'Whack at Your Reader at Once': Eight Great Opening Lines

Examples of How to Begin an Essay

- Writing Essays

- Writing Research Papers

- English Grammar

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In "The Writing of Essays" (1901), H.G. Wells offers some lively advice on how to begin an essay :

So long as you do not begin with a definition you may begin anyhow. An abrupt beginning is much admired, after the fashion of the clown's entry through the chemist's window. Then whack at your reader at once, hit him over the head with the sausages, brisk him up with the poker, bundle him into the wheelbarrow, and so carry him away with you before he knows where you are. You can do what you like with a reader then, if you only keep him nicely on the move. So long as you are happy your reader will be so too.

Good Opening Lines for Essays

In contrast to the leads seen in Hookers vs. Chasers: How Not to Begin an Essay , here are some opening lines that, in various ways, "whack" the reader at once and encourage us to read on.

- I hadn't planned to wash the corpse. But sometimes you just get caught up in the moment. . . . (Reshma Memon Yaqub, "The Washing." The Washington Post Magazine , March 21, 2010)

- The peregrine falcon was brought back from the brink of extinction by a ban on DDT, but also by a peregrine falcon mating hat invented by an ornithologist at Cornell University. . . . (David James Duncan, "Cherish This Ecstasy." The Sun , July 2008)

- Unrequited love, as Lorenz Hart instructed us, is a bore, but then so are a great many other things: old friends gone somewhat dotty from whom it is too late to disengage, the important social-science-based book of the month, 95 percent of the items on the evening news, discussions about the Internet, arguments against the existence of God, people who overestimate their charm, all talk about wine, New York Times editorials, lengthy lists (like this one), and, not least, oneself. . . . (Joseph Epstein, "Duh, Bor-ing." Commentary , June 2011)

- Before the 19th century, when dinosaur bones turned up they were taken as evidence of dragons, ogres, or giant victims of Noah's Flood. After two centuries of paleontological harvest, the evidence seems stranger than any fable, and continues to get stranger. . . . (John Updike, "Extreme Dinosaurs." National Geographic , December 2007)

- During menopause, a woman can feel like the only way she can continue to exist for 10 more seconds inside her crawling, burning skin is to walk screaming into the sea--grandly, epically, and terrifyingly, like a 15-foot-tall Greek tragic figure wearing a giant, pop-eyed wooden mask. Or she may remain in the kitchen and begin hurling objects at her family: telephones, coffee cups, plates. . . . (Sandra Tsing Loh, "The Bitch Is Back." The Atlantic , October 2011)

- There is a new cell-phone ring tone that can't be heard by most people over the age of twenty, according to an NPR report. The tone is derived from something called the Mosquito, a device invented by a Welsh security firm for the noble purpose of driving hooligans, yobs, scamps, ne'er-do-wells, scapegraces, ruffians, tosspots, and bravos away from places where grownups are attempting to ply an honest trade. . . . (Louis Menand, "Name That Tone." The New Yorker , June 26, 2006)

- Only a sentence, casually placed as a footnote in the back of Justin Kaplan's thick 2003 biography of Walt Whitman, but it goes off like a little explosion: "Bram Stoker based the character of Dracula on Walt Whitman." . . . (Mark Doty, "Insatiable." Granta #117, 2011)

- I have wonderful friends. In this last year, one took me to Istanbul. One gave me a box of hand-crafted chocolates. Fifteen of them held two rousing, pre-posthumous wakes for me. . . . (Dudley Clendinen, "The Good Short Life." The New York Times Sunday Review , July 9, 2011)

What Makes an Opening Line Effective

What these opening lines have in common is that all have been reprinted (with complete essays attached) in recent editions of The Best American Essays , an annual collection of crackling good reads culled from magazines, journals, and websites.

Unfortunately, not all the essays quite live up to the promise of their openings. And a few superb essays have rather pedestrian introductions . (One resorts to the formula, "In this essay, I want to explore . . ..") But all in all, if you're looking for some artful, thought-provoking, and occasionally humorous lessons in essay writing, open any volume of The Best American Essays .

- Hookers vs. Chasers: How Not to Begin an Essay

- How to Begin an Essay: 13 Engaging Strategies

- Write an Attention-Grabbing Opening Sentence for an Essay

- What Are the Different Types and Characteristics of Essays?

- Examples of Great Introductory Paragraphs

- A Guide to Using Quotations in Essays

- The Difference Between an Article and an Essay

- 50 Great Topics for a Process Analysis Essay

- What Is a Compelling Introduction?

- Writers on Writing: The Art of Paragraphing

- The Title in Composition

- Development in Composition: Building an Essay

- Bad Essay Topics for College Admissions

- How to Write a Great College Application Essay Title

- How to Structure an Essay

- List of Topics for How-to Essays

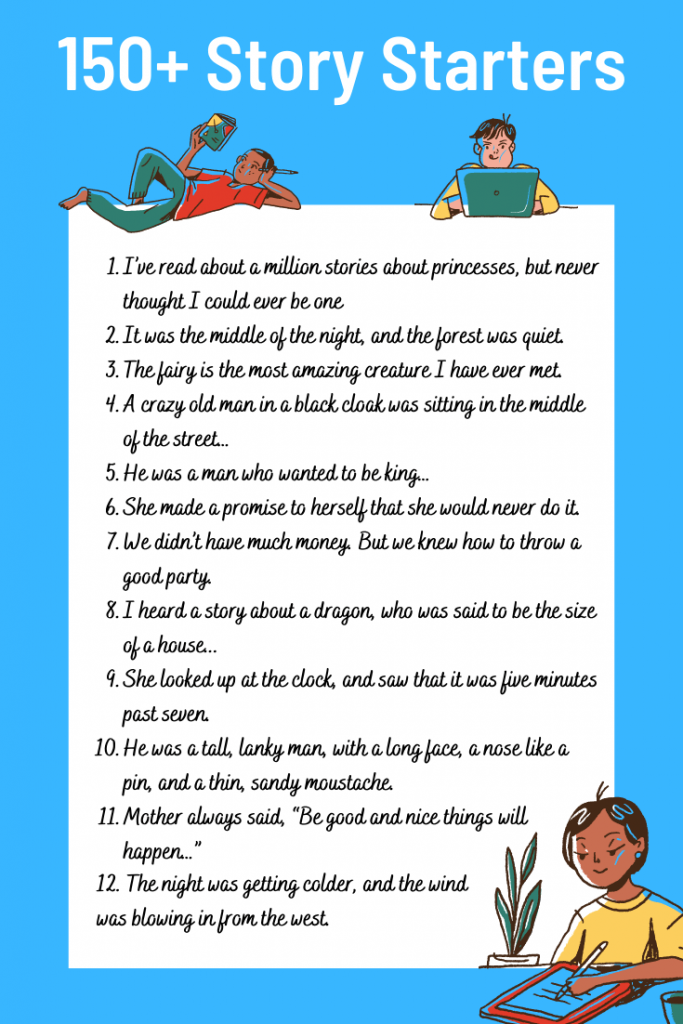

36 Engaging opening sentences for an essay

Last Updated on July 20, 2022 by Dr Sharon Baisil MD

An essay’s opening sentence has a tremendous impact on the reader. It doesn’t matter if you’re writing an argumentative essay, a personal narrative, or a research paper; how your text begins will affect its tone and topic. You can write about anything as long as it is relevant to your thesis—starting with an engaging opening sentence may be the difference between a successful and unsuccessful essay.

An introduction is the first section of any paper that allows you to introduce your thesis and provide an overview of your argument or discussion. A good introduction should grab your audience’s attention and entice them to read on, summarising what you’re trying to say concisely. It’s a good idea to think of your introduction as a hook, writing an opening sentence that will leave your reader wanting more.

Writing a thesis statement is the first thing you need to do when planning your paper. Although there are multiple strategies for creating a thesis statement, you must express yourself clearly and answer three simple questions: What is the main idea of my essay? Why is it important? How do I plan to prove it in a paper?

There are countless ways to begin an essay or a thesis effectively. As a start, here are 36 introductory strategies accompanied by examples from a wide range of professional writers.

1. “Is it possible to be truly anonymous online?”

This is an engaging opening sentence because it immediately poses a problem that the reader will likely want answered. It’s also interesting that this question applies directly to internet usage, something everybody has experience with. The subject of the opening sentence is “online anonymity,” which allows the writer to discuss two related concepts.

2. “I was shocked to awake one morning to find I had turned into a snail.”

The opening sentence immediately grabs the reader’s attention with its play on words, leaving them unsure if it’s meant as a joke. It continues to entertain by combining an unlikely image (a person turning into a snail) with waking up more common. The sentence also establishes the essay’s tone, which is humorous and personal.

3. “I didn’t want to study abroad.”

This opening sentence immediately intrigues the reader because it presents an opinion that contradicts what would be expected in this type of assignment. The writer then follows with a statement about their decision to study abroad, discussing the reasons for this choice and explaining their position on the matter.

4. “The three dogs had been barking for over an hour before my neighbor finally came out to investigate.”

This opening sentence introduces a narrative about something that happened in the past, starting with dogs barking at night. The next sentence provides background information by revealing that the neighbor came out after an hour and then reasons for this delay. The fact that the writer does not reveal why this is significant until later on makes the opening sentence even more effective because it keeps the reader engaged with what will happen next.

5. “I have always been interested in fashion.”

This opening sentence immediately sets the topic for the entire paper by discussing interest in fashion. It also establishes the tone, clearly portraying the writer’s voice while informing the audience about their personal experience with the subject matter.

6. “I remember when I first realized I didn’t have a home.”

This opening sentence begins a personal narrative about a time before moving out of their family home when the writer realized they didn’t live there anymore. It uses flashbacks to set up the rest of the essay by showing what happened before they moved out and how this made them feel.

7. “When I was in middle school, my dad told me not to get into fights.”

This opening sentence establishes a relationship between the writer and the subject of their essay, creating a more personal tone. It also establishes an expectation for what will be discussed by telling something that happened in the past. The sentence ends with a twist, so it’s more interesting than just stating something that was told to them, making this opening sentence effective.

8. “When I first sat down to write this essay, I was absolutely certain of the thesis.”

This opening sentence immediately introduces conflict because it tells about something that didn’t occur as expected. It also implies that there will be an alternate solution or angle for this paper that will be explored in the following paragraphs. The vocabulary (like “absolutely”) suggests more certainty in this opening paragraph than presented, making it interesting to read.

9. “I remember the first time I killed a man.”

This opening sentence offers an unexpected statement that intrigues the reader and immediately draws them into the essay, wanting to know more about what happened. This type of sentence is called a gripping opener because it does just that. The sentence is also effective because it creates suspense and anticipation in the reader’s mind about what will happen next in this story .

10. “There are two sides to every story: my side and your side.”

This opening sentence introduces a topic that will be revisited multiple times throughout the essay, making it effective for an introduction. It also creates a sense of mystery about the two sides and how they relate to each other, which will be resolved later on once it becomes clear that there are three sides.

11. “I should start this essay by introducing myself.”

This opening sentence includes an explanation for why this paragraph is being written (to introduce oneself) before it ends with a question (“who am I?”). This is effective because it gets the reader to think critically about who the writer is and what they want to say. It also permits them to stop reading after this sentence if they don’t feel like it, making it one of the less intimidating opening sentences.

12. “At the age of seven, I knew my life was going to be amazing.”

This opening sentence establishes a confident, optimistic tone by mentioning something that happened in the past. It also implies that the writer had this positive outlook before anything particularly special happened to them yet, which will likely be mentioned later on, making it more interesting to read.

13. “I don’t know when I lost my sense of excitement for learning.”

This opening sentence presents a conflict that the writer will likely try to resolve in this essay, which gives the reader something to look forward to. It also establishes voice by expressing how they feel about their education so far and suggesting what could be done about it.

14. “Coming home after a long day of school and work is like walking into a warzone.”

This opening sentence creates a sense of conflict that will likely be discussed later on and establishes voice because it shows the writer’s attitude towards their environment. It provides an example of why this subject has been brought up by describing what happens during this “warzone” of a day.

15. “I’ve always loved school.”

This opening sentence is effective because it provides an example of how their life used to be before the issue was introduced (in the next few sentences), making it more interesting to read. It also creates a sense of nostalgia about how good things used to be, making it more engaging.

16. “I feel like I’m losing my mind.”

This opening sentence is effective because it creates a voice by describing the writer’s experience and establishes conflict, so the reader knows what to expect in this essay. It provokes an emotional response in the reader, making them more interested.

17. “On day two of our honeymoon, my wife passed out.”

This opening sentence creates suspense by mentioning what happens before revealing why this is significant. It also establishes conflict because it implies that the writer’s wife’s health will be an issue throughout the essay. This leads to a likely discussion about whether or not they should continue their honeymoon, making it engaging for the reader.

18. “I’m a college student, and I hate it.”

This opening sentence establishes conflict for the rest of the essay because it implies that something negatively affects their education. It also establishes voice by showing what they think about being a student and how they feel about college so far, which makes it more interesting to read.

19. “The first time I heard the word ‘stan’ was when Eminem released his song in 2000 by the same name.”

This opening sentence establishes conflict for what will likely be discussed later on and also creates a sense of nostalgia because it takes the reader back to a significant point in recent history that they might remember (rare for essays). It also establishes voice because it shows the writer’s knowledge about rap music.

20. “I used to hate when people asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up because I never knew how to answer them.”

This opening sentence helps the reader understand why this essay was written to tie into their own experiences. It also establishes conflict by revealing something that the writer used to be troubled by. It also makes them seem relatable because everyone has problems with their future at one point or another.

21. “All my life, I’ve been told I was destined for greatness.”

This opening sentence establishes that the writer had difficulties in their life despite being seen as destined for greatness so far. It also creates a sense of conflict because it implies that they will have to convince the reader otherwise, making it more interesting to read.

22. “My friend once told me that I should never say ‘I’m just being honest when discussing our differences, but I always do.”

This opening sentence creates conflict by showing the reader that there is always tension between the writer and their friend because of this issue. It also establishes voice because it shows how honest they are about their differences, which makes them more relatable. This makes it engaging for the reader to read on.

23. “I’ve never been one to keep my emotions bottled up, and now that I’m pregnant, that’s been amplified.”

This opening sentence establishes emotion from the writer because it shows that they are uncomfortable keeping their emotions to themselves and continue to do so even when they become pregnant. It also creates a sense of conflict because the reader will probably wonder how this lack of emotional inhibition might affect them later on.

24. “The first time I read ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ it changed my life.”

This opening sentence grabs the reader’s attention and shows what impact this book has had on the writer so far. It also establishes how passionate the writer is towards literature and makes them more relatable because many people have been affected by great works of literature in some way. This is engaging for the reader to read on.

25. “As I walked out of class one day, my professor asked me what I wanted to do with my future.”

This opening sentence establishes conflict by showing that there was a time when the writer did not have an answer to this question despite being capable of doing anything in their mind. It also establishes voice by showing that the writer can stand up for themselves when pushed and makes them seem more relatable because everyone struggles with thinking about their future at some point or another. This is engaging for the reader to continue reading.

26. “I’ve always been taught that it’s impolite to talk about money, but I want to share my experience with you.”

This opening sentence establishes voice by showing that the writer does not abide by this code of conduct because they believe it’s more important to be open and honest. It also creates a sense of conflict so that the reader might have their own contrasting opinions, which will create tension while reading. This is engaging for the reader to continue reading.

27. “Growing up, I never liked math, and it wasn’t until college that I realized why.”

This opening sentence establishes voice because it shows how passionate the writer was about their dislike of math despite not knowing why. It also creates conflict because they will have to explain their reasoning to the reader, which makes it more interesting to read, and it is engaging for the reader to read on.

28. “There are so many factors that go into determining how much someone should be paid, but I believe that everyone deserves equal pay.”

This opening sentence establishes conflict because the writer believes in something that not many people support, and they will have to explain their reasoning. It also establishes voice because it shows that the writer is passionate about this belief and makes them more relatable for other people who share the same opinion. This is engaging for the reader to read on.

29. “Many things have been said about Millennials, but no one has asked us what we think.”

This opening sentence creates a sense of conflict because the reader might be wondering what this person thinks as a Millennial. It also establishes voice by using “us” to show that they are not alone in their beliefs and makes them seem more relatable. This is engaging for the reader to read on.

30. “I finally found a job that I love, and as it turns out, it’s located in a city that has been my dream destination since I was little.”

This opening sentence establishes voice because it shows how the writer feels about their new job and makes them sound passionate about their work which makes the reader want to read on. This is engaging for the reader to continue.

31. “It was the summer of 2001 when I first came across an anime dubbed in French.”

This opening sentence establishes voice through personal experience and makes it relatable because many people have watched their favorite movies or shows in another language. It also creates a sense of conflict by making the reader wonder why they continued watching even though they didn’t understand much of what was being said. This is engaging for the reader to read on.

32. “For years, I thought my life was perfect, until one day when I realized that there’s nothing more important than your mental health.”

This opening sentence establishes voice by showing that the writer used to have this belief but then had a heart change, making them more relatable because everyone’s beliefs change over time. It also creates a sense of conflict by questioning what the reader believes about their mental health, which will make them want to continue reading. This is engaging for the reader to read on.

33. “As children, it’s easy to dream about becoming an astronaut or a firefighter, but I never imagined that my greatest passion would be writing.”

This opening sentence establishes voice by showing how the writer is passionate about what they are currently doing. It also creates a sense of conflict because the reader may have different interests, making it more interesting to read. This is engaging for the reader to continue reading on.

34. “If you would’ve asked me a few months ago, I wouldn’t have said that my life was perfect. However, after some time and perspective, I’m grateful for the twists and turns.”

This opening sentence establishes voice by showing how this person’s perspective has changed over time. It also creates a sense of conflict because it questions what the reader thinks and makes them want to read on. This is engaging for the reader to read on.

35. “Everyone has goals in life, whether it’s saving up enough money to buy a house or finally writing that book.”

This opening sentence establishes conflict because it questions the reader’s goals and shows how they may be different from the writer’s. It also creates a sense of connection because many people share the same goals and make them want to keep reading. This is engaging for the reader to read on.

36. “I’m not sure if I’ve ever told you this, but my favorite show as a child was A Little Princess.”

This opening sentence establishes voice by showing that the writer shares a secret and makes them sound like they’re talking directly to someone. It also creates a sense of conflict because it’s difficult to imagine that the reader doesn’t know this information and makes them want to read on. This is engaging for the reader to read on.

Final Words

To conclude, there are countless ways to begin an essay or a thesis effectively. These 36 opening sentences for an essay are just a few examples of how to do so. There is no “right way” to start, but it will become easier to find your voice and style as you continue writing and practicing. Good luck!

Harvard University

Purdue University

Royal Literary Fund- Essay Writing Guide

University of Melbourne

Amherst College

Most Read Articles in 2023:

Hi, I am a doctor by profession, but I love writing and publishing ebooks. I have self-published 3 ebooks which have sold over 100,000 copies. I am featured in Healthline, Entrepreneur, and in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology blog.

Whether you’re a busy professional or an aspiring author with a day job, there’s no time like now to start publishing your ebook! If you are new to this world or if you are seeking help because your book isn’t selling as well as it should be – don’t worry! You can find here resources, tips, and tricks on what works best and what doesn’t work at all.

In this blog, I will help you to pick up the right tools and resources to make your ebook a best seller.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Benjamin McEvoy

Essays on writing, reading, and life

How To Write A Great Opening Line (10 Techniques From Famous Writers)

September 15, 2016 By Ben McEvoy

First lines are like foreplay.

You’ve already hooked your reader with the cover, title, and blurb. You’ve picked them up. Now they’re back at your place.

Seduction time.

What’s your opening move?

How do you set the stage for what’s about to happen? Is it going to be tantric, rough, tender, completely lacklustre, or completely mind-blowing?

Will they even want to go through with it? Will they change their mind, cite a headache or an early meeting as an excuse, and make their hasty exit, putting you back on the shelf and choosing another? Or will they fork over ten bucks and lay prostrate on the bed as the experience unfolds?

Okay… enough with this weird metaphor. Let’s get to the techniques. Whether you want to be a Pulitzer Prize winner or pen fast-paced pulp, a great opening line is key. Here are 10 techniques to nail it.

1. Make the first line mirror the last – American Psycho (Bret Easton Ellis)

Study the first line in Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho :

ABANDON ALL HOPE YE WHO ENTER here is scrawled in blood red lettering on the side of the Chemical Bank near the corner of Eleventh and First and is in print large enough to be seen from the backseat of the cab as it lurches forward in the traffic leaving Wall Street and just as Timothy Price notices the words a bus pulls up, the advertisement for Les Miserables on its side blocking his view, but Price who is with Pierce & Pierce and twenty-six doesn’t seem to care because he tells the driver he will give him five dollars to turn up the radio, “Be My Baby” on WYNN, and the driver, black, not American, does so.

Now study the last line:

Someone has already taken out a Minolta cellular phone and called for a car, and then, when I’m not really listening, watching instead someone who looks remarkably like Marcus Halberstam paying a check, someone asks, simply, not in relation to anything, “ Why? ” and though I’m very proud that I have cold blood and that I can keep my nerve and do what I’m supposed to do, I catch something, then realize it: Why? and automatically answering, out of the blue, for no reason, just opening my mouth, words coming out, summarizing for the idiots: “Welll, though I know I should have done that instead of not doing it, I’m twenty-seven for Christ sakes and this is, uh, how life presents itself in a bar or in a club in New York, maybe anywhere , at the end of the century and how people, you know, me, behave, and this is what being Pat rick means to me, I guess, so well, yup, uh…” and this is followed by a sigh, then a slight shrug and another sigh, and above one of the doors covered by red velvet drapes in Harry’s is a sign and on the sign in letters that match the drapes’ color are the words THIS IS NOT AN EXIT.

The first and last lines mirror each other in pace and structure and the inane interior monologue of the central protagonist, Patrick Bateman.

But they do more than that. Look at the first capitalised words. Then look at the last capitalised words.

This is a self-conscious nod to the act of reading itself. Those words (“ABANDON ALL HOPE YE WHO ENTER HERE”) are not just scrawled on the wall. They are a direct instruction to the reader. You are entering a novel but you are also entering Bateman’s mind. To do that, you need to abandon all hope because there is no hope.

The ending mirrors this self-conscious nod again. “THIS IS NOT AN EXIT” says that, although you are putting the book down, it is not over. It will stay with you. Bateman also has no redemption.

American Psycho as a whole is a masterful lesson in writing. The beginning here does a lot of things – things you will need to read the book to understand – but the key lesson here is this:

Consider your work as a whole when writing your first line. Anticipate the themes and foreshadow the ending.

2. Start “in medias res” – ‘Floating Bridge’ (Alice Munro)

Alice Munro, one of the best short story writers of all time, knows a thing or two about opening lines. Study the opening line to her short story ‘Floating Bridge’ from Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage :

One time she had left him.

That’s it. What does that mean? Who is ‘she’? Who is ‘him’? Why did she leave him? Why did she return? We assume she returned because Munro writes “one time”.

So many questions. Just six simple words and yet we find ourselves with almost six different questions that all require complex answers.

This is classic Munro. She dumps us in the middle of a story, almost like we’re in the middle of a conversation, and then she lets us flounder to find out what’s going on. Yet, despite the confusion in piecing things together, we feel a familiarity. We know this person. We know the narrator. We know “she” and “him”.

It’s subtle, it’s understated, it’s genius.

3. Estrange the reader – The Book Thief (Markus Zusak)

The Russian formalists believed that the key to great writing is to make the everyday strange. Make the familiar foreign.

And how better to do that than make the narrator of your book Death himself?

Study how Zusak begins his #1 New York Times bestseller, The Book Thief :

First the colors.

This is even more disorientating and strange than Munro’s beginning. At least with Munro’s opening we have some semblance of reality. We know what’s going on. But Zusak’s opening line is a real blow to the old noggin.

It’s short, it’s simple, it’s weird, and it begs for you to read on. It also – just like Easton Ellis’ opening – foreshadows a major theme/stylistic convention of the novel: kinaesthesia.

I can’t resist. I have to go on and quote the next few lines because they are genius:

Then the humans. That’s usually how I see things. Or at least, how I try. *** HERE IS A SMALL FACT *** You are going to die.

Do you want to read on?

I certainly did. I whizzed through the book in a few evenings.

Reading this opening, we still don’t know who’s talking. But we know he’s not human. Maybe we can figure out that it’s Death.

Then we get that delightful notice in bold, capitalised with asterisks either side. The narrator talks to us directly and tells us a fact that pierces each one of us to our core. He’s direct. No bullshit. And it feels like we are stepping outside of the conventional structure of storytelling. Almost like we’re looking at an artefact in a museum, a photograph in an album, or a piece of evidence in a courtroom.

We’re hooked. Zusak has used structure, tone, and estrangement to hook us.

4. Make non-fiction read like fiction – ‘A Mob Killing and Flawed Justice’ (Alissa J. Rubin)

Pulitzer Prize winning journalism reads like a thriller novel.

Study this opening from Alissa J. Rubin’s extraordinary work examining the trial surrounding an Afghan woman’s public death:

KABUL, Afghanistan — Farkhunda had one chance to escape the mob that wanted to kill her.

We are immediately pulled in to the fray that Rubin is about to detail. We know the victim, Farkhunda, and we know her situation. It’s life or death. Time is running out. This first line is as taut as a hooked fishing line.

Almost every single word does something to increase the drama and suspense: “one chance”, “escape the mob”, “wanted to kill her”.

If we didn’t know any better, we would think we were reading a high-octane thriller. The writing pulls us in and then we realise: this isn’t fiction.

What happens next – the details of Farkhunda’s tragic demise and the unfair lack of due process that follows – is all the more hard-hitting because we have been dragged into the narrative and forced to invest with the victim.

5. Make fiction read like non-fiction – The Day of the Jackal (Frederick Forsyth)

As can be expected from a novel that won the Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America, Forsyth’s The Day of the Jackal grabs the reader in the very first line:

It is cold at six-forty in the morning of a March day in Paris, and seems even colder when a man is about to be executed by firing squad.

We’ve seen a journalist using the techniques of thriller writers and now we can see a thriller writer using the techniques of journalism.

We are immediately confronted with the facts: the when, the where, the what.

Forsyth also gives his text a pounding immediacy in the first three words: ‘It is cold’. The narrative is not written in the present tense but beginning in this way drags you full force into the narrative. We’re right there, aren’t we? We can see the frost spirals of air as we breathe out. Maybe we can see the sun rising over a gray paris landscape. And we can see many men with guns and one unfortunate man without any.

Forsyth also places the most important and striking image at the end of the sentence so it is strong in our minds.

We can’t help but read on.

6. Make intention and obstacle clear – Dark Tower I: The Gunslinger (Stephen King)

One of the many things I learned from the Aaron Sorkin Screenwriting Masterclass is that good writing is made up of intention and obstacle. What does the character want? And what’s stopping them from getting it?

We can see this powerful lesson in the opening to King’s fantastic fantasy series, Dark Tower :

The man in black fled across the desert, and the gunslinger followed.

So simple. Yet so brilliant.

The intention and obstacle are clear. The man in black wants to get away. The gunslinger wants to get the man in black. Classic chase scenes have intention and obstacle built right in.

The first line is also beautiful in its dreamlike quality. ‘Man in black’ sounds mythical. ‘Gunslinger’ sounds like some archetype etched in by so many childhood memories of spaghetti westerns. And the desert. A barren, brutal environment. What are they doing there?

I also geeked out about the grammar. Notice how King puts a comma after the first clause. He didn’t have to. But he chose to. He wanted to. He wanted us to pause as if summoning the distance between the two figures as they traverse the land.

7. Tease the reader by holding back – Twilight (Stephenie Meyer)

Want to learn how to write a killer opening line? Take a lesson from world class copywriters. It certainly seems like Meyer has picked up a thing or two from the language of advertisements.

Study this opening line from Twilight :

I’d never given much thought to how I would die – though I’d had reason enough in the last few months – but even if I had, I would not have imagined it like this.

Like this? Like what?! Tell us! Tell us!

Meyer’s opening line is a massive tease. It’s a matter of life and death and we’re left with so many questions. Questions that will only be answered if we read on.

Notice how she ends on the word “this”.

That’s a powerful technique that advertisers have used over and over again. And it never gets old because it always works. Next time you’re scrolling through clickbait, take note of how many headlines (particularly ones that make you click) use the word “this”.

“This” refers to something you cannot see. You don’t have the information yet. But if you read on, you will. And why wouldn’t we want to read on? We want to know what’s happened in the last few months to give the narrator reason to think of death. And where is she now? What’s happening? Is she dying? If so, how? And by whom?

Tease your reader. Make them ask questions. And promise to answer them… If they read on.

8. Be raw – Code Name Verity (Elizabeth Wein)

Study the first line in Elizabeth Wein’s Code Name Verity :

I AM A COWARD.

Boom. How great is that?

So simple. So direct. So raw.

There is so much baggage in those four words. What has the narrator gone through to reach this conclusion? We get hints of a great story to come. Of opportunities missed or lost or abandoned. What happened?

Even though we don’t know the narrator yet, we can relate to her. We can all relate to feelings of cowardice. We can all relate to failure. We can all relate to feeling like we’re not good enough, like we’ve been a traitor. It hurts. We all know the sting of defeat well. And Wein manages to conjure that up in the first line.

Now that we already feel akin to the narrator, we have something in common, and we trust her (after all, being raw fosters trust), we can’t help but keep reading. We want to get to know this person. We want to learn her story.

9. Begin with a name – Munro, King, Mitchell, Nabokov, Melville, Dickens

You won’t realise how common this technique is until you’re conscious of it. Take note of the next 20 or so stories you read. You’ll be surprised how many of them start with a name.

They might start with just a name, a one-word sentence, calling out from the ether, like in Alice Munro’s ‘Family Furnishings’:

Or in Stephen King’s The Stand :

‘Sally.’

Or in David Mitchell’s The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet :

‘Miss Kawasemi?’

Some stories introduce the main character by way of the narrator talking to you, the reader, in a way that is amiable and polite. This is the case in the iconic opening of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick :

Call me Ishmael.

Some stories will introduce the main character by way of dissecting his or her name and how they came to it. This is the case in Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations :

My father’s family name being Pirrip, and my Christian name Philip, my infant tongue could make of both names nothing longer or more explicit than Pip.

Some stories will begin with a name and then play with it, as though it were music, as though the name contained the essence of the entire story to come. This is the case in Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita :

Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins.

If in doubt, begin your story with the name of the hero, villain, location, whatever. Make it vibrant. Give it meaning. Play with it. Or simply have someone call it out.

10. Make it more than a reading experience – ‘Guts’ (Chuck Palahniuk)

One of the most striking short stories I have ever read is ‘Guts’ by Chuck Palahniuk . It begins like this:

One word. A direct instruction to the reader.

Just like the story itself, this opening is out of the ordinary. Readers aren’t used to be spoken to directly unless it’s in a ‘call-me-Ishmael’ fashion.

So the writer wants us to take a breath? Why? Is he serious? We’ve got to read on, right?

This is what you encounter when you read on:

Take in as much air as you can. This story should last about as long as you can hold your breath, and then just a little bit longer. So listen as fast as you can.

Then the narrator dives into his story.

We’re not just reading a story now. We’re actively invested in the experience. We are conscious of our breath. And we’re wondering how it relates to the story.

Palahniuk also ends this story tremendously and makes you see why you had to take a breath in the first place. I won’t spoil it for you. Go read it .

Keep a log of first lines

Every writer should have a journal of first and last lines. Something you can refer to whenever you need inspiration.

Collect first lines the way some people collect stamps. Examine them often and analyse exactly what makes them so great, why they grabbed you the way they did.

Someone has even put their favourite first and last lines up on a website dedicated to this sole purpose . It makes for great browsing and might even help you find your next read.

Practice writing first lines

As well as a folder of first and last lines, I also have notebooks and journals bursting with first lines to short stories, articles, and novels that don’t and probably never will exist.

Honing first lines is one of the most important skills a writer can have. If you can write a killer first line, you’re well on your way to sucking in readers like a giant vacuum cleaner.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Check your paper for plagiarism in 10 minutes, generate your apa citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- College essay

How to Write a Great College Essay Introduction | Examples

Published on October 4, 2021 by Meredith Testa . Revised on August 14, 2023 by Kirsten Courault.

Admissions officers read thousands of essays each application season, and they may devote as little as five minutes to reviewing a student’s entire application. That means it’s critical to have a well-structured essay with a compelling introduction. As you write and revise your essay , look for opportunities to make your introduction more engaging.

There’s one golden rule for a great introduction: don’t give too much away . Your reader shouldn’t be able to guess the entire trajectory of the essay after reading the first sentence. A striking or unexpected opening captures the reader’s attention, raises questions, and makes them want to keep reading to the end .

Table of contents

Start with a surprise, start with a vivid, specific image, avoid clichés, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about college application essays.

A great introduction often has an element of mystery. Consider the following opening statement.

This opener is unexpected, even bizarre—what could this student be getting at? How can you be bad at breathing?

The student goes on to describe her experience with asthma and how it has affected her life. It’s not a strange topic, but the introduction is certainly intriguing. This sentence keeps the admissions officer reading, giving the student more of an opportunity to keep their attention and make her point.

In a sea of essays with standard openings such as “One life-changing experience for me was …” or “I overcame an obstacle when …,” this introduction stands out. The student could have used either of those more generic introductions, but neither would have been as successful.

This type of introduction is a true “hook”—it’s highly attention-grabbing, and the reader has to keep reading to understand.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

If your topic doesn’t lend itself to such a surprising opener, you can also start with a vivid, specific description.

Many essays focus on a particular experience, and describing one moment from that experience can draw the reader in. You could focus on small details of what you could see and feel, or drop the reader right into the middle of the story with dialogue or action.

Some students choose to write more broadly about themselves and use some sort of object or metaphor as the focus. If that’s the type of essay you’d like to write, you can describe that object in vivid detail, encouraging the reader to imagine it.

Cliché essay introductions express ideas that are stereotypical or generally thought of as conventional wisdom. Ideas like “My family made me who I am today” or “I accomplished my goals through hard work and determination” may genuinely reflect your life experience, but they aren’t unique or particularly insightful.

Unoriginal essay introductions are easily forgotten and don’t demonstrate a high level of creative thinking. A college essay is intended to give insight into the personality and background of an applicant, so a standard, one-size-fits-all introduction may lead admissions officers to think they are dealing with a standard, unremarkable applicant.

Quotes can often fall into the category of cliché essay openers. There are some circumstances in which using a quote might make sense—for example, you could quote an important piece of advice or insight from someone important in your life. But for most essays, quotes aren’t necessary, and they may make your essay seem uninspired.

If you want to know more about academic writing , effective communication , or parts of speech , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Academic writing

- Writing process

- Transition words

- Passive voice

- Paraphrasing

Communication

- How to end an email

- Ms, mrs, miss

- How to start an email

- I hope this email finds you well

- Hope you are doing well

Parts of speech

- Personal pronouns

- Conjunctions

The introduction of your college essay is the first thing admissions officers will read and therefore your most important opportunity to stand out. An excellent introduction will keep admissions officers reading, allowing you to tell them what you want them to know.

The key to a strong college essay introduction is not to give too much away. Try to start with a surprising statement or image that raises questions and compels the reader to find out more.

Cliché openers in a college essay introduction are usually general and applicable to many students and situations. Most successful introductions are specific: they only work for the unique essay that follows.

In most cases, quoting other people isn’t a good way to start your college essay . Admissions officers want to hear your thoughts about yourself, and quotes often don’t achieve that. Unless a quote truly adds something important to your essay that it otherwise wouldn’t have, you probably shouldn’t include it.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Testa, M. (2023, August 14). How to Write a Great College Essay Introduction | Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 28, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/college-essay/introduction-college-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Meredith Testa

Other students also liked, college essay format & structure | example outlines, how to end a college admissions essay | 4 winning strategies, what do colleges look for in an essay | examples & tips, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

A Celebration of Great Opening Lines in World Literature

Launched: January 1, 2022

This website is dedicated to the memory of John O. Huston (1945-2022)

An opening line should invite the reader to begin the story. It should say: Listen. Come in here. You want to know more about this.

Welcome to GreatOpeningLines.com , history’s first website devoted exclusively to the celebration of great opening lines in world literature. Even though the site is still in its infancy (it was officially “launched” on Jan. 1, 2022), it is already the world's largest online database of literary history’s greatest opening words, with 1976 current entries.

If you’re a writer or aspiring writer, an avid reader, an English teacher or creative writing instructor, a reference librarian, an editor, or simply a First Words junkie, think of this as your "Go-To" site on the subject. In addition to learning more than you now know about your current personal favorites, this site will introduce you to thousands of future favorites you might never have known about in any other way.

Be careful, though, as you begin to peruse the twenty-five “genres” below. Robert McCrum, the legendary British editor of four separate Nobel Prize laureates has warned that this "brilliant and fascinating literary site...will soon become every freelance writer's guilty pleasure."

"It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife." Jane Austen

Short Stories

"Early one June morning in 1872 I murdered my father—an act which made a deep impression on me at the time." Ambrose Bierce

Non-Fiction

"The problem lay buried, unspoken, for many years in the minds of American women." Betty Friedan

Memoirs & Autobiographies

"I didn’t realize I was black until third grade." Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

Biographies

"The black eyepatch dominated Moshe Dayan’s appearance, like some dark, spidery animal wrapped around his face." Robert Slater

Essays, Articles, & Columns

"These are the times that try men's souls." Thomas Paine

Children's Literature

"All children, except one, grow up." J. M. Barrie

Young Adult (YA) Fiction

"I'd never given much thought to how I would die — though I'd had reason enough in the last few months — but even if I had, I would not have imagined it like this." Stephenie Meyer

Science-Fiction

"It was a dazzling four-sun afternoon." Isaac Asimov

Speculative Fiction

"As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect." Franz Kafka

Wit, Humor, Parody, & Satire

"Work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion." C. Northcote Parkinson

War/Combat & Espionage/Spies

"A story has no beginning or end: arbitrarily one chooses that moment of experience from which to look back or from which, to look ahead." Graham Greene

Cowboy/Western Tales

"There will come a time when you believe everything is finished. That will be the beginning." Louis L'Amour

Crime/Detective & Suspense/Thrillers

"When the guy with asthma finally came in from the fire escape, Parker rabbit-punched him and took his gun away." Richard Stark

History & Historical Fiction

"Jazz came to America three hundred years ago in chains." Paul Whiteman

Politics & Government

"A phenomenon noticeable throughout history regardless of place or period is the pursuit by governments of policies contrary to their own interests." Barbara Tuchman

Philosophy & Religion

"Man was born free, and everywhere he is in chains." Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Words/Language & Writers/Books

"Writers will happen in the best of families. No one is quite sure why." Rita Mae Brown

Medicine & Health

"You know more than you think you do." Dr. Benjamin Spock

Sports, Fitness, & Recreation

"I was born to be a point guard, but not a very good one." Pat Conroy

Psychology & Self-Help

"How do you make contact with the mind of another person?" Mortimer J. Adler

Sex, Love, Marriage, & Family

"Children are the living messages we send to a time we will not see." Neil Postman

Travel, Food & Drink

"An oyster leads a dreadful but exciting life." M.K.F. Fisher

Science & Technology

"It is not easy to cut through a human head with a hacksaw." Michael Crichton

Race, Gender, & Ethnicity

"I have rape-colored skin." Caroline Randall Williams

Accolades & Acknowledgments

About this site.

Welcome to history’s first website devoted exclusively to the celebration of great opening lines in world literature. My goal is to make this the world's largest online database of Great Opening Lines in both Fiction and Non-Fiction. If you’re a writer or aspiring writer, an avid reader, an English teacher or creative writing instructor, a reference librarian, an editor, or simply a First Words junkie, think of this as your "Go-To" site on the subject. In addition to learning more than you now know about your current personal favorites, this site will introduce you to thousands of future favorites you might never know about in any other way.

Dr. Mardy Grothe

Become a supporter.

My goal is to make this a completely ad-free site, but this will be possible only with sufficient financial support.

To produce a world-class website, I’d appreciate any help you can provide. Become a Site Sponsor with a one-time donation at one of four sponsorship levels, indicated below.

Make checks payable to: GreatOpeningLines.com P. O. Box 802 Southern Pines, NC 28388

Or use the electronic payment options below:

Bronze Sponsor

Silver sponsor, gold sponsor, platinum sponsor.

Table of Contents

How to Write a Great Opening Sentence

Examples of great first sentences (and how they did it), how to write a strong opening sentence & engage readers (with examples).

“I’ve never met you, but I’m gonna read your mind.”

That’s the opening line to The Scribe Method . It does what great opening sentences should: it immediately captures the reader’s attention. It makes them want to read more.

The purpose of a good opening line is to engage the reader and get them to start reading the book. That’s it.

It’s a fairly simple idea, and it works very well—but there are still a lot of misconceptions about book openings .

Many first-time Authors think they have to shock the reader to make them take note.

That’s not true. There are many ways to hook a reader that don’t require shocking them.

I also see Authors who think the purpose of the first paragraph is to explain what they’ll talk about in the book .

Not only is that wrong, it’s boring.

Readers can sense bullshit a mile away, so don’t try to beat them over the head with shock. Don’t give them a tedious summary. Don’t tell your life story. Don’t go into too much detail.

Use your first sentence to connect to the reader and make them want to keep reading.

This guide will help you write a great opening line so you can establish that authenticity and connection quickly.

Everyone knows some of the great opening lines from fiction novels:

- “Call me Ishmael.” – Herman Melville, Moby Dick

- “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” – Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

- “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” – Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

- “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way—in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.” – Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

The common thread between these opening lines is that they create a vivid first impression. They make the reader want to know more.

They’re punchy, intriguing, and unexpected.

The first words of a nonfiction book work the same way. You want to create an emotional connection with the reader so they can’t put the book down.

In some ways, nonfiction Authors even have an advantage. They’re writing about themselves and their knowledge while having a conversation with the reader.

They can establish the connection even more immediately because they don’t have to set a fictional scene. They can jump right in and use the first person “I.”

Let’s go back to The Scribe Method ‘s opening paragraph:

I’ve never met you, but I’m gonna read your mind. Not literally, of course. I’m going to make an educated guess about why you want to write a book.

When you read that, at a minimum, you’re going to think, “All right, dude, let’s see if you really know why I want to write a book .” And you’re going to keep reading.

At best, you’re going to think, “Wow. He’s inside my head right now.” And you’re going to keep reading.

In both cases, I’ve managed to create an emotional connection with the reader. Even if that emotion is skepticism, it’s enough to hook someone.

So where do you start when you’re writing your book ? How do you form that connection?

The best hooks usually start in the middle of the highest intensity.

In other words, lead with the most emotional part of the story.

If you’re starting your book with a story about how you got chased by the police, don’t begin with what you had for breakfast that day. Start with the chase.

A good hook might also be a question or a claim—anything that will elicit an emotional response from a reader.

Think about it this way: a good opening sentence is the thing you don’t think you can say, but you still want to say.

Like, “This book will change your life.”

Or, “I’ve come up with the most brilliant way anyone’s ever found for handling this problem.”

Your opening sentence isn’t the time for modesty (as long as you can back it up!).

You want to publish a book for a reason . Now’s your chance to show a reader why they should want to read it.

That doesn’t mean you have to be cocky. You just have to be honest and engaging.

When you’re trying to come up with a great opening line, ask yourself these 3 things:

- What will the audience care about, be interested in, or be surprised by?

- What is the most interesting story or inflammatory statement in your book?

- What do you have to say that breaks the rules?

The best opening lines are gut punches.

They summarize the book, at least in an oblique way. But they’re not dry facts. They’re genuine, behind-the-scenes glimpses into a human life. They establish who you are and what you’re about, right from the beginning.

Human beings respond to genuine connection. That means being vulnerable. You have to break down any barriers that you might usually keep around you.

That’s one of the hardest things to do as an Author, but it makes for a great book.

Reading about perfection is boring, especially because we all know there’s no such thing.

In the next section, I’ll go through examples of great first sentences and explain why they work.

Every one of these strategies helps create an instant, authentic connection with readers. You just have to pick the one that makes the most sense for your book.

1. Revealing Personal Information

When most people think about comedian Tiffany Haddish, they think of a glamorous celebrity.

They don’t think about a kid who had trouble in school because she had an unstable home life, reeked of onions, and struggled with bullying.

From the first line of her book, Tiffany reveals that you’re going to learn things about her that you don’t know—personal things.

I mean, really personal.

The book’s opening story concludes with her trying to cut a wart off her face because she was teased so much about it (that’s where the “unicorn” nickname came from).

That level of personal connection immediately invites the reader in. It promises that the Author is going to be honest and vulnerable, no holds barred.

This isn’t going to be some picture-perfect memoir. It’s going to be real, and it’s going to teach you something.

And that’s what forms a connection.

2. Mirroring the Reader’s Pain

Geoffrey and I chose this opening sentence because it let readers know right away that we know their pain.

Not only that, we knew how to fix it .

If a reader picked up the book and didn’t connect to that opening line, they probably weren’t our target audience.

But if someone picked it up and said, “This is exactly what I want to know!” we already had them hooked.

They would trust us immediately because we proved in the first sentence that we understood them.

In this sentence, Geoffrey and I are positioned as the experts. People are coming to us for help.

But you can also mirror your reader’s pain more directly. Check out this example from Jennifer Luzzato’s book, Inheriting Chaos with Compassion :

That’s a gut punch for anyone. But it’s an even bigger one for Jennifer’s target audience: people who unexpectedly lose a loved one and are left dealing with financial chaos.

Jennifer isn’t just giving the reader advice.

She’s showing that she’s been through the pain. She understands it. And she’s the right person to help the reader solve it.

3. Asking the Reader a Question

Readers come to nonfiction books because they want help solving a problem.

If you picked up a book about team-building, culture, and leadership, you likely want answers to some questions.

Daniel Coyle’s book shows the reader, right off the bat, that he’s going to give you answers.

His question also isn’t a boring, how-do-organizations-work type of question.

It’s compelling enough to make you keep reading, at least for a few more sentences. And then ideally, a few sentences, pages, and chapters after that.

Starting with a question is often a variation on tactic number 2.

If the reader picked up your book hoping to solve a certain problem or learn how to do something, asking them that compelling question can immediately show them that you understand their pain.

It can set the stage for the whole book.

You can also pique the reader’s interest by asking them a question they’ve never thought about.

Nicholas Kusmich ‘s book Give starts with the question,

It’s a unique question that hooks a reader.

But the answer still cuts straight to the heart of his book: “Both entrepreneurs and superheroes want to use their skills to serve people and make the world a better place.”

The unexpected framing gives readers a fresh perspective on a topic they’ve probably already thought a lot about.

4. Shock the Reader

I said in the intro to this post that you don’t have to shock the reader to get their attention.

I never said you couldn’t .

If you’re going to do it, though, you have to do it well.

This is the best opening to a book I’ve ever read. I’m actually a dog person, so this shocked the hell out of me. It was gripping.

As you read, the sentence starts making more sense, but it stays just as shocking. And you can’t help but finish the page and the chapter to understand why. But my God, what a way to hook a reader (in case you are wondering, the dogs were licking up blood from dead bodies and giving away the soldiers’ positions to insurgents. They had to kill the dogs or risk being discovered).

I read this opening sentence as part of an excerpt from the book on Business Insider .

I plowed through the excerpt, bought the book on Kindle, canceled two meetings, and read the whole book.

5. Intrigue the Reader

If you don’t read that and immediately want to know what the realization was, you’re a force to be reckoned with.

People love reading about drama, screw-ups, and revelations. By leading with one, Will immediately intrigues his readers.

They’ll want to keep reading so they can solve the mystery. What was the big deal?

I’m not going to tell you and spoil the fun. You’ll have to check out Will’s book to find out.

There are other ways to be intriguing, too. For example, see the opening line to Lorenzo Gomez’ Cilantro Diaries :

Again, the Author is setting up a mystery.

He wants the reader to rack his brain and say, “Well, if it’s not the famous stuff, what is it?”

And then, when Lorenzo gets to the unexpected answer—the H-E-B grocery store—they’re even more intrigued.

Why would a grocery store make someone’s top-ten list, much less be the thing they’d miss most?

That kind of unexpected storytelling is perfect for keeping readers engaged.

The more intrigue you can create, the more they’ll keep turning the pages.

6. Lead with a Bold Claim

There are thousands of books about marketing. So, how does an Author cut through the noise?

If you’re David Allison, you cut right to the chase and lead with a bold claim.

You tell people you’re going to change the world. And then you tell them you have the data to back it up.

If your reader is sympathetic, they’re going to jump on board. If they’re skeptical, they’re still going to want to see if David’s claim holds up.

Here’s the thing, though: only start bold if you can back it up.

Don’t tell someone you’re going to transform their whole life and only offer a minor life hack. They’ll feel cheated.

But if you’re really changing the way that people think about something, do something, or feel about something, then lead with it.

Start big. And then prove it.

7. Be Empathetic and Honest

One Last Talk is one of the best books we’ve ever done at Scribe. And it shows right from the first sentence.

Philip starts with a bold claim: “If you let it, this book will change your life.”

But then he gives a caveat: it’s not going to be fun.

That’s the moment when he forms an immediate connection with the reader.

Many Authors will tell their readers, “This book will change your life. It’s going to be incredible! Just follow these steps and be on your way!”

Not many Authors will lead with, “It’s going to be worth it, but it’s going to be miserable.”

By being this upfront about the emotional work the book involves, Philip immediately proves to his readers that he’s honest and empathetic.

He understands what they’re going to go through. And he can see them through it, even if it sucks.

One piece of advice we give at Scribe is to talk to your reader like you’re talking to a friend.

Philip does that. And it shows the reader they’re dealing with someone authentic.

8. Invite the Reader In

Joey starts the book by speaking directly to the reader.

He immediately creates a connection and invites the reader in. This makes the book feel more like a conversation between two people than something written by a nameless, faceless Author.

The reason this tactic works so well is because Joey’s whole book is about never losing a customer.

He immediately puts the book’s principles into action.

From the first sentence, Joey’s demonstrating exactly what the reader is there to learn.

The Scribe Crew

Read this next.

How to Choose the Best Book Ghostwriting Package for Your Book

How to Choose the Best Ghostwriting Company for Your Nonfiction Book

How to Choose a Financial Book Ghostwriter

Need help submitting your writing to literary journals or book publishers/literary agents? Click here! →

How To Write A Great First Line (With 12 Unforgettable Examples) (UPDATED 2024)

by Writer's Relief Staff | Craft: Memoir , Craft: Nonfiction Book , Craft: Novel Writing , Craft: Personal Essay Writing , Craft: Poetry, Poems , Craft: Short Story Writing , Creative Writing Craft and Techniques , Inspiration And Encouragement For Writers , Other Helpful Information , The Writing Life | 19 comments

Review Board is now open! Submit your Short Prose, Poetry, and Book today!

Deadline: thursday, february 22nd.

Some writers can craft the perfect first line on the very first try—and if that’s happened to you, you can bet the writing muses were in a darn good mood that day. At Writer’s Relief , we’ve worked with hundreds of authors, and we know most writers return to the first line of their novel, memoir, story, poem, or personal essay again and again, continuing to rework the opening line even after the rest of the piece is done.

To help inspire you (and give your muse a nudge), here are some examples of first lines from literature (poems, short stories, and novels) that offer great insight into opening line techniques.

Offer a pithy insight. Even people who aren’t book nerds recognize the opening line from Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina ; its wisdom is succinct, cutting, and not quickly forgotten.

Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

Be “meta.” The opening line from Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn feels bold, brazen, and shocking even to modern readers. Prequel-bait aside, this first line is hilariously self-referential, which might make Mark Twain the father of hipster irony.

You don’t know about me without you have read a book by the name of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer ; but that ain’t no matter.

Be coy. In Flannery O’Connor’s chilling story, “A Good Man Is Hard To Find,” we get an opening line that, frankly, leaves us hanging. Who is “the grandmother”? Why doesn’t she have a name? Why is she being forced to go to Florida?

The grandmother didn’t want to go to Florida.

Go for the jugular. In his epic long poem, Howl , Allen Ginsberg grabs readers by the throat with this emotional cry and protest.

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical

Lie. Lie so enormously that your lie makes readers suspicious, like Shirley Jackson did when she set an excessively bright, happy, “everything’s perfect here” tone with the first line of her short story “The Lottery.”

The morning of June 27th was clear and sunny, with the fresh warmth of a full-summer day; the flowers were blossoming profusely and the grass was richly green…

Unsettle us. George Orwell’s first line of 1984 starts off like a typical opening sentence but ends with an unexpected twist, giving readers a creepy, “I’m missing something here” feeling. (And in a few lines, we also get an even creepier “I’m being watched” feeling too.)

It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.

I’m still not sure I made the right choice when I told my wife about the bakery attack.

Go for in media res . This term means the author drops the character smack into the middle of a progressing scene—or in the case of The Secret Life of Walter Mitty , it just looks like that’s what’s happening. (See what James Thurber’s doing there?)

“We’re going through!” The Commander’s voice was like thin ice breaking.

Cue the peril. In her book Twilight, Stephanie Meyer teases readers with a life-and-death, in-media-res prologue that won’t fully manifest for a few hundred pages.

I’d never given much thought to how I would die—though I’d had reason enough in the last few months—but even if I had, I would not have imagined it like this.

Be obscure. T.S. Eliot’s first line of The Waste Land is a bit perplexing at first glance; you must keep reading to understand the author’s (seemingly counterintuitive) point. How could April—glorious, warming, colorful April—be cruel?

April is the cruellest month.

Lead with character. In his book Middlesex , Jeffrey Eugenides pulls us into the plight of his main character with just a few tantalizing, heart-wrenching words.

I was born twice: first, as a baby girl, on a remarkably smogless Detroit day in January of 1960; and then again, as a teenage boy, in an emergency room near Petoskey, Michigan, in August of 1974.

Last things first. In David Copperfield, Charlie Dickens doesn’t make us slowly journey alongside of his main character to discover the character’s inner emotional conflict; he gives us a hint of the final showdown right up front.

Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.

And One Important Thing To Remember About Your First Line

Your opening line doesn’t exist in a vacuum; it needs to set to tone for the rest of your book, story, or poem. First lines are so important (and fun), there’s an entire publication dedicated to works that start with the same first line .

But don’t put too much pressure on yourself to start out with a great line when you’re just beginning a new project. Sometimes, your first line will be the last one you write!

Once you’ve completed your masterpiece (and your first line), it’s time to submit your work to literary agents and journal editors. The research experts at Writer’s Relief can help you target the very best markets for your work and boost your odds of getting published! With over twenty-nine years of experience, we can pinpoint where you should—and where you shouldn’t—submit your work. Learn more about our services and submit your writing sample to our Review Board today!

In addition to helping clients navigate and submit their work via traditional publishing paths, we also provide affordable and expert self-publishing options. We understand writers and their publishing goals.

19 Comments

My first line: The sickening sound of bones cracking as Sarwa’a hit the wall galvanized Hikala’a into action.

CC: Melodious, flowery, adverbial and adjective fluff. Feels cliche, too. (“sickening sound of bones cracking”? ya-da, ya-da) What bones (or at least, what body part(s))? What did Hikala’a STOP doing in order to get “into action”?

“The crack of Sarwa’a’s arm breaking against the wall shook Hikala’a out of his numbaqua.” (You can define whether that’s “indecision about an action” or “state of focusing on something that’s been said to the exclusion of all other awareness” or what have you a few paragraphs later)

My intro “I like cows because of their color pattern… and other reasons!” – thoughts?

Suzanne tossed the bloodied knife into the sink, not bothering to wash it off.

Whoever came up with that ‘Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all’ line was full of it!

Hi, I am writing for the first time and is my first sentence any good?

First Line: It was a hot October Sunday, and the Carpenters were sitting around, having nothing to do. The Carpenter household was like any other on Pearl Street, boring and bland. But they thought that somehow they are at the center of attention.

Any suggestions? Leave ANY comments:

Some really great examples here – I can never make up my mind as to whether the greatest-of-all-time is 1984 or Anna Karenina. Both perfect and beautiful, though so different. Thank you so much for giving these examples alongside tangible advice for how and why to make them work in your own writing, really well done 🙂

My first line, “They tried to pin a murder one me, little old me who couldn’t swat a fly. Not sober anyway”. My book was called Bedlam. Never got published. Never mind, tomorrow is another day.

Great examples, my favourite from your article has to be 1984, it certainly makes you sit up and pay attention. Middlesex is a close second, a great book, really moving. Another that stands out for me is from The Secret History by Donna Tartt, “The snow in the mountains was melting and Bunny had been dead for several weeks before we came to understand the gravity of our situation.” It throws you in at the deep end and then lets you slowly find out what happened to Bunny over the next few hundred pages!

“Hey girl throw me some beads. Throw me some beads for my horse too.”

First line to my book.

I’m writing my first novel and so excited. My first line, please be brutally honest. “He was bored, the ragee coursing through his veins, he was ready.” Tell me what you think. You’re the first I’ve ever asked.

My first line: My mother used to say that only wild girls grew beautifully.

Does it sound too… farfetched, like I’m trying to present an idea, but only giving half of the information?

The first paragraph of my far-future science fiction novel:

“The Civilization appeared very briefly in the avatar of an Late Archaic Human female, clad in a severely cut gray dress with black button-up shoes, gray hair tightly done up in a bun, and a pair of lenses attached to wire precariously perched on her nose. And then she vanished as swiftly as she had appeared.”

Dix insists that the severed fingers started it, but it’s who I am, and who Dix is, that got us in so deep and nearly killed us in the process.

I’d love to hear anyone’s thoughts on the first sentence of my mystery novel. “Although I was thoroughly shaken by the note, all sticky-taped to my bedroom window, in red ink and all, my wonder is how someone could’ve gotten it there when our house is halfway off a cliff?”

First Line. Adriana awoke hearing the sound of her alarm clock ringing and the phone, in unison! She was grumpy before coffee and really didn’t want to answer her phone just yet.

Sorry this is 3 years too late but would hate to learn that you were discouraged from continuing your writing based on the comments from Wendy She clearly knows little about language. “Adverbial and adjective fluff” is objectively wrong. There is not one adverb in your opening sentence, for instance. And there is no need to specify which bones were broken nor what Hikala’a was doing. Your opening is fine and will move a reader to read on. Wendy seems to be a bit full of herself and doesn’t know the parts of speech. Good luck, CC! Don’t ever let anyone stop you from writing.

I just published my first book and I am 79. The first line of the story: Sybile knew Satan was genuine. My book is titled, “Ride The Dark Rails.” It is 12 short stories about, murder, revenge, and all is not what it seems.

I told my wife no one knows who I am, and I am looking for readers of my stories and not doing this for the money.

Congratulations, Richard!

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

See ALL the services we offer, from FREE to Full Service!

Click here for a Writer’s Relief Full Service Overview

Services Catalog

Free Publishing Leads and Tips!

- Name * First Name

- Email * Enter Email Confirm Email

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Featured Articles

Featured Video

- Facebook 121k Followers

- Twitter 114k Followers

- YouTube 5k Followers

- Instagram 5.5k Followers

- LinkedIn 145.8k Followers

- Pinterest 33.5k Followers

- Name * First

- E-mail * Enter Email Confirm Email

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

WHY? Because our insider know-how has helped writers get over 18,000 acceptances.

- BEST (and proven) submission tips

- Hot publishing leads

- Calls to submit

- Contest alerts

- Notification of industry changes

- And much more!

Pin It on Pinterest

Great Opening Lines and Why They Work So Darn Well

It is a truth universally acknowledged that an article on great opening lines must be in want of a spoofed Jane Austen quote.

Actually, that approach might be a little played out, making it a less-than-stellar opener. But that’s okay, because today we’re here to learn. It takes a lot of writing and rewriting to find the perfect first sentence.

So how do you know when you’ve landed on a gem?

You’re about to find out. Using several examples of exceptional novel openers, we’re going to explore:

- What makes an opening line great

- Four types of first lines

- How to craft your own unforgettable story starter

First, let’s establish why we care about any of this.

Why Great Opening Lines Matter

The answer to this is delightfully straightforward:

Your opening line matters because it’s your first opportunity to draw the reader in.