Common Sense Media

Movie & TV reviews for parents

- For Parents

- For Educators

- Our Work and Impact

Or browse by category:

- Get the app

- Movie Reviews

- Best Movie Lists

- Best Movies on Netflix, Disney+, and More

Common Sense Selections for Movies

50 Modern Movies All Kids Should Watch Before They're 12

- Best TV Lists

- Best TV Shows on Netflix, Disney+, and More

- Common Sense Selections for TV

- Video Reviews of TV Shows

Best Kids' Shows on Disney+

Best Kids' TV Shows on Netflix

- Book Reviews

- Best Book Lists

- Common Sense Selections for Books

8 Tips for Getting Kids Hooked on Books

50 Books All Kids Should Read Before They're 12

- Game Reviews

- Best Game Lists

Common Sense Selections for Games

- Video Reviews of Games

Nintendo Switch Games for Family Fun

- Podcast Reviews

- Best Podcast Lists

Common Sense Selections for Podcasts

Parents' Guide to Podcasts

- App Reviews

- Best App Lists

Social Networking for Teens

Gun-Free Action Game Apps

Reviews for AI Apps and Tools

- YouTube Channel Reviews

- YouTube Kids Channels by Topic

Parents' Ultimate Guide to YouTube Kids

YouTube Kids Channels for Gamers

- Preschoolers (2-4)

- Little Kids (5-7)

- Big Kids (8-9)

- Pre-Teens (10-12)

- Teens (13+)

- Screen Time

- Social Media

- Online Safety

- Identity and Community

Explaining the News to Our Kids

- Family Tech Planners

- Digital Skills

- All Articles

- Latino Culture

- Black Voices

- Asian Stories

- Native Narratives

- LGBTQ+ Pride

- Best of Diverse Representation List

Celebrating Black History Month

Movies and TV Shows with Arab Leads

Celebrate Hip-Hop's 50th Anniversary

What is media literacy, and why is it important?

The word "literacy" usually describes the ability to read and write. Reading literacy and media literacy have a lot in common. Reading starts with recognizing letters. Pretty soon, readers can identify words -- and, most importantly, understand what those words mean. Readers then become writers. With more experience, readers and writers develop strong literacy skills. ( Learn specifically about news literacy .)

Media literacy is the ability to identify different types of media and understand the messages they're sending. Kids take in a huge amount of information from a wide array of sources, far beyond the traditional media (TV, radio, newspapers, and magazines) of most parents' youth. There are text messages, memes, viral videos, social media, video games, advertising, and more. But all media shares one thing: Someone created it. And it was created for a reason. Understanding that reason is the basis of media literacy. ( Learn how to use movies and TV to teach media literacy. )

The digital age has made it easy for anyone to create media . We don't always know who created something, why they made it, and whether it's credible. This makes media literacy tricky to learn and teach. Nonetheless, media literacy is an essential skill in the digital age.

Specifically, it helps kids:

Learn to think critically. As kids evaluate media, they decide whether the messages make sense, why certain information was included, what wasn't included, and what the key ideas are. They learn to use examples to support their opinions. Then they can make up their own minds about the information based on knowledge they already have.

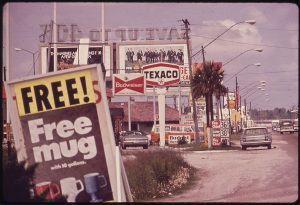

Become a smart consumer of products and information. Media literacy helps kids learn how to determine whether something is credible. It also helps them determine the "persuasive intent" of advertising and resist the techniques marketers use to sell products.

Recognize point of view. Every creator has a perspective. Identifying an author's point of view helps kids appreciate different perspectives. It also helps put information in the context of what they already know -- or think they know.

Create media responsibly. Recognizing your own point of view, saying what you want to say how you want to say it, and understanding that your messages have an impact is key to effective communication.

Identify the role of media in our culture. From celebrity gossip to magazine covers to memes, media is telling us something, shaping our understanding of the world, and even compelling us to act or think in certain ways.

Understand the author's goal. What does the author want you to take away from a piece of media? Is it purely informative, is it trying to change your mind, or is it introducing you to new ideas you've never heard of? When kids understand what type of influence something has, they can make informed choices.

When teaching your kids media literacy , it's not so important for parents to tell kids whether something is "right." In fact, the process is more of an exchange of ideas. You'll probably end up learning as much from your kids as they learn from you.

Media literacy includes asking specific questions and backing up your opinions with examples. Following media-literacy steps allows you to learn for yourself what a given piece of media is, why it was made, and what you want to think about it.

Teaching kids media literacy as a sit-down lesson is not very effective; it's better incorporated into everyday activities . For example:

- With little kids, you can discuss things they're familiar with but may not pay much attention to. Examples include cereal commercials, food wrappers, and toy packages.

- With older kids, you can talk through media they enjoy and interact with. These include such things as YouTube videos , viral memes from the internet, and ads for video games.

Here are the key questions to ask when teaching kids media literacy :

- Who created this? Was it a company? Was it an individual? (If so, who?) Was it a comedian? Was it an artist? Was it an anonymous source? Why do you think that?

- Why did they make it? Was it to inform you of something that happened in the world (for example, a news story)? Was it to change your mind or behavior (an opinion essay or a how-to)? Was it to make you laugh (a funny meme)? Was it to get you to buy something (an ad)? Why do you think that?

- Who is the message for? Is it for kids? Grown-ups? Girls? Boys? People who share a particular interest? Why do you think that?

- What techniques are being used to make this message credible or believable? Does it have statistics from a reputable source? Does it contain quotes from a subject expert? Does it have an authoritative-sounding voice-over? Is there direct evidence of the assertions its making? Why do you think that?

- What details were left out, and why? Is the information balanced with different views -- or does it present only one side? Do you need more information to fully understand the message? Why do you think that?

- How did the message make you feel? Do you think others might feel the same way? Would everyone feel the same, or would certain people disagree with you? Why do you think that?

- As kids become more aware of and exposed to news and current events , you can apply media-literacy steps to radio, TV, and online information.

Common Sense Media offers the largest, most trusted library of independent age-based ratings and reviews. Our timely parenting advice supports families as they navigate the challenges and possibilities of raising kids in the digital age.

- Get started with computers

- Learn Microsoft Office

- Apply for a job

- Improve my work skills

- Design nice-looking docs

- Getting Started

- Smartphones & Tablets

- Typing Tutorial

- Online Learning

- Basic Internet Skills

- Online Safety

- Social Media

- Zoom Basics

- Google Docs

- Google Sheets

- Career Planning

- Resume Writing

- Cover Letters

- Job Search and Networking

- Business Communication

- Entrepreneurship 101

- Careers without College

- Job Hunt for Today

- 3D Printing

- Freelancing 101

- Personal Finance

- Sharing Economy

- Decision-Making

- Graphic Design

- Photography

- Image Editing

- Learning WordPress

- Language Learning

- Critical Thinking

- For Educators

- Translations

- Staff Picks

- English expand_more expand_less

Digital Media Literacy - Recognizing Persuasive Language

Digital media literacy -, recognizing persuasive language, digital media literacy recognizing persuasive language.

Digital Media Literacy: Recognizing Persuasive Language

Lesson 10: recognizing persuasive language.

/en/digital-media-literacy/the-problem-with-photo-manipulation/content/

Recognizing persuasive language

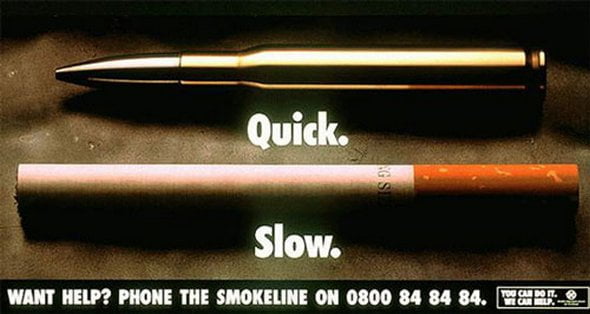

Persuasive language can make any type of media more engaging and convincing. However, its ultimate purpose is to win your trust and influence how you think . This is why it’s important to recognize common types of persuasive language so you can look beyond the rhetoric and think for yourself.

Watch the video below for more on recognizing persuasive language.

Telling stories

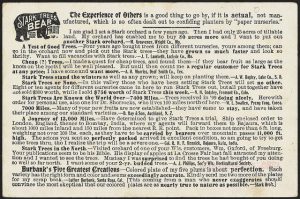

Whether it's a feature-length film or a 30-second commercial, telling stories through media makes it easier for you to agree with a particular message. But while it’s easy to be charmed by a good story, ask yourself: Is the tale fair and unbiased , or has it sacrificed factual accuracy for the sake of serving the message?

Presenting evidence

Presenting evidence can have a tremendous influence on how you perceive a message. However, just because the media includes evidence doesn’t mean it's being completely honest. Sometimes facts will be mixed in with half-truths and exaggerations to make the message seem more credible. Take care to examine all evidence before accepting a message as trustworthy.

Attacks can point out the faults of the competition, and they often provoke an audience’s fears or anger, especially in political media. The next time you see an attack, keep in mind that it’s trying to rile your emotions to convince you of a specific idea. It may also embellish facts or take a skewed perspective, so try not to pass judgment before investigating the truth.

Flattery has long been a reliable persuasion method, particularly if the media wants you to feel good about a specific product or idea. But how sincere can mass-produced praise actually be? Do your best not to be lured in by kind words, and consider if the media is just telling you what you want to hear.

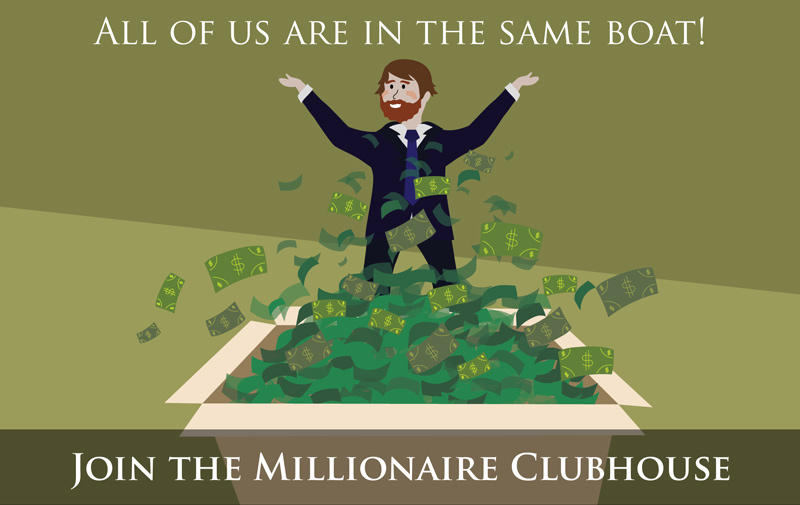

Inclusive language

Inclusive language frames a message in terms of us and we and our , giving the impression that the creator of the media and the audience are on the same side. However, this can come off as false and hollow, especially if it appears that the creator doesn’t actually have anything in common with you.

Whether it’s used to reinforce the truth or hide a lack of substance, don’t let persuasive language be the only thing that sways your opinion. Always look beyond the rhetoric and seek out the facts behind any claims.

/en/digital-media-literacy/the-blur-between-facts-and-opinions-in-the-media/content/

Media and Information Literacy, a critical approach to literacy in the digital world

What does it mean to be literate in the 21 st century? On the celebration of the International Literacy Day (8 September), people’s attention is drawn to the kind of literacy skills we need to navigate the increasingly digitally mediated societies.

Stakeholders around the world are gradually embracing an expanded definition for literacy, going beyond the ability to write, read and understand words. Media and Information Literacy (MIL) emphasizes a critical approach to literacy. MIL recognizes that people are learning in the classroom as well as outside of the classroom through information, media and technological platforms. It enables people to question critically what they have read, heard and learned.

As a composite concept proposed by UNESCO in 2007, MIL covers all competencies related to information literacy and media literacy that also include digital or technological literacy. Ms Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO has reiterated significance of MIL in this media and information landscape: “Media and information literacy has never been so vital, to build trust in information and knowledge at a time when notions of ‘truth’ have been challenged.”

MIL focuses on different and intersecting competencies to transform people’s interaction with information and learning environments online and offline. MIL includes competencies to search, critically evaluate, use and contribute information and media content wisely; knowledge of how to manage one’s rights online; understanding how to combat online hate speech and cyberbullying; understanding of the ethical issues surrounding the access and use of information; and engagement with media and ICTs to promote equality, free expression and tolerance, intercultural/interreligious dialogue, peace, etc. MIL is a nexus of human rights of which literacy is a primary right.

Learning through social media

In today’s 21 st century societies, it is necessary that all peoples acquire MIL competencies (knowledge, skills and attitude). Media and Information Literacy is for all, it is an integral part of education for all. Yet we cannot neglect to recognize that children and youth are at the heart of this need. Data shows that 70% of young people around the world are online. This means that the Internet, and social media in particular, should be seen as an opportunity for learning and can be used as a tool for the new forms of literacy.

The Policy Brief by UNESCO Institute for Information Technologies in Education, “Social Media for Learning by Means of ICT” underlines this potential of social media to “engage students on immediate and contextual concerns, such as current events, social activities and prospective employment.

UNESCO MIL CLICKS - To think critically and click wisely

For this reason, UNESCO initiated a social media innovation on Media and Information Literacy, MIL CLICKS (Media and Information Literacy: Critical-thinking, Creativity, Literacy, Intercultural, Citizenship, Knowledge and Sustainability).

MIL CLICKS is a way for people to acquire MIL competencies in their normal, day-to-day use of the Internet and social media. To think critically and click wisely. This is an unstructured approach, non-formal way of learning, using organic methods in an online environment of play, connecting and socializing.

MIL as a tool for sustainable development

In the global, sustainable context, MIL competencies are indispensable to the critical understanding and engagement in development of democratic participation, sustainable societies, building trust in media, good governance and peacebuilding. A recent UNESCO publication described the high relevance of MIL for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

“Citizen's engagement in open development in connection with the SDGs are mediated by media and information providers including those on the Internet, as well as by their level of media and information literacy. It is on this basis that UNESCO, as part of its comprehensive MIL programme, has set up a MOOC on MIL,” says Alton Grizzle, UNESCO Programme Specialist.

UNESCO’s comprehensive MIL programme

UNESCO has been continuously developing MIL programme that has many aspects. MIL policies and strategies are needed and should be dovetailed with existing education, media, ICT, information, youth and culture policies.

The first step on this road from policy to action is to increase the number of MIL teachers and educators in formal and non-formal educational setting. This is why UNESCO has prepared a model Media and Information Literacy Curriculum for Teachers , which has been designed in an international context, through an all-inclusive, non-prescriptive approach and with adaptation in mind.

The mass media and information intermediaries can all assist in ensuring the permanence of MIL issues in the public. They can also highly contribute to all citizens in receiving information and media competencies. Guideline for Broadcasters on Promoting User-generated Content and Media and Information Literacy , prepared by UNESCO and the Commonwealth Broadcasting Association offers some insight in this direction.

UNESCO will be highlighting the need to build bridges between learning in the classroom and learning outside of the classroom through MIL at the Global MIL Week 2017 . Global MIL Week will be celebrated globally from 25 October to 5 November 2017 under the theme: “Media and Information Literacy in Critical Times: Re-imagining Ways of Learning and Information Environments”. The Global MIL Feature Conference will be held in Jamaica under the same theme from 24 to 27 October 2017, at the Jamaica Conference Centre in Kingston, hosted by The University of the West Indies (UWI).

Alton Grizzle , Programme Specialist – Media Development and Society Section

Other recent news

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Current Events

Teenagers and Misinformation: Some Starting Points for Teaching Media Literacy

Five ideas to help students understand the problem, learn basic skills, share their experiences and have a say in how media literacy is taught.

By Katherine Schulten

In a sense, every week is Media Literacy Week on a site like ours, which helps people teach and learn with the news. But Oct. 24-28 is the official week dedicated to “amplifying the importance of media literacy education across the United States.” We are delighted to help.

Here are some ways teachers and librarians can teach with the extensive reporting The New York Times has done recently on misinformation and disinformation, whether your students are just beginning to understand the problem, or whether they are ready for deeper inquiry.

1. Get the big picture: What is media literacy education? Why do we need it?

If you have time for just one activity, this one, based on the Times article “ When Teens Find Misinformation, These Teachers Are Ready ,” can provide a broad overview and help frame future work.

To start, share the statements in italics, all adapted from the article. You can do this as a “ Four Corners ” exercise in which you read each line aloud and ask students to position themselves in the room according to whether they strongly agree, agree, disagree or strongly disagree. Or, you can hand out the PDF version and have students mark each statement “true” or “false” based on their own experiences, then discuss their reactions — and the experiences that informed those reactions — in partners or small groups.

Here are the statements:

It’s easy to look at stuff on social media and take it as it is and not question it.

Older adults are more likely to struggle to recognize fake news than young people and are also the most likely to share it.

I have come across misleading and false narratives about the upcoming midterm elections online.

I have come across misleading and false narratives about the Covid-19 pandemic online.

If it’s gone viral, it’s probably true.

A .org domain makes a website trustworthy.

Media literacy is a necessity for everyone because of the way we live online today.

Some young adults share misinformation because they think it is true.

Some young adults share misinformation impulsively, because they are too busy to verify the information.

Most young adults talk to their parents and guardians about what makes media sources trustworthy.

TikTok is a primary information source for people my age.

Social media often reduces complex issues to one-sentence explanations.

A lot of young people are politically polarized at a very young age, and are angry at anyone who believes differently than they do.

Media literacy education should start in middle or even elementary school, when children are just beginning to venture online.

The way media literacy is taught needs improvement.

After your students have finished the exercise, discuss as a class what you discovered. On which statements was there broad agreement? On which was there disagreement? Why do they think that was? What personal experiences would they like to share that helped inform how they feel about the subject of “media literacy”? What, if anything, do they think schools, teachers and librarians should do to improve how they teach about these topics?

Finally, have them read “ When Teens Find Misinformation, These Teachers Are Ready ,” perhaps annotating to note their reactions as they go. You might then ask:

1. What jumped out at you as you read? Why?

2. This article describes many ideas, including curriculums, games and even legislative initiatives, that have been tried in recent years to support media literacy in public schools. Which of these, if any, were familiar to you? Which, if any, do you wish our school could adopt?

3. What problems with teaching media literacy did this article identify? Do you think our school has experienced any of these struggles? If so, what should we do about them? Why?

Then, to take the discussion further, you might continue to some of the exercises below.

2. Have students share their experiences and opinions — and offer adults advice .

What don’t adults understand about teenage life on the internet?

How, if at all, can schools help?

Via our Student Opinion column , we ask teenagers a new question every school day based on something in the news, and thousands of young people from around the world post comments in reaction every month.

For Media Literacy Week, we have published a forum that invites teenagers to answer questions like the two above , and encourages them to share experiences and opinions about what it’s like to navigate their digital lives in 2022. We ask them about their media literacy education so far, and invite them to offer adults advice for how to make it more relevant, interesting and useful.

If your students have thoughts about any of these topics, we hope they’ll join the conversation, either by posting a comment, or by replying to comments from others.

3. Learn from teen fact-checkers.

The video above is from the MediaWise Teen Fact-Checking Network , which publishes fact-checks for teenagers, by teenagers. According to the site, the network’s “fact-checks are unique in that they debunk misinformation and teach the audience media literacy skills so they can fact-check on their own.” Here is a collection of some recent fact-checks they have done, but you can see more on Instagram , YouTube , Twitter and Facebook . You can also find a related “toolkit” of lesson plans to help.

What skills do these students use? Among others, they have mastered lateral reading, a quick and effective method mentioned in the article students read above.

Mike Caulfield, a digital literacy expert, explained the rationale for that method in a 2021 interview with Charlie Warzel, a former Times opinion writer. In “ Don’t Go Down the Rabbit Hole ,” Mr. Caulfield argues that the way we’re taught from a young age to evaluate and think critically about information is fundamentally flawed and out of step with the chaos of the current internet:

“We’re taught that, in order to protect ourselves from bad information, we need to deeply engage with the stuff that washes up in front of us,” Mr. Caulfield told me recently. He suggested that the dominant mode of media literacy (if kids get taught any at all) is that “you’ll get imperfect information and then use reasoning to fix that somehow. But in reality, that strategy can completely backfire.” In other words: Resist the lure of rabbit holes, in part, by reimagining media literacy for the internet hellscape we occupy. It’s often counterproductive to engage directly with content from an unknown source, and people can be led astray by false information. Influenced by the research of Sam Wineburg, a professor at Stanford, and Sarah McGrew, an assistant professor at the University of Maryland, Mr. Caulfield argued that the best way to learn about a source of information is to leave it and look elsewhere , a concept called lateral reading .

Invite your students to read the full piece. In it, they will learn how Mr. Caulfield has refined the process fact-checkers use into four simple principles:

1. S top. 2. I nvestigate the source. 3. F ind better coverage. 4. T race claims, quotes and media to the original context. Otherwise known as SIFT.

To go deeper, students might first watch a Crash Course video about lateral reading, then learn how to put it into practice via Stanford’s Civic Online Reasoning site . You might then invite them to practice it with information they come across in their social media feeds. What are the benefits of this approach? What are the limits? How well does it arm them to navigate information on their own, outside of school?

Finally, they might either revisit the Teen Fact-Checking Network to identify where they see those skills in action or, if they are ready, produce their own videos that fact-check the information they find in their feeds.

4. Invite students to investigate your school’s media literacy offerings and make recommendations.

Does your school have a media literacy program? How effective is it? Invite your students to investigate and make recommendations, perhaps by starting with questions like these, and involving your school librarian or media specialist:

What is our school doing to teach media literacy?

Is it working? How can we measure that?

Does it teach students skills they will actually use to evaluate information they come across in their private lives as well as at school? Does it work for all the places and ways students access information, or does it need broadening or updating somehow?

Identifying the problem is, of course, a lot easier than solving it, but your students’ next step might be to learn about what has been effective elsewhere. Articles like the one we recommend in Step 1 include ideas for how schools and regions in the United States are tackling the problem, and this Opinion piece further details ideas from Finland and Estonia.

What additional ideas can your students find by researching? Which might work for their school? Why? If they were to write up a set of recommendations to share with school leaders, what would those recommendations include?

5. Help students “access, analyze, evaluate, create, and act” with these additional resources.

One of the winning videos from The Learning Network’s 2018 “ News Diet Challenge ” for teenagers.

The National Association for Media Literacy Education (NAMLE) defines media literacy as “the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, create, and act using all forms of communication.”

Here are ways to do that — via The Learning Network, The New York Times and some trusted outside sources.

Apply Key Media Literacy Questions to Information of All Kinds

How credible is this and how do I know?

Is this fact, opinion, or something else?

Can I trust this source to tell me the truth about this topic?

Who might benefit from this message? Who might be harmed by it?

How does this make me feel and how do my emotions influence my interpretation of this?

How might different people understand this message differently?

Is this message good for me or people like me?

Those are the questions that NAMLE suggests students ask when evaluating media , and you can find similarly useful information and questions in their short guides to how to access , analyze , create and act on media. Invite them to practice answering them as they apply the information that crosses their screens, whether articles in The New York Times, advertising, memes on social media, or anything else. To help, we have posted all the questions on this PDF.

Use The Learning Network’s Journalism and Media Literacy Collection

All of our daily and weekly features — including multimedia activities like What’s Going On in This Picture? , our lesson plans and our many annual student contests — are focused on media literacy and help young people “access, analyze, evaluate, create and act.” But our Journalism and Media Literacy page collects resources that are especially focused on helping students understand how the news is created, and how it can be safely consumed.

For example, here are some things you can find:

An idea from a teacher-reader: News Groups: A Simple but Powerful Media Literacy Idea to Build Community

A lesson plan tied to a student contest: Improving Your ‘News Diet’: A Three-Step Lesson Plan for Teenagers and Teachers

Tips for students from Times journalists: Want to Write a Review? Here’s Advice From New York Times Critics.

A writing prompt: Do You Think Online Conspiracy Theories Can Be Dangerous?

Keep Up With Times Reporting on Misinformation and Disinformation

The New York Times has an entire team of reporters covering misinformation and disinformation.

For instance, do your students know that the qualities that allow TikTok to fuel viral dance fads are also making it a “ primary incubator of baseless and misleading information ”? The articles below explore how:

For Gen Z, TikTok Is the New Search Engine

On TikTok, Election Misinformation Thrives Ahead of Midterms

TikTok Is Flooded With Health Myths. These Creators Are Pushing Back.

Toxic and Ineffective: Experts Warn Against ‘Herbal Abortion’ Remedies on TikTok

TikTok Is Gripped by the Violence and Misinformation of Ukraine War

Snorting Crushed Porcelain, Face Reveals and a TikTok Lawsuit

Wasn’t TikTok Supposed to Be Fun?

Find Additional Resources Through These Media Literacy Organizations

The description below each link was taken from the sites themselves.

The Stanford History Education Group’s Civic Online Reasoning Curriculum

Students are confused about how to evaluate online information. We all are. The COR curriculum provides free lessons and assessments that help you teach students to evaluate online information that affects them, their communities and the world.

National Association for Media Literacy Education

The association aims to make media literacy highly valued and widely practiced as an essential life skill. It envisions a day when everyone, in our nation and around the world, possesses the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, create and act using all forms of communication. Media literacy education refers to the practices necessary to foster these skills.

The News Literacy Project

This nonpartisan education nonprofit is building a national movement to advance the practice of news literacy throughout American society, creating better-informed, more engaged and more empowered individuals — and ultimately a stronger democracy.

KQED’s Above the Noise

A YouTube series for teens, Above the Noise cuts through the hype and dives deep into the research behind the issues affecting their daily lives. The series investigates controversial subject matter to help young viewers draw their own informed conclusions, while inspiring media literacy and civic engagement. Teachers can also find related lesson plans.

Media Literacy Now

This group leverages the passion and resources of the media literacy community to inform and drive policy change at local, state and national levels in the United States to ensure all K-12 students are taught media literacy so that they become confident and competent media consumers and creators.

The Media Education Foundation

The foundation produces and distributes documentary films and other educational resources to inspire critical thinking about the social, political and cultural impact of American mass media.

Common Sense Education

This organization provides a variety of media literacy resources including courses and curriculum, research on media literacy, a news and media literacy resource center as well as a list of other media literacy organizations worth exploring.

News Decoder

This site partners with schools around the world to teach media literacy and journalistic skills that enable students to create and consume media responsibly.

Find more lesson plans and teaching ideas here.

Katherine Schulten has been a Learning Network editor since 2006. Before that, she spent 19 years in New York City public schools as an English teacher, school-newspaper adviser and literacy coach. More about Katherine Schulten

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

16 The Psychology Underlying Media-Based Persuasion

Robin L. Nabi, Department of Communication, University of California, Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA

Emily Moyer-Gusé, School of Communication, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH

- Published: 28 January 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Attempts at persuasion are as ubiquitous as the media often used to disseminate them. However, to explore persuasion in the context of media, we must first consider the psychological processes and mechanisms that underlie persuasive effects generally, and then assess how those strategies might apply in both traditional as well as more innovative media. This chapter overviews three dominant frameworks of persuasion (cognitive response models, expectancy value theories, and emotional appeals), along with three more subtle forms of influence (framing, narrative, and product placement) to explore how psychological theory and media effects research intersect to shed light on media-based persuasive influence.

Introduction

Attempts at persuasion are as ubiquitous as the media often used to disseminate them. Given that decades of persuasion research has documented just how challenging it can be to alter the beliefs, attitudes, and especially the behaviors of others, it is unsurprising that media strategies have evolved in response to emerging technologies to help overcome barriers to persuasion, thus yielding the modern persuasive forms of, for example, infomercials, product placement, and viral videos. But ultimately the psychological theories of how people process such messages are relatively indifferent to the messages’ particular forms. That is, despite the rapid changes in media forms and modes of transmission, the theories used to understand their effects remain largely unchanged. Thus, to explore persuasion in the context of media, we must first consider the psychological processes and mechanisms that underlie persuasive effects generally, and then assess how those strategies might apply to both traditional as well as more innovative media, with an eye toward useful avenues for theoretical advancement. Given the vastness of the topic of persuasion has been well-addressed in volumes previously (e.g., Eagly & Chaiken, 1993 ; Dillard & Pfau, 2002 ; Perloff, 2010 ), we will not attempt to offer a comprehensive review of the extant psychological research on persuasion here. Rather, we focus on the theoretical frameworks most directly linked to current research in media effects, how these theories have been applied in media contexts, and issues that might prove fruitful for future examination.

Although many definitions of persuasion exist, they tend to share several common elements. Persuasion is typically understood as a process whereby a message sender intends to influence an (uncoerced) message receiver's evaluative judgments regarding a particular object. Given media effects research tends to emphasize the unintended and often negative influence of media content on receivers, we wish to be clear that this chapter focuses exclusively on intentional effects at persuasion rather than the incidental social influence that might occur as a result of mass media exposure.

There are a number of classes of persuasion theories that focus on a range of psychological mechanisms driving influence that might be applied to the study of media effects. However, there are three theoretical orientations that have received substantial attention from media effects scholars interested in more direct and obvious attempts at persuasion, such as advertisements or public service announcements: cognitive response models, expectancy-value theories, and emotional appeals. Further, there are three additional frameworks that have been given particular attention in the context of more subtle, although arguably more powerful, forms of media-based persuasive influence: framing, narrative, and product placement. This chapter reviews the literature in each of these areas, with particular attention to how such research might evolve in response to the ever-changing media environment.

Theory Underlying Mediated Persuasive Appeals

As noted, a plethora of theories and models have been applied in media contexts, but three stand out as guiding the discussion of media influence: cognitive response models, expectancy-value theories, and fear appeals. We address each one in turn.

Cognitive Response Models of Persuasion

Cognitive response models of persuasion assume that the thoughts people have during message exposure drive their subsequent attitudes. As such, message recipients are viewed as active participants whose cognitive reactions mediate the influence of a persuasive attempt. Most notable among these models is Petty and Cacioppo's ( 1986 ) elaboration likelihood model (ELM) of persuasion, which suggests two possible routes to persuasion—central and peripheral. If sufficient processing motivation and ability are present, central processing is expected to occur during which the receiver will give thoughtful consideration to the arguments and information presented. The ratio of favorable to unfavorable cognitive responses generated about the message is then expected to predict persuasive outcome. If either processing motivation or ability is impaired, the receiver is expected to engage in peripheral processing during which simple, though not necessarily relevant, cues present in the persuasive setting will influence attitudinal response.

Petty and Cacioppo ( 1986 ) note that because greater message elaboration is expected to generate more thoughts that are then incorporated into cognitive schema, attitude change based on central processing is expected to be more stable, enduring, and predictive of behavior than attitude change based on peripheral processing. The nature and valence of the cognitive responses generated during central processing may be guided by a range of factors, including initial attitude, prior knowledge, personality factors, and mood. Moreover, they acknowledge that biased processing may occur to the extent various factors, particularly initial attitude, influence motivation or ability to process the message, resulting in more or less favorable thoughts about the object than might have been expected otherwise.

The ELM has been tested in numerous lab studies, the results of which tend to support its predictions (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993 ). However, several important theoretical and empirical criticisms have been launched against it, including the dichotomy between central and peripheral processing, the tautological definition of argument strength, and the inability to specify a priori whether particular message features will be processed centrally or peripherally (Stiff, 1986 ; Stiff & Boster, 1987 ; and responses by Petty, Cacioppo, Kasmer, & Haugtvedt, 1987 and Petty, Kasmer, Haugtvedt, & Cacioppo, 1987 ; also, see Eagly & Chaiken, 1993 ). The ELM has not been appreciably modified in light of these criticisms; however, the notion of thought confidence influencing outcomes was introduced in the early 2000s, suggesting that confidence in one's thoughts about the message intensifies their effect (i.e., confidence in favorable thoughts enhances persuasion and confidence in unfavorable ones detracts) (Petty, Brinol, & Tormala, 2002 ). However, this element of the model has seen little additional attention in the extant research since its introduction.

Chaiken's heuristic-systematic model (HSM) of persuasion offers a similar, although more clearly specified dual-processing approach. The HSM suggests that accuracy-motivated people may assess message validity through two types of message processing—heuristic and systematic—which may operate concurrently depending on the receiver's judgmental confidence threshold for a particular issue (Chaiken, 1980 , 1987 ; Chaiken, Liberman, & Eagly, 1989 ; Eagly & Chaiken, 1993 ). As cognitive misers, individuals are expected to base decisions on heuristics if they can be sufficiently confident in the accuracy of those decisions. If sufficient confidence cannot be reached using simple decision rules, individuals are expected to then also engage in the more effortful systematic processing. Although the HSM's systematic processing and the ELM's central processing are essentially the same, heuristic and peripheral processing differ in that the former is conceptualized as only cognitive and rational, whereas the latter is believed to encompass any cognitive or affective processes other than close message scrutiny. Research testing the unique aspects of the HSM has offered some evidence consistent with the model's propositions, particularly that of concurrent processing and the attenuation of heuristic effects by systematic processing (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993 ). Further, the model has been elaborated by identifying multiple motives for message processing (i.e., accuracy, defensive, and impression motivations). However, research has not directly targeted the sufficiency threshold construct, thus limiting insights into the factors that might move the threshold higher or lower, which would have implications for the information needs of the audience.

Given that media effects scholars have generally adopted the view of audiences as active consumers of messages rather than mere passive information recipients, it is understandable why cognitive response models have been readily embraced by media effects scholars. Indeed, the ELM and HSM have been applied in numerous traditional advertising contexts, including those related to health (e.g., Wilson, 2007 ; Smith, Lindsey, Kopfman, Yoo, & Morrison, 2008 ), politics (e.g., Holbert, Garrett, & Gleason, 2010 ), and of course commercial products (e.g., Whittler & Spira, 2002 ). Generally speaking, such research tends to apply these theories to understand how various features of the audience (e.g., motivation) and features of the messages (e.g., arguments and cues) interact to lead to changes in attitudes, behavioral intentions, and behaviors.

There is a wealth of evidence supporting the tenets of cognitive-response models in advertising contexts. However, perhaps because they were developed with a focus on psychological mechanisms rather than message design, they are not particularly responsive to the complexities with which modern media messages may be presented. For example, whereas the majority of ELM-based studies are based on text-only messages, an overwhelming proportion of mediated persuasive messages contain visuals. According to Petty and Cacioppo's ( 1986 ) arguments, the persuasive impact of visuals would depend on whether the receiver is motivated and/or able to process the message. If motivated and able, the visuals will be taken as arguments. Otherwise, they will be used as cues and have ephemeral effects on attitudes. However, given visuals (unlike text) can be processed quickly with minimal cognitive effort, one might have low motivation and ability and yet still be greatly impacted by a particularly gripping image that can be processed nearly automatically and, in turn, result in long-lasting attitude change. Thus, the ELM, in its current form, seems somewhat insensitive to more modern persuasive contexts.

As the design of persuasive media messages evolves, some research will certainly continue to work within the typical framework of dual-processing cognitive response models, examining, for example, how innovative message features, like interactive social agents (e.g., Skalski & Tamborini, 2007 ) and online reviews (Lin, Lee, & Horng, 2011 ), influence processing motivation or serve as peripheral cues. However, given the ELM and HSM were developed largely in the context of more text-based, expository messages—a less typical form of media presentation in recent years—some fundamental assumptions about the nature of message processing as captured by these theories, may be challenged by newer media formats. For example, Cho ( 1999 ) articulated a modified elaboration likelihood model to address the processing of Web advertising, arguing for the roles of both voluntary and involuntary ad exposure as well as the mediating effects of repeated exposure, attitude toward the site, and attitude toward Web advertising, beyond the roles of processing motivation and ability as articulated by the ELM. San Jose-Cabezudo, Gutierrez-Arranz, and Gutierrez-Cillan ( 2009 ) also argue that how Web pages are presented influences the nature of the information processing that ensues.

In sum, cognitive response models have provided a very useful framework for understanding how media messages may lead to persuasive effects, and will surely continue to guide examination of unique media features in the coming years. However, newer media forms may bring to light limits of these theories developed in an era of less complex message design and thus ideally generate theoretical innovations sensitive to these technological changes.

Expectancy Value Theories

A second class of persuasion theories—expectancy value theories—also focuses on cognition, but these theories assume audiences are rational decision makers who weigh the pros and cons of their options. More specifically, they assume people have expectancies regarding whether an object has a certain attribute, and they ascribe a particular value to that attribute. In combining these assessments, one's attitude is formed. Indeed, it was the endeavor to understand the conditions under which stable attitude–behavior relationships could be found that resulted in the development of the most well-known expectancy-value theory—the theory of reasoned action (TRA) (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975 ), one of the more influential theories of social influence in the last 50 years.

According to the TRA, the best predictor of volitional behavior is behavioral intention (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975 ). Behavioral intentions, in turn, are based on two types of cognitive antecedents: (1) attitudes toward performing a particular behavior, and (2) the subjective norm surrounding that behavior. Attitudes are comprised of groups of salient beliefs regarding behavioral outcomes and evaluations of those outcomes. Comparably, the subjective norm is comprised of perceptions of important others’ attitudes regarding one performing the behavior and motivation to comply with their opinions. Under this conceptualization, other variables, like demographics, personality traits, and related attitudes, affect behavior only insofar as they affect the individual's beliefs, evaluations, or motivations to comply. A meta-analysis of TRA-based research supports the model's propositions that attitudes and subjective norms can accurately predict behavioral intentions and, in turn, behaviors (Sheppard, Hartwick, & Warshaw, 1988 ). In addition, a meta-analysis of 138 attitude–behavior correlations further supports the TRA's position that attitudes can have strong associations with behaviors across a range of topics (Kim & Hunter, 1993 ).

Despite the wealth of evidence supporting the TRA, its critics argue that its utility and predictive ability are limited by its intended applicability to: (1) volitional behaviors only, (2) stable attitudes and behavioral intentions, and (3) corresponding attitude and behavior measures in terms of target, context, time, and action (see Eagly & Chaiken, 1993 for a critical review). In fact, several individual and situational barriers have been identified as having a significant impact on the translation of attitudes and/or intentions into behaviors, including time, money, the cooperation of other people, and personal self-efficacy (Triandis, 1977 ; Ajzen, 1985 ; Ajzen & Madden, 1986 ; Madden, Ellen, & Ajzen, 1992 ). Indeed, the theory of planned behavior was developed to help address these limitations (Ajzen, 1985 ), and recently Fishbein and Ajzen ( 2010 ) have elaborated on the critical elements of the reasoned action perspective, including the origins of beliefs, the role of injunctive versus descriptive norms, and the determinants of perceived behavioral control. Still, within its self-identified boundaries, TRA-based research has generated evidence to demonstrate that under the appropriate circumstances, attitudes can reliably predict behavioral intentions and behaviors.

Applied to media-based persuasion, the TRA is most helpful in suggesting what message content, rather than message design features, might best produce persuasive effects. To the extent a behavior is more heavily influenced by attitudes, one might attempt to change already-held outcome–belief expectancies or the valuations ascribed to those outcomes. Or one might look to add new belief clusters to the attitude equation. If the subjective norm is more dominant in predicting behavioral intentions and behaviors, then producing messages that speak to perceptions of what others think, motivation to comply, or adding new important others to the equation may be effective. Moreover, one might also attempt to alter the weighting of the attitude relative to the subjective norm to affect shifts in behavioral intentions and behaviors. Although this framework is extremely useful in guiding conceptually what one might hope to achieve with a persuasive message, the TRA is silent on how one might actually implement those ideas in message design. Further, the TRA is very limited in its consideration of factors beyond “rational” beliefs. Most notably, the role of emotion is not incorporated into the model in any direct or meaningful way. Given emotion (as described in a later section) is a primary motivational force underlying behavior, this is a very notable limitation of the TRA.

As media message platforms shift such that persuasive messages may be easily avoided (e.g., fast forwarding through commercials or blocking pop-up ads on web sites) or alternatively hard to avoid (e.g., embedded in web sites of interest), it has become increasingly important to take into consideration how belief-based information is presented to capture attention. Yet, it is this very presentation that may shift audiences away from more rational and deliberative decision making (see discussions of emotion and framing that follow). Although Fishbein and Ajzen ( 2010 ) would likely argue that such message features (e.g., emotional presentations) act merely as background variables influencing behaviors only indirectly through the beliefs formed, the action tendencies associated with emotions generated from media presentations may actually serve to intensify the likelihood of action without full mediation through beliefs. Thus, important directions for future research will be to consider not just how various message features may influence the construction of attitudes and subjective norms via information salience, but also how the process of influence through to behavior is influenced by the psychological state the audience may be in because of those attention-getting contextual features.

Emotion and Persuasion

A third dominant framework for media-based persuasion research focuses on affective states. Most of the research here has centered around fear arousal and its effects on both message processing and persuasion-related outcomes (e.g., attitudes, behavioral intentions, and behaviors), although the persuasive influence of other emotional states is receiving increasing attention.

Fear Appeal Research

The fear appeal literature has cycled through several theoretical perspectives over the past 50 years (see Nabi, 2007 for more detailed discussion), including: (1) the drive model, which conceptualized fear as resembling a drive state, motivating people to adopt recommendations expected to alleviate the unpleasant state (e.g., Hovland, Janis, & Kelley, 1953 ); (2) the parallel processing model (PPM) (Leventhal, 1970 ), which separated the motivational from the cognitive aspects involved in processing fear appeals, suggesting that those who respond to fear appeals by focusing on the threat (cognition) would engage in adaptive responses, whereas those responding with fear (emotion) would engage in maladaptive responses; (3) the expectancy value–based protection motivation theory (Rogers, 1975 , 1983 ), which ultimately focused on four categories of thought generated in response to fear appeals—judgments of threat severity, threat susceptibility, and response and self-efficacy—and how they might combine to predict message acceptance; and (4) the extended parallel process model (EPPM) (Witte, 1992 ), which integrated the PPM and PMT, predicting that if perceived efficacy outweighs perceived threat, danger control and adaptive change will ensue. If, however, perceived threat outweighs perceived efficacy, then fear control and maladaptive behaviors are expected.

Although meta-analyses of fear research essentially suggest that the cognitions identified in the PMT, and later the EPPM, are important to fear appeal effectiveness, no model of fear appeals has been endorsed as accurately capturing the process of fear's effects on decision making and action (see Mongeau, 1998 ; Witte & Allen, 2000 ). Regardless, evidence does support a positive linear relationship between fear and attitude, behavioral intention, and behavior change. Thus, to the extent message features evoke perceptions of susceptibility and severity, as well as response and self-efficacy, fear may moderate persuasive outcome, although there are still important questions about the interrelationships among these constructs that remain unanswered. Further, questions about whether severity and susceptibility information should always be included in fear appeals or whether “implicit” fear appeals might be more effective have also been raised (Nabi, Roskos-Ewoldsen, & Dillman Carpentier, 2007 ). Thus, there is still much work to be done in linking the theory of fear appeals to appropriate message design.

Beyond Fear Appeals