25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- School Education /

Essay on Isaac Newton: The Father of Modern Science

- Updated on

- Mar 15, 2024

Did you know Isaac Newton almost gave up on his education before discovering the laws of motion? Born in 1642, Isaac Newton was an English mathematician , physicist , astronomer, and author who is widely recognized as one of the most influential scientists in history. He is known as the father of modern physics. He made significant contributions to various fields of science and mathematics, and his work laid the foundation for many scientific principles and discoveries. Let’s find out more about Isaac Newton with the essays written below.

This Blog Includes:

Things to keep in mind while writing essay on isaac newton, essay on isaac newton in 100 words, essay on isaac newton in 200 words, essay on isaac newton in 300 words.

Also Read – Essay on Chandrayaan-3

- Isaac Newton was born on 4th January 1643.

- He is famous for discovering the phenomenon of white light integrated with colours which further presented as the foundation of modern physical optics.

- He is known for formulating the three laws of motion and the laws of gravitation which changed the track of physics all across the globe.

- In mathematics, he is known as the originator of calculus.

- He was knighted in 1705 hence, he came to be known as “Sir Isaac Newton”.

Issac Newton was an English scientist who made some groundbreaking discoveries in the field of science and revolutionized physics and mathematics. revolutionized physics and mathematics. He formulated the three laws of motion , defining how objects move and interact with forces. His law of universal gravitation explained planetary motion. Newton independently developed calculus, a fundamental branch of mathematics.

Everybody knows Newton because of the apply story, in which he was sitting under a tree when an apple fell on him. His ‘Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica’ remains a cornerstone of scientific thought. Newton’s profound insights continue to shape our understanding of the natural world.

Also Read – Essay on Technology

Born in 1642, Isaac Newton is one of the most influential scientists of all time. His groundbreaking contributions in physics, astronomy and mathematics helped reshape the understanding of the natural world. Our science books mention Newton’s three laws of motion which brought a revolution in physics.

- Newton’s first law of motion, also known as the law of inertia, states that an object will stay at rest unless acted upon by an outside force.

- The second law of motion states that an object’s acceleration is produced by a net force that is directly proportional to the net force’s magnitude.

- The third law of motion states that every action has an equal and opposite reaction.

All these laws laid the foundation for classical mechanics, revolutionizing the way we comprehend the physical world. He is known as the father of modern physics.

In mathematics, Newton developed calculus independently. His work in calculus was essential for solving complex mathematical problems, making it a cornerstone of modern mathematics and science.

His work ‘Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica’ was published in 1687, and remains a monumental work that underpins modern science. His profound insights continue to shape our understanding of the universe, making Isaac Newton one of history’s most influential and celebrated scientists.

Isaac Newton was an English scientist who was known for his groundbreaking discoveries in the fields of Physics, Mathematics and Astronomy. Thanks to his discoveries of revolutionizing our understanding of the natural world.

One of his well-known discoveries was the three laws of motion, also known as Newton’s three laws of motion.

- The first law, known as the law of inertia, states that objects at rest tend to stay at rest, and objects in motion tend to stay in motion unless acted upon by an external force.

- The second law quantifies how forces affect an object’s motion, introducing the famous equation F = ma (force equals mass times acceleration).

- The third law, the law of action and reaction, explains that for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

These laws provided a comprehensive framework for understanding and predicting the behaviour of physical objects, from the motion of planets to the fall of an apple.

Another groundbreaking achievement of Newton was the discovery of the universal law of gravitation. This law states that every object in the universe attracts every other object with a force directly proportional to their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

It explained the mechanics of planetary motion and demonstrated that the same laws that govern objects on Earth also apply to celestial bodies, unifying the terrestrial and celestial realms.

In mathematics, Newton independently developed a powerful mathematical tool, called calculus, for analyzing rates of change and solving complex problems. His work laid the groundwork for modern calculus and transformed mathematics, physics, and engineering.

Newton’s magnum opus, “Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica” (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), published in 1687, is a landmark work that brought together his laws of motion and the law of universal gravitation.

Related Articles:

- Essay on Rabindranath Tagore

- Essay on Allama Iqbal

- Essay on Technology

- Essay on Mahatma Gandhi

Issac Newton was an English mathematician, astronomer, theologian, alchemist, author and physicist, was known for the discovery of the laws of gravity, and worked on the principles of visible light and the laws of motion.

Newton’s three laws of motion are: first law of motion (law of inertia), which states that an object will stay at rest unless acted upon by an outside force; The second law of motion states that an object’s acceleration is produced by a net force that is directly proportional to the net force’s magnitude; The third law of motion states that every action has an equal and opposite reaction.

Issac Newton is known as the father of modern physics and was associated with Cambridge University as a physicist and mathematician.

For more information on such interesting topics, visit our essay writing page and make sure to follow Leverage Edu .

Shiva Tyagi

With an experience of over a year, I've developed a passion for writing blogs on wide range of topics. I am mostly inspired from topics related to social and environmental fields, where you come up with a positive outcome.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Connect With Us

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today.

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

January 2024

September 2024

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Have something on your mind?

Make your study abroad dream a reality in January 2022 with

India's Biggest Virtual University Fair

Essex Direct Admission Day

Why attend .

Don't Miss Out

Isaac Newton, Mathematician and Scientist Essay (Biography)

Introduction.

Isaac Newton is one of the greatest historical figures who will remain the annals of history, because of his numerous contributions to different scientific fields such as mathematics and physics. As Hall (Para 1) argues, “Generally, people have always regarded Newton as one of the most influential theorists in the history of science”. Most of his scientific experiments and abstracts laid the foundation of the modern day scientific inventions, as he was able to prove and document different theoretical concepts.

For example, his publication “Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy,” is one of the best scientific reference materials in physics and mathematics. Newton is well remembered for his numerous scientific discoveries such the laws of gravity, differential and integral calculus, the working of a telescope, and the three laws of linear motion. In addition to science, Newton was also very religious, because of the numerous biblical hermeneutics and occult studies that he wrote in his late life (1).

Newton‘s Early Life, Middle and Late Life

Newton’s early life.

Newton was born to Puritan parents Isaac Newton and Hannah Ayscough in 1643 in the county of Lincolnshire, England. He spent most of his childhood days with his grandmother, because his dad had passed away three months before he was born and he could not get along with his stepfather.

As During his early years of school, Newton schooled at the King’s School, Grantham, although it never lasted for long, because the passing away of his stepfather in 1659 forced his family to relocate to Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth; hence, making him to drop out of school. His stay in Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth was short-lived, because through the influence of King’s school master Henry Strokes, his mother allowed him to go back to school and finish his studies.

As a result of his exemplary performance in the King’s School, Newton got a chance of joining Trinity College, Cambridge on a sizar basis. In college, Newton was a very hardworking and fast learner, because in addition to reading the normal college curriculum materials that were based on Aristotle’s works, he was interested in reading more philosophical and astronomical works written by other philosophers such as Descartes and astronomers such as Galileo, and Thomas Hobes .

To a large extent, this laid the foundation for his later discoveries, because four years later in 1665, Newton invented the binomial theorem and came up with a mathematical theory, which he later modified to be called the infinitesimal calculus. The closure of Trinity College, Cambridge in the late 1665, because of the plague did not prevent Newton from advancing his studies on his own, as he continued with private studies at home.

Through his private studies Newton was able to discover numerous theories the primary ones being calculus, optics, the foundation of the theory of light and color, and the law of gravitation. Newton was very proud of his advancements, something that was evident in his words “ All this was in the two plague years of 1665 and 1666, for in those days I was in my prime of age for invention, and minded mathematics and philosophy more than at any time since,’ when college reopened (O’Connor and Robertson 1).

Newton’s middle Life

Upon the re-opening of his college in 1667, he was chosen as a minor fellow, and later as senior fellow when he embarked on his masters of Arts degree. In 1969, he was selected to replace Professor Isaac Barrow, who was the outgoing professor of Mathematics.

His appointment gave him more opportunities of improving his early works in optics, which led to the release of his first project paper on the nature of color in 1672, after being elected to the Royal Society. This marked the start of the numerous publications that Newton released later, although he faced numerous challenges and oppositions from one the leading science researchers, Robert Hook. Between 1670 and 1672 Newton also taught optics at Trinity College, Cambridge.

This enabled him to do further researches on the concept of refraction of light using glass prisms leading to his discovery on refraction of light and development of the first Newtonian telescope using mirrors. Although the 1678 emotional breakdown suffered by Newton was a major setback to his work, after recovering, he continued with his early researches which led to the publication of the Principia; a publication that elaborated on the laws of motion and the universal law of gravity.

In addition to this, the publication elaborated on some calculus laws primarily on geometrical analysis and some more explanations of the heliocentric theory of the solar system. This publication was followed by another publication that was the second edition of the Principia in 1713. This publication provided more explanations on the force of gravity and the force which made objects to be attracted to one another (Hatch 1).

Newton’s Late Life

His works in the Principia made Newton to a very respected and famous scientist of the time; hence, the nature of appointments, which he received in his late life. For example, in 1689 he was selected as the parliamentary representative of Cambridge; one of the highest power seats of the time. As if this was not enough, in 1703 Newton become the president of the Royal Society, a seat he maintained until his death and Later on in 1704, Newton released a publication named “Opticks” (Fowler 1).

The dawn of 1690’was a transitional period for Newton, as he ventured into the Bible World. As Hatch (1) argues “during this period Newton ventured into writing religious tracts with literal interpretation of the Bible.” Some of his writings included some works which questioned the reality behind the Trinity and the Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended.

Newton’s Scientific Achievements

Newton was one of the most successful historical scientists, because of his numerous contributions to different fields of science such as optics, mathematics, geography, and physics. In mathematics Newton’s discoveries included the binomial theorem of analytical geometry, new methods of solving infinite series in calculus, and the inverse methods of fluxions.

In optic, Newton was one of the first individuals to perform the first experiments on the decomposition of light and the working of the telescope, because of his early discovery on separation of the white light. This enabled Newton to formulate the Corpuscular Light Theory and discover other properties of the white light.

In addition to this, Newton also made numerous discoveries in Physics and mechanics such gravitational force, the centripetal force, the theory of fluids, and the revolution of planetary bodies. Further, Newton was made numerous discoveries in Alchemy and Chemistry, most of which are documented in his numerous publications on different areas of Alchemy, most of which were based on scientific experiments on matter (Hatch 1).

Although in his later life his level of wit his wit reduced, as Hatch (Para 13) argues, “Newton continued to exercise strong influence on the advancement of science, because of his position in the Royal Society. Newton died at the age of eighty fours in 1727, leaving behind a legacy will always remembered in the history of humankind, because of his scientific works.

Works Cited

Fowler, Michael. Isaac Newton: Newton’s life . 2010. Web.

Hall, Alfred. Isaac Newton’s life. Isaac Newton Institute of mathematical Sciences . 2011. Web.

Hatch, Robert. Sir Isaac Newton. 1998. Web.

O ’ Connor, John and Robertson, Ernest. Sir Isaac Newton . 2000. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 31). Isaac Newton, Mathematician and Scientist. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-biography-of-isaac-newton/

"Isaac Newton, Mathematician and Scientist." IvyPanda , 31 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/the-biography-of-isaac-newton/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Isaac Newton, Mathematician and Scientist'. 31 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Isaac Newton, Mathematician and Scientist." October 31, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-biography-of-isaac-newton/.

1. IvyPanda . "Isaac Newton, Mathematician and Scientist." October 31, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-biography-of-isaac-newton/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Isaac Newton, Mathematician and Scientist." October 31, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-biography-of-isaac-newton/.

- Isaac Newton and His Three Laws of Motion

- Classical Physics: Aristotle, Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton

- History of Calculus: Brief Review One of the Branches of Mathematics

- A Journal of the Plague Year by Daniel Defoe

- Scientific Traditions: Isaac Newton and Galileo

- Sir Isaac Newton Mathematical Theory

- Fundamental Theorem of Calculus in Modern World

- The Enlightenment Period in the Development of Culture

- Isaac Newton and His Life

- History of the Telescope

- Malcolm Baldrige Jr.: Hero of Quality Improvement

- Black Americans In The Westward Movement: The Key Figures

- Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Legacy

- The Life and Music of Frederic Chopin

- The Evolution of the American Hero

Essay on Isaac Newton

Students are often asked to write an essay on Isaac Newton in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton was born on January 4, 1643, in England. He was a curious child who loved reading and exploring nature.

Discoveries

Newton is famous for discovering gravity. The story goes that an apple falling from a tree inspired him. He also developed the three laws of motion.

Contributions to Mathematics

Newton invented a type of math called calculus. It helps us understand things that change and is used in many areas today.

Newton died in 1727. His discoveries still impact science and mathematics, making him one of the greatest thinkers in history.

Also check:

- Speech on Isaac Newton

250 Words Essay on Isaac Newton

Early life and education.

Isaac Newton, born on January 4, 1643, in Woolsthorpe, England, emerged as a pivotal figure in scientific revolution. His early education at King’s School, Grantham, laid the foundation for his future endeavors. Newton’s mother’s attempt to make him a farmer was thwarted by his evident intellectual curiosity, leading to his enrollment at Trinity College, Cambridge.

Developments in Mathematics and Physics

Newton’s most significant contributions lie in mathematics and physics. His work ‘Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica’ is a testament to his genius, introducing the three laws of motion, forming the basis of classical mechanics. Additionally, he developed calculus, a branch of mathematics instrumental in understanding changes in quantities.

Optics and the Theory of Colour

Newton’s work in optics revolutionized understanding of light and colour. His experiments with prisms led to the discovery that white light is a composite of all colors in the spectrum, debunking the then-prevailing belief of color being a mixture of light and darkness.

Legacy and Impact

Newton’s legacy extends beyond his lifetime, with his principles still being fundamental to modern scientific thought. His laws of motion and universal gravitation shaped our understanding of the physical world, while his work in optics and mathematics has far-reaching implications in various scientific fields.

In conclusion, Isaac Newton’s contributions to science and mathematics have been monumental, influencing centuries of scientific thought and discovery. His life and work continue to inspire curiosity and innovation in the quest for knowledge.

500 Words Essay on Isaac Newton

Introduction.

Isaac Newton, born on January 4, 1643, in Woolsthorpe, England, was a renowned physicist and mathematician. He is often hailed as one of the most influential scientists of all time. His contributions to the fields of physics, mathematics, and astronomy have had a profound impact on our understanding of the natural world.

Newton’s Early Life and Education

Newton was born prematurely and was not expected to survive. His father had died three months before his birth, leaving him with his mother, who later remarried. Newton was then raised by his grandmother. Despite these early hardships, Newton’s intellectual curiosity led him to the University of Cambridge, where he studied from 1661 to 1665.

The Birth of Newtonian Physics

During his time at Cambridge, Newton developed the foundations of calculus, though it wasn’t until later that he fully developed and published his work. The university closed in 1665 due to the Great Plague, and Newton returned home. It was during this period, known as his annus mirabilis, or “year of wonders”, that he made some of his most significant discoveries.

Among these was the law of universal gravitation, inspired reportedly by the fall of an apple from a tree. He proposed that every particle of matter attracts every other particle with a force that is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. This was a revolutionary concept that provided a unified explanation for terrestrial and celestial mechanics.

Newton’s Three Laws of Motion

In his work “Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica”, Newton outlined his three laws of motion. The first law, often called the law of inertia, states that an object at rest stays at rest and an object in motion stays in motion with the same speed and in the same direction unless acted upon by an unbalanced force. The second law established the relationship between force, mass, and acceleration. The third law, known as the action-reaction law, states that for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

Contributions to Optics

Newton’s contributions were not limited to physics and mathematics. He also made significant advancements in the field of optics. His experiments with prisms led to the discovery that white light is composed of a spectrum of colors, which he described in his work “Opticks”. He also built the first practical reflecting telescope, known as the Newtonian telescope.

Isaac Newton’s contributions to science have shaped our understanding of the physical world. His laws of motion and universal gravitation laid the groundwork for classical physics, and his work in optics expanded our understanding of light and color. Despite personal hardships and the tumultuous times in which he lived, Newton’s relentless curiosity and dedication to scientific exploration cemented his place in history as one of the greatest scientists of all time. His legacy continues to inspire scientists and researchers, reminding us of the boundless possibilities of human intellect.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Internet

- Essay on Integrity

- Essay on Inflation

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

The essay was so perfect but the date of birth is not same in 1st and 3rd essay.so may be the date of birth is wrong at in one essay.

Fixed, thanks.

Very nice and good essay

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

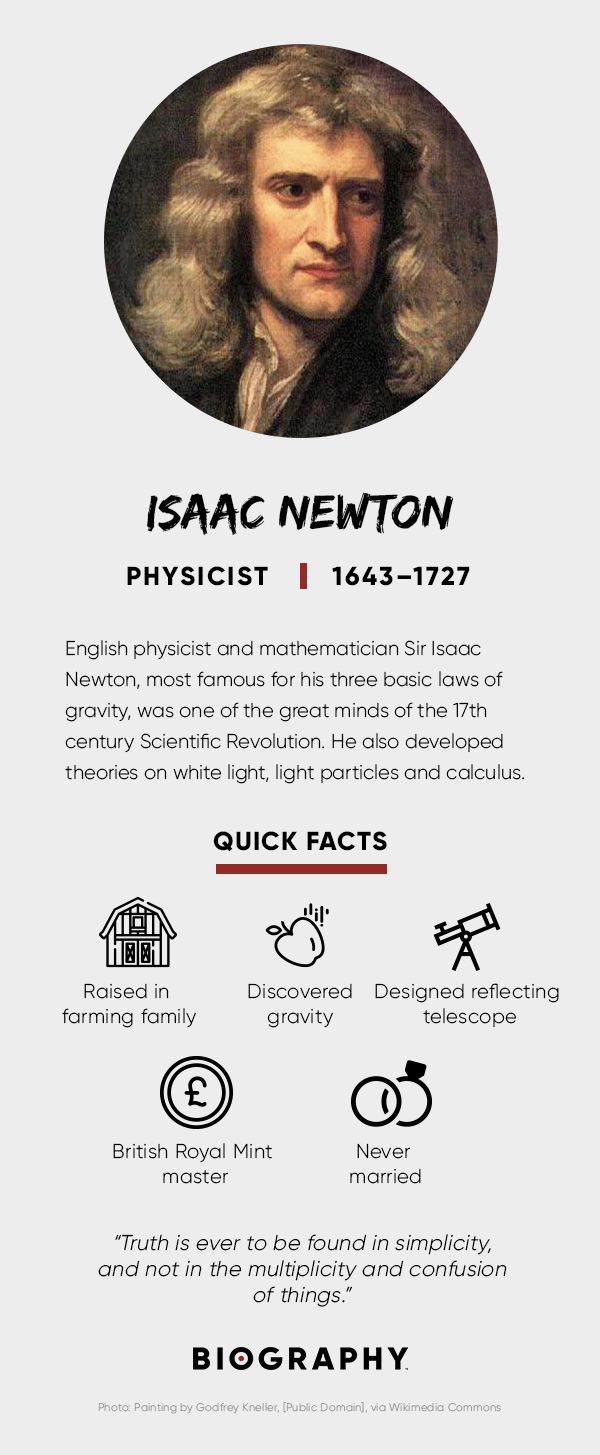

Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton was an English physicist and mathematician famous for his laws of physics. He was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century.

(1643-1727)

Who Was Isaac Newton?

In 1687, he published his most acclaimed work, Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy) , which has been called the single most influential book on physics. In 1705, he was knighted by Queen Anne of England, making him Sir Isaac Newton.

Early Life and Family

Newton was born on January 4, 1643, in Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire, England. Using the "old" Julian calendar, Newton's birth date is sometimes displayed as December 25, 1642.

Newton was the only son of a prosperous local farmer, also named Isaac, who died three months before he was born. A premature baby born tiny and weak, Newton was not expected to survive.

When he was 3 years old, his mother, Hannah Ayscough Newton, remarried a well-to-do minister, Barnabas Smith, and went to live with him, leaving young Newton with his maternal grandmother.

The experience left an indelible imprint on Newton, later manifesting itself as an acute sense of insecurity. He anxiously obsessed over his published work, defending its merits with irrational behavior.

At age 12, Newton was reunited with his mother after her second husband died. She brought along her three small children from her second marriage.

Isaac Newton's Education

Newton was enrolled at the King's School in Grantham, a town in Lincolnshire, where he lodged with a local apothecary and was introduced to the fascinating world of chemistry.

His mother pulled him out of school at age 12. Her plan was to make him a farmer and have him tend the farm. Newton failed miserably, as he found farming monotonous. Newton was soon sent back to King's School to finish his basic education.

Perhaps sensing the young man's innate intellectual abilities, his uncle, a graduate of the University of Cambridge's Trinity College , persuaded Newton's mother to have him enter the university. Newton enrolled in a program similar to a work-study in 1661, and subsequently waited on tables and took care of wealthier students' rooms.

Scientific Revolution

When Newton arrived at Cambridge, the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century was already in full force. The heliocentric view of the universe—theorized by astronomers Nicolaus Copernicus and Johannes Kepler, and later refined by Galileo —was well known in most European academic circles.

Philosopher René Descartes had begun to formulate a new concept of nature as an intricate, impersonal and inert machine. Yet, like most universities in Europe, Cambridge was steeped in Aristotelian philosophy and a view of nature resting on a geocentric view of the universe, dealing with nature in qualitative rather than quantitative terms.

During his first three years at Cambridge, Newton was taught the standard curriculum but was fascinated with the more advanced science. All his spare time was spent reading from the modern philosophers. The result was a less-than-stellar performance, but one that is understandable, given his dual course of study.

It was during this time that Newton kept a second set of notes, entitled "Quaestiones Quaedam Philosophicae" ("Certain Philosophical Questions"). The "Quaestiones" reveal that Newton had discovered the new concept of nature that provided the framework for the Scientific Revolution. Though Newton graduated without honors or distinctions, his efforts won him the title of scholar and four years of financial support for future education.

In 1665, the bubonic plague that was ravaging Europe had come to Cambridge, forcing the university to close. After a two-year hiatus, Newton returned to Cambridge in 1667 and was elected a minor fellow at Trinity College, as he was still not considered a standout scholar.

In the ensuing years, his fortune improved. Newton received his Master of Arts degree in 1669, before he was 27. During this time, he came across Nicholas Mercator's published book on methods for dealing with infinite series.

Newton quickly wrote a treatise, De Analysi , expounding his own wider-ranging results. He shared this with friend and mentor Isaac Barrow, but didn't include his name as author.

In June 1669, Barrow shared the unaccredited manuscript with British mathematician John Collins. In August 1669, Barrow identified its author to Collins as "Mr. Newton ... very young ... but of an extraordinary genius and proficiency in these things."

Newton's work was brought to the attention of the mathematics community for the first time. Shortly afterward, Barrow resigned his Lucasian professorship at Cambridge, and Newton assumed the chair.

Isaac Newton’s Discoveries

Newton made discoveries in optics, motion and mathematics. Newton theorized that white light was a composite of all colors of the spectrum, and that light was composed of particles.

His momentous book on physics, Principia , contains information on nearly all of the essential concepts of physics except energy, ultimately helping him to explain the laws of motion and the theory of gravity. Along with mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz, Newton is credited for developing essential theories of calculus.

Isaac Newton Inventions

Newton's first major public scientific achievement was designing and constructing a reflecting telescope in 1668. As a professor at Cambridge, Newton was required to deliver an annual course of lectures and chose optics as his initial topic. He used his telescope to study optics and help prove his theory of light and color.

The Royal Society asked for a demonstration of his reflecting telescope in 1671, and the organization's interest encouraged Newton to publish his notes on light, optics and color in 1672. These notes were later published as part of Newton's Opticks: Or, A treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and Colours of Light .

The Apple Myth

Between 1665 and 1667, Newton returned home from Trinity College to pursue his private study, as school was closed due to the Great Plague. Legend has it that, at this time, Newton experienced his famous inspiration of gravity with the falling apple. According to this common myth, Newton was sitting under an apple tree when a fruit fell and hit him on the head, inspiring him to suddenly come up with the theory of gravity.

While there is no evidence that the apple actually hit Newton on the head, he did see an apple fall from a tree, leading him to wonder why it fell straight down and not at an angle. Consequently, he began exploring the theories of motion and gravity.

It was during this 18-month hiatus as a student that Newton conceived many of his most important insights—including the method of infinitesimal calculus, the foundations for his theory of light and color, and the laws of planetary motion—that eventually led to the publication of his physics book Principia and his theory of gravity.

Isaac Newton’s Laws of Motion

In 1687, following 18 months of intense and effectively nonstop work, Newton published Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy) , most often known as Principia .

Principia is said to be the single most influential book on physics and possibly all of science. Its publication immediately raised Newton to international prominence.

Principia offers an exact quantitative description of bodies in motion, with three basic but important laws of motion:

A stationary body will stay stationary unless an external force is applied to it.

Force is equal to mass times acceleration, and a change in motion (i.e., change in speed) is proportional to the force applied.

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

Newton and the Theory of Gravity

Newton’s three basic laws of motion outlined in Principia helped him arrive at his theory of gravity. Newton’s law of universal gravitation states that two objects attract each other with a force of gravitational attraction that’s proportional to their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers.

These laws helped explain not only elliptical planetary orbits but nearly every other motion in the universe: how the planets are kept in orbit by the pull of the sun’s gravity; how the moon revolves around Earth and the moons of Jupiter revolve around it; and how comets revolve in elliptical orbits around the sun.

They also allowed him to calculate the mass of each planet, calculate the flattening of the Earth at the poles and the bulge at the equator, and how the gravitational pull of the sun and moon create the Earth’s tides. In Newton's account, gravity kept the universe balanced, made it work, and brought heaven and Earth together in one great equation.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S ISAAC NEWTON FACT CARD

Isaac Newton & Robert Hooke

Not everyone at the Royal Academy was enthusiastic about Newton’s discoveries in optics and 1672 publication of Opticks: Or, A treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and Colours of Light . Among the dissenters was Robert Hooke , one of the original members of the Royal Academy and a scientist who was accomplished in a number of areas, including mechanics and optics.

While Newton theorized that light was composed of particles, Hooke believed it was composed of waves. Hooke quickly condemned Newton's paper in condescending terms, and attacked Newton's methodology and conclusions.

Hooke was not the only one to question Newton's work in optics. Renowned Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens and a number of French Jesuits also raised objections. But because of Hooke's association with the Royal Society and his own work in optics, his criticism stung Newton the worst.

Unable to handle the critique, he went into a rage—a reaction to criticism that was to continue throughout his life. Newton denied Hooke's charge that his theories had any shortcomings and argued the importance of his discoveries to all of science.

In the ensuing months, the exchange between the two men grew more acrimonious, and soon Newton threatened to quit the Royal Society altogether. He remained only when several other members assured him that the Fellows held him in high esteem.

The rivalry between Newton and Hooke would continue for several years thereafter. Then, in 1678, Newton suffered a complete nervous breakdown and the correspondence abruptly ended. The death of his mother the following year caused him to become even more isolated, and for six years he withdrew from intellectual exchange except when others initiated correspondence, which he always kept short.

During his hiatus from public life, Newton returned to his study of gravitation and its effects on the orbits of planets. Ironically, the impetus that put Newton on the right direction in this study came from Robert Hooke.

In a 1679 letter of general correspondence to Royal Society members for contributions, Hooke wrote to Newton and brought up the question of planetary motion, suggesting that a formula involving the inverse squares might explain the attraction between planets and the shape of their orbits.

Subsequent exchanges transpired before Newton quickly broke off the correspondence once again. But Hooke's idea was soon incorporated into Newton's work on planetary motion, and from his notes it appears he had quickly drawn his own conclusions by 1680, though he kept his discoveries to himself.

In early 1684, in a conversation with fellow Royal Society members Christopher Wren and Edmond Halley, Hooke made his case on the proof for planetary motion. Both Wren and Halley thought he was on to something, but pointed out that a mathematical demonstration was needed.

In August 1684, Halley traveled to Cambridge to visit with Newton, who was coming out of his seclusion. Halley idly asked him what shape the orbit of a planet would take if its attraction to the sun followed the inverse square of the distance between them (Hooke's theory).

Newton knew the answer, due to his concentrated work for the past six years, and replied, "An ellipse." Newton claimed to have solved the problem some 18 years prior, during his hiatus from Cambridge and the plague, but he was unable to find his notes. Halley persuaded him to work out the problem mathematically and offered to pay all costs so that the ideas might be published, which it was, in Newton’s Principia .

Upon the publication of the first edition of Principia in 1687, Robert Hooke immediately accused Newton of plagiarism, claiming that he had discovered the theory of inverse squares and that Newton had stolen his work. The charge was unfounded, as most scientists knew, for Hooke had only theorized on the idea and had never brought it to any level of proof.

Newton, however, was furious and strongly defended his discoveries. He withdrew all references to Hooke in his notes and threatened to withdraw from publishing the subsequent edition of Principia altogether.

Halley, who had invested much of himself in Newton's work, tried to make peace between the two men. While Newton begrudgingly agreed to insert a joint acknowledgment of Hooke's work (shared with Wren and Halley) in his discussion of the law of inverse squares, it did nothing to placate Hooke.

As the years went on, Hooke's life began to unravel. His beloved niece and companion died the same year that Principia was published, in 1687. As Newton's reputation and fame grew, Hooke's declined, causing him to become even more bitter and loathsome toward his rival.

To the very end, Hooke took every opportunity he could to offend Newton. Knowing that his rival would soon be elected president of the Royal Society, Hooke refused to retire until the year of his death, in 1703.

Newton and Alchemy

Following the publication of Principia , Newton was ready for a new direction in life. He no longer found contentment in his position at Cambridge and was becoming more involved in other issues.

He helped lead the resistance to King James II's attempts to reinstitute Catholic teaching at Cambridge, and in 1689 he was elected to represent Cambridge in Parliament.

While in London, Newton acquainted himself with a broader group of intellectuals and became acquainted with political philosopher John Locke . Though many of the scientists on the continent continued to teach the mechanical world according to Aristotle , a young generation of British scientists became captivated with Newton's new view of the physical world and recognized him as their leader.

One of these admirers was Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, a Swiss mathematician whom Newton befriended while in London.

However, within a few years, Newton fell into another nervous breakdown in 1693. The cause is open to speculation: his disappointment over not being appointed to a higher position by England's new monarchs, William III and Mary II, or the subsequent loss of his friendship with Duillier; exhaustion from being overworked; or perhaps chronic mercury poisoning after decades of alchemical research.

It's difficult to know the exact cause, but evidence suggests that letters written by Newton to several of his London acquaintances and friends, including Duillier, seemed deranged and paranoiac, and accused them of betrayal and conspiracy.

Oddly enough, Newton recovered quickly, wrote letters of apology to friends, and was back to work within a few months. He emerged with all his intellectual facilities intact, but seemed to have lost interest in scientific problems and now favored pursuing prophecy and scripture and the study of alchemy.

While some might see this as work beneath the man who had revolutionized science, it might be more properly attributed to Newton responding to the issues of the time in turbulent 17th century Britain.

Many intellectuals were grappling with the meaning of many different subjects, not least of which were religion, politics and the very purpose of life. Modern science was still so new that no one knew for sure how it measured up against older philosophies.

Gold Standard

In 1696, Newton was able to attain the governmental position he had long sought: warden of the Mint; after acquiring this new title, he permanently moved to London and lived with his niece, Catherine Barton.

Barton was the mistress of Lord Halifax, a high-ranking government official who was instrumental in having Newton promoted, in 1699, to master of the Mint—a position that he would hold until his death.

Not wanting it to be considered a mere honorary position, Newton approached the job in earnest, reforming the currency and severely punishing counterfeiters. As master of the Mint, Newton moved the British currency, the pound sterling, from the silver to the gold standard.

The Royal Society

In 1703, Newton was elected president of the Royal Society upon Robert Hooke's death. However, Newton never seemed to understand the notion of science as a cooperative venture, and his ambition and fierce defense of his own discoveries continued to lead him from one conflict to another with other scientists.

By most accounts, Newton's tenure at the society was tyrannical and autocratic; he was able to control the lives and careers of younger scientists with absolute power.

In 1705, in a controversy that had been brewing for several years, German mathematician Gottfried Leibniz publicly accused Newton of plagiarizing his research, claiming he had discovered infinitesimal calculus several years before the publication of Principia .

In 1712, the Royal Society appointed a committee to investigate the matter. Of course, since Newton was president of the society, he was able to appoint the committee's members and oversee its investigation. Not surprisingly, the committee concluded Newton's priority over the discovery.

That same year, in another of Newton's more flagrant episodes of tyranny, he published without permission the notes of astronomer John Flamsteed. It seems the astronomer had collected a massive body of data from his years at the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, England.

Newton had requested a large volume of Flamsteed's notes for his revisions to Principia . Annoyed when Flamsteed wouldn't provide him with more information as quickly as he wanted it, Newton used his influence as president of the Royal Society to be named the chairman of the body of "visitors" responsible for the Royal Observatory.

He then tried to force the immediate publication of Flamsteed's catalogue of the stars, as well as all of Flamsteed's notes, edited and unedited. To add insult to injury, Newton arranged for Flamsteed's mortal enemy, Edmund Halley, to prepare the notes for press.

Flamsteed was finally able to get a court order forcing Newton to cease his plans for publication and return the notes—one of the few times that Newton was bested by one of his rivals.

Final Years

Toward the end of this life, Newton lived at Cranbury Park, near Winchester, England, with his niece, Catherine (Barton) Conduitt, and her husband, John Conduitt.

By this time, Newton had become one of the most famous men in Europe. His scientific discoveries were unchallenged. He also had become wealthy, investing his sizable income wisely and bestowing sizable gifts to charity.

Despite his fame, Newton's life was far from perfect: He never married or made many friends, and in his later years, a combination of pride, insecurity and side trips on peculiar scientific inquiries led even some of his few friends to worry about his mental stability.

By the time he reached 80 years of age, Newton was experiencing digestion problems and had to drastically change his diet and mobility.

In March 1727, Newton experienced severe pain in his abdomen and blacked out, never to regain consciousness. He died the next day, on March 31, 1727, at the age of 84.

Newton's fame grew even more after his death, as many of his contemporaries proclaimed him the greatest genius who ever lived. Maybe a slight exaggeration, but his discoveries had a large impact on Western thought, leading to comparisons to the likes of Plato , Aristotle and Galileo.

Although his discoveries were among many made during the Scientific Revolution, Newton's universal principles of gravity found no parallels in science at the time.

Of course, Newton was proven wrong on some of his key assumptions. In the 20th century, Albert Einstein would overturn Newton's concept of the universe, stating that space, distance and motion were not absolute but relative and that the universe was more fantastic than Newton had ever conceived.

Newton might not have been surprised: In his later life, when asked for an assessment of his achievements, he replied, "I do not know what I may appear to the world; but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself now and then in finding a smoother pebble or prettier shell than ordinary, while the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me."

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Isaac Newton

- Birth Year: 1643

- Birth date: January 4, 1643

- Birth City: Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire, England

- Birth Country: United Kingdom

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Isaac Newton was an English physicist and mathematician famous for his laws of physics. He was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century.

- Science and Medicine

- Technology and Engineering

- Education and Academia

- Astrological Sign: Capricorn

- University of Cambridge, Trinity College

- The King's School

- Interesting Facts

- Isaac Newton helped develop the principles of modern physics, including the laws of motion, and is credited as one of the great minds of the 17th-century Scientific Revolution.

- In 1687, Newton published his most acclaimed work, 'Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica' ('Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy'), which has been called the single most influential book on physics.

- Newton's theory of gravity states that two objects attract each other with a force of gravitational attraction that’s proportional to their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers.

- Death Year: 1727

- Death date: March 31, 1727

- Death City: London, England

- Death Country: United Kingdom

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Isaac Newton Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/scientists/isaac-newton

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: November 5, 2020

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- I do not know what I may appear to the world; but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself now and then in finding a smoother pebble or prettier shell than ordinary, while the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.

- Plato is my friend, Aristotle is my friend, but my greatest friend is truth.

- If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.

- It is the perfection of God's works that they are all done with the greatest simplicity.

- Every body continues in its state of rest, or of uniform motion in a right line, unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impressed upon it.

- To every action there is always opposed an equal reaction: or, the mutual actions of two bodies upon each other are always equal, and directed to contrary parts.

- I see I have made myself a slave to philosophy.

- The changing of bodies into light, and light into bodies, is very conformable to the course of nature, which seems delighted with transmutations.

- To explain all nature is too difficult a task for any one man or even for any one age. Tis much better to do a little with certainty and leave the rest for others that come after, then to explain all things by conjecture without making sure of any thing.

- Truth is ever to be found in simplicity, and not in the multiplicity and confusion of things.

- Atheism is so senseless and odious to mankind that it never had many professors.

- Newton was not the first of the age of reason. He was the last of the magicians, the last of the Babylonians and Sumerians, the last great mind that looked out on the visible and intellectual world with the same eyes as those who began to build our intellectual inheritance rather less than 10,000 years ago.

Famous British People

Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales

Kensington Palace Shares an Update on Kate

Amy Winehouse

Prince William

Where in the World Is Kate Middleton?

Christopher Nolan

Emily Blunt

Jane Goodall

Princess Kate Is Seen for First Time Since Surgery

King Charles III

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Isaac Newton

By: History.com Editors

Updated: October 16, 2023 | Original: March 10, 2015

![isaac newton essay writing Sir Isaac NewtonENGLAND - JANUARY 01: Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) .Canvas. (Photo by Imagno/Getty Images) [Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) . Gemaelde.]](https://assets.editorial.aetnd.com/uploads/2015/03/isaac-newton-gettyimages-56458980.jpg?width=3840&height=1920&crop=3840%3A1920%2Csmart&quality=75&auto=webp)

Isaac Newton is best know for his theory about the law of gravity, but his “Principia Mathematica” (1686) with its three laws of motion greatly influenced the Enlightenment in Europe. Born in 1643 in Woolsthorpe, England, Sir Isaac Newton began developing his theories on light, calculus and celestial mechanics while on break from Cambridge University.

Years of research culminated with the 1687 publication of “Principia,” a landmark work that established the universal laws of motion and gravity. Newton’s second major book, “Opticks,” detailed his experiments to determine the properties of light. Also a student of Biblical history and alchemy, the famed scientist served as president of the Royal Society of London and master of England’s Royal Mint until his death in 1727.

Isaac Newton: Early Life and Education

Isaac Newton was born on January 4, 1643, in Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire, England. The son of a farmer who died three months before he was born, Newton spent most of his early years with his maternal grandmother after his mother remarried. His education was interrupted by a failed attempt to turn him into a farmer, and he attended the King’s School in Grantham before enrolling at the University of Cambridge’s Trinity College in 1661.

Newton studied a classical curriculum at Cambridge, but he became fascinated by the works of modern philosophers such as René Descartes, even devoting a set of notes to his outside readings he titled “Quaestiones Quaedam Philosophicae” (“Certain Philosophical Questions”). When the Great Plague shuttered Cambridge in 1665, Newton returned home and began formulating his theories on calculus, light and color, his farm the setting for the supposed falling apple that inspired his work on gravity.

Isaac Newton’s Telescope and Studies on Light

Newton returned to Cambridge in 1667 and was elected a minor fellow. He constructed the first reflecting telescope in 1668, and the following year he received his Master of Arts degree and took over as Cambridge’s Lucasian Professor of Mathematics. Asked to give a demonstration of his telescope to the Royal Society of London in 1671, he was elected to the Royal Society the following year and published his notes on optics for his peers.

Through his experiments with refraction, Newton determined that white light was a composite of all the colors on the spectrum, and he asserted that light was composed of particles instead of waves. His methods drew sharp rebuke from established Society member Robert Hooke, who was unsparing again with Newton’s follow-up paper in 1675.

Known for his temperamental defense of his work, Newton engaged in heated correspondence with Hooke before suffering a nervous breakdown and withdrawing from the public eye in 1678. In the following years, he returned to his earlier studies on the forces governing gravity and dabbled in alchemy.

Isaac Newton and the Law of Gravity

In 1684, English astronomer Edmund Halley paid a visit to the secluded Newton. Upon learning that Newton had mathematically worked out the elliptical paths of celestial bodies, Halley urged him to organize his notes.

The result was the 1687 publication of “Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica” (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), which established the three laws of motion and the law of universal gravity. Newton’s three laws of motion state that (1) Every object in a state of uniform motion will remain in that state of motion unless an external force acts on it; (2) Force equals mass times acceleration: F=MA and (3) For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.

“Principia” propelled Newton to stardom in intellectual circles, eventually earning universal acclaim as one of the most important works of modern science. His work was a foundational part of the European Enlightenment .

With his newfound influence, Newton opposed the attempts of King James II to reinstitute Catholic teachings at English Universities. King James II was replaced by his protestant daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange as part of the Glorious Revolution of 1688, and Newton was elected to represent Cambridge in Parliament in 1689.

Newton moved to London permanently after being named warden of the Royal Mint in 1696, earning a promotion to master of the Mint three years later. Determined to prove his position wasn’t merely symbolic, Newton moved the pound sterling from the silver to the gold standard and sought to punish counterfeiters.

The death of Hooke in 1703 allowed Newton to take over as president of the Royal Society, and the following year he published his second major work, “Opticks.” Composed largely from his earlier notes on the subject, the book detailed Newton’s painstaking experiments with refraction and the color spectrum, closing with his ruminations on such matters as energy and electricity. In 1705, he was knighted by Queen Anne of England.

Isaac Newton: Founder of Calculus?

Around this time, the debate over Newton’s claims to originating the field of calculus exploded into a nasty dispute. Newton had developed his concept of “fluxions” (differentials) in the mid 1660s to account for celestial orbits, though there was no public record of his work.

In the meantime, German mathematician Gottfried Leibniz formulated his own mathematical theories and published them in 1684. As president of the Royal Society, Newton oversaw an investigation that ruled his work to be the founding basis of the field, but the debate continued even after Leibniz’s death in 1716. Researchers later concluded that both men likely arrived at their conclusions independent of one another.

Death of Isaac Newton

Newton was also an ardent student of history and religious doctrines, and his writings on those subjects were compiled into multiple books that were published posthumously. Having never married, Newton spent his later years living with his niece at Cranbury Park near Winchester, England. He died in his sleep on March 31, 1727, and was buried in Westminster Abbey .

A giant even among the brilliant minds that drove the Scientific Revolution, Newton is remembered as a transformative scholar, inventor and writer. He eradicated any doubts about the heliocentric model of the universe by establishing celestial mechanics, his precise methodology giving birth to what is known as the scientific method. Although his theories of space-time and gravity eventually gave way to those of Albert Einstein , his work remains the bedrock on which modern physics was built.

Isaac Newton Quotes

- “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.”

- “I can calculate the motion of heavenly bodies but not the madness of people.”

- “What we know is a drop, what we don't know is an ocean.”

- “Gravity explains the motions of the planets, but it cannot explain who sets the planets in motion.”

- “No great discovery was ever made without a bold guess.”

HISTORY Vault: Sir Isaac Newton: Gravity of Genius

Explore the life of Sir Isaac Newton, who laid the foundations for calculus and defined the laws of gravity.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essay Examples >

- Essays Topics >

- Essay on Education

Essay On Isaac Newton

Type of paper: Essay

Topic: Education , Science , Students , Literature , Innovation , Violence , World , Isaac Newton

Published: 11/15/2019

ORDER PAPER LIKE THIS

Isaac Newton was an English scientist who not only studied but made stupendous discoveries in mathematics, physics, and chemistry. However, he is also a well-known astronomer, natural philosopher and theologian. Sir Isaac Newton was born in three months after the death of his father and when his mother remarried he moved to his grandparents. These were the people that raised him from his youth. On reaching the proper age, Newton attended Cambridge University where he stayed until the plague hit. Even though he called his age of the time of the plague "the prime of my age for invention", no natural disaster was able to stop him from his scientific studies.

It was after the university that he began his discoveries connected with optics. His invention of the reflecting telescope in 1668 finally drew the attention of other scientists. Isaac Newton conducted a number of experiments concerning light and its composition. That’s to this hard work he was able to put forward a number of discoveries. He proved that light can be measured by patterns. Moreover, he proved that white light consists of different colored rays which correspond to the colors of the rainbow. Each ray can be defined by the angle through which it is reflected. All this and much more was published in his book “Optics” in 1704.

Isaac Newton is mostly known for what is now something of a legend, a story told to kids. His discovery of the laws of gravity is what he is best known for among people who do not tie their lives with science. The story goes like this. Isaac was allegedly sitting under a tree. All of a sudden an apple fell on his head. A bit stumped at first, our great scientist started to think and analyze. By measuring the force needed to hold the moon in orbit he inevitably understood that there must be some other force, one which has not been studied before. And so there is – the force of gravity.

Isaac Newton was not only a scientist but also a powerful public figure. He was elected member of the parliament for the University of Cambridge to oppose the Kind James II’s attempts to make universities catholic. It should be noted that he also held the post of a Mint and was even knighted. This was a prominent figure in the scientific world and in the public world of his time. His work will not be forgotten.

Cite this page

Share with friends using:

Removal Request

Finished papers: 1123

This paper is created by writer with

ID 279288625

If you want your paper to be:

Well-researched, fact-checked, and accurate

Original, fresh, based on current data

Eloquently written and immaculately formatted

275 words = 1 page double-spaced

Get your papers done by pros!

Other Pages

Bachelors degree personal statements, syndicate case studies, accounts receivable case studies, spider case studies, organising case studies, fob case studies, bun case studies, oblique case studies, emancipation case studies, stretching case studies, memory loss case studies, free research paper on is opec a cartel, dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating disorder article review sample, critical thinking on disaster recovery policies and procedures, was roosevelts approach to the great depression successful essays examples, example of wine variety and my wine grape is barbera research paper, free sex appeal essay example, leading and trust research paper sample, sample research paper on copd, ginkgo biloba and memory literature review sample, good role of social insects essay example, good example of essay on social determinants of health, free nikola teslas influence on the world essay sample, should tobacco companies be held responsible for smoking related illnesses and deaths research proposal samples, free sea world essay example, free ethics and professional practice essay example, good standards of care research paper example, good essay on coach knight, complete an assignment essay example, good critical thinking on water sanitation and hygiene, recitatif essays, blewett essays, bosco essays, epicardial essays, biguanides essays, betadine essays, cauter essays, cruciform essays, bilious essays, centrophenoxine essays, cristal essays, bimolecular essays.

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

- Scientific Methods

- Famous Physicists

- Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton

Apart from discovering the cause of the fall of an apple from a tree, that is, the laws of gravity, Sir Isaac Newton was perhaps one of the most brilliant and greatest physicists of all time. He shaped dramatic and surprising discoveries in the laws of physics that we believe our universe obeys, and hence it changed the way we appreciate and relate to the world around us.

Table of Contents

About sir isaac newton, sir isaac newton’s education, awards and achievements, some achievements of isaac newton in brief.

- Universal Law of Gravitation

Optics and Light

Sir Isaac Newton was born on 4th January 1643 in a small village of England called Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth. He was an English physicist and mathematician, and one of the important thinkers in the Scientific Revolution.

He discovered the phenomenon of white light integrated with colours which further laid the foundation of modern physical optics. His famous three laws of Motion in mechanics and the formulation of the laws of gravitation completely changed the track of physics across the globe. He was the originator of calculus in mathematics. A scientist like him is considered an excellent gift by nature to the world of physics.

Isaac Newton studied at the Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1661. At 22 in 1665, a year after beginning his four-year scholarship, Newton finished his first significant discovery in mathematics, where he revealed the generalized binomial theorem. He was bestowed with his B.A. degree in the same year.

Isaac Newton held numerous positions throughout his life. In 1671, he was invited to join the Royal Society of London after developing a new and enhanced version of the reflecting telescope.

He was later elected President of the Royal Society (1703). Sir Isaac Newton ran for a seat in Parliament in 1689. He won the election and became a Member of Parliament for Cambridge University. He was also appointed as a Warden of the Mint in 1969. Due to his exemplary work and dedication to the mint, he was chosen Master of the Mint in 1700. After being knighted in 1705, he was known as “Sir Isaac Newton.”

His mind was ablaze with original ideas. He made significant progress in three distinct fields – with some of the most profound discoveries in:

- Calculus, the mathematics of change, which is vital to our understanding of the world around us

- Optics and the behaviour of light

- He also built the first working reflecting telescope

- He showed that Kepler’s laws of planetary motion are exceptional cases of Newton’s universal gravitation.

Sir Isaac Newton’s Contribution in Calculus

Sir Isaac Newton was the first individual to develop calculus. Modern physics and physical chemistry are almost impossible without calculus, as it is the mathematics of change.

The idea of differentiating calculus into differential calculus, integral calculus and differential equations came from Newton’s fertile mind. Today, most mathematicians give equal credit to Newton and Leibniz for calculus’s discovery.

Law of Universal Gravitation

The famous apple that he saw falling from a tree led him to discover the force of gravitation and its laws. Ultimately, he realised that the pressure causing the apple’s fall is responsible for the moon to orbit the earth, as well as comets and other planets to revolve around the sun. The force can be felt throughout the universe. Hence, Newton called it the Universal Law of Gravitation .

Newton discovered the equation that allows us to compute the force of gravity between two objects.

Newton’s Laws of Motion

- First law of Motion

- Second Law of Motion

- Third law of Motion

Watch the video and learn about the history of the concept of Gravitation

Sir Isaac Newton also accomplished himself in experimental methods and working with equipment. He built the world’s first reflecting telescope . This telescope focuses all the light from a curved mirror. Here are some advantages of reflecting telescopes from optics and light –

- They are inexpensive to make.

- They are easier to make in large sizes, gathering lighter, allowing advanced magnification.

- They don’t suffer focusing issues linked with lenses called chromatic aberration.

Isaac Newton also proved that white light is not a simple phenomenon with the help of a glass prism. He confirmed that it is made up of all of the colours of the rainbow, which could recombine to form white light again.

Watch the video and solve complete NCERT exercise questions in the chapter Gravitation

Frequently Asked Questions

How did newton discover gravity.

Seeing an apple fall from the tree made him think about the forces of nature.

What is Calculus in Mathematics?

Calculus is the study of differentiation and integration. Calculus explains the changes in values, on a small and large scale, related to any function.

Define Reflecting Telescope.

It’s a telescope invented by Newton that uses mirrors to collect and focus the light towards the eyepiece.

Name all the Kepler’s Laws of planetary motion.

Kepler’s three laws of planetary motion are:

- The Law of Ellipses

- The Law of Equal Areas

- The Law of Harmonies

Who discovered Gravity?

Watch the full summary of the chapter gravitation class 9.

Stay tuned to BYJU’S and Fall in Love with Learning!

Put your understanding of this concept to test by answering a few MCQs. Click Start Quiz to begin!

Select the correct answer and click on the "Finish" button Check your score and explanations at the end of the quiz

Visit BYJU'S for all Physics related queries and study materials

Your result is as below

Request OTP on Voice Call

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post My Comment

How isaac Newton interest developed in science?

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

- View all collections

Cambridge Digital Library

Newton papers.

Plato is my friend, Aristotle is my friend, but my greatest friend is truth." Sir Isaac Newton ( MS Add.3996, 88r ) Trinity College, Cambridge.

Cambridge University Library holds the largest and most important collection of the scientific works of Isaac Newton (1642-1727). They range from his early papers and College notebooks through to the ground-breaking Waste Book and his own annotated copy of the first edition of the Principia . These manuscripts along with those held at Trinity College Cambridge, King’s College Cambridge, the Fitzwilliam Museum, the Royal Society and the National Library of Israel have been added to the Unesco Memory of the World Register . As well as University Library material, our collection includes two important items from The Royal Society's collections - a manuscript copy of the Principia and a collection of Newton's correspondence .

Newton was closely associated with Cambridge. He came to the University as a student in 1661, graduating in 1665, and from 1669 to 1701 he held the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics. Under the regulations for this Chair, Newton was required to deposit copies of his lectures in the University Library. These, and some correspondence relating to the University, were assigned the classmarks Dd.4.18, Dd.9.46, Dd.9.67, Dd.9.68, and Mm.6.50.

In 1699 Newton was appointed Master of the Mint, and in 1703 he was elected President of the Royal Society, a post he occupied until his death.

After his death, the manuscripts in Newton's possession passed to his niece Catherine and her husband John Conduitt. In 1740 the Conduitts' daughter, also Catherine, married John Wallop, who became Viscount Lymington when his father was created first Earl of Portsmouth. Their son became the second earl and the manuscripts were passed down succeeding generations of the family.

In 1872 the fifth earl passed all the Newton manuscripts he had to the University of Cambridge, where they were assessed and a detailed catalogue made. Based on this catalogue, the earl generously presented all the mathematical and scientific manuscripts to the University, and it is these that form the Library's 'Portsmouth collection' (MSS Add. 3958-Add. 4007).

The remainder of the Newton papers, many concerned with alchemy, theology and chronology, were returned to Lord Portsmouth. They were sold at auction at Sotheby's in London in 1936 and purchased by other libraries and individuals.

In 2000 Cambridge University Library acquired a very important collection of scientific manuscripts from the Earl of Macclesfield, which included a significant number of Isaac Newton's letters and other papers.

A number of videos explaining aspects of Newton's work and manuscripts are available from the Newton Project's YouTube site , a selection of which are presented alongside our manuscripts.

- Overview of Newton Papers held at Cambridge University Library (from Manuscripts Department website)

- History of Isaac Newton's Papers (from Newton Project website)

- Catalogue of the Portsmouth Collection

- Catalogue of the Macclesfield Collection

- Sir Isaac Newton’s Cambridge papers added to the UNESCO Memory of the World Register .

University of Cambridge

© University of Cambridge

- Contact the University

- Accessibility

- Freedom of information

- Privacy policy and cookies

- Statement on Modern Slavery

- Terms and conditions

- University A-Z

Study at Cambridge

- Undergraduate

- Postgraduate

- Continuing education

- Executive and professional education

- Courses in education

About the University

- How the University and Colleges work

- Give to Cambridge

- Visiting the University

Research at Cambridge

- Research news

- About research at Cambridge

- Public engagement

- Spotlight on...

Introduction to the Texts

- Mathematical

- His Notebooks

- by category

- His Life & Work at a Glance

- His Personal Life

- 18th Century

- 19th Century

- The Portsmouth Papers

- The Sotheby Sale

- Newton-related Papers of John Maynard Keynes

- Other Attempts to Publish Newton's Papers

- About Newton's Library

- Books in Newton's Library

- Bibliography

- The Newton Project

- Staff and Editorial Board

- Tagging & Transcription Guidelines

- Acknowledgments

A. The Religious Papers

B. the mathematical and scientific papers, c. the mathematical and scientific correspondence, d. political materials, e. historical contextual materials.

Newton’s more polished religious writings are among the most original treatises on theology in the early modern period, and their publication allows researchers to see this work in its totality for the first time. Given their scope and quality, as well as their status as previously unseen works by Isaac Newton, their release constitutes a major event in the history of early modern thought. The approximately 2.2m words of Newton’s religious writings published since the start of 2008 show each stage of his creative process, from his note-taking to his idiosyncratic redrafting of various texts, and then finally on to the polished and virtually complete texts, written for a still largely mysterious audience. These texts transform what we know of the scale and nature of Newton’s researches, and make it possible for the first time to understand the links between different strands of his religious writings; the order of their composition; their putative links with other areas of his intellectual life; and their relations to the wider social and intellectual contexts in which he worked. They are available in both diplomatic and normalised form, and from November 2013 have been linked to images of the originals held by the NLI. At the time of writing, fourteen of Newton’s original Latin productions have been translated (all but one by Michael Silverthorne). [1]

It is impossible to say exactly to what extent the religious archive as it stands was organised by Newton himself, and to what degree it has resulted from later organising efforts by his relatives, editors and owners. Fortunately, and despite the fact that the archive is now distributed across the globe, we have very good evidence that virtually nothing has been lost from the collection of papers that existed at Newton’s death. Having said that, we also know that many efforts have been made to re-order the papers by bringing together drafts or disparate documents that concern the same topic, or by joining together parts of one document that have been separated for hundreds of years.

Some of the collections that have come down to us contain a large number of much smaller documents that seem to have been put into a pile on the grounds that they belonged nowhere else. One good example is the extensive set of papers at New College Oxford (designated New College Oxford 361.2). This contains calculations associated with the second edition of the Principia , papers connected with Newton’s business at the Mint, and numerous drafts of his work on prophecy and chronology. Many of these topics can be found together on one single sheet, and often on letters addressed to Newton. Many of these pages are charred through burning, and numerous pages are genuine palimpsests whose interpretation, transcription and encoding is a monumental act of scholarly labour. For that very reason, the checking and proofing of this most resistant of documents will not occur until the spring of 2014.

The Newton Project has greatly expanded our knowledge of three aspects of Newton’s religious interests:

(i) the publication of his theological writings reveals the full range of his private religious opinions, and answers questions about his beliefs that have beguiled the curious for over three centuries. Newton’s religious nachlass has proved to be much larger and much more complex than we envisaged when we began the work fifteen years ago, and the texts available via the Newton Project are now among the largest set of religious resources for any individual. The papers demonstrate that in this field Newton was a thinker of the highest calibre and intellectual daring, though our respect for his courage may well be tempered by the fact that he published almost nothing of it in his lifetime. These would be fascinating texts if we did not know who their author was, or if we knew that they were not by Newton. As it is, the fact that they are certainly written by Newton, and that many of his most exciting non-scientific works were composed when he was at the peak of his intellectual powers (in the 1670s and 80s), allows researchers for the first time to assess the degree to which these texts are similar to his contemporary work in natural science.