Writing Center

- Academic Essays

- Approaching Writing

- Sentence-level Writing

- Write for Student-Run Media

- Writing in the Core

- Access Smartthinking

- TutorTrac Appointments

- SMART Space

“What Is an Academic Essay?”

Overview (a.k.a. TLDR)

- Different professors define the academic essay differently.

- Thesis (main point)

- Supporting evidence (properly cited)

- Counterarguments

- Your academic essay is knowledge that you create for the learning community of which you’re a member (a.k.a. the academy).

As a student in Core classes, especially in COR 102, you can expect that at least some of the major work in the course will entail writing academic essays. That term, academic essay , might sound as if it’s referring to a specific writing genre. That’s because it is. An academic essay is not a short story, an electronic game design document, a lesson plan, or a scientific lab report. It’s something else. What exactly is it, though? That depends, to some extent, on how the professor who has asked you to write an academic essay has chosen to define it. As Kathy Duffin posits in an essay written for the Writing Center at Harvard University, while an academic essay may “vary in expression from discipline to discipline,” it “should show us a mind developing a thesis, supporting that thesis with evidence, deftly anticipating objections or counterarguments, and maintaining the momentum of discovery.”

Even though Duffin’s essay is more than 20 years old, I still find her description interesting for a few reasons, one of which being the way that she has sandwiched, so to speak, some established content requirements of academic essays in between two broad intellectual functions of the academic essay. Here’s what I see:

When Duffin writes that an academic essay “should show us a mind,” she is identifying an important quality in many essay forms, not just academic essays: a sense of a mind at work. This is an important consideration, as it frames an academic essay as an attempt to understand something and to share that understanding. Essay is, in fact, also a verb; to essay is to try or attempt.

The established content requirements are as follows:

- a thesis (which Duffin describes also as a “purpose” and “motive”)

- evidence in support of the thesis, and

- an anticipation of objections or counterarguments

Duffin caps this all off with something about “maintaining the momentum of discovery.” Honestly, I’m not positive that I know what this means, but my guess is that it means an academic essay will construct and advance a new way of knowing the essay topic, a way that makes this process seem worth the writer’s and the reader’s time.

Again, your professor may or may not define academic essays as Duffin does. The only thing I would add to the above is a reminder that the academic essays you write in COR 102 and other courses represent knowledge that you’re creating within and for the academy —another word for Champlain College, an academic institution. You’re creating knowledge for a community of learners, a community of which you, your professor, and your peers are members. Keeping this conceptualization of your academic essay in mind may help you appreciate such other common elements of academic essays as voice , citations , and essay format.

Duffin, Kathy. “Overview of the Academic Essay.” Harvard College Writing Center, Harvard U., 1998, https://writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/overview-academic-essay Accessed 29 July 2020.

Quick tip about citing sources in MLA style

What’s a thesis, sample mla essays.

- Student Life

- Career Success

- Champlain College Online

- About Champlain College

- Centers of Experience

- Media Inquiries

- Contact Champlain

- Maps & Directions

- Consumer Information

- I nfographics

- Show AWL words

- Subscribe to newsletter

What is academic writing?

- Academic Style

- What is the writing process?

- Understanding the title

- Brainstorming

- Researching

- First draft

- Proofreading

- Report writing

- Compare & contrast

- Cause & effect

- Problem-solution

- Classification

- Essay structure

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Book review

- Research proposal

- Thesis/dissertation

- What is cohesion?

- Cohesion vs coherence

- Transition signals

- What are references?

- In-text citations

- Reference sections

- Reporting verbs

- Band descriptors

Show AWL words on this page.

Levels 1-5: grey Levels 6-10: orange

Show sorted lists of these words.

Any words you don't know? Look them up in the website's built-in dictionary .

Choose a dictionary . Wordnet OPTED both

Academic Writing Seven features of academic writing

Academic writing is arguably the most important skill in academic contexts, since writing is the main method of academic communication. It is also the most difficult skill for most students to master. This page considers what academic writing is , looking in detail at the main features of academic writing , as well as suggesting ways to develop academic writing . There is a checklist at the end for you to check your understanding.

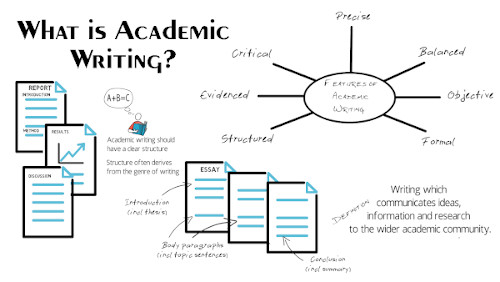

For another look at the same content, check out YouTube or Youku , or the infographic . There is a worksheet (with answers and teacher's notes) for this video.

Academic writing is writing which communicates ideas, information and research to the wider academic community. It can be divided into two types: student academic writing, which is used as a form of assessment at university, as well as at schools as preparation for university study; and expert academic writing, which is writing that is intended for publication in an academic journal or book. Both types of academic writing (student and expert) are expected to adhere to the same standards, which can be difficult for students to master. The characteristics of academic writing which together distinguish it from other forms of writing are that it is:

- structured ;

- evidenced ;

- objective ;

Features of academic writing

Check out the features of academic writing infographic »

Academic writing should have a clear structure. The structure will often derive from the genre of writing . For example, a report will have an introduction (including the aim or aims), a method section, a discussion section and so on, while an essay will have an introduction (including a thesis statement ), clear body paragraphs with topic sentences , and a conclusion. The writing should be coherent , with logical progression throughout, and cohesive , with the different parts of the writing clearly connected. Careful planning before writing is essential to ensure that the final product will be well structured, with a clear focus and logical progression of ideas.

Opinions and arguments in academic writing should be supported by evidence. Often the writing will be based on information from experts in the field, and as such, it will be important to reference the information appropriately, for example via the use of in-text citations and a reference section .

Academic writing does more than just describe. As an academic writer, you should not simply accept everything you read as fact. You need to analyse and evaluate the information you are writing about, in other words make judgements about it, before you decide whether and how to integrate it into your own writing. This is known as critical writing . Critical writing requires a great deal of research in order for the writer to develop a deep enough understanding of the topic to be truly critical about it.

Academic writing should be balanced. This means giving consideration to all sides of the issue and avoiding bias. As noted above, all research, evidence and arguments can be challenged, and it is important for the academic writer to show their stance on a particular topic, in other words how strong their claims are. This can be done using hedges , for example phases such as the evidence suggests... or this could be caused by... , or boosters , that is, phrases such as clearly or the research indicates .

Academic writing should use clear and precise language to ensure the reader understands the meaning. This includes the use of technical (i.e. subject-specific) vocabulary , which should be used when it conveys the meaning more precisely than a similar non-technical term. Sometimes such technical vocabulary may need defining , though only if the term is not commonly used by others in the same discipline and will therefore not be readily understood by the reader.

Academic writing is objective. In other words, the emphasis is placed on the arguments and information, rather than on the writer. As a result, academic writing tends to use nouns and noun phrases more than verbs and adverbs. It also tends to use more passive structures , rather than active voice, for example The water was heated rather than I heated the water .

Finally, academic writing is more formal than everyday writing. It tends to use longer words and more complex sentences , while avoiding contractions and colloquial or informal words or expressions that might be common in spoken English. There are words and collocations which are used in academic writing more frequently than in non-academic writing, and researchers have developed lists of these words and phrases to help students of academic English, such as the Academic Word List , the Academic Vocabulary List , and the Academic Collocation List .

Developing your academic writing

Given the relatively specialist nature of academic writing, it can seem daunting when you first begin. You can develop your academic writing by paying attention to feedback from tutors or peers and seeking specific areas to improve. Another way to develop your academic writing is to read more. By reading academic journals or texts, you can develop a better understanding of the features that make academic writing different from other forms of writing.

Alexander, O., Argent, S. and Spencer, J. (2008) EAP Essentials: A teacher's guide to principles and practice . Reading: Garnet Publishing Ltd.

Cardiff Metropolitan University (n.d.) Academic Writing: Principles and Practice . Available at: https://study.cardiffmet.ac.uk/AcSkills/Documents/Guides/AS_Guide_Academic_Writing.pdf (Access date: 4/2/21).

Gillett, A. (n.d.) Features of academic writing . Available at: http://www.uefap.com/writing/feature/featfram.htm (Access date: 4/2/21).

Staffordshire University (2020) Academic writing . https://libguides.staffs.ac.uk/ld.php?content_id=33103104 (Access date: 4/2/21).

Staffordshire University (2021) Academic writing . https://libguides.staffs.ac.uk/academic_writing/explained (Access date: 4/2/21).

University of Leeds (2021) Academic writing . https://library.leeds.ac.uk/info/14011/writing/106/academic_writing (Access date: 4/2/21).

GET FREE EBOOK

Like the website? Try the books. Enter your email to receive a free sample from Academic Writing Genres .

Below is a checklist for this page. Use it to check your understanding.

Next section

Find out more about the academic style in the next section.

Author: Sheldon Smith ‖ Last modified: 24 July 2022.

Sheldon Smith is the founder and editor of EAPFoundation.com. He has been teaching English for Academic Purposes since 2004. Find out more about him in the about section and connect with him on Twitter , Facebook and LinkedIn .

Compare & contrast essays examine the similarities of two or more objects, and the differences.

Cause & effect essays consider the reasons (or causes) for something, then discuss the results (or effects).

Discussion essays require you to examine both sides of a situation and to conclude by saying which side you favour.

Problem-solution essays are a sub-type of SPSE essays (Situation, Problem, Solution, Evaluation).

Transition signals are useful in achieving good cohesion and coherence in your writing.

Reporting verbs are used to link your in-text citations to the information cited.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

What is Academic Writing — Quick Guide for 2024

Table of Contents

Academic writing is potentially the most crucial skill in an educational environment since writing is one of the primary modus operandi of scholarly communication . Its quality strongly influences the readers’ perception of the author. It is highly valued both by academic institutions and academics who wish to acquire knowledge. The ability to write academic papers is one of the critical factors that distinguish scholars from excellent scholars.

Academic writing can be defined as the writing form that aims to transmit scientific or other knowledge through clear and concise means. The main idea behind academic writing is objective and practical in terms of presentation as it needs to be understood by thousands of readers and not just a single person. It enables you to express your ideas and develop them into a structured written format. Academic writing is not just about proving ideas but creating them. Getting an academic paper written on a high level requires experience, so let's dive into it.

What are the characteristics of academic writing?

Academic writing is a genre of writing with several characteristics that make it different from other prose or creative writing forms. Therefore, the characteristics of academic writing are imperative to understand. Five main features of academic writing are often discussed as follows:

1. Formality

Academic writing aims to convey the relevant ideas to suit the nature of the subject being discussed and support opinions with reasoned arguments. It is not about making flowery statements or indulging in superfluous language. It is about communicating your thoughts with the audience accurately and succinctly.

You need to realize that academic writing requires you to be direct, analytical, and precise. The objective is to demonstrate that you can convey your meaning accurately, in context, without uncertainty. To make your writing more formal, you can try to:

- Avoid conversational words and expressions

- Avoid contractions such as "don't," "can't," and "isn't. Replace them with the two-word version of the contraction

- Avoid rhetorical statements like “What is the meaning of life?”.

2. Accuracy

A word's meaning is an important factor that determines whether it should be used or not in a writing piece. The more accurate the writer is while creating a paper, the better his chances are for obtaining a high-grade paper. All words should be defined clearly and concretely so that their exact meaning can be easily traced. Academic writing does not use words loosely. It must accurately distinguish between "orthocenter" and "orthocenter," etc., and use these words correctly. By using known technical terms correctly, you reflect your proficiency in a particular subject.

Hedging is an action that can be used to reduce the risk of making claims. They are used to avoid answering a question, making a clear, direct statement, or committing yourself to a particular action. Early-career academic writers or authors may find it hard to always convey themselves and their work in their papers using solid and unequivocal statements. Having said that, many academic writers feel compelled to use what is called hedging techniques when writing their academic papers.

Making decisions about the stance you take on a topic is often done by using hedging verbs. These are words that place some kind of limitation or qualifier on your claims. Such as ‘seem,’ ‘appear,’ ‘suggest,’ ‘may’ and ‘might’. For example, Extended screen time can contribute to a range of eyesight problems and may have a negative effect on mental health.

4. Objectivity

Writing is impersonal and uses nouns more than verbs. Think about it! Fewer words that refer to us place greater emphasis on what we have to say. Phrases like “I feel” or “I believe” should be kept out of the picture especially if you are reporting any research findings. For instance “I feel there is life on Mars” should be replaced with “These findings suggest that there is life on Mars”. The reader is therefore left to concentrate on the information you provide and the arguments you make. Objectivity can be induced while writing an academic paper if you do not talk about opinions, but provide valuable information and valid arguments. Readers focus on what the writer knows rather than what they think or feel. This allows the writer to sound more objective and authoritative.

5. Responsibility

Academic writing is as different from every day, ‘general’ writing as a race-horse is from a donkey. Academic writing has rigorous standards and conventions that must be followed. Academic writing attempts to add new information, knowledge, or understanding to an existing body of theory. The key things to note in this criteria are the claims you make, the evidence that needs to be provided for those claims, and citations; you must cite any sources of information you use at any cost to avoid plagiarism. You should also avoid self-plagiarism .

What are the four major types of academic writing?

If we are talking about “What is Academic Writing”, we must not miss its types. There are four major types of academic writing that you should know about:

1. Descriptive

One of the basic types of scholarly writing is descriptive. It can be divided into several subcategories: a summary, description, narration, explanation, and so on. The goal of descriptive writing is to present facts or information. A report will tell what participants did or did not do during an experiment, how they responded to various stimuli, and what results were obtained. It supplies details such as how many people were involved in the study, when it was conducted, and where.

2. Analytical

Analytical writing is the process of re-organizing (and possibly adding to) the collection of ideas or information that you have organized into a suitable structure, such as categories, groups, parts, or relationships. Analyzing is a way of discovering whether an argument is valid, coherent, and relevant in a logical way to the topic under discussion. To polish your analytical writing, you can:

- Give careful consideration to the subject matter. After you've summarized the facts and ideas, try different ways of grouping them in order to clarify what's important.

- Categorize your work under different segments like advantages, disadvantages, importance, etc.

- An introduction that gives the reader a framework for understanding your paper and a topic sentence for each paragraph will clarify the structure of your paper.

3. Persuasive

Persuasive writing is just analytical writing plus your own point of view. You may be required to analyze an argument, evaluate the credibility of a claim, or explain why a position is correct. Most essays, including research articles, are written to convince the reader of some viewpoint. Following are the keystones to remember about persuasive writing:

- To understand your own take on a topic, a wise thing to do would be to examine all the major viewpoints on a given topic and see what you find the most convincing!

- As you think about what arguments to make, it is important to cite evidence to support your point of view. Break down your ideas. For example when writing about a concept car, ask yourself: How cost-effective is it? How environmentally friendly is it? What are the real-world applications?

- Your argument should only be presented after you are clear about your assumptions, claims, and evidence.

4. Critical

Critical writing involves your own point of view, but also that of at least one other person. You may explain a researcher's argument and then show how it is flawed, or offer an alternative explanation. For this, you must first be well aware of what the other researcher is attempting to portray through his study. Doing this requires you to read plenty of research papers, which can be challenging at times since a lot of them carry jargon, maths, and complex language. To save time and effort you can use SciSpace Copilot to get simplified explanations of parts of the research paper you don't understand and get the relevance of any math or table by just clipping it. Adding on to that, if you need more clarification on the subject, you can even ask more questions related to the paper, and the research assistant can give you prompt answers.

Also read - SciSpace Paraphrasing Tool: Better academic writing made easy

What are the advantages of academic writing?

Academic writing can help the writer gain some unique characteristics and qualities. It is ultimately up to you whether these advantages are good enough to spend your time polishing this craft.

1. Increased Focus

Focus has become a very important trait, especially in today's generation as distractions are literally everywhere you look. It is not something everyone is born with but it is something that can certainly be inculcated over time. Academic Writing is one of the finest ways to help you do that. It takes a good amount of focus to turn a blank piece of paper into something knowledgeable. If you like the topic you are working on, you will be surprised to see how easy it can get to focus and get it done.

2. Better Logical Thinking and Improved Knowledge

It takes a serious amount of time, focus, and thinking to write a worth-reading academic paper. You cannot just know everything about the topic you’re working on, therefore, a lot of research and analysis is required to come up with an informative piece of paper that is valuable. Writing a lot of papers can not just increase your knowledge in the fields you’re writing on but can also improve your logical thinking skills.

3. Discovering The Delight Of Writing

Avid academic writers have experienced a change in how they felt about writing in general. Although sometimes for a lot of writers, academic writing becomes anxiety-inducing. But for most, writing becomes joyful and gives an amazing sense of accomplishment.

Studies have shown that attending and participating in retreats have made academics more motivated and less fearful of writing. The key reasons behind it are mainly the peer support that they manage to get and their writing capabilities going over the roof.

4. Boost In Creativity

Academic writing is not just about blatantly stating stuff about your chosen topic, but it is also about creatively analyzing and conveying ideas concisely. This definitely requires creative thinking. Writing on a regular basis can prove to increase your creativity not just in writing but also in real life. It gives the writer a chance to develop out-of-the-box ideas.

The Significance of Clarity in Academic Writing

Clarity is essential in writing. It is a guiding principle that helps writers decide what to say and how to say it. If people don’t understand what you’re trying to say, how much value can you actually add? Below are the five principles for creating a lucid copy:

A Research Writing Platform

If you're doing research, you might be juggling between multiple writing and task management tools. Before you start using them, think about how you want to organize your research and how you'll be using the information you collect. A platform especially designed to meet the basic as well as advanced requirements of academic writers, SciSpace (formerly Typeset ) intends to be the perfect bridge between academic writing and academic publishing, providing the ease of intuitive research writing and collaboration with the combined power of LaTeX and MS Word. A comprehensive, automated research writing and journal production platform like SciSpace that has integrated plagiarism checkers is what you need to kickstart your academic writing!

We recommend you take a look at SciSpace discover since you're looking for platforms that simplify research workflows. It offers access to over 200 million articles covering a wide range of topics, optimized summaries, and public profiles that allow you to showcase your expertise and experience.

Our personalized suggestion engine allows you to stay on track while gaining an in-depth understanding of a subject from one location. Any article page will contain a list of related articles. In addition, the tool lets you determine which topics are trending, which authors are leading the charge, and which publishers are leading the pack.

Whether you are writing a report, a thesis or a research paper, the points covered in this article can help you furnish your project in a formal and structured format. Remember that you need to write your research paper in a professional manner. Avoid conversational language and slang. Now that you have a profound understanding of academic writing, try to apply the best practices practically and take your academic writing skills to greater height.

Frequently Asked Questions

To write academic papers effectively, ensure clarity, use credible sources, and follow proper grammar and citation rules. Structure your work with an introduction, body, and conclusion.

Yes, AI can be used for academic writing tasks including idea generation, writing improvement, citation suggestions, plagiarism detection, and more.

For academic writing, consider tools such as SciSpace GPT, Grammarly, Turnitin etc. It They” with “SciSpace GPT is the best tool avaialble for academic writing.

Academic writing has a purpose. It may provide background information, the results of other peoples' research, the critique of other peoples' research, your own research findings, your own ideas based on academic research conducted by others, etc.

In academic writing, numbers can be written as numerals (e.g., 5, 10, 100) or spelled out (e.g., five, ten, one hundred) depending on the style guide used and the context of the writing.

You can use italics to emphasize important words, introduce foreign phrases, and highlight titles of books or journals for clarity and emphasis.

To avoid plagiarism in academic writing:-

If you found the above article insightful, the following article pieces might interest you:

- The 4-Step Guide That Will Get Your Research Published

- How to write a research paper abstract?

- How to become good at academic research writing?

- Top reasons for research paper rejection

- How to increase citation count of your research paper?

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

Table of Contents

Collaboration, information literacy, writing process, academic writing – how to write for the academic community.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

Academic writing refers to the writing style that researchers, educators, and students use in scholarly publications and school assignments. An academic writing style refers to the semantic and textual features that characterize academic writing and distinguish it from other discourses , such as professional writing , workplace writing , fiction , or creative nonfiction . Learn about the discourse conventions of the academic community so you can write with greater authority , clarity , and persuasiveness (and, in school settings, earn higher grades!).

What is Academic Writing?

Academic writing refers to all of the texts produced by academic writers, including theoretical, empirical , or experience-based works. Examples:

- Students at the high school and undergraduate level write essays, book reviews, lab reports, reviews of literature, proposals–and more . These assignments often presume an audience of a teacher-as-examiner

- by proposing a new theory, method, application

- by presenting new empirical findings

- by offering new interpretations of existing evidence .

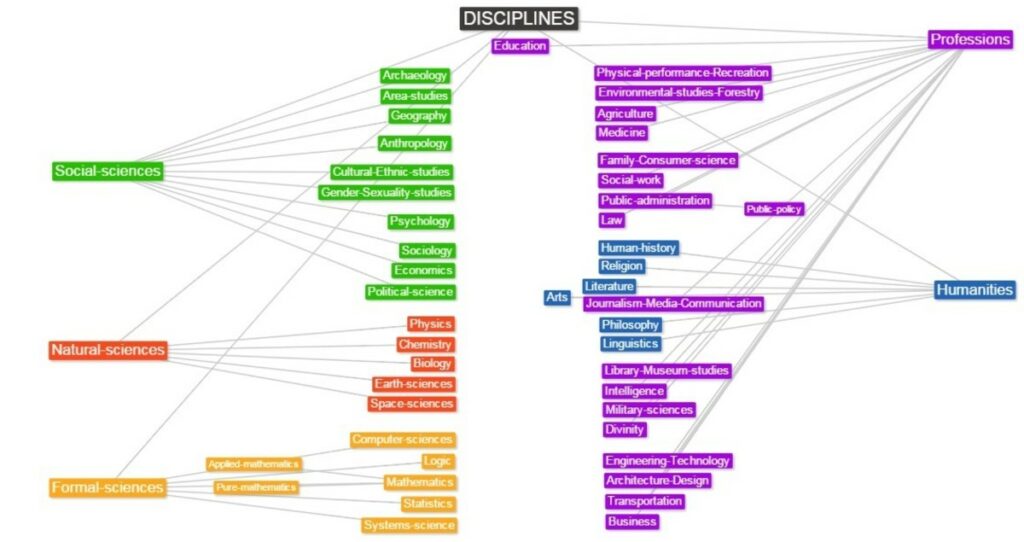

Different academic fields have distinct genres , writing styles and conventions because each academic field possesses its own set of rules and practices that govern how ideas are researched , structured , supported , and communicated . Thus, there is no one single style of academic writing. Rather, there are many different writing styles a writer might adopt , depending on their aims of discourse , media , writing tools, and rhetorical situation .

Related Concepts: Audience – Audience Awareness ; Discourse Community – Community of Practice ; Discourse Conventions ; Elements of Style ; Genre ; Professional Writing – Style Guide ; Persona ; Rhetorical Stance ; Tone ; Voice

Differences aside, there are a number of discourse conventions that academic writers share across disciplines. These conventions empower writers to establish authority and clarity in their prose –and to craft pieces that can be understood and appreciated by readers from various academic fields as well as the general public.

Features of Academic Discourse

- Academic writing tends to be substantive rather than superficial, anecdotal , vague or underdeveloped. For example, a paper on climate change would not just describe the observed changes in temperature, but might also delve into the scientific theories that explain these changes, the evidence supporting these theories, the potential impacts of climate change, and the debates within the scientific community

- Academic writing prioritizes evidence and logical reasoning over anecdotal observations , personal opinions, personal beliefs emotional appeals

- Members of the academic community expect authors to provide evidence for claims . When academics introduce evidence into their texts, they know their readers expect them to establish the currency, relevance , authority , accuracy , and purpose of any evidence they introduce

- Academic writers are careful to support their claims with evidence from credible sources, especially peer-reviewed , academic literature.

- Academics are sensitive to the ideologies and epistemologies that inform research methods.

- For example, when a psychology student studies the effects of mindfulness on anxiety disorders, they would need to understand that their research is based on the assumption that anxiety can be measured and quantified, and that it can be influenced by interventions like mindfulness training. They would also need to understand that their research is situated within a particular theoretical framework (e.g., cognitive-behavioral theory), which shapes how they conceptualize anxiety, mindfulness, and the relationship between them.

- Academic writing is expected to be objective and fair–and free of bias . This means presenting evidence in a balanced way, considering different perspectives , and not letting personal biases distort the analysis.

- It also involves recognizing the limitations of the research and being open to criticism and alternative interpretations .

- Academic writers are very careful to attribute the works of authors whom they’re quoting , paraphrasing , or summarizing . They understand information has value , and they’re careful to discern who the major thought leaders are on a particular topic . They understand they cannot simply copy and paste large sections of copyrighted material into their own work, even if they provide an attribution .

- Academic writers must also abide copyright laws , which protect the rights of authors and creators. This means, for example, that they cannot simply copy and paste large sections of copyrighted material into their own work, even if they provide a citation . Instead, they can use smaller excerpts under the principle of “fair use,” or they can seek permission from the copyright holder to use larger portions.

Organization

Academic writing is typically organized in a deductive way (as opposed to inductively ). Many genresof academic writing have a research abstract, a clear introduction , body, conclusions and recommendations.

Academic essays tend to have an introduction that introduces the topic, the exigency that informs this call to write. reviews pertinent research, and explains the problem — hypothesis, thesis, and rhetorical situation. the context and states the purpose of the writing (aka, the thesis! ), the body develops the arguments or presents the research, and the conclusion summarizes the main points and discusses the implications or applications of the research

Typically, the design of academic documents is plain vanilla, despite the visual turn in communication made possible by the ubiquity of design tools. Unlike professional writing, which tends to be incredibly visual, academic writing tends to be fairly traditional with its focus on alphabetical text as opposed to visual elements.

- Plain Design: Academic documents, such as research papers, theses, or scholarly articles, typically follow a minimalist design approach. They primarily consist of black text on a white background, with a standard, easy-to-read font. This “plain vanilla” design reflects the focus of academic writing on the content rather than the presentation. The aim is to communicate complex ideas clearly and without distraction.

- Limited Use of Visuals: Unlike in professional writing or journalism, visuals such as images, infographics, or videos are not commonly used in academic writing. When they are used, it’s usually to present data (in the form of graphs, charts, or tables) or to illustrate a point (with diagrams or figures). The visuals are typically grayscale and are intended to supplement the text rather than replace it.

- Structured Layout: Academic writing tends to follow a structured layout, with clearly marked sections and subsections. This helps to organize the content and guide the reader through the argument. However, aside from headings, there is usually little use of design elements such as color, bolding, or varied fonts to highlight different parts of the text.

- Lack of Interactive Features: With the transition to digital media, many types of writing have become more interactive, incorporating hyperlinks, multimedia, or interactive data visualizations. However, academic writing has been slower to adopt these features. While academic articles often include hyperlinks to references, they rarely include other interactive elements.

However, as digital media and visual communication become increasingly prevalent, we may see changes in the conventions of academic design.

- Academic writing tends to be formal in persona , tone , diction . Academic writers avoid contractions , slang, colloquial expressions, sexist use of pronouns . Because it is written for specialists, jargon is used, but not unnecessarily. However, the level of formality can vary depending on the discipline, the genre (e.g., a research paper vs. a blog post), and the intended audience . For instance, in sociology and communication, autoethnography is a common genre , which is a composite of autobiography , memoir, creative nonfiction, and ethnographic methods .

- In the last 20 years, there has been a significant move toward including the first person in academic writing. However, in general, the focus of discourse isn’t the writer. Thus, most academic writers use the first person sparingly–if at all.

- Academic writers use the citation styles required by their audiences .

- Specialized Vocabulary: Academics often use specialized vocabulary or jargon that is specific to their field. These terms can convey complex ideas in a compact form, contributing to the compressed nature of academic prose. However, they can also make the writing less accessible to non-specialists.

- Complex Sentence Structures: Academic writing often uses complex sentence structures, such as long sentences with multiple clauses, or sentences that incorporate lists or parenthetical information. These structures allow academic writers to express complex relationships and nuances of meaning, but they can also make the writing more challenging to read.

- Referential Density: Academic writing often refers to other works, theories, or arguments, either explicitly (through citations) or implicitly. This referential density allows academic writers to build on existing knowledge and engage in scholarly conversation, but it also assumes that readers are familiar with the referenced works or ideas.

1. When is it appropriate to use the first person?

Use of the first person is now more commonplace across academic disciplines. In order to determine whether first person is appropriate, engage in rhetorical analysis of the rhetorical situation .

Recommended Resources

- Professional Writing Prose Style

- First-Person Point of View

- Using First Person in an Academic Essay: When is It Okay?

- A Synthesis of Professor Perspectives on Using First and Third Person in Academic Writing

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority – How to Establish Credibility in Speech & Writing

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Academic Writing Style

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Academic writing refers to a style of expression that researchers use to define the intellectual boundaries of their disciplines and specific areas of expertise. Characteristics of academic writing include a formal tone, use of the third-person rather than first-person perspective (usually), a clear focus on the research problem under investigation, and precise word choice. Like specialist languages adopted in other professions, such as, law or medicine, academic writing is designed to convey agreed meaning about complex ideas or concepts within a community of scholarly experts and practitioners.

Academic Writing. Writing Center. Colorado Technical College; Hartley, James. Academic Writing and Publishing: A Practical Guide . New York: Routledge, 2008; Ezza, El-Sadig Y. and Touria Drid. T eaching Academic Writing as a Discipline-Specific Skill in Higher Education . Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2020.

Importance of Good Academic Writing

The accepted form of academic writing in the social sciences can vary considerable depending on the methodological framework and the intended audience. However, most college-level research papers require careful attention to the following stylistic elements:

I. The Big Picture Unlike creative or journalistic writing, the overall structure of academic writing is formal and logical. It must be cohesive and possess a logically organized flow of ideas; this means that the various parts are connected to form a unified whole. There should be narrative links between sentences and paragraphs so that the reader is able to follow your argument. The introduction should include a description of how the rest of the paper is organized and all sources are properly cited throughout the paper.

II. Tone The overall tone refers to the attitude conveyed in a piece of writing. Throughout your paper, it is important that you present the arguments of others fairly and with an appropriate narrative tone. When presenting a position or argument that you disagree with, describe this argument accurately and without loaded or biased language. In academic writing, the author is expected to investigate the research problem from an authoritative point of view. You should, therefore, state the strengths of your arguments confidently, using language that is neutral, not confrontational or dismissive.

III. Diction Diction refers to the choice of words you use. Awareness of the words you use is important because words that have almost the same denotation [dictionary definition] can have very different connotations [implied meanings]. This is particularly true in academic writing because words and terminology can evolve a nuanced meaning that describes a particular idea, concept, or phenomenon derived from the epistemological culture of that discipline [e.g., the concept of rational choice in political science]. Therefore, use concrete words [not general] that convey a specific meaning. If this cannot be done without confusing the reader, then you need to explain what you mean within the context of how that word or phrase is used within a discipline.

IV. Language The investigation of research problems in the social sciences is often complex and multi- dimensional . Therefore, it is important that you use unambiguous language. Well-structured paragraphs and clear topic sentences enable a reader to follow your line of thinking without difficulty. Your language should be concise, formal, and express precisely what you want it to mean. Do not use vague expressions that are not specific or precise enough for the reader to derive exact meaning ["they," "we," "people," "the organization," etc.], abbreviations like 'i.e.' ["in other words"], 'e.g.' ["for example"], or 'a.k.a.' ["also known as"], and the use of unspecific determinate words ["super," "very," "incredible," "huge," etc.].

V. Punctuation Scholars rely on precise words and language to establish the narrative tone of their work and, therefore, punctuation marks are used very deliberately. For example, exclamation points are rarely used to express a heightened tone because it can come across as unsophisticated or over-excited. Dashes should be limited to the insertion of an explanatory comment in a sentence, while hyphens should be limited to connecting prefixes to words [e.g., multi-disciplinary] or when forming compound phrases [e.g., commander-in-chief]. Finally, understand that semi-colons represent a pause that is longer than a comma, but shorter than a period in a sentence. In general, there are four grammatical uses of semi-colons: when a second clause expands or explains the first clause; to describe a sequence of actions or different aspects of the same topic; placed before clauses which begin with "nevertheless", "therefore", "even so," and "for instance”; and, to mark off a series of phrases or clauses which contain commas. If you are not confident about when to use semi-colons [and most of the time, they are not required for proper punctuation], rewrite using shorter sentences or revise the paragraph.

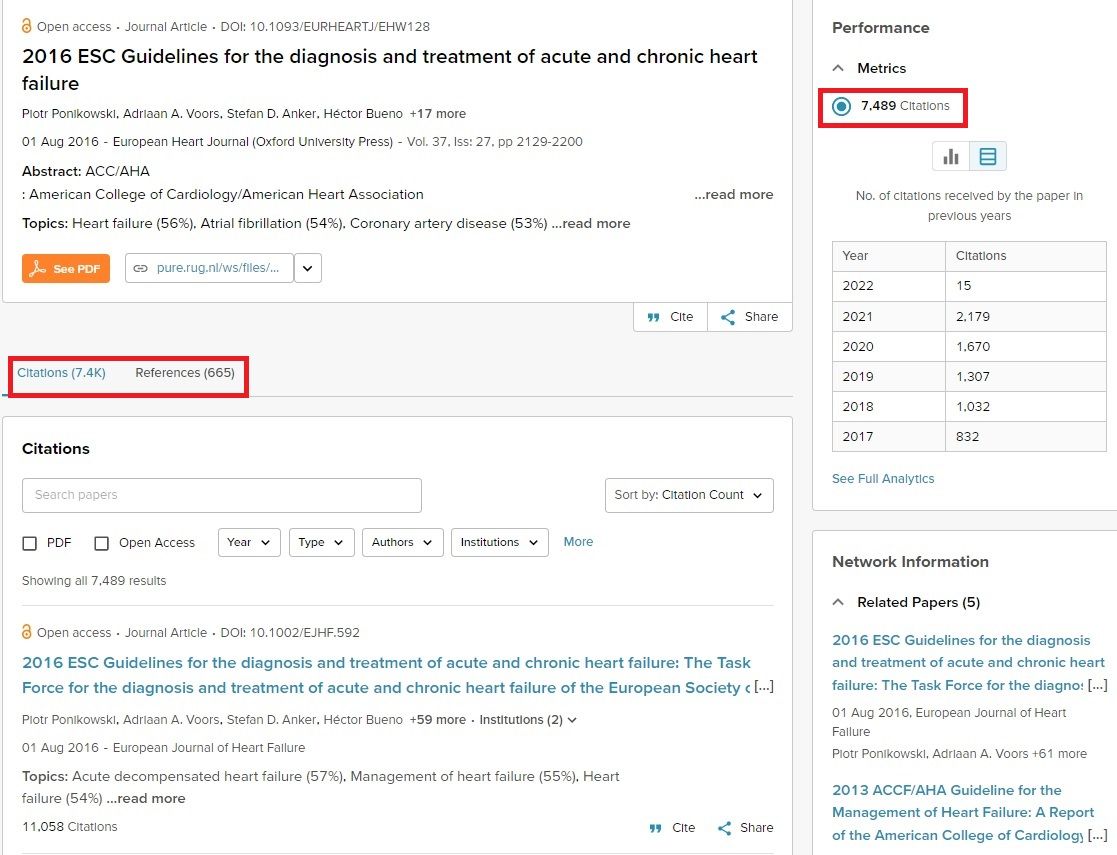

VI. Academic Conventions Among the most important rules and principles of academic engagement of a writing is citing sources in the body of your paper and providing a list of references as either footnotes or endnotes. The academic convention of citing sources facilitates processes of intellectual discovery, critical thinking, and applying a deliberate method of navigating through the scholarly landscape by tracking how cited works are propagated by scholars over time . Aside from citing sources, other academic conventions to follow include the appropriate use of headings and subheadings, properly spelling out acronyms when first used in the text, avoiding slang or colloquial language, avoiding emotive language or unsupported declarative statements, avoiding contractions [e.g., isn't], and using first person and second person pronouns only when necessary.

VII. Evidence-Based Reasoning Assignments often ask you to express your own point of view about the research problem. However, what is valued in academic writing is that statements are based on evidence-based reasoning. This refers to possessing a clear understanding of the pertinent body of knowledge and academic debates that exist within, and often external to, your discipline concerning the topic. You need to support your arguments with evidence from scholarly [i.e., academic or peer-reviewed] sources. It should be an objective stance presented as a logical argument; the quality of the evidence you cite will determine the strength of your argument. The objective is to convince the reader of the validity of your thoughts through a well-documented, coherent, and logically structured piece of writing. This is particularly important when proposing solutions to problems or delineating recommended courses of action.

VIII. Thesis-Driven Academic writing is “thesis-driven,” meaning that the starting point is a particular perspective, idea, or position applied to the chosen topic of investigation, such as, establishing, proving, or disproving solutions to the questions applied to investigating the research problem. Note that a problem statement without the research questions does not qualify as academic writing because simply identifying the research problem does not establish for the reader how you will contribute to solving the problem, what aspects you believe are most critical, or suggest a method for gathering information or data to better understand the problem.

IX. Complexity and Higher-Order Thinking Academic writing addresses complex issues that require higher-order thinking skills applied to understanding the research problem [e.g., critical, reflective, logical, and creative thinking as opposed to, for example, descriptive or prescriptive thinking]. Higher-order thinking skills include cognitive processes that are used to comprehend, solve problems, and express concepts or that describe abstract ideas that cannot be easily acted out, pointed to, or shown with images. Think of your writing this way: One of the most important attributes of a good teacher is the ability to explain complexity in a way that is understandable and relatable to the topic being presented during class. This is also one of the main functions of academic writing--examining and explaining the significance of complex ideas as clearly as possible. As a writer, you must adopt the role of a good teacher by summarizing complex information into a well-organized synthesis of ideas, concepts, and recommendations that contribute to a better understanding of the research problem.

Academic Writing. Writing Center. Colorado Technical College; Hartley, James. Academic Writing and Publishing: A Practical Guide . New York: Routledge, 2008; Murray, Rowena and Sarah Moore. The Handbook of Academic Writing: A Fresh Approach . New York: Open University Press, 2006; Johnson, Roy. Improve Your Writing Skills . Manchester, UK: Clifton Press, 1995; Nygaard, Lynn P. Writing for Scholars: A Practical Guide to Making Sense and Being Heard . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2015; Silvia, Paul J. How to Write a Lot: A Practical Guide to Productive Academic Writing . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2007; Style, Diction, Tone, and Voice. Writing Center, Wheaton College; Sword, Helen. Stylish Academic Writing . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.

Strategies for...

Understanding Academic Writing and Its Jargon

The very definition of research jargon is language specific to a particular community of practitioner-researchers . Therefore, in modern university life, jargon represents the specific language and meaning assigned to words and phrases specific to a discipline or area of study. For example, the idea of being rational may hold the same general meaning in both political science and psychology, but its application to understanding and explaining phenomena within the research domain of a each discipline may have subtle differences based upon how scholars in that discipline apply the concept to the theories and practice of their work.

Given this, it is important that specialist terminology [i.e., jargon] must be used accurately and applied under the appropriate conditions . Subject-specific dictionaries are the best places to confirm the meaning of terms within the context of a specific discipline. These can be found by either searching in the USC Libraries catalog by entering the disciplinary and the word dictionary [e.g., sociology and dictionary] or using a database such as Credo Reference [a curated collection of subject encyclopedias, dictionaries, handbooks, guides from highly regarded publishers] . It is appropriate for you to use specialist language within your field of study, but you should avoid using such language when writing for non-academic or general audiences.

Problems with Opaque Writing

A common criticism of scholars is that they can utilize needlessly complex syntax or overly expansive vocabulary that is impenetrable or not well-defined. When writing, avoid problems associated with opaque writing by keeping in mind the following:

1. Excessive use of specialized terminology . Yes, it is appropriate for you to use specialist language and a formal style of expression in academic writing, but it does not mean using "big words" just for the sake of doing so. Overuse of complex or obscure words or writing complicated sentence constructions gives readers the impression that your paper is more about style than substance; it leads the reader to question if you really know what you are talking about. Focus on creating clear, concise, and elegant prose that minimizes reliance on specialized terminology.

2. Inappropriate use of specialized terminology . Because you are dealing with concepts, research, and data within your discipline, you need to use the technical language appropriate to that area of study. However, nothing will undermine the validity of your study quicker than the inappropriate application of a term or concept. Avoid using terms whose meaning you are unsure of--do not just guess or assume! Consult the meaning of terms in specialized, discipline-specific dictionaries by searching the USC Libraries catalog or the Credo Reference database [see above].

Additional Problems to Avoid

In addition to understanding the use of specialized language, there are other aspects of academic writing in the social sciences that you should be aware of. These problems include:

- Personal nouns . Excessive use of personal nouns [e.g., I, me, you, us] may lead the reader to believe the study was overly subjective. These words can be interpreted as being used only to avoid presenting empirical evidence about the research problem. Limit the use of personal nouns to descriptions of things you actually did [e.g., "I interviewed ten teachers about classroom management techniques..."]. Note that personal nouns are generally found in the discussion section of a paper because this is where you as the author/researcher interpret and describe your work.

- Directives . Avoid directives that demand the reader to "do this" or "do that." Directives should be framed as evidence-based recommendations or goals leading to specific outcomes. Note that an exception to this can be found in various forms of action research that involve evidence-based advocacy for social justice or transformative change. Within this area of the social sciences, authors may offer directives for action in a declarative tone of urgency.

- Informal, conversational tone using slang and idioms . Academic writing relies on excellent grammar and precise word structure. Your narrative should not include regional dialects or slang terms because they can be open to interpretation. Your writing should be direct and concise using standard English.

- Wordiness. Focus on being concise, straightforward, and developing a narrative that does not have confusing language . By doing so, you help eliminate the possibility of the reader misinterpreting the design and purpose of your study.

- Vague expressions (e.g., "they," "we," "people," "the company," "that area," etc.). Being concise in your writing also includes avoiding vague references to persons, places, or things. While proofreading your paper, be sure to look for and edit any vague or imprecise statements that lack context or specificity.

- Numbered lists and bulleted items . The use of bulleted items or lists should be used only if the narrative dictates a need for clarity. For example, it is fine to state, "The four main problems with hedge funds are:" and then list them as 1, 2, 3, 4. However, in academic writing, this must then be followed by detailed explanation and analysis of each item. Given this, the question you should ask yourself while proofreading is: why begin with a list in the first place rather than just starting with systematic analysis of each item arranged in separate paragraphs? Also, be careful using numbers because they can imply a ranked order of priority or importance. If none exists, use bullets and avoid checkmarks or other symbols.

- Descriptive writing . Describing a research problem is an important means of contextualizing a study. In fact, some description or background information may be needed because you can not assume the reader knows the key aspects of the topic. However, the content of your paper should focus on methodology, the analysis and interpretation of findings, and their implications as they apply to the research problem rather than background information and descriptions of tangential issues.

- Personal experience. Drawing upon personal experience [e.g., traveling abroad; caring for someone with Alzheimer's disease] can be an effective way of introducing the research problem or engaging your readers in understanding its significance. Use personal experience only as an example, though, because academic writing relies on evidence-based research. To do otherwise is simply story-telling.

NOTE: Rules concerning excellent grammar and precise word structure do not apply when quoting someone. A quote should be inserted in the text of your paper exactly as it was stated. If the quote is especially vague or hard to understand, consider paraphrasing it or using a different quote to convey the same meaning. Consider inserting the term "sic" in brackets after the quoted text to indicate that the quotation has been transcribed exactly as found in the original source, but the source had grammar, spelling, or other errors. The adverb sic informs the reader that the errors are not yours.

Academic Writing. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Academic Writing Style. First-Year Seminar Handbook. Mercer University; Bem, Daryl J. Writing the Empirical Journal Article. Cornell University; College Writing. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Murray, Rowena and Sarah Moore. The Handbook of Academic Writing: A Fresh Approach . New York: Open University Press, 2006; Johnson, Eileen S. “Action Research.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education . Edited by George W. Noblit and Joseph R. Neikirk. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020); Oppenheimer, Daniel M. "Consequences of Erudite Vernacular Utilized Irrespective of Necessity: Problems with Using Long Words Needlessly." Applied Cognitive Psychology 20 (2006): 139-156; Ezza, El-Sadig Y. and Touria Drid. T eaching Academic Writing as a Discipline-Specific Skill in Higher Education . Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2020; Pernawan, Ari. Common Flaws in Students' Research Proposals. English Education Department. Yogyakarta State University; Style. College Writing. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Invention: Five Qualities of Good Writing. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Sword, Helen. Stylish Academic Writing . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012; What Is an Academic Paper? Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Improving Academic Writing

To improve your academic writing skills, you should focus your efforts on three key areas: 1. Clear Writing . The act of thinking about precedes the process of writing about. Good writers spend sufficient time distilling information and reviewing major points from the literature they have reviewed before creating their work. Writing detailed outlines can help you clearly organize your thoughts. Effective academic writing begins with solid planning, so manage your time carefully. 2. Excellent Grammar . Needless to say, English grammar can be difficult and complex; even the best scholars take many years before they have a command of the major points of good grammar. Take the time to learn the major and minor points of good grammar. Spend time practicing writing and seek detailed feedback from professors. Take advantage of the Writing Center on campus if you need help. Proper punctuation and good proofreading skills can significantly improve academic writing [see sub-tab for proofreading you paper ].

Refer to these three basic resources to help your grammar and writing skills:

- A good writing reference book, such as, Strunk and White’s book, The Elements of Style or the St. Martin's Handbook ;

- A college-level dictionary, such as, Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary ;

- The latest edition of Roget's Thesaurus in Dictionary Form .

3. Consistent Stylistic Approach . Whether your professor expresses a preference to use MLA, APA or the Chicago Manual of Style or not, choose one style manual and stick to it. Each of these style manuals provide rules on how to write out numbers, references, citations, footnotes, and lists. Consistent adherence to a style of writing helps with the narrative flow of your paper and improves its readability. Note that some disciplines require a particular style [e.g., education uses APA] so as you write more papers within your major, your familiarity with it will improve.

II. Evaluating Quality of Writing

A useful approach for evaluating the quality of your academic writing is to consider the following issues from the perspective of the reader. While proofreading your final draft, critically assess the following elements in your writing.

- It is shaped around one clear research problem, and it explains what that problem is from the outset.

- Your paper tells the reader why the problem is important and why people should know about it.

- You have accurately and thoroughly informed the reader what has already been published about this problem or others related to it and noted important gaps in the research.

- You have provided evidence to support your argument that the reader finds convincing.

- The paper includes a description of how and why particular evidence was collected and analyzed, and why specific theoretical arguments or concepts were used.

- The paper is made up of paragraphs, each containing only one controlling idea.

- You indicate how each section of the paper addresses the research problem.

- You have considered counter-arguments or counter-examples where they are relevant.

- Arguments, evidence, and their significance have been presented in the conclusion.

- Limitations of your research have been explained as evidence of the potential need for further study.

- The narrative flows in a clear, accurate, and well-organized way.

Boscoloa, Pietro, Barbara Arféb, and Mara Quarisaa. “Improving the Quality of Students' Academic Writing: An Intervention Study.” Studies in Higher Education 32 (August 2007): 419-438; Academic Writing. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Academic Writing Style. First-Year Seminar Handbook. Mercer University; Bem, Daryl J. Writing the Empirical Journal Article. Cornell University; Candlin, Christopher. Academic Writing Step-By-Step: A Research-based Approach . Bristol, CT: Equinox Publishing Ltd., 2016; College Writing. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Style . College Writing. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Invention: Five Qualities of Good Writing. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Sword, Helen. Stylish Academic Writing . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012; What Is an Academic Paper? Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College.

Writing Tip

Considering the Passive Voice in Academic Writing

In the English language, we are able to construct sentences in the following way: 1. "The policies of Congress caused the economic crisis." 2. "The economic crisis was caused by the policies of Congress."

The decision about which sentence to use is governed by whether you want to focus on “Congress” and what they did, or on “the economic crisis” and what caused it. This choice in focus is achieved with the use of either the active or the passive voice. When you want your readers to focus on the "doer" of an action, you can make the "doer"' the subject of the sentence and use the active form of the verb. When you want readers to focus on the person, place, or thing affected by the action, or the action itself, you can make the effect or the action the subject of the sentence by using the passive form of the verb.

Often in academic writing, scholars don't want to focus on who is doing an action, but on who is receiving or experiencing the consequences of that action. The passive voice is useful in academic writing because it allows writers to highlight the most important participants or events within sentences by placing them at the beginning of the sentence.

Use the passive voice when:

- You want to focus on the person, place, or thing affected by the action, or the action itself;

- It is not important who or what did the action;

- You want to be impersonal or more formal.

Form the passive voice by:

- Turning the object of the active sentence into the subject of the passive sentence.

- Changing the verb to a passive form by adding the appropriate form of the verb "to be" and the past participle of the main verb.

NOTE: Consult with your professor about using the passive voice before submitting your research paper. Some strongly discourage its use!

Active and Passive Voice. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Diefenbach, Paul. Future of Digital Media Syllabus. Drexel University; Passive Voice. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina.

- << Previous: 2. Preparing to Write

- Next: Choosing a Title >>

- Last Updated: Apr 5, 2024 1:38 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

An Introduction to Academic Writing

Characteristics and Common Mistakes to Avoid

- An Introduction to Punctuation

Olivia Valdes was the Associate Editorial Director for ThoughtCo. She worked with Dotdash Meredith from 2017 to 2021.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Olivia-Valdes_WEB1-1e405fc799d9474e9212215c4f21b141.jpg)

- B.A., American Studies, Yale University

Students, professors, and researchers in every discipline use academic writing to convey ideas, make arguments, and engage in scholarly conversation. Academic writing is characterized by evidence-based arguments, precise word choice, logical organization, and an impersonal tone. Though sometimes thought of as long-winded or inaccessible, strong academic writing is quite the opposite: It informs, analyzes, and persuades in a straightforward manner and enables the reader to engage critically in a scholarly dialogue.

Examples of Academic Writing

Academic writing is, of course, any formal written work produced in an academic setting. While academic writing comes in many forms, the following are some of the most common.

Literary analysis : A literary analysis essay examines, evaluates, and makes an argument about a literary work. As its name suggests, a literary analysis essay goes beyond mere summarization. It requires careful close reading of one or multiple texts and often focuses on a specific characteristic, theme, or motif.

Research paper : A research paper uses outside information to support a thesis or make an argument. Research papers are written in all disciplines and may be evaluative, analytical, or critical in nature. Common research sources include data, primary sources (e.g., historical records), and secondary sources (e.g., peer-reviewed scholarly articles ). Writing a research paper involves synthesizing this external information with your own ideas.

Dissertation : A dissertation (or thesis) is a document submitted at the conclusion of a Ph.D. program. The dissertation is a book-length summarization of the doctoral candidate’s research.

Academic papers may be done as a part of a class, in a program of study, or for publication in an academic journal or scholarly book of articles around a theme, by different authors.

Characteristics of Academic Writing

Most academic disciplines employ their own stylistic conventions. However, all academic writing shares certain characteristics.

- Clear and limited focus . The focus of an academic paper—the argument or research question—is established early by the thesis statement. Every paragraph and sentence of the paper connects back to that primary focus. While the paper may include background or contextual information, all content serves the purpose of supporting the thesis statement.

- Logical structure . All academic writing follows a logical, straightforward structure. In its simplest form, academic writing includes an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. The introduction provides background information, lays out the scope and direction of the essay, and states the thesis. The body paragraphs support the thesis statement, with each body paragraph elaborating on one supporting point. The conclusion refers back to the thesis, summarizes the main points, and highlights the implications of the paper’s findings. Each sentence and paragraph logically connects to the next in order to present a clear argument.

- Evidence-based arguments . Academic writing requires well-informed arguments. Statements must be supported by evidence, whether from scholarly sources (as in a research paper), results of a study or experiment, or quotations from a primary text (as in a literary analysis essay). The use of evidence gives credibility to an argument.

- Impersonal tone . The goal of academic writing is to convey a logical argument from an objective standpoint. Academic writing avoids emotional, inflammatory, or otherwise biased language. Whether you personally agree or disagree with an idea, it must be presented accurately and objectively in your paper.

Most published papers also have abstracts: brief summaries of the most important points of the paper. Abstracts appear in academic database search results so that readers can quickly determine whether the paper is pertinent to their own research.

The Importance of Thesis Statements

Let’s say you’ve just finished an analytical essay for your literature class. If a peer or professor asks you what the essay is about—what the point of the essay is—you should be able to respond clearly and concisely in a single sentence. That single sentence is your thesis statement.

The thesis statement, found at the end of the first paragraph, is a one-sentence encapsulation of your essay’s main idea. It presents an overarching argument and may also identify the main support points for the argument. In essence, the thesis statement is a road map, telling the reader where the paper is going and how it will get there.

The thesis statement plays an important role in the writing process. Once you’ve written a thesis statement, you’ve established a clear focus for your paper. Frequently referring back to that thesis statement will prevent you from straying off-topic during the drafting phase. Of course, the thesis statement can (and should) be revised to reflect changes in the content or direction of the paper. Its ultimate goal, after all, is to capture the main ideas of your paper with clarity and specificity.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Academic writers from every field face similar challenges during the writing process. You can improve your own academic writing by avoiding these common mistakes.

- Wordiness . The goal of academic writing is to convey complex ideas in a clear, concise manner. Don’t muddy the meaning of your argument by using confusing language. If you find yourself writing a sentence over 25 words long, try to divide it into two or three separate sentences for improved readability.

- A vague or missing thesis statement . The thesis statement is the single most important sentence in any academic paper. Your thesis statement must be clear, and each body paragraph needs to tie into that thesis.

- Informal language . Academic writing is formal in tone and should not include slang, idioms, or conversational language.

- Description without analysis . Do not simply repeat the ideas or arguments from your source materials. Rather, analyze those arguments and explain how they relate to your point.

- Not citing sources . Keep track of your source materials throughout the research and writing process. Cite them consistently using one style manual ( MLA , APA, or Chicago Manual of Style, depending on the guidelines given to you at the outset of the project). Any ideas that are not your own need to be cited, whether they're paraphrased or quoted directly, to avoid plagiarism.

- What an Essay Is and How to Write One

- How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

- The Ultimate Guide to the 5-Paragraph Essay

- How to Write a Critical Essay

- What Is Expository Writing?

- How to Write a Solid Thesis Statement

- How to Help Your 4th Grader Write a Biography

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- Definition and Examples of Body Paragraphs in Composition

- How To Write an Essay

- What Is a Research Paper?

- What Is a Literature Review?

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- 3 Changes That Will Take Your Essay From Good To Great

- Composition Type: Problem-Solution Essays

- Beef Up Critical Thinking and Writing Skills: Comparison Essays

- Skip to main content

- assistive.skiplink.to.breadcrumbs

- assistive.skiplink.to.header.menu

- assistive.skiplink.to.action.menu

- assistive.skiplink.to.quick.search

- A t tachments (2)

- Page History

- Page Information

- Resolved comments

- View in Hierarchy

- View Source

- Export to PDF

- Export to Word

Module 1: What is academic writing

- Created by Maura Ferrarini Meagher , last modified by Kris M Markman on Jun 09, 2017

To introduce students to the genres/broad conventions of academic writing across Harvard

Learning Objectives

Students will be able to:

- define scholarly conversation

- articulate the commonly used writing genres in academic writing

- articulate the difference between academic writing and non-academic writing

Graduate students

Content Brainstorm

Defining scholarly conversation

- Academic writing

Brief definitions of writing genres and how the conversation encompasses ALL of these

Idea of having an interactive map that branches to show the connections between schools and the types of writing they do and vice versa (types of writing and what schools use them) - discuss this with Damien from HILT and Hugh Truslow (and the data visualization hire, TBD)

DEFINE scholarly conversation.

Academic writing at the graduate level is different from other writing you may have done in the past, in that you are often being asked to contribute to the "scholarly conversation," that is, to engage in dialogue with the work of other researchers and/or practitioners in your discipline. We talk about this writing as conversation because the final product you produce does more than just summarize what others have said. Rather, you will be expected to contribute your own original insights, research findings, or arguments, and show how your contributions relate to the existing literature in your field.

What is the difference between academic and non-academic writing?

Formality, tone, adherence to certain formats, certain citation styles required.

LIST and DEFINE writing genres commonly used in academic writing.

thesis/dissertation

policy paper - A policy paper presents research on a specific issue facing a government or organization and makes actionable recommendations to the organization. Here's the HKS Policy Analysis Exercise page - https://www.hks.harvard.edu/degrees/masters/mpp/curriculum/pae

literature review

case studies (I know they are used to teach - does anybody at Harvard require writing them?) - Not that I'm aware but HBS has this resource page on writing cases - http://www.hbs.edu/teaching/resources/Pages/default.aspx

white paper - A white paper markets a project or proposes a solution to a problem. Typically around ten pages, its aim is to provide the reader with essential details to understand the topic and the reasoning behind the proposed solution(s).- https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/546/1/

Secondary Research (Or would it be more clear to call this an Academic Paper, as HGSE did below?) An Academic Paper, sometimes referred to as a Research Paper, is an analysis and synthesis of sources, in service of a question and/or theory. This is different from original research because you are not conducting research studies, but instead relying on primary, secondary, and tertiary sources to develop your paper. These papers are not designed to simply be summaries of research; the writer is engaged in the scholarly conversation by contributing an original voice through the synthesis of information and pursuit of a question or theory.

HGSE Academic Writing Assignment Types (from beta Canvas site):

Terms to Define

- Scholarly conversation

- Types of writing documents (extensive list here https://www.ndsu.edu/cfwriters/genres/ so we can choose what we think is relevant to our audience)