story

Understanding Narrative Writing (Examples, Prompts, and More)

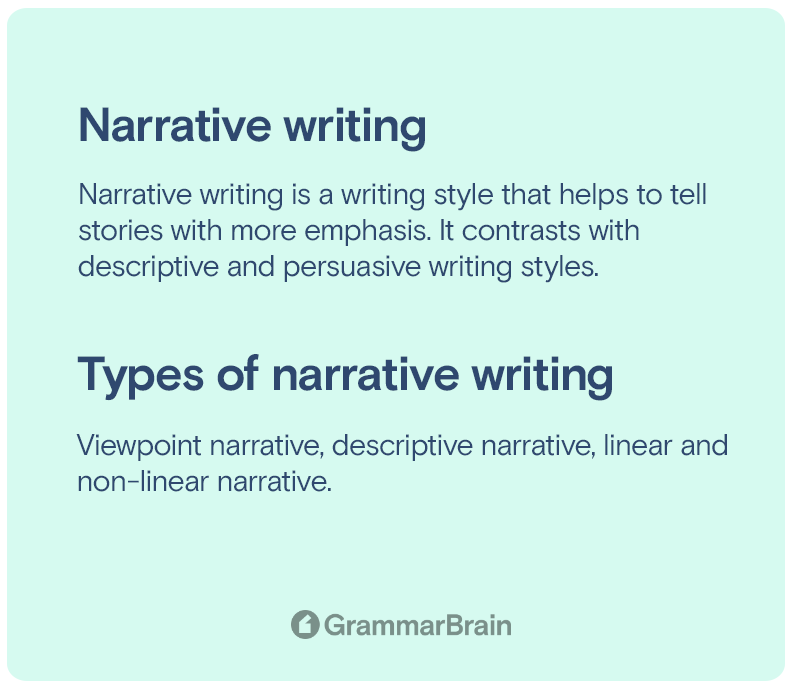

Narrative writing is a writing style that helps to tell stories with more emphasis. It contrasts with descriptive and persuasive writing styles. Learn everything you need to know about narrative writing in this comprehensive guide.

What is narrative writing?

We have all read stories- both fictional and non-fictional. Narrative writing is exactly that- it is storytelling. While most narrative-style writing has a main character or protagonist, sometimes narratives can be about humanizing inanimate objects or abstract feelings.

Whatever happens to the said character or protagonist is called the story or the plot. Like most stories, narrative writing has conflict, resolution, and observation, and is in short- a story you would want to read.

Narrative writing is just one of the writing styles among others, namely expository, descriptive and persuasive writing . While all of the listed styles are very distinct, it is easy to confuse them for another. Hence, it is important to know the difference between each.

Descriptive Writing

A descriptive style of writing focuses on rich imagery and sensory description of smells, sights, and sounds. It is usually used in screenplays, essays, and poems. It serves the purpose of immersion- where the reader can actively imagine themselves being transported to the place or situation that the author describes.

- Persuasive Writing

Persuasive writing is much like a political or philosophical text where one side attempts to establish its stance. Being persuasive in your writing style is a needed skill for reviewers and political columnists. Especially since they give essential takes on situations and decisions where the reader is persuaded by the text to agree or disagree with a certain argument. This style of writing is also applied in speeches, slogans, editorials, and opinion pieces.

How is narrative writing different from the expository style of writing?

To know that we must first know what the expository style of writing is. Expository writing is more about facts than fiction. Think textbooks, neutral news articles, etc. Anything that states facts without sensationalizing them is an exposition. This is in direct contrast with narrative writing which is more about storytelling than about facts.

What is a personal narrative?

As the name suggests, a personal narrative is about a person. Usually, this person is you. A personal narrative helps see things from your personal perspective. Personal narratives are used where intimacy is required.

Because they offer a window into the writers’ beliefs, methods, and emotions, memoirs, autobiographies, and deeply personal story pieces captivate us as readers. However, publishing your whole life story is not necessary to produce a personal narrative.

A cover letter or an admissions essay may be written by a student, or you may be attempting to describe your relevant qualifications. Your story will center on personal development, thoughts, and experiences irrespective of your goal.

Because of its digestible style and the fact that humans are empathic beings, personal tales enable us to relate to the experiences of others.

Types of narrative writing

1. viewpoint narrative.

Viewpoint narrative tells the story from the eyes of the protagonist. This lends a unique lens to the story as the reader journeys through the paragraphs to see it unfold in real-time as the protagonist goes through the events.

For instance, Moby Dick by Herman Melville utilized viewpoint narrative to make Ishmael’s motives in the story hit home for the reader.

2. Descriptive Narrative

This is usually written in the third person as the descriptive narrative style entails a descriptive account of a situation, person, or place. But, many descriptive style narratives are written in the first person too. Usually, it uses vivid imagery and sensory words that help the reader immerse in the story.

3. Linear and Non-Linear Narrative

If the progression of the events in the plot happens one after the other, then it is a linear narrative style of writing. For example, in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, everything happens in a linear chronological order. Whereas in a book like The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown, there are multiple competing timelines that occur simultaneously. Such a style of narrative writing is non-linear.

Components/Devices needed to craft a narrative

1. Descriptive communication : Instead of explaining facts straight, this form of language elicits sentiments. Imagery, personification, similes, and metaphors are examples of descriptive linguistic devices.

2. Characters: A narrative may have a small cast of characters or a large one. The narrator is sometimes the lone character to appear in certain narratives. The tale is being recounted from the perspective of the narrator, who may or may not engage with the other characters.

- Protagonist: Almost every story requires a protagonist among the characters. The figure whose tale is being recounted as they strive to accomplish a goal or overcome a struggle is the protagonist. He/She is sometimes referred to as the central character as well.

- Antagonist: The adversary is a figure that appears in almost every story. The villain is just the person or thing that the protagonist must face in order to triumph over hurdles; they are not always the “bad guy.” The adversary can be a person, a natural force, the protagonist’s community, or even a characteristic of the protagonist’s nature in many stories.

3. Plot: The sequence of events that take place in your tale makes up the plot. A storyline might be straightforward with just one or two key events, or it can be intricate and have several layers.

4. Structure: Each narrative, even those that are nonlinear, is ordered in some fashion. This is how the central protagonist chases their objective or responds to a problem. No matter how you arrange your story, there are three main sections:

- Beginning: The moment the reader encounters your words is the start of your narrative. This is important to grab the reader’s attention so that they continue to read through the rest of what you have to say.

- Middle: The middle is the body, where the conflict occurs, and the story sets up the obstacle that needs to be overcome by our protagonist in order to attain something of importance.

- End: The ending is the resolution where the result of our protagonist’s efforts is declared. It could either end positively, negatively or vaguely- where the ultimate fate of the characters is left up to the reader’s imagination.

5. Theme: Each narrative has a theme whether you intend it to be or not. For instance, Harry Potter is about magic, Little Women is about female adolescence, and To Kill a Mockingbird is about racism and childhood trauma.

What do you need to write a narrative?

Narrative writers have most if not all of the following skills:

Organization:

Narratives require a structure, even if it is non-linear and complex, with multiple parallel timelines. For example, To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee is a chronological narrative where the older protagonist narrates a story that happened during her childhood.

Having interesting beginnings:

The start captures the readers and encourages them to keep reading. Hence, it is important to craft interesting beginnings for stories.

For example, George Orwell’s iconic sci-fi novel 1984 opens with the sentence , ‘It was a bright cold day in April and the clocks were striking thirteen.’

It’s an incredible opening to set the mood for a book that is about surveillance and the dystopian future of commodifying privacy.

Description:

Description is like salt- it is necessary, but if overdone, can ruin the story. If what you are describing is not of the essence to the plot, it can get very boring for readers to go through paragraphs of descriptions of meadows(a la Tolkien).

For instance, A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess does a wonderful job of letting the description and detail be an effective plot device. It isn’t overdone nor is it left fully to the readers. It is immersive enough for the reader to be engrossed but relevant enough for the reader to want to keep reading.

Suspense is a great technique to make the reader turn pages. It is a tried and true way to win a reader’s interest. There is simply no way to talk about suspense without mentioning Agatha Cristie. Her 1939 novel And Then There Were None displays the mastery of Cristie. She keeps the reader engaged till the very end to find out who is the killer on the island where a band of vacationers mysteriously die off.

Stretch the main event:

Pacing is incredibly important in storytelling. If you spend 3 chapters setting up a conflict that gets solved in one page, it is not as gratifying of an ending. Hence, it is important that the main event is identified and written about in a way that uses action, description, and ample establishment prior to its reveal.

For example, let’s look at The Hound of Baskervilles by Arthur Conan Doyle:

The wagonette swung round into a side road, and we curved upward through deep lanes worn by centuries of wheels, high banks on either side, heavy with dripping moss and fleshy hart’s-tongue ferns. Bronzing bracken and mottled bramble gleamed in the light of the sinking sun. Still steadily rising, we passed over a narrow granite bridge and skirted a noisy stream that gushed swiftly down, foaming and roaring amid the gray boulders. Both road and stream wound up through a valley dense with scrub oak and fir.

At every turn Baskerville gave an exclamation of delight, looking eagerly about him and asking countless questions. To his eyes, all seemed beautiful, but to me , a tinge of melancholy lay upon the countryside, which bore so clearly the mark of the waning year. Yellow leaves carpeted the lanes and fluttered down upon us as we passed. The rattle of our wheels died away as we drove through drifts of rotting vegetation. Sad gifts, as it seemed to me, for Nature to throw before the carriage of the returning heir of the Baskervilles.

The majority of the chapter’s first half was made up of rather fast-paced conversation. But the action slows down when the protagonists approach the moor. Doyle uses a couple of techniques to maintain this slower tempo. The wording grows increasingly detailed as the phrases lengthen and become more complicated. This is a great example of good pacing while describing the main events.

Good endings:

Good endings don’t mean that the end needs to be a happy one. It just means that it has to make sense and leave the reader with a feeling of something intense. It can be happiness, sadness, anger, or even hopefulness. What the reader shouldn’t feel are boredom and predictability. In many cases of good stories, even if the ending is predictable, it is done in a way that makes sense and leaves the reader wanting more.

Narrative writing prompts to use:

- Finish this story: The pirates set sail on their ship in search of . . .

- Write about a time you wished you were somewhere/someone else

- Write a story that ends with: ‘Our paths were different, but our destination was the same.’

- Write a story using the following words: elephant, diaper, rose, house

Inside this article

Fact checked: Content is rigorously reviewed by a team of qualified and experienced fact checkers. Fact checkers review articles for factual accuracy, relevance, and timeliness. Learn more.

About the author

Dalia Y.: Dalia is an English Major and linguistics expert with an additional degree in Psychology. Dalia has featured articles on Forbes, Inc, Fast Company, Grammarly, and many more. She covers English, ESL, and all things grammar on GrammarBrain.

Core lessons

- Abstract Noun

- Accusative Case

- Active Sentence

- Alliteration

- Adjective Clause

- Adjective Phrase

- Adverbial Clause

- Appositive Phrase

- Body Paragraph

- Compound Adjective

- Complex Sentence

- Compound Words

- Compound Predicate

- Common Noun

- Comparative Adjective

- Comparative and Superlative

- Compound Noun

- Compound Subject

- Compound Sentence

- Copular Verb

- Collective Noun

- Colloquialism

- Conciseness

- Conditional

- Concrete Noun

- Conjunction

- Conjugation

- Conditional Sentence

- Comma Splice

- Correlative Conjunction

- Coordinating Conjunction

- Coordinate Adjective

- Cumulative Adjective

- Dative Case

- Declarative Statement

- Direct Object Pronoun

- Direct Object

- Dangling Modifier

- Demonstrative Pronoun

- Demonstrative Adjective

- Direct Characterization

- Definite Article

- Doublespeak

- Equivocation Fallacy

- Future Perfect Progressive

- Future Simple

- Future Perfect Continuous

- Future Perfect

- First Conditional

- Gerund Phrase

- Genitive Case

- Helping Verb

- Irregular Adjective

- Irregular Verb

- Imperative Sentence

- Indefinite Article

- Intransitive Verb

- Introductory Phrase

- Indefinite Pronoun

- Indirect Characterization

- Interrogative Sentence

- Intensive Pronoun

- Inanimate Object

- Indefinite Tense

- Infinitive Phrase

- Interjection

- Intensifier

- Indicative Mood

- Juxtaposition

- Linking Verb

- Misplaced Modifier

- Nominative Case

- Noun Adjective

- Object Pronoun

- Object Complement

- Order of Adjectives

- Parallelism

- Prepositional Phrase

- Past Simple Tense

- Past Continuous Tense

- Past Perfect Tense

- Past Progressive Tense

- Present Simple Tense

- Present Perfect Tense

- Personal Pronoun

- Personification

- Parallel Structure

- Phrasal Verb

- Predicate Adjective

- Predicate Nominative

- Phonetic Language

- Plural Noun

- Punctuation

- Punctuation Marks

- Preposition

- Preposition of Place

- Parts of Speech

- Possessive Adjective

- Possessive Determiner

- Possessive Case

- Possessive Noun

- Proper Adjective

- Proper Noun

- Present Participle

- Quotation Marks

- Relative Pronoun

- Reflexive Pronoun

- Reciprocal Pronoun

- Subordinating Conjunction

- Simple Future Tense

- Stative Verb

- Subjunctive

- Subject Complement

- Subject of a Sentence

- Sentence Variety

- Second Conditional

- Superlative Adjective

- Slash Symbol

- Topic Sentence

- Types of Nouns

- Types of Sentences

- Uncountable Noun

- Vowels and Consonants

Popular lessons

Stay awhile. Your weekly dose of grammar and English fun.

The world's best online resource for learning English. Understand words, phrases, slang terms, and all other variations of the English language.

- Abbreviations

- Editorial Policy

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, 3 great narrative essay examples + tips for writing.

General Education

A narrative essay is one of the most intimidating assignments you can be handed at any level of your education. Where you've previously written argumentative essays that make a point or analytic essays that dissect meaning, a narrative essay asks you to write what is effectively a story .

But unlike a simple work of creative fiction, your narrative essay must have a clear and concrete motif —a recurring theme or idea that you’ll explore throughout. Narrative essays are less rigid, more creative in expression, and therefore pretty different from most other essays you’ll be writing.

But not to fear—in this article, we’ll be covering what a narrative essay is, how to write a good one, and also analyzing some personal narrative essay examples to show you what a great one looks like.

What Is a Narrative Essay?

At first glance, a narrative essay might sound like you’re just writing a story. Like the stories you're used to reading, a narrative essay is generally (but not always) chronological, following a clear throughline from beginning to end. Even if the story jumps around in time, all the details will come back to one specific theme, demonstrated through your choice in motifs.

Unlike many creative stories, however, your narrative essay should be based in fact. That doesn’t mean that every detail needs to be pure and untainted by imagination, but rather that you shouldn’t wholly invent the events of your narrative essay. There’s nothing wrong with inventing a person’s words if you can’t remember them exactly, but you shouldn’t say they said something they weren’t even close to saying.

Another big difference between narrative essays and creative fiction—as well as other kinds of essays—is that narrative essays are based on motifs. A motif is a dominant idea or theme, one that you establish before writing the essay. As you’re crafting the narrative, it’ll feed back into your motif to create a comprehensive picture of whatever that motif is.

For example, say you want to write a narrative essay about how your first day in high school helped you establish your identity. You might discuss events like trying to figure out where to sit in the cafeteria, having to describe yourself in five words as an icebreaker in your math class, or being unsure what to do during your lunch break because it’s no longer acceptable to go outside and play during lunch. All of those ideas feed back into the central motif of establishing your identity.

The important thing to remember is that while a narrative essay is typically told chronologically and intended to read like a story, it is not purely for entertainment value. A narrative essay delivers its theme by deliberately weaving the motifs through the events, scenes, and details. While a narrative essay may be entertaining, its primary purpose is to tell a complete story based on a central meaning.

Unlike other essay forms, it is totally okay—even expected—to use first-person narration in narrative essays. If you’re writing a story about yourself, it’s natural to refer to yourself within the essay. It’s also okay to use other perspectives, such as third- or even second-person, but that should only be done if it better serves your motif. Generally speaking, your narrative essay should be in first-person perspective.

Though your motif choices may feel at times like you’re making a point the way you would in an argumentative essay, a narrative essay’s goal is to tell a story, not convince the reader of anything. Your reader should be able to tell what your motif is from reading, but you don’t have to change their mind about anything. If they don’t understand the point you are making, you should consider strengthening the delivery of the events and descriptions that support your motif.

Narrative essays also share some features with analytical essays, in which you derive meaning from a book, film, or other media. But narrative essays work differently—you’re not trying to draw meaning from an existing text, but rather using an event you’ve experienced to convey meaning. In an analytical essay, you examine narrative, whereas in a narrative essay you create narrative.

The structure of a narrative essay is also a bit different than other essays. You’ll generally be getting your point across chronologically as opposed to grouping together specific arguments in paragraphs or sections. To return to the example of an essay discussing your first day of high school and how it impacted the shaping of your identity, it would be weird to put the events out of order, even if not knowing what to do after lunch feels like a stronger idea than choosing where to sit. Instead of organizing to deliver your information based on maximum impact, you’ll be telling your story as it happened, using concrete details to reinforce your theme.

3 Great Narrative Essay Examples

One of the best ways to learn how to write a narrative essay is to look at a great narrative essay sample. Let’s take a look at some truly stellar narrative essay examples and dive into what exactly makes them work so well.

A Ticket to the Fair by David Foster Wallace

Today is Press Day at the Illinois State Fair in Springfield, and I’m supposed to be at the fairgrounds by 9:00 A.M. to get my credentials. I imagine credentials to be a small white card in the band of a fedora. I’ve never been considered press before. My real interest in credentials is getting into rides and shows for free. I’m fresh in from the East Coast, for an East Coast magazine. Why exactly they’re interested in the Illinois State Fair remains unclear to me. I suspect that every so often editors at East Coast magazines slap their foreheads and remember that about 90 percent of the United States lies between the coasts, and figure they’ll engage somebody to do pith-helmeted anthropological reporting on something rural and heartlandish. I think they asked me to do this because I grew up here, just a couple hours’ drive from downstate Springfield. I never did go to the state fair, though—I pretty much topped out at the county fair level. Actually, I haven’t been back to Illinois for a long time, and I can’t say I’ve missed it.

Throughout this essay, David Foster Wallace recounts his experience as press at the Illinois State Fair. But it’s clear from this opening that he’s not just reporting on the events exactly as they happened—though that’s also true— but rather making a point about how the East Coast, where he lives and works, thinks about the Midwest.

In his opening paragraph, Wallace states that outright: “Why exactly they’re interested in the Illinois State Fair remains unclear to me. I suspect that every so often editors at East Coast magazines slap their foreheads and remember that about 90 percent of the United States lies between the coasts, and figure they’ll engage somebody to do pith-helmeted anthropological reporting on something rural and heartlandish.”

Not every motif needs to be stated this clearly , but in an essay as long as Wallace’s, particularly since the audience for such a piece may feel similarly and forget that such a large portion of the country exists, it’s important to make that point clear.

But Wallace doesn’t just rest on introducing his motif and telling the events exactly as they occurred from there. It’s clear that he selects events that remind us of that idea of East Coast cynicism , such as when he realizes that the Help Me Grow tent is standing on top of fake grass that is killing the real grass beneath, when he realizes the hypocrisy of craving a corn dog when faced with a real, suffering pig, when he’s upset for his friend even though he’s not the one being sexually harassed, and when he witnesses another East Coast person doing something he wouldn’t dare to do.

Wallace is literally telling the audience exactly what happened, complete with dates and timestamps for when each event occurred. But he’s also choosing those events with a purpose—he doesn’t focus on details that don’t serve his motif. That’s why he discusses the experiences of people, how the smells are unappealing to him, and how all the people he meets, in cowboy hats, overalls, or “black spandex that looks like cheesecake leotards,” feel almost alien to him.

All of these details feed back into the throughline of East Coast thinking that Wallace introduces in the first paragraph. He also refers back to it in the essay’s final paragraph, stating:

At last, an overarching theory blooms inside my head: megalopolitan East Coasters’ summer treats and breaks and literally ‘getaways,’ flights-from—from crowds, noise, heat, dirt, the stress of too many sensory choices….The East Coast existential treat is escape from confines and stimuli—quiet, rustic vistas that hold still, turn inward, turn away. Not so in the rural Midwest. Here you’re pretty much away all the time….Something in a Midwesterner sort of actuates , deep down, at a public event….The real spectacle that draws us here is us.

Throughout this journey, Wallace has tried to demonstrate how the East Coast thinks about the Midwest, ultimately concluding that they are captivated by the Midwest’s less stimuli-filled life, but that the real reason they are interested in events like the Illinois State Fair is that they are, in some ways, a means of looking at the East Coast in a new, estranging way.

The reason this works so well is that Wallace has carefully chosen his examples, outlined his motif and themes in the first paragraph, and eventually circled back to the original motif with a clearer understanding of his original point.

When outlining your own narrative essay, try to do the same. Start with a theme, build upon it with examples, and return to it in the end with an even deeper understanding of the original issue. You don’t need this much space to explore a theme, either—as we’ll see in the next example, a strong narrative essay can also be very short.

Death of a Moth by Virginia Woolf

After a time, tired by his dancing apparently, he settled on the window ledge in the sun, and, the queer spectacle being at an end, I forgot about him. Then, looking up, my eye was caught by him. He was trying to resume his dancing, but seemed either so stiff or so awkward that he could only flutter to the bottom of the window-pane; and when he tried to fly across it he failed. Being intent on other matters I watched these futile attempts for a time without thinking, unconsciously waiting for him to resume his flight, as one waits for a machine, that has stopped momentarily, to start again without considering the reason of its failure. After perhaps a seventh attempt he slipped from the wooden ledge and fell, fluttering his wings, on to his back on the window sill. The helplessness of his attitude roused me. It flashed upon me that he was in difficulties; he could no longer raise himself; his legs struggled vainly. But, as I stretched out a pencil, meaning to help him to right himself, it came over me that the failure and awkwardness were the approach of death. I laid the pencil down again.

In this essay, Virginia Woolf explains her encounter with a dying moth. On surface level, this essay is just a recounting of an afternoon in which she watched a moth die—it’s even established in the title. But there’s more to it than that. Though Woolf does not begin her essay with as clear a motif as Wallace, it’s not hard to pick out the evidence she uses to support her point, which is that the experience of this moth is also the human experience.

In the title, Woolf tells us this essay is about death. But in the first paragraph, she seems to mostly be discussing life—the moth is “content with life,” people are working in the fields, and birds are flying. However, she mentions that it is mid-September and that the fields were being plowed. It’s autumn and it’s time for the harvest; the time of year in which many things die.

In this short essay, she chronicles the experience of watching a moth seemingly embody life, then die. Though this essay is literally about a moth, it’s also about a whole lot more than that. After all, moths aren’t the only things that die—Woolf is also reflecting on her own mortality, as well as the mortality of everything around her.

At its core, the essay discusses the push and pull of life and death, not in a way that’s necessarily sad, but in a way that is accepting of both. Woolf begins by setting up the transitional fall season, often associated with things coming to an end, and raises the ideas of pleasure, vitality, and pity.

At one point, Woolf tries to help the dying moth, but reconsiders, as it would interfere with the natural order of the world. The moth’s death is part of the natural order of the world, just like fall, just like her own eventual death.

All these themes are set up in the beginning and explored throughout the essay’s narrative. Though Woolf doesn’t directly state her theme, she reinforces it by choosing a small, isolated event—watching a moth die—and illustrating her point through details.

With this essay, we can see that you don’t need a big, weird, exciting event to discuss an important meaning. Woolf is able to explore complicated ideas in a short essay by being deliberate about what details she includes, just as you can be in your own essays.

Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin

On the twenty-ninth of July, in 1943, my father died. On the same day, a few hours later, his last child was born. Over a month before this, while all our energies were concentrated in waiting for these events, there had been, in Detroit, one of the bloodiest race riots of the century. A few hours after my father’s funeral, while he lay in state in the undertaker’s chapel, a race riot broke out in Harlem. On the morning of the third of August, we drove my father to the graveyard through a wilderness of smashed plate glass.

Like Woolf, Baldwin does not lay out his themes in concrete terms—unlike Wallace, there’s no clear sentence that explains what he’ll be talking about. However, you can see the motifs quite clearly: death, fatherhood, struggle, and race.

Throughout the narrative essay, Baldwin discusses the circumstances of his father’s death, including his complicated relationship with his father. By introducing those motifs in the first paragraph, the reader understands that everything discussed in the essay will come back to those core ideas. When Baldwin talks about his experience with a white teacher taking an interest in him and his father’s resistance to that, he is also talking about race and his father’s death. When he talks about his father’s death, he is also talking about his views on race. When he talks about his encounters with segregation and racism, he is talking, in part, about his father.

Because his father was a hard, uncompromising man, Baldwin struggles to reconcile the knowledge that his father was right about many things with his desire to not let that hardness consume him, as well.

Baldwin doesn’t explicitly state any of this, but his writing so often touches on the same motifs that it becomes clear he wants us to think about all these ideas in conversation with one another.

At the end of the essay, Baldwin makes it more clear:

This fight begins, however, in the heart and it had now been laid to my charge to keep my own heart free of hatred and despair. This intimation made my heart heavy and, now that my father was irrecoverable, I wished that he had been beside me so that I could have searched his face for the answers which only the future would give me now.

Here, Baldwin ties together the themes and motifs into one clear statement: that he must continue to fight and recognize injustice, especially racial injustice, just as his father did. But unlike his father, he must do it beginning with himself—he must not let himself be closed off to the world as his father was. And yet, he still wishes he had his father for guidance, even as he establishes that he hopes to be a different man than his father.

In this essay, Baldwin loads the front of the essay with his motifs, and, through his narrative, weaves them together into a theme. In the end, he comes to a conclusion that connects all of those things together and leaves the reader with a lasting impression of completion—though the elements may have been initially disparate, in the end everything makes sense.

You can replicate this tactic of introducing seemingly unattached ideas and weaving them together in your own essays. By introducing those motifs, developing them throughout, and bringing them together in the end, you can demonstrate to your reader how all of them are related. However, it’s especially important to be sure that your motifs and clear and consistent throughout your essay so that the conclusion feels earned and consistent—if not, readers may feel mislead.

5 Key Tips for Writing Narrative Essays

Narrative essays can be a lot of fun to write since they’re so heavily based on creativity. But that can also feel intimidating—sometimes it’s easier to have strict guidelines than to have to make it all up yourself. Here are a few tips to keep your narrative essay feeling strong and fresh.

Develop Strong Motifs

Motifs are the foundation of a narrative essay . What are you trying to say? How can you say that using specific symbols or events? Those are your motifs.

In the same way that an argumentative essay’s body should support its thesis, the body of your narrative essay should include motifs that support your theme.

Try to avoid cliches, as these will feel tired to your readers. Instead of roses to symbolize love, try succulents. Instead of the ocean representing some vast, unknowable truth, try the depths of your brother’s bedroom. Keep your language and motifs fresh and your essay will be even stronger!

Use First-Person Perspective

In many essays, you’re expected to remove yourself so that your points stand on their own. Not so in a narrative essay—in this case, you want to make use of your own perspective.

Sometimes a different perspective can make your point even stronger. If you want someone to identify with your point of view, it may be tempting to choose a second-person perspective. However, be sure you really understand the function of second-person; it’s very easy to put a reader off if the narration isn’t expertly deployed.

If you want a little bit of distance, third-person perspective may be okay. But be careful—too much distance and your reader may feel like the narrative lacks truth.

That’s why first-person perspective is the standard. It keeps you, the writer, close to the narrative, reminding the reader that it really happened. And because you really know what happened and how, you’re free to inject your own opinion into the story without it detracting from your point, as it would in a different type of essay.

Stick to the Truth

Your essay should be true. However, this is a creative essay, and it’s okay to embellish a little. Rarely in life do we experience anything with a clear, concrete meaning the way somebody in a book might. If you flub the details a little, it’s okay—just don’t make them up entirely.

Also, nobody expects you to perfectly recall details that may have happened years ago. You may have to reconstruct dialog from your memory and your imagination. That’s okay, again, as long as you aren’t making it up entirely and assigning made-up statements to somebody.

Dialog is a powerful tool. A good conversation can add flavor and interest to a story, as we saw demonstrated in David Foster Wallace’s essay. As previously mentioned, it’s okay to flub it a little, especially because you’re likely writing about an experience you had without knowing that you’d be writing about it later.

However, don’t rely too much on it. Your narrative essay shouldn’t be told through people explaining things to one another; the motif comes through in the details. Dialog can be one of those details, but it shouldn’t be the only one.

Use Sensory Descriptions

Because a narrative essay is a story, you can use sensory details to make your writing more interesting. If you’re describing a particular experience, you can go into detail about things like taste, smell, and hearing in a way that you probably wouldn’t do in any other essay style.

These details can tie into your overall motifs and further your point. Woolf describes in great detail what she sees while watching the moth, giving us the sense that we, too, are watching the moth. In Wallace’s essay, he discusses the sights, sounds, and smells of the Illinois State Fair to help emphasize his point about its strangeness. And in Baldwin’s essay, he describes shattered glass as a “wilderness,” and uses the feelings of his body to describe his mental state.

All these descriptions anchor us not only in the story, but in the motifs and themes as well. One of the tools of a writer is making the reader feel as you felt, and sensory details help you achieve that.

What’s Next?

Looking to brush up on your essay-writing capabilities before the ACT? This guide to ACT English will walk you through some of the best strategies and practice questions to get you prepared!

Part of practicing for the ACT is ensuring your word choice and diction are on point. Check out this guide to some of the most common errors on the ACT English section to be sure that you're not making these common mistakes!

A solid understanding of English principles will help you make an effective point in a narrative essay, and you can get that understanding through taking a rigorous assortment of high school English classes !

Melissa Brinks graduated from the University of Washington in 2014 with a Bachelor's in English with a creative writing emphasis. She has spent several years tutoring K-12 students in many subjects, including in SAT prep, to help them prepare for their college education.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Definition and Examples of Narratives in Writing

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

The definition of narrative is a piece of writing that tells a story, and it is one of four classical rhetorical modes or ways that writers use to present information. The others include an exposition, which explains and analyzes an idea or set of ideas; an argument, which attempts to persuade the reader to a particular point of view; and a description, a written form of a visual experience.

Key Takeaways: Narrative Definition

- A narrative is a form of writing that tells a story.

- Narratives can be essays, fairy tales, movies, and jokes.

- Narratives have five elements: plot, setting, character, conflict, and theme.

- Writers use narrator style, chronological order, a point of view, and other strategies to tell a story.

Telling stories is an ancient art that started long before humans invented writing. People tell stories when they gossip, tell jokes, or reminisce about the past. Written forms of narration include most forms of writing: personal essays, fairy tales, short stories, novels, plays, screenplays, autobiographies, histories, even news stories have a narrative. Narratives may be a sequence of events in chronological order or an imagined tale with flashbacks or multiple timelines.

Narrative Elements

Every narrative has five elements that define and shape the narrative: plot, setting, character , conflict , and theme. These elements are rarely stated in a story; they are revealed to the readers in the story in subtle or not-so-subtle ways, but the writer needs to understand the elements to assemble her story. Here's an example from "The Martian," a novel by Andy Weir that was made into a film:

- The plot is the thread of events that occur in a story. Weir's plot is about a man who gets accidentally abandoned on the surface of Mars.

- The setting is the location of the events in time and place. "The Martian" is set on Mars in the not-too-distant future.

- The characters are the people in the story who drive the plot, are impacted by the plot, or may even be bystanders to the plot. The characters in "The Martian" include Mark Watney, his shipmates, the people at NASA resolving the issue, and even his parents who are only mentioned in the story but still are impacted by the situation and in turn impact Mark's decisions.

- The conflict is the problem that is being resolved. Plots need a moment of tension, which involves some difficulty that requires resolution. The conflict in "The Martian" is that Watney needs to figure out how to survive and eventually leave the planet's surface.

- Most important and least explicit is the theme . What is the moral of the story? What does the writer intend the reader to understand? There are arguably several themes in "The Martian": the ability of humans to overcome problems, the stodginess of bureaucrats, the willingness of scientists to overcome political differences, the dangers of space travel, and the power of flexibility as a scientific method.

Setting Tone and Mood

In addition to structural elements, narratives have several styles that help move the plot along or serve to involve the reader. Writers define space and time in a descriptive narrative, and how they choose to define those characteristics can convey a specific mood or tone.