History Cooperative

How Did Christianity Spread: Origins, Expansion, and Impact

Christianity spread gradually over the course of several centuries and through a combination of various factors and events. From the original teachings of Jesus Christ and those of his apostles to early Christian communities, the influence of the Roman Empire, missionary work, and the foundation of churches and monasteries, many factors contributed to the spreading of now one of the world’s most popular religions.

Table of Contents

How Did Christianity Spread? What Led to the Rise of Christianity?

There are multiple factors and influences that contributed to the spreading of Christianity and its growth, such as encompassing the teachings of Jesus, the formation of early Christian communities, and the enduring legacy of martyrdom and persecution. These elements provide insights into the remarkable ascent of Christianity and its profound global influence.

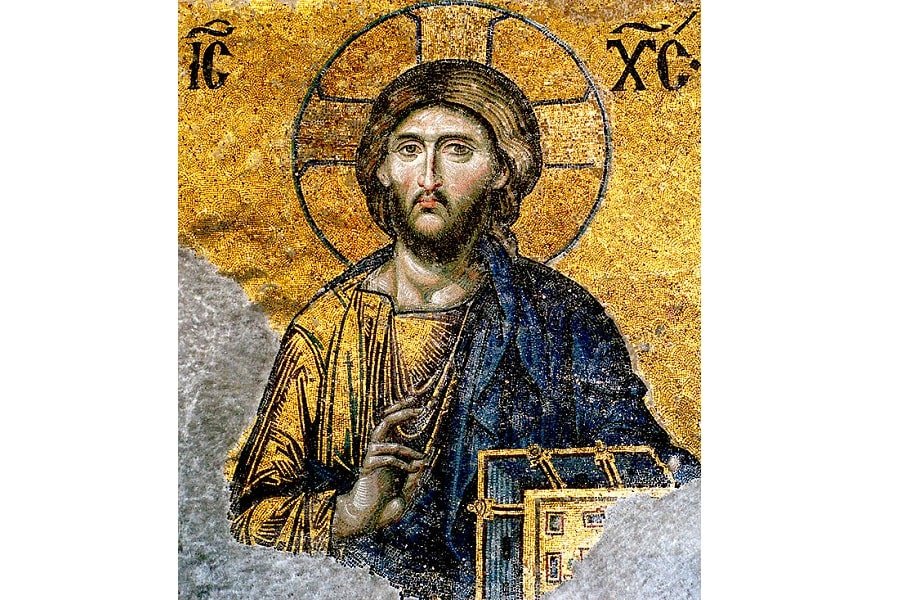

The Life and Teachings of Jesus

The life and teachings of Jesus serve as the foundation of Christianity. Jesus, born in Bethlehem and raised in Nazareth[4], embarked on a ministry that profoundly impacted his followers. His teachings encompassed a wide range of topics, including morality, spirituality, love, forgiveness, and the kingdom of God. Through his parables, such as the Good Samaritan, the Prodigal Son, and the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus communicated profound moral and ethical lessons that challenged the prevailing social norms of the time . He emphasized the importance of loving one’s neighbor, caring for the marginalized, and treating others with compassion and empathy[7]. Jesus’ teachings went beyond mere religious observance, calling for a personal relationship with God and the transformation of one’s inner being. His authority and wisdom were evident in his ability to heal the sick, perform miracles, and engage in deep theological discussions with religious leaders, captivating audiences with his profound insights.

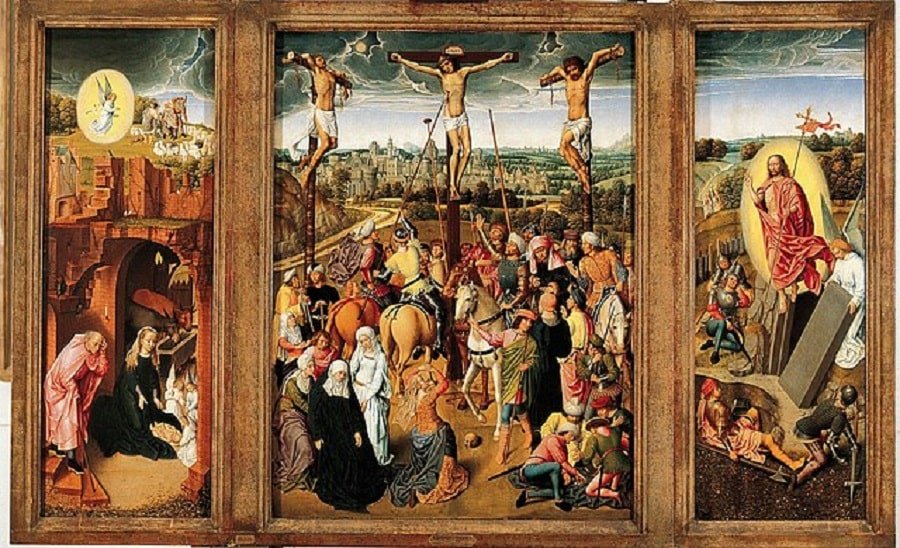

Crucifixion and Resurrection

The crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus form the central pillars of Christian belief. Jesus’ crucifixion took place in Jerusalem, where he was condemned to death by the Roman authorities. This form of execution was exceptionally brutal, involving the nailing or binding of a person to a wooden cross. Christians believe that Jesus willingly endured this horrific death as a sacrifice to atone for humanity’s sins[4]. The crucifixion represents Jesus’ ultimate act of love and redemption, bearing the weight of humanity’s transgressions. However, the story does not end there. According to Christian belief, Jesus conquered death through his resurrection. On the third day after his crucifixion, Jesus rose from the dead, appearing to his followers and solidifying their conviction in his divine nature and mission. The resurrection is seen as a victory over sin and death, offering hope to believers and affirming the promise of eternal life.

Formation of Early Christian Communities

Following Jesus’ death and resurrection, early Christian communities began to emerge. The Twelve Apostles[3], chosen by Jesus during his ministry, played a crucial role in the formation and leadership of these communities. They were entrusted with carrying forward Jesus’ teachings and establishing the early Church. The apostles provided spiritual guidance, settled disputes, and fostered unity among believers. They were witnesses to Jesus’ life, teachings, crucifixion, and resurrection[6], making them instrumental in preserving the authenticity of the Christian message. The early Christian communities were characterized by a strong sense of communal living, shared resources, and collective worship. Believers supported one another, pooling their possessions to meet the needs of the community. They gathered for worship, prayer, and the breaking of bread, creating a bond that transcended societal divisions and fostered a distinct identity as followers of Jesus Christ.

Martyrdom and Persecution

The rise of Christianity was accompanied by periods of intense persecution, particularly under the Roman Empire . Early Christians faced hostility and persecution for various reasons. They refused to worship the Roman emperors as a deity[1], considering it a direct violation of their monotheistic faith. Moreover, their refusal to participate in pagan rituals and practices, which were integral to the social fabric of the time, further alienated them from mainstream society. Many Christians endured persecution, imprisonment, and even death for their unwavering commitment to their faith. These individuals, known as martyrs, became powerful symbols of Christian devotion and sacrifice. Their steadfastness in the face of adversity inspired awe and admiration among fellow believers, solidifying their resolve and dedication to the Christian movement. The martyrdom [2] of early Christians served to strengthen the resolve of believers, propagate the faith, and exemplify the transformative power of a personal relationship with Jesus Christ.

How Did Christianity Spread to the US?

European colonization and christianization.

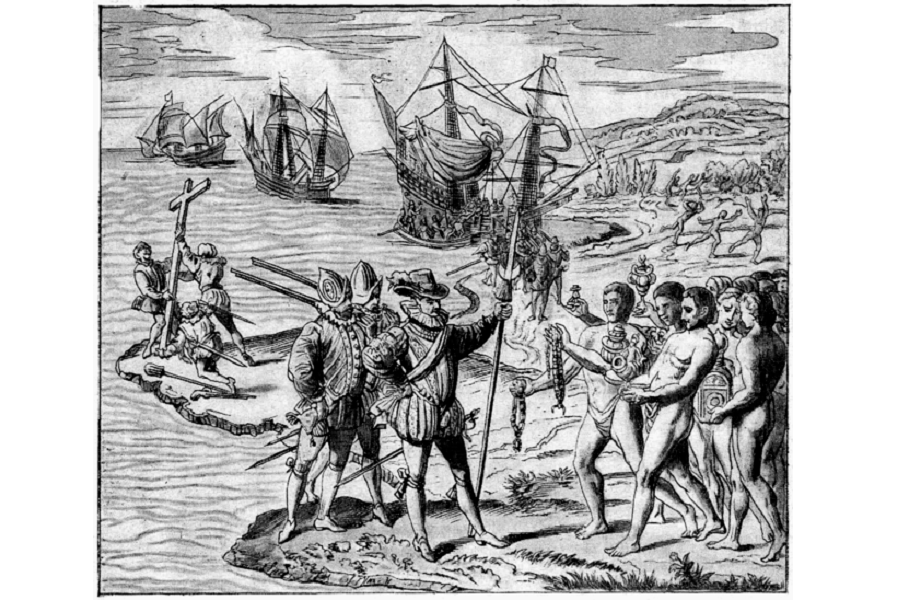

The arrival of European explorers and settlers in the Americas brought Christianity to the region. Spanish expeditions led by Christopher Columbus, Juan Ponce de León, and Hernando de Soto introduced Catholicism to areas such as Florida and the Southwest[2]. Catholic missionaries, including Franciscans and Jesuits, played a crucial role in the Christianization of Native American communities. They established missions and schools to teach Christianity, often blending indigenous traditions with Catholic rituals[3]. The Spanish Crown saw the conversion of indigenous peoples as a means of solidifying their control over the territories and fostering cultural assimilation.

READ MORE: Who Discovered America: The First People Who Reached the Americas

Similarly, English colonists, particularly the Pilgrims and Puritans, played a vital role in spreading Christianity. Seeking religious freedom, these groups settled primarily in New England. They established communities centered around congregational churches and strict adherence to biblical teachings [4]. The Puritans aimed to create a godly society based on their interpretation of Christianity. Their emphasis on personal piety, moral codes, and communal religious practices influenced the development of a distinct religious identity in New England.

Puritan Settlers and the Great Awakening

The settlement of Puritans in the 17th century[3] significantly impacted the spread of Christianity in the US. Their commitment to religious reform and adherence to biblical principles shaped the social, political, and religious landscape of New England. Puritan communities fostered strong religious discipline, combining church and state authority to enforce moral codes. They believed in the idea of a “covenant” with God, wherein obedience to God’s laws would ensure prosperity and divine favor[7].

The Great Awakening, an 18th-century religious revival, further fueled the growth of Christianity in the American colonies[7]. It was characterized by passionate sermons, emotional conversions, and fervent religious experiences. Prominent preachers like Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield drew large crowds with their compelling oratory. The Great Awakening emphasized the importance of personal salvation and a direct, emotional connection with God. It challenged the established religious order and encouraged individuals to actively seek spiritual transformation. The revival sparked renewed religious fervor, leading to the formation of new churches[2], the spread of evangelicalism, and the rise of itinerant preachers.

Influence of Evangelical Revival

The 19th century witnessed the influence of evangelical revivals in spreading Christianity across the United States. Influential figures like Charles Finney and Dwight L. Moody led these revivals, which aimed to revive religious faith and promote personal conversion experiences. Revival meetings, often held in temporary camp structures, drew large crowds and created an atmosphere of religious fervor. These gatherings featured passionate preaching, heartfelt prayer[7], and emotional expressions of faith. The revivals sought to awaken individuals to their need for salvation, encourage moral reform, and inspire active engagement in evangelism and missionary work. They played a vital role in shaping the religious landscape of the United States, leading to the establishment of new churches, the growth of existing denominations, and the formation of Christian institutions[3].

Denominational Expansion and Diversity

As the United States experienced significant growth and attracted immigrants from different parts of the world, the religious landscape became increasingly diverse. Protestant denominations expanded their reach across the country through missionary efforts, church planting, and the establishment of educational institutions[5]. Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, and Episcopalians were among the prominent Protestant denominations that saw considerable growth during this period. Baptists[7], with their emphasis on individual liberty and believer’s baptism, established congregations throughout the country, particularly in the South. Methodists[6], known for their circuit-riding preachers and emphasis on personal piety, experienced rapid expansion across urban and rural areas. Presbyterians[7], with their strong Calvinist roots, established churches and educational institutions, contributing to the intellectual development of their followers. Episcopalians[7], influenced by Anglican traditions, maintained a significant presence, especially among the colonial elite.

The Catholic Church also witnessed significant growth in the United States, primarily fueled by immigration. The arrival of Irish, Italian, and other European Catholic immigrants in the 19th and early 20th centuries brought a surge in the Catholic population and the establishment of numerous parishes, schools, and social service organizations[3]. The Catholic Church played a vital role in providing spiritual and social support to immigrant communities, helping them preserve their cultural identity while integrating into American society.

The United States also became a hub for diverse Christian denominations originating from different parts of the world. Orthodox Christian churches, including the Greek Orthodox and Russian Orthodox, established congregations, reflecting the religious heritage of immigrant populations from Eastern Europe and the Middle East[2]. Protestant denominations such as the Lutheran Church and the Reformed Church found followers among European immigrants, each bringing their distinct theological and liturgical traditions. Eastern Christian communities, such as the Maronite Catholics and the Coptic Orthodox[6], maintained their religious traditions and established churches in the United States, adding to the rich tapestry of Christian diversity.

The Power of Calvinism: Fueling the Spread of Christianity

Calvinism and its powering factors worked synergistically, creating a fertile ground for the growth and impact of Christianity in various parts of the world. Calvinism’s influence extended beyond theological circles, leaving a lasting legacy in the history of Christianity and shaping the development of Christian traditions globally.

Theological Clarity and Doctrinal Precision

Calvinism’s theological clarity and emphasis on doctrinal precision were instrumental in the spread of Christianity. The system provided a comprehensive framework for believers to understand and articulate their faith. Concepts like predestination, the sovereignty of God, and the depravity of humankind offered a coherent and intellectually robust understanding of Christianity. This theological clarity not only attracted followers within Calvinist circles but also appealed to those seeking a well-defined and structured belief system.

Missionary Zeal and Global Expansion

Calvinism demonstrated remarkable missionary zeal, driving believers to actively engage in spreading Christianity worldwide. Calvinist communities established missionary organizations and sent missionaries to various parts of the world, including Africa, Asia, and the Americas. These missionaries were motivated by their faith and conviction to share the Gospel with unreached populations. Their efforts resulted in the establishment of Reformed churches, the conversion of individuals, and the growth of Christianity in new territories.

Educational Emphasis

Education played a significant role in the spread of Calvinism and Christianity. Calvinist communities placed a strong emphasis on education, establishing schools, colleges, and universities. These institutions provided believers with intellectual and theological training, equipping them to engage in evangelistic activities and effectively communicate their faith. The emphasis on education fostered a culture of intellectual engagement, critical thinking, and theological literacy among Calvinist followers. This educated cadre of believers played a vital role in advancing the spread of Christianity through their knowledge, skills, and ability to engage with diverse audiences.

Sociopolitical Influence

Calvinism’s teachings had a profound impact on the social and political landscape, contributing to the spread of Christianity. The emphasis on individual responsibility, moral values, and the worth of every individual influenced societies in profound ways. Calvinist principles played a role in shaping political systems that promoted religious freedom, tolerance, and social justice. The sociopolitical influence of Calvinism created an environment conducive to the growth of Christianity, allowing believers to freely practice and share their faith.

Reformed Church Networks

The establishment of Reformed churches and their organizational structures facilitated the spread of Calvinism and Christianity. Reformed churches provided a network for believers to connect, collaborate, and support each other in their evangelistic endeavors. The sense of community within these churches strengthened the spread of Christianity as believers worked together to share the Gospel and disciple new converts. The establishment of denominational structures also provided a framework for theological training, leadership development, and the coordination of missionary efforts.

How Christianity Spread Throughout Europe?

Early Christian Missionaries

The spread of Christianity throughout Europe was initiated by early Christian missionaries who embarked on arduous journeys to bring the message of Jesus Christ to new lands. These missionaries, such as Paul the Apostle and other disciples, traveled extensively, often enduring significant hardships, to establish communities of believers and spread the teachings of Christianity. They faced cultural and linguistic challenges as they encountered diverse populations[1], adapting their approach to effectively communicate the Gospel. Despite persecution and resistance, their unwavering dedication and commitment to their mission laid the foundation for the growth and expansion of Christianity across Europe.

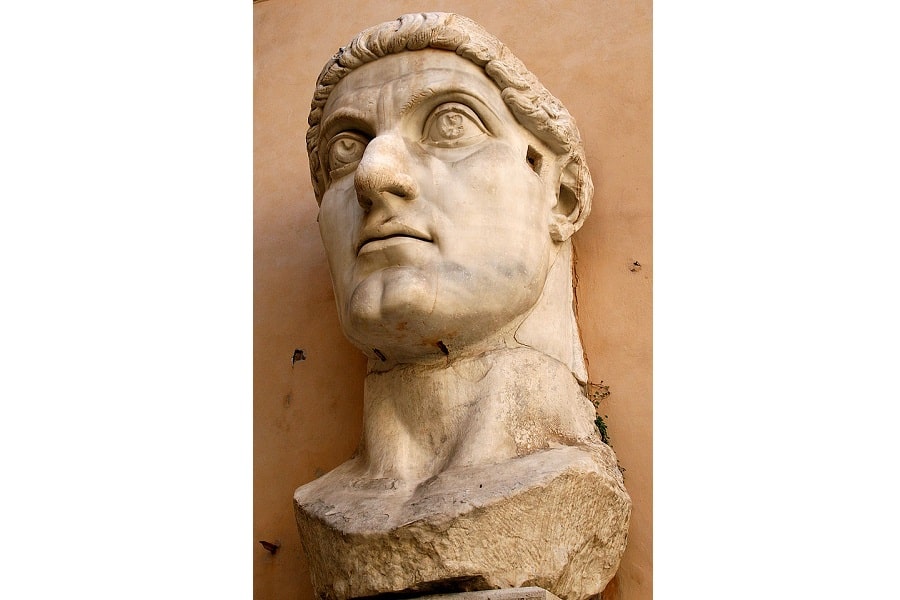

Conversion of the Roman Empire

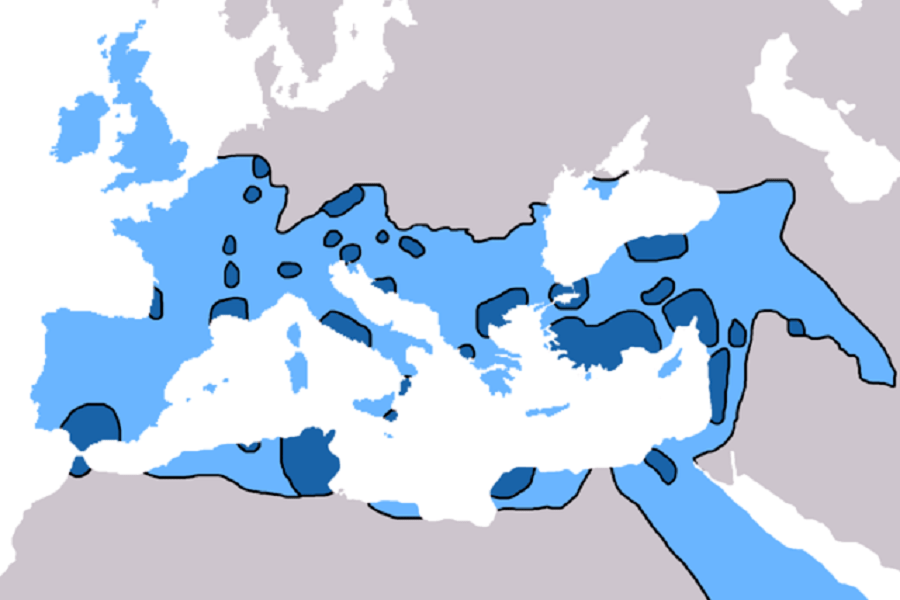

One of the pivotal factors in the spread of Christianity throughout Europe was the conversion of the Roman Empire. The conversion of Emperor Constantine to Christianity in the 4th century CE marked a significant turning point. With the Edict of Milan in 313 CE[3], Christianity was officially tolerated, and it eventually became the favored religion of the empire. This shift in imperial support provided Christians with a level of legitimacy and allowed for the construction of churches, the spread of Christian teachings, and the conversion of a substantial portion of the Roman population. The influence of Christianity expanded as it became intertwined with the political and cultural fabric of the empire.

Christianization of Barbarian Kingdoms

Following the decline of the Roman Empire, Europe witnessed the migration and establishment of various barbarian kingdoms[1]. These kingdoms, including the Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Vandals, and Franks, gradually embraced Christianity through a process known as Christianization. Christian missionaries played a crucial role in this process, entering these territories and working to convert their rulers and populations. They adapted their approach to resonate with the values and beliefs of these societies, incorporating elements of local customs and traditions into Christian practices. The conversion of these Barbarian kingdoms not only spread Christianity geographically but also influenced the culture, laws, and governance of these societies. Christian principles began to shape the legal systems and moral frameworks of these kingdoms, impacting their social structures and practices[5].

Role of Monasticism and Monastic Centers

Monasticism played a significant role in the spread of Christianity throughout Europe. Monastic communities, such as those established by Saint Benedict of Nursia[3], emerged as centers of religious devotion, scholarship, and missionary activity. Monasteries served as educational institutions, preserving and disseminating knowledge, including theological teachings, classical texts, and practical skills. Monastic centers also became hubs for missionary efforts, sending out monks and nuns to evangelize and establish new Christian communities in distant regions. These monastic networks provided a framework for the organized spread of Christianity, with monastic orders playing pivotal roles in the conversion and Christianization of various regions in Europe. Monasticism also influenced the development of art, architecture, agriculture, and healthcare, contributing to the overall cultural and societal transformation brought about by Christianity[4].

Who Spread Christianity?

The apostles and early disciples.

The initial spread of Christianity can be attributed to the apostles and early disciples of Jesus Christ. After the death and resurrection of Jesus, these devoted followers began proclaiming the Gospel message. Peter, one of the prominent apostles, played a crucial role in spreading Christianity to Jewish communities. James, the brother of Jesus, served as a key leader in the early Christian movement in Jerusalem[3]. John, another apostle, played a significant role in establishing Christian communities and authoring important biblical texts. These early disciples, empowered by the Holy Spirit, fearlessly shared the teachings of Jesus, attracting converts and establishing the foundation of the early Christian Church.

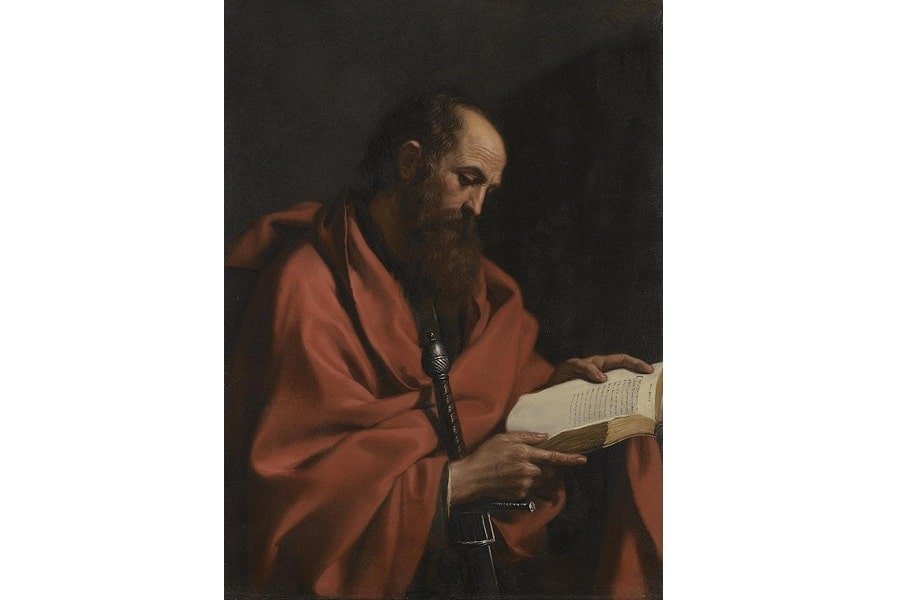

Paul the Apostle and Missionary Journeys

Paul the Apostle, formerly known as Saul, made remarkable contributions to the spread of Christianity through his missionary journeys. Following his conversion on the road to Damascus, Paul became one of the most influential figures in the early Christian movement. He embarked on several missionary journeys, traveling throughout the Roman Empire to establish new Christian communities. Paul’s journeys took him to cities such as Antioch, Ephesus, Corinth, and Rome , where he preached the Gospel, established churches, and wrote letters to these communities[5]. His teachings focused on the reconciling power of Jesus’ death and resurrection and the inclusive nature of Christianity, welcoming both Jews and Gentiles into the faith. Paul’s efforts significantly contributed to expanding Christianity beyond its Jewish roots and developing a distinct Gentile Christian identity.

Byzantine Missionaries

During the Byzantine Empire, Christianity continued to spread through the efforts of Byzantine missionaries. These missionaries, often associated with monastic communities, ventured into new territories to convert and establish Christian communities. One notable example is the mission of Cyril and Methodius in the 9th century. These brothers, known as the “Apostles to the Slavs,” developed the Cyrillic alphabet and translated religious texts into Slavic languages. This translation work enabled the dissemination of Christian teachings in regions like Bulgaria, Serbia, and Russia, and laid the foundation for the Christianization of the Slavic peoples. The Byzantine missionaries played a vital role in spreading Orthodox Christianity and establishing its influence in Eastern Europe[5].

Medieval and Modern Missionaries

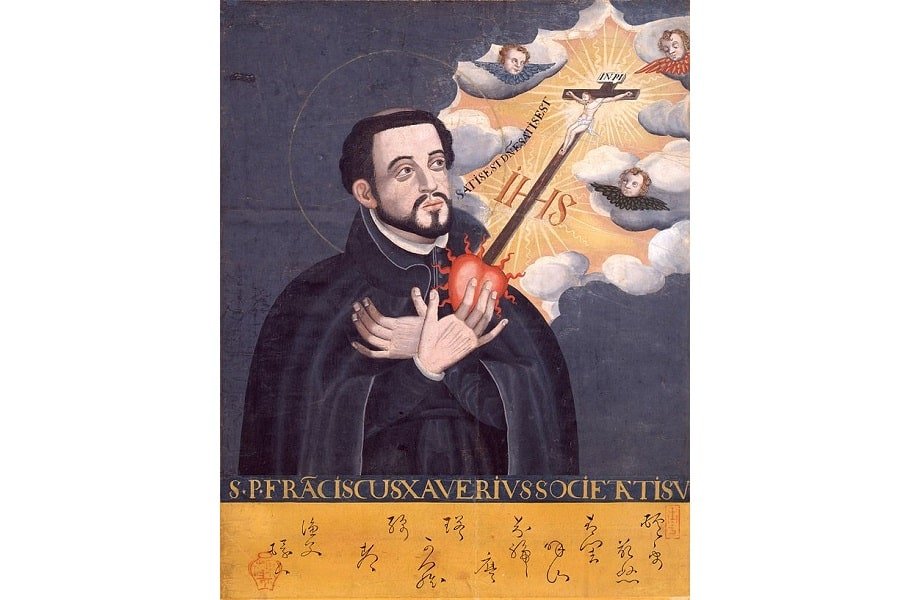

During the medieval period and beyond, Christianity continued to spread through the efforts of numerous missionaries. The Catholic Church, through orders like the Franciscans, Dominicans, and Jesuits, played a central role in sending missionaries to various parts of the world[5].

Catholic missionaries

Notable Catholic missionaries include Francis Xavier, who traveled to India, Japan, and other parts of Asia, and Matteo Ricci, who ventured to China. These missionaries faced immense challenges, encountering different cultures, languages, and religious beliefs. They adapted their approaches, learned local languages, and engaged in dialogue with indigenous peoples[1]. Their efforts resulted in the establishment of Christian communities and the integration of Christianity with local customs and traditions.

Protestant missionaries

In more recent times, Protestant missionaries have played a significant role in spreading Christianity globally. Particularly during the colonial era, Protestant missionaries from various denominations ventured to Africa, the Americas, Asia, and the Pacific Islands[4]. They established schools, hospitals, and churches, and engaged in evangelistic activities. These missionaries sought to bring the message of Christianity to indigenous peoples and often faced significant cultural, linguistic, and societal barriers. Their work contributed to the growth of Protestant Christianity worldwide.

The work of missionaries in translating and preserving religious texts, such as the Bible, into local languages has been instrumental in enabling people to access and understand Christian teachings[1]. They also played a significant role in the development of indigenous Christian expressions, blending elements of local culture and traditions with Christian beliefs and practices.

Furthermore, missionaries contributed to the development of educational institutions, establishing schools and universities that provided education and literacy to communities. They promoted the importance of knowledge, critical thinking, and intellectual growth, fostering advancements in various fields and disciplines.

When Did Christianity Spread?

Early christian era .

The spread of Christianity can be traced back to the early Christian era, specifically after the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ in the 1st century AD[5]. Following these events, the apostles and early disciples embarked on missionary journeys, spreading the teachings of Jesus throughout the Eastern Mediterranean region. The early Christian communities emerged primarily in cities such as Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria. Despite facing persecution and challenges, the message of Christianity spread among Jewish communities, Gentiles, and various ethnic groups, attracting followers and establishing the foundation of the early Christian Church[2].

Spread During the Roman Empire

The expansion of Christianity accelerated during the Roman Empire, particularly in the 4th century AD. Christianity gained significant traction under the patronage of Emperor Constantine, who issued the Edict of Milan in 313 AD[2], granting religious tolerance and freedom to Christians. The subsequent conversion of Constantine to Christianity and the adoption of Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire by Emperor Theodosius I in 380 AD marked pivotal moments in the spread of the faith. The imperial support provided resources and protection, leading to the construction of churches, the establishment of Christian theological and educational institutions, and the conversion of a considerable portion of the Roman population to Christianity[2].

Medieval Expansion and Conversion

During the Middle Ages, Christianity continued to spread, both geographically and among diverse populations. The conversion of barbarian kingdoms in Europe played a crucial role in expanding Christianity’s influence. Missionaries, such as St. Patrick in Ireland, St. Augustine of Canterbury in England , and Cyril and Methodius in Eastern Europe, ventured into pagan territories, preaching the Gospel and establishing Christian communities[2]. Additionally, the Crusades, which took place from the 11th to the 13th centuries, resulted in encounters between Christians and Muslims, leading to cultural and religious exchanges. While the Crusades were primarily military campaigns, they inadvertently facilitated the spread of Christianity to regions such as the Holy Land, the Eastern Mediterranean, and even parts of Eastern Europe.

Global Missionary Movements

From the 15th century onward, global missionary movements played a significant role in spreading Christianity to various parts of the world. The Age of Exploration and Colonization opened up opportunities for European Christian missionaries to venture into Africa, the Americas, Asia, and the Pacific Islands[4]. The Catholic Church, as well as Protestant denominations, sent missionaries to these regions with the aim of converting indigenous peoples and establishing Christian communities. Notable examples include the efforts of Catholic missionaries in Latin America, the Jesuit missions in China and Japan[6], and the Protestant missionary activities in Africa and India. These movements led to the establishment of Christian churches, the translation of religious texts into local languages, and the integration of Christianity with local customs and traditions.

Who Spread Christianity in Rome?

The spread of Christianity in Rome was a complex process influenced by various factors and individuals who played significant roles in its establishment and growth.

Early Christian Communities in Rome

The presence of early Christian communities in Rome was instrumental in the initial spread of Christianity. These communities likely emerged during the early years of the Christian movement through the efforts of Christian travelers, merchants, and Jewish converts to Christianity. These small Christian communities operated discreetly, gathering in private homes for worship and fellowship[6]. The early Christians faced periods of persecution under Roman authorities, as Christianity was not yet recognized as a legal religion. However, despite these challenges, the Christian faith continued to spread among the diverse population of Rome.

Influence of Paul the Apostle

One of the most influential figures in the spread of Christianity in Rome was Paul the Apostle, also known as St. Paul. Paul’s significant impact on Christianity can be attributed to his missionary journeys and epistles (letters) addressed to various Christian communities. According to biblical accounts, Paul traveled to Rome as a prisoner, but even in his captivity, he continued to spread the Gospel message and teach about Jesus Christ[3]. His teachings emphasized the reconciling power of Jesus’ death and resurrection, highlighting the core message of salvation through faith in Christ. Paul’s writings and teachings helped shape the early Christian theology in Rome and contributed to the growth and development of the Christian community.

Emperor Constantine and the Conversion of Rome

The conversion of Emperor Constantine to Christianity in the early 4th century AD played a pivotal role in the spread of Christianity in Rome. Constantine’s conversion was influenced by a vision he had before a significant battle, which he interpreted as a sign from the Christian God[1]. He emerged victorious in the battle and subsequently issued the Edict of Milan in 313 AD, granting religious tolerance to Christians and ending the persecutions they faced. Constantine’s conversion and the subsequent shift in Roman policies towards Christianity allowed the faith to flourish openly. Christianity gained imperial favor and protection, leading to the construction of grand basilicas and the establishment of Christian institutions in Rome.

Role of Roman Bishops (Papacy)

The role of the Roman bishops, particularly those who occupied the position of the Bishop of Rome, known as the Pope, was crucial in the spread and establishment of Christianity in Rome. The emergence of the Papacy as a central authority within the Christian Church gave the Bishop of Rome significant influence and authority[1]. As Rome was the political and cultural center of the Roman Empire, the Bishop of Rome became an influential figure in both religious and secular affairs. The Pope provided leadership, guidance, and pastoral care to the growing Christian community in Rome. The Papacy played a key role in doctrinal matters, such as the formulation of creeds and the resolution of theological disputes, which helped shape the development of Christianity in Rome and beyond.

In addition to these key factors and individuals, the devotion and commitment of early Roman Christians cannot be overlooked. The faith and witness of ordinary believers, who lived out their Christian convictions even in the face of persecution, played a significant role in attracting others to the faith and fostering its growth within the city[6].

Was Christianity Spread by Force?

It is essential to acknowledge that isolated incidents of forced conversions or coercion occurred throughout history, but they were not representative of the overall spread of Christianity. The primary means of spreading Christianity involved voluntary conversions, the influence of missionaries, the appeal of Christian teachings, and the personal choices of individuals. Christianity’s growth and influence can be attributed to the transformative power of its message, the dedication of its followers, and its resonance with the spiritual and intellectual needs of people across different societies and cultures[7].

Throughout history, the spread of Christianity has been influenced by various factors, and while instances of forced conversion and coercion have occurred, they do not represent the primary means by which Christianity spread[5].

Early Christian Persecution

During the early years of Christianity, followers of the faith faced severe persecution from the Roman Empire. Emperors such as Nero and Diocletian implemented policies aimed at suppressing Christianity, leading to the martyrdom of many Christians[5]. These persecutions included public executions, imprisonment, confiscation of property, and the destruction of Christian texts and places of worship. Despite the hostile environment, early Christians remained steadfast in their beliefs, and their commitment to the faith played a significant role in its resilience and eventual growth[1]. However, it is important to note that the spread of Christianity during this period was primarily driven by the voluntary conversion of individuals who found solace and hope in the Christian message rather than through forced means.

Forced Conversion During the Crusades

The Crusades, a series of military campaigns initiated by Christian European powers in the 11th to 13th centuries, aimed to reclaim holy sites in the Middle East from Muslim control. While the Crusades were motivated by a combination of religious, economic, and political factors, including the desire to expand Christian influence[4], forced conversion was not the central objective. While there were instances of violence and coercion, particularly during the capture of Jerusalem in the First Crusade, the Crusades were complex endeavors shaped by a range of factors. The primary goals were often territorial gains, political influence, and securing trade routes, rather than widespread forced conversions.

Coercion and the Spanish Inquisition

The Spanish Inquisition, established in the late 15th century, sought to combat heresy and maintain religious orthodoxy within Spain[1]. While the Inquisition did employ coercive measures, including torture and execution, to enforce religious conformity and eliminate perceived threats to Catholic orthodoxy, the primary focus was not the spread of Christianity itself. The Inquisition primarily targeted individuals suspected of heresy, including Jews, Muslims, and non-Catholic Christians[5], aiming to eliminate religious dissent and promote Catholic unity within Spain. It is important to note that the Inquisition was a product of its time, reflecting the religious tensions, political aspirations, and cultural context of 15th-century Spain.

Where Did Christianity Originate From?

The convergence of these factors—Judea’s religious and cultural heritage, the life and ministry of Jesus, the emergence of early Christian communities, and the influences of Jewish tradition and Hellenistic culture—gave rise to Christianity as a distinct and transformative religious movement[5]. From its humble beginnings, Christianity rapidly spread across the Eastern Mediterranean and beyond, transcending cultural and geographic boundaries. The message of Jesus, along with the dedication and missionary efforts of early Christian communities, played a pivotal role in the expansion of the faith.

Understanding the origins of Christianity provides valuable insights into the historical[5] context and foundational beliefs of the faith. The early developments in Judea and the Eastern Mediterranean set the stage for Christianity’s growth and subsequent impact on the world, shaping the course of religious and cultural history.

Roots in Judea and Ancient Israel

Christianity traces its roots to the region of Judea, which was part of the ancient Israelite kingdom. Located in the Eastern Mediterranean, Judea was a land deeply influenced by Jewish religious and cultural practices[1]. The ancient Israelites, under the covenant with God, worshipped Yahweh as the one true God and adhered to the laws and teachings of the Hebrew scriptures. The theological and cultural foundation established by Judaism laid the groundwork for the emergence of Christianity.

READ MORE: Ancient Civilizations Timeline: The Complete List from Aboriginals to Incans

Life and Ministry of Jesus

The life and ministry of Jesus of Nazareth serve as the cornerstone of Christianity. Born in Bethlehem and raised in Nazareth, Jesus embarked on a transformative mission in his early thirties, preaching a message of love, compassion, and forgiveness. He performed miracles, taught in parables, and challenged religious and societal norms of the time. Jesus’ teachings focused on the arrival of the Kingdom of God, the importance of faith, and the need for repentance. His life, sacrificial death on the cross, and resurrection became the central events that shaped the core beliefs of Christianity[6].

Early Christian Communities in the Eastern Mediterranean

Following the death and resurrection of Jesus, early Christian communities began to form in the Eastern Mediterranean region. These communities initially comprised Jewish converts who recognized Jesus as the long-awaited Messiah promised in Jewish scriptures. These early Christians continued to observe Jewish customs while embracing the teachings of Jesus[2]. The Jerusalem Church, led by Jesus’ disciples and later James, the brother of Jesus, played a crucial role in nurturing and expanding these early Christian communities. As the movement grew, it spread to cities such as Antioch, Alexandria, and Ephesus, establishing a network of communities connected by their faith in Jesus Christ[2].

READ MORE: The Lighthouse of Alexandria: One of the Seven Wonders

Influence of Jewish Tradition and Hellenistic Culture

The origins of Christianity were shaped by both Jewish tradition and the broader Hellenistic culture prevalent in the Eastern Mediterranean during that time. Jewish tradition provided the religious and cultural context within which Jesus and his followers operated. The Hebrew scriptures, including the Torah, Psalms, and Prophets[5], were foundational texts that Jesus drew upon to articulate his teachings. Furthermore, the concept of the Messiah, deeply rooted in Jewish tradition, became central to the Christian belief in Jesus as the Anointed One. On the other hand, the Hellenistic culture, infused with the Greek language, philosophy, and thought, had a significant influence on the early Christian movement. The Greek language became the lingua franca of the Eastern Mediterranean[6], facilitating the spread of Christian ideas and enabling communication among diverse cultural groups.

Looking Forward

The study of Christianity’s history and its spread provides us with valuable insights into the development and impact of one of the world’s major religions. It highlights the transformative power of faith, the role of influential leaders and communities, and the interplay between religion, culture, and politics. Understanding the origins and growth of Christianity helps us appreciate the diversity of religious beliefs and traditions across different regions and provides a historical context for interfaith dialogue and cooperation in today’s globalized world.

Furthermore, the historical journey of Christianity reminds us of the importance of religious freedom, tolerance, and respect for diverse beliefs. It teaches us to appreciate the contributions of various cultures and traditions in shaping our societies. Christianity’s message of love, compassion, and social justice continues to inspire individuals and communities worldwide to work towards a more just and equitable world.

In our present world, the knowledge gained from studying the rise and spread of Christianity encourages us to foster understanding and dialogue among different religious and cultural groups. It reminds us of the need for empathy, compassion, and mutual respect in our interactions with others. By learning from the historical experiences of Christianity, we can strive for peaceful coexistence, promote interfaith harmony, and work towards common goals of human dignity, social justice, and global solidarity.

- Bartlett, R. (2010). The Making of Europe: Conquest, Colonization, and Cultural Change, 950-1350. Penguin Books.

- Chadwick, H. (1993). The Early Church. Penguin Books.

- Duffy, E. (2006). Saints and Sinners: A History of the Popes. Yale University Press.

- Gonzalez, J. L. (2010). The Story of Christianity: Volume 1: The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation. HarperOne.

- MacCulloch, D. (2010). Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years. Penguin Books.

- Noll, M. A. (2013). Turning Points: Decisive Moments in the History of Christianity. Baker Academic.

- Pelikan, J. (2013). The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine, Vol. 1: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600). University of Chicago Press.

How to Cite this Article

There are three different ways you can cite this article.

1. To cite this article in an academic-style article or paper , use:

<a href=" https://historycooperative.org/how-did-christianity-spread/ ">How Did Christianity Spread: Origins, Expansion, and Impact </a>

1 thought on “How Did Christianity Spread: Origins, Expansion, and Impact ”

What is the impact of Christianity to Mankind? Is it positive or negative?

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

The Growth of Christianity in the Roman Empire

Colin Ricketts

09 aug 2018.

This educational video is a visual version of this article and presented by Artificial Intelligence (AI). Please see our AI ethics and diversity policy for more information on how we use AI and select presenters on our website.

The Rome of today is no longer the centre of a great empire. It is still globally important though, with more than one billion people looking to it as the centre of the Roman Catholic faith.

It’s not a coincidence that the capital of the Roman Empire became the centre of Roman Catholicism; Rome’s eventual adoption of Christianity, after centuries of indifference and periodic persecution, gave the new faith enormous reach.

Saint Peter was killed in Nero’s persecution of Christians following the Great Fire of 64 AD ; but by 319 AD, Emperor Constantine was building the church that was to become St Peter’s Basilica over his grave.

Religion in Rome

Since its foundation, Ancient Rome was a deeply religious society and religious and political office often went hand in hand. Julius Caesar was Pontifex Maximums, the highest priest, before he was elected as Consul, the highest Republican political role.

The Romans worshipped a large collection of gods , some of them borrowed from the Ancient Greeks, and their capital was full of temples where by sacrifice, ritual and festival the favour of these deities was sought.

Wedding of Zeus and Hera on an antique fresco from Pompeii. Image credit: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Julius Caesar approached god-like status at the height of his powers and was deified after his death. His successor Augustus encouraged this practice. And although this apotheosis to divine status happened after death, the Emperor became a god to many Romans, an idea Christians were to later find highly offensive.

As Rome grew it encountered new religions, tolerating most and incorporating some into Roman life. Some, however, were singled out for persecution, usually for their ‘un-Roman’ nature. The cult of Bacchus, a Roman incarnation of the Greek god of wine, was repressed for its supposed orgies, and the Celtic Druids were all but wiped out by the Roman military, reportedly for their human sacrifices.

Jews were also persecuted, particularly after Rome’s long and bloody conquest of Judea.

Christianity in the Empire

Christianity was born in the Roman Empire. Jesus Christ was executed by Roman authorities in Jerusalem, a city in a Roman province.

His disciples set about spreading the word of this new religion with remarkable success in the crowded cities of the Empire.

Early persecutions of Christians were probably carried out at the whim of provincial governors and there was also occasional mob violence. Christians’ refusal to sacrifice to Roman gods could be seen as a cause of bad luck for a community, who might petition for official action.

The first – and most famous – great persecution was the work of Emperor Nero . Nero was already unpopular by the time of the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD. With rumours that the Emperor himself was behind the fire circulating, Nero picked on a convenient scapegoat and many Christians were arrested and executed.

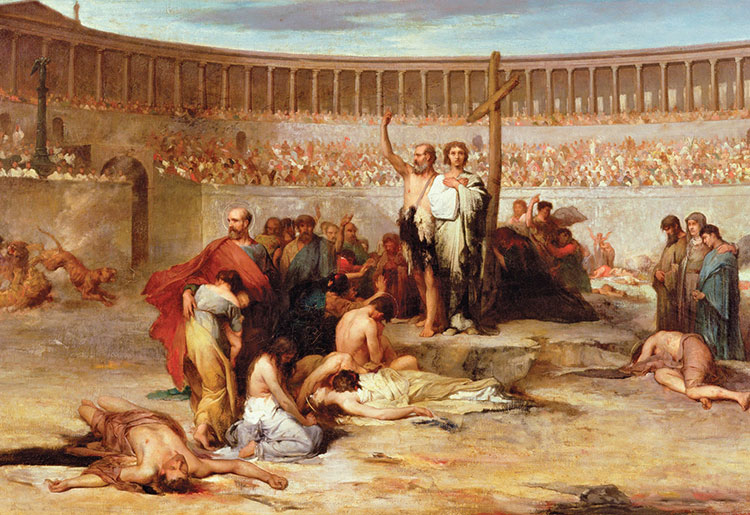

‘Triumph of Faith’ by Eugene Thirion (19th century) depicts Christian martyrs in the time of Nero. Image credit: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

It wasn’t until the reign of the Emperor Decius in 250 AD that Christians were again put under Empire-wide official sanction. Decius ordered every inhabitant of the Empire to make a sacrifice in front of Roman officials. The edict may not have had specific anti-Christian intent, but many Christians did refuse to go through the ritual and were tortured and killed as a result. The law was repealed in 261 AD.

Diocletian, the head of the four-man Tetrarch, instituted similar persecutions in a series of edicts from 303 AD, calls that were enforced in the Eastern Empire with particular enthusiasm.

The ‘conversion’

The apparent ‘conversion’ to Christianity of Constantine, Diocletian’s immediate successor in the Western Empire, is seen as the great turning point for Christianity in the Empire.

Persecution had ended before Constantine’s reported miraculous vision and adoption of the cross at the Battle of Milvian Bridge in 312 AD. He did, however, issue the Edict of Milan in 313, allowing Christians and Romans of all faiths ‘liberty to follow that mode of religion which to each of them appeared best.’

Christians were allowed to take part in Roman civic life and Constantine’s new eastern capital, Constantinople, contained Christian churches alongside pagan temples.

Constantine’s vision and the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in a 9th-century Byzantine manuscript. Image credit: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The extent of Constantine’s conversion is still not clear. He gave money and land to the Christians and founded churches himself, but also patronised other religions. He wrote to Christians to tell them that he owed his success to their faith, but he remained Pontifex Maximus until his death. His deathbed baptism by Pope Sylvester is only recorded by Christian writers long after the event.

After Constantine, Emperors either tolerated or embraced Christianity, which continued to grow in popularity, until in 380 AD Emperor Theodosius I made it the official state religion of the Roman Empire.

Theodosius’ Edict of Thessalonica was designed as the final word on controversies within the early church. He – along with his joint rulers Gratian, and Valentinian II – set in stone the idea of an equal Holy Trinity of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Those ‘foolish madmen’ who did not accept this new orthodoxy – as many Christians didn’t – were to be punished as the Emperor saw fit.

The old pagan religions were now suppressed and sometimes persecuted.

Rome was in decline, but becoming part of its fabric was still a massive boost for this growing religion, now called the Catholic Church. Many of the Barbarians who are credited with ending the Empire in fact wanted nothing more than to be Roman, which increasingly came to mean converting to Christianity.

While the Emperors of Rome would have their day, some of the Empire’s strengths were to survive in a church led by the Bishop of Rome.

You May Also Like

The Peasants’ Revolt: Rise of the Rebels

10 Myths About Winston Churchill

Medusa: What Was a Gorgon?

10 Facts About the Battle of Shrewsbury

5 of Our Top Podcasts About the Norman Conquest of 1066

How Did 3 People Seemingly Escape From Alcatraz?

5 of Our Top Documentaries About the Norman Conquest of 1066

1848: The Year of Revolutions

What Prompted the Boston Tea Party?

15 Quotes by Nelson Mandela

The History of Advent

The Princes in the Tower: Solving History’s Greatest Cold Case

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

World history

Course: world history > unit 2.

- Early Christianity

- The spread of Christianity

Christianity in the Roman Empire

- The Council of Nicaea

- Judaism and Christianity key terms

- Context: Judaism and Christianity

- Early Judaism and Early Christianity

- Christianity developed in the province of Judea out of Jewish tradition in the first century CE, spread through the Roman Empire, and eventually became its official religion

- Christianity was influenced by the historical contexts in which it developed

Beginnings of Christianity

Christianity and rome.

- (Choice A) Christianity was fully formed as a new religion at this time A Christianity was fully formed as a new religion at this time

- (Choice B) Christianity was still not clearly defined at this time B Christianity was still not clearly defined at this time

- (Choice C) Christianity was well-established as a major religion in the Roman Empire C Christianity was well-established as a major religion in the Roman Empire

Rome becomes Christian

Want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

8. The expansion of Christianity

From the book rome in late antiquity.

- Bertrand Lançon

- X / Twitter

Supplementary Materials

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

Chapters in this book (27)

Farewell to Shadowlands

reflections on the love that changes everything

The Expansion of Christianity in the Roman Empire

(This essay was written for History 201.6, University of Saskatchewan, 1 April 1999)

Why did Christianity spread throughout the Roman Empire? This question could be answered in one of two ways. First, it could be shown that the Roman Empire provided Christianity with a context in which it could readily spread. [1] However, that same context existed for the state religion, mystery religions and quasi-religious philosophies that existed in Rome during the time of Christian expansion. Why, then, did Christianity expand within the Empire against these other religions to the point where, at the beginning of the fourth century, about ten per cent of the total population and perhaps fifty per cent of the population in Asia Minor were Christian [2] ? To answer that question, this essay will be looking at the period from the first century AD up to Constantine’s victory at the Milvian Bridge in AD 312.

Constantine’s conversion, which allow Christianity to leap-frog in status over the pagan religions, will not be a part of the consideration. Prior to Constantine’s conversion, Christian had already become a well-organised unified force without support or toleration from the state. This essay will be focused on why Christianity was able to do that. Also, the persecution of the Christians by the state will not be considered in this essay. The impact of the persecutions and the resulting martyrdoms is a subject worthy of its own essay and sufficient space is not available within this essay to properly discuss it.

Within the range established, this essay will look at various ancient sources such as the Bible, Apuleius of Madauros, Lucretius, Seneca the Younger, Eusebius and Athanasius, as well as several works of modern scholarship on the subject to support its conclusion. In this way, it will be shown that Christianity spread throughout the Roman Empire because of three reasons. First, because it developed out of Judaism, it had historical credibility and it was able to use the Jewish Greek Scriptures and the network of Diasporic Judaism for its own benefit in its missionary work. Second, Christianity appealed to Romans because it provided a genuine religious alternative that offered intellectual content, a high standard of morality, a genuine social concern, and universal salvation for all people of all races and all classes. Third, Christianity developed an strong effective and united institutional organisation that was able to foster the Christian missionary programs, consolidate the gains made and withstand the fierce persecutions periodically unleashed by the state.

Christianity arose in a Jewish religious and social context [3] and was led, in its early years, entirely by Jews. This Jewish heritage of Christianity gave it a solid foundation of history, morality and religious literature, which it built upon, modified, and made its own. [4] These Jewish roots were more than a useful foundation, however, for Christianity essentially claimed to be the culmination of Judaism. Peter’s confession that Jesus is “the Christ the Son of the Living God” [5] encapsulates this claim. Thus, the essence of Christianity, as it relates to Judaism, is that Jesus is the Messiah promised by the Jewish God.

The Jewish heritage of Christianity was important for three reasons. First, Christianity was able to show non-believers that it, like the other religions of Rome, had its own history and literature. [6] The connection between Christianity and Judaism is genuine, for the early followers of Jesus did not think of themselves as adherents to a new religion, but as faithful Jews who believed in the Messiah promised by the Jewish God. Many of them continued to observe the Jewish practices of temple worship [7] and dietary laws. [8] Also, after Pentecost, the believers would often meet inside the temple courtyard. [9] Thus the claim that Christianity arose out of Judaism is authentic and that gave Christians the right to claim Judaic history and Scriptures as their own.

Second, the Judaism offered Christianity an existing network throughout the Roman Empire and an existing pool of knowledgeable potential converts to proselytise among. Because it was their scriptures to begin with, the Jews were very knowledgeable about the content of the Jewish Scriptures, and they placed a very heavy emphasis on that content. [10] The Jews already knew the history. The early Christians only had to convince them that Jesus was the fulfilment of that history. Also, because Jews lived throughout the Roman Empire, the early Christian missionaries had an immediate point of contact in each town that they stopped in. Time after time, Paul and the missionaries who would accompany him would go first to the local synagogue to reason “with the Jews and the God-fearing Greeks. [11] “ [12] The missionaries used the Jewish Scriptures to show how the coming of Jesus and his life were foretold in the Scriptures and how he fulfilled the promises made in those Scriptures. [13]

Third, Christianity was able to extensively use the Greek version of the Jewish Scriptures, called the Septuagint, in its missionary work among Greek-speaking Jews and Gentiles. During previous centuries, many Jews were dispersed throughout the Greek-speaking world of the Hellenistic kingdoms, which later became a part of the Roman Empire. Over time, many of these Jews learned to speak the international language of Greek and lost the ability to speak and read Hebrew. Therefore, during the third and second centuries BC, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures was developed. This Scripture, the Septuagint was used extensively by the Christians and considered the authoritative version of the Old Testament until the fourth century when it was supplanted by the Hebrew translation of the Old Testament. [14]

Christianity was accessible to the Romans because of its universality. Over time, because of Jesus’ teachings, a vision received by Peter, and, especially, through the experience and effort of Paul, Christianity was opened up to all people. In response to the faith of a Roman centurion, Jesus declares,

I tell you the truth, I have not found anyone in Israel with such great faith. I say to you that many will come from the east and the west, and will take their places at the feast with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven. But the subjects of the kingdom will be thrown outside, into the darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth. [15]

Jesus also debunked the Jewish dietary laws by saying, “What goes into a man’s mouth does not make him ‘unclean,’ but what comes out of his mouth, that is what makes him ‘unclean.'” [16] After Jesus’ death and resurrection, Peter receives a vision in which God instructs him to eat unclean animals. Peter protests but God says, “Do not call anything impure that God has made clean.” [17] Right after the vision, Peter receives an invitation from a centurion named Cornelius to come and talk to him. Peter understands the vision to mean that he is not to consider any other human unclean (but it also counters the Jewish dietary laws). Peter and the other Jews are amazed when the Holy Spirit comes upon the Gentile believers just as it did upon the Jewish believers. They take this as confirmation from God that salvation through Jesus Christ is meant for both Jew and Gentile. [18] In Pisidian Antioch, [19] Corinth, [20] and Ephesus, [21] Paul preached the Christian message to the Jews first. However, when he encountered obstinacy and abuse from the Jews, he turned to preach the message to the Gentiles, and many of them believed. [22] The issue finally came to a head when some Jewish Christians were insisting, in Antioch, that all Gentile believers be circumcised and follow the Mosaic Law. At a council of the apostles and church elders in Jerusalem, it was decided that the Gentile converts should only be asked to refrain from eating meat from strangled animals or from animals offered to idols, avoid blood, and avoid sexual immorality. [23] This decision is monumental for it opens the new faith to all people, whether Jew or Gentile. In this way, Christianity became open, accessible and available to all people of all race, class, gender and social status. As Paul said in his letter to the Galatians, “You are all sons of God through faith in Christ Jesus, for all of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is neither Jew no Greek, slave nor free, male or female, for you are all one in Christ, then you are Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise.” [24]

The polytheistic and syncretic religious scene in Rome at this time contrasted sharply with the monotheism and exclusiveness of Judaism and Christianity. The state religion purported a pantheon of anthropomorphic gods and goddesses which required the honour and attention of all the citizens of the state to continue bestowing peace, prosperity and good fortune upon the state. Failure to give honour to the gods would bring swift retribution. [25]

However, in spite of the fact that the state religion was the official and public sponsored religion, on its own, it failed to fulfil the religious needs of the Roman people. Joscelyn Godwin describes the state religion as “a solemn but unmystical affair, respectable yet undemanding of personal enthusiasm or spiritual effort…. it lacked any conception of the Absolute, had no real Mother Goddess, and held out no hopes for an after-life.” [26] Furthermore, the state religion was seen by some as merely superstition implemented “for the sake of the common people,” [27] and maintained for its “great political usefulness.” [28] However, because of the syncretic nature of Rome, it would tolerate and often adopt any religion that was willing to compromise with the state religion. [29] Therefore, mystery religions from the east were able to come to Rome and flourish. [30]

The plethora of mystery religions that came to Rome from the East in the two centuries before Christ helped to fill the religious void left by the state religion. Among them were Cybele, or Magna Mater, who came from Asia Minor in 205 BC, [31] Isis, who came to Italy from Egypt in the second century BC, and Mithras, who may have been introduced to Rome by Cilician pirates c. 67 BC or earlier. [32] Mystery religions differ from the state religion in that they are voluntary associations centred upon personal beliefs that offer personal benefit or salvation by approaching the divine. [33] Cybele is a powerful, violent mother goddess who will deflect her fury from her petitioning devotees. [34] But she is also a source of renewal in this life and she is associated with some sort of life after death. In the taurobolium , the participant is reborn with the effects lasting twenty years or, sometimes, for eternity. [35] To what extent Cybele offers life after death is not clear from the evidence. Violets arising from the blood of the dying Attis and Jupiter’s agreeing to allow the dead Attis to persist in a state of suspended animation indicate some sort of life after death. [36] However, by the fourth century AD there is evidence that the resurrection of Attis is celebrated. [37] Isis, who was thought to rule over all of nature and all the gods of heaven and hell, was considered a Redeemer of humanity who protected people on sea and land, and controlled the harmful twists of Fate. [38] As the ruler over both this life and the next and she was able to bestow upon her devotees an extension of this life and the opportunity to worship her in a life after death. [39] Similarly, devotees of Mithras thought that, through Mithras, they could be “born again” to a glorious immortal life after death. [40]

The mystery religions contribute to the spread of Christianity by serving as the theological shock troops for the Christian faith. [41] Not only did they preveniently introduce the concepts of a personal, voluntary religion that could bestow life after death, but there were other similarities as well. The cults of both Cybele and Isis practised rituals which were very similar to baptism. [42] Cybele and Mithras emphasise the saving power of shed blood. [43] Both Isis [44] and Cybele [45] are mother goddesses similar to Mary the theotokos (qeotokoj) –the god bearer. [46] Through Mithraism one could ascend into heaven [47] and the idea of abstinence was introduced to the west by the monks of Isis and the eunuch priests of Cybele. [48]

A mystery religion also played a role in the final triumph of Christianity. Mithras is associated with Helios the Sun god, [49] and the cult had a wide following in the Roman legions. [50] Constantine was a soldier and an emperor and, prior to his conversion, a devotee of the Unconquered Sun. [51] The day before the decisive victory against Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge in October of AD 312, Constantine “saw with his own eyes the trophy of a cross of light in the heavens, above the sun, and an inscription, CONQUER BY THIS attached to it.” [52] After becoming sole emperor, Constantine made Sunday as a special day set aside for worship. [53] This edict would have been welcomed by both Christians and Mithraites for both considered Sunday to be a special day of worship. [54] The genuineness and completeness of Constantine’s ‘conversion’ is a debatable subject that will not be discussed in this essay. There is no doubt that he favoured Christianity [55] and placed restrictions upon pagan religions [56] in Rome, but it has been speculated that Constantine may have seen no disjunction between the Unconquered Sun and the Unconquered Son–Jesus Christ. [57] It seems reasonable to believe that the Mithraic mystery cult played a preparatory role of some kind in the development of Constantine’s attitude towards Christianity and that attitude was decisive in the Christian conquest of the Roman Empire.

Though there are some remarkable similarities between Christianity and the mystery religions, it would be a mistake to classify Christianity merely as a mystery religion or a synthetic imitation of those religions, for there are very significant differences. [58] First, mystery religions cost money to join [59] whereas Christianity was accessible to both rich and poor, slave and free. [60] The second major difference was institutional organisation. Christianity, intent on spreading the gospel to as many people as possible, created a institutional structure to consolidate the gains that were made and facilitate the continued missionary work. [61] The mystery religions, on the other hand, were more concerned with keeping their proprietary knowledge secret and, as a result, they had no interest in developing any kind of formal network between individual centres of worship. [62] As a result, when the mystery religions lost state support and were declared illegal in the fourth century, they soon disappeared. [63] The third major difference was that while Christianity claimed to be the only way to salvation, [64] the mystery religions were very tolerant of their followers participating in other religions and cults. [65]

This exclusiveness of Christianity is very important for it meant rejection of the state religion and thus a denial by the state of any tolerance or support toward Christianity. This forced Christianity to create its own organisation to do its own work of spreading the gospel. Already in the first century, there are indications of a form of organisation with elders and deacons. [66] This developed into an episcopal style of organisation which was so effective that it was soon adapted by Christian communities throughout the Empire. [67] Under Cyprian, who was elected Bishop of Carthage circa AD 246, the episcopacy took on a divine nature, for Cyprian saw the episcopacy as the preserver of the sanctity and unity of the church. The church became like a “great federative republic” [68] that was “a standing challenge to the authority of the state and its gods.” [69] This organisation proved to be very resilient, so much so that the longest, most pervasive, and fiercest persecution that the Roman Empire could muster against it was unable to destroy it. The realisation of this fact and the parallel realisation of the potential of Christianity as a unifying force within the Empire that would be loyal to the emperor may have contributed to Constantine’s acceptance of Christianity. [70]

This exclusiveness is also very important because it meant that only when a Roman was considering Christianity as an alternative to Rome’s syncretic conglomerate of polytheistic religion did he or she have a genuine religious option. To understand what is meant by this statement, one will need to take a close look at the work of the renowned American pragmatic philosopher, William James (1842-1910). In The Will to Believe , he writes,

Let us give the name of hypothesis to anything that may be proposed to our belief; and… let us speak of any hypothesis as either live or dead . A live hypothesis is one which appeals as a real possibility to him to who it is proposed [and a dead hypothesis has no such appeal]…

Next, let us call the decision between two hypotheses an option . Options may be of several kinds. They may be–1, living or dead ; 2, forced or avoidable ; 3, momentous or trivial ; and for our purposes we may call an option a genuine option when it is of the forced, living, and momentous kind.

1. A living option is one in which both hypotheses are live ones…. each hypothesis makes some appeal, however small, to your belief.

2. Next, if I say to you; “Choose between going out with your umbrella or without it,” I do not offer you a genuine option, for it is not forced. You can easily avoid it by not going out at all…. But if I say, “Either accept this truth or go without it,” I put on you a forced option, for there is no standing place outside of the alternative. Every dilemma based on a complete logical disjunction, with no possibility of not choosing, is an option of this forced kind.

3. Finally, if I were Dr. Nansen [71] and proposed to you to join my North Pole expedition, your option would be momentous; for this would probably be your only similar opportunity, and your choice now would either exclude you from the North Pole sort of immortality altogether or put at least the chance of it into your hands. He who refuses to embrace a unique opportunity loses the prize as surely as if he tried and failed. Per contra, the option is trivial when the opportunity is not unique, when the stake is insignificant, or when the decision is reversible if it later prove unwise. Such trivial options abound in the scientific life. A chemist finds an hypothesis live enough to spend a year in its verification: he believes in it to that extent. But if his experiments prove inconclusive either way, he is quit for his loss of time, no vital harm being done. [72]

Consider the religious decision-making process of a second century Roman in light of James’ paradigm. She is participating in the state religion but she is considering joining a mystery cult. Both of her two hypotheses, either joining a mystery cult or not, are live for her, therefore she has a living option. Her option is a momentous one for the mystery cult offers an opportunity for personal salvation, life after death and immortality. However, her option is not a forced option because there is not a complete disjunction between the state religion and the mystery religion. Even if she were to join the mystery religion, she would continue to participate in the state religion. The mystery religion is tolerated in Rome only because it compromises with the state religion. It cannot deny, condemn or distance itself in any way from the state religion. Her choice is not one or the other , it is one or both . Because Christianity is the only universal religion in the Roman world which claims an exclusive way of salvation, it is the only hypothesis which would create a forced option. Therefore, only when considering the Roman state religion (with or without a mystery religion) versus Christianity does a Roman have a genuine religious option.

The only thing that a mystery cult can do, within the Roman religious system, to portray itself as offering something unique and desirable is to offer a secret enhancement of the state religion. The mystery religions are offering an enhancement of, not an alternative to, the state religion. If the enhancement of one mystery religion becomes publicly available, then that mystery religion is no longer offering an enhancement. Therefore, a mystery religion has to jealously guard the secrecy of its enhancement in order to maintain its existence. [73]

In contrast to the mystery religions, philosophy did offer an alternative to Roman religion, the way of Truth. For philosophers, Truth is the end and reason is the means to that end. After coming to an understanding of the Truth, living in accordance with the Truth is the personal goal of the philosopher. It is important to consider philosophy, when studying the reasons for the Christianity’s success in Rome, for three reasons. First, two philosophies, Stoicism and Epicureanism, both had a major impact upon Roman society and each had something to say with respect to religion. [74] Second, pagan philosophy challenged Christianity to develop intellectual and philosophical content. [75] This asset allowed Christianity to appeal to the educated elite [76] by offering its own way of Truth. Third, because Christianity, in its own defence, used tools and concepts developed by pagan philosophy, the prior use of such concepts by pagan philosophy served as significant preparatory work for the new faith. [77]

Epicurean thought sought to show, through scientific explanation, that things were matter, including the soul. Upon death, the body and soul decay and the atoms that make up the body and soul disperse. [78] Therefore, personal existence ceases upon death. All events are due to natural processes and the gods play no part in the affairs of humans. The most important thing was the peace of mind that came from partaking only of the minimum of life’s simple necessities. [79]

Stoicism also maintained that everything was matter. However, instead of Epicurean atoms, Stoics believed that everything was one substance which ranged in refinement from the coarseness of solid material, like rocks, wood, and bodies, to the more refined state of vapour and ether. The most highly refined form of the one substance which was everything is spirit, or soul, and it is found embodied in humans and pervading throughout the universe, actively governing through its rational abilities. This universal spirit, called Reason, or Logos, functioned as the plan of the universe, but was not the planner. The individual was a microcosm of the universe, with his body relating to the solid material of the universe and his material soul relating to the material soul of the universe. Upon death, his soul would be reunited with the universal Reason, but prior to that the body was considered a prison of the soul. The greatest good for an individual was to live his life in harmony with the universal Reason, or Logos, by allowing it, and not emotions, to govern his life. [80]

In the first chapter of his Gospel, John refers to Jesus Christ as the Word, or Logos. He writes,

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was with God in the beginning.

Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made. In him was life, and that life was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness, but the darkness has not understood it….

The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the One and Only, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth. [81]

Using the gospel of John, Greek philosophy like Stoicism, and the work of Philo, [82] Christian philosophers, such as Athanasius, developed their own concept of the Logos that centred upon the person of Jesus Christ. In the Christian philosophy of the second to fourth centuries, God created the world and all that is in it out of nothing through the Logos, His Son, Jesus Christ. In this way, man was also created. However, man was unique in the creation for he was given a small portion of the Logos so that he would have Reason. [83] God had wanted all of humanity to remain immortal, but humans chose to disobey God and, as a result, all humanity suffers from illness and death. Wishing to restore humanity, the Logos came to earth and took on the human form of Jesus of Nazareth. [84] The death he suffered was a universal replacement for the deaths of all of humanity, so humanity, being indwelt with the Son of God because of its likeness to him, could once again have immortal life. [85]

On the question of truth, apologists such as Justin Martyr argued that Christianity, through the Logos, the Son of God, possessed the truth. Whatever truth non-Christian philosophers, poets and prose writers know, they know through the use of the divine Logos. However, whatever truth they know is incomplete, for they only possess the “seed” of the Logos. Christians, on the other hand, know the truth more fully, for they know, love and worship the revealed Logos, Jesus Christ. [86]

For the purposes of this essay, it is not necessary to show that Christianity bested all competitors in the realm of philosophy. The Christian apologists of the second, third and fourth centuries AD participated in this field, not to establish philosophical superiority, but, just as with contemporary apologists, to provide a reasoned defence for the Christian faith [87] and to show that such beliefs are reasonable. [88] The eventual triumph of Christianity within the Empire is evidence of the early apologists’ success.

In the realm of religion, Christianity clearly had an advantage over the pagan philosophies. In contrast to the cessation of existence upon death as found in Epicureanism, Christianity offered the hope of life after death. In contrast to Stoicism’s concept of a cold emotionless Divine Logos, Christianity offered a God so loving that he was willing to suffer and die for all people. In contrast to Stoicism’s denial of emotion, Christianity had agape feasts, joy and happiness. In contrast to Stoicism’s vague concept of the human soul reuniting with the Divine Reason, Christianity offered a glorious personal afterlife with God and the believers who have gone on before hand. The combination of intellectual content and personal salvation made Christianity a formidable force to its competitors.

A contributing factor to the attractiveness of Christianity in Rome was its high moral standards based upon the teachings of Jesus Christ. With respect to the Mosaic Law and the Words of the Prophets of Judaism, Jesus said that did not come to abolish them, “but to fulfill them.” [89] In terms of the Words of the Prophets, Jesus’ words are understood as pointing to himself as the fulfilment of the promises of a coming Messiah. In terms of the Mosaic Law, Jesus’ words, in light of his teaching, can be understood to mean that he has come to show how the Mosaic Law, in its fullness and completeness, is to be properly understood. In other words, it is not sufficient to keep the letter of the law, the law demands one must keep the higher standard of the spirit of the law. [90] In the Sermon on the Mount, found in the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus reveals the new morality,

You have heard that is was said to the people long ago, ‘Do not murder,’…. But I tell you that anyone who is angry with his brother will be subject to judgement…. You have heard that it was said, ‘Do not commit adultery.’ But I tell you that anyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart…. It has been said, ‘Anyone who divorces his wife must give her a certificate of divorce.’ But I tell you that anyone who divorces his wife, except for marital unfaithfulness, causes her to become an adulteress, and anyone who marries the divorced woman commits adultery…. You have heard that it was said, ‘Eye for eye, and tooth for tooth,’ But I tell you, Do not resist and evil person. If someone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also. You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor and hate your enemy,’ But I tell you; Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be sons of your Father in heaven. [91]