Essays About Reading: 5 Examples And Topic Ideas

As a writer, you love to read and talk to others about reading books. Check out some examples of essays about reading and topic ideas for your essay.

Many people fall in love with good books at an early age, as experiencing the joy of reading can help transport a child’s imagination to new places. Reading isn’t just for fun, of course—the importance of reading has been shown time and again in educational research studies.

If you love to sit down with a good book, you likely want to share your love of reading with others. Reading can offer a new perspective and transport readers to different worlds, whether you’re into autobiographies, books about positive thinking, or stories that share life lessons.

When explaining your love of reading to others, it’s important to let your passion shine through in your writing. Try not to take a negative view of people who don’t enjoy reading, as reading and writing skills are tougher for some people than others.

Talk about the positive effects of reading and how it’s positively benefitted your life. Offer helpful tips on how people can learn to enjoy reading, even if it’s something that they’ve struggled with for a long time. Remember, your goal when writing essays about reading is to make others interested in exploring the world of books as a source of knowledge and entertainment.

Now, let’s explore some popular essays on reading to help get you inspired and some topics that you can use as a starting point for your essay about how books have positively impacted your life.

For help with your essays, check out our round-up of the best essay checkers

Examples Of Essays About Reading

- 1. The Book That Changed My Life By The New York Times

- 2. I Read 150+ Books in 2 Years. Here’s How It Changed My Life By Anangsha Alammyan

- 3. How My Diagnosis Improved My College Experience By Blair Kenney

4. How ‘The Phantom Tollbooth’ Saved Me By Isaac Fitzgerald

5. catcher in the rye: that time a banned book changed my life by pat kelly, topic ideas for essays about reading, 1. how can a high school student improve their reading skills, 2. what’s the best piece of literature ever written, 3. how reading books from authors of varied backgrounds can provide a different perspective, 4. challenging your point of view: how reading essays you disagree with can provide a new perspective, 1. the book that changed my life by the new york times.

“My error the first time around was to read “Middlemarch” as one would a typical novel. But “Middlemarch” isn’t really about plot and dialogue. It’s all about character, as mediated through the wise and compassionate (but sharply astute) voice of the omniscient narrator. The book shows us that we cannot live without other people and that we cannot live with other people unless we recognize their flaws and foibles in ourselves.” The New York Times

In this collection of reader essays, people share the books that have shaped how they see the world and live their lives. Talking about a life-changing piece of literature can offer a new perspective to people who tend to shy away from reading and can encourage others to pick up your favorite book.

2. I Read 150+ Books in 2 Years. Here’s How It Changed My Life By Anangsha Alammyan

“Consistent reading helps you develop your analytical thinking skills over time. It stimulates your brain and allows you to think in new ways. When you are actively engaged in what you’re reading, you would be able to ask better questions, look at things from a different perspective, identify patterns and make connections.” Anangsha Alammyan

Alammyan shares how she got away from habits that weren’t serving her life (such as scrolling on social media) and instead turned her attention to focus on reading. She shares how she changed her schedule and time management processes to allow herself to devote more time to reading, and she also shares the many ways that she benefited from spending more time on her Kindle and less time on her phone.

3. How My Diagnosis Improved My College Experience By Blair Kenney

“When my learning specialist convinced me that I was an intelligent person with a reading disorder, I gradually stopped hiding from what I was most afraid of—the belief that I was a person of mediocre intelligence with overambitious goals for herself. As I slowly let go of this fear, I became much more aware of my learning issues. For the first time, I felt that I could dig below the surface of my unhappiness in school without being ashamed of what I might find.” Blair Kenney

Reading does not come easily to everyone, and dyslexia can make it especially difficult for a person to process words. In this essay, Kenney shares her experience of being diagnosed with dyslexia during her sophomore year of college at Yale. She gave herself more patience, grew in her confidence, and developed techniques that worked to improve her reading and processing skills.

“I took that book home to finish reading it. I’d sit somewhat uncomfortably in a tree or against a stone wall or, more often than not, in my sparsely decorated bedroom with the door closed as my mother had hushed arguments with my father on the phone. There were many things in the book that went over my head during my first time reading it. But a land left with neither Rhyme nor Reason, as I listened to my parents fight, that I understood.” Isaac Fitzgerald

Books can transport a reader to another world. In this essay, Fitzgerald explains how Norton Juster’s novel allowed him to escape a difficult time in his childhood through the magic of his imagination. Writing about a book that had a significant impact on your childhood can help you form an instant connection with your reader, as many people hold a childhood literature favorite near and dear to their hearts.

“From the first paragraph my mind was blown wide open. It not only changed my whole perspective on what literature could be, it changed the way I looked at myself in relation to the world. This was heavy stuff. Of the countless books I had read up to this point, even the ones written in first person, none of them felt like they were speaking directly to me. Not really anyway.” Pat Kelly

Many readers have had the experience of feeling like a book was written specifically for them, and in this essay, Kelly shares that experience with J.D. Salinger’s classic American novel. Writing about a book that felt like it was written specifically for you can give you the chance to share what was happening in your life when you read the book and the lasting impact that the book had on you as a person.

There are several topic options to choose from when you’re writing about reading. You may want to write about how literature you love has changed your life or how others can develop their reading skills to derive similar pleasure from reading.

Middle and high school students who struggle with reading can feel discouraged when, despite their best efforts, their skills do not improve. Research the latest educational techniques for boosting reading skills in high school students (the research often changes) and offer concrete tips (such as using active reading skills) to help students grow.

It’s an excellent persuasive essay topic; it’s fun to write about the piece of literature you believe to be the greatest of all time. Of course, much of this topic is a matter of opinion, and it’s impossible to prove that one piece of literature is “better” than another. Write your essay about how the piece of literature you consider the best positive affected your life and discuss how it’s impacted the world of literature in general.

The world is full of many perspectives and points of view, and it can be hard to imagine the world through someone else’s eyes. Reading books by authors of different gender, race, or socioeconomic status can help open your eyes to the challenges and issues others face. Explain how reading books by authors with different backgrounds has changed your worldview in your essay.

It’s fun to read the information that reinforces viewpoints that you already have, but doing so doesn’t contribute to expanding your mind and helping you see the world from a different perspective. Explain how pushing oneself to see a different point of view can help you better understand your perspective and help open your eyes to ideas you may not have considered.

Tip: If writing an essay sounds like a lot of work, simplify it. Write a simple 5 paragraph essay instead.

If you’re stuck picking your next essay topic, check out our round-up of essay topics about education .

Amanda has an M.S.Ed degree from the University of Pennsylvania in School and Mental Health Counseling and is a National Academy of Sports Medicine Certified Personal Trainer. She has experience writing magazine articles, newspaper articles, SEO-friendly web copy, and blog posts.

View all posts

- Homework Help

- Essay Examples

- Citation Generator

Writing Guides

- Essay Title Generator

- Essay Outline Generator

- Flashcard Generator

- Plagiarism Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Conclusion Generator

- Thesis Statement Generator

- Introduction Generator

- Literature Review Generator

- Hypothesis Generator

Writing Guides / How to Craft a Stellar 5-Paragraph Essay: A Step-by-Step Guide

How to Craft a Stellar 5-Paragraph Essay: A Step-by-Step Guide

What is a 5-Paragraph Essay?

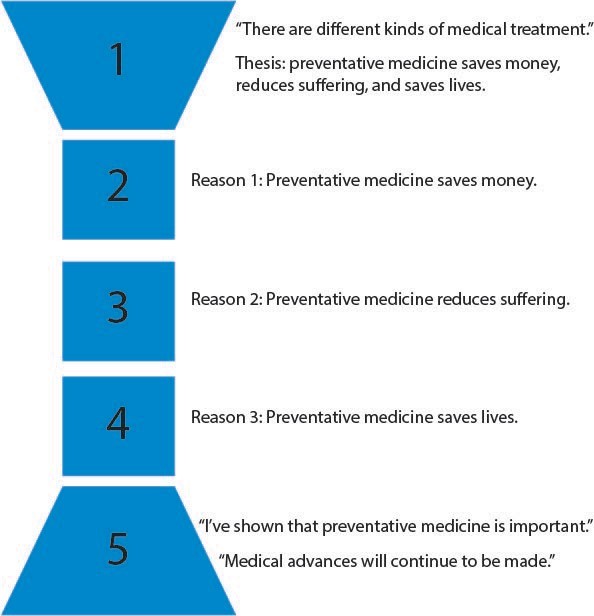

There is no better way to write a short scholastic essay than using the tried-and-true 5-paragraph essay format. It’s a simple template, consisting of an introductory paragraph, three topic paragraphs that make up the body, and a concluding paragraph. Each section of the body covers one point to support the main idea of the essay, stated in the introduction. It is simple, straight-forward, and by far the most common essay format used in schools. If you have an essay to write, you can’t go wrong if you stick to the 5-paragraph essay format. Follow this guideline, and your writing will be focused, to the point, and spot on.

How to Write a 5 Paragraph Essay

All you need to write a 5-paragraph essay is a main idea and three points to support that idea. Once you have that, you simply introduce the main idea in the first paragraph, use the subsequent second, third, and fourth paragraphs to support that idea, and close it out with the fifth paragraph, which restates the main idea in new words. Sounds easy enough, right?

Well, we can actually break it down even more. So, let’s take it step by step just to make sure you got it.

Choose a Topic

Before writing, you should have a clear topic in mind. This might be one that’s assigned to you, or if you have the freedom to choose, you can pick a subject you know something about or would like to learn more about. At any rate, it’s something you can identify and write about.

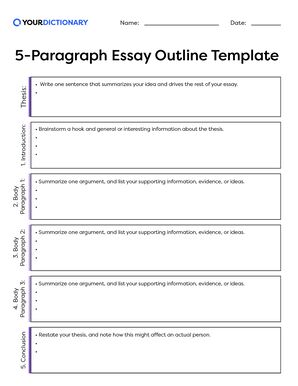

Research and Outline

Gather information about your topic and decide on the three main points or arguments you want to make in the body of your essay. This gives you a direction. Create an essay outline to organize your thoughts and that will serve as the roadmap for your paper. List the points in order of least important to most important.

Write the Introduction

Start the essay with a “ hook ”—an attention-grabbing statement that will get the reader’s interest. This could be an interesting fact, a quote, or a question. After the hook, introduce your topic and end the introduction with a clear thesis statement that presents your main argument or point.

Write the Body Paragraphs

Each of the three body paragraphs should start with a topic sentence that introduces the main idea of that paragraph. Follow the topic sentence with supporting details, examples, or evidence to back up your point. Each paragraph should focus on a single main idea that supports the thesis. So, all together there should be three elements of your main idea that you can write a paragraph about.

Write the Conclusion

Summarize the main points made in your essay and restate your thesis in a new way. You can also add a final thought that will give your reader something to ponder.

5 Paragraph Essay Format

Introduction

- Hook : This is a sentence that grabs the reader’s attention.

- Brief Introduction : This should be a few sentences introducing the topic.

- Thesis Statement : This is a clear statement of your main argument or point.

Body Paragraphs 1, 2, and 3

- Topic Sentence : This is the first sentence of the paragraph: it introduces the main idea of this paragraph.

- Supporting Details/Examples : This should consist of 2-3 sentences that provide evidence or explanations to support the topic sentence.

- Concluding Sentence : This summarizes the paragraph and provides a transition to the next topic paragraph.

- Restate Thesis : This reminds the reader of your main argument.

- Summary : This is where you recap the main points you made in your body paragraphs.

- Final Thought : This is a concluding thought to end your essay on a strong note.

This essay format is easy to use and gives a clear structure for presenting information. It is especially helpful for anyone who is new to writing. The more used to it you become, the more likely you will be to develop even longer, more complex essays over time.

5 Paragraph Essay Outline Examples

“The Benefits of Regular Exercising”

I. Introduction

- Hook: Imagine being able to improve your mental health, physical appearance, and lifespan with just a few hours of exercise a week. You would want to do it, wouldn’t you?

- Brief Introduction: Regular exercise supports a healthy lifestyle no matter who you are. Whether you are old, young, etc…

- Thesis Statement: The benefits of exercising regularly include an improved mental well-being, improved heart health, and reduced risk of chronic diseases.

II. Body Paragraph 1: Improved Mental Well-being

- Topic Sentence: One of the biggest benefits of regular exercise is the fact that it improves your mental health. How?

- Supporting Detail 1: First of all, exercise releases endorphins, which are natural mood lifters.

- Supporting Detail 2: Physical activity also reduces symptoms of anxiety and depression.

- Concluding Sentence: Clearly physical exercise has benefits for your brain—but what else can it do?

III. Body Paragraph 2: Boosted Cardiovascular Health

- Topic Sentence: Engaging in regular physical activity also greatly benefits the heart and circulatory system.

- Supporting Detail 1: Exercise strengthens the heart muscle, allowing it to pump blood more efficiently.

- Supporting Detail 2: Regular exercise helps regulate blood pressure, reducing the risk of hypertension.

- Concluding Sentence: Not only is it good for your mind, but exercise is also good for your body.

IV. Body Paragraph 3: Reduced Risk of Chronic Diseases

- Topic Sentence: Besides immediate benefits, exercise plays a crucial role in preventing various chronic diseases.

- Supporting Detail 1: Physical activity reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes by improving insulin sensitivity.

- Supporting Detail 2: Exercise plays a role in weight management, which can prevent obesity-related conditions like heart disease.

- Concluding Sentence: Thus, exercise helps prevent disease.

V. Conclusion

- Restate Thesis: The health advantages of regular exercise span from mental health to disease prevention.

- Summary: It’s good for the brain, the body, and the heart.

- Final Thought: With the knowledge of these benefits, don’t you think everyone should be incorporating regular exercise into one’s routine?

View 120,000+ High Quality Essay Examples

Learn-by-example to improve your academic writing

5 Paragraph Essay Example

The Power of Reading Books

Books have changed so much throughout history: from tablets and scrolls to paperbacks and now digital files that one can read on a screen, books have existed in many different forms. But one thing they have always been able to do is attract the attention of readers and having staying power. There is something magical about books that allows them to transcend both time and space. They are more than mere physical or digital objects, more than ancient collectibles, more than artifacts: they are repositories of human experiences, knowledge, and wisdom. Books are windows onto other worlds, windows onto other minds, windows onto other lives, windows onto new expanses. They are a way to grow, to challenge our preconceptions, redefine our boundaries, and introduce us to unfamiliar territories. Sure, they can be for leisure, but they can also be for our edification, our education, our self-improvement. Reading books can improve our cognitive abilities, enrich our lives, deepen our emotional depth, and fire up our creative engines.

Body Paragraph 1: Enriching the Mind

Reading enriches the mind, first of all. It is not a passive exercise like watching TV. Rather, it engages the cognitive functions of comprehension, visualization, and critical thinking, and forces them to work. It gets the mind to imagine, flex, think through problems, and reflect on information. Reading is like taking your brain to the gym. That is why readers develop good brain muscle and often have a well-rounded view of things that makes them more informed and open-minded than those who do not read.

Body Paragraph 2: Boosting Emotional Intelligence

Reading books also has a profound impact on our emotions. The world of literature, in particular, is a great way to understand in human emotions and relationships. Literature exposes readers to the innermost thoughts and feelings of characters, and gives insights into the human soul—insights that can enhance one’s emotional intelligence. Readers of literature can learn to discern subtle emotional cues, appreciate different perspectives, and develop a heightened sense of compassion.

Body Paragraph 3: Fostering Creativity

Reading is also a great way to kindle the imagination. All books offer a spark, and the imagination gets to work growing that spark into a flame that feeds on the wood one’s imagination brings. The imagination has the material; the book brings the fuel and fire. Reading helps the imagination play. This creative stimulation carries over into other aspects of the reader’s life, too. It can inspire artistic endeavors, be the impetus for pioneering innovations, and even lead to revolutionary ideas that reshape reality.

In this age of fleeting interactions, where instant gratification often supersedes depth, books stand apart as pathways to profound engagement. Their enduring charm lies not just in the tales they tell but in the growth they offer. Books are tools for the active participation of the mind and spirit. They enhance our imagination, our emotional development, and our creative impetus. To read is to grow. To read well is to become strong. Don’t you want to get reading now?

Explanation: An Analysis of the Essay

- Introduction: The essay commences by grounding the reader in history and showing that books have always been with us. This nod to the past sets the stage for the essay’s relevance in contemporary times. The introduction’s effectiveness lies in its ability to highlight books’ timeless value. The thesis also does more than introduce the main points; it acts as a roadmap, signposting the points that will be covered in the essay.

- Body Paragraph 1: The first body paragraph focuses on the intellectual nourishment derived from reading. It describes the way books facilitate mental growth. Its main point is that reading is good for the brain.

- Body Paragraph 2: The second paragraph transitions from the cerebral to the emotional. It explains why books are good for the emotions. It pays special attention to the fact that books offer windows onto what it means to be human, to feel, and to think. It suggests that reading literature is a great way to become emotionally educated—that books are good for nurturing empathy and providing emotional understanding.

- Body Paragraph 3: The third paragraph of the body is basically a tribute to the imaginative power that is fostered by reading books. It focuses on how reading is like a spark for the imagination’s fire. It connects reading to other activities, like innovating and creating works of art. It makes the case that there is a link between reading books and engaging more directly in the real world in a positive way.

- Conclusion: In its conclusion, the essay gives a thoughtful reflection, restates the main theme, goes over the main points again, and also gives a sense of why books have lasted so long. It leaves the reader with something to think about—namely that reading books actually makes you strong and helps you to grow as a person. It essentially leaves one with what is essentially a call to action.

The entire essay guides the reader, starting with the macro view in the introduction to the subtle and detailed examination of the finer points in the body. Each paragraph flows seamlessly into the next. The essay follows a clear structure, and presents each idea in a logical progression from introduction to conclusion.

5-Paragraph Essay FAQs

How many words should a 5-paragraph essay be.

The length of a 5-paragraph essay can vary depending on the purpose and complexity of the topic, as well as the intended audience. However, a typical 5-paragraph essay ranges from 250 to 500 words. Here’s a breakdown:

- Introduction: 50-100 words. This includes a brief introduction to the topic and the thesis statement.

- Body Paragraphs: Each body paragraph can range from 50 to 100 words. So, for three body paragraphs, you’re looking at 150-300 words in total. Each paragraph should introduce its main idea, provide supporting evidence or details, and possibly offer a transition to the next paragraph.

- Conclusion: 50-100 words. Summarize the main points and restate the thesis in a slightly different way.

Remember, these are just general guidelines. Depending on the depth of your analysis or the specific requirements of an assignment, your essay might be shorter or longer. The key is to ensure that you fully address your topic and support your thesis in a concise and organized manner.

Where is the thesis stated in a 5-paragraph essay?

In a standard 5-paragraph essay, the thesis is typically stated at the end of the introduction paragraph. It serves as a roadmap for the reader, providing a clear statement of the main argument or point you’ll be making in the essay. This positioning at the beginning of the essay allows readers to understand the central premise from the outset, setting the stage for the supporting details and arguments that follow in the body paragraphs.

Can I include quotes or citations in a 5-paragraph essay?

Absolutely! Including quotes, citations, or references can strengthen your arguments and provide evidence for the claims you make. If you’re writing an analytical or argumentative essay, it’s especially important to back up your points with credible sources. When incorporating quotes or data, make sure to properly cite them according to the style guide you’re following (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago). However, make sure your essay doesn’t become overly reliant on quotes; your original analysis and voice should remain central.

Can a 5-paragraph essay have a title?

Yes, a 5-paragraph essay can—and often should—have a title. A well-chosen title can capture the essence of your essay, intrigue the reader, and set the tone for your content. It should be relevant to your topic and thesis, but it can also be creative or thought-provoking. If you’re writing an essay for a class assignment, make sure to check if there are any specific guidelines regarding titles.

Do I always have to stick to the 5-paragraph format?

Not necessarily. The 5-paragraph essay is a foundational structure to help novice writers organize their thoughts. However, as you advance in your writing skills or tackle more complex topics, you might find that you need more (or fewer) than three body paragraphs to adequately address your subject. The key is to make certain that each paragraph has a clear purpose and supports your overall thesis. Always prioritize clarity, coherence, and depth of analysis over strict adherence to a set number of paragraphs.

How do I choose a topic for my 5-paragraph essay?

Choosing a topic depends on the purpose of the essay. If it’s for a class assignment, you might be given a prompt or a list of topics to select from. If you have the freedom to choose, pick a subject you’re passionate about or interested in. A good topic is neither too broad (which would be hard to cover in a short essay) nor too narrow (which might not give you enough to write about). Brainstorm a list, do some preliminary research, think about what you know, and choose a topic that you believe you can present compelling arguments or insights about.

How do I transition between paragraphs?

Smooth transitions help guide your readers through your essay and enhance its flow. You can use transitional words or phrases at the beginning of your body paragraphs to introduce the main idea and show its relation to the previous paragraph. Common transitional words include “furthermore,” “however,” “in addition,” “for instance,” and “on the other hand.” Additionally, you can subtly link paragraphs by referring back to a point made in the previous paragraph or hinting at what’s to come.

How important is the conclusion in a 5-paragraph essay?

The conclusion is vital. It provides closure and reinforces your main points. A strong conclusion doesn’t just repeat what’s been said but offers a departing thought based on the content. It leaves the reader with a lasting impression or something to consider. But at the same time, it is not the place for introducing entirely new ideas or topics; instead, focus on wrapping up and reinforcing your essay’s central argument.

Take the first step to becoming a better academic writer.

Writing tools.

- How to write a research proposal 2021 guide

- Guide to citing in MLA

- Guide to citing in APA format

- Chicago style citation guide

- Harvard referencing and citing guide

- How to complete an informative essay outline

How to Write a Synthesis Essay: Tips and Techniques

Why Using Chat-GPT for Writing Your College Essays is Not Smart

The Importance of an Outline in Writing a Rhetorical Analysis Essay

A Guide to Choosing the Perfect Compare and Contrast Essay Topic

Guide on How to Write a 5 Paragraph Essay Effortlessly

Defining What Is a 5 Paragraph Essay

Have you ever been assigned a five-paragraph essay and wondered what exactly it means? Don't worry; we all have been there. A five-paragraph essay is a standard academic writing format consisting of an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

In the introduction, you present your thesis statement, which is the main idea or argument you will discuss in your essay. The three body paragraphs present a separate supporting argument, while the conclusion summarizes the main points and restates the thesis differently.

While the five-paragraph essay is a tried and true format for many academic assignments, it's important to note that it's not the only way to write an essay. In fact, some educators argue that strict adherence to this format can stifle creativity and limit the development of more complex ideas.

However, mastering the five-paragraph essay is a valuable skill for any student, as it teaches the importance of structure and organization in writing. Also, it enables you to communicate your thoughts clearly and eloquently, which is crucial for effective communication in any area. So the next time you're faced with a five-paragraph essay assignment, embrace the challenge and use it as an opportunity to hone your writing skills.

And if you find it difficult to put your ideas into 5 paragraphs, ask our professional service - 'please write my essay ,' or ' write my paragraph ' and consider it done.

How to Write a 5 Paragraph Essay: General Tips

If you are struggling with how to write a 5 paragraph essay, don't worry! It's a common format that many students learn in their academic careers. Here are some tips from our admission essay writing service to help you write a successful five paragraph essay example:

- Start with a strong thesis statement : Among the 5 parts of essay, the thesis statement can be the most important. It presents the major topic you will debate throughout your essay while being explicit and simple.

- Use topic sentences to introduce each paragraph : The major idea you will address in each of the three body paragraphs should be established in a concise subject sentence.

- Use evidence to support your arguments : The evidence you present in your body paragraphs should back up your thesis. This can include facts, statistics, or examples from your research or personal experience.

- Include transitions: Use transitional words and phrases to make the flow of your essay easier. Words like 'although,' 'in addition,' and 'on the other hand' are examples of these.

- Write a strong conclusion: In addition to restating your thesis statement in a new way, your conclusion should highlight the key ideas of your essay. You might also leave the reader with a closing idea or query to reflect on.

- Edit and proofread: When you've completed writing your essay, thoroughly revise and proofread it. Make sure your thoughts are brief and clear and proofread your writing for grammatical and spelling mistakes.

By following these tips, you can write strong and effective five paragraph essays examples that will impress your teacher or professor.

5 Paragraph Essay Format

Let's readdress the five-paragraph essay format and explain it in more detail. So, as already mentioned, it is a widely-used writing structure taught in many schools and universities. A five-paragraph essay comprises an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion, each playing a significant role in creating a well-structured and coherent essay.

The introduction serves as the opening paragraph of the essay and sets the tone for the entire piece. It should captivate the reader's attention, provide relevant background information, and include a clear and concise thesis statement that presents the primary argument of the essay. For example, if the essay topic is about the benefits of exercise, the introduction may look something like this:

'Regular exercise provides numerous health benefits, including increased energy levels, improved mental health, and reduced risk of chronic diseases.'

The body paragraphs are the meat of the essay and should provide evidence and examples to support the thesis statement. Each body paragraph should begin with a subject sentence that states the major idea of the paragraph. Then, the writer should provide evidence to support the topic sentence. This evidence can be in the form of statistics, facts, or examples. For instance, if the essay is discussing the health benefits of exercise, a body paragraph might look like this:

'One of the key benefits of exercise is improved mental health. Regular exercise has been demonstrated in studies to lessen depressive and anxious symptoms and enhance mood.'

The essay's final paragraph, the conclusion, should repeat the thesis statement and summarize the essay's important ideas. A concluding idea or query might be included to give the reader something to ponder. For example, a conclusion for an essay on the benefits of exercise might look like this:

'In conclusion, exercise provides numerous health benefits, from increased energy levels to reduced risk of chronic diseases. We may enhance both our physical and emotional health and enjoy happier, more satisfying lives by including exercise into our daily routines.'

Overall, the 5 paragraph essay format is useful for organizing thoughts and ideas clearly and concisely. By following this format, writers can present their arguments logically and effectively, which is easy for the reader to follow.

Types of 5 Paragraph Essay

There are several types of five-paragraph essays, each with a slightly different focus or purpose. Here are some of the most common types of five-paragraph essays:

- Narrative essay : A narrative essay tells a story or recounts a personal experience. It typically includes a clear introductory paragraph, body sections that provide details about the story, and a conclusion that wraps up the narrative.

- Descriptive essay: A descriptive essay uses sensory language to describe a person, place, or thing. It often includes a clear thesis statement that identifies the subject of the description and body paragraphs that provide specific details to support the thesis.

- Expository essay: An expository essay offers details or clarifies a subject. It usually starts with a concise introduction that introduces the subject, is followed by body paragraphs that provide evidence and examples to back up the thesis, and ends with a summary of the key points.

- Persuasive essay: A persuasive essay argues for a particular viewpoint or position. It has a thesis statement that is clear, body paragraphs that give evidence and arguments in favor of it, and a conclusion that summarizes the important ideas and restates the thesis.

- Compare and contrast essay: An essay that compares and contrasts two or more subjects and looks at their similarities and differences. It usually starts out simply by introducing the topics being contrasted or compared, followed by body paragraphs that go into more depth on the similarities and differences, and a concluding paragraph that restates the important points.

Each type of five-paragraph essay has its own unique characteristics and requirements. When unsure how to write five paragraph essay, writers can choose the most appropriate structure for their topic by understanding the differences between these types.

5 Paragraph Essay Example Topics

Here are some potential topics for a 5 paragraph essay example. These essay topics are just a starting point and can be expanded upon to fit a wide range of writing essays and prompts.

- The Impact of Social Media on Teenage Communication Skills.

- How Daily Exercise Benefits Mental and Physical Health.

- The Importance of Learning a Second Language.

- The Effects of Global Warming on Marine Life.

- The Role of Technology in Modern Education.

- The Influence of Music on Youth Culture.

- The Pros and Cons of Uniform Policies in Schools.

- The Significance of Historical Monuments in Cultural Identity.

- The Growing Importance of Cybersecurity.

- The Evolution of the American Dream.

- The Impact of Diet on Cognitive Functioning.

- The Role of Art in Society.

- The Future of Renewable Energy Sources.

- The Effects of Urbanization on Wildlife.

- The Importance of Financial Literacy for Young Adults.

- The Influence of Advertising on Consumer Choices.

- The Role of Books in the Digital Age.\

- The Benefits and Challenges of Space Exploration.

- The Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture.

- The Ethical Implications of Genetic Modification.

Don't Let Essay Writing Stress You Out!

Order a high-quality, custom-written paper from our professional writing service and take the first step towards academic success!

General Grading Rubric for a 5 Paragraph Essay

The following is a general grading rubric that can be used to evaluate a five-paragraph essay:

Content (40%)

- A thesis statement is clear and specific

- The main points are well-developed and supported by evidence

- Ideas are organized logically and coherently

- Evidence and examples are relevant and support the main points

- The essay demonstrates a strong understanding of the topic

Organization (20%)

- The introduction effectively introduces the topic and thesis statement

- Body paragraphs are well-structured and have clear topic sentences

- Transitions between paragraphs are smooth and effective

- The concluding sentence effectively summarizes the main points and restates the thesis statement

Language and Style (20%)

- Writing is clear, concise, and easy to understand

- Language is appropriate for the audience and purpose

- Vocabulary is varied and appropriate

- Grammar, spelling, and punctuation are correct

Critical Thinking (20%)

- Student demonstrate an understanding of the topic beyond surface-level knowledge

- Student present a unique perspective or argument

- Student show evidence of critical thinking and analysis

- Students write well-supported conclusions

Considering the above, the paper should demonstrate a thorough understanding of the topic, clear organization, strong essay writing skills, and critical thinking. By using this grading rubric, the teacher can evaluate the essay holistically and provide detailed feedback to the student on areas of strength and areas for improvement.

Five Paragraph Essay Examples

Wrapping up: things to remember.

In conclusion, writing a five paragraph essay example can seem daunting at first, but it doesn't have to be a difficult task. Following these simple steps and tips, you can break down the process into manageable parts and create a clear, concise, and well-organized essay.

Remember to start with a strong thesis statement, use topic sentences to guide your paragraphs, and provide evidence and analysis to support your ideas. Don't forget to revise and proofread your work to make sure it is error-free and coherent. With time and practice, you'll be able to write a 5 paragraph essay with ease and assurance. Whether you're writing for school, work, or personal projects, these skills will serve you well and help you to communicate your ideas effectively.

Meanwhile, you can save time and reduce the stress associated with academic assignments by trusting our research paper writing services to handle the writing for you. So go ahead, buy an essay , and see how easy it can be to meet all of your professors' complex requirements!

Ready to Take the Stress Out of Essay Writing?

Order your 5 paragraph essay today and enjoy a high-quality, custom-written paper delivered promptly

Related Articles

.webp)

How to Write a Five-Paragraph Essay (with Examples)

By: Author Marcel Iseli

Posted on Last updated: April 13, 2023

Sharing is caring!

Writing can be either exciting or exacting depending on one’s patience and passion, hence not everyone’s cup of joe.

That said, writing even a short, snappy five-paragraph essay can require a bit of time and attention – at least for those who are not used to it.

Luckily enough, that’s what we’re dealing with today. If you’re paying enough attention, this post’s intro should already be giving you some idea of how to start one.

Writing a five-paragraph essay

- Write the hook and thesis statement in the first paragraph.

- Write the conflict of the essay in the second paragraph.

- Write the supporting details of the conflict in the third paragraph.

- Write the weakest arguments in the fourth paragraph.

- Write the summary and call-to-action prompt in the fifth paragraph.

Determining what to include in a five-paragraph essay

While there are hundreds, even thousands, of ways to write a five-paragraph essay, there are some universal processes that we can meanwhile follow.

The overall organization of the writer’s thought matters in any kind of writing piece. So, it is necessary that you fully understand what you’re being asked to do before writing a piece.

Topic, purpose, audience, rhetorical appeal, and length

Understanding what needs to be done means knowing your essay’s topic, purpose, audience, rhetorical appeal, as well as desired length.

Topic means the subject matter entailed by your essay, such as when you are asked to write an essay about yourself or people you admire.

“Purpose” means the core intent of writing your essay, which can be done in an argumentative, expository, narrative, or descriptive way.

“Audience” refers to your target reader or readers. You would know this by answering the question “Who will read and assess my essay?”

A “rhetorical appeal” is the “persuasive act” of your essay. It demonstrates the qualities of your essay that make it worth reading and even sharing.

Meanwhile, “length” means the measurable elements in your essay, such as the number of characters, words, sentences, or paragraphs.

Knowing these five important parts should give a head start when you write an essay, no matter what kind of setting it is.

If you are writing to apply for a particular job role, you may also be required to write a cover letter for your essay by the organization.

The possibility of this particular scenario should be enough to let us realize how important writing skills are, which is why we need to deliberately learn them at school.

In some cases, students may just mindlessly think that it is okay to cut and paste texts from online sources because their teacher won’t find out anyway.

Contrary to common belief, teachers, especially the most seasoned and passionate ones actually do read their students’ work.

So, by no stretch, one might actually end up writing an apology letter for plagiarism if and when worse comes to worst.

The key to preventing this tragedy is to always bear in mind that sincerity evokes originality; when you love what you do, you can always generate fresh ideas.

Meanwhile, the key to creating a good essay is to pre-plan what you need to include as well as what you need to exclude in the writing piece.

Now, how can we manifest all the things explained above in a five-paragraph essay? Let us find out below.

Paragraph 1 of the five-paragraph essay — The “plot”

The first or introductory paragraph can be considered the “plot” of the essay. This is where you would need to write your hook and thesis statement.

The hook is what grabs your readers’ attention from the start. It should be written in such a way that it anchors or “hooks” them to what they are reading.

You can use a general or all-inclusive idea for this part to make your readers relate to what you are trying to say.

Example:

Meanwhile, the thesis statement briefly tells your readers what your topic is all about. In other words, it explains what they need to expect from the piece.

The thesis statement is perhaps the most important element that you should never miss out on because it is what links your thoughts as a writer to your audience.

Within the intro paragraph, you could add other ideas that would link your hook to your thesis statement, depending on the impression you would like to evoke.

Paragraph 2 of the five-paragraph essay — The “plot’s conflict”

The second paragraph is where you slowly build the tension and explain your plot in more detail. We might as well call it the conflict of the story you are trying to tell.

Here, you should be able to clearly explain your strongest point of argument. For narrative essays, this is where you write the most crucial part of the experience you’ve had.

You should also introduce the setting as well as other relevant characters in this part, such as this one:

Then, you have to carefully elaborate on the most critical part of the story. If you could be more “visual” with your words, that would also help more in letting your audience connect to your essay.

In the next example, you would see a person vs. nature conflict where the character struggles with the environmental forces.

Paragraph 3 of the five-paragraph essay — The “conflict’s sidekick”

As you may figure, paragraph three is a further elaboration of your second paragraph, which is why we could simply call it the “conflict’s support.”

Here, you need to clearly establish how the current paragraph connects to the previous one and end it in such a way that it also links to the succeeding paragraph.

This is also where you give more meticulous details about the conflict to let your readers understand the “whys.”

The airbag from the driver’s side malfunctioned and deployed on its own, causing Uncle Vince to lose control. I later found out too that Uncle Vince wanted to learn how to drive so he asked my dad to teach him.

Paragraph 4 of the five-paragraph essay — The “freebie”

The fourth paragraph is where you would put the least important part of your story, at least relatively speaking.

You should put here your weakest or most irrelevant argument and example details. Or, you could also provide a different point of view to your audience.

Feel free to shift from the past to the present times in this part to pull your audience back to reality.

If relevant, you could also add some more emotional details like guilt or regret, such as the following:

Then lastly, you should be able to establish a link to your last paragraph or conclusion. The example below has a lot to do with the ending of the story, which talks about realizations.

Paragraph 5 of the five-paragraph essay — The “farewell”

The “farewell” or conclusion part basically needs to summarize your entire essay’s key ideas. It should also be able to draw a link to the plot or intro paragraph.

In other words, the fifth or last paragraph should bear ideas that reconcile the previous paragraphs, especially the first.

If you are sick and tired of using almost the same words and phrases in your essay’s conclusion part, you had better check out other alternatives for “in conclusion” to sound less repetitive.

There are actually a lot of effective transition words for your conclusion to choose from in the English lexicon, so feel free to experiment some time.

Then, you can talk about the positive things that happened after the storm to leave a positive message to your readers.

Last but not least, you can completely end your essay with a call-to-action prompt that urges your readers to “do” something about what they have just read.

You can easily do this by answering the question “What do I want my audience to do after reading my story?” such as in the example below:

Five-Paragraph Essay — Sample Essay

To really see how all the parts above fit together, here’s a complete example essay containing all the elements elaborated on earlier.

In this essay, the topic is “the greatest challenge in my life,” and it has a narrative purpose. The target audience is the general public, while the rhetorical appeal is “pathos” or emotional.

This is a five-paragraph essay with approximately six hundred words including the title that talks about the loss of a loved one.

❡ 2 One sunny afternoon in the early nineties, I was playing catch with my neighbors Dylan, Abby, and my adorable labrador Rio. We did love playing by the road because it annoys old Miss Vacuum Lady from across the street – she nags at us all the time. As I was throwing the beanbag for Rio to catch, I noticed an unfamiliar blue Ford Explorer coming. It was running funny, so I thought the driver was just trying to do some tricks. I managed to throw the beanbag nicely, and Rio ran with all his might to catch it before it falls. A few seconds later, I heard a deafening screech and saw the blue Explorer crashing onto the maple tree outside Miss Vaccum Lady’s house. I only got scared when I realized that the car was actually trying to avoid me and that it chose to crash onto the tree instead.

❡ 3 A few moments later, I saw my mom and my other neighbors rushing outside to see what had just happened. I and my friends ran towards the car too until I heard a loud scream coming from my mom. Then all of a sudden, it came to me. My dad was in the passenger seat of that car, while his fifteen-year-old younger brother Uncle Vince was in the driver’s seat. Miraculously, Uncle Vince only had a scratch on his arm, yet my dad was neither moving nor breathing anymore – he died at that exact moment. The airbag from the driver’s side malfunctioned and deployed on its own, causing Uncle Vince to lose control. I later found out too that Uncle Vince wanted to learn how to drive so he asked my dad to teach him.

❡ 4 Everything changed after that day. No one was there to fix our busted lights anymore. No one was there to repair the roof when it leaked. I never even got to learn to play the guitar – dad had promised to buy me one on my birthday that same week he passed. For years and years, I kept blaming myself for what had happened that I never played catch again. They say “mothers know best,” and that’s a fact. Mom helped me get through all the pain and trauma even if she was also hurting a lot deep inside. For that reason, I never hesitate to trade my life for hers.

❡ 5 True enough, losing my dad has been the greatest challenge in my life. But, as time passed by, I also realized that seeing my mom suck it all up and pretend that she was fine even if she was hurting so much more. So, I made a decision never to waste a single moment with her. I have also managed to become an advocate for an organization that helps single mothers raise their kids. If there’s one thing I’ve learned from what happened, that is parental love is definitely the most selfless act in this world. So, never miss a beat with yours while you can.

Frequently Asked Questions on “How to Write a Five-paragraph Essay”

What are some good topics for a five-paragraph essay.

Social justice issues like healthcare, education, prejudice, and violence; environmental issues like climate change, resource depletion, wildlife protection, and natural disasters; life topics like near-death experiences, hobbies, and traveling are great topics for a five-paragraph essay.

How do you start a five-paragraph essay?

To start a five-paragraph essay, a hook and thesis statement are necessary. A hook can be a reflective assumption, a quote from a famous person, or a rhetorical question, while a thesis statement is a brief explanation of the essay’s topic.

How many sentences is a five-paragraph essay?

A five-paragraph essay is made of twenty-five to forty-five sentences. This structure is made up of five hundred to around one thousand words.

Writing requires time, patience, and dedication. That said, a read-worthy piece cannot come into form mindlessly but rather meticulously.

Join us again next time for some more interesting writing and other language-related hacks that can help you walk more easily through life.

Hey fellow Linguaholics! It’s me, Marcel. I am the proud owner of linguaholic.com. Languages have always been my passion and I have studied Linguistics, Computational Linguistics and Sinology at the University of Zurich. It is my utmost pleasure to share with all of you guys what I know about languages and linguistics in general.

Related posts:

- How to Write an Essay about Yourself — The Ultimate Guide

- How to Write a Cover Letter for an Essay in 13 Steps

- How to Write an Open Letter — Three Easy Steps

- Thank You Note for Engagement Gift Etiquette & Examples

- How to Write a Thank You Note to the Mailman (with Examples)

The Ultimate Guide to the 5-Paragraph Essay

PeopleImages / Getty Images

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

A five-paragraph essay is a prose composition that follows a prescribed format of an introductory paragraph, three body paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph, and is typically taught during primary English education and applied on standardized testing throughout schooling.

Learning to write a high-quality five-paragraph essay is an essential skill for students in early English classes as it allows them to express certain ideas, claims, or concepts in an organized manner, complete with evidence that supports each of these notions. Later, though, students may decide to stray from the standard five-paragraph format and venture into writing an exploratory essay instead.

Still, teaching students to organize essays into the five-paragraph format is an easy way to introduce them to writing literary criticism, which will be tested time and again throughout their primary, secondary, and further education.

Writing a Good Introduction

The introduction is the first paragraph in your essay, and it should accomplish a few specific goals: capture the reader's interest, introduce the topic, and make a claim or express an opinion in a thesis statement.

It's a good idea to start your essay with a hook (fascinating statement) to pique the reader's interest, though this can also be accomplished by using descriptive words, an anecdote, an intriguing question, or an interesting fact. Students can practice with creative writing prompts to get some ideas for interesting ways to start an essay.

The next few sentences should explain your first statement, and prepare the reader for your thesis statement, which is typically the last sentence in the introduction. Your thesis sentence should provide your specific assertion and convey a clear point of view, which is typically divided into three distinct arguments that support this assertation, which will each serve as central themes for the body paragraphs.

Writing Body Paragraphs

The body of the essay will include three body paragraphs in a five-paragraph essay format, each limited to one main idea that supports your thesis.

To correctly write each of these three body paragraphs, you should state your supporting idea, your topic sentence, then back it up with two or three sentences of evidence. Use examples that validate the claim before concluding the paragraph and using transition words to lead to the paragraph that follows — meaning that all of your body paragraphs should follow the pattern of "statement, supporting ideas, transition statement."

Words to use as you transition from one paragraph to another include: moreover, in fact, on the whole, furthermore, as a result, simply put, for this reason, similarly, likewise, it follows that, naturally, by comparison, surely, and yet.

Writing a Conclusion

The final paragraph will summarize your main points and re-assert your main claim (from your thesis sentence). It should point out your main points, but should not repeat specific examples, and should, as always, leave a lasting impression on the reader.

The first sentence of the conclusion, therefore, should be used to restate the supporting claims argued in the body paragraphs as they relate to the thesis statement, then the next few sentences should be used to explain how the essay's main points can lead outward, perhaps to further thought on the topic. Ending the conclusion with a question, anecdote, or final pondering is a great way to leave a lasting impact.

Once you complete the first draft of your essay, it's a good idea to re-visit the thesis statement in your first paragraph. Read your essay to see if it flows well, and you might find that the supporting paragraphs are strong, but they don't address the exact focus of your thesis. Simply re-write your thesis sentence to fit your body and summary more exactly, and adjust the conclusion to wrap it all up nicely.

Practice Writing a Five-Paragraph Essay

Students can use the following steps to write a standard essay on any given topic. First, choose a topic, or ask your students to choose their topic, then allow them to form a basic five-paragraph by following these steps:

- Decide on your basic thesis , your idea of a topic to discuss.

- Decide on three pieces of supporting evidence you will use to prove your thesis.

- Write an introductory paragraph, including your thesis and evidence (in order of strength).

- Write your first body paragraph, starting with restating your thesis and focusing on your first piece of supporting evidence.

- End your first paragraph with a transitional sentence that leads to the next body paragraph.

- Write paragraph two of the body focussing on your second piece of evidence. Once again make the connection between your thesis and this piece of evidence.

- End your second paragraph with a transitional sentence that leads to paragraph number three.

- Repeat step 6 using your third piece of evidence.

- Begin your concluding paragraph by restating your thesis. Include the three points you've used to prove your thesis.

- End with a punch, a question, an anecdote, or an entertaining thought that will stay with the reader.

Once a student can master these 10 simple steps, writing a basic five-paragraph essay will be a piece of cake, so long as the student does so correctly and includes enough supporting information in each paragraph that all relate to the same centralized main idea, the thesis of the essay.

Limitations of the Five-Paragraph Essay

The five-paragraph essay is merely a starting point for students hoping to express their ideas in academic writing; there are some other forms and styles of writing that students should use to express their vocabulary in the written form.

According to Tory Young's "Studying English Literature: A Practical Guide":

"Although school students in the U.S. are examined on their ability to write a five-paragraph essay , its raison d'être is purportedly to give practice in basic writing skills that will lead to future success in more varied forms. Detractors feel, however, that writing to rule in this way is more likely to discourage imaginative writing and thinking than enable it. . . . The five-paragraph essay is less aware of its audience and sets out only to present information, an account or a kind of story rather than explicitly to persuade the reader."

Students should instead be asked to write other forms, such as journal entries, blog posts, reviews of goods or services, multi-paragraph research papers, and freeform expository writing around a central theme. Although five-paragraph essays are the golden rule when writing for standardized tests, experimentation with expression should be encouraged throughout primary schooling to bolster students' abilities to utilize the English language fully.

- How To Write an Essay

- How to Write a Great Essay for the TOEFL or TOEIC

- Write an Attention-Grabbing Opening Sentence for an Essay

- How to Write and Format an MBA Essay

- How to Structure an Essay

- How to Help Your 4th Grader Write a Biography

- Definition and Examples of Body Paragraphs in Composition

- What Is Expository Writing?

- What an Essay Is and How to Write One

- Paragraph Writing

- 3 Changes That Will Take Your Essay From Good To Great

- An Introduction to Academic Writing

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- The Five Steps of Writing an Essay

- How to Write a Solid Thesis Statement

- The Introductory Paragraph: Start Your Paper Off Right

2 A Review of Essays and Paragraphs

Learning Objectives

- Write a clear thesis statement that unifies your essay

- Organize sentences around a topic sentence in a body paragraph

- Create smooth transitions in a paragraph

Download and/or print this chapter: Reading, Thinking, and Writing for College – Ch. 2

Basic Essay Structure

Most likely, if you’re a first-semester college student, the last time you had to write an essay was in high school. High school essay writing typically emphasizes the five-paragraph essay: introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. If you’ve been out of high school for a while or if you struggled with essay writing in high school, this chapter will help you review this basic structure, which can serve as a foundation for your college-level essays.

The skills that go into the five-paragraph essay are indispensable. The outline below in Figure 3.1 is probably what you’ve been taught about essay structure. The introduction starts general and gradually narrows to a thesis, which readers expect to find at the very end of that paragraph. In this format, the thesis uses that magic number of three: three reasons why a statement is true. Each of those reasons is explained and justified in the three body paragraphs, and then the conclusion restates the thesis before gradually getting broader. This format is easy for readers to follow, and it helps writers to organize their points and the evidence that goes with them. That’s why you learned this format.

Figure 3.1 The traditional five-paragraph essay structure

All that time you spent mastering the five-paragraph form in Figure 3.1 was not wasted. In a college-level writing class, though, you’ll be expected to move beyond this basic formula. The video below explains the basic five-paragraph essay structure and how you will be expected to develop a more sophisticated approach to writing for your college classes.

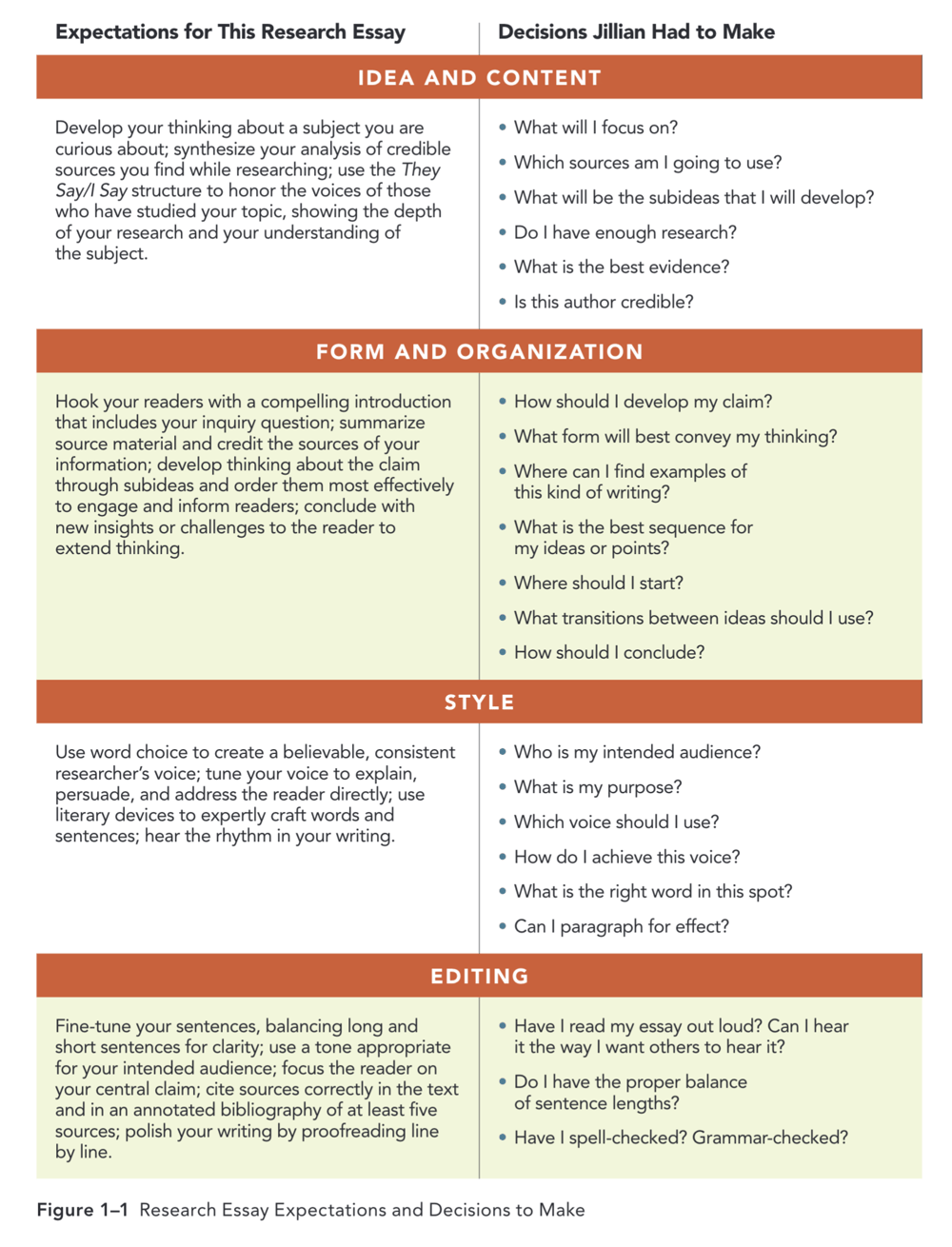

As the video explained, the body paragraphs in your essays are supposed to develop your thesis, and the thesis, as you may recall, is the “main idea” or “main claim” of your essay. For college-level writing, though, the thesis usually does more than simply announce the main idea of your essay. A good thesis is an original idea or opinion that you’ve developed by studying, reading, and thinking critically about your topic. A good thesis statement conveys your purpose for writing and previews what’s coming in your essay. In addition, a college-level thesis meets these criteria:

- A good thesis is non-obvious. High school teachers needed to make sure that you and all your classmates mastered the basic form of the academic essay. Thus, they were mostly concerned that you had a clear and consistent thesis, even if it was something obvious like “sustainability is important.” A thesis statement like that has a wide-enough scope to incorporate several supporting points and concurring evidence, enabling the writer to demonstrate his or her mastery of the five-paragraph form. Good enough for high school! When they can, high school teachers nudge students to develop arguments that are less obvious, more original, and more engaging. College instructors, on the other hand, always expect you to produce something more sophisticated and specific. They also want you to go beyond the obvious and offer your original thinking about a topic. To write a good thesis, therefore, most writers revise their thesis statements as they work on their essays. Writing about a topic helps them discover more interesting, specific points to make about the topic. A good thesis reflects good critical thinking and an original perspective.

- A good thesis is arguable . In everyday life, “arguable” is often used as a synonym for “controversial.” For a thesis, though, “arguable” doesn’t mean highly opinionated, and the goal of an academic essay isn’t necessarily to convert every reader to your way of thinking. Rather, a good thesis offers readers a new idea, a new perspective, or an opinion about a topic. The need to be arguable dovetails with the need to be specific: only when we have deeply explored a problem can we arrive at an original and specific argument that legitimately needs 3, 5, 10, or 20 pages to explain and justify. In that way, a good thesis sets an ambitious agenda for a paper.

- A good thesis is specific . You don’t want to set too ambitious an agenda, though! Some student writers fear that they won’t have enough to write about if they present a specific thesis, so they attempt to cover too much. A thesis like “sustainability is important” may seem like a great thesis because one could write all of the reasons for why it’s important, but the vague language invites a superficial discussion of a complicated topic. A thesis like “sustainability policies will inevitably fail if they do not incorporate social justice” limits the scope of the discussion, which in turn means that the essay itself will provide a more in-depth discussion of sustainability policies. It could even be more specific: which sustainability policies?

How do you produce a thesis that meets these criteria? Many instructors and writers find useful a metaphor based on this passage by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. [1]

There are one-story intellects, two-story intellects, and three-story intellects with skylights. All fact collectors who have no aim beyond their facts are one-story men. Two-story men compare, reason, generalize using the labor of fact collectors as their own. Three-story men idealize, imagine, predict—their best illumination comes from above the skylight.

The biggest benefit of the three-story metaphor is that it describes a process for building a thesis. To build the first story, you first have to get familiar with the complex, relevant facts surrounding the problem or question. You have to be able to describe the situation thoroughly and accurately. Then, with that first story built, you can layer on the second story by formulating the insightful, arguable point that animates the analysis. That’s often the most effortful part: brainstorming, elaborating and comparing alternative ideas, finalizing your point. With that specified, you can frame up the third story by articulating why the point you make matters beyond its particular topic or case.

For example, imagine you have been assigned a paper about the impact of online learning in higher education. You would first construct an account of the origins and multiple forms of online learning and assess research findings about its use and effectiveness. If you’ve done that well, you’ll probably come up with a well considered opinion that wouldn’t be obvious to readers who haven’t looked at the issue in depth. Maybe you’ll want to argue that online learning is a threat to the academic community. Or perhaps you’ll want to make the case that online learning opens up pathways to college degrees that traditional campus-based learning does not. In the course of developing your central, argumentative point, you’ll come to recognize its larger context; in this example, you may claim that online learning can serve to better integrate higher education with the rest of society, as online learners bring their educational and career experiences together.

To outline this example:

- First story : Online learning is becoming more prevalent and takes many different forms.

- Second story : While most observers see it as a transformation of higher education, online learning is better thought of an extension of higher education in that it reaches learners who aren’t disposed to participate in traditional campus-based education.

- Third story : Online learning appears to be a promising way to better integrate higher education with other institutions in society, as online learners integrate their educational experiences with the other realms of their life, promoting the freer flow of ideas between the academy and the rest of society.

Here’s another example of a three-story thesis: [3]

- First story : Edith Wharton did not consider herself a modernist writer, and she didn’t write like her modernist contemporaries.

- Second story : However, in her work we can see her grappling with both the questions and literary forms that fascinated modernist writers of her era. While not an avowed modernist, she did engage with modernist themes and questions.

- Third story : Thus, it is more revealing to think of modernism as a conversation rather than a category or practice.

Here’s one more example:

- First story : Scientists disagree about the likely impact in the U.S. of the light brown apple moth (LBAM) , an agricultural pest native to Australia.

- Second story : Research findings to date suggest that the decision to spray pheromones over the skies of several southern Californian counties to combat the LBAM was poorly thought out.

- Third story : Together, the scientific ambiguities and the controversial response strengthen the claim that industrial-style approaches to pest management are inherently unsustainable.

A thesis statement that stops at the first story isn’t usually considered a thesis. A two-story thesis is usually considered competent, though some two-story theses are more intriguing and ambitious than others. A thoughtfully crafted and well informed three-story thesis puts the author on a smooth path toward an excellent paper.

Basic Paragraph Structure

Think back to when you first learned to write paragraphs. Maybe you learned that paragraphs are supposed to have a certain number of sentences, or maybe you learned an acronym for what a paragraph is, such as the P. I. E. paragraph format (P=point, I=information, E=explanation). Some students learn to write paragraphs that follow certain patterns, such as narrative or compare/contrast. Whatever you learned about paragraphs, you probably remember that paragraphs need to include a topic sentence, supporting information, smooth transitions from one sentence to the next, and a concluding sentence. Take a moment to review these elements of all paragraphs.

Topic Sentences

The main idea of the paragraph is stated in the topic sentence. A good topic sentence does the following:

- introduces the rest of the paragraph

- contains both a topic and an idea or opinion about that topic

- is clear and easy to follow

- does not include supporting details

- engages the reader

For example:

Development of the Alaska oil fields threaten the already-endangered Northern Sea Otters.

This sentence introduces the topic and the writer’s opinion. After reading this sentence, a reader might reasonably expect the writer to go on to provide supporting details and facts about what the threat is. The sentence is clear and the word choice is interesting.

Here is another example:

Many major league baseball players have cheated by “corking” their bats.

Again, the topic and opinion are clear and specific, the details (what is corking? which players?) are saved for later, and the word choice is powerful.

Now look at this example:

I think everyone should be able to take a pet, especially service pets, to work because they provide comfort, and the potential problems they might cause can be eliminated if companies develop good policies.

Even though the topic and opinion are evident, the sentence is not focused or specific. It’s not likely that the writer could provide enough support to argue that every place of employment, from McDonald’s to a law office, should allow any kind of pets, from service dogs to parakeets. Furthermore, the writer is also offering two points that need to be discussed: pets provide comfort and pets don’t cause problems. Most likely, each of these points needs to be addressed in a separate paragraph.

The writer could revise the topic sentence into two topic sentences:

- Being able to bring a dog or cat to the office can be comforting to people who work at a desk from 9:00-5:00.

- Specific policies and practices can eliminate some of the problems that might occur if employees are allowed to bring pets to the office.

These two paragraphs might appear in an essay arguing that people should be able to take their pets in public more often. The topic sentence would clearly support such a thesis, which would need many more paragraphs of support.

Typically, you should place the topic sentence at the beginning of the paragraph. In college and business writing, readers often lose patience if they are unable to quickly grasp what the writer is trying to say. Topic sentences make the writer’s basic point easy to locate and understand.

Developing the Topic Sentence

The body of a paragraph contains supporting details to help explain, prove, or expand the topic sentence. Often, in attempting to support a topic sentence with plenty of supporting details, writers discover that they need two paragraphs to support one point. For example, consider the following topic sentence, which might appear in an essay about reforming social security.

For many older Americans, retiring at 65 is not option.

Supporting sentences could include a few of the following details:

- Fact: Many families now rely on older relatives for financial support.

- Reason: The life expectancy for an average American is continuing to increase.

- Statistic: More than 20 percent of adults over age 65 are currently working or looking for work in the United States.

- Quotation: Senator Ted Kennedy once said, “Stabilizing Social Security will help seniors enjoy a well-deserved retirement.”

- Example: Last year, my grandpa took a job with Walmart because he was forced to retire early.

The personal example might be something the writer wants to expand upon in a separate paragraph, one that tells a short story about the grandfather’s decision to go back to work after retiring. The point, however, would be expressed in the topic sentence from the previous paragraph.

Sometimes, though, the topic sentence presents one idea but in presenting the supporting details, the writer gets off topic. A topic sentence guides the reader by signposting what the paragraph is about, so the rest of the paragraph should relate to the topic sentence. Can you spot the sentence in the following paragraph that does not relate to the topic sentence?

Health policy experts note that opposition to wearing a face mask during the COVID-19 pandemic is similar to opposition to the laws governing alcohol use. For example, some people believe drinking is an individual’s choice, not something the government should regulate. However, when an individual’s behavior impacts others–as when a drunk driver is involved in a fatal car accident–the dynamic changes. Seat belts are a good way to reduce the potential for physical injury in car accidents. Opposition to wearing a face mask during this pandemic is not simply an individual choice; it is a responsibility to others.

If you guessed the sentence that begins “Seat belts are” doesn’t belong, you are correct. It does not support the paragraph’s topic: opposition to regulations. If a point isn’t connected to the topic sentence, the writer should tie it in or take it out. Sometimes, the point needs to be included in another paragraph, one with a different topic sentence.

Concluding Sentences

A strong concluding sentences draws together the ideas raised in the paragraph and can set the readers up for a good transition into the next paragraph. A concluding sentence reminds readers of the main point without repeating the same words.

Concluding sentences can do any of the following:

- summarize the paragraph

- draw a conclusion based on the information in the paragraph

- make a prediction, suggestion, or recommendation about the information

For example, in the paragraph above about wearing face masks, the concluding sentence summarizes the key point: responsibility to others. The next paragraph in the essay might begin by stating something like, “Not all face masks, however, will protect people to the same degree.” The topic sentence connects the new point (which face masks are best at protecting others) with the point made in the previous paragraph (wearing face masks is a way to protect others).

Transitions

In a series of paragraphs, such as in the body of an essay, concluding sentences are often replaced by transitions. Transitions are words or phrases that help the reader move from one idea to the next, whether within a paragraph or between paragraphs. For example:

I am going to fix breakfast. Later, I will do the laundry.

“Later” transitions us from the first task to the second one. “Later” shows a sequence of events and establishes a connection between the tasks.

A transition can appear at the end of the paragraph or at the beginning of the next paragraph, but never in both places.

Look at this paragraph:

There are numerous advantages to owning a hybrid car. For example , they get up to 35 percent more miles to the gallon than a fuel-efficient, gas-powered vehicle. Also, they produce very few emissions during low speed city driving. Because they do not require gas, hybrid cars reduce dependency on fossil fuels, which helps lower prices at the pump. Given the low costs and environmental benefits of owning a hybrid car, it is likely that many people will buy hybrids in the future.

Each of the bold words is a transition. Transitions organize the writer’s ideas and keep the reader on track. They make the writing flow more smoothly and connect ideas.

Beginning writers tend to rely on ordinary transitions, such as “first” or “in conclusion.” There are more interesting ways to tell a reader what you want them to know. Here are some examples:

These words have slightly different meanings so don’t just substitute one that sounds better to you. Use your dictionary to be sure you are saying what you mean to say.

Paragraph Length

How long should a paragraph be? The answer is “long enough to explain your point.” A paragraph can be fairly short (two or three sentences) or, in a complex essay, a paragraph can be a page long. Most paragraphs contain three to six supporting sentences, but a s long as the writer maintains close focus on the topic and does not ramble, a long paragraph is acceptable in college-level writing. In some cases, even when the writer stays focused on the topic and doesn’t ramble, a long paragraph will not hold the reader’s interest. In such cases, divide the paragraph into two or more shorter paragraphs, adding a transitional word or phrase.