- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

George Washington

By: History.com Editors

Updated: February 7, 2024 | Original: October 29, 2009

George Washington (1732-99) was commander in chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War (1775-83) and served two terms as the first U.S. president, from 1789 to 1797. The son of a prosperous planter, Washington was raised in colonial Virginia. As a young man, he worked as a surveyor then fought in the French and Indian War (1754-63).

During the American Revolution, he led the colonial forces to victory over the British and became a national hero. In 1787, he was elected president of the convention that wrote the U.S. Constitution. Two years later, Washington became America’s first president. Realizing that the way he handled the job would impact how future presidents approached the position, he handed down a legacy of strength, integrity and national purpose. Less than three years after leaving office, he died at his Virginia plantation, Mount Vernon, at age 67.

George Washington's Early Years

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732 , at his family’s plantation on Pope’s Creek in Westmoreland County, in the British colony of Virginia , to Augustine Washington (1694-1743) and his second wife, Mary Ball Washington (1708-89). George, the eldest of Augustine and Mary Washington’s six children, spent much of his childhood at Ferry Farm, a plantation near Fredericksburg, Virginia. After Washington’s father died when he was 11, it’s likely he helped his mother manage the plantation.

Did you know? At the time of his death in 1799, George Washington owned some 300 enslaved people. However, before his passing, he had become opposed to slavery, and in his will, he ordered that his enslaved workers be freed after his wife's death.

Few details about Washington’s early education are known, although children of prosperous families like his typically were taught at home by private tutors or attended private schools. It’s believed he finished his formal schooling at around age 15.

As a teenager, Washington, who had shown an aptitude for mathematics, became a successful surveyor. His surveying expeditions into the Virginia wilderness earned him enough money to begin acquiring land of his own.

In 1751, Washington made his only trip outside of America, when he traveled to Barbados with his older half-brother Lawrence Washington (1718-52), who was suffering from tuberculosis and hoped the warm climate would help him recuperate. Shortly after their arrival, George contracted smallpox. He survived, although the illness left him with permanent facial scars. In 1752, Lawrence, who had been educated in England and served as Washington’s mentor, died. Washington eventually inherited Lawrence’s estate, Mount Vernon , on the Potomac River near Alexandria, Virginia.

An Officer and Gentleman Farmer

In December 1752, Washington, who had no previous military experience, was made a commander of the Virginia militia. He saw action in the French and Indian War and was eventually put in charge of all of Virginia’s militia forces. By 1759, Washington had resigned his commission, returned to Mount Vernon and was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses, where he served until 1774. In January 1759, he married Martha Dandridge Custis (1731-1802), a wealthy widow with two children. Washington became a devoted stepfather to her children; he and Martha Washington never had any offspring of their own.

In the ensuing years, Washington expanded Mount Vernon from 2,000 acres into an 8,000-acre property with five farms. He grew a variety of crops, including wheat and corn, bred mules and maintained fruit orchards and a successful fishery. He was deeply interested in farming and continually experimented with new crops and methods of land conservation.

George Washington During the American Revolution

Washington proved to be a better general than military strategist. His strength lay not in his genius on the battlefield but in his ability to keep the struggling colonial army together. His troops were poorly trained and lacked food, ammunition and other supplies (soldiers sometimes even went without shoes in winter). However, Washington was able to give them direction and motivation. His leadership during the winter of 1777-1778 at Valley Forge was a testament to his power to inspire his men to keep going.

By the late 1760s, Washington had experienced firsthand the effects of rising taxes imposed on American colonists by the British and came to believe that it was in the best interests of the colonists to declare independence from England. Washington served as a delegate to the First Continental Congress in 1774 in Philadelphia. By the time the Second Continental Congress convened a year later, the American Revolution had begun in earnest, and Washington was named commander in chief of the Continental Army.

Over the course of the grueling eight-year war, the colonial forces won few battles but consistently held their own against the British. In October 1781, with the aid of the French (who allied themselves with the colonists over their rivals the British), the Continental forces were able to capture British troops under General Charles Cornwallis (1738-1805) in the Battle of Yorktown . This action effectively ended the Revolutionary War and Washington was declared a national hero.

America’s First President

In 1783, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris between Great Britain and the U.S., Washington, believing he had done his duty, gave up his command of the army and returned to Mount Vernon, intent on resuming his life as a gentleman farmer and family man. However, in 1787, he was asked to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia and head the committee to draft the new constitution . His impressive leadership there convinced the delegates that he was by far the most qualified man to become the nation’s first president.

At first, Washington balked. He wanted to, at last, return to a quiet life at home and leave governing the new nation to others. But public opinion was so strong that eventually he gave in. The first presidential election was held on January 7, 1789, and Washington won handily. John Adams (1735-1826), who received the second-largest number of votes, became the nation’s first vice president. The 57-year-old Washington was inaugurated on April 30, 1789, in New York City. Because Washington, D.C. , America’s future capital city wasn’t yet built, he lived in New York and Philadelphia. While in office, he signed a bill establishing a future, permanent U.S. capital along the Potomac River—the city later named Washington, D.C., in his honor.

George Washington’s Accomplishments

The United States was a small nation when Washington took office, consisting of 11 states and approximately 4 million people, and there was no precedent for how the new president should conduct domestic or foreign business. Mindful that his actions would likely determine how future presidents were expected to govern, Washington worked hard to set an example of fairness, prudence and integrity. In foreign matters, he supported cordial relations with other countries but also favored a position of neutrality in foreign conflicts. Domestically, he nominated the first chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court , John Jay (1745-1829), signed a bill establishing the first national bank, the Bank of the United States , and set up his own presidential cabinet .

His two most prominent cabinet appointees were Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) and Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804), two men who disagreed strongly on the role of the federal government. Hamilton favored a strong central government and was part of the Federalist Party , while Jefferson favored stronger states’ rights as part of the Democratic-Republican Party, the forerunner to the Democratic Party . Washington believed that divergent views were critical for the health of the new government, but he was distressed at what he saw as an emerging partisanship.

George Washington’s presidency was marked by a series of firsts. He signed the first United States copyright law, protecting the copyrights of authors. He also signed the first Thanksgiving proclamation, making November 26 a national day of Thanksgiving for the end of the war for American independence and the successful ratification of the Constitution.

During Washington’s presidency, Congress passed the first federal revenue law, a tax on distilled spirits. In July 1794, farmers in Western Pennsylvania rebelled over the so-called “whiskey tax.” Washington called in over 12,000 militiamen to Pennsylvania to dissolve the Whiskey Rebellion in one of the first major tests of the authority of the national government.

Under Washington’s leadership, the states ratified the Bill of Rights , and five new states entered the union: North Carolina (1789), Rhode Island (1790), Vermont (1791), Kentucky (1792) and Tennessee (1796).

In his second term, Washington issued the proclamation of neutrality to avoid entering the 1793 war between Great Britain and France. But when French minister to the United States Edmond Charles Genet—known to history as “Citizen Genet”—toured the United States, he boldly flaunted the proclamation, attempting to set up American ports as French military bases and gain support for his cause in the Western United States. His meddling caused a stir between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, widening the rift between parties and making consensus-building more difficult.

In 1795, Washington signed the “Treaty of Amity Commerce and Navigation, between His Britannic Majesty; and The United States of America,” or Jay’s Treaty , so-named for John Jay , who had negotiated it with the government of King George III . It helped the U.S. avoid war with Great Britain, but also rankled certain members of Congress back home and was fiercely opposed by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison . Internationally, it caused a stir among the French, who believed it violated previous treaties between the United States and France.

Washington’s administration signed two other influential international treaties. Pinckney’s Treaty of 1795, also known as the Treaty of San Lorenzo, established friendly relations between the United States and Spain, firming up borders between the U.S. and Spanish territories in North America and opening up the Mississippi to American traders. The Treaty of Tripoli, signed the following year, gave American ships access to Mediterranean shipping lanes in exchange for a yearly tribute to the Pasha of Tripoli.

George Washington’s Retirement to Mount Vernon and Death

In 1796, after two terms as president and declining to serve a third term, Washington finally retired. In Washington’s farewell address , he urged the new nation to maintain the highest standards domestically and to keep involvement with foreign powers to a minimum. The address is still read each February in the U.S. Senate to commemorate Washington’s birthday.

Washington returned to Mount Vernon and devoted his attentions to making the plantation as productive as it had been before he became president. More than four decades of public service had aged him, but he was still a commanding figure. In December 1799, he caught a cold after inspecting his properties in the rain. The cold developed into a throat infection and Washington died on the night of December 14, 1799, at the age of 67. He was entombed at Mount Vernon, which in 1960 was designated a national historic landmark.

Washington left one of the most enduring legacies of any American in history. Known as the “Father of His Country,” his face appears on the U.S. dollar bill and quarter, and dozens of U.S. schools, towns and counties, as well as the state of Washington and the nation’s capital city, are named for him.

HISTORY Vault: Washington

Watch HISTORY's mini-series, 'Washington,' which brings to life the man whose name is known to all, but whose epic story is understood by few.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Help inform the discussion

George Washington: Impact and Legacy

From the moment Washington announced his retirement, the American people have remembered him as one of the greatest presidents in the nation’s history. The name of the Capitol City, the Washington Monument, his inclusion on Mount Rushmore, and his regular place near the top of presidential polls attests to the strength of his legacy. Indeed, generations of Americans have used Washington’s uniquely popular memory for their own political purposes. Most notably, after the Civil War, northerners and southerners valorized Washington and the founding era as a shared history they could both celebrate.

There is much to honor in Washington’s legacy. He was the only person who could have held the office in 1789. He was the most famous American, the only one with enough of a national platform to represent the entire country and overwhelmingly trusted by the populous. Americans knew they could trust him to wield immense power because he had already done so once during the Revolution and willingly gave it up.

The trust and confidence Washington inspired made possible the creation of the presidency and helped establish the executive branch. Once in office, he cultivated respect for the presidency, regularly exhibited restraint in the face of political provocations, and attempted to serve as a president for all citizens (which admittedly meant white men). He was always mindful of the principles of republican virtue, namely self-sacrifice, decorum, self-improvement, and leadership. Our modern notions that the president should be held to higher standards and the office carries a certain level of respect and prestige began with Washington’s careful creation of the position.

Washington also left an inveterate imprint on the political process, especially through his formation of the cabinet. Every president since Washington has worked with a cabinet, and each president crafts their own decision-making process. They select their closest advisors and determine how they will obtain advice from those individuals. Presidents might choose to consult friends, family members, former colleagues, department secretaries, or congressmen, and the American people and Congress have very little oversight over those relationships. Some presidents, like Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt, flourish with the flexibility; others, including James Madison and John F. Kennedy, find their administrations undermined by domineering advisors or cabinets. That legacy is a direct result of Washington’s cabinet.

Washington’s decision to step away from power, again, solidified his legacy and had a powerful impact on the future of the presidency. All his successors, until Franklin D. Roosevelt, willingly followed his example of retiring after two terms, and the 22 nd Amendment made sure that no future president can serve more than two terms. More importantly, Washington recognized the structural importance of leaving office willingly. He knew that Americans needed to learn how to elect, transition, and inaugurate a new president. That process was fraught with potential missteps, and Washington concluded that it would go more smoothly if it was planned, rather than haphazardly done after an unexpected death. Washington understood how much of the political process is based on norm and custom, and that those had to start with his example.

For all these achievements, and there are many, recently Washington’s legacy lost a bit of its sparkle as Americans grapple with his personal failures. Of the many political choices in his long career, Washington’s decisions in retirement were perhaps his worst. In 1798, Congress created the Provisional Army as the Quasi-War with France accelerated. President John Adams asked Washington to come out of retirement one more time to lead the army.

Washington reluctantly agreed but extracted two promises. First, he wanted to stay at Mount Vernon until a French invasion. Second, Washington insisted on naming his subordinate officers who would manage the army in his absence. When Adams reluctantly caved, Washington named Alexander Hamilton as his deputy. Hamilton and Adams hated each other, and Washington knew it. By forcing these concessions, Washington undermined the presidency and civilian authority over the army. As Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, Washington had studiously upheld Congress’s authority. His failure to make the same choice in his retirement is often overlooked but should be viewed with considerable criticism.

However, Washington’s ownership of enslaved humans is by far the most challenging part of his legacy. To be sure, Washington’s ideas about slavery and the potential for Black emancipation evolved over his lifetime. He did free the enslaved people he owned in his will, which is much more than most people in his generation. This commitment required decades-long planning to leave his estate unencumbered by debt which could only be reduced through the sale of enslaved individuals. And he did so in the face of resistance from other Virginians, including his wife. When the terms of Washington’s will were published, the emancipation of his enslaved community sent ripples through the country. He had issued a forceful statement about the morality of slavery from the grave.

Yet, Washington clearly benefitted from exploiting enslaved people. And by the end of his life, he knew the institution was wrong and could have done more to end it. Washington pursued enslaved people who escaped when he could have left them to their freedom. He could have freed the enslaved people he owned during his lifetime but elected to enjoy the fruits of their labor until his last days. He also chose not to deprive Martha of that care either, which is why the enslaved people he owned were not to be freed until her death.

On a public scale, Washington could have made the terms of his will public before his death or spoken against slavery while he was alive. His words would have had an enormous impact—which is perhaps why he remained silent. Washington worried that if he forced the issue, southern states would secede from the Union. There will be no way to know if he was right or if these concerns were correct. But much of Washington’s lifestyle and personal wealth were dependent on slavery, and that must be considered a part of his legacy.

Lindsay M. Chervinsky

Senior Fellow The Center for Presidential History Southern Methodist University

More Resources

George washington presidency page, george washington essays, life in brief, life before the presidency, campaigns and elections, domestic affairs, foreign affairs, life after the presidency, family life, impact and legacy (current essay).

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

George washington: man, myth, monument.

George Washington

Horatio Greenough

Charles Willson Peale

Hiram Powers

George Washington and William Lee (George Washington)

John Trumbull

James Peale

Charles Peale Polk

Giuseppe Ceracchi

Washington Reviewing the Western Army at Fort Cumberland, Maryland

Attributed to Frederick Kemmelmeyer

Gilbert Stuart

The American Star (George Washington)

Frederick Kemmelmeyer

[Girl with Portrait of George Washington]

Southworth and Hawes

Washington Crossing the Delaware

Emanuel Leutze

Rembrandt Peale

Apotheosis of George Washington

Heinrich Weishaupt

George Washington Quilt

Century Vase

Designed by Karl L. H. Müller

Karl L. H. Müller

Carrie Rebora Barratt The American Wing, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The multiplicity of depictions of George Washington (1732–1799) testifies to his persistence in American life and myth. During his lifetime, his very image, whether presented as a Revolutionary War hero or as chief executive of the United States, exemplified the ideal leader: authoritative, victorious, strong, moral, and compassionate. Over the course of the nineteenth century, American and European popular culture elaborated on Washington’s iconic persona and adapted it to patriotic and sentimental purposes.

Two major bequests to the Metropolitan ensured that the collection would be rich in images of Washington in various media. In 1883, William Henry Huntington bequeathed more than 2,000 American portraits , primarily of Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and the marquis de Lafayette. For much of his life, Huntington was a Paris correspondent for the New York Tribune . An inveterate seeker of Americana at shops and flea markets, he purchased an array of medals, porcelains, textiles, and other works of art while abroad. The second gift to the Museum came in 1924 from Charles Allen Munn, editor and publisher of Scientific American for forty-three years. By the time of his death, Munn had assembled a notable collection of portraits of Washington. Among the highlights of his bequest are portraits by the American artists for whom Washington actually sat, including Gilbert Stuart ( 07.160 ), Charles Willson Peale ( 97.33 ), and John Trumbull ( 24.109.88 ).

General George Washington A gentleman farmer from Virginia, Washington began his military career at the age of twenty, when he was commissioned as a major in the state’s militia; within three years, he had risen through the ranks to be appointed commander in chief of those troops. Twenty years later, in 1775, he was named commander in chief of the Continental Forces of North America, and he led his army to victory over Great Britain. He was admired for his ability to inspire and lead a disparate group of men into battle. After his retirement from service at the war’s end, he was venerated by his contemporaries and by subsequent generations of military men. Washington’s image in uniform, portrayed by so many artists in a variety of media, became a symbol not only of military prowess but also of national unity and American liberty.

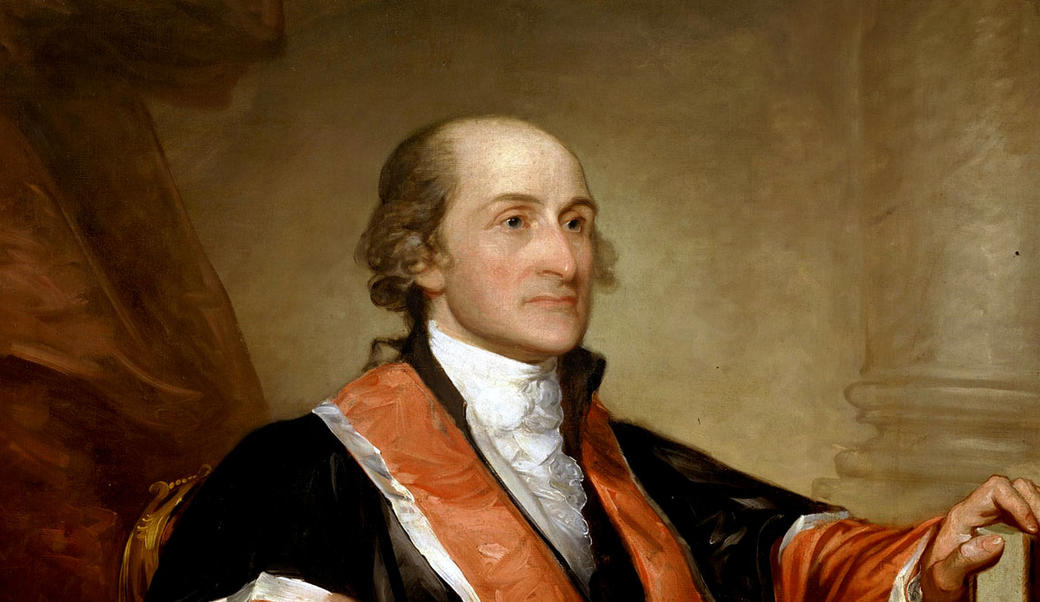

President George Washington During Washington’s two terms as president (1789–97), his image was modeled almost exclusively on portraits by Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828), the premier painter of the new nation . Stuart executed three different portraits from life sittings with the president, but it was the so-called Athenaeum portrait that became the most popular. Stuart himself painted at least seventy replicas of it, and, because it was exhibited in the Boston Athenaeum after Stuart’s death, many other artists were able to use it as the basis for their work. Stuart’s portrayal of Washington became so pervasive that, as the artist’s biographer, the critic William Dunlap, put it in 1832, “if George Washington should appear on earth, . . he would be treated as an impostor, when compared to Stuart’s likeness of him, unless he produced his credentials.”

The Myth of George Washington The extraordinary outpouring of emotion after Washington’s death on December 14, 1799, reverberated worldwide, as mourners grieved not merely for the man himself but for the hero he had become and, still more warmly, for the father of the country. Washington’s role in American life had been of long duration and great depth. His image symbolized the power and legitimacy of the newly independent nation, which was still very much in the formative stages during the nineteenth century. His imposing figure as president embodied ideals of honesty, virtue, and patriotism ( 62.256.7 ). Nineteenth-century images of Washington ranged from his godlike apotheosis ( 52.585.66 ) to scenes of his personal life . His home, Mount Vernon , on the Potomac River in northern Virginia, became a shrine to his mythic celebrity. In 1853, the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association was founded, mostly through the efforts of women, in order to save the historic property and honor Washington’s legacy.

George Washington and the American Centennials In 1876, the United States observed the centennial of its founding, and 1889 marked the 100th anniversary of George Washington’s first inauguration as president. Nearing the turn of the twentieth century , at a time when Americans clamored for reassurance that their leaders were trustworthy and the country secure, both celebrations featured commemorative images of Washington—the epitome of an honorable head of state—in his varied roles as public servant and private individual.

In Philadelphia, the Centennial Exposition of 1876 featured new developments in art, design, and technology from an international group of exhibitors and attracted more than 8 million visitors. Washington’s portrait on plates ( 69.194.1 ), handkerchiefs ( 1985.347 ), glassware, and prints provided a nostalgic foil to burgeoning technological developments and made the country’s progress seem a natural continuum, from the American Revolution to the Industrial Revolution.

In 1889, grand celebrations were mounted in honor of the centennial of Washington’s inauguration. New York City officials erected a great arch at the foot of Fifth Avenue (in Washington Square), held a parade, launched a naval flotilla, and reenacted the swearing-in ceremony that had taken place in New York when it was briefly the nation’s capital. The Metropolitan Opera House hosted a gala ball and mounted an exhibition of Washington’s personal belongings and related memorabilia—pieces of history that established an authentic link to the country’s past and gave promise for the future.

Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “George Washington: Man, Myth, Monument.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/wash/hd_wash.htm (May 2009)

Further Reading

Barratt, Carrie Rebora, and Ellen G. Miles. Gilbert Stuart . Exhibition catalogue. New York: Yale University Press, 2004. See on MetPublications

Ellis, Joseph J. His Excellency: George Washington . New York: Knopf, 2004.

Fischer, David Hackett. Washington's Crossing . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Schwartz, Barry. George Washington: The Making of an American Symbol . New York: Free Press, 1987.

Additional Essays by Carrie Rebora Barratt

- Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “ Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828) .” (October 2003)

- Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “ American Portrait Miniatures of the Nineteenth Century .” (October 2004)

- Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “ John Singleton Copley (1738–1815) .” (October 2003)

- Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “ American Portrait Miniatures of the Eighteenth Century .” (October 2003)

- Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “ American Scenes of Everyday Life, 1840–1910 .” (September 2009)

- Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “ Nineteenth-Century American Folk Art .” (October 2004)

- Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “ Students of Benjamin West (1738–1820) .” (October 2004)

- Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “ Thomas Sully (1783–1872) and Queen Victoria .” (October 2004)

Related Essays

- American Portrait Miniatures of the Eighteenth Century

- Art and Identity in the British North American Colonies, 1700–1776

- Art and Society of the New Republic, 1776–1800

- Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828)

- Hiram Powers (1805–1873)

- American Federal-Era Period Rooms

- American Furniture, 1730–1790: Queen Anne and Chippendale Styles

- American Georgian Interiors (Mid-Eighteenth-Century Period Rooms)

- American Neoclassical Sculptors Abroad

- American Portrait Miniatures of the Nineteenth Century

- American Revival Styles, 1840–76

- American Scenes of Everyday Life, 1840–1910

- American Silver Vessels for Wine, Beer, and Punch

- Architecture, Furniture, and Silver from Colonial Dutch America

- Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907)

- Coffee, Tea, and Chocolate in Early Colonial America

- Duncan Phyfe (1770–1854) and Charles-Honoré Lannuier (1779–1819)

- English Ornament Prints and Furniture Books in Eighteenth-Century America

- Frederick William MacMonnies (1863–1937)

- Henry Kirke Brown (1814–1886), John Quincy Adams Ward (1830–1910), and Realism in American Sculpture

- John Singleton Copley (1738–1815)

- John Townsend (1733–1809)

- Paul Revere, Jr. (1734–1818)

- Students of Benjamin West (1738–1820)

List of Rulers

- Presidents of the United States of America

- The United States and Canada, 1800–1900 A.D.

- The United States, 1600–1800 A.D.

- 18th Century A.D.

- 19th Century A.D.

- American Art

- American Decorative Arts

- Architectural Element

- Colonial American Art

- Nationalism

- North America

- United States

Artist or Maker

- Ceracchi, Giuseppe

- Greenough, Horatio

- Hawes, Josiah Johnson

- Kemmelmeyer, Frederick

- Leutze, Emanuel Gottlieb

- Moore, Samuel

- Müller, Karl L.H.

- Peale, Charles Willson

- Peale, James

- Peale, Rembrandt

- Polk, Charles Peale

- Powers, Hiram

- Southworth, Albert Sands

- Stuart, Gilbert

- Trumbull, John

- Union Porcelain Works

- Weishaupt, H.

Online Features

- Connections: “Smile” by Kathy Galitz

- Connections: “The Ideal Man” by Nadine Orenstein

Founders Online --> [ Back to normal view ]

Quick links.

- About Founders Online

- Major Funders

- Search Help

- How to Use This Site

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Teaching Resources

About the Papers of George Washington

The Papers of George Washington , launched at the University of Virginia in 1968, is a scholarly documentary editing project that edits, publishes, and publicizes a comprehensive edition of George Washington's public and private papers. Today there are copies of over 135,000 documents in the project’s document room—one of the richest collections of American historical manuscripts extant. There is almost no facet of research on life and enterprise in the late colonial and early national periods that will not be enhanced by material from these documents. The publication of Washington’s papers will make this source material available not only to scholars, but to all Americans interested in the founding of their nation.

This edition, available in both digital and print formats, is divided into six parts, five of which have been completed: the Diaries (1748–1799; six volumes); the Colonial Series (1744–1775; ten volumes); the Confederation Series (1784–1788; six volumes); the Presidential Series (1788–1797; twenty-one volumes); and the Retirement Series (1797–1799; four volumes). The project also has produced three individual books: The Journal of the Proceedings of the President, 1793–1797 (1981), a one-volume abridgment of the Diaries (1999), and Washington’s Barbados Diary, 1751–1752 (2018). Project staff now focuses on completing by 2028 the Revolutionary War Series (1775–1783; twenty-seven volumes of a projected forty-three, as of September 2020). In 2008, the project broadened its scope to include other significant editions, such as the George Washington’s Financial Papers , the Martha Washington Papers, and Washington Family Papers projects.

The project’s work is generously supported by grants from the Florence Gould Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, the Packard Humanities Institute, the University of Virginia, and gifts from private foundations and individuals. The project’s website is located at https://washingtonpapers.org .

See a complete list of Washington Papers volumes included in Founders Online, with links to the documents.

The letterpress edition of The Papers of George Washington is available from The University of Virginia Press .

Copyright © by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia. All rights reserved.

Open 365 days a year, Mount Vernon is located just 15 miles south of Washington DC.

From the mansion to lush gardens and grounds, intriguing museum galleries, immersive programs, and the distillery and gristmill. Spend the day with us!

Discover what made Washington "first in war, first in peace and first in the hearts of his countrymen".

The Mount Vernon Ladies Association has been maintaining the Mount Vernon Estate since they acquired it from the Washington family in 1858.

Need primary and secondary sources, videos, or interactives? Explore our Education Pages!

The Washington Library is open to all researchers and scholars, by appointment only.

George Washington's Papers

- During Washington's Life

- After Washington's Death

- Publishing the Papers

- Bibliography

George Washington both produced and received a large number of letters, documents, accounts, and notes during his lifetime. Washington was aware of his special place in the development of the United States and as a famed and beloved military leader and statesman, and was cognizant that his papers would be of interest to future readers. The papers that survive today are available because of the care that Washington took during his lifetime, despite the sometimes careless and destructive handling that they faced after his death.

During Washington's Life Washington was meticulous with the organization and care of his papers. At different points in his life, Washington created letter books (bound volumes with copies of his outgoing and incoming letters), used a letterpress (a device that made direct copies of writing by lifting some of the ink from the page), and even edited his copies of some of his early letters, smoothing grammar and word choice. In addition, throughout his life he hired secretaries, aides-de-camp, clerks, and copyists to assist.

As early as 1775 during the American Revolution, Washington held the safety of his papers at Mount Vernon second only to the safety of his wife, Martha Washington . George Washington instructed his cousin Lund Washington to provide "for her in Alexandria, or some other place of safety for her and my Papers." 1 As the Revolutionary War progressed and the volume of papers he was creating grew, Washington was concerned for their care, once sending them to Congress in Philadelphia for safekeeping. In 1781 he asked Congress and was allowed to hire a team of clerks to transcribe and organize his letters. Upon his return to Mount Vernon after the war, he hoped "to overhaul & adjust all my papers." 2

As President, Washington and his staff produced many papers. When his second term was finished, Washington had his secretaries remove the papers his successor would need and had them pack the rest to ship to Mount Vernon. During his retirement, Washington wrote that he had devoted his infrequent leisure time "to the arrangement, and overhaul of my voluminous Public Papers—Civil & Military—that, they may go into secure deposits." 3

Washington also planned to erect a building at Mount Vernon especially to store his papers. The building was not constructed by the time of his death. Even on the last day of his life, Washington worried about his papers. His friend and longtime secretary Tobias Lear recorded that, hours before his death, Washington told him, "I find I am going, my breath cannot continue long. . . do you arrange & record all my late Military letters & papers—arrange my accounts & settle my books." 4

After Washington's Death In his will, Washington bequeathed all his civil and military papers, as well as his " private Papers as are worth preserving," to his nephew Bushrod Washington , a U.S. Supreme Court justice. 5 In the months following George Washington’s death, Tobias Lear organized the papers in the former president's office. It may have been at that time that Martha Washington removed and burned her correspondence with her husband. Soon after Bushrod Washington allowed Chief Justice John Marshall to take many of the papers to Richmond while Marshall wrote a biography of the first president. Marshall, however, did not always take sufficient care of the papers. As Justice Washington later noted, “the papers sent to the Chief Justice . . . have been very extensively mutilated by rats and otherwise injured by damp." 6

In addition to Marshall’s poor stewardship, Bushrod Washington allowed several people—including the Marquis de Lafayette and James Madison —to remove their correspondence with the late president. Justice Washington also passed out autographs and other favors from the papers as souvenirs to favor seekers. He allowed William Sprague, his nephews' tutor, to remove more than 1,500 letters on the stipulation that he leave copies in their place.

In January 1827, Bushrod Washington gave editor Jared Sparks permission to publish some of Washington's papers. During his work, Sparks moved many of the papers to Boston and he visited repositories in both the United States and Europe to search for letters and documents not represented in Washington's own papers. Unfortunately he was also free with giving favors of Washington’s handwriting.

When Bushrod Washington died in 1829, he left George Washington's papers to his nephew George Corbin Washington, a Maryland congressman. George Corbin Washington soon moved the papers that remained at Mount Vernon to his office in Georgetown. Governmental officers had often consulted Washington's papers, and in 1833 George Corbin Washington agreed to sell the papers to the State Department, excepting ones he considered to be private. In 1849 he sold the private papers as well. The Washington papers remained at the State Department until 1904, when they were turned over to the Library of Congress. Copies of Washington papers from other repositories and some originals have been added to the collection over the years since the library took possession. In 1964 the Library of Congress released a reproduction of the papers on microfilm, and in 1998 it posted digital images of the papers taken from the microfilm on its Web site.

Publishing the Papers Jared Sparks' The Writings of George Washington was published in eleven volumes between 1833 and 1837. Sparks edited Washington’s words heavily, changing spelling, grammar, phrasing, and at times entire sentences. From 1889 to 1893, historian Worthington Chauncey Ford published a fourteen-volume set of The Writings of George Washington . Later, John C. Fitzpatrick prepared thirty-nine volumes of The Writings of George Washington From the Original Manuscript Sources (1931–1944) as a part of the United States George Washington Bicentennial Commission.

However, no comprehensive or fully annotated version of Washington's papers was attempted until the creation of the Papers of George Washington project in 1968. Sponsored by the University of Virginia and the Mount Vernon Ladies Association and supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, the editors and staff procured more than 135,000 copies of Washington documents from repositories worldwide. In their search they included not only letters written by George Washington, but also letters to him, documents, diaries, and financial papers. About half of those documents are from the Library of Congress' Washington Papers collection.

Early in the project the staff divided the work into a set of diaries and five chronological series of correspondence: Colonial, Revolutionary War, Confederation, Presidential, and Retirement, which have been published simultaneously (63 volumes to date). The two largest series, Revolutionary War and Presidential, are still in production, with an estimated twenty-four more volumes to go. The George Washington Papers Digital Edition, created by the Papers staff and University of Virginia's digital imprint, Rotunda, was launched in 2006.

Maria Kimberly Research Assistant, The Papers of George Washington

Notes: 1. "George Washington to Lund Washington, 20 August 1775," The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series , 1:335.

2. " George Washington to George William Fairfax, 27 February 1785 ," The Papers of George Washington, Confederation Series , 2:386.

3. " George Washington to James McHenry, 29 July 1798 ," The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series , 2:473.

4. Tobias Lear's Account of Washington's Death, The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series , 4:545.

5. George Washington's Will , The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series , 4:485.

6. "Bushrod Washington to James Madison, 14 September 1819," The Papers of James Madison, Retirement Series , 1:513.

Bibliography: W. W. Abbot, " An Uncommon Awareness of Self: The Papers of George Washington "

The George Washington Papers: Provenance and Publication History .

Quick Links

9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

U.S. Presidents

George washington.

First president of the United States

The son of a landowner and planter, George Washington was born on February 22, 1732, in the British-ruled colony of Virginia . His father died when he was 11, and his older brother, Lawrence, helped raise him. Washington was educated in basic subjects including reading, writing, and mathematics, but he didn’t attend college. Not much else is known about his childhood. Stories about his virtues—such as his confession of chopping down his father’s cherry tree—were actually invented by an admiring writer soon after Washington’s death.

During his 20s, he fought as a soldier in the French and Indian War, Great Britain’s fight with France over the Ohio River Valley territory. After the war, Washington returned to Virginia to work as a farmer.

Virginians elected Washington to their colonial legislature, or government, when he was 26. Soon after, he married Martha Dandridge Custis, a wealthy widow with two young children. They settled at Mount Vernon, a family home Washington had inherited.

REVOLUTIONARY WAR HERO

As a government official, Washington spoke out against unfair laws, such as high taxes, during Great Britain’s rule. In 1774 and 1775, he was one of Virginia’s representatives at the First and Second Continental Congresses, a group of representatives from the 13 colonies that would eventually become the United States. The Second Congress helped future third president, Thomas Jefferson , write the Declaration of Independence in July 1776, proclaiming that the 13 colonies were now independent states, no longer under British rule. An army was formed to oppose the British, and Washington was selected to lead it.

For five years, Washington served as the head of the army as the Revolutionary War against the British raged. The British finally surrendered in 1781 at Yorktown, Virginia. Washington was now a hero, seen as an important person who helped the colonies finally gain independence from Great Britain . After the war, Washington retired from the army and returned to private life.

PATH TO PRESIDENCY

After the end of the war, the former colonies operated under the Articles of Confederation, a document that placed most power with the states. For example, each state printed its own money. There was no national leader. The individual states were not supporting each other as one country, and the new nation seemed to be in trouble.

In 1787 state representatives gathered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania , at the Constitutional Convention to fix these problems. There, the delegates wrote the Constitution of the United States. This document created a strong federal government: two chambers of legislators (also called lawmakers), a federal court system, and a president. The Constitution still serves as the foundation for the United States government today.

Based on the Constitution’s directions, states chose representatives to elect a president. Washington won the vote, making him the first-ever president of the United States. John Adams received the second most votes and became vice president.

SETTING TRADITIONS

As the nation’s first president, Washington set the example for other presidents. He worked out how the nation would negotiate treaties with other countries. He decided how the president would select and get advice from cabinet members. He also established the practice of giving a regular State of the Union speech, a yearly update on how the country is doing. He appointed federal judges and established basic government services such as banks. As president, he also worked hard to keep the new country out of wars with Native Americans and European nations.

During Washington’s time as president, New York City was the nation’s temporary capital; then Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Although Washington helped plan a permanent national capital, his presidency ended before the federal government moved to the city later named in his honor: Washington, D.C.

LASTING LEGACY

After serving two back-to-back terms as president, Washington retired to Mount Vernon in 1797. He died two years later on December 14, 1799. Washington, who kept one of the largest populations of enslaved people in the country, arranged in his will for them to be freed by the time of his wife’s death. After his death, he was praised as being "first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen."

• Washington is the only president to have a state named for him. • The first president was so worried about being buried alive, he insisted mourners wait at least three days before burying him. Just in case. • The first president is the only president not to live in the White House.

From the Nat Geo Kids books Our Country's Presidents by Ann Bausum and Weird But True Know-It-All: U.S. Presidents by Brianna Dumont, revised for digital by Avery Hurt

more to explore

(ad) "weird but true know-it-all: u.s. presidents", independence day, (ad) "our country's presidents".

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your California Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell My Info

- National Geographic

- National Geographic Education

- Shop Nat Geo

- Customer Service

- Manage Your Subscription

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Home — Essay Samples — Government & Politics — Presidents of the United States — George Washington

Essays on George Washington

What makes a good george washington essay topics.

When it comes to writing an essay about George Washington, choosing a good topic is essential for capturing the reader's interest and conveying a unique perspective on the subject matter. To brainstorm and choose an essay topic, it's important to consider various aspects such as relevance, significance, and originality. A good George Washington essay topic should be thought-provoking, well-researched, and engaging for the reader. When selecting a topic, think about what aspects of George Washington's life, leadership, and legacy you find most compelling. Consider the historical context, his impact on the nation, and his role as a founding father. A good essay topic should also allow for in-depth analysis and critical thinking, providing ample opportunity for exploration and discussion.

Best George Washington Essay Topics

- George Washington's leadership during the Revolutionary War

- The significance of George Washington's Farewell Address

- George Washington's impact on the formation of the U.S. Constitution

- The role of George Washington as the first President of the United States

- George Washington's stance on slavery and its implications

- The relationship between George Washington and other founding fathers

- George Washington's legacy and lasting influence on American politics

- The portrayal of George Washington in popular culture and media

- George Washington's contributions to the development of the American identity

- The myth vs. reality of George Washington's character and leadership

- George Washington's military strategy and tactics during the Revolutionary War

- The personal life and family of George Washington

- George Washington's vision for the future of the United States

- The economic policies of George Washington's presidency

- The foreign policy challenges faced by George Washington

- George Washington's relationship with Native American tribes

- The impact of George Washington's presidency on the development of political parties

- George Washington's role in shaping the executive branch of the U.S. government

- The significance of Mount Vernon in the life of George Washington

- George Washington's influence on the formation of the American military

George Washington essay topics Prompts

- Imagine you are George Washington. Write a letter to a fellow founding father discussing the challenges and opportunities of leading a young nation.

- Create a dialogue between George Washington and a contemporary political figure, discussing the principles of leadership and governance.

- Design a museum exhibition dedicated to George Washington's life and legacy. What artifacts, documents, and interactive elements would you include to tell his story?

- Write an alternative history essay exploring what might have happened if George Washington had not become the first President of the United States.

- Interview a historian or expert on George Washington and write an article that conveys their insights and knowledge about his impact on American history.

George Washington Character Traits

Summary of george washingtons farewell address, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

The Life, Presidency and Accomploshments of George Washington

George washington – the founding father, the importance of george washington for america, the contributions of george washington to the american victory over the british empire, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Analysis of George Washington's Farewell Address

Farewell address - the final george washington's request to american society, george washington's farewell address and last advices, washington’s farewell address analysis, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

Foundihg Fathers of Freedom

American government: madison's and washington's performance, what influenced the patriots' win in the revolutionary war, relevant topics.

- Abraham Lincoln

- Andrew Jackson

- James Madison

- John F. Kennedy

- Thomas Jefferson

- Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Barack Obama

- Electoral College

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

George Washington: Founding Father, Essay Example

Pages: 7

Words: 1996

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Man of the People: George Washington and the Politics of Virtue

For most of us, America’s Founding Fathers are instantly recognizable icons. Intrepid and cerebral aristocrats, they gaze serenely from venerable portraits or Olympian monuments to their historic achievements. Perhaps no figure in American history is more venerable, more iconic, than George Washington.

In Reintroducing George Washington: Founding Father, Richard Brookhisersets out to show that the man who “helped bring about a transformation of the American government, from the Articles of Confederation to the Constitution” (p. 11),was a first-rate statesman, a man whose personal, human traits were as valuable to the delicate work of the country’s Constitutional Convention as was the personal stature he lent to the new nation as its first president. A lesser man, one content with the stature that came with great military accomplishments, may have been content to merely preside, to allow political bickering and hair-splitting to threaten what faith and force of will had forged during six years of hardship and bloodshed.

Not so Washington, who drew on a reserve of political subtlety learned as a representative in Virginia’s House of Burgesses to help guide the greatdebate that followed independence. George Washington was that rare phenomenon, a man whom character, opportunity and crisis appoint to fill a role absolutely no one else can.That a group of such mercurial and argumentative statesmen and political theorists would have unanimously elected him (or anyone) to lead Congress and the new country through the contentious proceedings that followed the war tells us that menwho were, by nature, inclined to argue over the minutest detail, were in completeconcord when it came to George Washington.

They knew that Washingtonwas suited to lead, to hold together the fragile American union. What likely escaped the notice of most delegates was that Washington’s demeanor concealed a keen grasp of human nature and a timely knack for theaterand manipulation. Washington the icon embodied America’s Republican values and stoic self-image. Washington the man was scrupulously concerned with the niceties of the drawing room and dance floor. Brookhiser’s superb quote says it best –“(Washington) was influenced by Roman notions of nobility, but he was even more deeply influenced by a list of table manners and rules for conversation compiled by Jesuits” (p. 12).

Much of Washington’s early life is unknown to us. That he came from the Virginia planter gentry is evident from his status as wealthy land owner(and slave owner) and from his 16 years of service in the House of Burgesses prior to the Revolution. The skills he learned in Virginia’s lower house helped prepare him for the role he would play in Congress, much as his military service in the French and Indian War provided valuable “on-the-job” training in the cagey, fox-and-hounds military strategy he would eventually employ against the British army.

Politician, motivator and manipulator

These experiences,both military and political, left him with an understanding of the need to motivate others to act in the general (and sometimes in Washington’s) interest. Any experienced politician would agree that the ability to manipulate is indispensable. However, acknowledging that Washington resorted to such tactics flies in the face of popular beliefs in his steadfastness and imperviousness to external pressures. Yet Brookhiser points out that

Washington, who was “constantly requesting, cajoling and complaining” to Congress during the direst days of the Revolutionary War, nevertheless had a fine sense of the line between “entreaty and compulsion”(p.39). His frequent communications with Congress during the war are obedient and cordial, but also insistent andmorally leveraging. He’s simply reminding them of what they know to be right.

Washington’s response to the army’s crisis of 1783may have been his personal tour de force. Lack of pay had pushed the army to the brink of revolt. Sensing the discontent among the officers as well as the rank and file, Washington called an official meeting. Here we see Washington’s understanding of human nature and his ability to manipulate strong feelings to serve his needs. Or, as Brookhiser puts it, “he then proceeded to summon the passions for his own ends (p. 43).”

As he addressed the officers, the commander-in-chief told them he wanted to read a letter that demonstrated Congress was not their enemy. As he fumbled with the letter, he reached for his reading glasses and said, “Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for I have not only grown gray but almost blind in the service of my country” (p. 44). For the men who had come to revere Washington for sharing in their privations and misery, for never having taken leave during seven years of war, it was truly powerful theater. Regardless of Washington’s true motive or means, it worked. There wasn’t a dry eye in the house.

The incipient mutiny was over, the danger was past. One is hard-pressed to find an example from antiquity of a charismatic leader relying solely on pathos to put down unrest among the troops. Caesar may have had the love and respect of his men but for all his professions of admiration for the legions who fought his battles, Caesar’swillingness to show clemency and generosity cloaked an omnipresent threat of punishment.

It is small wonder that Washington’s service in the Virginia assembly and seven years spent constantly motivating unpaid and underfed troops had made him a master of understated persuasion. When he was elected to head the new Congress, he came to the job with a clear sense of how to do business on the legislative/political stage.

Stature, subtlety and temper

Experience had taught Washington that one word was better than two when it came to politics. “Speak seldom,” he told a nephew who was new to legislative politics. “Never exceed a decent warmth, and submit your sentiments with diffidence” (p. 65-66). After observing Washington and Benjamin Franklin in action, Jefferson noted that both had become masters at accomplishing more by saying less.

“I never heard either of them speak ten minutes at a time, nor to any but the main point” Jefferson said. “They laid their shoulders to the great points, knowing that the little ones would follow of themselves” (p. 66).

Washington evidently took pride in the ability to keep people guessing and saw himself as a man whose expressions didn’t betray his thoughts and feelings.Near the end of his presidency, the wife of the British ambassador told Washington she could see in his face how much he welcomed the idea of retirement. “You are wrong,” Washington replied. “My countenance never yet betrayed my feelings” (p.5).

Yet, Washington spent a lifetime trying to control a spirited temper. As a teenager, his relative and employer, Thomas, Lord Fairfax, told Washington’s mother that her son had a problem controlling his anger. In middle age his fiery naturecould still flare, as subordinate officers Alexander Hamilton and Charles Leecould (and did) attest during the Revolution. In fact, Hamilton wrote that Washington was “remarkable (neither) for delicacy nor for good temper” (p. 116-117).

The pursuit of virtue

Temper, manipulation and concealed emotions are characteristics that bring Washington out of the pantheon and place him among us, ascribing to him traits with which we all can identify. As Brookhiser explains in his chapter on Washington’s morals, his unfailing adherence to virtues with which all of the founders strongly identified are another matter. This is ground in which many of the legends about Washington are rooted, such as the felled cherry tree, about which young George refused to lie.

This is one of the most interesting and revealing parts of Brookhiser’s book. In it, he explains how strongly the founders identified with the Romans, whom they viewed as morally virtuous and politically successful (p. 122). The Greeks, in spite of having invented Democracy, were seen as having failed to sustain a Republic, an accomplishment the Romans maintained for centuries.

The Society of the Cincinnati was founded by Revolutionary War officers in 1783 in honor of Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, a Roman farmer who accepted the position of consul and was endowed with dictatorial authority in a time of crisis. Cincinnatus voluntarily surrendered his powers to the Senate when the crisis was averted. Even casual students and admirers of Washington cannot fail to note some familiar in this example of selflessness and its implications for American history. Less than 20 years after the Society of the Cincinnati was formed, Washington would emulate Cincinnatus’s sacrifice and himself voluntarily give up power, returning to Mt. Vernon and his own agricultural pursuits.

This is one history lesson that truly resonated with Washington. He had grown up reading the moral lessons of the Roman stoic philosopher Seneca, who inspired Washington to always exhibit an even temperament. Self-sacrifice and a willingness to act in the interest of the greater good were regarded as core Roman virtues; Washington intended that they become American virtues.

Brookhiser, who has also written acclaimed biographies of Alexander Hamilton and Gouverneur Morris, reminds that Washington and the other founders understood the Roman example to be a cautionary tale. Franklin is supposed to have told a citizen, who inquired as to the new country’s form of government, that it was to be “a republic, if you can keep it” (p. 122), an acknowledgment that a Republic can easily give way to empire and descend into tyranny. For Washington, an avid student of the Roman way, there were no better examples for Americans to emulate than the stoicism of Seneca and the example of Cincinnatus.

Applied learning

Washington impressed (and surprised) visitors with his knowledge of court etiquette and drawing room manners, knowledge that came from “The Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and in Conversation,” written by French Jesuits in 1595 (p. 127). Interestingly, several of the rules, which Washington is thought to have begun learning from an early age, dealt with the controlling of anger, also a major point of emphasis in Seneca’s writings. One of the more important underpinnings of the Jesuit handbook advisesthe reader to be modest in accepting honors. Another says, “Every action done in company ought to be done with some sign of respect to those that are present” (p. 128).

Well-read though he was, when it came to formal education Washington was something of an anomaly among the founding “generation.” Twenty-four of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention had been to college. By the time he was 15, Washington’s schooling was over and his training as a surveyor had begun. Yet his native intelligence, interest in philosophy and curiosity about history and the lessons it offers led him to what Brookhiser calls an appreciation of “the importance of right ideas” (p. 138).

Washington’s lifelong study of the classics convinced him that the virtues about which he read and in which he so firmly believed could be applied not just in everyday interaction with other people, but to the principles of Republican government. This belief doubtless contributed to the decision that led to the grand gesture of his career, his decision to surrender power and step down as president.

Brookhiser likens Washington’s fateful voluntary action to a father “who, when his children become adults, lets them go” (p. 185). Here is the culmination of a lifetime of learning and devotion to duty, a pointed example (not without an element of theater) that he set for his countrymen. Washington had learned well the virtues of self-sacrifice and he intended to pass them on to the nation and to succeeding generations.

A father’s admonition

In his first farewell address, Washington reminds Americans that they have been blessed with a bounteous land and that the great events of their nation’s creation had placed them in “the most enviable conditions” (p. 188). But Brookhiser notes that Washington does not end with a ringing, celebratory note but a stern admonition, as from a father who, having sacrificed to provide for his children, expects his work to be carried forward:

“At this auspicious period, the United States came into existence as a Nation, and if their Citizens should not be completely free and happy, the fault will be intirely their own” (p. 189).

Works cited

Brookhiser, Richard. Rediscovering George Washington: Founding Father. New York: Simon & Schuster (1996)

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Change and Culture, Essay Example

Statement of Intent, Admission Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

National Historical Publications & Records Commission

Papers of George Washington

University of Virginia

Additional information at http://gwpapers.virginia.edu/ and http://gwpapers.virginia.edu/editions/digital/ . The Washington Papers are also part of Founders Online .

A comprehensive edition of the papers of George Washington (1732 –1799), first President of the United States, the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He presided over the convention that drafted the Constitution. The edition is divided into the following series:

- Diaries of George Washington , Complete in 6 volumes

- Colonial Series, 1744-June 1775 , Complete in 10 volumes.

- Revolutionary War Series, June 1775-December 1783 , 26 vols. to date

- Confederation Series, January 1784-September 1788 , Complete in 6 volumes

- Presidential Series, September 1788-March 1797 , 19 vols. to date

- Retirement Series, March 1797-December 1799 Complete in 4 volumes

The George Washington Financial Papers project, also at the University of Virginia, makes Washington’s business and household records accessible.

George Washington (detail), 1797 by Gilbert Stuart

Previous Record | Next Record | Return to Index

Washington’s Farewell Speech Analysis

Introduction, avoiding foreign alliances, restraining political powers, strengthening religion.

On 19th September 1796, fatigued by attacks from political opponents and weights of the presidency, George Washington declared his intention not to run for the third term. He had served for two consecutive terms as the first president of the United States of America. With the help of James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, Washington composed a letter in Philadelphia in what later became described as the “Farewell Address.” Intended to guide and inspire future generations, the discourse described Washington’s protection of his government’s record and exemplified a typical statement of Federalist policy.

The address began as a draft anchored in Madison’s old notes then edited and revised by Hamilton. While Alexander Hamilton reviewed the address, he ensured to maintain the key points in the letter before passing it for finalization by Washington. The president warned the country of creating any alliance with oversea states and reiterated the significance of prioritizing America to facilitate prosperity rather than being dragged down by self-centered needs vouched by alliances. In his wisdom, Washington enumerated two biggest dangers to American success: foreign wars and political parties. He urged the Americans to avert entanglement with European conflicts and political partisanship. While Washington openly highlighted many things in his letter, the major items he felt were of utmost importance included avoiding forming foreign alliances, limiting political power, and strengthening religion.

The key concern Washington raised continually is preventing the creation of lasting foreign coalitions. He stated that “have as little political connection as possible” (National Archives, 1796, Para 36). George views forming foreign alliances as just drawing benefits from America for the supplies and strong coalitions but the receivers might never return the favor. Having many overseas unions also infer several affairs to handle. Any minor snag may result in bigger challenges between member states. If war ensues, then it will trigger forming alliances with other partners. The situation could make America engage in a conflict against an oversea country that one might not know just because they are biased towards a certain member state. Allegiance will rapidly foment unfair fighting since America could resort to bias, hence, no need of forming permanent coalitions. Lack of forming foreign unions also avert emotive linkage with other countries. Emotive linkage could make member states exploit America due to the generosity it has extended to them. Therefore, a foreign country would prosper due to the help received and America would gradually wear out from such alliances.

Washington downplays the idea of creating oversea alliances since the perceived dangers outweigh the benefits. Contemporary governments have not strictly followed Washington’s warnings as observed in various alliances embraced by America. For example, the U.S. joined North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance in 1949 to give security and freedom to its members through military and political means. Over the years, NATO has engaged in controversial missions and America’s name has been dragged in such undertakings. For instance, the 2011 NATO-led operations in Libya sparked debate worldwide. In another scenario, NATO has supported Ukraine with financial and military equipment since the illegitimate and illegal seizure of Crimea in 2014 (North Atlantic Treaty Organization, 2022). These show that present-day leadership has less regard for the ideas expressed by Washington in his farewell address.

As part of his farewell letter, Washington warned of restricting the political power by distributing controls to separate arms of government. He viewed this will avert one ruler to subdue other branches, resulting in the misuse of bestowed powers that could culminate in damaging the country. In the letter, it is detailed as “a customary weapon by which free governments are destroyed” (National Archives, 1796, Para 25). Washington meant that power should be practically divided equally and fairly among various branches of government.

Firming religion is significant since it is a vital aspect of the popular regime. Specifically, Washington states that religion is “a necessary spring of popular government” (National Archives, 1798, Para 27). He believed that religion should be integrated into a government since faith shapes the ethics and morals of an individual. Therefore, implementing any religion would result in a country with principles that can reduce any desire to engage in warfare. It is agreeable with Washington’s views of embracing religion in a country. It does not matter which religion but promoting all faith such as Islam, Christianity, Hinduism, Judaism all help in shaping morals as a people.

In conclusion, Washington’s farewell address offered insightful teachings that America should embrace to shape future generations. He knew that America would have a new administration after the end of his tenure and that the person taking over might not be knowledgeable and concerned with caring for the whole country. Therefore, the address warns of various issues that should be shunned to ensure a prosperous America. Items of utmost importance include avoiding forming foreign alliances, limiting pollical power, and strengthening religion. Washington desires a prosperous and peaceful America after exiting the realms of power.

National Archives. (1796). Farewell address, 19 September 1796 . Web.

North Atlantic Treaty Organization (2022). NATO steps up support for Ukraine, strengthens deterrence and defence . Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 28). Washington’s Farewell Speech Analysis. https://ivypanda.com/essays/george-washingtons-farewell-address-essay-examples/

"Washington’s Farewell Speech Analysis." IvyPanda , 28 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/george-washingtons-farewell-address-essay-examples/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Washington’s Farewell Speech Analysis'. 28 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Washington’s Farewell Speech Analysis." February 28, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/george-washingtons-farewell-address-essay-examples/.

1. IvyPanda . "Washington’s Farewell Speech Analysis." February 28, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/george-washingtons-farewell-address-essay-examples/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Washington’s Farewell Speech Analysis." February 28, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/george-washingtons-farewell-address-essay-examples/.

- George Washington's Farewell Address

- George Washington's Achievements and Farewell Address

- “Farewell Address” by George Washington

- Americans, Here Me Now: G. Washington’s Farewell

- Washington’s Farewell Address: The Importance of Unity to the American People

- US Government 1789-1821

- Teaching Emotive Language

- Themes in A Farewell to Arms

- George Washington and Neo-Classical Imagery

- Early Leaders of the New Republic and Their Impacts on the Government

- Nixon and His Presidency: Discussion

- How T. Jefferson Envisioned the American Republic

- Abraham Lincoln Leadership: American Ex-Presidents

- Barack Obama's Biography and Political Leadership

- President Hoover's Role During the Great Depression

Papers of George Washington

Description not yet available.

Books in this Series

The Papers of George Washington