- Kid Reporter

- More Sports

- Subscribe to SI Kids Magazine

- Give the Gift of SI Kids Magazine

Fifi Garcia Is the 2023 SportsKid of the Year

Flipping Their Way into History: Morgan State Hosts Inaugural Acrobatics and Tumbling Meet

Allyson Felix Continues to Impact Sports World Away from the Track

Messi Mania Arrives in New Jersey

NHL Fan Fair and Kids Day: Tons of Fun for Hockey-Loving Kids!

The Hockey Celly vs. the Football Touchdown Dance

Boston Celtics Kid Day a Big Hit

Four Top Teams Provide Memorable Jimmy V Classic at MSG

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- Your Health

- Treatments & Tests

- Health Inc.

- Public Health

Living Better

Kids can't all be star athletes. here's how schools can welcome more students to play.

Selena Simmons-Duffin

Going into his last tennis match of the school year, high school senior Lorris Nzouakeu knew he might get knocked out in straight sets. He was scheduled for one of the first matches of the day during the regionals competition in western Maryland, against a student from another school who'd won the championship last year.

"So it wasn't really looking good at the start," he laughs. "My goal was definitely to continue rallies and maintain pace and also just have fun."

"Fun" is sometimes hard to find in high school sports. Gunning for college athletic scholarships, many students and families go all in – focusing on one sport and even one position from elementary school. It's also big business – the whole youth sports industry is worth $19 billion dollars, more than the NFL .

For a lot of kids of all ages, sports are not working for them. Less than half of kids play sports at all, and those that do only stick with it for about three years and quit by age 11 . That's a whole lot of kids missing out on some of the huge benefits of sports, including spacial awareness, physical activity, and team skills.

Increasingly sports educators, health researchers and parents are pushing back against this trend and arguing that playing sports should be for all kids.

During the last few pandemic years, physical activity fell, while obesity rates and mental health challenges grew, note Tom Farrey and Jon Solomon of the Aspen Institute Sports & Society Program in a 2022 handbook for reimagining school sports . At the same time, interest in sports has grown, which "presents an historic opportunity for schools to reimagine their approach to sports," they write.

Shots - Health News

How to cut back on junk food in your child's diet — and when not to worry.

But schools can create space for more types of students in sports. One example of what this looks like in practice is Nzouakeu's high school – Tuscarora High in Frederick County, Md. This school transformed its athletics program to prioritize including kids of all ability levels in sports. It's a model for handling youth sports, argues author and athlete Linda Flanagan , who highlighted the school in her book about youth sports entitled Take Back the Game .

Here's how Tuscarora High does things – plus some guiding principles for how schools can help include more kids in the fun of sports.

Lorris Nzouakeu played tennis for three years at Tuscarora High. He appreciate that his school "gives a lot of space for people to actually engage, even if they don't believe that they're the strongest... it gives plenty of opportunity to be able to grow into the sport." Selena Simmons-Duffin/NPR hide caption

Lorris Nzouakeu played tennis for three years at Tuscarora High. He appreciate that his school "gives a lot of space for people to actually engage, even if they don't believe that they're the strongest... it gives plenty of opportunity to be able to grow into the sport."

Offer a variety of sports to appeal to all tastes and talents

Tuscarora is a fairly big school with about 1,600 students – 40% white, a quarter Hispanic, a quarter Black. A third of students get free or reduced lunch.

Half of these students play a school sport, well above the national average of 39% participation. "That's awesome," beams Tuscarora's coordinator of athletics and facilities Chris O'Connor. "That speaks to the number of sports that we offer."

Frederick County schools, including Tuscarora, offer 17 different sports , including golf, swimming and lacrosse, and starting next year, girls flag football . It also has three unified teams, in which students with and without disabilities play together – Tuscarora's unified bocce team won Maryland's state championship this year .

Variety is key because not everyone loves playing football, basketball or baseball, notes Brian Culp , professor of health and physical activity leadership at Kennesaw State University.

"What can happen is that if you're in a school system where you, for instance, have a high amount of African-American students, and you say, 'Well, I'm going to provide basketball and I'm going to provide football,' – you've basically designed their destiny," he says. If a student isn't good at either of these sports or doesn't like it, he explains, they might feel like there's no place in sports for them.

Offering options like fencing or gymnastics can help students find what clicks. "There are things that impact what type of choices people make: Are they skiers? Are they swimmers? Are they runners?" Culp says he himself didn't play a varsity sport until his senior year, when he ran cross country.

Chris O'Connor leads athletics at Tuscarora High. He says it's important to let kids try a variety of sport. His own kids, a seventh-grader and a fourth-grader, both do three sports so "they can figure out what they like," he says. Selena Simmons-Duffin/NPR hide caption

Chris O'Connor leads athletics at Tuscarora High. He says it's important to let kids try a variety of sport. His own kids, a seventh-grader and a fourth-grader, both do three sports so "they can figure out what they like," he says.

Don't force kids – even star players – to specialize

Variety is also important for athletically gifted students to help them branch out, notes Flanagan.

"There's no end to the specializing," she says, of the trend in sports today. A parent may go beyond specializing their child in hockey, she says, to asserting: "My child's a goalie, and don't deviate from that because that's where you're going to make your mark."

She thinks this way of approaching sports robs them of the fun, while also increasing the risks of repetitive stress injuries and potentially limiting a child's identity. In her book she advises: no sports specializing before puberty.

Tuscarora's O'Connor agrees that specializing is a problem. "I think that's what's wrong with youth sports right now in America," he says. "I'm from the mindset that you should do as many different sports as possible because you don't know what you're going to like."

Worried about your kids' video gaming? Explore their online worlds yourself

Give kids of varying skill levels opportunities to play.

The school system today is geared toward channeling the top-performing young athletes toward collegiate and professional goals, says Flanagan. "If you're at a giant school and you're trying to make the basketball team, you are competing against four grades [worth of students] for five spots," she says. "So where does that leave the kid who's just like, 'Okay, I want to play, but I'm not fantastic'?

"The arms-race nature of it has really had such a terrible impact on kids who might ordinarily grow into it if they had space, they had time," she adds.

Not every family has the resources to develop kids' athletic talents when they're younger, and some kids don't discover an interest right away. For students like this, Tuscarora has low-key, non-competitive sports that students can play during the school day, explains O'Connor — and that have meets every few weeks.

"It's providing that opportunity for the student-athlete in the school day to just have some fun with the sport and be around an adult who knows something about it," he says.

Official school sports also help students who come in as beginners stick with it and get better, says Nzouakeu, the Tuscarora tennis player. He started as a sophomore, and his game has improved steadily, he says. "I know that when I play out there, I can definitely find out which skills I need to practice more and I can take that time to continue getting better."

Use school space and time creatively

School sports are often jammed in after a long day of sitting in classrooms. That's not the only way to do things, notes Flanagan.

"In Finland, after every 45 minutes, they have 15 minutes of recess," she says. "Just this idea of moving your body to clear your head – it's well-established in science that this is so essential for clear thinking and for emotional well-being, too."

She says recess isn't the only way to get physical activity during the school day – intramural and club sports can offer that same kind of outlet, if schools think creatively about space.

"Most gym and field space is not occupied all the time – field space in particular is typically for sports after school," she points out. Why not use that field during a flex period? Or get students scrimmaging in the gym?

To do this, says Culp, you need "a principal, a district that actively promotes physical movement as a part of the school day." He notes decades worth of research showing the benefits of physical activity for kids. "A physically, actively engaged child is a better learner in school," he says "Their self-esteem is high, their self-confidence is high, and their ability to actually deal with challenges in the world is better."

Tuscarora High in Frederick, Md. Selena Simmons-Duffin/NPR hide caption

PE classes have a good ratio of teacher to student

One challenge for students who aren't confident in their sports skills is that it can be intimidating to try to join in, says Culp, especially if there are a lot of students and only one teacher or coach.

It's like being in a city waiting for a subway. "That train comes through and you're just like, 'I don't know if I want to get on that subway car because it's packed,'" he says. If there are too many other students, some kids may feel they won't get enough support from the coach.

School leadership and school boards can support physical movement, Culp says, by instituting a manageable ratio of educators to students. This can encourage students without a lot of skills (or even reluctance) to feel like they can join in.

High school senior Lorris Nzouakeu says he enjoyed improving his tennis game during high school and he'll keep playing tennis recreationally in college. Selena Simmons-Duffin/NPR hide caption

High school senior Lorris Nzouakeu says he enjoyed improving his tennis game during high school and he'll keep playing tennis recreationally in college.

Keep things in perspective

Yes, there are benefits to sports, says Flanagan, but they are not for everyone. With children, "you can't force them to like school or like to read or when to do sports," says Flanagan. "They have to come to it on their own."

Modeling low-key outdoor play and enjoying sports is an important thing parents can do, she says. But Flanagan – who has coached cross country and track and seen the intensity some parents bring to their children's athletic endeavors – says it's important to let kids quit when they want to.

"I don't think forcing kids to play sports is a good idea," she says. "We have this distorted notion here about grit. Obviously grit is important. But I think we shouldn't make children stick with things just because it's a virtue to stick with things and who cares how miserable you are."

That includes young people who never really took to sports at all, and talented athletes who played seriously for years and then decide they've had enough.

And maybe if you give kids a choice, and let them play without having to be the best, they'll discover a life-long love of sport. Lorris Nzouakeu, who just graduated from Tuscarora High, lost his regionals tennis match 6-0, 6-0, but that didn't bother him too much. He says next year in college, he may play on an intramural tennis team, or just recreationally.

"I'd like to continue tennis in college because not only do I think of it as a great pastime, but I also think that it's something that I can just continue doing for myself," he says. "Something I can de-stress with as I continue living my life."

- school athletics

- youth sports

- Grades K-1 Articles

- Grade 2 Articles

- Grades 3-4 Articles

- Grades 5-6 Articles

- Earth Science

- Engineering

- Environment

- Food and Nutrition

- Movies and Television

- Music and Theater

- Service Stars

- The Human Body

- Transportation

- Young Game Changers

- Grade 4 Edition

- Grade 5-6 Edition

- For Grown-ups

- Also from TIME for Kids:

- user_age: none

The page you are about to enter is for grown-ups. Enter your birth date to continue.

United States

Messi in miami.

Lionel Messi is a famous soccer player. He led Argentina to a World Cup win in 2022. He played in France for the 2022–2023 season. Then he shocked the world. In June 2023, he made an announcement. He joined Inter…

Girls Skate

Sosina Challa lives in Ethiopia. That’s in Africa. One day, she saw some boys skateboarding. “I used to watch skateboarding in the movies,” Challa told TIME for Kids. “But I never got the chance to try.” That changed. “I just…

Sam Rapoport has a mission. She wants to connect women and girls with football. Rapoport works for the National Football League (NFL). She’s its senior director of diversity, equity, and inclusion. Rapoport grew up playing flag and touch football.…

Coco's Big Win

Coco Gauff is a Grand Slam tennis champion. On September 9, she won the 2023 U.S. Open. Gauff is its youngest American winner since Serena Williams. She’s only 19 years old. Some doubted that Gauff could win. “That just put…

The Slugger

Aaron Judge plays for the New York Yankees. He is baseball’s new home-run king. Judge hit a home run on October 4. That was his 62nd of the season. It broke a record for most home runs in a season.…

Scoring King

On February 7, LeBron James broke a record: He became the NBA’s all-time leading scorer. The record had been held by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar for 39 years. James plays for the Los Angeles Lakers. He made the shot against the…

Pickleball Craze

Pickleball mania has taken over the United States. The Sports & Fitness Industry Association called pickleball the fastest-growing sport in the U.S. About 5 million people were playing it in 2021. That’s nearly twice as many as in 2019. …

The Mother of Women's Judo

In 1959, Rena “Rusty” Kanokogi won a judo competition in New York. Her award was taken away. That’s because she was a woman. She had pretended to be a man to compete. Kanokogi set a goal to help women in…

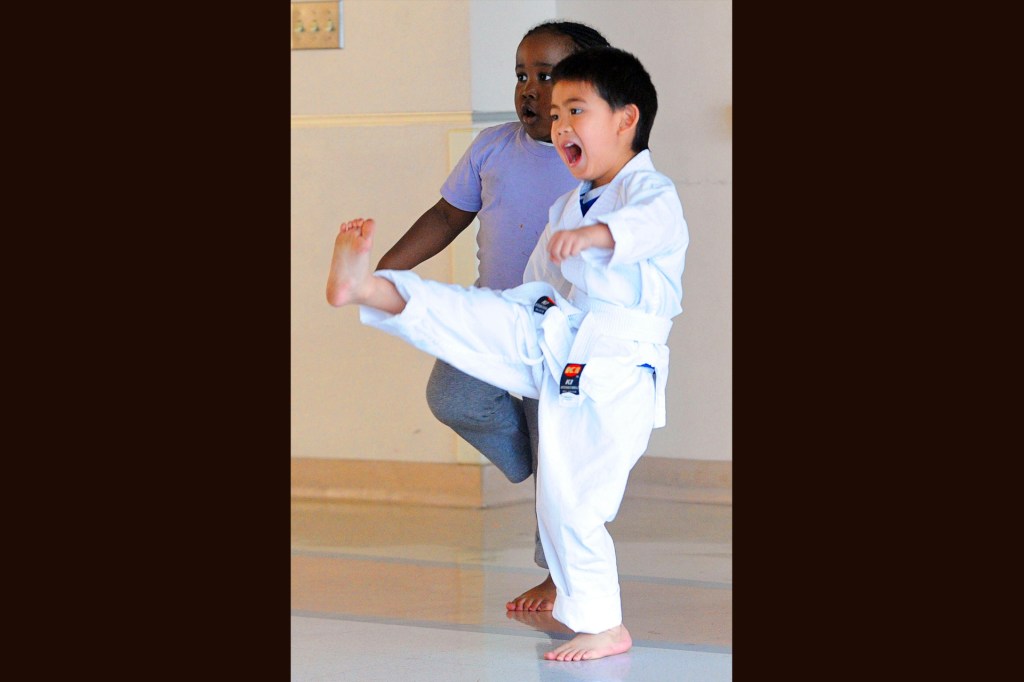

Martial Arts

Martial arts are fighting sports. Many started in Asia and were used in battle. Today, martial arts are popular with children. The sports help train the body and the mind. There are different types of martial arts. Learn about four…

The Greatest

Serena Williams is one of the greatest athletes of all time. She has played professional tennis for 27 years. Now, she has decided to step away from the game. What is next? Williams will focus on her business and on…

Should School Sports Prioritize Participation Over Competition? What a New Report Says

- Share article

High school sports play an important role in addressing students’ physical and mental health needs, but with fewer than 2 in 5 public high school students participating, the traditional model needs to be updated to serve more of them, a report this spring from the Aspen Institute says.

The Sport for All, Play for Life high school sports report proposes eight strategies to help principals and school leaders develop their students’ social and emotional skills through sports. A product of two years of research and input from more than 60 experts, the report envisions a school sports system with opportunities for every student. Increasing participation in sports can have lifelong ramifications, given that student athletes are more likely to be active as adults. It also comes as educators scramble to boost students’ socioemotional skills and reconnect them with their schools after years of pandemic-driven isolation and educational disruption.

“The current high school sports model doesn’t really work for enough students,” Jon Solomon, the editorial director of the Aspen Institute Sports & Society Program, said. “It’s largely based on trying to win games and scholarships, and playing for the school, and that’s still incredibly valuable and important, but there are many other students who are being left behind.”

“We believe that leaders should recognize that every student, regardless of their background or ability, has a right to play sports — and we don’t just mean a right to try out for a team,” he added.

Here are some steps school leaders can take to make school sports more accessible to their students:

Align school sports with student interests

Schools need to know what students want to participate in in order to design sport offerings that will raise participation. However, Jay Coakley, a sociologist at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs, who was one of the experts the Aspen Institute consulted during its reporting process, said youth sports today are “adult-oriented.”

“The developmental interests of children and the interests of children in their own movements have been ignored,” Coakley said. “It’s adult perspectives that create the leagues and all of the things that go along with it—run the practices, set the schedules—and children have no voice and their interests are either ignored or unknown.”

“A lot of the changes that have occurred have taken the act of playing out of the hands of kids and put it into the hands of adults,” he added. “I’m not against adult guidance, but that move is not good.”

This is because, according to Coakley, adults have different definitions of fun than students do. The number one reason high school students play sports is to have fun, according to the Aspen Institute report. Nearly two-thirds of surveyed students said they engage so they can play with and make new friends.

“Those are the first things that are eliminated in organized sports,” Coakley said.

For instance, in Little League baseball, Coakley said, a coach’s goal is to identify the pitcher on the team who will prevent batters from hitting the ball, which excludes the other players from fielding the ball.

“Everybody in the stands is telling them this is a perfect game, this is what you want. Meanwhile, the other seven players don’t field the ball,” Coakley said.

To gauge student voices, the Aspen Institute report suggests schools conduct annual student interest surveys with a common set of questions on students’ sport preferences, their rationale for participating or not, and youth/adult relationships in the context of sport that they give students. These surveys should also take note of respondents’ disability status, race, ethnicity, and grade level.

Give a variety of options for play

Intramural sports and club sports led by students can offer many of the same benefits as interscholastic competition including exercise, teamwork skills, mental health benefits, and a sense of belonging. These formats, while popular on college campuses, are often under-prioritized in high schools. However, when, for example, 75 students try out for varsity basketball, 15 make the team, and only 10 get significant playing time, these alternative opportunities to play can make a difference.

One way Dan Dejager, a physical education teacher at Meraki High school in Fair Oaks, Calif., keeps his students active outside of interscholastic programs is by differentiating his instruction based on his students’ needs, interests, and ability levels.

For example, instead of teaching his students how to line dance, Dejager has his class play Just Dance, a video game where players dance in sync with a virtual character to contemporary music.

“I think if you become more physically active, and you find activities that you enjoy doing that are meaningful to you, then that physical well-being, that emotional well-being, and mental well-being will come,” Dejager said.

The Aspen Institute suggests physical education teachers and athletic directors expand course offerings or connect students to community-based programs such as bike clubs and yoga classes given that, according to their findings, more than 1 in 3 students are interested in strength training, 1 in 4 want biking, and 1 in 5 want skateboarding, yoga, and dance.

Prioritize educating students over winning games

In most high schools, sports are seen as having different goals than academics, which tend to prioritize education. Coaches often think their main job is to win championships and therefore, they can focus resources on the best athletes, sometimes at the expense of other students who also want to play and would benefit from doing so.

Terri Drain, the president of the Society of Health and Physical Educators, who taught for 34 years and coached high school field hockey, said that in order to attract kids back to sports, there needs to be “quite a mind shift.”

“We need to talk about what the goal of school sports is,” Drain said. “Is it to prepare kids for their university sporting career and measure success when our students get drafted or scholarships? Or should how we measure success be by the number of students that participate?”

As students get older, more are cut from or drop out of sports. On average, kids quit playing sports by age 11, according to a survey by the Aspen Institute and the Utah State University Families in Sports Lab.

Drain envisions a school sports system in which “every child, no matter what their ability level,” can play, “not just for the elite children on the college path.”

To combat this, administrators should ensure that all sports activities map to a school’s vision of education, according to the Aspen Institute report. This could include crafting a symbiotic mission statement specific to the athletic department and holding sports personnel accountable to it through group discussions and performance reviews.

Increase education for coaches

Coaches often play a pivotal role in shaping a student’s ideas about health and education. In fact, 1 in 3 students said they play sports because of “a coach who cares about me,” according to the Aspen Report. However, many coaches’ training stops after their initial certification, and they lack the knowledge to make sports a healthy and positive experience for students. In surveys, nearly half of all students say they play sports for their emotional well-being and mental health, yet only six states require coaches to train in human development, development psychology and organization management.

The Society of Health and Physical Educators has developed national standards for sport coaches, the first of which is to “develop and enact an athlete-centered coaching philosophy.” In other words, sport coaches prioritize opportunities for athletes’ development over winning games.

Many coaches, according to Drain, coach the way they were coached as athletes. To break that cycle, schools need to provide professional development that helps physical educators teach with physical literacy in mind and with the attitude that all children have a right to learn.

The Aspen Institute says athletic directors should actively support effective behaviors of coaches through in-house teaching, required outside trainings, and coach networking. They should also hold coaches accountable to providing a positive experience for their athletes and growing the student retention rate.

Other ways the Aspen Institute said schools can make school sports more appealing and developmentally useful include having administrators craft personalized activity plans with students, requiring athletic trainers in schools that offer collision sports, defining athletic program standards for schools, and developing partnerships with community-based organizations.

Adam Lane, the principal at Haines City High School in Polk County, Fla., said that of all the report’s suggested strategies, “the most challenging” for schools is implementing the sports that most interest students.

“The reason is the feasibility of starting up a new program from the ground up when you don’t have any of the equipment or the facilities needed for it,” Lane said.

“Something like that cannot be done in a couple months,” he continued. “One because of the financial needs of all the equipment that is needed, but two, you also have to find a facility or a place to play and the school might not have it, the community not might not have it. There’s a lot of planning that goes into that.”

The Aspen Institute has yet to follow up with schools on their implementation of the playbook’s strategies, but they plan to, according to Solomon. For now, the institute will continue to promote its strategies and highlight the work of those that are bringing the organization’s vision to life.

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

How Sports Benefit A Student’s Life and Why Is It Important?

Donna paula.

- August 19, 2023

The popularity of sports in schools has been on the rise, with an increasing number of children actively participating in various athletic activities. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2020, an encouraging 54.1% of children engaged in sports. This growing trend highlights the importance of fostering discussions about physical well-being in students, as sports play a vital role in promoting their overall health and development.

This article will delve into the reasons behind the surge in sports participation and the significance of prioritizing physical well-being in the lives of young learners.

Why are sports important for students’ lives?

Sports are crucial for students’ lives as they instill discipline, time management, and resilience – essential qualities for academic and professional success. Through rigorous training and commitment, students learn discipline, a valuable skill in balancing studies and extracurriculars. Managing practice sessions, competitions, and academics teaches effective time management.

Moreover, facing challenges, victories, and defeats in sports fosters resilience, preparing students to handle setbacks in their academic and future professional pursuits. These experiences build character, confidence, and teamwork, shaping well-rounded individuals capable of navigating obstacles, adapting to change, and excelling in various spheres of life.

What are the physical health benefits of sports for students?

Sports offer numerous physical health benefits for students. Regular participation improves cardiovascular health, enhances muscular strength and endurance, and promotes flexibility and coordination. Engaging in physical activities helps maintain a healthy weight , reducing the risk of obesity-related issues. It also boosts bone density, reducing the likelihood of osteoporosis later in life.

Sports contribute to better immune function , reducing the occurrence of illnesses. Additionally, students who participate in sports are more likely to adopt a physically active lifestyle, which can lead to long-term health benefits and a decreased risk of chronic diseases such as diabetes and heart disease.

How do sports contribute to students’ mental and emotional well-being?

Beyond physical fitness, engaging in sports offers a myriad of psychological benefits that contribute to their overall mental health and emotional resilience.

Positive Impact of Sports on Mental Health and Stress Reduction

Participating in sports positively impacts students’ mental health by releasing endorphins , reducing stress hormones, and promoting a sense of achievement and self-worth. Regular physical activity in sports can alleviate symptoms of anxiety and depression, improve mood, and enhance cognitive function. Furthermore, the camaraderie and social support within sports teams foster a sense of belonging and emotional well-being, empowering students to navigate life’s challenges with greater resilience and a positive outlook.

Do sports have an impact on student’s academic performance?

The relationship between sports and academic performance has been a subject of interest among educators and researchers alike. Many studies suggest that sports can positively impact students’ academic achievements , as engagement in physical activities fosters skills and traits that are transferable to the academic realm.

How sports can enhance concentration, discipline, and time management skills

Participating in sports demands focus and concentration, which can improve students’ ability to concentrate during study sessions and exams. The commitment and dedication required in sports instill discipline, enabling students to adhere to study schedules and deadlines. Moreover, managing sports practice and academic commitments cultivates practical time management skills, helping students balance their athletic pursuits and academic responsibilities. These acquired skills and traits contribute to improved academic performance and overall success in their educational journey.

What social skills and personal development opportunities do sports provide for students?

Engaging in team sports and competitive activities can foster a range of interpersonal abilities essential for building solid relationships and navigating social situations effectively.

Exploring the social benefits of sports, such as teamwork, communication, and leadership

Participating in team sports cultivates essential social skills like teamwork, where students learn to collaborate and work cohesively toward a common goal. Effective communication is honed as players interact on and off the field, fostering understanding and cooperation.

Additionally, sports present leadership opportunities, empowering students to take charge, motivate others, and guide their teammates toward success. These social attributes not only enhance the sports experience but also carry over to various aspects of student’s personal and professional lives.

Fostering interpersonal relationships and community engagement through sports

Sports provide a platform for students to build lasting friendships and bonds, creating a sense of belonging and support within their teams. As they compete against other schools or communities, students develop a broader perspective, understanding diverse viewpoints and embracing inclusivity.

Furthermore, sports events and tournaments promote community engagement, bringing together families, friends, and supporters, fostering a collective spirit and a shared passion for sports. These experiences help students appreciate the value of community involvement and contribute to their personal development as empathetic, socially conscious individuals.

How can participating in sports teach students important values and life skills?

The experiences gained in sports, such as perseverance, sportsmanship, and goal setting, play a pivotal role in shaping their character and preparing them for future challenges.

Highlighting the values and life skills learned through sports, such as perseverance, sportsmanship, and goal setting

Sports provide a fertile ground for cultivating important values and life skills. Perseverance is developed as students encounter setbacks and learn to bounce back stronger. Sportsmanship instills respect for opponents and fair play, promoting integrity and empathy. Goal setting teaches students to work with dedication and discipline, fostering a growth mindset and determination to achieve both on and off the field. These invaluable qualities prepare students for success in various aspects of life, laying a strong foundation for personal growth and achievement.

How sports contribute to character development and preparing students for future challenges

Engaging in sports not only enhances physical abilities but also plays a significant role in character development. The challenges and triumphs experienced in sports teach students resilience, teaching them to overcome obstacles with fortitude. Learning to win gracefully and accept defeat with humility nurtures sportsmanship and a sense of fair competition.

Furthermore, the camaraderie and teamwork fostered through sports build social skills and the ability to collaborate effectively. These character-building experiences equip students with the tools needed to face future challenges, instilling confidence and a positive mindset that will serve them well in their academic, professional, and personal endeavors.

How can students balance sports and education effectively?

Balancing sports and education is a common challenge faced by students, as both demand significant time and dedication. Effectively managing these commitments is crucial to ensure academic success while reaping the numerous benefits that sports offer.

Tips and strategies for students to manage their time effectively between sports and academics

- Create a schedule: Develop a well-structured timetable that includes dedicated study hours and sports practice sessions. Organizing tasks in advance helps students allocate time efficiently, preventing last-minute rushes and reducing stress.

- Prioritize tasks: Identify academic assignments and exams that require immediate attention and focus on completing them first. Learning to prioritize helps students manage their time effectively, ensuring they fulfill their academic obligations without compromising their sports commitments.

- Utilize downtime efficiently: Make use of breaks between classes or during travel to review notes or complete quick academic tasks. These pockets of time add up and allow students to stay on top of their studies even during busy sports seasons.

- Communicate with coaches and teachers: Open communication with coaches and teachers is vital. Informing them about academic commitments and sports schedules can lead to better support and flexibility when necessary.

- Set realistic goals: Establish achievable short-term and long-term goals for both academics and sports. Realistic objectives keep students motivated and focused, leading to a more balanced approach.

- Learn time management techniques: Adopt effective time management techniques, such as the Pomodoro Technique, to improve productivity during study sessions and maintain energy levels during sports activities.

- Stay organized: Keep academic materials and sports gear well-organized to save time and reduce distractions when transitioning between sports and study sessions.

- Get enough rest and nutrition: Proper rest and a balanced diet are essential for peak performance in both sports and academics. Adequate sleep and nutrition help students stay alert, focused, and perform at their best in all areas of life.

- Seek support: Reach out to peers, coaches, or academic advisors for support and advice on managing sports and education. Sharing experiences and seeking guidance can be beneficial in finding effective solutions.

The importance of maintaining a healthy balance between sports and other responsibilities

Finding an equilibrium between sports and education is vital for students’ holistic development. While sports contribute to physical fitness, teamwork, and character-building, academic success remains a crucial foundation for future opportunities and career prospects.

Striking a balance ensures that students not only excel in sports but also perform well academically, opening doors to a wider range of possibilities. Furthermore, maintaining a healthy balance teaches students valuable life skills, such as time management, discipline, and adaptability, which are transferable to various aspects of their personal and professional lives. This balance also helps students avoid burnout and excessive stress, promoting overall well-being and fostering a positive outlook toward both their educational and athletic endeavors.

Ultimately, a harmonious blend of sports and education prepares students for future challenges, equipping them with a well-rounded skill set and a strong foundation for success.

What are the long-term benefits of sports in students’ lives?

Participating in sports during their formative years can have a lasting impact on student’s lives, extending far beyond their school days. The skills and values acquired through sports play a significant role in shaping their character and influencing their personal and professional journeys.

How the skills and values acquired through sports continue to benefit students in their personal and professional lives

- Discipline and Time Management: The discipline and time management skills cultivated in sports become ingrained habits that students carry forward into adulthood. Whether it’s meeting work deadlines, balancing family responsibilities, or pursuing personal goals, the ability to manage time efficiently proves invaluable in maintaining a successful and fulfilling life.

- Resilience and Perseverance: Sports often involve facing challenges, setbacks, and failures. Learning to bounce back, stay motivated, and strive for improvement instills resilience and perseverance. These traits enable individuals to navigate the ups and downs of life, tackle obstacles with determination, and ultimately achieve their ambitions.

- Teamwork and Leadership: The teamwork and leadership experiences gained through sports carry over into various aspects of professional life. Working collaboratively, communicating effectively, and motivating others are all vital skills in a team-oriented workplace. For those in leadership positions, the ability to inspire, delegate, and make strategic decisions stems from the foundations laid in their sports endeavors.

- Stress Management and Well-being: Sports offer a healthy outlet for stress relief, promoting mental well-being. Engaging in physical activity as a lifelong practice contributes to better physical health, reducing the risk of chronic illnesses. Regular exercise releases endorphins, fostering a positive mood and overall emotional balance.

- Networking and Social Skills: Participating in sports introduces students to a diverse range of individuals, from teammates to coaches, opponents, and spectators. Building strong interpersonal relationships and networking are essential in both personal and professional life, opening doors to opportunities and connections.

- Healthy Lifestyle: The value of maintaining a healthy lifestyle, learned through sports, remains relevant throughout life. Students who develop a love for physical activity are more likely to continue engaging in exercise and recreational sports as adults, reducing the risk of health issues and promoting longevity.

Participating in sports offers a wealth of long-term benefits that extend well beyond the playing field. For students, the skills and values acquired through sports form a strong foundation for personal and professional growth, fostering resilience, discipline, and teamwork. As parents and students, embracing the opportunities sports provide can pave the way for a healthier, more fulfilling life, promoting overall well-being and a brighter future filled with countless possibilities. Embrace the power of sports, and embark on a journey of holistic development and lasting success.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do sports and fitness affect students’ life.

Sports and fitness positively impact students’ lives by promoting physical health, building discipline, enhancing teamwork, fostering mental well-being, and instilling valuable life skills.

Why sports are important in youth development?

Sports are crucial in youth development as they promote physical fitness, teamwork, discipline, resilience, and social skills, nurturing well-rounded individuals for a successful future.

What is the importance of sports development programs in schools?

Sports development programs in schools are essential as they enhance physical fitness, teach life skills, build teamwork, boost confidence, and cultivate a healthy competitive spirit, contributing to students’ overall growth and success.

How can you encourage youth to participate in sports?

Encourage youth to participate in sports by highlighting the fun, camaraderie, health benefits, and opportunities for personal growth and achievement that sports offer.

Why is physical fitness important to students, and how will it impact your academic performance?

Physical fitness is vital for students as it improves concentration, memory, and cognitive function, leading to better academic performance. Regular exercise also reduces stress, enhances mood, and boosts overall well-being, creating a positive impact on learning and achievement.

About the Author

Latest posts.

Tips for Scuba Diver Beginners

Why You Need to Join a Golf Association

How to Play Pool A Beginners Guide

How Long Are Basketball Games on Average?

Dive deeper.

Activewear to Everyday Wear: How to Perfect the Relaxed Style

Sports: Take Them up with 3 Basic Skills

Sports Stars and the Sharks That Hound for Blood

F1 Pit Crew: The Greatest Secretaries in the World

Quick links.

- Contact Us Today

- Privacy Policy

Get in Touch!

- Middle School

- High School

- College & Admissions

- Social Life

- Health & Sexuality

- Stuff We Love

- Meet the Team

- Our Advisory Board

- In the News

- Write for Your Teen

- Campus Visits

- Teen College Life

- Paying for College

- Teen Dating

- Teens and Friends

- Mental Health

- Drugs & Alcohol

- Physical Health

- Teen Sexuality

- Communication

- Celebrity Interviews

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Frontiers for Young Minds

- Download PDF

How Sports Can Prepare You for Life

Sports are fun activities that help kids learn skills, like how to shoot a free throw or skate backwards. But what if sports could teach us more than physical skills and prepare us for life? If the environment is safe and welcoming, sports can also teach us skills that we can use in our lives— life skills ! Participating in sports can teach us about teamwork, being a leader, how to relax if we are upset, and much more! In this article, we discuss different ways that life skills can be developed through sports. We also talk about what you and your coaches can do to help you develop life skills. As you learn these skills in sports, you can use them anywhere, like at school or home. Life skills learned in sports can help you become a good person on whatever path you choose in life.

How Sports Can Prepare You For Life

Sports can be fun activities that help kids to learn different skills, like how to shoot a free throw, skate backwards, or hit a fastball. But what if sports can teach us more than physical skills? What if they can prepare us for life? Kids across the world engage in different types of organized sports, whether at school or in their communities. This makes sports an important context to help prepare kids for life. You might have heard the phrase “sports build character” before. Building positive character does not always happen by accident. It requires hard work from the kids participating, but also from their coaches and teammates.

Coaches play an important role in sports. If coaches make sports safe and welcoming, kids can have fun, learn new skills, and be part of a team or club. If coaches do not structure sports well, sports can lead to negative things, like not having fun, cheating, or bullying. In this article, we discuss how coaches can help kids learn life skills through playing sports.

What are Life Skills?

If the sports environment is safe and welcoming, sports can teach kids skills they can use in their lives— life skills ! Life skills means different things to different people. Sometimes people use words like values, assets, lessons, or character traits. In this article, we will call them life skills. Within sports, life skills can include:

- Respect : showing consideration and being kind to people (teammates, opponents, referees) and things (rules of the sport, equipment, sports facility);

- Honesty : always telling the truth to yourself and others;

- Teamwork : working together as a group to achieve a goal;

- Emotional regulation : having control over your emotions and staying calm; and

- Perseverance : always trying your best and never giving up.

You may learn about some of these skills at school, when you are working on a group project, or at home, from your parents and family. Learning life skills in many different contexts is an important part of your development. Developing life skills is a process , which means they take time and practice to develop. Sports can be one part of the process of developing life skills. Life skills can be learned, practiced, and improved upon in any sport, whether team or individual. Yet, for these skills to be called life skills, kids need to transfer these skills. Life skills transfer means that life skills learned in sports are used in other areas of your life, like at school, at home, or in other sports or activities [ 1 ].

Why is it Important to Develop Life Skills?

You may be asking yourself why developing life skills is important. Learning and practicing life skills in sports can help you be a good teammate and player, but they can also help you to be a good person outside of sports. Even if you do not become a professional athlete or play sports your whole life, you can still use life skills in other contexts. For example, learning relaxation techniques can be very helpful in sports. When stepping up to the plate for your first pitch in cricket or standing on the basketball free-throw line, you can learn different ways to relax, such as taking deep breaths or calming your mind by counting to five. Learning about relaxation techniques in sports can also help when you feel nervous or anxious at school. Before a test, you can take deep breaths to relax and calm your nerves. If you get into an argument with a friend or sibling, relaxation techniques, like deep breathing, can also help you act calmly, so you choose your words carefully and come to a peaceful solution.

How Can I Develop Life Skills in Sport?

There is a lot to focus on while playing sports—the rules, your position—without thinking about life skills. But do not worry; you do not have to go through this process on your own! As mentioned, coaches are important in helping kids develop life skills when playing sports. Life skills can be developed through sports in two different ways.

First, life skills can be developed based on how the sport is structured, including the rules, competition, and relationships developed with coaches and teammates [ 2 ]. In this implicit approach , coaches focus mainly on teaching sport-specific skills, like passing and shooting. They do not place any specific effort on discussing or practicing life skills. In cheerleading, kids can learn to communicate with their teammates during a routine. In golf, kids can learn to be respectful through the rules about respecting the course and one’s opponents. In these examples, coaches are not doing anything specific to support the development of life skills. Essentially, if coaches use this implicit approach, they leave life skills learning in sports up to chance.

Second, life skills can also be developed explicitly [ 2 ]. This explicit approach occurs when coaches take specific steps to teach kids life skills. There are different ways for coaches to teach life skills through sports. Below, we give an example of Coach Jane using an explicit approach during a handball practice or competition. This approach has five steps. First, Jane picks one life skill to teach—leadership. The theme of the entire session is to learn how to be a leader. Second, Jane works with players to define that life skill. Together, they come up with a definition of what it means to be a leader in handball, at home, and at school. Third, Jane gives players opportunities to practice being leaders during the session, including asking them to lead the warm-up or to act as the team captain. Jane provides feedback while they practice being leaders. She asks players to consider if their way of leading includes all of their teammates. Fourth, Jane finishes the session by reviewing the chosen life skill. She asks players questions like, “What activities required you to be a leader in today’s session?” and “Where else can you be a leader beyond handball?” Together, Jane and the players talk about how they can be leaders at home, at school, and even at work as they get older. The point of these discussions is for players to develop connections between their sports experiences and their lives outside of sports. Finally, Jane can provide opportunities for players to practice the life skills learned in handball in other contexts. As mentioned earlier, this is called life skills transfer. For example, to practice transferring leadership, Jane arranges for the players to lead activities at a younger team’s practice. Jane also works with the players’ teachers and parents to encourage players to practice being leaders in school, at home, or in other extracurricular activities, like mentoring a classmate who is struggling with their math homework. Overall, Coach Jane explicitly supports players’ leadership skills, within and beyond handball.

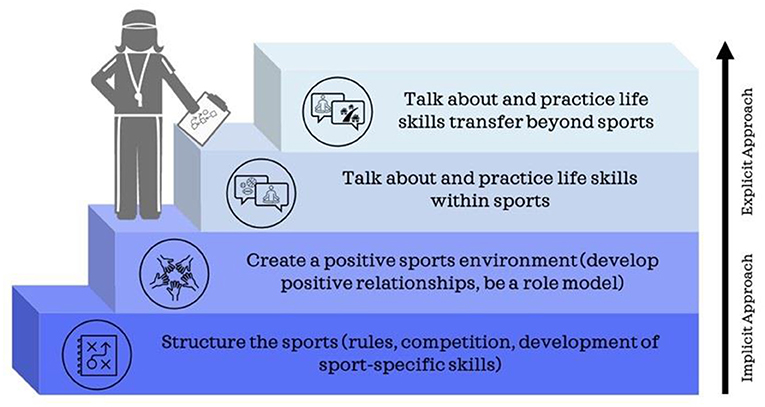

Researchers have found that using a combination of implicit and explicit approaches is most useful for kids to learn life skills in sports ( Figure 1 ) [ 4 ]. When coaches use both approaches, kids can have more opportunities to develop life skills based on how the sports environment is structured and what kinds of skills coaches choose to teach. Coach Jane supports her players’ leadership development by using the five steps outlined above (explicit approach), along with strategies like being a role model and setting clear rules about playing fairly (implicit approach). Research shows that using both approaches can help to increase kids’ awareness of how to transfer their life skills and strengthen their abilities for life skills transfer beyond sports, like at home and at school [ 5 ]. For example, if a player sees a classmate being bullied by a peer at school based on their gender identity or skin color, the player can transfer his or her leadership skills developed in sports by standing up for that classmate and leading the conversation toward kindness and inclusion rather than bullying.

- Figure 1 - We can imagine coaches who use implicit and explicit approaches as climbing a staircase.

- The first two steps represent the implicit approach, and the last two steps represent the explicit approach. Coaches need to climb the stairs in order to explicitly teach life skills. The stairs build on each other—to be on stair three, coaches need to also be using strategies from stairs one and two. This allows coaches to use a combination of implicit and explicit approaches for teaching life skills (Image credit: adapted from [ 3 ]).

So Now You Know!

In this article, we talked about ways sports and coaches can help you develop important skills that you can use in life. These life skills, like respect, leadership, and honesty, can improve your ability to perform in sports, but they also go beyond sports. What is important to remember is that YOU, as the athlete, also play an important role in this learning process. First, think about the different skills you are learning in sports. What are they? Look for important connections between your sport and your life in school or at home. Second, take initiative and use your life skills without your coach having to ask you. Stand up for a teammate who is being bullied or try to focus while waiting to receive a serve in tennis. Third, keep these skills in mind as you grow up. As you go to high school or secondary school and work your first job, there may be different life skills that are useful for you to transfer from your sports experiences. So, next time you are about to give a big class presentation, think about what you did on the court or field to help you relax and prepare. Practicing these life skills in sports and life can help you be a good athlete and a good person, on whatever path you choose in life.

Life Skills : ↑ Values, assets, or skills that help us in life. They can include respect, honesty, teamwork, emotional regulation, perseverance, and many more.

Life Skills Transfer : ↑ The process in which the life skills learned in sports are applied in other areas of a kid’s life, like at school, at home, in other sports, or in their community.

Implicit Approach : ↑ An approach to teaching life skills in which coaches focus on teaching sport-specific skills, without placing any specific effort on teaching life skills or providing time to practice life skills.

Explicit Approach : ↑ An approach to teaching life skills that occurs when coaches take specific steps to teach kids life skills.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

[1] ↑ Gould, D., and Carson, S. 2008. Life skills development through sport: Current status and future directions. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1:58–78. doi: 10.1080/17509840701834573

[2] ↑ Turnnidge, J., Côté, J., and Hancock, D. J. 2014. Positive youth development from sport to life: Explicit or implicit transfer? Quest 66:203–217. doi: 10.1080/00336297.2013.867275

[3] ↑ Bean, C., Kramers, S., Forneris, T., and Camiré, M. 2018. The implicit/explicit continuum of life skills development and transfer. Quest . 70:456–470. doi: 10.1080/00336297.2018.1451348

[4] ↑ Holt, N., Neely, K. C., Slater, L. G., Camiré, M., Côté, J., Fraser-Thomas, J., et al. 2017. A grounded theory of positive youth development through sport based on results from a qualitative meta-study. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 10:1–49. doi: 10.1080/1750984X.2016.1180704

[5] ↑ Bean, C., and Forneris, T. 2016. Examining the importance of intentionally structuring the youth sport context to facilitate positive youth development. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 28:410–425. doi: 10.1080/10413200.2016.1164764

- Quick Links

- Make An Appointment

- Our Services

- Price Estimate

- Price Transparency

- Pay Your Bill

- Patient Experience

- Careers at UH

Schedule an appointment today

- Babies & Children

- Bones, Joints & Muscles

- Brain & Nerves

- Diet & Nutrition

- Ear, Nose & Throat

- Eyes & Vision

- Family Medicine

- Heart & Vascular

- Integrative Medicine

- Lungs & Breathing

- Men’s Health

- Mental Health

- Neurology & Neurosurgery

- Older Adults & Aging

- Orthopedics

- Skin, Hair & Nails

- Spine & Back

- Sports Medicine & Exercise

- Travel Medicine

- Urinary & Kidney

- Weight Loss & Management

- Women's Health

- Patient Stories

- Infographics

The Benefits of Being a Multi-Sport Athlete for Kids

March 21, 2024

With a young athlete who excels at a particular sport, there often is temptation to commit to that sport only, which sometimes means training and participating year round.

But young athletes benefit physically and mentally by participating in different sports in different seasons, with time off for rest.

Playing different sports makes for a more well-rounded athlete and also reduces risk of psychological stress, burn-out and overuse injuries, says University Hospitals orthopedic surgeon Jacob Calcei, MD .

Dr. Calcei says specializing in one sport doesn’t necessarily enhance performance in that sport, or lead to athletic scholarships.

“A lot of the best athletes in pro sports and at the college level played multiple sports in high school,” Dr. Calcei says. “Diversifying makes you a better, more well-rounded athlete, and makes you better at your primary sport.”

Risk of Overuse Injuries

Increased training and competition associated with sports specialization at an early age is a major concern. Young athletes need time off so their bodies can recover, but they often don’t get it.

“Athletes at the highest level get an off-season to rest and recover, and it’s important that our young athletes have time to rest and recover as well,” Dr. Calcei says.

A 2020 study in the Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine found that athletes between 7 and 18 years old, particularly female athletes, are at higher risk for overuse injuries if they specialize in a single sport. Injury risk corresponded with hours spent training and performing.

Overuse injuries can impact bones, muscles, tendons and ligaments. The risk of these injuries can be decreased by diversifying sports and allowing proper rest and recovery, Dr. Calcei says. Sports specialization is especially risky in children younger than high school age, whose bones are still developing.

“Once you’re at the high school level it’s safer, but it still leads to increased risk of injuries and it doesn’t necessarily benefit athletic performance.”

Another study in 2019 noted that injury risk depends on the type of sport and level of specialization. Kids participating in Individual sports such as gymnastics and tennis are more likely to be highly specialized at younger ages than kids in team sports. The individual sports require higher levels of training and likely carry higher risk of overuse injuries.

But team sports such as baseball also feature early specialization, which has led to a rash of elbow and shoulder injuries from excessive throwing, Dr. Calcei says.

A rise in baseball overuse injuries led to the Ohio High School Athletic Association in 2017 to regulate pitch counts (125 pitches a day maximum) and days off between pitching appearances.

Risk of Burn Out

In the long run, rather than leading to scholarships and pro sports, intensive specialization drives a lot of young people to quit.

“We love sports and they play a big role in a young person’s life,” Dr. Calcei says. “But you don’t want kids to lose the joy. Making sports fun, something they enjoy and want to keep doing is important. Making it a chore is not fun, and it poses physical, mental and emotional risks.”

Playing different sports also has social benefits. Kids bond with a more diverse groups of peers, experience different coaches and learn to play different roles on a team.

Related Links

The pediatric sports medicine experts at University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children’s are dedicated to treating athletes of any age – from toddlers to adolescents and young adults.

Tags: Pediatric sports medicine , Jacob G. Calcei, MD

Articles on Sports

Displaying 1 - 20 of 503 articles.

For over a century, baseball’s scouts have been the backbone of America’s pastime – do they have a future?

H. James Gilmore , Flagler College and Tracy Halcomb , Flagler College

March Madness: The stars of women’s NCAA basketball face high expectations as the sport grows

Nwakerendu Waboso , Brock University and Taylor McKee , Brock University

‘The Amazon of Sports’ has already cornered baseball’s apparel market – and is now on the verge of subsuming baseball cards, too

Nathaniel Grow , Indiana University ; John Holden , Oklahoma State University , and Marc Edelman , Baruch College, CUNY

Celebrities, influencers, loopholes: online gambling advertising faces an uncertain future in Australia

Gianluca Di Censo , University of Adelaide and Paul Delfabbro , University of Adelaide

Why March Madness is a special time of year for state budgets

Jay L. Zagorsky , Boston University

What happens to F1 drivers’ bodies, and what sort of training do they do?

Dan van den Hoek , University of the Sunshine Coast ; Justin Holland , Queensland University of Technology , and Paul Haines , Griffith University

Recovering after a false start? What’s the state of play for Brisbane’s 2032 Olympic and Paralympic planning?

Leonie Lockstone-Binney , Griffith University ; Judith Mair , The University of Queensland ; Kirsten Holmes , Curtin University , and Paul Burton , Griffith University

40 years ago, the Supreme Court broke the NCAA’s lock on TV revenue, reshaping college sports to this day

Jared Bahir Browsh , University of Colorado Boulder

Sam Kerr’s racially aggravated harassment charge puts Football Australia in a tricky place

Tracey Holmes , University of Canberra

Caitlin Clark’s historic scoring record shines a spotlight on the history of the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women

Diane Williams , McDaniel College

Sporting change: How an elite swim club in Western Canada is addressing bullying

Julie Booke , Mount Royal University

Violence prevention can transform Canadian hockey culture — but only if implemented properly

Maddie Brockbank , McMaster University

Lamar Jackson is the NFL’s MVP. He’s also the NFL’s most valuable negotiator.

Ryan Clutterbuck , Brock University and Michael Van Bussel , Brock University

Higher, faster: what influences the aerodynamics of a football?

Giuseppe Di Labbio , École de technologie supérieure (ÉTS)

Could flag football one day leapfrog tackle football in popularity?

Josh Woods , West Virginia University

Children’s high-impact sports can be abuse – experts explain why

Eric Anderson , University of Winchester ; Gary Turner , University of Winchester , and Keith Parry , Bournemouth University

Students with disabilities often left on the sidelines when it comes to school sports

Megan MacDonald , Oregon State University

Norman Jewison’s ‘Rollerball’ depicted a world in which corporations controlled all information – is this dystopian vision becoming reality?

Matthew Jordan , Penn State

Suffering in silence: Men’s and boys’ mental health are still overlooked in sport

Michael Kehler , University of Calgary and Gabriel Knott-Fayle , University of Calgary

Sleep can give athletes an edge over competitors − but few recognize how fundamental sleep is to performance

Joanna Fong-Isariyawongse , University of Pittsburgh

Related Topics

- International Olympic Committee (IOC)

- Listen to this article

Top contributors

Knight Chair in Sports Journalism and Society, Penn State

Professor of Sport Management, University of Michigan

Assistant Professor, Sport Management, Brock University

Associate Professor, Manchester Metropolitan University

Professor of Sport and Geopolitical Economy, SKEMA Business School

Professor of Sociology, West Virginia University

Chair of Sport and Head of the Academy of Sport, The University of Edinburgh

Associate Professor of Markets, Public Policy and Law, Boston University

Professor of Physics, University of Lynchburg

Assistant Professor, Kinesiology, Western University

Emeritus Professor of Communication, Saint Xavier University

Professor of Communications, Howard University

Senior lecturer in Screen Media, Victoria University

Professor of Journalism, Indiana University

Professor Emerita of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education, University of Toronto

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Open Access J Sports Med

Youth sport: positive and negative impact on young athletes

Donna l merkel.

Bryn Mawr Rehabilitation Hospital, Main Line Health System, Exton, PA, USA

Organized youth sports are highly popular for youth and their families, with approximately 45 million children and adolescent participants in the US. Seventy five percent of American families with school-aged children have at least one child participating in organized sports. On the surface, it appears that US children are healthy and happy as they engage in this traditional pastime, and families report higher levels of satisfaction if their children participate. However, statistics demonstrate a childhood obesity epidemic, with one of three children now being overweight, with an increasingly sedentary lifestyle for most children and teenagers. Increasing sports-related injuries, with 2.6 million emergency room visits a year for those aged 5–24 years, a 70%–80% attrition rate by the time a child is 15 years of age, and programs overemphasizing winning are problems encountered in youth sport. The challenges faced by adults who are involved in youth sports, from parents, to coaches, to sports medicine providers, are multiple, complex, and varied across ethnic cultures, gender, communities, and socioeconomic levels. It appears that an emphasis on fun while establishing a balance between physical fitness, psychologic well-being, and lifelong lessons for a healthy and active lifestyle are paramount for success.

Introduction

The popularity of youth sports continues to rise, with an estimated 45 million child and adolescent participants in the US. 1 , 2 Seventy-five percent of US families with school-aged children have at least one child who participates in organized sports. 3 , 4 Unfortunately, the framework which provides guidelines, rules, and regulations for youth sports has been established with very little scientific evidence. 5 Even basic commonsense parameters for sports safety are not implemented or followed. Vague descriptions of age of participants, hours and structure of practice, and rules for competition vary between sports. Less than 20 percent of the 2–4 million “little league” coaches and less than 8% of high school coaches have received formal training. 6 Each year approximately 35% of young athletes quit participation in sport, and whether an athlete returns to participation at a later date is unknown. 7 , 8 Sports attrition rates are the highest during the transitional years of adolescence, when outside influences have the most impact. By the time children are 15 years of age, 70%–80% are no longer engaged in sport. 1 , 8

According to physical, psychological, and cognitive development, a child should be at least 6 years of age before participating in organized team sport, such as soccer and baseball. 7 Further, an accurate assessment of each child’s individual sports readiness should be performed to assist in determining if a child is prepared to enroll and at which level of competition the child can successfully participate. A mismatch in sports readiness and skill development can lead to anxiety, stress, and ultimately attrition for the young athlete. 7 , 8 For the very young “athlete”, the goals of participation are to be active, have fun, and to have a positive sport experience through learning and practice of fundamental skills. 9 , 10 An introduction to a variety of activities has been shown to be both physically and psychologically beneficial for the youngster. 7 Sports satisfaction surveys reveal that “having fun” is the main reason that most children like to participate in sports; however, the parents perception of why their children like to play sports is to “win”. 5 , 6 , 10 , 11 The Institution for the Study of Youth Sports looked at the importance of winning from the child’s perspective, and found that it varied with gender and age, but for the majority of younger children, fairness, participation, and development of skills ranked above winning. 12 It appears that this disconnect amongst young athletes and adults may contribute to stress and unhappiness on the part of the child. Perhaps the adult interpretation of “little league” or “pee wee” sports as a mini-version of adult sports competition has led those who are involved in governing these activities down the wrong path, where winning overrides the fundamentals of youth sports, an outline of which is provided in Table 1 . Implementation of some of the coaching tactics that were designed for college and professional athletes, such as hard physical practices for punishment, only the best get to play, running up the score, and overplaying celebratory wins has contributed to a negative atmosphere in youth sports.

Fundamentals of youth sports

Although the state of affairs of youth sports in the US may be alarming, the alternative of a sedentary lifestyle and childhood obesity is a price we cannot afford. Over the past three decades, the incidence of obesity in children has tripled, with one of every three children being affected. 13 – 15 Significantly higher rates are noted in the African-American and Hispanic communities. 13 – 15 This current health problem in the US has long-term health consequences, including diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, cancer, asthma, musculoskeletal dysfunction, and pain. 13 – 15 The evolutionary changes in our society over the last 30 years, ie, technology, increasing crime rates, two income households, the national financial crisis, isolated suburban neighborhoods, and fast food, has facilitated a sedentary lifestyle with the consumption of high caloric foods. This imbalance of calories consumed and energy expenditure has contributed to an increased body mass index and obesity in our society. 16 The decline in physical activity has been attributed to increased use of car transport to and from school, an abundance of time spent in front of screens, and limited access to recess, physical education, and after-school programs. 5 , 13 , 17 Time spent outdoors engaging in traditional pickup games of “kick the can”, “dodge ball”, “kick ball”, and “stick ball” are replaced with an average of 7.5 hours per day of screen time for children aged 8–18 years. 5 , 13

This paper examines the positive and negative aspects of youth sports in the US. Controversial topics, such as early specialization, identification of elite players, influence of trained and untrained coaches, increasing injury rates, and moral issues of character and sportsmanship are discussed. It is clearly apparent upon investigation of the strengths and weaknesses of youth sports that resolutions promoting a better, safer, and healthier future for all US children lies in partnership of involved adults, from parents, who lay the foundation of moral principles, to politicians, who support legislation and funding for positive sports initiatives.

Positive impact

The perceived and objective benefits of participation in sports for children and adolescents are numerous and span multiple domains, including physical, physiological, and social development. First and foremost, participation in sports fosters vigorous physical activity and energy expenditure. In 1999, the Centers for Disease Control reported that only 50% of youth engaged in regular exercise, illustrating the need for school and community organizations to promote and facilitate physical activity. 14 In a more recent study by Troiano et al, only 42% of elementary school children undertook the recommended daily amount of physical activity, and only 8% of adolescents met this goal. 18 Research has shown that childhood obesity is a good predictor of adult obesity, 5 , 19 and it is estimated that one third of children born in the years 2000 and beyond will encounter diabetes at some point in their lives. 13 Organized sports have been shown to assist in breaking the vicious cycle of inactivity and unhealthy lifestyle by improving caloric expenditure, increasing time spent away from entertainment media, and minimizing unnecessary snacking. The chaotic lifestyles of working parents have facilitated an increase in consumption of “meals on the go”, which are often higher in calories, fats, and sugars. The average American now consumes 31% more calories, 56% more fat, and 14% more sugar than in previous years. 13

Organized sports comply with Michelle Obama’s initiative “Let’s Move!” to combat childhood obesity by fulfilling the recommended physical activity requirements for children of 60 minutes a day, 5 days a week, for 6 of 8 weeks. 13 , 14 In addition to promoting movement, youth sports provide a venue for learning, practicing, and developing gross motor skills. 7 , 17 Successful acquisition of a motor skill at a young age improves the likelihood of future participation in that activity in adulthood. 17 In 2010, the Centers for Disease Control reported a positive correlation between students who participated in high levels of physical activity and improved academic achievement, decreased risk of heart disease and diabetes, improved weight control, and less psychologic dysfunction. 20 Conversely, children who are obese often experience a diminished quality of life, learning difficulties, decreased self-confidence, and social discrimination. 13 , 20 , 21 In a longitudinal study which looked at activity levels in the same children at 9 years of age and then again at 15 years of age, adolescent girls fell short of the recommended daily 60 minutes of activity at an earlier age than did boys. 5 Both genders showed a decrease in physical activity as they transitioned into adolescence. 5 Rates of participation in sports for suburban youth appear to be similar between boys and girls; however, urban and rural girls show significantly less activity than boys of similar residential status. 21 – 23 Further, girls of color from a variety of ethnic backgrounds report lower levels of activity compared with Caucasian girls and boys of the same age. 23 Often the reality of living in lower socioeconomic neighborhoods contributes to inactivity, with more limited access to organized sport programs and facilities. 21 – 23

In addition to influencing physical health and warding off the negative consequences of obesity, youth participation in sports can also impact other high-risk health-related behaviors for boys and girls. A 2000 study reported by Pate et al investigated the relationship between participation in sports and health-related behaviors in US youth. Both male and female athletes were more likely to eat fruit and vegetables, and less likely to engage in smoking and illicit drug-taking. 22 The frequency of binge drinking remained consistent between athletes and nonathletes of both genders. 22 Male athletes were also less likely than their nonathletic counterparts to sniff glue or carry a weapon. 22 Not all risky behaviors performed by adolescents were curbed with participation in sports, however, the majority of teenagers who participated in sports appeared to be less interested in taking health risks than nonathletes. The amount and type of risky behaviors engaged in by adolescent athletes and nonathletes have been shown to vary according to gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. 22

In 2009, The Woman’s Sports Foundation published an updated version of “Her Life Depends on It”, an evidence-based research project stressing the important role that physical activity and sports play in the lives of girls and women. 23 This report underscores the advantages in terms of health and well-being experienced by physically active girls. Promoting exercise in young females is crucial because the majority of girls do not undertake the recommended level of daily physical activity. 23 Positive health benefits for physically active young girls include a reduced risk for developing breast cancer, osteoporosis, heart disease, and obesity in the future. 23 Further, rates of teenage pregnancy, unprotected sexual intercourse, smoking, drug use, and suicide decrease with increasing physical activity and participation in sports. 22 , 23 Girls who participate in sports are less likely to be depressed, more likely to reach higher academic goals, and more likely to demonstrate improved self-confidence and body image. 21 , 23 , 24