How to Write the AP Lit Prose Essay with Examples

March 30, 2024

AP Lit Prose Essay Examples – The College Board’s Advanced Placement Literature and Composition Course is one of the most enriching experiences that high school students can have. It exposes you to literature that most people don’t encounter until college , and it helps you develop analytical and critical thinking skills that will enhance the quality of your life, both inside and outside of school. The AP Lit Exam reflects the rigor of the course. The exam uses consistent question types, weighting, and scoring parameters each year . This means that, as you prepare for the exam, you can look at previous questions, responses, score criteria, and scorer commentary to help you practice until your essays are perfect.

What is the AP Lit Free Response testing?

In AP Literature, you read books, short stories, and poetry, and you learn how to commit the complex act of literary analysis . But what does that mean? Well, “to analyze” literally means breaking a larger idea into smaller and smaller pieces until the pieces are small enough that they can help us to understand the larger idea. When we’re performing literary analysis, we’re breaking down a piece of literature into smaller and smaller pieces until we can use those pieces to better understand the piece of literature itself.

So, for example, let’s say you’re presented with a passage from a short story to analyze. The AP Lit Exam will ask you to write an essay with an essay with a clear, defensible thesis statement that makes an argument about the story, based on some literary elements in the short story. After reading the passage, you might talk about how foreshadowing, allusion, and dialogue work together to demonstrate something essential in the text. Then, you’ll use examples of each of those three literary elements (that you pull directly from the passage) to build your argument. You’ll finish the essay with a conclusion that uses clear reasoning to tell your reader why your argument makes sense.

AP Lit Prose Essay Examples (Continued)

But what’s the point of all of this? Why do they ask you to write these essays?

Well, the essay is, once again, testing your ability to conduct literary analysis. However, the thing that you’re also doing behind that literary analysis is a complex process of both inductive and deductive reasoning. Inductive reasoning takes a series of points of evidence and draws a larger conclusion. Deductive reasoning departs from the point of a broader premise and draws a singular conclusion. In an analytical essay like this one, you’re using small pieces of evidence to draw a larger conclusion (your thesis statement) and then you’re taking your thesis statement as a larger premise from which you derive your ultimate conclusion.

So, the exam scorers are looking at your ability to craft a strong thesis statement (a singular sentence that makes an argument), use evidence and reasoning to support that argument, and then to write the essay well. This is something they call “sophistication,” but they’re looking for well-organized thoughts carried through clear, complete sentences.

This entire process is something you can and will use throughout your life. Law, engineering, medicine—whatever pursuit, you name it—utilizes these forms of reasoning to run experiments, build cases, and persuade audiences. The process of this kind of clear, analytical thinking can be honed, developed, and made easier through repetition.

Practice Makes Perfect

Because the AP Literature Exam maintains continuity across the years, you can pull old exam copies, read the passages, and write responses. A good AP Lit teacher is going to have you do this time and time again in class until you have the formula down. But, it’s also something you can do on your own, if you’re interested in further developing your skills.

AP Lit Prose Essay Examples

Let’s take a look at some examples of questions, answers and scorer responses that will help you to get a better idea of how to craft your own AP Literature exam essays.

In the exam in 2023, students were asked to read a poem by Alice Cary titled “Autumn,” which was published in 1874. In it, the speaker contemplates the start of autumn. Then, students are asked to craft a well-written essay which uses literary techniques to convey the speaker’s complex response to the changing seasons.

The following is an essay that received a perfect 6 on the exam. There are grammar and usage errors throughout the essay, which is important to note: even though the writer makes some mistakes, the structure and form of their argument was strong enough to merit a 6. This is what your scorers will be looking for when they read your essay.

Example Essay

Romantic and hyperbolic imagery is used to illustrate the speaker’s unenthusiastic opinion of the coming of autumn, which conveys Cary’s idea that change is difficult to accept but necessary for growth.

Romantic imagery is utilized to demonstrate the speaker’s warm regard for the season of summer and emphasize her regretfulness for autumn’s coming, conveying the uncomfortable change away from idyllic familiarity. Summer, is portrayed in the image of a woman who “from her golden collar slips/and strays through stubble fields/and moans aloud.” Associated with sensuality and wealth, the speaker implies the interconnection between a season and bounty, comfort, and pleasure. Yet, this romantic view is dismantled by autumn, causing Summer to “slip” and “stray through stubble fields.” Thus, the coming of real change dethrones a constructed, romantic personification of summer, conveying the speaker’s reluctance for her ideal season to be dethroned by something much less decorated and adored.

Summer, “she lies on pillows of the yellow leaves,/ And tries the old tunes for over an hour”, is contrasted with bright imagery of fallen leaves/ The juxtaposition between Summer’s character and the setting provides insight into the positivity of change—the yellow leaves—by its contrast with the failures of attempting to sustain old habits or practices, “old tunes”. “She lies on pillows” creates a sympathetic, passive image of summer in reaction to the coming of Autumn, contrasting her failures to sustain “old tunes.” According to this, it is understood that the speaker recognizes the foolishness of attempting to prevent what is to come, but her wishfulness to counter the natural progression of time.

Hyperbolic imagery displays the discrepancies between unrealistic, exaggerated perceptions of change and the reality of progress, continuing the perpetuation of Cary’s idea that change must be embraced rather than rejected. “Shorter and shorter now the twilight clips/The days, as though the sunset gates they crowd”, syntax and diction are used to literally separate different aspects of the progression of time. In an ironic parallel to the literal language, the action of twilight’s “clip” and the subject, “the days,” are cut off from each other into two different lines, emphasizing a sense of jarring and discomfort. Sunset, and Twilight are named, made into distinct entities from the day, dramatizing the shortening of night-time into fall. The dramatic, sudden implications for the change bring to mind the switch between summer and winter, rather than a transitional season like fall—emphasizing the Speaker’s perspective rather than a factual narration of the experience.

She says “the proud meadow-pink hangs down her head/Against the earth’s chilly bosom, witched with frost”. Implying pride and defeat, and the word “witched,” the speaker brings a sense of conflict, morality, and even good versus evil into the transition between seasons. Rather than a smooth, welcome change, the speaker is practically against the coming of fall. The hyperbole present in the poem serves to illustrate the Speaker’s perspective and ideas on the coming of fall, which are characterized by reluctance and hostility to change from comfort.

The topic of this poem, Fall–a season characterized by change and the deconstruction of the spring and summer landscape—is juxtaposed with the final line which evokes the season of Spring. From this, it is clear that the speaker appreciates beautiful and blossoming change. However, they resent that which destroys familiar paradigms and norms. Fall, seen as the death of summer, is characterized as a regression, though the turning of seasons is a product of the literal passage of time. Utilizing romantic imagery and hyperbole to shape the Speaker’s perspective, Cary emphasizes the need to embrace change though it is difficult, because growth is not possible without hardship or discomfort.

Scoring Criteria: Why did this essay do so well?

When it comes to scoring well, there are some rather formulaic things that the judges are searching for. You might think that it’s important to “stand out” or “be creative” in your writing. However, aside from concerns about “sophistication,” which essentially means you know how to organize thoughts into sentences and you can use language that isn’t entirely elementary, you should really focus on sticking to a form. This will show the scorers that you know how to follow that inductive/deductive reasoning process that we mentioned earlier, and it will help to present your ideas in the most clear, coherent way possible to someone who is reading and scoring hundreds of essays.

So, how did this essay succeed? And how can you do the same thing?

First: The Thesis

On the exam, you can either get one point or zero points for your thesis statement. The scorers said, “The essay responds to the prompt with a defensible thesis located in the introductory paragraph,” which you can read as the first sentence in the essay. This is important to note: you don’t need a flowery hook to seduce your reader; you can just start this brief essay with some strong, simple, declarative sentences—or go right into your thesis.

What makes a good thesis? A good thesis statement does the following things:

- Makes a claim that will be supported by evidence

- Is specific and precise in its use of language

- Argues for an original thought that goes beyond a simple restating of the facts

If you’re sitting here scratching your head wondering how you come up with a thesis statement off the top of your head, let me give you one piece of advice: don’t.

The AP Lit scoring criteria gives you only one point for the thesis for a reason: they’re just looking for the presence of a defensible claim that can be proven by evidence in the rest of the essay.

Second: Write your essay from the inside out

While the thesis is given one point, the form and content of the essay can receive anywhere from zero to four points. This is where you should place the bulk of your focus.

My best advice goes like this:

- Choose your evidence first

- Develop your commentary about the evidence

- Then draft your thesis statement based on the evidence that you find and the commentary you can create.

It will seem a little counterintuitive: like you’re writing your essay from the inside out. But this is a fundamental skill that will help you in college and beyond. Don’t come up with an argument out of thin air and then try to find evidence to support your claim. Look for the evidence that exists and then ask yourself what it all means. This will also keep you from feeling stuck or blocked at the beginning of the essay. If you prepare for the exam by reviewing the literary devices that you learned in the course and practice locating them in a text, you can quickly and efficiently read a literary passage and choose two or three literary devices that you can analyze.

Third: Use scratch paper to quickly outline your evidence and commentary

Once you’ve located two or three literary devices at work in the given passage, use scratch paper to draw up a quick outline. Give each literary device a major bullet point. Then, briefly point to the quotes/evidence you’ll use in the essay. Finally, start to think about what the literary device and evidence are doing together. Try to answer the question: what meaning does this bring to the passage?

A sample outline for one paragraph of the above essay might look like this:

Romantic imagery

Portrayal of summer

- Woman who “from her golden collar… moans aloud”

- Summer as bounty

Contrast with Autumn

- Autumn dismantles Summer

- “Stray through stubble fields”

- Autumn is change; it has the power to dethrone the romance of Summer/make summer a bit meaningless

Recognition of change in a positive light

- Summer “lies on pillows / yellow leaves / tries old tunes”

- Bright imagery/fallen leaves

- Attempt to maintain old practices fails: “old tunes”

- But! There is sympathy: “lies on pillows”

Speaker recognizes: she can’t prevent what is to come; wishes to embrace natural passage of time

By the time the writer gets to the end of the outline for their paragraph, they can easily start to draw conclusions about the paragraph based on the evidence they have pulled out. You can see how that thinking might develop over the course of the outline.

Then, the speaker would take the conclusions they’ve drawn and write a “mini claim” that will start each paragraph. The final bullet point of this outline isn’t the same as the mini claim that comes at the top of the second paragraph of the essay, however, it is the conclusion of the paragraph. You would do well to use the concluding thoughts from your outline as the mini claim to start your body paragraph. This will make your paragraphs clear, concise, and help you to construct a coherent argument.

Repeat this process for the other one or two literary devices that you’ve chosen to analyze, and then: take a step back.

Fourth: Draft your thesis

Once you quickly sketch out your outline, take a moment to “stand back” and see what you’ve drafted. You’ll be able to see that, among your two or three literary devices, you can draw some commonality. You might be able to say, as the writer did here, that romantic and hyperbolic imagery “illustrate the speaker’s unenthusiastic opinion of the coming of autumn,” ultimately illuminating the poet’s idea “that change is difficult to accept but necessary for growth.”

This is an original argument built on the evidence accumulated by the student. It directly answers the prompt by discussing literary techniques that “convey the speaker’s complex response to the changing seasons.” Remember to go back to the prompt and see what direction they want you to head with your thesis, and craft an argument that directly speaks to that prompt.

Then, move ahead to finish your body paragraphs and conclusion.

Fifth: Give each literary device its own body paragraph

In this essay, the writer examines the use of two literary devices that are supported by multiple pieces of evidence. The first is “romantic imagery” and the second is “hyperbolic imagery.” The writer dedicates one paragraph to each idea. You should do this, too.

This is why it’s important to choose just two or three literary devices. You really don’t have time to dig into more. Plus, more ideas will simply cloud the essay and confuse your reader.

Using your outline, start each body paragraph with a “mini claim” that makes an argument about what it is you’ll be saying in your paragraph. Lay out your pieces of evidence, then provide commentary for why your evidence proves your point about that literary device.

Move onto the next literary device, rinse, and repeat.

Sixth: Commentary and Conclusion

Finally, you’ll want to end this brief essay with a concluding paragraph that restates your thesis, briefly touches on your most important points from each body paragraph, and includes a development of the argument that you laid out in the essay.

In this particular example essay, the writer concludes by saying, “Utilizing romantic imagery and hyperbole to shape the Speaker’s perspective, Cary emphasizes the need to embrace change though it is difficult, because growth is not possible without hardship or discomfort.” This is a direct restatement of the thesis. At this point, you’ll have reached the end of your essay. Great work!

Seventh: Sophistication

A final note on scoring criteria: there is one point awarded to what the scoring criteria calls “sophistication.” This is evidenced by the sophistication of thought and providing a nuanced literary analysis, which we’ve already covered in the steps above.

There are some things to avoid, however:

- Sweeping generalizations, such as, “From the beginning of human history, people have always searched for love,” or “Everyone goes through periods of darkness in their lives, much like the writer of this poem.”

- Only hinting at possible interpretations instead of developing your argument

- Oversimplifying your interpretation

- Or, by contrast, using overly flowery or complex language that does not meet your level of preparation or the context of the essay.

Remember to develop your argument with nuance and complexity and to write in a style that is academic but appropriate for the task at hand.

If you want more practice or to check out other exams from the past, go to the College Board’s website .

Brittany Borghi

After earning a BA in Journalism and an MFA in Nonfiction Writing from the University of Iowa, Brittany spent five years as a full-time lecturer in the Rhetoric Department at the University of Iowa. Additionally, she’s held previous roles as a researcher, full-time daily journalist, and book editor. Brittany’s work has been featured in The Iowa Review, The Hopkins Review, and the Pittsburgh City Paper, among others, and she was also a 2021 Pushcart Prize nominee.

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Essay

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High School Success

- High Schools

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Private High School Spotlight

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

Sign Up Now

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write the AP Lit Prose Essay + Example

Do you know how to improve your profile for college applications.

See how your profile ranks among thousands of other students using CollegeVine. Calculate your chances at your dream schools and learn what areas you need to improve right now — it only takes 3 minutes and it's 100% free.

Show me what areas I need to improve

What’s Covered

What is the ap lit prose essay, how will ap scores affect my college chances.

AP Literature and Composition (AP Lit), not to be confused with AP English Language and Composition (AP Lang), teaches students how to develop the ability to critically read and analyze literary texts. These texts include poetry, prose, and drama. Analysis is an essential component of this course and critical for the educational development of all students when it comes to college preparation. In this course, you can expect to see an added difficulty of texts and concepts, similar to the material one would see in a college literature course.

While not as popular as AP Lang, over 380,136 students took the class in 2019. However, the course is significantly more challenging, with only 49.7% of students receiving a score of three or higher on the exam. A staggeringly low 6.2% of students received a five on the exam.

The AP Lit exam is similar to the AP Lang exam in format, but covers different subject areas. The first section is multiple-choice questions based on five short passages. There are 55 questions to be answered in 1 hour. The passages will include at least two prose fiction passages and two poetry passages and will account for 45% of your total score. All possible answer choices can be found within the text, so you don’t need to come into the exam with prior knowledge of the passages to understand the work.

The second section contains three free-response essays to be finished in under two hours. This section accounts for 55% of the final score and includes three essay questions: the poetry analysis essay, the prose analysis essay, and the thematic analysis essay. Typically, a five-paragraph format will suffice for this type of writing. These essays are scored holistically from one to six points.

Today we will take a look at the AP Lit prose essay and discuss tips and tricks to master this section of the exam. We will also provide an example of a well-written essay for review.

The AP Lit prose essay is the second of the three essays included in the free-response section of the AP Lit exam, lasting around 40 minutes in total. A prose passage of approximately 500 to 700 words and a prompt will be given to guide your analytical essay. Worth about 18% of your total grade, the essay will be graded out of six points depending on the quality of your thesis (0-1 points), evidence and commentary (0-4 points), and sophistication (0-1 points).

While this exam seems extremely overwhelming, considering there are a total of three free-response essays to complete, with proper time management and practiced skills, this essay is manageable and straightforward. In order to enhance the time management aspect of the test to the best of your ability, it is essential to understand the following six key concepts.

1. Have a Clear Understanding of the Prompt and the Passage

Since the prose essay is testing your ability to analyze literature and construct an evidence-based argument, the most important thing you can do is make sure you understand the passage. That being said, you only have about 40 minutes for the whole essay so you can’t spend too much time reading the passage. Allot yourself 5-7 minutes to read the prompt and the passage and then another 3-5 minutes to plan your response.

As you read through the prompt and text, highlight, circle, and markup anything that stands out to you. Specifically, try to find lines in the passage that could bolster your argument since you will need to include in-text citations from the passage in your essay. Even if you don’t know exactly what your argument might be, it’s still helpful to have a variety of quotes to use depending on what direction you take your essay, so take note of whatever strikes you as important. Taking the time to annotate as you read will save you a lot of time later on because you won’t need to reread the passage to find examples when you are in the middle of writing.

Once you have a good grasp on the passage and a solid array of quotes to choose from, you should develop a rough outline of your essay. The prompt will provide 4-5 bullets that remind you of what to include in your essay, so you can use these to structure your outline. Start with a thesis, come up with 2-3 concrete claims to support your thesis, back up each claim with 1-2 pieces of evidence from the text, and write a brief explanation of how the evidence supports the claim.

2. Start with a Brief Introduction that Includes a Clear Thesis Statement

Having a strong thesis can help you stay focused and avoid tangents while writing. By deciding the relevant information you want to hit upon in your essay up front, you can prevent wasting precious time later on. Clear theses are also important for the reader because they direct their focus to your essential arguments.

In other words, it’s important to make the introduction brief and compact so your thesis statement shines through. The introduction should include details from the passage, like the author and title, but don’t waste too much time with extraneous details. Get to the heart of your essay as quick as possible.

3. Use Clear Examples to Support Your Argument

One of the requirements AP Lit readers are looking for is your use of evidence. In order to satisfy this aspect of the rubric, you should make sure each body paragraph has at least 1-2 pieces of evidence, directly from the text, that relate to the claim that paragraph is making. Since the prose essay tests your ability to recognize and analyze literary elements and techniques, it’s often better to include smaller quotes. For example, when writing about the author’s use of imagery or diction you might pick out specific words and quote each word separately rather than quoting a large block of text. Smaller quotes clarify exactly what stood out to you so your reader can better understand what are you saying.

Including smaller quotes also allows you to include more evidence in your essay. Be careful though—having more quotes is not necessarily better! You will showcase your strength as a writer not by the number of quotes you manage to jam into a paragraph, but by the relevance of the quotes to your argument and explanation you provide. If the details don’t connect, they are merely just strings of details.

4. Discussion is Crucial to Connect Your Evidence to Your Argument

As the previous tip explained, citing phrases and words from the passage won’t get you anywhere if you don’t provide an explanation as to how your examples support the claim you are making. After each new piece of evidence is introduced, you should have a sentence or two that explains the significance of this quote to the piece as a whole.

This part of the paragraph is the “So what?” You’ve already stated the point you are trying to get across in the topic sentence and shared the examples from the text, so now show the reader why or how this quote demonstrates an effective use of a literary technique by the author. Sometimes students can get bogged down by the discussion and lose sight of the point they are trying to make. If this happens to you while writing, take a step back and ask yourself “Why did I include this quote? What does it contribute to the piece as a whole?” Write down your answer and you will be good to go.

5. Write a Brief Conclusion

While the critical part of the essay is to provide a substantive, organized, and clear argument throughout the body paragraphs, a conclusion provides a satisfying ending to the essay and the last opportunity to drive home your argument. If you run out of time for a conclusion because of extra time spent in the preceding paragraphs, do not worry, as that is not fatal to your score.

Without repeating your thesis statement word for word, find a way to return to the thesis statement by summing up your main points. This recap reinforces the arguments stated in the previous paragraphs, while all of the preceding paragraphs successfully proved the thesis statement.

6. Don’t Forget About Your Grammar

Though you will undoubtedly be pressed for time, it’s still important your essay is well-written with correct punctuating and spelling. Many students are able to write a strong thesis and include good evidence and commentary, but the final point on the rubric is for sophistication. This criteria is more holistic than the former ones which means you should have elevated thoughts and writing—no grammatical errors. While a lack of grammatical mistakes alone won’t earn you the sophistication point, it will leave the reader with a more favorable impression of you.

Discover your chances at hundreds of schools

Our free chancing engine takes into account your history, background, test scores, and extracurricular activities to show you your real chances of admission—and how to improve them.

[amp-cta id="9459"]

Here are Nine Must-have Tips and Tricks to Get a Good Score on the Prose Essay:

- Carefully read, review, and underline key instruction s in the prompt.

- Briefly outlin e what you want to cover in your essay.

- Be sure to have a clear thesis that includes the terms mentioned in the instructions, literary devices, tone, and meaning.

- Include the author’s name and title in your introduction. Refer to characters by name.

- Quality over quantity when it comes to picking quotes! Better to have a smaller number of more detailed quotes than a large amount of vague ones.

- Fully explain how each piece of evidence supports your thesis .

- Focus on the literary techniques in the passage and avoid summarizing the plot.

- Use transitions to connect sentences and paragraphs.

- Keep your introduction and conclusion short, and don’t repeat your thesis verbatim in your conclusion.

Here is an example essay from 2020 that received a perfect 6:

[1] In this passage from a 1912 novel, the narrator wistfully details his childhood crush on a girl violinist. Through a motif of the allure of musical instruments, and abundant sensory details that summon a vivid image of the event of their meeting, the reader can infer that the narrator was utterly enraptured by his obsession in the moment, and upon later reflection cannot help but feel a combination of amusement and a resummoning of the moment’s passion.

[2] The overwhelming abundance of hyper-specific sensory details reveals to the reader that meeting his crush must have been an intensely powerful experience to create such a vivid memory. The narrator can picture the “half-dim church”, can hear the “clear wail” of the girl’s violin, can see “her eyes almost closing”, can smell a “faint but distinct fragrance.” Clearly, this moment of discovery was very impactful on the boy, because even later he can remember the experience in minute detail. However, these details may also not be entirely faithful to the original experience; they all possess a somewhat mysterious quality that shows how the narrator may be employing hyperbole to accentuate the girl’s allure. The church is “half-dim”, the eyes “almost closing” – all the details are held within an ethereal state of halfway, which also serves to emphasize that this is all told through memory. The first paragraph also introduces the central conciet of music. The narrator was drawn to the “tones she called forth” from her violin and wanted desperately to play her “accompaniment.” This serves the double role of sensory imagery (with the added effect of music being a powerful aural image) and metaphor, as the accompaniment stands in for the narrator’s true desire to be coupled with his newfound crush. The musical juxtaposition between the “heaving tremor of the organ” and the “clear wail” of her violin serves to further accentuate how the narrator percieved the girl as above all other things, as high as an angel. Clearly, the memory of his meeting his crush is a powerful one that left an indelible impact on the narrator.

[3] Upon reflecting on this memory and the period of obsession that followed, the narrator cannot help but feel amused at the lengths to which his younger self would go; this is communicated to the reader with some playful irony and bemused yet earnest tone. The narrator claims to have made his “first and last attempts at poetry” in devotion to his crush, and jokes that he did not know to be “ashamed” at the quality of his poetry. This playful tone pokes fun at his childhood self for being an inexperienced poet, yet also acknowledges the very real passion that the poetry stemmed from. The narrator goes on to mention his “successful” endeavor to conceal his crush from his friends and the girl; this holds an ironic tone because the narrator immediately admits that his attempts to hide it were ill-fated and all parties were very aware of his feelings. The narrator also recalls his younger self jumping to hyperbolic extremes when imagining what he would do if betrayed by his love, calling her a “heartless jade” to ironically play along with the memory. Despite all this irony, the narrator does also truly comprehend the depths of his past self’s infatuation and finds it moving. The narrator begins the second paragraph with a sentence that moves urgently, emphasizing the myriad ways the boy was obsessed. He also remarks, somewhat wistfully, that the experience of having this crush “moved [him] to a degree which now [he] can hardly think of as possible.” Clearly, upon reflection the narrator feels a combination of amusement at the silliness of his former self and wistful respect for the emotion that the crush stirred within him.

[4] In this passage, the narrator has a multifaceted emotional response while remembering an experience that was very impactful on him. The meaning of the work is that when we look back on our memories (especially those of intense passion), added perspective can modify or augment how those experiences make us feel

More essay examples, score sheets, and commentaries can be found at College Board .

While AP Scores help to boost your weighted GPA, or give you the option to get college credit, AP Scores don’t have a strong effect on your admissions chances . However, colleges can still see your self-reported scores, so you might not want to automatically send scores to colleges if they are lower than a 3. That being said, admissions officers care far more about your grade in an AP class than your score on the exam.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

AP® English Literature

How to get a 9 on prose analysis frq in ap® english literature.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: March 1, 2022

When it’s time to take the AP® English Literature and Composition exam, will you be ready? If you’re aiming high, you’ll want to know the best route to a five on the AP® exam. You know the exam is going to be tough, so how do prepare for success? To do well on the AP® English Literature and Composition exam, you’ll need to score high on the essays. For that, you’ll need to write a competent, efficient essay that argues an accurate interpretation of the work under examination in the Free Response Question section.

The AP® English Literature and Composition exam consists of two sections, the first being a 55-question multiple choice portion worth 45% of the total test grade. This section tests your ability to read drama, verse, or prose fiction excerpts and answer questions about them. The second section, worth 55% of the total score, requires essay responses to three questions demonstrating your ability to analyze literary works. You’ll have to discuss a poem analysis, a prose fiction passage analysis, and a concept, issue, or element analysis of a literary work–in two hours.

Before the exam, you should know how to construct a clear, organized essay that defends a focused claim about the work under analysis. You must write a brief introduction that includes the thesis statement, followed by body paragraphs that further the thesis statement with detailed, thorough support, and a short concluding paragraph that reiterates and reinforces the thesis statement without repeating it. Clear organization, specific support, and full explanations or discussions are three critical components of high-scoring essays.

General Tips to Bettering Your Odds at a Nine on the AP® English Literature Prose FRQ

You may know already how to approach the prose analysis, but don’t forget to keep the following in mind coming into the exam:

- Carefully read, review, and underline key to-do’s in the prompt.

- Briefly outline where you’re going to hit each prompt item — in other words, pencil out a specific order.

- Be sure you have a clear thesis that includes the terms mentioned in the instructions, literary devices, tone, and meaning.

- Include the author’s name and title of the prose selection in your thesis statement. Refer to characters by name.

- Use quotes — lots of them — to exemplify the elements and your argument points throughout the essay.

- Fully explain or discuss how your examples support your thesis. A deeper, fuller, and more focused explanation of fewer elements is better than a shallow discussion of more elements (shotgun approach).

- Avoid vague, general statements or merely summarizing the plot instead of clearly focusing on the prose passage itself.

- Use transitions to connect sentences and paragraphs.

- Write in the present tense with generally good grammar.

- Keep your introduction and conclusion short, and don’t repeat your thesis verbatim in your conclusion.

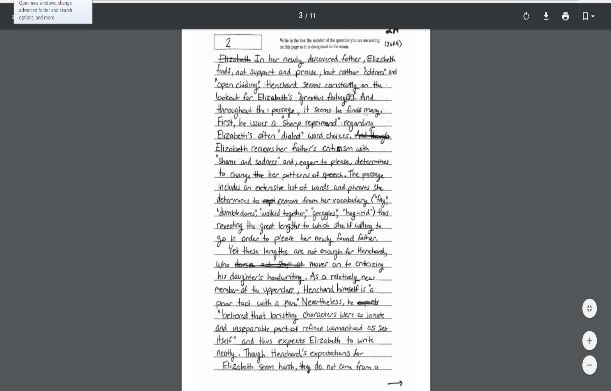

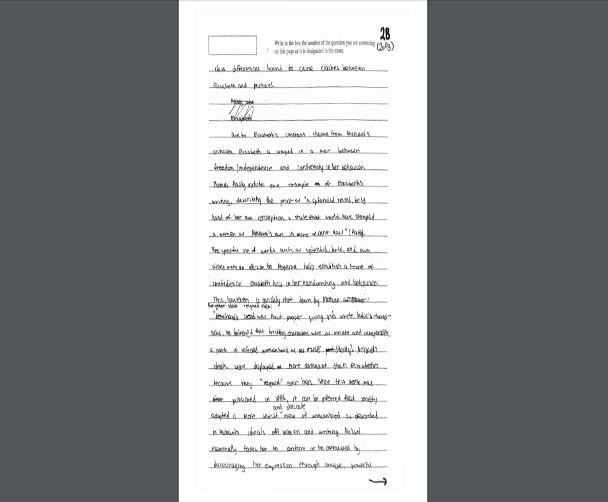

The newly-released 2016 sample AP® English Literature and Composition exam questions, sample responses, and grading rubrics provide a valuable opportunity to analyze how to achieve high scores on each of the three Section II FRQ responses. However, for purposes of this examination, the Prose Analysis FRQ strategies will be the focus. The prose selection for analysis in last year’s exam was Thomas Hardy’s The Mayor of Casterbridge , a 19th-century novel. Exam takers had to respond to the following instructions:

- Analyze the complex relationship between the two characters Hardy portrays in the passage.

- Pay attention to tone, word choice, and detail selection.

- Write a well-written essay.

For a clear understanding of the components of a model essay, you’ll find it helpful to analyze and compare all three sample answers provided by the CollegeBoard: the high scoring (A) essay, the mid-range scoring (B) essay, and the low scoring (C) essay. All three provide a lesson for you: to achieve a nine on the prose analysis essay, model the ‘A’ essay’s strengths and avoid the weaknesses of the other two.

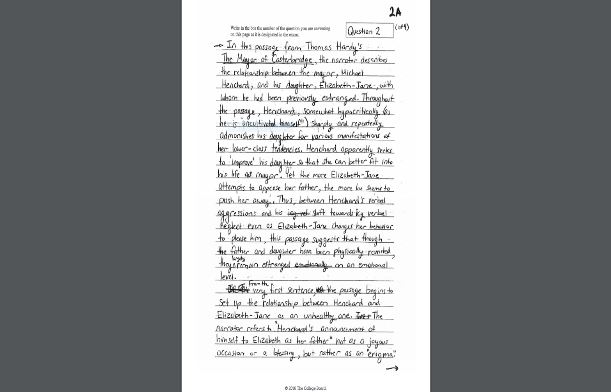

Start with a Succinct Introduction that Includes Your Thesis Statement

The first sample essay (A) begins with a packed first sentence: the title of the work, author, named characters, and the subject alluded to in the prompt that will form the foundation of the upcoming argument — the strained relationship between father and daughter. Then, after summarizing the context of the passage — that tense relationship — the student quotes relevant phrases (“lower-class”, “verbal aggressions”) that depict the behavior and character of each.

By packing each sentence efficiently with details (“uncultivated”, “hypocritical”) on the way to the thesis statement, the writer controls the argument by folding in only the relevant details that support the claim at the end of the introduction: though reunited physically, father and daughter remain separated emotionally. The writer wastes no words and quickly directs the reader’s focus to the characters’ words and actions that define their estranged relationship. From the facts cited, the writer’s claim or thesis is logical.

The mid-range B essay introduction also mentions the title, author, and relationship (“strange relationship”) that the instructions direct the writer to examine. However, the student neither names the characters nor identifies what’s “strange” about the relationship. The essay needs more specific details to clarify the complexity in the relationship. Instead, the writer merely hints at that complexity by stating father and daughter “try to become closer to each other’s expectations”. There’s no immediately clear correlation between the “reunification” and the expectations. Finally, the student wastes time and space in the first two sentences with a vague platitude for an “ice breaker” to start the essay. It serves no other function.

The third sample lacks cohesiveness, focus, and a clear thesis statement. The first paragraph introduces the writer’s feelings about the characters and how the elements in the story helped the student analyze, both irrelevant to the call of the instructions. The introduction gives no details of the passage: no name, title, characters, or relationship. The thesis statement is shallow–the daughter was better off before she reunited with her father–as it doesn’t even hint at the complexity of the relationship. The writer merely parrots the prompt instructions about “complex relationship” and “speaker’s tone, word choice, and selection of detail”.

In sum, make introductions brief and compact. Use specific details from the passage that support a logical thesis statement which clearly directs the argument and addresses the instructions’ requirements. Succinct writing helps. Pack your introduction with specific excerpt details, and don’t waste time on sentences that don’t do the work ahead for you. Be sure the thesis statement covers all of the relevant facts of the passage for a cohesive argument.

Use Clear Examples to Support Your Argument Points

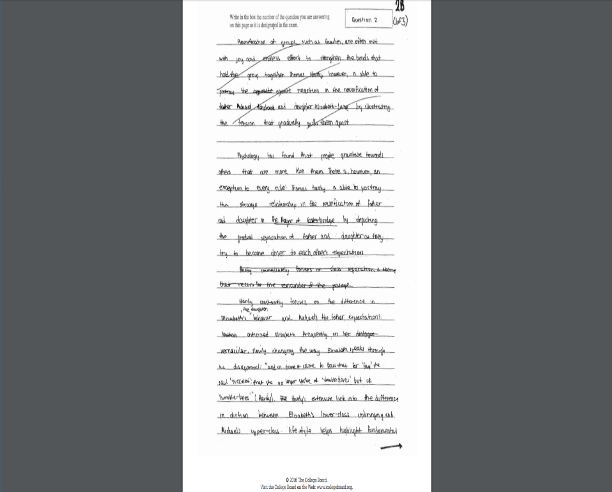

The A answer supports the thesis by qualifying the relationship as unhealthy in the first sentence. Then the writer includes the quoted examples that contrast what one would expect characterizes a father-daughter relationship — joyous, blessing, support, praise — against the reality of Henchard and Elizabeth’s relationship: “enigma”, “coldness”, and “open chiding”.

These and other details in the thorough first body paragraph leave nothing for the reader to misunderstand. The essayist proves the paragraph’s main idea with numerous examples. The author controls the first argument point that the relationship is unhealthy by citing excerpted words and actions of the two characters demonstrating the father’s aggressive disapproval and the daughter’s earnestness and shame.

The second and third body paragraphs not only add more proof of the strained relationship in the well-chosen example of the handwriting incident but also explore the underlying motives of the father. In suggesting the father has good intentions despite his outward hostility, the writer proposes that Henchard wants to elevate his long-lost daughter. Henchard’s declaration that handwriting “with bristling characters” defines refinement in a woman both diminishes Elizabeth and reveals his silent hope for her, according to the essayist. This contradiction clearly proves the relationship is “complex”.

The mid-range sample also cites specific details: the words Elizabeth changes (“fay” for “succeed”) for her father. These details are supposed to support the point that class difference causes conflict between the two. However, the writer leaves it to the reader to make the connection between class, expectations, and word choices. The example of the words Elizabeth eliminates from her vocabulary does not illustrate the writer’s point of class conflict. In fact, the class difference as the cause of their difficulties is never explicitly stated. Instead, the writer makes general, unsupported statements about Hardy’s focus on the language difference without saying why Hardy does that.

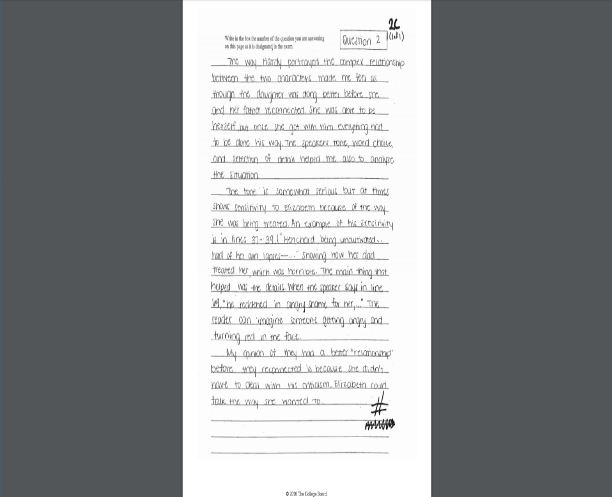

Like the A essay, sample C also alludes to the handwriting incident but only to note that the description of Henchard turning red is something the reader can imagine. In fact, the writer gives other examples of sensitive and serious tones in the passage but then doesn’t completely explain them. None of the details noted refer to a particular point that supports a focused paragraph. The details don’t connect. They’re merely a string of details.

Discussion is Crucial to Connect Your Quotes and Examples to Your Argument Points

Rather than merely citing phrases and lines without explanation, as the C sample does, the A response spends time thoroughly discussing the meaning of the quoted words, phrases, and sentences used to exemplify their assertions. For example, the third paragraph begins with the point that Henchard’s attempts to elevate Elizabeth in order to better integrate her into the mayor’s “lifestyle” actually do her a disservice. The student then quotes descriptive phrases that characterize Elizabeth as “considerate”, notes her successfully fulfilling her father’s expectations of her as a woman, and concludes that success leads to her failure to get them closer — to un-estrange him.

The A sample writer follows the same pattern throughout the essay: assertion, example, explanation of how the example and assertion cohere, tying both into the thesis statement. Weaving the well-chosen details into the discussion to make reasonable conclusions about what they prove is the formula for an orderly, coherent argument. The writer starts each paragraph with a topic sentence that supports the thesis statement, followed by a sentence that explains and supports the topic sentence in furtherance of the argument.

On the other hand, the B response begins the second paragraph with a general topic sentence: Hardy focuses on the differences between the daughter’s behavior and the father’s expectations. The next sentence follows up with examples of the words Elizabeth changes, leading to the broad conclusion that class difference causes clashes. They give no explanation to connect the behavior — changing her words — with how the diction reveals class differences exists. Nor does the writer explain the motivations of the characters to demonstrate the role of class distinction and expectations. The student forces the reader to make the connections.

Similarly, in the second example of the handwriting incident, the student sets out to prove Elizabeth’s independence and conformity conflict. However, the writer spends too much time re-telling the writing episode — who said what — only to vaguely conclude that 19th-century gender roles dictated the dominant and submissive roles of father and daughter, resulting in the loss of Elizabeth’s independence. The writer doesn’t make those connections between gender roles, dominance, handwriting, and lost freedom. The cause and effect of the handwriting humiliation to the loss of independence are never made.

Write a Brief Conclusion

While it’s more important to provide a substantive, organized, and clear argument throughout the body paragraphs than it is to conclude, a conclusion provides a satisfying rounding out of the essay and last opportunity to hammer home the content of the preceding paragraphs. If you run out of time for a conclusion because of the thorough preceding paragraphs, that is not as fatal to your score as not concluding or not concluding as robustly as the A essay sample.

The A response not only provides another example of the father-daughter inverse relationship — the more he helps her fit in, the more estranged they become — but also ends where the writer began: though they’re physically reunited, they’re still emotionally separated. Without repeating it verbatim, the student returns to the thesis statement at the end. This return and recap reinforce the focus and control of the argument when all of the preceding paragraphs successfully proved the thesis statement.

The B response nicely ties up the points necessary to satisfy the prompt had the writer made them clearly. The parting remarks about the inverse relationship building up and breaking down to characterize the complex relationship between father and daughter are intriguing but not well-supported by all that came before them.

Write in Complete Sentences with Proper Punctuation and Compositional Skills

Though pressed for time, it’s important to write an essay with crisp, correctly punctuated sentences and properly spelled words. Strong compositional skills create a favorable impression to the reader, like using appropriate transitions or signals (however, therefore) to tie sentences and paragraphs together, and making the relationships between sentences clear (“also” — adding information, “however” — contrasting an idea in the preceding sentence).

Starting each paragraph with a clear, focused topic sentence that previews the main idea or focus of the paragraph helps you the writer and the reader keep track of each part of your argument. Each section furthers your points on the way to convincing your reader of your argument. If one point is unclear, unfocused, or grammatically unintelligible, like a house of cards, the entire argument crumbles. Excellent compositional skills help you lay it all out neatly, clearly, and fully.

For example, the A response begins the essay with “In this passage from Thomas Hardy”. The second sentence follows with “Throughout the passage” to tie the two sentences together. There’s no question that the two thoughts link by the transitional phrases that repeat and reinforce one another as well as direct the reader’s attention. The B response, however, uses transitions less frequently, confuses the names of the characters, and switches verb tenses in the essay. It’s harder to follow.

So by the time the conclusion takes the reader home, the high-scoring writer has done all of the following:

- followed the prompt

- followed the propounded thesis statement and returned to it in the end

- provided a full discussion with examples

- included quotes proving each assertion

- used clear, grammatically correct sentences

- wrote paragraphs ordered by a thesis statement

- created topic sentences for each paragraph

- ensured each topic sentence furthered the ideas presented in the thesis statement

Have a Plan and Follow it

To get a nine on the prose analysis FRQ essay in the AP® Literature and Composition exam, you should practice timed essays. Write as many practice essays as you can. Follow the same procedure each time. After reading the prompt, map out your thesis statement, paragraph topic sentences, and supporting details and quotes in the order of their presentation. Then follow your plan faithfully.

Be sure to leave time for a brief review to catch mechanical errors, missing words, or clarifications of an unclear thought. With time, an organized approach, and plenty of practice, earning a nine on the poetry analysis is manageable. Be sure to ask your teacher or consult other resources, like albert.io’s Prose Analysis practice essays, for questions and more practice opportunities.

Looking for AP® English Literature practice?

Kickstart your AP® English Literature prep with Albert. Start your AP® exam prep today .

Interested in a school license?

Popular posts.

AP® Score Calculators

Simulate how different MCQ and FRQ scores translate into AP® scores

AP® Review Guides

The ultimate review guides for AP® subjects to help you plan and structure your prep.

Core Subject Review Guides

Review the most important topics in Physics and Algebra 1 .

SAT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall SAT® score

ACT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall ACT® score

Grammar Review Hub

Comprehensive review of grammar skills

AP® Posters

Download updated posters summarizing the main topics and structure for each AP® exam.

Interested in a school license?

Bring Albert to your school and empower all teachers with the world's best question bank for: ➜ SAT® & ACT® ➜ AP® ➜ ELA, Math, Science, & Social Studies aligned to state standards ➜ State assessments Options for teachers, schools, and districts.

Any writer looking to master the art of storytelling will want to learn the literary devices in prose. Fiction and nonfiction writers rely on these devices to bring their stories to life, impact their readers, and uncover the core truths of life. You can, too, with mastery over the different literary devices!

If you’re not familiar with the common literary devices, start with this article for definitions and examples. You may also benefit from brushing up on the six elements of fiction , as most prose stories have them. Combined with the following literary devices in fiction and nonfiction, these framing elements can help you write a powerful story.

10 Important Literary Devices in Prose

We’ve included examples and explanations for each of these devices, pulling from both contemporary and classical literature. Whether you’re a writer, a student, or a literary connoisseur, familiarize yourself with the important literary devices in prose.

1. Parallelism (Parallel Plots)

Parallelism refers to the plotting of events that are similarly constructed but altogether separate.

Are you familiar with the phrase “history often repeats itself”? If so, then you’re already familiar with parallelism. Parallelism refers to the plotting of events that are similarly constructed but altogether separate. Sometimes these parallels develop on accident, but they are powerful tools for highlighting important events and themes.

A surprising example of parallelism comes in the form of the Harry Potter series. As an infant, Harry is almost killed by Voldemort but is protected by his mother’s love. Eighteen years later, Harry must die in order to defeat Voldemort, thus shouldering the burden of love himself.

What does this parallelism do for the story? Certainly, that’s open to interpretation. Perhaps it draws attention to the incompleteness of love without action: to defeat Voldemort (who personifies hatred), Harry can’t just be loved, he has to act on love—by sacrificing his own life, no less.

This is unrelated to grammatical parallelism , a different literary device.

2. Foil Characters

A foil refers to any two characters who are “opposites” of each other.

A foil refers to any two characters who are “opposites” of each other. These oppositions are often conceptual in nature: one character may be even-keeled and mild, like Benvolio in Romeo & Juliet, while another character may be quick-tempered and pugnacious, like Tybalt.

What do foil characters accomplish? In Romeo & Juliet , Benvolio and Tybalt are basically Romeo’s devil and angel. Benvolio discourages Romeo from fighting, as it would surely end in his own death and separation from Juliet, whereas Tybalt encourages fighting out of family loyalty.

Of course, foils can also be the protagonist and antagonist, especially if they are character opposites. A reader would be hard-pressed to find similarities between Harry Potter and Voldemort (except for their shared soul). If you can think of other embodiments of good versus evil, they are most assuredly foils as well.

Foil characters help establish important themes and binaries in your work.

Foil characters help establish important themes and binaries in your work. Because Shakespeare wrote Benvolio and Tybalt as foils, one of the themes in Romeo & Juliet is that of retribution: is it better to fight for honor or turn the other cheek for love?

When considering foil characters in your writing, consider which themes/morals you want to turn your attention towards. If you want to write about the theme of chaos versus order, and your protagonist is chaotic, you might want a foil character who’s orderly. If you want to write about this theme but it’s not central to the story, perhaps have two side characters represent chaos versus order.

Learn more about foil characters here:

What is a Foil Character? Exploring Contrast in Character Development

You’ll often hear that “diction” is just a fancy term for “word choice.” While this is true, it’s also reductive, and it doesn’t capture the full importance of select words in your story. Diction is one of the most important literary devices in prose, as every prose writer will use it.

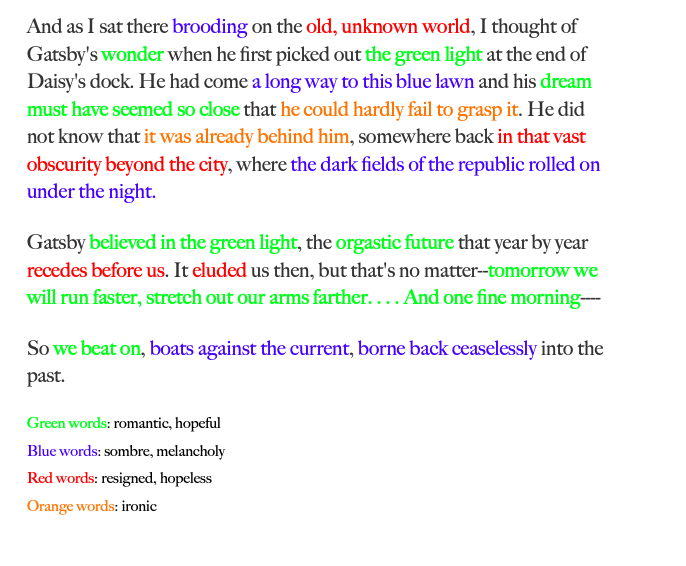

Diction is best demonstrated through analyzing a passage of prose, so to see diction in action, let’s take apart the closing paragraphs of The Great Gatsby .

Take a look at the highlighted words, as well as the opposition between different highlights. F. Scott Fitzgerald juxtaposes many different emotions in this short, poignant passage, resulting in an ambivalent yet powerful musing on the passage of time. By focusing the diction of this passage on emotions both hopeful and hopeless, Fitzgerald masterfully closes one of the most important American novels.

For a further analysis of diction, as well as some great examples, check out our article expanding upon word choice in writing !

The mood of a story or passage refers to the overall emotional tone it invokes.

The mood of a story or passage refers to the overall emotional tone it invokes. When writers craft a mood in their work, they’re heightening the experience of their story by putting you in the characters’ shoes. Since mood requires using the right words throughout a scene, mood can be considered an extended form of diction.

The writer cultivates mood by making consistent language choices throughout a passage.

The writer cultivates mood by making consistent language choices throughout a passage of the story. Take, for example, the cliché “it was a dark and stormy night.” That phrase wasn’t clichéd when it was first written; in fact, it did a great job of opening Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s novel Paul Clifford . The narrator’s dark, bleak description of the weather brings the reader into the bleary, tumultuous life of its protagonist, building a mood in both setting and story.

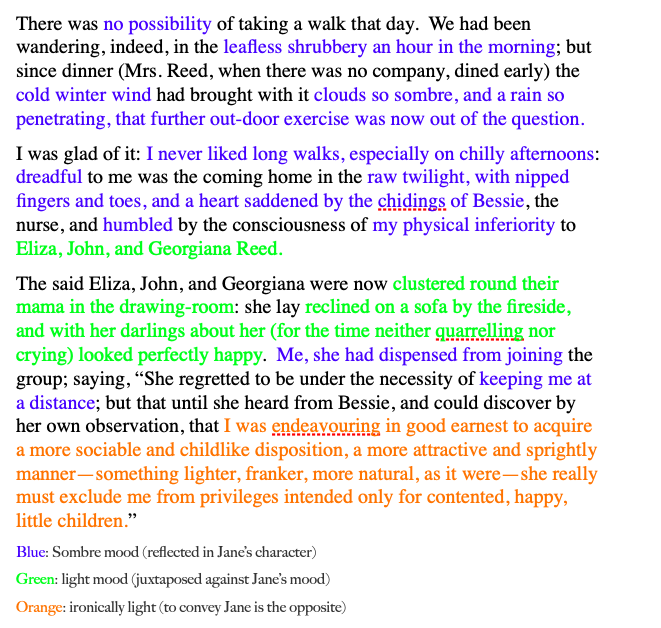

Or, consider this excerpt from Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë:

Charlotte is quick to build the mood, keying in on Jane’s sombre beginnings before juxtaposing it against the ironic perfection of her siblings. Jane’s world is clear from the beginning: a cloudy house amidst a sunny street.

Learn more about this device at our article on mood in literature.

What is Mood in Literature? Creating Mood in Writing

5. Foreshadowing

A foreshadow refers to any time the writer hints towards later events in the story.

Foreshadowing is a powerful literary device in fiction, drawing readers ever-closer to the story’s climax. A foreshadow refers to any time the writer hints towards later events in the story, often underscoring the story’s suspense and conflict.

Sometimes foreshadowing is obvious, and sometimes you don’t notice it until rereading the story.

Sometimes foreshadowing is obvious, and sometimes you don’t notice it until rereading the story. For example, the foreshadowing in Harry Potter makes it fairly obvious that Harry will have to die. Once the idea of horcruxes, or “split souls,” was introduced in the books, it was only a matter of time before readers connected these horcruxes to the psychic connection Harry shared with Voldemort. His mission—to die and be reincarnated—becomes fairly obvious as the heptalogy comes to a close.

However, sometimes foreshadowing is much more discreet. In Jane Eyre , for example, it’s clear that many of the people in Jane’s life are keeping secrets from her. Rochester doesn’t let anyone know about his previous marriage but it gets alluded to several times, and St. John is reluctant to admit that he does not actually love Jane, foreshadowing Jane’s return to Rochester. All of this combines to reinforce Jane’s uncertain place in the world and the journey she must take to settle down.

6. In Media Res

In Media Res refers to writing a story starting from the middle

From the Latin “In the middle of things,” In Media Res is one of the literary devices in prose chiefly concerned with plot. In Media Res refers to writing a story starting from the middle; by throwing the reader into the center of events, the reader’s interest piques, and the storytelling bounces between flashback and present day.

Both fiction and nonfiction writers can use In Media Res, provided it makes sense to do so. For example, Margaret Atwood’s A Handmaid’s Tale begins in the middle of a dystopian society. Atwood leads us through the society’s establishment and the narrator’s capture, but all of this is in flashback, because the focus is on navigating the narrator’s escape from this evil world.

In Media Res applies well here, because the reader feels the full intensity of this dystopia from its start. Writers who are writing stories in either alternate worlds or very private worlds may benefit from this literary device in fiction, as it helps keep the reader interested and attentive.

7. Dramatic Irony

Dramatic irony occurs when the audience understands more about the situation than the story’s characters do.

Dramatic irony is a literary device in prose in which the audience understands more about the situation than the story’s characters do. This is an especially important literary device in fiction, as it often motivates the reader to keep reading.

We often see dramatic irony in stories which involve multiple points-of-view.

We often see dramatic irony in stories which involve multiple points-of-view. For example, the audience knows that Juliet is still alive, but when Romeo discovers her seemingly dead body, he kills himself in grief. How ironic, then, for Juliet to wake up to her lover’s passing, only to kill herself in equal grief. By using dramatic irony in the story, Shakespeare points towards the haphazardness of young love.

8. Vignette

A vignette is a passage of prose that’s primarily descriptive, rather than plot-driven.

A vignette (vin-yet) refers to a passage of prose that’s primarily descriptive, rather than plot-driven. Vignettes throw the reader into the scene and emotion, often building the mood of the story and developing the character’s lens. They are largely poetic passages with little plot advancement, but the flourishes of a well-written vignette can highlight your writing style and the story’s emotions.

The story snippets we’ve included are striking examples of vignettes. They don’t advance the plot, but they push the reader into the story’s mood. Additionally, the prose style itself is emotive and poetic, examining the nuances of life’s existential questions.

9. Flashback

A flashback refers to any interruption in the story where the narration goes back in time.

A flashback refers to any interruption in the story where the narration goes back in time. The reader may need information from previous events in order to understand the present-day story, and flashbacks drop the reader into the scene itself.

Flashbacks are often used in stories that begin In Media Res, such as The Handmaid’s Tale. While the main plot of the story focuses on the narrator’s struggles against Gilead, this narration frequently alternates with explanations for how Gilead established itself. The reader gets to see the bombing of Congress, the forced immigration of POC, and the environmental/fertility crisis which gives context for Gilead’s fearmongering. We also experience the narrator’s separation from her daughter and husband, supplying readers with the story’s highly emotive world.

10. Soliloquy

A soliloquy is a long speech with no audience in the story.

Soliloquy comes from the Latin for self (sol) and talking (loquy), and self-talking describes a soliloquy perfectly. A soliloquy is a long speech with no audience in the story. Soliloquies are synonymous with monologues, though a soliloquy is usually a brief passage in a chapter, and often much more poetic.

Shakespeare’s plays abound with soliloquies. Here’s an example, pulled from Scene II Act II of Romeo and Juliet .

But soft, what light through yonder window breaks? It is the East, and Juliet is the sun. Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon, Who is already sick and pale with grief That thou, her maid, art far more fair than she.

Romeo isn’t talking to anyone in particular, but no matter: his soliloquy is rife with emotion and metaphor, and one can’t help but blush when he expresses how his love for Juliet makes her like the sun to him.

As a literary device in prose, soliloquy offers insight into the characters’ emotions. Soliloquy doesn’t have to be in dialogue, it can also take the form of private thoughts, but a soliloquy must be an extended conversation with oneself that exposes the character’s own feelings and ideas.

Write Powerful Literary Devices in Prose with Writers.com

The literary devices in Jane Eyre , Romeo & Juliet, and The Great Gatsby help make these stories masterful works of fiction. By using these literary building blocks, your story will sparkle, too. Take a look at our upcoming courses in fiction and nonfiction , and take the next step in writing the great American novel. Happy writing!

Sean Glatch

So amazing to here, it has helped me

Thanks, it is helpful.💯

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.15: Sample Student Literary Analysis Essays

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 101141

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

The following examples are essays where student writers focused on close-reading a literary work.

While reading these examples, ask yourself the following questions:

- What is the essay's thesis statement, and how do you know it is the thesis statement?

- What is the main idea or topic sentence of each body paragraph, and how does it relate back to the thesis statement?

- Where and how does each essay use evidence (quotes or paraphrase from the literature)?

- What are some of the literary devices or structures the essays analyze or discuss?

- How does each author structure their conclusion, and how does their conclusion differ from their introduction?

Example 1: Poetry

Victoria Morillo

Instructor Heather Ringo

3 August 2022

How Nguyen’s Structure Solidifies the Impact of Sexual Violence in “The Study”

Stripped of innocence, your body taken from you. No matter how much you try to block out the instance in which these two things occurred, memories surface and come back to haunt you. How does a person, a young boy , cope with an event that forever changes his life? Hieu Minh Nguyen deconstructs this very way in which an act of sexual violence affects a survivor. In his poem, “The Study,” the poem's speaker recounts the year in which his molestation took place, describing how his memory filters in and out. Throughout the poem, Nguyen writes in free verse, permitting a structural liberation to become the foundation for his message to shine through. While he moves the readers with this poignant narrative, Nguyen effectively conveys the resulting internal struggles of feeling alone and unseen.

The speaker recalls his experience with such painful memory through the use of specific punctuation choices. Just by looking at the poem, we see that the first period doesn’t appear until line 14. It finally comes after the speaker reveals to his readers the possible, central purpose for writing this poem: the speaker's molestation. In the first half, the poem makes use of commas, em dashes, and colons, which lends itself to the idea of the speaker stringing along all of these details to make sense of this time in his life. If reading the poem following the conventions of punctuation, a sense of urgency is present here, as well. This is exemplified by the lack of periods to finalize a thought; and instead, Nguyen uses other punctuation marks to connect them. Serving as another connector of thoughts, the two em dashes give emphasis to the role memory plays when the speaker discusses how “no one [had] a face” during that time (Nguyen 9-11). He speaks in this urgent manner until the 14th line, and when he finally gets it off his chest, the pace of the poem changes, as does the more frequent use of the period. This stream-of-consciousness-like section when juxtaposed with the latter half of the poem, causes readers to slow down and pay attention to the details. It also splits the poem in two: a section that talks of the fogginess of memory then transitions into one that remembers it all.

In tandem with the fluctuating nature of memory, the utilization of line breaks and word choice help reflect the damage the molestation has had. Within the first couple of lines of the poem, the poem demands the readers’ attention when the line breaks from “floating” to “dead” as the speaker describes his memory of Little Billy (Nguyen 1-4). This line break averts the readers’ expectation of the direction of the narrative and immediately shifts the tone of the poem. The break also speaks to the effect his trauma has ingrained in him and how “[f]or the longest time,” his only memory of that year revolves around an image of a boy’s death. In a way, the speaker sees himself in Little Billy; or perhaps, he’s representative of the tragic death of his boyhood, how the speaker felt so “dead” after enduring such a traumatic experience, even referring to himself as a “ghost” that he tries to evict from his conscience (Nguyen 24). The feeling that a part of him has died is solidified at the very end of the poem when the speaker describes himself as a nine-year-old boy who’s been “fossilized,” forever changed by this act (Nguyen 29). By choosing words associated with permanence and death, the speaker tries to recreate the atmosphere (for which he felt trapped in) in order for readers to understand the loneliness that came as a result of his trauma. With the assistance of line breaks, more attention is drawn to the speaker's words, intensifying their importance, and demanding to be felt by the readers.

Most importantly, the speaker expresses eloquently, and so heartbreakingly, about the effect sexual violence has on a person. Perhaps what seems to be the most frustrating are the people who fail to believe survivors of these types of crimes. This is evident when he describes “how angry” the tenants were when they filled the pool with cement (Nguyen 4). They seem to represent how people in the speaker's life were dismissive of his assault and who viewed his tragedy as a nuisance of some sorts. This sentiment is bookended when he says, “They say, give us details , so I give them my body. / They say, give us proof , so I give them my body,” (Nguyen 25-26). The repetition of these two lines reinforces the feeling many feel in these scenarios, as they’re often left to deal with trying to make people believe them, or to even see them.

It’s important to recognize how the structure of this poem gives the speaker space to express the pain he’s had to carry for so long. As a characteristic of free verse, the poem doesn’t follow any structured rhyme scheme or meter; which in turn, allows him to not have any constraints in telling his story the way he wants to. The speaker has the freedom to display his experience in a way that evades predictability and engenders authenticity of a story very personal to him. As readers, we abandon anticipating the next rhyme, and instead focus our attention to the other ways, like his punctuation or word choice, in which he effectively tells his story. The speaker recognizes that some part of him no longer belongs to himself, but by writing “The Study,” he shows other survivors that they’re not alone and encourages hope that eventually, they will be freed from the shackles of sexual violence.

Works Cited

Nguyen, Hieu Minh. “The Study” Poets.Org. Academy of American Poets, Coffee House Press, 2018, https://poets.org/poem/study-0 .

Example 2: Fiction

Todd Goodwin

Professor Stan Matyshak

Advanced Expository Writing

Sept. 17, 20—

Poe’s “Usher”: A Mirror of the Fall of the House of Humanity

Right from the outset of the grim story, “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Edgar Allan Poe enmeshes us in a dark, gloomy, hopeless world, alienating his characters and the reader from any sort of physical or psychological norm where such values as hope and happiness could possibly exist. He fatalistically tells the story of how a man (the narrator) comes from the outside world of hope, religion, and everyday society and tries to bring some kind of redeeming happiness to his boyhood friend, Roderick Usher, who not only has physically and psychologically wasted away but is entrapped in a dilapidated house of ever-looming terror with an emaciated and deranged twin sister. Roderick Usher embodies the wasting away of what once was vibrant and alive, and his house of “insufferable gloom” (273), which contains his morbid sister, seems to mirror or reflect this fear of death and annihilation that he most horribly endures. A close reading of the story reveals that Poe uses mirror images, or reflections, to contribute to the fatalistic theme of “Usher”: each reflection serves to intensify an already prevalent tone of hopelessness, darkness, and fatalism.

It could be argued that the house of Roderick Usher is a “house of mirrors,” whose unpleasant and grim reflections create a dark and hopeless setting. For example, the narrator first approaches “the melancholy house of Usher on a dark and soundless day,” and finds a building which causes him a “sense of insufferable gloom,” which “pervades his spirit and causes an iciness, a sinking, a sickening of the heart, an undiscerned dreariness of thought” (273). The narrator then optimistically states: “I reflected that a mere different arrangement of the scene, of the details of the picture, would be sufficient to modify, or perhaps annihilate its capacity for sorrowful impression” (274). But the narrator then sees the reflection of the house in the tarn and experiences a “shudder even more thrilling than before” (274). Thus the reader begins to realize that the narrator cannot change or stop the impending doom that will befall the house of Usher, and maybe humanity. The story cleverly plays with the word reflection : the narrator sees a physical reflection that leads him to a mental reflection about Usher’s surroundings.

The narrator’s disillusionment by such grim reflection continues in the story. For example, he describes Roderick Usher’s face as distinct with signs of old strength but lost vigor: the remains of what used to be. He describes the house as a once happy and vibrant place, which, like Roderick, lost its vitality. Also, the narrator describes Usher’s hair as growing wild on his rather obtrusive head, which directly mirrors the eerie moss and straw covering the outside of the house. The narrator continually longs to see these bleak reflections as a dream, for he states: “Shaking off from my spirit what must have been a dream, I scanned more narrowly the real aspect of the building” (276). He does not want to face the reality that Usher and his home are doomed to fall, regardless of what he does.

Although there are almost countless examples of these mirror images, two others stand out as important. First, Roderick and his sister, Madeline, are twins. The narrator aptly states just as he and Roderick are entombing Madeline that there is “a striking similitude between brother and sister” (288). Indeed, they are mirror images of each other. Madeline is fading away psychologically and physically, and Roderick is not too far behind! The reflection of “doom” that these two share helps intensify and symbolize the hopelessness of the entire situation; thus, they further develop the fatalistic theme. Second, in the climactic scene where Madeline has been mistakenly entombed alive, there is a pairing of images and sounds as the narrator tries to calm Roderick by reading him a romance story. Events in the story simultaneously unfold with events of the sister escaping her tomb. In the story, the hero breaks out of the coffin. Then, in the story, the dragon’s shriek as he is slain parallels Madeline’s shriek. Finally, the story tells of the clangor of a shield, matched by the sister’s clanging along a metal passageway. As the suspense reaches its climax, Roderick shrieks his last words to his “friend,” the narrator: “Madman! I tell you that she now stands without the door” (296).

Roderick, who slowly falls into insanity, ironically calls the narrator the “Madman.” We are left to reflect on what Poe means by this ironic twist. Poe’s bleak and dark imagery, and his use of mirror reflections, seem only to intensify the hopelessness of “Usher.” We can plausibly conclude that, indeed, the narrator is the “Madman,” for he comes from everyday society, which is a place where hope and faith exist. Poe would probably argue that such a place is opposite to the world of Usher because a world where death is inevitable could not possibly hold such positive values. Therefore, just as Roderick mirrors his sister, the reflection in the tarn mirrors the dilapidation of the house, and the story mirrors the final actions before the death of Usher. “The Fall of the House of Usher” reflects Poe’s view that humanity is hopelessly doomed.

Poe, Edgar Allan. “The Fall of the House of Usher.” 1839. Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library . 1995. Web. 1 July 2012. < http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/PoeFall.html >.

Example 3: Poetry

Amy Chisnell

Professor Laura Neary

Writing and Literature

April 17, 20—

Don’t Listen to the Egg!: A Close Reading of Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky”

“You seem very clever at explaining words, Sir,” said Alice. “Would you kindly tell me the meaning of the poem called ‘Jabberwocky’?”

“Let’s hear it,” said Humpty Dumpty. “I can explain all the poems that ever were invented—and a good many that haven’t been invented just yet.” (Carroll 164)