The Invention of Paper Money

History of Chinese Currency

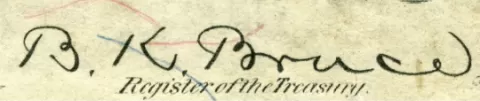

- Figures & Events

- Southeast Asia

- Middle East

- Central Asia

- Asian Wars and Battles

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- Ph.D., History, Boston University

- J.D., University of Washington School of Law

- B.A., History, Western Washington University

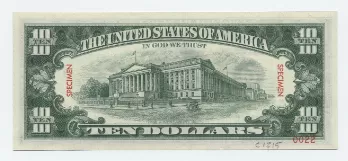

Paper money is an invention of the Song Dynasty in China in the 11th century CE, nearly 20 centuries after the earliest known use of metal coins. While paper money was certainly easier to carry in large amounts, using paper money had its risks: counterfeiting and inflation.

Earliest Money

The earliest known form of money is also from China, a cast copper coin from the 11th century BCE, which was found in a Shang Dynasty tomb in China. Metal coins, whether made from copper, silver, gold, or other metals, have been used across the globe as units of trade and value. They have advantages—they are durable, difficult to counterfeit, and they hold intrinsic value. The big disadvantage? If you have very many of them, they get heavy.

For a couple thousand years after the coins were buried in that Shang tomb, however, merchants, traders, and customers in China had to put up with carrying coins, or with bartering goods for other goods directly. Copper coins were designed with square holes in the middle so that they could be carried on a string. For large transactions, traders calculated the price as the number of coin strings. It was workable, but an unwieldy system at best.

Paper Money Takes the Load Off

During the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), however, merchants began to leave those heavy strings of coins with a trustworthy agent, who would record how much money the merchant had on deposit on a piece of paper. The paper, a sort of promissory note, could then be traded for goods, and the seller could go to the agent and redeem the note for the strings of coins. With trade renewed along the Silk Road, this simplified cartage considerably. These privately-produced promissory notes were still not true paper currency, however.

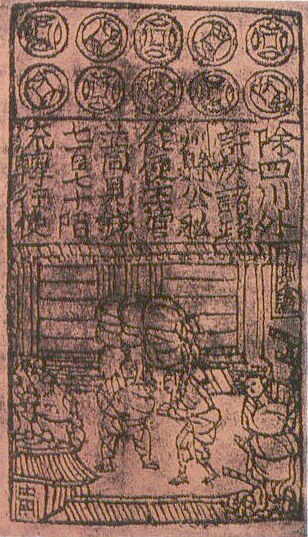

At the beginning of the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), the government licensed specific deposit shops where people could leave their coins and receive notes. In the 1100s, Song authorities decided to take direct control of this system, issuing the world's first proper, government-produced paper money. This money was called jiaozi .

Jiaozi under the Song

The Song established factories to print paper money with woodblocks, using six colors of ink. The factories were located in Chengdu, Hangzhou, Huizhou, and Anqi, and each used different fiber mixes in their paper to discourage counterfeiting. Early notes expired after three years, and could only be used in particular regions of the Song Empire.

In 1265, the Song government introduced a truly national currency, printed to a single standard, usable across the empire, and backed by silver or gold. It was available in denominations between one and one hundred strings of coins. This currency lasted only nine years, however, because the Song Dynasty tottered, falling to the Mongols in 1279.

Mongol Influence

The Mongol Yuan Dynasty , founded by Kublai Khan (1215–1294), issued its own form of paper currency called chao; the Mongols brought it to Persia where it was called djaou or djaw . The Mongols also showed it to Marco Polo (1254–1324) during his 17-year-long stay in Kublai Khan's court, where he was amazed by the idea of government-backed currency. However, the paper money was not backed by gold or silver. The short-lived Yuan Dynasty printed increasing amounts of the currency, leading to runaway inflation. This problem was unresolved when the dynasty collapsed in 1368.

Although the succeeding Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) also began by printing unbacked paper money, it suspended the program in 1450. For much of the Ming era, silver was the currency of choice, including tons of Mexican and Peruvian ingots brought to China by Spanish traders. Only in the last two, desperate years of Ming rule did the government print paper money, as it attempted to fend off the rebel Li Zicheng and his army. China did not print paper money again until the 1890s when the Qing Dynasty began producing yuan .

- Lande, Lawrence, and T. I. M. Congdon. " John Law and the Invention of Paper Money. " RSA Journal 139.5414 (1991): 916–28. Print.

- Lui, Francis T. " Cagan's Hypothesis and the First Nationwide Inflation of Paper Money in World History. " Journal of Political Economy 91.6 (1983): 1067–74. Print.

- Pickering, John. " The History of Paper Money in China ." Journal of the American Oriental Society 1.2 (1844): 136–42. Print.

- What Was the Yuan Dynasty?

- Biography of Kublai Khan, Ruler of Mongolia and Yuan China

- Emperors of China's Yuan Dynasty

- Understanding Economics: Why Does Paper Money Have Value?

- Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire

- The Greatest Chinese Inventions

- The Ashikaga Shogunate

- Finding Cathay

- Who Are the Manchu?

- Biography of Marco Polo, Famous Explorer

- Definition of Greenbacks

- Chinese History Timeline

- Biography of Marco Polo, Merchant and Explorer

- The Dynasties of Ancient China

- The History of Foot Binding in China

- The Mongol Invasions of Japan

- Corrections

How Did Paper Money Develop in the Premodern World?

Paper money was created during China’s Song Dynasty, based upon ancient economic ideas and medieval inventions, which combined to create the world’s first paper currency.

Paper money (also banknote or bill) was first invented in China’s Song Dynasty (CE 960-1279) after a long process that can be traced back to the 3rd century BCE. Eventually, coin currency became too cumbersome and devalued, so various economists, philosophers, and emperors looked for answers. By the medieval era, the Chinese had developed new technologies, as well as different ways of visualizing money, which allowed them to develop the world’s first paper money. The following is an examination of the process that led to the emergence of paper money in medieval China.

Before Paper Money

The development of paper money was the result of a long process that began centuries earlier, thousands of miles away in the Near East. The Lydians were the first people to mint state supported coined currency in the 7th century BCE, and shortly after others followed. The Achaemenid Persians, Greeks, and Romans all developed coined currency from silver, gold, bronze, and copper, which provided the basis for the economies of medieval Europe and the Middle East. But as coined currency was being developed in the West, it was also flourishing independently in the East.

The Mauryan dynasty of India (c. 321-185 BCE), the Qin dynasty of China (221-206 BCE), and the Han dynasty of China (206 BCE-CE 220) were the earliest and most successful Asian states to utilize coined currency. These states disseminated the idea of coined currency throughout southern and eastern Asia, helping to prepare the continent for the eventual development of paper money. It was in late antiquity when the economic ideas of the West and East finally met along the Silk Road , which proved to be another major step in the development of money.

The Silk Road and Coined Currency

The Silk Road was actually a series of overland and sea routes that connected east Asia with the Middle East and Europe. The first Silk Road system existed from the late-2nd century BCE to the mid-3rd century CE, which was responsible for moving goods, ideas, and people. The first Silk Road system included the states of Han China, Parthian Persia, Rome, and the Kushan Empire . Among those states, the Kushan Empire is often overlooked, but its leaders played an important role in the development of coin and paper currency.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

All four of the major Silk Road states used copper, bronze, gold, and silver coins, but they used different systems of weights. A Roman, Kushan, Parthian, and Han silver coin may have looked similar, but because they often had different weights their inherent values were different. This situation could and did cause problems for long-distance merchants who wanted to trade coins of one empire for another. The Kushan rulers came up with a simple yet effective way to convert one trade or convert currencies by introducing a Kushan coin that was based on the Roman weight standard . Ideas such as this would percolate throughout the late ancient and early medieval worlds, ultimately leading to the creation of paper money and monetary standardization.

Chinese Coined Currency

As coined currency developed in China, it looked physically different than coinage in other locations. The Han and Qin authorities developed a method of standardization known as “strings” or guan . In this system, 1,000 bronze coins with square holes were threaded together to create one “string” or guan , making it the currency standard of ancient China . The guan standard was codified in the Tang dynasty (CE 618-907), but during that time the Chinese economy moved closer to paper money.

The first use of paper banknotes, known as “flying cash,” was in the early 800s between provinces. This was because, although the guan was the standard of the Tang government, different regional coins were still used. Originally, flying cash was just used by provincial officials, but it was also later permitted for merchant use . The evolution to paper money was well underway when the Song dynasty came to power, but other conditions still needed to be met.

The Transition to Paper Money in the Song

The Emperor Taizu (ruled CE 960-976) further standardized China’s coin currency across all regions by eliminating existing regional coins. The new, standardized coin became known as the Song yuan tongbao (primary circulating treasure of the Song), but it quickly encountered problems. By 1080 there were five million strings of the Song yuan tongbao in circulation, which itself was probably too much. Lead was added to the high number of bronze-coined currency circulating in the Song economy, which created crippling inflation . The otherwise prosperous and stable Song economy began to teeter, so forward-thinking leaders looked to paper for a solution.

In addition to the devaluation of the coined currency, a number of other factors, some practical and some philosophical, led to the use of paper money. First, the high demand for bronze, copper, and iron created a dearth of materials to make coins. Iron and copper were needed to make weapons and tools for the expanding Song Empire, and bronze is an alloy derived partially from copper. As the Chinese began using these commodities for things other than coinage, they began to view the concept of money differently. Song officials and philosophers began to see money not so much for the value of the token itself, but as a means of payment and exchange . Once this view was accepted, then the transition to paper currency was inevitable.

The transition to paper money would not have been possible without the proper technology. The invention of the movable type press, probably by Bi Shen in the 1040s, combined with the existing knowledge of paper making, made paper money a reality . Unfortunately, no samples of the earliest paper currency notes survive, although texts from the era describe how they were made and what they looked like. The notes were made through multiple impressions of three colors: red, black, and blue. The notes were marked by their value and decorated with narrative scenes and iconic emblems of the era .

One interesting element of early paper currency in China that may have been a component of both its success and failure was its decentralization. A number of different paper currencies were issued during the Song dynasty, with no single currency existing until the final decade of the dynasty. Instead, there were several “currency zones” throughout the empire, where regional officials would issue their own currencies that were authorized by the emperor. The earliest paper currency used was the jiaozi in Sichuan, which proved to be quite successful. In 1160, the paper currency known as the huizi was first issued by Goazong (ruled 1127-1162), the first emperor of the Southern Song dynasty. The huizi would become the most important and widespread of all paper currencies.

The huizi was far ahead of its time in many ways. The emperor issued each series of the note with fixed terms of expiration to fight inflation and lessen the effects of counterfeiting. Between 1168 and 1264 the Southern Song emperors issued eighteen series of the huizi . The Song central economy planners tied the huizi to the coined currency still active, with one huizi equaling one guan . Later, smaller paper denominations were printed that equaled partial strings of 200, 300, and 500 coins . The huizi was backed by silver , so the value of printed notes was theoretically not supposed to surpass the value of the silver supply. The Song leaders eventually printed more money than the value of the silver supply, devaluing the currency and creating inflation.

Early Paper Money Elsewhere

The primary rival of the early Song dynasty was the Jurchen Jin dynasty in northeastern China. The Jurchens eventually forced their way into Song territory, conquering northern China and vanquishing the Song dynasty to southern China. From 1127 to 1234 the Jurchens ruled northern China, following a policy of cultural and economic continuity from the Song. The Jurchens issued paper money notes beginning in the mid-1150s based on the Song notes originally issued in the Sichuan zone . The concept of paper money was then inherited when the Mongols conquered China and established the Yuan dynasty in 1271. As these advances in paper currency were taking place in the East, the West was lagging far behind, although some innovations were taking place there as well.

The legendary crusader military order, Knights Templar , were the first people to develop a proto-paper money in Europe. Churches throughout western Europe served as banks for the Templars, who serviced knights and other pilgrims who traveled to the Holy Land during the Crusades in the 13th century. The process worked in the following manner. A pilgrim would deposit his funds at a church or Templar castle in Europe, be given a paper note, and would then make the long journey. Once the pilgrim arrived in the Holy Land, he simply redeemed the note for coined currency , minus a small service charge. Although the Templars initially avoided charges of usury by not charging interest, they were still subjected to the Inquisition in 1312. The idea of paper money in Europe temporarily died with the Inquisition, but it was likely revived by the Silk Road when European merchants came into contact with Mongol paper money, later bringing the idea back to Europe. By the late High Middle Ages the idea of coined and paper currency had come full circle along the Silk Road.

Qin Shi Huangdi: The Man Who Gave His Name to China

By Jared Krebsbach PhD History, MA Art History, BA History Jared is a fulltime freelancer with a background in history. His work has been published in academic journals as well as popular magazines, blogs, and websites. Historical interests include cyclical history, religious history, and economics.

Frequently Read Together

What Was the Silk Road & What Was Traded on It?

The 4 Powerful Empires of the Silk Road

China’s Tang Dynasty: A Cosmopolitan Golden Age

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Invention of Money

By John Lanchester

When the Venetian merchant Marco Polo got to China, in the latter part of the thirteenth century, he saw many wonders—gunpowder and coal and eyeglasses and porcelain. One of the things that astonished him most, however, was a new invention, implemented by Kublai Khan, a grandson of the great conqueror Genghis. It was paper money, introduced by Kublai in 1260. Polo could hardly believe his eyes when he saw what the Khan was doing:

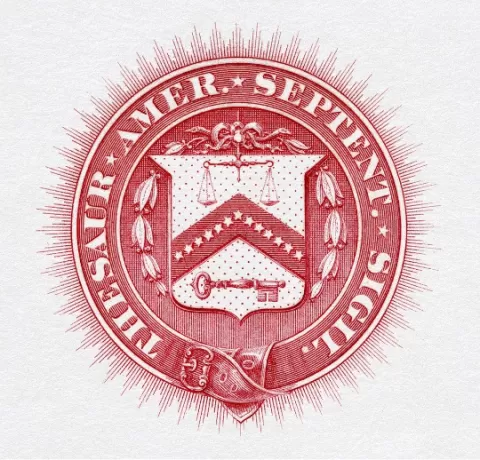

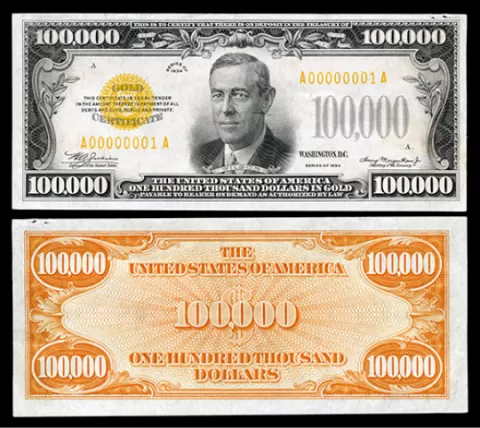

He makes his money after this fashion. He makes them take of the bark of a certain tree, in fact of the mulberry tree, the leaves of which are the food of the silkworms, these trees being so numerous that whole districts are full of them. What they take is a certain fine white bast or skin which lies between the wood of the tree and the thick outer bark, and this they make into something resembling sheets of paper, but black. When these sheets have been prepared they are cut up into pieces of different sizes. All these pieces of paper are issued with as much solemnity and authority as if they were of pure gold or silver; and on every piece a variety of officials, whose duty it is, have to write their names, and to put their seals. And when all is prepared duly, the chief officer deputed by the Khan smears the seal entrusted to him with vermilion, and impresses it on the paper, so that the form of the seal remains imprinted upon it in red; the money is then authentic. Anyone forging it would be punished with death.

That last point was deeply relevant. The problem with many new forms of money is that people are reluctant to adopt them. Genghis Khan’s grandson didn’t have that difficulty. He took measures to insure the authenticity of his currency, and if you didn’t use it—if you wouldn’t accept it in payment, or preferred to use gold or silver or copper or iron bars or pearls or salt or coins or any of the older forms of payment prevalent in China—he would have you killed. This solved the question of uptake.

Marco Polo was right to be amazed. The instruments of trade and finance are inventions, in the same way that creations of art and discoveries of science are inventions—products of the human imagination. Paper money, backed by the authority of the state, was an astonishing innovation, one that reshaped the world. That’s hard to remember: we grow used to the ways we pay our bills and are paid for our work, to the dance of numbers in our bank balances and credit-card statements. It’s only at moments when the system buckles that we start to wonder why these things are worth what they seem to be worth. The credit crunch in 2008 triggered a panic when people throughout the financial system wondered whether the numbers on balance sheets meant what they were supposed to mean. As a direct response to the crisis, in October, 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto, whoever he or she or they might be, published the white paper that outlined the idea of Bitcoin , a new form of money based on nothing but the power of cryptography.

The quest for new forms of money hasn’t gone away. In June of this year, Facebook unveiled Libra, global currency that draws on the architecture of Bitcoin. The idea is that the value of the new money is derived not from the imprimatur of any state but from a combination of mathematics, global connectedness, and the trust that resides in the world’s biggest social network. That’s the plan, anyway. How safe is it? How do we know what libras or bitcoins are worth, or whether they’re worth anything? Satoshi Nakamoto’s acolytes would immediately turn those questions around and ask, How do you know what the cash in your pocket is worth?

The present moment in financial invention therefore has some similarities with the period when money in the form we currently understand it—a paper currency backed by state guarantees—was first created. The hero of that origin story is the nation-state. In all good stories, the hero wants something but faces an obstacle. In the case of the nation-state, what it wants to do is wage war, and the obstacle it faces is how to pay for it.

The modern system for dealing with this problem arose in England during the reign of King William, the Protestant Dutch royal who had been imported to the throne of England in 1689, to replace the unacceptably Catholic King James II. William was a competent ruler, but he had serious baggage—a long-running dispute with King Louis XIV of France. Before long, England and France were involved in a new phase of this dispute, which now seems part of a centuries-long conflict between the two countries, but at the time was variously called the Nine-Years’ War or King William’s War. This war presented the usual problem: how could the nations afford it?

King William’s administration came up with a novel answer: borrow a huge sum of money, and use taxes to pay back the interest over time. In 1694, the English government borrowed 1.2 million pounds at a rate of eight per cent, paid for by taxes on ships’ cargoes, beer, and spirits. In return, the lenders were allowed to incorporate themselves as a new company, the Bank of England. The bank had the right to take in deposits of gold from the public and—a second big innovation—to print “Bank notes” as receipts for the deposits. These new deposits were then lent to the King. The banknotes, being guaranteed by the deposits, were as good as gold money, and rapidly became a generally accepted new currency.

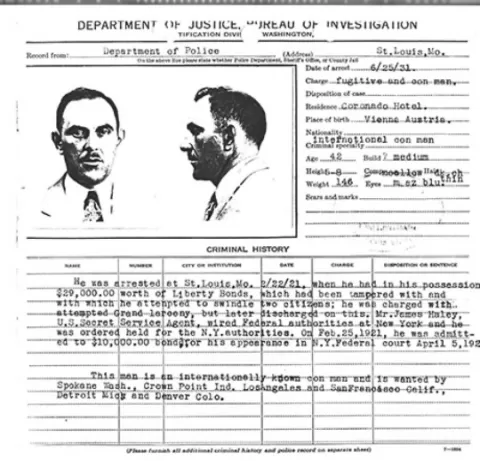

This system is still with us, and not just in England. The more general adoption of the scheme, however, was not a story of uninterrupted success. Some of the difficulties are recounted in James Buchan’s fascinating “ John Law: A Scottish Adventurer of the Eighteenth Century .” Law was the Edinburgh-born son of a goldsmith turned banker. He moved to London in 1692, where he observed the wondrous new scheme of government paid for by long-term debt and paper money. One of the most significant effects of the paper money was the way it stimulated borrowing and lending—and trading. Law had an instinctive understanding of finance and a love of risk, and it is tempting to wonder what would have happened if he had lent his services to the English government. Instead, on April 9, 1694, a different fate was set in motion. He killed a man in a duel, or brawl—the distinction, as Buchan explains, was not all that clear. “Duels then were not the tournaments of the Middle Ages or the affairs of honour of later years, governed by written codes of conduct and discharged at dawn with pistols in some snowy forest clearing,” he writes. They might be conducted “with rapiers or short swords in hot or barely cooling blood, sometimes with seconds drawn and fighting, and shading away into assassination and armed robbery.” Law was sent to prison to await a murder trial. He used his connections to get out, as prisoners of means did, and fled abroad as an outlaw.

Law spent the next few years knocking around Europe, learning about gambling and finance, and writing a short book, “Money and Trade Considered,” which in many respects foreshadows modern theories about money. He became rich; like Littlefinger in “Game of Thrones,” Law seems to have been one of those men who had the knack of “rubbing two golden dragons together and breeding a third.” He bought a fancy house in The Hague and made a close study of the many Dutch innovations in finance, such as options trading and short selling. In 1713, he arrived in France, which was beset by a problem he was well suited to tackle.

The King of France, Louis XIV, was the preëminent monarch in Europe, but his government was crippled by debt. The usual costs of warfare were added to a huge bill for annuities—lifelong interest payments made in settlement of old loans. By 1715, the King had a hundred and sixty-five million livres in revenue from taxes and customs. Buchan does the math: “Spending on the army, the palaces and court and the public administration left just 48 million livres to meet interest payments on the debts accumulated by the illustrious kings who had gone before.” Unfortunately, the annual bill for annuities and wages of lifetime offices came to ninety million livres. There were also outstanding promissory notes, amounting to nine hundred million livres, left over from various wars; the King wouldn’t be able to borrow any more money unless he paid interest on those notes, and that would cost an additional fifty million livres a year. The government of France was broke.

In September of 1715, Louis XIV died, and his nephew the Duke of Orleans was left in charge of the country, as regent to the child king Louis XV. The Duke was quite something. “He was born bored,” the great diarist Saint-Simon, a friend of the Duke’s since childhood, observed. “He could not live except in a sort of torrent of business, at the head of an army, or in managing its supply, or in the blare and sparkle of a debauch.” Facing the financial crisis of the French state, the Duke started listening to the ideas of John Law. Those ideas—more or less orthodox policy today—were wildly original by the standards of the eighteenth century.

Law thought that the important thing about money wasn’t its inherent value; he didn’t believe it had any. “Money is not the value for which goods are exchanged, but the value by which they are exchanged,” he wrote. That is, money is the means by which you swap one set of stuff for another set of stuff. The crucial thing, Law thought, was to get money moving around the economy and to use it to stimulate trade and business. As Buchan writes, “Money must be turned to the service of trade, and lie at the discretion of the prince or parliament to vary according to the needs of trade. Such an idea, orthodox and even tedious for the past fifty years, was thought in the seventeenth century to be diabolical.”

This idea of Law’s led him to the idea of a new national French bank that took in gold and silver from the public and lent it back out in the form of paper money. The bank also took deposits in the form of government debt, cleverly allowing people to claim the full value of debts that were trading at heavy discounts: if you had a piece of paper saying the king owed you a thousand livres, you could get only, say, four hundred livres in the open market for it, but Law’s bank would credit you with the full thousand livres in paper money. This meant that the bank’s paper assets far outstripped the actual gold it had in store, making it a precursor of the “fractional-reserve banking” that’s normal today. Law’s bank had, by one estimate, about four times as much paper money in circulation as its gold and silver reserves. That is conservative by modern banking standards. A U.S. bank with assets under a hundred and twenty-four million dollars is obliged to keep a cash reserve of only three per cent.

Link copied

The new paper money had an attractive feature: it was guaranteed to trade for a specific weight of silver, and, unlike coins, could not be melted down or devalued. Before long, the banknotes were trading at more than their value in silver, and Law was made Controller General of Finances, in charge of the entire French economy. He also persuaded the government to grant him a monopoly of trade with the French settlements in North America, in the form of the Mississippi Company. He funded the company the same way he had funded the bank, with deposits from the public swapped for shares. He then used the value of those shares, which rocketed from five hundred livres to ten thousand livres, to buy up the debts of the French King. The French economy, based on all those rents and annuities and wages, was swept away and replaced by what Law called his “new System of Finance.” The use of gold and silver was banned. Paper money was now “fiat” currency, underpinned by the authority of the bank and nothing else. At its peak, the company was priced at twice the entire productive capacity of France. As Buchan points out, that is the highest valuation any company has ever achieved anywhere in the world.

It ended in disaster. People started to wonder whether these suddenly lucrative investments were worth what they were supposed to be worth; then they started to worry, then to panic, then to demand their money back, then to riot when they couldn’t get it. Gold and silver were reinstated as money, the company was dissolved, and Law was fired, after a hundred and forty-five days in office. In 1720, he fled the country, ruined. He moved from Brussels to Copenhagen to Venice to London and back to Venice, where he died, broke, in 1729.

The great irony of Law’s life is that his ideas were, from the modern perspective, largely correct. The ships that went abroad on behalf of his great company began to turn a profit. The auditor who went through the company’s books concluded that it was entirely solvent—which isn’t surprising, when you consider that the lands it owned in America now produce trillions of dollars in economic value.

Today, we live in a version of John Law’s system. Every state in the developed world has a central bank that issues paper money, manipulates the supply of credit in the interest of commerce, uses fractional-reserve banking, and features joint-stock companies that pay dividends. All of these were brought to France, pretty much simultaneously, by John Law. His great and probably unavoidable mistake was to underestimate the volatility that his inventions introduced, especially the risks created by runaway credit. His period of brilliant success in France left only two monuments. One was created by the Duke of Bourbon, who cashed out his shares in the company and used the windfall to build the Great Stables at Chantilly. “John Law had dreamed of a well-nourished working population and magazines of home and foreign goods,” Buchan notes. “His monument is a cathedral to the horse.” His other legacy is the word “millionaire,” first coined in Paris to describe the early beneficiaries of Law’s dazzling scheme.

How did these once wild ideas become part of the very fabric of modern finance and government? Trial and error. It was not the case that smart people figured everything out at once and implemented it simultaneously, as Law tried to do. The modern economic system evolved, and evolution involves innovations, repetitions, failures, and dead ends. In finance, it involves busts and panics and crashes, because, as James Grant says in his lively new biography of the Victorian banker-journalist Walter Bagehot, “in finance and economics, we keep stepping on the same rakes.”

Bagehot (pronounced “badge-it”) knew all about those rakes. He grew up in the West of England in a family with strong links to a well-run local bank, Stuckey’s. After going to university and trying his hand at being a lawyer, he turned to journalism and to banking, the latter career paying for the former. He married the daughter of James Wilson, who had founded The Economist , in 1843—Bagehot became its third editor—and lived a life that was, from the outside, fairly uneventful. The interest in Bagehot comes from his dazzling, witty, paradox-loving writing, and in particular from his two key works, “ The English Constitution ” (1867), which sums up the unwritten order of Great Britain’s political institutions, and “ Lombard Street ” (1873), which explains how banking works. These books are still readable today, but they were of interest mainly to wonks until Ben Bernanke name-checked Bagehot as a crucial influence on the thinking behind the 2008 bank bailouts. That caused a revived interest, which led to the writing of Grant’s “ Walter Bagehot: The Life and Times of the Greatest Victorian .”

“Greatest” is a loaded word, especially since Grant—who is, among other things, the founder of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer —makes it clear that Bagehot was an unashamed misogynist and racist (“There are breeds in the animal man just as in the animal dog”) and an accomplished hypocrite. The last quality was useful from the journalistic point of view; Bagehot was brilliant at swapping sides without ever admitting that he had changed his mind. A Confederate victory in the Civil War, for instance, was “a certain fact,” and President Lincoln was “dishonest and foolish,” a settled view that didn’t preclude Bagehot from declaring, once the Union had prevailed, that “panic did not for a moment unnerve the iron courage of the American democracy.” His subsequent elegy for Lincoln is a genuinely lovely piece of writing: “Difficulties, instead of irritating him as they do most men, only increased his reliance on patience; opposition, instead of ulcerating, only made him more tolerant and determined.”

In a sense, this highfalutin hypocrisy and lack of principle is the point of Bagehot. His work on the English constitution focussed on a paradox: the pomp and circumstance of monarchy had an important function, he argued, precisely because the monarch had no real power. Bagehot’s work on banking similarly focussed on the difference between appearances and realities, specifically the gap between the air of solidity and respectability cultivated by Victorian banks and the evident fact that they kept collapsing and going broke. There were huge bank crises in 1797, in 1825, in 1847, and in 1857, all of them caused by the oldest and simplest reason of bankruptcy in finance: lending money to people who can’t pay it back.

In theory, all the money in circulation during the era of Victorian banking was backed up by deposits in gold. One pound in paper money was backed by 123.25 grains of actual gold. In practice, that wasn’t true. There were multiple occasions—usually linked to the cost of that old classic, war with France—when the government suspended the convertibility of paper money to gold. In addition, banks could print their own money. They often didn’t have enough gold to sustain the value of their notes, in the event of customers coming to the bank and demanding conversion. That phenomenon, the dreaded “bank run,” was a direct outcome of the fractional-reserve banking prefigured by John Law. A system in which banks don’t hold cash reserves equivalent to their outstanding loans works fine, unless enough people turn up at the bank and simultaneously want their paper money turned into its metal equivalent. Unfortunately, that kept happening, and banks kept going broke. The issues at stake were the same as those that had shaped the career of John Law, and which are on people’s minds again today: What is money? Where does it derive its value? Who finally guarantees the value of debts and credits?

Bagehot had answers to all those questions. He thought that money, real money, was gold, and gold alone. All the other forms of currency in the system were merely different kinds of credit. Credit was indispensable to a functioning economy, and helped make everybody rich, but in the final analysis only gold was legal tender, according to the strict definition of the term—money that cannot be refused in settlement of a debt. (U.S. currency makes sure you know it is legal tender: it says so right there on the front.) Bagehot loved a paradox, and this was one: all the credit in the system was essential to the economy, but it wasn’t really money, because it wasn’t gold, which underpinned the value of everything else.

So where was all the gold? In the Bank of England. The role of that once private company had evolved. Bagehot thought it was the Bank of England’s job to hold the gold, so that all the smaller banks didn’t have to. Instead, the smaller banks took deposits, made loans, and issued paper money. If they got into trouble—which they tended to do—the big bank would bail them out. Why shouldn’t all the other banks hold their own gold, and take care of their own solvency? Bagehot the banker-writer was completely frank about the reason. “The main source of the profitableness of established banking is the smallness of the requisite capital,” he wrote. The modern way of putting this would be to talk about the bank’s return on equity. The less equity the bank needed to keep as a margin of safety, the more money it could lend, and, therefore, the more profit it could make. Gold was essential in order to guarantee the currency, but the bankers didn’t want it taking up valuable space on their balance sheets. Better to let the government do that, in the form of the Bank of England.

We still have a version of this system, in which government guarantees underpin the profitability of banks. The central bank’s crucial role is to lend money freely at a time of crisis—to be what is called “the lender of last resort.” Grant, who admits to “a libertarian’s biases,” sees this doctrine as the seed of “deposit insurance, the too-big-to-fail doctrine, and the rest of the modern machinery of socialized financial risk.”

Like John Law and Walter Bagehot, I’m the child of a man who worked in a bank, and, as such, I had a banker’s-son question running through my mind as I read Grant’s entertaining book: what happened to Bagehot’s bank? The answer is that Stuckey’s was taken over by another bank, Parr’s, in 1909. Parr’s was part of the larger National Westminster Bank, which was taken over by the Royal Bank of Scotland, in 2000. R.B.S., as it is unaffectionately known in the U.K., grew through takeovers to become, in the early years of this century, the biggest company in the world, as measured by the size of its balance sheet. Then came the credit crunch, and the moment—the latest version of the old familiar one—when things turned out not to be worth what they were supposed to be worth. The biggest bank in the world came, according to its chairman, to within “a couple of hours” of complete collapse. The outcome was a huge bailout, and the nationalization of R.B.S., with costs to the British taxpayer of forty-five billion pounds. Not much about that story would have surprised John Law or Walter Bagehot. Maybe, though, both men—the man who almost bankrupted a country and the supreme advocate of bankers’ bailouts—would be amused to see just how little we have learned. As for the question of what to do about the bankers responsible for the crash, Kublai Khan would probably have had some ideas. ♦

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Nathan Heller

By Joshua Davis

By Gideon Lewis-Kraus

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Become an FT subscriber

Limited time offer save up to 40% on standard digital.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

- Special features

- FirstFT newsletter

- Videos & Podcasts

- Android & iOS app

- FT Edit app

- 10 gift articles per month

Explore more offers.

Standard digital.

- FT Digital Edition

Premium Digital

Print + premium digital.

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Cancel anytime during your trial.

- 10 additional gift articles per month

- Global news & analysis

- Exclusive FT analysis

- Videos & Podcasts

- FT App on Android & iOS

- Everything in Standard Digital

- Premium newsletters

- Weekday Print Edition

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- Everything in Print

- Everything in Premium Digital

The new FT Digital Edition: today’s FT, cover to cover on any device. This subscription does not include access to ft.com or the FT App.

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

International Edition

The History of Paper Money

Last Updated on January 18, 2024

The history of paper money is a history of failed experiments.

Authorities have sought to utilise the flexibility it gives their finances, but have often mismanaged it and brought catastrophe.

While fiat money is the norm today (now mainly digital and not actually physical paper), paper money has been less common in the past. Throughout much of human history, society has used some form of hard money. That is money that is hard to create and thus limited in its supply, such as precious metals like gold or silver.

The Chinese were the first to adopt paper money around 800 AD with the Tang dynasty and their “flying money.”

Paper money then appeared in Europe in 1661 and in America in 1690.

Initially paper money was redeemable for gold and silver and while the paper existed primarily for convenience, the real money was the metal.

However, things changed in the 20th century with the onset of World War One, as the major powers abandoned the gold standard in order to pay for the war through the printing press.

Governments learned that people would accept paper money with no convertibility into gold.

So today we live with a monetary system in which the US dollar is the global reserve currency but with the dollar having no tie to any hard asset. It exists entirely by fiat.

This works as long as the public maintain their confidence in both the soundness of the money and the authorities that issue the money.

How long we stay with the current system depends on how long governments and central banks can keep that confidence.

Read More: A Short History Of Fiat Currency Failures: 9 Currencies That Have Imploded

Table of Contents

What Is Paper Money?

Paper money is a currency where paper notes are used as the medium of exchange. Normally paper money is issued by a government or a central bank but sometimes it may be issued by commercial banks.

Traditionally, money has been some form of commodity, like gold or silver, that has some degree of natural scarcity and where it is quite difficult to increase the supply.

Unlike commodity money, the paper itself has no value but the currency gains value by the trust and confidence market participants give to the issuing authority.

Because the paper has no value, it is very cheap to create and new units can easily be added to the money supply.

The primary reason why paper money has been used throughout history is that it is more convenient than transporting a large amount of precious metals.

As Saifidean Ammous explains in his book The Fiat Standard , it has a high spatial salability. While it may not retain its value over time, it is very effective at transporting value over space.

Paper money is also referred to as fiat money. Fiat is Latin for “let it be done,” meaning that new units of money can easily be created by the issuing authority.

Before the digital era paper money actually meant physical paper. These days only a tiny fraction of the money supply is actually printed as physical cash. Instead most of it only exists as numbers on a screen in digital form. This is the modern day fiat currency which is still referred to by many as paper money.

And when governments and central banks increasing the supply of money it is often referred to as “printing money” even though the vast majority of the new money is digital.

This article on the history of paper money will start with the physical paper going back to the early Chinese paper money and will conclude with a look at modern fiat currency.

The First Paper Money in China

The first instance of paper money being used in China was during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD), which went by the awesome name of feiqian or “flying money.”

Around 800 AD the emperor compelled merchants to leave their cumbersome and heavy hard money in the public vault and issued them with a paper security instead. The security was the “flying money,” aptly named because of its tendency to blow away.

The flying money became a type of currency as it was able to be exchanged amongst the merchants. They were also convertible back into hard currency .

However it wasn’t intended to be used as a currency amongst the wider population and its use was rather limited.

After the Tang Dynasty there was a period of division in China before the Song Dynasty emerged in Southern China. (960-1279).

The Song issued the jiaozi , which were receipts given in exchange for the cumbersome iron money that was in circulation. The jiaozi was representative of an ounce of silver.

The government initially allowed 16 rich families to form a union to issue the jiaozi , before the later deciding to step in and take control themselves in 1024.

The jiaozi was limited to Sichuan and not used widely across the country. It was subject to counterfeiting and suffered from inflation caused by an expanding money supply.

In 1107 the jiaozi was discontinued and replaced with the qianyin.

After 1127 most of Northern China was conquered and the Song Dynasty shrank to almost half its size. The new northern empire, the Jin Dynasty, imitated the Song and issued their own paper currency, the jiaochao.

In 1161 in the now smaller Song empire, a new paper currency, the huizi , was issued. This was used throughout the whole empire with the exception of Sichuan, as they continued to use their own paper currency.

After initially controlling the money supply tightly, financial pressure and war caused the Song government to pursue an inflationary policy, beginning the first nationwide inflation in history.

The Mongols, who had already started using paper currency themselves, then took over China between 1279 and 1367 in what is know as the Yuan Dynasty. As the rulers of China they continued to use paper currency, also know as the jiaochao.

The first jiaochao issue was backed by silk and the second issue backed by silver. Like many great empires they eventually gave into the temptation to debase their currency. This was one of the reasons for the economic difficulties at the end of the Yuan Dynasty and their eventual demise.

The Ming, who succeeded the Mongols, initially continued with paper money before being forced back onto a silver standard . Their successor, the Qing also halted the use of paper money during the early period of their reign, using silver and copper instead.

Paper Money in Europe During The Middle Ages

In Europe in the Middle Ages, money was mostly coins but could also be uncoined precious metals, other valuable commodities or even small squares of cloth.

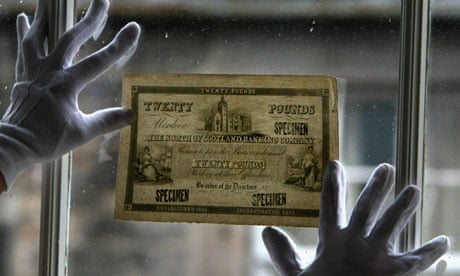

The Italian city states were the first to experiment with paper money. Due to the dangers and inconvenience of moving large amounts of precious metals, they developed a system of promissory notes and bills of exchange.

These were debt instruments written on paper that included the details and terms of repayment.

In some sense these were seen as paper money but they did not circulate as currency.

The Development Of Banknotes In Europe

It wasn’t until the Swedish Riksbank issued notes in 1661 that Europe first started using paper money in the form of bank notes.

Back then, Sweden was a quite a powerful empire.

This issue was initially successful as the notes were redeemable in hard money, however it comes as no surprise that the bank started printing more notes, which led to a reduction in their value and inflation.

Eventually the bank failed and the central banker, Johan Palmstruch, was sentenced to death.

The Bank of England

The Bank of England was established soon after in 1694 as a private bank to provide loans to the government, primarily to fund the Nine Years War against France.

England had been performing poorly in the war and needed money to rebuild her navy. But with a lack of funds and poor credit the government was in a tight spot.

A loan of £1.2 million was provided to the government by a group of over 1200 lenders , with the lenders being given the right to incorporate the Bank of England as a private company with the ability to issue banknotes.

This was much to the frustration of the goldsmiths who had previously fulfilled the role of banker.

One of them, Richard Hoare, presciently commented that the Bank would:

“Engross most of the Ready Money in and near the City of London, which is the Heart of Trade, and so will amount in effect to a Monopoly.”

The Bank quickly evolved beyond its role as banker to the government and later in 1694 began commercial banking, allowing public deposits.

The goldsmith bankers attempted to make a run on the bank in 1696. After they had gathered a sizeable number of notes issued by the bank they simultaneously demanded gold and silver in exchange for the notes. The Bank denied them the gold and silver, although it did pay out to other creditors who weren’t trying to bring the bank to its knees.

Bank of England notes were convertible into gold for much of the banks early history, suspended only in 1745 due to the Jacobite Rising, between 1797 and 1821 to finance the Napoleonic Wars and then again in 1914 as World War One broke out.

Clearly war is bad for sound money.

The Bank of England continued to operate as a private bank until 1946, when it was nationalised by Clement Attlee’s Labour Government.

Paper Money In France

In France, paper money was first introduced by the Scotsman John Law.

Law had to flee his homeland at the age of 23 after killing a man in a duel and spent his time travelling around Europe and developing his monetary theory.

Eventually he ended up in Paris and made the acquaintance of the Duke of Orleans, the regent of the child king Louis XV.

Law believed that credit was like blood. Just as a body needs the circulation of blood to survive, so too society needs the circulation of credit to survive. To him, paper money was far superior to gold and silver. He was a Keynesian long before Keynes.

With the French government deep in debt after the War of Spanish Succession, this argument swayed the Duke and the Banque Generale was established in 1716. It had a limited note issue of 60 million livres and would only issue notes in exchange for gold and silver.

The Duke even mandated that taxes were to be paid with John Law’s banknotes, which gave them the status of government money.

Two years later the bank was reorganised from a private to a public institution and renamed the Banque Royale, with no limit to its right to issue banknotes other than the permission of the Duke.

In the short term, Law’s bank was a wild success, stimulating trade and increasing confidence in the economy. The Duke was impressed with Law.

But like any paper induced inflationary boom the good times wouldn’t last.

In 1717 Law had been allowed to gain a trading monopoly over the French territory of Louisiana, and he established the Mississippi Company. He acquired three other rival trading companies who had rights in China, the East Indies and Africa to give him a monopoly on all of France’s foreign trade.

Law sold shares in the Mississippi company, while at the same time the Banque Royale began issuing more and more bank notes.

This started a speculative mania that resulted in one of history’s most famous bubbles.

The shares started at 500 livres in January 1719, rising to 10,000 livres by December 1719.

A 1900% gain in less than a year.

They would peak at over 18,000 livres.

As investors started taking profits the share price began a precipitous decline. It fell to 2000 livres in September 1720, 1000 livres in December 1720 and by September 1721 the price was back to where it began at 500 livres.

Law had been printing paper money so the company could buy back the stock that other investors were selling. He had hoped this would stabilise the market but it had the opposite effect. All the money printing spooked investors and made them want to sell their shares, get out of paper money and back into gold and silver.

This caused enourmous price inflation in France, at one point the monthly inflation rate reached 23%.

With not enough gold and silver to pay those wanting to convert their paper to hard money, Law, now the Finance Minister as well, made it illegal to hold large amounts of gold and silver, decreed that paper money could no longer be exchanged for hard money and devalued the paper currency by half.

This created a public uproar, causing the Duke to fire Law and place him under house arrest.

As he had done decades earlier, Law fled the country.

Traumatised by the John Law experiment, the French Crown returned to a monetary system based on gold and silver.

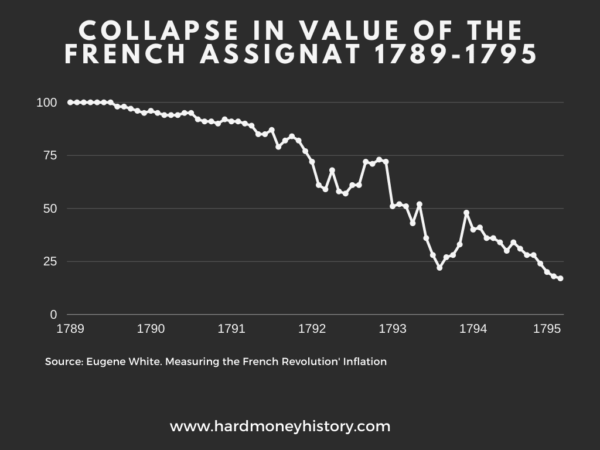

It stayed that way until the beginning of the French Revolution in 1789 when the dire state of the royal finances plunged the country into financial crisis and political chaos.

With tax reform and bankruptcy both politically unacceptable, the new National Assembly tried to solve the financial crisis by issuing paper money, known as the assignat.

The failure of John Law’s system was fresh in their memory, but they made the fateful and arrogant mistake in assuming that if they issued paper money they would be able to control it. They couldn’t and were seduced into issuing more and more paper currency.

The 1790s was a decade of political, economic and social chaos for France as the revolution led to the establishment of a republic, the killing of the king, massive inflation and a reign of political terror.

In 1795, five years after it was first issued, the value of the assignat had collapsed.

Eventually the assignat was abandoned and the silver franc took its place.

Napoleon, who had taken power in a coup in 1799, established the Bank de France in 1800. The bank established a new monetary system with gold and silver coins with the silver/gold ratio set at 15:1.

Read More: The Financial Crisis That Caused the French Revolution

When Did The US Start Using Paper Money?

Before the formation of the United States of America, the 13 British colonies used British money . Britain at the time was on a silver standard.

When British money wasn’t always available, for example in rural areas, commodities were used as media of exchange. For example beaver fur, fish, corn rice and tobacco.

As the colonial economy grew more and more British coins made their way to America, as well as the gold and silver coins of other European nations. These foreign coins freely circulated as money until banned by Congress in 1857.

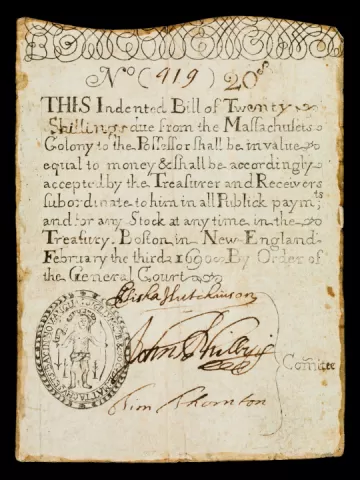

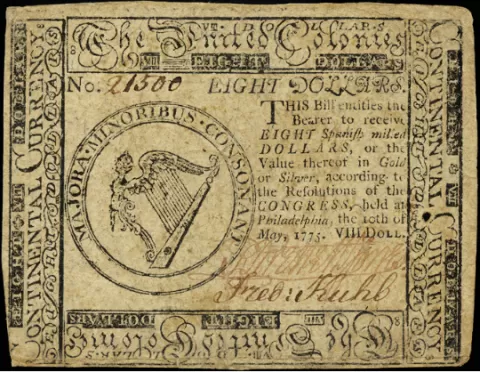

The first paper money in the colonial era was issued by Massachusetts in 1690 as a means to pay their soldiers. When they issued this money they pledged to redeem the notes in gold and silver and also to make no further issuances of paper money.

The government failed to meet both of those obligations.

The first issue was £7000 in 1690, followed by a second issue of £40,000 in 1691. This led to a loss of confidence in the government’s ability to repay in gold and silver, devaluing the paper money by 40%. Prices rose.

In 1711 there was another issue of paper, this time £500,000.

Between 1744 and 1748 the total amount of paper money in circulation exploded from £300,000 to £2.5 million.

Silver traded at 10 times the price it had in 1690 when the paper money was first issued.

By the late 1750s every other colony had followed Massachusetts down the same path, issuing paper currency and experiencing massive inflation.

Things only changed when the British forced the colonies to wean themselves off paper money, passing a law in 1751 for New England and in 1764 for everywhere else, prohibiting new issues of paper money and demanding the gradual withdrawal of existing notes from circulation.

It wouldn’t be long before paper money would make a return.

The Continental

When the Revolutionary War broke out in 1775, the Continental Congress needed a means of financing it.

They decided that an emergency issue of paper money would be the way to go.

There was no promise of redemption for gold and silver. Instead, they promised to retire the notes in seven years and redeem them with future taxes.

In 1775, the money supply was estimated to be $12 million. The Congress issued a staggering $225 million of paper over the next four years.

Between 1775 and 1779 the paper dollars fell in value to the point where 42 paper dollars were needed to purchase 1 dollar in hard money. By 1781 it was 168 paper dollars.

Prices skyrocketed and price controls followed, leading to shortages.

Farmers refused to accept paper money in exchange for goods. The Continental Army just seized the goods instead.

Eventually the state and federal governments allowed the paper currency to depreciate until it was worthless, and all paper money was withdrawn by the end of the war.

Again, it didn’t last long before paper money would make a return.

The Bank of North America

In 1782 the Bank of North America was established. This was a private bank that was modelled on the Bank of England and it was granted a monopoly on the issue of paper money.

This paper money was redeemable in gold and silver but due to the lack of confidence in the bank their notes quickly lost value.

After just a year of operation, the first attempt at a central bank ended with the Bank of North America reverting to a commercial bank and all government debt to the bank being repaid.

With the establishment of the US Constitution, the power to coin money passed to Congress, with state governments prohibited from coining money or issuing paper. The Coinage Act of 1792 established a bimetallic standard with a silver/gold ratio of 15/1.

The Bank of the United States

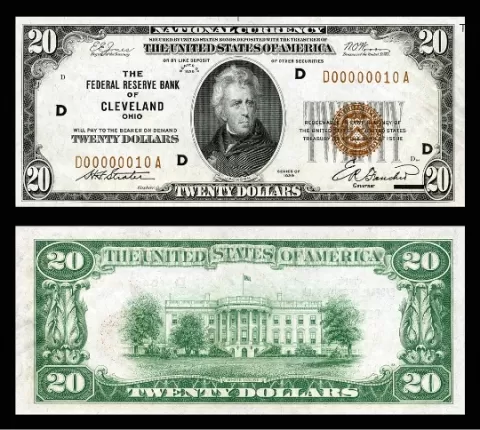

In 1791 a second attempt at a central bank was made with the establishment of the Bank of the United States. This was a private bank, although the Federal Government did own shares. The bank had the right to issue paper money, although this was redeemable for hard money.

The Bank of the United States promptly issued large amounts of paper dollars, triggering a significant rise of prices.

Between 1791 and 1796 prices rose 72%.

By 1811, when the initial 20 year charter expired, the bank had hard money assets of $5.01 million and paper assets of $12.87 million. Congress and Senate narrowly voted not to give it a new charter and the bank met its end.

The Second Bank of the United States

An enormous inflation began in the following year, triggered by the War of 1812. The US government issued a huge amount of Treasury notes as well as letting a large number of new banks, often illegal, to spring up and start issuing their own paper money.

When some banks, who had not been recklessly issuing paper, demanded to redeem the worthless paper for hard money (as was their right), the government permitted the money printing banks to suspend payments in gold and silver.

This suspension was allowed to continue for two and a half years.

As Murray Rothbard puts it:

“More important than this inflation, and at least as important as the wreckage of the monetary system during and after the war, was the precedent that the two-and-a-half-year-long suspension of specie payment set for the banking system for the future. From then on, every time there was a banking crisis brought on by inflationary expansion and demands for redemption in specie, state and federal governments looked the other way and permitted general suspension of specie payments while bank operations continued to flourish. It thus became clear to the banks that in a general crisis they would not be required to meet the ordinary obligations of contract law or of respect for property rights, so their inflationary expansion was permanently encouraged by this massive failure of government to fulfill its obligation to enforce contracts and defend the rights of property.”

With numerous small banks issuing their own paper, it was decided to try the central bank experiment once again and the Second Bank of the United States was formed, opening in 1817.

Yet the Second Bank did nothing to rein in the recklessness of the smaller banks and merely joined in the money printing party.

It is estimated that between 1816 and 1818 the total money supply in the country grew by over 40%. This triggered an inflationary boom, but eventually the Bank realised it was in trouble and began to behave more responsibly. It contracted credit, purchased millions of dollars of gold and silver and made sure its debtors paid in hard money.

The money supply was almost reduced by half.

This tightening then brought about the country’s first widespread depression in 1819. Defaults and bankruptcies occurred and there was a massive drop in real estate values as well as general prices

It was the first “boom-bust” cycle.

Out of the chaos of 1819 came the Jacksonian movement, dedicated to hard money and 100% reserve banking. In 1831 President Jackson vetoed the recharter of the Second Bank of the United States and in 1833 he removed government money from the bank, effectively destroying it as an institution.

Jackson’s successor Martin van Buren established the independent treasury system, where the government kept its funds in hard money in its own Treasury vaults.

This separation of the federal government and banking would last up until the Civil War.

The Emergence of Legal Tender

The 19th century saw legal tender laws emerge in both Britain and the United States.

Legal tender is when a government designates a currency as acceptable for settling debts, transactions and obligations.

In effect this makes the legal tender currency a mean of payment that must be accepted.

Legal Tender In Britain

The Bank of England Act of 1833 established notes issued by the Bank of England as legal tender and gave the bank a monopoly on the issue of bank notes.

This was further reinforced by the Bank Charter Act of 1844.

No new banks were allowed to issue notes, however banks with existing rights to issue notes were allowed to continue with some restrictions.

But by 1921 this ceased and the Bank of England had a complete monopoly.

Legal Tender In The United States

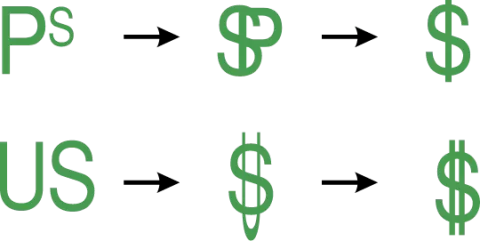

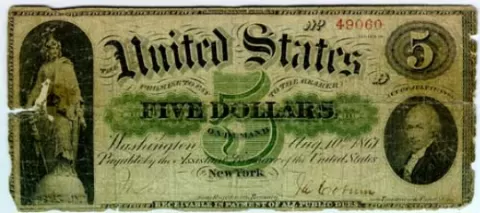

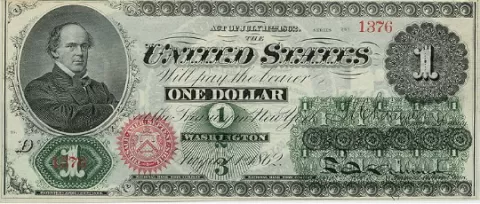

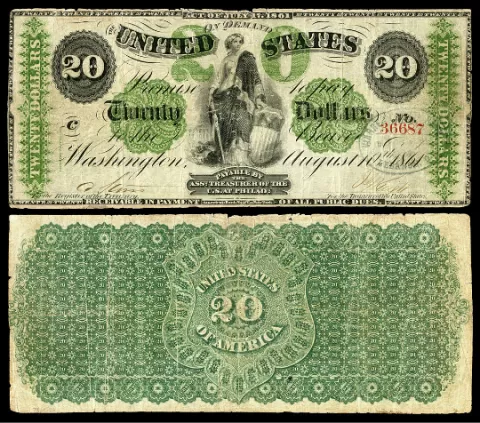

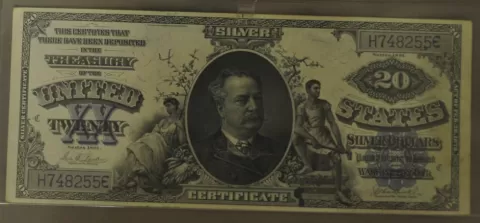

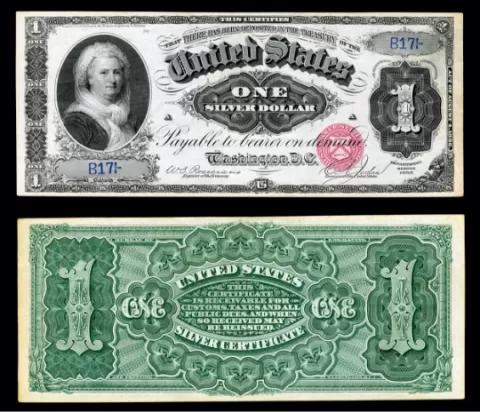

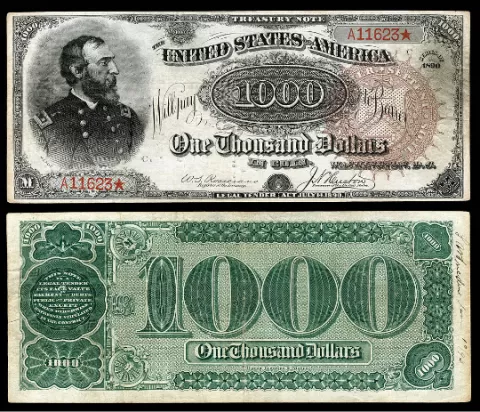

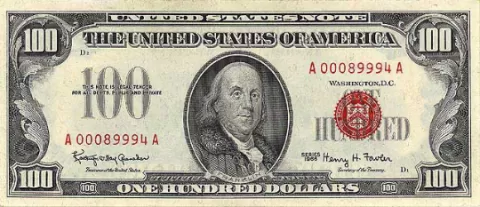

In 1862, during the Civil War, Congress passed the Legal Tender Act, authorising the printing of $150 million of “United States Notes” which would become known as “greenbacks.” This was to fund the ballooning war deficits.

Congress hoped that this would just be one emergency issue. But once the printing starts it is very hard to stop.

A second $150 million was issued later in 1862 with another $150 million to follow in 1863.

Naturally the greenbacks fell in value against gold and silver but, rather than acknowledge that, the government placed the blame on gold speculators. This gave them an excuse to try and regulate the gold market and, when that failed, they tried to destroy the gold market altogether. All this did was destroy confidence in the greenback which depreciated further.

Over the course of the Civil War, the total money supply (including both hard money and paper) expanded 137.9%. Prices rose 110.9%.

The Civil War also spawned another important development – the creation of a national banking system. While this was established under the guise of a war time emergency, it was to have a permanent effect.

The national banking system had three tiers. Central Reserve City was the first tier and that was only for New York. Reserve City was the next tier for any city with 500,000 residents. Country was the final tier for all other national banks.

It swept away the Jacksonian system and replaced it with a centralised system controlled by Washington and Wall Street. Murray Rothbard argues this was the precursor to the Federal Reserve system we have today, which was to be the natural next step from a central banker’s point of view.

The structure of those banks and the reserve requirements meant that the system by its nature was inflationary. Murray Rothbard explains how it worked:

“Before the Civil War, every bank had to keep its own specie reserves, and any pyramiding of notes and deposits on top of that was severely limited by calls for redemption in specie by other, competing banks as well as by the general public. But now, reserve city banks could keep half of their reserves as deposits in New York City banks, and country banks could keep most of theirs in one or the other, so that as a result, all the national banks in the country could pyramid in two layers on top of the relatively small base of reserves in the New York banks. And furthermore, those reserves could consist of inflated greenbacks as well as specie.”

In other words, individual banks used to be limited in issuing paper money by their own gold and silver reserves. Now, as part of a system of banks they could use each others reserves, meaning the reserve requirement was less and they could print more paper money.

After the Civil War the US faced the twin problem of massive debt and a huge circulation of paper. Those who argued for a return to hard money were shouted down and the national banking system was bedded in for good.

Between 1865 and 1873 the total supply of state and national bank notes and deposits grew by 135.2% before leveling off in the panic of 1873.

In 1873 the US went onto the gold standard. This was the era in the industrialised world known as the classical gold standard. All major powers tied their currencies to gold or pegged their currency to a country who had tied theirs to gold.

The gold standard was threatened in the 1890s but survived the decade intact. It would continue this way until 1933 when Roosevelt famously took the US off the gold standard, although the dollar would retain a link to gold until 1971 when Nixon cut the last ties.

Read More: The History of US Currency

The Evolution of Paper Money Into Modern Fiat Currency

The gold standard.

The era of the 1870s to 1914 was known as the classical gold standard . With Britain on a gold standard and the new country of Germany going on a gold standard, other countries followed suit.

This was a system where countries fixed the value of their currencies to gold at a defined weight or fixed their currency to another country that did so.

The role of central banks under this system was to maintain the ability to convert paper money into gold at the fixed price.

This system put a check on the ability of central banks to issue too much currency, which in turn limited the boom and bust nature of inflationary monetary expansion.

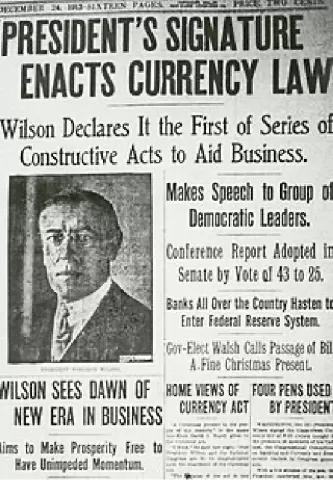

A financial panic in the United States in 1907 increased the clamour for a central bank in the US modelled on the European central banks. After years of planning this culminated in the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 which established the Federal Reserve system in 1914 as we know it today.

Rothbard argues that this was:

“A governmentally created and sanctioned cartel device to enable the nation’s banks to inflate the money supply in a coordinated fashion, without suffering quick retribution from depositors or noteholders demanding cash.”

In the same year as the Fed was established, war destroyed the classical gold standard that had served the world so well for two generations.

The outbreak of World War One in 1914 meant the belligerents abandoned the gold standard. The European powers thought they were engaging in a short war and did not want to fund it with increased taxation.

The solution was to pay for the war through the printing press.

The expected short war lasted for four years, leading to immense hardship and suffering, the downfall of four empires and devastating economic consequences.

Debt exploded, prices rose, shortages occurred and the money printing continued. Russia went into a hyperinflation under the Bolsheviks (and again in 1992 after the collapse of the Soviet Union ), as did Germany under the new Weimar Republic.

With the European powers all off the gold standard, only the USA remained with its pre-war monetary system, although the Fed had doubled the money supply to finance the war when the US entered in 1917.

With this chaotic fiat experience, Europe looked nostalgically at the pre-war classical gold standard.

By 1920 Britain had the least inflated currency with only a 35% depreciation relative to its 1914 value, compared to 64% for the French Franc and 71% for the Italian Lira. The German mark had lost 96% of its value and it was about to get much worse for them.

At the 1922 Genoa conference, the European powers hammered out a new monetary system for the post-war environment, setting in place plans to return to gold and calling for the establishment of central banks in countries where they did not exist.

In 1925 Britain, seeing the fiat system as intolerable, led the way and returned to the gold standard.

But they got the price horribly wrong.

Hoping to return to the pre-war classical gold standard they set the price at the pre-war level £4.86 per ounce. With the wartime money printing double the money supply not accounted for, this resulted in a significantly overvalued British Pound and undervalued gold. This made British exports very expensive.

The only way to make this work would have been to contract the money supply back to the pre-war level. But they did not, continuing with a policy of inflation and cheap money.

Rothbard argues that, aside from the issue of price, this was not a true gold standard anyway. Because of the mechanisms in how it was set up, it did not prevent money printing and inflation.

It is instead known as the gold exchange standard.

Rothbard again:

“In this way, for a few years Britain could have its cake and eat it too. It could enjoy the prestige of going back to gold, going back at a highly overvalued pound, and yet continue to pursue an inflationary, cheap-money policy instead of the opposite. It could inflate pounds and see other countries keep their sterling balances and inflate on top of them; it could induce other countries to go back to gold at overvalued currencies and to inflate their money supplies; and it could also try to prop up its flagging exports by using cheap credit to lend money to European nations so that they could purchase British goods.”

By 1926 39 countries had followed Britain onto the gold exchange standard and by 1928 that number was 43.

The USA had been inflating throughout the 1920s, the theory being that Britain’s new gold standard would be more workable if the USA had higher prices. This accelerated in 1927 and, along with artificially low interest rates, poured fuel on the fire that was the American stock market.

By the late 1920s, England was suffering from the effects of returning to gold at the pre-war price. With an overvalued pound and high wages due to unionism, British exports continued to suffer. With an outflow of gold from London, the British pleaded with the USA to keep inflating and they obliged.

Despite the best effort efforts of central banks to inflate, this undervalued gold exchange standard resulted in deflation and eventually a collapse of money and credit. It was a key cause of the Great Depression.

Jim Rickards argues:

“Gold did not cause the Great Depression; a politically calculated gold price, and incompetent discretionary monetary policy, did. For a functional gold standard, gold cannot be undervalued. When gold is undervalued, central bank money is overvalued, and the result is deflation.”

Or as Rothbard describes it:

“The international monetary framework of the 1920s collapsed in the storm of the Great Depression; or rather, it collapsed of its own inner contradictions in a depression which it had helped to bring about. For one of the most calamitous features of the depression was the international wave of banking failures; and the banks failed from the inflation and overexpansion which were the fruits of the managed international gold-exchange standard. Once the jerry-built pyramiding of bank credit had collapsed, it brought down the banking system of nation after nation; as inflation led to a piling up of currency claims abroad, the cashing in of the claims led to a well-founded suspicion of the solvency of other banks, and so the failures spread and intensified.”

The Fed tried its best to inflate its way out of the Great Depression but despite their best efforts the money supply actually fell. Americans began a run on the banks and foreigners, losing confidence in the dollar, withdrew gold. Fractional reserve banks could not meet the demands of their customers and failed in enormous numbers.

This triggered a death spiral. As Rothbard explains:

“The more that Hoover and the Fed tried to inflate, the more worried the market and the public became about the dollar, the more gold flowed out of the banks, and the more deposits were redeemed for cash.”

After experiencing bank runs, Austria and Germany went off the gold standard in 1931.

Britain too came under pressure in 1931 as those holding pounds demanded redemption in gold. Under the classical gold standard Britain could have tightened her monetary policy to restore confidence but instead after just 6 years Britain abandoned the new gold standard and inflated her currency further.

The pound fell by 30%.

25 countries followed Britain off the gold standard and onto floating exchange rates.

Incoming US President Franklin Roosevelt followed suit in 1933. He ended the official gold standard, confiscated gold from US citizens, put an embargo on the export of gold and devalued the dollar by raising the price of gold from $20.67 to $35 per ounce.

The US Dollar was still linked to gold, but since citizens could not convert their dollars to gold it was not a true gold standard. Instead it has been described by some as a quasi gold standard.

China, which was on a silver standard, had been making preparations for a shift to a gold standard.

However, events in the United States and Europe and the changes to the gold standard meant they decided to skip the yellow metal altogether and go straight from silver to fiat with the introduction of the fabi in 1935.

Read More: A History of the Renminbi

Bretton Woods

A big shift in the global monetary system then occurred during World War Two at the Bretton Woods conference. The 1930s had been a period of monetary nationalism and the USA sought to re-establish an international monetary system.

With Europe devastated by war, the Bretton Woods agreement saw the US Dollar replaced the British Pound as the supreme currency of the world. Foreign currencies were to be set at fixed exchange rates based on the dollar. This system would last until 1971.

The Bretton Woods system initially worked quite well as European currencies were inflated and overvalued. The US Dollar, still linked to gold, was, as Rothbard says, the “hardest currency” and the US had accumulated a vast quantity of gold that had fled Europe during the war.

Yet in the 1950s, as the USA continued her inflationary policies, several European countries became more conservative, in particular West Germany, France, Italy and Switzerland.

With the dollar still fixed to gold at $35 per ounce, the inflationary policy of the USA meant that US dollars were overvalued relative to gold. The Europeans, who held a lot of US Dollars were concerned.

As the dollar became more inflated and more overvalued, it’s role as the global reserve currency came into question as confidence in it collapsed.

Rather than hold dollars, these European countries would rather hold gold. Most notably France, under President Charles de Gaulle, and Switzerland were selling overvalued dollars and buying gold. This led to a worrying outflow of gold from the USA.

In response to this the USA could have raised the price they fixed their currency to gold, in other words devalued their currency. They could have restrained their inflationary policies and increased the soundness of the dollar.

Instead, on a Sunday evening in August 1971, President Richard Nixon famously “closed the gold window.” In practice this meant that foreign central banks were no longer able to convert US dollars into gold at the fixed price of $35 per ounce. This effectively ended the post-war monetary system and by 1973 the Bretton Woods system had completely collapsed.

The Fiat Currency Era

What followed the Bretton Woods system was a global monetary order of floating exchange rates with no link to a hard asset – fiat money.

Since most people were accustomed to using paper money and, since it was still paper money, it seemed the same as it was before.

But it wasn’t.

The US had moved from paper money backed and freely convertible to gold, to paper money backed but not freely convertible to gold, to paper money neither backed nor convertible into gold.

Paper money that is convertible to gold, however tenuous that link, is very different to paper money that exists by fiat or by decree.

This system that emerged in 1971 is still the system we live in today and exists entirely on fiat money and confidence in central banks.

Saifedean Ammous makes the point that the public’s acceptance of this money was only possible because the paper was originally redeemable in gold or silver:

“No fiat money has come into circulation solely through government fiat; they were all originally redeemable in gold or silver, or currencies that were redeemable in gold or silver. Only through redeemability into salable forms of money did government paper money gain its salability. Government may issue decrees mandating people use their paper for payments, but no government has imposed this salability on papers without these papers having first been redeemable in gold and silver.”

Although now the vast majority of money in the system does not exist on physical paper but is digital instead. Nevertheless the issue remains the same. The increase in quantity of fiat money is not restrained by any link to gold. The public accepts this digital fiat money only through its historic link to gold and the confidence that is currently given to central banks.

Since 1971 the US Dollar has continued to be inflated, as have all other fiat currencies, and the market price of gold is well above $35 per ounce. In fact, it is not that gold has risen in value, it is that dollars have fallen in value relative to gold.